Abstract

Turbinaria ornata, Polycladia myrica, and Padina pavonica is a perennial Mediterranean-native seaweed that is commonly used for mass display. The principal aims of this reconnaissance were the isolation of various compounds from methanolic seaweeds extraction and screening the potential effect as antibacterial, and antioxidant. The micro-dilution method was used to measure antibacterial activity. Gas chromatography-mass spectrophotometry (GC. Mass) abused to analyze the chemical components of the methanolic seaweed extract. The existence of 19 secondary metabolites was discovered using GC–MS analysis: 8 different compounds for each seaweed's species. Among these bioactive compounds, 4 compounds from P. pavonica extract showed the binding affinity and ability to react with Beta-ketoacyl synthase (PDB ID 1EK4) of Escherichia coli. The phytocompounds' drug-like and poisonous characteristics were predicted. Auto Dock was used to examine the ligand receptor complexes' binding strength. T. ornate and P. pavonica had the highest activity against K. pneumonia, with 22.50 mm (0.78 µg/ml) and 22.23 mm (5.10 µg/ml) obtained, respectively. In a concentration-dependent manner, the extract components demonstrated substantial antioxidant activity. P. pavonica had the highest scavenging activity (78.00%, IC50 = 6.35 µg/ml), while ascorbic acid had a 96.45% scavenging impact. Because the chemicals bind to the Lipinski Ro5, they have drug-like characteristics. The compounds had no hepatotoxic effects. P. pavonica extract has the prospect of being used as a source of medicinal drug-like chemicals. The docking investigation found a strong correlation between the experimental results and the docking results. Finally, brown seaweed extract, particularly P. pavonica extract, demonstrated strong antibacterial, antioxidant, and free radical scavenging properties.

Keywords: Antibacterial, Antioxidant, Docking, Escherichia coli, Seaweeds

Subject terms: Drug discovery, Environmental sciences

Introduction

Seaweed, also known as marine macroalgae, has shown potential as a source of antibacterial chemicals. These organisms are rich in bioactive compounds, which can possess various biological activities, including antimicrobial properties. Numerous bioactive substances, including peptides, polyphenols, polysaccharides, and secondary metabolites, are present in it. These substances may possess antibacterial qualities, which inhibit the development of several microorganisms, including bacteria, fungi, and viruses1,2.

Alginate is a polysaccharide found in brown seaweed, and it has been studied for its antimicrobial properties. Alginate-based materials have been used in wound dressings and as coatings for medical devices to prevent infections. Carrageenan, extracted from red seaweeds, has used as a food additive and in the pharmaceutical industry. It exhibits antiviral and antibacterial properties and is used in some topical products like sexual lubricants and as an ingredient in toothpaste. Fucoidan are sulfated polysaccharides found in brown seaweeds, and they have investigated their antimicrobial potential as illustrated by Alwaleed1,3. They may inhibit the growth of various pathogens and have been studied for use in various applications, including pharmaceuticals and nutraceuticals. Terpenoids and Phenolic: some seaweed produces terpenoids and phenolic compounds with antimicrobial properties. These compounds can be used in natural products or pharmaceuticals to combat microbial infections. Seaweeds have demonstrated antibacterial activity against various pathogenic bacteria. Some studies have explored their potential in food preservation, where seaweed extracts are used to inhibit the growth of spoilage and pathogenic bacteria. Seaweed extracts have also shown antifungal properties, making them potentially useful in controlling fungal infections or as natural alternatives to synthetic antifungal agents (Hossam S. El-Beltagi et al.2).

While seaweeds are a promising source of antimicrobial chemicals, it's crucial to remember that their safety and efficacy might vary, and more research is required to fully understand their modes of action and possible applications (María J. Pérez et al.4). Additionally, seaweed extracts or compounds derived from seaweed should be thoroughly evaluated and tested for their antimicrobial properties before being used in various applications, including medicine, food preservation, and cosmetics1,5.

The fundamental goal of employing seaweeds as antimicrobial agents is to exploit their natural components and capabilities to combat microbial infections and illnesses, as well as ADMET qualities and molecular interactions of phytochemicals extracted from seaweeds with the target protein. Standard biochemical procedures and GC-Mass were used to identify the chemical ingredients. The dilution method was used to measure antibacterial activity in vitro. Finally, the ADMET properties of the selected phytochemicals were studied, as well as their molecular interface with the target protein, manipulating the ADMET lab and Auto Dock tools.

Materials and method

Seaweed collection

Turbinaria ornata, Polycladia myrica, and Padina pavonica as demonstrated in Fig. 1 algae samples were taken from the Egyptian Red Sea.6,7) and Abbott and Hollenberg8 were used to identify the algae. The algae samples were taken to the lab in plastic bags after being systematically cleaned with seawater to get rid of any unnecessary material such epiphytes and non-living matrixes. After thoroughly cleaning & rinsing with distilled H2o, the samples were legitimate to air dry at room temperature. Seaweed materials that had been shade dried were ground into a powder using an electrical mill. The samples are kept at room temperature in dark vials for later use as illustrated in Abdel Latef et al.9.

Fig. 1.

(A) Turbinaria ornata (Turner) J. Agardh, (B) Padina pavonica (Linnaeus) Thivy and (C) Polycladia myrica (S. G. Gmelin) C. Agardh three experimented algal species.

Algal extract

In a conical flask containing 50 g of dried algae and 1 l of solvent, the algal powder was immersed in methanol solvent extract for three days with the intention of prepare the algal extract. The extract was conducted in a Soxhlet apparatus for 24 h. and after evaporation in vacuum the extracts were stored at − 20 °C until used as explained by Alwaleed et al.10.

Phytochemical screening

Samples from the selected algae subjected to phytochemical inspecting for their different residents as instructed by Khan et al.11 for; carbohydrates, flavonoids, tannins, triterpenes, proteins, alkaloids, saponins, anthraquinones, cardenolides and oxidase enzyme.

