Abstract

Primary ovarian insufficiency (POI) is a disorder of insufficient ovarian follicle function before the age of 40 years with an estimated prevalence of 3.7% worldwide. Its relevance is emerging due to the increasing number of women desiring conception late or beyond the third decade of their lives. POI clinical presentation is extremely heterogeneous with a possible exordium as primary amenorrhea due to ovarian dysgenesis or with a secondary amenorrhea due to different congenital or acquired abnormalities. POI significantly impacts non only on the fertility prospect of the affected women but also on their general, psychological, sexual quality of life, and, furthermore, on their long-term bone, cardiovascular, and cognitive health. In several cases the underlying cause of POI remains unknown and, thus, these forms are still classified as idiopathic. However, we now know the age of menopause is an inheritable trait and POI has a strong genetic background. This is confirmed by the existence of several candidate genes, experimental and natural models. The most common genetic contributors to POI are the X chromosome-linked defects. Moreover, the variable expressivity of POI defect suggests it can be considered as a multifactorial or oligogenic defect. Here, we present an updated review on clinical findings and on the principal X-linked and autosomal genes involved in syndromic and non-syndromic forms of POI. We also provide current information on the management of the premature hypoestrogenic state as well as on fertility preservation in subjects at risk of POI.

Keywords: female hypogonadism, estradiol, estradiol replacement therapy, premature menopause, premature ovarian failure

1. Introduction

Primary ovarian insufficiency (POI) is characterized by impaired or intermittent ovarian follicle function before age 40 (1, 2), determined by diminished number of primordial follicles, accelerated follicular atresia, blocked follicle maturation or follicular dysfunction. The cut-off age of 40 years is used because it represents two standard deviations below the mean age of natural menopause. The definition and appropriate terminology of this condition have been debated for decades (3): the aforementioned definition of POI, which should replace the terminology of ‘premature ovarian failure (POF)’, has the advantage of clearly defining the ovarian origin of the condition, as is common practice in endocrinology. Moreover, the latter definition does not take into account the biological course of the condition, and is uninformative and stigmatizing for patients who may not experience the cessation of ovarian function at the time of diagnosis. POI should be intended as a wide clinical spectrum, with considerable variability of clinical presentation and its own natural history. It is a condition characterized by strong genetic susceptibility, occurring in up to 30% of cases in familial form, whose expression is modulated by various environmental factors (4, 5). It is a heterogeneous disorder, which can be acquired or congenital, although in 70-90% of cases it remains idiopathic (6), although more recent data suggest that, as a result of the effort made in identifying new genetic mechanisms, the percentage of idiopathic forms currently stands at 39% to 67% (2). Depletion or dysfunction of ovarian follicles leads to amenorrhea and subsequently to menopausal symptoms, infertility, and sexual dysfunction which adversely impact not only the physical and mental well-being of those affected but also their self-esteem and interpersonal relationships (7). Thus, the quality of life of women with POI is affected from a physical, psychological, and social point of view. The relevance of POI is emerging as the desire of women to conceive beyond the age of 30 grows, when the incidence of POI is the greatest, and life expectancy is extended, and, in turn, also the duration of hypoestrogenism. Considering the rising incidence of the condition in younger ages as well (8, 9), POI presents a growing challenge for women, as it interferes with their reproductive desires. At the same time, POI diagnosis, especially at younger ages, heightens the risk of associated morbidities and is expected to lead to early mortality, thereby having serious consequences on the health of those affected (10, 11). Therefore, gaining a deep understanding of POI is critical for its early diagnosis, development of an effective long-term management and patient counseling strategy. This would finally lead to improvements in the overall quality of life, including the physical and psychological well-being, reproductive health and primary life goals of the affected women.

2. Epidemiology

The Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN) reported that approximately 1.1% of women under the age of 40 in the general population are affected by POI (12). However, a recent large-scale meta-analysis study estimated the global prevalence of POI to be 3.7% (13). The incidence of POI declines exponentially with decreasing age. Specifically, the incidence rate ratios are 1:100 for women between 35 and 40 years old, 1:1,000 for women between 25 and 30 years old, and 1:10,000 for women between 18 and 25 years old (14). Interestingly, a nationwide Israeli study in women under 21 years of age, showed that the incidence rate of POI diagnoses doubled in the period of 2009-2016 compared to the period of 2000-2008 (8). Additionally, the results of a recent Finnish study suggest an increase in the incidence rate of the condition in adolescent girls, aged 15-19, from 2007 to 2017 (9). These results place emphasis on the discrepancy between the past and recent epidemiologic data, whilst indicating a rise in the incidence of POI amongst younger women, that could also reflect a change towards a more active approach to primary amenorrhea among adolescent women. The prevalence and incidence rates also differ across ethnicities. A multi-ethnic cross-sectional study conducted by Luborsky et al. (12) demonstrated significantly higher incidence rates in Hispanic and African American women compared to Japanese and Chinese women. Additionally, two population-based cohort studies on the Swedish and Iranian populations showed a prevalence of 1.9% and 3.5%, respectively (15, 16). Remarkably, first-degree relatives of women with POI have an increased risk of having POI themselves (9, 17, 18).

3. Etiopathogenesis

3.1. Genetic causes

Although POI negatively affects fertility, several studies have indicated that this condition has a strong heritable, and therefore genetic, component. A decade ago, Stolk and colleagues identified common loci associated with the age at menopause by a genome wide association study (19). However, the exact mechanisms underlying the heritability of this condition are not yet completely understood. The fact that mothers and daughters show a tendency of inheritance of the menopausal age supports the view of the inheritable susceptibility to POI, with a demonstrated high prevalence (31%) of familial POI in patients (18). Moreover, the even higher incidence of early menopause (EM) occurring within the same family group or among first-degree relatives also indicates a variable expression of the same genetic disease predisposition (20, 21). Two recent population-based studies further assessed the familial clustering of POI. In Finland, it has been estimated an odds ratio of 4.6 (95% CI 3.3-6.5) for POI in first-degree relatives of 129 women with POI (9). Whereas in a cohort of 396 cases from Utah, first-degree relatives demonstrated an 18-fold increased risk of POI compared with controls relative risk (RR, 18.52; 95% CI, 10.12–31.07), second-degree relatives demonstrated a 4-fold increase (RR, 4.21; 95% CI, 1.15–10.79), and third-degree relatives demonstrated a 2.7-fold increase (RR, 2.65; 95% CI, 1.14–5.21) (17). Hereditary disorders can affect the functioning of the ovaries and contribute to the development of POI: among the genetic conditions that have been associated with an increased risk of POI, there are X chromosome aneuploidies, together with polymorphisms and mutations in several causative genes, that are associated with either pleiotropic genetic syndromes or isolated cases ( Tables 1 – 3 ).

Table 1.

Syndromic forms of POI.

| CHROMOSOMAL ABNORMALITIES | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Syndrome | Kariotype | Molecular Mechanism | Phenotypes | Frequency | Ref. | ||

| Turner Syndrome (X monosomy) | (45,X/ 46,XX), mosaicisms |

Short stature and other skeletal dysmorphism may associate to cardiac defects, hearing loss and hypothyroidism. Accelerated PmFs atresia with ovarian reserve reduction cause either SA or gonadal dysgenesis (with streak ovaries and elevated FSH levels since infancy) | X structural abnormalities, with partial/complete loss of one X chromosome due to deletion, translocation, inversion, or formation of an isochromosome. Possibly, chromosomal pairing fails during meiosis or dosage effect of X-linked genes escapes X inactivation | 1:2500 live births; 4-5% of POI cases | (22–24) | ||

| Triple X Syndrome (X trisomy) | 47,XXX | Low AMH with increased FSH and LH. Occasionally longer legs, delayed language development, poor motor coordination and increased risk of POI or genitourinary abnormalities | Non-disjunction errors in meiosis I or II in oogenesis | 1:1000 women (often undiagnosed due to modest symptoms) | (25, 26) | ||

| Xp and Xq deletions | Large deletions associated with high POI incidence at a young age, but no simple relationship between phenotype and chromosomal loss. - Xp(del): Xp11 is the most common breakpoint for terminal deletions, leading to either PA (55%) or SA (45%). Deletion of the most telomeric portion (Xp22.3 - Xpter) does not result in amenorrhea. - Xq(del): Breakpoints cluster at Xq13 - Xq21 (balanced translocations) and Xq23 - Xq27 (interstitial deletions). Xq13del are associated with PA and absent secondary sexual development. Terminal deletions at Xq25 or Xq26 seem not linked to PA; more distal deletions have mild phenotypes |

