Abstract

Recovery Colleges (RCs) are learning-based mental health recovery communities, located globally. However, evidence on RC effectiveness outside Western, educated, industrialised, rich, and democratic (WEIRD) countries is limited. This study aimed to evaluate associations between cultural characteristics and RC fidelity, to understand how culture impacts RC operation. Service managers from 169 RCs spanning 28 WEIRD and non-WEIRD countries assessed the fidelity using the RECOLLECT Fidelity Measure, developed based upon key RC operation components. Hofstede’s cultural dimension scores were entered as predictors in linear mixed-effects regression models, controlling for GDP spent on healthcare and Gini coefficient. Higher Individualism and Indulgence, and lower Uncertainty Avoidance were associated with higher fidelity, while Long-Term Orientation was a borderline negative predictor. RC operations were predominantly aligned with WEIRD cultures, highlighting the need to incorporate non-WEIRD cultural perspectives to enhance RCs’ global impact. Findings can inform the refinement and evaluation of mental health recovery interventions worldwide.

Subject terms: Quality of life, Psychology

Introduction

Recovery Colleges (RCs) are a relatively new learning-based mental health recovery support system offering information, social support and skill development for people with mental health symptoms, carers and staff. RCs were informed by the development of education centre and peer-run services for mental health recovery in the USA during the 1990s1. The first RC opened in England in 2009, and the approach has spread globally. Today RCs are in operation in 28 countries in Europe, Asia, Africa, North America and Oceania across different economic levels and cultural characteristics2. The service settings have also diversified, including primary and secondary care, non-governmental organisations, and education providers3. Key philosophies of RCs are co-production and adult education. Co-production means the involvement of lived experience and professional expertise in planning, designing, delivery, and quality assurance of the mental health courses for people with mental health symptoms, carers and staff4. Adult education is self-directed learning. Adults with a history of mental health symptoms engage with learning that is characterised as collaborative, strengths-based, person-centred, inclusive and community-focused5,6. These two key philosophies contribute to personal recovery, which is defined as living a purposeful and autonomous life despite the presence of mental health symptoms1. The co-production philosophy of RCs is underpinned by two conceptual shifts related to personal recovery from mental health symptoms: (a) the focus of care is on the person, rather than the symptoms, and (b) empowerment and quality of life are as important as symptom reduction7. Recovery is supported through social inclusion of the RC students, empowering them to have or increase social and/or economic roles. Current and former mental health service users, along with other stakeholders such as informal carers and clinical staff working at diverse settings, can enrol as students in a RC7. RCs provide educational and skill development courses for RC students to manage their own wellbeing, such as recovery planning, and mindfulness8. The courses are intended to support students to understand recovery, rebuild their life (e.g., improving sleep), develop life skills (e.g., moving towards life goals) and get more involved in a RC (e.g., qualification to be a peer trainer)9.

In order to understand how RCs work, a change model of RCs for service user students was developed from a systematised review (44 publications) and 33 stakeholder interviews5. Three steps were followed in this study. First, an initial change model was created based on 10 key publications inductively and collaboratively analysed by academic researchers and people with lived experience of mental health symptoms. Second, the initial model was refined through deductive analysis of 34 further publications. Third, the refined model was further refined through stakeholder interviews (n = 33). The interviewees included RC students who have also used secondary care mental health services, peer trainers, clinician trainers, RC managers. The finalised change model comprises mechanisms of action (how RCs work), and outcomes (impact of RCs). Four mechanisms of action were identified: (1) offering an empowering environment, (2) enabling different relationships, (3) facilitating personal growth, and (4) shifting the balance of power through co-production, reducing power differentials. Two categories of outcomes were identified: changes (1) in the student (e.g., self-confidence, self-management) and (2) in their life (e.g., having interests, social engagement).

The evidence base for the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of RCs is still preliminary. Evidence syntheses including reviews about RCs report a lack of research published, and highlight methodological weaknesses5,6,10,11. However, the preliminary evidence is positive. A 2020 review appraising the impact of RCs reported student and staff benefits and initial cost-effectiveness6. RC student benefits include confidence, self-esteem, hope, healthier lifestyle, quality of life, and reduced stigma5,6. RC staff acquire skills and knowledge, leading to (a) changes in their attitudes towards co-production and service users, and (b) increased work motivation10. Regarding cost-effectiveness, an uncontrolled study comparing RC students who completed at least one course versus those who did not, identified that attending an RC was associated with fewer bed days, unintended hospitalisations, and community contacts over 18 months12. Similar results were reported from a service evaluation in the UK13. A cost-benefit analysis in Australia showed reduced emergency and inpatient service use with net savings of A$269 per student14. A 2022 thematic synthesis of qualitative evidence identified the positive RC impact on empowerment and inclusivity. However, methodological weaknesses such as sample selection biases were noted11.

One reason for under-developed RC evidence is unstandardised operation4. To address this problem, RC components were identified, and a fidelity measure was developed4. Fidelity refers to how much an intervention is carried out as planned15. Fidelity is especially important to multi-site interventions15, therefore is relevant to RC operation16. Fidelity components were identified through a multi-stage process: an initial list was developed through a systematised review (13 publications), followed by international expert consultation (n = 77) and interviews with RC managers in England (n = 10)4, and finally the list was refined through interviews with RC students, trainers and managers in England (n = 44). Those 12 identified fidelity components were categorised into seven nonmodifiable components (Valuing equality; Learning; Tailored to the student; Co-production; Social connectedness; Community focus; and Commitment to recovery) and five modifiable components (Available to all; Location; Distinctiveness of course content; Strengths-based; and Progressive)4. The resulting Recovery Colleges Characterisation and Testing (RECOLLECT) Fidelity Measure is a 12-item college manager-rated measure, with each item corresponding to one component. High fidelity indicates that the assessed RC is operated corresponding to what was regarded important in RC operation.

A knowledge gap exists in how culture impacts RC operation. One reason for this is that most RC research has been conducted in Western, educated, industrialised, rich and democratic (WEIRD) countries, lacking evidence from other countries16,17. To date, there have been six reviews about RCs published, and all included studies (n = 185), apart from one international study18, were from WEIRD countries: UK, Ireland, Australia, Canada, Italy, and USA (Supplementary Information 1)4–6,10,19,20. WEIRD countries account for only 12% of the world population, yet the majority of research samples (e.g., 96% of psychological samples) come from these countries. WEIRD countries share relatively similar cultural values such as individualistic, democratic, and greater freedom to satisfy the natural human needs to enjoy life21. The international study18 involved Hong Kong, Israel, Japan, Singapore, Sri Lanka and Singapore, but the findings were reported as an aggregate from the 22 participating counties (the remaining 16 countries were WEIRD countries). More recently, an England-Japan comparison of RC implementation was conducted22, highlighting a need for more cross-cultural studies in RC23. Taken together, very little RC evidence from non-WEIRD countries has been reported. Cross-cultural understanding of RCs can help reduce this knowledge gap.

Cultural adaptation is needed for RCs operating in non-WEIRD cultures, because most RC research has been conducted in WEIRD countries that share similar cultural values, which are often different from those in non-WEIRD countries21. Cultural adaptation is “the systematic modification of an evidence-based treatment…to consider language, culture, and context in such a way that it is compatible with the client’s cultural patterns, meaning, and values”24. The need for cultural adaptation in mental health treatment has been increasingly recognised25 due to factors such as migration, telecommunications and social media26. This applies not only at the global level but also at the national level, where evidence for people in cultural minorities remains to be identified27. Mental health cannot be fully understood without considering culture28, as all human experiences, including mental health, are shaped by cultural particulars26. A meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials identified that culturally-adapted treatment yielded greater mental health improvement than non-adapted active treatment29. Another meta-analysis reported that culturally-adapted treatment was nearly five times more likely to produce remission from mental health symptoms than non-culturally-adapted treatment30. The effect sizes of culturally-adapted treatment are moderate to large for people in non-WEIRD countries25. Cultural adaptation has been investigated for various mental health approaches, including cognitive behavioural therapy, and metacognitive therapy25. The extent to which cultural adaptation of RCs is needed when operated in non-WEIRD cultures is unknown.

