Abstract

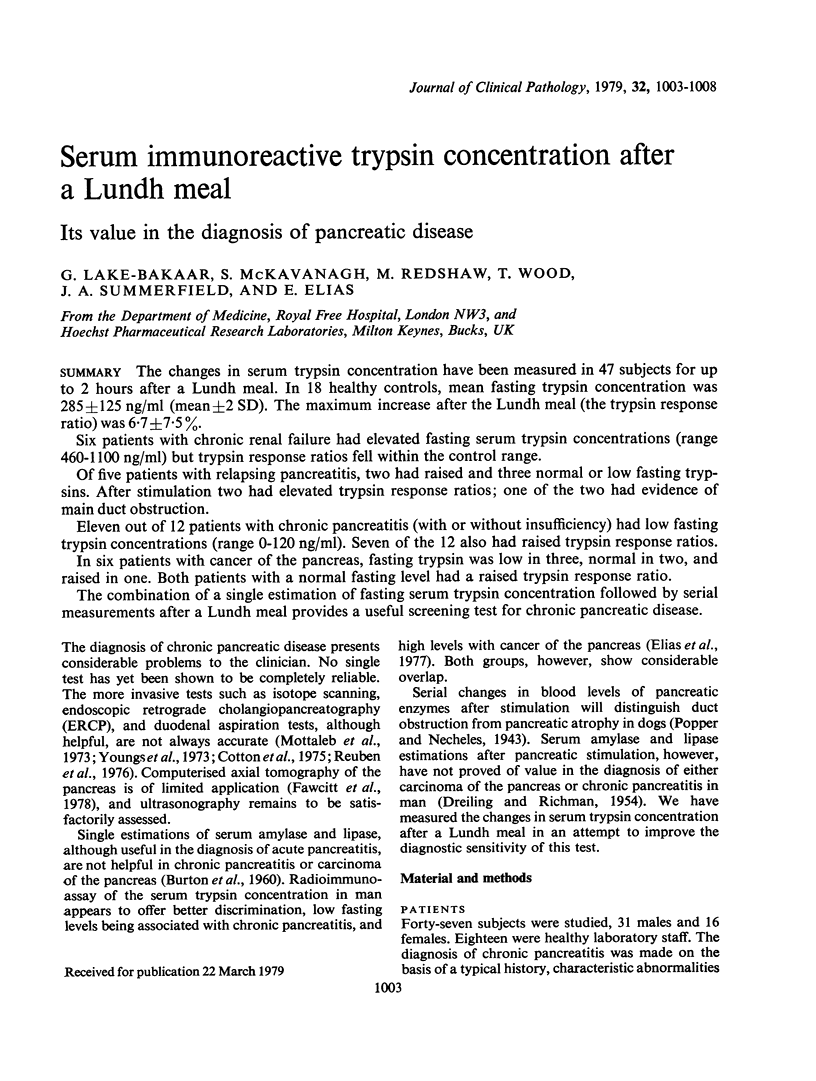

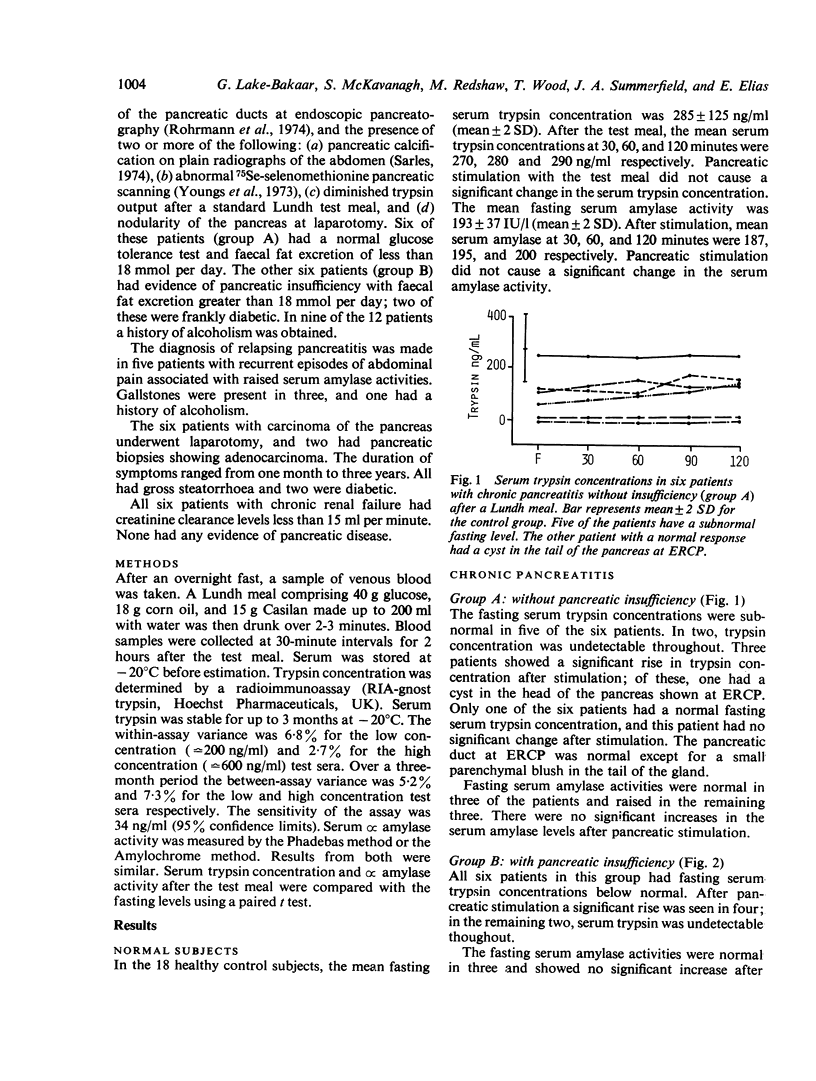

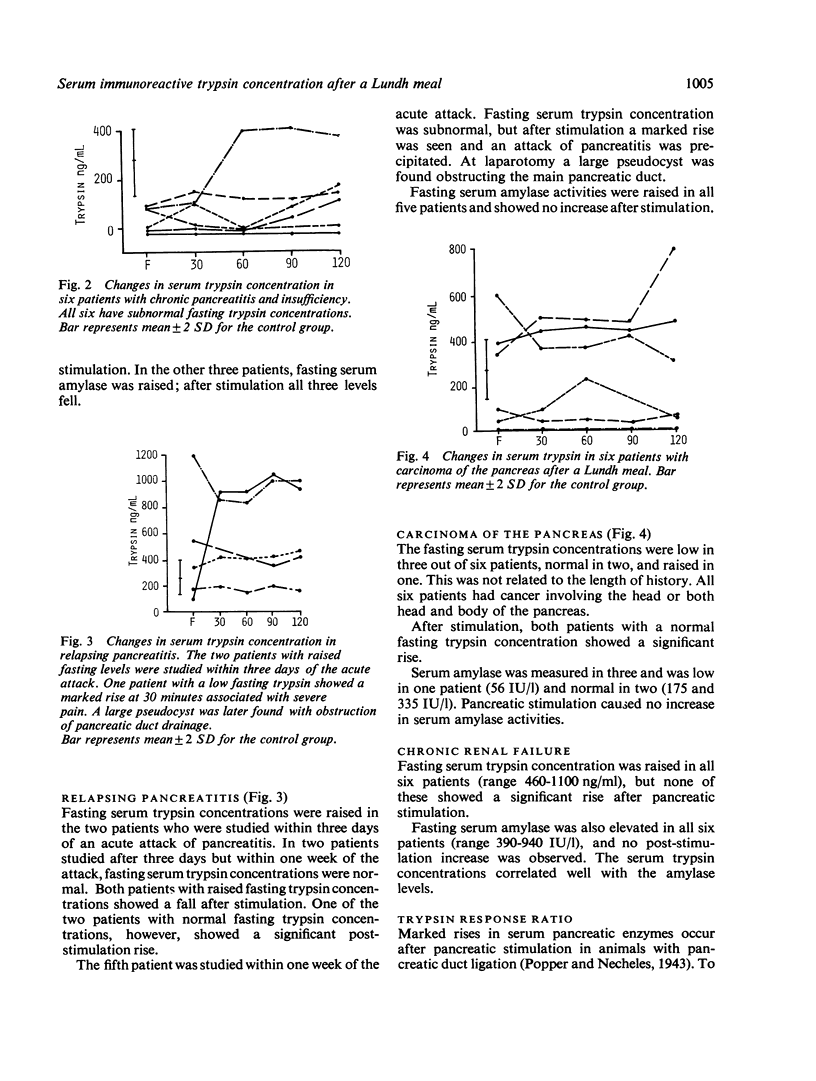

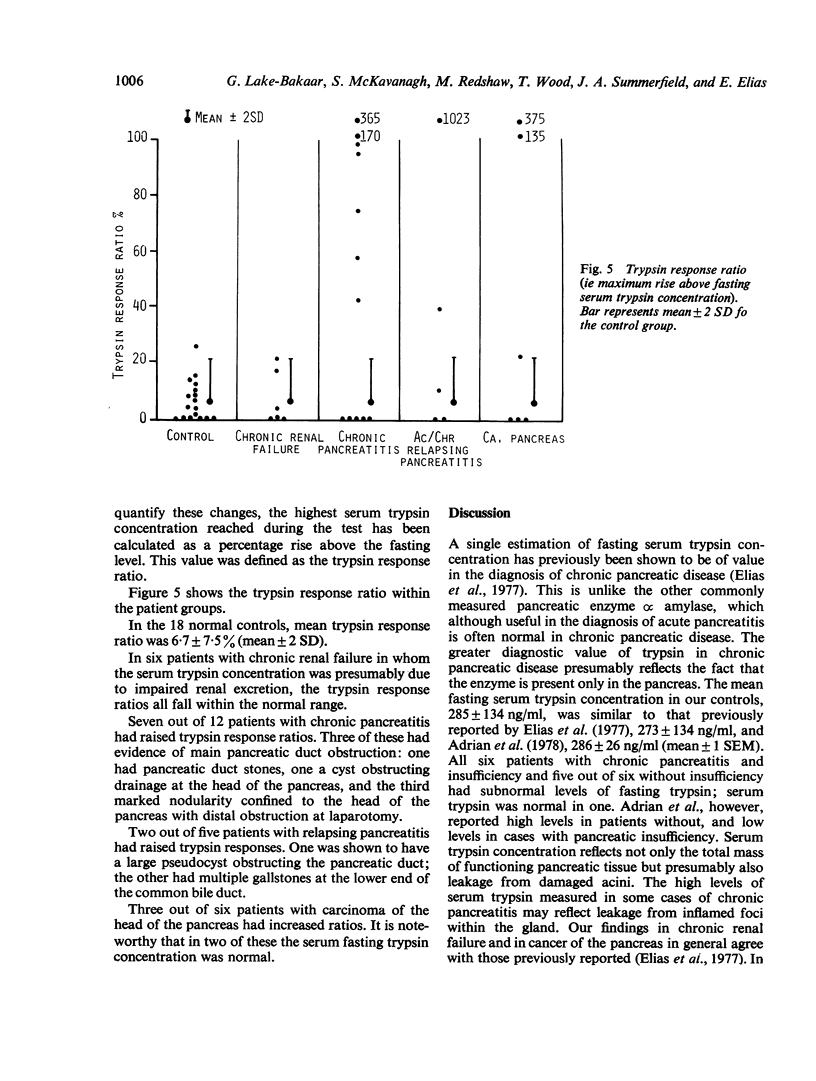

The changes in serum trypsin concentration have been measured in 47 subjects for up to 2 hours after a Lundh meal. In 18 healthy controls, mean fasting trypsin concentration was 285 +/- 125 ng/ml (mean +/- 2 SD). The maximum increase after the Lundh meal (the trypsin response ratio) was 6.7 +/- 7.5%. Six patients with chronic renal failure had elevated fasting serum trypsin concentrations (range 460-1100 ng/ml) but trypsin response ratios fell within the control range. Of five patients with relapsing pancreatitis, two had raised and three normal or low fasting trypsins. After stimulation two had elevated trypsin response ratios; one of the two had evidence of main duct obstruction. Eleven out of 12 patients with chronic pancreatitis (with or without insufficiency) had low fasting trypsin concentrations (range 0-120 ng/ml) Seven of the 12 also had raised trypsin response ratios. In six patients with cancer of the pancreas, fasting trypsin was low in three, normal in two, and raised in one. Both patients with a normal fasting level had a