Analysis the gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC-Mass)

The samples was examined by a Trace GC-TSQ mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific, Austin, TX, USA) with a direct capillary column TG-5MS (30 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 m film thickness). The temperature of the column oven started at 50 °C and was maintained for two minutes. It was then raised by 5 °C/min to 250 °C and maintained for two more minutes. Finally, it was raised by 30 °C/min to 300 °C and maintained for two more minutes. Helium was used as the carrier gas, with a steady flow rate of 1 ml/min; the injector and MS transfer lines were maintained at 270 °C and 260 °C, respectively. Diluted samples containing 1 µl were automatically injected using an Autosampler AS1300 connected to a GC in split mode, with a 4-min solvent delay. In full scan mode, EI mass spectra were obtained at 70 eV ionization voltages covering m/z 50–650. A temperature of 200 °C was chosen for the ion source. By comparing their mass spectra with those from the NIST 14 mass spectral database and WILEY 09 mass spectral database, the components were illustrated.

Test microorganisms

In vitro tests were steered to assess the antibacterial efficiency of methyl alcohols derived from marine algae extracts against clinical isolates of Bacillus subtilis, Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumonia, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Staphylococcus aureus, and Staphylococcus epidermis. The microbiology lab of the South Valley University Hospital provided the microorganisms used in this study. Nutrient agar medium, which was sterilized before being filled in 25 ml sterile cabbed test tubes, was used to cultivate the pathogenic bacteria. Before adding 0.5 ml of the homogenous inoculum mixture to each test tube and fully mixing them, the tubes were legitimate to cool room temperature. To solidify, the contents of each tube were placed in a sterile Petri plate12.

Antibacterial assay

Organisms under test Gram-negative bacteria, Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumonia, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Gram-positive bacteria, Bacillus subtilis, Staphylococcus aureus, and Staphylococcus epidermidis were identified and used as test organisms in the Microbiology Laboratory at South Valley University in Qena, Egypt.

Fortitude of minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC)

The MIC was measured using the micro-dilution method with serially diluted (2 ×) algal extracts13. T. ornata, P. myrica, and P. pavonica extracts' MICs were estimated by diluting concentrations ranging from 0.0 to 100 mg/ml. In a test tube, an equal volume of each extract and nutritional broth was mixed. Each tube received 0.1 ml of standardized inoculum (1–2 107 cfu/ml). For each test batch, 2 control tubes containing the growth medium, saline, and inoculum were kept.

Antioxidant activity

The antioxidant influence of methanolic extract was determined, as reported methods described by Blois14 using DPPH (diphenyl-1- picrylhydrazyl) utilizing ultraviolet (UV) spectrophotometry (Shimadzu 2401PC70 spectrophotometer) at 517 nm. Every extract (2 mg) was diluted in 100 mL of methanol to make a compound stock solution. Correspondingly, a 1 mM DPPH solution was made by dissolving 9.5 g of DPPH in 25 mL of methanol. Using the dilution formula, various concentrations of each component were created, including 5, 10, 30, 20, 60, 80, and 100 µg/ml. Currently, 4 mL of methanol sample solution containing 510 µg/ml and control were combined with 1 mL of DPPH solution. After 30 min of darkness, the absorbance of each sample was valued using UV spectrophotometry at a wavelength of 517 nm. An increase in DPPH radical scavenging is indicated by a decrease in DPPH absorbance. The proportion of radical scavenging activity is used to express the DPPH scavenging of free radicals. The antioxidant activity percentage was computed using the following formula.

DPPH% = (A0) control abs—(A1) Sample Abs × 100/(A0) control abs.

A0 = control represents the absorbance of the blank sample.

A1 = sample represents the absorbance of the standard sample.

Statistical analysis

All values were reported as means with standard deviations. In SPSS, version 20, mean comparisons were performed using a one-way ANOVA test monitored by the Tukey HSD test.