To identify how RCs should be culturally adapted to non-WEIRD cultures, cultural characteristics related to RCs need to be identified. Hofstede’s cultural dimension theory21 is the most established quantitative framework in cross-cultural research31, defining culture as “the collective programming of the mind that distinguishes the members of one group or category of people from others”32. The cultural dimension theory proposes six cultural characteristics: Power Distance, Individualism, Success-Drivenness, Uncertainty Avoidance, Long-Term Orientation, and Indulgence. The meaning of each cultural characteristic is described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Six cultural characteristics in the cultural dimension theory

| Characteristic (Interpretation) | Meaning |

|---|---|

| Power Distance (high vs low) | A degree to which inequality and unequal distributions of power between parties are accepted. |

| Individualism (vs Collectivism) | A degree to which a society excepts individuals to be loosely tied to one another, and to take care of only themselves and their immediate family. |

| Success-Drivenness (vs Quality-Orientation) | A societal value for achievement, and material rewards for success (originally named ‘Masculinity’). |

| Uncertainty Avoidance (high vs low) | A degree to which individuals feel threatened by unknown situations, and try to avoid such situations. |

| Long-Term Orientation (vs Short-Term Orientation) | Values oriented towards future rewards, perseverance, and thrift, which are related to ‘saving’ as opposed to ‘spending’. |

| Indulgence (vs Self-Restrained) | Acceptance of relatively free gratification of basic and natural human needs to enjoy life. |

These cultural characteristics have high relevance to RC operation. For example, one of the key RC philosophies, co-production may be relevant to Power Distance (e.g., between healthcare workers and service users) and Individualism, as inferred in our international RC study2. Co-production requires each individual to express their needs, which may have relevance to Power Distance, Individualism, Success-Drivenness, and Indulgence. These needs are individual, and may be challenging to articulate, which may be impacted by Uncertainty Avoidance. Finally, the RC focus on the person, instead of the symptom, may require Long-Term Orientation. However, these relationships have not been empirically evaluated.

Moreover, cross-cultural debates in RC research thus far have tended to be limited to broader categories (e.g., Asian collectivism vs Western individualism2). Among the same cultural characteristics, how much one characteristic is valued differs across cultures. For example, Thailand and Japan are both labelled as valuing collectivism in the West, but Japan is known to have more individualistic values than other Asian countries33,34. Empirical evaluation of the RC-culture relationships needs to consider these differences.

Our previous global survey2 identified preliminary evidence that cultural characteristics may influence fidelity ratings. Fidelity scores in RCs in Western countries were higher than those in non-Western countries. We speculated that one reason for the fidelity score gap might be cultural differences; however, an empirical evaluation remained to be performed. The current study extends this work in four ways: the first empirical evaluation, use of an established theoretical framework (Hofstede), inclusion of cultural covariates (% of GDP spent on healthcare and GINI coefficient of social inequality35,36), and consideration of between-country differences in valorisation of particular cultural characteristics (e.g., collectivism in Thailand versus Japan).

This study aimed to explore the relationships between cultural characteristics and fidelity in all currently-operating RCs internationally. RC inclusion criteria were targeting to support personal recovery, and prioritising co-production and adult learning.

Our research questions were;

Are there associations between cultural characteristics and the operational indicators of RC fidelity?, and

If there are, which cultural characteristics are associated with the operational indicators of RC fidelity?”

Addressing these research questions is intended to identify cultural impact on RC fidelity. Because RCs are in operation in many countries, identifying the cultural impact of RC operation will be useful to cross-cultural understanding of RC operation, and by extension, will have relevance to other recovery-oriented global innovations, such as mental health peer support work37. We recruited RCs that were currently in operation from 28 countries across different cultures (Table 2 for the participating WEIRD and non-WEIRD countries), and evaluated whether differences in cultural characteristics could predict variance in their fidelity scores. Mixed-effects linear regression models with a country-level random intercept were used to allow us to identify associations between the cultural characteristics and RC fidelity while accounting for variability between countries. No hypotheses were predefined due to the exploratory and inductive nature of the research38.

Table 2.

Participating WEIRD and non-WEIRD countries (n = 28)

| WEIRD | non-WEIRD |

|---|---|

| Australia | Hong Kong |

| Belgium | Japan |

| Bulgaria | Thailand |

| Canada | Uganda |

| Czechia | |

| Denmark | |

| England | |

| Estonia | |

| Finland | |

| France | |

| Germany | |

| Hungary | |

| Iceland | |

| Ireland | |

| Italy | |

| Jersey | |

| Netherlands | |

| New Zealand | |

| Northern Ireland | |

| Norway | |

| Scotland | |

| Spain | |

| Sweden | |

| Switzerland | |

| Wales |

Alphabetical order. WEIRD Western, educated, industrialised, rich, and democratic.

Results

Unadjusted and adjusted associations between all cultural characteristics and RC fidelity scores are presented in Table 3. The percentage GDP spent on healthcare and Gini coefficients for each country were included as covariates in adjusted analyses.

Table 3.

Associations between cultural characteristics and overall fidelity scores

| Unadjusted | Adjusted* | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | β (95% CI) | p value | N | β (95% CI) | p value | |

| Power Distance | 167 | −0.03 (−0.08 to 0.01) | 0.126 | 163 | −0.04 (−0.08 to 0.01) | 0.164 |

| Individualism | 167 | 0.05 (0.01 to 0.08) | 0.004 | 163 | 0.06 (0.02 to 0.10) | 0.002 |

| Success-Drivenness | 167 | −0.01 (−0.03 to 0.02) | 0.617 | 163 | −0.01 (−0.04 to 0.02) | 0.463 |

| Uncertainty Avoidance | 167 | −0.03 (−0.06 to −0.01) | 0.009 | 163 | −0.04 (−0.06 to −0.01) | 0.008 |

| Long-Term Orientation | 169 | −0.02 (−0.05 to 0.01) | 0.129 | 165 | −0.03 (−0.06 to −0.01) | 0.050 |

| Indulgence | 169 | 0.04 (0.01 to 0.08) | 0.013 | 165 | 0.05 (0.01 to 0.09) | 0.025 |

*Covariates: % GDP spent on healthcare, Gini coefficient. Bold indicates significant variables.

Hong Kong and New Zealand (2 RCs respectively) are excluded from the adjusted analysis as the Gini coefficients for these countries were not available from the World Bank. RCs in Uganda (n = 2) were included in the Long-Term Orientation and Indulgence only, as data for those two cultural characteristics were available.

Neither the percentage of GDP spent on healthcare and the Gini coefficients of included countries were associated with the fidelity scores, when (a) we examined simple associations between the percentage of GDP spent on healthcare and fidelity, and the Gini coefficients and fidelity, and (b) when we included those as covariates in the models with cultural characteristics.

