Abstract

Genomic drivers of human-specific neurological traits remain largely undiscovered. Duplicated genes expanded uniquely in the human lineage likely contributed to brain evolution, including the increased complexity of synaptic connections between neurons and the dramatic expansion of the neocortex. Discovering duplicate genes is challenging because the similarity of paralogs makes them prone to sequence-assembly errors. To mitigate this issue, we analyzed a complete telomere-to-telomere human genome sequence (T2T-CHM13) and identified 213 duplicated gene families likely containing human-specific paralogs (>98% identity). Positing that genes important in universal human brain features should exist with at least one copy in all modern humans and exhibit expression in the brain, we narrowed in on 362 paralogs with at least one copy across thousands of ancestrally diverse genomes and present in human brain transcriptomes. Of these, 38 paralogs co-express in gene modules enriched for autism-associated genes and potentially contribute to human language and cognition. We narrowed in on 13 duplicate gene families with human-specific paralogs that are fixed among modern humans and show convincing brain expression patterns. Using long-read DNA sequencing revealed hidden variation across 200 modern humans of diverse ancestries, uncovering signatures of selection not previously identified, including possible balancing selection of CD8B. To understand the roles of duplicated genes in brain development, we generated zebrafish CRISPR “knockout” models of nine orthologs and transiently introduced mRNA-encoding paralogs, effectively “humanizing” the larvae. Morphometric, behavioral, and single-cell RNA-seq screening highlighted, for the first time, a possible role for GPR89B in dosage-mediated brain expansion and FRMPD2B function in altered synaptic signaling, both hallmark features of the human brain. Our holistic approach provides important insights into human brain evolution as well as a resource to the community for studying additional gene expansion drivers of human brain evolution.

Summary

Duplicated genes expanded in the human lineage likely contributed to brain evolution, yet challenges exist in their discovery due to sequence-assembly errors. We used a complete telomere-to-telomere genome sequence to identify 213 human-specific gene families. From these, 362 paralogs were found in all modern human genomes tested and brain transcriptomes, making them top candidates contributing to human-universal brain features. Choosing a subset of paralogs, we used long-read DNA sequencing of hundreds of modern humans to reveal previously hidden signatures of selection. To understand their roles in brain development, we generated zebrafish CRISPR “knockout” models of nine orthologs and introduced mRNA-encoding paralogs, effectively “humanizing” larvae. Our findings implicate two new genes in possibly contributing to hallmark features of the human brain: GPR89B in dosage-mediated brain expansion and FRMPD2B in altered synapse signaling. Our holistic approach provides new insights and a comprehensive resource for studying gene expansion drivers of human brain evolution.

Introduction

Significant phenotypic features distinguish modern humans from closely related great apes1–4. Arguably, one of the most compelling innovations relates to changes in neuroanatomy, including an expanded neocortex and increased complexity of neuronal connections, which allowed the development of novel cognitive features such as reading and language5. While previous work implicated human-specific single-nucleotide variants (SNVs) that impact genes leading to altered brain features, including FOXP26,7 and human-accelerated regions (HARs)8, a majority of top gene candidates are the result of segmental duplications (SDs; genomic regions >1 kbp in length that share high sequence identity [>90%])9–11. SDs can give rise to new gene paralogs with the same function, altered functions, or that antagonize conserved, ancestral paralogs and contribute more to genetic divergence across species than SNVs12. Previous comparisons of great ape genomes have identified >30 human-specific gene families and hundreds of paralogs enriched for genes important in neurodevelopment and residing at genomic hotspots associated with neuropsychiatric disorders13–15. Of these, a handful of genes have been found to function in brain development using model systems, including SRGAP216,17, NOTCH2NL18–20, ARHGAP11B21–23, TBC1D324 CROCCP225, and LRRC37B26. Most studies have leveraged mice to study gene functions although recent studies have expanded to cortical organoids, ferrets, and primates27. Despite their clear importance in contributing to neural features, most duplicate genes remain functionally uncharacterized due to the arduous nature of using such models.

SDs have largely eluded analyses due to difficulties in accurate genome assembly28 and in discovering variants across nearly identical paralogs29–33. As such, many human-duplicated genes are likely left to be discovered. The telomere-to-telomere (T2T) human reference genome T2T-CHM1334, representing a gapless sequence of all autosomes and Chromosome X, has enabled a more complete picture of SDs35 by incorporating 238 Mbp missing from the previous human reference genome (GRCh38). In particular, this new assembly corrects >8 Mbp of collapsed duplications36, including previously missing paralogs of human-specific duplicated gene families13 GPRIN235 and DUSP2236. Here, using this new T2T genome, we identified thousands of recent gene duplications among hominids. By comparing genomic data between great apes and across thousands of modern humans, we narrowed in on a set of paralogs unique within and fixed across modern humans. Transcriptomic datasets from the human brain identified genes most likely to contribute to brain development and function, providing a catalog of the candidate human-specific gene families contributing to brain evolution for further functional testing in model systems. Finally, we prioritized a set of duplicate gene families to characterize in more detail using long-read sequencing and systematic analysis in zebrafish to connect gene functions to brain development.

Results

Genetic analysis of human-duplicated genes

Identification of human gene duplications in T2T-CHM13

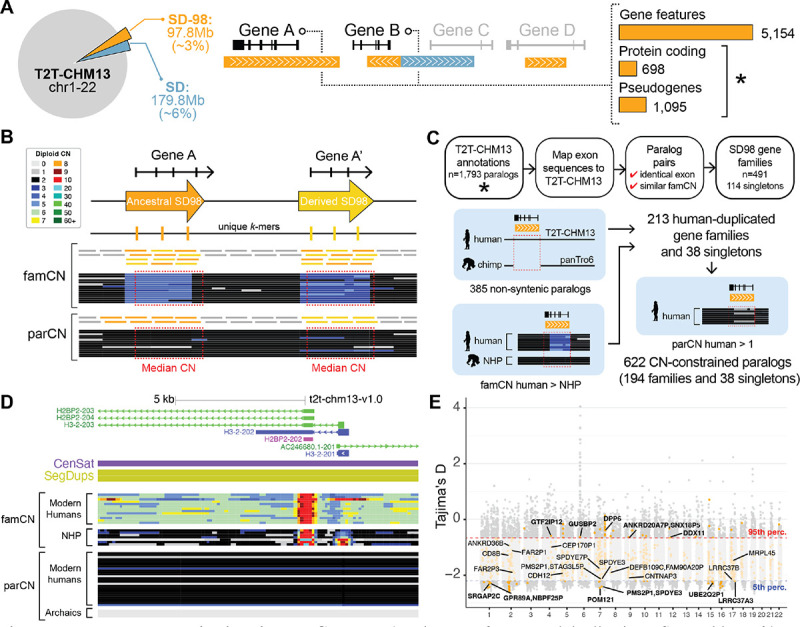

Understanding that highly identical SDs are enriched for human-specific duplications, we narrowed in on 97.8 Mbp of autosomal sequences sharing >98% identity with other genomic regions (or SD98) in the human T2T-CHM1335,37 (Figure 1A). These loci represent genes duplicated only in human lineage13,14 as well as expansions of duplicated gene families present in other great apes. Paralogs in this latter category have experienced recent changes along the Homo lineage in expression (e.g., LRRC37B26) or sequence content (e.g., NOTCH2NL, via interlocus gene conversion18) resulting in new novel functions. Of the 5,154 SD98 genes (Table S1), we focused on 698 protein-encoding genes and 1,095 unprocessed pseudogenes (that could be mis-annotations of true protein-encoding genes38). This list includes well-known duplicated genes important in neurodevelopment (SRGAP2C, ARHGAP11B), disease (SMN1 and SMN239, KANSL140), and adaptation (e.g., amylase genes41–43). Sequence read depth35 in modern humans (Simons Genome Diversity Project [SGDP], n=26944) verified that all paralogs had >2 gene-family diploid copy number (famCN; Methods) (Table S2, Figure 1B).

Figure 1. Human gene duplications in T2T-CHM13.

(A) Diagram of segmental duplications (SDs) with >90% identity (blue) and >98% identity (orange) in T2T-CHM13 and selection of genes within SDs with >98% identity (SD98 genes). Total counts are shown on the right, with protein-encoding genes and pseudogenes used for further analysis indicated with an asterisk. (B) Schematic representation of copy number (CN) estimation methods, including gene-family CN (famCN) and paralog-specific CN (parCN). Illustrated horizontal lines represent short-read pileups mapping to unique (gray) and duplicated regions (orange and yellow). Read-depth diploid CN estimates are shown as heatmaps with values explained in the legend (left). The CN-genotyping window is shown as red dashed boxes. (C) Pipeline for clustering and stratification of SD98 genes. Gene families were classified as carrying human duplicates based on synteny with the chimpanzee reference genome (panTro6) and famCN comparisons between human and nonhuman primates (NHPs) (left). CN-constrained (fixed or nearly fixed) genes were flagged based on parCN values across human populations (right). (D) UCSC Genome Browser snapshot of the H3–2/H2BP2 locus, including gene models, centromeric satellites (CenSat), SDs (SegDup), and famCN and parCN predictions across modern humans, NHPs, and archaic genomes. (E) Distribution of Tajima’s D values (y-axis) from individuals of African ancestry from the 1KGP across 25-kbp windows genome wide (gray) and in the SD98 region (orange) across human autosomal chromosomes (x-axis). All human-duplicated gene names with outlier D values in African, European, East Asian, South Asian, and American populations are included.

