Abstract

Abstract

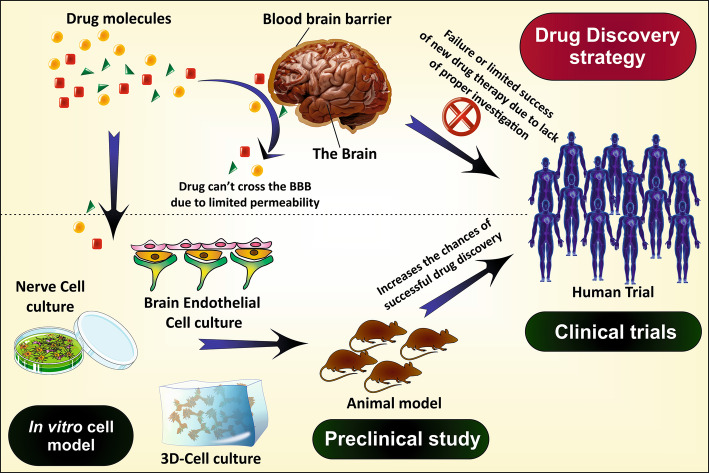

Globally, the central nervous system (CNS) disorders appear as the most critical pathological threat with no proper cure. Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is one such condition frequently observed with the aged population and sometimes in youth too. Most of the research utilizes different animal models for in vivo study of AD pathophysiology and to investigate the potency of the newly developed therapy. These in vivo models undoubtably provide a powerful investigation tool to study human brain. Although, it sometime fails to mimic the exact environment and responses as the human brain owing to the distinctive genetic and anatomical features of human and rodent brain. In such condition, the in vitro cell model derived from patient specific cell or human cell lines can recapitulate the human brain environment. In addition, the frequent use of animals in research increases the cost of study and creates various ethical issues. Instead, the use of in vitro cellular models along with animal models can enhance the translational values of in vivo models and represent a better and effective mean to investigate the potency of therapeutics. This strategy also limits the excessive use of laboratory animal during the drug development process. Generally, the in vitro cell lines are cultured from AD rat brain endothelial cells, the rodent models, human astrocytes, human brain capillary endothelial cells, patient derived iPSCs (induced pluripotent stem cells) and also from the non-neuronal cells. During the literature review process, we observed that there are very few reviews available which describe the significance and characteristics of in vitro cell lines, for AD investigation. Thus, in the present review article, we have compiled the various in vitro cell lines used in AD investigation including HBMEC, BCECs, SHSY-5Y, hCMEC/D3, PC-2 cell line, bEND3 cells, HEK293, hNPCs, RBE4 cells, SK-N-MC, BMVECs, CALU-3, 7W CHO, iPSCs and cerebral organoids cell lines and different types of culture media such as SCM, EMEM, DMEM/F12, RPMI, EBM and 3D-cell culture.

Graphical Abstract

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, In vitro cell line, BCECs, HBMEC, SK-N-MC

Introduction

AD is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder, considered as a prime cause of dementia which affects the routine activity and daily life of the patient. The statistics show more than 5.4 million cases of dementia only in the USA in the year 2016 (Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and Figures 2017; Agrawal et al. 2018a) from which AD accounts for about 50–75% of all. In 2016, globally 47 million people have dementia which was supposed to rise by three folds till 2050 (Martin Prince et al. 2016; Alladi et al. 2010; Anand et al. 2017). AD affects various functions of the brain like memory, cognition, behavior, and learning abilities, regulated through the entorhinal cortex, hippocampus, frontal, parietal, and temporal lobe of the brain (Kumar et al. 2015; Giacobini 1994; Wood et al. 2005). The formation of β-amyloid (Aβ) plaques and hyperphosphorylated τ-protein tangles are the pathological hallmarks of AD resulting in degeneration of neurons or affecting the neurotransmission (Agrawal et al. 2018a). Depending on the age of onset, AD is of two types: early-onset AD (EOAD) and late-onset AD (LOAD). EOAD is generally associated with mutations in presenilin and APP genes, while LOAD, mainly associated with the constant weakening and damage of nerve cells and brain function with aging (Szigeti and Doody 2011; Davis and Laroche 2003). LOAD is primarily characterized by amnesia, while EOAD, associated with visuospatial and motor dysfunction (Tellechea et al. 2018; Kupershmidt et al. 2012).

The brain remains the most vital organ of our body processing all the information, memory, coordination, voluntary and involuntary actions—the human brain composed of three prime regions including cerebrum, cerebellum, and medulla oblongata. AD primarily affects the cerebrum, further divided into occipital, temporal, parietal and frontal lobes (Arshavsky 2014). The loss of memory and cognitive functions are the primary features of AD which are due to neuronal degeneration in the temporal lobe (hippocampus) and frontal lobe, respectively (Agrawal et al. 2018b). In later stages, it affects another region of cerebrum responsible for vision (occipital lobe) and motor function (parietal lobe) (Arshavsky 2014; Hyman 1997).

Blood–Brain–Barrier (BBB) along with the vascular system acts as a shield to the central nervous system (CNS) preventing the entry of various harmful substances (Boursereau et al. 2015; Agrawal et al. 2017). Being highly lipophilic, it restricts the entry of hydrophilic molecules and allows the passage of specific lipophilic substances via passive diffusion. Although, it permits the transfer of some tiny hydrophilic particles through the small gaps of tight junctions (TJs) (Agrawal et al. 2017, 2018b). Small hydrophobic gases like O2 and CO2 can diffuse freely across the barrier. In addition, the paracellular pathway relies on the concentration gradient and permeability of the compounds, thus restricting macromolecules. The TJs are the essential characteristic feature of BBB which holds the brain capillary endothelial cells tightly to maintain the strength of the BBB (Jiang et al. 2007). There are mainly three TJs proteins, claudins, occludins and junctional adhesion proteins which can use as biomarkers to examine the BBB integrity (Wolff et al. 2015). BBB primarily consists of five types of cells; astrocytes, endothelial cells, pericytes, neurons, and microglia collectively called the neurovascular unit. Endothelial cells act as the central basal membrane part of the BBB lining. Astrocytes release several chemicals that retain and increase the strength of the barrier. Usually, in the in vitro cell culture, astrocytes are co-cultured along with endothelial cells to increase the TJs complexity and transendothelial electrical resistance (TEER) value (Zhang et al. 2010). Pericytes are also crucial in maintaining the integrity of BBB. Their absence results to increase the permeability of BBB by inhibiting the expression of TJ proteins (Keaney and Campbell 2015). In all, the BBB creates a significant hurdle for a drug to reach the brain and this becomes a massive challenge for the researchers. Hence, a proper understanding of the BBB is essential to develop a potential AD therapy.

For the establishment of any new therapy, scientists need some in vivo tools like animal models or postmortem brain (preclinical study), to evaluate the efficacy of the therapy. These tools are presently very popular in scientific interventions. However, the success rate is abysmal as it is challenging to replicate the exact state of AD as in the human body because of physiological, pathological and genetic difference between human and the animal (Cundiff and Anderson 2011; Dohgu et al. 2004). In addition, it is difficult to arrange or to work on the human brain. Moreover, the in vivo animal studies are very expensive, complicated and have some ethical issues (if excessively done). Thus, to overcome these hurdles nowadays in vitro studies are being carried out which mimic the condition of AD to a greater extent. The combination of both the in vivo and in vitro models offers a more promising way to investigate the disease pathophysiology, associated factors, disease progression and potency of the therapy. The advantages and limitations of the in vitro cell models used to study the human brain, neurodegenerative disorders, and screening of therapeutics are discussed in Table 1. In this review article, we have discussed the histopathological factors of AD and the in vitro cellular models used for understanding the disease initiation, progression and mechanism and in drug discovery and development process for AD.

Table 1.

Advantages and limitations of in vitro cell models used to investigate AD pathophysiology, disease progression, and drug screening

| Advantages | Limitations |

| It provides a relatively simple, less invasive and economical method to recapitulate different parts of the human brain, nerve cells and BBB (Gumbleton and Audus 2001) | It just provides a primary tool to investigate the disease pathology and drug screening and give a supportive direction for further in vivo and clinical investigations (Arber et al. 2017) |

| It offers a potential means to investigate various drug diffusion process across the BBB including the paracellular and transcellular drug diffusion, active transport and metabolism (Zhang et al. 2014a) | The immortalized in vitro cell line mostly fails to recreate the perfect paracellular barrier for investigation of drug permeability (Gumbleton and Audus 2001) |

| It demonstrates the undefined interaction of cellular material and drug which cannot be studied by in silico techniques (Gumbleton and Audus 2001) | It cannot fully recapitulate the microarchitecture and all the cellular functions of the organ (Wang 2018) |

| The primary culture of BCEC more prominently resembles the in vivo cells (Gumbleton and Audus 2001) | Among all the available in vitro models, no one can correctly reiterate all the cellular mechanisms including cell interactions, toxicity, response to drug, metabolism, etc. (Ghallab 2013) |

| The amyloidogenic response of rodent model differs from the human brain in such condition the iPSC and hESC (human embryonic stem cell) derived BCEC and nerve cells more prominently recapitulate the AD brain condition (Carolindah et al. 2013; Sullivan and Young-Pearse 2017) | |

| The patient-derived iPSCs and 3D cerebral organoids offer a more precise way to recapitulate the human brain and disease progression, as it is originated from the human cell (Poon et al. 2017) |