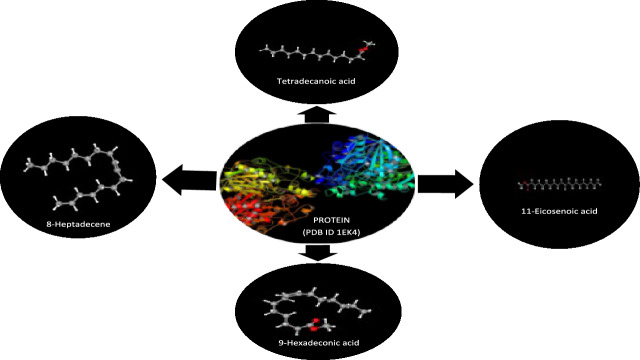

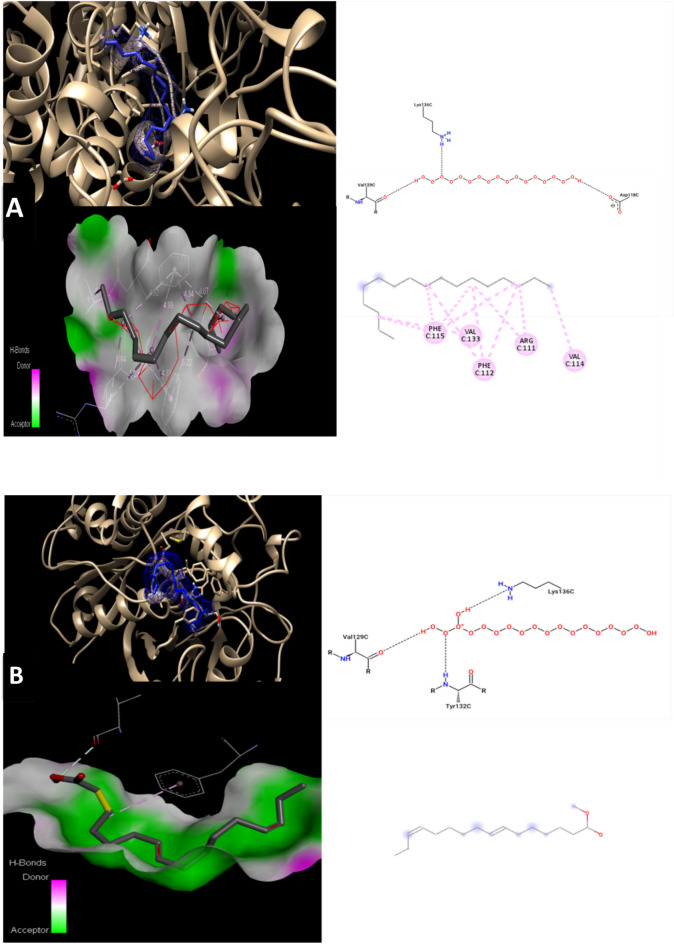

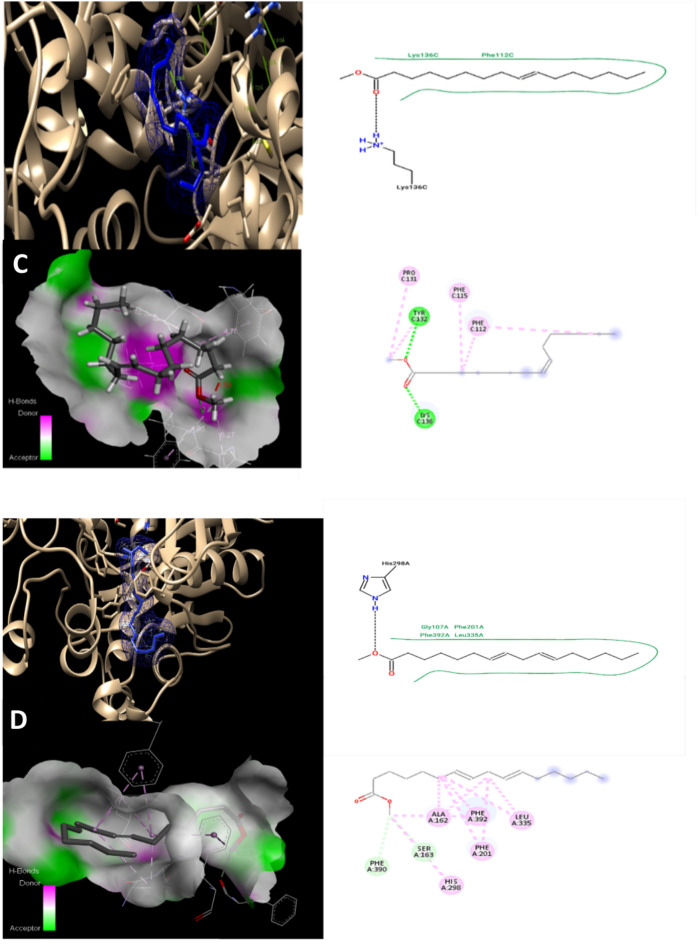

Docking of molecules

A computer method for figuring out ligand interactions inside target protein active regions is called molecular docking 23. Using molecular docking, the most effective chemical among the derivatives of seaweed extract to block bacterial proteins was identified. For this, PDB structures of Escherichia coli's Beta-ketoacyl [acyl carrier protein] synthase (PDB ID 1EK4) was downloaded from www.rcsb.org; seaweed derivatives were then docked into these proteins' binding sites utilizing the docking protocol instigated in the Molecular Operating Environment (MOE) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

The Beta-ketoacyl synthase (PDB ID 1EK4) (center). The chemical structure of 8-Heptadecene, Tetradecanoic acid methyl ester (CAS), 11-Eicosenoic acid methyl ester, and 9-hexadecenoic acid, methyl ester individually docked with 1EK4.

Physicochemical and pharmacokinetic properties

The Swiss ADME program was utilized to assess the identified compounds' physicochemical and pharmacokinetic properties. Each compound's streamlined molecular-input line-entry system (SMILES) was retrieved from Pub-Chem and entered the Swiss ADME program. The physicochemical parameters as molecular weight (MW), number of hydrogen bond acceptors (N), number of hydrogen bond donors (NHBD), number of heavy metals (NHM), and rotatable bonds (NRB) are then listed. Lipophilicity was calculated utilizing consensus log P (c Log P)15. Three models, ESOL, Ali, and SILICOS-IT, were used to investigate solubility (Log S). Predicted pharmacokinetic features include human intestinal absorption (HIA), blood–brain barrier (BBB) penetration, chemical collaboration with P-glycoprotein (P-gp), and metabolism16.

Prediction of drug-likeness

Swiss ADME tool17 was utilized to examine the compounds' drug-likeness constructed on the Lipinski rule of five (Ro5). Ro5 states that MV < 500 Da, log P value ≤ 5, NHBD ≤ 5, and NHBA ≤ 10 are requirements for drug-like compounds. Furthermore, compounds should not violate more than one Ro518 and the NRB should be < 10. Based on the phytochemicals' MV, c Log P, NHBD, and NHBA, the bioavailability ratings were calculated19.

Toxicological investigation

The toxicological properties were estimated using the ADMET lab online tool on the web server. For each molecule obtained from Pub Chem and loaded into the ADMET lab, the simple molecular-input line-entry system (SMILES) was used. Following that, the compounds were tested for human hepatotoxicity (HHT) and skin sensitivity (Skin Sen) as illustrated by20.

Ethics approval

This project has received ethical approval from the Research Ethics Committee, Faculty of Science, South Valley University, Qena, Egypt, (REC-FScSVU) with ethics reference number (001/07/24).

Result and discussion

Seaweed extracts as antimicrobial agents can vary depending on the specific seaweed species, the extraction method, the type of microorganisms tested, and the intended application. Research on the antimicrobial properties of seaweed extracts has shown promising results in many cases, but it's important to note that not all seaweed extracts exhibit the same level of antimicrobial activity.

Bioactive compounds

Natural compounds obtained from seaweed broadly used to treat a variety of ailments, moreover these phytochemicals give a very good prototype for the identification of novel medications2.