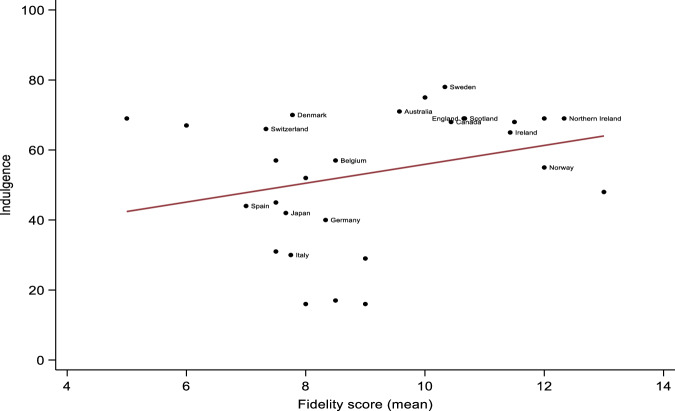

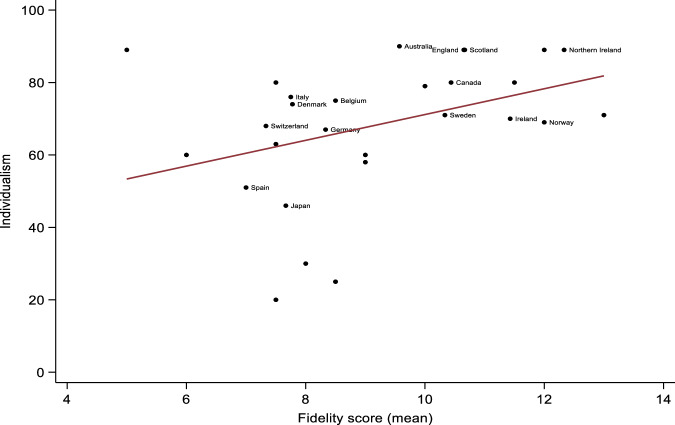

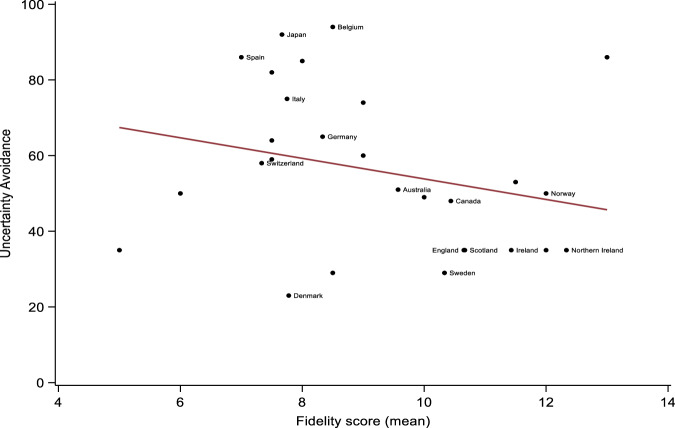

Adjusted mixed-effects linear regressions showed that higher levels of Individualism (β = 0.06, 95% CI = 0.02 to 0.10, p = 0.002), and Indulgence (β = 0.05, 95% CI = 0.01 to 0.09, p = 0.025) were associated with higher fidelity scores. Conversely, higher levels of Uncertainty Avoidance were associated with lower fidelity scores (β = −0.04, 95% CI = −0.06 to −0.01, p = 0.008). Graphic representations of significant associations are provided in Figs. 1 to 3. There were no other significant associations between cultural characteristics and fidelity scores, although adjusted associations between Long-Term Orientation and fidelity could be considered ‘borderline’ (β = −0.03, 95% CI = −0.06 to −0.01, p = 0.050). This suggests that higher levels of Long-Term Orientation were associated with lower fidelity scores, once we accounted for the percentage of GDP spent on healthcare and the Gini coefficients of included countries. Power Distance (Unadjusted β = −0.03, 95% CI = −0.08 to 0.01, p = 0.126; Adjusted β = −0.04, 95% CI = −0.08 to 0.01, p = 0.164) and Success-Drivenness (Unadjusted β = −0.01, 95% CI = −0.03 to 0.02, p = 0.617; Adjusted β = −0.01, 95% CI = −0.04 to 0.02, p = 0.463) were not significantly associated with the RC fidelity scores.

Fig. 2. Association between Indulgence and country-level Recovery College fidelity scores.

Countries with data from <3 Recovery Colleges were blinded for anonymity purposes.

Fig. 1. Association between Individualism and country-level Recovery College fidelity scores.

Countries with data from <3 Recovery Colleges were blinded for anonymity purposes.

Fig. 3. Association between Uncertainty Avoidance and country-level Recovery College fidelity scores.

Countries with data from <3 Recovery Colleges were blinded for anonymity purposes.

Answering research questions

To answer our research questions;

Yes, there are associations between cultural characteristics and the operational indicators of RC fidelity.

Individualism and Indulgence are positively, and Uncertainty Avoidance is negatively associated with the operational indicators of RC fidelity. There are adjusted negative borderline associations between Long-Term Orientation and fidelity. Power Distance and Success-Drivenness are not associated with the fidelity.

This means that RCs operated in cultures that value individual needs (Individualism) and gratification of human needs (Indulgence) tend to receive positive impact on the fidelity of their RC operation. Conversely, RCs operated in cultures that try to avoid uncertain situations (Uncertainty Avoidance) tend to receive negative impact on the fidelity of their RC operation. Cultures that value patience and thriftiness (Long-Term Orientation) may have negative impact on the fidelity as this cultural characteristic was a borderline predictor.

Discussion

In this global study, we found that higher levels of Individualism and Indulgence, and lower levels of Uncertainty Avoidance were associated with higher RC fidelity, with Long-Term Orientation being a borderline negative predictor. Cultures that prioritise needs of an individual and their immediate family (Individualism), that accept relatively free gratification of basic human needs to enjoy life (Indulgence), and that accept unknown situations (low Uncertainty Avoidance, i.e., Uncertainty Acceptance) tended to have higher fidelity. Moreover, cultures that focus on immediate results (low Long-Term Orientation, i.e., Short-Term Orientation) may have positive impact on the fidelity.

The results indicated that cultural characteristics typically associated with WEIRD countries predicted RC fidelity: high on Individualism and Indulgence, and low on Uncertainty Avoidance and Long-Term Orientation32. One interpretation is that the values and assumptions underpinning the RECOLLECT Fidelity Measure are more aligned with the values of WEIRD countries than non-WEIRD countries. RCs originate in, and are most established in, WEIRD countries1. It is possible that assumptions underpinning RCs reflect this origin. The key philosophies of RCs are co-production and adult education, which involve co-delivery of courses by peer and non-peer trainers who may model disagreement, and encourage students to express their individual needs so support can be tailored39. Disagreement and expression of individual needs are more accepted and indeed expected in individualistic and indulgent cultures than collectivistic and restrictive cultures21. Likewise, tolerance for individual and interpersonal differences is more afforded in uncertainty-accepting cultures than uncertainty-avoidant cultures21. Short-term-oriented cultures are more open to new ideas, which could facilitate the incorporation of new practices like RCs21. This may mean that the process of RC operation in non-WEIRD countries need to be understood more. For example, collectivistic cultures prioritise group harmony, therefore processes that are highlighted in co-production and adult education, such as disagreement and expression of individual needs, are in general not as accepted as in individualistic cultures40. Comparatively more people in collectivistic cultures may feel uncomfortable with these processes than those in individualistic cultures41. Moreover, people in collectivistic cultures in general tend to be more susceptible to shame towards mental health symptoms than those in individualistic cultures42. A better understanding of RC operation in non-WEIRD countries can inform how the current RC operation should be adjusted to maximise the global impact. The insights about cultural adaptation of RC operation can also help maximise the impact on minority culture groups within a country.

The findings of cultural influences on RC fidelity also raise concerns about ethnocentrism in valued outcomes. RC outcomes such as self-management and self-confidence4 may be more aligned with WEIRD cultures than non-WEIRD ones. Embedded assumptions in RCs about the importance of self-management may create a culture clash with student aspirations in collectivistic cultures to be seen as self-managing for not disclosing mental health symptoms to others43. This negative valorisation of an outcome, which is a focus of the RC, may lead students to disengage. Likewise, self-confidence is not as accepted in many non-WEIRD countries as in WEIRD countries44. Inclusion of more collective outcomes such as collective happiness45 where one feels happy when they know they are as happy as their peers instead of happier than their peers, may enhance cultural inclusivity of RC operation. Likewise, as a recent cross-cultural comparison of the RC advertisement texts reported, how RC students “learn together” (Collectivism) and experience “life-long learning” (Long-Term Orientation) may also need to be assessed to be inclusive of non-WEIRD cultures. These non-WEIRD outcomes can help people in RCs consider their wider community27, leading to a more holistic understanding of mental health and recovery46,47.

Regarding RC research, our results may highlight a need for a more culturally-informed measurement tool. Self-report measures are vulnerable to response bias, and respondents in WEIRD countries tend to demonstrate self-enhancement effects42. Self-enhancement is less encouraged in non-WEIRD cultures, as it could violate group harmony21. It is possible that even with the same level of fidelity, RC managers in WEIRD countries assessed their RC fidelity as high, whereas RC managers in non-WEIRD countries assessed theirs as low. If RC managers in non-WEIRD countries felt RC operation is oriented to WEIRD cultures, the self-enhancement of WEIRD managers might be even further accentuated23. Additionally, there was variance in fidelity scores among WEIRD countries. This variance may be attributed to factors such as (a) the RECOLLECT Fidelity Measure weighing all components equally,(b) variance in cultural characteristics among WEIRD countries, and (c) potential response biases among assessors. Future research should (a) evaluate the relative importance of each component, (b) compare cultures within WEIRD countries, and (c) involve individuals other than RC managers in the assessment of fidelity.

Our study has three implications for RC development and evaluation. First, the adult education focus needs to be inclusive of people from cultures that are not familiar with expression of, and adjustment for, individual needs. This can help include more people in cultures that value Collectivism and Self-Restraint (contrasting values to Individualism and Indulgence). Culturally appropriate approaches to supporting identification of needs, for example involving collective (e.g., family members) rather than individual decision-making, may be needed to ensure that changes in the student are positively valorised in their community. Second, the co-production focus needs to be interpreted through local cultural values. For example, recognising that higher external stigma (as opposed to internal stigma)48 experiences in non-WEIRD countries44 may require the peer trainer role to be modified to include individuals with lived experience as informal carers. The external presence of the peer trainer with lived experience can help reduce external stigma by supporting common humanity—awareness that it is not only them who experience mental health symptoms49. This can help include people oriented to cultures that value Long-Term Orientation as acknowledgement of difficulties in life is related to this value50,51. Moreover, whether co-production is a universally-accepted concept or not, needs to be discussed. In some non-WEIRD settings (e.g., Japanese and Thai cultures), clinical decision-making models developed in the West, have been challenged, because the models required individual service users to express their needs independently52,53. Cultural adaptation of RCs should include revisiting the key philosophies of RCs, to appraise the fitness to some non-WEIRD cultural characteristics. This can help ensure that good operation practice in one cultural context is not imposed on people in other cultural contexts. Epistemic injustice—people from marginalised groups are denied the chance to contribute to knowledge and interpret their own experiences—is increasingly gaining attention in mental health care54, and our findings can help manifest epistemic injustice in RCs. Finally, a culturally-adapted fidelity assessment approach is indicated. The advantages of using self-report measures, such as simplicity and timeliness, are helpful to RC research. However, the RECOLLECT Fidelity Measure can be refined by incorporating more non-WEIRD perspectives. This refinement includes addition/adjustment of items or wording, and culturally-adaptable translation that prioritises conceptual equivalence, instead of direct linguistic equivalence alone55. For example, the item about “Tailoring to students” is more relevant to uncertainty-accepting cultures, allowing individual differences21. Measures such as providing examples, and asking about previous student cases can help better understand about this item for more people in uncertainty-avoidant culture56.

