Abstract

Importance:

Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists were first approved for the treatment of type 2 diabetes in 2005. Demand for these drugs has increased rapidly in recent years, as indications have expanded, but they remain expensive.

Objective:

To analyze how manufacturers of brand-name GLP-1 receptor agonists have used the patent and regulatory systems to extend periods of market exclusivity.

Evidence Review:

We used the annual Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations to identify GLP-1 receptor agonists approved from 2005-2021 and to record patents and non-patent statutory exclusivities listed for each product. We used Google Patents to extract additional data on patents, including whether each was obtained on the delivery device or another aspect of the product. Our primary outcome was the duration of expected protection from generic competition, defined as the time elapsed from FDA approval until expiration of the last-to-expire patent or regulatory exclusivity.

Findings:

On the 10 GLP-1 receptor agonists included in the cohort, drug manufacturers listed with the FDA a median of 19.5 patents (interquartile range [IQR]: 9.0-25.8) per product, including a median of 17 patents (IRQ: 8.3-22.8) filed before FDA approval and 1.5 (IQR: 0-2.8) filed after FDA approval. Fifty-four percent of all patents listed on GLP-1 receptor agonists were on the delivery devices rather than active ingredients. Manufacturers augmented patent protection with a median of 2 regulatory exclusivities (IQR: 0-3) obtained at approval and 1 (IQR: 0.3-4.3) added after approval. The median total duration of expected protection after FDA approval, when accounting for both pre- and post-approval patents and regulatory exclusivities, was 18.3 years (IQR: 16.0-19.4). No generic firm has successfully challenged patents on GLP-1 receptor agonists to gain FDA approval.

Conclusions and Relevance:

Patent and regulatory reform is needed to ensure timely generic entry of GLP-1 receptor agonists.

Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists make up a class of medications used for the treatment of type 2 diabetes and obesity.1,2 The first GLP-1 receptor agonist to receive Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval was exenatide in 2005,3 and the FDA subsequently approved several other drugs with the same mechanisms of action. Over 15 years later, these products remain costly with mean monthly net prices rising from approximately $200 in 2007 to over $600 in 2017,4 and median annual out-of-pocket costs in Medicare Part D exceeding $1,500 in 2019.5 Manufacturers earned more than $10 billion on GLP-1 agonists in the US alone in 2021.6

New brand-name drugs are routinely sold at high prices in the US, and manufacturers often sustain these elevated prices for extended periods by obtaining patents and non-patent statutory exclusivities and leveraging these exclusivities to delay or block generic competition.7 Patents are government-granted rights that typically last 20 years from the date of filing and allow manufacturers to exclude potential competitors from selling versions of the product being protected. Drug manufacturers obtain patents not only on the active ingredients in their products (typically obtained around the time when the drug is discovered or synthesized), but also on aspects of drug formulations, methods of use, and delivery devices.8

Most marketed GLP-1 receptor agonists are drug-device combinations with active ingredients sold together with their subcutaneous injector pens. Drug-device combinations are especially susceptible to market exclusivity extensions because of the potential for patents on the delivery devices to block generic competition for many years after patents on the underlying active ingredients expire.9–13 Device patents expiring later than other patents may force generic firms to either wait until these patents expire before market entry or undertake lengthy and costly patent challenges. In addition, they may complicate establishment of generic competition by increasing the number of patents that a generic firm must contest to gain FDA approval. For inhalers, another class of drug-device combination products, the median number of patents at FDA approval has steadily increased from 2 (for inhalers approved 1986-1997) to 8 (1998-2008) to 11 (2009-2020), with more than half of these patents covering inhaler delivery devices.10

The US Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO), which issues patents, has recently embarked on a collaborative initiative with the FDA to better understand and promote the quality of patenting practices in the pharmaceutical industry.14 GLP-1 receptor agonists are widely used in the US with rapidly growing market share, as indications have expanded into weight loss, and we sought to evaluate the patent portfolios of these products to assess the barriers that remain to generic competition. Using a database of all patents and non-patent statutory exclusivities covering GLP-1 receptor agonists FDA-approved from 2005 to 2021, we determined the expected duration of market protection, the timing of generic entry, and the results of challenges to these patents brought by generic firms.

