Abstract

Vocal fatigue (VF) is a significant portion of occupational voice disorders. Researchers have proposed numerous therapeutic approaches to alleviate VF. However, the efficacy of vocal function exercises (VFEs) as a safe, effective, and simple method is unclear. The current study aims to investigate the effect of VFEs on occupational-related VF in Iranian bank workers. A single-blinded randomized controlled trial with four-level blocking After screening 444 workers, 43 persons with vocal fatigue (VF) were allocated between intervention and control groups. The gender of participants was considered a confounding parameter. Intervention group participants (IGP) (20 males and two females) practiced vocal function exercises (VFEs) (online training) for two weeks, while control group participants (CGP) (20 males and a female) continued their routine lifestyle. The Number of Vocal Fatigue Symptoms (NoVFS), Maximum Phonation Time (MPT), Voice Handicap Index (VHI), and Vocal Fatigue Index (VFI) at pre-intervention and post-intervention levels were gathered and compared. According to the intergroup, pre-/post-intervention differences, and intragroup analysis, the IGP experienced a significant reduction in the NoVFS (P = 0.006, P = 0.009), the mean score VHI (P:0.006, P: 0.001, P: 0.001), the total mean score of VFI (P < 0.001, P < 0.001, P < 0.001), and the first (P = 0.005, P = 0.002, P < 0.001) and second (P = 0.006, P < 0.001) factors’ mean score of VFI. Additionally, there was an improvement in the MPT (P < 0.001, P < 0.001, P < 0.001) and the third factor (P = 0.01, P = 0.004, P = 0.021) mean score of VFI. Vocal function exercises can alleviate symptoms, voice handicaps, tiredness, avoidance, and physical discomfort of vocal fatigue in bank workers. Additionally, it can improve glottal (pulmonary) sufficiency and rest recovery of vocal fatigue in this group of workers.

Keywords: Vocal function exercises, Voice disorders, Vocal fatigue, Occupational groups, Occupational diseases

Introduction

Professional voice users include numerous workers who depend on their vocal abilities to earn a living [1]. Researchers have reported that 25-30% of the American workforce depends on their voice [2]. The higher vocal load in professional voice users causes them to experience voice disorders more frequently than others. Polish researchers [3] reported that occupational voice disorders occupy 20% of all occupational diseases. Also, five million UK workforce suffer from voice disabilities [4]. Bank workers need continuous communication with customers in a stressful and noisy environment [5]. Researchers reported a high prevalence of musculoskeletal problems like head and neck pain [6] and chronic fatigue [7]. Noise pollution, stress, and permanent high vocal load can lead to voice disorders [3, 8, 9]. Voice disorders stem from occupational duties known as occupational (professional) voice disorders [10]. A significant portion of occupational voice disorders is vocal fatigue, a risk factor for serious voice problems like vocal nodules [11].

Fatigue is an ongoing dynamic process during high-intensity activities and includes central and peripheral mechanisms. It temporarily reduces the power-producing capability of muscles [12]. A few studies have been conducted regarding the pathophysiology of vocal fatigue. Vocal fatigue (VF) is considered a multifactorial clinical condition, but there is little consensus regarding its definition. Solomon et al. [13] defined VF as a condition in which a person experiences vocal discomfort and degradation of vocal parameters. In addition, this condition worsens with continuous vocal use and alleviates after voice rest. In 2003, McCabe and Titz [14] proposed a conceptual model for vocal fatigue. The theoretical basis of this model was the immobility of the muscle group, which means that the agonist/antagonist muscle pairs are activated simultaneously during vocalization and produce isometric contraction in the speech subsystems. For example, if there is an excessive contraction in the lateral cricoarytenoid (LCA) muscle, it causes the gradual bowing of the vocal folds. To solve this problem, they suggested stretching and reducing the compactness of the vocal folds. Exercises based on pitch can create this situation. Researchers attributed various symptoms to vocal fatigue. Laukkanen and Rantala [15] related nine symptoms to VF that consisted of vocal tiredness, hoarseness without flu, throat globus, discomfort in the throat, tiredness or pain in the throat and neck after speaking/singing, pitch break, voice loss, and unfavorable effects of VF on communication. To investigate VF, researchers prominently used a checklist of vocal fatigue symptoms and the Voice Handicap Index (VHI). In 2015, Nanjundeswaran and colleagues [16] published a Vocal Fatigue Index (VFI), a valid and reliable instrument to probe VF in patients.

According to the etiology approach regarding VF, researchers have proposed various therapy methods such as adjustments of occupational environment [17], use of amplifiers [18], voice rests [17, 19], and vocal hygiene [20]. However, studies have preferred direct therapy approaches and melodic (musical) voice therapy methods like chant therapy [14, 21, 22]. Vocal function exercises are a direct voice therapy method structured in the musical foundation.

Vocal Function Exercises (VFEs) are a physiological voice therapy approach developed by Joseph Stemple and colleagues [23] at the University of Kentucky. Later research has broadly supported the benefits of this method in various groups of people with normal and pathological voices. A review article by Angadi et al. [24] revealed the moderate-to-strong effectiveness of VFEs without any reports of harmfulness or side effects. Researchers have reported improved respiratory and glottal efficacy [25], acoustic parameters [26], perceptual scales [27], and self-perception indices [28].

