Abstract

ARL13B is a small regulatory GTPase that controls ciliary membrane composition in both motile cilia and non-motile primary cilia. In this study, we investigated the role of ARL13B in the efferent ductules, tubules of the male reproductive tract essential to male fertility in which primary and motile cilia co-exist. We used a genetically engineered mouse model to delete Arl13b in efferent ductule epithelial cells, resulting in compromised primary and motile cilia architecture and functions. This deletion led to disturbances in reabsorptive/secretory processes and triggered an inflammatory response. The observed male reproductive phenotype showed significant variability linked to partial infertility, highlighting the importance of ARL13B in maintaining a proper physiological balance in these small ducts. These results emphasize the dual role of both motile and primary cilia functions in regulating efferent duct homeostasis, offering deeper insights into how cilia related diseases affect the male reproductive system.

Subject terms: Reproductive biology, Ciliogenesis

The deletion of ARL13B disrupts primary and motile cilia structure in the efferent ductules, leading to impaired homeostasis, inflammation, and subfertility. This highlights ARL13B’s critical role in male reproductive physiology.

Introduction

Within the male mammalian reproductive system, the efferent ductules are small tubules responsible for conveying sperm from the testis to the head of the epididymis1,2. During this process, the epithelium engages in a dynamic activity of fluid reabsorption, leading to an approximately 28-fold increase in sperm concentration3. In men, the proximal head of the epididymis is entirely composed of efferent ducts and it is common to find pathologies that involve the rete testis and these convoluted tubules4,5. For instance, sperm stasis, luminal obstructions, and cystic dysplasia with the formation of sperm granulomas in the efferent ducts result in male infertility6–9.

The efferent ducts form in utero from the mesonephric tubules2,10 and, in adults, display reabsorptive capacity comparable to that found in the kidney11. Under the control of estrogen and androgen receptor pathways, the ductal epithelium is capable of reabsorbing nearly 90% of the fluid originating from the testis. This process relies on the expression of several important proteins found in the so-called “nonciliated” epithelial cells, including SLC9A3/NHE3 (Na + /H+ Exchanger-3), AQP1 and AQP9 (aquaporins), CA2 (Carbonic Anhydrase 2), CFTR (Cystic Fibrosis Transmembrane conductance Regulator), and Na + /K+ ATPase5,12–16. The stirring movement of motile cilia present at the surface of the multiciliated cells (MCC) maintains sperm in suspension17 and is essential for proper fluid reabsorption18–23. Adjacent to MCC are primary ciliated cells (PCC), previously described as non-ciliated or principal cells1,5,24,25. Similar to principal cells of the rete testis26–31 and the epididymis32–34, the PCCs in the efferent ducts have long, sensory, primary cilia that extend into the lumen or extracellular spaces31,32,35–38; however, their function in the efferent ducts remains unexplored (Fig. 1A).

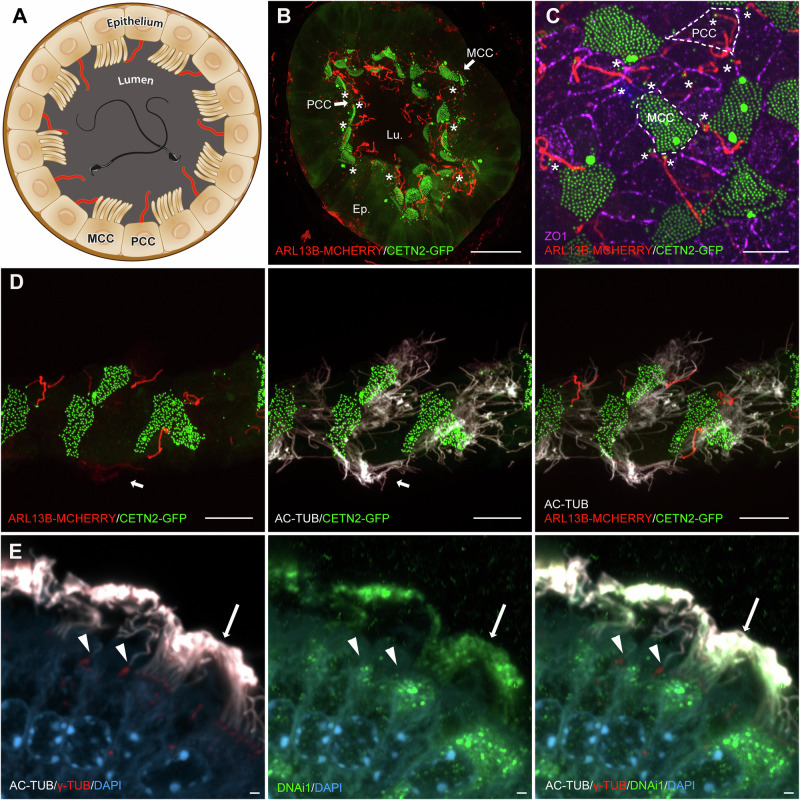

Fig. 1. Both multiple motile cilia and solitary primary cilia are present at the surface of the efferent ductules.

A Cross sectional representation of one mouse efferent ductule (ED) displaying the main cells populating the ED epithelium: the primary ciliated cells (PCC) and multiciliated cells (MCC). B–D Confocal imaging microscopy of EDs from adult Arl13b-mCherry; Cetn2-GFP double transgenic mice. B Long Arl13b-positive cilia extend from PCC towards the lumen of the EDs (stars). Multiciliated cells are characterized by the apical alignment of numerous CETN2-positive basal bodies. Scale bar=15 µm. C Individual PCC and MCC delineation through ZO1 tight junction marker labeling (dotted lines) indicates that solitary ARL13B-positive cilia originate from CETN2-positive basal bodies of PCC (stars). Scale bar = 10 µm. D Exogenous labeling for alpha-acetylated tubulin cilia marker (AC-TUB). In situ discrimination of solitary primary cilia from multiple motile cilia is facilitated in Arl13b-mCherry; Cetn2-GFP double transgenic mice in which ARL13B-MCHERRY positive motile cilia are faintly detected (arrow). E Immunostaining for the alpha-acetylated tubulin cilia marker (AC-TUB, white), centrioles (γ-TUB, red), and DNAi1 (green) shows that DNAi1 labels the dynein intermediate chain in motile cilia (indicated by arrows) but is absent in primary cilia (indicated by arrowheads) in ED from wild-type mice. Scale bar 1 µm. Ep. Epithelium, Lu. Lumen, PCC Primary ciliated cells, MCC Multiciliated cells.

Cilia are microtubule-based cell membrane projections that serve as antennae in the control of a plethora of functions39–41. While both non-motile primary cilia and motile cilia share similar structural features and molecular composition, they differ in their microtubule arrangement (9 microtubule doublets without or with a central pair, denoted as 9 + 0 vs. 9 + 2, respectively), cell-lineage specificity (in most cell types vs. in specialized cells, respectively), and functions (mechano-chemo-sensors vs. mechanical flow generators, respectively). However, exceptions to this general postulate exist (for review42,43). In mammalian tissues, motile and non-motile cilia coexist in only a few specific locations. For instance, in the embryonic node, solitary motile and primary cilia collaborate to regulate left-right asymmetry during embryonic development44–46. In the human oviduct, multiciliated cells are located adjacent to secretory cells, which occasionally exhibit primary cilia47,48. Additionally, in the brain ventricles, multiple motile cilia facilitate the movement of cerebrospinal fluid along the surface of ependymal cells, where populations of primary ciliated cells sense and respond to cerebrospinal fluid factors49–53. Such a unique interplay might also occur in the efferent ducts, where both multiple motile and primary cilia are found in neighboring cells.

In the efferent ducts, while primary cilia have been observed at the surface of epithelial cells adjacent to MCC31,32,35,38, their function is not known. For instance, several mouse models with impaired multicilia formation consistently display mild tubule dilation and sperm accumulation, and luminal occlusions that cause male infertility19–21,23,54, for review55). However, the potential effects of an impairment of sensory functions of the primary cilia have not been investigated yet. A functional cooperation between the two epithelial cell types has been previously hypothesized: while ligated efferent ducts lumen in vitro quickly collapses, over an extended period these tubules demonstrated the ability to reopen, suggesting that the sensory primary cilium could detect luminal congestion and activate a signaling pathway to reverse fluid resorption38.

Arl13b encodes an Arf/Arl-family GTPase that participates to ciliary membrane elongation in both multiple motile cilia56 and non-motile primary cilia57–59. Initially identified in zebrafish (Danio rerio) as the scorpion (sco) gene60, subsequent investigations revealed that ARL13B dysfunction leads to shortened and misshapen cilia61–64. This condition compromised the localization and proper functioning of ciliary membrane proteins, along with their downstream signaling pathways, including Hedgehog62,64–66. Mutations in ARL13B have been found associated with the Joubert syndrome ciliopathy in humans and the loss of ARL13B function has been linked to the development of kidney cysts and dilation of renal tubules across various model organisms63,67,68. Nevertheless, the role of ARL13B ciliary GTPase in the efferent ducts has never been explored.

In the present study, we investigated the consequences of targeted deletion of Arl13b in the efferent ducts and determined the contribution of motile and non-motile ciliary organelles to epithelial and luminal homeostasis, whose disturbance caused a reduced fertility in the male depending on severity of induced pathology.

