Abstract

Multiple changes occur across various endocrine systems as an individual ages. The understanding of the factors that cause age-related changes and how they should be managed clinically is evolving. This statement reviews the current state of research in the growth hormone, adrenal, ovarian, testicular, and thyroid axes, as well as in osteoporosis, vitamin D deficiency, type 2 diabetes, and water metabolism, with a specific focus on older individuals. Each section describes the natural history and observational data in older individuals, available therapies, clinical trial data on efficacy and safety in older individuals, key points, and scientific gaps. The goal of this statement is to inform future research that refines prevention and treatment strategies in age-associated endocrine conditions, with the goal of improving the health of older individuals.

Keywords: adrenal, androgen, diabetes, endocrinology, estrogen, growth hormone, water metabolism, osteoporosis, thyroid, vitamin D

Hormones regulate and coordinate multiple physiologic functions. With increasing age, declines in physical and cognitive function occur. The extent to which age-associated changes in hormonal regulation and increases in prevalence of specific endocrine diseases contribute to declines in physical and cognitive function is incompletely understood. This area will only expand in importance as the number of older individuals increases worldwide. Current projections show an increase in those aged 65 years and older from 703 million (1 in 11 people) to 1.5 billion in 2050 (1 in 6 people) (1).

This Scientific Statement was developed to provide a high-level summary of the current state of research across multiple hormonal axes in aging and to identify areas in need of future research. Each section describes the natural history and observational data in older individuals, available therapies, clinical trial data on efficacy and safety in older individuals, key points, and scientific gaps. The extent to which hormonal changes with age are deemed “normal aging” vs “endocrine disease” can be arbitrary and depends in part on whether treatment is currently indicated. Four hypothalamic-pituitary axes are presented: growth hormone, adrenal, gonadal (divided into ovarian and testicular), and thyroid. These are followed by osteoporosis, vitamin D deficiency, diabetes, and water metabolism topics. Geroscience has emerged as a research approach examining biological mechanisms of aging and their interplay with comorbid disease. In the conclusion, cross-cutting themes of research areas in need of further investigation and the need for geroscience approaches are summarized.

Growth Hormone Axis

Natural History/Observational Data in Older Individuals

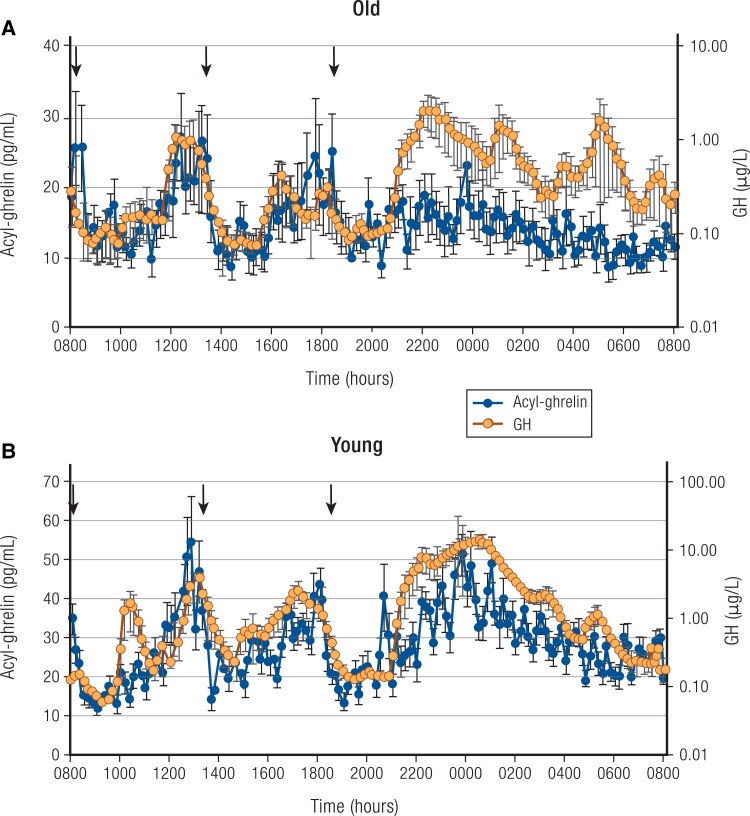

Growth hormone (GH) is secreted in a pulsatile fashion. Peak GH secretion occurs at mid-puberty (2), subsequently declining by 50% every 7 to 10 years. By the time the eighth decade is reached, GH levels are similar to those of GH-deficient young adults (3). Pulse frequency is similar across age, with approximately 18 secretory episodes of GH per 24 hours in children, younger adults, and older individuals (4). The decline in GH with aging is primarily seen in the amplitude of the secretory episodes, although interpulse levels also decline (Fig. 1) (5). A reduction of serum insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) levels occurs in parallel with the decline in average GH secretion in aging.

Figure 1.

24-hour mean (±SEM) profiles of acyl-ghrelin (left axis) and GH (right axis, note log scale) in 6 healthy older adults (A) and 8 healthy young men (B); young adults are included for comparison. Note different scales for old (upper panel) and young (lower panel) between groups. Arrows indicate standardized meals at 8:00 Am, 1:00 Pm, and 6:00 Pm. Subjects were allowed to sleep after 9:00 Pm. Also, note that in the older adults, GH was assayed in singlicates, which may contribute to some additional measurement variability in this group. Redrawn from Nass R et al (5). © Endocrine Society.

In premenopausal women, GH peak levels are higher than in men (6). This is likely due to reduced GH receptor sensitivity at the liver, and thus higher levels of GH are required to maintain normal serum IGF-1 levels. After menopause, GH levels are similar between women and men of similar age (6). Oral estrogen supplementation inhibits hepatic IGF-1 synthesis and increases GH secretion through reduced feedback inhibition, whereas IGF-1 levels increase and GH secretion is unchanged when estrogen is administered by the transdermal route (7-9).

The decline in GH synthesis and secretion with aging is well-documented in all mammalian species. In humans as well as other species, decreased output by the GH/IGF-1 axis is correlated with increased percentage of total body and visceral fat, decreased muscle mass, decreased physical fitness, decreased immune function, and physiological declines in estrogen and androgen concentrations. Whether this decline in GH secretion is causative or only correlative is controversial. In children and adults with GH deficiency, GH replacement has demonstrated benefits on body composition, serum lipids, fitness, and bone density; it also increases growth velocity in children. However, potential adverse effects of GH stimulation on malignancy, senescence, and telomere shortening are concerns of GH therapy in older individuals.

Controversy of whether GH deficiency extends life span

Caloric restriction and genetic alterations that reduce function in the GH/IGF-1/insulin pathways have been shown in experimental invertebrate and vertebrate animal models to extend life span. Mouse models of mutants that lack GH release (growth hormone-releasing hormone [GHRH], GHRH receptor, Prop1, and Pouf1) and that are GH insensitive (GHR) live significantly longer, and overexpression of GH reduces life span (bovine GH transgenic) (10). Whether this translates to humans is unclear. However, these are lifelong experiments and are likely not applicable to aging in humans in the Western world. This has also been recently reviewed in the context of humans with isolated GH deficiency (IGHD) type 1B, owing to a mutation of the GHRH receptor gene, in Itabaianinha County, Brazil. Individuals with IGHD are characterized by proportional short stature, doll facies, high-pitched voices, and central obesity. They have delayed puberty but are fertile and generally healthy. Moreover, these IGHD individuals are partially protected from cancer and some of the common effects of aging and can attain extreme longevity (10). In contrast, dwarfism associated with GH deficiency in patients with GH1 mutations is reported to significantly shorten median life span (11). There are studies that suggest that individuals with lower serum IGF-I levels have longer lives, potentially due to GH receptor exon 3 deletions (12), and that individuals with other GHR variants have major reductions in cancer and diabetes incidence without effects on life span (13). IGF-I receptor mutations have also been associated with longevity. In the Leiden Longevity Study, evidence has been presented that GH secretion is more tightly controlled in the offspring of long-lived families than in their partners, who served as age-matched controls (14).

Age, gender, percentage body fat, body fat mass, sleep disruption, aerobic fitness, and IGF-1 and gonadal steroid concentrations are all related to 24-hour GH release in adults. A major question is whether the decline of GH is due only to age or whether other factors are at play. It is well established that obesity, particularly increased visceral fat, is associated with reduced GH levels (15). In a study of highly and homogeneously active older male (n = 84) and female (n = 41) cyclists aged 55 to 79 years, it was shown that serum IGF-1 declined with age, while testosterone in men did not. The authors suggest that the hormonal changes of aging involve not only the aging process but also inactivity (16).

Available Therapies

There are no approved therapies for reversing the age-associated decline of GH secretion. Recombinant human GH (rhGH) is approved in pediatric patients with disorders of growth failure or short stature and in adults with growth hormone deficiency or with HIV/AIDS wasting and cachexia. Both GHRH and GH secretagogues exist but are not approved for use as anti-aging agents.

Clinical Trial Data on Efficacy and Safety in Older Individuals

In 2007, Liu et al published a systematic review of clinical trials of rhGH vs placebo, with or without lifestyle interventions (17). A total of 220 healthy older participants were enrolled and followed for a combined 107 patient years. Mean treatment was 27 weeks at a mean dose of 14 ug/kg day. Small changes in body composition (reduction in fat mass [−2.1 kg (95% CI, −2.8 to −1.35 kg)] and increase in lean body mass [2.1 kg (CI, 1.3 to 2.9 kg)], greater in men than in women) were found at the expense of an increased rate of adverse events. These included soft tissue edema, arthralgias, carpal tunnel syndrome, and gynecomastia, as well as a higher onset of diabetes mellitus and impaired fasting glucose. The conclusion of this review was that rhGH cannot be recommended as an anti-aging therapy.

Two randomized, placebo-controlled studies of the GH secretagogues MK-677 and capromorelin in older individuals demonstrated that these oral agents increase GH levels by enhancing the amplitude of GH pulses to levels reported in young individuals (4, 18). These compounds also have the advantage that they cannot be overdosed, due to IGF-1 feedback. The major difference between the 2 studies was in the selection of participants. In the MK-0677 study, healthy individuals were studied, whereas in the capromorelin study, participants had mild functional impairment.

Sixty-five healthy adults ranging from 60 to 81 years of age were randomized to the GH secretagogue receptor agonist MK-677 to determine whether MK-677, an oral ghrelin mimetic, could increase growth hormone secretion into the young adult range without serious adverse effects, prevent the decline of fat-free mass, and decrease abdominal visceral fat compared with placebo (4). Over 12 months, MK-677 enhanced pulsatile growth hormone secretion and significantly increased fat-free mass vs placebo (1.1 kg [CI, 0.7 to 1.5 kg] vs −0.5 kg [95% CI, −1.1 to 0.2 kg]), but did not affect abdominal visceral fat, total fat mass, strength, or physical function. Body weight increased with an increase in appetite, mild lower-extremity edema, and muscle pain, along with small increases in fasting glucose and cortisol and a decrease in insulin sensitivity. Further development of this compound was not pursued.

A randomized trial with the GH secretagogue agonist capromorelin was conducted in 395 adults aged 65 to 84 years of age with mild functional limitation to investigate the hormonal, body composition, and physical performance effects as well as the safety of 4 capromorelin dosing groups vs placebo (18). Although the study was terminated early due to failure to meet predetermined treatment effect criteria, a sustained, dose-related rise in IGF-I concentrations occurred in all active treatment groups. At 6 months, body weight increased 1.4 kg in participants receiving capromorelin and decreased 0.2 kg in those receiving placebo (P = .006). Lean body mass increased 1.4 vs 0.3 kg (P = .001), and tandem walk improved by 0.9 seconds (P = .02) in the pooled treatment vs placebo groups. By 12 months, stair climb also improved (P = .04). Adverse events included fatigue, insomnia, and small increases in fasting glucose, glycated hemoglobin, and indices of insulin resistance. No additional studies are planned for this compound.

Key Points

At present, no therapy to increase GH secretion or action is approved as an anti-aging intervention.

Studies with rhGH and GH secretagogues failed to demonstrate benefits that outweigh risks. However, it is possible that benefit could be maximized with the use of lower doses, in study populations with worse physical function, and in combination with exercise and adequate nutrition, without the adverse effects seen in previous studies.

Gaps in the Research

Studies in invertebrate and vertebrate models are important but may not be translatable to humans. Most animal studies have investigated lifelong interventions of over- or underactive somatotroph function. Intervening at different stages of the life cycle may help explain the conflicting data on whether too little or too much somatotroph function may be beneficial to extending life span.

The changes in GH secretion across the life cycle make the interpretation of animal studies and their translation to humans problematic. The objective should be to improve health span rather than life span. Thus, further studies of increasing or decreasing somatotrope function at different stages of the life cycle will be important, particularly to evaluate whether restoring pulsatile GH secretion as seen in 20- to 30-year-old individuals would help prevent development of frailty and sarcopenia without increasing risks. It is clear that hormonal treatment alone will not be sufficient, so future trials will require evaluation of lower doses of GH/GH secretagogues with consideration of combination with exercise, nutrition interventions, and/or co-supplementation of other hormones (eg, testosterone). Targeting the right populations, such as those who have developed, or are at high risk for, frailty and sarcopenia, will also be vital. Further studies will need to be carried out for several years or longer.

Adrenal Axis

Natural History/Observational Data in Older Individuals

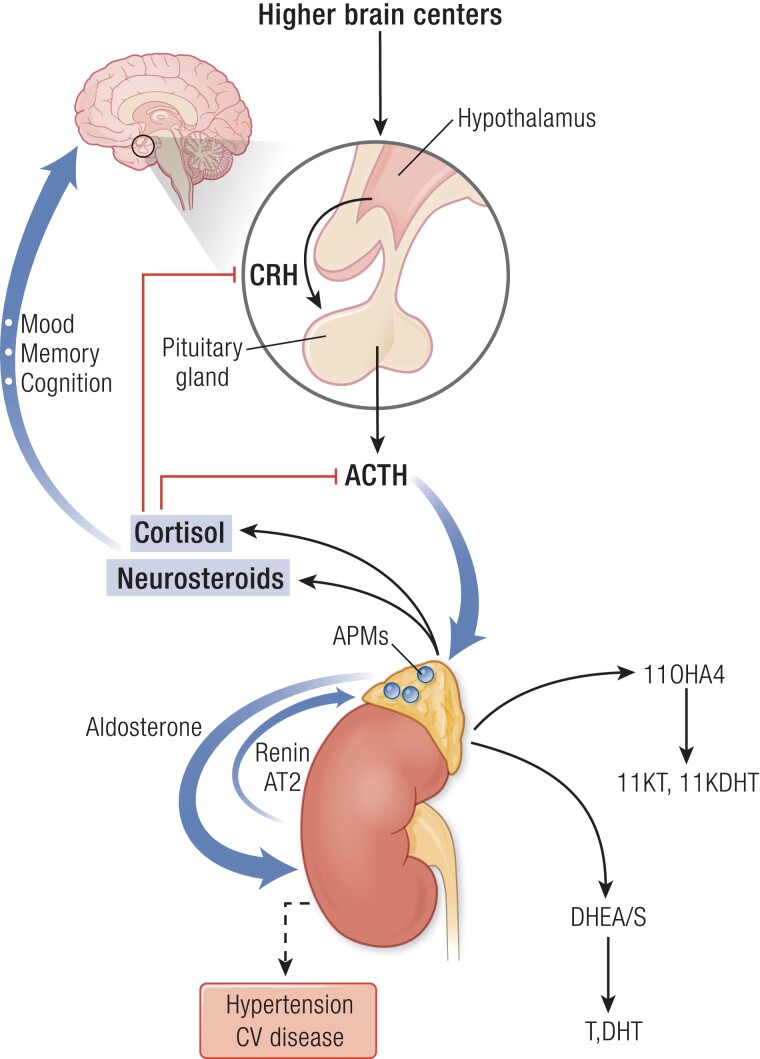

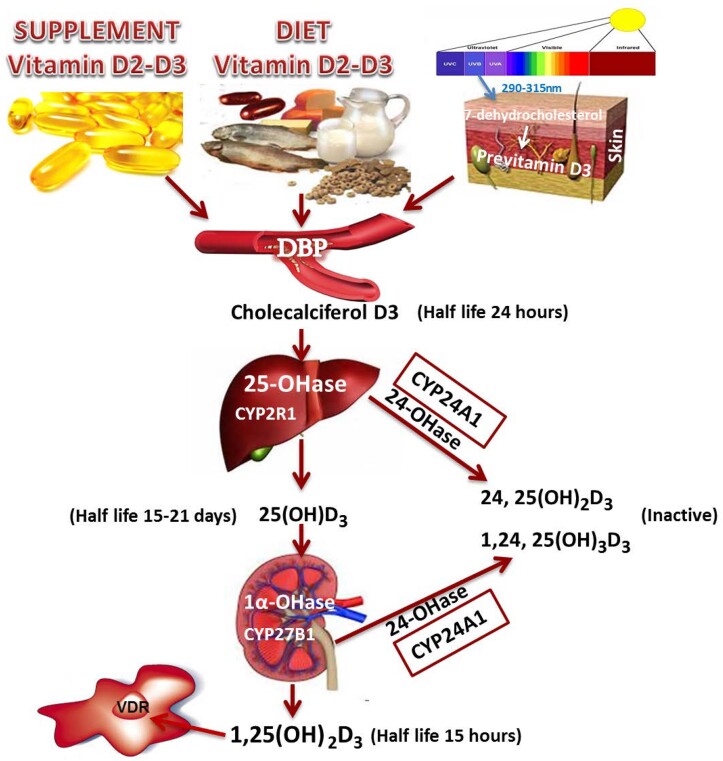

The adrenal glands produce several classes of hormones from different cell types or zones. The adrenal cortex synthesizes steroid hormones and hormone precursors, primarily the mineralocorticoid aldosterone from the zona glomerulosa, the glucocorticoid cortisol from the zona fasciculata, and the androgen precursors dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) and its sulfate (DHEAS) from the zona reticularis (19) (Fig. 2). DHEAS is largely a storage form and excreted product, with conversion to DHEA in a few tissues. The adrenal medulla is an extension of the sympathetic nervous system, which secretes epinephrine.

Figure 2.

The hypothalamus integrates signals from the environment and higher brain centers to release corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH), which stimulates pituitary production of adrenocorticotropin (ACTH). ACTH drives production of cortisol, as well as neurosteroids and their precursors, 11β-hydroxyandrostenedione (11OHA4), and dehydroepiandrosterone and its sulfate (DHEA[S]). Cortisol provides negative feedback (red lines) to the hypothalamus and pituitary, not just to cortisol but also to all other ACTH-stimulated steroids. DHEA and DHEAS can be metabolized to the androgens testosterone and dihydrotestosterone (T, DHT), whereas 11OHA4 is metabolized to the androgens 11-ketotestosterone (11KT) and 11-ketodihydrotestosterone (11KDHT). Cortisol and neurosteroids exert important actions on the brain that control mood, memory, and cognition. Independently, aldosterone is produced under the renin-angiotensin 2 (AT2) system, or autonomously such as from aldosterone-producing micronodules (APMs). Aldosterone regulates sodium balance, and aldosterone excess causes hypertension and cardiovascular (CV) disease. In aging, cortisol negative feedback is attenuated, and while DHEAS production falls, cortisol and 11OHA4 synthesis is preserved. APMs increase with age, and the potential deleterious effects of cortisol and aldosterone excess are magnified with aging.

Infants produce large amounts of aldosterone to compensate for the resistance of the neonatal kidney to mineralocorticoids and the low sodium content of human milk. Over time, the sodium content of the diet increases, and the need for aldosterone decreases; most American adults consume over 150 meq of sodium daily. Rather than having a uniform, continuous zona glomerulosa as seen in children and young adults, adrenal glands of adults in Western countries become increasingly discontinuous after age 40. Immunohistochemistry studies reveal pockets of cells that express the aldosterone synthase enzyme (CYP11B2) beneath the adrenal capsule (20), initially termed aldosterone-producing cell clusters and now called aldosterone-producing micronodules (APMs). APM cells commonly harbor somatic mutations in genes encoding subunits of ion channels that regulate aldosterone production (21). As the number of adrenal glands with a continuous zona glomerulosa declines with age, the number of these APMs and their total area increases in parallel (22). A theoretical, but plausible, interpretation of these findings is that, with a chronic high-salt diet and renin suppression, the normal zona glomerulosa atrophies. At the same time, adrenal precursor cells undergo selection for clones with somatic mutations in ion channel genes that allow survival and aldosterone production in the absence of angiotensin II stimulation (23). This process could give rise to the cells that proliferate into APMs. The accumulation of APMs translates to various degrees of autonomous aldosterone production, and if the burden becomes high enough, could result in unilateral or bilateral primary aldosteronism. Other subclones might undergo further genetic changes that drive formation of aldosterone-producing adenomas. This model could explain the development of various forms of primary aldosteronism and why the prevalence of this disease and of salt-sensitive hypertension increases with age.

Like that of other axes, the dynamic behavior of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis undergoes changes with age, including a flattening of the diurnal rhythm and earlier morning peak (24, 25). This results in higher 24-hour cortisol production rates and free cortisol levels, but no difference in cortisol binding globulin levels, with increasing age (26). In addition, the HPA axis appears to be more responsive to stress, with some differences between men and women (27), in part due to reduced negative feedback inhibition from cortisol (28). Similarly, the cortisol response to exogenous adrenocorticotropin (ACTH) is prolonged at older ages (29). Given the potential contributions of cortisol to a multitude of age-dependent diseases and decline in physical function, these changes and individual variations in magnitude could have broad consequences (30).

Regulation of local glucocorticoid activity, independent of the HPA axis, may occur with cortisol regeneration from cortisone via the enzyme 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1 (11βHSD1). The expression of 11βHSD1 in skin increases with age (31), which could potentiate the catabolic action of cortisol on skin without affecting adrenal cortisol production. 11βHSD1 expression in muscle is inversely correlated with strength in older individuals (32), suggesting that, in aging, enhanced catabolic action of cortisol could occur through this mechanism in several tissues.

The prevalence of overt Cushing syndrome does not rise with age, but the development of mild ACTH-independent hypercortisolemia due to adrenal adenomas and hyperplasia does increase over time (33). Several studies have provided evidence that even mild cortisol excess is not benign and is associated with hypertension, glucose intolerance, cardiovascular events, and vertebral fractures (34, 35). Consequently, occult and smoldering hypercortisolemia could predispose to common disorders in older persons.

Furthermore, although cortisol does not directly cause major age-related diseases, such as cancer and dementia, preclinical and human studies suggest that modulation of cortisol action could evolve into treatment strategies for these diseases. In castration-resistant prostate cancer, sustained treatment with the potent androgen-receptor antagonist enzalutamide results in upregulation of glucocorticoid-receptor expression, which drives the expression of previously androgen-regulated oncogenes (36). In parallel, rapid degradation of 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 2, the enzyme that converts cortisol to inactive cortisone, potentiates cortisol action (37). Consequently, the glucocorticoid signaling pathway could be a target for the treatment of advanced prostate cancer (38). In patients with early Alzheimer disease, higher morning plasma cortisol predicts more rapid progression of dementia symptoms and deterioration of temporal lobe function (39). In a rat model, glucocorticoid-receptor antagonists attenuated the augmented rise in morning corticosterone and hippocampal amyloid deposition, and some agents delayed the progression of cognitive dysfunction (40). These studies demonstrate that manipulation of cortisol bioactivity, particularly in a tissue-selective manner, could have benefits in certain maladies common in older individuals.

Circulating concentrations of DHEAS peak at about age 25 and then decline gradually with age, falling to childhood concentrations by age 80 in most adults (41), reflecting a gradual reduction in the size of the zona reticularis (42). The reason for this change is not known, and rodents secrete small amounts of DHEA and therefore cannot serve as a research model for this hormone. The peak concentrations and trajectory of decline, however, vary significantly among individuals, and in population studies, DHEAS concentrations are higher in men than women. The developmental changes and age-related decline in DHEAS have attracted considerable attention as a potential mediator of the aging process (43), reflecting the anabolic actions of androgens.

In women, half or more of circulating testosterone derives from 19-carbon androgen precursors from the adrenal cortex, including DHEA, DHEAS, and androstenedione (44). In contrast, the vast majority of testosterone in men derives from the testes throughout adult life. Consequently, an age-related decline in steroid production from the zona reticularis could have greater impact in women and in men with primary or secondary testicular dysfunction than in normal men. While the decline in DHEAS with age is well substantiated, many of the data about the consequences of this phenomenon derive from epidemiologic and cross-sectional studies (45, 46), rather than large randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of DHEA supplementation.

Another product of the adrenal cortex that has been understudied until recently is the robust synthesis of 11-oxygenated androgens, primarily 11β-hydroxyandrostenedione (11OHA4), which is converted through metabolism in other tissues to the androgen 11-ketotestosterone (11KT) (47). While the biosynthetic pathways of 11-oxygenated pro-androgen production via the human adrenal cortex have been described, the location(s) of their synthesis, the zona fasciculata and/or zona reticularis, is not known. In women, DHEA, DHEAS, androstenedione, and testosterone all decline from age 30 onward; however, 11OHA4 and 11KT increase slightly into the ninth decade and decline only slightly during this age window in men (48). For nearly all women (48) and prepubertal children (49), 11KT is the most abundant bioactive androgen in the circulation, and this adrenal androgen component is preserved throughout life. Because 11KT could theoretically provide negative feedback on the gonadal axes, this contribution could become important in older men, although direct evidence to this effect is lacking.

Available Therapies

Spironolactone and eplerenone, and more recently, finerenone, are available as aldosterone (mineralocorticoid) antagonists for the treatment of primary aldosteronism and hypertension. Although the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved several treatments for Cushing syndrome (mifepristone, pasireotide, osilodrostat, and levoketoconazole) in recent years, these drugs are not well-studied for subtle ACTH-independent hypercortisolemia or the cortisol-mediated contributions to other diseases. DHEA (prasterone) administered as a 6.5 mg intravaginal insert improves symptoms of vulvovaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women and is FDA-approved for this purpose (50). DHEA is available over the counter as a dietary supplement and is not regulated by the FDA.

Clinical Trial Data on Efficacy and Safety in Older Individuals

Small studies have found conflicting results from DHEA replacement in older women (51-53). A few moderately large studies of DHEA supplementation at 25 to 50 mg/d for 1 or 2 years in older men and women have consistently shown restoration of DHEAS concentrations to the young adult range, as well as increased circulating concentrations of testosterone in women and of estradiol in postmenopausal women (54, 55). In these trials, postmenopausal women experienced small improvements in bone density at some sites, and these changes could be ascribed to the rise in estradiol. In one of these studies, no improvement of muscle cross-sectional area or strength was observed (56), and improvements in quality of life could not be demonstrated (55). These studies do not support the widespread use of DHEA supplementation as an anti-aging agent, despite claims otherwise to be found on the internet. Some studies of DHEA supplementation in women with adrenal insufficiency, in whom production of DHEA, DHEAS, testosterone, and all adrenal-derived androgens is low, have reported improvements in sexual satisfaction and interest (57), but similar results have not been obtained in trials with older women.

Key Points

APMs that autonomously produce aldosterone begin to develop in adulthood and accumulate with age.

The HPA axis shows less sensitivity to negative feedback, blunted diurnal changes, and alterations in cortisol/cortisone interconversion with aging.

Although circulating concentrations of DHEA and DHEAS decline with age, cortisol and 11-keto androgens do not decline or rise slightly.

Modulation of cortisol signaling could be beneficial in a host of diseases that become more common in older men and women.

Systemic DHEA supplementation has not shown major benefits in older individuals.

Gaps in the Research

Because rodent adrenals make neither cortisol nor androgens due to lack of the gene Cyp17, engineered or humanized strains that include Cyp17 and recapitulate the zonation and steroidogenic repertoire of the human adrenal would be valuable animal models to study human aging and targeted interventions.

Additional research is needed to chart the development of APMs in aging adrenals and to define the role of autonomous aldosterone production in the age-associated increase of salt-sensitive hypertension. Incorporation of cortisol modulation, including tissue-selective agonists and antagonists, into treatment regimens for diseases from cancer to Alzheimer disease is only beginning to emerge. Previous conclusions regarding adrenal androgens during aging, including 11-oxygenated androgens, need to be reassessed using modern mass spectrometry–based steroid profiling. Studies designed to dissect the contributions of adrenal steroids to the aging process using longitudinal cohorts would add to the understanding of whether these changes are detrimental, compensatory, or clinically insignificant.

Ovarian Axis

Natural History/Observational Data in Older Individuals

Biology of menopause/ovarian aging

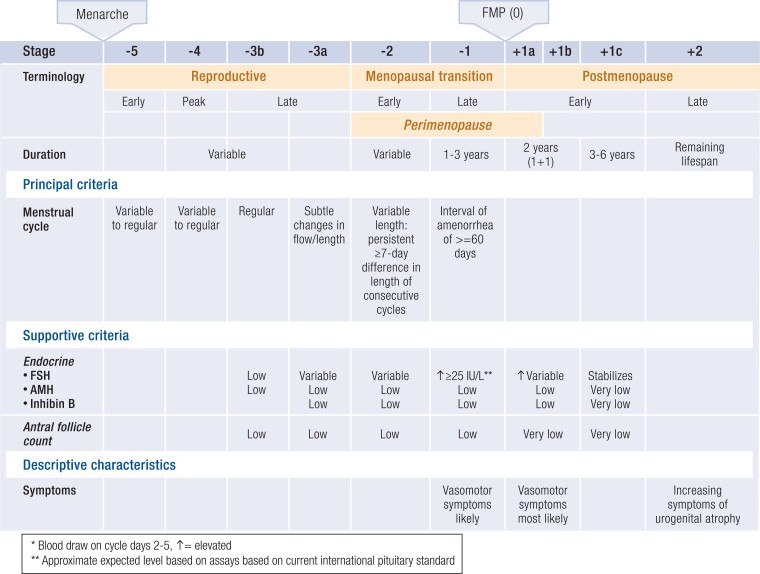

In contrast to other endocrine axes, aging of the human ovary is programmed—before birth—for midlife senescence. A full complement of ovarian follicles develops in utero, peaking at approximately 7 months of gestation with 6 to 7 million follicles, and then, via atresia, is gradually reduced to 1 to 2 million follicles by birth. The progressive decline in ovarian follicle number follows a curvilinear pattern, with accelerated loss with increasing age (58). Menopause, the final menstrual period, is diagnosed retrospectively after 12 months of amenorrhea, at an average age of 51 years, when total follicles number approximately 1000 (Fig. 3) (59).

Figure 3.

The Staging of Reproductive Aging Workshop (STRAW)+10 staging system for reproductive aging in women. Abbreviations: AMH, anti-Mullerian hormone; FMP, final menstrual period; FSH, follicle-stimulating hormone. Redrawn from Harlow SD et al (59). © Endocrine Society.

The average human reproductive life span, ranging from menarche to menopause, is currently estimated at 37 years in duration (60). Genetic, autoimmune, metabolic, environmental, and iatrogenic factors can accelerate follicular atresia resulting in early (40 to 45 years) or premature (<40 years) menopause (61). The progression of ovarian aging can be monitored by measurement of anti-Mullerian hormone (AMH) and ultrasound determination of antral follicle count (AFC) (62, 63). These parameters are useful for determining ovarian reserve and timing of menopause, but paradoxically, do not necessarily correlate with fertility, likely due to the multiple other factors influencing female fertility. By the time follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) increases during the late menopausal transition, AMH levels are low to undetectable.

Genetic contributions to age of menopause

Population-based genome-wide association studies have identified 290 genomic loci associated with age of natural menopause (64). The loci identified harbor a broad range of DNA damage-response processes, highlighting the importance of these pathways in determining ovarian reserve (64). Additional factors include cohesion deterioration and chromosome mis-segregation, meiotic recombination errors, spindle assembly checkpoint, genetic mutations, telomere length and telomerase activity, reactive oxygen species, mitochondrial dysfunction, and ovarian fibrosis and inflammation (65, 66). The inability to repair DNA damage in both somatic and germ cells could explain the link between reproductive and overall aging (67).

The “epigenetic clock,” based on DNA methylation levels, provides more evidence that menopause accelerates at least some components of biological aging (68). Conversely, increased epigenetic age acceleration in blood is significantly associated with earlier menopause, bilateral oophorectomy, and a longer time since menopause (68). Furthermore, the age at menopause and epigenetic age acceleration share common genetic origins (68). The telomerase reverse transcriptase gene provides critical regulation of the epigenetic clock (69).

Hypothalamic-pituitary contributions to ovarian aging

In spite of the primary focus on the ovary as the key determinant of reproductive senescence, the central nervous system has been explored as a critical pacemaker of reproductive aging with evidence that central changes (70-72), regulated by DNA methylation (73), contribute to the timing of menopause. Manifestations of aging on gonadotropin secretion include diminution of the preovulatory luteinizing hormone (LH) surge (74) and marked elevation of pituitary LH and FSH during the late reproductive phase and the menopause transition. Diminished pituitary responsiveness to gonadotrophin-releasing hormone (GnRH) after menopause (75) is accompanied by alterations in the forms of secreted LH and FSH, resulting in slower clearance and prolonged half-life (76). Pituitary-ovarian axis hormones—particularly FSH and estradiol—are also hypothesized to play a role in regulating ovarian mitochondrial activity (77, 78). Elucidation of hypothalamic kisspeptin, neurokinin B, and dynorphin neuronal morphology and physiology in postmenopausal women provides insights regarding postmenopausal gonadotropin control and a new mechanism to reduce vasomotor symptoms (VMS) with NK3R (neurokinin3 receptor) antagonists (79-81).

Challenges to traditional thinking about the postmenopausal effects of elevated FSH have emerged. Mouse studies utilizing a blocking antibody to the FSH receptor revealed preservation of bone density (82), subsequent browning of white fat cells, decrease in subcutaneous and visceral fat accumulation, and improved muscle mass (83, 84), although contrary evidence of bone anabolic effects of FSH, mediated through the ovary, has also been reported (85). Possible links of FSH with cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk have been proposed. However, in the Study of Women Across the Nation (SWAN), a multiethnic cohort of US women, higher FSH also predicted lower systolic blood pressure (86).

Ovarian steroid hormone status with aging

Estradiol secretion is maintained in older, reproductive aged women by increased ovarian aromatase function (87, 88). Granulosa cell production of estradiol, AMH, and inhibin eventually declines with age, possibly reflecting progressive mitochondrial aging (89). In the postmenopausal state, estrogen synthesis continues, but at much lower levels, via aromatase conversion of ovarian androstenedione to estrone, the predominant postmenopausal estrogen, and of testosterone to estradiol. Obesity, with an attendant increase in aromatase activity, is associated with higher serum concentrations of estrogens and testosterone (90, 91).

Circulating testosterone concentration within the low female range declines with reproductive aging (92-94). Ovarian testosterone production falls in a linear pattern with age; in longitudinal studies, testosterone levels were not directly affected by menopause. The theca cells of the postmenopausal ovary continue to produce testosterone in response to elevated gonadotropins. With advancing age, to 70 (93, 94) to 80 years (93-95), higher testosterone concentrations are associated with detrimental metabolic and cardiovascular effects (96) yet increased bone mineral density (BMD) and lean body mass (91).

Clinical aspects of ovarian aging

Regardless of the etiology of ovarian insufficiency, 2 key clinical sequelae arise: a progressive decline in fertility, reflecting the reduction in ovarian follicle number and quality, and the cessation of monthly menstrual cycles, reflecting the parallel decline of ovarian steroid hormones. Consequently, symptoms (VMS, genitourinary syndrome of menopause [GSM] (97), disordered mood, sleep disruption, sexual disorders) and systemic effects (amenorrhea, bone loss, metabolic syndrome, increased cardiovascular risk, cognitive decline) can result (98).

The menopause transition

The updated Stages of Reproductive Aging Workshop (STRAW+10) report provides standardized criteria for identifying the transition from the reproductive years to the postmenopausal, with the goal of enhancing the design and reporting of research studies of ovarian aging while establishing accepted nomenclature to be applied to patient care (59) (Fig. 3). Prospective, longitudinal observational studies (99-104) (Table 1), such as SWAN (104), continue to clarify the timing of perimenopausal symptom onset, duration during and beyond the menopause transition, relationship with pituitary and ovarian hormone concentrations, clinical correlations with race and ethnicity, linkage of multiple perimenopausal symptoms, and association of symptoms with chronic diseases previously solely attributed to aging.

Table 1.

Prospective longitudinal studies of the menopausal transition

| Study name | N | Age at baseline (y) | Dates | Duration (y) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| The Massachusetts Women's Health Study (99) | 2570 | 45-55 | 1981-1986 | 5 |

| The Melbourne Women's Midlife Health Project (100) | 438 | 45-55 | 1996-2005 | 9 |

| Penn Ovarian Aging Study (101) | 436 | 35-47 | 1996-2014 | 18 |

| The Seattle Midlife Women's Health Study (102) | 508 | 35-55 | 1990-2013 | 23 |

| University of Pittsburgh Healthy Women Study (103) | 532 | 42-50 | 1983-2008 | 25 |

| Study of Women's Health Across the Nation (104) | 3302 | 40-55 | 1994-ongoing | 28 |

Clinical sequelae of ovarian aging

Ovarian aging is associated with deteriorating lipid profiles; accelerated cardiovascular risk; adverse changes in body composition including distribution of adipose tissue; accelerated lumbar spine BMD loss; and negative effects on sleep, cognition, and mood (105, 106). Early (< age 45 years) and premature (< age 40 years) menopause (natural or surgical) appear to accelerate chronic diseases of aging, including type 2 diabetes, illustrated by studies of women experiencing bilateral oophorectomy before age 46 (107, 108). A truncated “reproductive life span” is associated with higher risk of CVD events and mortality (109). Alternatively, cardiovascular health has been hypothesized by some to contribute to the timing of menopause, so a bidirectional association could be considered (105, 110).

Vasomotor symptoms and cardiovascular risk

Reports from longitudinal, prospective studies provide compelling evidence that for approximately a quarter of women, VMS start more than a decade prior to menopause and last more than a dozen years after (111-113). Long-term SWAN follow-up showed an association between frequency of VMS and increased CVD risk factors, subclinical CVD, and CVD events (113, 114). Ongoing studies will examine whether this association reflects causation and if treating VMS modifies CVD risk.

Observations of VMS with increasing age

Observational studies and clinical trials with participants of advanced age suggest that approximately 7% of older women continue to experience VMS (115). Whether VMS persist from the time of menopause, recur after a period of quiescence, or arise de novo decades later has not been ascertained. The complex interplay between VMS and a 5- to 9-fold increase of CVD events following menopausal hormone therapy (MHT) initiation in older women participating in the Heart and Estrogen/progestin Replacement Study (HERS) (116) and the Women's Health Initiative (WHI) (117) underscores the need for more research into the etiology, characteristics, and consequences of VMS with aging.

Available Therapies

The spectrum of evidence-based therapies for relief of VMS ranges from MHT to prescription nonhormonal drugs to mind-brain-behavioral approaches, including cognitive behavioral therapy and hypnosis (118, 119). Decisions regarding the optimal choice for an individual woman incorporate her degree of symptom bother, personal preferences, CVD and breast cancer risk assessments, and uterine status (118, 120, 121). Treatment of GSM includes over-the-counter moisturizers and lubricants, vaginal estrogens, DHEA, and oral ospemifene (97, 118). As no testosterone preparation is approved by the FDA for women, titration of approved therapies dosed for men has been recommended for treatment of hypoactive sexual desire disorders in women (122, 123).

Clinical Trial Data on Efficacy and Safety in Older Individuals

For this discussion, “older” encompasses women after menopause (usually > age 50), bearing in mind that hormone replacement therapy is indicated for younger women who experience hypogonadism or primary ovarian insufficiency and is recommended until the anticipated age of natural menopause (61, 118, 120). Although preparations, routes of administration, and dosages of MHT have markedly expanded since the first use of conjugated equine estrogens (CEE) in the 1940s, the primary indication for MHT in women experiencing natural menopause remains treatment of symptoms (VMS and GSM) (118, 120). Prevention of osteoporosis is another approved indication of MHT, for postmenopausal women at significant risk of osteoporosis for whom other approved therapies are neither tolerated nor appropriate. Additional preventive indications have been considered and are currently under review (124).

The results of secondary coronary heart disease (CHD) prevention trials have been disappointing (125). In contrast to anticipated CHD benefit based upon myriad observational studies, trials revealed an increase in myocardial infarction within the first year of therapy, and failure to reduce CHD events or coronary atherosclerosis progression (125).

The Women’s Health Initiative clinical trials were initiated in 1992 to determine whether MHT (CEE ± medroxyprogesterone acetate ([MPA]), depending upon uterine status), when started in healthy women ages 50 to 79 at enrollment, reduced the incidence of chronic diseases of aging (myocardial infarction and CHD death, osteoporosis, colon cancer) while evaluating safety outcomes (stroke, venous thromboembolic disease, breast and endometrial cancer) (126). The combined therapy arm was halted after 5.6 years, and the estrogen-only arm after 7.2 years, because overall risks (increased stroke in both trials and heart attack, pulmonary emboli, and breast cancer in the combined arm) exceeded preventive benefits (reduced fractures, colon cancer, diabetes) (117). Subsequent analyses showed a more favorable benefit/risk profile in younger women (ages 50 to 59) or those closer (<10 years) to menopause, whereas stroke risk increased when MHT was initiated > age 60 (127), dementia risk increased > age 65 (126), and CHD events increased > age 70 (127). The 13-year cumulative follow-up provided additional supportive evidence (117). At 18 years, overall mortality was not increased for any group. Moreover, all-cause mortality decreased by 21% in those ages 50 to 59 at enrollment in the CEE-alone arm (128), with maximal mortality benefit—a 40% decrease—for those with bilateral oophorectomy < age 45 (108).

Breast cancer outcomes at 13 years of cumulative follow-up showed persistence of the significant 28% increase in breast cancer risk with combined therapy initially reported at trial termination (117). In contrast, a 21% decrease with CEE alone became statistically significant (117). At 20 years of cumulative follow-up, these findings persisted, with the added caveat that breast cancer mortality—without effect in the combined therapy arm—was significantly reduced in the CEE-alone arm (129). These findings reflect the complexities of these specific hormone preparations on breast cancer incidence and mortality and should not be extrapolated to other MHT preparations. Although adequately powered RCTs are lacking, observational studies do not suggest that estradiol administration inhibits breast cancer, whereas progesterone may have less breast cancer–stimulating effects than MPA (118). The paucity of RCT safety evidence means that MHT is usually not prescribed for women with a history of breast cancer; symptom relief with nonhormonal options is recommended (118, 130).

In summary, the Women’s Health Initiative established the safety of MHT for younger postmenopausal women (< age 60 or <10 years since menopause), highlighted the divergence of CVD and breast cancer outcomes for CEE alone vs combined therapy with MPA, and confirmed observational studies suggesting mortality benefit for women with early menopause who used CEE alone following oophorectomy.

The timing hypothesis

The timing hypothesis suggests that MHT reduces atherosclerosis when initiated close to menopause, but not if started at a later point, possibly due to changes in estrogen receptor signaling with time since menopause and altered estrogen milieu (131, 132). The timing hypothesis could also explain findings from a trial evaluating effects of transdermal estradiol on insulin sensitivity (133). Several RCTs designed specifically to examine the CHD effects of the timing hypothesis yielded inconsistent results (117, 134-136) (Table 2). Current guidelines recommend against prescribing MHT solely for CHD prevention in naturally postmenopausal women (118, 120, 124, 137).

Table 2.

Randomized primary prevention trials evaluating effects of menopausal hormone therapy on clinical and surrogate cardiovascular outcomes in healthy, recently postmenopausal women

| Trial | MHT preparation and dose | N | Age (y) | Duration (y) | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical outcomes | |||||

| WHI E-alone (117) | CEE 0.625 mg/d po | 3313 | 50-59 | 7.2 | Reduced MI, CAC, and revascularization |

| WHI E + P (117) | CEE 0.625 mg/d and MPA 2.5 mg/d po | 5520 | 50-59 | 5.6 | No benefit |

| DOPS (134) | 17-B E2 2 mg/day and norethisterone acetate 1 mg 10 days/mo po | 1006 | 45-58 | 10 | Reduced composite serious adverse events: death, hospitalized MI, or CHF |

| Surrogate outcomes | |||||

| KEEPS (135) | CEE 0.45 mg/d po or TD E2 50 mcg and progesterone 200 mg 12 days/mo po | 727 | 42-58 | 4 | No benefit cIMT or CAC |

| ELITE (136) | 17-B E2 1 mg/d po and progesterone 45 mg vaginal gel 10 days/mo | 596 | 55-64 | 5 | Reduced cIMT early group No benefit CAC |

Early <6 years since menopause vs late ≥10 years since menopause.

Abbreviations: CAC, coronary artery calcium; CEE, conjugated equine estrogens; CHF, congestive heart failure; cIMT, carotid intima-medial thickness; DOPS, Danish Osteoporosis Prevention Study (randomized, not blinded); E2, estradiol; E-alone, estrogen alone trial; E + P, estrogen plus progestogen; ELITE, Early vs Late Postmenopausal Treatment with Estradiol; KEEPS, Kronos Early Estrogen Prevention Study; MHT, menopausal hormone therapy; MI, myocardial infarction; MPA, medroxyprogesterone acetate; po, oral; TD, transdermal; WHI, Women's Health Initiative; y, years.

Dose/type of MHT and duration of therapy

In the absence of adequately powered clinical trials, observational studies and meta-analyses provide some evidence that safety outcomes—particularly for venous thromboembolic disease and possibly stroke risks—are improved with lower doses and transdermal estradiol preparations (105, 118, 138).

Following the initial reports of the Women’s Health Initiative, limiting MHT to 3 to 5 years was recommended to minimize breast cancer risk. Both the North American Menopause Society (NAMS) and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) subsequently issued statements allowing for longer duration of MHT in healthy women ≥ age 65 without contraindications, following an annual discussion of anticipated risks and benefits, and reevaluation of individual health status (120, 139). The recommendation for shared decision making reflects the absence of long-term evidence to inform decisions regarding risks and benefits for women who initiate MHT for symptom relief at menopause and continue for an extended time. Common sense measures include progressively reducing the dose and switching to transdermal from oral preparations (115, 118, 120).

Key Points

Menopause and the postmenopausal state are natural, preprogrammed manifestations of ovarian aging characterized by fertility loss and profound reduction in ovarian hormone production.

Menopausal symptoms are common, vary in degree of bother, and can be effectively treated with a variety of agents proven effective in RCTs.

Initiation of MHT is safest when reserved for women in close proximity (<10 years) to the menopause transition or less than age 60, without contraindications, and with acceptable CVD and breast cancer risks.

Continuation of MHT can be considered individually depending on personal desires, health status, and documented shared decision making.

Although oral MHT has been studied most extensively, depending upon health status and age, based upon prospective observational studies, lower doses and transdermal therapies may be safer with fewer venous thromboembolic events, fewer undesirable metabolic effects, and possibly fewer CVD events.

Delineation of the physiological role of the kisspeptin, neurokinin Y, and dynorphin neurons in control of VMS and gonadotropin and sex steroid secretion allows for potential new treatment options as demonstrated in completed and ongoing RCTs of neurokinin3 receptor (NK3R) antagonists.

Gaps in the Research

Factors that affect the timing and consequences of menopause across diverse races, ethnicities, lifestyles, genetics, environmental influences, metabolic factors, and polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) require additional study. The SWAN study provides some insight into differences in reproductive aging and midlife health between Black and White women, but additional work is needed (140).

The natural history and physiologic characteristics of VMS, including the prevalence of ongoing or recurrent VMS in older women, CVD impact of VMS, and safe and effective treatment options in this age group, require more study, optimally utilizing investigative techniques measuring both subjective and objective VMS.

Steroid hormone and gonadotropin concentrations with advanced age have not been well delineated. Additional follow-up of ongoing studies such as SWAN and new population studies is needed.

Adequately powered RCTs with clinical outcomes of MHT would ideally be completed in symptomatic, recently postmenopausal women. Head-to-head randomized trials in this population could confirm risks and benefits of transdermal estradiol and micronized progesterone vs oral estrogen therapies and synthetic progestins.

Further study of selective estrogen receptor modulator (SERM) therapies alone or in combination (eg, CEE with bazedoxifene) could expand therapeutic and preventive strategies for aging women for whom available estrogen and progestogen therapies may no longer be tolerated or appropriate. The impact of FSH-blocking agents on bone health and other outcomes should be examined.

Novel investigational techniques proposed to preserve or revitalize ovarian function—derivation of oocytes from stem cells (141); ovarian transplantation of mesenchymal stem cells from amniotic membrane, umbilical cord, placenta, human menstrual blood, adipose tissue, and bone marrow; intra-ovarian injection of autologous platelet-rich plasma; and in vitro activation of dormant primordial follicles (142)—merit additional study. Investigational approaches to maintain “ovarian fitness” and promote reproductive longevity include dietary restriction, rapamycin, metformin, resveratrol, and melatonin administration (143, 144).

Testicular Axis

Natural History/Observational Data in Older Individuals

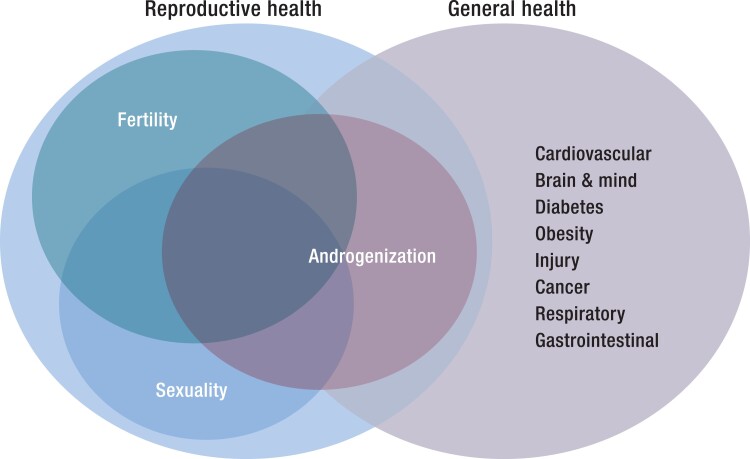

The 3 key dimensions of male reproductive health—fertility, sexuality, and androgenization—all interact with male general health, with the largest overlap with androgenization (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Overlap of the 3 dimensions of men's reproductive health—fertility, sexuality and androgenization—with general health. There is overlap of all dimensions but greatest for androgenization.

Biology of testicular aging

The twin functions of the testis—spermatogenesis to produce spermatozoa that can fertilize an oocyte and steroidogenesis to produce the bioactive androgens testosterone and dihydrotestosterone—are both impacted by aging, with effects mediated mainly by accumulation of aging comorbidities rather than aging itself. Hence, reproductive function of the healthiest of men remains largely undiminished throughout life, unless disrupted by intercurrent disease, a natural history differing starkly from female reproductive aging where an intrinsic, abrupt loss of ovarian function occurs at the midpoint of life for modern women.

Testosterone is necessary for reproduction (to make and deliver sperm) but not for life itself (as complete androgen insensitivity resulting from a genetic defect in XY individuals allows for a healthy but infertile life as a phenotypic woman). Uniquely among major human hormones, there is no naturally occurring excess testosterone syndrome in men, possibly reflecting the evolutionary role of the dramatic surge in androgens during male puberty required for species propagation. Testosterone is produced by all steroidogenic organs (testis, ovary, adrenal, placenta) and, while present in the circulation of all humans, blood testosterone displays a marked sexual dichotomy, with testicular secretion of 20 times more testosterone after puberty than is produced from non-testicular sources in children and women.

Male fertility

Paternity requires producing mature, fertile spermatozoa that are delivered by male sexual function to the female reproductive tract. After spermatogenesis is initiated at puberty, it is minimally affected by aging unless impacted by gonadotoxic chemicals or ionizing radiation (to which it is exquisitely sensitive) or severe withdrawal of gonadotropin drive essential to maintain the intratesticular androgen milieu required for completion of meiosis. Hence, on average the fertility of older men, either naturally or via in vitro fertilization, is only modestly diminished by reduced sperm output and motility (145, 146) so that paternity at advanced age is well known (147). However, unexplained impairment of sperm production in otherwise healthy men, the most frequent cause of male infertility, remains an important research challenge for both younger and older men (148). Modern genetics has still more to reveal about the heritable origins of spermatogenic failure and sperm (dys)function through genetic (149) and epigenetic (150, 151) mechanisms. Insight into acquired (nongenetic) causes of reproductive failure has, however, advanced only minimally. Data have been inconclusive about whether there is a secular trend for diminished human sperm production (152), due to potential bias from low participation of healthy, non-infertile men (153), whereas excellent animal studies are clearly negative (154). Many possibly damaging environmental impacts on spermatogenesis, from prenatal to adult life, are proposed but remain speculative (155).

Genetic risk of older fathers

Male aging has modest but significant effects of increasing the very low absolute risk of some rare autosomal dominant genetic disorders (eg, achondroplasia, Apert syndrome, Noonan syndrome, and Costello syndrome), genetic mutations, chromosomal defects, and epigenetic changes (147), as well as neuropsychiatric disorders (156). These paternal age effects, arising from cumulative de novo DNA copying errors during hundreds of rounds of mitotic and meiotic replication during spermatogenesis over a man's lifetime, can become entrenched in the genome through selection of mutations that enhance proliferation of their own spermatagonial clone over others (157); however, their low prevalence makes them difficult to fully disentangle from more potent overlaid teratogenic effects of female aging and pregnancy. Further insight into the testicular origins of paternal age effects on reproductive outcomes (158) is highly desirable given the increasing rates of older men fathering children both naturally and via in vitro fertilization after remarriage to younger women.

Sexual function in male aging

Male sexual function operates as a hydraulic neurovascular mechanism subserving erection and culminating in an autonomic neural reflex for ejaculation. Although initiation of adult male sexual function at puberty requires adult male blood testosterone exposure, maintenance of men's sexual function requires only a low blood testosterone threshold. Hence erectile dysfunction (ED), the most prevalent male sexual dysfunction, which is steeply age dependent, is both associated with age-related comorbidities and predicts future cardiovascular events (159). However, ED is rarely due to androgen deficiency when it is part of a pathologic form of hypogonadism. Furthermore, in a longitudinal cohort study, reduced sexual activity from any cause (drugs, depression, organic ED) was associated with decreases in blood testosterone concentrations (160), whereas concentrations increased with increased sexual activity (161). This overlooked observation often leads to confusing mildly reduced blood testosterone as the cause rather than the effect of reduced sexual activity, a major contributor to the excess of unjustified testosterone prescribing over recent decades (162). As a sound alternative, the safety and efficacy of phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors for ED in older men is now well established for many underlying medical causes of ED, subject to avoidance of adverse drug interactions such as with nitrates (163).

Testosterone measurement

Analytical research into the impact of male aging on reproductive and general health depends crucially on accurate measurement of testosterone and its bioactive metabolites dihydrotestosterone and estradiol (as well as ideally precursors and other metabolites). For this purpose, steroid liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC-MS) can provide accurate, multi-analyte profiles, allowing for a dynamic picture of net androgen action. However, although steroid LC-MS is now dominant in clinical research as the steroid immunoassay era draws to a close, affordability and general availability of steroid LC-MS methods in clinical practice remains challenging. This is due to commercial lock-in of pathology laboratories to multiplex immunoassay platforms in which steroid analytes remain a minor component but provide quick, inexpensive, albeit often inaccurate results. Laboratory measurements of testosterone fractions (“free,” “bioavailable”) are technically demanding, laborious manual methods which remain unstandardized and lack reference standards, quality control, or reference ranges (164). Consequently, lab measurements of derived fractions of blood testosterone are rarely available and are replaced by inaccurate calculational formulas. These formulas are inevitably a deterministic (inverse) function of age (165) but empirically add no significant prognostic information to accurate LC-MS testosterone measurements (166). The circadian and ultradian pattern of testosterone release should also be considered in interpretation of testosterone measurements.

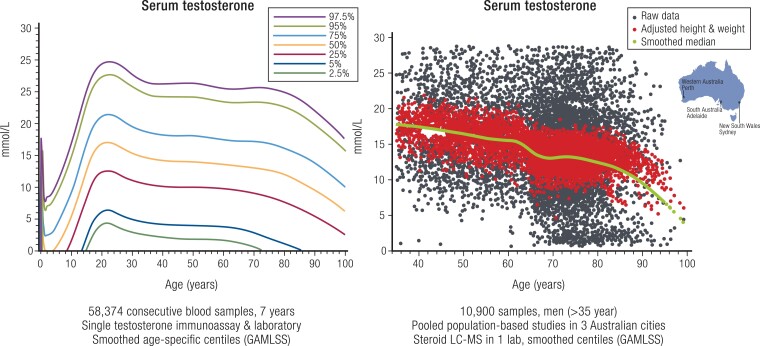

LC-MS measurement of testosterone and related steroids in population-based studies is supplanting immunoassay use in determining the natural history of blood testosterone levels in male aging (167-171). Whereas immunoassay studies reported a gradual, modest, but inconsistent decline in testosterone levels with age among Western men (Fig. 5), recent evidence shows no age-related changes in Japanese (172) or Chinese (173) men, nor in LC-MS data from pooled Western studies (174). These studies highlight lifestyle confounders of the age-related reduction in blood testosterone, notably overweight/obesity, insulin resistance or diabetes, smoking, cardiovascular disease, and depression (175-177), which explain most or all apparent age-related reductions in serum testosterone. There is inadequate research on whether testosterone improves these comorbidities of aging. In addition, there are interesting speculations based on limited interventional (178), observational (179), and mechanistic (180) studies suggesting androgen effects on telomerase as a potential hormonal influence on an underlying mechanism of aging.

Figure 5.

Age-specific profile of serum testosterone in men. Left panel comprises 58 374 consecutive serum samples over 7 years measured in a single immunoassay and pathology laboratory with population centiles deduced by smoothed GAMLSS methodology. Right panel comprises 10 900 serum samples pooled from 3 population-based Australian studies showing the raw scatter (black dots), height and weight-adjusted scatter (red dots), and the smoothed median (green solid line) deduced by GAMLSS methodology. Redrawn and adapted from Handelsman DJ et al Ann Clin Biochem, 2015; 53(3):377-385, © SAGE Publications (left), and redrawn from Handelsman DJ et al (168), © 2015 European Society of Endocrinology (right).

Although the sole unequivocal indication for testosterone treatment is for replacement therapy in men with pathological reproductive disorders, there is strong public interest in extending the use of testosterone outside endocrine disorders, notably for rejuvenation, an application with a deep aspirational history throughout human civilization long preceding modern endocrinology. The modern embodiment of this prescientific belief in testosterone as the pivot of male sexual, reproductive, and general rejuvenation was the re-emergence as “andropause” over the turn of the 21st century (181). That wishful thinking underlies the 100-fold increases in global pharmaceutical testosterone sales over 3 decades (182), including 10-fold increases in the United States and 40-fold in Canada over the first decade of the 21st century (162), in the absence of any new approved indications for testosterone treatment. An important public health challenge is to evaluate the impact of this decades-long epidemic of testosterone prescribing, possibly abating recently (183, 184), on underlying rates of cardiovascular and prostate diseases. Both of these diseases have displayed significant temporal changes over recent decades, which makes discerning an overlaid impact of changes in testosterone administration challenging.

Available Therapies

While numerous testosterone products are approved for oral, transdermal, injectable, or implantable (and in some countries, buccal and intranasal) administration to men with pathologic hypogonadism (185), none are approved for use in male aging. In men of any age without contraindications (nitrate vasodilators) or CYP3A drug interaction, phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors (sildenafil, tadalafil, and congeners) are highly effective and well tolerated for improving erectile function (186). Urinary human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) is approved for treatment of gonadotropin-deficient male infertility but has little applicability to male aging where the predominant testicular defect is intrinsic Leydig cell failure, and hCG does not achieve sustained benefits. Likewise, clomiphene and aromatase inhibitors should not be used to increase endogenous testosterone due to their adverse effects on estrogen-dependent male sexual function and bone density.

Clinical Trial Data on Efficacy and Safety in Older Individuals

Based on testosterone's prominent effects on muscle structure and function, placebo-controlled interventional studies investigating potential effects of testosterone aiming to reverse age-related muscle loss (sarcopenia) or weakness (frailty) have been conducted. However, these studies have produced inconsistent and/or inconclusive findings, largely due to relatively small sample sizes (vs small magnitude of benefits) and heterogeneity of study cohorts and endpoints. Salutary findings were produced by the Testosterone in Older Men with Mobility Limitations (TOM) trial in which 209 men aged 65 years or over (average 74 years) with a high prevalence of obesity, hypertension, diabetes, and hyperlipidemia were treated with daily transdermal testosterone or placebo gel for 6 months; however, the study was terminated prematurely for an excess of cardiovascular adverse effects (187). Analogous studies of testosterone treatment in frail and/or sarcopenic older men also had minor benefits but without these adverse cardiovascular effects (188-190).

The 1994 Institute of Medicine (IOM, now National Academy of Medicine) review of male aging concluded there was insufficient efficacy evidence to justify a large, placebo-controlled RCT of testosterone for an age-related reduction in blood testosterone in men without reproductive pathology. They recommended short-term efficacy studies to justify a costly, large-scale trial. Subsequently, the National Institutes of Health (NIH)-funded Testosterone Trials, a series of 7 well-integrated, overlapping RCTs involving daily transdermal testosterone or placebo gel for 12 months were conducted. These studies recruited 790 men aged 65 years and older who had consistently low morning serum testosterone (<9.5 nmol/L) and a high prevalence of obesity (63%), hypertension (72%), diabetes (37%), and current or former smoking (66%) (191). The key findings were a modest but transient benefit for sexual function, small and expected increases in hemoglobin and bone density, but no benefits for vitality or physical or cognitive function (192). Findings also included adverse effects of testosterone on erythrocytosis and an increase of noncalcified coronary plaque size (192-194). Although the T Trials were not powered to detect cardiovascular endpoints, this latter safety signal needs evaluation, given the widescale usage of off-label testosterone in older men.

An adequately powered long-term safety study is needed to determine whether testosterone treatment of older men without reproductive pathology causes adverse cardiovascular or prostate events. Although the Testosterone Trials failed to meet the IOM mandate for a public sector placebo-controlled efficacy study, a large-scale, long-term industry-funded FDA-mandated safety study (TRAVERSE) is underway aiming to define the cardiovascular safety of testosterone treatment of men with age-related low blood testosterone in the absence of reproductive pathology (195). In the interim, numerous meta-analyses aggregating smaller, shorter-term RCTs report inconsistent and inconclusive evidence for cardiovascular effects (196-198), largely due to underpowering (especially exposure duration), failure to recognize transient adverse effects (196, 199), and industry source funding bias (200). In the T4DM study, 1007 men with impaired glucose tolerance were randomized to injectable testosterone undecanoate (1000 mg) or placebo every 3 months for 2 years, with a reduction in the incidence of diabetes along with an unacceptably high rate of erythrocytosis (22%) (201), together with a slow recovery of testicular endocrine function of at least 12 months (202).

Furthermore, the consequences of testosterone treatment on late-life prostate diseases, including cancer and hyperplasia, require elucidation. While strong evidence exists against any predictive relationship between endogenous testosterone and its metabolites with future diagnosis of prostate cancer over the following decade (203, 204), and there is no evidence of increased prostate disease in meta-analysis of short-term trials of testosterone treatment (205), more powerful RCT evidence is required before the risk of exogenous testosterone administration accelerating late-life prostate diseases can be considered dispelled.

Key Points

Spermatogenesis and steroidogenesis are both negatively impacted by comorbidities associated with aging rather than aging itself.

ED is rarely due to androgen deficiency. Phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors are an effective treatment for older men with ED.

Use of steroid immunoassays for measurement of testosterone rather than the preferred LC-MS assays may result in inappropriate diagnosis of low testosterone levels.

The Testosterone Trials showed modest but transient benefits in testosterone treatment for sexual function, small and expected increases in hemoglobin and bone density, but no benefits for vitality or physical or cognitive function and an adverse effect of testosterone to increase noncalcified coronary plaque size. These data do not support the use of testosterone to treat these comorbidities of older men.

A large safety study (TRAVERSE) is underway to evaluate the cardiovascular events during 5 years of daily testosterone vs placebo gel treatment.

Gaps in the Research

Given the lack of convincing efficacy and uncertain safety of testosterone administration to aging men without reproductive pathology, future clinical research on testosterone treatment should focus primarily on whether testosterone administration improves the comorbidities of aging and/or has direct effects on putative underlying mechanisms of aging, and at what threshold of testosterone level. The potential adverse effects of long-term testosterone administration on cardiovascular and prostate diseases in such men also require additional research. Additionally, in the absence of any natural disorders of excessive testosterone secretion in men, possibly reflecting the evolutionary tolerance for sharp increases in testosterone secretion during male puberty, careful exploration of the efficacy and safety of short-term, higher doses of testosterone or other natural nonaromatizable androgens (eg, DHT, nonsteroidal androgens) for specific aging comorbidities may be warranted.

While clinical therapeutics will always require adequately powered, placebo-controlled study of natural or synthetic androgens, analytical research into cellular and molecular mechanisms of androgen action in key target tissues (muscle, liver, erythroid cell lineages, bone, prostate, skin, brain) are needed to identify targeted paracrine or intermediary modulators of androgen action, which could point the way to gaining the benefits of target-specific androgen action while avoiding detrimental off-target effects. Further analytical research is also needed to understand the testicular origins of paternal age effects on reproductive outcomes and on the preservation of testicular function.

Thyroid Axis

Natural History/Observational Data in Older Individuals

Clearance of circulating thyroxine (T4) and triiodothyronine (T3) declines with age, resulting in an increase in half-life from 7 days in younger individuals to 9 days in those aged 80 years and older (206). There is a compensatory reduction in the production of T4 and T3. Production of T4 declines from 80 μg to 60 μg daily and production of T3 declines from 30 μg to 20 μg daily (207). In euthyroid individuals with thyrotropin (thyroid-stimulating hormone [TSH]) and free T4 concentrations within the reference range, T3 concentrations are lower in community-dwelling older individuals without acute illness than in younger individuals, suggesting an age-related decline in 5′-deiodinase activity (208, 209).

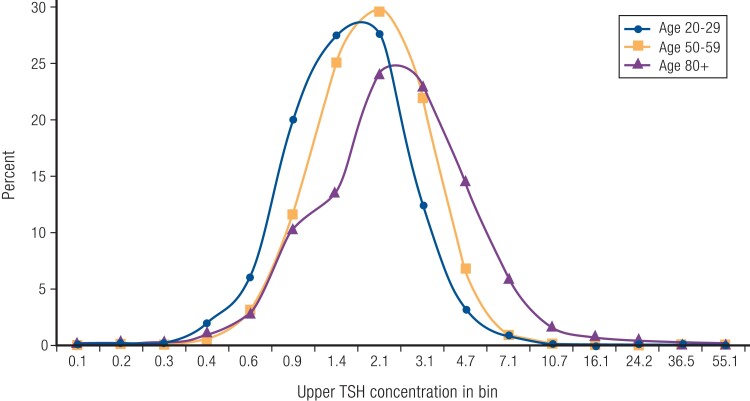

Both cross-sectional and longitudinal studies have shown an increase in TSH concentrations with age, even when limiting to a reference population of individuals without thyroid disease or anti-thyroid antibodies, without any changes in free T4 concentrations (208, 210, 211). The shape of the TSH distribution suggests a population shift to higher levels rather than increased incidence of hypothyroidism at older ages (Fig. 6) (210). Accordingly, a TSH value above the reference range is found in 14.5% of those aged 80 years and older, compared with 2.5% of those aged 20 to 29 years (210). The prevalence of anti-thyroid antibodies also increases with age, particularly in women, consistent with an age-related increase in autoimmune thyroid disease (210). However, anti-thyroid antibody levels are lower in the oldest old (209).

Figure 6.

Distribution of TSH concentrations in a reference population from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Redrawn from Surks MI & Hollowell JG (210). © Endocrine Society.

The majority of older individuals with elevated TSH concentrations have normal free T4 concentrations, a combination of thyroid test results known as subclinical hypothyroidism. It should be noted that subclinical hypothyroidism persists on repeat testing in only 38% of older individuals, with reversion to euthyroidism in the remaining 62% (212). Subclinical hypothyroidism is not associated with an increase in risk of CHD, stroke, heart failure, dementia, disability, or mortality, overall or in the subgroup of individuals with TSH concentrations of <7 mIU/L (213-217). Furthermore, older individuals with subclinical hypothyroidism may have better mobility and functional status than their euthyroid peers (218, 219). Observational data have shown an increased risk of cardiovascular mortality and stroke in subgroups of patients with subclinical hypothyroidism with TSH levels of 7 to 9.9 mIU/L and of CHD, cardiovascular mortality, and heart failure for TSH ≥10 mIU/L (213, 214, 217). Clinical data do not suggest that levothyroxine treatment reduces the risk of cardiovascular events in older patients with subclinical hypothyroidism (220, 221). Furthermore, overtreatment with levothyroxine to TSH concentrations below the reference range is common in older individuals (222).

Subclinical hyperthyroidism—low TSH concentrations with normal concentrations of free T4—is more common in older than in younger individuals due to an increase in autonomous thyroid hormone secretion from thyroid nodules. Subclinical hyperthyroidism is associated with an increased risk of atrial fibrillation, hip fracture, and dementia if left untreated (223-225). Even patients with low, but not suppressed, TSH levels (TSH 0.1-0.44 mIU/L) are at increased risk of atrial fibrillation, CHD, and hip fracture (223, 224). Because older patients have a high baseline risk of these outcomes, subclinical hyperthyroidism is more likely to have clinically meaningful effects in these patients. Furthermore, in euthyroid older patients, free T4 concentrations within the reference range are associated with increased risk of atrial fibrillation, CHD, heart failure, dementia, and mortality (226, 227). These data support a potential role of free T4 concentrations in identifying increased risk of adverse events, independent of TSH concentrations.

Overt hypothyroidism and hyperthyroidism each are more common in older individuals, as are comorbid conditions or medications that affect thyroid function (228, 229). Recognition of overt thyroid dysfunction can be challenging; the classic symptoms of hypothyroidism and hyperthyroidism are reported less frequently in older patients than in younger patients with a similar degree of thyroid dysfunction (230-232). Clinicians may fail to identify common age-related symptoms and syndromes, such as fatigue, depression, cognitive decline, constipation, and falls as related to thyroid dysfunction. In addition, older patients with hyperthyroidism are more likely to have atypical symptoms, such as apathy and anorexia, and less commonly have hyperadrenergic symptoms (231).

Available Therapies

Treatment of both hyperthyroidism and hypothyroidism should take into account the underlying health status of the patient, particularly underlying cardiovascular comorbidities. Levothyroxine is the primary treatment for thyroid insufficiency. Levothyroxine doses in older individuals correlate with total lean body mass and renal function, leading to lower requirements at the time of diagnosis and increased risk of overtreatment (202). Patients with longstanding levothyroxine use may require a dose reduction over time (201). In addition, multiple over-the-counter and prescription medications affect absorption, protein binding, or metabolism of levothyroxine (233). Three options are available for management of an overactive thyroid: antithyroid medication, radioactive iodine, and thyroidectomy.

Clinical Trial Data on Efficacy and Safety in Older Individuals

There have been 2 RCTs of treatment of subclinical hypothyroidism in older individuals, one with 737 adults aged 65 years and older and the second with 105 adults aged 80 years and older (212, 234). Data from individuals aged 80 years and older from the first trial (n = 146) were merged with data from the second trial for analysis. Both RCTs were conducted in participants with persistent subclinical hypothyroidism who were randomized to levothyroxine or placebo and followed for 12 months. The primary outcome was improvement in hypothyroid symptoms or tiredness, with additional secondary outcomes of quality of life, hand-grip strength, cognitive function, blood pressure, weight, waist circumference, and activities of daily living. No benefit was found in either trial of a low dose of levothyroxine (mean dose 50 mcg daily) compared with placebo, as well as no increase in risk. These trials were not adequately powered to examine cardiovascular or other events, nor were they powered to examine subgroups of TSH at 7 to 9.9 mIU/L or 10 to 19.9 mIU/L that observational data suggested were at higher risk of adverse events. Participants enrolled in both trials showed a low thyroid symptom burden, leaving residual questions about management of patients with symptoms of hypothyroidism.

There have been no trials of similar size in older patients with subclinical hyperthyroidism, and the management is based on thresholds established from observational data.

Key Points

A TSH concentration above the reference range in conjunction with a normal free T4 concentration is common in older individuals. Isolated T3 concentrations below the reference range are also common in this age group.

Older individuals with persistent subclinical hypothyroidism with TSH concentrations of <7 mIU/L should not be treated with levothyroxine. This recommendation is based on RCT data.

Whether or not subgroups of older individuals with persistent subclinical hypothyroidism who have TSH concentration of ≥7 mIU/L or significant symptoms should be treated with levothyroxine is debated.

TSH thresholds for treatment of subclinical hyperthyroidism have been established from observational data, but these treatment thresholds and optimal management have not been tested in RCTs.

Gaps in the Research

The etiology of age-associated changes in thyroid function testing is not known. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Clinical Standardization program has created a standardization program for free T4 based on the International Federation of Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine reference system and is standardizing free T4 and harmonizing TSH testing globally. These efforts represent an important step toward establishing whether age-based reference ranges are needed for diagnosis and management of thyroid dysfunction. Potential causes of TSH elevation such as a decrease in the bioactivity of TSH or diminished response of the thyroid to TSH are untested. Whether the age-associated effect on T4 to T3 conversion is persistent and is due to declines in deiodinase activity in older individuals requires further study. In addition, methods to distinguish between age-associated adaptive changes in thyroid function and early hypothyroidism are needed.

RCT data are needed to assess the risks and benefits of treatment of older individuals with subclinical hypothyroidism with symptoms or higher TSH levels and with subclinical hyperthyroidism. RCT data are also needed in patients with subclinical thyroid dysfunction and pre-existing cardiovascular disease or cognitive impairment. