Abstract

Oxytocin has various effects ranging from promoting labor in pregnant women to alleviating stress. Recently, we reported the hair growth-promoting effects of oxytocin in hair follicle organoids. However, its clinical application faces challenges such as rapid degradation in vivo and poor permeability due to its large molecular weight. Therefore, in this study, we investigated the effects of the oxytocin receptor (OXTR) agonists WAY267464 and LIT001 as alternatives to oxytocin on hair growth. Human dermal papilla (DP) cells were cultured in WAY267464 or LIT001-supplemented medium. The addition of WAY267464 and LIT001 increased the expression of hair growth-related genes in DP cells. We tested the hair growth-promoting effects of WAY267464 and LIT001 using hair follicle organoids in vitro and found that they significantly promoted hair follicle sprouting. Thus, our findings indicate that WAY267464 and LIT001 are potential hair growth agents and may encourage further research on the development of novel hair growth agents targeting OXTR in patients with alopecia.

Keywords: Hair growth, Oxytocin, Oxytocin receptor, Alopecia, Hair follicle, Dermal papilla

Subject terms: Biomaterials, Tissue engineering

Introduction

Hair is a part of the body that affects the impression of oneself, patients with alopecia often have a considerable sense of loss and poor psychological health. Recent studies have shown that several alopecia symptoms can be alleviated using effective drugs, such as 5-alpha reductase inhibitors (finasteride and dutasteride) for androgenic alopecia1,2 and JAK inhibitor (baricitinib) for alopecia areata3,4; thus, most patients with alopecia choose drug therapy as the first treatment option. However, these agents have side effects and differences in efficacy. Therefore, there is a great demand for the development of additional and effective drugs.

Oxytocin, known as the love hormone, is a neuropeptide consisting of nine amino acids. It is produced mainly during childbirth and lactation5 and through physical contact with family members and partners. It has been administered intravenously in pregnant women to promote labor6. It also provides mental comfort and exerts therapeutic effects against stress-related diseases7. We identified oxytocin is a candidate hair growth-promoting drug8 as it has been shown to upregulate the expression of hair growth-related genes in dermal papilla (DP) cells. Hair follicle organoids (termed hair follicloids) can regenerate hair shafts in vitro, and hair shaft length increases in response to hair growth-promoting drugs, such as minoxidil, and oxytocin treatment remarkably increases hair shaft length in hair follicloids8.

Although the efficacy of oxytocin in hair follicles has been confirmed, several challenges remain in its application as a hair growth-promoting drug. Specifically, oxytocin has a very short half-life in the blood (< 8 min)9, which may reduce its efficacy over time. Oxytocin has an affinity for capsaicin, vasopressin, and oxytocin receptors (OXTR)10,11, and a low receptor specificity may result in unexpected side effects12. Furthermore, the skin and hair follicular permeability of oxytocin may be limited owing to its high molecular weight (MW = 1007).

Recently, non-peptide agonists of oxytocin (LIT001 and WAY267464) were developed and reported to be an effective therapeutic agent for targeting OXTR13,14. LIT001 and WAY267464 have lower MW than oxytocin (MW = 531 and 655, respectively). LIT001 is an agonist with high affinity for OXTR14,15. Furthermore, LIT001 shows neither agonistic nor antagonistic effects on vasopressin receptors15.

Therefore, in this study, we investigated the effects of LIT001 and WAY267464 on the expression of hair growth-related genes in DP cells and hair growth promotion in hair follicloids (Fig. 1). This research will help identify highly effective drugs that target the oxytocin pathway and greatly advance the development of new drugs for alopecia.

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of the experimental procedure. Treatment with oxytocin receptor (OXTR) agonists WAY267464 and LIT001 increased the sprouting length of hair follicloids, suggesting that WAY267464 and LIT001 promote hair growth.

Results

Effects of OXTR knockdown on hair growth ability of DP cells

Bioinformatic analysis showed that OXTR expression decreased in DP cells obtained from patients with alopecia compared with those from healthy donors (Fig. 2a), and the genes involved in hair follicle maturation were upregulated in the high OXTR expression group (Fig. 2b,c). These results motivated us to investigate the relationships between OXTR and hair loss/growth. We found that OXTR knockdown in human DP cells reduced the expression of genes associated with hair growth (Fig. 2d,e).

Fig. 2.