Results

ARL13B staining unveils the intricate interplay between PCC and MCC

Efferent ductule primary cilia are hidden among hundreds of tufted motile cilia and as solitary structures are easily missed by using immunofluorescence microscopy with common ciliary markers or conventional transmission electron microscopy (Fig.1A). To highlight their presence among motile cilia, we took advantage of the double transgenic mouse Arl13b-mCherry; Cetn2-GFP58, designed to enable in situ visualization of primary cilia (Fig. 1B–D). In cross-sections of efferent ducts from adult mice, ARL13B-mCherry-labeled ciliary extensions were detected at the surface of the epithelium, where the apical alignment of multiple CETN2-positive basal bodies discriminates the MCC (motile cilia) from the PCC (with primary cilia) (Fig. 1B). ARL13B-positive cilia extended from a basal body to enter in contact with the luminal compartment of the tubules (Fig. 1B). Individual cell boundary delineation through immunolabeling of ZO1 expressing tight junctions showed that ARL13B-positive primary cilia exclusively originate from the apical edge of PCC, adjacent to the MCC (Fig. 1C). While both efferent duct primary and motile cilia were detected through alpha-acetylated tubulin (AC-TUB) (Fig. 1D), endogenously labeled ARL13B molecules were strongly detected in primary cilia compared to motile cilia, which only display a faint signal (Fig. 1C), possibly due to either differences in expression or steric properties of the ARL13B-MCHERRY construct in the efferent ducts59,69,70. To differentiate between motile and primary cilia, we detected Dynein intermediate chain 1 (DNAi1), a marker specific to motile cilia, in the efferent ductules. This analysis revealed that DNAi1 is present in motile cilia but absent from primary cilia (Fig. 1E). Leveraging the inherent constraints of this double transgenic mouse model, our findings underscore the intimate physical interaction that exists between the solitary primary cilia and the numerous motile cilia in the epithelial ducts.

The ciliary protein ARL13B is lost in efferent ductules of Arl13b conditional Knock-out mice

ARL13B is a conserved membrane-associated GTPase that localizes along the cilium where it ensures ciliary protein transport and signaling65. To assess the contribution of ARL13B in both primary and motile cilia to efferent duct physiology and male fertility, we conditionally ablated the expression of Arl13b in the duct epithelial cells through the removal of exon 2 after breeding male VillinCre with female Arl13bFlox mice (Fig. 2A). The VillinCre promoter driver triggers recombinase expression specifically in efferent duct epithelial cells54, within the whole male reproductive system. This was confirmed by the endogenous fluorescent signals detected in PCC and MCC after breeding VillinCre with Rosa26 TdTomato mice (Ai14) (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Fig. 2. ARL13B is lost in the efferent ductules of Arl13b conditional KO mice.

A Schematic representation of the Arl13b conditional knock-out by the Cre-loxP system. Cell lineage specificity was provided by Villin-Cre mediated excision of the loxP-flanked Arl13b exon 2 to generate VillinCre; Arl13bFlox/Flox mice (cKO) and VillinCre; Arl13bFlox/+ control littermates (Ctl). B ARL13B Western blot detection in testis, EDs and epididymis protein extracts from Ctl and cKO mice. Box & whiskers plot showed protein quantification performed on ED extracts from n = 5 mice per genotype and normalized to GAPDH (right panel, center line: median, box limits: min to max); differences between Ctl and cKO were analyzed using unpaired t test. **p < 0.01. C Immunofluorescent detection of ARL13B (gray), alpha-acetylated tubulin (AC-TUB, red) and gamma tubulin (γ-TUB, green) in primary (arrowhead) and motile cilia (arrow) of EDs from Ctl and cKO adult mice. Note the absence of detection of ARL13B in both cilia in cKO mice. Scale bars = 10 µm. D Immunofluorescent detection of ARL13B (gray), alpha-acetylated tubulin (AC-TUB, red) and gamma tubulin (γ-TUB, green) in the EDs from 3, 8 weeks and 4 months old Ctl and cKO mice. While AC-TUB-positive cilia are observed in both Ctl and cKO mice (arrowheads), ARL13B-positive cilia are exclusively detected in EDs from Ctl mice (arrows). Scale bars = 10 µm; Ep. Epithelium; Lu. Lumen.

Because VILLIN, being a microvilli-associated protein, is also found in the kidney71,72, the development of renal cysts was observed in VillinCre; Arl13bFlox/Flox conditional knock-out mice (cKO) aligning with earlier studies conducted on Arl13b mutants67. According to Western-blotting quantification, the ARL13B levels were reduced by 4-fold on average in cKO mice vs. Control mice (Ctl) (Fig. 2B). While ARL13B protein was found in other organs of the male reproductive system, including the testis and the epididymis, its expression was reduced only in Villin-expressing efferent ducts (Fig. 2B). Efficient reduction of Arl13b expression was further validated by immunofluorescent staining of duct sections, where ARL13B could not be detected in primary or motile cilia from cKO mice (Fig. 2C). Depletion of Arl13b did not prevent ciliogenesis, as alpha-acetylated tubulin immunofluorescence revealed that both ciliary structures were present at the surface of the epithelium (Fig. 2C, D). Effective ARL13B removal was observed in mouse efferent ducts as early as 3 weeks of age and sustained until 4 months of age, the later time point analyzed in this study (Fig. 2D). Altogether these results validate the targeted deletion of Arl13b in the epithelial cells. Because the cKO mice were viable at 4 months of age, this in vivo model constitutes a useful tool for the study of ciliary functions in adult tissues.

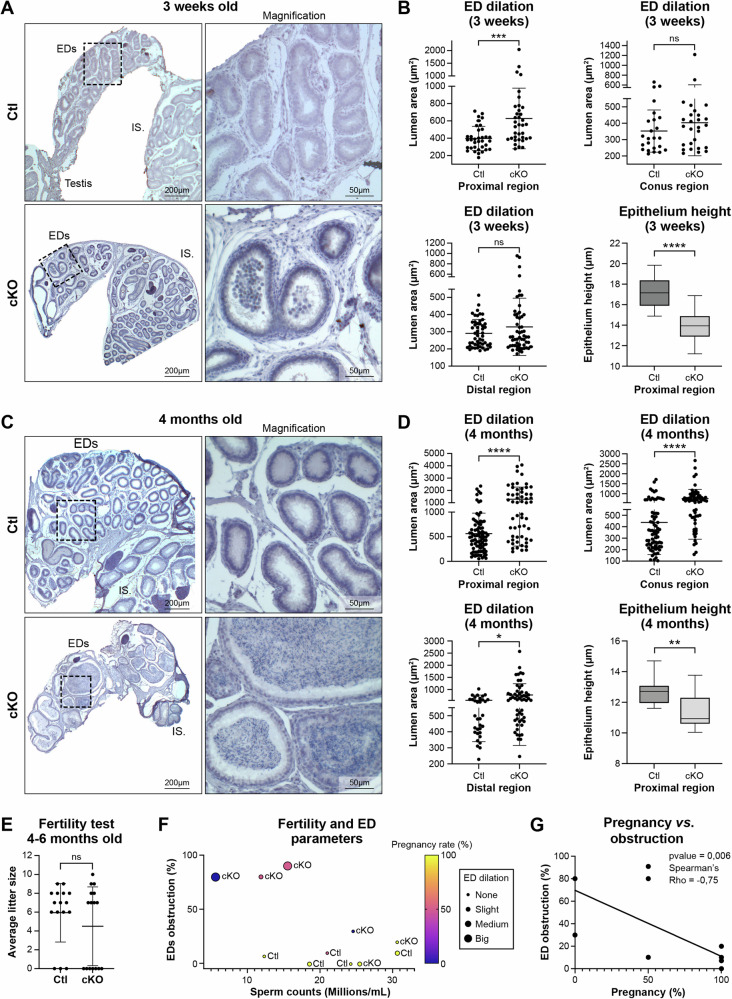

Arl13b deletion causes efferent ductule dilation and impairs reproductive outcome

Histological and quantitative analyses of efferent ducts from cKO mice at 3 weeks and 4 months of age revealed a significant dilation of the tubule lumens, together with a decrease in epithelial height (Fig. 3A–D). Before reaching puberty, the efferent ducts in cKO mice exhibited enlarged tubules specifically in the proximal segment attached to the rete testis, with no dilation in the conus and the distal common duct near the initial segment (IS) of the epididymis (Fig. 3B). The presence of rounded cells was additionally noted within the tubule lumens, usually downstream of the dilated areas in cKO mice (Fig. 3A). During this developmental stage, which precedes completion of the first wave of spermatogenesis, spermatozoa were absent in the lumen of both the efferent ducts and the epididymis. At 4 months of age, the dilation phenotype was notably accentuated, featuring consistently enlarged tubules, thinner epithelia, and the occurrence of sperm compaction in the lumen (Fig. 3C). However, the presence of spermatozoa in the cauda epididymis of most males indicated that at least one efferent duct lumen had maintained patency (Supplementary Fig. 2). The dilation of tubules, which initially was limited to the proximal region of the efferent ducts during early developmental stages of cKO mice, with aging progressively extended to the distal segments. Conversely, the reduction in epithelial height remained similar from 3 weeks to 4 months old mice (Fig.3B, D). Possibly contributing to the formation of these enlarged tubules, an elevated rate of proliferation affecting both types of epithelial cells was noted, along with dysregulation in the expression of oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes (Supplementary Fig. 3). Adult cKO mice displayed a diverse phenotype, ranging from mild to severe tubule dilation/sperm accumulation, and appeared to be linked to a variation in ductal pathology between the left and right sides. Because of this heterogeneity, the correlation between sperm or efferent duct parameters and fertility was determined for each animal (Fig. 3E–G). Fertility tests performed by mating Ctl (n = 8) or cKO male mice (n = 8) with wild type females, indicated that the average litter size (Fig. 3E) was not significantly different between Ctl and cKO mice; however, 2 cKO males were totally infertile and 2 were fertile in only one breeding trial. To decipher this phenotypic variability, correlation between the percentage of pregnancy rate and the total sperm count (measured in millions per milliliter) for each male was determined. Additionally, these findings were linked to the morphological phenotype of efferent ducts, focusing on tubular dilation and luminal obstruction (expressed as a percentage of males) (Fig. 3F). According to computer assisted sperm analysis (CASA) performed on sperm collected from the cauda epididymides, sperm counts were also highly heterogeneous in cKO mice, ranging from 5 million spermatozoa/ml when ductal occlusion was at a higher percentage to 30 million spermatozoa/ml when very few ducts were occluded (Fig. 3F). While about 65% of cKO males were able to produce offspring and displayed a normal sperm count and mild luminal dilation (Fig. 3F), we observed a strong negative correlation between the percentage of female mice which became pregnant versus the status of ductal obstruction (Fig. 3G). Despite the phenotypic heterogeneity observed in the severity of the cKO mice, these data show that in the absence of Arl13b efferent duct obstruction negatively impacts the pregnancy rate of mated females. Taken together, these results illustrate that depletion of epithelial Arl13b resulted in impairment of luminal homeostasis in the efferent ducts.