Based on sequence and famCN similarity, we clustered the 1,679 paralogs into 491 multigene families (Figure 1C, Figure S1), with most families having 2–3 members (n=271) (Figure S2). Three extreme high-copy gene families had >50 paralogs, including macrosatellite-associated DUX4 and DUB/USP17 as well as primate-specific FAM90A45. The remaining 114 paralogs were defined as singletons (Table S2), with some failing to cluster due to high and variable copy numbers (CNs) (e.g., CROCC and CROCCP2) or only a small portion of the gene duplicated (e.g., AIDA and LUZP2). Within 163 multigene families and 13 singletons, we identified 385 human-specific paralogs within non-syntenic regions present in human but not chimpanzee reference assemblies35 (Figure 1C, Table S2). Several previously known human-specific genes were notably absent from this list (e.g., NPY4R2, ROCKP1, and SERF1B13) because genome alignments across SDs can be imprecise. We next identified human-expanded gene families as those with higher famCN in humans (SDGP, n=269) versus nonhuman great apes (n=4) (97 gene families and 27 singletons; Figure 1C, Table S3), excluding high-copy genes that were difficult to accurately detect CN differences (famCN>10). In total, we conservatively predict 213 gene families and 38 singletons comprising at least one human-specific duplicate paralog (Table S3).

Variation of duplicated genes in modern humans

Positing that all humans should carry a functional version of a gene if important for a species-universal trait, we used k-mer-based paralog-specific copy number (parCN) estimates46 to identify 622 genes (194 duplicate families, 38 singletons) with at least one copy in >98% of humans (“CN constrained”, parCN≥0.5; 1000 Genomes Project, 1KGP; n=2,504) (Tables S1 and S4). Of these, 125 paralogs were “fixed” in humans (parCN~2) and likely represent Homo sapiens-specific genes. We found 13 CN constrained genes that were largely absent (parCN<0.5) from four archaic human genomes47–49. One of these genes, H3–2/H2BP2, is a member of a core H2B histone family involved in the structure of eukaryotic chromatin50, homologous with another human-specific H2BP1 and the ancestral H2BC18 paralog (Figure 1D). Another Homo sapiens-specific gene, FCGR1CP, encodes an immunoglobulin gamma Fc Gamma Receptor, a family of proteins vital in regulating immune response51. Moving forward, we consider only duplicate gene families comprising CN-constrained genes.

We identified 13 protein-encoding genes as loss-of-function intolerant (pLI ≥0.9 or LOEUF ≤0.35) using SNV data from hundreds of thousands of humans from gnomAD52 (Table S1, Figure S3), showing that deleterious mutations of these genes are depleted in human populations (e.g., likely not compatible with life). These conserved genes are all ancestral paralogs, including NOTCH2, HERC2, and CORO1A. The gnomAD (v3) metrics rely on variants identified in protein-encoding genes using the human reference genome hg19, which has known errors across SDs53 and misannotated pseudogenes. As such, all unprocessed pseudogenes and 32% of protein-encoding SD98 genes lacked gnomAD pLI and LOEUF scores. To circumvent these issues, we assessed SNV genetic diversity by Tajima’s D54 using the T2T-CHM13 reference and the 1KGP cohort36,55. Focusing on short-read accessible regions (Figure S4, Note S1), we identified 15 CN-constrained human-duplicated genes with extreme negative D values (<5th percentile of the genome-wide empirical distribution) considered signatures of positive or purifying selection (Figures 1E and S5). These included human-specific paralog SRGAP2C previously implicated in cortical neuronal migration and synaptogenesis16,17 as well as the uncharacterized LRRC37A3 and the hominid-specific LRRC37B, recently found to function in cortical pyramidal neurons by impacting synaptic excitability26. We also identified nine genes exhibiting extremely positive D values (>95th percentile) as putative signatures of balancing selection, including T-cell antigen CD8B. Collectively, variants discovered using the new T2T-CHM13 genome enabled the identification of new and interesting human-duplicated genes potentially contributing to traits and diseases not previously assayed in genome-wide selection screens.

Human-duplicated genes implicated in brain development

Connecting genetic variation of duplicated genes with neural traits

To narrow in on human-duplicate gene families contributing to neurocognitive features, we identified 187 genes with putative associations with brain-related phenotypes from the genome-wide association study (GWAS) catalog and UK Biobank56 (Tables S1 and S4). Three variants (rs12725078, rs17537178 and rs4797876) associated with sulcal depth impact SRGAP2, PTPN20, and ROCK1P1, respectively. The ancestral CORO1A, implicated in autism57, is associated with brain morphology. Many implicated genes reside at genomic hotspots (n=58), such as GPR89 paralogs at chromosome 1q21.1 with recurrent ~2 Mbp deletions/duplications impacting brain size58. While interesting, GWAS hits are significantly depleted across SD98 regions (Note S2), in part due to the common use of single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) arrays that lack coverage across SDs59. As such, we assayed variation in an autism cohort (Simons Simplex Collection [SSC]; n=2,459 quad families). Eighteen genes show significant parCN differences in probands versus unaffected siblings (Wilcoxon signed-rank test, q-value<0.05) (Figure S6), with all but one residing at chromosome 15q25.2 (OMIM: 614294), a region known to undergo recurrent deletions/duplications60. The remaining gene, pseudogene AC233280.19, is associated with the chromosome 3q29 genomic disorder (OMIM: 609425). De novo copy number variants (CNVs) impact 22 human-duplicated genes in autistic probands (Table S6, Figure S7); this contrasts with six events impacting five paralogs in unaffected siblings (Fisher’s exact test, p-value = 4.5×10−4). Most impacted genes reside at known autism-associated genomic hotspots (n=15). The other seven, which were not mutated in unaffected siblings, included protein-encoding genes CD8B2, FCGR1B, HYDIN and LIMS1, representing possible contributors to autism spectrum disorder (ASD).

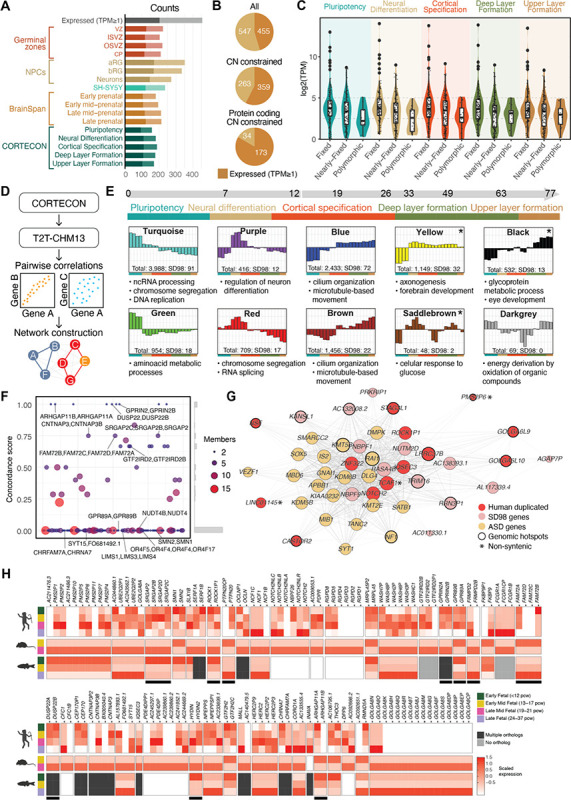

Duplicated gene expression in the developing human brain

Re-analyzing published RNA-seq datasets21,61–64 using the new T2T-CHM13 reference, we found nearly half of human-duplicated gene paralogs (455/1,002) are expressed during brain development (TPM≥1) (Table S1, Figures 2A and S8), representing a depletion versus the genome-wide transcriptome (21,513/23,395). This increases to 58% for CN-constrained genes (1.3-fold enrichment, p-value = 2.5×10−24, hypergeometric test) and to 84% for CN-constrained protein-encoding genes (1.4-fold enrichment, p-value = 7.8×10−30, hypergeometric test) (Figure 2B). These results suggest true functional candidates are more likely to exist in the most CN-constrained protein-encoding genes (Figure 2C). In sum, 147 human-duplicated families carry at least one CN-constrained and brain-expressed gene, including 39 protein-encoding paralogs verified as human specific (non-syntenic). Of these, 21 genes are also expressed in the postnatal brain, including CD8B2, which is exclusively expressed after birth.

Figure 2. Expression of human-duplicated genes during brain development.

(A) Counts of human-duplicated genes with transcripts per million (TPM) >1 in fetal brain datasets including germinal zones (VZ: ventricular zone, ISVZ: inner subventricular zone, OSVZ: outer subventricular zone, CP: cortical plate), neuronal progenitor cells (NPCs) (aRGs: apical radial glia, bRGs: basal radial glia), neuroblastoma cell line (SH-SY5Y), the BrainSpan dataset, and the CORTECON dataset. Counts for protein-encoding genes are represented in darker shades. (B) counts of expressed (TPM≥1) (dark orange) and non-expressed (light orange) human-duplicated genes across gene categories. (C) SD98 gene expression in log2(TPM) in the CORTECON dataset, spanning pluripotency to upper layer formation and stratified by copy number (CN) category. (D) Pipeline used for the weighted gene coexpression analysis (WGCNA) of CORTECON data remapped to the T2T-CHM13 reference. (E) Selected WGCNA coexpression modules represented with random colors. Modules were organized based on their temporal expression spanning pluripotency to upper layer formation (day 0 to 77) with overrepresented gene ontology terms shown at the bottom. (F) Module assignment concordance scores are shown on the vertical axis for SD98 gene families, with spacing along the horizontal axis for visual separation. The size of each point corresponds to the number of members in the respective gene family. (G) Network diagram of yellow module. Only genes within human-duplicated gene families (red) or SD98 (pink) and autism-associated (yellow) categories with high module membership are depicted. Genes with asterisks are non-syntenic with chimpanzee35 and bold borders are within ±500-kbp of a genomic disorder hotspot60. (H) Scaled TPMs from post-mortem human fetal brain samples from the BrainSpan dataset, and pseudo-bulk single-cell transcriptomes from whole-brain dissected samples of mouse and zebrafish. Gene families pictured represent a subset of CN-constrained and brain-expressed human-duplicated gene families. Genes with black bars beneath them were prioritized for additional characterization.