OXTR knockdown suppresses mRNA levels of trichogenic genes in human dermal papilla (DP) cells. (a) Linear OXTR mRNA expression levels in healthy scalp tissues (Healthy, n = 14) and androgenetic alopecia (AGA) scalp tissues (n = 14), which were collected from the GEO database (GSE90594). Error bars represent the standard error. Numerical variables were statistically evaluated using Student’s t-test. (b) High- and low-OXTR groups were categorized based on the mean value of log2 transformed HIF1A mRNA level (high, n = 14; low, n = 14; mean = 4.1). (c) Representative gene set enrichment analysis plots of the high- and low-OXTR groups (d) Immunocytostaining of OXTR in OXTR knockdown DP cells. DP cells were incubated with negative control siRNA (siCont) and OXTR siRNA (siOXTR) for 3 days and stained using OXTR antibody. (e) Gene expression of OXTR and hair growth-related markers in DP cells after 3 days of culture. Error bars represent the standard error calculated from three independent experiments. Numerical variables were statistically evaluated using Student’s t-test. (f) Microscope images of hair follicloids prepared using siCont-treated or siCont-treated DP cells for 10 days. Hair follicloids were permeabilized and observed using a stereomicroscope. (g) Length of sprouting structures. The graph shows the length ratio of sprouting structures on days 6, 8, and 10 compared to that on day 4. We cultured at least 24 hair follicloids per treatment condition to calculate sprouting length. Numerical variables were statistically evaluated using Student’s t-test. Asterisks indicate significance at *p < 0.05.

We prepared hair follicloids composed of human DP cells and human follicular keratinocytes (epithelial cells) according to a previously described method16. DP cells were previously treated with OXTR siRNA and non-targeting control siRNA for 3 days of culture. Irrespective of siRNA treatment, hair follicloids showed a spherical aggregation (DP cells) at one end and a stick-like structure (epithelial cells) extending toward the other end during 10 days of culture (Fig. 2f). The growth of epithelial cells and the associated elongation of the stick-like structure were significantly shortened in hair follicloids prepared with OXTR siRNA-treated DP cells compared to those in follicloids treated with the control siRNA (Fig. 2g). These results indicate that OXTR is largely responsible for the hair growth-promoting ability of DP cells, suggesting that OXTR is a potential therapeutic target for the development of alopecia drugs.

Effects of OXTR agonists on hair growth

To understand the genes and signaling pathways affected by treatment with OXTR agonists (WAY267464 and LIT001), we performed RNA-seq analysis. The analysis revealed that the addition of WAY267464 and LIT001 resulted in the upregulation of 5481 and 6674 genes, respectively (Fig. 3a,b). Furthermore, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway analyses revealed that the neuroactive ligand-receptor interaction, oxytocin signaling pathway, and cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction were among the top ten terms associated with WAY267464 or LIT001 treatment (Fig. 3c,d). These pathways were among the upregulated KEGG pathways induced by oxytocin treatment in our previous study8; therefore, we further examined the effects of WAY267464 and LIT001 on hair growth as alternatives to oxytocin.

Fig. 3.

RNA-seq analysis of DP cells treated with WAY267464 and LIT001 (a, b) Heatmap of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between DP cells treated with/without WAY267464 (a) and LIT001 (b). (c, d) Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) analysis; top ten enriched pathways were identified by using upregulated DEGs.