Fig. 3. Loss of ARL13B results in efferent ductules dilation and sperm accumulation that correlates with reduced pregnancy rate.

A, C Hematoxylin staining of EDs from Ctl and cKO at 3 weeks (A) and 4 months old (C). 20× magnifications are shown on the right. EDs: Efferent ductules. IS: Initial segment. B, D Luminal area and epithelial cell thickness were measured in distinct regions of EDs from Ctl and cKO mice at 3 weeks (B) and 4 months old (D). Unpaired-t test was used to analyze luminal area (the data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD)) and Mann-Whitney test was used to analyze epithelial cell thickness (data presented in box plot, center line: median, box limits: min to max), *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001. E Average litter size obtained after mating Ctl or cKO male mice with wild-type females is presented in mean with SD (ratio 2 females per 1 male). Difference between Ctl and cKO were analyzed with unpaired t-test. F Correlation matrix between the percentage of ED obstruction (in percent, 0% no obstruction observed; 100% all tubules obstructed with sperm clog), sperm counts (in millions/ml obtained from CASA analysis), tubule dilation (arbitrary units) and pregnancy rate (100%: 2 out of 2 females got pregnant, 50%: 1 out of 2 females got pregnant, 0%: none of the 2 females got pregnant) found in Ctl (n = 5) and cKO mice (n = 6). G Spearman’s Rho was employed to assess the strength and direction of the relationship between the levels of ED obstruction (number of tubules obstructed in percent, 0%: no tubules obstructed, 100%: all tubules obstructed) and the pregnancy success rate of wild type females mated with cKO males (100%: 2 out of 2 females got pregnant, 50%: 1 out of 2 females got pregnant, 0%: none of the 2 females got pregnant).

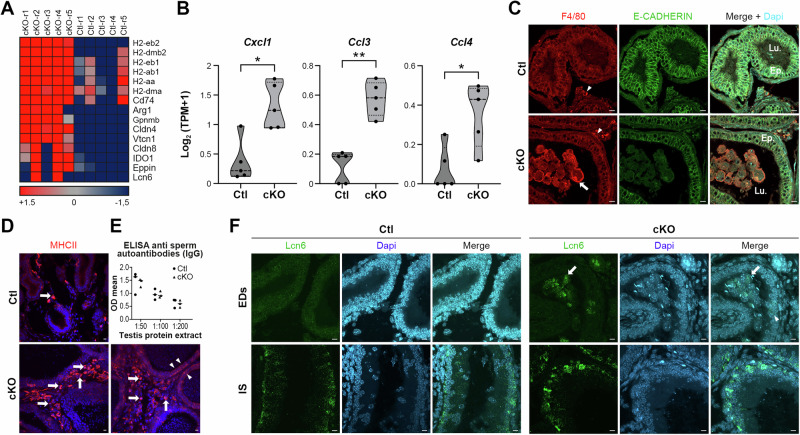

ARL13B sustains immune system homeostasis in the efferent ductules

The disruption of luminal homeostasis and sperm compaction suggested that an inflammatory response could be induced in the cKO efferent ducts, as can be seen when motile cilia are disrupted in this epithelium19,20,54. The formation of granulomas in this region is associated with leakage of the protective barrier formed by epithelial tight junctions and the recruitment of immune cells27,38,73. An upregulation of various immune-related genes was found in the cKO ducts compared to Ctl (Fig. 4A). Notably, important chemokines involved in macrophage recruitment, such as Cxcl1, Ccl3, and Ccl4 were found upregulated in cKO mice (Fig. 4B). Therefore, we explored the potential contribution of immune cells and mononuclear phagocytes to the pathophysiological changes observed in cKO mice. Immunofluorescence detection of F4/80-positive mononuclear phagocytes (F4/80 + ) revealed that few of these cells were present in the peritubular stroma of Ctl efferent ducts (Fig. 4C). However, the absence of Arl13b prompted the infiltration of F4/80+ mononuclear phagocytes into the lumen, where they engulfed spermatozoa (Fig. 4C). Furthermore, in cKO mice an increase in Major Histocompatibility Complex class II (MHCII)-positive cells was noted in the stromal area, with some also being identified in the epithelium (Fig. 4D). However, despite of this insult we were not able to identify anti sperm antibodies in the serum of cKO mice compare to Ctl tested against testis protein extract (Fig. 4E). The presence of immune cells in the ducts was also associated with an increased expression of well-known epididymal markers, including Lipocalin 6 (Lcn6), a member of a family with functions ranging from ligand binding to immune defense74. As evidenced by in situ hybridization in Ctl mice, Lcn6 transcript was undetected in the efferent ducts but present in the Initial segment (IS) of the epididymis (Fig. 4F). In cKO mice, Lcn6 transcript was not only detected in the IS of the epididymis but also in epithelial cells and somatic cells invading the lumen of the efferent ducts. In summary, these findings suggest that the depletion of Arl13b disrupts the balance of the immune system, leading to mononuclear phagocytes infiltration into the lumen area, and prompting specific epithelial cells to initiate the expression of various immune-related markers associated with the innate immune response.

Fig. 4. Loss of ARL13B is associated with unbalanced immunological environment in the efferent ductules.

A Heat map representation of immune and inflammatory related coding genes whose expression is altered in cKO mice. Color range indicates Log2FC ≥ 1.5 (upregulated genes); Log2FC ≤-1.5 (downregulated genes). B Cxcl1, Ccl3 and Ccl4 chemokines RNA expression level based on Log2(TPM + 1) showed in truncated violin plot (center line: median, small doted lines: first and third quartile) and analyzed with Mann-Whitney test. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01. C Immunofluorescent detection of mononuclear phagocytes (F4/80, red) in EDs of Ctl and cKO mice. Mononuclear phagocytes are present around the tubules (arrowheads) and infiltrate the lumen of cKO mice (arrow). Scale bars = 10 µm. D Immunofluorescent detection of antigen presenting MHCII (red) in EDs of Ctl and cKO mice. While MHCII positive cells are present in the stroma of both Ctl and cKO (arrows), some epithelial cells also express MHCII marker in the EDs from cKO mice (arrowheads). Scale bars = 10 µm. E Detection of IgG in the serum of Ctl and cKO mice (serum dilution 1:50, 1:100 and 1:200) against testicular proteins extracts measured with optical density (OD) mean. F In situ fluorescent detection of Lcn6 transcripts in EDs and initial segment (IS) from Ctl and cKO mice using RNA scope technology. While Lcn6 is only expressed in IS from Ctl mice, Lcn6 is found expressed in cells populating the lumen (arrows) and in epithelial cells of the EDs in cKO mice (arrowhead). Scale bars = 10 µm.

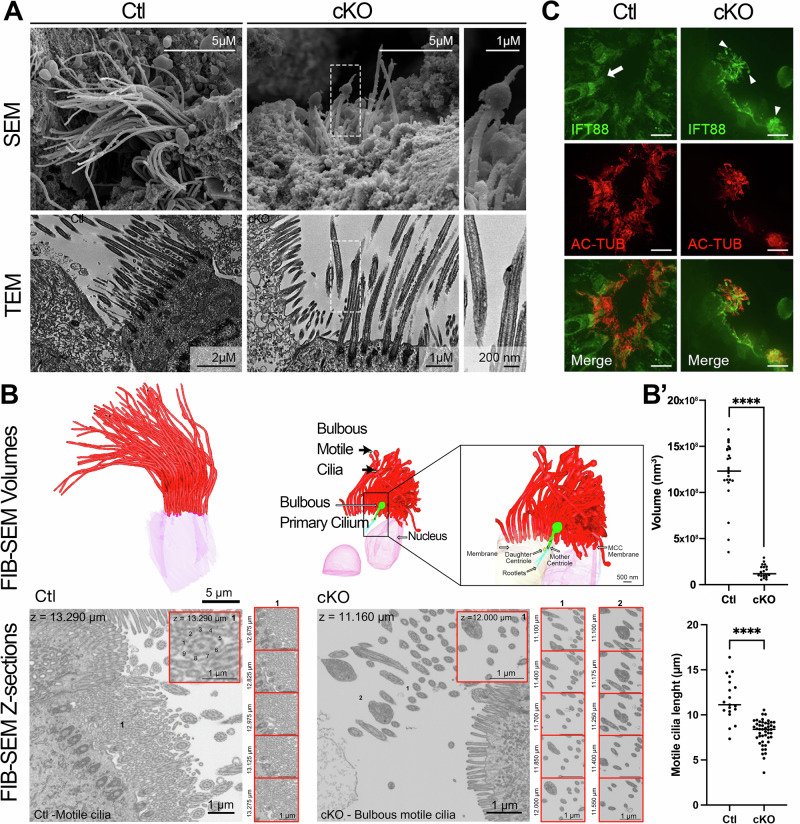

ARL13B is required for the structure of motile cilia in the efferent ductules

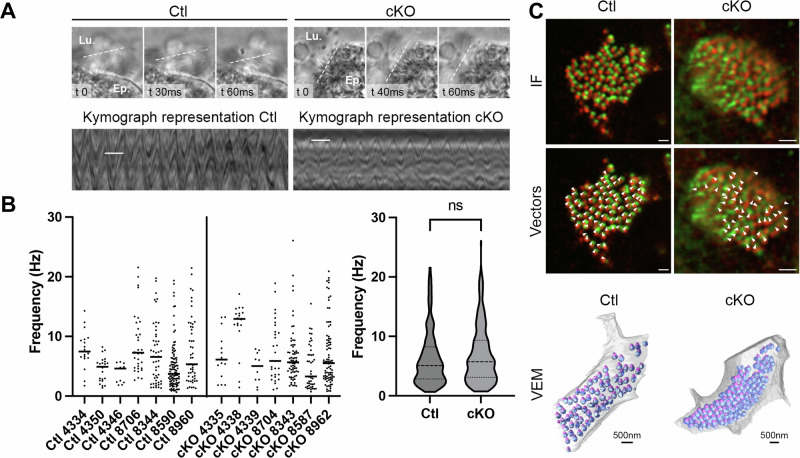

Beating of long motile cilia is essential for efferent duct luminal homeostasis1,19,22,38. Therefore, cilia extending from the duct MCCs were examined by electron microscopy and 3D Volume Electron Microscopy with image segmentation75 in Ctl and cKO mice. Motile cilia in Arl13b-deficient mice are significantly shorter than those in Ctl mice and display an irregular axonemal ultrastructure with apical bulges at their tips (Fig. 5A-B’ and Supplementary Fig. 4). In Ctl mice, the intraflagellar transport protein-B complex component IFT88 was distributed uniformly along the entire length of the motile cilia, as expected (Fig.5C). However, in cKO mice, a specific concentration of IFT88 was found at some protuberance sites where motile cilia also displayed kinks, resembling what was previously observed in sensory cilia from Caenorhabditis elegans (Fig.5C)64,76,77. Based on these structural abnormalities, we hypothesized that ciliary beat would be inhibited due to a hindrance in the transportation of ciliary components. Cilia beat frequency in the efferent ducts was measured using high-speed video microscopy (Fig. 6A, B and Supplemental Videos). Although the frequency varied across the different groups of mice, ranging from 1 to 21 Hz in Ctl and 1 to 26 Hz in cKO mice, no global change in beating frequency was observed between the 2 groups (Fig. 6B). Moreover, the coordination persisted as shown by the assessment of basal body alignment by fluorescence microscopy using basal body (POC1B) and basal feet protein (CENTRIOLIN) markers78 and 3D Volume Electron Microscopy with image segmentation in the efferent ducts from both Ctl and cKO mice (Fig. 6C). The potential effect of shorter cilia lengths on the movement of luminal contents was not determined.

