Abstract

The identification of several simian immunodeficiency virus mac251 (SIVmac251) cytotoxic T-lymphocyte epitopes recognized by CD8+ T cells of infected rhesus macaques carrying the Mamu-A*01 molecule and the use of peptide-major histocompatibility complex tetrameric complexes enable the study of the frequency, breadth, functionality, and distribution of virus-specific CD8+ T cells in the body. To begin to address these issues, we have performed a pilot study to measure the virus-specific CD8+ and CD4+ T-cell response in the blood, lymph nodes, spleen, and gastrointestinal lymphoid tissues of eight Mamu-A*01-positive macaques, six of those infected with SIVmac251 and two infected with the pathogenic simian-human immunodeficiency virus KU2. We focused on the analysis of the response to peptide p11C, C-M (Gag 181), since it was predominant in most tissues of all macaques. Five macaques restricted viral replication effectively, whereas the remaining three failed to control viremia and experienced a progressive loss of CD4+ T cells. The frequency of the Gag 181 (p11C, C→M) immunodominant response varied among different tissues of the same animal and in the same tissues from different animals. We found that the functionality of this virus-specific CD8+ T-cell population could not be assumed based on the ability to specifically bind to the Gag 181 tetramer, particularly in the mucosal tissues of some of the macaques infected by SIVmac251 that were progressing to disease. Overall, the functionality of CD8+ tetramer-binding T cells in tissues assessed by either measurement of cytolytic activity or the ability of these cells to produce gamma interferon or tumor necrosis factor alpha was low and was even lower in the mucosal tissue than in blood or spleen of some SIVmac251-infected animals that failed to control viremia. The data obtained in this pilot study lead to the hypothesis that disease progression may be associated with loss of virus-specific CD8+ T-cell function.

A central goal in studies of the pathogenesis of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) type 1 infection is the understanding of the immunological alterations that allow the development of AIDS. Mounting evidence indicates that cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) are of major importance in the control of acute and chronic HIV infection (8, 19, 28, 29, 31, 32, 35), as they are in simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) infection of macaques (17, 24, 37). Thus, it is reasonable to hypothesize that the development of AIDS is ultimately caused by a failure of CTLs to contain viral replication.

At least two factors can be the cause of such failure. First, CTLs can be ineffective because of viral escape (emergence of resistant strains) (6, 10, 14, 20, 33, 34, 44). Second, when viral replication is not fully contained by CTLs there may be a progressive loss of CD4+ T cells (36), which then may become significant enough to impair CD4+ T-cell help for the ongoing CTL responses. The CD4+ T-cell loss and impairment of CD8+ T-cell CTL response then form a feedback loop that leads to steadily increasing viral load and disease progression. Evidence for this concept comes from recent studies of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus infection in which it was shown that CD4+ T-cell deficiency is correlated with the presence of specific CD8+ T cells lacking effector function (46), i.e., cells unable to kill appropriate target cells and/or release antiviral cytokines such as gamma interferon (IFN-γ) (7, 23, 46). Decreased levels of IFN-γ production, cytolytic activity, and perforin production have also been demonstrated in HIV type 1-infected individuals in a number of studies (3, 12, 21, 40, 41), although not all studies support this observation (13).

In the present study we have begun to address the question of the distribution of antigen-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in various body compartments and their competence in relation to CD4+ T-cell deficiency in the context of SIV infection of rhesus macaques, taking advantage of the fact that, while Mamu-A*01-positive macaques, as a group, contain viremia following intrarectal challenge with SIVmac251 (561) (R. Pal et al., submitted for publication), some individual animals fail to do so. This allowed us to compare the size and function of the virus-specific CD8+ T-cell and the CD4+ T-cell helper response in individual Mamu-A*01-positive macaques that could contain viral replication with those of macaques that could not.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Macaques and viral infection.

Six of the macaques studied here were infected with the SIV251 (561) stock virus. Briefly, the viral stock was prepared by culturing phytohemagglutinin-activated peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) from an infected macaque (561L) that was inoculated vaginally with SIVmac251. The titer of SIV challenge stock was determined in vivo in rhesus macaques by inoculating six rhesus macaques with different dilutions of virus stock via the rectal route. Since six out of six animals inoculated with virus stock (0.5 ml diluted in 1.5 ml of RPMI medium) were infected, as evidenced by high viremia in plasma and a drop in CD4 counts, this dose of virus was used for challenge studies by the intrarectal route. This viral stock is pathogenic and in our experience induces disease in approximately 20% of the macaques within the first year from infection (Pal et al., submitted). Macaque 3070 was completely naive at the time of viral exposure and was the only animal infected by the intravenous route with a 1:3,000 dilution of the SIV251 (561) stock. The remaining macaques (macaques 444, 459, 575, 408, and 427) were all mock vaccinated or naive macaques from a vaccine study (Pal et al., submitted) and were exposed to the same undiluted SIV251 (561) stock by the intrarectal route. Animal 432, whose blood was used to standardize the concentration of peptide necessary for optimal stimulation, was part of the same study (Pal et al., submitted). Macaques 376 and 389 were inoculated with undiluted simian-human immunodeficiency virus KU2 (SHIVKU2) (18) by the intrarectal route.

Preparation of lymphocytes from blood and tissues.

Lymphocytes from blood, spleen, and lymph nodes were isolated by density-gradient centrifugation on Ficoll and resuspended in RPMI 1640 medium (GIBCO BRL, Gaithersburg, Md.) containing 5% inactivated human A/B serum (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.). Gastrointestinal lymphoid tissue (GALT) lymphocytes were obtained from intestinal tissues after necropsy. The tissue sections (roughly 50 cm2) were washed several times in HBSS medium (GIBCO BRL, Grand Island, N.Y.) with antibiotics, and the intestinal mucosa was mechanically removed from the muscular layer of intestine with iris scissors. The mucosal sections were washed with HBSS medium containing dithiothreitol (1.5 mg/ml; ICN Biomedicals, Aurora, Ohio) for 30 min while shaking, rinsed two times in HBSS, and treated for 1 h three times at room temperature with 1 mM EDTA (Biofluids, Rockville, Md.), Ca2+/Mg2+-free HBSS, and antibiotics with stirring to remove epithelial cells. The remaining tissue sections were then cut into small pieces and incubated with collagenase D (400 U/ml; Boehringer Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany) and DNase (1 μg/ml; Worthington Biochemical Corporation, Lakewood, N.J.) for 90 min at 37°C with Iscove's medium (GIBCO BRL) containing 10% FBS and antibiotics. The dissociated mononuclear cells were than placed over 45% Percoll (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Uppsala, Sweden) and centrifuged at 800 × g for 20 min at 4°C. GALT lymphocytes were collected from the cell pellet.

Lymphocyte proliferation assay.

Antigen-specific proliferation was measured using freshly prepared cells. Lymphocytes were resuspended in RPMI 1640 medium (GIBCO BRL) containing 5% inactivated human A/B serum (Sigma) and cultured at 105 cells/well for 3 days in 96-well plates in the absence or presence of native purified SIV p27 Gag or gp120 proteins (ABL, Inc., Rockville, Md.) or concanavalin A as a positive control. The cells were then pulsed overnight with 1 μCi of [3H]thymidine prior to harvest. The relative rate of lymphoproliferation was calculated as fold thymidine incorporation into cellular DNA over control (stimulation index [SI]). The assay was considered positive when the SI was greater than 3.

Detection of epitope-specific CD3+ CD8+ T lymphocytes by flow cytometry.

Freshly prepared cells were stained with anti-human CD3 antibody (Ab) (PerCP labeled; clone SP34; PharMingen, San Diego, Calif.), anti-human CD8α Ab (fluorescein isothiocyanate labeled; Becton Dickinson, San Diego, Calif.), and Mamu-A*01 tetrameric complexes refolded in the presence of a specific peptide (J. Altman, Emory University Vaccine Center at Yerkes) and conjugated to phycoerythrin-labeled streptavidin (Molecular Probes, Eugene, Oreg.). Samples were analyzed on a FACSCalibur (Becton Dickinson), and the data are presented as percentages of tetramer-positive cells of all CD3+ CD8+ cells. Data were obtained from no fewer than 40,000 lymphocytes in each case. To detect epitope-specific CD8+ lymphocytes expanded in vitro by the specific peptides, a total of 3 × 106 cells in 1 ml of medium were incubated at a final concentration of 10 μg/ml of peptide for 3 days. Recombinant interleukin-2 (Boehringer Mannheim, Indianapolis, Ind.) was added at 20 IU/ml, and the cells were cultured for an additional 4 days and stained as described for fresh PBMC.