Disruption of gene expression balance | 4%-12% of POI cases | (27–30) | |||

| X autosome translocations | PA or SA; Turner stigmata if translocation occurs within the critical region Xq13-q26 | Haploinsufficiency/disruption of critical genes, positional effect on contiguous genes or non-specific/defective meiotic pairing | |||||

| Gonadal Dysgenesis | 46,XY | External female genitalia, bilateral streak gonads, minimal breast enlargement, propensity for malignant transformation of the gonads | Several genetic causes have been identified, including mutation in NR5A1, SOX9, SRY, GATA4, WT1 | rare | (31) | ||

| AUTOSOMAL POI SYNDROMES | |||||||

| Pathology | OMIM | Gene | Gene Functions | Phenotypes | Inheritance (AD, AR) | Ref | |

| Pseudo-hypoparathyroidism type 1a | #103580 | GNAS | Ubiquitously expressed gene, but high levels in thyroid and brain. GNAS encodes for the α-subunit of the stimulatory GTP binding protein with key roles in several cellular responses triggered by receptor-ligand interactions | Resistance to parathyroid hormone, to thyroid-stimulating hormone, gonadotropins and growth-hormone-releasing hormone. Sometimes associated with short stature, skeletal anomalies, ectopic ossifications, obesity, mental retardation and hypogonadism with incomplete sexual maturation, delayed puberty, oligomenorrhea or SA | AD, maternally inherited. Parent-specific methylation and paternal protein expression reduction | (32–36) | |

| Blepharophimosis, ptosis, epicanthus inversus (BPES) type 1 | #110100 | FOXL2 | Expressed in the developing eyelids and in fetal/adult ovary. Role in GCs differentiation, folliculogenesis and postnatal maintenance of ovaries, estrogen production and steroidogenesis, repressing male sex determination | Bilateral eyelid dysplasia with small palpebral fissures, drooping eyelids and skin fold starting from the lower eyelid and running inward and upward, inherited with ovarian failure (PA or SA with absent or rare follicles). FOXL2 (*605597) is occasionally described in isolated PA or SA with a prevalence of 1.0% – 3.2% |

AD, AR | (37–42) | |

| Perrault Syndrome | #614129 | CLPP | Mitochondrial function | Mild to severe bilateral hearing loss and ovarian dysfunction, ranging from gonadal dysgenesis to SA, with streak, absent or small ovaries. In some cases, patients also present with variable neurological signs. LARS2 (*604544) is occasionally described in non-syndromic SA |

AR | (43–49) | |

| #617565 | ERAL1 | ||||||

| #614926 | HARS2 | ||||||

| *614917 | RMND1 | ||||||

| *609947 | PRORP | ||||||

| #616138 | TWNK | ||||||

| #615300 | LARS2 | ||||||

| #233400 | HSD17B4 | Cellular metabolism | |||||

| *606982 | GGPS1 | ||||||

| *601498 | PEX6 | ||||||

| *605810 | MRPS7 | Mitochondrial large and small ribosomal subunit | |||||

| *611972 | MRPL50 | ||||||

| Progressive external ophthalmoplegia (PEO) A1 | #157640 | POLG | Encodes for the catalytic subunit of the mitochondrial DNA polymerase | Progressive weakness/paralysis of the eye muscle, myopathy, sensory axonal neuropathy, ataxia, parkinsonism and delayed sexual maturation, associated in women to PA or SA (with diminished follicle reserve). Multiple mtDNA deletions triggers mitochondrial depletion POLG (*174763) is occasionally described in isolated SA |

AD, AR in isolated SA | (50–52) | |

|

Mitochondrial DNA depletion

syndrome 11 |

#615084 | MGME1 | Mitochondrial genome integrity maintenance | PEO, respiratory insufficiency, emaciation, ptosis, gastrointestinal and skeletal abnormalities, dysphonia | AR | (53) | |

| Leuko-encephalolophaty | Ovarioleukodystrophy | #603896 | EIF2B4 | Protein synthesis under cellular stress conditions; likely responsible of increased apoptosis of ovarian follicles | Unusual association of chronic and progressive neurological deterioration (brain white matter degeneration) and ovarian dysfunctions. EIF2B2 (*606454) is occasionally described in isolated PA or SA |

AR | (54) |

| EIF2B5 | |||||||

| EIF2B2 | |||||||

| LKENP | #615889 | AARS2 | Mitochondrial alanyl-tRNA synthetase | Progressive loss of motor and cognitive skills with ovarian failure | AR | (55, 56) | |

| Woodhouse-Sakati syndrome | #241080 | DCAF17 | Nuclear transmembrane protein that associates with ubiquitin ligase complexes | Hypogonadism, alopecia, and neurological defects | AR | (57) | |

| Prolyl endopeptidase-like deficiency | *609557 | PREPL | Regulation of exocytosis of synaptic vesicles | Neonatal hypotonia, feeding difficulties, ptosis, neuromuscular and cognitive symptoms, growth hormone deficiency and hypergonadotropic hypogonadism | AR | (58) | |

| Cockayne Syndrome B | #133540 | ERCC6 (CSB-PGBD3) | Response to DNA damage | POI (principally PA) and neurological abnormalities | AD | (59) | |

| XRCC4-related Disorder | #616541 | XRCC4 | Double strand breaks (DSBs) repair | Short stature, microcephaly, developmental delay, neurological defects and gonadal failure (associated with SA) | AR | (60) | |

| Nijmegen breakage syndrome | #251260 | NBN | Chromosomal stability | Facial dysmorphism, predisposition to cancer and POI. (PA or SA, with streak gonad, small ovaries). NBN (*602667) is occasionally described in isolated POI |

AR | (61, 62) | |

| Ataxia telangiectasia | #208900 | ATM | Check-point, cellular response after DNA damages. Ovarian age control | Cerebellar ataxia, telangiectasis, immune defects, and predisposition to malignancy. Associated to PA. ATM (*607585) is occasionally described in isolated POI |

AR | (63) | |

| Retinal Dystrophy | #617175 | RCBTB1 | Ubiquitination processes | Retinal Dystrophy, with or without extraocular anomalies, such as POI | AR | (64) | |

| *616618 | ACBD5 | Peroxisomal membrane protein | (65) | ||||

| Premature aging (Progeria) | Bloom syndrome | #210900 | BLM | Helicases involved in homologous recombination repair | Acceleration of aging process and highly variable somatic abnormalities, together with hypogonadism and SA, associated with increased follicular atresia. Ovarian aging may be influenced by abnormal epigenetic modifications (changes in methylation levels, histone modifications or non-coding RNA expression) in germ cells and early embryos may influence | AR | (66) |

| Werner syndrome | #277700 | WRN | AR | (67) | |||

| Hutchinson-Gilford | #176670 | LMNA | Key component of the nuclear lamina | AD | (68) | ||

| Rothmund-Thomson syndrome type 2 | #268400 | RECQL4 | DNA helicase | Poikiloderma, telangiectasia, photosensitivity, skin atrophy, congenital bone defects and increased risk of osteosarcoma/skin cancer together SA and gonadotropin resistance | AR | (69) | |

|

Acromesomelic Dysplasya

(Demirhan syndrome) |

#609441 | BMPR1B | Gonadal and skeletal development | Chondrodysplasia characterized by short stature and hand/foot malformations, associated with PA, hypergonadotrophic hypogonadism and genital anomalies. BMPR1B (*603248) is occasionally described in isolated SA |

AR, AD or AR in isolated POI |

(70) | |

|

Proximal symphalangism

(SYM1) |

#185800 | NOG | BMP4 and BMP7 ligand with roles in cartilage and ovarian development | Skeletal abnormalities (fusion of interphalangeal joints and carpal/tarsal bones) sometimes associated with hearing loss and SA | AD | (71) | |

| GAPO syndrome | #230740 | ANTXR1 | Actin assembly, cell adhesion and matrix build-up | Growth retardation, alopecia, failure of tooth eruption and progressive optic atrophy, sometimes associated with SA and follicle depletion | AR | (72, 73) | |

| Fanconi Anemia | #227650 | FANCA | DNA repair after crosslinking damage (maintenance of genome stability) | Developmental defects, early-onset bone marrow failure and high predisposition to cancer. Impairment in follicular development due to defective oocyte meiosis and abnormal germ cell development with PA or SA. FANCA (*607139), FANCL (*608111), FANCM (* 609644), FANCU (*600375), FANCD1 (*600185) are occasionally described in isolated POI (principally SA) |

AR, AD or AR isolated POI |

(74, 75) | |

| #227645 | FANCC | ||||||

| #614083 | FANCL | ||||||

| #605724 | FANCD1/BRCA2 | ||||||

| #617247 | FANCU/XRCC2 | ||||||

| #614082 | FANCG/XRCC9 | ||||||

| Adrenal Hyperplasia | #201710 | STAR | Steroid hormone biosynthesis | Adrenogenital syndrome, insufficient cortisol production, atypical genitalia, altered growth | AR | (76) | |

| #202110 | CYP17A1 | (77) | |||||

| Aromatase deficiency | #613546 | CYP19A1 | Androgen aromatization to estrogen | Pseudohermaphroditism in female infants, delayed bone maturation during childhood and adolescence, puberty with primary amenorrhea, failure of breast development, virilization, and hypergonadotropic hypogonadism | AR | (78) | |

| Congenital Disorders of Glycosylation | #212065 | PMM2 | Glycans or oligosaccharides synthesis and processing | Encephalopathy, psychomotor and growth retardation, cardiomyopathy, liver dysfunction, hypothyroidism associated with PA. PMM2 (*601785) occasionally described in isolated PA or SA |

AR | (79) | |

| Galactosemia | #230400 | GALT | Galactose metabolic pathway | Intellectual disability; developmental delay, PA with steak ovaries or few immature follicles | AR | (80) | |

AD, Autosomal Dominant; AR, Autosomal Recessive; PA, Primary Amenorrhea; SA, Secondary Amenorrhea; POI, Primary Ovarian Insufficiency.