Fig. 5. Motile cilia are structurally affected by the loss of ARL13B.

A Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) and Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) acquisitions of motile cilia from the EDs of Ctl and cKO mice. Motile cilia appear shorter in cKO and some of them exhibit a bulging morphology (shown in magnified images on the right). B 3D segmentation of volume electron microscopy (VEM) data acquired by FIB-SEM of EDs in both Ctl and cKO mice. Motile cilia (red) in cKO mice exhibit bulbous extremities, similar to those observed in the primary cilium (green). In the motile cilia of Ctl mice (inset), note the presence of 9 peripheral microtubule doublets and a central pair which are also present in the normal motile cilia of cKO mice (inset 1), but absent in the bulbous extremities (inset 2). B’ Motile cilia in cKO mice are significantly shorter than those in Ctl mice, as quantified by volumetric measurements from FIB-SEM data (center line: median; top panel) and fluorescent image analyses (center line: median; bottom panel). C Immunofluorescent detection of IFT88 in EDs from Ctl and cKO mice. While IFT88 is present all along alpha-acetylated tubulin (AC-TUB) motile cilia in Ctl EDs (arrow), it is found accumulated in the bulge of some motile cilia from cKO models (arrowheads). Scale bars = 10 µm.

Fig. 6. Cilia motility is not significantly impaired following the loss of ARL13B.

A Beating frequency of motile cilia was measured by high speed videomicroscopy (100 fps) on live efferent ductules (Supplementary videos 1 and 2). Beating frequency is illustrated by kymographs (bottom panel) obtained with Fiji software, with white lines showing a single wavelength. B The beating frequencies recorded within each group of mice (n = 7 per genotype) were heterogeneous and did not significantly differ between groups, as shown in the violin plot (center line: median; small dotted lines: first and third quartile) using the Mann-Whitney statistical test. C Airyscan images for immunofluorescent detection of basal feet (CENTRIOLIN, green) and basal bodies (POC1B, red) orientation in Ctl and cKO EDs. Vectors (Arrowheads) indicate beating directionality based on each cilium basal body/basal foot orientation (bottom panels). 3D reconstruction from VEM data of EDs of both Ctl and cKO showing basal bodies (blue) and basal feet (pink). Top panels scale bar=1 µm.

Arl13b is essential for maintaining the structure of primary cilia and ensuring proper fluid reabsorptive capacity

Luminal enlargement of the efferent ducts has been found to be associated with male infertility, primarily due to a defect in fluid reabsorption, controlled by key proteins found in the primary ciliated cells (former name; nonciliated cells)16,55. In our model, depletion of the ciliary protein ARL13B in the ducts was associated with a reduced expression of several genes encoding proteins involved in water reabsorption and ion transport, but not in some key proteins (Fig. 7A). Prior studies have focused on Slc9A3 (sodium/hydrogen exchanger 3) and Aquaporins 1 and 9 (Aqp1 and Aqp9) as the major contributors to maintenance of fluid homeostasis16,79,80. However, although heat map shows decreases in Slc9A3 and Aqp1 in some cKO mice compared to Ctl, the only mean significant declines were found in Aqp5 and several other ion transport genes that have not been previously described in the efferent ducts (Fig.7B). Amongst these, AQP5, previously undetected in rat and cat efferent ducts81–83 were downregulated in cKO mice. Through immunofluorescence targeting in Arl13b-mcherry;Centrin2-GFP transgenic mice, AQP5 was confirmed to be present at the apical pole of PCCs (Fig.7C). The fluorescence intensity of AQP5 protein at the apical pole of epithelial cells in the ducts was notably lower in cKO mice, compared to the Ctl group (Fig. 7D-D’). The decrease in AQP5 protein levels in cKO mice was further confirmed by dot blot assays, with antibody specificity validated through competition in the presence of excess immune peptide (Fig. 7E-E’ and Supplementary Fig. 5). Since impairment of microvilli formation could also cause an inhibition of fluid reabsorption, as observed following the loss of Esr138, the efferent duct epithelium was observed by electron microscopy but loss of Arl13b had no effect on microvillus ultrastructure (Supplementary Fig. 6A).

Fig. 7. The loss of ARL13B disrupts the regulation of factors involved in solute transport and fluid reabsorption.

A Volcano plot representation of ED RNA seq data from Ctl (n = 5) and cKO (n = 5) mice. Although certain less-studied genes encoding water channels, such as AQP2 and AQP5, were downregulated, the primary characterized channels in EDs, such as AQP1 and NHE3, did not show significant alterations following the loss of Arl13b. B Heat map representation of solute carriers and aquaporins encoding genes whose expression are downregulated (Log2FC ≤ -1.5, blue) or upregulated (Log2FC > 1.5, red) in cKO compared to Ctl mice. C AQP5 (gray) staining in EDs from Arl13b-mcherry; Cetn2-GFP transgenic mice showing the water channel at the apical pole of primary ciliated cells. Scale bars = 10 µm. D Immunofluorescent detection of AQP5 (green) in EDs from Ctl and cKO mice. Scale bars=10 µm. D’ Plot depicting the average fluorescence intensity of AQP5 at the apical pole of ED epithelial cells (center line: median), normalized through background subtraction. Difference between Ctl and cKO were analyzed using Mann-Whitney statistical test. ****p < 0.0001. E Dot plot quantification of AQP5 in two-fold serial dilutions of ED protein extracts from Ctl and cKO mice. To control for specificity, the antibody was pre-incubated with a 10-fold excess of the AQP5 immune peptide. E’ AQP5 dot blot quantification was performed on samples from n = 5 mice per genotype. Data were analyzed using Two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test on serial dilutions (see Supplementary Fig. 5). Only quantification for the 3 µg dilution is shown (Center line: median). ***p < 0.001.

Cystic Fibrosis Transmembrane Regulator (CFTR) also plays a role in fluid reabsorption and is present in the apical pole of PCC in rat and mice efferent ducts14,84. Following the loss of Arl13b, CFTR expression was not changed, but misplacement of the protein was noted, characterized by partial dispersion at the apical pole in both PCC and MCC. Remarkably, CFTR was also detected at the bulbous protuberance of motile cilia (Supplementary Fig. 6B). Lastly, ultrastructural examination of primary cilia found similarities in axonemal bulging and cilia bending similar to what is observed in the motile cilia (Fig. 5B and Supplementary Fig. 4). Collectively, these findings indicate that depletion of Arl13b resulted in morphological alterations in primary cilia and a reduction in unconventional water channels and ionic exchangers. These modifications are associated with changes in fluid reabsorption function, as evidenced by the observed luminal dilation phenotype.

Discussion

Efferent ductules in the male reproductive system are unique reabsorptive tubules, whose epithelium supports both motile and non-motile cilia in cells that are adjacent to one another31,32,35,37,38. While the pivotal role of motile cilia has predominantly been associated with the maintenance of a luminal turbulence in the control of male fertility19–23,54, the contribution of primary cilia has been overlooked, despite its major role in homeostasis in diverse organs85–87. ARL13B is a small GTPase found in both types of cilia, but it is commonly thought of as a primary cilium protein88. Therefore, with targeted impairment of Arl13b coding gene in the efferent ducts, we were able to examine how motile and primary cilia might contribute to distinct cellular features important to the overall physiology.

The role of ARL13B in the formation and structural maintenance of multiple motile cilia in the efferent ductules

Mutations of Arl13b have been linked to several diseases, including Joubert syndrome ciliopathy, and other pathological animal models in which the loss of this GTPase disrupts the cilia architecture61–64,89. ARL13B is involved in the formation of non-motile solitary (9 + 2) cilia in Caenorhabditis elegans62,64. Moreover, in the Arl13b-null mouse, fibroblasts and neural tube derived from the mouse embryonic node have shorter primary cilia due to an impairment of ciliary trafficking61,89. Although, ARL13B accumulates in motile cilia in the airway epithelium under the control of the distal appendage protein CEP16469, there is still a gap in our understanding regarding its contribution to ciliogenesis of the multiple motile cilia. Furthermore, endogenous mouse Arl13b was found confined to a proximal subdomain of motile cilia in oviduct and tracheal epithelial cells, supporting the notion that ARL13B is excluded from distal regions of certain ciliary subtypes, depending on axonemal diffusion restrictions90. In our study, ARL13B was present throughout the entire axoneme of motile and primary cilia and its absence in the efferent ducts led to significant alteration in structure of both the Multiciliated cells (MCC) and Primary ciliated cells (PCC). In the motile cilia, the accumulation of IFT88 in some bulbous protuberances along the axoneme (Fig. 5) was consistent with its role in the coordinated transport of IFT proteins, as documented in the (9 + 2) cilia phenotype in C. elegans arl-13b mutants62,64. Although the specific molecules associated with ARL13B in efferent ducts have yet to be identified, our findings indicate that this protein preserve the overall integrity of motile and primary cilia.