raised trypsin response ratio. The combination of a single estimation of fasting serum trypsin concentration followed by serial measurements after a Lundh meal provides a useful screening test for chronic pancreatic disease.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- BURTON P., HAMMOND E. M., HARPER A. A., HOWAT H. T., SCOTT J. E., VARLEY H. Serum amylase and serum lipase levels in man after administration of secretin and pancreozymin. Gut. 1960 Jun;1:125–139. doi: 10.1136/gut.1.2.125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotton P. B., Ponder B. A., Beales J. S., Croft D. N. Proceedings: Pancreatic diagnosis: Comparison of endoscopic pancreatography (ERCP), isotope scanning, and secretin tests in 62 patients. Gut. 1975 May;16(5):405–405. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DREILING D. A., RICHMAN A. Evaluation of provocative blood enzyme tests employed in diagnosis of pancreatic disease. AMA Arch Intern Med. 1954 Aug;94(2):197–212. doi: 10.1001/archinte.1954.00250020031002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elias E., Redshaw M., Wood T. Diagnostic importance of changes in circulating concentrations of immunoreactive trypsin. Lancet. 1977 Jul 9;2(8028):66–68. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(77)90066-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fawcitt R. A., Forbes W. S., Isherwood I., Braganza J. M., Howat H. T. Computed tomography in pancreatic disease. Br J Radiol. 1978 Jan;51(601):1–4. doi: 10.1259/0007-1285-51-601-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mottaleb A., Kapp F., Noguera E. C., Kellock T. D., Wiggins H. S., Waller S. L. The Lundh test in the diagnosis of pancreatic disease: a review of five years' experience. Gut. 1973 Nov;14(11):835–841. doi: 10.1136/gut.14.11.835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohrmann C. A., Silvis S. E., Vennes J. A. Evaluation of the endoscopic pancreatogram. Radiology. 1974 Nov;113(2):297–304. doi: 10.1148/113.2.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarles H. Chronic calcifying pancreatitis--chronic alcoholic pancreatitis. Gastroenterology. 1974 Apr;66(4):604–616. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Youngs G. R., Agnew J. E., Levin G. E., Bouchier I. A. A comparative study of four tests of pancreatic function in the diagnosis of pancreatic disease. Q J Med. 1973 Jul;42(167):597–618. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]