The symbol # before OMIM entry number indicates that it is a descriptive entry, usually of a phenotype, and does not represent a unique locus. The symbol * before an entry number indicates a gene.

Table 3.

Proposed candidate genes for POI with still uncertain pathogenic roles.

| Gene | OMIM | Ovarian Phenotype (PA, SA, OD); other phenotypic anomalies | Inheritance (AD, AR, XLD) |

Prevalence | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AR | *313700 | PA, SA | XLD | 0.03% | (144) |

| BRCA1 | *113705 | SA | AD | 1.8% | (145) |

| EXO1 | *606063 | PA | AD | 2% | (146) |

| FANCM | *609644 | SA | AR | rare | (53) |

| GATA4 | *600576 | PA | AR | 0.1% | (53, 113) |

| GJA4 | *121012 | SA | AD | unknown | (53, 147) |

| INSL3 | *146738 | PA | AR | 0.02% | (53) |

| POLR3H | *619801 | PA, delayed puberty | AR | 1.5% | (53, 148) |

| PRDM9 | * 609760 | SA | AD | 0.4% | (53, 83) |

| PSMC3IP | *608665 | OD, PA, SA | AR | unknown | (120, 149, 150) |

| RAD51 | *179617 | PA | AD | 2% | (146) |

| SPATA22 | *617673 | SA | AR | 0.1% | (151) |

| STRA8 | *609987 | PA | AR | rare | (119) |

| WT1 | *607102 | PA, SA | AD, AR | 0.5% | (82) |

AD, Autosomal Dominant; AR, Autosomal Recessive; OD, Ovarian Dysgenesis; PA, Primary Amenorrhea; SA, Secondary Amenorrhea; XLD, X-Linked Dominant.

The symbol * before an entry number indicates a gene.

Table 2.

Classic candidate genes for POI.

| Gene | OMIM | Ovarian Phenotype (PA, SA, OD); other phenotypic anomalies | Inheritance (AD, AR, XLD) |

Prevalence | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMH | *600957 | SA | AD | 0.2% - 2.0% | (81, 82) |

| AMHR2 | *600956 | SA | AD | 0.8%– 2.4% | (81, 82) |

| ANKRD31 | *618423 | SA | AD | 0.3% | (83) |

| BMP15 | *300247 | PA, SA | XLD (dominant or recessive) | 0.4% – 12% | (81, 84) |

| BMPR1A | *601299 | SA | AD | unknown | (85) |

| BMPR2 | *600799 | PA, SA | AD | 1.4% | (81, 86) |

| DMC1 | *602721 | SA, DOR | AR | 2.4% | (87, 88) |

| ESR1 | *133430 | SA | AD | unknown | (89, 90) |

| FIGLA | *608697 | PA, OD | AR | 0.3-2.5% | (91–96) |

|

FMR1 premutation

(55 to 200 CGG repeats) |

*309550 | Intellectual and developmental disabilities associated with ovarian dysfunction; Fragile X-Associated Primary Ovarian Insufficiency (FXPOI) |

XLD | 2% in sporadic cases 14% in familial cases |

(97) |

| FOXO3A | *602681 | PA, SA | AD | 2.2% | (98) |

| FSHR | *136435 | OD, PA, SA with pubertal disorder, oligomenorrea | AR, AD | 0.1% – 42.3% | (81, 82) |

| GDF9 | *601918 | PA, SA, delayed puberty | AR, AD | 0.2% - 4.7% | (81, 99) |

| HFM1 | *615684 | PA, SA | AR, AD | 0.8-4.2% | (100–105) |

| INHA | *147380 | OD, PA, SA | AR, AD | 0% – 11% | (82) |

| LHCGR | *152790 | Delayed or absent menarche, SA | AR, AD | unknown | (106, 107) |

| LHX8 | *604425 | Primary infertility, SA | AD | 0.7% - 1% | (53, 108, 109) |

| MCM8 | *608187 | PA, SA | AR, AD | 1.25-2% | (104, 110–112) |

| MCM9 | *610098 | OD, PA, SA | AR, AD | 1.6-8% | (53, 111, 113–116) |

| MEIOB | *617670 | SA | AR | unknown | (117, 118) |

| MEIOSIN | n.d. | SA | AD | rare | (119) |

| MND1 | * 611422 | OD, PA, SA | AR, AD | unknown | (120) |

| MRPS22 | *605810 | SA, delayed puberty | AR | unknown | (121) |

| MSH4 | *602105 | OD, PA, SA, DOR | AR | 1.2% | (81, 121, 122) |

| MSH5 | *603382 | SA | AR | 0.6% | (81, 123) |

| NANOS3 | *608229 | SA | AR, AD | 0.5-2.5% | (124, 125) |

| NOBOX | *610934 | PA, SA (with or without delayed puberty) | AD, AR | 1.2% - 9% | (81, 126, 127) |

| NOTCH2 | *600275 | PA, SA | AD | 0.04% | (99, 128) |

| NR5A1 | *184757 | PA, SA, delayed puberty | AR, AD | 0.3% – 2.3% | (10, 81) |

| PGRMC1 | *300435 | SA | XLD | 2.0% | (53, 81) |

| REC8 | *608193 | SA | AR, AD | 1.25% | (114, 129) |

| SMC1B | *608685 | PA, SA | AD | 2% | (53, 129) |

| SOHLH1 | *610224 | PA, SA | AD, AR | 0.2% - 2.2% | (81, 130, 131) |

| SOHLH2 | *616066 | SA | AD | 1.9% | (53, 132) |

| STAG3 | *608489 | OD, PA | AR | unknown | (53, 105, 133–136) |

| SYCE1 | *611486 | SA | AR, AD | <2% | (101, 113, 137–139) |

| TP63 | *603273 | OD, PA, SA | AD | 3.75% | (140–143) |

AD, Autosomal Dominant; AR, Autosomal Recessive; DOR, Decreased Ovarian Reserve; OD, Ovarian Dysgenesis; PA, Primary Amenorrhea; SA, Secondary Amenorrhea; POI, Primary Ovarian Insufficiency; XLD, X-Linked Dominant.

The symbol * before an entry number indicates a gene.

3.1.1. Overview of genetic candidates and stages of folliculogenesis

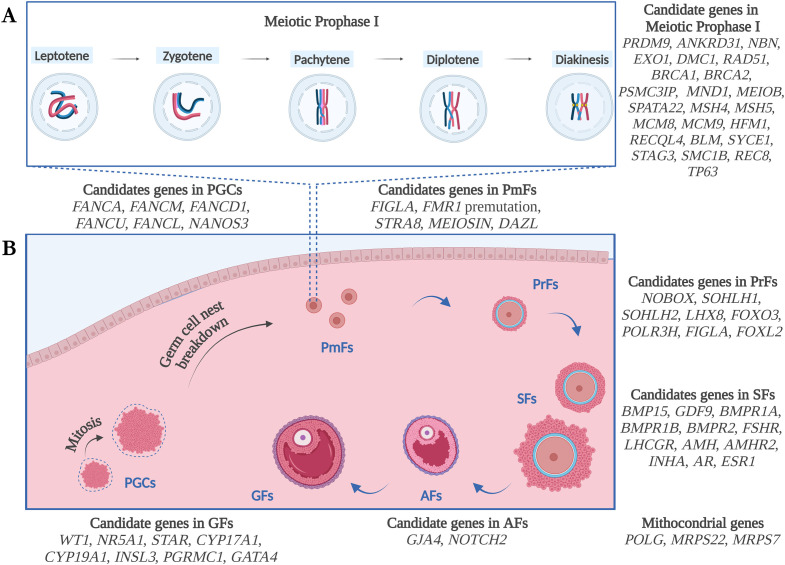

In this section, the main genetic factors involved in non-syndromic forms of POI will be described, according to the biological process in which each gene participates, based on literature findings. See also Figure 1 and Tables 1 – 3 for details.

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration of the genetic candidates for POI, according to the biological process of Meiotic Prophase I (A) and Folliculogenesis (B) and based on literature findings. PGCs, Primordial Germ Cells; PmFs, Primordial Follicles; PrFs, Primary Follicles; SFs, Secondary Follicles; Afs, Antral Follicles; GFs, Graafian Follicles. Figure created with Biorender.com.