We next used the longitudinal CORTECON dataset63, with transcriptomes of different stages of ex-vivo-induced neurogenesis from human embryonic stem cells, to infer developmental functions of genes using weighted gene co-expression network analysis (WGCNA)65 (Figure 2D). Expressed genes (n=15,695) were clustered into 37 co-expression modules, each assigned a random color identifier. Thirty-two modules comprised SD98 genes (n=399), of which 200 paralogs represented human-duplicated families (55 non-syntenic) (Table S7, Figures 2E and S9). Comparing module assignment between paralogs found mostly differential expression patterns, with only six duplicate gene families in complete concordance (i.e., all paralogs in the same module) (Table S8, Figure 2F). This suggests that our approach largely distinguishes transcriptional profiles between similar paralogs, and that expression diverges at relatively short evolutionary time scales (<6 million years), as we have shown for a smaller set of genes66.

Twenty-two of 35 modules were enriched for functional gene ontology (GO) terms (q-value<0.05, hypergeometric test; Table S9, Figures 2E and S9). To verify module assignments, we searched for duplicated genes with characterized functions. ARHGAP11B, which induces cortical neural progenitor amplification by altering glutaminolysis in the mitochondria23, is a member of turquoise. Genes in this module are expressed highest during pluripotency and are associated with cell proliferation, including DNA replication and chromosome segregation, as well as mitochondrial gene expression. The hominoid-specific gene TBC1D3, known to promote basal progenitor amplification in the outer radial glia resulting in cortical folding in mice24 is a member of purple, a module associated with regulation of neural differentiation. Human-specific SRGAP2C, which interacts with F-actin to produce membrane protrusions required for neuronal migration67, represents blue with co-expressed genes that peak during cortical specification and upper-layer formation. This module is associated with cell motility, including motile cilium organization and assembly and microtubule-based movement.

We also found autism-associated genes57 significantly enriched in four modules (yellow, black, saddle brown, and cyan), as well as the “unassigned” module (grey) (q-value < 0.05, hypergeometric test), and included 38 paralogs from human-duplicated gene families. Remarkably, three protein-encoding paralogs from the RGPD gene family, encoding RANBP2 Like And GRIP Domain Containing proteins, were represented in these modules, including human-specific RGPD3 (yellow) and RGPD4 (grey) as well as RGPD8 (saddle brown). The yellow module, enriched with functions in axon guidance and synaptogenesis, contains the most autism-associated genes (n=20) (Table S7, Figure 2G). Genes in this module exhibit low expression during pluripotency, followed by sustained expression from neural differentiation to deep layer formation, including several markers of glutamatergic neurons (e.g., SOX5, SLC1A6, OTX1, and TLE4)68. Human-duplicate paralogs in the yellow module include LRRC37B, important in synapse function, as well as the causal gene in the chromosome 17q21.31 microdeletion syndrome, KANSL169. We also identified compelling candidates residing at autism-associated genomic hotspots (e.g., GOLGA6L9 and GOLGA6L10 in chromosome 15q25.2, and CASTOR2, PMS2P6 and STAG3L1 in chromosome 7q11.23) (Table S1). Collectively, duplicated genes co-expressed with neural and ASD-associated genes representing top candidates contributing to human brain development.

Modeling functions of duplicated genes in brain development

The next step in understanding the role of human-duplicated genes in brain development is to test their functions in model systems. Our combined analysis highlights 148 gene families with at least one CN-constrained or brain-expressed human-duplicated paralog, in addition to 30 paralogs not assigned to a family (Table S10). Of these, we found 106 with a homologous gene(s) in either mouse or zebrafish. Using matched brain-expression data from these species corresponding to human developmental stages64,70,71 (Figure S10, as previously described72,73) narrowed in on 76 and 41 single-copy orthologs expressed during neurodevelopment in mice and zebrafish, respectively (Table S11), representing top candidates for functional studies. This leaves 40% of the human duplicate families with no obvious mouse/zebrafish ortholog, including fusion genes, primate-specific genes (e.g., TBC1D3 paralogs24,74), or those associated with great ape ancestral “core” duplicons (e.g., NBPF and NPIP)75. Alternative models are required, such as in vivo primate or cell culture organoids, to test the functions of these genes.

Application of the resource: Characterizing candidate duplicated genes

Genetic variation of candidate genes important in neurodevelopment

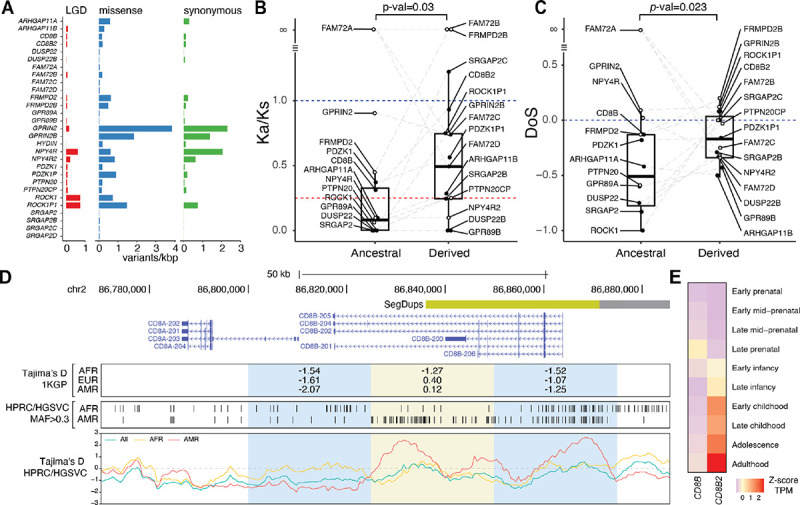

As a proof of concept, we selected 13 priority human-specific duplicated (pHSD) gene families representing 30 paralogs from our model gene list (Table S12). Since none of the paralogs fully reside within short-read-accessible genomic regions due to their high identity (Table S1), we characterized variation using long-read sequencing. This included published draft assemblies of 47 individuals from the Human Pangenome Reference Consortium (HPRC)76–78 and nine individuals from the Human Genome Structural Variation Consortium (HGSVC)79 (112 total haplotypes; Figure S11). We also performed capture high-fidelity (cHiFi) sequencing on 178 individuals of diverse ancestries in the extended 1KGP cohort55 and 22 individuals from the Human Genome Diversity Project (HGDP)80 (Table S13, Figure S12, Note S3). Combined, we identified 46,754 variants (33,774 SNVs and 12,980 indels), or 12.7 variants/kbp, across captured regions (Table S14). Levels of variation within gene families were largely different between paralogs (Mann-Whitney U test, p≤0.05), with the exception of FRMPD2 and PTPN20 (Figure S13). For instance, compared with the ancestral SRGAP2 paralog, human-specific SRGAP2B exhibited the lowest and SRGAP2C the highest heterozygosity levels, in line with different mutation rates previously observed at each loci17.

Functional annotation81 identified 412 gene-impacting variants (missense = 252, synonymous = 131, likely gene-disruptive [LGD] = 29; Tables S15 and S16, Figure 3A), with eleven paralogs exhibiting no LGD variants suggesting strong selective constraint. To infer purifying selection, an indicator of function, we calculated the Ka/Ks statistic (also known as dN/dS) per gene family (Table S17). Virtually all paralogs had Ka/Ks lower than 1, and seven ancestral and three derived paralogs exhibited Ka/Ks below the genome-wide average (~0.25)82. The ancestral paralogs (Table S12) exhibited significantly lower Ka/Ks values than their derived paralogs (Wilcoxon signed-rank test, p-value=0.03) (Figure 3B), consistent with stronger purifying selection. To test for more recent selection signatures, we incorporated polymorphic variation to calculate pN/pS and the direction of selection (DoS) statistic83, which similarly indicated stronger purifying selection in the ancestral versus derived paralogs (Wilcoxon signed-rank test, p-value=0.023) (Table S17, Figure 3C). While the tests mostly agree, NPY4R shows discordant signatures, being highly conserved according to Ka/Ks but approaching zero in DoS, in line with an excess of observed LGD variants suggesting recent neutral evolution. Most paralogs within gene families were under purifying selection, including GPR89, CD8B, DUSP22, GPRIN2, and ARHGAP11 (also evident from a larger phylogenetic analysis of dN/dS using a maximum likelihood approach84; Table S18), although some show conservation in only one paralog, such as ROCK1. Human-specific SRGAP2C has elevated Ka/Ks and pN/pS, together with low Tajima’s D (−2.32) in African individuals from the 1KGP genome-wide screen (Figure 1E), suggesting SRGAP2C is evolving under positive selection.

Figure 3. Genetic variation and signatures of selection of priority human-specific duplicated (pHSD) genes.

(A) Number of likely gene-disruptive (LGD) (red), missense (blue), and synonymous (green) mutations identified in pHSD genes using long-read assemblies (n=56) and PacBio capture high-fidelity (cHiFi) sequencing (n=144). (B) Ka/Ks values calculated from human and chimpanzee sequences. Red dashed line indicates the average genome-wide Ka/Ks between humans and chimpanzees. Blue line indicates neutrality in the Ka/Ks test. Differences between the Ka/Ks of the matched ancestral and derived paralogs were tested with the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. (C) Direction of selection (DoS) values derived from Ka/Ks and pN/pS estimates. Blue line indicates the threshold for signatures of positive selection (positive values). Significant differences between ancestral and derived paralogs were obtained with the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. Paralogs with infinite values or undetermined ancestral/derived state (hollow dots) were excluded from Ka/Ks and DoS comparisons. (D) CD8B locus overview, including Tajima’s D values derived from 1KGP SNVs in 25-kbp windows, biallelic SNPs with a minor allele frequency greater than 0.3 identified in African (AFR, n=27) and American (AMR, n=18) individuals using continuous assemblies from the Human Pangenome Reference Consortium (HPRC) and the Human Genome Structural Variation Consortium (HGSVC), and Tajima’s D values derived from HPRC and HGSVC SNVs using 6-kbp windows and 500-bp steps for AFR, AMR, and all individuals. (E) Scaled transcript per million (TPM) expression of CD8B and CD8B2 in postmortem brain tissue from BrainSpan.