ELISPOT assay.

Macaque IFN-γ-specific enzyme-linked immunospot (ELISPOT) kits manufactured by U-Cytech (Utrecht, Netherlands) were used in order to detect the number of IFN-γ-producing cells. Ninety-six-well flat-bottom plates were coated with anti-IFN-γ monoclonal Ab MD-1 overnight at 4°C and blocked with 2% bovine serum albumin in phosphate-buffered saline for 1 to 3 h at 37°C. Cells (105 per well) were loaded in sextuplicate in RPMI 1640 containing 5% human serum and a specific peptide (1 μg/ml) or concanavalin A (5 μg/ml) as a positive control. The plates were incubated overnight at 37°C with 5% CO2 and developed according to the manufacturer's guidelines (U-Cytech). In cases where intracellular IFN-γ production was measured in the presence of feeder cells, 105 CD8-depleted splenocytes were added to the cells to be examined in each well. CD8+ cells were removed from Ficoll-purified splenocytes using α-CD8 Ab-coated beads (Dynal, Oslo, Norway) and contained less than 0.3% of residual CD3+ CD8+ cells. In this assay, results were considered positive at more than 25 spot-forming cells (SFC)/106 cells, based on background levels obtained with cells from Mamu-A*01-negative animals using Mamu-A*01-restricted CTL epitopes or cells stimulated with irrelevant peptides.

Intracellular staining for IFN-γ .

Cells (2 × 106) were mixed in a 1:1 ratio with feeder cells (CD8-depleted splenocytes containing less than 0.3% CD3+ CD8+ cells) in RPMI 1640 medium containing antibiotics and 10% human serum and incubated in the presence or absence of a specific peptide at 1 μg/ml for 1 h. GolgiStop (1 μl; PharMingen) was added, and the cells were incubated for an additional 5 h. The cells were washed, stained for surface antigenic markers CD3ɛ and CD8 (BD PharMingen) and specific tetramer, and fixed and permeabilized using the Cytofix/Cytoperm kit (BD PharMingen). Permeabilized cells were stained with fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled anti-IFN-γ Ab (clone 4S.B3; PharMingen) and analyzed on a FACSCalibur (Becton Dickinson) by four-color flow-cytometry analysis.

Intracellular staining for TNF-α .

A total of 106 cells in RPMI 1640 medium containing antibiotics and 10% human serum were incubated in the presence or absence of a specific peptide at an indicated concentration for 1 h. As a positive control, cells were treated with phorbol myristate acetate (25 ng/ml; Sigma) and ionomycin (1 μg/ml; Sigma) for 6 h. Brefeldin A (Sigma) at a final concentration of 10 μg/ml was added, and the cells were incubated for an additional 5 h. The cells were washed, stained for surface antigens CD3ɛ and CD8 (BD PharMingen), permeabilized using FACSPerm (BD PharMingen) according to the manufacturer's protocol, and stained with anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha (anti-TNF-α) Ab (BD PharMingen). The cells were analyzed on a four-color flow cytometer (FACSCalibur; Becton Dickinson).

CTL assay.

Fresh PBMC were cultured overnight in the presence of interleukin-2 (100 IU/ml) and then incubated in different effector-to-target cell ratios for 6 h with Mamu-A*01-positive 51Cr-labeled autologous transformed B cells pulsed overnight with 1 μg of a specific peptide per ml. The killing of cells pulsed with an unrelated peptide in a control experiment was equal to the killing observed in the absence of any peptide.

RESULTS

Frequency of virus-specific tetramer-staining CD8+ T cells in blood and tissues obtained from Mamu-A*01-positive infected macaques with differing capacities to contain viral replication.

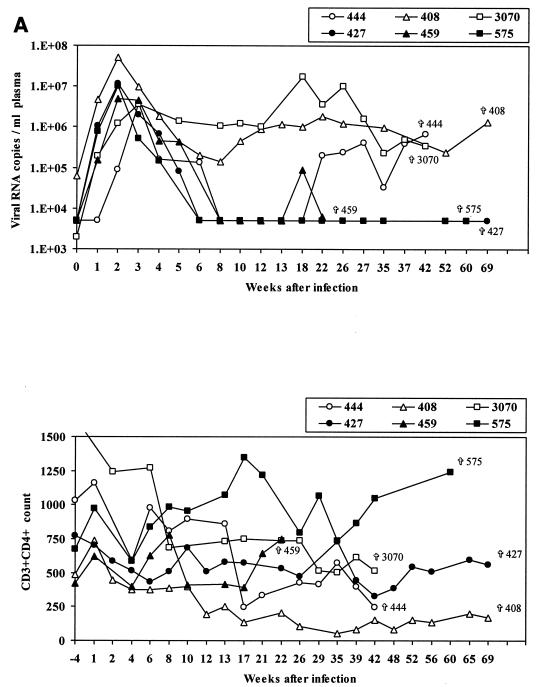

While Mamu-A*01-positive macaques as a group manifested better containment of SIVmac251 (561) infection than Mamu-A*01-negative macaques (Pal et al., submitted), some individual Mamu-A*01-positive animals exhibited poor containment of infection, as indicated by the occurrence of viremia in plasma (Fig. 1A, upper panel) and CD4 loss (Fig. 1A, lower panel). To begin to investigate the basis of this variability, we assessed virus-specific CD8+ T-cell responses in six Mamu-A*01-positive macaques infected with SIVmac251 that either controlled viremia (animals 459, 427, and 575) or not (animals 444, 408, and 3070) and two Mamu-A*01-positive macaques infected with SHIVKU2 that controlled viremia but differed in CD4+ T-cell numbers (Fig. 1B). The level of viremia and CD4+ T-cell count over time in the macaques studied are shown in Fig. 1 and include animals 408, 444, and 3070, which failed to control plasma viremia and were sacrificed for the purpose of this study at 481, 295, and 300 days after infection, respectively, and animals 427, 575, and 459, which naturally restricted plasma viremia by week 8 postinfection and thereafter (macaque 459 experienced a transient rebound of viremia at day 134) and were sacrificed at 482, 424, and 153 days after infection, respectively. Animals 376 and 389 were both sacrificed 198 days after intrarectal challenge with SHIVKU2.

FIG. 1.

Viral load and CD4+ T-cell count in rhesus macaques included in the study. Upper panels show the number of viral RNA copies per milliliter of plasma as analyzed by NASBA. Lower panels show the absolute number of CD3+ CD4+ T cells per microliter of blood. (A) SIVmac251; (B) SHIVKU2.

The frequency of the Gag peptide p11C, C-M (Gag 181 in this report) tetramer-positive CD8+ T cells in the blood of these animals at weeks 4, 8, and 12 following SIVmac251 or SHIVKU2 exposure is summarized in Table 1. Gag 181-tetramer-staining CD8+ T cells with a frequency that ranged from 0.5 to 11% were observed, and the two animals with the highest level of tetramer-positive cells were the ones that controlled viremia. However, the small number of animals did not allow a clear correlation with the ability of the individual animals to restrict viremia and the frequency of this Gag 181-specific response, as exemplified by the similarity in the frequency of this response between animals 3070 and 575, which differed in their ability to control viremia.

TABLE 1.

Quantitation of frequency of Gag 181-tetramer-positive CD3+CD8+ T cells in the blood of Mamu-A∗01-positive macaques

| Infection and macaque no. | Virological outcome | % Gag 181-tetramer-positive CD8+ T cells at wk:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | 7 or 8 | 10 or 12 | ||

| SIVmac251 | ||||

| 444 | No viremia control | 0.5 | 1.4 | 1.4 |

| 3070 | No viremia control | 0.61 | 3.76 | 2.72 |

| 408 | No viremia control | NDa | ND | ND |

| 427 | Control of viremia | ND | ND | ND |

| 459 | Control of viremia | 11 | 9.8 | 5.5 |

| 575 | Control of viremia | 2.7 | 3 | 3.9 |

| SHIVKU2 | ||||

| 376 | Control of viremia | 9.1 | 2.7 | 2.3 |

| 389 | Control of viremia | 1.24 | 0.8 | 0.63 |

ND, not done.