Strengths of our study include it being the first global cross-cultural study of RCs in 28 countries, informing RC development globally. Service disparity for minority cultures is a global mental health concern, associated with poor service uptake, adverse mental health outcomes, and increased costs25. RCs are operating in 28 countries including low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). Our findings can inform cultural adaptation of RCs, helping to address service disparity. Additionally, the numbers of RCs in non-WEIRD countries, including LMICs (Table 4), suggest they may be in the early stages of RC implementation. Our findings could guide the initial steps towards scaling RCs in those countries. The establishment of more RCs in non-WEIRD countries would promote the inclusion of diverse cultures in RC operations worldwide. Although our study included all operational RCs globally, participation from non-WEIRD countries was limited, with only 15 RCs from four such countries represented. To better understand RC cultural adaptations in non-WEIRD contexts, a greater presence of non-WEIRD RCs is needed. Several study limitations can be identified. First, there are other cross-cultural frameworks that could have been used (e.g., tightness-looseness57). However, data for many of the 28 countries were not available, making meaningful comparisons problematic. Relatedly, critiques of Hofstede’s definition of culture32 include overgeneralisation such as treating nations as a cultural unit58 and under-emphasis on non-psychological cultural aspects such as socioeconomic and ecosocial factors59,60. To effectively inform the cultural adaptation of RC, these factors must be assessed using more in-depth approaches61. For example, community-based participatory research, which involves close collaboration with local communities, stakeholders, and cultural minority groups, is recommended to identify the most appropriate cultural adaptations62. Common research processes in WEIRD countries, such as interviews, can make people in non-WEIRD countries feel like ‘subjects’ thus may not capture authentic responses. Culturally appropriate processes, such as casually asking around in their natural environment (e.g., Pagtatanong-tanong in the Philipines63), can be more effective in eliciting genuine responses that are useful for cultural adaptations64. Moreover, the person-centred approach to recovery that RCs emphasise, may seem contradictory to our evaluation on cultures. However, the cultural dimension scores regard collective tendencies, instead of personal factors32. Therefore, our findings inform associations between cultural characteristics and RC operation. Second, although we included two relevant confounders in fully adjusted analysis, it is possible there were unmeasured confounders that may bias our results. We used these two confounders due to their relevance to mental health treatment resources65 and Hofstede’s index35,36, and the significant global variation in financial statuses for RC operations2. However, since no studies have directly examined the relationship between Hofstede’s index and mental health intervention fidelity, other country-level confounders, such as trust in government66, may also be relevant. Third, RCs with missing data for outcomes of interest or confounders were excluded. The uneven distribution of RCs across countries limits the robustness of the findings. Fourth, the survey was completed by service managers, therefore may not reflect the other people’s perspectives. Following the philosophy of RCs, the fidelity assessment should be done by RC students too. This raises the deeper issue of reducing fidelity to a quantitative score (as done with the RECOLLECT Fidelity Measure in this study), which may not capture many important operating characteristics, such as psychological safety and the impact of the built environment on student and trainer wellbeing. Future research should involve student assessment after addressing ethical concerns, with rigorous and reasonable sampling methods in each country or context (e.g., how to identify people who can assess an RC comprehensively). Consideration should also be given to developing more qualitative approaches to characterising fidelity, for example using the Impacts of Recovery Innovations (IMRI) framework67. Lastly, as cultures and practice change over time, cross-cultural understanding of RCs needs to be investigated periodically.

Table 4.

STROBE guidelines

| Item No. | Recommendation | Page No. | Relevant text from manuscript | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Title and abstract | 1 | (a) Indicate the study’s design with a commonly used term in the title or the abstract | 1, 5 | “associations” in the title and abstract. “linear mixed-effects regression models“ in the abstract. |

| (b) Provide in the abstract an informative and balanced summary of what was done and what was found | 5 |

What was done: “RC fidelity data were collected from 169 of all 221 RCs currently operating, spanning 28 WEIRD and non-WEIRD countries. Hofstede’s cultural dimension scores were entered as predictors in linear mixed-effects regression models, controlling for GDP percentage spent on healthcare and Gini coefficient.” What was found: “Higher Individualism (β = 0.06) and Indulgence (β = 0.05), as well as lower Uncertainty Avoidance (β = −0.04) were associated with higher RC fidelity with Long-Term Orientation being a borderline negative predictor of the fidelity (β = −0.03).” |

||

| Introduction | ||||

| Background/rationale | 2 | Explain the scientific background and rationale for the investigation being reported | 6–8 |

The scientific background: Despite RCs located in many countries including both WEIRD countries and non-WEIRD countries, evidence base for how RCs can help mental health recovery is oriented to WEIRD countries only. There are six reviews about RCs, and all included studies apart from one international study were from WEIRD countries (185 included studies in total). Rationale: Cross-cultural understanding of RCs remains to be developed. RCs are in operation in non-WEIRD countries including low- and middle-income countries. |

| Objectives | 3 | State specific objectives, including any prespecified hypotheses | 8 |

“This study aimed to explore the relationships between cultural characteristics and fidelity in all currently-operating RCs internationally. RC inclusion criteria were targeting to support personal recovery, and prioritising co-production and adult learning. Our research questions were; 1. Are there associations between cultural characteristics and the operational indicators of RC fidelity?, and 2. If there are, which cultural characteristics are associated with the operational indicators of RC fidelity?” Addressing these research questions is intended to identify cultural impact on RC fidelity. Because RCs are in operation in many countries, identifying the cultural impact of RC operation will be useful to cross-cultural understanding of RC operation, and by extension, will have relevance to other recovery-oriented global innovations, such as mental health peer support work37. We recruited RCs that were currently in operation from 28 countries across different cultures (Table 2 for the participating WEIRD and non-WEIRD countries), and evaluated whether differences in cultural characteristics could predict variance in their fidelity scores. Mixed-effects linear regression models with a country-level random intercept were used to allow us to identify associations between the cultural characteristics and RC fidelity while accounting for variability between countries. No hypotheses were predefined due to the exploratory and inductive nature of the research38. |

| Methods | ||||

| Study design | 4 | Present key elements of study design early in the paper | 1, 5, 8 and 12 | Noted above, in 1(a) and 3. Additionally, “We conducted a cross-sectional, observational survey in two rounds: first of all RCs in England (“England survey”)3, then of RCs in all other countries (“international survey”)2. Approval was obtained from King’s College London Research Ethics Psychiatry Nursing and Midwifery Subcommittee on 09/02/22 (MRA-21/22-28685). All participants provided written informed consent prior to completing the survey. The study was conducted as part of the RECOLLECT programme16. RECOLLECT is a five-year (2020-2025) National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR)-funded research programme exploring the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of RCs16.” |

| Setting | 5 | Describe the setting, locations, and relevant dates, including periods of recruitment, exposure, follow-up, and data collection | 12 | “We included all RCs whose managers completed the RECOLLECT Fidelity Measure between August and October 2021 for the England survey, and between February and October 2022 for the international survey. |

| Participants | 6 | (a) Cross-sectional study—Give the eligibility criteria, and the sources and methods of selection of participants | 13 and Supplementary Information 2 | “Because not all RCs named themselves a “Recovery College” (e.g., “Recovery Academy”, “Recovery School”), we included any currently active services that met three criteria, informed by the key RC components4. The criteria were: (a) targeting to support personal recovery; (b) prioritising co-production and (c) adult learning, and were confirmed by the service managers. Full details are reported elsewhere2, and presented in Supplementary Information 2.” |

| Variables | 7 | Clearly define all outcomes, exposures, predictors, potential confounders, and effect modifiers. Give diagnostic criteria, if applicable | 14 | Outcome variable, predictor variables, and confounder variables are defined. |

| Data sources/ measurement | 8 | For each variable of interest, give sources of data and details of methods of assessment (measurement). Describe comparability of assessment methods if there is more than one group | 13-14 |