Within the efferent ductules, motile cilia are essential for creating fluid turbulence, which keeps immotile spermatozoa suspended within the lumen. When multiciliogenesis fails in these tubules, it leads to sperm aggregation and agglutination, ultimately resulting in luminal obstruction19. In the Arl13b cKO males, ductal occlusions were not caused by the loss of motile cilia, as seen with other animal models19–21. Instead, motile cilia were maintained, albeit occasionally appearing shorter. Furthermore, most parameters essential for normal motility, including the orientation of basal body/basal foot pairs91 and frequency, were retained. While further investigations will be requested to assess how fluid flow can be affected in the presence of shorter motile cilia in the cKO efferent ducts, they may not provide the necessary movement of luminal content that is required for rapid reabsorption of 90% of the fluid, illustrating an intricate cooperative function of the two adjacent cell types in efferent ductules.

Consequence of Arl13b deletion in the primary cilium on fluid reabsorption

Following the loss of Arl13b, notable changes in efferent ducts included luminal dilation and significant alterations in the expression of specific water channels (e.g., Aqp5, Aqp2), ion exchangers (e.g., Slc9c1, Slc2a3), and amino acid transporters (e.g., Slc6a16, Slc38a5). These findings suggest a role for this GTPase in regulating fluid reabsorption (Supplementary Fig. 7), a function strongly supported by the PCC. Consistent with our findings, other mouse models targeting water channels and ion transporters/exchangers in these ducts displayed a similar phenotype16,55. In the infertile Esr1 knockout mouse, there was dramatic dilation of the ductal lumens, with significant decreases in SLC9A3, AQP1, AQP9, CA2, and ATP1A1, which are key factors involved in fluid reabsorption55,92. Of these factors, efferent duct dilation was found only in the Slc9a3 and Ca2 knockout mice16. Although none of the aquaporin knockout mice have exhibited problems in the male reproductive tract or infertility16,93, AQP5 has been identified as important for water movement into the lumen in certain organs94, and its reduced expression can trigger severe inflammatory reactions95. In our study, it is possible that its presence at the apical pole of PCC could be important for preventing excessive water reabsorption96,97. Consequently, the decreased expression of AQP5 in Arl13b cKO males might have resulted in diminished water reabsorption by the efferent ducts and could have contributed to the observed inflammatory response observed in our model.

The chloride channel Cystic Fibrosis Transmembrane conductance Regulator (CFTR), was also affected in the cKO efferent duct. Although the mRNA level expression was unchanged, the protein was diminished at the apical membrane in PCCs and was unexpectedly found in the motile cilia bulbous protuberances. As an important ion transporter, it provides luminal fluid homeostasis primarily by Cl- secretion, but also by numerous complex interactions with other channels, transporters and even aquaporins98,99. Although CFTR is abundant in the efferent duct epithelium84,100–102, little has been known of it function in this specific organ. A study utilizing in vitro efferent duct ligation experiments established a connection between CFTR function/scaffolding and proteins associated with the primary cilium84. For instance, β-Arrestin-1, which is recruited to the primary cilium and presents a disturbed localization in the ciliopathy Bardet-Biedl syndrome103–106, was found to support the proper localization of CFTR and its co-localization with ADGRG2 (GPR64 or HE6)84, whose mutation results in luminal dilation of the efferent ducts84. Moreover, knockout of β-Arrestin-1 disrupted the CFTR/ADGRG2 interaction, leading to the displacement of CFTR away from the microvilli84. Other GTPases, such as Rab35 and 11, play a role in regulating CFTR delivery to the apical membrane in Kupffer’s vesicles in zebrafish107. Taken together, these findings suggest that CFTR displacement in the cKO mouse could be a secondary consequence of primary ciliary dysfunction and may cause nonfunctional chloride (Cl-) transport into the lumen compartment, directly contributing to excessive resorption due to an imbalance in chloride levels. While these findings bolster the notion that primary cilia play a role in efferent ductule fluid homeostasis, further investigation will be necessary to elucidate how primary cilia signaling influences the expression and localization of critical channels and transporters involved.

Role of ARL13B in the control of ED immune balance

The depletion of Arl13b also led to an inflammatory reaction in the efferent ducts, with a marked upregulation of genes coding for immune and inflammatory cells (Supplementary Fig. 7) and important chemokines involved in macrophage recruitment, such as Cxcl1, Ccl3, and Ccl4. The infiltration of F4/80-positive mononuclear phagocytes into the ductal epithelium and luminal compartment indicates an imbalance in the immunological environment. At first, we hypothesized that the observed ductal occlusions may have induced an auto-immune response to the accumulation of sperm within the lumen. However, this hypothesis was rejected, as IgG autoantibodies against testicular antigens were absent in 4-month-old cKO mice and luminal macrophage-like round cells were observed as soon as 3 weeks of age in cKO mice. Thus, an imbalance in physiological homeostasis, rather than sperm blockage, elicited an early immune response that worsened as the males entered puberty.

Our study identified a negative correlation between mononuclear phagocytes presence and pregnancy rate which was low in cKO mice, suggesting a detrimental impact on male fertility. While immune-related infertility accounts for nearly 15% of infertility in men, mainly due to the presence of autosperm antibodies, infections affecting the male reproductive tract or autoimmune diseases108,109, little is known regarding the role of immune cells in the efferent ducts. Following the loss of Arl13b, there was an increase in the expression of immune cell markers, including MHCII, Lcn6, Arginase1 (Arg1) and Gpnmb, which may be secondary to the insult observed in these tubules110–112.

The contribution of inflammation to dilation of the efferent duct lumen is not known but treatment of rats with a phosphodiesterase-4 (PDE4) inhibitor, recognized for its ability to induce inflammation, caused an initial dilation of the lumens with subacute interstitial inflammation, which was followed by more severe inflammation and the formation of sperm granuloma113. This lead to the hypothesis that potential immune-like cells in efferent ducts of the prepubertal cKO males could have somehow contributed to the early dilation of the lumens. The suggested unbalance of fluid composition observed through misregulation of fluid transporter (AQP5, CFTR and other undescribed genes) could have worsen the dilation of phenotype with age. These results suggest that more than one factors contribute to the dilation, sperm compaction and inflammatory phenotype observed in cKO male mice. Moreover, it prompts inquiries into the possible involvement of immune cells in maintaining immunotolerance towards transiting immunogenic spermatozoa, while simultaneously retaining the ability to efficiently combat ascending pathogens, as observed in the epididymis114,115.

Conclusion

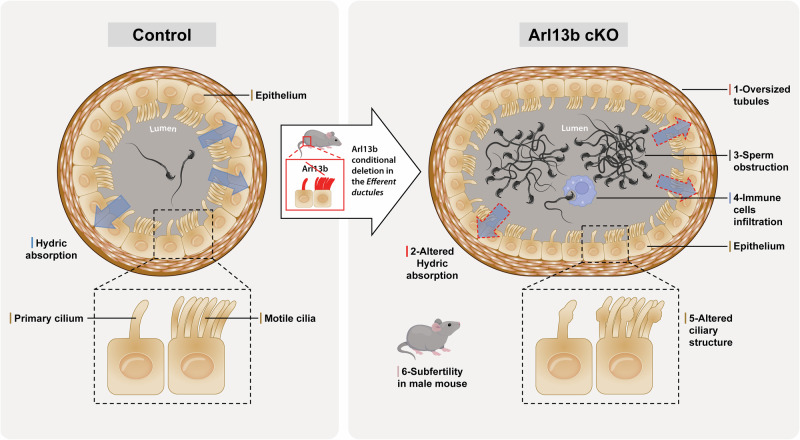

Our findings highlight that ARL13B, a GTPase present along the axonemes of both motile and primary cilia, plays a role in controlling physiological functions that are highly relevant to the regulation of efferent ductule physiology and male fertility (Fig. 8). A functional coordination between these two types of organelles is supported by the complex phenotype of the Arl13b cKO that mixes phenotype features of genes targeted in PCC and MCC only. In the future, the implementation of functional studies, particularly targeting the primary cilium, will aid in identifying factors dependent on primary cilia and uncover potential new targets for enhancing the diagnosis and treatment of male reproductive issues.

Fig. 8. ARL13B controls efferent ductules physiology.

The absence of ARL13B led to disturbances in reabsorptive/secretory processes characterized by enlarged tubules and dysregulation of water channels and ionic exchangers and triggered an inflammatory response. In the absence of ARL13B, both motile and primary ciliogenesis are impaired, resulting in bulbous cilia and increased in cilia beating. Furthermore, subfertility in cKO male mice correlates with the severity of affection in the efferent ductules.

Methods

Ethics approval

Animal studies were performed in accordance with a protocol approved by the Committee on Animal Research and Ethics of the Université Laval, Canada (CPA 2020-672). Mice were housed and maintained under specific pathogen-free conditions in a temperature- and humidity-controlled animal facility in Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Québec (CHUQ) and supplied with food and water ad libitum. We have complied with all relevant ethical regulations for animal use in accordance with the requirements defined by the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Animals

The Mus musculus mouse strains utilized included Arl13bFlox/Flox animals possessing exon 2 of the Arl13b gene flanked, allowing its deletion through cre recombinase (generously provided by Dr. Tamara Caspary, Emory University School of Medicine; Jackson Laboratory stock #031077). Females were mated with B6;D2-Tg(Vil-Cre) 20Syr male, obtained from the Mouse Models of Human Cancers Consortium (MMHCC; National Cancer Institute-Frederick, Frederick, MD). The latter mice express Cre under the control of a 9-kb region of the murine Villin promoter116. All mice of control genotypes (i.e., VillinCre and Arl13bFlox/Flox and VillinCre; Arl13bFlox/+) have been examined and exhibit the same phenotype. Phenotypes from the resulting conditional knock-out mice (VillinCre; Arl13bFlox/Flox, named cKO throughout the manuscript) were compared to littermate controls (named Ctl throughout the manuscript). Double transgenic mice, Tg(CAG-Arl13b/mCherry)1Kvand Tg(CAG-EGFP/CETN2)3-4Jgg/KvandJ, commonly named Arl13b-mcherry; Centrin2-GFP were used (Jackson Laboratory stock #027967) to visualize primary cilia and centrioles in the efferent ductules (EDs)37,58. The Ai14 mouse is a cre reporter tool (Jackson Laboratory stock #007914) that expresses red fluorescent protein variant (tdTomato) after breeding with Cre mice. Genotyping for VillinCre; Arl13bFlox mice was performed routinely, using primers described for each gene116,117. The list of primers can be found in Supplementary Table 1. The male mice were studied from 3 weeks to 10 months of age.