Although some studies have addressed the SIV-specific immune response in tissues other than blood (11, 22, 25–27, 38, 39), few studies have assessed together the size and functionality of epitope-specific CD8+ T-cell responses in tissues of infected macaques since the tetramer technology has become only recently available (2).

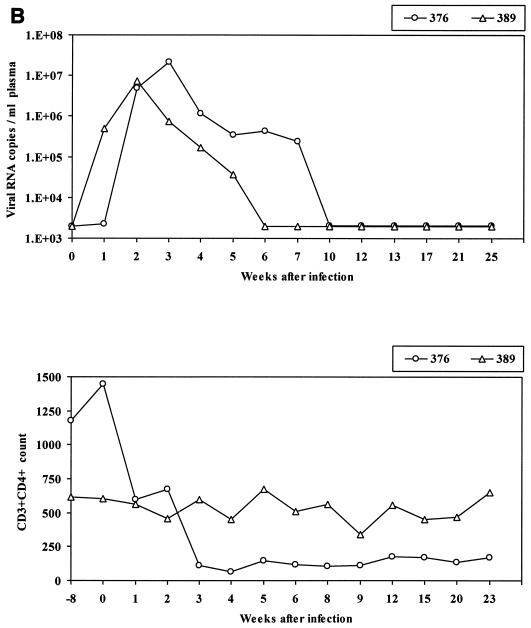

Lymphocytes were obtained from the blood, superficial and internal lymph nodes, spleen, and mucosal tissues (jejunum, colon, and ileum) at the time of sacrifice and used in a variety of assays, most of them performed simultaneously, to assess whether the virus-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell response in tissues could explain the virological outcome. At the time of euthanasia, analysis of Gag- and Tat-specific responses using the Gag 181 and Tat 28 tetramers in SIVmac251-infected macaques (1) demonstrated high variability in the frequency of these virus-specific CD8+ T-cell responses in the macaque tissues, and no clear pattern with regard to numbers of tetramer-positive cells in tissues and virological outcome could be discerned. As demonstrated in the case of the response to the immunodominant Gag 181 (Fig. 2A), while two of the macaques (macaques 459 and 427) that controlled viral replication manifested higher frequencies of Gag 181-tetramer-positive CD8+ T cells in the spleen and colon than in the blood, this was also true for one of three macaques that failed to control infection. Similar results were obtained with the Tat 28-tetramer-positive T cells in the case of macaques 575 and 459 (Fig. 2B). The antigen specificity of the tetramer-positive CD8+ T-cell population measured in tissues of SIVmac251-infected macaques was further confirmed by expanding the cells in vitro with the appropriate peptide (data not shown). In the case of both of the SHIVKU2-infected macaques, the size of Gag 181-tetramer-positive CD8+ cells was also higher in the tissues than in the blood (Table 2).

FIG. 2.

Quantitation of virus-specific CD8+ T cells in tissues. The percentages of Gag 181 (A)- and Tat 28 (B)-tetramer-staining cells out of total CD3+ CD8+ T-cell population obtained at euthanasia are presented. Asterisks indicate measurements that were not performed.

TABLE 2.

Relative capacity of CD3+ CD8+ Gag 181-tetramer-staining cells to produce intracellular cytokines upon in vitro stimulation with peptide Gag 181

| Macaque no. | Compartment | % CD3+ CD8+ Gag 181-tetramer-positive cells | CD3+ CD8+ cytokine-producing cellsa

|

% Increasea | Ratio of CD3+ CD8+ cytokine-producing cells to Gag 181-tetramer-positive cells | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No stimulation | Stimulated with Gag 181 | |||||

| 444 | Spleen | 2.2 | 0.07 | 0.3 | 0.23 | 0.1 |

| Mesenteric lymph node | 1.4 | 0.03 | 0.2 | 0.17 | 0.12 | |

| Colon | 1.2 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0 | 0 | |

| Ileum | 1.2 | 0.02 | 0.08 | 0.06 | 0.05 | |

| 3070 | PBMC | 0.4 | 2.45 | 2.58 | 0.13 | 0.32 |

| Spleen | 0.7 | 0.88 | 0.86 | −0.02 | 0 | |

| Colon | 0.3 | 0.52 | 0.58 | 0.06 | 0.2 | |

| Jejunum | 0.3 | 0.19 | 0.2 | 0.01 | 0.03 | |

| 376 | PBMC | 1.1 | 0.5 | 1.2 | 0.7 | 0.64 |

| Spleen | 3 | 0.5 | 2.7 | 2.2 | 0.73 | |

| Colon | 4.5 | 0.7 | 3.1 | 2.4 | 0.53 | |

| Jejunum | 5.3 | 0.2 | 3.4 | 3.2 | 0.6 | |

| 389 | PBMC | 0.2 | 0.15 | 0.5 | 0.35 | 1.75 |

| Spleen | 1.2 | 0.6 | 1 | 0.4 | 0.3 | |

| Colon | 1.9 | 1.8 | 2.6 | 0.8 | 0.42 | |

| Jejunum | 1.9 | 1.3 | 1.8 | 0.5 | 0.26 | |

Cells obtained from animal 444 were incubated in the presence or absence of peptide Gag 181 (1 μg/ml) and assayed for intracellular IFN-γ production (Fig. 6A). Cells obtained from animals 3070, 376, and 389 were incubated in the presence or absence of peptide Gag 181 (10 μg/ml) and assayed for intracellular TNF-α production (Fig. 6B to D).

Taken together, these data suggest that the frequency of Gag 181-tetramer-positive CD8+ T cells varies within tissues of the same animal and among animals and that their numbers do not correlate consistently with systemic control of infection.

The capacity of Gag 181-tetramer-positive CD8+ T cells obtained from systemic (nonmucosal) and mucosal tissues to produce IFN-γ and to manifest CTL activity.