3.1.1.1. Primordial germ cells and oogonia formation

Human primordial germ cells (PGCs) originate from the extraembryonic mesoderm 3 weeks after fertilization and migrate to the developing gonadal ridges, the bipotential gonads that will differentiate into either ovaries or testis. Here, female PGCs differentiate into oogonia and start proliferating in clusters of germ cells called syncytia or germ cell nests, which are connected and synchronized by intercellular connections. At this stage, an active phase of mitosis ensues to establish adequate ovarian reserve. During this phase of rapid proliferation, PGCs uphold genomic stability by crucially depending on precise DNA replication and repair mechanisms, which are tightly regulated through cell cycle blockades. The maximum number of oogonia resulting from mitotic divisions occurs approximately during the 20th week of development, with the ovaries containing approximately 6-7 millions of germ cells. A recent study in knockout mice (KO) indicated that defects of Fance may act during rapid mitotic periods in PGCs, leading to impaired cell proliferation and genomic instability. Through mechanisms not completely understood, Fance−/− mice showed reduced numbers of PGCs, decreased ovarian reserve, and infertility (152). In humans, previous studies have already shown that patients harboring biallelic pathogenic variants in genes such as FANCA, FANCM, FANCD1, FANCU, as well as those with monoallelic pathogenic variants in FANCA, FANCD1, FANCL, presented with gonadal dysfunction and infertility with or without other phenotypic features of Fanconi Anemia (74). During these early stages, mitotic oogonia expresses pluripotency-associated and germ cell-specific genes. Different groups identified NANOS3 genetic variants in patients with POI (124, 125). The NANOS3 gene is required for germ cell development coding an RNA-binding protein which functions by repressing apoptosis in germ cells. ATG7 and LIN28A are other essential genes involved in female gametogenesis considered candidates for POI, however, no significant variations were found in POI cohorts yet (153). ATG7 is an autophagy induction gene. Autophagy protects germ cells from over-loss in newborn ovaries. Loss of Atg7 leads to subfertility with a dramatic decrease of the ovarian follicles pool in female mice (154). LIN28A together with LIN28B encode highly conserved RNA-binding proteins regulating microRNA biogenesis by promoting germ cell proliferation and inhibiting differentiation (155); the disruption of Lin28a affects germ cell development in mice (156).

3.1.1.2. Primordial to primary follicles transition

Around the 11th week of gestation, the upregulation of FIGLA drives the formation of primordial follicles. Female mice Figla-/- exhibit impaired primordial follicle formation and infertility (157). Several deleterious variants of the FIGLA gene have been found in recent years by our group (91) and others (92–94). Each primordial follicle consists of an oocyte surrounded by a single layer of flattened somatic pre-Granulosa Cells (GCs) enclosed by a basal membrane which enters meiosis. The mechanism beyond the meiotic initiation is still poorly known. During human fetal ovarian development, increasing FMR1 expression marks the developmental transition from primordial germ cells expressing LIN28 to meiotic germ cells (158). The presence of the premutated FMR1 allele is frequently associated with ovarian dysfunction. FMR1 premutation is one of the most frequent alterations involved in the pathogenesis of SA and POI. Meiosin and Stra8 germ cell factors interact to trigger meiotic entry via the retinoic acid-dependent pathway, acting as transcription factors (159). Both STRA8 and MEIOSIN variants have been found to be associated with POI (160). Once meiosis proceeds, several genes are upregulated (161). Among these, Dazl protein mediates transcription of synaptonemal complex proteins (162). SNPs and rare genetic variants of this gene could associate with an earlier onset of menopause by impairing germ cells number (163, 164).

3.1.1.3. Meiotic phases

Key processes of prophase I are homologous chromosome pairing, synapsis formation, and repair of DNA Double Strand Breaks (DSBs) to enable recombination and crossover. The genetic disruption of either one of the meiotic genes leads to impaired meiosis progression and usually results in oocyte loss as shown in animal models thus making them candidates for human POI.

3.1.1.3.1. DNA double strand breaks formation

The precise localization and formation of DSBs are essential for the accurate recognition and pairing of homologous chromosomes. PRDM9 is a meiosis-specific histone H3 methyltransferase which catalyzes H3K4 trimethylation, binds chromosome axis by interacting with CXXC1, HORMAD1, MEI4, REC114, ANKRD31 and IHO1, and together with Hells opens chromatin at hotspots, thus providing the access for the DSBs machinery. Subsequently, the endonuclease SPO11, along with MEI1 and TOPOVIB-Like complexes, is recruited at PRDM9-binding sites where it generates chromosome breaks. Except for Cxxc1 and Hormad1, the conditional KOs of the above-mentioned factors demonstrate female mice infertility with premature oocyte loss caused by impaired DSBs formation (165). A few pathogenic variants in PRDM9 and ANKRD31 (83) have been identified in patients with POI so far. Up to date, no causative variants of POI have been identified in the other meiotic DSBs genes which are rather associated with male infertility (166) or other female fertility issues different than POI, such as preimplantation embryonic arrest and recurrent implantation failure and female infertility (167, 168).

3.1.1.3.2. DNA double strand breaks processing

Following the formation of DSBs, DNA ends undergo a maturation process which requires the tight cooperation of the MRE11-RAD50-NBS1 (MRN) complex. The relevance of the MRN complex in maintaining the primordial follicle pool has been demonstrated in animal models (169–171). In humans, biallelic nonsense mutations in the NBS1/NBN gene have been identified in compound heterozygosity in two siblings presenting the unique clinical symptom of fertility defects and POI (172). Then, the MRN complex recruits EXO1, an exonuclease which contributes to DSBs resection and formation of recombinant DNA structures and participates in mismatch repair. Inactivation of Exo1 in mice causes dynamic loss of chromosome chiasmata during the first meiotic prophase, leading to POI (173). Recently, WES performed in 50 sporadic patients with POI with PA identified in EXO1 gene one heterozygous missense variant impairing homologous recombination (HR) (146).

3.1.1.3.3. Synapsis generation

The 5’ to 3’ exonuclease activity of Exo1 generates long 3′ single-stranded tails, which serve as substrates for assembly of DMC1 and RAD51 recombinases. Both are necessary for strand invasion during synapsis formation (165). KO mice for Dmc1 show meiotic arrest at prophase I with ovaries devoid of follicles. Moreover, DMC1 genetic variants have been described in POI (87, 174). Recently, a report described a family with a homozygous frameshift mutation as causative for both non-obstructive azoospermia and diminished ovarian reserve, suggesting that DMC1 could be dispensable in human oogenesis (88). Contrarily, the lack of Rad51 in mice results in embryo lethality. WES in 50 sporadic patients with POI with PA identified a missense variation in RAD51 impairing the nuclear localization of this factor (146).

The nucleation and stabilization of RAD51 at DSBs are mediated by direct interaction with BRCA2 and BRCA1-BARD1 complexes (175). BRCA1/2 act as tumor suppressor genes known to predispose the heterozygous carriers of deleterious mutations to breast, ovarian and other types of cancers (176) Conditional Brca2-deficient mice exhibit infertility due to defective follicular development and oocyte degeneration, whilst BRCA2 transcript may be found downregulated in human POI oocytes (177). A few genetic studies contributed to the identification of pathogenic biallelic variants of BRCA2 in patients with POI in absence of cancer or Fanconi Anemia trait (75, 178), thus supporting BRCA2 haploinsufficiency as a possible mechanism leading to isolated POI (179). A tendency to accelerated decline of ovarian reserve, oocyte aging, and POI was also observed in patients carrying BRCA1 germline variants as well as in Brca1 mouse model (180).

Other regulating factors of RAD51-DMC1 are HOP2/PSMC3IP and MND1. They function as heterodimer which enhances strand exchange on homologous DNA or containing a single mismatch (181). Aberrant synapses and DSBs repair result from the loss of this complex (182). Both the ovarian phenotype displayed by KO mice and the identification of variants in patients corroborates their key role in oogenesis and POI pathogenesis (120, 149, 150, 183). Meiob and Spata22 form a complex recruited to induce DSBs. Inactivation of Meiob and Spata22 induces meiotic arrest and leads to infertility in mice (184). Variants of MEIOB and SPATA22 associated with POI are rare, with only 3 cases reported so far for MEIOB (117, 118) and only one for SPATA22 (151).

3.1.1.3.4. Homologous recombination

The heterodimeric complex MSH4-MSH5 stabilizes the interaction between parental chromosomes during DSBs repair (185). Disruption of either Msh4 or Msh5 genes in female mice results in infertility due to impaired and aberrant chromosome pairing, followed by apoptosis (186, 187). In the last years, WES in several POI pedigrees reported the contribution of MSH4 and MSH5 variants in the pathogenesis of POI. The recent identification of a digenic heterozygous variant in MSH4/MSH5 suggested that a dysfunctional interaction or cumulative haploinsufficiency of both heterodimer subunits, may disrupt HR during meiosis, finally causing POI (81).

MCM8 and MCM9 proteins form a hexameric ATPase/helicase complex which mediates HR repair (188). HR results impaired in both Mcm8 and Mcm9 KO mice, also presenting genome instability and being predisposed to develop tumors, suggesting a role in cancer development as tumor suppressor genes (189). Evidence for an association between variants in either MCM8 or MCM9 comes forth in genetic studies in POI families and worldwide cohorts of patients (110). Importantly, oncologic screenings are recommended in mutations’ carriers for prevention and early diagnosis (190).