Pathophysiology of AD

Amyloid Cascade Hypothesis and APP (Amyloid Precursor Protein) Processing

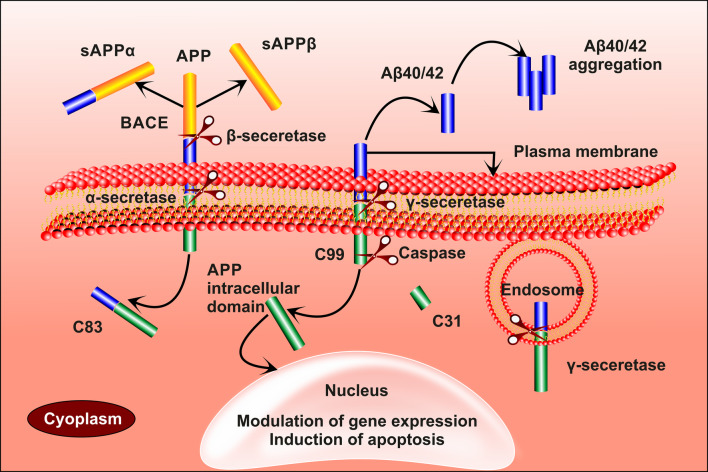

APP gene situated on chromosome 21 gets decoded to form APP. It is a transmembrane protein with a glycosylated N-terminal and a C-terminal projecting out and into the cell, respectively (Fig. 1). APP gets cleaved by three secretase enzymes, namelyα, β and γ. N-terminal of the protein gets cleaved by α-secretase to form sAPPα (secreted APPα), leaving behind the C-terminal with 83-amino acids (Musardo and Marcello 2017). Similarly, β-secretase also act on the N-terminal forming sAPPβ and 99-AA C-terminal. The formed 99-AA C-terminal gets cleaved by γ-secretase at the transmembrane regions producing Aβ 40 (soluble) or 42 (insoluble) and C-terminal. The remaining internal domain migrating to the nucleus regulates the expression of genes. Sometimes the 99-AA C-terminal gets cleaved by caspases resulting in the production of the neurotoxic peptide (31AA C-terminal) (Mattson 2004; Maloney and Bamburg 2007b). Aβ 40 is a soluble form of amyloid β peptide, cleared through the BBB. The insoluble Aβ42 forms small aggregates which further converted into the harmful plaques (Table 2). The Aβ aggregate causes an imbalance in calcium homeostasis and reactive oxygen species (ROS) (Bachmeier et al. 2011; Martins et al. 1991; Maloney and Bamburg 2007a). It is also found to alter the physiology of mitochondria by enlarging the size of mitochondrial transition pores and sometimes even causes the apoptosis of mitochondria (Kumar and Singh 2015).

Fig. 1.

α-secretase and β-secretase acts on APP to form sAPPα and sAPPβ leaving aside the C-83 and C-99 amino acid terminal aside, respectively. C-99 is acted upon by γ-secretase forming Aβ-40/42 and an internal domain which migrates to the nucleus causing gene expression. In some instances, C-99 is cleaved by caspases to form C-31, which is a neurotoxin

Table 2.

Etiological factors and enzyme activity responsible for AD progression

| S. no. | Etiological factor | Protein | Enzyme | Proteolytic products | Behavior |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Amyloid cascade hypothesis | APP | α-secretase | sAPPα | Promote neurite outgrowth and improves memory (Chow et al. 2010) |

| 2 | β-secretase | sAPPβ | Activate death receptor 6 (DR6), induce axonal disintegration (Kwak et al. 2006) | ||

| 3 | α and γ-secretase | Aβ17–40/42 | Amyloid plaque formation (Wei et al. 2002) | ||

| 4 | β and γ-secretase | Aβ1–40/42, Aβ11–40/42 | Amyloidogenic (Barritt and Viles 2015; Schmidt et al. 2009) | ||

| 5 | Caspase-3 | C31 | Neurotoxic (Zhang et al. 2011) | ||

| 6 | Tau Hyperphosphorylation | Tau protein | Caspase-3 and 7 | N-terminal fragment | Inhibit ROS production, participate in intrinsic apoptosis (Brentnall et al. 2013) |

| 7 | Calpain | Multiple curtailed species | Production of neurotoxic tau fragment (Ferreira and Bigio 2011) |

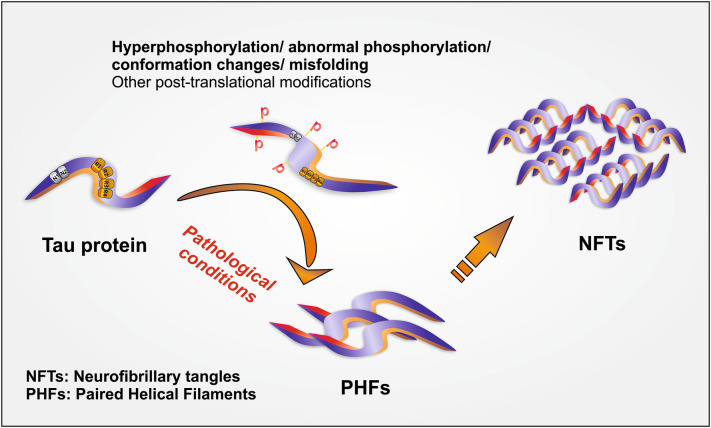

τ -Protein

τ-protein is a microtubule-associated protein which stabilizes the structure of nerve cell (Mandelkow and Mandelkow 2012). In AD there is an imbalance between kinases and phosphatases enzyme leading to the detachment of τ-protein with microtubule, thereby disturbing the structure of the cell which further promotes the aggregation of τ-protein (Kalra and Khan 2015; Blennow et al. 2001). This results in the formation of neurofibrillary tangles (a dead/collapsed neuron). Neurofibrillary tangles (NFT), the hallmarks of τ-protein pathogenesis in AD occupy the space present in the perinuclear cytoplasm of cortical pyramidal cells. NFTs, are formed by aggregation of paired helical filaments (PHFs) (Fig. 2; Table 2) (Wischik et al. 2014; Jouanne et al. 2017; Iqbal et al. 1994). The aggregates of τ-protein are notorious for declining the activity of proteasome leading to cell death by the atypical accumulation of proteins and also initiates subsequent cascade reactions. It also activates immune responses by activating microglial, and astrocytes thus favor the development of neuroinflammation (Laurent et al. 2018).

Fig. 2.

Formation of neurofibrillary tangles of τ–protein (1) hyper-phosphorylation/ misfolding/conformational changes in τ protein leading to club formation forming paired helical filaments (PHFs). (2) PHFs aggregate to form neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs)

Cholinergic Hypothesis

The depletion of acetylcholine (ACh) is one of the primary cause of AD which results in loss of cognitive functions and memory impairment. The reduction in ACh level is the consequence of the gradual death of cholinergic neurons in basal forebrain and collapse of neurotransmission in the cerebral cortex and hippocampus (Martorana et al. 2010). The downfall of neurotransmission is due to the damage of cholinergic nerve synapse by Aβ oligomers, formed in the early stages of AD (Ferreira-Vieira et al. 2016).

Mitochondrial Cascade Hypothesis

This hypothesis mainly has three postulates first, the tolerability of individual mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) over the produced ROS; second, the decrease in the mitochondrial functions is interrelated with aging and environmental factors and third, the changes in mitochondrial function with progressing AD (Swerdlow et al. 2014). These three factors affect the functioning of mitochondria by damaging mtDNA resulting in apoptosis or destructive mitochondrial electron transport chain (ETC). It increases the ROS levels, causing oxidative stress in plasma membrane inducing the soluble Aβ to adopt insoluble conformation (Swerdlow and Khan 2004).

Excitotoxicity

Glutamate, the primary excitatory neurotransmitter involved in the memory and learning functions that are affected in AD. Glutamate receptors are of two types: ionotropic (NMDA) and metabotropic receptors (G-coupled). Neurodegeneration generally saw in later stage due to the toxic effects of glutamate mediated by Aβ. Aβ interferes with excitatory amino acid transport (EAAT) and NMDA receptor (NMDA NR2α) thereby, blocking the uptake of glutamine (Mehta et al. 2013). Thus, the excess glutamine present in the synaptic cleft activates the extra-synaptic NMDA receptors (NMDA, NR2β) thereby, reducing the intracellular release of calcium ion and leading to activation of pathogenic pathways like hyper-phosphorylation of τ-protein (Esposito et al. 2013).

Genetic Factors

Presenilin

Presenilin-1 (PS-1) and Presenilin-2 (PS-2) are the homologous proteins obtained from PSEN-1 gene present on chromosome-14 and PSEN-2 gene on chromosome-1, respectively. It plays a vital role in the formation and activity of the γ-secretase enzyme (Cacquevel et al. 2012). The mutations in PSEN-1 & 2 affects the functioning of PS-1 & 2 causing overexpression of γ-secretase resulting in producing abnormal quantities of Aβ. The mutations in PS-1 and PS-2 are mainly involved in LOAD and EOAD, respectively. Mutations in PS-1 alters the calcium channel in glutamatergic neurons (Salek et al. 2010).

ApoE

ApoE is an essential lipid carrier responsible for the transfer of lipid in the brain and also involves repairing injuries. ApoE exists in allelic forms such as E2, E3, and E4, among these the E4 alleles, are more prone to develop AD. The ApoE4 facilitates the formation of Aβ42 or assists the Aβ aggregation and also decreases the Aβ clearance rate (Liu et al. 2013). It affects the extracellular Aβ degradation by reducing the expression of insulin-degrading enzyme (IDE) in the brain (Kanekiyo et al. 2014) which may lead to neurodegeneration.

Other Associated Factors

Oxidative Responses

The production of ROS is common in cells, responsible for aging and related disorders. Our body has a proper defensive mechanism which minimizes the oxidative stress-induced diseases. In AD-like condition, the natural defense mechanism becomes poor and results in uncontrolled ROS generation (Butterfield et al. 2006; Zhu et al. 2005). The increased amounts of ROS induced overproduction of Aβ, increasing the expression of β and γ-secretases, destroying the mtDNA, and altering the metabolism of metals and lipids. The relation between the Aβ and ROS is vivid because the overproduction of either of the one initiates the production of the other. These factors lead to the formation of Aβ aggregation, hyperphosphorylation of τ-protein, finally leading to apoptosis (Tonnies and Trushina 2017; Mark et al. 1996).

Immune and Inflammatory Mediators

In the brain, the immune and inflammatory mediators, produced in response to the neural infection or trauma. Astrocytes and microglial cells play a significant role in releasing the mediators. The activation of astrocytes releases the cytokines, proinflammatory mediators and cyclooxygenase which activates microglial cells (COX-1). The activated microglial cells may become phagocytic which removes infectious organisms or dead cell debris or may produce subsequent inflammatory mediators (Zhao et al. 2018). Some studies revealed that these cells abundant around the Aβ-aggregates/plaque. The released mediators may cause synaptic dysfunction, apoptosis or necrosis of neurons, astrocytes, and microglia (Morales et al. 2014).

Environmental Factors

Environmental factors contribute to about 30% risk of acquiring AD. It includes the exposure of various metals (copper, aluminium), pesticides (organophosphates), chemicals from industries (bisphenol A), air pollutants and antimicrobial agents (polychlorinated organic compounds). Each factor act in a different way for example copper stimulates the Aβ plaque formation, aluminum increases the oxidative stress, air pollutants like CO, NO, and SO2 increases the production of ROS, antimicrobials alter the immune response, and pesticides cause neurotoxicity or change the cell signaling (Yegambaram et al. 2015).

Aging

Aging may promote the risk of AD through the mitochondrial pathway, where there is a decrease in the functioning of mitochondria production of ROS, leading to a decline in pathological conditions. However, the deterioration of mtDNA upon aging may lead to apoptosis. The target of rapamycin (TOR) regulates protein homeostasis which inhibits autophagy and translation of mRNA. Decreased TOR signaling was observed to reduce the formation of toxic aggregates and decline the progression of AD (Perry et al. 2000). However, cells with defective autophagy shown to accumulate aggregates of Aβ. It observed that upon aging signaling of insulin-like growth factor (IGF-1) decreases which leads to the formation of toxic aggregates and further causing cytotoxicity (Bishop et al. 2010).

Methodology

For the compilation of this review article, we have conducted an exhaustive literature survey, and the data is collected using the two very popular search engines, ‘SCOPUS’ and ‘PUBMED.’ For more precise search results, the keywords remain defined by Boolean operators. The data collection was done using various set of keywords including; (Alzheimer) AND (BBB) OR (cell line) OR (v cell model) OR (pathology) OR (Culture media) AND (BCECs) OR (HBMEC) OR (SHSY-5Y) OR (hCMEC/D3) OR (PC-2 cell) OR (bEnd3 cell) OR (hNPCs) OR (RBE4 cell) OR (SK-N-MC) OR (BMVECs) OR (CALU-3 cell) OR (7W CHO cell) OR (standard culture medium) OR (Eagle’s minimal essential medium) OR (DMEM/F12) OR (RPMI media) OR (endothelial cell basal medium) OR (3D-cell culture) OR (patent). The data search takes place till 19th June 2018. At the same time no particular filter of the period, source, type of article was applied at the time of data collection. Finally, the collected data, segregated into different categories including the introduction of AD, pathology of AD, in vitro cell models and culture media, to finalize the structure of the article. The discussion section mainly based on the origin/source of the cell line, its isolation procedure, fundamental properties, culture media and environmental condition, merits, and demerits of the particular cell lineage. We have also tried to provide a graphical description and tabular data wherever possible; all the figures were prepared initially using COREL DRAW software.

In Vitro Cells

The development of effective therapy for the treatment of AD needs a complete and thorough understanding of the AD etiology. Immense research work has been already done and/or under progress to study the pathologies behind the disease including amyloidogenesis and neurodegeneration due to tau hyperphosphorylation. Unfortunately, the success rate is not satisfactory because of the limited availability of in vivo and in vitro models which reiterate the human brain anatomy and physiology (Arber et al. 2017).

In general, the animal models are popularly used to study the effect of drugs and human brain pathophysiology (Epis et al. 2010). However, they are unable to replicate the exact scenario like the human brain because of the physiological and genetical differences. The human brain can only be used to study the mechanism of progression of AD but, the main problem is that the brain is available just after post-mortem, that too, at the last stage of AD which also decreases the scope of disease progression study. In this context, the in vitro cellular models remove such obstacles and provide an attractive method to study the etiology of neurodegenerative disorders including AD. Therefore, the use of in vitro cell models is increasing day by day to enhance the translational value of in vivo models (animal model) and provide a deep understanding of invaluable mechanistic insights of the disease (Poon et al. 2017). Different cellular models used in AD research are discussed below (Table 3).

Table 3.

Specification of cell lines that make them useful as in the in vitro neuronal model, along with their isolation process, culture medium and uses

| In vitro cell line | Cell specifications | Isolation process | Culture medium | Uses/studies conducted | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

HBMEC (Human brain microvascular endothelial cell) |

Expresses tight junction protein transporters, and efflux pumps TEER value 100 Ω.cm2 increases to 2000 Ω.cm2 when cultured with retinoic acid |

Derived from hiPSCs or the human brain tissue | EMEM |

Used to study CRP (C-reactive protein) level in human serum and its synthesis through brain endothelial cells To study the effect of CRP level on AD progression To study the nanomolar aluminum sulfate on CRP expression It expresses tight junction proteins like claudin-5, occludin, ZO-1, and VD-cadherin Recapitulate BBB |

Alexandrov et al. (2015), Katt et al. (2016) |

|

BCECs (brain capillary endothelial cell) |

They are of animal origin, possess high TEER value | Isolated from microvessels of the brain of animals like a rat, mice or rabbit, etc. by dissection | DMEM/F12 |

To study the permeability properties and cytotoxicity of drugs and Aβ on BBB To create protein factories by genetic modification To study α, β and γ secretase activity in APP processing |

Burkhart et al. (2015), Zandl-Lang et al. (2018) |

| hCMEC/D3 (human cerebro microvascular endothelial cell) |

Tumorous cell lines Expresses the protein transporters and the BBB receptors Possess shallow TEER value |

Derived from microvessels of the human temporal lobe. Later, immortalized by SV40 large T-antigen | EMEM |

Used mainly in the studies related to cerebral endothelium Mechanisms relating to Aβ and cytokines |

Weksler et al. (2013), Biemans et al. (2017) |

| BMVECs (brain microvascular endothelial cells) | These cells exhibit similarities with that of BBB by possessing TJ-proteins etc |

Isolated from the temporal cortex of the human brain The obtained cells are converted into immortal cells by SV40 antigen |

DMEM/F12 |

Used in the study of mechanisms that alter the integrity of BBB To screen the passage of drug molecules across the BBB Expression of junction protein such as occludin and claudin |

McCarthy and Kosman (2015), Haorah et al. (2008) |

|

bEnd3 (mouse brain endothelial cells) |

The expresses most of the proteins like TJ and P-gp etc. as that of BBB TEER value of these cells is very less but, can be overcome by co-culturing with astrocytes |

Derived from brain endothelium of mouse Immortalized by transfecting with T-antigen |

DMEM/F12 |

To study the tight junction protein, stiffness, P-glycoprotein function and permeability of BBB To study the inflammatory responses and Aβ clearance mechanisms |

Qosa et al. (2016) Yang et al. (2017a), He et al. (2014) |

| RBE4 cells (Rat brain endothelial cells) |

They exhibit cationic, carnitine, serotonin and P-gp transports similar to that of human BBB Possess low TEER value Unable to express γ-glutamyl transporter-1 |

Isolated from the endothelium of the rat’s brain by enzymatic digestion of unwanted cells Later on, immortalized by SV40 or T-antigen |

DMEM/F12 |

Used to study the mechanisms that disturb the integrity of BBB the movement of substances across the membrane |

Roux and Couraud (2005), He et al. (2014) |

|

SHSY-5Y (human neuroblastoma cell) |

Tumorous cells Resembles mature cholinergic neurons upon differentiation |

Isolated from neuroblastoma in the embryonic stages | EMEM, DMEM/F12, RPMI |

To study the mechanisms of AD including Aβ, τ-protein and other pathways To investigate the relationship between AD pathophysiology and cerebral glucose metabolism To study oxidative stress, neurotoxicity and neurodegeneration process |

Koriyama et al. (2015), Forster et al. (2016), Krishna et al. (2014) |

| SK-N-MC |

These cells exhibit cholinergic properties They were found to possess double-minute chromosome |

Isolated from the metastatic supra-orbital human brain tumor | EMEM, DMEM/F12, RPMI |

To study the efficacy of the anti-AD drug on Aβ insulted SK-N-MC model To study AD pathology, Toxicity assessment |

Z. Yang (2012), Kuo and Tsao (2017) |

| PC-2 cell line (pheochromocytoma cell line) | The differentiated forms resemble sympathetic ganglion neurons | Derived from the pheochromocytoma of the adrenal cortex of the rat | EMEM, DMEM/F12, RPMI |

Used for neurite growth or differentiation into nerve like cell Used the study of different pathways like Aβ, τ-protein and oxidative stress |

Sun et al. (2018), Kudo et al. (2011) |

| hNPCs (human Neural Progenitor Cell) |

Different types of CNS neuronal cells can be formed by these cells They give a positive response to glutamine and GABA |

Derived from hESCs and hiPSCs by TGF-β signal modulation pathway | EMEM |

Used in the study of several pathophysiological processes of AD Patient-derived cells can be used in studying the patient-specific genetic mechanisms responsible for AD For drug screening |

Kang et al. (2017), Tsai et al. (2015) |

| HEK293 (Human embryonic kidney cell 293) | Even though these cells are non-neuronal cells, they express neuro-filament subunits and Tau-protein | Derived from normal human embryonic kidney but are transfected with Adenovirus-5-DNA to convert them into immortal cells | DMEM/F12 | To study of τ-protein phosphorylation and neurodegeneration | Gordon et al. (2013), Houck et al. (2016) |

|

7W CHO cell lines (7W Chinese Hamster ovary cell lines) |

These cells express Aβ similar to that of neurons even though they are of non-neuronal origin | Derived by transfection of CHO cells with human APP751 genes | DMEM |

Used to study the Aβ pathways relating to AD the effect of genes leading to AD |

Spilman et al. (2014), Uemura et al. (2010) |

| CALU-3 |

These cells exhibit the properties similar to that of the nasal-brain barrier They can express higher TEER values depending on the mode of culture |

Isolated from adenocarcinoma of the serous epithelium of human lung | DMEM/F12 | Used to study the mechanisms by which the drug reaches the brain when administering through the nasal cavity | Zheng et al. (2015), J. Fogh (1975), Srinivasan et al. (2015) |

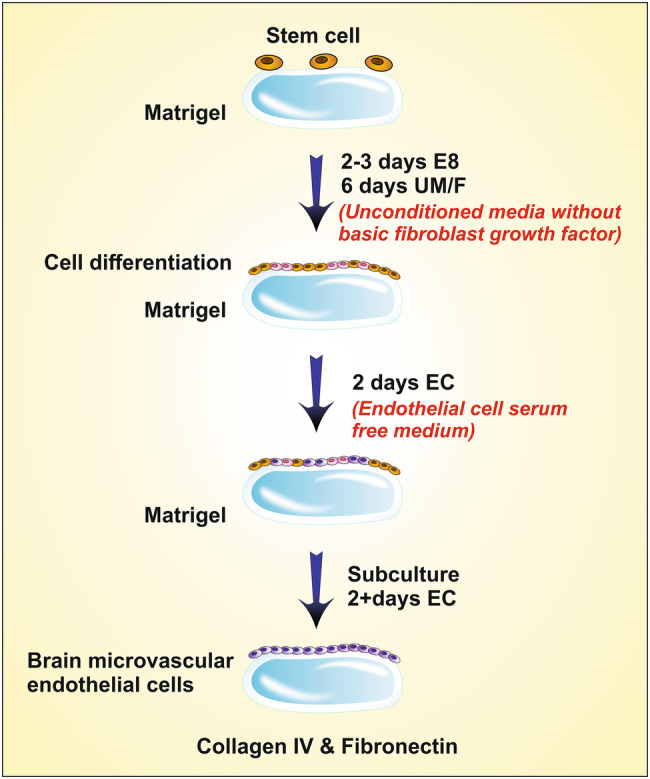

Human Brain Microvascular Endothelial Cell (HBMEC)

The inadequate number of phenotypically relevant cellular models is the major obstacle to study the exact physiology and behavior of the BBB. Though, there are few cell lines which utilizes immortalized human BMECs and type II Madin-Darby canine kidney cells (MDCK). However, they are unable to mimic the true nature of BBB cells. The human brain microvascular endothelial cell (HBMEC’s) have several physiological similarities with that of BBB cells in having several relevances like tight junction proteins (claudins, occludins, and junctional adhesion proteins), transporters and efflux pumps (Katt et al. 2016). These cells, obtained from tissue of the human, are cultured on collagen type I surface. The central theme in using collagen type 1 surface is that it adheres to the endothelial at a quicker rate than the remaining cells in the tissue (Navone et al. 2013; Chen et al. 2013). These cells generally derived from human immuno-potent cells (hiPCs). This small modifications in the method of the culturing process developed by Lippmann et al. In this, initial differentiation of iPCs cells modification, done in UM/F-media, then selective maturation of cells in endothelial cell media (EC), later the matured cells are purified by sub-culturing the cells on the collagen IV and fibronectin-coated surfaces (Fig. 3). Thus, the formed hBMECs cells are used for study and in research (Alexandrov et al. 2015). C-reactive protein (CRP) is an inflammatory mediator released by vascular endothelial cells, used as a biomarker to identify the presence of vascular inflammation associated with the progression of AD. The potency of aluminum in expressing CRP was studied by Alexandrov et al. (2015) on hBMECs. Aluminum was found to be potent enough to express CRP by altering the physiology of vasculature even in nano-molar concentrations (Alexandrov et al. 2015). Li et al. (2015) also utilized these cells to study the cytoprotective nature of naturally occurring flavonoid quercetin (a well-established neuro-protective agent) over Aβ induced cytotoxicity on endothelial cells of BBB. Findings revealed that the quercetin relived the cytotoxicity induced by Aβ, by reducing the lactate dehydrogenase secretion and by relieving condensation of the nucleus (Li et al. 2015). The changes in the characteristics of these cells upon co-culturing with astrocytes and in the presence of astrocyte-conditioned medium (ACM) remained studied by Kuo et al. (2011). They used hBMECs, hBMECs co-cultured with human astrocyte (hBMEC/HA) and hBMECs cultivated with 50% and 100% ACM to compare the resulting cells similarity with BBB. The finding revealed that the TEER values of these cells were in the order of hBMEC/HA > hBMECs cultivated with 100% ACM > hBMECs cultivated with 50% ACM > hBMECs and penetration property, expressed in exact reverse order. Thus, disclosing that the co-cultured cells are having higher similarity with BBB (Kuo and Lu 2011). In another study conducted by Moon et al. (2012) these cells were used to study the effect of rosiglitazone (thiazolidinedione a popular anti-diabetic) on the expression of a low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein (LRP1) which is an Aβ efflux transporter in BBB. They concluded that rosiglitazone at 10 nM concentrations could upregulate the LRP1 expression, thereby clearing the Aβ (Moon et al. 2012).

Fig. 3.

Derivation of HBMEC from stem cells (1) Growing of stem cells on matrigel (2) differentiation of cells by growing in Unconditioned media without primary fibroblast growth factor (3) growing of cells in endothelial cell serum-free media (4) Cells were grown on collagen lV and fibronectin surface

These studies reveal that hBMECs, used as a potent in vitro BBB model for studying the brain homeostasis and effects of Aβ in altering the physiology and properties of BBB along with the impact of secondary metabolic cascade reactions, etc. Though these cells were found to have many similarities with BBB obtaining these cell lines is very difficult as they remain obtained from human tissue, which is not readily available and has many complicated ethical problems. The trans-endothelial electrical resistance (TEER) value of cells derived from hIPCs was very less (approximately 100 Ω.cm2) when compared to that of human BBB (5900 Ω cm2) (Srinivasan et al. 2015). However, it can remain compensated by the addition of retinoic acid in the culture medium which increases the TEER value to (2000 Ω cm2) (Katt et al. 2016).

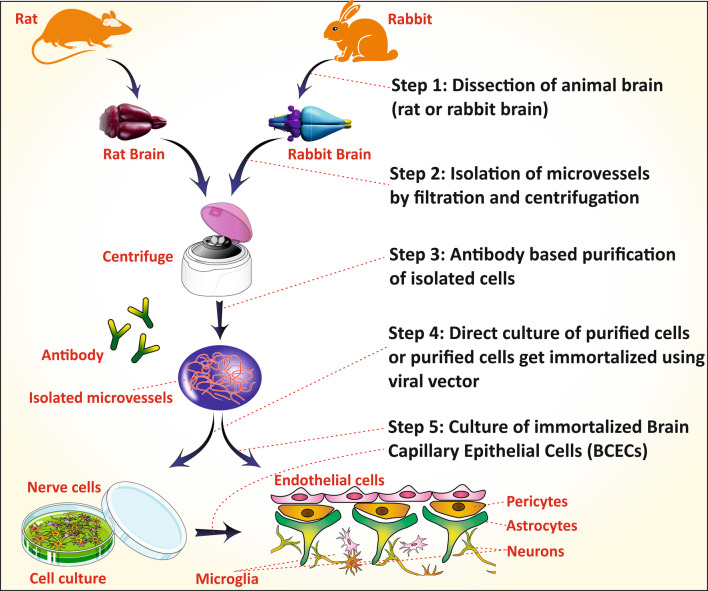

Brain Capillary Endothelial Cell (BCECs)

Brain capillary endothelial cells (BCECs) are the primary component of the Blood–Brain–Barrier (BBB) which in combination with astrocyte and pericytes assist the function of BBB. The development of a potential therapy for brain disorder needs a suitable in vitro model that represents the BBB. The in vitro BCECs cell line offers a promising tool to study the behavior of BBB in preliminary research investigations (Burkhart et al. 2015). The BCEC cells are isolated from micro-vessels of various animal models like a rat, mice or rabbit by dissection and collection of the forebrain, which is cultured by digesting the unwanted area (Fig. 4) (Huntley et al. 2014). Sometimes, it is co-cultured with the astrocytes and pericytes to make the BCECs mimic the BBB more prominently.

Fig. 4.

Steps of BCECs culture from the animal brain. (1) Dissection of animals(rat/rabbit) brain and filtration or centrifugation to isolate microvessels. (2) Antibody-based purification (or) fluorescence-based cell shortening to get purified cells (3) Direct culturing of purified cells (or) purified cells are immortalized using viral vectors (4) Culturing of immortalized BCECs

Zandl-Lang et al. (2018), studied the amyloid β (Aβ) clearance and amyloid precursor protein (APP) processing ability of simvastatin and ApoJ on the in vitro BCEC model. For the study, they utilized the primary BCEC, porcine BCEC and murine BCEC in vitro model which were isolated from the 3xTg AD mice model. The murine BCECs, when treated with hydrocortisone showed improved barrier properties (Zandl-Lang et al. 2018). Similarly, Candela et al. (2015) utilized the co-culture of pericytes with the bovine BCEC as in vitro BBB model to study the role of a low-density lipoprotein receptor-related peptide (LRP1) on the transcytosis and endocytosis behavior of BBB (Candela et al. 2015). Meng et al. (2015) did another critical study in 2015. They studied the cell uptake and cytotoxicity of the curcumin-loaded nano lipid carrier in the bovine BCECs model (Meng et al. 2015; Agrawal et al. 2018b). One more similar piece of work, included the study of BBB permeability of nerve growth factor (NGF) loaded rat monocyte. The drug transportation ability of rat monocyte was evaluated in vitro in the BCEC monolayer (Bottger et al. 2010). Such studies demonstrated the applicability of BCECs as the popular in vitro BBB model for studying the permeability, cytotoxicity and cellular uptake of the drug, bioactive or carrier systems. It is challenging to maintain the exact in vivo environment in the laboratory culture media. Thus, the isolated of BCECs may lose various essential characteristics of BBB (like low-passive permeability and high TEER) in the in vitro culture. The co-culture of BCECs with the astrocytes and the pericytes sometimes helps to retain the characteristic behavior of BBB (Burkhart et al. 2015).

hCMEC/D3

Human cerebro microvascular endothelial cell (hCMEC) being immortal human cell lines can proliferate in culture. They exhibit many similarities with that of human BBB by expressing most of the transporters and receptors, including tight junction proteins (TJPs), immune migration properties (Weksler et al. 2013). Co-culturing can increase the integrity of the cells with astrocytes (Daniels et al. 2013). These cell lines, derived from microvessels of the human temporal lobe. The isolate with cerebral microvessel endothelial cells (CECs). Later they are subsequently immortalized by transduction with the catalytic subunit of human telomerase reverse transcriptase using lentivirus as vector and then by SV40 large T-antigen followed by selective isolation of cells by restricting cloning dilution (Weksler et al. 2013). The negative effects of MicroRNA-155 on the function of BBB during neuro-inflammation was studied using these cell lines by Ramirez et al. (2014). The microRNA-155 was found to affect BBB in two ways. One by disassembling the inter-endothelial junctional complex (IJC) and integrin focal adhesion (FA) complexes, which may be due to the altered TJPs and the other way is by increasing permeability of BBB due to cytokines (Lopez-Ramirez et al. 2014). Pal et al. (2016) used these cells to study the histidine-rich Protein II produced by Plasmodium falciparum, in promoting the pathogenesis of brain in malarial condition. This protein was found to make the endothelial cells leaky by producing the inflammatory factors (Pal et al. 2016). Sun et al. (2018) studied the expression and processing of Aβ upon aging and the effect of angiotensin II using these cell lines. The production of Aβ increases with aging due to an increase in β-secretase and reduced expression of α-secretase by Angiotensin II (Sun et al. 2018). Freese et al. (2014) used these cells to study their newly established cell-based bioassay for testing the ability of drugs to cross BBB with the help of Acitretin as a model drug (Freese et al. 2014). From the above studies, it can know that these cells, used as an in vitro model cell lines for BBB. These cell lines help in studying the cerebral-endothelial inflammations, mechanisms of Aβ production, cytokines, immune migration studies, and permeability. These cells despite having several advantages, unable to express the TJPs like occluding and claudin-5 in levels similar to that of primary cerebral endothelial cells (Weksler et al. 2013). They also have very less TEER value (30–50 Ω cm2) when compared to normal human BBB (5900 Ω cm2) which may be possibly due to the imperfect formation of tight junction (Weksler et al. 2013; Biemans et al. 2017). However, this problem can be solved by co-culturing the cells with astrocytes (Daniels et al. 2013).

BMVECs

Brain microvascular endothelial cells (BMVECs) are the essential constituents of BBB, and their characteristic morphology allows the development of two discrete surfaces; the blood-sided surface (apical membrane) and brain-sided surface (basal layer) (McCarthy and Kosman 2014). It also possesses astrocytes on the basolateral surface, providing additional feature to these cells and even in protecting the cells against harmful chemicals like ROS. They form TJs, which give the BBB’s their integrity and regulates the movement of molecules across BBB (McCarthy and Kosman 2015). Thus, it is used to study the drug transport mechanism across the BBB, and the effect of altered physiological environment upon the integrity of the BBB. These cells, generally obtained from rat brain rather than human. The temporal-cortex is a part of epileptogenic foci of the brain, removed by the surgical process and is subjected to a series of isolation processes to obtain the required BMVECs cell lines (Haorah et al. 2008). Though these cell lines have shown the closest similarity with that of brain epithelium, they need more time for culturing and are prone to contamination, easily. Therefore, they are converted to immortalized cells as they are feasible to maintain and is economical. The conversion is mostly by the introduction of immortalized foreign genes using SV40 large T antigen as a vector (Navone et al. 2013). The neuroprotective action of saikosaponin C (SSc) obtained from the root of Bupleurum falcatum was screened on BMVCs cell lines derived from bovine by Lee et al. (2016). SSc showed the reduction of both the release of Aβ and the hyperphosphorylation of Tau (Lee et al. 2015). McCarthy et al. (2014) used co-culture cell line of BMVCs and C6 glioma cells (as an astrocyte cell line) to investigate the pathways involved in the movement of iron across the BBB and effect of ceruloplasmin and hepcidin on the flow of iron. In general, the ceruloplasmin increased the efflux and hepcidin increased the internalization of iron in the brain (McCarthy and Kosman 2014). The neuro-inflammatory effect on BBB in HIV-1 encephalitis (HIVE) condition was studied using these cell lines by Ramirez et al. (2010a, b). In HIVE, there is an upregulation of CD40/CD40L mediated by JNK signaling, which in turn upregulates the expression of several adhesion molecules. Thereby, increasing the adhesion of monocyte to BBB and thus it stimulates their migration across BBB (Ramirez et al. 2010a). A similar study was conducted by Ramirez et al. (2010a, b) to study the effect of GSK-3β on inflammation of brain endothelial cells. GSK was known to stimulate the immune responses and inflammatory responses. Findings reported that the suppression of GSK would, in turn, suppress the secretion of proinflammatory mediators from inflamed cells, thereby, inhibiting the monocyte adhesion and migration by suppressing the expression of adhesion molecules (Ramirez et al. 2010b). These studies expose the use of BMVCs as in vitro BBB model and help to study the mechanisms that act to alter the integrity of BBB during neuronal diseased conditions and permeability of molecules across it. Though, as usually obtained from the human brain, due to ethical problems most of the time they are received from animals, which has its limitations like the difference in the biochemistry of cells. Even the culturing is time consuming, costly and loss of characteristics over the passage of generations. To overcome these limitations, these cells were transformed into immortal cells, even though they are more beneficial than healthy cells, they suffer from tumors of nature (Navone et al. 2013).

Mouse Brain Endothelial Cells (bEnd3)

Endothelial cells are the primary components of the BBB that lines the blood capillaries. bEnd3 cells, derived from the brain endothelial cells express the TJ proteins, transport proteins mainly P-glycoprotein (P-gp) an efflux transporter used in clearing the Aβ from the brain and also these cells can form tight polarized monolayer limiting the paracellular permeability mimicking the properties of BBB (Qosa et al. 2016). These cells are derived from the endothelium of mouse brain and immortalized by the introduction of polyomavirus middle T-antigen using NTKmT retrovirus as a vector (Andrews et al. 2010). The increased effectiveness of PLGA PEGylated memantine nano-particles in comparison with the free drug for treating AD was screened using these cell lines by Sanchez-Lopez et al. (2018). The PEGylated formulation was found to have sustained release profile, and it also decreased the frequency of administration (Sanchez-Lopez et al. 2018; Alexander et al. 2014b). The neuroprotective nature of rifampicin and caffeine was screened on these cell lines by Qosa et al. (2012). Both these compounds were found to act in the same manner by upregulating LRP-1 and P-gp proteins, thereby increasing the clearance rate of Aβ from the brain (Qosa et al. 2012). Adiponectin is an adipokine known to control several metabolic functions and to decrease inflammation. Its role in controlling the apoptosis and expression of TJPs in brain endothelial cells was studied on these cell lines by Song et al. (2017). The activation of adiponectin inhibits the activation of NF-κB under Aβ toxicity, thereby inhibiting the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines. Hence, it protects the integrity of BBB by seizing the apoptosis/death of endothelial cells (Song et al. 2017; Gremmels et al. 2015). The murine brain endothelial cell line was utilized by Park et al. (2014) to understand the mechanism underlying the reduced expression of P-gp by Aβ. Usually, the expression of P-gp, induced by factors released from astrocytes that are in contact with endothelial cells. However, sometimes in the presence of Aβ astrocytes loose contact with endothelial cells via NF-κB signaling interacting through RAGE receptors. Therefore, the P-gp expression remains excluded in the presence of Aβ (Park et al. 2014). Above studies exposes the use of these cells as an in vitro model of BBB. It helps in studying the neurodegenerative mechanisms and their effect on BBB integrity like TJPs, permeability, inflammatory mechanisms and Aβ clearance rates from the brain. These cells, derived from mouse, so cannot replicate the exact conditions as that of human BBB. They cannot effectively differentiate the transcellular and para-cellular transport (Yang et al. 2017a). They also suffer from having very less TEER value (15 Ω cm2) when compared to that of BBB which can be increased to about 250 Ω cm2, when co-cultured with astrocytes (He et al. 2014).

Rat Brain Endothelial Cells (RBE4 cells)

RBE4 cells, used as an in vitro model for studying the characteristics of BBB. Being derived from a rat’s brain, they possess some similarities with that of human BBB by exhibiting cationic, carnitine, serotonin and P-gp transporters expresses the majority of neuronal factors as it is of neuronal origin (Naassila et al. 1996; Kis et al. 1999). They also possess high TEER values as they are co-cultured with astrocytes. They are mainly used to study the transport mechanisms of drugs across the BBB (Roux and Couraud 2005). The primary cultures of RBE cells are derived from the endothelium of the rat’s brain by enzymatic digestion, given by Molino et al. (2014) (Molino et al. 2014). The transduction of these primary cultures with an immortalizing gene (SV40 or adenovirus EIA or polyomavirus large T-antigen) using either plasmid DNA or retroviral vectors making the cells immortal. RBE4 cells are a result of co-culturing of primary RBE along with astrocytes, thus making the cells responsive to astroglial factors (Roux and Couraud 2005). Fonseca et al. (2014), used these cells to study the mechanism by which Aβ dissuade proteostasis in brain endothelial cells. According to this, Aβ persuades the failure of the response mediated by endoplasmic reticulum stress adaptive unfolded protein and deregulating the ubiquitin–proteasome system, which declines the activity of proteasome along with accretion of ubiquitinated proteins and damaging the autophagic protein degradation pathways that end up in cell death (Fonseca et al. 2014). The feasibility of chitosan as a nano-carrier for anti-AD drugs to pass through BBB was examined using these cell lines by Sarvaiya and Agrawal 2015. Chitosan (cationic polysaccharide), used as a nano-carrier because of hemocompatibility and biocompatibility with their application in parenteral and nasal drug deliveries (Sarvaiya and Agrawal 2015; Alexander et al. 2014a, 2016a). The effect of Cilostazol on the functioning of BBB was studied using these cells by Horai et al. (2013). Cilostazol is a selective phosphodiesterase-3 inhibitor and seems to increase BBB’s TEER value and decrease permeability (Horai et al. 2013). Durk et al. (2012) also utilized these cells to study the effect of 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin-D3 on P-gp. 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin-D3 upon binding to a Vit-D receptor on nucleus which upregulates the expression of P-gp (Durk et al. 2012). The above studies revealed the use of these cells as an in vitro model for BBB. It helps in studying the mechanisms that disturb the integrity of BBB, permeability across BBB and inflammatory responses. The limitation of this model is its high para-cellular permeability to small molecules. These cells are unable to generate compact monolayer and also has small barrier functions due to reduced expression of γ-glutamyl transporter-1 and alkaline phosphate activity (He et al. 2014). The TEER value is also decidedly less when compared to that of BBB when co-cultured with astrocytes and pericytes the TEER value increased but is not up to the mark (Roux and Couraud 2005).

Human Neuroblastoma Cell (SHSY-5Y)

Neuroblastoma cells are one of the widely employed cell lines as an in vitro model of AD. AD is characterized mainly by the depletion of acetylcholine, which is primarily due to the degradation of cholinergic neurons in the hippocampal region (Belle et al. 2004). Neuroblastoma cells, obtained in both undifferentiated and differentiated forms. Undifferentiated forms resemble mainly the immature cholinergic neuronal cells, and mature cholinergic cells, obtained upon differentiation (Kovalevich and Langford 2013). These similarities made the neuroblastoma cells very useful in studying the development, progression and drug discovery of AD. These cells are isolated from neuroblastoma a cancer of immature neuronal cells in the embryonic stage (Giri et al. 2018). These SHSY-5Y cells remain obtained after sub-cloning the parent line SK-N-SH. The resultant undifferentiated cells can remain differentiated into different neuronal phenotypes depending on the type of differentiating agent used. SH-SY5Y cells differentiate into cholinergic neuron phenotype upon treating with retinoic acid (RA). If phorbol esters are co-administered with retinoic acid, dopaminergic phenotype cells remain formed in higher percentages. If treated with a dibutyryl cyclic AMP, noradrenergic phenotype cells are formed predominantly (Kovalevich and Langford 2013; Elnagar et al. 2018). Koriyama et al. (2015) used these cells to study the glyceraldehyde (glycolysis inhibitor) as an inducer of AD. Glyceraldehyde induces AD-like pathophysiology by inducing production of GA-derived advanced glycation end products (GA-AGEs), cell apoptosis, and decreasing the concentration of Aβ but, increases τ-phosphorylation (Koriyama et al. 2015). The effect of anatabine on lowering the Aβ1−40,42 levels was screened by Paris et al. (2011a, b) using these cell lines. Anatabine has shown a decrease in levels of Aβ1−40,42 by inhibiting the transcription of β-secretase thus, affecting the β-cleavage of APP (Paris et al. 2011b). Petratos et al. (2008) also used these cell line to study the effect of Aβ on the neurite outgrowth from these cells and also to determine the initiation of downstream signaling and mechanisms that facilitate these effects. The neurite outgrowths are due to the phosphorylation of collapsin response mediator protein-2 (CRMP-2) where the extent of phosphorylation, regulated by Aβ induced an active form of RhoA (Petratos et al. 2008). These cells were also used by Avrahami et al. (2013) to study the inhibition of glycogen synthase kinase-3 (GSK-3) in ameliorating the pathology of Aβ and the mechanisms underlying that. The study gave positive results, by TOR receptor restoration and inhibiting the lysosomal acidification (Avrahami et al. 2013; Chonpathompikunlert et al. 2011). The above studies revealed that SH-SY5Y cells could be used as an in vitro neuronal model to study the different mechanisms other than well-known Aβ and τ-protein, which lay the path to AD, inflammatory cytokines, and NF-κB-signaling pathways. Despite having many advantages, they suffer from their drawbacks such as having cancerous cell nature like withstanding high-oxidative stress, expressing high levels of oxidative stress response genes in similar forms and high rates of glycolysis, which may alter the experimental outcomes (Forster et al. 2016; Krishna et al. 2014).

SK-N-MC

SK-N-MC, human neuroblastoma cell lines, are mainly cholinergic. The cholinergic nature is primarily due to the presence of α7-nicotinic receptors. These cell lines are influential in the study of AD, due to the reason that the mainly affected neurotransmitter in AD is acetylcholine (Gheysarzadeh and Yazdanparast 2012). Besides the cholinergic property, they are immortal cells. Hence they are very feasible to culture and cost-effective (Kuo and Tsao 2017; Alexander et al. 2016b). These cells are obtained from a metastatic supra-orbital human brain tumor. The cancer tissue is minced by placing in the medium and then treating with 0.125% trypsin and 0.02% EDTA in phosphate buffer devoid of calcium and magnesium, within 2–3 days a cell suspension remains formed. The cell suspension is (Biedler et al. 1973; Pin et al. 2007). The efficacy of liposomes grafted with lactoferrin (Lf) in delivering the drug across BBB was studied on these cell lines by Kuo and Wang (2014). In their study, a neuroprotective agent NGF was loaded into liposomes and screened for their efficacy to pass through HBMECs and to protect these cells against β-amyloid toxicity (Kuo and Wang 2014; Agrawal et al. 2017). Kuo and Tsao 2017) led a similar study to screen the efficacy of quercetin-loaded liposomes, which are grafted with lactoferrin, RMP-7 and bradykinin analog to cross the HBMECs and to shield these cells against toxicity induced by Aβ (Kuo and Tsao 2017). Shaykhalishahi et al. (2010) studied the neuroprotective action of AA3E2 (triazine derivative) against Aβ induced toxicity, by co-incubating the drug with these cells. The AA3E2 found to attenuate the production of ROS, caspase-3 activation and also decreased the rate of apoptosis (Shaykhalishahi et al. 2010). The neuroprotective nature of 1,3-diaryl-2-propane-1-one derivatives against damage induced by H2O2 was screened using these cell lines by Bayati et al. (2011). The mentioned studies reveal the use of SK-N-MC cells as an in vitro neuronal model. They help in studying the mechanisms of disease development. They are of tumorous origin; hence they may sometimes express properties of tumors. The evidence of the presence of double-minute chromosomes makes them differ from the neurogenic nature. These properties make them away from their usage as neuronal models (Biedler et al. 1973).

Pheochromocytoma Cell Line (PC-2 Cell Line)

Pheochromocytoma cell line (PC-2) cells, despite being the non-neuronal origin, are used in studies related to the nervous system. These cells are available in two forms as undifferentiated and differentiated cells (Lv et al. 2017). The undifferentiated cells are similar to immature neurons and express some neural characteristics like synthesis, storage, and secretion of some neurotransmitters such as dopamine (DA) and noradrenaline (NA). The differentiated PC12 cells phenotypically resemble sympathetic ganglion neurons despite being used in the study of AD via the Aβ pathway; these cells are used for analytical estimation of other pathological factors like tau-phosphorylation and oxidative stress conditions (Wei-Li Wang et al. 2015). PC12 cells are commonly derived from the pheochromocytoma of the adrenal cortex of Rattusnorvegicus (Kudo et al. 2011). Initially, the isolated similar cell lines get differentiated into specified cell lines upon treating with nerve growth factor (NGF) (Wei-Li Wang et al. 2015). The effect of phenolic compounds obtained from Pueraria lobate in protecting the neuronal cells against Aβ-toxicity was screened by Choi et al. (2010) utilizing these cell lines (Choi et al. 2010). The antioxidant activity of ethanol extracts and other compounds from Pyralo decorate against H2O2-induced cytotoxicity by using these cell lines was screened by Yang et al. (2017a, b) (Yang et al. 2017b). The neuroprotective effect of selaginella using differentiated PC12 cell lines on cytotoxicity and apoptosis induced by L-glutamate remained screened by Wang et al. (2010). Selaginella possesses anti-oxidant and anti-apoptotic behavior and hence served as a promising neuroprotective agent. It is commonly isolated from Saussurea pulvinate (Wang et al. 2010). These cells were also used by Zhang et al. (2016a, b) to study the neuroprotective nature of leptin. Leptin is an endogenously produced adipocytokine; it decreases the levels of Aβ and phosphorylation of τ-protein by antagonizing the Wnt-signaling pathway (Zhang et al. 2016b). The above studies reveal the use of these cells as an in vitro neuronal model and mainly used to study the pathways for AD pathophysiology and in screening the anti-AD drugs. PC12 cells are complicated to cultivate, time consuming and costly. The origin of these cells is also problematic in studies relating to human because as they are from rat, they are unable to mimic the exact scenario of human AD condition. They are also less sensitive to acetylcholine, but this problem remains solved by differentiation (Wei-Li Wang et al. 2015).

Human Neural Progenitor Cell (hNPCs)

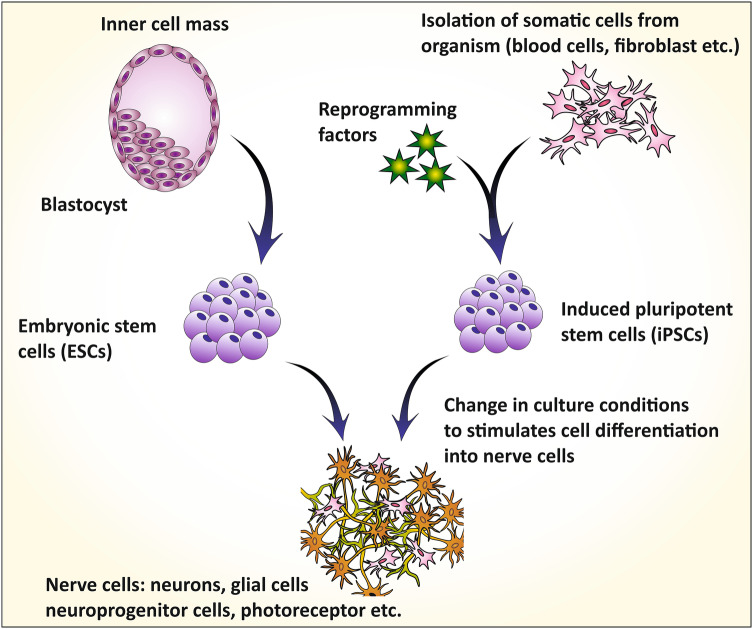

Human neuronal progenitor cells (hNPCs) are used as in vitro neurological models to study the neurological diseases and also has the potential to treat neuronal diseases such as spinal cord injury or stroke (Fukusumi et al. 2016). These cells exhibit a positive response to glutamine, GABA and synapsin 1 representing the presence of glutamatergic and GABA receptors and also shows synaptic transmission with each other. These can also differentiate into various types of CNS cells (Kang et al. 2017). hNPCs, derived from multiple sources like human embryonic stem cells (hESCs), human-induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs) and sometimes from the dead human cortex (Fig. 5) (Brafman 2015; Schwartz et al. 2003; Hibaoui and Feki 2012). HiPSCs are mostly used for generating hNPCs. There are various methods for producing these cells from hiPSCs. Fukusumi et al. (2016) used the embryoid body formation-based method (EBFM) and embryoid body formation method using dual SNAD inhibitors (dSMADi) (Fukusumi et al. 2016). Brafman (2015) used serum-free differentiation method grounded on TGF-β signal modulation (Brafman 2015).

Fig. 5.

Derivation of hNPCs from different sources. HECs and iPSCs, derived from inner cell mass of the blastocyst and reprogrammed somatic cells are induced to differentiate into hNPCs by giving neuronal-specific stimuli. These hNPCs are further used to form mature neurons, glial cells, and other neural-related cells

Kim et al. (2018) used these cells to study the underlying mechanisms relating to TNF-α in protecting the neurons under ischemic conditions. The procedure includes pre-treating the cells with TNF-α and then exposed to ischemic conditions. They observed that the neuroprotective nature is due to the drastic increase in NF-κB signaling by TNF-α (Kim et al. 2018). Daugherty et al. (2017) used these cells to examine the effect of new and novel AD drug, targeting inflammation and fatty acid metabolism (Alexander et al. 2016a). The anti-AD drug, CAD-31 a derivative of J147 (neurotropic molecule) that acts in this unique pathway, where it increases the production of precursors like Acetyl-CoA and acylcarnitine’s that enhance oxidation of fatty acids. Simultaneously, it inhibits the fatty acid synthesis by activating adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK) (Daugherty et al. 2017). The neural progenitor proliferation by an herbal drug from Acori tatarinowii (AT) was screened using these cell lines by Mao et al. (2015). Neuro progenitor cells (NPCs) proliferation and self-renewal can be seen throughout the life but decreases upon aging and in some neurodegenerative disorders. The active constituents of AT are found to increase proliferation of NPCs by activating extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) (Mao et al. 2015). These studies reveal the use of hNPCs as a potent in vitro neuronal model and assists in studying underlying pathophysiological mechanisms, cellular electrophysiology and protein biochemistry. hNPCs derived from specific patient helps in understanding the patient-specific genetic mechanisms underlying the pathophysiology. The disadvantage of this cell is that to date there is no clear description of the characteristic parameters of differentiated cells in different stages of development (Kang et al. 2017). Existing differentiating substrates used for discriminating hNPCs such as laminin (LN) are very costly and isolating the differentiated cells is also very difficult (Tsai et al. 2015).

Human Embryonic Kidney Cell 293 (HEK293)

HEK293 cells are non-neuronal cell lines, but it remains used in the studies relating to neurological diseases, for the reason that these cells exhibit several neurological factors like expressing neuro-filament subunits and other neuron-specific proteins (Gordon et al. 2013). They seem to be very useful in the study of tau-related neurological effects as they provide general stability, viability, and feasibility for transfection of tau protein (Houck et al. 2016). HEK 293 cells, derived from healthy human embryonic kidney (HEK) cells. These HEK cells, cropped with Adenovirus-5-DNA which makes these cells similar to immature neurons (Lin et al. 2014). These cells again derived into 293T, 293S, and 293SG, representing the behaviors like generating the stable clone, adapting to suspension growth and cytotoxic lectin selection (Lin et al. 2014). In 2014, Zhang et al. (2014a, b) used the cells to study the paradoxical effects that occur due to inhibition of TrKA in AD. A cytotoxin is containing 31 amino acid chain (C31), produced by slicing the APP with caspase, mediated via TrKA signaling. Inhibition of TrKA reduces the production of C31 thus, reducing cytotoxicity (Zhang et al. 2014b). Chang et al. (2016) used these cells to examine the effect of Glycyrrhiza inflata aqueous extract in upregulating the unfolded protein response, which mediates the chaperones to decrease the misfolding of tau protein and production of ROS in AD cell models (Chang et al. 2016). He et al. (2010) used these cells. In understanding the new therapeutic targets for AD, reporting the discovery of γ-secretase-activating protein (GASP). GASP was seen to interact with γ-secretase and APP, increasing the production of Aβ. The inhibition of GASP, used as a novel promising therapy of AD, by decreasing Aβ without affecting any other essential function of γ-secretase (He et al. 2010). These cells were also utilized by Zhou et al. (2017) to study the systemic clearance and distribution in the brain of new anti-AD drugs. They reported the novel Carbazole-based cyanine compounds which inhibited the aggregation of Aβ (Zhou et al. 2017). The above studies suggest the use of these cells as an in the vitro neuronal model in studying the pathways leading to AD mainly related to τ-protein, cytotoxicity, and screening of anti-AD drugs. The main drawback of these cells is their non-neurological origin. Even though these cells express NF-M, NF-L, and α-internexin as major NF protein along with minor NF-H whose concentrations are similar to that of developing mammalian central neurons, indicating HEK293 cells similarity with neuronal stem cells, they cannot match with neurons or neurologically originated cell lines (Gordon et al. 2013).

7W Chinese Hamster Ovary Cell Lines (7W CHO Cell Lines)

These cells originated from the ovary of the Chinese hamster, which upon transfection with human APP751 express the APP protein, Aβ, and related proteins. They also show and act as a model to study the mechanisms relating to presenilin genes, upon transfecting PS1 and PS2 genes (Octave et al. 2000). When transfected with ApoE genes, they can express the mechanisms underlying ApoE and can act as a model for it (Irizarry et al. 2004). The primary cell line for 7W CHO cell line is Chinese hamster ovary (CHO), which upon transfection with human APP751 genes converts into 7W CHO (Paris et al 2014). The transfection is mediated by pCMV751 an expressing vector using lipofectin-facilitated transfection (Koo and Squazzo 1994). In addition, pACL29 vector applied for a transfecting PS1 gene into CHO. Anekonda and Quinn (2011) used these cells to screen Ca2+ channel blockers as a therapeutic approach for treating AD by taking isradipine as a model drug. Isradipine is a dihydropyridine Ca2+ channel blocker, which selectively binds to the L-type Ca2+ channel present on the somatodendritic and axons of the hippocampal and cortex regions. The blocking of these channels lowered the τ-burden and improved the brain autophagy functions (Anekonda and Quinn 2011). A similar type of study was conducted by Paris et al. (2011a, b) to screen the effect of several anti-hypertensive dihydropyridine Ca2+ channel blockers in reducing the levels of Aβ. Among the tested drugs, nilvadipine and amlodipine showed promising results (Paris et al. 2011a). Spilman et al. (2014) used these cells to study the effect of tropisetron in treating AD. Tropisetron binds to the ectodomain of APP and decreases the production of anti-tropic, neurite-retractive peptide Aβ, thus reverses AD condition (Spilman et al. 2014). D. Paris et al. (2014) studied the mechanism by which the spleen tyrosine kinase (Syk) helps in regulating Aβ production and tau hyperphosphorylation. Inhibition of Syk mimics and downregulates the production and increases the clearance of Aβ by decreasing the secretion of sAPPβ by stimulating Aβ clearance (Paris et al. 2014). It also plays an essential role in reducing τ-phosphorylation by acting through protein kinase A. These studies reveal the use of 7W CHO cell lines as an in vitro model for Alzheimer’s in studying the mechanisms relating AD pathology and effect of different genes in AD. These cells, originated from hamster, have a physical and biochemical difference with that of the human. Koo and Squazzo (1994) showed the difference like Aβ produced from CHO cells with that of human-derived cell lines (Veeraraghavan et al. 2011).

CALU-3 Cell Lines

Nowadays, administration through the nasal route for targeting brain remains widely used. Through the nasal administration, the drug can directly enter the brain by passing through trigeminal and olfactory nerves or by absorbing through the nasal mucosa, avoiding BBB hindrance. However, the mucosa of the nasal cavity forms a nose–brain barrier restricting the conduction and bioavailability of drugs to the brain. These cell lines by mimicking nose–brain barrier help in studying the mechanisms of the passage of the drug through the nasal cavity to the brain (Zheng et al. 2015). These cells, initially derived by Fogh (1975), from adenocarcinoma of the serous epithelium of human lung (Fogh 1975). Zheng et al. (2015) used these cells in 2015 to screen the efficiency of the H102 peptide, a novel drug candidate administered through the intranasal route, for the treatment of AD. It is a β-sheet breaker, delivered in the form of liposomes (Zheng et al. 2015). A similar study for delivering the puerarin, an isoflavone glycoside extracted from Radix puerariae lobatae to the brain via intranasal administration, conducted by Zhang et al. (2016a, b). These cells can be used as an in vitro model for nasal passages and are useful in understanding the mechanism of the passage of drug through the nasal membrane to brain administered via nasal route (Zhang et al. 2016a). These cells develop from the tumor cells. Hence they express the cancerous properties such as higher rates of oxidation. They also represent a wide range of TEER values from 100 to 2500Ω cm2 depending on the type of culture and culture medium (Srinivasan et al. 2015).

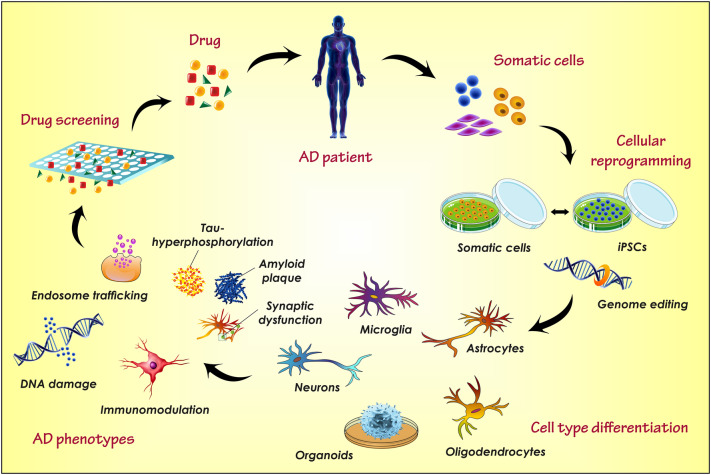

Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs)

iPSCs are self-renewable cells that are able to differentiate into different types of cells including neuronal cell line and represent a promising tool for researchers to study the disease etiology, progression and drug efficacy (Haston and Finkbeiner 2016; Poon et al. 2017). iPSCs have the potential to proliferate and differentiate into different AD-relevant cells such as astrocytes, microglia, forebrain neurons, etc. which allows the study of individual neuronal cells, their functions and interdependency within the brain (Fig. 6) (Sullivan and Young-Pearse 2017; Zhang et al. 2014a). The iPSCs was first derived by Takahashi and Yamanaka (2006), they investigated that some factors present in oocyte cytoplasm possess an ability to reprogram the somatic cells into the embryonic cell like a stage and thereby induced pluripotency to the somatic cells. Initially, they induced pluripotency to the adult mouse fibroblast by treating with Sox2, Oct3/4, Klf4 and c-Myc cytoplasmic factors (Takahashi and Yamanaka 2006; Mungenast et al. 2016). These four oocyte cytoplasmic factors are termed as ‘Yamanaka factors.’ Later in 2007, they reprogramed the human fibroblast cells with these Yamanaka factors into hiPSCs (human-induced pluripotent stem cells) (Takahashi et al. 2007). From the first iPSC discovery to date, the cell biology developed different methods to differentiate the iPSCs into specified human neuronal cells which recapitulate the AD-like condition (Sullivan and Young-Pearse 2017). For in vitro AD modeling, the iPSCs have been particularly differentiated into astrocytes (GFAP+) and neurons like βIII-tubulin and MAP2+ (Yagi et al. 2011; Israel et al. 2012). However, the neurons of cortical forebrain (TBR1+) and cholinergic nerves of basal forebrain (CHAT+), primarily associated with the AD etiology can be recreated by some special growth factor signals produced by additional media supplements (Duan et al. 2014).

Fig. 6.

The figure illustrates the reprogramming and culture of AD patient-derived somatic cells/nerve cells as iPSCs and its differentiation in different nerve cells, application in the investigation of AD pathophysiology and screening the drug efficacy [adapted and modified from (Mungenast et al. 2016)]

In 2011, Yagi and team first demonstrated the application of iPSCs in AD modeling. They produced iPSCs from patients having a familial AD with mutated genes presenilin-1 (A264E) and presenilin-2 (N141I). The culture of AD cell line contains an excess of extracellular Aβ40−42 in the supernatant which is the prime component of AD pathology. While a significant reduction in the Aβ40−42 ratio was observed when treated with a γ-secretase inhibitor (Yagi et al. 2011). Later, in 2014, Sproul et al. also produced iPSCs line with increased Aβ42/40 ratio by culturing the nerve cells of AD patients with a mutation in the presenilin gene (Sproul et al. 2014). Further, Balez and co-workers (2016) had co-cultured the iPSC-derived nerve cells with the murine-activated microglial cells. They recognized the effect of oxidative stress and inflammation in AD progression and observed considerably higher apoptosis of iPSC-derived AD nerve cells than the familial and sporadic AD patients (Balez et al. 2016). Similarly, it is used to study various phenotypes of AD which facilitates the understanding of AD etiology and also assists the study of novel therapeutics. Such studies support the application of iPSCs as a promising tool for the investigation of AD pathology. However, its application is limited because the iPSCs cannot recapitulate all the pathological phenotypes of AD which may be due to the simple culture methods (Poon et al. 2017).

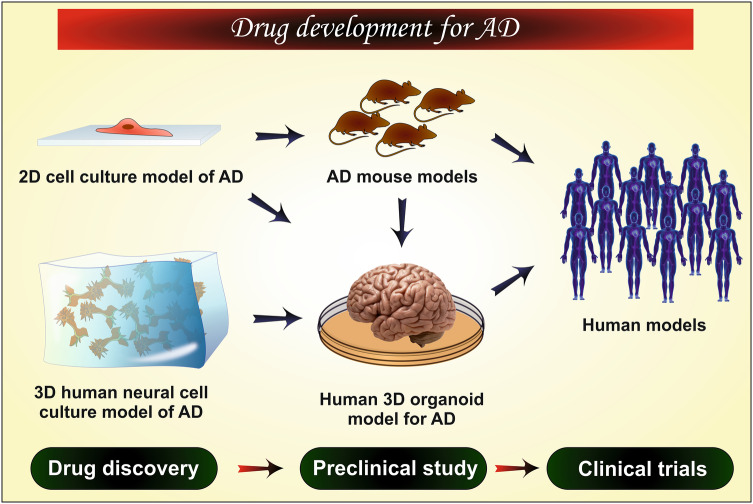

Cerebral Organoids and 3D Models

Neurofibrillary tangles and amyloid plaque formation is the primary factor of AD which further initiates or boosts the other phenotypes of AD-like inflammation, nerve cell death, synaptic and cholinergic dysfunctioning, etc. Despite the availability of numerous in vivo and in vitro models, the suitable experimental model which exactly recapitulate the essential features of AD nerve cells is still lacking (Gonzalez et al. 2018). In this sequence, the cerebral organoids and iPSCs represents a new and promising model for AD investigation. With the advancement of technologies, the scientists make it possible to develop a three-dimensional organ-like structure or artificial organs from the pluripotent stem cells (both the embryonic and induced pluripotent stem cells) known as organoids (Wang 2018; Clevers 2016). In the past few years, various protocols have been established to create the brain or cerebral organoids from the pluripotent stem cells (Dyer 2016; Di Lullo and Kriegstein 2017; Giandomenico and Lancaster 2017; Kadoshima et al. 2013; Lancaster and Knoblich 2014; Li et al. 2017; Sutcliffe and Lancaster 2017). Moreover, some studies claim that cerebral organoids can also be produced from fate-restricted neural stem cells (Clevers 2016; Monzel et al. 2017). These artificial brains or cerebral organoids represents a potential strategy to study the human brain anatomy, physiology, and etiology of neurological disorders.

The brain organoids can be produced by 3D-culture of PSCs or specified neurons. The application of 2D-cell culture is limited to the disease modeling of iPSCs or other single cell lines, particularly for investigation of various neurological disorders. The 3D culture or 3D models overcome the limitations of 2D models by offering a more physiologically pertinent model of specified tissues, cells, cell-matrix or cell–cell connections (Clevers 2016). The brain organoids created from the 3D culture of neuroepithelium are not just more complex than the 2D models but it also able to recapitulate the different regions of the human brain, the synapse or connection between different regions and connection between various cellular components (Lancaster and Knoblich 2014; Pașca 2018).

The production of a suitable in vitro model for sporadic AD is always a challenge to the scientist because the neurons of in vitro culture are immature to recapitulate the exact scenario of AD brain. Thus, the 3D model and brain organoids offer a promising tool for the modeling of more complex etiological factors of AD including Aβ-aggregation and tau-phosphorylation (Lee et al. 2016; Choi et al. 2014). In 2016, Raja et al. utilized iPSCs of familial AD patients and introduced a scaffold-free cell culture method to create the brain organoids. This brain organoids successfully recapitulates the AD pathologies like the tau-pathies, Aβ aggregation, disease progression and also provide a good prototype for the development of novel therapeutics (Wang 2018; Yan et al. 2018).

The Technique of Cell Culture/Culture Medium Development

The cell culture media helps in the growth and development of cells which can be in the form of liquid or semisolid. It remains used for maintaining proper growth, replication, and differentiation of cells. Thus, it is very crucial to select and keep in an appropriate medium for in vitro propagation of cells. A suitable culture medium has an appropriate energy source, essential amino acids and vitamins, growth regulators, attachment factors and sometimes differentiating agents.

Standard Culture Medium (SCM)

The standard culture medium is the essential media containing salt solutions, potassium lactate, casein digest and glucose for energy supplementation. Casein acts as a source of nitrogen and amino-acid (except cysteine) (Marshall and Kelsey 1960). As it is an essential medium, mostly it is supplemented with additives like a serum. This media, however, generally used for the culturing of mesenchymal stem cells, human-induced pluripotent stem cells and a few more cell types (Danielyan et al. 2014; Nieweg et al. 2015).

Eagle’s Minimal Essential Medium (EMEM)

EMEM has mostly used to culture mammalian cells, and its name came from its developer Harry Eagle. It is pure, basal media containing balanced salt solutions, sodium pyruvate, eight vitamins and 12 kinds of non-essential amino acids. It is formulated to use with 5% CO2. As a simple medium, it always supplemented with additives, or a high concentration of serum makes them suitable to grow mammalian cells (Yang 2012; Arora 2013). This medium is used to culture embryonic nerve cells, glial cells, and cell lines like SH-SY5Y cells, hBMECs, hCMECs, hNPCs, PC12 and SK-N-MC cells (Waheed Roomi et al. 2013; Aldick et al. 2007; Kiss et al. 2013; Ravichandran et al. 2011; Zheng et al. 2016).

Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium Nutrient Mixture F12 (DMEM/F12)

DMEM is the mostly employed cell medium in cultured neuronal cells and is the advanced version of EMEM containing double the amount of amino acids and quadruple the number of vitamins including sodium pyruvate, ferric nitrate, and additional amino acids. Depending on the concentration of glucose this medium occurs in two forms, low-glucose type (1000 g/L) for standard cell cultures and high glucose type (4500 g/L) for cultures containing tumors. These media remains mostly supplemented with 5–10% bovine serum. Same to that of EMEM this is medium is also formulated to use with 5% CO2. DMEM/F12 is 1:1 mixture of DMEM and Ham’s F-12 media (Yang 2012; Arora 2013). It can remain formulated as both serum and serum-free media. This media, therefore, are used for culturing endothelium, mouse neuroblastoma, and cell lines like bEND3, BCECs HEK293, RBECs, SHSY-5Y, PC12, and Sk-N-MC cells (Hayakawa et al. 2014; Li et al. 2013; Veeraraghavan et al. 2011; Yang et al. 2017b; Park et al. 2014; Zhou et al. 2017).

RPMI Media

These media are developed at Roswell Park Memorial Institute thus the name RPMI. This media is an advanced version of McCOY’s 5A media and has proper concentrations of phosphate and remains formulated for use with 5% CO2. It is one of the utmost broadly employed media and remains used for culturing tumor cells, hybridoma cells and cell lines like PC12, SHSY-5Y and SK-N-MC cells, etc. (Yang 2012; Arora 2013; Wei-Li Wang 2015).

Endothelial Cell Basal Medium (EBM)