Study Data and Methods

Cohort Identification

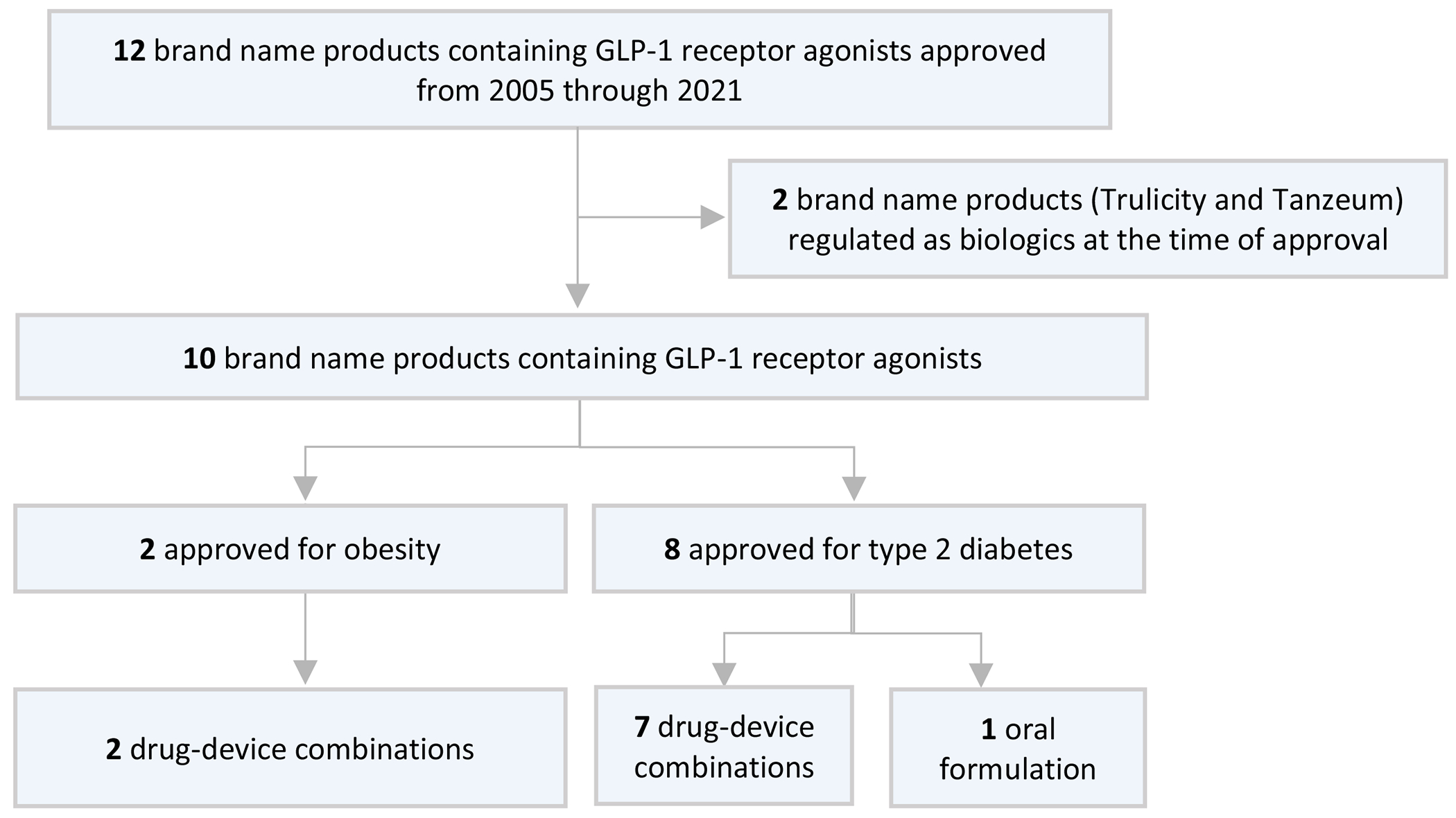

We used the FDA Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations (Orange Book)15 and product labels from Drugs@FDA16 to identify all GLP-1 receptor agonists approved from 2005-2021 (see eMethods). GLP-1 receptor agonists are generally regulated as small-molecule drugs, which means that manufacturers list key patents on them in the Orange Book. However, two GLP-1 receptor agonists—dulaglutide (Trulicity) and albiglutide (Tanzeum), both approved in 2014—have been regulated as biologics since their approval and therefore have different statutory exclusivity periods and lack the same level of patent transparency. Given these important regulatory differences, these two drugs were excluded from our analysis.

Data Extraction

Approval dates were obtained from Drugs@FDA. We used annual Orange Books to record the patents and non-patent statutory exclusivities (also known as “regulatory exclusivities”) for each product. While patents are granted by the USPTO, regulatory exclusivities accrue based on FDA actions. Drugs with designations for rare diseases under the Orphan Drug Act, for example, receive 7 years of exclusivity at approval, while certain drugs receive 6 months of added exclusivity based on additional testing in pediatric populations.17 Periods of protection from patents and exclusivities overlap, and both can block the FDA from approving generic versions of brand-name products.18

Because manufacturers’ new patents and regulatory exclusivities can emerge over time, we extracted data on patent and regulatory exclusivity listings in every annual edition of the Orange Book from the year following the drug’s approval until 2022. We determined the dates of expiration for each patent and regulatory exclusivity; if the expiration date initially listed changed in a later version of the Orange Book,19 we used the most recent date.

For all patents, we used Google Patents to obtain the title, claims, priority date, application date, and publication date. Closely related patents are grouped into families, and the priority date refers to the date when the first member of a given family is filed.20 We examined the independent claims of each patent to determine whether the patent was obtained on the delivery device or another aspect of the product such as the active ingredient or method of use.

As in previous studies, we classified patents into those filed before FDA approval (pre-approval patents) and after (post-approval patents), and we classified regulatory exclusivities into those granted at FDA approval (approval exclusivities) and after (post-approval exclusivities).10 We further classified post-approval patents into those with priority dates after approval and those with priority dates before approval; patents with priority dates after approval are of particular interest because of their potential to extend market exclusivity since patent terms are generally tied to priority dates.