The vocal function exercises are one of the most accepted voice therapy protocols. However, there is a rare report about their effectiveness on vocal fatigue [29], which is a prevalent voice complaint among users of various voice-needed occupations [30]. The present study investigated the effect of vocal function exercises on vocal fatigue in bank employees. This study divided vocal fatigue symptoms between two groups of General Symptoms of Voice Disorders (GSFD) and Specific Symptoms of Vocal Fatigue (SSFV) [8, 11, 13, 16, 31–34]. The GSVD included 12 voice complaints that generally related to voice disorders and reported in various voice pathologies (vocal effort, laryngeal discomfort, neck or shoulder tension, throat or neck pain, reduced pitch range, glottal dryness, loss of vocal flexibility, reduced vocal power, reduced vocal control, voice loss, non-infection roughness, and reduced loudness range) [35]. Also, two complaints of worsening reported general symptoms of VF during the day and complete or partial improvement after rest were considered SSVF [16, 33, 36, 37]. Employees who had one of the following two conditions were considered as persons with VF: (1) Reported at least two GSVD and one SSVF in the last month. (2) Had at least one GSVD and one SSVF in the past month, and the Voice Handicap Index score above 14.5, as a cut-off point of VHI. The study utilized the Voice Handicap Index (VHI) [38, 39], the Checklist of Vocal Fatigue Symptoms, and Maximum Phonation Time (MPT) as the initial components of the vocal function exercises (VFEs) protocol. Additionally, we incorporated the Vocal Fatigue Index (VFI) as a valid and reliable tool for evaluating voice fatigue [16, 40]. Bank employees were considered as the target group because: (1) Studies have suggested the need to investigate voice problems in different groups of voice users. (2) Previous studies reported the risk factors of voice problems such as environmental noise and job stress in bank employees [41]. Also, researchers reported that they consist of 1% of voice therapy clinic patients [42]. So, we predicted the possibility of voice fatigue in bank workers. (3) The data collection of this study coincided with the global pandemic of COVID-19, which made access to other groups of voice users, including teachers and kindergarten teachers, almost impossible. The current study attempts to answer this question: Do VFEs affect the VF in bank workers or not? So, a number of symptoms of vocal fatigue, tiredness, avoidance of voice, physical discomfort with voice use, improvement of symptoms or lack thereof with rest, voice handicap, and glottal efficiency of intervention group workers were compared before and after two weeks of VFEs and compared with their parallel and homogeneous coworkers in a control group. Participants received exercises through teletherapy, which is another innovation of the study.

Materials and methods

Ethics

This study followed the CONSORT guidelines. The ethics committee of the Iran University of Medical Sciences (IR.IUMS.RES.1400.225) and the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials (IRCT20220116053728N1) approved the study.

Study Design

The study was conducted in two stages. In the first stage, employees were screened using a questionnaire battery to identify participants with vocal fatigue. Eligible employees participated in the second stage, which was a single-blinded randomized controlled trial. The trial consisted of an intervention group and a control group. Participants in the intervention group received two weeks of vocal function exercises, while participants in the control group continued their routine life. Pre-intervention and post-intervention data were collected and analyzed by a blinded statistician. The data included a demographic questionnaire, a checklist of vocal fatigue symptoms, the voice handicap index, and the vocal fatigue index.