Another helicase gene involved in the realization of crossing over is HFM1. In line with the observed phenotype of the Hfm1-/- mice, variations in the human gene can be causative for sporadic POI (100–105). Instead, variants in helicase genes, RECQL4 and BLM, which also participate in HR repair, have been identified in both Bloom and Rothmund-Thomson syndrome.

3.1.1.3.5. Synaptonemal complex and cohesins

The synaptonemal complex (SC) is a protein complex that forms a zip-like structure between homologous chromosomes during meiotic prophase I. Its primary function is to uphold the pairing of homologous chromatids, thus ensuring crossing over. The central structure of SC consists of transverse filaments, constituted by Sycp1, and central elements, including among others Syce1. Whereas SYCP2 and SYCP3 form the parallel lateral elements of SC. In patients with POI, except for variants identified in SYCE1 (101, 113, 137–139, 191, 192), no causative variations have been identified so far, although infertility has been described in animal models. Cohesins are proteins that directly associate with SC and ensure cohesion between sister chromatids. Some cases of POI have been associated with defective chromosomal cohesion due to variants in components of the ring-shaped protein structure made of cohesins. Cohesins core subunits may be meiosis-specific, such as STAG3, RAD21L, and SMC1B, or generic, such as SMC3 and REC8 (193). Pathogenic homozygous or compound heterozygous variants in STAG3 gene have been found in several POI pedigrees. Up to date, 22 variants in STAG3 have been reported in association with ovarian dysgenesis and PA, mostly with a predicted loss of function effect (53, 104, 105, 133–136). Variants in other cohesin genes have been firstly found for SMC1B and REC8, in heterozygosity, by a targeted NGS in 100 sporadic patients with POI (129). Accordingly, female mice KO for these cohesins are sterile with premature oocyte exhaustion and higher risk of developing ovarian tumors (Stag3-/-) (194) and early meiotic arrest (Smc1b-/- and Rec8-/-) (195, 196).

3.1.1.3.6. Dissolution of joint DNA intermediates

The dissolution of the SC takes place in the diplotene stage of prophase I, when recombined homologous chromosomes start separating except for the sites of crossovers. The joint DNA intermediates dissolution is executed by BLM helicase in complex with topoisomerase III alpha and other subunits. Genetic defects in this complex cause Bloom syndrome. Oocytes are then maintained at the diplotene stage for a prolonged period by high concentrations of cAMP inside the oocyte. During meiotic arrest, p63, a member of p53 transcription factor family, acts in maintaining the female germ line integrity. The alpha isoform is particularly expressed in oocytes of primordial and primary follicles in response to DNA damage and mediate apoptosis (197). The p63+/ΔTID transgenic female mice, in which the transactivation inhibitory domain of the protein is deleted, show rapid oocyte depletion through apoptosis after birth (198). Several variants located in the C-terminal region of the human TP63 gene have been found. Recently, our group contributed to identify an intragenic duplication paternally inherited in two sisters diagnosed with ovarian dysgenesis and PA (140). A few nonsense and missense variants were then reported in literature in isolated or syndromic POI families (141, 142, 199). More recently, heterozygous pathogenic single nucleotide variants and intragenic copy number variations of TP63 have also been described in sporadic patients with POI (143). All the identified variants are supposed to enhance oocyte apoptosis leading to premature depletion of the ovarian reserve, but further researchers may better elucidate the mechanism and pathways involved. Thereafter, through a still undeciphered mechanism, primordial follicles undergo growth and maturation, thus entering the growing pool of primary follicles (200).

3.1.1.4. Follicular growth and maturation

The primordial follicle cohort may have different fates: some remain quiescent and constitute the ovarian reserve, while the majority undergo atresia, either directly or after an initial recruitment and growth, but a smaller portion is activated and then develops until ovulation. In physiological conditions, during transition from primordial to primary follicles, the oocyte resumes meiosis and gradually increases in size, while the surrounding pre-GCs enters a proliferative and differentiated state (201). However, in some pathological situations and after exposure to chemotherapy or environmental chemicals, primordial follicle depletion may accelerate thus leading to POI (202).

3.1.1.5. Primary follicles development

In mammals, early follicular progression is carried on through PI3K/AKT/mTOR activation and PTEN inhibition: multiple players in these pathways have been identified although complete comprehension of these processes is still very limited, particularly in human (203, 204). In the oocyte, key events that trigger the development of primary follicles seem to be the activation of specific transcription factors, such as NOBOX and SOHLH1/SOHLH2 together with LHX8. KO mice of these genes present with hypergonadotropic hypogonadism: in female Nobox-/- fibrous tissues replace follicles (205), while in female Sohlh1-/- and Lhx8-/- infertility is respectively caused by gonadal dysgenesis (206), and early oocytes loss (207). Studies in mouse indicate that NOBOX, SOHLH1/SOHLH2 and LHX8 are co-expressed and cross-regulate each other, either directly or indirectly, thus controlling oocyte development during early follicular progression and therefore their mis-regulation leads to infertility (95). Differently to NOBOX and SOHLH1/SOHLH2, LHX8 and FOXO3 maintain primordial follicles quiescent and inhibit follicular development (208). FOXO3 is a substrate of AKT. In mice, Foxo3 deficiency prematurely activates dormant follicles in the pubertal ovary, while its constitutive expression delays oocytes and follicles development (209). NOBOX gene is considered one of the major genetic causes of POI (126), whose variations have a high incidence in woman from sub-Saharan Africa (210), while SOHLH1, SOHLH2, LHX8 and FOXO3 variants are rather uncommon (98, 105, 108, 130, 132, 211). Recent WES data in a cohort of women with infertility and oocyte maturation arrest, however, report the identification of 5 novel heterozygous loss of function LHX8 variants that produce truncated proteins (109). In turn, Foxo3a expression results diminished in mice with a homozygous point mutation in the Polr3h gene and characterized by delayed pubertal development. Remarkably, a pathogenic mutation in the POLR3H gene is described in two unrelated POI families, thus highlighting a new player in ovarian function and a new candidate gene (148). The continuous oocyte expression of FIGLA regulates the zona pellucida (ZP) genes, necessary for the production and assembly of an extracellular coat of glycoproteins which surrounds and separates the oocyte from the adjacent GCs, but allows the exchange of second messengers or small molecules through gap junctions (161, 212). At this stage, the ovarian follicle is defined a functional syncytium, that allows bidirectional communication between oocytes and GCs, and defects of ZP genes may results in female infertility in mice and humans (213). To support oocyte maturations, GCs first become cubically shaped and tight junctions appear. Then, GCs further enlarge and become stratified into multiple columnar cells, that progressively differentiate into internal cumulus cells (CCs) and external mural granulosa cells (MGCs), characterized by different metabolomes (214). FOXL2, a pleiotropic transcription factor with key roles throughout ovarian development, is critical in promoting differentiation and maintenance of GCs identity (215). Conditional loss of Foxl2 in mouse adult ovaries causes GCs reprogramming into testicular cells (216), and human FOXL2 variants have been associated with POI (81, 217). However, follicles result histologically mostly abnormal and atretic in POI, characterized by a partial or complete absence of GCs and, therefore, an important challenge today is to identify new players in GCs development.