We searched for approved generic competitors in the Orange Book to determine if the expected duration of protection for brand-name products had been cut short by early generic competition, and we used the FDA’s Paragraph IV Certifications List (updated through the end of 2022) to identify patent challenges on brand-name products in the cohort.21 Paragraph IV certifications are challenges to existing FDA-listed brand-name patents that are brought by generic manufacturers seeking approval of products before these patents expire. Brand-name firms may sue for patent infringement, which can block the FDA from approving the generic drug for 30 months or until litigation is resolved (whichever occurs first). To examine any litigation that resulted from paragraph IV challenges, we used the LexisNexis LexMachina database, which gives information on patent lawsuits found in the Public Access to Court Electronic Records database filed since January 1, 2000.22

Outcomes

Our primary outcome was the duration of expected protection from generic competition. We defined expected protection for a given product as the time elapsed from FDA approval until expiration of the last-to-expire patent or regulatory exclusivity. Patents and regulatory exclusivities removed from the Orange Book before expiration were excluded from this analysis. As a secondary analysis, we also calculated length of protection from patents and statutory exclusivities at the time of approval versus from exclusivities secured after FDA approval.

Results

Our final cohort included 10 brand name products containing GLP-1 receptor agonists from 2005-2021 (Figure 1; Table 1). Two were approved for obesity while 8 were approved for Type 2 diabetes. The 10 products included 21 different formulations, of which 18 (86%) were drug-device combinations and 3 (14%) were oral tablets.

Figure 1:

GLP-1 receptor agonists included in the cohort

Table 1:

FDA-approved GLP-1 receptor agonists, 2005-2021a

| Product | Version | FDA approval date | Active ingredient | Indicationb | Manufacturer | First patent filing listed with the FDA | Time from first patent filing to initial FDA approval (years) | First paragraph IV certificationc | Time from initial FDA approval to first paragraph IV certification (years) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Byetta | Byetta (300mcg/1.2mL) | 4/28/2005 | exenatide | Glycemic control in Type 2 diabetes | AstraZeneca | 5/24/1993 | 11.9 | 6/11/2014 | 9.1 |

| Byetta (600mcg/2.4mL) | 4/28/2005 | ||||||||

| Victoza | Victoza (6mg/mL) | 1/25/2010 | liraglutide | Glycemic control in Type 2 diabetes; reduced risk of major adverse cardiovascular events in Type 2 diabetes and established cardiovascular disease | Novo Nordisk | 1/28/1999 | 11.0 | 12/12/2016 | 6.9 |

| Bydureon | Bydureon (2mg/vial) | 1/27/2012 | exenatide | Glycemic control in Type 2 diabetes | AstraZeneca | 5/24/1993 | 18.7 | NA | NA |

| Bydureon Pen (2mg/vial) | 2/28/2014 | ||||||||

| Bydureon BCise (2mg/0.85mL) | 10/20/2017 | ||||||||

| Saxenda | Saxenda (6mg/mL) | 12/23/2014 | liraglutide | Weight management in obesity | Novo Nordisk | 2/26/1999 | 15.8 | 8/16/2021 | 6.6 |

| Adlyxin | Adlyxin (0.05mg/mL) | 7/27/2016 | lixisenatide | Glycemic control in Type 2 diabetes | Sanofi | 12/2/2008 | 7.7 | NA | NA |

| Adlyxin (0.1mg/mL) | 7/27/2016 | ||||||||

| Xultophy | Xultophy (3.6mg/mL) | 11/21/2016 | insulin degludec/liraglutide | Glycemic control in Type 2 diabetes | Novo Nordisk | 11/21/2016 | 17.7 | NA | NA |

| Soliqua | Soliqua (33mcg/mL) | 11/21/2016 | insulin glargine/lixisenatide | Glycemic control in Type 2 diabetes | Sanofi | 11/21/2016 | 10.4 | NA | NA |

| Ozempic | Ozempic (2mg/1.5mL) | 5/12/2017 | semaglutide | Glycemic control in Type 2 diabetes; reduced risk of major adverse cardiovascular events in Type 2 diabetes and established cardiovascular disease | Novo Nordisk | 1/2/2002 | 15.9 | 12/6/2021 | 4.0 |

| Ozempic (2mg/1.5mL) | 12/5/2017 | ||||||||

| Rybelsus | Rybelsus (3mg) | 9/20/2019 | semaglutide | Glycemic control in Type 2 diabetes | Novo Nordisk | 3/20/2006 | 13.5 | NA | NA |

| Rybelsus (7mg) | 9/20/2019 | ||||||||

| Rybelsus (14mg) | 9/20/2019 | ||||||||

| Wegovy | Wegovy (0.25mg/0.5mL) | 6/4/2021 | semaglutide | Weight management in obesity | Novo Nordisk | 3/20/2006 | 15.2 | NA | NA |

| Wegovy (0.5mg/0.5mL) | 6/4/2021 | ||||||||

| Wegovy (1mg/0.5mL) | 6/4/2021 | ||||||||

| Wegovy (1.7mg/0.75mL) | 6/4/2021 | ||||||||

| Wegovy (2.4mg/0.75mL) | 6/4/2021 |

FDA: Food and Drug Administration; T2DM: Type 2 diabetes mellitus; MACE: Major adverse cardiovascular events

Two brand drugs, dulaglutide and albiglutide, are not included in this table nor in the analysis because they were regulated as biologics at the time of approval.

All indications included on FDA labels through the end of 2022 are listed here.

Firms seeking approval for generic versions of brand-name drugs must file paragraph IV certifications in cases when the brand-name reference drug has active patents listed in the Orange Book. When filing a paragraph IV certifications, generic firms must attest that all patents listed in the Orange Book on the brand-name reference drug are invalid, unenforceable, or not infringed by the generic product.