We verified selection signatures of pHSDs using high-confidence variants obtained from genome assemblies (n=56, HPRC/HGSVC) using nucleotide diversity π and Tajima’s D. SRGAP2C again shows negative Tajima’s D (−2.14) in AFR, validating genome-wide results (Figure S14). GPR89 gene family paralogs, with low Ka/Ks, exhibit low nucleotide diversity and negative Tajima’s D values across all exons consistent with functional constraints (Figure S15). In contrast, ROCK1 showed reduced nucleotide diversity and more negative Tajima’s D compared to ROCK1P1, consistent with their Ka/Ks values (Figure S16). While Ka/Ks was not calculated for FAM72 paralogs due to a lack of synonymous polymorphisms, Tajima’s D values similarly ranged from −2 to −1 indicating conservation of the gene family members (Figure S17).

Revisiting the 1KGP genome-wide signal of balancing selection in individuals of American (Tajima’s D=0.12) and European ancestries (D=0.40) centered on CD8B (Tables S1 and S5, Figures 1E, 3D and S5), we find positive Tajima’s D in American (max 2.66, n=18) but not in African ancestries (max 0.62, n=27) with three major peaks within the gene (Figure 3D). The ancestral CD8B paralog, encoding CD8 Subunit Beta, is highly expressed in T cells where the protein dimerizes with itself or CD8A (alpha) to serve as a cell-surface glycoprotein mediating cell-cell interactions and immune response85,86. Leveraging the assemblies, we identified two distinct haplotype clusters underlying the Tajima’s D peaks, one of them particularly prevalent in individuals of American ancestry (Figure S18). Expanding to the entire long-read dataset (including cHiFi) shows an increase in intermediate-frequency variants, a signature of balancing selection, in CD8B among European and American ancestries, compared with those of African ancestry (Kolmogorov-Smirnov, p-value=2.2×10−16) (Figure S19); these variants were verified as differentiating the two main haplotypes. Two of the SNPs (rs56063487 and rs6547706) are CD8B splice eQTLs in whole blood from GTEx87 and significantly associated with increased CD8-protein levels on CD8+ T cells within a Sardinian cohort88. We note that CD8B2 paralog-specific variants do not overlap with the SNPs, providing confidence in these short-read-based genotype results. The haplotypes may, thus, play a role in the modulation of the adaptive immune response, a frequent target of balancing selection. Alternatively, the human-specific paralog CD8B2 exhibits divergent expression in the human postnatal brain rather than in T cells38 (Figure 3E). These results provide an example of two paralogs with likely divergent functions and contrasting evolutionary pressures over a relatively short evolutionary time span (~5.2 million years ago [mya]13). Combined, we demonstrate the efficacy of long-read data to uncover hidden signatures of natural selection.

Duplicated gene functions modeled using zebrafish

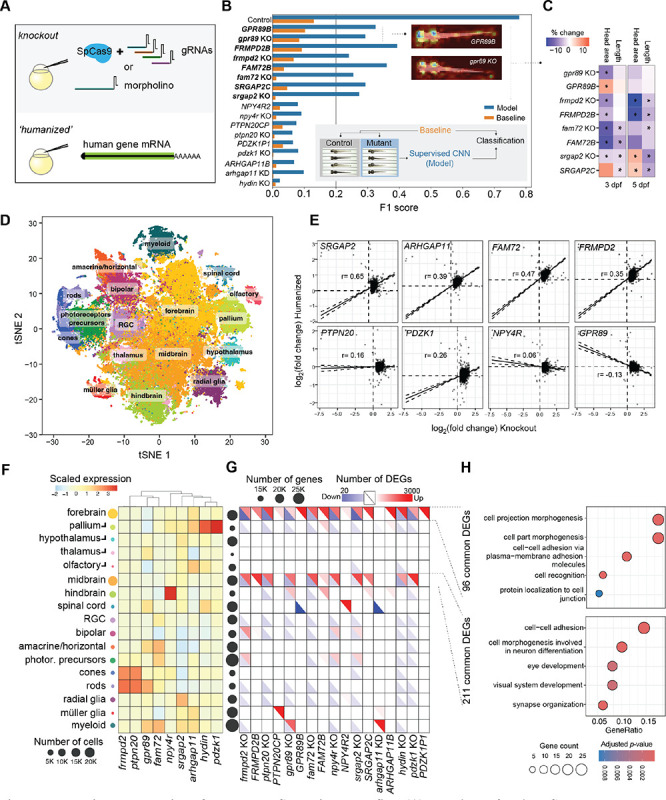

We performed a high-throughput functional screen in zebrafish89–91 of seven largely uncharacterized pHSD families expressed in both human and zebrafish brain (GPR89, NPY4R, PTPN20, PDZK1, HYDIN, FRMPD2, and FAM72; Figure 2H and Table S11). Additionally, we tested two gene families (SRGAP2 and ARHGAP11) previously studied in mammals16,21–23,67,92–96. Ancestral gene functions were assessed using loss-of-function knockouts for eight zebrafish orthologs by co-injecting SpCas9 coupled with four guide RNAs (gRNAs) targeting early exons resulting in ~70% ablation of alleles in G0 lines97 (termed crispants). The final gene, arhgap11, is maternally expressed (Figure S20) prompting us to use a morpholino that impedes translation. We also ‘humanized’ zebrafish models by introducing transiently in vitro transcribed 5’-capped mRNAs encoding human-specific paralogs (Figure 4A) for all genes except HYDIN2, due to its large size (4,797 amino acids). There were no significant morbidity differences in mutants compared to controls (log-rank survival tests p-values > 0.05, Table S19).

Figure 4. Functional evaluation of selected pHSDs using zebrafish.

(A) Functions of each pHSD gene were tested by generating knockout (co-injection of SpCas9 coupled with four gRNAs targeting early exons, or morpholino for arhgap11) and ‘humanized’ models (injection of the human-specific mRNA). (B) Morphological assessment using a supervised convolutional neural network (CNN) to distinguish models from matched controls (bottom inset) obtained at 3 dpf and 5 dpf. F1 score indicates the effect size of difference between models and controls and ranges from 0 to 1, where 0 indicates that no sample from that group could be distinguished from the controls. Orange bars indicate the null hypothesis that there is no difference between models and controls. A threshold F1 score of 0.2 was used to define pHSD groups being robustly classified as different from their control group. Pictured as a top inset are feature attribution plots for two example GPR89B and gpr89 knockout larvae, highlighting the region of the image used by the CNN to correctly classify and distinguish those genotypes from controls. Colors range from red (region is not used for classification; zero gradient), to orange, then blue (region contributes the most to classification; large magnitude gradient). (C) Percent change compared to the control group for standard length or head area across selected pHSD models. Asterisks indicate a Benjamini Hochberg-corrected p-value below 0.05. (D) t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (tSNE) plot highlighting the classified 17 cell types from the 95,555 harvested cells across pHSD models at 3 dpf. (E) Fold-change comparison between knockout and ‘humanized’ models for each pHSD across all genes (n= 29,945), versus their controls. Black lines represent the Pearson correlation line and the dotted lines the 95% confidence intervals. (F) Endogenous z-score scaled expression of each zebrafish ortholog across defined scRNA-seq cell types. Circle sizes scale with the overall number of cells included in that group. (G) Distribution of cell-type-specific differentially expressed genes (DEGs) for each pHSD model. Each square includes the downregulated genes in blue (lower diagonal) and upregulated genes in red (upper diagonal). Circles next to each cell type represent the number of expressed genes. (H) Gene ontology results for the common DEGs in forebrain (n= 96) and midbrain (n=211) across pHSD models, with circles representing DEG number in the GO term and color representing the q-value.

To assay morphology differences in mutant zebrafish, we acquired images98–100 for 3,146 larvae at 3 and 5 days post-fertilization (dpf) (average of 75±55 larvae per group, Table S20). We first used latent diffusion and convolutional neural networks (CNNs) to test for significant morphological alterations between mutant models and controls without predefining specific features a priori (Methods). Both knockout and humanized models of SRGAP2, GPR89, FRMPD2, and FAM72 exhibited significant differences (F1 scores > 0.2, Figure 4B). Altered features were identified by quantifying body length, head area, and the head-trunk angle, a classic measurement for developmental staging of zebrafish using the same images. This revealed concordant phenotypes for knockout and humanized models of SRGAP2 (reduced length), and FRMPD2 (reduced head area), and FAM72 (both reduced body length and head area) at 3 dpf (Table S21, Figure 4C). Alternatively, GPR89 models exhibited opposing effects, with head area for gpr89 knockout larvae ~10% reduced and GPR89B ‘humanized’ larvae ~15% increased. This is also evident in the feature attribution plot indicating that the CNN distinguishes both gpr89 knockout and GPR89B humanized larvae from controls primarily by focusing on the head (Figure 4B). At 5 dpf, the alterations in FRMPD2 and SRGAP2 models persisted while no longer observed for FAM72 and GPR89 (Table S21, Figure 4C). Knockout models for gpr89 and frmpd2 also displayed evidence of developmental delay with subtle yet significant decreases in the head-trunk angle (Table S21).