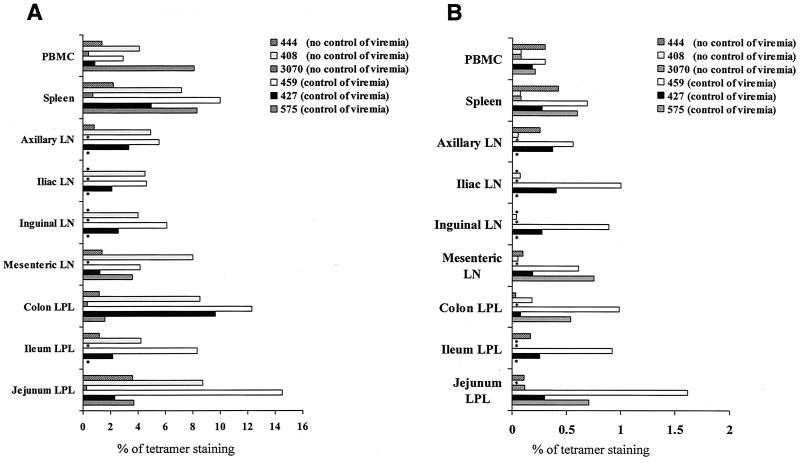

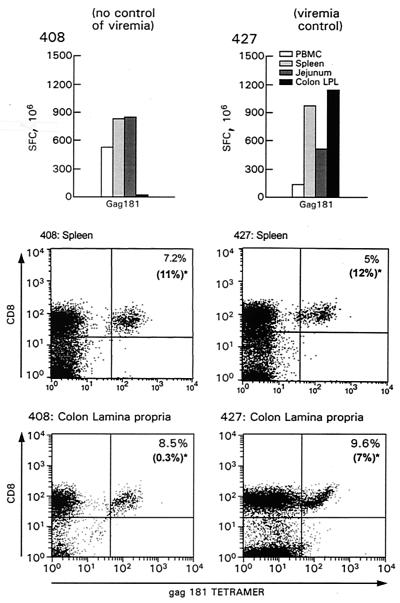

Having evaluated the presence of virus-specific CD8+ T cells recognizing several major histocompatibility complex class I-restricted SIV epitopes by tetramer staining, we turned our attention to the functional capacity of cells in both systemic and mucosal lymphoid compartments. In the first of these studies, we determined the ability of T cells obtained from systemic tissues (blood and spleen) stimulated in vitro with Mamu-A*01-restricted SIVmac251-specific peptides to produce IFN-γ after overnight incubation, i.e., conditions under which the relative frequency of T cells secreting IFN-γ can be measured. We elected to focus on the response to Gag 181 because it was the predominant response in all animals. As shown in Fig. 3, although macaques 408 and 427 differed in their ability to restrict viral replication, both had equivalent Gag 181-specific ELISPOT responses in the blood, spleen, and mesenteric lymph nodes. Of interest, however, despite the fact that these macaques had comparable numbers (8.5 and 9.6%, respectively) of CD3+ CD8+ Gag 181-tetramer-positive T cells in the lamina propria of the colon (lower panel of Fig. 3), only cells from the lamina propria of animal 427, which controlled viremia, were able to produce IFN-γ following Gag 181 peptide stimulation as assessed by ELISPOT assay (top panel, Fig. 3), raising the possibility that Gag 181-specific CD8+ T cells may differ in their functionality in mucosal compartments. In fact, the ratio between the total number of Gag 181-tetramer-positive cells and the relative number of CD3+ CD8+ cells producing IFN-γ in the various tissue compartments indicated that only a fraction of these cells were able to produce IFN-γ (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Enumeration of CD8+ T cells producing IFN-γ in tissues of animals 408 and 427 and the frequency of Gag 181-tetramer-positive cells in the spleen and colon lamina propria. The histograms show results (SFC per 106 PBMC) of IFN-γ ELISPOT assays performed ex vivo with fresh cells from PBMC, spleen, mesenteric lymph nodes, and colon lamina propria of animals 408 and 427. The bottom panels show percentages of CD3+ CD8+ Gag 181-tetramer-positive cells in the spleen and colon lamina propria of animals 408 and 427 at time of sacrifice. The cells were first gated for CD3+ lymphocyte population. The data in parentheses in each panel represent the relative percentages of CD3+ CD8+ tetramer-positive T cells producing IFN-γ.

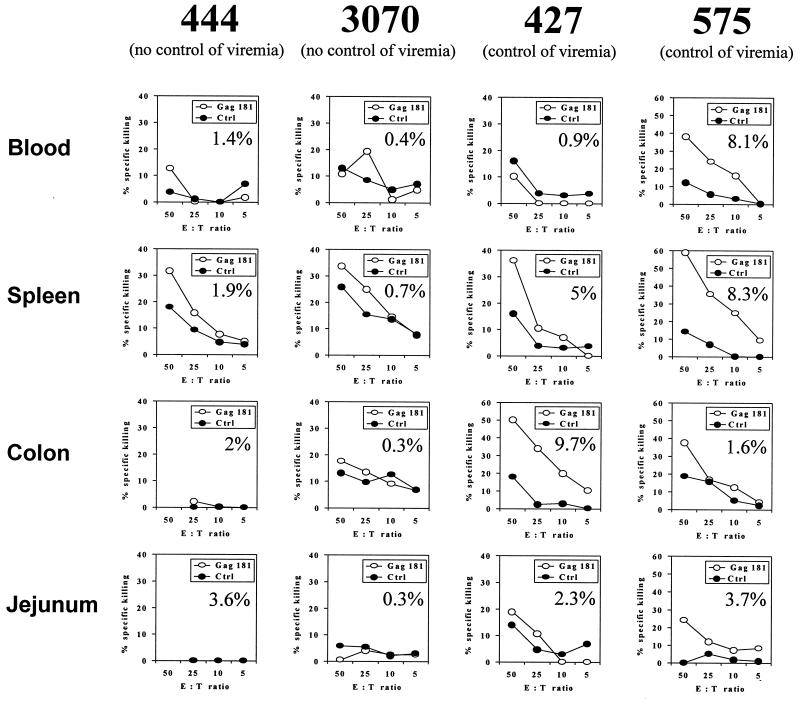

As a further assessment of Gag-specific CD8+ T-cell function, ex vivo CTL activity was measured in the blood and spleen of animals 427 and 575, which were able to restrict viral replication, and macaques 444 and 3070, which did not (insufficient numbers of cells were available from animals 408 and 459). As shown in Fig. 4, ex vivo cytolytic activity at or more than 10% above the background was observed only in the blood and/or spleen of macaques 575, 427, and 444. Of interest, however, ex vivo CTL activity was observed in the lamina propria of mucosal tissue of animals 427 and 575 but not animals 444 or 3070 even when an equivalent frequency of Gag 181-tetramer-positive cells was found in those tissues (for example, in the jejunum of animal 444 versus animal 575) (see percentage of Gag 181-tetramer-positive cells within each panel of Fig. 4). These data further supported the notion that the frequency of Gag 181-tetramer-positive cells did not necessarily correlate with their functionality. However, the highest cytolytic activity was found in the 3 cases of tetramer-positive cells in the range of 8 to 10%.

FIG. 4.

Ex vivo cytolytic activity of lymphocytes freshly isolated from blood, spleen, and GALT. The percentages of killing of Gag 181-pulsed B cells (○) or control B cells (●) are indicated. The percentage of Gag 181-tetramer-positive cells out of the total CD3+ CD8+ T-cell population is shown in each panel.

Direct assessment of the ability of Gag 181-tetramer-staining CD3+ CD8+ T cells to produce cytokines in macaques that failed to control viremia.

To more directly assess the functional activity of the Gag 181-tetramer-positive T cells we measured their ability to produce either TNF-α or IFN-γ upon in vitro stimulation with a specific peptide.

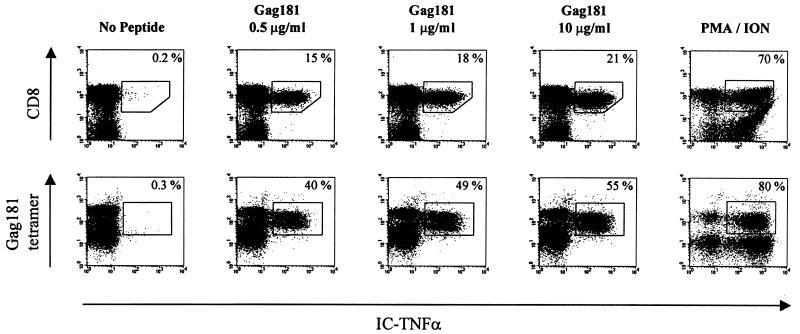

Because the ability of Gag 181-tetramer-positive T cells to produce cytokines may be dependent on the condition of in vitro peptide stimulation, we first optimized the concentration of peptide using cells from a Mamu-A*01-positive infected macaque (animal 432) that maintained a high frequency of Gag 181-tetramer-positive T cells in the blood (35 to 36%) and controlled viremia (J. Nacsa et al., unpublished data). As demonstrated in Fig. 5, approximately half (49%) of Gag 181-tetramer-positive CD3+ CD8+ T cells produced TNF-α with Gag 181 peptide (1 μg/ml) and a 10-fold increase in Gag 181 concentration increased the number of T cells producing TNF-α only an additional 6% (to 55%), suggesting that even in the presence of a high excess of antigen, only a fraction of the cells were able to produce TNF-α in the blood of this chronically infected macaque. Nevertheless, the concentration 10 μg/ml of Gag 181 peptide was chosen for further analysis of the ability of CD3+ CD8+ Gag 181-tetramer-positive T cells to produce TNF-α following peptide stimulation.

FIG. 5.

Intracellular TNF-α production at increasing concentration of Gag 181 peptide. (Top row) Intracellular TNF-α production in CD3+ CD8+ T cells following 6-h stimulation with the indicated concentrations of Gag 181 peptide. The lymphocytes isolated from blood of control animal 432 were assayed as described in Materials and Methods. The cells were first gated for CD3+ lymphocyte population. The number in the top right corner indicates the percentage of TNF-α-positive cells out of the total CD3+ CD8+ cells. (Bottom row) Intracellular TNF-α production in Gag 181-tetramer-positive CD3+ CD8+ T cells at increasing concentration of Gag 181 peptide. The number in the top right corner indicates the percentage of TNF-α-positive cells out of the Gag 181-tetramer-positive CD3+ CD8+ T cells. PMA/ION, positive control (cells were treated with phorbol myristate acetate and ionomycin).

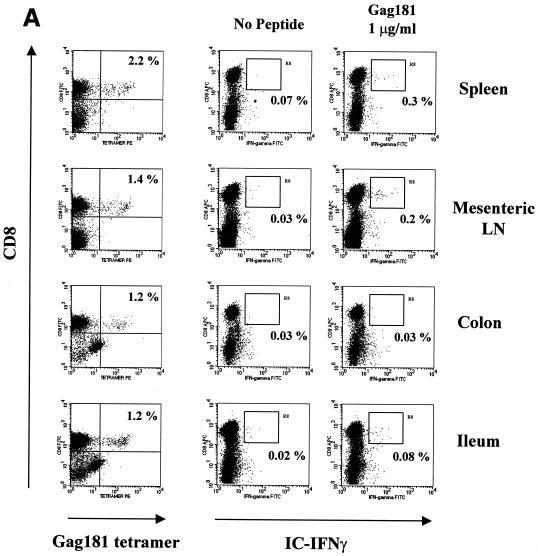

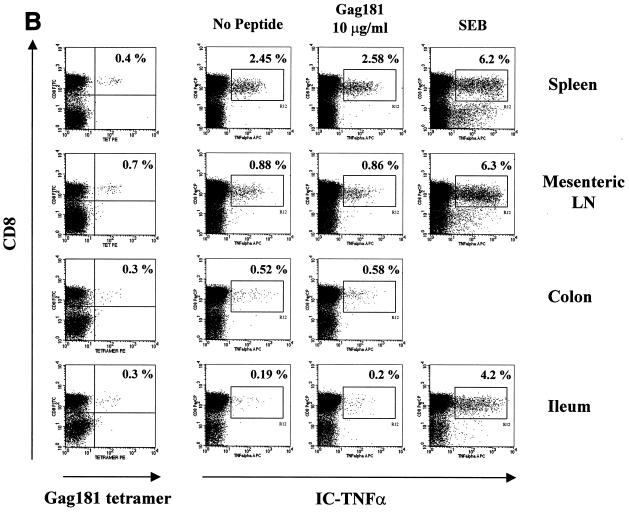

In the case of macaque 3070, only a few of the Gag 181-tetramer-positive T cells in the tissues were able to produce TNF-α following Gag 181-peptide stimulation (Fig. 6B). These data paralleled the absence of Gag 181-specific cytolytic activity in these compartments of animal 3070, as demonstrated in Fig. 4.

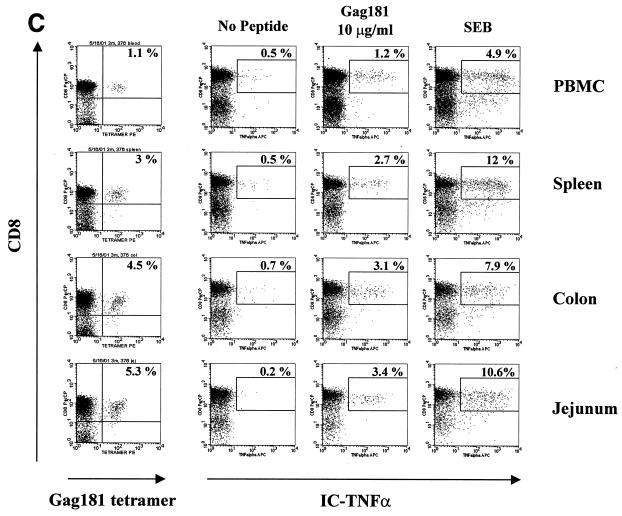

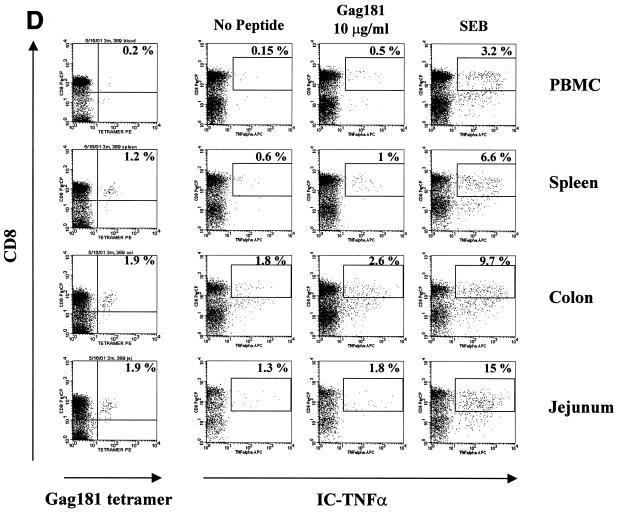

FIG. 6.

Gag 181-tetramer staining and intracellular cytokine production in lymphocytes obtained from systemic and mucosal tissues of macaques. (A) Animal 444 (no control of viremia); (B) animal 3070 (no control of viremia); (C) animal 376 (control of viremia); (D) animal 389 (control of viremia). The leftmost column of panels show the percentage of CD3+ CD8+ cells staining with Gag181 tetramer. Panels in the middle and at right show cells that were incubated in the absence of any stimulation, in the presence of peptide Gag181 (at 1 μg/ml [animal 444] or 10 μg/ml [animals 3070, 376, and 389]) or in the presence of Staphylococcus enterotoxin B (SEB; 1 μg/ml) for 6 h as indicated and assayed for intracellular production of IFN-γ (animal 444) or TNF-α (animals 3070, 376, and 389). The numbers represent the percentages of cytokine-positive cells of total CD3+ CD8+ population. A total of more than 10,000 (animal 444), 20,000 (animal 3070), or 5,000 (animals 376 and 389) cell events in the lymphocyte gate were analyzed for each condition. All cell events shown here were at first gated for CD3+ lymphocyte marker.

In the case of animal 444, intracellular IFN-γ production was used as a readout. Again, the percentage of the virus-specific Gag 181-tetramer-positive CD8+ T-cell population producing IFN-γ was low in most compartments (Fig. 6A). Also, in this case, the decreased ability of these cells to produce IFN-γ went along with the inability of colon and jejunum CD8+ T cells to express cytolytic activity (Fig. 4).

A similar analysis, using TNF-α as a readout, was performed with the two macaques infected with SHIVKU2 that controlled viremia effectively. As indicated in Fig. 6C and D, a discrete population of Gag 181-tetramer-staining cells was found in blood and several tissues from both macaques and again the size of the virus-specific CD8+ T-cell population was larger in the GALT than in the blood. In all tissues of macaques 376 and 389, Gag 181-specific stimulation increased the ability of cells with this specificity to produce TNF-α (Table 2).

One caveat in the interpretation of the above-mentioned results on direct staining of the tetramer-positive cells for IFN-γ or TNF-α production is that the estimate of the number of tetramer-positive cells producing these cytokines may be artificially low because of downregulation of cell surface markers following antigen-specific stimulation and Ab or tetramer staining, as suggested by others (3). Nevertheless, using both TNF-α and IFN-γ as a readout, the picture that emerged is that the function of the Gag 181-specific CD8+ T cells in the tissues of chronically infected animals could not be assumed based only on the ability to bind the Gag 181 tetramer, especially in the gut lymphoid tissue.

Viremia level and preservation of CD4+ T-cell levels in mucosal tissues of SIVmac251-infected macaques.

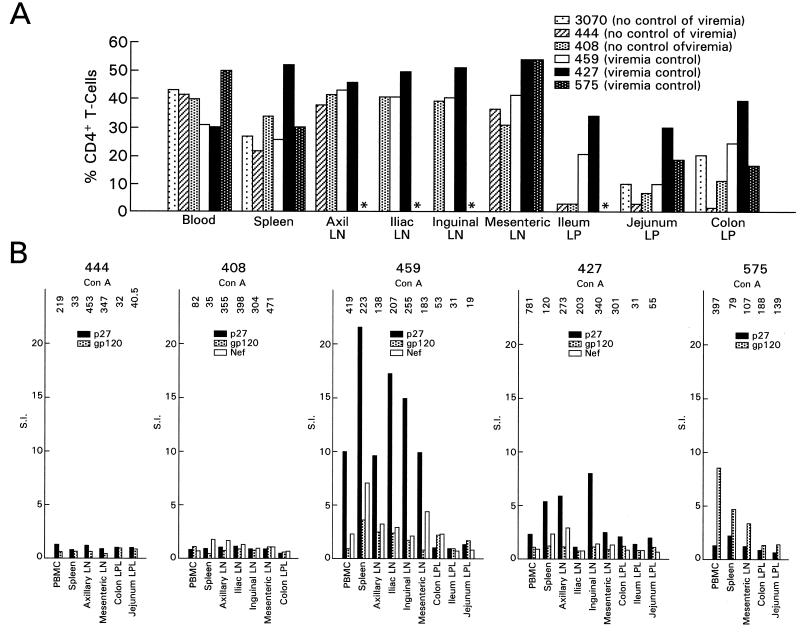

One possible explanation for the persistence of CTL functional activity of Gag 181-tetramer-positive CD8+ T cells in the mucosal tissues of SIVmac251-infected macaques that controlled viremia (such as in animals 427, 459, and 575) could be that in such animals sufficient levels of CD4+ T-cell function were preserved to support persistent CD8+ T-cell function. To investigate this hypothesis, CD4+ T-cell levels and proliferative responses were measured in the tissues of these macaques. As shown in Fig. 7A, CD4+ T cells were more depleted in mucosal tissues than in blood or spleen of animals 408, 444, and 3070, the macaques that failed to control viremia, and this difference was less evident in mucosal tissues of macaques 427, 575, and 459, the macaques that contained viremia.

FIG. 7.

Relative percentage of CD4+ T cells and proliferative response in systemic tissues and GALT. (A) The relative percentage of CD4+ T cells of total CD3+ lymphocytes in each tissue was measured in the cell suspension obtained after tissue processing, as indicated in Materials and Methods. (B) Lymphocyte proliferation assay using SIV p27 Gag, gp120 Env, and Nef antigens. The value of [3H]thymidine incorporation over the medium is expressed as the SI. Values of >3 are considered positive. The number on the top of each histogram represents the SI obtained using concanavalin A as a positive control.

Finally, measurement of antigen-specific Gag, Env, and Nef CD4+ T-cell responses in various compartments demonstrated the presence of proliferative responses with stimulation indices greater than 3 in tissues from macaques 427, 459, and 575 but not from macaques 408 and 444 (Fig. 7B). The fact that proliferative responses were not measured in the mucosal tissues of all animals was expected since lamina propria lymphocytes are known to survive poorly in culture (5). Overall, then, the decrease in the percentage of CD4+ T cells in the mucosal tissues and the decrease in systemic CD4+ T-cell responses appeared to be associated with a higher level of viremia.

DISCUSSION

In this study we obtained evidence, within the limitation of the small number of macaques studied, that control of viral replication and preservation of CD4+ T cells following SIVmac251 (561) infection of Mamu-A*01-positive macaques was not necessarily associated with the size of virus-specific CD8+ T-cell responses (tetramer-positive T-cell responses) directed to the viral Gag protein in various systemic lymphoid compartments; rather, it appeared to be more associated with their functionality, particularly in mucosal tissues. We have observed that in SIVmac251-infected macaques, while the functional capacity of tetramer-positive cells in blood, spleen, and lymph nodes did not discriminate between animals with different virological and clinical outcomes, the functional capacity of these cells in mucosal tissues appeared to do so better: macaques with undetectable functional virus-specific CD8+ T cells in mucosal tissues controlled viremia less well than macaques with such detectable function, measured by either cytokine production or cytolytic activity. Finally, we observed that the loss of virus-specific CD8+ function in macaques that failed to control viremia was associated with a lower level of CD4+ helper T cells in systemic and mucosal sites.

While the Mamu-A*01-positive group as a whole was quite effective in controlling SIVmac251 infection following intrarectal exposure (Pal et al., submitted), three of these animals failed to control viral replication over time. This provided us with an opportunity to investigate which immune parameters were associated with control of viral replication. Extensive analysis of the frequency of specific CD8+ T cells in peripheral or systemic lymphoid tissues showed that macaques that failed to control viral replication had comparable or higher frequencies of tetramer-positive CD8+ T cells in blood and tissues when compared to macaques that controlled viral replication. In some of the macaques studied here, the Gag 181-tetramer-positive T cells manifested limited or no functional capability, as determined by ex vivo cytolytic T-cell activity or capacities to produce IFN-γ or TNF-α in response to antigen. It was thus apparent that, while the population of tetramer-positive cells was induced to expand by the presence of virus in vivo, these cells were not necessarily effective in elaborating IFN-γ or TNF-α in vitro.

These findings became more evident with respect to CD8+ T cells in the mucosal tissues when comparisons of intestinal tissues were made between animals that controlled viral replication and the animals that had high levels of virus. In some cases, tetramer-positive cells were functionally active with respect to IFN-γ production and cytotoxic T-cell function. In others, such as macaque 408, which did not control viremia at all, despite the presence of a high frequency (8.5%) of Gag 181-tetramer-positive CD8+ T cells in the colon, IFN-γ production was not observed in this compartment. Similarly, in macaques 444 and 3070 that also failed to control viremia, a smaller number of Gag 181-tetramer-positive CD8+ T cells or none at all produced IFN-γ or TNF-α in mucosal tissue.

Thus, the picture that emerges is that control of viremia with respect to this particular Gag epitope may be associated with the persistence or retention of functionally active CD8+ T cells in mucosal tissues. In fact, even though high-frequency response to this specific peptide alone does not appear to be fully protective (15, 45), the identification of viral escape mutant viruses within this epitope suggests that immunological pressure is exerted in vivo (9). While the results presented here are tantalizing, they need to be considered within the limitation of the relatively small number of macaques studied. In another study, however, similar conclusions were reached when a relatively small cohort of macaques were followed longitudinally after SIVmac239 infection (43). In our study, because of the complexities of the assays and the number of samples, all the assays could not be performed simultaneously in each animal tissue. Nevertheless, we believe that these data provide the impetus to further assess this hypothesis because, if this hypothesis is true, it will have important implications in the development of strategies for immune intervention in HIV- or SIV-infected hosts (16a). Our preliminary results are consistent with the finding in murine vaccine studies showing that control of virus in the gastrointestinal mucosa requires that CTLs be present in the local mucosa, not just in the systemic immune system (4).

The fact that virus-specific CD8+ T cells appear to be important in control of HIV and SIV replication (8, 17, 19, 24, 28, 29, 31, 32, 35, 37) has led to the hypothesis that the level of viremia during the chronic phase of infection results from an equilibrium between the number of infected cells killed by CD8+ T cells and the number of newly infected cells that are able to produce virus prior to death. These relationships, however, raise a question of how viral replication is controlled. One possibility, suggested by the data here, is that the quality of the response is more important than the quantity and that it is the number of functionally active cells that actually counts for control of viral replication. In this regard, the data showing that control of replication was associated more with the presence of functionally active CTLs in the GALT than in systemic compartments suggest that active viral replication may occur in the GALT of infected macaques, consistent with previous observations (16, 25, 30, 42).

A second question relates to the factors that determine whether CTLs maintain their functionality. Notwithstanding the fact that viral immune escape may also have occurred in some animals (9), the data presented here show that CTL function was associated with the presence of CD4+ T cells and that levels of the latter remained higher in the GALT of the macaques that controlled viral replication than in those that did not. This provides support for the hypothesis mentioned in the introduction that, in animals that maintain a strong enough CD8+ T-cell response to control viral replication and therefore prevent CD4+ depletion, higher level of CD8+ T-cell function is maintained and viral replication may in turn be controlled. In addition, the level of CD4+ response may vary among these macaques because of differences in major histocompatibility complex class II molecules. These genetic differences could in part account for variation in the ability to control virus.

If the hypothesis that the ability of macaques to naturally control SIV replication is related to the maintenance of functional CTL responses to predominant epitopes in the GALT is true and can be confirmed in a study with a number of animals sufficient to obtain statistically significant results, then the success of immunization should also relate to this critical factor. Support for this concept was recently reported in murine vaccine studies in which protection against mucosal transmission of a surrogate virus was found to require CD8+ CTLs in the GALT, not just in the spleen (4). Furthermore, in a recent comparison of systemic and mucosal immunization of macaques with peptides, greater reduction of SHIVKU2 viremia by mucosal immunization was related to higher levels of CTLs in the gut and a more effective clearance of virus from the gut (I. Belyakov et al., submitted for publication). In future studies it will therefore be important to determine whether various forms of immunization result in both robust virus-specific CD8+ T-cell responses as measured by tetramer staining and by functional assays such as CTL activity and IFN-γ production, both in the systemic lymphoid tissues and in the GALT.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank O. Narayan for the SHIVKU2 virus, Nancy R. Miller for helpful discussion, and Steven Snodgrass and Sara Kaul for editorial assistance.

M.G.L. is supported by contract NIH-NIAID-AI-65312.

REFERENCES

- 1.Allen T M, Mothe B R, Sidney J, Jing P, Dzuris J L, Liebl M E, Vogel T U, O'Connor D H, Wang X, Wussow M C, Thomson J A, Altman J D, Watkins D I, Sette A. CD8+ lymphocytes from simian immunodeficiency virus-infected rhesus macaques recognize 14 different epitopes bound by the major histocompatibility complex class I molecule mamu-A*01: implications for vaccine design and testing. J Virol. 2001;75:738–749. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.2.738-749.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altman J D, Moss P A H, Goulder P J R, Barouch D H, McHeyzer-Williams M G, Bell J I, McMichael A J, Davis M M. Phenotypic analysis of antigen-specific T lymphocytes. Science. 1996;274:94–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Appay V, Nixon D F, Donahoe S M, Gillespie G M A, Dong T, King A, Ogg G S, Spiegel H M L, Conlon C, Spina C A, Havlir D V, Richman D D, Waters A, Easterbrook P, McMichael A J, Rowland-Jones S L. HIV-specific CD8+ T cells produce antiviral cytokines but are impaired in cytolytic function. J Exp Med. 2000;192:63–75. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.1.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Belyakov I M, Ahlers J D, Brandwein B Y, Earl P, Kelsall B L, Moss B, Strober W, Berzofsky J A. The importance of local mucosal HIV-specific CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes for resistance to mucosal viral transmission in mice and enhancement of resistance by local administration of IL-12. J Clin Investig. 1998;102:2072–2081. doi: 10.1172/JCI5102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boirivant M, Fuss I, Fiocchi C, Klein J S, Strong S A, Strober W. Hypoproliferative human lamina propria T cells retain the capacity to secrete lymphokines when stimulated via CD2/CD28 pathways. Proc Assoc Am Physicians. 1996;108:55–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Borrow P, Lewicki H, Hahn B H, Shaw G M, Oldstone M B A. Virus-specific CD8+ cytotoxic T-lymphocyte activity associated with control of viremia in primary human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. J Virol. 1994;68:6103–6110. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.9.6103-6110.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cardin R D, Brooks J W, Sarawar S W, Doherty P C. Progressive loss of CD8+ T cell-mediated control of a γ-herpesvirus in the absence of CD4+ T cells. J Exp Med. 1996;184:863–871. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.3.863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carmichael A, Jin X, Sissons P, Borysiewicz L. Quantitative analysis of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1)-specific cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) response at different stages of HIV-1 infection: differential CTL responses to HIV-1 and Epstein-Barr virus in late disease. J Exp Med. 1993;177:249–256. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.2.249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen Z W, Craiu A, Shen L, Kuroda M J, Iroku U C, Watkins D I, Voss G, Letvin N L. Simian immunodeficiency virus evades a dominant epitope-specific cytotoxic T lymphocyte response through a mutation resulting in the accelerated dissociation of viral peptide and MHC class I. J Immunol. 2000;164:6474–6479. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.12.6474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Couillin I, Culmann-Penciolelli B, Gomard E, Choppin J, Levy J P, Guillett J G, Saragosti S. Impaired cytotoxic T lymphocyte recognition due to genetic variations in the main immunogenic region of the human immunodeficiency virus 1 NEF protein. J Exp Med. 1994;180:1129–1134. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.3.1129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Donahoe S M, Moretto W J, Samuel R V, Marx P A, Hanke T, Connor R I, Nixon D F. Direct measurement of CD8+ T cell responses in macaques infected with simian immunodeficiency virus. Virology. 2000;272:347–356. doi: 10.1006/viro.2000.0404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goepfert P A, Bansal A, Edwards B H, Ritter G D, Tellez I, McPherson S A, Sabbaj S, Mulligan M J. A significant number of human immunodeficiency virus epitope-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes detected by tetramer binding do not produce gamma interferon. J Virol. 2000;74:10249–10255. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.21.10249-10255.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goulder P J, Tang Y, Brander C, Betts M R, Altfeld M, Annamalai K, Trocha A, He S, Rosenberg E S, Ogg G, O'Callaghan C A, Kalams S A, McKinney R E, Mayer K, Koup R A, Pelton S I, Burchett S K, McIntosh K, Walker B D. Functionally inert HIV-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes do not play a major role in chronically infected adults and children. J Exp Med. 2000;192:1819–1832. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.12.1819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goulder P J R, Phillips R E, Colbert R A, McAdam S, Ogg G, Nowak M A, Giangrande P, Luzzi G, Morgan B, Edwards A, McMichael A J, Rowland-Jones S. Late escape from an immunodominant cytotoxic T-lymphocyte response associated with progression to AIDS. Nat Med. 1997;3:212–217. doi: 10.1038/nm0297-212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hanke T, Samuel R V, Blanchard T J, Neumann V C, Allen T M, Boyson J E, Sharpe S A, Cook N, Smith G L, Watkins D I, Cranage M P, McMichael A J. Effective induction of simian immunodeficiency virus-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes in macaques by using a multiepitope gene and DNA prime-modified vaccinia virus Ankara boost vaccination regimen. J Virol. 1999;73:7524–7532. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.9.7524-7532.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heise C, Miller C J, Lackner A, Dandekar S. Primary acute simian immunodeficiency virus infection of intestinal lymphoid tissue is associated with gastrointestinal dysfunction. J Infect Dis. 1994;169:1116–1120. doi: 10.1093/infdis/169.5.1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16a.Hel Z, Venzon D, Poudyal M, Tsai W-P, Giuliani L, Woodward R, Chougnet C, Shearer G M, Altman J D, Watkins D I, Bischofberger N, Abimiku A G, Markham P D, Tartaglia J, Franchini G. Viremia control following antiretroviral treatment and therapeutic immunization during primary SIV251 infection of macaques. Nat Med. 2000;6:1140–1146. doi: 10.1038/80481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jin X, Bauer D E, Tuttleton S E, Lewin S, Gettie A, Blanchard J, Irwin C E, Safrit J T, Mittler J, Weinberger L, Kostrikis L G, Zhang L, Perelson A S, Ho D D. Dramatic rise in plasma viremia after CD8+ T cell depletion in simian immunodeficiency virus-infected macaques. J Exp Med. 1999;189:991–998. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.6.991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Joag S V, Li Z, Wang C, Jia F, Foresman L, Adany I, Pinson D M, Stephens E B, Narayan O. Chimeric SHIV that causes CD4+ T cell loss and AIDS in rhesus macaques. J Med Primatol. 1998;27:59–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0684.1998.tb00227.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Klein M R, van Baalen C A, Holwerda A M, Kerkhof Garde S R, Bende R J, Keet I P, Eeftinck-Schattenkerk J K, Osterhaus A D, Schuitemaker H, Miedema F. Kinetics of Gag-specific cytotoxic T lymphocyte responses during the clinical course of HIV-1 infection: a longitudinal analysis of rapid progressors and long-term asymptomatics. J Exp Med. 1995;181:1365–1372. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.4.1365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koenig S, Conley A J, Brewah Y A, Jones G M, Leath S, Boots L J, Davey V, Pantaleo G, Demarest J F, Carter C. Transfer of HIV-1-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes to an AIDS patient leads to selection for mutant HIV variants and subsequent disease progression. Nat Med. 1995;1:330–336. doi: 10.1038/nm0495-330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kostense S, Ogg G S, Manting E H, Gillespie G, Joling J, Vandenberghe K, Veenhof E Z, van Baarle D, Jurriaans S, Klein M R, Miedema F. High viral burden in the presence of major HIV-specific CD8+ T cell expansions: evidence for impaired CTL effector function. Eur J Immunol. 2001;31:677–686. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200103)31:3<677::aid-immu677>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kuroda M J, Schmitz J E, Seth A, Veazey R S, Nickerson C E, Lifton M A, Dailey P J, Forman M A, Racz P, Tenner-Racz K, Letvin N L. Simian immunodeficiency virus-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes and cell-associated viral RNA levels in distinct lymphoid compartments of SIVmac-infected rhesus monkeys. Blood. 2000;96:1474–1479. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lechner F, Wong D K, Dunbar P R, Chapman R, Chung R T, Dohrenwend P, Robbins G, Phillips R, Klenerman P, Walker B D. Analysis of successful immune responses in persons infected with hepatitis C virus. J Exp Med. 2000;191:1499–1512. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.9.1499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Matano T, Shibata R, Siemon C, Connors M, Lane H, Martin M A. Administration of an anti-CD8 monoclonal antibody interferes with the clearance of chimeric simian/human immunodeficiency virus during primary infections of rhesus macaques. J Virol. 1998;72:164–169. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.1.164-169.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mattapallil J J, Smit-McBride Z, McChesney M, Dandekar S. Intestinal intraepithelial lymphocytes are primed for gamma interferon and MIP-1β expression and display antiviral cytotoxic activity despite severe CD4+ T-cell depletion in primary simian immunodeficiency virus infection. J Virol. 1998;72:6421–6429. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.8.6421-6429.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McChesney M B, Collins J R, Miller C J. Mucosal phenotype of antiviral cytotoxic T lymphocytes in the vaginal mucosa of SIV-infected rhesus macaques. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir. 1998;14(Suppl. 1):S63–S66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Murphey-Corb M, Wilson L A, Trichel A M, Roberts D E, Xu K, Okhawa S, Woodson B, Bohm R, Blanchard J. Selective induction of protective MHC class I-restricted CTL in the intestinal lamina propria of rhesus monkeys by transient SIV infection of the colonic mucosa. J Immunol. 1999;162:540–549. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nixon D F, Townsend A R M, Elvin J G, Rizza C R, Gallwey J, McMichael A J. HIV-1 Gag-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes defined with recombinant vaccinia virus and synthetic peptides. Nature. 1988;336:484–487. doi: 10.1038/336484a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ogg G S, Jin X, Bonhoeffer S, Dunbar P R, Nowak M A, Monard S, Segal J P, Cao Y, Rowland-Jones S L, Cerundolo V, Hurley A, Markowitz M, Ho D D, Nixon D F, McMichael A J. Quantitation of HIV-1-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes and plasma load of viral RNA. Science. 1998;279:2103–2106. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5359.2103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.O'Neil S P, Mossman S P, Maul D H, Hoover E A. In vivo cell and tissue tropism of SIVsmmPBj14-bcl.3. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir. 1999;15:203–215. doi: 10.1089/088922299311628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pantaleo G, Demarest J F, Schacker T, Vaccarezza M, Cohen O J, Daucher M, Graziosi C, Schnittman S S, Quinn T C, Shaw G M, Perrin L, Tambussi G, Lazzarin A, Sekaly R P, Soudeyns H, Corey L, Fauci A S. The qualitative nature of the primary immune response to HIV infection is a prognosticator of disease progression independent of the initial level of plasma viremia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:254–258. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.1.254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pantaleo G, Demarest J F, Soudeyns H, Graziosi C, Denis F, Adelsberger J W, Borrow P, Saag M S, Shaw G M, Sekaly R P. Major expansion of CD8+ T cells with a predominant V beta usage during the primary immune response to HIV. Nature. 1994;370:463–467. doi: 10.1038/370463a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Phillips R E, Rowland-Jones S, Nixon D F, Gotch F M, Edwards J P, Ogunlesi A O, Elvin J G, Rothbard J A, Bangham C R M, Rizza C R, McMichael A J. Human immunodeficiency virus genetic variation that can escape cytotoxic T cell recognition. Nature. 1991;354:453–459. doi: 10.1038/354453a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Price D A, Goulder P J, Klenerman P, Sewell A K, Easterbrook P J, Troop M, Bangham C R, Phillips R E. Positive selection of HIV-1 cytotoxic T lymphocyte escape variants during primary infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:1890–1895. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.5.1890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rinaldo C, Huang X-L, Fan Z, Ding M, Beltz L, Logar A, Panicali D, Mazzarra G, Liebmann J, Cottrill M, Gupta P. High levels of anti-human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) memory cytotoxic T-lymphocyte activity and low viral load are associated with lack of disease in HIV-1-infected long-term nonprogressors. J Virol. 1995;69:5838–5842. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.9.5838-5842.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rosenberg E S, Billingsley J M, Caliendo A M, Boswell S L, Sax P E, Kalams S A, Walker B D. Vigorous HIV-1-specific CD4+ T-cell responses associated with control of viremia. Science. 1997;278:1447–1450. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5342.1447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schmitz J E, Kuroda M J, Santra S, Sasseville V G, Simon S A, Lifton M A, Racz P, Tenner-Racz K, Dalesandro M, Scallon B J, Ghrayeb J, Forman M A, Montefiori D, Rieber E P, Letvin N L, Reimann K A. Control of viremia in simian immunodeficiency virus infection by CD8+ lymphocytes. Science. 1999;283:857–860. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5403.857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schmitz J E, Kuroda M J, Veazey R S, Seth A, Taylor W M, Nickerson C E, Lifton M A, Dailey P J, Forman M A, Racz P, Tenner-Racz K, Letvin N L. Simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV)-specific CTL are present in large numbers in livers of SIV-infected rhesus monkeys. J Immunol. 2000;164:6015–6019. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.11.6015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shacklett B L, Cu-Uvin S, Beadle T J, Pace C A, Fast N M, Donahue S M, Caliendo A M, Flanigan T P, Carpenter C C, Nixon D F. Quantification of HIV-1-specific T-cell responses at the mucosal cervicovaginal surface. AIDS. 2000;14:1911–1915. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200009080-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shankar P, Russo M, Harnisch B, Patterson M, Skolnik P, Lieberman J. Impaired function of circulating HIV-specific CD8+ T cells in chronic human immunodeficiency virus infection. Blood. 2000;96:3094–3101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Trimble L A, Shankar P, Patterson M, Daily J P, Lieberman J. Human immunodeficiency virus-specific circulating CD8 T lymphocytes have down-modulated CD3zeta and CD28, key signaling molecules for T-cell activation. J Virol. 2000;74:7320–7330. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.16.7320-7330.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Veazey R S, DeMaria M, Chalifoux L V, Shvetz D E, Pauley D R, Knight H L, Rosenzweig M, Johnson R P, Desrosiers R C, Lackner A A. Gastrointestinal tract as a major site of CD4+ T cell depletion and viral replication in SIV infection. Science. 1998;280:427–431. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5362.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vogel T U, Allen T M, Altman J D, Watkins D I. Functional impairment of simian immunodeficiency virus-specific CD8+ T cells during the chronic phase of infection. J Virol. 2001;75:2458–2461. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.5.2458-2461.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wolinsky S M, Korber B T M, Neumann A U, Daniels M, Kunstman K J, Whetsell A J, Furtado M R, Cao Y, Ho D D, Safrit J T. Adaptive evolution of human immunodeficiency virus-type 1 during the natural course of infection. Science. 1996;272:537–542. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5261.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yasutomi Y, Koenig S, Woods R M, Madsen J, Wassef N M, Alving C R, Klein H J, Nolan T E, Boots L J, Kessler J A, Emini E A, Conley A J, Letvin N L. A vaccine-elicited, single viral epitope-specific cytotoxic T-lymphocyte response does not protect against intravenous, cell-free simian immunodeficiency virus challenge. J Virol. 1995;69:2279–2284. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.4.2279-2284.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zajac A J, Blattman J N, Murali-Krishna K, Sourdive D J D, Suresh M, Altman J D, Ahmed R. Viral immune evasion due to persistence of activated T cells without effector function. J Exp Med. 1998;188:2205–2213. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.12.2205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]