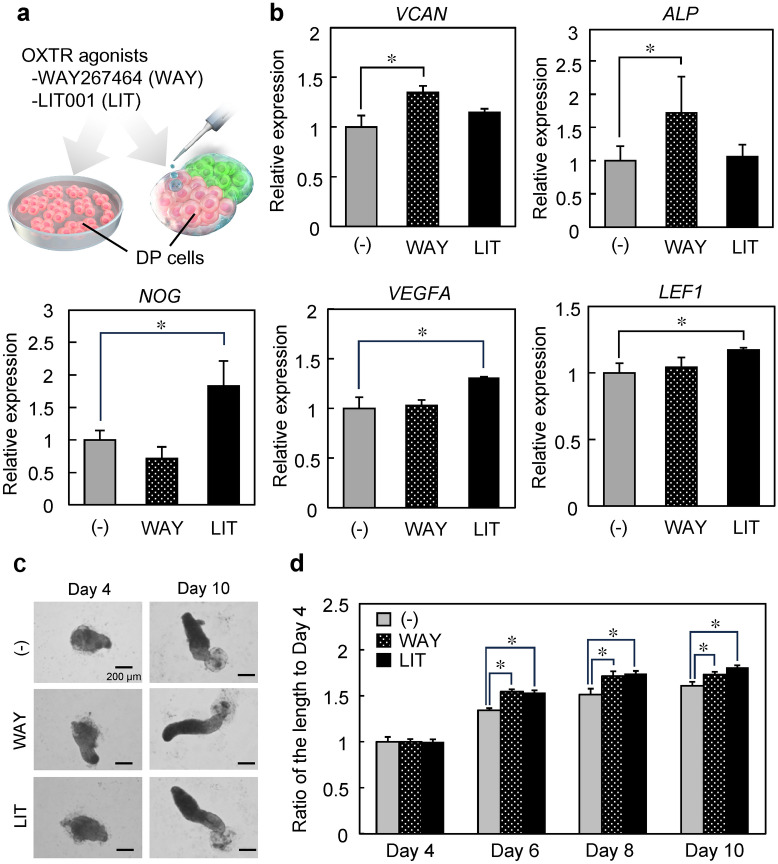

The effects of WAY267464 and LIT001 on gene expression of DP cells and elongation of the stick-like structure of hair follicloids were examined (Fig. 4a). DP cells were cultured in WAY267464 or LIT001-supplemented medium for 3 days, and the expression of hair growth-related genes was measured. WAY267464 increased VCAN and ALP expression in DP cells, whereas LIT001 increased NOG, VEGFA, and LEF1 expression (Fig. 4b). OXTR agonists selectively bind to OXTR without altering OXTR expression (Supplemental Fig. 1). The length of the stick-like structure was significantly increased in the presence of WAY267464 and LIT001 (Fig. 4c,d). Notably, OXTR was considerably expressed in DP cells of hair follicloids but minimally in epithelial cells (Supplemental Fig. 2). To understand the relationship between OXTR and elongation, hair follicloids were cultured with the OXTR antagonist L-371,257 (Supplemental Fig. 3). The elongation of the stick-like structure decreased with L-371,257. We further examined the effects of OXTR agonists on human hair follicle organ culture (Fig. 5). LIT001 significantly promoted hair shaft elongation. These results suggest that OXTR agonists stimulate DP cell functions and are potential hair-growth-promoting drugs.

Fig. 4.

Treatment of DP cells and hair follicloids with OXTR agonists. (a) OXTR agonist treatment in DP cells and hair follicloids. (b) Gene expression of hair growth-related markers in DP cells after 3 days of culture. Error bars represent the standard error calculated from three independent experiments. Numerical variables were statistically evaluated using Tukey’s test. (c) Microscope images of hair follicloids cultured with/without WAY267464 and LIT001 for 10 days. Hair follicloids were permeabilized and observed using a stereomicroscope. (d) Length of sprouting structures with/without WAY267464 and LIT001. The graph shows the length ratio of sprouting structures on days 6, 8, and 10 compared to that on day 4. We cultured at least 24 hair follicloids per treatment condition to calculate sprouting length. Numerical variables were statistically evaluated using Tukey’s test. Asterisks indicate significance at *p < 0.05.

Fig. 5.

Effects of OXTR agonist on hair shaft elongation in human hair follicle organ culture. (a) Microscopic images of hair follicles cultured with/without 20 μM LIT001 for 7 days. (b) Changes in the length of hair shafts. The graph shows the length of hair shafts elongated after day 1. Scalp hair follicles were extracted from AGA-patients and examined in 24 well cell culture insert. Error bars represent the standard errors calculated from six independent experiments. Numerical variables were statistically evaluated using Student’s t-test. Asterisks indicate significance at *p < 0.05.

Discussion

OXTR, a 7-transmembrane G protein-coupled receptor, activates several signaling cascades, such as the mitogen-activated protein kinase, protein kinase C, or phosphoinositide-specific phospholipase C pathways17. These signaling pathways maintain homeostasis in various organs and tissues, and the activation of OXTR may be a therapeutic strategy for specific diseases. Previous studies have reported that OXTR agonist improves social interactions in a mouse model of autism14, reduces alcohol intake in male mice18, and increases social and cognitive functions in a schizophrenia rat model19. In the skin, dermal fibroblasts and keratinocytes express OXTR, and oxytocin signaling plays a role in regulating cell proliferation, inflammation, senescence, and oxidative stress responses20. However, to the best of our knowledge, there are no studies on the effects of OXTR on cells in hair follicles. In the present study, we demonstrated that LIT001 and WAY267464, non-peptidergic-specific agonists of OXTR, have hair growth-promoting effects, which hold great promise as drug candidates for alopecia treatment. Thus, these insights will accelerate the search for novel OXTR-targeting drugs.