We next performed single-cell RNA-sequencing (scRNA-seq)101,102 of dissected heads of 3 dpf larvae to directly characterize impacts on brain development, profiling 95,555 cells (an average of 3,822±3,227 per model) (Figure 4D). Pseudo-bulk differential expression analysis using all cells in each model revealed significant correlations in gene expression changes versus controls between knockout and humanized models (Figure 4E). Positive correlations for SRGAP2C, FAM72B, ARHGAP11B, FRMPD2B, and PDZK1B humanized larvae with respect to each knockout indicate loss-of-function effects. GPR89B gene expression changes are negatively correlated with gpr89 indicating gene dosage effects, while PTPN20CP and NPY4R2 show low/no relationship between models. These results are in line with our morphometric findings for SRGAP2, FRMPD2, FAM72, and GPR89 (Figure 4C), as well as from our separate study103 that verified the human SRGAP2C protein physically interacts with and antagonizes zebrafish Srgap2.

We classified 17 different neuronal, retinal, and glial cell types using gene markers71,101,104,105. While most pHSD orthologs were broadly expressed across cells, a subset showed more narrow expression in specific cell types (e.g., hydin and pdzk1 in the pallium, npy4r in the hindbrain; Figure 4F). We repeated pseudo-bulk differential expression analyses across specific cell types revealing gene dysregulation in the forebrain and midbrain across most pHSD models (16 out of 17, Figure 4G). Common differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in the forebrain functioned in cell projection, adhesion, and recognition, while DEGs in the midbrain related to neuronal differentiation and the visual system (Figure 4H). The zebrafish forebrain is the closest related structure to the human cerebral cortex106, while the midbrain primarily includes the optic tectum107, the main visual processing center. Some models also highlighted DEGs in specific cell types, including Müller glia in humanized PTPN20CP, the spinal cord in humanized NPY4R2, and myeloid cells in gpr89 and arhgap11 knockout larvae (Figure 4G). Combined, these results indicate that all tested pHSD models impact the developing zebrafish brain, suggesting that they may also play important roles in human brain evolution.

Novel human-specific genes impacting neurodevelopment

GPR89B and brain size

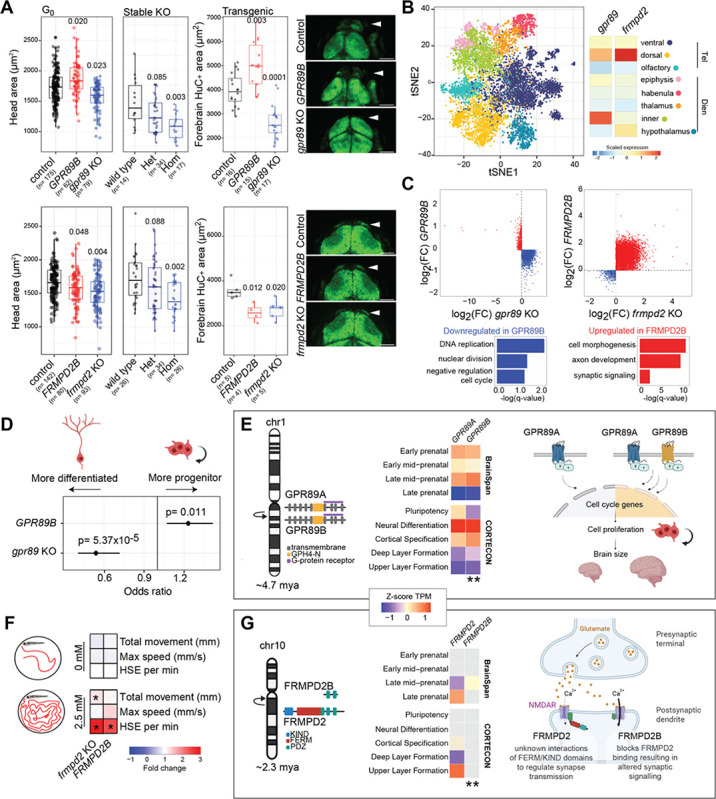

Opposite phenotypes were observed for gpr89 knockout and humanized GPR89B zebrafish suggesting gene dosage effects. Considering both GPR89 human paralogs are impacted by deletions and duplications at the chromosome 1q21.1 genomic hotspot associated with microcephaly and macrocephaly in children with neurocognitive disabilities, respectively58, we sought to characterize mechanisms underlying larval head-size phenotypes in more detail. We first verified that stable gpr89 heterozygous and homozygous knockouts exhibited reduced head size at 3 dpf, consistent with crispants. Using a neuronal reporter line Tg(HuC-eGFP)108, we generated GPR89 mutant models finding significantly smaller and larger forebrains in knockout and humanized larvae, respectively (Figures 5A). Re-examining scRNA-seq data, we sub-clustered cells from the forebrain and observed endogenous expression of gpr89 in telencephalon and inner diencephalon (Figure 5B). Focusing on the telencephalon, a brain structure anatomically equivalent to the mammalian forebrain with roles in higher cognitive functions such as social behavior and associative learning109,110, we performed pseudo-bulk differential expression analysis. DEGs with inverse effects were enriched in negative regulation of the DNA replication and cell cycle (Figure 5C, Tables S22 and S23). Several genes functioning at the G2/M checkpoint were downregulated in the humanized GPR89B and upregulated in the knockout gpr89 pointing to differences in cell proliferation. To test this, we estimated the identity of forebrain cells based on the expression of known markers for neural progenitors (sox19a, sox2, rpl5a, npm1a, s100b, dla) and differentiated neurons (elavl3, elavl4, tubb5). This found humanized GPR89B cells more likely to classify as progenitors while gpr89 knockouts more likely to be differentiated (Figure 5D).

Figure 5. Neurodevelopmental impact of GPR89 and FRMPD2.

(A) Head and brain area assessments at 3 dpf for G0 crispants and stable knockout lines for GPR89 (top) and FRMPD2 (bottom) models. Results for head area of GPR89 crispants (ANOVA p-values: controls vs. GPR89B= 0.020, controls vs. gpr89 knockouts= 0.023) and stable knockout lines (Wilcoxon signed-rank tests p-values: controls vs. Het= 0.085, controls vs. Hom= 0.003), as well as forebrain area of crispants using a transgenic line with fluorescently tagged neurons (ANOVA p-values: controls vs. GPR89B= 0.003, controls vs. gpr89 knockouts= 0.0001). Results for head area of FRMPD2 crispants (ANCOVA p-values: controls vs. FRMPD2B= 0.048, controls vs. gpr89 knockouts= 0.004) and stable knockout lines (Wilcoxon signed-rank tests p-values: controls vs. Het= 0.088, controls vs. Hom= 0.002), as well as forebrain area of crispants using a transgenic line with fluorescently tagged neurons (ANOVA p-values: controls vs. FRMPD2B= 0.012, controls vs. frmpd2 knockouts= 0.020). Representative images of each model in the neuronal transgenic line are included with scale bars representing 100 μm. (B) t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (tSNE) plot showing the identified subregions classified from the forebrain (n=10,040 cells) and relative scaled endogenous expression of gpr89 and frmpd2 across cell types. (C) Log2 fold change (FC) of gene expression versus controls in cells from the telencephalon between knockout and humanized models in GPR89 and FRMPD2. Red and blue colors correspond to DEGs discordant (GPR89) or concordant (FRMPD2) between the knockout and humanized models and their top representative gene ontology enrichment analyses results. (D) Forest plot with the results from the logistic regression for presence of progenitor versus differentiated states in forebrain cells across GPR89 models. (E) Diagram of the duplication event of GPR89 giving rise to GPR89A and GPR89B, encoding two identical proteins with different expression patterns in both neurodevelopmental timing (BrainSpan) and brain regions (CORTECON) (**Wilcoxon signed-rank test, p-value < 0.005). A model of GPR89B gain-of-function in neuronal proliferation amplification is depicted on the right. (F) Behavioral results from 1 h motion-tracking evaluations in 4 dpf larvae exposed (2.5 mM) or not (0 mM) to pentylenetetrazol (PTZ). Metrics compared included total movement (mm), maximum speed (mm/s), and frequency of high-speed events (≥28 mm/s). Colors represent the fold change relative to the control group and the asterisk indicates a significant Dunn’s test (BH-adjusted p<0.05). (G) Diagram of the duplication event of FRMPD2 ~2.3 mya that gave rise to the 5’-truncated FRMPD2B, which exhibits different temporal (BrainSpan) and spatial (CORTECON) expression patterns (**Wilcoxon signed-rank test, p-value < 0.005). A model of FRMPD2B antagonistic functions resulting in altered synaptic signaling is depicted on the right.

GPR89 (G-protein receptor 89 or GPHR, Golgi PH regulator) encodes highly conserved transmembrane proteins that participate in intracellular pH regulation in the Golgi apparatus111. Loss of function in Drosophila leads to global growth deficiencies as a result of defects in the secretory pathway112. In humans, a complete duplication of ancestral GPR89A ~4.7 mya produced the derived, full-length GPR89B13 (Figure 5E). The two paralogs maintain identical protein similarity but differential and overlapping expression patterns in human brain development, with GPR89A highly expressed starting in pluripotency (turquoise module), and GPR89B expression turning on slightly later during neural differentiation (red module; Figures 2E and 5E). Both genes are under purifying selection (Figure S14), with GPR89A exhibiting extreme negative Tajima’s D values in individuals of AFR and AMR ancestries from the 1KGP cohort (<5th percentile; Figure 1E, Table S1). These results provide evidence that both GPR89 paralogs function in early brain development, possibly with delayed expression of GPR89B extending expansion of progenitor cells, a feature observed in human cerebral organoids compared with those of other apes113,114 (Figure 5E). Together with the increase in forebrain size of “humanized” zebrafish, this suggests a role for GPR89B in contributing to the human-lineage expansion of the neocortex.