Exclusivities at Approval

Drug manufacturers listed 164 patents across the 10 products that were filed before FDA approval with a median of 17 patents per product (interquartile range [IQR]: 8.3-22.8). Among these patents, the median time from first patent filing to approval was 14.4 years (IQR: 11.2-15.9). Exenatide (Bydureon) had the most preapproval patents at 31, followed by insulin glargine/lixisenatide (Soliqua) at 26, and insulin degludec/liraglutide (Xultophy) at 23. Patents on devices accounted for 90 (55%) pre-approval patents. The last-to-expire patent filed before FDA approval was a device patent for 4 of the 10 products in the cohort.

Fourteen regulatory exclusivities covered the 10 products at approval (median 1 [IQR: 1-2]). Nine (64%) were 5-year exclusivities awarded for approval of new chemical entities, while the other 5 (36%) were 3-year exclusivities awarded for approval of new investigations or combinations.

The median duration of expected protection for these drugs at the time of approval was 17.4 years (IQR: 15.3-18.7).

Post-approval Exclusivities

Drug manufacturers listed 22 patents after FDA approval of the 10 products in the cohort (median 1.5 [IQR: 0–2.8]), including 11 patents on devices (50%). Exenatide had the most (Bydureon, 8), followed by liraglutide (Saxenda, 6). Twenty had priority dates before FDA approval, while 2 had priority dates after FDA approval. The median number of patents obtained per product, when including both pre- and post-approval patents, was 19.5 (IQR: 9.0-25.8). Post-approval patents only extended the duration of protection on 2 products (median 4.6 years, IQR: 4.5-4.8).

Manufacturers obtained pediatric exclusivities on 2 products after approval, which added 6 months to the existing patent expiration dates. Manufacturers also obtained 19 non-pediatric regulatory exclusivities FDA approval (median 1 [IQR: 0.3-4.3]). Only one of these exclusivities extended the duration of expected protection beyond existing patents (Byetta, 4.8 years).