3.1.1.6. Secondary follicles growth

Primary to small antral follicle transition depends on the oocyte production and secretion of two members of the transforming growth factor beta (TGFβ) family, GDF9 and BMP15. Evidence in natural and experimental animal models provide insight into their roles and demonstrate their oocyte-specific co-expression as cumulin (218). In particular, it has been reported that BMP15 is more relevant in mono-ovulating species (such as sheep and human) than in the poly-ovulating ones (mice) (5). In humans, mutations in BMP15 have been first found in association with hypergonadotropic ovarian failure characterized by ovarian dysgenesis (219) and from then on other variants have been identified worldwide (220–226). BMP15 maps on the Xp, in a locus critical for ovarian reserve determination, where several TS traits are located, including ovarian failure (227, 228). BMP15 as synergic heterodimer with GDF9 interacts with a tetrameric receptor complex on GCs formed by the kinase receptor BMPR2 and the ALK3 and ALK6 co-receptors, respectively BMPR1A and BMPR1B. BMPR2 variants are described in potential functional association with POI (106). A variant in BMPR1A was found to alter downstream signaling, possibly causing POI (85), whereas mutations in BMPR1B have been associated with some cases of non-syndromic POI, besides those with Demirhan syndrome (99). Upon binding receptors, cumulin triggers SMAD proteins phosphorylation cascade and promotes the transcription of GCs proliferation genes (229). One of the known downstream targets of cumulin is FSHR, which expression is essential for follicle growth and later estrogen secretion (230). Mutations in BMP15 or GDF9 may negatively affect the FSH signaling, arresting folliculogenesis and causing POI (231). FSHR genetic defects frequently alter ovarian development in women with highly variable POI clinical manifestations (PA to SA), depending on the degree of resistance to FSH action in granulosa cells (27). FSHR mutations lead to POI when both alleles are affected and represent the first genetic cause that was linked to POI in the Finnish population (232). Other TGFβ-like growth factors produced by GCs have instead inhibitory roles on follicles development, such as AMH and INHA. AMH is a secreted factor that can either interact with its receptor AMHR2, mainly expressed in the adjacent mesenchyme, or circulate and play a role in controlling the gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) in the hypothalamus (233). Amh mutant female mice show accelerated ovarian primordial follicle recruitment, despite morphologically normal ovaries, suggesting a suppressor role in regulating germ cell development. AMH expression in developing follicles is highly dynamic: it starts in primary follicles, increases in preantral and small antral follicles, and then decreases in pre-ovulatory follicles, but not in CCs. Polymorphisms in this gene are associated with the age at menopause (234) but are rarely described in patients with POI, similar to mutations in AMHR2 (235–237). INHA inhibits FSH production in the pituitary gland and genetic screenings in POI series revealed variations potentially associated (114, 238). Theca cells (TCs) originate from the ovary stroma, develop a blood supply and surround the follicle. TCs further differentiate into theca externa and interna, which develops LHCGR receptors and provide androgen hormone secretion. FSHR and LHCGR receptors are targets of the gonadotropins FSH and LHCG, respectively, both produced and released by the pituitary gland upon the hypothalamic stimulus. In turn, gonadotropin-dependent development allows the formation of antral and ovulatory follicles (239). LHCGR was among the first genes for which variations were related to POI (240), but its involvement in the pathogenesis of POI is rare. Female mice Lhcgr -/- are infertile with decreased estradiol and progesterone levels (241); however, after WT ovary transplantation, they can be fertilized (242). Women carrying homozygous pathogenic LHCGR variants usually exhibit normal secondary sex characteristics but may have delayed or absent menarche; however, heterozygous mutations might contribute to POI phenotype if combined with other genetic variants (106). Interestingly, infertile women carrying mutated LHCGR variants, coding for proteins with absent cell surface localization and signal transduction abilities, achieved successful oocyte retrieval and high-quality embryos leading to live births, indicating that LHCGR defects disrupt late folliculogenesis events and ovulation but have no effect on fertilization or embryo development (107).

Steroid hormone receptors, ESR1 and AR, are positive regulators of follicular maturation. ESR1 is a nuclear receptor expressed by TCs and GCs at this stage of follicular development, regulating growth and maturation to antral stage. Esr1 -/-mice present folliculogenesis blocked before antral formation or fail to ovulate and are infertile (243). Polymorphisms in ESR1 have been associated with increased risk of POI (89, 244). AR is present in GCs and its deficiency in female mice may lead to dysregulation of important genes involved in folliculogenesis causing a POI-like phenotype (245), but few mutations of this gene have been linked to POI so far (144, 246).

3.1.1.7. Antral follicles formation

Endocrine and paracrine factors from the hypothalamic-pituitary axis together with precise interactions among oocytes and GCs/TCs act in concert for antral follicle formation. Pre-antral follicles continue to extend their diameter, stimulated by FSH action and by the oocytes production of cumulin, and develop a fluid-filled cavity (antrum) with the oocyte eccentrically located in it. Simultaneously, oocyte further increases its volume, with cytoplasmic synthesis and accumulation of proteins, mRNAs, glycogen granules, ribosomes, mitochondria, and vesicles (161). Communication between the oocyte and GCs are facilitated by gap junctions, through which ions and small molecules pass mediated by Connexins, and filopodia-like structures with adherens junctions, where ligand-receptor interaction transduce the signal (i.e. KIT/KIT-ligand and Notch/Jagged) (247). Among connexins, GJA4 has a role in ovarian follicle development, and disruption of this gene in mice results in female infertility due ovarian folliculogenesis arrest at the preantral stage (248), but few variations have been reported in patients with POI so far (147). KIT-Ligand, a NOBOX target (249), activates the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/AKT pathway by interacting with its receptor (250). Variations in KIT/KIT-ligand cause ovarian insufficiency in rodents, but their role has yet to be elucidated in women affected by POI (53). Notch signaling regulates GCs proliferation (251): Jag1 ligand on oocyte interact with Notch2 and Notch3 receptors on GCs to activate the expression of target genes (i.e. Hey transcriptional repressors) (252). NOTCH2 variants have been identified through WES in patients with POI (99, 128), while the role of other Notch genes in POI is still unclear. antral follicles are the most susceptible to atresia and may degenerate after GCs programmed death throughout apoptosis, autophagy (253), and ferroptosis (254). Increased circulating FSH levels and a fine balance of stimulatory and inhibitory growth factors, such as IGF1 and TGFβ family members, direct follicles to either atresia or development until ovulation (4). In monovulatory species, after puberty, just one dominant follicle, although several antral follicles are recruited, undergoes final development and maturation during each reproductive cycle, in response to cyclic hormonal changes (255, 256). Growing evidence suggests roles of miRNA in gonadal development, regulating genes involved in folliculogenesis, ovulation and steroidogenesis (257), although their functions and regulatory mechanisms remain inadequately understood (258).

3.1.1.8. Ovulation and steroidogenesis

Ovulation is the fine-tuned remodeling process that ensures the follicle rupture when the uterus is receptive for embryo implantation. The dominant antral follicle rapidly grows to reach preovulatory stage (Graafian follicle) and produces higher levels of estradiol, that positively feedback to the hypothalamic-pituitary axis in a response required both for its further ovulatory process and for subordinate follicles growth inhibition after FSH levels lowering (259). Both FSH and estradiol signaling leads GCs to acquire LH receptors, thus the properly timed preovulatory LH surge from the pituitary gland activates the Graafian follicle and triggers a sequence of events that lead to ovulation: cAMP levels decrease in the oocyte with subsequent nuclear maturation (meiotic resumption), CCs mucificate and, at the end, oocyte-cumulus complex is released for fertilization while the remaining TCs and GCs of the ovulated follicle undergo dynamic transformation to become the corpus luteum, a progesterone producing structure needed for pregnancy (260). Conversely, inappropriate luteinization would impair follicle growth, reduce both the estradiol production in response to FSH and the negative feedback on ovary (261, 262). Previous studies provided evidence for the presence of luteinized Graafian follicles in the ovaries of women with karyotypically normal POI: in contrast with control population, in these cases a poor correlation between follicle diameter and serum estradiol levels and a failure in subsequent achievement ovulatory serum progesterone levels were found, suggesting that premature luteinization may be a major pathophysiological mechanism compromising follicle function in POI (263). However, the molecular mechanism underlying these pathophysiological processes are still unknown. The occurrence of luteinized Graafian follicles is the major source of the cyclic secretion of ovarian estrogens in women of reproductive age, in a joint two-cells system between TCs (that produce progesterone and precursor androgens under the control of LH signaling) and GCs (where FSH signaling regulates estradiol synthesis starting from androgens) (258). A recently identified player regulating this process of steroidogenesis is Epg5; its underproduction blocks autophagy in murine GCs and results in the accumulation of Wt1 transcription factor that finally leads to infertility (264). In humans, WES identified a rare WT1 loss-of-function variant in a non-syndromic POI patient (265), and NR5A1 is reported as a fundamental steroidogenic factor, whose variants were associated also with POI (81), either alone or in combination with other genetic variations (91). NR5A1 regulates the expression of STAR, CYP17A1, and CYP19A1 (266), whose variations have been reported in syndromic POI. Another player with a role in estrogen production, INSL3, has been identified as mutated in a Brazilian patient with PA (164); Insl3 mouse KO promotes follicle atresia and disruption of female cycle (267). Similarly, targeted Pgrmc1 deletion in GCs suppresses antral follicles development and increased atresia (268) but its variations are rarely found in patients with POI and more research is needed (269, 270). In vitro studies point to a role of GATA4 in ovarian steroidogenesis by impairing estradiol synthesis (271), and conditional knockdown of Gata4 in mice showed female infertility. Variation of this gene has been found in two patients (99, 164). Recent data report that ovulation is initiated in mice by Progesterone receptor induction in GCs, which cooperate with RUNX1 to reprogram chromatin accessibility and alter gene expression (272). Noteworthy, the first in vitro model of GCs has been generated from human induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs) after overexpression of NR5A1 and either RUNX1 or RUNX2; the procedure highlights the role of these transcription factors in folliculogenesis and is a central starting point in modelling several key ovarian phenotypes (273).

3.1.1.9. Mitochondrial contribution

Oocyte viability and follicle maturation notably rely on mitochondrial biogenesis and bioenergetics (274, 275) and are the central sites for steroid hormone biosynthesis. Their swelling has been linked to GCs apoptosis and follicles atresia and, consistently, variations in genes involved in mitochondrial functions are responsible for POI (276), mainly syndromic cases. Mitochondrial defects due to mutations in the polymerase pol domain of the nuclear POLG gene predispose to Progressive external ophthalmoplegia (PEO) associated with POI (50, 277). Variants in MRPS22 and MRPS7 are respectively reported in isolated POI and in a patient with failure of pubertal development and hypogonadism (121, 278). We previously reported that the premature impairment of the ovarian reserve is associated with a significant decrease in the number of copies of the mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) in blood cells and could then be considered a form of anticipated aging in which the ovarian defect may represent the first manifestation (279). The quantification of mtDNA in the peripheral blood could be used as a non-invasive biomarker for POI risk prediction (279, 280). The role of mitochondrial DNA content and of nuclear and mtDNA genes related to mitochondrial functions should be deepened with further investigations in larger populations, and with additional studies in model organisms.