FRMPD2B and synaptic signaling

While opposing traits were observed in GPR89 models, similar phenotypes impacting head area and body length suggest that the human FRMPD2B acts as a dominant negative to the endogenous Frmpd2. Validating phenotypes observed in crispants (Figure 4C), we observed reduced head size in stable frmpd2 homozygous knockout larvae (Figure 5A). Additionally, both the crispant knockout frmpd2 and humanized FRMPD2B larvae exhibit smaller forebrains. We found that shared upregulated DEGs function in cell/axon morphogenesis and growth as well as synaptic signaling in telencephalic cells (Figure 5C, Tables S24 and S25). To better characterize impacts on synaptic signaling, we used motion-tracking115 to detect seizure susceptibility in mutant zebrafish. Treatment with a low dose of the GABA-antagonizing drug pentylenetetrazol (PTZ) produced a significant increase in high-speed events, indicative of seizures in larvae, in both FRMPD2 mutant models (4 dpf) versus controls (Figure 5F). These results suggest that Frmpd2 loss of function, through frmpd2 knockout or antagonism via FRMPD2B, disrupts excitatory synapse transmission which amplifies induced seizures, in line with the known interactions of FRMPD2 with glutamate receptors116.

FRMPD2 (FERM and PDZ domain containing 2) encodes a scaffold protein that participates in cell-cell junction and polarization117. Protein localization has been observed at photoreceptor synapses118 and the postsynaptic membrane in hippocampal neurons in mice116. A partial duplication of the ancestral FRMPD2 on human chromosome 10q11.23 created the 5’-truncated FRMPD2B paralog ~2.3 mya13. This shorter FRMPD2B-derived paralog encodes 320 amino acids of the C-terminus, versus 1,284 amino acids for the full-length ancestral, maintaining two of three PDZ domains involved in protein binding119 while lacking the KIND and FERM domains (Figure 5G).

Our data shows ancestral FRMPD2 expressed in the human prenatal cortex during upper layer formation, while FRMPD2B is evident only postnatally64 (Figure 5G). The paralogs also show divergent evolutionary signatures, with the full-length FRMPD2 strongly conserved and the truncated FRMPD2B exhibiting possible positive selection (Figure 3B,C). Results in zebrafish show that loss of Frmpd2 function results in microcephaly and enhanced excitatory synaptic signaling. Combined, we propose a model in which truncated human-specific FRMPD2B counteracts the function of full-length FRMPD2 leading to altered synaptic features in humans, possibly through interactions of its PDZ2 domain with GluN2A of NMDA receptors at the postsynaptic terminal116. Its postnatal expression would avoid the detrimental effects of inhibiting FRMPD2 during early fetal development (i.e., microcephaly). We note that recurrent deletions and duplications in chromosome 10q11.21q11.23 impact both paralogs in children with intellectual disability, autism, and epilepsy120. Ultimately, FRMPD2B could plausibly contribute to the upregulation of glutamate signaling and increased synaptic plasticity observed in human brains compared with other primates that is fundamental to learning and memory121.

Discussion

Our results provide the scientific community with a prioritized set of hundreds of genes to perform functional analyses with the goal to identify drivers of human brain evolution. Using a complete T2T-CHM13 reference genome, we present the most comprehensive detection of human duplicate genes to date with 213 families and 1,002 total paralogs. Compared to a previous assessment of human-specific duplicated genes13, this represents an approximately fivefold increase in identified genes, in part because we also included human-expanded gene families and genes with as little as one duplicated exon. We note that these numbers are likely an underestimate, as we excluded 193 high-copy gene families (famCN>10), as well families that have undergone independent gene expansions or incomplete lineage sorting with other great apes. One compelling example is FOXO3, encoding the transcription factor forkhead box O-3, implicated in human longevity122, with all three paralogs CN-constrained and brain expressed (Table S1). Since this gene also exists as duplicated in other great apes at similar CN, we excluded it from our list of human gene expansions. This is, in part, because there is still uncertainty regarding which paralog(s) are human specific for many of the gene families. SDs are often accompanied by secondary structural rearrangements that hamper synteny comparisons across species57,123. Moving forward, the availability of nonhuman primate T2T genomes will improve orthology and synteny comparisons between species124–126 revealing additional human-specific paralogs. As a resource for the community, we have made available the results of our genome-wide analyses across the complete 1,793 SD98 genes (Tables S1–S11).

Collectively, 148 gene families (362 paralogs, 108 annotated as non-syntenic with the chimpanzee reference) represent top candidates for contributing to human-unique neural features based on at least one gene member exhibiting functional constraint across modern humans (1KGP) and brain expression (Table S1). In this study, we chose zebrafish to demonstrate the efficacy of our gene list. Despite notable differences with humans, such as the absence of a neocortex127, conservation in major brain features make zebrafish well-suited to characterize gene functions in neurological traits, including cranial malformations128, neuronal imbalances129, and synaptogenesis130. Coupled with CRISPR mutagenesis89,90, zebrafish have been used as a higher-throughput model for human neurodevelopmental conditions such as epilepsy115, schizophrenia131, and autism73. While a whole-genome teleost duplication resulted in ~20% of genes with multiple zebrafish paralogs that confounds functional analysis of human gene duplications132, the nine prioritized gene families tested here were selected in part because each had only one zebrafish ortholog. We characterized gene functions by knocking out the conserved ortholog and introducing the human-specific paralog into developing embryos. Transient availability of the human transgene by injection of in-vitro-transcribed mRNA limited our analysis to early developmental traits (up to 5 dpf in zebrafish), approximately equivalent to human mid- to late-fetal stages in brain development (Figure S10). In the future, it will be important to characterize phenotypes in adolescent and adult zebrafish by generating stable transgenic humanized lines.

From our analysis, knockout and humanized models of four genes (GPR89, FRMPD2, FAM72, and SRGAP2) resulted in altered morphological features, primarily to head size (often used as a proxy for brain size), and all models exhibited molecular differences in single-cell transcriptomic data, most evident in the fore- and midbrains of larvae (Figure 4G). Two duplicate gene families, SRGAP2 and ARHGAP11, have been extensively studied in diverse model systems (reviewed recently9). Our zebrafish model of SRGAP2, encoding SLIT-ROBO Rho GTPase-activating protein 2, were consistent with published findings in mouse where the 3’-truncated human-specific SRGAP2C inhibits the function of the endogenous full-length Srgap216. Further, the shared upregulated genes identified in the forebrains of SRGAP2 mutant larvae point to alterations in axonogenesis and cell migration, matching studies in mice11,16,17,67,93,133,134 (Table S26). Alternatively, ARHGAP11B, encoding Rho GTPase Activating Protein 11, implicated in the expansion of the neocortex through increased neurogenesis21,23, exhibited no detectable changes in head/brain size when introduced in zebrafish embryos. Upregulated DEGs were only detected in the forebrains of ARHGAP11B-injected mutants and were enriched in cellular biosynthetic processes (mRNA splicing and translation; Table S27). Given that ARHGAP11B impacts the abundance of basal progenitors, a cell type unique to the mammalian neocortex135, zebrafish may not be suitable to characterize human-specific functions of this gene.

Beyond modeling gene functions, our study also highlighted the considerable amount of genetic variation hiding within SD regions. Even with the resolved gaps and errors across SDs in T2T-CHM13, short-read sequencing is still insufficient to identify variation. Due to high sequence identity, only 10% of SD98 regions are “accessible” to short reads36 resulting in <10% sensitivity to detect variants (Note S1) and a depletion of GWAS hits (Note S2). Using existing assemblies (HPRC and HGSVC) and cHiFi sequencing of individuals of diverse ancestry uncovered some of this hidden variation within our 13 pHSD gene families. We note that, for some of the most highly identical duplicated genes (CFC1), our cHiFi reads (~3 kbp) were still too short to accurately map to respective paralogs (data not included). Nevertheless, long reads revealed that most pHSD paralogs exhibit evolutionary constraints and provided support for balancing selection of CD8B, not previously identified in published genome-wide screens136,137. Historically, signatures of balancing selection, which include an excess of mid-frequency alleles138, have been difficult to detect within SDs due to assembly errors36. In these cases, paralog-specific variants are mistaken for SNPs when reads from both paralogs map to a single collapsed locus resulting in false mid-frequency alleles. Scientific consortia like All of Us are generating long-read datasets at scale139, ushering in a new era where genomic associations and evolutionary selection may finally be uncovered within human duplications to identify novel drivers of human traits and disease.

Similarly, genome sequencing of patients and their families has discovered hundreds of compelling neuropsychiatric disease candidate genes impacted by rare and de novo variants, but the genetic risk underlying conditions such as autism is still not completely elucidated140. SD genes may represent a hidden contributor to disease etiology. Our analysis identified 82 SD98 genes (38 human duplicate paralogs) co-expressed in modules enriched for ASD genes (Figure 2E), including several within disease-associated genomic hotspots. Distinct SD mutational mechanisms, including ~60% higher mutation rate compared to unique regions141 and interlocus gene conversion that can occur between paralogs142,143, make duplicated genes particularly compelling to screen for de novo mutations contributing to idiopathic conditions. For example, nonfunctional paralogs with truncating mutations can “overwrite” conserved functional paralogs leading to detrimental consequences, as is the case of SMN1 and SMN2 in spinal muscular atrophy39. Human-duplicated gene families include ancestral paralogs CORO1A, TLK2, and EIF4E, with significant genetic associations with ASD57. We propose that interlocus gene conversion between their likely nonfunctional duplicate counterparts is an understudied contributor to neurodevelopmental conditions in humans. Our comprehensive list of gene families will enable future work to progress in this research area.