Participants

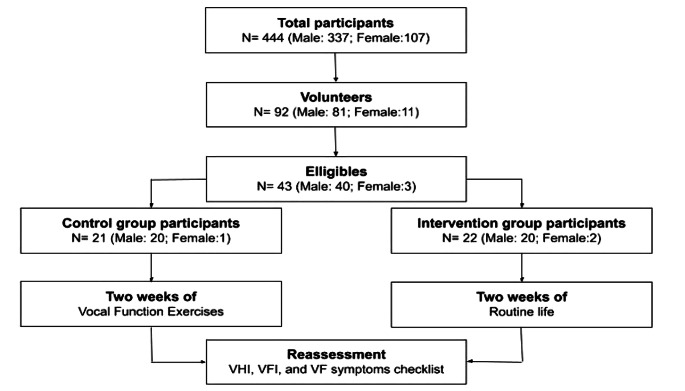

In the first stage, 444 bank workers participated in the study. They consisted of 337 men (75.9%) and 107 women (24.1%), with an average age of 42.5 +/-6.87. The marital status of participants included 42 bachelors (9.5%), 382 married persons (86%), 18 divorced persons (4.1%), and 2 widowers (0.5%). A specific question existed at the end of 374 (78.2%) of the gathered questionnaires that questioned readiness to participate in the second phase. 92 (26.5%) of the participants were willing to participate in the intervention phase. Based on the eligibility criteria, 43 (46.73%) of them [men: 40 (93%) and female: 3 (7%)] including 5 (11.6%) single, 37 (86%) married, and 1 (2.3%) divorced employee were eligible to participate in the second phase. The entrance (eligibility) criteria included: Age between 18 and 50, expert language user (Persian or Kurdish), three working days at the position need direct connection with bank customers, not having experienced recent speech-language system diseases. In addition, they must have reported at least one general vocal fatigue symptom, at least one of the specific vocal fatigue symptoms, and voice handicap index mean score higher than the Persian-version cutoff point (14.5) OR at least two general vocal fatigue symptoms and one specific vocal fatigue symptom (a vocal fatigue definition at current study). The participants were divided into two groups: the Intervention Group Participants (IGP) (22 participants, 20 males and 2 females) and the Control Group Participants (CGP) (21 participants, 20 males and 1 female). Both groups reported pre-intervention data levels using paper and online questionnaires, and post-intervention data levels using only online questionnaires. All of the intervention-stage participants remained in the study, and no one dropped out due to the excursion criteria, which included unwillingness to continue cooperation, two consecutive days without practicing, executing less than 50% of total exercise sessions, and unavailability to gather reassessment data (death, transfer, inaccessibility, and so on). In addition, the study considered gender as a confounding condition [8, 43–46] and controlled between two groups of the study Fig 1.

Fig. 1.

Study flowchart

Intervention

The employee who participated in the intervention phase of the study signed a consent form that provided enough information about the intervention protocol and was sent to them via email or messenger. After accepting the terms, they were enrolled in the study.

Vocal Function Exercises Protocol

The IGP received an online format of original vocal function exercises (VFEs) published by Stemple and colleagues at Kentucky University [23]. The VFEs consist of four exercises, which are to be completed consecutively, two times, twice per day, and recorded in a VFE practice record sheet. The exercises are as follows:

Warm-Up

Maximum phonation time (MPT) of vowel /i/ at the “F” musical note of the middle octave for females and an octave lower for males.

Stretching

Gliding from the lowest vocal pitch to the highest vocal pitch. The gliding occurs on the vowel /L/ at the English word /knoll/. The purpose is a minimum pitch break.

Contraction

Gliding from the highest to the lowest vocal pitch. The gliding occurs on the vowel /L/ of the English word /knoll/, and the purpose is a minimum pitch break.

Low-Impact Adductory Power

Maximal sustaining (like MPT) at the musical notes (C-D-E-F-G) of the middle octave for females and an octave lower for males. Sustaining the vocalizations occurs in the context of the English word “old” without the final /L/ pronunciation.

The maximum phonation time of practices one and four is recorded in seconds, while the execution of practices two and three is enough.

Execution

In the present study, some alterations were made to the original protocol of vocal function exercises. Specifically, the participants practiced the proposed English words articulated with an accent in the vowel space of their native languages, Persian or Kurdish. The exercises were taught and practiced through online therapeutic video calls, often via WhatsApp by the study’s first author. The participants recorded their daily therapies in an online version of the VFE practice record designed on the Google platform.

After gathering the first level of data, the researchers called the IGP via WhatsApp video call. At first, they received an overall discussion about practices, then learned the execution of the VFEs. The participants checked vocal adjustment with the free application called Tuner T1, which the research team justified its appropriateness. Then, they received an educational pack (summary of exercises, recorded vocal notes) and the online VFE practice record link. A week later, the IGP received an extra therapeutic session while they received daily messages to remind them of their daily practices.

Outcomes

The study used a questionnaire battery composed of six sections.

Section One

Was a demographic questionnaire containing personal and professional characteristics such as age, gender, marital status, education, working experiences, weekly working days, position, and so on.

Section Two

Surveyed the employees’ lifestyles by five-level answering questions. This section contained questions about their habits and life routines such as smoking cigarettes, daily water drinking, alcohol drinking, and fruit and vegetable consumption.

Section Three

Was the medical history checklist, which asked about previous and current diseases such as neurological diseases, head and neck diseases, reflux, allergies, etc.

Sections Four and Five

Were Persian versions of VHI and VFI, respectively.

Finally, Section Six

Contains 12 General Symptoms of Voice Disorders (GSVD) and two Specific Symptoms of Vocal Fatigue (SSVF) [8, 11, 13, 16, 31–34]. The GSVD included 12 voice complaints that generally related to voice disorders and reported various voice pathologies (vocal effort, laryngeal discomfort, neck or shoulder tension, throat or neck pain, reduced pitch range, glottal dryness, loss of vocal flexibility, reduced vocal power, reduced vocal control, voice loss, non-infection roughness, and reduced loudness range) [35]. Also, two complaints of worsening reported general symptoms of VF during the day and complete or partial improvement after rest were considered SSVF [16, 33, 36, 37]. Employees who had one of the following two conditions were considered as persons with VF: (1) Reported at least two GSVD and one SSVF in the last month. (2) Had at least one GSVD and one SSVF in the past month, and the Voice Handicap Index score above 14.5, as a cut-off point of VHI.

Sample Size Calculation

According to previous studies [47, 48], at least 42 persons should have participated in the intervention phase of the study. A pilot study showed that this sample size was obtained by screening about 450–500 workers at the first stage of the study.