3.2. Autoimmune causes

It is reported that autoimmune cover between 4 and 30% of POI cases (6, 281), however recent data suggest that number is closer to 4 to 15% (2, 282, 283). Dysimmune diathesis can be responsible for polyglandular diseases or result in oophoritis alone. Association with autoimmune diseases can be frequently found among women with POI (282, 284). The exact mechanism involved in the abnormal recognition by the immune system remains unknown, but both genetic and environmental factors are required for initiating the autoimmune response. The proofs for an autoimmune etiology are presence of lymphocytic oophoritis and associated autoimmune disorders (285), but this is not feasible in the clinical context. There are several reported target antigens involved in autoimmune oophoritis; importantly, among them, adrenocortical and steroidogenic autoantibodies, and in particular circulating 21-hydroxylase enzyme (21-OH-Ab), are recognized as the best markers of autoimmune POI (286, 287). A clear association between serum adrenal cortex autoantibodies and the presence of histologically confirmed autoimmune oophoritis was demonstrated (281). Between 2.5 and 20% of patients with POI result positive for adrenal autoantibodies, i.e. directed against the adrenal cortex (steroid cell adrenal antibodies, SCA-Ab) or the 21-OH-Ab (285). The other way round is also true, i.e. 10-20% of patients with Addison’s disease develop POI (6, 288). However, these antibodies are usually found in POI associated with autoimmune Addison’ disease, but they are not a frequent occurrence in non-adrenal autoimmunity or in isolated idiopathic POI (289). Anti-ovarian antibodies (AOAs) are found in 24-73% of patients with confirmed POI (285, 290), however, sources conflict in the accuracy of these findings and the exact prevalence remains unclear. Their role as a marker for POI is of no value due to the low specificity of existing tests leading to a high rate of false positive results and lack of validation (290). Autoimmune thyroiditis (defined as isolated finding of autoantibodies anti-thyreoperoxidase and/or anti-thyreoglobulin) appears be the most frequent pathology associated, with a percentage of patients suffering from clinical and subclinical hypothyroidism of 8-20% and up to 24% of POI cases, respectively (291). However, the prevalence of autoimmune thyroiditis in the female general population results nevertheless high, varying from 8.6% to 17.3% with prevalence increasing with age (292). Moreover, it is worth mentioning that a recent case-control study in 4302 euthyroid women with normal ovarian reserve and low ovarian reserve, had shown that among the whole population thyroid autoimmunity was not associated with low ovarian reserve but was significantly associated with overt POI in woman with TSH>2.5 mUI (293). Women with diabetes mellitus are also at higher risk of developing POI with an estimated prevalence of 2.5%. Therefore, fasting blood sugar or glycosylated hemoglobin can be recommended (2). POI has also been associated with numerous other disorders including rheumatoid arthritis, Crohn’s disease, myasthenia gravis, systemic lupus erythematosus, and multiple sclerosis (294). The different glandular diseases may then combine into different clinical and/or subclinical clusters, i.e. Autoimmune Polyglandular Syndromes (APS). In the specific case, patients with POI may fall into APS type 1, type 2 or type 3A in approximately 3% of cases (295). The APS type 1 typically develops in pediatric patients and is characterized by the presence of mucocutaneous candidiasis, Addison’s disease and hypoparathyroidism; auto-antibodies anti-steroidogenic cells can lead to lymphocytic oophoritis in 60% of cases. Type 2 APS is associated with Addison’s disease, type 1 diabetes mellitus, hypothyroidism (or Graves’ disease) and less frequently with POI (296). However, the causal association between autoimmunity and ovarian insufficiency remains difficult to establish, and the presence of autoimmunity (either clinically or biochemically) does not necessarily imply the autoimmune origin of the condition, also in view of the relatively broad prevalence of autoimmune disorders and the low specificity of autoantibody measurement. The autoimmune etiology of the POI can be consider substantiated in such case as the presence of adrenocortical and/or steroidogenic cell antibodies and autoimmune Addison’s disease (APS type 1 or 2), possible or probable in case of presence of autoantibodies and/or autoimmune disease other than autoimmune Addison’s disease (297). Interestingly, in terms of phenotype, it has been described that autoimmune oophoritis presents as a distinct clinical entity compared to women with idiopathic POI: the former were found to have significantly larger, and possibly multifollicular ovaries in association with elevated inhibin B values (281, 298).

3.3. Iatrogenic causes

Iatrogenic causes account for 6-47% of POI cases (2); they can in turn be distinguished into surgical forms, post-chemotherapy, or following radiotherapy (whether local or external, with exposures greater than 1 Gray). Also, common iatrogenic causes that lead to POI in the process of treating non-malignant gynecological diseases include uterine artery embolization and pelvic surgery for ovarian cysts, endometriosis, and ovarian torsion; in particular, it has been shown that excision of bilateral endometriosis can lead to POI in 2.4% of cases (299). Female survivors of childhood, adolescent, and young adult cancer, have an increased risk of POI, with a cumulative incidence of approximately 8% by age 40 years (300, 301). The effects of chemotherapy depend on the type, previous ovarian reserve, dosage, and age at administration (302, 303). Treatments with evidence of causing POI include alkylating agents in general, cyclophosphamide, procarbazine, and radiotherapy to which the ovaries were potentially exposed, in a dose-dependent manner (300, 304). Indeed, for at-risk pre- and peripubertal survivors the monitoring of growth and pubertal development and progression is strongly recommended. Whereas, for postpubertal women who were treated with alkylating agents and/or radiotherapy to which the ovaries were potentially exposed, is strongly recommended detailed menstrual history and physical examination, with specific attention paid to POI symptoms (300). Laboratory assessment should be performed only on the basis of clinical indication or when the patient desires valuation of potential future fertility, at least annually (300).

3.4. Other acquired causes

In 1% of the cases, POI may be related to toxic, metabolic or infectious causes (2). Regarding POI associated with a history of infectious diseases, there is some evidence to suggest that women affected with HIV experience menopause at an earlier age (305) and, although gonadal function is relatively understudied, data found that HIV-positive women were more likely to have lower levels of AMH, largely explained by lower CD4 counts (306). The parotitis virus that causes mumps and results in mumps oophoritis can lead to ovarian failure in 2-8% of cases; however, this tends to be transient in most affected women and normal ovarian function resumes after recovery (299). Anecdotal reports described other viral and microbial infections, such as tuberculosis, varicella, cytomegalovirus, malaria and shigella as causes of POI (2). Association with environmental and toxic causes is also described. Exposure to phthalates and bisphenol-A present in plastic production and other environmental pollutants has been suggested as a possible risk factor POI; these toxins have been shown to increase follicular depletion and accelerated atresia of preantral follicles resulting in an earlier onset of menopause (307). A 2024 meta-analysis described that environmental pollutants pose a serious threat to human and animal reproduction. Such substances, including persistent organic pollutants, heavy metals, phthalic acid esters, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, cosmetic and pharmaceutical products and cigarette smoke, are indeed significant risk factors for POI, with pooled OR of 2.331 (308). Also, preclinical studies speculated that environmental pollutants lead to POI via improper hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis functioning, changed follicular mRNA/hormones, reduced ovarian volume and obvious follicle atresia (308). Moreover, a relation between cigarette smoking and early menopause has been described, although no direct causal relation has been confirmed (295). However, women who are prone to POI should be advised to stop smoking (309).