Our study focuses on duplicate genes functioning in brain development, but primates exhibit other prominent differences across musculoskeletal and craniofacial features that have diverged early in human evolution4. Since such traits are largely universal across modern humans, our list of CN-constrained genes represent top candidates though re-analysis of transcriptomes from non-brain cells/tissues is required. Meanwhile, duplicate genes, such as those encoding defensins144–147, mucins148,149, and amylases41–43, can also play a role in metabolism and immune response that exhibit population diversification due to the vast variability in diet, environment, and exposures to pathogens across modern humans27. Our use of a single complete human T2T-CHM13 haplotype of largely European ancestry34 could miss some of these CN polymorphic genes. As additional T2T genomes are released28, it will be important to continue curating our list of duplications. Nevertheless, genes CN stratified by human ancestry can be identified using metrics such as Vst150, as has been highlighted in other studies (reviewed here9 and most recently in a preprint151). Facilitating such analyses for our gene set, we provide a publicly available resource to query parCN median estimates across individuals from 1KGP for our complete set of SD98 paralogs (https://dcsoto.shinyapps.io/shinyc).

One notable limitation of our study is its reliance on existing gene annotations. We attempted for the first time to group human duplicate paralogs into larger multigene families based on shared sequences between annotated genes in SD98 regions. Due to the complexities of SDs, which can result in gene fusions and altered gene structures, some genes were left unassigned to a family (n=114 singletons from SD98 genes). Other noncoding transcripts and lncRNAs were excluded altogether, including a human-specific paralog of IQSEC3, a gene implicated in GABAergic synapse maintenance152. Additionally, the functional consequences of variants identified in 656 unprocessed pseudogenes are difficult to interpret. Improvements are on the horizon, with ongoing work with long-read transcriptomes that will continue to refine annotations153 and advancements in protein-prediction models154 and proteomic approaches155 that will confirm whether or not these genes encode proteins.

In summary, we identified and featured two genes with strong evidence of contribution to human brain evolution: GPR89B, with a possible role in expansion of the neocortex, and FRMPD2B, with implications in altered synaptic excitatory signaling. Taking advantage of long-read sequencing in tandem with the new T2T-CHM13 reference genome, we interrogated challenging regions of the genome and demonstrated a method using zebrafish to explore the functions of human-duplicated genes. Among our list of hundreds, we propose that there are additional gene drivers that contribute to unique features of the human brain. In the future, additional genetic analyses across modern and archaic humans and experiments utilizing diverse model systems will reveal hidden roles of these genes in human traits and disease.

Methods

Identification of SD98 genes

Duplicated regions were extracted from previously annotated SDs156 using T2T-CHM13 (v1.0) coordinates and subsequently merged using BEDTools merge157. SD98 regions were defined as an SD with ≥98% sequence identity to another locus in the T2T-CHM13 genome using the fractMatch parameter. Gene coordinates were obtained from T2T-CHM13 (v1.0) CAT/Liftoff annotations (v4)34. SD98 genes were defined as gene annotations that contain at least one exon fully contained within an SD98 region, calculated with BEDTools intersect using -f 1 parameter157. Overall numbers of distinct gene features overlapping SD98 were counted using the gene ID unique identifiers. We noticed that, in a few cases, two transcript isoforms of the same gene were assigned to different gene IDs. To identify these redundant transcripts, we self-intersected SD98 transcripts, selected those with different gene ID that also shared >90% positional overlap, and performed manual curation of the obtained gene list, removing redundant and read-through fusion transcripts.

Gene family clustering

SD98 genes were grouped into gene families based on shared exons (Figure S1). Starting from T2T-CHM13 (v1.0) annotations, DNA sequences of all SD98 regions were extracted using BEDTools getfasta and mapped back to the reference genome using minimap2 (v2.17) with the following parameters: -c --end-bonus 5 --eqx -N 50 -p 0.5 -t 64. For each SD98 exon, the BEDTools intersect with -f 0.99 parameter was used to select mappings covering >99% of the exon sequence, removing self-mappings. This list was refined using the previously published35 whole-genome shotgun sequence detection (WSSD)10 CNs (famCN) of humans from the SGDP (n=269), which provides estimates of the overall CN of a gene family using read depth of multi-mapping reads with nonoverlapping sliding-windows. After comparing the median famCN values of SD98 genes with shared exons, groupings where the mean absolute deviation of the CN was less than one were selected. The list was filtered to focus on gene families containing at least one protein-coding or unprocessed pseudogene. SD98 genes associated with other gene features, including lncRNAs and processed pseudogenes, were also assigned a gene family ID. On the other hand, if a gene was not associated with any other gene feature, they were classified as “unassigned” or “singletons”. SD98 gene families were intersected with previously published DupMasker annotations using BEDTools intersect, which indicate ancestral evolutionary units of duplication35.

Identification of human-duplicated genes families

Human-specific and -expanded gene families were identified using CN comparisons between humans and nonhuman great apes with previously published WSSD10 (famCN) CNs from humans (SGDP n=269) and four nonhuman great apes, including one representative of chimpanzee (Clint), bonobo (Mhudiblu), gorilla (Kamilah), and orangutan (Susie)35, mapped to T2T-CHM13 (v1.0). The median famCN per SD98 gene was calculated using a custom Python script. For each SD98 gene, putative gene family duplications and expansion were predicted, excluding genes with median famCN>10 across humans from this analysis. Genes were considered expanded if the median famCN across humans was greater than the maximum famCN across great apes. Human duplications and expansions were distinguished based on whether the maximum famCN value across great apes was less than 2.5 (non-duplicated in great apes) or greater than 2.5 (duplicated in great apes), respectively. Non-syntenic paralogs between humans and chimpanzees were obtained using previously published syntenic data between human (T2T-CHM13v1.0) and chimpanzee (PanTro6) references35 intersected with SD98 genes using BEDTools intersect. For each paralog, family status was designated as “Human-duplicated gene family” if it was assigned to a gene family containing at least one expanded or duplicated member according to famCN and/or at least one non-syntenic member based on human/chimpanzee synteny. Otherwise, family status was considered “Undetermined”.

Paralog-specific copy number genotyping

parCN estimates were obtained using QuicK-mer246 for 1KGP 30× high-coverage Illumina individuals55 and four archaic genomes (including Altai Neanderthal [PRJEB1265]47, Vindija Neanderthal [PRJEB21157]48, Mezmaiskaya Neanderthal [PRJEB1757]47,48, and Denisova [PRJEB3092]49), using T2T-CHM13 (v1.0) as reference34. The resulting BED files containing parCN estimates were converted into bed9 format using a custom Python script for visualization in the UCSC Genome Browser. parCN values were genotyped across SD98 regions overlapping protein-encoding and unprocessed pseudogenes by calculating the mean parCN across the region of interest for each sample using a custom Python script. parCN dotplots generated using the R package ggplot2 are available for SD98 genes as an interactive Shiny web application in https://dcsoto.shinyapps.io/shinycn.

Metrics of selective constraint

Loss-of-function intolerance of SD98 genes was assayed using previously published gnomAD (v2.1.1) probability of loss-of-function intolerance scores (pLI)158 and loss-of-function observed/expected upper fraction (LOEUF)52. We considered genes as intolerant to loss of function if either their pLI scores were greater than 0.9 or their LOEUF scores were less than 0.35.

Genome-wide Tajima’s D analysis

Additionally, Tajima’s D54 values were calculated using previously published SNPs obtained from high-coverage short-read sequencing data from unrelated 1KGP individuals (n=2,504)55, remapped to T2T-CHM13 (v1.0)36. Windows were defined as SD98 if at least 10% of the bases corresponded to SD98 regions. To define short-read accessible windows, 25-kbp windows were intersected with a published short-read combined accessibility mask36. Considering that no SD98 windows were fully accessible (Figure S4), Tajima’s D was calculated for each superpopulation using VCFtools159 across 25-kbp windows of at least 50% accessibility and with five or more SNPs. Because previous studies have highlighted potential discrepancies of evolutionary constraints experienced between duplicated and non-duplicated genomic loci160, outlier D values were calculated for each continental superpopulation as the 5th and 95th percentiles within SD98 windows only, thereby avoiding comparisons between duplicated and unique regions. Outlier threshold values for each population were defined as follows: AFR, −2.21 and −0.67; EUR, −2.37 and 0.08; EAS, −2.48 and −0.10; SAS, −2.40 and −0.28; and AMR, −2.40 and −0.41.

Association with neural traits

Gene-disease associations were obtained from the GWAS catalog v1.0161. SNPs significantly associated with brain measurements (p-value < 0.05) were selected, and the GWAS “mapped genes” were intersected with the SD98 gene list using gene symbols. Similarly, previously published associations between CNVs and neural traits in the UKBB were obtained56. Coordinates of CNVs significantly associated with brain measurements (p-value<0.05) were lifted over from hg19 to hg38 and from hg38 to T2T-CHM13 (v1.0) using UCSC liftOver tool162. Liftover chains were obtained from the UCSC Genome Browser and T2T-CHM13 GitHub page (https://github.com/marbl/CHM13, previous assembly releases of T2T-CHM13), respectively. CNVs were intersected with SD98 gene coordinates using BEDTools intersect157.

ParCN values from SD98 genes for families with autistic children from the SSC (n = 2,459 families, n = 9,068 individuals) mapped to the T2T-CH13v1.1 reference genome were obtained, following the same steps as described to genotype parCN across 1KGP individuals. Overall, CN differences between autistic probands and unaffected siblings were compared by rounding median CN per individual to the nearest integer, and significance was assessed using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test, correcting for multiple testing with the false discovery rate method. To identify de novo deletions or duplications in autistic probands and unaffected siblings, parCN values within ±0.2 of an integer were conservatively selected and rounded to the nearest integer for all family members. Intermediate values, which could potentially confound the analysis, were removed. De novo events were classified as cases where both parents exhibited a parCN=2, while the child showed a parCN=3 (duplication) or parCN=1 (deletion).