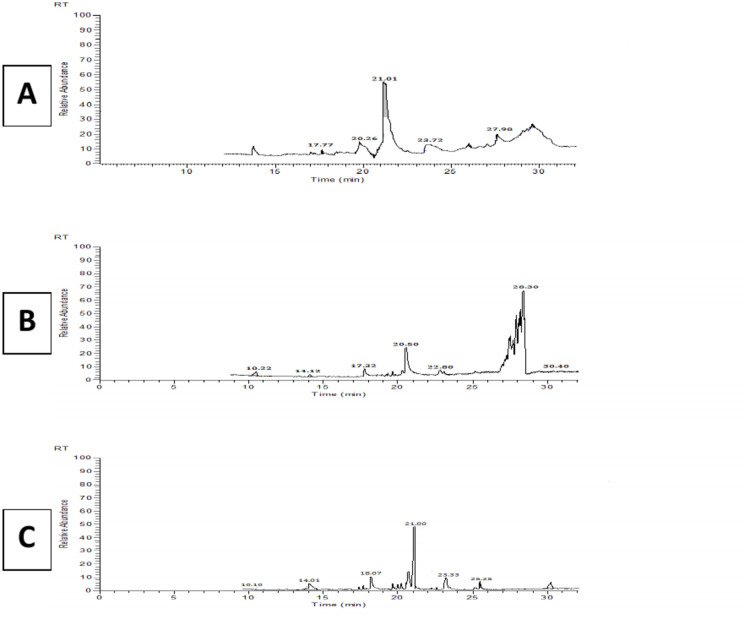

The discovery and isolation of bioactive chemicals in seaweed extracts can shed light on the specific antimicrobial agents responsible for the reported effects. Seaweed extracts may exhibit synergistic effects when combined with conventional antimicrobial agents. This can enhance their overall efficacy and potentially reduce the development of resistance. The bioactive compounds found in seaweeds that exhibit antimicrobial properties are diverse and can include various classes of compounds. Three types of brown algae have demonstrated antibacterial properties because of the presence of bioactive compounds in their tissues. Figure 3 illustrated the Gc-mass of bioactive compounds from brown seaweeds & their potential antimicrobial outcomes illustrated in Tables 1, 2 and 3.

Fig. 3.

Chromatograms of the GC–MS analysis of (a) Turbinaria ornata, (b) Polycladia myrica, and (c) Padina pavonica methanolic extract.

Table 1.

Compounds recognized by GC–MS in Turbinaria ornata methanolic extract.

| RT (min) | Compound | Mol. formula | Mol. weight | Peak area (%) | Interactive chemical structure model | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 19.90 | Cyclohexene,1,5,5-trimethyl-6-acetylmethyl | C12H20O | 180 | 1.34 |  |

|

| 20.26 | Phytol, acetate | C22H42O2 | 338 | 4.61 |  |

|

| 20.50 | 2,2-DIDEUTERO OCTADECANAL | C18H34D2O | 268 | 1.17 |  |

|

| 21.01 | Hexadecenoic acid, methyl ester | C17H34O2 | 270 | 67.12 |  |

|

| 23.72 | 16-Octadecenoic acid, methyl ester (CAS) | C19H36O2 | 296 | 9.93 |  |

|

| 27.90 | 9-Hexadecenoic acid, 9-octadecenyl ester(Z,Z)- | C34H64O2 | 504 | 5.99 |  |

|

| 28.30 | Oleyl oleate | C36H68O2 | 532 | 2.03 |  |

|

| 28.44 | Lucenin 2 | C27H30O16 | 610 | 2.80 |  |

|

RT (min): Retention time, Mol. Formula: Molecular formula, Mol. Weight: Molecular weight.

Table 2.

Compounds identified by GC–MS in Polycladia myrica methanolic extract.

| RT (min) | Compound | Mol. formula | Mol. weight | Peak area (%) | Interactive chemical structure model | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 17.70 | Methyl tetradecanoate | C15H30O2 | 242 | 2.10 |  |

|

| 19.26 | Cyclopropane octanoic acid, 2-octyl-, methyl ester | C20H38O2 | 310 | 9.77 |  |

|

| 20.29 | 9-Hexadecenoic acid, methyl ester | C17H32O2 | 268 | 0.94 |  |

|

| 20.51 | Hexadecenoic acid, methyl ester | C17H34O2 | 270 | 14.90 |  |

|

| 22.82 | 10-Octadecenoic acid, methyl ester | C19H36O2 | 296 | 5.04 |  |

|

RT (min): Retention time, Mol. Formula: Molecular formula, Mol. Weight: Molecular weight.

Table 3.

Compounds identified by GC–MS in (a) Padina pavonica methanolic extract.

| RT (min) | Compound | Mol. formula | Mol. weight | Peak area (%) | Interactive chemical structure model |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 17.38 | 8-Heptadecene | C17H34 | 238 | 1.34 |  |

| 18.07 | Tetradecanoic acid, methyl ester | C15H30O2 | 242 | 11.25 |  |

| 20.55 | 7,10-Hexadecadienoic acid, methyl ester | C17H30O2 | 266 | 1.12 |  |

| 21.00 | 9-hexadecenoic acid, methyl ester | c16h30o2 | 254 | 12.98 |  |

| 23.33 | 6,9,12Octadecatrienoic acid, methyl ester | C19H32O2 | 292 | 11.03 |  |

| 25.25 | 11-Eicosenoic acid, methyl ester | C21H40O2 | 324 | 3.09 |  |

RT (min): Retention time, Mol. Formula: Molecular formula, Mol. Weight: Molecular weight.

Figure 3 shows the spectrum of chromatograms of the GC–MS analysis of seaweed methanolic extract. When the peaks obtained were matched to those in the NIST libraries, 8 compounds were detected in the T. ornata extract, five compounds in the P. myrica extract, and six compounds in the P. pavonica extract. These chemicals were predominantly alcohols, esters, and long chain hydrocarbons with structures to substances previously reported in the literature in other marine algae (Abdel Latef et al. 2021). GC–MS profile of P. pavonica (Fig. 3) revealed the presence of 9-Hexadecenoic acid, methyl ester, with the largest peak area at 12.98%. There are literature studies on the methyl ester of hexadecenoic acid's biological actions, which include cytotoxic, antioxidant, and antidiabetic effects. Consequently, one could speculate that the presence of this key component, fecosterol and derivatives of hexadecenoic acid, may be the cause of the antioxidant and anti-proliferative properties of P. pavonica that were noted in the previous study by21.

Preliminary phytochemical screening

Unsaturated sterols, Flavonoids, Carbohydrates, Proteins, Tannins, and Coumarin were found in preliminary phytochemical screening of the 3 algae (T. ornata, P. myrica, and P. pavonica) under inquiry methanolic extract. According to the medicinal data, seaweed may have a variety of chemical elements. The tested phytochemicals were shown to have pharmacologically significant qualities such as antibacterial and cytotoxic capabilities2. The presence of these phytochemical substances is liable for the antibacterial activity.

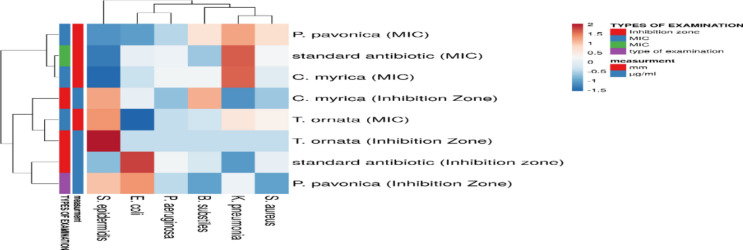

Inhibition of bacterial growth

With a zone of inhibition extending from 6 to 26 nm, the methanolic extract showed an excellent antibacterial action against the selected bacterial strains, including Gram-positive Bacillus subtilis, Streptococcus epidermis, and Bacillus subtilis, as well as Gram-negative bacteria, Klebsiella pneumonia illustrates the strains that were investigated as demonstrated in Fig. 4. The antibacterial sensitivity of extracts from T. ornata, P. myrica, and P. pavonica was tested against strains of both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria (Table 4). Our extract validated excellent activity against the preferred bacterial strain, incorporating the antibacterial activity of T. ornata, P. myrica and P. pavonica revealed that the highest activities; 22.50 ± 0.50 mm (0.78 µg/ml) and 22.23 ± 0.25 mm (5.10 µg/ml) were obtained against K. pneumonia by T. ornata and P. pavonica, respectively (Table 4). The extract indicated antibacterial activity versus B. subtilis and S. aureus. It has been discovered across the world that irrational antibiotic use is to blame for the propagation of dangerous bacteria that develop resistance to various antibiotic classes22. This has reduced the advanced harm in antibiotic treatment effectiveness to a degree that depends on the clonal spread's opulence, the complexity of key alterations, and the pace of horizontal gene transfer. The prevalence of infections brought on by germs resistant to several drugs has sharply increased worldwide. Several new medicines have been discovered to treat serious illnesses, but bacterial pathogens have quickly developed multidrug resistance genes to combat antibiotic resistance Mohammed Harris et al.23.

Fig. 4.

Antimicrobial activity of algae extracts towards E. coli, K. pneumonia, P. aeruginosa, S. aureus, S. epidermis, and B. subtilis. represented by heatmap. A scale ranging from a minimum of (blue) to a maximum (red) was used to represent size of inhibition diameter calculated, as average values of triplicates, after 24 h of incubation at 37 °C against different algal extracts.

Table 4.

Antibacterial Activity of T. ornata, P. myrica and P. pavonica extract.

| Bacterial strain | Standard antibiotic | T. ornata | P. myrica | P. pavonica | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inhibition zone (mm) | MIC (µg/ml) | Inhibition zone(mm) | MIC (µg/ml) | Inhibition zone(mm) | MIC (mg/ml) | Inhibition zone(mm) | MIC (µg/ml) | |

| E. coli |

20.00c ± 1.00 |

3.98 |

20.23a ± 0.68 |

1.80 |

16.50b ± 0.50 |

30.00 |

18.37a ± 0.40 |

8.80 |

| K. pneumonia |

26.00d ± 1.00 |

0.50 |

22.05bc ± 0.50 |

0.78 |

20.27c ± 0.64 |

1.80 |

22.23d ± 0.25 |

5.10 |

| P. aeruginosa |

20.27c ± 0.64 |

1.98 |

21.43ab ± 0.51 |

1.90 |

17.50b ± 0.50 |

12.56 |

19.27b ± 0.26 |

3.50 |

| S. aureus |

20.57c ± 0.51 |

1.80 |

22.30bc ± 0.61 |

3.90 |

17.00b ± 1.00 |

14.33 |

21.40c ± 0.36 |

1.90 |

| S. epidermidis |

15.00a ± 1.00 |

0.88 |

23.33c ± 0.76 |

5000 |

14.40a ± 0.53 |

60.50 |

18.20a ± 0.20 |

7.80 |

| B. substilis |

17.53b ± 0.50 |

1.50 |

21.50ab ± 0.50 |

15.44 |

17.50b ± 0.50 |

59.00 |

21.23c ± 0.25 |

1.88 |

Data exemplified as mean ± SD of 3 distinct sets of individual experiments in each column.

Means in the same column not followed by the same letter are significantly different (p<0.001).

Antioxidant effect of methanolic extracts

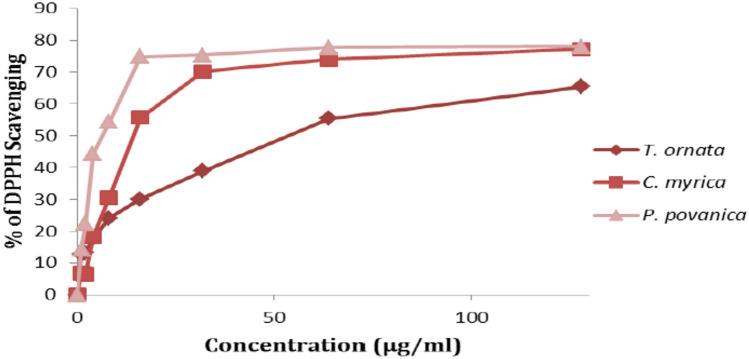

Antioxidant scavenging activity is very advantageous when treating specific conditions. Since it is a sensitive method for assessing the antioxidant activity of different algal extracts, the DPPH assay is the most used method for assessing antioxidant activity24. The methanolic extracts of T. ornata, P. myrica, and P. pavonica showed concentration-dependent DPPH radical scavenging action (Fig. 5). P. pavonica and P. myrica contributed the highest levels of scavenging activity (78.00%, IC50 = 6.35 µg/ml and 77.23%, IC50 = 15.99 µg/ml, respectively). On the other hand, T. ornata exhibited 65.45% scavenging activity (IC50 = 50.33 µg/ml).

Fig. 5.

Antioxidant Activity of T. ornata, P. myrica and P. pavonica methanolic extract.

Antioxidants are naturally occurring molecules that tend to scavenge free radicals and inhibit certain oxidative chain reactions, therefore protecting the human body from potentially detrimental effects. The human body's low levels of certain elements prevent an oxidizable substrate from oxidizing. Antioxidants are important in delaying the onset of chronic illnesses such as cancer, atherosclerosis, inflammatory diseases, and heart disease. Antioxidants generated from medicinal seaweeds, as revealed by21,25, play an important role in augmenting endogenous antioxidants in the fight against oxidative stress. Numerous clinical, epidemiological, and experimental evidence suggest that seaweed based on natural antioxidants can help prevent chronic diseases. Because of their low toxicity and high antioxidant capacity, active phytochemicals from plants are being studied for their potential to reduce the hazard of diseases.

Irina and Constantin26 demonstrated that different techniques are used to determine antioxidant activity, but DPPH has recently gained prominence due to its ease of use and simplicity. Our findings suggested that the obsolete potential of methanolic extract was concentration dependent.

Molecular weight (MW) of the compounds

The molecular characteristic known as molecular weight (MW) affects the permeability and bioavailability of medicinal compounds. Permeability and bioavailability decrease with increasing molecular weight (beyond 500 g/mol), and vice versa. Table 5 displays the molecular weights of the compounds. Every component was found to have a molecular weight ≥ 500 g/mol, suggesting that they may all have acceptable bioavailability as demonstrated by Imad et al.16

Table 5.

The physicochemical properties and lipophilicity of detected compound.

| Compounds | Physicochemical Properties | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MW(g/mol) | NHBD | NHBA | NRB | C Log Po/w | ||||

| 8-Heptadecene (C17H34) | 238.45 | 0 | 0 | 13 | 6.61 | |||

| Tetradecanoic acid, methyl ester (CAS) (C15H30O2) | 242.40 | 0 | 2 | 13 | 4.81 | |||

| 7,10-Hexadecadienoic acid, methyl ester (CAS) (C17H30O2) | 266.42 | 0 | 2 | 13 | 84.17 | |||

| 9-Hexadecenoic acid, methyl ester (C16H30O2) | 254.41 | 0 | 2 | 13 | 4.86 | |||

| 6,9,12Octadecatrienoic acid, methyl ester (C19H32O2) | 292.46 | 0 | 2 | 14 | 5.50 | |||

| 11-Eicosenoic acid, methyl ester(C21H40O2) | 324.5 | 0 | 2 | 18 | 4.81 | |||

| Water solubility | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Log S (ESOL) | Class | Log S (Ali) | Class | Log S (SILICOS-IT) | Class | |||

| 8-Heptadecene | − 5.81 | MS | − 8.36 | PS | − 6.01 | PS | ||

| Tetradecanoic acid, methyl ester (CAS) | − 4.52 | MS | − 6.76 | PS | − 5.21 | MS | ||

| 7,10-Hexadecadienoic acid, methyl ester (CAS) | − 4.25 | MS | − 6.06 | PS | − 4.57 | MS | ||

| 9-Hexadecenoic acid, methyl ester | − 4.23 | MS | − 6.15 | PS | − 4.89 | MS | ||

| 6,9,12Octadecatrienoic acid, methyl ester | − 4.59 | MS | − 6.46 | PS | − 4.65 | MS | ||

| 11-Eicosenoic acid, methyl ester | − 4.50 | MS | − 6.75 | PS | − 4.55 | MS | ||

| Pharmacokinetics | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GI a | BBB p | P-gap s | CYP1A2i | CYP2C19i | CYP2C9i | CYP2D6i | Log Kp | |

| 8-Heptadecene | No | No | Ye | No | No | No | − 1.73 | Low |

| Tetradecanoic acid, methyl ester (CAS) | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | − 3.23 | High |

| 7,10-Hexadecadienoic acid, methyl ester (CAS) | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | − 3.85 | High |

| 9-Hexadecenoic acid, methyl ester | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | − 3.85 | High |

| 6,9,12Octadecatrienoic acid, methyl ester | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | − 3.85 | High |

| 11-Eicosenoic acid, methyl ester | Yes | No | No | No | No | Yes | − 3.85 | High |

| Drug likeness | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Satisfactory | No of violations | Bioavailability score | ||||||

| 8-Heptadecene | Yes | 1 Violation | 0.55 | |||||

| Tetradecanoic acid, methyl ester (CAS) | Yes | 1 | 0.55 | |||||

| 7,10-Hexadecadienoic acid, methyl ester (CAS) | Yes | 1 | 0.55 | |||||

| 9-Hexadecenoic acid, methyl ester | Yes | 1 | 0.55 | |||||

| 6,9,12Octadecatrienoic acid, methyl ester | Yes | 1 Violation | 0.55 | |||||

| 11-Eicosenoic acid, methyl ester | Yes | 1 Violation | 0.55 | |||||

| Toxicity | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HHT | Skin sin | Carcinogenicity | Respiratory toxicity | |||||

| 8-Heptadecene | − − | + + + | − | − | ||||

| Tetradecanoic acid, methyl ester (CAS) | − − | + + + | − | + + | ||||

| 7,10-Hexadecadienoic acid, methyl ester (CAS) | − | + + + | − | + | ||||

| 9-Hexadecenoic acid, methyl ester | − − | + + + | − | + + | ||||

| 6,9,12Octadecatrienoic acid, methyl ester | + + | + + + | − − | − | ||||

| 11-Eicosenoic acid, methyl ester | − − | + + + | − | + + | ||||

The prediction probability values altered into six symbols: 0–0.1( − − ), 0.1–0.3( − ), 0.3–0.5( − ), 0.5–0.7(+), 0.7–0.9(+ +), and 0.9–1.0(+ + +).

Nhba and Nhbd of the compounds

According to David and Hans27, hydrogen bonding is essential for both membrane penetration and molecule absorption in the gastrointestinal tract. Furthermore, the ligand receptor binding affinity is influenced by hydrogen bond interactions. The NHBD (sum of OHs and NHs) and NHBA (sum of Os and Ns) calculations are used to determine the hydrogen bond strength in the molecules, as shown in Table 5.

Molecular docking

Molecular docking is an algorithmic the methanolic seaweed extract chemical has the potential to evolve into a broad-spectrum antibiotic substance, meaning that it can kill both of gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria, according to the clear zone and MIC values. One of four pathways underlies antibacterial activity; the other three include the inhibition or control of enzymes involved in protein synthesis, nucleic acid metabolism and repair, or cell wall formation, respectively. Moreover, molecular docking was used to determine the mode of action of drugs derived from seaweed extracts. Research on docking inhibition will focus on bacteria that are resistant. Finding novel naturally occurring antibacterial agents with a fresh mode of action is still a top goal on a worldwide scale. Beta-ketoacyl synthase (PDB ID 1EK4) was found to have a binding energy of − 5.1 kcal/mol, − 5.5 kcal/mol, − 4.1 kcal/mol, and − 6.5 kcal/mol, with 8-Heptadecene, 7,10-Hexadecadienoic acid, methyl ester (CAS), 9-Hexadecenoic acid, methyl ester, and 11-Eicosenoic acid, methyl ester, respectively (Table 6). The binding energy (Kcal/mol) would be used to correlate and investigate the binding affinity of various ligands or inhibitors with their corresponding protein target as illustrated in Fig. 6. In general, the lower the binding energy, the greater the ligand’s affinity for the receptor protein will be. As a result, the ligand with the highest affinity can be taken forward as a candidate for further research.

Table 6.

Molecular Docking value for phytocompounds of Padina pavonica extract against Beta-ketoacyl synthase (PDB ID 1EK4).

| S. No | Ligands | Affinity (Kcal/mol) | H. Bond interaction | No. of other residual interactions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 8-Heptadecene | − 5.1 | PHE A:392, GLY A:391 | 7 |

| 2 | 7,10-Hexadecadienoic acid, methyl ester (CAS) | − 5.5 | SER A:163, PHE A:392, GLY A:391 | 8 |

| 3 | 9-Hexadecenoic acid, methyl ester | − 4.1 | SER A:163, PHE A:392, GLY A:391 | 8 |

| 4 | 11-Eicosenoic acid, methyl ester | − 6.5 | GLY A:391, PHE A:392 | 13 |

Fig. 6.

Molecular docking models 2D and 3D interactions for phytocompounds of Padina pavonica extract (A); 8-Heptadecene, (B); 7,10-Hexadecadienoic acid,methyl ester, (C); 9-Hexadecenoic acid, methyl ester, and (D); 11-Eicosenoic acid, methyl ester. against Beta-ketoacyl synthase (PDB ID 1EK4).

Antibacterial medications work by inhibiting protein synthesis and preventing metabolism28. The antibiotics block these pathways by interacting with cell proteins that carry out particular functions. The crucial enzyme included in beta-ketoacyl synthase (PDB ID 1EK4) is evolutionarily conserved and catalyzes the biosynthetic process that bacterial cells use to synthesize DNA29. Since ciprofloxacin inhibits DNA gyrase, which is required to separate bacterial DNA and cause the inhibition of cell division, we chose beta-ketoacyl synthase as our target protein with the intention of investigate the molecular interactions between target protein and synthesized ligands.

Based on the current study's findings, we proposed Padina Pavonica for further separation of novel compounds and synthesis of its derivatization to discover strong antibacterial and antioxidant compounds with potential medical applications.

Conclusions

Further investigation of seaweed is needed to identify the active substances present in the algae that are responsible for antioxidant and antimicrobial activity. The present work is focused on the determination of antioxidant and antimicrobial activity, minimum inhibitory concentrations and phytochemical constituents using GC–MS of methanolic extracts of T. ornata, P. myrica, and P. pavonica seaweeds. The results of this work suggest that the algae contain substances that can inhibit the growth of microorganisms and have antioxidant activity. The results emphasized the antibacterial activity of seaweed extracts against pathogens in general, Analytical spectrum and chromatograms revealed the presence of various groups of chemical compounds which facilitate antibiotic activity. In-silico docking investigation of pathogenic proteins with the phytochemical ligands recommend that phytol has high affinity for G + and G − bacterial toxicity. Our study contributes to the evidence that seaweed has antimicrobial and antioxidant activity and can inhibit the growth of microorganisms, as well as to the potential of seaweed extracts for pharmacological applications.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully Acknowledge Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2024R356), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Also, this work was supported by the Deanship of Scientific Research, Vice Presidency for Graduate Studies and Scientific Research, King Faisal University, Saudi Arabia [GrantA174].

Author contributions

E.A.A. conceived the original idea and carried out the experiments. N.M.A. and A.T.M. analyzed the data. M.A.A. and A.S.A. wrote and revised the M.S.

Funding

Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2024R356), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Extended thank for Deanship of Scientific Research, Vice Presidency for Graduate Studies and Scientific Research, King Faisal University, Saudi Arabia [GrantA174].

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or in our supplementary information files.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

The original online version of this Article was revised: The original version of this Article contained an error in the grant number mentioned in the Acknowledgement and Funding section. Full information regarding the corrections made can be found in the correction for this Article.

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Change history

11/8/2024

A Correction to this paper has been published: 10.1038/s41598-024-77714-x

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-024-70620-2.

References

- 1.Eman, A. A. Biochemical composition and nutraceutical perspectives Red Sea seaweeds. Am. J. Appl. Sci16(12), 346–354 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hossam, S. E. B. et al. phytochemical and potential properties of seaweeds and their recent applications: A review. J. Mar. Drugs20, 342. 10.3390/md20060342 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ayrapetyan, O. N. et al. Antibacterial properties of fucoidans from the Brown Algae Fucus vesiculosus L. of the Barents Sea. Biology (Basel).10(1), 67. 10.3390/biology10010067 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.María José, P., Elena, F. & Herminia, D. Antimicrobial action of compounds from marine seaweed. Mar. Drugs14(3), 52. 10.3390/md14030052 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arafat, A. H. A., Zaid, A. & Eman, A. A. Influences of priming on selected physiological attributes and protein pattern responses of salinized wheat with extracts of Hormophysa cuneiformis and Actinotrichia fragilis. Agronomy11, 545. 10.3390/agronomy11030545 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aleem, A. A. Contributions to the study of the marine algae of the Red Sea. Marine algae from Obhor, in the vicinity of Jeddah Saudi Arabia. Bull. Fac. Sci. KAUJ2, 99–118 (1978). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aleem, A. A. Contributions to the study of the marine algae of the Red Sea. New or little-known algae from the west coast of Saudi Arabia. Bull. Fac. Sci. KAUJ5, 1–49 (1981). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abbott, L. A. & Hollenberg, L. G. Marine Algae of California Stanford (University Press, 1976). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abdel Latef, A. A. H. et al.Sargassum muticum and Jania rubens regulate amino acid metabolism to improve growth and alleviate salinity in chickpea. Sci. Rep.7, 10537. 10.1038/s41598-017-07692-w (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eman, A. A., Asmaa, J., Naglaa, R. A. K. & Hamdy, G. Evaluation of the pancreatoprotective effect of algal extracts on Alloxan-induced diabetic rat. J. Bioactive Carbohyd. Dietary Fibre24, 100237. 10.1016/j.bcdf.2020.100237 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khan, A. M. et al. Phytochemical analysis of selected medicinal plants of Margalla Hills and surroundings. J. Med. Plants Res.5(25), 6055–6060 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mtolera, M.S.P. & Semesi, A.K. Antimicrobial Activity of Extracts from Six Green Algae from Tanzania, in Current Trends in Marine Botanical Research East African Region, (eds Borg, M., Semesi, A., Pederson, M. & Bergman, B.) Sidal SAREC Uppsala (1996).

- 13.Zain, M. E., Awaad, A. S., Al-Outhman, M. R. & El-Meligy, R. M. Antimicrobial activities of Saudi Arabian desert plants. Phytopharmacol.2(1), 106–113 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blois, M. S. Antioxidant determinations by the use of a stable free radical. Nature26, 1199–1200 (1958). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Franco, G. et al. iLOGP: a simple, robust, and efficient description of n-octanol/water partition coefficient for drug design using the GB/SA approach. J. Chem. Inf. Model.54(12), 3284–3301 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Imad, A. et al. Computational pharmacology and computational chemistry of 4-hydroxyisoleucine: Physicochemical, pharmacokinetic, and DFT-based approaches. Front. Chem.10.3389/fchem.2023.1145974 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Antoine, D., Olivier, M. & Vincent, Z. Swiss ADME: a free web tool to evaluate pharmacokinetics, drug-likeness and medicinal chemistry friendliness of small molecules. J. Sci. Rep.7, 42717. 10.1038/srep42717 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Conrad, V. S. et al. Challenges in natural product-based drug discovery assisted with in silico-based methods. RSC Adv.13, 31578–31594 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barreau, N., Marsillac, S., Bernede, J. C. & Barreau, A. Investigation of β-In2S3 growth on different transparent conductive oxides. Appl. Sur. Sci.161(1–2), 20–26 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Olaokun, O. O. & Zubair, M. S. Antidiabetic Activity, Molecular Docking, and ADMET properties of compounds isolated from bioactive ethyl acetate fraction of ficus iutea leaf extract. Molecules.28(23), 7717. 10.3390/molecules28237717 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kavitha, M. & Vidhya, V. I. Differential growth inhibition of cancer cell lines and antioxidant activity of extracts of red, brown, and green marine algae In Vitro Cell. Dev. Biol. Animal49, 324–334. 10.1007/s11626-013-9603-7 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee Ventola, C. The antibiotic resistance crisis. P T40(4), 277–283 (2015). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harris, M., Tracy, F., Diana, I., Nicole, J. & Davis, N. B. Genetic factors that contribute to antibiotic resistance through intrinsic and acquired bacterial genes in urinary tract infections. Microorganisms11, 1407. 10.3390/microorganisms11061407 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gulcin, I. & Alwasel, S.H. DPPH radical scavenging assay. Processes11, 2248. 10.3390/pr11082248 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Michalak, I. et al. Antioxidant effects of seaweeds and their active compounds on animal health and production - a review. Vet Q.42(1), 48–67. 10.1080/01652176.2022.2061744 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Irina, G. M. & Constantin, A. Analytical methods used in determining antioxidant activity: A review. Int. J. Mol. Sci.22(7), 3380. 10.3390/ijms22073380 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.David, D. & Hans, L. Intestinal permeability and drug absorption: predictive experimental computational and in vivo. Approaches. Pharmaceutics11, 411. 10.3390/pharmaceutics11080411 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wanda, C. R. An overview of the antimicrobial resistance mechanisms of bacteria. AIMS Microbiol.4(3), 482–501 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cronan, J. E. & Thomas, J. Bacterial fatty acid synthesis and its relationships with polyketide synthetic pathways. Methods Enzymol.459 395–433. 10.1016/S0076-6879(09)04617-5 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data is provided within the manuscript or in our supplementary information files.