4. Clinical presentation and diagnosis

Typically, POI may present as menstrual irregularities or secondary amenorrhea, associated with infertility and hypoestrogenism symptoms, such as hot flushes and night sweats, vaginal dryness and dyspareunia, diminished libido and sleep and mood disorder. They generally are more pronounced than those typical of climacteric, especially in acquired forms with sudden onset. In those cases with early onset it may occur as primary amenorrhea with varying degrees of pubertal development, eventually associated with gonadal dysgenesis. Associated symptoms and clinical findings can be variable due to intermittent production of ovarian hormones. In fact, it is worth emphasizing that it may be associated with intermittent resumption of ovarian activity in over 25% of women (310, 311). Estimates of the likelihood of spontaneous pregnancy vary widely in the literature, but from the available data it appears that about 5% of women with POI will conceive naturally. Most of these conceptions will occur within a year of diagnosis, but pregnancies have been reported many years later (312). Despite the clinical marks, studies report that up to 70% of women with POI have ovarian follicles remaining in the ovary (262, 263), one-half demonstrated ovarian follicle function and, remarkably, 16% of these women achieved an ovulation (263). From a biochemical point of view, POI results in hypergonadotropic hypogonadism, which represents the diagnostic cornerstone. European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology (ESHRE) guideline recommended that in case of oligo/amenorrhea for at least 4 months diagnosis is confirmed by two elevated FSH tests (>25 U/L), 4–6 weeks apart (309), performed on precocious follicular phase (day 2–3 of the cycle) if menstrual flows are still present. Elevated FSH must be associated with low estradiol level, to rule out the possibility of gonadotropins pre-ovulation peak. In addition, another useful marker is represented by the serum anti-Mullerian hormone (AMH) levels. It is a hormone produced by granulosa cells of growing follicles (<8 mm in diameter) (313, 314), whose concentration reflects the number of follicles remaining in the ovary (315). It has emerged as the current best biomarker of the primordial follicle pool constituting the ovarian reserve (316), and it is known that AMH declines before the menopause in advance of elevated FSH concentrations (317). AMH generally results in low/undetectable (318–320), although there are still no defined cut-offs for diagnosis (6). A small number of studies that have investigated the value of AMH in the diagnosis of POI, demonstrating a progressive decline in women across the stages of deteriorating ovarian function to POI, although data estimated that AMH is detectable in approximately 6% of the POI population (321–323). The largest study to date suggested that an AMH of ≤ 0.25 ng/ml (1.78 pmol/l) was diagnostic of POI with high sensitivity and specificity (323). Furthermore, it was reported that AMH concentrations were lower in women who experienced primary amenorrhea than in those with secondary amenorrhea (324). A transvaginal ultrasound scan can also be helpful in estimating ovarian status. The ovaries can be found to be compact and small, and up to 50% of primary amenorrhea cases may have gonadal dysgenesis with “streak” ovaries. However, as mentioned above, it is not uncommon to detect evidence of ovarian function (262) (pre-antral, antral follicles or pre-ovulation follicles and/or ovarian corpus luteum). Thus, ultrasound findings can be misleadingly reassuring regarding ovarian function and fertility prognosis (325), but may also be useful in revealing any remaining ovarian activity. Ovarian reserve can be assessed sonographically by antral follicle count (AFC), that would be expected to be low in POI and usually correlate with AMH levels. Occasionally relatively normal AFCs are seen despite low AMH levels, however, AMH appears to be a stronger predictor of ovarian response (316). Unfortunately, because of the above, when the biochemical criteria of POI are met, the ovarian reserve is found to be already substantially reduced or follicular dysfunction is present with impaired responsivity to FSH (262, 263), consequently, the chances of fertility preservation are severely diminished (323). For this reason, the identification of early diagnostic markers to identify women at high risk of developing POI, enabling effective fertility planning, is of great interest. However, while it has been postulated that AMH may be of value in assessing family members of a proband with POI (326), current evidence showed low discriminatory performance of AMH in menopause prediction in young women (316, 322, 327). Once the diagnosis of POI has been confirmed, it is important to carry out investigations to establish the origin of POI. After ruling out possible acquired causes by means of a thorough medical history, autoimmune and genetic causes should be sought in the first instance. ESHRE guidelines recommend routine screening for the presence of thyroid autoantibodies and 21OH-Abs in every case of POI. Screening for anti-ovarian antibodies is not recommended. Screening beyond Hashimoto’s and Addison’s diseases is not routinely performed (309). On the other hand, in patients with multiple autoimmune diseases or Addison’s disease it should be advisable to consider screening for early detection of POI. Also, measurement of fasting blood glucose or glycosylated hemoglobin levels should be performed (2).

4.1. Genetic diagnosis

Turner Syndrome (45,X), mosaicisms of X chromosome, the partial loss of critical terminal regions of the long arm of the X, and X-autosomal translocations are well-known chromosomal abnormalities causing POI that could lead to either primary or secondary amenorrhea (328). Besides, one of the major genetic alterations implicated in POI is being a carrier for the FMR1 gene premutation. In women, this condition defines a higher risk (>20%) of developing the premature exhaustion of ovarian function, which can also be associated with other symptoms (i.e. ataxia, psychomotor developmental disorders, and cardiovascular pathologies). Additionally, premutated alleles are mitotically and meiotically unstable and could lead to the expansion to full mutation allele during the maternal transmission and cause the Fragile X syndrome in male offsprings of the next generation. The prevalence of premutated FMR1 allele in the general female population is estimated to be around 1:250 and even higher among different ethnic groups (329). Investigating the FMR1 premutation is of primary importance in patients with POI because the chance of evolving to the full mutation (>200 repeats) in the subsequent generation is close to 100% for expansions >100 repeats (330). Fragile X syndrome is characterized by dysmorphism, severe intellectual disability and autism in males. Therefore, first-level tests for the clinical and genetic evaluation of POI are high-resolution karyotype (that we suggest as first-line genetic test in PA and in SA cases <30 years of age) on 2 independent cultures by analyzing at least 30 metaphases (at 400–550 band resolution), according to the International System of Chromosome Nomenclature 2020 (ISCN 2020) (331), which can be extended to 100 in case of mosaicism and eventually replicated on a cutaneous biopsy, and the molecular analysis of the FMR1 gene; its involvement is highly unusual in PA cases while more frequent in SA cases >25 years of age. In case of negative or uncertain results for both FMR1 and karyotyping, Comparative Genomic Hybridization arrays could be performed to identify undetected chromosomal duplications/deletions or low level mosaicism (<10%). The further genetic screenings should be guided by the presence of clinical features suggestive of a specific syndrome. In the absence of any syndromic phenotype, ad-hoc target Next Generation Sequencing (NGS) panels of candidate genes can be used to identify single nucleotide variants potentially pathogenic. Within the NGS strategies, the analysis of families with POI and large POI series through whole exome sequencing or whole genome sequencing can be used to identify new variants and novel genes involved in the pathogenesis of the disorder and their application is considerably improving our understanding of the molecular basis of ovarian functions and dysfunctions (332). NGS has shed light on the role of oligogenicity as a significant contributor to the genetics of POI (105, 332). Discerning true oligogenicity from digenicity or rare, potentially deleterious variants associated with POI remains a significant challenge. Oligogenicity refers to the involvement of multiple genes in a phenotype, while digenicity specifically involves interactions between two genes. In the context of POI, understanding these genetic complexities is crucial for accurate diagnosis and counselling. Another significant challenge in the genetic diagnosis of POI is the huge number of variants of unknown significance that emerge from NGS. It is likely that several heterozygous VUS can predispose to POI in the context of an oligogenic or multifactorial origin. In the future, efforts should be directed toward a more precise genotype-phenotype correlation and the resulting causative relevance. These challenges are further complicated by the complex gene network involved in POI, as well as the environmental component. Further, in the same family, the occurrence of members affected by POI or early menopause could be observed, due to incomplete penetrance. Investigating the genetics of the pathogenesis of POI is essential to deepen ovarian physiology and to solve the pathogenic mechanisms involved. As we uncover novel pathogenic variants, genetics can serve as valuable tools for precise diagnosis, predicting POI risk in families, and furnishing improved genetic and reproductive counselling that help women to plan their fertility.

5. Clinical management and long-term consequences

POI has a multisystem impact with profound physical and emotional implications; as such, its optimal management should be handled by a multi-disciplinary team. Of course, the effects of the condition on quality of life depend on the age of onset, the underlying cause and inter-individual variability. Age at menopause has been shown to have an additive effect on all-cause mortality and an independent predictor of subsequent cardiovascular outcomes (333–336). In particular, regardless of etiology, POI increases the long-term risk for cardio-metabolic disease (337): in this metanalysis emerges that compared to women with menopause at age >45 years, women with POI had a higher risks of type 2 diabetes (RR: 1.32, 95% CI: 1.08–1.62), hyperlipidemia (RR: 1.21, 95% CI: 1.05–1.39), coronary heart disease (RR: 1.52, 95% CI: 1.22–1.91), stroke (RR: 1.27, 95% CI: 1.02–1.58) and total cardiovascular event (RR: 1.36, 95% CI: 1.16–1.60). In fact, hypoestrogenism exerts several deleterious effects on many contributor factors, including lipid profile, insulin resistance, centripetal obesity, chronic inflammation, hypertension, vasoconstriction, endothelial dysfunction, and autonomic nervous system dysfunction. It is interesting to note that in this large Chinese study (338)the Authors found that POI increased the risk of total and cancer-specific mortality (HR (95%CIs): 1.29 (1.08–1.54) and 1.38 (1.05–1.81), respectively), while decreasing incidence of breast cancer (OR (95%CI): 0.59 (0.38–0.91)), but they didn’t find any statistically significant association of POI with either mortality or morbidity related to CVD. Similar results were observed when HRT users were excluded from the analysis Nonetheless, in many of the reported studies women who used or had used HRT were excluded from analysis or data on HRT use was not available. Thus, data are lacking to demonstrate whether the results were independent of HRT. However, cardiovascular protection seems to be related to exposure time (339), with the greatest reduction in CVD incidence in women who used HRT for at least 10 years and within 1 year of diagnosis (336), and type of HRT (340). Given the well-characterized cardiometabolic and bone impact of POI, optimal management of this condition should include baseline assessment of insulin resistance and lipid profile. Monitoring of these parameters should be dependent on comorbidity, personal and family history; however annual assessment of cardiovascular risk markers may be appropriate, although evidence on cost-effectiveness is currently lacking (6).