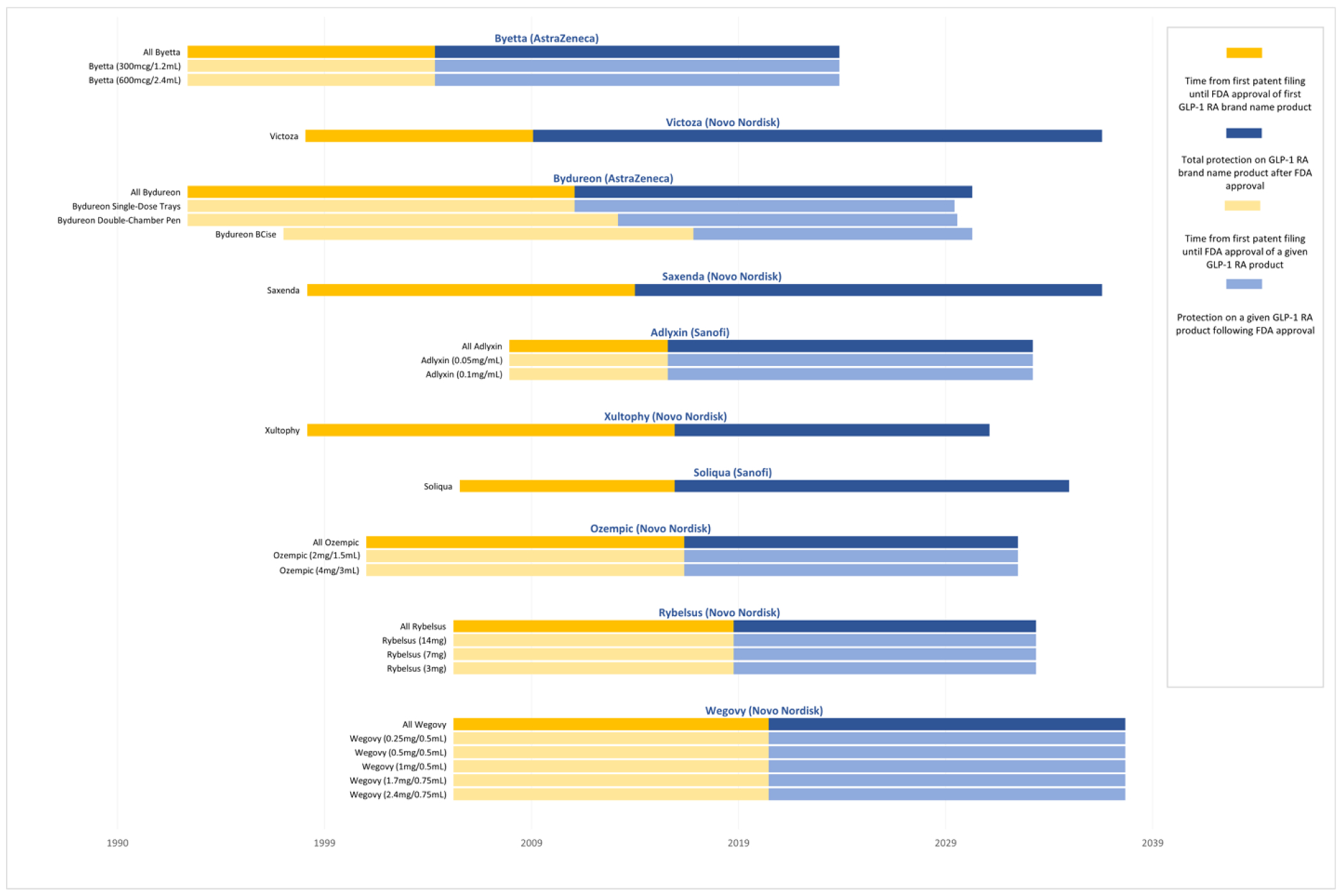

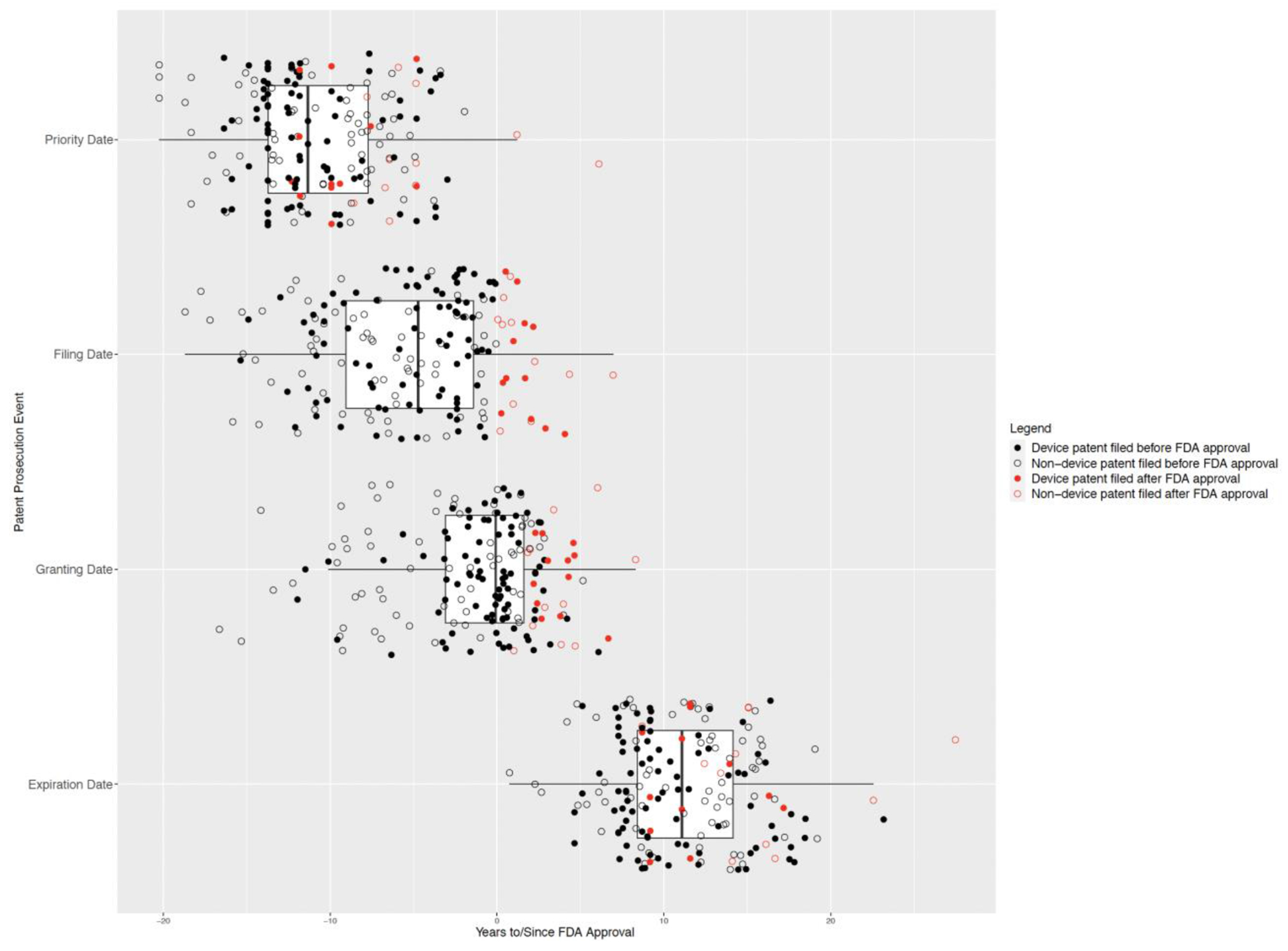

The median total duration of protection from FDA approval, when accounting for both pre- and post-approval patents and regulatory exclusivities, was 18.3 years (IQR: 16.0-19.4) (Figure 2). The median time elapsed from the earliest patent filing date within a given product to the expiration date of the last-to-expire patent or exclusivity on that product was 31.9 years (IQR: 29.9-36.6). The last-to-expire patent was a device patent for 2 of the 10 products. Figure 3 maps the key legal events for all patents on GLP-1 receptor agonists from filing to expiration.

Figure 2: Protection from patents and regulatory exclusivities on GLP-1 receptor agonists, 1993-2038.

This figure shows the expected duration of protection from generic competition on each GLP-1 receptor agonist from the time of first patent filing until the expiration of the last patent or regulatory exclusivity. The dark blue bars (uppermost for each product) represent protection for the product as a whole, while the light blue bars represent protection for each of the product’s individual strengths and/or formulations. Products are listed in ascending order based on the initial Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval date for a given product. Manufacturers may add new patents in subsequent years, which could expire later than patents depicted in the figure. The median total duration of protection from FDA approval among GLP-1 receptor agonists is 18.3 years (IQR: 16.0-19.4). The median time elapsed from the earliest patent filing date within a given product to the expiration date of the last-to-expire patent or exclusivity on that product is 31.9 years (IQR: 29.9-36.6).

Figure 3: Key legal events in the patent lifecycles of GLP-1 receptor agonists.

This figure shows the distribution of key legal events associated with the patent life cycle (priority date, filing date, granting date, and expiration date) for each patent in the cohort relative to the corresponding product’s approval date. Boxes represent the interquartile range (IQR) with vertical lines in each box depicting the median, and whiskers extend in either direction from the first and third quartiles by up to 1.5-times the IQR. There were 186 total patents listed on the 10 products in the cohort, and each of the 4 plots depicts the relevant legal event for all patents in the cohort. Of note, this figure excludes patents (n=7) that were removed from the Orange Book prior to expiration since these patents do not contribute to expected periods of patent protection (primary endpoint).

Patent Challenges from Generic Competitors

No independent generic GLP-1 receptor agonists entered the market during the study period. However, generic manufacturers for 4 of the 10 products submitted paragraph IV challenges seeking FDA approval prior to brand-name patent expiration. Among the 4 brand-name products with paragraph IV submissions, the median time from brand-name approval to first paragraph IV challenge was 6.8 years (IQR: 6.0-7.4). Generic firms challenged 8 active patents on Byetta (all non-device patents), 9 on Victoza (4 device and 5 non-device patents), 22 on Saxenda (18 device and 4 non-device patents), and 23 on Ozempic (19 device and 4 non-device patents) (eTable 1). Overall, 66% (41/62) of patents listed at the time of first paragraph IV certification on these four GLP-1 receptor agonists were device patents.

After paragraph IV challenges, manufacturers added a total of 4 patents to the Orange Book (3 device and 1 non-device patents). The manufacturer of Victoza added 3 patents after paragraph IV certification, while the manufacturer of Saxenda added 1 patent (eTable 2).

No paragraph IV certification has resulted in an approved generic; the 24 lawsuits brought by brand-name firms against generic competitors are either ongoing (n=14), were settled (n=5), were terminated for procedural reasons (n=2), or were decided in favor of the brand-name firm (n=3).

Discussion

The FDA approved the first GLP-1 receptor agonist almost two decades ago, and yet there remains no generic competitors in the therapeutic class. Brand-name firms have obtained numerous patents and exclusivities leading to a median of more than 18 years of expected protection following FDA approval. While the last-to-expire patent was a device patent in just one-fifth of cases, more than half of all patents listed with the FDA covering GLP-1 receptor agonists were on the delivery devices rather than active ingredients, methods of use, or formulations, which can make it difficult for generic firms to obtain FDA approval for their products. Numerous generic firms have attempted to challenge patents on these products via paragraph IV certifications, but none has yet resulted in generic entry.

Our findings add to a growing body of literature highlighting how manufacturers of drug-device combinations have used the patent system to extend periods of market exclusivity on their products. Strategies include obtaining large numbers of different patents on the same product, obtaining new patents on products even after FDA approval, and settling patent litigation brought by potential generic competitors. While such patent strategies have been well-documented in the markets for inhalers10–12 and insulin pens,13 our study shows that these practices are also common among GLP-1 receptor agonists.23 Market exclusivity for top-selling brand-name drugs has a median of about 12-14 years,24 but longer periods have been observed for inhalers (median of 16 years)10–12 and insulin products (median of 17 years).13 The median expected protection we determined for GLP-1 receptor agonists—which exceeds 18 years—is the highest yet reported for drug-device combinations. With GLP-1 receptor agonists netting manufacturers more than $10 billion per year in the US alone and with sales expected to rise in the coming decade,6 every additional year of brand-name market exclusivity may be associated with hundreds of millions of dollars in manufacturer revenue.

The system for challenging patents created by the Hatch-Waxman Act does not appear to function well for drug-device combinations. In the case of inhalers, a recent study found that only 13% of brand-name products in that class approved over the past 35 years faced any paragraph IV certifications, and the median time from brand-name approval to first paragraph IV certification was 14.5 years.12 By contrast, among oral small-molecule drugs, the median time from brand-name approval to first paragraph IV certification is 5.2 years.25 One hypothesis for this difference is that device patents on drug-device combinations deter generic manufacturers from seeking approval; another related possibility is that proving bioequivalence for drug-device combinations to earn FDA approval may be challenging as compared to oral formulations and thus attracts fewer potential competitors.

The large number of paragraph IV certifications on GLP-1 receptor agonists and the short median duration of time from brand-name approval to first paragraph IV certification (6.8 years) suggests that the barriers to generic GLP-1 receptor agonist entry may differ in important ways from the barriers for other drug-device combinations such as inhalers. In particular, proving bioequivalence on these products may be easier given their systemic mechanism of action (in contrast to inhalers, which act locally) and the ability for generic firms to apply simpler in vivo techniques when seeking FDA approval. The rapidly expanding market for GLP-1 receptor agonists may also be enticing more generic firms to take on risk when challenging patents. Whether the Hatch-Waxman system succeeds in promoting timely generic competition for GLP-1 receptor agonists remains to be seen.

Currently, GLP-1 receptor agonists costs hundreds of dollars per month.4 Robust generic competition for these products will be crucial for lowering prices in the coming years. Such competition will be particularly important as the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) begins to negotiate Medicare prices under the Inflation Reduction Act. While brand-name drugs with generic competition will be excluded from price negotiation, generic competition within a given class may enhance the government’s leverage in negotiation for all drugs in the class. This is because CMS plans to negotiate based on the net prices of therapeutic alternatives.26 Thus, if one low-price generic version of a GLP-1 receptor agonist becomes available in the US, this may help achieve lower prices for all GLP-1 receptor agonists that CMS selects for negotiation.