“Fidelity was measured using the seven nonmodifiable components of the RECOLLECT Fidelity Measure4, completed by the manager of each RC.” Predictor variable: “Data for the cultural characteristics were obtained from Hofstede70…. The data were collected using the Value Survey Module 2013” Confounder variables: “Two confounder variables were included in the fully adjusted analyses, as relevant to mental health treatment resources65 and Hofstede’s index35,36, as well as the significant global variation in financial statuses for RC operations2. The percentage of GDP spent on health is the amount spent on healthcare relative to the economy size, calculated by the total health expenditure divided by GDP72. The Gini coefficient for each country indicates the income inequality within a nation, expressed from 0 (perfect equality) to 1 (maximum inequality), obtained from the World Bank73.” |

| Bias | 9 | Describe any efforts to address potential sources of bias | 14 | “Fidelity scores were summarised as medians and interquartile ranges where possible (i.e. for countries which provided fidelity data for multiple RCs). In order to examine unadjusted and adjusted associations between each cultural characteristic (country-level) and fidelity scores (college-level), we used mixed-effects linear regression models with a country-level random intercept in order to account for variability between countries. Adjusted associations included the percentage of GDP spent on healthcare and the Gini coefficient for each country as potential confounders. Uganda were missing data for Power Distance, Individualism, Success-Drivenness, and Uncertainty Avoidance, and was therefore excluded from analyses involving these cultural predictors. Gini coefficients for Hong Kong and New Zealand were unavailable from the World Bank due to high costs (Personal communication on 28 April 2023, The World Bank, Development Economics Data Group): these two countries were omitted from adjusted mixed-effects linear regression models.” |

| Study size | 10 | Explain how the study size was arrived at | 12-13 | “We included all RCs whose managers completed the RECOLLECT Fidelity Measure between August and October 2021 for the England survey, and between February and October 2022 for the international survey.”Three steps were followed for both surveys: (1) Developing RC inclusion criteria, (2) Identifying and approaching potentially eligible RCs, and (3) Disseminating and collecting the survey.” |

| Quantitative variables | 11 | Explain how quantitative variables were handled in the analyses. If applicable, describe which groupings were chosen and why | 13-14 | All quantitative variables were handled as continuous variables. This is detailed for Fidelity, Cultural Characteristics, and confounder variables. |

| Statistical methods | 12 | (a) Describe all statistical methods, including those used to control for confounding | 14-15 | Mixed-effects linear regression models - efforts to control for confounding are described in the Statistical analysis section. |

| (b) Describe any methods used to examine subgroups and interactions | N/A | The examination of subgroups or interactions was not applicable in this study | ||

| (c) Explain how missing data were addressed | 14-15 and Table 3 | Complete case analysis - countries were omitted from analyses if data were missing. Imputation was not appropriate. | ||

| (d) Cross-sectional study—If applicable, describe analytical methods taking account of sampling strategy | N/A | A complex sampling strategy was not used in this study, so we did not need to adjust for this. | ||

| (e) Describe any sensitivity analyses | N/A | No sensitivity analyses were performed. | ||

| Results | ||||

| Participants | 13 | (a) Report numbers of individuals at each stage of study—e.g. numbers potentially eligible, examined for eligibility, confirmed eligible, included in the study, completing follow-up, and analysed | 14 and Table 5 | “The surveys were completed by 169 (76%) RC managers from 28 countries, with more than 55,000 students attending in total. A description of the sample and summaries of variables of interest are provided in Table 5.” |

| (b) Give reasons for non-participation at each stage | 14–15 and Table 5 | Statistical analysis section and Table 5 provide sample sizes that indicate non-participation in analyses. | ||

| (c) Consider use of a flow diagram | N/A | |||

| Descriptive data | 14 | (a) Give characteristics of study participants (ego demographic, clinical, social) and information on exposures and potential confounders | Table 5 | |

| (b) Indicate number of participants with missing data for each variable of interest | Table 3 | The number of colleges with missing data for certain variables are provided in Table 3 (e.g., Gini coefficient missing for New Zealand = 2 RCs). | ||

| (c) Cohort study—Summarise follow-up time (e.g., average and total amount) | N/A | |||

| Outcome data | 15 | Cross-sectional study—Report numbers of outcome events or summary measures | Table 3 | |

| Main results | 16 | (a) Give unadjusted estimates and, if applicable, confounder-adjusted estimates and their precision (ego, 95% confidence interval). Make clear which confounders were adjusted for and why they were included | Table 3 | Unadjusted and adjusted estimates and 95% CI are provided. Table 3 also reports the results of all outcomes, both significant and no significant associations. Clear list of covariates in table footnote. |

| (b) Report category boundaries when continuous variables were categorized | N/A | No continuous variables were categorised. | ||

| (c) If relevant, consider translating estimates of relative risk into absolute risk for a meaningful time period | N/A | We do not report relative risk. | ||

| Other analyses | 17 | Report other analyses done—e.g. analyses of subgroups and interactions, and sensitivity analyses | None | |

| Discussion | ||||

| Key results | 18 | Summarise key results with reference to study objectives | 10 | “In this global study, we found that higher levels of Individualism and Indulgence, and lower levels of Uncertainty Avoidance were associated with higher RC fidelity scores, with Long-Term Orientation being a borderline negative predictor.” |

| Limitations | 19 | Discuss limitations of the study, taking into account sources of potential bias or imprecision. Discuss both direction and magnitude of any potential bias | 11-12 | “Strengths of our study include it being the first global cross-cultural study of RCs in 28 countries, informing RC development globally. Service disparity for minority cultures is a global mental health concern, associated with poor service uptake, adverse mental health outcomes, and increased costs25. RCs are operating in 28 countries including low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). Our findings can inform cultural adaptation of RCs, helping to address service disparity. Additionally, the numbers of RCs in non-WEIRD countries, including LMICs (Table 4), suggest they may be in the early stages of RC implementation. Our findings could guide the initial steps towards scaling RCs in those countries. The establishment of more RCs in non-WEIRD countries would promote the inclusion of diverse cultures in RC operations worldwide. Although our study included all operational RCs globally, participation from non-WEIRD countries was limited, with only 15 RCs from four such countries represented. To better understand RC cultural adaptations in non-WEIRD contexts, a greater presence of non-WEIRD RCs is needed. Several study limitations can be identified. First, there are other cross-cultural frameworks that could have been used (e.g., tightness-looseness57). However, data for many of the 28 countries were not available, making meaningful comparisons problematic. Relatedly, critiques of Hofstede’s definition of culture32 include overgeneralisation such as treating nations as a cultural unit58 and under-emphasis on non-psychological cultural aspects such as socioeconomic and ecosocial factors59,60. To effectively inform the cultural adaptation of RC, these factors must be assessed using more in-depth approaches61. For example, community-based participatory research, which involves close collaboration with local communities, stakeholders, and cultural minority groups, is recommended to identify the most appropriate cultural adaptations62. Common research processes in WEIRD countries, such as interviews, can make people in non-WEIRD countries feel like ‘subjects’ thus may not capture authentic responses. Culturally appropriate processes, such as casually asking around in their natural environment (e.g., Pagtatanong-tanong in the Philipines63), can be more effective in eliciting genuine responses that are useful for cultural adaptations64. Moreover, the person-centred approach to recovery that RCs emphasise, may seem contradictory to our evaluation on cultures. However, the cultural dimension scores regard collective tendencies, instead of personal factors32. Therefore, our findings inform associations between cultural characteristics and RC operation. Second, although we included two relevant confounders in fully adjusted analysis, it is possible there were unmeasured confounders that may bias our results. We used these two confounders due to their relevance to mental health treatment resources65 and Hofstede’s index35,36, and the significant global variation in financial statuses for RC operations2. However, since no studies have directly examined the relationship between Hofstede’s index and mental health intervention fidelity, other country-level confounders, such as trust in government66, may also be relevant. Third, RCs with missing data for outcomes of interest or confounders were excluded. The uneven distribution of RCs across countries limits the robustness of the findings. Fourth, the survey was completed by service managers, therefore may not reflect the other people’s perspectives. Following the philosophy of RCs, the fidelity assessment should be done by RC students too. This raises the deeper issue of reducing fidelity to a quantitative score (as done with the RECOLLECT Fidelity Measure in this study), which may not capture many important operating characteristics, such as psychological safety and the impact of the built environment on student and trainer wellbeing. Future research should involve student assessment after addressing ethical concerns, with rigorous and reasonable sampling methods in each country or context (e.g., how to identify people who can assess an RC comprehensively). Consideration should also be given to developing more qualitative approaches to characterising fidelity, for example using the Impacts of Recovery Innovations (IMRI) framework67. Lastly, as cultures and practice change over time, cross-cultural understanding of RCs needs to be investigated periodically.” |

| Interpretation | 20 | Give a cautious overall interpretation of results considering objectives, limitations, multiplicity of analyses, results from similar studies, and other relevant evidence | 10-12 |