To address the stability and skin permeability issues of oxytocin, this study examined OXTR agonists. Molecules with an MW > 500 have reportedly difficulty to penetrate healthy skin21. LIT001 and WAY267464, with MWs of 531 and 655 respectively, are smaller than oxytocin (MW 1007) but still exceed this value. However, since the target of OXTR agonists is hair follicles, particularly DP cells, these molecules might reach DP cells through hair follicle pores. This is partially supported by a previous report that bioactive peptides with relatively large MW (MW of 509 and 774) were delivered to the DP through follicular pores and promoted hair growth in the skin22. They used nanoliposomes to load the peptides and deliver to DP. The penetration kinetics and effects of LIT001 and WAY267464 on human skin samples will be our next subject. Additionally, other OXTR agonists with smaller MWs and high penetration kinetics, and combinations with drug delivery system via follicular pores23 may provide better approaches.

Bioinformatic analysis showed low OXTR expression levels in DP cells from patients with alopecia (Fig. 2a). This result may be due to various factors, including genetic factors common to patients with alopecia; psychological environmental factors, such as happiness and stress; and growth factors produced by hair loss. This result can also be considered both a cause and consequence of alopecia. In the present study, OXTR knockdown in DP cells suppressed hair growth-related gene expression (Fig. 2f). This indicates that low levels of OXTR expression are primarily associated with hair loss. However, the sample size for the bioinformatic analysis was small. Further studies are required to elucidate the relationship between OXTR expression and androgenetic alopecia (AGA), incorporating diverse samples across different ages and sexes.

OXTR activation can be achieved by using oxytocin itself or OXTR agonists. Oxytocin is produced in response to skin stimulation (e.g., hugging and massaging), music therapy, and interaction with pet animals, in both men and women5,24,25. Lifestyle improvement will promote OXTR activation, and its simplicity is an advantage of using oxytocin. However, due to low receptor binding specificity and activation of other receptors, continuous administration of oxytocin may decrease its effectiveness and produce side effects. OXTR agonists with high receptor binding specificity may alleviate these risks.

The top 10 KEGG terms associated with WAY267464 or LIT001 treatment included neuroactive ligand-receptor interactions, oxytocin signaling pathway, and cytokine-cytokine receptor interactions. Notably, these pathways were upregulated by oxytocin treatment in our previous study8. Thus, WAY267464 and LIT001 are potential hair-growth promoting alternatives to oxytocin, but several pathways were differently upregulated by LIT001 and WAY267464. These agonists may have different mechanisms and provide additional hair growth benefits when used in combination with LIT001 and WAY267464. Future research should elucidate the mechanisms and verify the effects of the combination. Additionally, more than ten oxytocin agonists are available, future studies will classify them based on the genes activated in DP cells and test their efficacy in inducing hair growth using hair follicloids.

We used OXTR agonists to activate oxytocin signaling, but an approach to increase OXTR using RNA-based therapy is also possible. The target genes can be selectively controlled using RNA-based therapy26,27. In hair research, the expression of androgen receptors that mediate a series of biomolecular changes leading to hair loss can be selectively silenced by RNA interference28. Clinical studies on the application of siRNA to the scalp have confirmed its hair growth-promoting effects29. An approach to increase the expression level of OXTR using mRNA therapy may also be effective for hair loss treatment, which we will investigate in future studies.

In our previous study, we developed a technique for preparing hair follicloids that efficiently regenerate hair follicles in vitro16,30,31. The hair follicles are generated via epithelial-mesenchymal interaction32, and the reconstruction of the interaction between epithelial and mesenchymal cell populations (including DP cells) enabled the production of hair follicles in vitro. In the hair follicles, DP cells produce several growth factors that stimulate the proliferation of epithelial cells to elongate the hair shaft. Hair growth-promoting drugs increase hair elongation via activation of growth factor secretion by DP cells. Therefore, hair follicloids can be used to evaluate the hair growth-promoting effects of drugs using elongation of the stick-like structure as an indicator after the addition of the drug candidate16. Treatment with an existing hair growth-promoting drug, such as minoxidil, promotes the elongation of the stick-like structure16. In the present study, hair follicloids were cultured in culture medium with WAY267464 or LIT001. These drug candidates elongated the stick-like structure, but the sprouting length by WAY267464 or LIT001 treatment was shorter than that by minoxidil treatment. To enhance the hair growth effect of WAY267464 or LIT001 treatment, it may be necessary to optimize the culture conditions, including drug concentration, timing, duration, and drug combinations. Minoxidil was initially developed as an antihypertensive agent, and its ability to increasing blood flow was suggested as a mechanism to promote hair growth; however, several other mechanisms have since been proposed, including opening of potassium channels, activation of β-catenin signaling as well as extracellular signal-regulated kinase and Akt signaling, and increased release of growth factors, such as FGF733–36. Combination with minoxidil, which has a different action mechanism from OXTR agonists, might be an effective treatment for alopecia.

OXTR agonists increased the expression of hair growth-related genes in DP cells and accelerated the elongation of hair follicles sprouting from hair follicloids. These findings were further supported by results from human hair follicle organ culture, a standard assay for investigating hair growth-promoting agents. However, testing many drugs using this approach is challenging due to the limited availability of hair follicles and variability in results based on individual follicle conditions, such as their in vivo anagen/telogen phase and the isolation process. To address this limitation, the present study often used an approach to reconstruct hair follicle organoids from cells dispersed from multiple hair follicles. A significant issue in using hair follicloids for drug testing is the lack of a method for expanding human follicular keratinocytes without rapidly losing their hair-generating ability. In this study, hair follicloids were prepared with human follicular keratinocytes without passaging culture to preserve their functions. Consequently, the number of experiments using cells from the same human samples was limited, necessitating control experiments with the same cell vial to normalize all hair elongation data. To alleviate this limitation in drug testing with hair follicloids, a novel method for expanding follicular keratinocytes while maintaining their functions is needed.

Our findings represent the first step towards demonstrating the hair growth-promoting effect of OXTR agonists. Future research must obtain more evidence of their effects using organ culture and animal models. Specifically, organ culture studies should investigate four categories: (i) prolongation of the anagen phase or inhibition of the catagen phase; (ii) promotion of proliferation or inhibition of apoptosis in the hair matrix; (iii) regulation of important hair growth mediators at the protein expression level, particularly in DP cells, the hair matrix, and/or the outer root sheath; (iv) observation of OTXR-specific effects of WAY267464 and LIT001, with significant antagonization documented by OTXR silencing. In animal studies, effective conditions will be investigated by optimizing the concentrations of WAY267464 and LIT001, as well as the time and frequency of administration. Although the cells used in this study were from healthy donor, the efficacies of WAY267464 and LIT001 should be evaluated in future using donor cells isolated from patients with alopecia. We will continue these analyses to develop novel therapeutic agents for hair loss treatment.

In conclusion, OXTR expression levels in DP cells from patients with alopecia were low. OXTR knockdown in DP cells suppressed the expression of hair growth-related genes. WAY267464 and LIT001 increased the expression of hair growth-related genes in DP cells and accelerated the elongation of hair follicles sprouting from hair follicloids. Thus, our findings showed that WAY267464 and LIT001 are potential hair growth-promoting agents that target OXTR, facilitating their application as a treatment. Our findings will accelerate the development of therapies targeting OXTR.

Methods

Preparation of human DP and epithelial cells

Adult human DP cells were obtained from PromoCell (Heidelberg, Germany), and cultured up to passage four in DP cell growth medium (DPCGM; PromoCell), creating a 2D culture. Adult human follicular keratinocytes (epithelial cells) were obtained from the Scientific Cell Research Laboratories (Carlsbad, CA, USA). DP and epithelial cells were cultured in passage four and one, respectively, and used for organoid culture. Incubator gas tension was maintained at 37 °C with a 21% O2 and 5% CO2 at 37 °C.

Informatics analysis

The scalp gene expression in patients with androgenetic alopecia (AGA) was assessed using the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) dataset www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo(www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo, GSE90594). OXTR mRNA expression levels (A_33_P3413741 at the probe) were evaluated between healthy controls (n = 14) and AGA patients (n = 14). For gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA; www.broadinstitute.org/gseawww.broadinstitute.org/gsea), the mean value of A_33_P3413741 (corresponding to OXTR) was used to categorize the low- and high-OXTR expression groups. A false discovery rate (FDR) of less than 0.25 was considered statistically significant.

siRNA knockdown

We performed siRNA knockdown experiments on DP cells and hair follicloids. Liposome-encapsulated OXTR siRNA was prepared according to the manufacturer’s instructions and added to the culture medium. Briefly, DP cells (2 × 104 cells) were seeded into a 24-well cell culture plate (Corning Inc., Corning, NY, USA) and cultured for 1 day in 0.5 mL DPCGM. The culture medium was replaced with 0.5 mL DPCGM supplemented with siRNA complexes, which were prepared according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, RNAiMAX (Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, USA) and 10 μM siRNA were diluted 50 times and suspended in Opti-MEM™ I Reduced Serum Medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). These solutions were mixed at 1:1 ratio and incubated for 5 min at 25 °C. The resultant siRNA complex (25 μL) was added to DPCGM (0.5 mL), and cells were cultured for 2 days. The siRNAs were OXTR siRNA (AM16708, Invitrogen) or AllStars negative control siRNA (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). DP cells cultured for 3 days after seeding were used for polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis and a hair follicloid assay16.