GLP-1 receptor agonists are likely to assume a growing role to treat obesity. Once weekly semaglutide, for example, has been associated with a 12.4% decrease in weight compared to placebo among patients with a body mass index greater than or equal to 30, representing a sizeable advance over alternative anti-obesity therapies.27 Medicare does not currently cover anti-obesity treatment but, if policy initiatives to reverse this pass, the annual costs of GLP-1 receptor agonists for Medicare Part D are projected to range from $13 billion to $27 billion at current prices (and represent nearly 20% of the Part D budget).28 A crucial tool to lower costs is swift generic competition, and addressing the patent and exclusivity landscape for drug-device combinations such as GLP-1 receptor agonists is key for facilitating such competition.

The Government Accountability Office (GAO) released a report in 2023 examining how the patent and regulatory system for drug-device combinations may be delaying generic competition.29 Though many stakeholders interviewed for the GAO report felt that listing device patents in the Orange Book may expedite generic entry by increasing transparency, nearly all felt that the FDA should clarify the types of device patents that brand-name manufacturers should be allowed to list. Currently, the FDA does not assess whether submitted patents are suitable for listing. Allowing manufacturers to list device patents in the Orange Book can delay generic competition by giving brand-name firms an opportunity to file litigation and earn 30-month stays even when patents are not infringed by the generic product. A helpful step forward would be to either de-list device patents in the Orange Book or require listing (thereby providing generic firms with transparency), but end the practice of awarding 30-month stays when such patents are litigated.30

The FDA, more generally, should take a more active role in working with the USPTO to ensure that patents submitted for listing in the Orange Book have been validly granted and are not overly broad. An important limitation of our study is that we did not review the validity of the patents covering our cohort of drugs. However, other research has highlighted that inappropriately granted patents are common in the pharmaceutical sector.32 Such upstream action at the USPTO, when coupled with Orange Book reform, could further reduce the need for costly patent challenges by generic firms.

Another helpful solution would be for Congress to grant the FDA more flexibility in approving generic drug-device combinations. The FDA requires that generic firms develop drug-device combinations that patients can use in just the same way as brand-name versions based on an identical label. In President Biden’s proposed 2024 budget, the FDA has called on Congress to grant further authority to allow for labelling changes on generic drug-device combinations.31 This would enable generic manufacturers to develop drug-device combinations that differ from brand-name versions—and more easily avoid infringing their patents—but that are nevertheless clinically interchangeable.

Our study is also limited in that it may underestimate the duration of market exclusivity on GLP-1 receptor agonists because manufacturers can add patents on their products over time. By contrast, the study could overestimate periods of expected market exclusivity since outcomes from some of the litigation currently underway over paragraph IV certifications may yield generic competition prior to the expiration of FDA-listed patents. While our study cannot predict such future shifts, it provides a comprehensive picture of how FDA-listed patents and regulatory exclusivities on GLP-1 agonists currently serve to delay or block generic competition.

Conclusions

Manufacturers of brand-name GLP-1 receptor agonists have obtained periods of market exclusivity on their products through extensive patents and regulatory exclusivities that are positioned to be longer than other classes of drug-device combinations and especially small-molecule oral medications. Lawmakers and regulators should work to develop solutions that facilitate timely entry of generic drug-device combinations for GLP-1 receptor agonists so that manufacturers can earn reasonable returns for limited periods of time, while more patients eventually benefit from lower costs and improved access to these useful drugs.

Supplementary Material

Key Points.

Question:

How have manufacturers of brand-name glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists used the patent and regulatory system to extend periods of market exclusivity?

Findings:

Brand-name manufacturers obtained a median of 19.5 patents per GLP-1 receptor agonist and secured a median of 18.2 years of expected protection. More than half of all patents were obtained on the delivery devices rather than active ingredients. No generic competition has yet emerged on these products.

Meaning:

Long periods of market exclusivity on GLP-1 receptor agonists underscore the need for patent and regulatory reform on drug-device combinations.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the Commonwealth Fund. The funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, interpretation, of the data; review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication. Dr. Feldman’s work is also funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (K08HL163246), Dr. Feldman’s and Kesselheim’s work by Arnold Ventures, and Dr. Tu’s work by West Virginia University’s Hodges Research Grant. Outside the scope of the work, Dr. Feldman serves as a consultant for Alosa Health and as an expert witness in litigation against inhaler manufacturers. Dr. Feldman also served as a consultant to Aetion. Dr. Kesselheim reports serving as an expert witness in litigation against Gilead relating to tenofovir-containing products.

References

- 1.El Sayed NA, Aleppo G, Aroda VR, et al. 9. Pharmacologic approaches to glycemic treatment: Standards of Care in diabetes—2023. Diabetes Care. 2023;46(Supplement 1):S140–S157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.The American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee. Obesity and Weight Management for the Prevention and Treatment of Type 2 Diabetes: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes—2022. Diabetes Care. 2021;45(Supplement_1):S113–S124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Food and Drug Administration. Byetta (Exenatide) Injection. April 28, 2005. Available from: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2005/021773_byettatoc.cfm#:~:text=Approval-Date-4-28-2005. Accessed March 17, 2023.