Randomization Process

The study used a four-level blocking method to randomly assign participants to either the control or intervention group. The method used two sets of six possible chains of control/intervention states that equally divided four persons between control and intervention groups. The order was packed in a cover so that the allocated choice of order (intervention or control) appeared independently. Each gender group attained a set of six available orders. By considering the gender of each worker, a blinded person selected a four-level blocked order by the simple draw selection strategy that distributed the following four participants between control or intervention groups (two participants per group). This strategy guaranteed a similar proportion of males/females in the control and intervention groups. The four-level blocked strategy design allows independent observation of each chance. So, the subsequent allocation of a four-level block remained unclear. Also, this allocation pattern maintained a parallel and simultaneous distribution of participants between IGP and CGP while data gathering was in progress.

Blinding

The study is a single-blinded randomized controlled trial (blinded-statistician methodologist).

Data Analysis

The study used descriptive statistics to summarize the demographic and professional features. The skewness and kurtosis of quantitative data declared normal distribution. So, the independent sample T-test and dependent simple T-test were selected to analyze pre-intervention and post-intervention data. The effect size was calculated based on Cohen’s effect size classification. Data analysis was executed using SPSS 27.

Results

In the second stage of the study, 43 participants were divided between the intervention group (22 persons with an average age of 42.95 +/- 5.02 years and 20.54 +/- 6.23 years of work experience) and the control group (21 persons with an average age of 43.57 +/- 5.73 years and 18.28 +/- 8.28 years of work experience). All of the participants remained in the study, and the two groups were similar in demographic and lifestyle characteristics.

Table 1 presents a descriptive analysis and comparison of two groups at pre- and post-intervention levels. The table also reports the case-by-case differences between pre- and post-intervention data, calculated as (post-intervention) - (pre-intervention). The last column of the table shows the effect size of significant pairs. The study results indicate that the intervention and control groups were similar at the pre-intervention stage (at P < 0.05). After the intervention, the two groups differed significantly in all variables except the number of vocal fatigue symptoms (NoVFS) and the second factor of VFI (VFI-F2). By considering effect size, the difference between the two groups was small at the first factor of VFI (VFI-F1) (P: 0.012), very large at the total score of VHI (VHI-T) (P: 0.006), third factor of VFI (VFI-F3) (P: 0.010), and total score of VFI (VFI-T) (P: 0.001), and huge at MPT scores (P: <0.001). The comparison of the case-by-case difference of post-intervention from pre-intervention data between the IGP and CGP revealed a significant relationship in all gathered sections. This relationship was (very) large in NoVFS (P: 0.006), VHI-T (P: 0.001), VFI-F1 (P: 0.002), VFI-F2 (P: 0.006), and VFI-F3 (P: 0.004), and huge at MPT (P: <0.001), VFI-T (P: <0.001).

Table 1.

Intergroup analysis of variables before and after intervention between intervention and control groups

| Variables | IG | CG | P-Value | Effect size | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Range | Mean (SD) | Range | Mean (SD) | ||||

| NoVFS | Pre-intervention | 1–8 | 2.42 (2.303) | 1–4 | 1.57 (1.075) | 0.115 | |

| Post-intervention | 0–4 | 1.31 (1.249) | 0–4 | 1.80 (1.167) | 0.190 | ||

| Pre/post differences | (-4)-2 | -1.13 (1.859) | (-2)-2 | 0.23 (1.135) | 0.006** | 0.887 | |

| MPT | Pre-intervention | 12–27 | 18.95 (3.722) | 11–30 | 18.66 (4.809) | 0.827 | |

| Post-intervention | 18–31 | 24.13 (4.245) | 10–33 | 18.14 (4.992) | < 0.001** | -1.296 | |

| Pre/post differences | 1–12 | 5.18 (2.422) | (-5)-3 | − 0.52 (2.502) | < 0.001** | -2.318 | |

| VHI-T | Pre-intervention | 0–79 | 24.63 (18.375) | 3–60 | 24.71 (15.182) | 0.988 | |

| Post-intervention | 0–44 | 13.77 (9.645) | 0–73 | 25.66 (16.417) | 0.006** | 0.889 | |

| Pre/post differences | (-53)-6 | -10.86 (13.541) | (-14)-14 | 0.95 (7.172) | 0.001** | 1.083 | |

| VFI-F1 | Pre-intervention | 1–28 | 13.31 (6.454) | 0–26 | 13.23 (6.564) | 0.968 | |

| Post-intervention | 0–16 | 7.31 (5.149) | 0–27 | 12.80 (6.852) | 0.005** | -0.012 | |

| Pre/post differences | (-16)-4 | -6.00 (4.353) | (-19)-7 | -0.42 (6.719) | 0.002** | 0.989 | |

| VFI-F2 | Pre-intervention | 0–16 | 5.81 (4.371) | 0–13 | 4.52 (4.069) | 0.321 | |

| Post-intervention | 0–13 | 2.77 (3.598) | 0–13 | 4.76 (3.505) | 0.074 | ||

| Pre/post differences | (-10)-2 | -3.04 (2.836) | (-12)-4 | 0.23 (4.459) | 0.006** | 0.883 | |

| VFI-F3 | Pre-intervention | 0–12 | 6.36 (3.170) | 0–11 | 6.14 (2.613) | 0.805 | |