Fertility test

Fertility tests were performed on n = 8 Ctl and n = 8 cKO male littermates. Males were individually caged at 4 and 6 months old with two C57Bl6 females for 5 days, and mating was confirmed by the presence of a copulatory plug. The evaluation of fertility was determined based on the litter size, measured as the number of pups per litter.

Tissue fixation and immunofluorescent analysis

The entire genital tract was submerged in 4% paraformaldehyde overnight at 4 degrees. After fat tissue removal, the male reproductive components—testes, efferent ductules, and epididymis—were either cryopreserved overnight with sucrose 30% or dehydrated prior to their respective embedding in optimal cutting temperature compound (O.C.T. compound, 23-730-571, Fisher scientific) or paraffin (TissuePrep™ Embedding Media (Certified), T56-5, Fisher Chemical, discontinued).

Consecutive immersions in xylene and ethanol baths were performed for deparaffinization. When needed, antigen retrieval was conducted at 110 °C for 10 min using either Citrate buffer (10 mM sodium citrate, 0.05% Tween 20, pH 6) or Tris-EDTA Buffer (10 mM Tris base, 1 mM EDTA solution, 0.05% Tween 20, pH 9). After rehydration, both paraffin and O.C.T.-embedded sections were treated with 1% (w/v) sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) and 0.1% (v/v) Triton X-100 in PBS for 4 min at room temperature and washed with PBS for 5 min. After blockade in 5% bovine serum albumin and 3% goat serum in PBS for one hour, the primary antibody was diluted in DAKO solution (DAKO Corporation, USA) and incubated overnight at 4 °C. The primary antibodies used are listed in Table 1. Sections were washed twice in high-salt PBS (2.7% NaCl) for 5 min and then immersed in PBS for 5 min. The secondary antibodies (Table 2) were then applied for 2 hours at room temperature. After several washes, slides were mounted with Vectashield containing DAPI (VECTH1200, MJs BioLynx). Images were acquired using a Zeiss LSM900 confocal microscope equipped with Airyscan high-resolution capability (Zeiss; Toronto, ON, Canada). For basal body/basal feet immunostaining, mouse EDs were dissected and fixed by cold methanol fixation for an hour then tissues were proceeded as detailed for cryosections.

Table 1.

List of primary antibodies and peptides used in this study

| Name of antibody/peptide | Species | Company and number | Specificity | Dilution Immunoblots | Dilution IHC/IF | Antigen retrieval |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alpha-acetylated tubulin | Mouse | Sigma-Aldrich (T7451, clone 6-11B-1). | Monoclonal | 1/500 | No | |

| AQP5 | Rabbit | Alpha Diagnostics (AQP51-A). Lot: 124950A7.6-P. | Polyclonal | 1/100 | 110° for 10 min pH9 | |

| AQP5 peptide | Rat | Alpha Diagnostics (AQP51-P). Lot: 4489P3-P. | N/A | Varying (13 µg, 100 ng, 50 ng, 25 ng, 12.5 ng, and 6.25 ng) | ||

| Arl13b | Rabbit | Proteintech (17711-1AP). Lot : 00142161. | Polyclonal | 1/1000 | 1/250 | No |

| CFTR | Rabbit | Alomone Labs (ACL-006). Lot : AN1302. | Polyclonal | 1/100 | 110° for 10 min pH6 | |

| CFTR peptide | N/A | Alomone Labs (BLP-CL006). | N/A | Ratio 2 :1 | N/A | |

| DNAi1 | Rabbit | Abcam (171964). Lot: GR220370-9 | Monoclonal | 1/50 | 110° for 10 min pH6 | |

| Gamma-Tubulin | Mouse | Abcam (ab27074). Lot : 1016136-1. | Monoclonal | 1/200 | No | |

| GAPDH | Mouse | Novus Bio (NB300221). | Monoclonal | 1/5000 | N/A | |

| IFT88 | Rabbit | Proteintech (13967-1-AP). Lot : 00114143. | Polyclonal | 1/200 | 110° for 10 min pH6 | |

| MHCII | Rat | Thermo Fisher Scientific (12-5321-81). | Monoclonal | See Barrachina et al115, | ||

| PCNA | Mouse | Abcam (PC10-ab29). Lot :GR3195972-3. | Monoclonal | 1/200 | No | |

| Villin | Rabbit | Abcam (ab130751). Lot : 1036339-12. | Monoclonal | 1/1000 | 1/200 | No |

| ZO-1 (ZO1-1A12) | Mouse | Thermofisher (33-9100). Lot : WG329571. | Monoclonal | 1/200 | No | |

Table 2.

List of secondary antibodies used in this study

| Name of antibody | Company | Dilution |

|---|---|---|

| Alexa Fluor 647- conjugated AffiniPure Donkey Anti-Mouse IgG, 715-606-150 | Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories | 1/500 |

| Alexa Fluor 647-conjugated AffiniPure Goat Anti-Rabbit IgG, 111-605-144 | Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories | 1/500 |

| Fluorescein (FITC)-conjugated AffiniPure Donkey Anti-Rabbit IgG, 711-095-152 | Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories | 1/500 |

| AlexaFluor 488 Goat Anti-Mouse IgG1(γ1), A-21121 | Invitrogen | 1/500 |

| AlexaFluor 568 Goat Anti-Mouse IgG2b (γ2b), A-21144 | Invitrogen | 1/500 |

| Goat anti Rabbit HRP, 111-035-045 | Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories | 1/5000 and 1/10000 |

| Goat anti Mouse HRP, 115-035-062 | Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories | 1/5000 |

Histologic evaluation

Hematoxylin & Eosin (H&E) staining was employed to assess ED general morphology. Sections (10 µm) were stained using Hematoxylin Solution, Harris Modified (HHS32, Sigma-Aldrich), and counterstained using Eosin. Slides were imaged with a phase contrast microscope Zeiss Axioskop 2 plus (Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) linked to a digital camera (Diagnostic Instruments, USA). Images were captured using Spot software. The size of ED dilation was assessed by utilizing Fiji118 to measure the area of the lumen in µm² from minimum 5 cross-sectioned tubules in three distinct parts (e.g., proximal, conus, distal) for each animal. Epithelium heights were determined by drawing a line from the base of the epithelial cells to the apical pole and measured with Fiji.

Immunoblotting

Twenty micrograms of total protein from testis, ED and epididymis of Ctl and cKO mice were used in Western blot assays. Following SDS-PAGE, proteins were transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes through a semi-dry transfer system (Trans-Blot turbo, Bio-Rad). After a blocking step in 5% milk for 1 hour, membranes were immunoblotted with the primary antibody overnight at 4 °C, washed three times in PBS 0,05% Tween and incubated with the secondary antibody for 1 h at room temperature. After three additional washes, signal was revealed using a chemiluminescence reagent (170-5061, Bio-Rad) on a ChemiDoc MP Image system (Bio-Rad) and analyzed using ImageLab 6.0.1 software. GAPDH was used as a loading control.

For dot plot analyses, protein extracts from EDs at varying concentrations (ranging from 3 µg to 0.1875 µg) were loaded as 2 µL dots onto nitrocellulose membranes. The membranes were washed in TBS-T and blocked with 5% milk in TBS-T for 1 h at room temperature. Subsequently, the membranes were incubated with the rabbit anti-AQP5 primary antibody, diluted 1:1000 (0.13 µg) in 2.5% BSA/TBS-T. As a labeling control, membranes were incubated with the anti-AQP5 antibody that had been pre-incubated for 1 hour with 1.3 µg of the corresponding blocking peptide (AQP51-P, Alpha diagnostic international). After washing with TBS-T, the membranes were exposed to the goat anti-rabbit HRP secondary antibody, diluted 1:10000 in 2.5% milk/TBS-T. The reaction was visualized using ECL, following the standard protocol.

Detection of serum IgG by Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

Blood was collected from the heart of anesthetized mice using isoflurane (533-CA2L9100, Baxter) and transferred into tubes with Serum Gel (CAT 41.1378.005, Sarstedt). After incubating at room temperature for a minimum 30 minutes, the samples were centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 10 min to obtain serum. Proteins were extracted from testis of wild type mice using a buffer containing RIPA buffer (50 mM tris HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 1%NP40, 0,5% Sodium deoxycholate, 0,1% SDS), supplemented with a protease and a phosphatase inhibitor cocktail inhibitor cocktail (Protease and Phosphatase Inhibitor Mini Tablets, EDTA-free, A32961, Pierce). After mechanical extraction using a pestle, the samples were kept on ice for 30 min and then centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 15 min at 4 °C. The supernatants containing soluble proteins were collected. 96-well plates (half area, 96 wells, #675061, Greiner) were coated with testicular proteins at a concentration of 6 µg/mL in PBS, pH 7.4, for 16 h at 4 °C. Plates were blocked with 3% BSA in PBS for 1 hour at 37 °C before incubating with mouse serum diluted 1/50, 1/100, and 1/200 in 1% BSA in PBS overnight at 4 °C. The bound mouse IgG were detected after 1 hour of incubation with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG. 3,3’,5,5’-tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) was used as the HRP substrate (TMB substrate kit, 34021, Thermo Fisher Scientific). The enzymatic reaction was stopped with 2 N H2SO4, and the optical density was measured in duplicate using a microplate reader (Spark 10 M, Tecan) at 450 nm.

Electron microscopy

Following anesthesia with ketamine/xylazine (0,1 ml/30 g), mice were intracardially perfused with PFA 4%/PBS solution (w/v). ED were dissected, sectioned into small fragments ( ~ 1 mm3), and postfixed for 24 h with buffered EM grade glutaraldehyde solution (2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0,1 M sodium cacodylate buffer).