WAY267464 or LIT001 treatment of DP cells

DP cells (2 × 104 cells) were suspended in 0.5 mL DPCGM supplemented with 20 μM LIT001 or WAY267464 (MedChemExpress, Monmouth Junction, NJ, USA) and seeded into a 24-well cell culture plate (Corning Inc.). Gene expression in DP cells was assessed using real-time reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) after 3 days of culture.

WAY267464 or LIT001 treatment of hair follicloids

Hair follicloids were cultured in a medium without WAY267464 and LIT001 for 4 days and then in the presence of WAY267464 or LIT001 for an additional 6 days. To prepare hair follicloids, DP (5 × 103 cells) and epithelial (5 × 103 cells) cells were suspended in 0.2 mL advanced Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium/nutrient mixture F-12 (DMEM/F-12; Thermo Fisher Scientific) containing 2% (v/v) Matrigel (Corning Inc.) and seeded into a non-cell-adhesive round-bottom 96-well plate (Primesurface® 96U plate; Sumitomo Bakelite Co., Ltd., Japan)16. The DMEM/F-12 was supplemented with 20 μM LIT001 or WAY267464 from days 4 to 10 after seeding. Then, 0.1 mL of the spent medium was replaced with fresh medium every 2 days. Hair sprout lengths were observed using an all-in-one fluorescence microscope (BZ-X810; Keyence, Japan).

Hair follicle organ culture

After obtaining informed consent, human scalp hair follicles were obtained from patients with androgenic alopecia. This study was approved by the ethics committee of the Kanagawa Institute of Industrial Science and Technology (approval number: S-2019-01) and Yokohama National University (approval number: 2021-04). The study was performed in accordance with their guidelines and the Declaration of Helsinki. Scalp hair follicles were extracted from AGA patients and placed in a 24-well cell culture insert. The culture medium used was Stemfit® AK02N (Ajinomoto, Japan) containing 10 μM Y27632. The hair follicles were cultured with or without 20 μM LIT001, and the length of black hair shafts was measured using ImageJ software.

Immunocytochemical staining

As described previous study8, we performed immunocytochemical staining. DP cells were cultured for 3 days in DPCGM for immunocytochemical staining and fixed with 4% (v/v) paraformaldehyde (FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Corporation, Osaka, Japan) for 10 min. The samples were washed three times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and blocked in blocking solution [PBS containing 3% (v/v) normal goat serum (Abcam, Cambridge, UK) and 0.3% (v/v) Triton-X (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA)] for 1 h at 25 °C. Thereafter, the cells were incubated for 1 h with anti-OXTR (1:200 dilutions, 23,045-1-AP, Proteintech, Rosemont, IL, USA) at 25 °C. The samples were washed three times with blocking solution and incubated with the corresponding Goat Anti-Rabbit IgG H&L (Alexa Fluor® 488) antibody (1:500 dilutions, ab150077, Abcam) in the blocking solution for 1 h at 25 °C and lastly with rhodamine-phalloidin (ab235138, Abcam) and 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; ab228549, Abcam) in PBS for 30 min. A confocal microscope (LSM 700, Carl Zeiss, Germany) was used for fluorescence imaging.

Gene expression analysis

As described previous study8, we performed gene expression analysis. Total RNA was extracted from the DP cell samples using a RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), and their complementary DNA was synthesized using the ReverTra Ace® RT-qPCR Kit (Toyobo, Osaka, Japan) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Subsequent qRT-PCRs were performed using the StepOne Plus RT-PCR system (Applied Biosystems, Waltham, MA, USA) with SYBR® Premix Ex Taq™ II (Takara Bio, Kusatsu, Japan) and primers for amplifying human OXTR, VCAN, ALP, NOG, VEGFA, LEF1, and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH). Primers used in this study are listed in Table 1. All gene expression levels were normalized to that of GAPDH. The 2−∆∆Ct method was used to determine relative gene expression levels, which were presented as the mean ± standard error of three independent experiments.

Table 1.

PCR primer sequences.