| Post-intervention | 0–12 | 7.86 (3.719) | 0–10 | 5.19 (2.676) | 0.010* | -0.822 | |

| Pre/post differences | (-7)-5 | 1.50 (2.824) | (-8)-2 | -0.95 (2.438) | 0.004** | -0.928 | |

| VFI-T | Pre-intervention | 13–45 | 24.86 (9.929) | 7–42 | 23.61 (8.714) | 0.664 | |

| Post-intervention | 1–27 | 14.04 (8.386) | 5–45 | 24.28 (9.187) | < 0.001** | 1.156 | |

| Pre/post differences | (-20)-4 | -10.81 (5.695) | (-27)-13 | 0.66 (10.046) | < 0.001** | 1.415 | |

IG: intervention group; CG: control group; NoVFS: number of vocal fatigue symptoms; MPT: maximum phonation time; VHI-T: voice handicap index-total score; VFI-F1: vocal fatigue index-factor 1; VFI-F2: vocal fatigue index-factor 2; VFI-F3: vocal fatigue index-factor 3; VFI-T: vocal fatigue index-total score; *: P < 0.05; **: P < 0.01

Table 2 presents the intragroup outcome of seven analyzed variables. The data indicates that the IGP experienced a significant divergence between the pre-intervention and post-intervention levels. The analysis revealed that VFEs significantly affect all variables. The effect size of the NoVFS (P: 0.009) and VFI-F3 (P: 0.021) was large, and the VHI-T (P: 0.001) and the VFI-F2 (P: <0.001) was very large, and the MPT (P: <0.001), the VFI-F1 (P: <0.001), and VFI-T were huge. However, the pre-intervention and post-intervention comparisons in the CGP were not statistically significant.

Table 2.

Intragroup analysis of variables from intervention and control groups before and after intervention

| Variables | Pre-intervention | Post-intervention | P-Value | Effect size | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Range | Mean (SD) | Range | Mean (SD) | ||||

| NoVFS | Intervention group | 1–8 | 2.42 (2.303) | 0–4 | 1.31 (1.249) | 0.009** | 0.611 |

| Control group | 1–4 | 1.57 (1.075) | 0–4 | 1.80 (1.167) | 0.348 | ||

| MPT | Intervention group | 12–27 | 18.95 (3.722) | 18–31 | 24.13 (4.245) | < 0.001** | -2.139 |

| Control group | 11–30 | 18.66 (4.809) | 10–33 | 18.14 (4.992) | 0.349 | ||

| VHI-T | Intervention group | 0–79 | 24.63 (18.375) | 0–44 | 13.77 (9.645) | 0.001** | 0.802 |

| Control group | 3–60 | 24.71 (15.182) | 0–73 | 25.66 (16.417) | 0.550 | ||

| VFI-F1 | Intervention group | 1–28 | 13.31 (6.454) | 0–16 | 7.31 (5.149) | < 0.001** | 1.378 |

| Control group | 0–26 | 13.23 (6.564) | 0–27 | 12.80 (6.852) | 0.773 | ||

| VFI-F2 | Intervention group | 0–16 | 5.81 (4.371) | 0–13 | 2.77 (3.598) | < 0.001** | 1.074 |

| Control group | 0–13 | 4.52 (4.069) | 0–13 | 4.76 (3.505) | 0.809 | ||

| VFI-F3 | Intervention group | 0–12 | 6.36 (3.170) | 0–12 | 7.86 (3.719) | 0.021* | -0.522 |

| Control group | 0–11 | 6.14 (2.613) | 0–10 | 5.19 (2.676) | 0.089 | ||

| VFI-T | Intervention group | 13–45 | 24.86 (9.929) | 1–27 | 14.04 (8.386) | < 0.001** | 1.865 |

| Control group | 7–42 | 23.61 (8.714) | 5–45 | 24.28 (9.187) | 0.764 | ||

IG: intervention group; CG: control group; NoVFS: number of vocal fatigue symptoms; MPT: maximum phonation time; VHI-T: voice handicap index-total score; VFI-F1: vocal fatigue index-factor 1; VFI-F2: vocal fatigue index-factor 2; VFI-F3: vocal fatigue index-factor 3; VFI-T: vocal fatigue index-total score; *: P < 0.05; **: P < 0.01

Discussions

This clinical trial study, conducted under single-blind conditions, aimed to investigate the effect of vocal function exercises on vocal fatigue in bank workers. The study’s outcome measures included the mean scores of VHI and VFI, the MPT measure, and the NoVFS. The interval between the two levels of data gathering, i.e., the first (pre-intervention) level and the second (post-intervention) level, for both intervention and control group participants was two weeks. Gender was considered a confounding variable.

The data analysis indicated that the two groups were similar in terms of demographic, lifestyle, and medical history aspects. Furthermore, an inter-group comparison of the NoVFS, MPT, and indices confirmed that the two groups were similar at the pre-intervention level of the study. Therefore, the allocation strategy effectively divided the participants between the two groups, and the background influencers on the intervention were under control.

The intergroup analysis of the NoVFS after two weeks of VFEs in the intervention group did not reveal any statistically significant differences between the two groups. However, the case-by-case difference between pre-intervention and post-intervention data on NoVFS revealed meaningful and strong relationships between the two groups. Additionally, the intragroup comparison showed significant and large differences between pre-intervention and post-intervention NoVFS in the IGP but not in the CGP. Therefore, it is logical to interpret that the higher (but not significant) mean number of VF symptoms in the IGP than in the CGP at the pre-intervention stage was the main reason for the statistically insignificant relationship in the post-intervention intergroup comparison.

Pasa et al. [20] investigated the effect of vocal function exercises (VFEs) on perceived vocal symptoms. Researchers used a modified version of VFEs in which the fourth exercise was replaced with three subjective practices. Three levels of pre-intervention, post-intervention, and follow-up comparison on a 100 mm visual analog scale (VAS) revealed no significant influence of VFEs. In addition, Gillivan-Morphy and his colleagues [49] studied the effect of VFEs on the self-perception of voice in teachers with voice problems. They reported alleviation of voice complaints at teachers after VFEs executions. In elderly individuals, researchers confirmed that VFEs reduced the perceived phonatory effort (PPE) and experienced a positive self-perceived effect after therapy sessions [24, 26, 50]. Teixeira and Behlau [51] compared VFEs with the use of amplifiers in patients who have behavioral voice disorders. Participants reported self-rating of dysphonia before and after the execution of 6 weeks of VFEs. Data revealed a significant reduction in the self-perceived level of dysphonia after VFEs. Myers and colleagues [52] reported that VFEs decreased perceived vocal effort in female smokers.

The initial component of daily vocal function exercises (VFEs) is the maximum phonation time (MPT), which has been reported in numerous VFE studies. The present study demonstrated a notable improvement in the MPT of the intervention group following two weeks of VFEs. A prior meta-analysis by Barsties and his colleagues [53] verified that VFEs are the sole voice therapy regimen that enhances the aerodynamics of voice production, particularly MPT. Sabol et al. [25] found that VFEs boosted the MPT of graduate students majoring in voice. Pasa and his colleagues [20] suggested that a modified version of VFEs doesn’t significantly impact teachers’ MPT. Subsequent research consistently reported that VFEs considerably enhance MPT in elderly patients with vocal issues [50, 54], individuals with normal voices [29], and patients with unilateral vocal fold paralysis [55]. Bane and his colleagues [56] examined the precise correlation between VFEs and MPT enhancement, revealing that the MPT improvement directly results from the maximum sustained phonation during VFEs.

The Voice Handicap Index (VHI) has been widely used in the study of vocal function exercises (VFEs). Roy et al. [28] reported a significant decrease in VHI means scores among teachers after six weeks of VFEs. Similarly, the present study reported a significant decrease in the mean score of VHI in persons with VF after two weeks of VFEs. Sauder et al. [54] surveyed the effect of 6 weeks of VFEs on the VHI mean score of patients with Presbyphonia and reported a reduction in VHI mean scores. Later studies by Kaneko et al. [57] and Motohashi et al. [58] confirmed this finding. Kapsner-Smith et al. [59] compared VHI score outcomes between the VFEs, flow-resistance tube, and control groups. Data revealed significant and homological improvement for both treatment groups relative to the control group. In two similar studies, Pedrosa et al. [60] and Antonetti et al. [61] reported a significant effect of VFEs on the voice handicap index scores. They announced similar proficiency of VFEs with a comprehensive voice rehabilitation program and a Semi-occluded vocal tract exercise -Therapeutic Program (SOVTE-TP), respectively. Additionally, studies reported the effectiveness of VFEs on the mean score of VHI in patients with muscle tension dysphonia (MTD) [27], unilateral vocal fold paralysis (UVFP) [55], and adults irradiated for laryngeal cancer [62].

After two weeks of vocal function exercises, this study reported a significant improvement in the mean scores of the vocal fatigue index. The total score of VFI, differences between pre-intervention and post-intervention scores, and all three factors of VFI, except the second factor in intergroup analysis, showed (very) large significant effects from the VFEs. The first two factors of VFI (VFI-F1 and VFI-F2) reported decreased mean scores, interpreted as lower levels of vocal fatigue. However, the VFI-F3 revealed increased mean scores related to better alleviation from experienced VF. In a similar study, Antonetti et al. [61] compared the VFI scores in two groups of behavioral dysphonia participants who received four weeks of the Semi-Occluded Vocal Exercises-Therapeutic Program (SOVTE-TP) and the VFEs. Data analysis demonstrated a similar reduction in the two groups.

Limitations and Future Directions

The study has some limitations. The number of female participants was limited, despite the higher prevalence of voice problems among females than males. Additionally, the total number of participants was low. Future researchers are suggested to use acoustic tools as well.

Conclusion

In the study of bank workers with vocal fatigue, vocal function exercises (VFEs) improved respiratory system sufficiency by increasing maximum phonation time and alleviated experienced vocal fatigue symptoms. The data from indices showed that VFEs reduced tiredness of voice and physical discomfort mean scores (VFI-F1 and VFI-F2), indicating a lower level of vocal fatigue. Additionally, VFEs increased the improvement of symptoms mean score (VFI-F3), suggesting better recovery from vocal fatigue. Furthermore, VFEs reduced the total mean score of the voice handicap index, revealing a lower effect of vocal fatigue on daily/occupational routines.