For transmission electron microscopy (TEM), tissue fragments were treated with 2% osmium tetroxide aqueous solution for 1 h, dehydrated in EM grade ethanol, and embedded in epoxy resin. Ultrathin sections (40 to 80 nm thickness) were meticulously prepared and examined at the UFMG Microscopy Center (Brazil). Analysis was conducted using a Tecnai-G2-Spirit FEI/Quanta electron microscope operating at 120 kV.

For scanning electron microscopy (SEM), tissue fragments were postfixed in 1% osmium tetroxide aqueous solution for 1 h, dehydrated in EM grade ethanol, and critical-point dried with CO2 for 45–60 min. Samples were then mounted on aluminum stubs and coated with gold nanoparticles (3 nm). SEM images were acquired on a FEI Quanta 3D FEG Dual Beam microscope, located at the UFMG Microscopy Center (Brazil).

FIB-SEM and 3D segmentation

ED tissues were fixed and embedded according to established protocols91. The resin embedded samples were sectioned and stained with toluidine blue to identify regions of interest for FIB-SEM imaging. The trimmed and mounted specimens on a standard SEM stub were then sputter coated with ~10 nm carbon and imaged briefly in SEM mode (Zeiss Crossbeam 550) to locate these regions. The cells of interest were then coated by a protective patterned platinum pad and subjected to automated FIB milling and SEM imaging cycles, according to established protocols119. The FIB was operated at 30 kV and current set to 1 nA; the SEM was operated at 1.5 kV and current 1 nA; the EsB detector voltage was set at 750 V. Images were acquired at 5 nm pixel sampling and 15 nm z “slice thickness”, at a total dwell time of 3 ms per pixel. Once the data run was executed, the relevant images were aligned using in-house scripts, contrast inverted, and binned by 3 in xy to yield a final volume EM dataset at 15 nm isotropic voxel sampling. Images were acquired as a series of z-slices and were aligned using Etomo, the graphical user interface (GUI) to the IMOD package120. 3D segmentation of cilia, cellular membranes and nucleus were performed manually with 3dmod within the IMOD package75,120. Manual segmentation was aided with interpolation at approximately every tenth slice to ensure continuity. For segmentation of basal feet and basal bodies, a deep-learning-driven approach was applied using the Empanada-Napari Plugin121. To build image models for automated segmentation, manually segmented patches containing basal bodies and basal feet (256 ×256 pixels each) on 2D images were first used as a training set. After running 3D inference, the segmentation masks identified by the software were checked to ensure accurate annotation. The final segmentation masks were then binned by three, converted to .tiff files and visualized in 3dmod using the isosurface rendering dialog function.

Correlation analysis

To address the phenotypic heterogeneity observed in cKO mice, we investigated the correlation between various parameters, including fertility, sperm parameters, ED obstruction, and ED dilation. The correlation of these individual parameters was conducted on n = 5 Ctl and n = 6 cKO mice.

Computer assisted sperm analysis (CASA analysis)

Sperm were allowed to swim out from cauda epididymis of Ctl and cKO mice after incubation in 500 µl of Whittens media (pH7.4 and osmolarity 300 mOsm) at 37 degrees. Total sperm count and sperm motility were analyzed following manufacturer instructions using the Microptic Nikon eclipse Ci (camera Basler acA1300-200uc (24031536)) operating with the software SCA V6.6.0.5 (Microptic, Barcelona, Spain).

RNA sequencing

Total RNA was extracted from total EDs of 4-month-old mice (n = 5) using Qiagen RNeasy Mini Kit. Samples were eluted in 20 µl of RNase-free H2O, RNA concentration and quality (RIN ≥ 8) was determined under the Agilent 2100 BioAnalyzer (Agilent Technologies, USA) by the CHUL genomic facility (Centre de génomique du CHU de Québec-Université Laval, Québec, CANADA). Reads were trimmed using fastp v0.20.0. Quality control was performed on raw and trimmed data to ensure the quality of the reads using FastQC v0.11.8 and MultiQC v1.8. The quantification was performed with Kallisto v0.46.2 against the Mus musculus transcriptome (downloaded from Ensembl release 101). Differential expression analysis was performed using the DESeq2 v1.30.1 package with a threshold of 1,5 of Log2 (fold change) and an adjusted p-value < 0.05. All R analyses were done in R v4.0.3.

RNA scope

RNAscope Multiplex Fluorescent Reagent Kit v2 was used to perform the experiments following the manufacturer’s protocol (Advanced Cell Diagnostics). Paraffin-embedded tissue sections of 5 μm of EDs and initial segment were incubated with Protease Plus for 30 min at 40 °C. After washes, Lcn6 (Mm-Lcn6-O1-C1, 1100321-C1) and negative control probes (320871) were added on the tissues and the slides were incubated in a humid incubator at 40 °C for 2 h. Slides were washed and kept in a saline sodium citrate solution (0.75-M NaCl, 0.380-M sodium citrate, pH 7.0) overnight. After washes, slides were successively incubated with Amp 1, Amp 2, and Amp 3 solutions for 30, 30, and 15 min, respectively, at 40 °C. Tissues were washed between each step. Each probe signal was revealed in its corresponding channel (C1 or C2 depending on the probe). Tissue sections were incubated with HRP-C1 or HRP-C2 for 15 min at 40 °C, washed and incubated with the diluted fluorophore, Opal 520 or Opal 570, for 30 min at 40 °C. Slides were washed and incubated with the HRP blocker for 15 min at 40 °C. Signal development was performed the same way for the other probe. After several washes, slides were mounted with Vectashield containing DAPI (VECTH1200, MJs BioLynx), dried and stored at 4 °C until imaging.

Videomicroscopy of ciliary beating

The whole EDs were freshly dissected to carefully remove the connective tissue under a microscope in HBSS solution (SH30588; HyClone). EDs were mounted in a culture dish with a round coverslip in a drop of HBBS (no. 0420041500B, Bioptechs) and placed on an inverted microscope (Zeiss Axio Observer Z1) equipped with a warming plate set at 35 °C. Cilia beating was recorded with a high-speed camera (Hamamatsu ORCA-Flash4.0, no. C13440-20CU) at 63× magnification with oil immersion, capturing at a rate of 100 frame per second. Recordings were analyzed using Fiji software. Using ImageJ, kymographs illustrating cilia motility were created from each video. These kymograph images, derived from individual ciliated cells, were then analyzed to ascertain the frequency of cilia beating. Frames per second were divided by the length of the line between two peaks, as previously outlined122. At least six videos were analyzed for each sample.

Statistical and reproducibility

The sample size was determined using G*Power 3.1 software, employing the parameters for a two-tailed t-test measuring the mean difference between two independent means. The effect size (d) was set between 2 and 3 with an alpha error probability of 0.05 and a power (1-beta error probability) of 0.95. The resulting sample size varies from 3 to 8 mice per group. Each mouse corresponds to one biological replicate, and the number of biological replicates is in accordance with the sample size calculation. Each set of experiments were performed on minimum 3 biological replicates of control and cKO mice. For immunostaining, experiments were also performed in a minimum of 2 independent replicates. All attempts of replication were successful. Data distribution was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test and Q-Q plots. Parametric analysis between the control and cKO group was conducted using unpaired t-test, while non-parametric comparisons between groups were performed using the Mann-Whitney test. All analyses were performed in the GraphPad Prism software version 10.1.1, with a significance threshold set at p < 0.05. In addition, Spearman’s Rho was employed to assess the strength and direction of the relationship between two variables and we used the Spearman’s Rho Calculator (2024, February 14) retrieved from [https://www.socscistatistics.com/tests/spearman/default2.aspx] using a p < 0.05 as the significance threshold.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Acknowledgements

We express our gratitude to Dr. Sylvie Breton and Christine Légaré for providing access to imaging equipment’s (supported by the Canada Foundation for Innovation grant GF125973 to Sylvie Breton). We are thankful to Dr. Tamara Caspary for providing us with the Arl13bFlox mouse model used in this study. We extend our appreciation to Sophie Vachon and Dr. Ezequiel Calvo for their respective assistance in mouse colonies maintenance and in RNA-seq data analysis. Additionally, we would like to thank Tania Lévesque for her assistance in harvesting mouse blood samples. We are thankful to interns Katherine Simoneau and Marielle Caron for their experimental support. Furthermore, we are grateful to Dr. Eric Boilard and Dr. Isabelle Allaeys for their invaluable discussions and guidance in designing immunology-related experiments. This study was financially supported by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) operating grant IC119871 and Fonds de recherche du Québec - Santé (FRQS)-Junior 2 salary grant to CB. CA was financially supported by a Lalor foundation, a Fonds de recherche du Québec – Nature et Technologies (FRQNT) B3X and a Réseau Québecois en Reproduction (RQR) postdoctoral fellowships. This project has also been funded in part with Federal funds from the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health (Contract No. 75N91019D00024 to K.N.) and by the National Institutes of Health (grant HD104672-01 to M.A.B.).The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. Government.

Author contributions

C.A., R.H., V.M., and C.B. contributed to conception and design of the work; C.A., G.C.S., C.L.O., A.V., O.M., K.N., F.B., K.O., M.A.B., R.H., V.M., C.B. contributed to acquisition and analysis of biological data; C.J.B., A.D., G.C.S. contributed to bioinformatics data analysis; CA and CB wrote the first draft of the manuscript; All authors contributed to manuscript revision.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Biology thanks Liling Qian and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Joao Valente. A peer review file is available.

Data availability

All data generated during this study are included in either the published article or its additional files and are available on request. All raw data used for the RNA seq analysis can be found online on the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) repository (GSE256400). Uncropped and unedited blot image can be found in Supplementary Fig. 8. Numerical source data for graphs and charts can be found in supplementary data.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Inclusion & Ethics

This research adheres to principles of inclusivity, diversity, and ethical conduct. During the course of this study, we maintained the highest standards of integrity, honesty, and respect of all researchers and trainees involved. We are committed to transparency and accountability in our research practices and welcome feedback and inquiries regarding our methods, findings, and implications.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Rex Hess, Vito Mennella.

Contributor Information

Céline Augière, Email: Celine.Augiere@crchudequebec.ulaval.ca.

Clémence Belleannée, Email: Clemence.Belleannee@crchudequebec.ulaval.ca.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s42003-024-07030-7.