From “The results indicated that characteristics typically associated with WEIRD countries predicted RC fidelity.” To “Lastly, as cultures and practice change over time, cross-cultural understanding of RCs needs to be investigated periodically.” |

| Generalisability | 21 | Discuss the generalisability (external validity) of the study results | 10 |

From “The results indicated that characteristics typically associated with WEIRD countries predicted RC fidelity.” To “leading to a more holistic understanding of mental health and recovery46,47.” |

| Other information | ||||

| Funding | 22 | Give the source of funding and the role of the funders for the present study and, if applicable, for the original study on which the present article is based | 12 | “The study was conducted as part of the RECOLLECT programme16. RECOLLECT is a five-year (2020-2025) National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR)-funded research programme exploring the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of RCs16.” |

RCs are a relatively new approach to mental health recovery. Currently, RC research and operations remain focused on WEIRD contexts, with non-WEIRD cultures being under-represented. However, the extent to which RC research and operations are WEIRD-focused had not been empirically assessed until now. Our findings identified Individualism, Indulgence and Uncertainty Avoidance as significant predictors, and Long-Term Orientation as a borderline predictor of fidelity. These cultural characteristics can serve as the first step towards an empirically informed cultural adaption of RCs and other recovery-oriented complex interventions, maximising their global health impact.

Methods

Study design

We conducted a cross-sectional, observational survey in two rounds: first of all RCs in England (“England survey”)3, then of RCs in all other countries (“international survey”)2. Approval was obtained from King’s College London Research Ethics Psychiatry Nursing and Midwifery Subcommittee on 09/02/22 (MRA-21/22-28685). All participants provided written informed consent prior to completing the survey. The study was conducted as part of the RECOLLECT programme16. RECOLLECT is a five-year (2020-2025) National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR)-funded research programme exploring the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of RCs16.

We included all RCs whose managers completed the RECOLLECT Fidelity Measure between August and October 2021 for the England survey, and between February and October 2022 for the international survey. In total, 28 countries from Africa, Asia, Europe, North America, and Oceania, were included. This study is a post-hoc analysis of data obtained from the England3 and international surveys2, targeting the cultural aspects of RCs. The STROBE guidelines were followed (Table 4).

Procedures

Three steps were followed for both surveys: (1) Developing RC inclusion criteria, (2) Identifying and approaching potentially eligible RCs, and (3) Disseminating and collecting the survey.

(1) Developing RC inclusion criteria: Because not all RCs named themselves a “Recovery College” (e.g., “Recovery Academy”, “Recovery School”), we included any currently active services that met three criteria, informed by the key RC components4. The criteria were (a) targeting to support personal recovery; (b) prioritising co-production and (c) adult learning, and were confirmed by the service managers. Full details are reported elsewhere2, and presented in Supplementary Information 2.

(2) Identifying and approaching potentially eligible RCs: For the England survey, four approaches were undertaken to identify potentially eligible RCs in June and July 2021: (a) online searches; (b) consultation with RC national leaders and recovery networks such as ImROC (imroc.org); (c) snowball sampling, and (d) telephone calls to potential host charities and mental health service providers. The research team approached the identified to ensure whether the service met the inclusion criteria.

For the international survey, first, RC operating countries were identified. An initial list of countries was created through (a) a RC international survey18, (b) enquires to existing RC organisations, (c) expert consultation with 23 recovery experts, and (d) communications with our collaborators in countries where similar services were available (e.g., peer support). Second, we identified country leads in the listed countries using networks developed in the previous process. Each country lead searched the literature in their local language to identify RCs in their country. Third, country leads discussed with the service managers to ascertain whether their service met the inclusion criteria. Snowball sampling was used asking whether those managers knew of any other services that might meet the criteria.

(3) Disseminating and collecting the survey: For the England survey, a pilot survey was created using the Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet E-Surveys (CHERRIES) guidelines68, revised based on expert review, and responded by two RC managers. No changes were made to the fidelity measure3. The eligible service managers were asked to complete the survey on Qualtrics.

The international survey was adapted from the England survey by adjusting phrases (e.g., “NHS services” to “health services”). The adapted survey was piloted by three RC experts in Australia, Canada, and Japan. No changes were made to the fidelity measure2. The final version was sent out by country leads to RC managers in their countries in two forms, Qualtrics and Microsoft Word. In countries where English was not commonly used and multiple RCs were in operation, the country leads were asked to translate the survey into their local language using Microsoft Word. The translated version was communicated to RC managers in an online or in-person meeting, or a written document. The accuracy of each translation was checked by a second translator. Seven language versions were developed69: Danish, Dutch, French, German, Japanese, Mandarin-Chinese, and Norwegian. Completed Qualtrics survey responses were directly accessible by the research team. Completed Microsoft Word survey responses were encrypted and emailed to the research team by the RC manager or the country lead. The research team then input the data to the Qualtrics. Data from the England survey and the international survey were integrated. No financial incentives were offered in either survey.

Eligible RCs

For the England survey, 134 services were identified as potentially eligible, of which 88 (66%) were confirmed to meet the inclusion criteria. 46 services were excluded, most commonly due to being non-contactable and deemed no longer operating (n = 20). Full details of exclusion reasons are reported elsewhere3.

For the international survey, 49 countries were included in the initial list as a potentially RC operating country. After expert consultation and country leads’ searches, the final list was made involving 30 countries with 211 potential RCs identified. Country leads contacted all potential RCs in their country. Two countries and 78 potential RCs were removed for not meeting the RC inclusion criteria. The most common reason for exclusion was non-contactable and deemed no longer operating (n = 22). Full details of exclusion reasons are reported elsewhere2.

Participating RCs

The two surveys indicated that in 2021/2022 there were 221 RCs in 28 countries across Europe, Asia, Africa, North America and Oceania, with none in South America or Antarctica. The surveys were completed by 169 (76%) RC managers from 28 countries, with more than 55,000 students attending in total2,3. A description of the sample and summaries of variables of interest are provided in Table 5.

Table 5.

Sample characteristics

| Country (n = 28) | Recovery College (n = 169/221: responded/total) | % GDP spent on healthcare | Gini coefficient | Fidelity scores (median (IQR)) | Power Distance | Individualism | Success-Drivenness | Uncertainty Avoidance | Long-Term Orientation | Indulgence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Africa (n = 1) | 2/2 | |||||||||

| Uganda | 2/2 | 3.8 | 42.8 | Blinded | - | - | - | - | 24 | 52 |

| Asia (n = 3) | 13/15 | |||||||||

| Hong Kong | 2/2 | 5.3 | - | Blinded | 68 | 25 | 57 | 29 | 61 | 17 |

| Japan | 9/11 | 10.7 | 32.9 | 7 (6 to 10) | 54 | 46 | 95 | 92 | 88 | 42 |

| Thailand | 2/2 | 3.8 | 36.4 | Blinded | 64 | 20 | 34 | 64 | 32 | 45 |

| Europe (n = 21) | 129/170 | |||||||||

| Belgium | 10/14 | 10.7 | 27.2 | 8.5 (8 to 10) | 65 | 75 | 54 | 94 | 82 | 57 |

| Bulgaria | 1/1 | 7.1 | 41.3 | Blinded | 70 | 30 | 40 | 85 | 69 | 16 |

| Czechia | 1/1 | 7.8 | 25.0 | Blinded | 57 | 58 | 57 | 74 | 70 | 29 |

| Denmark | 9/9 | 10.0 | 28.2 | 8 (6 to 9) | 18 | 74 | 16 | 23 | 35 | 70 |

| England | 63/88 | 10.1 | 35.1 | 11 (9 to 13) | 35 | 89 | 66 | 35 | 51 | 69 |

| Estonia | 2/2 | 6.7 | 30.3 | Blinded | 40 | 60 | 30 | 60 | 82 | 16 |

| Finland | 2/2 | 9.1 | 27.3 | Blinded | 33 | 63 | 26 | 59 | 38 | 57 |

| France | 1/1 | 11.1 | 32.4 | Blinded | 68 | 71 | 43 | 86 | 63 | 48 |

| Germany | 3/3 | 11.7 | 31.7 | 9 (6 to 10) | 35 | 67 | 66 | 65 | 83 | 40 |

| Hungary | 2/3 | 6.3 | 29.6 | Blinded | 46 | 80 | 88 | 82 | 58 | 31 |

| Iceland | 1/1 | 8.6 | 26.1 | Blinded | 30 | 60 | 10 | 50 | 28 | 67 |

| Ireland | 7/11 | 6.7 | 30.6 | 11 (10 to 13) | 28 | 70 | 68 | 35 | 24 | 65 |

| Italy | 4/4 | 8.7 | 35.2 | 7.5 (5 to 10.5) | 50 | 76 | 70 | 75 | 61 | 30 |

| Jerseya | 1/1 | 10.1 | 35.1 | Blinded | 35 | 89 | 66 | 35 | 51 | 69 |

| Netherlands | 2/2 | 10.1 | 28.1 | Blinded | 38 | 80 | 14 | 53 | 67 | 68 |

| Northern Ireland | 3/4 | 10.1 | 35.1 | 13 (10 to 14) | 35 | 89 | 66 | 35 | 51 | 69 |