Acknowledgements

The researchers express their gratitude to the bank employees of Melli Bank in Tehran and Kurdistan provinces who participated in this study.

Funding

This article is extracted from the master’s thesis of the first author.

Declarations

Competing Interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Sataloff RT (2001) Professional voice users: the evaluation of voice disorders Occupational Medicine (Philadelphia, Pa), 16(4): p. 633 – 47, v. [PubMed]

- 2.Titze IR, Lemke J, Montequin D (1997) Populations in the US workforce who rely on voice as a primary tool of trade: a preliminary report. J Voice 11(3):254–259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Niebudek-Bogusz E, Śliwińska-Kowalska M (2013) An overview of occupational voice disorders in Poland. Int J Occup Med Environ Health 26:659–669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carding P (2007) Occupational voice disorders: is there a firm case for industrial injuries disablement benefit? Logopedics Phoniatrics Vocology 32(1):47–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Müderrisoglu Ö (2014) Occupational stress factors in Small Island economies: evidence from Public and private banks in Northern Cyprus. Int J Economic Perspect, 8(3)

- 6.Yu I, Wong T (1996) Musculoskeletal problems among VDU workers in a Hong Kong bank. Occup Med 46(4):275–280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Fatima Marinho de Souza M et al (2002) Chronic fatigue among bank workers in Brazil. Occup Med (Lond) 52(4):187–194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gotaas C, Starr CD (1993) Vocal fatigue among teachers. Folia Phoniatr (Basel) 45(3):120–129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kankare E et al (2012) Subjective evaluation of voice and working conditions and phoniatric examination in kindergarten teachers. Folia Phoniatr Logop 64(1):12–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Williams NR (2003) Occupational groups at risk of voice disorders: a review of the literature. Occup Med (Lond) 53(7):456–460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Casper JK, Leonard R (2006) Understanding voice problems: a physiological perspective for diagnosis and treatment. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins

- 12.Poole DC et al (2016) Critical power: an important fatigue threshold in Exercise Physiology. Med Sci Sports Exerc 48(11):2320–2334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Solomon NP (2008) Vocal fatigue and its relation to vocal hyperfunction †. Int J Speech Lang Pathol 10(4):254–266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McCabe DJ, Titze IR (2002) Chant therapy for treating vocal fatigue among public school teachers

- 15.Laukkanen A-M, Rantala L (2021) Relations between creaky voice and vocal symptoms of fatigue. Folia Phoniatr et Logopaedica 73(2):146–154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nanjundeswaran C et al (2015) Vocal fatigue index (VFI): development and validation. J Voice 29(4):433–440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Södersten M et al (2002) Vocal behavior and vocal loading factors for preschool teachers at work studied with Binaural DAT recordings. J Voice 16(3):356–371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Banks RE, Bottalico P, Hunter EJ (2017) The Effect of Classroom Capacity on vocal fatigue as quantified by the vocal fatigue index. Folia Phoniatr Logop 69(3):85–93 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yiu EM, Chan RM (2003) Effect of hydration and vocal rest on the vocal fatigue in amateur karaoke singers. J Voice 17(2):216–227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pasa G, Oates J, Dacakis G (2007) The relative effectiveness of vocal hygiene training and vocal function exercises in preventing voice disorders in primary school teachers. Logoped Phoniatr Vocol 32(3):128–140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Imaezue G, Oyebola M (2017) Treatment of vocal fatigue in teachers. J Otolaryngol ENT Res 7(1):00189 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Milbrath RL, Solomon NP (2003) Do vocal warm-up exercises alleviate vocal fatigue? [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Stemple JC et al (1994) Efficacy of vocal function exercises as a method of improving voice production. J Voice 8(3):271–278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Angadi V, Croake D, Stemple J (2019) Effects of vocal function exercises: a systematic review. J Voice, 33(1): p. 124.e13-124.e34. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Sabol JW, Lee L, Stemple JC (1995) The value of vocal function exercises in the practice regimen of singers. J Voice 9(1):27–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tay EY, Phyland, Oates J (2012) The effect of vocal function exercises on the voices of aging community choral singers. J Voice, 26(5): p. 672. e19-672. e27. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Jafari N et al (2017) Vocal function exercises for muscle tension dysphonia: auditory-perceptual evaluation and Self-Assessment Rating. J Voice 31(4):506 .e25-506.e31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roy N et al (2001) An evaluation of the effects of two treatment approaches for teachers with voice disorders: a prospective randomized clinical trial. J Speech Lang Hear Res 44(2):286–296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bane M et al (2019) Vocal function exercises for normal voice: the effects of varying dosage. Int J Speech Lang Pathol 21(1):37–45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Abou-Rafée M et al (2019) Vocal fatigue in dysphonic teachers who seek treatment. Codas 31(3):e20180120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kitch JA, Oates J (1994) The perceptual features of vocal fatigue as self-reported by a group of actors and singers. J Voice 8(3):207–214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kostyk BE, Rochet AP (1998) Laryngeal airway resistance in teacherswith vocal fatigue: a preliminary study. J Voice 12(3):287–299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Koufman JA, Blalock PD (1988) Vocal fatigue and dysphonia in the professional voice user: Bogart-Bacall syndrome. Laryngoscope 98(5):493–498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stemple JC, Roy N, Klaben BK (2018) Clinical voice pathology: theory and management. Plural Publishing

- 35.Moradi N et al (2013) Cutoff point at voice handicap index used to screen voice disorders among persian speakers. J Voice 27(1):130 .e1-130.e5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hunter EJ et al (2020) Toward a consensus description of vocal effort, vocal load, vocal loading, and vocal fatigue. J Speech Lang Hear Res 63(2):509–532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Welham NV, Maclagan MA (2003) Vocal fatigue: current knowledge and future directions. J Voice 17(1):21–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jacobson BH et al (1997) The voice handicap index (VHI) development and validation. Am J Speech-Language Pathol 6(3):66–70 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Moradi N et al (2013) Cross-cultural equivalence and evaluation of psychometric properties of voice handicap index into Persian. J Voice 27(2):258 .e15-258.e22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Naderifar E et al (2019) Cross-cultural adaptation and validation of the vocal fatigue index into Persian. J Voice 33(6):947e35–947e41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mahmoud Zadeh MS et al (2022) Investigating the Relationship between Medical History and General Health Status of Bank Workers with Voice Handicap Index and vocal fatigue index. Function Disabil J 5(1):69–69 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Martins RH et al (2016) Voice disorders: etiology and diagnosis. J Voice 30(6):761 .e1-761.e9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.de Jong FI et al (2006) Epidemiology of voice problems in Dutch teachers. Folia Phoniatr Logop 58(3):186–198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Helidoni M et al (2012) Voice risk factors in kindergarten teachers in Greece. Folia Phoniatr Logop 64(5):211–216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hunter EJ, Banks RE (2017) Gender differences in the Reporting of Vocal Fatigue in teachers as quantified by the vocal fatigue index. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 126(12):813–818 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Smith E et al (1998) Voice problems among teachers: differences by gender and teaching characteristics. J Voice 12(3):328–334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Afkhami M et al (2019) Correlation between vocal fatigue index and voice handicap index scores in persons with laryngeal pathologies. Function Disabil J 2(1):119–124 [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ohlsson A-C et al (2020) Voice therapy outcome—A randomized clinical trial comparing individual voice therapy, therapy in group, and controls without therapy. J Voice, 34(2): p. 303. e17-303. e26. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 49.Gillivan-Murphy P et al (2006) The effectiveness of a voice treatment approach for teachers with self-reported voice problems. J Voice 20(3):423–431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gorman S et al (2008) Aerodynamic changes as a result of vocal function exercises in elderly men. Laryngoscope 118(10):1900–1903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Teixeira LC, Behlau M (2015) Comparison between vocal function exercises and Voice amplification. J Voice 29(6):718–726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Myers BR, Mathy P, Roy N (2022) Behavioral treatment approaches to lowering Pitch in the female Voice. Journal of Voice [DOI] [PubMed]

- 53.Latoszek Bv (2023) The maximum phonation time as marker for voice treatment efficacy: a network meta-analysis. Clin Otolaryngol 48(2):130–138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sauder C et al (2010) Vocal function exercises for presbylaryngis: a multidimensional assessment of treatment outcomes. Annals Otology Rhinology Laryngology 119(7):460–467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kodama N, Yumoto E, Sanuki T (2022) Effect of Voice Therapy as a supplement after reinnervation surgery for breathy Dysphonia due to Unilateral Vocal fold paralysis. Journal of Voice [DOI] [PubMed]

- 56.Bane M et al (2022) Vocal function exercises with and without maximally sustained phonation: a randomized controlled trial of individuals with normal voice. J Voice [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 57.Kaneko M et al (2015) Multidimensional analysis on the effect of vocal function exercises on aged vocal Fold atrophy. J Voice 29(5):638–644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Motohashi R et al (2022) Effectiveness of Breath-holding pulling Exercise in patients with vocal fold atrophy. Journal of Voice [DOI] [PubMed]

- 59.Kapsner-Smith MR et al (2015) A randomized controlled trial of two semi-occluded vocal tract voice therapy protocols. J Speech Lang Hear Res 58(3):535–549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pedrosa V et al (2016) The effectiveness of the comprehensive voice rehabilitation program compared with the vocal function exercises method in behavioral dysphonia: a randomized clinical trial. J Voice, 30(3): p. 377. e11-377. e19. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 61.da Silva Antonetti AE et al (2023) Efficacy of a semi-occluded vocal tract exercises-therapeutic program in behavioral dysphonia: a randomized and blinded clinical trial. J Voice 37(2):215–225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Angadi V et al (2020) Efficacy of voice therapy in improving vocal function in adults irradiated for laryngeal cancers: a pilot study. J Voice, 34(6): p. 962. e9-962. e18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]