Abstract

Nursing homes (NHs) have long struggled with nurse shortages, leading to a greater reliance on agency nurses. The purpose of this study was to examine the impact of NH ownership on agency nurse utilization. Data were derived from multiple sources, including the Payroll-Based Journal and NH Five-Star Facility Quality Reporting System (n: 38,550 years: 2020-2022). A 2-part logistic regression model with 2-way fixed effects (state and year) was used to assess the association of ownership and agency nurse utilization. Model 1 compared facilities with and without agency nurse use, while Model 2 focused on NHs using agency nurses, examining high utilization (top 10%). The dependent variables were agency nurse utilization ratios for registered nurses (RNs), licensed practical nurses (LPNs), and certified nursing assistants (CNAs). The primary independent variable was ownership/chain affiliation: for-profit chain (FPC), for-profit independent (FPI), not-for-profit chain (NFPC), and not-for-profit independent (NFPI). Model 1 showed that NFPC facilities had higher odds of using agency RNs (OR = 1.65), LPNs (OR = 1.53), and CNAs (OR = 1.38) compared to NFPI facilities (all P < .001), while FPC facilities also had increased odds for RNs (OR = 1.43), LPNs (OR = 1.30), and CNAs (OR = 1.15) (all P < .001). Model 2 indicated that NFPC, FPC, and FPI facilities were more likely to be high utilizers (top 10%) of agency nurses, with NFPC facilities having the highest odds across all categories. Pairwise comparisons showed that NFPC had the highest utilization of agency RNs and LPNs compared to other ownership groups. These results highlight the significant impact of NH ownership on staffing practices, suggesting that ownership type influences agency nurse utilization.

Keywords: agency nurses, contract nurses, nursing homes, ownership

What do we already know about this topic?

Nursing home ownership strongly influences performance and care quality. Nursing staff shortages, worsened by the COVID-19 pandemic, have increased nursing home’s reliance on costly agency labor.

How does your research contribute to the field?

This research provides insights into how ownership influences agency nurse utilization in nursing homes, highlighting the effects of ownership type and chain affiliation on staffing practices.

What are your research’s implications toward theory, practice, or policy?

In theory, it enhances understanding of how ownership influences nursing staff practices in nursing homes. Practically, it guides nursing home administrators and owners in developing strategies to reduce the reliance on agency nurses, potentially improving quality. For policymakers, it underscores the need for balanced regulations and supportive measures to address nurse shortages and enhance nursing home performance.

Introduction

Nursing home ownership can be understood as 4 groups based on ownership and chain affiliation: for-profit chains (FPC), for-profit independents (FPI), not-for-profit chains (NFPC), and not-for-profit independents (NFPI). 1 Organizational structure is a critical factor influencing nursing home performance. The extant literature suggests that different ownership models exhibit varied responses to cost pressures, market dynamics, and regulatory demands. 2 Consequently, ownership can influence important aspects of nursing home performance including quality of care, resident well-being, and the broader industry landscape.3,4

One potential mechanism through which ownership may affect nursing home performance is through human resource outcomes. Nurses are primary caregivers in nursing homes and are essential for improving resident outcomes, including reducing the prevalence of pressure ulcers, emergency department visits, and COVID-19-related cases and mortality.5,6 However, nursing homes have long struggled with chronic nurse shortages for various reasons, such as low salaries, competition from other healthcare organizations such as hospitals, and onerous administrative burdens. 5 With 1 out of every 3 facilities reporting shortages, staffing remains “a bit of a mess” post the COVID-19 pandemic, 7 and the nurse scarcity is expected to persist into the foreseeable future.8,9

To address staffing challenges, healthcare organizations rely on contract or agency staff, temporary workers employed by third-party agencies who fill in staffing gaps across various facilities. 10 Agency nurses provide several cost-containment benefits such as flexible scheduling, reduced overtime for regular staff, and eliminating the need to establish additional permanent positions, particularly in response to temporary surges in patient populations.7,11 Agency nurses enable nursing homes to meet minimum staffing standards and can help facilities manage unanticipated shortages due to high turnover or absenteeism. However, the acute nursing staff shortage triggered by the COVID-19 pandemic 12 has significantly increased the utilization of agency nurses in nursing homes. 13

While agency nurses appear as a convenient option to plug urgent staffing gaps, their increased use raises apprehensions about potential negative impacts on nursing home performance. 14 As agency nurses are transient in nature, they lack crucial institutional knowledge and understanding of resident-specific needs. 15 This deficit may contribute to missed cues, communication breakdowns, and suboptimal resident outcomes.16,17 Moreover, the financial implications are significant: the median wage for agency nurses is 50% higher than that of regular full-time equivalent (FTE) nurses. 13 This additional cost can strain nursing home budgets and compromise their ability to invest in high-quality care.

The literature has highlighted organizational factors, such as ownership, as crucial determinants of nursing home performance. The factors have been linked with nursing home quality, 18 staff turnover, 19 COVID-19 related cases and mortality,20 -22 and financial performance.1,23 However, the specific influence of ownership on agency nurse utilization remains underexplored. Castle proposed a conceptual model to examine the use of agency staff in nursing homes, but this model was primarily derived from the hospital literature, and its data may be outdated. 24

Recognizing the critical role nurses play in determining nursing home performance and the evident research gap; the primary purpose of this study was to investigate the association of nursing home ownership on agency nurse utilization. We examined the joint effects of ownership and chain affiliation by classifying nursing homes into 4 possible interactions of ownership and chain affiliation: FPC, FPI, NFPI, and NFPC. 1 The insights gained from this study can potentially inform managerial strategies and policy instruments aimed at addressing the significant nursing staff challenge nursing homes face.

Conceptual Framework

The Resource Dependency Theory (RDT) posits that an organization’s success hinges on its adeptness at acquiring, retaining, and efficiently utilizing resources. 25 In the context of nursing homes, essential resources such as skilled nurses are crucial for delivering high-quality care.5,26 However, the acute nursing shortage has forced nursing homes to rely on external staffing agencies, creating dependencies and environmental uncertainties. 13 Recruiting agency nurses becomes a necessary response to these challenges, to ensure a consistent supply of caregivers. 25

For-profit nursing homes prioritize maximizing profits and are stringent in cost management practices. 1 While essential for any business, this focus can adversely affect staffing and care quality.4,27 Nursing homes have generally struggled to attract skilled nurses; however, in for-profit nursing homes, this problem may be more acute due to their profit-maximizing behavior. For instance, the cost of salaries, benefits, and training for permanent nursing staff constitutes a significant portion of overall operating expenses in nursing homes. To minimize these costs, for-profit nursing homes may choose to hire fewer permanent staff and instead rely on agency nurses. 28 Agency nurses can be employed on an as-needed basis without long-term financial commitments, making them a more flexible and cost-effective solution for covering staffing gaps. Furthermore, agency staff can shield nursing homes from sudden shortages due to high turnover or absenteeism. Therefore, for-profit nursing homes may perceive using agency nurses as a strategic cost containment initiative 11 justifying the seemingly contradictory behavior of relying on costlier agency nurses in a profit-maximizing context.

Additionally, for-profit nursing homes may offer less attractive working conditions including lower wages, fewer benefits, and higher resident-to-nurse ratios, which can lead to job dissatisfaction and burnout. 29 Furthermore, for-profit nursing homes may make fewer investments in staff development, training, and support systems because of the emphasis on cost reduction. This lack of investment may feed into a vicious cycle of high nurse turnover 19 leading to a growing reliance on agency nurses to cover shortages. As a result, for-profit nursing homes may be compelled to depend more heavily on agency nurses.

Although not-for-profit nursing homes can generate an income surplus, they are obligated to reinvest these surpluses into operational improvements that directly benefit their “beneficiary stakeholders,” namely residents and staff. This reinvestment in staff development, higher wages, better benefits, and improved working conditions can enhance job satisfaction and retention. Consequently, NFPs may be less reliant on agency nurses to fill staffing gaps, as they can attract and retain a more stable and permanent nursing workforce.

System affiliation may have an additive effect on agency nurse utilization across both for-profit and NFP nursing homes. System affiliation can exacerbate reliance on agency nurses due to the emphasis on standardized procedures and cost-cutting measures across the chain. 30 The centralized decision-making in these chain-affiliated facilities can reduce flexibility in staffing strategies, increasing the need for agency staff to address unexpected shortages. System affiliation often introduces more complex management structures and broader operational demands, leading to increased reliance on agency nurses to meet fluctuating staffing needs across multiple facilities. In contrast, FPIs and NFPIs may have more localized control and flexibility, allowing them to maintain a more stable workforce and reduce their reliance on agency nurses. Therefore, we anticipate that the joint impact of ownership and chain affiliation will result in a hierarchical performance scenario, where FPCs are likely to exhibit the highest agency nurse utilization, while NFPI nursing homes will report the lowest use of agency nurses. FPI and NFPC nursing homes are expected to fall in the middle between FPC and NFPI in their utilization of agency nurses. Previous studies have indicated that exploring the combined impacts of ownership and chain affiliation can provide a more nuanced understanding of nursing home performance.1,2

Based on the resource dependency theory and the preceding discussion, we hypothesize that,

Hypothesis 1: FPC nursing homes will report the highest agency nurse utilization.

Hypothesis 2: NFPI nursing homes will report the lowest agency nurse utilization.

Hypothesis 3a: FPI and NFPC nursing homes’ agency nurse utilization will be in the middle between FPC and NFPI nursing homes.

Hypothesis 3b: FPI and NFPC nursing homes will not have significantly different agency nurse utilization rates.

Methods

Data Sources

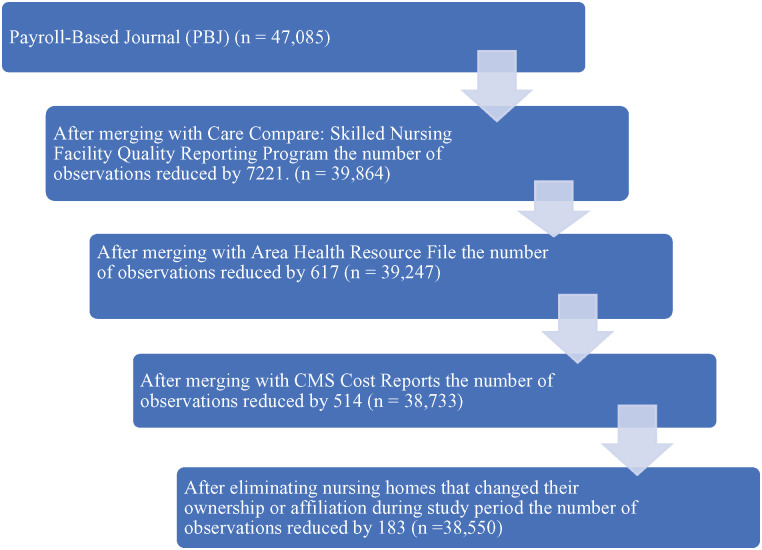

The following secondary datasets were used to conduct this study: Payroll-Based Journal (PBJ), 31 Care Compare: Five-Star Facility Quality Reporting System (Five-Star QRS), 32 Brown University’s Long Term Care Focus (LTCFocus.org), 33 Healthcare Cost Report Information System (HCRIS), and the Area Health Resources Files (AHRF) 34 for the study period 2020 to 2022. The PBJ provides detailed, auditable data into staffing patterns within nursing homes. Five-Star QRS was used to derive data on nursing home quality, while the HCRIS was used to obtain nursing home financial data. LTCFocus.org provided organizational and demographic information for nursing homes. AHRF was used to derive county-level socio-demographic data. The Medicare identification numbers was used to merge the different datasets, except AHRF that were merged using Federal Information Processing System (FIPS) code. The final analytic data file comprised 38, 550 nursing home-years with an average of 12. 850 unique facilities per year. Please see Figure 1 for the data merge steps.

Figure 1.

Flowchart showing the sample size at each step of merging data.

Variables

Dependent variables: Nursing homes typically employ 3 different types of nursing staff: registered nurses (RNs), licensed practical nurses (LPNs), and certified nursing assistants (CNAs). RNs are the crucial architects of nursing home quality playing critical clinical roles in infection control, care plans, resident assessments, and are also expected to manage and motivate staff. 5 On the other hand, CNAs typically assist residents with activities of daily living (ADL), and they may have the most comprehensive understanding of immediate resident needs. 35

In our study, the dependent variables were the agency nurse utilization ratios, which represent the ratio of agency nurse hours to total nurse hours (calculated at the facility level for RNs, LPNs, and CNAs). This calculation was based on the PBJ data, which offers a daily record of the number of hours worked by each category of nurse and indicates whether the nurse is a staff employee or a contractually employed. 13

Independent variable: The primary independent variable is ownership/chain affiliation, which represents a categorical variable of the 4 possible interactions of an organization’s FP status and chain affiliation: FPC, FPI, NFPC, and NFPI.

Control Variables:

We controlled for facility-level and community-level characteristics of a nursing home that may affect its reliance on agency nurses.36,37 Facility-level control variables include the following: nurse (RN, LPN, and CNA) hours per resident day (PRD) as a measure of nursing intensity, nursing home payer-mix (percentages of Medicare, Medicaid, and private-pay residents), occupancy rate (percentage of occupied beds), size (number of beds), percentage of racial/ethnic minority residents (Black, Hispanic and other), Five-star rating as a measure of nursing home quality, and financial performance (operating margin).

We also controlled for the following nursing home community-level characteristics at the county level: supply of nurses at the county level (RN, LPN, and CNA FTEs per thousand population). percentage of the population 65 years and older, uninsurance rate, household income (pretax cash income of the householder and all other people 15 years and older in the household, whether or not they are related to the householder), 38 Medicare Advantage (MA) penetration (percentage of Medicare beneficiaries in MA), and market competition. Competition was assessed using the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI), a metric that evaluates market concentration within an industry. It is calculated by summing the squared value of each NH’s market share based on NH inpatient days, with values ranging between 0 and 100. Higher values suggest greater market concentration, indicating more monopolistic markets, while lower values indicate higher competition.

Analysis

Our unit of analysis was the nursing home. We used descriptive statistics to summarize our dependent, independent, and control variables: mean and standard deviation for continuous variables and frequency and percent for categorical variables. We used ANOVA to examine differences in continuous variables related to agency nurse utilization across the 4 ownership groups and chi-square tests for differences in categorical variable (Table 1).

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics of Study Variables by Ownership Group (n = 38 550).

| Variables | NFPI | NFPC | FPI | FPC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Use of agency RNs (0 = No) | 2438 (51.57%)*** | 1921 (41.70%)*** | 5300 (49.92%)*** | 8553 (46.00%)*** |

| Use of agency RNs (1 = Yes) | 2288 (48.43%)*** | 2684 (58.30%)*** | 5316 (50.08%)*** | 10 039 (54.00%)*** |

| Use of agency LPNs (0 = No) | 2096 (44.35%)*** | 1696 (36.82%)*** | 4648 (43.77%)*** | 7475 (40.21%)*** |

| Use of agency LPNs (1 = Yes) | 2630 (55.65%)*** | 2909 (63.18%)*** | 5968 (56.23%)*** | 11 117 (59.79%)*** |

| Use of agency CNAs (0 = No) | 1910 (40.42%)*** | 1588 (34.49%)*** | 4438 (41.81%)*** | 7254 (39.02%)*** |

| Use of agency CNAs (1 = Yes) | 2816 (59.58%)*** | 3017 (65.51%)*** | 6178 (58.19%)*** | 11 338 (60.98%)*** |

| Size (beds) | 81. 63 (62.58)*** | 72.58 (41.18)*** | 88.22 (54.81)*** | 77.96 (36.51)*** |

| One-star quality rating | 205 (4.31%)*** | 151 (3.26%)*** | 750 (7.10%)*** | 1057 (5.68%)*** |

| Two-star quality rating | 537 (11.28%)*** | 482 (10.40%)*** | 1561 (14.78%)*** | 2637 (14.18%)*** |

| Three-star quality rating | 894 (18.78%)*** | 992 (21.41%)*** | 2145 (20.31%)*** | 4088 (21.98%)*** |

| Four-star quality rating | 1312 (27.57%)*** | 1347 (29.07%)*** | 2626 (24.86%)*** | 5044 (27.13%)*** |

| Five-star quality rating | 1812 (38.06%)*** | 1662 (35.86%)*** | 3480 (32.95%)*** | 5774 (31.03%)*** |

| Operating margin | 1.44 (22.98)*** | 1.55 (22.89)*** | 6.63 (19.22)*** | 9.16 (21.59)*** |

| Occupancy rate | 72 (19.52) | 72 (24.88) | 73 (18.29) | 72 (61.96) |

| RN hours per resident day | 0.57 (0.38)*** | 0.56 (0.38)*** | 0.4 (0.3)*** | 0.4(0.28)*** |

| LPN hours per resident day | 0.82 (0.39)*** | 0.80 (0.35)*** | 0.84 (0.35)*** | 0.82 (0.30)*** |

| CNA hours per resident day | 2.49 (0.66)*** | 2.19 (0.63)*** | 2.09 (0.6)*** | 1.95 (0.50)*** |

| Percentage of Medicaid residents | 47.89 926.36)*** | 46.95 (26.75)*** | 58.55 (24.55)*** | 58.58 (24.65)*** |

| Percentage of Medicare residents | 12.08 (12.15) | 13.45 (11.63) | 15.42 (13.59) | 13.92 (11.82) |

| Percentage of Black residents | 4.35 (12.82)*** | 4.72 (12.40)*** | 10.70 (18.50)*** | 9.42 (17.53)*** |

| Percentage of Hispanic residents | 1.26 (6.66)*** | 1.51 (7.75)*** | 5.04 (12.55)*** | 3.16 (10.39)*** |

| Percentage of other residents | 6.43 (12.18)*** | 6.79 (11.27)*** | 10.97 (16.27)*** | 8.93 (12.99)*** |

| RN FTE per thousand population | 5.27 (4.66)*** | 5.24 (3.65)*** | 5.06 (3.89)*** | 5.07 (3.9)*** |

| LPN FTE per thousand population | 0.4 (0.56)*** | 0.37 (0.47)*** | 0.36 (0.51)*** | 0.38(0.47)*** |

| CNA FTE per thousand population | 1.97 (1.92)*** | 1.91 (1.45)*** | 1.85 (1.84)*** | 1.86 (1.65)*** |

| Population 65 years and over | 18.52 (4.30)*** | 17.96 (4.13)*** | 17.56 (3.90)*** | 18.00 (4.31)*** |

| Uninsurance rate | 9.64 (4.66)*** | 10.04 (4.86)*** | 10.57 (4.93)*** | 10.95 (5.02)*** |

| Household income (USD) | 64298.12 (16394.43)*** | 64449.71 (16393.24)*** | 65014.94 (18745.33)*** | 62608.89 (16988.97)*** |

| Medicare advantage penetration | 38.78 (14.74)*** | 40.25 (13.60)*** | 41.46 (13.47)*** | 40.87 (13.24)*** |

| Competition (HHI) | 22.91 (26.13)*** | 19.81 (22.94)*** | 18.21 (23.86)*** | 21.47 (24.91)*** |

Note. N = number of nursing homes; NFPI = not-for-profit independent; NFPC = not for profit chain; FPI = for profit independent; FPC = for profit chain; RNs = registered nurses; LPNs = licensed practical nurses; CNAs = certified nursing aides; FTE = full-time equivalent; USD = United States Dollar; HHI = Herfindahl–Hirschman Index.

P < .05. **P < .01. *** P < .001.

To examine our hypotheses, we employed a 2-part logistic regression model with 2-way fixed effects (state and year) to assess the association between ownership and agency nurse utilization. The first model compared facilities that reported no use of agency nurses with those that did, focusing on the likelihood of using agency nurses. The second model focused on nursing homes that utilized agency nurses, examining the relationship between ownership and the level of agency nurse usage. The dependent variable was dichotomized, distinguishing between the top 10% of nursing homes with the highest utilization of agency nurses and the remaining 90%. This 90-10 split was selected to capture the greatest incremental change in agency nurse utilization, as observed at the 90th percentile, where utilization increased most sharply across the interquartile range (Supplemental Figure 1). The threshold values for incremental change were as follows: 20.53 for Agency RN Utilization, 25.89 for Agency LPN Utilization, and 23.85 for Agency CNA Utilization. Separate models were run for each type of agency nurses: RNs, LPNs, and CNAs. We also conducted sensitivity analysis using the 85-15 threshold and the results are broadly similar (Supplemental Table 2). We found no evidence of multicollinearity among the variables (ie, Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) ≤5, r < .8). All statistical analyses were conducted using Stata 16.1, with statistical significance evaluated at an alpha level of .05 or smaller.

Results

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics for the dependent and independent variable for the 4 ownership groups. Among the facilities using agency RNs, NFPC facilities are the highest users at 58.3% (P < .001), while NFPI facilities are the lowest users at 48.43% (P < .001). In terms of agency LPNs, NFPC facilities are the highest users at 63.18% (P < .001), and NFPI facilities are the lowest users at 55.65% (P < .001). For CNAs, NFPC facilities are the highest users at 65.51% (P < .001), while FPI facilities are the lowest users at 58.18% (P < .001).

Comparing the quality ratings, FPI facilities have the highest proportion of one-star ratings at 7.10% (P < .001), while NFPI facilities have the highest proportion of five-star ratings at 38.06% (P < .001). FPC facilities reported the highest operating margin at 9.16 (P < .001), while NFPI facilities had the lowest at 1.44 (P < .001). NFPI facilities reported the highest hours for both RNs (0.57, P < .001) and CNAs (2.49, P < .001), while LPN hours were highest in FPI facilities (0.84, P < .001). Additionally, FPI facilities were located in counties with the highest level of competition (HHI = 18.21, P < .001), while NFPI facilities had the lowest Medicare Advantage (MA) penetration (38.78%, P < .001).

Table 2 presents the results from the first logistic regression, which revealed significant differences in the odds of using agency nurses across the 4 ownership groups, with NFPI as the reference group. NFPC facilities had 65% higher odds (OR = 1.65, P < .001), FPC facilities had 43% higher odds (OR = 1.43, P < .001), and FPI had 27% higher odds (OR = 1.27, P < .001) of using agency RNs, compared to NFPI facilities. For agency LPN use, NFPC facilities had 53% higher odds (OR = 1.53, P < .001), FPC facilities had 30% higher odds (OR = 1.30, P < .001), and FPI had 14% higher odds (OR = 1.14, P < .01) compared to NFPI facilities. Similarly, for agency CNA use, NFPC facilities had 38% higher odds (OR = 1.38, P < .001) and FPC facilities had 15% higher odds (OR = 1.15, P < .001) compared to NFPI facilities.

Table 2.

Logistic Regression Showing Association Between Ownership with Use and Non-use of Agency RNs, LPNs and CNAs (N = 38, 550).

| Agency RNs Odds ratio |

Agency LPNs Odds ratio |

Agency CNAs Odds ratio |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Ownership group (NFPI: Reference) | |||

| NFPC | 1.65*** | 1.53*** | 1.38*** |

| FPI | 1.27*** | 1.14** | 1.07 |

| FPC | 1.43*** | 1.30*** | 1.15*** |

| Organizational characteristics | |||

| Size (beds) | 1.003*** | 1.004*** | 1.003*** |

| Quality (one-star rating: Reference) | |||

| Two-star rating | 1.02 | 0.98 | 0.97 |

| Three-star rating | 0.86** | 0.83*** | 0.87** |

| Four-star rating | 0.79*** | 0.72*** | 0.76*** |

| Five-star rating | 0.66*** | 0.57*** | 0.67*** |

| Operating margin | 0.99*** | 0.99*** | 0.99*** |

| RN hours per resident day | 0.75*** | ||

| LPN hours per resident day | 1.32*** | ||

| CNA hours per resident day | 0.84*** | ||

| Occupancy rate | 1.00 | 1.00* | 1.00** |

| Percentage of Medicare residents | 1.00 | 1.00* | 1.00 *** |

| Percentage of Medicaid residents | 1.002** | 1.002** | 0.10 |

| Percentage of Black residents | 1.01*** | 1.01*** | 1.003*** |

| Percentage of Hispanic residents | 0.99*** | 0.99*** | 0.99*** |

| Percentage of Other residents | 1.003** | 1.004*** | 1.001 |

| Market characteristics | |||

| RN FTE per thousand population | 1.02*** | ||

| LPN FTE per thousand population | 1.01 | ||

| CNA FTE per thousand population | 1.04*** | ||

| Population 65 years and over | 0.10 | 0.10 | 1.001 |

| Uninsurance rate | 0.97*** | 0.94*** | 0.94*** |

| Household income (USD) | 1.01*** | 1.001 | 1.002* |

| Medicare Advantage Penetration | 1.01*** | 1.01*** | 1.01*** |

| Competition (HHI) | 0.10** | 0.10*** | 0.10*** |

Note. NFPI = not-for-profit independent; NFPC = not for profit chain; FPI = for profit independent; FPC = for profit chain; RNs = registered nurses; LPNs = licensed practical nurses; CNAs = certified nursing aides; FTE = full-time equivalent; USD = United States Dollar; HHI = Herfindahl–Hirschman Index.

P < .05. ** P < .01. *** P < .001.

Table 3 presents results from the second logistic regression comparing high utilizers (top 10%) versus non-high utilizers (bottom 90%) of agency nurses, conditional on using agency nurses. For agency RN use, NFPC facilities had 32% higher odds (OR = 1.32, P < .01), FPC facilities had 25% higher odds (OR = 1.25, P < .01), and FPI facilities had 22% higher odds (OR = 1.22, P < .05) of being in the top 10% of RN users compared to NFPI facilities. For agency LPN use, NFPC facilities had 35% higher odds (OR = 1.35, P < .01) of being in the top 10% compared to NFPI. For agency CNA use, NFPC facilities had 40% higher odds (OR = 1.40, P < .001), FPC facilities had 44% higher odds (OR = 1.44, P < .001), and FPI facilities had 41% higher odds (OR = 1.41, P < .001) of being in the top 10% compared to NFPI facilities.

Table 3.

Logistic Regression Showing the Association of Ownership With High (Top 10%) versus Non- High (Bottom 90%) Use of Agency RNs, LPNs and CNAs (N = 23 466).

| Agency RNs (Odds ratio) |

Agency LPNs (Odds ratio) |

Agency CNAs (Odds ratio) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Ownership (NFPI: Reference) | |||

| NFPC | 1.32** | 1.35** | 1.40*** |

| FPI | 1.22* | 1.13 | 1.41*** |

| FPC | 1.25** | 1.16 | 1.44*** |

| Organizational characteristics | |||

| Size (Beds) | 1.001 | 1.001 | 1.00E+00 |

| Quality (One-star rating: Reference) | |||

| Two-star rating | 0.87 | 0.96 | 0.90 |

| Three-star rating | 0.74** | 0.74** | 0.78* |

| Four-star rating | 0.64*** | 0.57*** | 0.66*** |

| Five-star rating | 0.59*** | 0.47*** | 0.55*** |

| Operating margin | 0.99*** | 0.99*** | 0.99*** |

| RN hours per resident day | 0.53*** | ||

| LPN hours per resident day | 0.66*** | ||

| CNA hours per resident day | 0.90* | ||

| Occupancy rate | 1.00* | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Percentage of Medicare residents | 1.01** | 1.01** | 1.002 |

| Percentage of Medicaid residents | 1.00** | 1.01*** | 1.01 |

| Percentage of Black residents | 1.01*** | 1.01** | 1.00*** |

| Percentage of Hispanic residents | 1.02*** | 0.99 | 0.99* |

| Percentage of Other residents | 1.01*** | 1.01*** | 1.001 |

| Market characteristics | |||

| RN FTE per thousand population | 1.01 | ||

| LPN FTE per thousand population | 0.99 | ||

| CNA FTE per thousand population | 1.03** | ||

| Population 65 years and over | 1.01 | 1.02* | 1.02*** |

| Uninsurance rate | 1.01 | 0.93*** | 0.96*** |

| Household income (USD) | 1.002 | 0.99** | 1.01*** |

| Medicare advantage penetration | 1.0002 | 1.001 | 1.003 |

| Competition (HHI) | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.10* |

Note. N = number of nursing homes; NFPI = not-for -profit independent; NFPC = not for profit chain; FPI = for profit independent; FPC = for profit chain; RNs = registered nurses; LPNs = licensed practical nurses; CNAs = certified nursing aides; FTE = full-time equivalent; USD = United States Dollar; HHI = Herfindahl–Hirschman Index.

P < .05. **P < .01. ***P < .001.

We calculated marginal effects to further quantify the impact of ownership on the likelihood of being in the high (top 90%) versus low (bottom 10%) categories of agency nurse users (Supplemental File, Table 1). The analysis revealed that NFPC facilities were 2 percentage points more likely to be in the high-use category for agency RNs, LPNs, and CNAs compared to NFPI facilities. FPI facilities were 1 percentage point more likely to be in the high-use category for agency RNs and 2 percentage points more likely for CNAs, with no significant difference for LPNs compared to NFPI facilities. Finally, FPC facilities were 1 percentage point more likely to be in the high-use category for both RNs and LPNs and 2 percentage points more likely for CNAs compared to NFPI facilities.

To test the hypotheses, we conducted pairwise comparisons to assess the differences in the likelihood of being in the high-use agency nurse category among the 4 ownership/chain affiliation groups (Table 4). Hypothesis 1 suggesting that FPC would report the highest agency nurse utilization was not supported. FPC facilities had significantly lower odds of being a high utilizer of agency LPNs and CNAs (OR = 0.86, P < .05) compared to NFPC. Hypothesis 2 suggesting the NFPI would report the lowest agency nurse utilization, was partially supported. NFPC (OR = 1.32, P < .01), FPI (OR = 1.21, P < .05), and FPC (OR = 1.25, P < .05) had higher odds of being a high RN agency utilizer compared to NFPI. In addition, NFPC had higher odds of being a high LPN (OR = 1.34, P < .01) and CNA (OR = 1.35, P < .01) agency utilizer compared to NFPI.

Table 4.

Pairwise Comparison for High (Top 10%) Versus Not High (Bottom 90%) Use of Agency RNs, LPNs and CNAs (N = 23 466).

| Ownership group | RNs (Odds ratio) |

LPNs (Odds ratio) |

CNAs (Odds ratio) |

|---|---|---|---|

| NFPC vs NFPI | 1.32** | 1.34** | 1.35** |

| FPI vs NFPI | 1.21* | 1.13 | 1.13 |

| FPC vs NFPI | 1.25* | 1.15 | 1.15 |

| FPI vs NFPC | 0.92 | 0.84* | 0.84* |

| FPC vs NFPC | 0.95 | 0.86* | 0.86* |

| FPC vs FPI | 1.02 | 1.02 | 1.02 |

Note. N = number of nursing homes; NFPI = not-for -profit independent; NFPC = not for profit chain; FPI = for profit independent; FPC = for profit chain; RNs = registered nurses; LPNs = licensed practical nurses; CNAs = certified nursing aides.

P < .05. **P < .01.

Hypothesis 3a suggesting that FPI and NFPC would be in the middle between FPC and NFPI nursing homes in terms of agency nurse utilization, was partially supported. As previously noted, NFPI had the lowest odds of being a high utilizer of agency nurses compared to other ownership types, except there was no significant difference between NFPI and FPI for CNA agency nursing. However, NFPC facilities had higher odds of being high utilizers of agency nurses compared to FPC. Furthermore, there was no significant difference in the odds of being high utilizers of agency nurses between FPC and FPI facilities.

Hypothesis 3b was not supported. The comparison between FPI and NFPC revealed significant differences in the odds of being a high utilizer of agency LPNs and CNAs, with FPI having lower odds of being a high utilizer compared to NFPC (LPNs: OR = 0.84, P < .05; CNAs: OR = 0.84, P < .05).

Several control variables were significant across the models. High utilizers of RN agency nurses had lower odds of having higher RN hours PRD (OR = 0.53, P < .001) and high quality, as indicted by a five-star rating (OR = 0.59, P < .001). High utilizers of LPN agency nurses had lower odds of having higher LPN hours PRD (OR = 0.66, P < .001) and high quality (OR = 0.47, P < .001). High utilizers of agency CNAs had higher odds of having higher CNA hours PRD (OR = 0.90, P < .05) and high quality (OR = 0.55, P < .001). Finally, high agency utilizers in all models had lower odds of having a higher operating margin (OR = 0.99, P < .001).

Discussion

Nursing staff is critical to nursing home performance, particularly in terms of quality. 5 However, to address the acute shortage of nursing staff, nursing homes are increasingly relying on agency nurses. 13 The primary purpose of this study was to investigate the impact of nursing home ownership on agency nurse utilization.

We had hypothesized that FPC nursing homes will experience the highest utilization of agency nurses. Contrary to our expectations, NFPC nursing homes reported higher odds of using agency nurses and generally reported the highest utilization of agency nurses across all ownership/chain affiliation groups. This trend may be attributed to several factors.

Not-for-profit nursing homes are driven by a mission to maximize resident welfare with a strong emphasis on community service. They consistently report higher quality care compared to their for-profit counterparts, a distinction often attributed to higher nursing staff level.3,4,39 However, the commitment to maintaining high care standards may lead to increased reliance on agency nurses to fill staffing gaps. Fluctuations in funding and reimbursement 40 can make it challenging to sustain a consistent full-time nursing staff. Agency nurses may provide a flexible and immediate solution to these staffing challenges, allowing not-for-profit facilities to uphold their care standards. Some facilities may strategically use agency nurses to manage variable resident loads or specific short-term needs, considering it a practical approach to maintaining high-quality care without the long-term commitment of hiring permanent staff.

On the other hand, management in for-profit nursing homes encounter several challenges, including the need to maximize shareholder profits and intense regulatory scrutiny.41,42 The pressure to maximize profits often compels management to implement cost-reduction strategies, especially as the industry faces significant reimbursement challenges. 43 For-profit nursing homes typically report lower nursing staff level, 44 and may be less inclined to hire agency nurses due to their higher costs. 13

A few results from the pair-wise comparisons are interesting. FPIs have significantly higher odds than NFPI facilities of being in the high (top 10%) of agency RN utilizers. This suggests that FPI facilities may be particularly challenged in attracting and retaining RNs, who often have multiple job opportunities in more favorable or financially lucrative environments. Prior research has shown that chain affiliation is associated with higher turnover and reduced retention among nursing home staff.29,45 However, in this study, chain affiliation appeared to exert a stronger influence on not-for-profits regarding the utilization of agency nurses. While not-for-profits would be expected to emphasize nurse autonomy and staff-centered policies, chain affiliation may compel these facilities to prioritize standardized procedures and operational efficiencies. This may diminish their focus on staff needs and increase. In contrast, for-profit facilities, which are already driven by profit motives, might not experience as significant a shift in focus due to chain affiliation. Nevertheless, more research is required to understand the motivations of different nursing home ownership types in using agency nurses. In particular, qualitative studies exploring the experiences and perspectives of staff and management within nursing homes could offer deeper insights into the reasons behind the high utilization of agency nurses.

Our study has several limitations. First, the data utilized in this study were not specifically collected to address the research questions and may lack variables necessary to fully test our hypotheses. For instance, we could not assess the impact of specific human resource practices or different leadership characteristics on the use of agency nurses. The use of secondary data also leads to additional constraints, such as missing values and its retrospective nature. While examining nursing homes on a national scale increases the generalizability of our findings, it limits our capacity to account for state-level variations in regulations and other environmental factors. However, we attempted to mitigate this limitation by including state-level fixed effects in our model. Additionally, qualitative studies could provide deeper insights into the underlying reasons for the reliance on agency nurses in different ownership and chain affiliation contexts and explain how some nursing homes are strategically able to use agency nurses to address unanticipated staffing shortages without a detrimental impact on performance.

Practice and Policy Implications

Agency nurses have historically provided a convenient solution to address the chronic nursing shortages that have long plagued the nursing home industry. Hiring agency nurses has been perceived as a strategic approach to cost containment, offering advantages such flexible scheduling, reduced overtime for regular FTE staff, and fewer permanent positions. 11 Consequently, nursing homes, particularly NFPCs, may be strategically relying on agency nurses to address immediate resident care needs.

However, the literature suggests that an overt reliance on of agency nurses may negatively impact nursing home quality.16,46 A recent study found that the increased utilization of agency staff was associated with poorer quality outcomes in U.S. hospitals. 47 Moreover, agency nurses are significantly more expensive than regular FTE nurses, 13 potentially adversely impacting nursing home financial performance. 48 While not-for-profit facilities may not face the same imperative to maximize shareholder value as their for-profit counterparts, financial sustainability is an important objective for all nursing homes irrespective of their ownership structure.

Given these factors, nursing homes should invest in recruiting and retaining regular nursing staff by offering competitive wages and comprehensive benefits (health insurance, childcare), tuition reimbursement and flexible scheduling.5,49 For NFPCs, this approach may involve refocusing on staff-centered policies that are not undermined by chain-affiliation pressures and diktats. By nurturing a supportive work environment, nursing homes have the opportunity to strengthen their workforce and lower their reliance on agency nurses. This investment in a stable, permanent workforce can enhance nursing home performance by fostering a more committed and experienced staff.

From a policy perspective, the CMS has finalized new nursing home staffing requirements, including a minimum of 0.55 RN hours PRD. 50 However, only a minority of nursing homes are currently positioned to meet these new regulatory requirements. 51 As a results, these new staffing mandates may compel nursing homes to increase their use of agency nursing staff. Policymakers should judiciously balance the laudable goal of improving nursing staff levels with the broader systemic challenges the nursing home industry faces. A thoughtful approach is necessary to ensure that well-meaning regulations do not boomerang and lead to unintended consequences.

Conclusions

Ownership in nursing homes matters. Our study demonstrates that different nursing home ownership structures are associated with varying levels of reliance on agency nurses. These findings reiterate the importance of the renewed policy and regulatory focus on nursing home ownership and its effect on quality outcomes. Additionally, increased policy attention should be directed toward the issue of agency nurses, especially as CMS has prioritized the issue of nursing staff in nursing homes. Policymakers and industry stakeholders should carefully consider the appropriate balance between financial pressures and the imperative to maintain a stable, well-trained, and committed nursing workforce to enhance the overall performance and care quality in nursing homes.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-inq-10.1177_00469580241292170 for Ownership Matters: Not-for-Profit Chain Nursing Homes Have Higher Utilization of Agency Nursing Staff by Rohit Pradhan, Akbar Ghiasi, Gregory Orewa, Shivani Gupta, Ganisher Davlyatov, Bradley Beauvais and Robert Weech-Maldonado in INQUIRY: The Journal of Health Care Organization, Provision, and Financing

Footnotes

Data Availability Statement: Publicly available datasets were analyzed for this study. The datasets used for this study are available here

(a) Payroll-based Journal: https://data.cms.gov/quality-of-care/payroll-based-journal-daily-nurse-staffing

(b) Care Compare: https://catalog.data.gov/dataset/nursing-home-compare-ed7b0

(c) LTCFcous.org: https://ltcfocus.org/

(d) Area Health Resources File: https://data.hrsa.gov/topics/health-workforce/ahrf

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This research was supported by a Texas State University Research Enhancement Program (REP) grant.

Ethical Approval and Informed Consent Statements: Prior studies of this type have been reviewed by the Texas State University Research Integrity and Compliance (RIC) office. According to the provisions in 45 CFR § 46.102 pertaining to “human subject” research, the RIC has determined that studies of this type exclusively involve the examination of anonymous originally collected from the public domain. Therefore, the RIC has concluded that research of this type does not use human subjects and is not regulated by the provisions in 45 CFR § 46.102 and therefore an IRB review of the study is not required.

Consent to Participate: Not applicable.

Consent for Publication: Not applicable.

ORCID iDs: Rohit Pradhan  https://orcid.org/0009-0006-3762-7212

https://orcid.org/0009-0006-3762-7212

Gregory Orewa  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3519-7902

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3519-7902

Bradley Beauvais  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3085-5379

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3085-5379

Robert Weech-Maldonado  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5005-0909

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5005-0909

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1. Weech-Maldonado R, Laberge A, Pradhan R, Johnson CE, Yang Z, Hyer K. Nursing home financial performance: the role of ownership and chain affiliation. Health Care Manage Rev. 2012;37(3):235-245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Harrington C, Hauser C, Olney B, Rosenau PV. Ownership, financing, and management strategies of the ten largest for-profit nursing home chains in the United States. Int J Health Serv. 2011;41(4):725-746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Harrington C. Understanding the Relationship of Nursing Home Ownership and Quality in the United States. Marketisation in Nordic Eldercare. Stockholm University; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Comondore VR, Devereaux PJ, Zhou Q, et al. Quality of care in for-profit and not-for-profit nursing homes: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2009;339:b2732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Abt Associates. Nursing home staffing study. 2023. Accessed May 15, 2024. https://edit.cms.gov/files/document/nursing-home-staffing-study-final-report-appendix-june-2023.pdf

- 6. Jutkowitz E, Landsteiner A, Ratner E, et al. Effects of nurse staffing on resident outcomes in nursing homes: a systematic review. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2023;24(1):75-81.e11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Weaver SH, Fleming K, Harvey J, Marcus-Aiyeku U, Wurmser TA. Clinical nurses' view of staffing during the pandemic. Nurs Adm Q. 2023;47(2):136-149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Murray MK. The nursing shortage: past, present, and future. J Nurs Adm. 2002;32(2):79-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Pandemic Response Accountability Committee. Review of Personnel shortages in federal health care programs during the COVID-19 pandemic. 2023. Accessed October 14, 2024. https://www.oversight.gov/sites/default/files/oig-reports/PRAC/healthcare-staffing-shortages-report.pdf https://www.pandemicoversight.gov/media/file/healthcare-staffing-shortages-report

- 10. Manias E, Aitken R, Peerson A, Parker J, Wong K. Agency nursing work in acute care settings: perceptions of hospital nursing managers and agency nurse providers. J Clin Nurs. 2003;12(4):457-466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Seo S, Spetz J. Demand for temporary agency nurses and nursing shortages. Inquiry. 2013;50(3):216-228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Brazier JF, Geng F, Meehan A, et al. Examination of staffing shortages at US nursing homes during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(7):e2325993-e2325993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bowblis JR, Brunt CS, Xu H, Applebaum R, Grabowski DC. Nursing homes increasingly rely on staffing agencies for direct care nursing: study examines nursing home staffing. Health Aff. 2024;43(3):327-335. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2023.01101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Li Y, Wang J, Zhou M. Association between staff turnover and care quality in nursing homes. JAMA Intern Med. 2024;184(3):334-335. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2023.7714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bourbonniere M, Feng Z, Intrator O, Angelelli J, Mor V, Zinn JS. The use of contract licensed nursing staff in US nursing homes. Med Care Res Rev. 2006;63(1):88-109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Castle NG. Use of agency staff in nursing homes. Res Gerontol Nurs. 2009;2(3):192-201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Davlyatov G, Weech-Maldonado R, Pradhan R, Ghiasi A, Lord J. The impact of contract nurse utilization on nursing home quality. Innov Aging. 2023;7(Suppl 1):226. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gupta A, Howell ST, Yannelis C, Gupta A. Owner incentives and performance in healthcare: private equity investment in nursing homes. Rev Financ Stud. 2024;37(4):1029-1077. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gandhi A, Yu H, Grabowski DC. High Nursing Staff turnover in nursing homes offers important quality information: study examines high turnover of nursing staff at US nursing homes. Health Aff. 2021;40(3):384-391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Chatterjee P, Kelly S, Qi M, Werner RM. Characteristics and quality of US nursing homes reporting cases of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(7):e2016930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. McGarry BE, Shen K, Barnett ML, Grabowski DC, Gandhi AD. Association of nursing home characteristics with staff and resident COVID-19 vaccination coverage. JAMA Intern Med. 2021;181(12):1670-1672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Epané JP, Zengul F, Ramamonjiarivelo Z, McRoy L, Weech-Maldonado R. Resources availability and COVID-19 mortality among US counties. Front Public Health. 2023;11:1098571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Weech-Maldonado R, Lord J, Pradhan R, et al. High Medicaid nursing homes: organizational and market factors associated with financial performance. Inquiry. 2019;56:0046958018825061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Castle NG. Perceived advantages and disadvantages of using agency staff related to care in nursing homes: a conceptual model. J Gerontol Nurs. 2009;35(1):28-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Pfeffer J, Salancik G. The External Control of Organizations: A Resource Dependence Perspective. Stanford University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Harrington C, Dellefield ME, Halifax E, Fleming ML, Bakerjian D. Appropriate nurse staffing levels for US nursing homes. Health Serv Insights. 2020;13:1178632920934785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Stall NM, Jones A, Brown KA, Rochon PA, Costa AP. For-profit long-term care homes and the risk of COVID-19 outbreaks and resident deaths. CMAJ. 2020;192(33):E946-E955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Center for Medicare Advocacy. What can and must be done about the staffing shortage in nursing homes. 2021. Accessed April 10, 2024. https://medicareadvocacy.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/Report-Staffing-Shortages-in-Nursing-Homes-07.2021.pdf

- 29. Castle NG, Engberg J. Organizational characteristics associated with staff turnover in nursing homes. Gerontologist. 2006;46(1):62-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Harrington C, Olney B, Carrillo H, Kang T. Nurse staffing and deficiencies in the largest for-profit nursing home chains and chains owned by private equity companies. Health Serv Res. 2012;47(1 Pt 1):106-128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Staffing data submission Payroll Based Journal (PBJ). 2024. Accessed August 10, 2024. https://www.cms.gov/medicare/quality/nursing-home-improvement/staffing-data-submission

- 32. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Five-star quality rating system. 2024. Accessed April 1, 2024. https://www.cms.gov/medicare/health-safety-standards/certification-compliance/five-star-quality-rating-system

- 33. LTCFocus.org. Who are we. 2023. Accessed April, 2024. https://ltcfocus.org/about

- 34. Health Resources & Services Administration. Accessed August 10, 2024. Area health resources files. 2024. https://data.hrsa.gov/topics/health-workforce/ahrf

- 35. Bonner A, Fulmer T, Pelton L, Renton M. Age-friendly nursing homes: opportunity for nurses to lead. Nurs Clin North Am. 2022;57(2):191-206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Pradhan R, Ghiasi A, Davlyatov G, Orewa GN, Weech-Maldonado R. Beyond the balance sheet: investigating the association between NHA Turnover and Nursing Home Financial Performance. Risk Manag Healthc Policy. 2024;17:249-260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Orewa GN, Davlyatov G, Pradhan R, Lord J, Weech-Maldonado R. High Medicaid nursing homes: contextual factors associated with the availability of specialized resources required to care for obese residents. J Aging Soc Policy. 2024;36(1):156-173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Guzman G. Household income: 2021. 2022. Accessed August 10, 2024. https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2022/acs/acsbr-011.pdf

- 39. Harrington C. The Nursing Home Industry: A Structural Analysis. Critical Perspectives on Aging. Routledge; 2020:153-164. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Grabowski DC, Chen A, Saliba D. Paying for nursing home quality: an elusive but important goal. Public Policy Aging Rep. 2023;33(Supplement_1):S22-S27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Temple A, Dobbs D, Andel R. Exploring correlates of turnover among nursing assistants in the National Nursing Home Survey. J Nurs Adm. 2011;41(7-8 Suppl):S34-S42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Center for Medicare Advocacy. Non-profit vs. For-profit nursing homes: is there a difference in care? 2012. Accessed April 27, 2024. https://medicareadvocacy.org/non-profit-vs-for-profit-nursing-homes-is-there-a-difference-in-care/

- 43. Weech-Maldonado R, Pradhan R, Dayama N, Lord J, Gupta S. Nursing home quality and financial performance: is there a business case for quality? Inquiry. 2019;56:0046958018825191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kaiser Family Foundation. Key issues in long-term services and supports quality. 2017. Accessed May 12, 2024. https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/key-issues-in-long-term-services-and-supports-quality/

- 45. Kennedy KA, Applebaum R, Bowblis JR. Facility-level factors associated with CNA turnover and retention: Lessons for the long-term services industry. Gerontologist. 2020;60(8):1436-1444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Castle NG, Engberg JB. The influence of agency staffing on quality of care in nursing homes. J Aging Soc Policy. 2008;20(4):437-457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Beauvais B, Pradhan R, Ramamonjiarivelo Z, Mileski M, Shanmugam R. When agency fails: an Analysis of the association between Hospital Agency staffing and Quality Outcomes. Risk Manag Healthc Policy. 2024;17:1361-1372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Ghiasi A, Davlyatov G, Pradhan R, Lord J. The impact of contract nurse utilization on nursing home financial performance. Innov Aging. 2023;7(Suppl 1):226-227. [Google Scholar]

- 49. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. The National Imperative to Improve Nursing Home Quality: Honoring Our Commitment to Residents, Families, and Staff. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; 2022. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Medicare and Medicaid Programs: Minimum Staffing Standards for Long-Term Care Facilities and Medicaid Institutional Payment Transparency Reporting Final Rule (CMS 3442-F). 2024. Accessed May 19, 2024. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/medicare-and-medicaid-programs-minimum-staffing-standards-long-term-care-facilities-and-medicaid-0

- 51. Kaiser Family Foundation. A closer look at the final nursing facility rule and which facilities might meet new staffing requirements. 2024. Accessed May 19, 2024. https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/a-closer-look-at-the-final-nursing-facility-rule-and-which-facilities-might-meet-new-staffing-requirements/

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-inq-10.1177_00469580241292170 for Ownership Matters: Not-for-Profit Chain Nursing Homes Have Higher Utilization of Agency Nursing Staff by Rohit Pradhan, Akbar Ghiasi, Gregory Orewa, Shivani Gupta, Ganisher Davlyatov, Bradley Beauvais and Robert Weech-Maldonado in INQUIRY: The Journal of Health Care Organization, Provision, and Financing