| Norway | 4/5 | 10.5 | 27.6 | 12.5 (11 to 13) | 31 | 69 | 8 | 50 | 35 | 55 |

| Scotland | 3/3 | 10.1 | 35.1 | 11 (9 to 12) | 35 | 89 | 66 | 35 | 51 | 69 |

| Spain | 3/6 | 9.1 | 34.7 | 6 (5 to 10) | 57 | 51 | 42 | 86 | 48 | 44 |

| Sweden | 3/3 | 10.9 | 30.0 | 11 (6 to 14) | 31 | 71 | 5 | 29 | 53 | 78 |

| Switzerland | 3/4 | 11.3 | 33.1 | 8 (5 to 9) | 34 | 68 | 70 | 58 | 74 | 66 |

| Wales | 1/2 | 10.1 | 35.1 | Blinded | 35 | 89 | 66 | 35 | 51 | 69 |

| Oceania (n = 2) | 9/11 | |||||||||

| Australia | 7/9 | 9.9 | 34.3 | 10 (6 to 13) | 38 | 90 | 61 | 51 | 21 | 71 |

| New Zealand | 2/2 | 9.7 | - | Blinded | 22 | 79 | 58 | 49 | 33 | 75 |

| North America (n = 1) | 16/23 | |||||||||

| Canada | 16/23 | 10.8 | 33.3 | 10.5 (9 to 12) | 39 | 80 | 52 | 19 | 36 | 68 |

aJersey is a self-governing dependency of the UK and was not included in the overall number of countries, and not included in the analysis.

Most participating RCs (159 RCs; 94%) were located in WEIRD countries.

Fidelity scores (Outcome variable)

Fidelity was measured using the seven nonmodifiable components of the RECOLLECT Fidelity Measure4, completed by the manager of each RC. The seven components are (1) equality, (2) adult learning, (3) tailoring to the student, (4) co-production, (5) social connectedness, (6) community focus, and (7) commitment to recovery. Responses are on a three-point ordinal scale from 0 (low fidelity) to 24. The fidelity score is the sum of these seven items, ranging from 0 (low fidelity) to 14. The measure satisfies scaling assumptions, demonstrating adequate internal consistency (0.72), test–retest reliability (0.60), content validity and discriminant validity4.

Cultural characteristics (Predictor variables)

Data for the cultural characteristics were obtained from Hofstede70. This dataset provides scores for the six cultural dimensions of 111 countries. The data were collected using the Value Survey Module 2013, a 24-item self-report measure responded on a five-point Likert scale from 1 to 571. Each dimension score is calculated using mean scores of four different items and index formulas in the manual, presented from 0 (low) to 10071.

Confounder variables

Two confounder variables were included in the fully adjusted analyses, as relevant to mental health treatment resources65 and Hofstede’s index35,36, as well as the significant global variation in financial statuses for RC operations2. The percentage of GDP spent on health is the amount spent on healthcare relative to the economy size, calculated by the total health expenditure divided by GDP72. The Gini coefficient for each country indicates the income inequality within a nation, expressed from 0 (perfect equality) to 1 (maximum inequality), obtained from the World Bank73.

Statistical analysis

Fidelity scores were summarised as medians and interquartile ranges where possible (i.e. for countries which provided fidelity data for multiple RCs). In order to examine unadjusted and adjusted associations between each cultural characteristic (country-level) and fidelity scores (college-level), we used mixed-effects linear regression models with a country-level random intercept in order to account for variability between countries. Adjusted associations included the percentage of GDP spent on healthcare and the Gini coefficient for each country as potential confounders. Uganda were missing data for Power Distance, Individualism, Success-Drivenness, and Uncertainty Avoidance, and was therefore excluded from analyses involving these cultural predictors. Gini coefficients for Hong Kong and New Zealand were unavailable from the World Bank due to high costs (Personal communication on 28 April 2023, The World Bank, Development Economics Data Group): these two countries were omitted from adjusted mixed-effects linear regression models. All analyses were conducted using STATA 17.0 (StataCorp LLP, College Station, TX).

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We express our appreciation to Professor Gert Jan Hofstede for his helpful advice. We would like to thank Nigel Henderson who helped facilitate the completion of RC surveys in Scotland. We thank the RECOLLECT Lived Experience Advisory Panel (LEAP) who provided input into the design of the survey and interpretation of results. MS acknowledges the support of NIHR Nottingham Biomedical Research Centre.

Author contributions

Y.K. conceptualised the study. Y.K. conducted the literature search. D.H. and H.H-B. were responsible for project administration. D.H., H.H-B., A.R., E.C., C.He, and M.S. were responsible for the study design. D.H., H.H-B., V.S., L.B., C.D.R., M.O., P.K., L.E., C.T., D.N., A.T., B.P., R.H., F.L., Y.M., S.C., M.B., T.G.K., R.T.B.M., C.S., K.T., M.F., H.M.J., A.B., R.M., S.Ts., Z.K., M.R., G.Z., C.Har., W.V., S.A., D.S., U.B., C.L., S.O., M.G.F., and J.T. were responsible for data collection and interpretation. A.R., E.C., C.He., and M.S. were responsible for data analysis. Y.K., A.R., D.H., H.H.B., E.C., C.He., M.S., J.R., S.M., C.Han., D.E., J.G.R., M.M., D.D., C.Y., K.S., T.J., S.Ta. and I.B. were involved in data interpretation. Y.K., A.R. and M.S. were involved in the writing the original draft. All authors were involved in reviewing and editing the manuscript and approved the final version. Y.K., C.He., and M.S. were responsible for the decision to submit the manuscript. D.H., A.R., and E.C. have accessed and verified the data. All authors had access to all data in this survey.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to it containing identifiable information about RCs.

Code availability

No code was used in this study.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Claire Henderson, Mike Slade.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s44184-024-00092-9.

References

- 1.Slade, M. et al. Uses and abuses of recovery: implementing recovery-oriented practices in mental health systems. World Psychiatry13, 12–20, 10.1002/wps.20084 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hayes, D. et al. Organisational and student characteristics, fidelity, funding models, and unit costs of recovery colleges in 28 countries: a cross-sectional survey. Lancet Psychiatry10, 768–779, 10.1016/S2215-0366(23)00229-8 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hayes, D. et al. Evidence-based Recovery Colleges: developing a typology based on organisational characteristics, fidelity and funding. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol.10.1007/s00127-023-02452-w (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Toney, R. et al. Development and Evaluation of a Recovery College Fidelity Measure. Can. J. Psychiatry64, 405–414, 10.1177/0706743718815893 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Toney, R. et al. Mechanisms of Action and Outcomes for Students in Recovery Colleges. Psychiatr. Serv.69, 1222–1229, 10.1176/appi.ps.201800283 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thériault, J., Lord, M.-M., Briand, C., Piat, M. & Meddings, S. Recovery Colleges After a Decade of Research: A Literature Review. Psychiatr. Serv.71, 928–940, 10.1176/appi.ps.201900352 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lin, E. et al. Developing an evaluation framework for assessing the impact of recovery colleges: protocol for a participatory stakeholder engagement process and cocreated scoping review. BMJ Open12, e055289, 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-055289 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kelly, J., Gallagher, S. & McMahon, J. Developing a recovery college: a preliminary exercise in establishing regional readiness and community needs. J. Ment. Health26, 150–155, 10.1080/09638237.2016.1207227 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meddings, S., McGregor, J., Roeg, W. & Shepherd, G. Recovery colleges: quality and outcomes. Ment. Health Soc. Incl.19, 212–221, 10.1108/MHSI-08-2015-0035 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crowther, A. et al. The impact of Recovery Colleges on mental health staff, services and society. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci.28, 481–488, 10.1017/S204579601800063X (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Whish, R., Huckle, C. & Mason, O. What is the impact of recovery colleges on students? A thematic synthesis of qualitative evidence. J. Ment. Health Train., Educ. Pract.17, 443–454, 10.1108/JMHTEP-11-2021-0130 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bourne, P., Meddings, S. & Whittington, A. An evaluation of service use outcomes in a Recovery College. J. Ment. Health27, 359–366, 10.1080/09638237.2017.1417557 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kay, K. & Edgley, G. Evaluation of a new recovery college: delivering health outcomes and cost efficiencies via an educational approach. Ment. Health Soc. Incl.23, 36–46, 10.1108/mhsi-10-2018-0035 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cronin, P., Stein-Parbury, J., Sommer, J. & Gill, K. H. What about value for money? A cost benefit analysis of the South Eastern Sydney Recovery and Wellbeing College. J. Mental Health, 1-8, 10.1080/09638237.2021.1922625 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Morrison, J. D., Becker, H. & Stuifbergen, A. K. Evaluation of Intervention Fidelity in a Multisite Clinical Trial in Persons With Multiple Sclerosis. J. Neurosci. Nurs.49, 344–348, 10.1097/jnn.0000000000000315 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hayes, D. et al. Recovery Colleges Characterisation and Testing in England (RECOLLECT): rationale and protocol. BMC Psychiatry22, 627, 10.1186/s12888-022-04253-y (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Whitley, R., Shepherd, G. & Slade, M. Recovery colleges as a mental health innovation. World Psychiatry18, 141–142, 10.1002/wps.20620 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.King, T. & Meddings, S. Survey identifying commonality across international Recovery Colleges. Ment. Health Soc. Incl.23, 121–128, 10.1108/MHSI-02-2019-0008 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bester, K. L., McGlade, A. & Darragh, E. Is co-production working well in recovery colleges? Emergent themes from a systematic narrative review. J. Ment. Health Train., Educ. Pract.17, 48–60, 10.1108/JMHTEP-05-2021-0046 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lin, E. et al. Evaluating recovery colleges: a co-created scoping review. J. Mental Health, 1–22, 10.1080/09638237.2022.2140788 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Hofstede, G. H. & Hofstede, G. Culture’s consequences: Comparing values, behaviors, institutions and organizations across nations. (Sage, 2001).