- 4.Sarpatwari A, Tessema FA, Zakarian M, Najafzadeh MN, Kesselheim AS. Diabetes Drugs: List Price Increases Were Not Always Reflected In Net Price; Impact Of Brand Competition Unclear. Health Affairs. 2021;40(5):772–778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Luo J, Feldman R, Rothenberger SD, Hernandez I, Gellad WF. Coverage, Formulary Restrictions, and Out-of-Pocket Costs for Sodium-Glucose Cotransporter 2 Inhibitors and Glucagon-Like Peptide 1 Receptor Agonists in the Medicare Part D Program. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(10):e2020969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.SSR Health. Brand RX Net Pricing Tool. Available from: https://www.ssrhealth.com/brand-rx-net-pricing-tool/. Accessed March 17, 2023.

- 7.Kesselheim AS, Avorn J, Sarpatwari A. The high cost of prescription drugs in the United States: origins and prospects for reform. JAMA. 2016;316(8):858–871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Food and Drug Administration. Frequently asked questions on patents and exclusivity 2020 Feb 5 [cited 2022 Aug 05]. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/development-approval-processdrugs/frequently-asked-questionspatents-and-exclusivity. Accessed March 17, 2023.

- 9.Beall RF, Kesselheim AS. Tertiary patenting on drug-device combination products in the United States. Nat Biotechnol. 2018;36(2):142–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Feldman WB, Bloomfield D, Beall RF, Kesselheim AS. Patents And Regulatory Exclusivities On Inhalers For Asthma And COPD, 1986-2020. Health Aff (Millwood). 2022:41(6):787–796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Feldman WB, Bloomfield D, Beall RF, Kesselheim AS. Brand-name market exclusivity for nebulizer therapy to treat asthma and COPD. Nat Biotechnol. 2022;40(9):1319–1325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reddy S, Beall RF, Tu SS, Kesselheim AS, Feldman WB. Patent Challenges And Litigation On Inhalers For Asthma And COPD. Health Aff (Millwood). Mar 2023;42(3):398–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Van de Wiele VL, Kesselheim AS, Beran D, Darrow JJ. Insulin products and patents in the USA in 2004, 2014, and 2020: a cross-sectional study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2023;11(2):73–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.United States Patent and Trademark Office. USPTO-FDA Collaboration Initiatives. Available from: https://www.uspto.gov/initiatives/fda-collaboration. Accessed March 17, 2023.

- 15.Hyman, Phelps & McNamara. The Orange Book archives. FDA Law Blog [blog on the Internet]. Available from: https://www.thefdalawblog.com/orange-book-archives/. Accessed March 17, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Food and Drug Administration. Drugs@FDA: FDA-approved drugs. Available from: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/daf/index.cfm. Accessed March 17, 2023.

- 17.Congressional Research Service. Drug prices: the role of patents and regulatory exclusivities. February 10, 2021. CRS report R46679. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kesselheim AS, Sinha MS, Avorn J. Determinants of Market Exclusivity for Prescription Drugs in the United States. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(11):1658–1664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beall RF, Darrow JJ, Kesselheim AS. Patent term restoration for top-selling drugs in the United States. Drug Discov Today. 2019;24(1):20–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martinez C Insight into Different Types of Patent Families. OECD Science, Technology, and Industry Working Papers. Available from: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/insight-into-different-types-of-patent-families_5kml97dr6ptl.pdf. Accessed March 17, 2023.

- 21.Food and Drug Administration. Paragraph IV Certifications List. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/media/133240/download. Accessed March 17, 2023.

- 22.Jacobo-Rubio R, Turner JL, Williams JW. The distribution of surplus in the us pharmaceutical industry: Evidence from paragraph iv patent-litigation decisions. The Journal of Law and Economics. 2020;63(2):203–238. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Feldman WB, Tu SS, Alhiary R, Kesselheim AS, Wouters OJ. Manufacturer Revenue on Inhalers After Expiration of Primary Patents, 2000-2021. JAMA. 2023;329(1):87–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rome BN, Lee CC, Kesselheim AS. Market Exclusivity Length for Drugs with New Generic or Biosimilar Competition, 2012-2018. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2021;109(2):367–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kannappan S, Darrow JJ, Kesselheim AS, Beall RF. The timing of 30-month stay expirations and generic entry: A cohort study of first generics, 2013-2020. Clin Transl Sci. 2021;14(5):1917–1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Price Negotiation Program. Available from: https://www.cms.gov/files/document/medicare-drug-price-negotiation-program-initial-guidance.pdf. Accessed March 17, 2023.

- 27.Wilding JPH, Batterham RL, Calanna S, et al. Once-Weekly Semaglutide in Adults with Overweight or Obesity. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(11):989–1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baig K, Dusetzina SB, Kim DD, Leech AA. Medicare Part D Coverage of Antiobesity Medications - Challenges and Uncertainty Ahead. N Engl J Med. 2023;388(11):961–963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Government Accountability Office. Generic Drugs: Stakeholder Views on Improving FDA’s Information on Patents. Available from: https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-23-105477. Accessed March 17, 2023.

- 30.Sinha M Costly Gadgets: Barriers to Market Entry and Price Competition for Generic Drug-Device Combinations in the United States. Minnesota Journal of Law, Science & Technology. 2022;293. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Food and Drug Administration. Summary of FY 2024 Legislative Proposals. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/media/166049/download#:~:text=The-proposals-include-enhanced-authorities,activities-when-inspections-are-not. Accessed March 17, 2023.

- 32.Bloomfield D, Lu Z, Kesselheim AS. Improving the quality of US drug patents through international awareness. BMJ. 2022;377:e068172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.