Previously published genomic hotspots60 were obtained in hg19 coordinates and lifted over to hg38 and from hg38 to T2T-CHM13 (v1.0) using the UCSC liftOver tool and associated chain files (described above). Three regions failed the liftover process due to differences in reference genome sequences. An extra 500 kbp were added upstream and downstream of each reported genomic hotspot to account for breakpoint errors. SD98 genes, including those exhibiting putative de novo events in the SSC dataset, were intersected with expanded genomic hotspots coordinates using BEDTools intersect.

Gene expression and network analysis

Previously published brain transcriptomic datasets, including post-mortem tissue and cell lines, were obtained. These datasets included neocortical germinal zones61, neural stem and progenitor cells21, a neuroblastoma cell line SHSY5Y62, and two longitudinal studies of in vitro induced neurogenesis from human embryonic stem cells63 (CORTECON), and post-mortem brain (BrainSpan)64—the latter of which was separated into prenatal and postnatal samples. Raw reads were pseudo-mapped to T2T-CHM13 (v2.0) CAT/Liftoff transcriptome and the CHM13v2.0 assembly as decoy sequence using Salmon v1.8.0163 with the flags “--validateMappings --gcBias”. Transcripts per million (TPM) values and raw counts were summed to the gene level using tximport164. An SD98 gene was considered expressed during development if TPM values were greater than one in at least one of these samples, excluding postnatal BrainSpan data. Conversely, an SD98 gene was considered expressed postnatally if TPM values were greater than one in at least one postnatal stage of BrainSpan.

Gene co-expression analysis was performed using the WGCNA R package65. Briefly, samples were analyzed using principal components and hierarchical clustering to assess outliers, removing two samples (SRR1238515 and SRR1238516). Features with consistently low counts across remaining samples (counts <10 in 90% samples) were removed from this analysis. Raw counts for each sample were normalized using variance stabilizing transformation before performing a signed network construction with function blockwiseModules, with parameters soft power = 24, deepSplit = 4, detectCutHeight = 0.995, minModuleSize = 30, and MergeCutHeight = 0.15. GO terms enrichment analysis was performed using the R package clusterProfiler ego function165. Enrichment of gene categories were performed using the hypergeometric test in R for autism genes57, expanded genomic hotspots60, and cell markers68.

Visualization of the yellow network was constructed by selecting genes with module membership greater than 0.5, generating an adjacency matrix with remaining genes, and then reconstructing a signed network with soft threshold = 18. Edges with Pearson correlation <0.1 were removed. The network visualization was built with the igraph R package (https://r.igraph.org/), using layout_with_fr for vertex placement. Vertex size was proportional to the degree and edges width was proportional to the Pearson’s correlation coefficient. Some vertices were manually adjusted to improve aesthetics of the plot.

Mouse and zebrafish orthologs

Mouse-human orthologs were obtained from the Mouse Genome Informatics (MGI) complete list of human and mouse homologs and ENSEMBL BioMart, intersected with SD98 genes using gene symbols, and manual curation. Zebrafish-human orthologs were obtained from combined ENSEMBL BioMart annotations, MGI complete list of vertebrate homology classes, and manual curation. MGI files were downloaded from their website (https://www.informatics.jax.org/homology.shtml) and BioMart analyses were performed using the R package biomaRt. Comparison of developmental brain expression of SD98 orthologs in model organisms was performed using previously published expression data for mouse (PRJNA637987)70 and zebrafish (GSE158142)71, calculating Z-score normalized TPM values. Matching of developmental stages across human, mouse, and zebrafish was done as previously described72. In brief, genes with one-to-one orthologs with human genes were identified (mouse n= 19,949; zebrafish n= 16,910) and the principle component analysis rotations of the human BrainSpan data used to predict PC coordinates for the mouse and zebrafish data in human principle component space.

Capture HiFi (cHiFi) sequencing

We performed cHiFi sequencing of 172 individuals from the 1KGP, two trios from Genome in a Bottle166, and 22 HGDP individuals with available linked-read data via the 10X Genomics platform167, totaling 200 samples and 18 family trios (Table S13). DNA samples for 1KGP and Genome in a Bottle were obtained from the Coriell Institute (Camden, NJ, USA) and HGDP samples were obtained from the CEPH Biobank at the Fondation Jean Dausset-CEPH (Paris, France). PacBio cHiFi sequencing was performed using the RenSeq protocol168. Briefly, genomic DNA (~4 μg) was sheared to approximately 3 kbp with the Covaris E220 sonicator using Covaris blue miniTUBEs, followed by purification and size selection with AMPure XP beads. End repair and adapter ligation were performed using the NEBNext Ultra DNA Library Prep Kit. Barcodes to distinguish each sample were added via PCR using Kapa HiFi Polymerase (Roche, CA, USA). After the first PCR (fewer than 9 cycles), the libraries were purified and size-selected. For target enrichment, 80-mer RNA baits were designed and tiled at 2× coverage across targeted SD regions and unique exonic regions (Table S28). pHSD regions of interest were targeted and enriched for using a custom myBaits kit (Arbor Biosciences, MI, USA) following manufacturer’s recommended protocol. Eight pooled barcoded libraries were hybridized overnight to the baits, and the captured DNA was bound to Dynabeads MyOne Streptavidin C1 beads. A second PCR was performed post-hybridization to generate sufficient material for sequencing. A PCR cycle test was conducted prior to the second amplification to limit PCR duplication bias.

The final libraries were size-selected using the Blue Pippin system to enrich for fragments >2 kbp and sequenced on the PacBio Sequel II platform (Maryland Genomics, University of Maryland). Briefly, Sequel II libraries were constructed using SMRTbell Express Template Prep Kit 2.0 (Pacific Biosciences, Menlo Park, CA) according to manufacturer’s instructions. In brief, DNA samples were treated with DNA-damage repair enzymes followed by end-repair enzymes before being ligated to overhang sequencing adaptors. Libraries were then purified with SPRI beads (Beckman Coulter, Indianapolis, IN) and quantified on the Femto Pulse instrument (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). Prior to sequencing, libraries were bound to Sequel II polymerase, then sequenced with Sequel II Sequencing kit and SMRT cell 8M on the Sequel II instrument (Pacific Biosciences, Menlo Park, CA). The approach yielded ~3-kbp reads with an average coverage of 27× across regions of interest, considering reads with MAPQ greater than 10 (Table S29).

Long-read genetic variation discovery and analysis

cHiFi reads were processed using the standard PacBio SMRT sequencing software tools available in the Conda repository pbbioconda. Circular consensus was obtained from subreads using CCS command with the following parameters --minPasses 3 and --minPredictedAccuracy 0.9. PacBio adapters and sample barcodes were removed using lima software and duplicates were removed with pbmarkdup. Resulting cHiFi reads were aligned to T2T-CHM13v1.0 reference using pbmm2 align, a wrapper of minimap2, with the CCS preset and default parameters. Read groups were added with Picard AddOrReplaceReadGroups and variants were called on each sample using GATK HaplotypeCaller169, using ploidy = 2 and minimum mapping quality thresholds for genotyping of 0, 2, 5, 10 and 20, resulting in gVCF files per sample for joint genotyping. Joint genotyping was performed with GATK CombineGVCFs and GenotypeGVCFs tools using the pedigree file for accurate calculation of inbreeding coefficients. Genotyping was performed using minimum confidence threshold of 0, 10, 20 and 30. As the technical profile of variants in SDs differs from Variant Quality Score Recalibration training sets, a hard-filtering approach was utilized, including genotyping quality threshold of 0, 20, 50, 70, and depth of 0, 4, 8, 12, and 16. Based on a comprehensive benchmark, including comparison of cHiFi with HPRC/HGSCV and trio mendelian concordance (Note S3), the following minimum thresholds were selected: mapping quality of 20, confidence of 30, genotype quality of 20, and depth of 8. Only unrelated samples from the 1KGP were selected for downstream population analyses (n=144).

Fully phased haplotypes from 47 individuals from the HPRC Year 1 freeze (https://github.com/human-pangenomics/HPP_Year1_Data_Freeze_v1.0) and 15 from the HGSVC79 were downloaded. Each haplotype was mapped to T2T-CHM13v1.0 reference genome using minimap2 with parameters -a --eqx --cs -x asm5 --secondary=no -s 25000 -K 8G, and unmapped contigs and non-primary alignments were discarded. For each region of interest, the longest alignment spanning the locus was selected and additional alignments were removed. This process ensured that one single contiguous contig was used for variant detection. Variants were called with htsbox pileup with parameters -q 0 -evcf and converted into diploid calls using dipcall-aux.js vcfpair. For each region of interest, individual sample calls were merged into a multi-sample VCF file using BCFtools merge, only including individuals whose two haplotypes fully spanned the region of interest. Redundant samples between the HPRC and HGSVC (HG00733, HG02818, HG03486, NA19240, NA24385) were removed, prioritizing HPRC assemblies. Finally, the HPRC/HGSVC dataset was merged with cHiFi variants from 144 unrelated samples into a combined dataset for downstream analyses using BCFtools merge. Functional consequences of the combined dataset were assessed using the ENSEMBL Variant Effect Prediction (VEP) tool.

Haplotype networks for CD8B were constructed using HPRC/HGSVC continuous haplotypes extracted with BEDtools getfasta and aligned with Muscle using Mega Software170. Networks were generated using a minimum spanning tree with the software PopArt171.

Tests for signatures of natural selection