- 22.Kotera, Y. et al. Cross-cultural comparison of Recovery College implementation between Japan and England: Corpus-based discourse analysis. Int. J. Mental Health Addiction, 10.1007/s11469-024-01356-3 (2024).

- 23.Kotera, Y. et al. Cross-Cultural Insights from Two Global Mental Health Studies: Self-Enhancement and Ingroup Biases. Int. J. Mental Health Addiction, 10.1007/s11469-024-01307-y (2024).

- 24.Bernal, G., Jiménez-Chafey, M. I. & Domenech Rodríguez, M. M. Cultural adaptation of treatments: A resource for considering culture in evidence-based practice. Professional Psychol.: Res. Pract.40, 361–368, 10.1037/a0016401 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rathod, S. et al. The current status of culturally adapted mental health interventions: a practice-focused review of meta-analyses. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat.14, 165–178, 10.2147/ndt.S138430 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kirmayer, L. J. Culture, Context and Experience in Psychiatric Diagnosis. Psychopathology38, 192–196, 10.1159/000086090 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kirmayer, L. J. Cultural competence and evidence-based practice in mental health: epistemic communities and the politics of pluralism. Soc. Sci. Med75, 249–256, 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.03.018 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.David Wenceslau, L. & Ortega, F. The ‘Cultures’ of Global Mental Health. Theory, Cult. Soc.39, 99–119, 10.1177/02632764211039282 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Arundell, L.-L., Barnett, P., Buckman, J. E. J., Saunders, R. & Pilling, S. The effectiveness of adapted psychological interventions for people from ethnic minority groups: A systematic review and conceptual typology. Clin. Psychol. Rev.88, 102063, 10.1016/j.cpr.2021.102063 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hall, G. C. N., Ibaraki, A. Y., Huang, E. R., Marti, C. N. & Stice, E. A Meta-Analysis of Cultural Adaptations of Psychological Interventions. Behav. Ther.47, 993–1014, 10.1016/j.beth.2016.09.005 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gerlach, P. & Eriksson, K. Measuring Cultural Dimensions: External Validity and Internal Consistency of Hofstede’s VSM 2013 Scales. Front. Psychol.12, 662604, 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.662604 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hofstede, G., Hofstede, G. J. & Minkov, M. Cultures and organizations: Software of the mind. 3rd edn, (McGraw-Hill Education, 2010).

- 33.Ochiai, E. Leaving the West, rejoining the East? Gender and family in Japan’s semi-compressed modernity. Int. Sociol.29, 209–228, 10.1177/0268580914530415 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yamagishi, T. Why has Japan’s “safeness” disappeared?: Challenges of contemporary Japan from the social psychology viewpoint [日本の「安心」はなぜ、消えたのか。社会心理学から見た現代日本の問題点]. (Shueisha, 2008).

- 35.Braithwaite, J., Tran, Y., Ellis, L. A. & Westbrook, J. Inside the black box of comparative national healthcare performance in 35 OECD countries: Issues of culture, systems performance and sustainability. PLOS ONE15, e0239776, 10.1371/journal.pone.0239776 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bhattacharya, R., Roy, S. & Sarma, S. An empirical study of national culture based on Hofstede model and its effect on the inequal distribution of income and wealth. maj55, 94, 10.33516/maj.v55i9.94-99p (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kotera, Y. et al. Typology of Mental Health Peer Support Work Components: Systematised Review and Expert Consultation. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 10.1007/s11469-023-01126-7 (2023).

- 38.Reiter, B. in Government and International Affairs Faculty Publications 99 1-17 (University of South Florida, 2013).

- 39.Gill, K. H. Recovery colleges, co-production in action: The value of the lived experience in “learning and growth for mental health”. Health Issues, 10-14 (2014).

- 40.Markus, H. R. & Kitayama, S. Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychological Rev.98, 224–253, 10.1037/0033-295X.98.2.224 (1991). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kotera, Y., Sheffield, D., Green, P. & Asano, K. in Shame 4.0: Investigating an Emotion in Digital Worlds and the Fourth Industrial Revolution (eds C.-H. Mayer, E. Vanderheiden, & Paul T. P. Wong) 55-71 (Springer International Publishing, 2021).

- 42.Kotera, Y., Van Laethem, M. & Ohshima, R. Cross-cultural comparison of mental health between Japanese and Dutch workers: relationships with mental health shame, self-compassion, work engagement and motivation. Cross Cultural Strategic Manag.27, 511–530, 10.1108/CCSM-02-2020-0055 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kotera, Y., Gilbert, P., Asano, K., Ishimura, I. & Sheffield, D. Self‐criticism and self‐reassurance as mediators between mental health attitudes and symptoms: Attitudes toward mental health problems in Japanese workers. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, ajsp.12355-ajsp.12355, 10.1111/ajsp.12355 (2018).

- 44.Kotera, Y. et al. Qualitative Investigation into the Mental Health of Healthcare Workers in Japan during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health19, 568, 10.3390/ijerph19010568 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hitokoto, H. & Uchida, Y. Interdependent Happiness: Theoretical Importance and Measurement Validity. J. Happiness Stud.16, 211–239, 10.1007/s10902-014-9505-8 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 46.Whitley, R. Ethno-Racial Variation in Recovery From Severe Mental Illness: A Qualitative Comparison. Can. J. Psychiatry61, 340–347, 10.1177/0706743716643740 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kirmayer, L. J. in Textbook of Cultural Psychiatry (eds D. Bhugra & K. Bhui) 1-17 (Cambridge University Press, 2018).

- 48.Kotera, Y. et al. The development of the Japanese version of the full and short form of Attitudes Towards Mental Health Problems Scale (J-(S) ATMHPS). Mental Health, Religion Culture, 10.1080/13674676.2023.2230908 (2023).

- 49.Kotera, Y., Llewellyn-Beardsley, J., Charles, A. & Slade, M. Common Humanity as an Under-acknowledged Mechanism for Mental Health Peer Support. Int. J. Mental Health Addiction, 10.1007/s11469-022-00916-9 (2022).

- 50.Montero-Marin, J. et al. Self-Compassion and Cultural Values: A Cross-Cultural Study of Self-Compassion Using a Multitrait-Multimethod (MTMM) Analytical Procedure. Front. Psychol.9, 2638–2638, 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02638 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kotera, Y., Mayer, C. H. & Vanderheiden, E. Cross-Cultural Comparison of Mental Health Between German and South African Employees: Shame, Self-Compassion, Work Engagement, and Work Motivation. Front. Psychol.12, 2226–2226, 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.627851 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Miyatake, H. et al. Case report on the legal assurance of Advance Care Planning in collective culture. Clin. Case Rep.10, e05759, 10.1002/ccr3.5759 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sittisombut, S., Maxwell, C., Love, E. J. & Sitthi-Amorn, C. Physicians’ attitudes and practices regarding advanced end-of-life care planning for terminally ill patients at Chiang Mai University Hospital, Thailand. Nurs. Health Sci.11, 23–28, 10.1111/j.1442-2018.2008.00416.x (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]