References

- 1.Hess, R. A. The efferent ductules:Stucture and functions. The Epidid (2002).

- 2.Hess, R. A., Sharpe, R. M. & Hinton, B. T. Estrogens and development of the rete testis, efferent ductules, epididymis and vas deferens. Differentiation118, 41–71 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Newcombe, N., Clulow, J., Man, S. Y. & Jones, R. C. pH and bicarbonate in the ductuli efferentes testis of the rat. Int J. Androl.23, 46–50 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sullivan, R., Légaré, C., Lamontagne-Proulx, J., Breton, S. & Soulet, D. Revisiting structure/functions of the human epididymis. Andrology7, 748–757 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hess, R. A. & Cooke, P. S. Estrogen in the male: a historical perspective. Biol. Reprod. 99, 27–44 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Ball, R. Y. & Mitchinson, M. J. Obstructive lesions of the genital tract in men. J. Reprod. Fert.70, 667–673 (1984). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McEntee, K. Reproductive Pathology of Domestic Mammals. (1990).

- 8.Rajalakshmi, M., Kumar, B. V. R., Ramakrishnan, P. R. & Kapur, M. M. Histology of the epididymis in men with obstructive infertility Nebenhoden-Histologie bei Mannern mit Verschlul3 der ableitenden Samenwege. Andrologia22, 319–326 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pal, P. C. et al. Obstructive infertility: changes in the histology of different regions of the epididymis and morphology of spermatozoa. Andrologia38, 128–136 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Omotehara, T. et al. Expression patterns of sex steroid receptors in developing mesonephros of the male mouse: three-dimensional analysis. Cell Tissue Res.393, 577–593 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clulow, J., Jones, R. & Hansen, L. Micropuncture and cannulation studies of fluid composition and transport in the ductuli efferentes testis of the rat: comparisons with the homologous metanephric proximal tubule. Exp. Physiol.79, 915–928 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Joseph, A., Shur, B. D., Ko, C., Chambon, P. & Hess, R. A. Epididymal hypo-osmolality induces abnormal sperm morphology and function in the estrogen receptor alpha knockout mouse. Biol. Reprod.82, 958–967 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hansen, L. A., Dacheux, F., Man, S. Y., Clulow, J. & Jones, R. C. Fluid reabsorption by the ductuli efferentes testis of the rat is dependent on both sodium and chlorine. Biol. Reprod.71, 410–416 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leung, G. P. H., Gong, X. D., Cheung, K. H., Cheng-Chew, S. B. & Wong, P. Y. D. Expression of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator in rat efferent duct epithelium. Biol. Reprod.64, 1509–1515 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ruz, R. et al. Expression of aquaporins in the efferent ductules, sperm counts, and sperm motility in estrogen receptor-a deficient mice fed lab chow versus casein. Mol. Reprod. Dev.73, 226–237 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhou, Q. et al. Estrogen action and male fertility: roles of the sodium/hydrogen exchanger-3 and fluid reabsorption in reproductive tract function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA98, 14132–14137 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rosenfeld, C. S. Male reproductive tract cilia beat to a different drummer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA116, 3361–3363 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yuan, S. et al. Mir-34B/C and Mir-449a/B/C are required for spermatogenesis, but not for the first cleavage division in mice. Biology Open, 1–12 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Yuan, S. et al. Motile cilia of the male reproductive system require miR-34/miR-449 for development and function to generate luminal turbulence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA116, 3584–3593 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Terré, B. et al. Defects in efferent duct multiciliogenesis underlie male infertility in GEMC1-, MCIDAS- or CCNO-deficient mice. Development (Cambridge)146 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Hoque, M., Chen, D., Hess, R. A., Li, F.-Q. & Takemaru, K.-I. CEP164 is essential for efferent duct multiciliogenesis and male fertility. Reproduction162, 129–139 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hoque, M., Kim, E. N., Chen, D., Li, F. Q. & Takemaru, K. I. Essential roles of efferent duct multicilia in male fertility. Cells11, 1–15 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aprea, I. et al. Motility of efferent duct cilia aids passage of sperm cells through the male reproductive system. Mol. Hum. Reprod.27, 1–15 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ilio, K. Y. & Hess, R. E. X. A. Structure and function of the ductuli efferentes. A Rev.467, 432–467 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jones, R. C. & Jurd, K. M. Structural differentiation and fluid reabsorption in the ductuli efferentes testis of the rat. Aust. J. Biol. Sci.40, 79–90 (1987). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leeson, T. S. Electron microscopy of the rete testis of the rat. Anat. Rec.144, 57–68 (1962). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dym, M. The mammalian rete testis-a morphological examination. Anat. Rec.172, 304 (1972). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bustos-Obregon, E. & Holstein, A. F. Cell and tissue research the rete testis in man: ultrastructural aspects. Cell Tiss. Res.175, 1–15 (1976). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wystub, T., Branscheid, W. & Paufler, S. Scanning electron and light microscopic studies of the surface epithelium of the rete testis and epididymis of the boar. I. Rete testis and efferent ducts. Dtw. Dtsch. Tierarztliche Wochenschr.96, 384–389 (1989). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leme Beu, C. C., Orsi, A. M., Stefanini, M. A. & Moreno, M. H. The ultrastructure of the guinea pig rete testis. J. Submicroscopic Cytol. Pathol.35, 141–146 (2003). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aire, T. A. Surface morphology of the ducts of the epididymal region of the drake (Anas platyrhynchos) as revealed by scanning and transmission electron microscopy. J. Anat.135 (1982). [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Girardet, L., Augière, C., Asselin, M. & Belleannée, C. Primary cilia: biosensors of the male reproductive tract. Andrology 12650 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Girardet, L. et al. Hedgehog signaling pathway regulates gene expression profile of epididymal principal cells through the primary cilium. no. February, pp. 1–17 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Bianchi, M. et al. Hedgehog signaling regulates Wolffian duct development through the primary cilium. Biology of Reproduction, 1–17 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Aire, T. A. & Soley, J. T. The surface features of the epithelial lining of the ducts of the epididymis of the ostrich Struthio camelus. Anat. Histol. Embryol. 8–15 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Tingari, M. D. The fine structure of the epithelial lining of the ex-current duct system of the testis of the domestic fowl (Gallus domesticus). Q. J. Exp. Physiol.57, 271–295 (1972). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bernet, A. et al. Cell-lineage Specif. Prim. cilia epididymis post-natal. Dev.33, 1829–1838 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hess, R. A. Small tubules, surprising discoveries: from efferent ductules in the turkey to the discovery that estrogen receptor alpha is essential for fertility in the male. Anim. Reprod.12, 7–23 (2015). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nigg, E. A. & Raff, J. W. Centrioles, centrosomes, and cilia in health and disease. Cell139, 663–678 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Goetz, S. C. & Anderson, K. V. The primary cilium: a signalling centre during vertebrate development. Nat. Rev. Genet.11, 331–44 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Anvarian, Z., Mykytyn, K., Mukhopadhyay, S., Pedersen, L. B. & Christensen, S. T. Cellular signalling by primary cilia in development, organ function and disease. Nat. Rev. Nephrol.15, 199–219 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fliegauf, M., Benzing, T. & Omran, H. When cilia go bad: cilia defects and ciliopathies. Nat. Rev. Mol. cell Biol.8, 880–93 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Choksi, S. P., Lauter, G., Swoboda, P. & Roy, S. Switching on cilia: transcriptional networks regulating ciliogenesis. Development141, 1427–1441 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wachten, D. & Mill, P. Europe PMC Funders Group Polycystic kidney disease: The cilia mechanosensation debate gets (bio) physical. 19, 279–280 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 45.Katoh, T. A. et al. Immotile cilia mechanically sense the direction of fluid flow for left-right determination. Science379, 66–71 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Djenoune, L. et al. Cilia function as calcium-mediated mechanosensors that instruct left-right asymmetry. Science379, 71–78 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hunter, M. I., Thies, K. M. & Winuthayanon, W. Hormonal regulation of cilia in the female reproductive tract. Curr. Opin. Endocr. Metab. Res.34, 100503 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hagiwara, H., Ohwada, N. & Aoki, T. The primary cilia of secretory cells in the human oviduct mucosa. 193–198 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 49.Mirzadeh, Z. et al. Bi-and uniciliated ependymal cells define continuous floor-plate-derived tanycytic territories. Nat. Commun. (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 50.Mirzadeh, Z., Merkle, F. T., Soriano-Navarro, M., Garcia-Verdugo, J. M. & Alvarez-Buylla, A. Neural stem cells confer unique pinwheel architecture to the ventricular surface in neurogenic regions of the adult brain. Cell Stem Cell3, 265–278 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Eichele, G. et al. Cilia-driven flows in the brain third ventricle. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B375, (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 52.Monaco, S. et al. A flow cytometry-based approach for the isolation and characterization of neural stem cell primary cilia. Front. Cell. Neurosci.12, 1–13 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang, X. et al. SNX27 deletion causes hydrocephalus by impairing ependymal cell differentiation and ciliogenesis. J. Neurosci.36, 12586–12597 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Danielian, P. S., Hess, R. A. & Lees, J. A. E2f4 and E2f5 are essential for the development of the male reproductive system. Cell Cycle15, 250–260 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hess, R. A. Disruption of estrogen receptor signaling and similar pathways in the efferent ductules and initial segment of the epididymis. Spermatogenesis, 5562 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 56.Jain, R. et al. Temporal relationship between primary and motile ciliogenesis in airway epithelial cells. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol.43, 731–739 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Delling, M., Decaen, P. G., Doerner, J. F., Febvay, S. & Clapham, D. E. Primary cilia are specialized calcium signalling organelles. Nature504, 311–314 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bangs, F. K., Schrode, N., Hadjantonakis, A. & Anderson, K. V. Lineage specificity of primary cilia in the mouse embryo. 17, (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 59.Li, X., Yang, S., Deepk, V., Chinipardaz, Z. & Yang, S. Identification of cilia in different mouse tissues. Cells10, 1–15 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sun, Z. et al. A genetic screen in zebrafish indentifies cilia genes as a principal cause of cystic kidney. Development131, 4085–4093 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]