| Genes | Forward (5′–3′) | Reverse (5′–3′) |

|---|---|---|

| ALP | ATTGACCACGGGCACCAT | CTCCACCGCCTCATGCA |

| VCAN | GGCACAAATTCCAAGGGCAG | TCATGGCCCACACGATTAACA |

| LEF1 | CTTCCTTGGTGAACGAGTCTG | TCTGGATGCTTTCCGTCAT |

| OXTR | CCTTCATCGTGTGCTGGACG | CTAGGAGCAGAGCACTTATG |

| NOG | CTGGTGGACCTCATCGAACA | CGTCTCGTTCAGATCCTTTTCCT |

| VEGFA | ACTTCTGGGCTGTTCTCG | TCCTCTTCCTTCTCTTCTTC |

| GAPDH | TGGAAGGACTCATGACCACAG | GGATGATGTTCTGGAGAGCCC |

RNA-seq analysis

Total RNA was extracted from DP cells (with/without 20 μM LIT001 or WAY267464 treatment for 3 days) using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen). RNA-seq analysis was performed by Takara Bio. Significantly upregulated genes in DP cells subjected to OXT treatment were used for the KEGG pathway analysis via the Database for Annotation, Visualization, and Integrated Discovery (http://david.abcc.ncifcrf.gov/)37–39.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses of gene expression levels and hair sprout length were conducted using Tukey’s test or Student’s t-test, and the results were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05. All data are presented as the mean ± standard error.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Kanagawa Institute of Industrial Science and Technology, Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research [KAKENHI; Grant No. 20H02535, 23K13614, and 23H01771], and Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development [Grant No. 23811701]. Further, the authors would also like to express their gratitude to Shonan AGA Clinic, Shinjuku South Exit Institution, and Tokyo Hair Transplant Cosmetic Surgery for generously providing human hair follicle samples, which facilitated this research.

Author contributions

T.K. designed the experiments. T.K. and J.S. conducted most of the experiments. T.K., J.S., L.Y. and J.F. prepared the manuscript.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available in the NCBI repository, GSE252536.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-024-74962-9.

References

- 1.Gupta, A. K., Venkataraman, M., Talukder, M. & Bamimore, M. A. Finasteride for hair loss: A review. J. Dermatol. Treat33, 1938–1946. 10.1080/09546634.2021.1959506 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arif, T., Dorjay, K., Adil, M. & Sami, M. Dutasteride in androgenetic alopecia: An update. Curr. Clin. Pharmacol.12, 31–35. 10.2174/1574884712666170310111125 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu, M. et al. Janus kinase inhibitors for alopecia areata: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw. Open6, e2320351. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.20351 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ko, J. M. et al. Clinical outcomes for uptitration of baricitinib therapy in patients with severe alopecia areata: A pooled analysis of the BRAVE-AA1 and BRAVE-AA2 trials. JAMA Dermatol.159, 970–976. 10.1001/jamadermatol.2023.2581 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Florea, T. et al. Oxytocin: Narrative expert review of current perspectives on the relationship with other neurotransmitters and the impact on the main psychiatric disorders. Medicina (Kaunas)58, 923. 10.3390/medicina58070923 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Walter, M. H., Abele, H. & Plappert, C. F. The role of oxytocin and the effect of stress during childbirth: Neurobiological basics and implications for mother and child. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne).12, 742236. 10.3389/fendo.2021.742236 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Takayanagi, Y. & Onaka, T. Roles of oxytocin in stress responses, allostasis and resilience. Int. J. Mol. Sci.23, 150. 10.3390/ijms23010150 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kageyama, T., Seo, J., Yan, L. & Fukuda, J. Effects of oxytocin on the hair growth ability of dermal papilla cells. Sci. Rep.13, 15587. 10.1038/s41598-023-40521-x (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leng, G. & Sabatier, N. Measuring oxytocin and vasopressin: Bioassays, immunoassays and random numbers. J. Neuroendocrinol.10.1111/jne.12413 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chini, B. et al. Two aromatic residues regulate the response of the human oxytocin receptor to the partial agonist arginine vasopressin. FEBS Lett.397, 201–206. 10.1016/s0014-5793(96)01135-0 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nersesyan, Y. et al. Oxytocin modulates nociception as an agonist of pain-sensing TRPV1. Cell Rep.21, 1681–1691. 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.10.063 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oh, Y. K. Vasopressin and vasopressin receptor antagonists. Electrolyte Blood Press6, 51–55. 10.5049/EBP.2008.6.1.51 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hicks, C. et al. The nonpeptide oxytocin receptor agonist WAY 267,464: receptor-binding profile, prosocial effects and distribution of c-Fos expression in adolescent rats. J. Neuroendocrinol.24, 1012–1029. 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2012.02311.x (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frantz, M. C. et al. LIT-001, the first nonpeptide oxytocin receptor agonist that improves social interaction in a mouse model of autism. J. Med. Chem.61, 8670–8692. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.8b00697 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hilfiger, L. et al. A nonpeptide oxytocin receptor agonist for a durable relief of inflammatory pain. Sci. Rep.10, 3017. 10.1038/s41598-020-59929-w (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kageyama, T., Miyata, H., Seo, J., Nanmo, A. & Fukuda, J. In vitro hair follicle growth model for drug testing. Sci. Rep.13, 4847. 10.1038/s41598-023-31842-y (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jurek, B. & Neumann, I. D. The oxytocin receptor: From intracellular signaling to behavior. Physiol. Rev.98, 1805–1908. 10.1152/physrev.00031.2017 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Potretzke, S. et al. Male-selective effects of oxytocin agonism on alcohol intake: Behavioral assessment in socially housed prairie voles and involvement of RAGE. Neuropsychopharmacology48, 920–928. 10.1038/s41386-022-01490-3 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Piotrowska, D., Potasiewicz, A., Popik, P. & Nikiforuk, A. Pro-social and pro-cognitive effects of LIT-001, a novel oxytocin receptor agonist in a neurodevelopmental model of schizophrenia. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol.78, 30–42. 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2023.09.005 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Deing, V. et al. Oxytocin modulates proliferation and stress responses of human skin cells: Implications for atopic dermatitis. Exp. Dermatol.22, 399–405. 10.1111/exd.12155 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bos, J. D. & Meinardi, M. M. The 500 Dalton rule for the skin penetration of chemical compounds and drugs. Exp. Dermatol.9, 165–169. 10.1034/j.1600-0625.2000.009003165.x (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tian, L. et al. Co-delivery of bioactive peptides by nanoliposomes for promotion of hair growth. J. Drug. Delivery Sci. Tech.72, 103381. 10.1016/j.jddst.2022.103381 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Patzelt, A. et al. Drug delivery to hair follicles. Expert. Opin. Drug. Deliv.10, 787–797. 10.1517/17425247.2013.776038 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shen, H. Neuroscience: The hard science of oxytocin. Nature522, 410–412. 10.1038/522410a (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marshall-Pescini, S. et al. The role of oxytocin in the dog-owner relationship. Animals (Basel)9, 792. 10.3390/ani9100792 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhu, Y., Zhu, L., Wang, X. & Jin, H. RNA-based therapeutics: an overview and prospectus. Cell Death Dis.13, 644. 10.1038/s41419-022-05075-2 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim, Y. K. RNA therapy: Rich history, various applications and unlimited future prospects. Exp. Mol. Med.54, 455–465. 10.1038/s12276-022-00757-5 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moon, I. J. et al. Efficacy of asymmetric siRNA targeting androgen receptors for the treatment of androgenetic alopecia. Mol. Pharm.20, 128–135. 10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.2c00510 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yun, S. I. et al. Weekly treatment with SAMiRNA targeting the androgen receptor ameliorates androgenetic alopecia. Sci. Rep.12, 1607. 10.1038/s41598-022-05544-w (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kageyama, T. et al. Reprogramming of three-dimensional microenvironments for in vitro hair follicle induction. Sci. Adv.8, eadd4603. 10.1126/sciadv.add4603 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kageyama, T., Anakama, R., Togashi, H. & Fukuda, J. Impacts of manipulating cell sorting on in vitro hair follicle regeneration. J. Biosci. Bioeng.134, 534–540. 10.1016/j.jbiosc.2022.09.004 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Millar, S. E. Molecular mechanisms regulating hair follicle development. J. Invest. Dermatol.118, 216–225. 10.1046/j.0022-202x.2001.01670.x (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rossi, A. et al. Minoxidil use in dermatology, side effects and recent patents. Recent Pat Inflamm. Allergy Drug. Discov.6, 130–136. 10.2174/187221312800166859 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kwack, M. H., Kang, B. M., Kim, M. K., Kim, J. C. & Sung, Y. K. Minoxidil activates beta-catenin pathway in human dermal papilla cells: a possible explanation for its anagen prolongation effect. J. Dermatol. Sci.62, 154–159. 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2011.01.013 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Han, J. H. et al. Effect of minoxidil on proliferation and apoptosis in dermal papilla cells of human hair follicle. J. Dermatol. Sci.34, 91–98. 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2004.01.002 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee, C. Y. et al. Hair growth is promoted by BeauTop via expression of EGF and FGF-7. Mol. Med. Rep.17, 8047–8052. 10.3892/mmr.2018.8917 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kanehisa, M., Furumichi, M., Sato, Y., Kawashima, M. & Ishiguro-Watanabe, M. KEGG for taxonomy-based analysis of pathways and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res51, D587–D592. 10.1093/nar/gkac963 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kanehisa, M. & Goto, S. KEGG: Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res.28, 27–30. 10.1093/nar/28.1.27 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kanehisa, M. Toward understanding the origin and evolution of cellular organisms. Protein Sci.28, 1947–1951. 10.1002/pro.3715 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available in the NCBI repository, GSE252536.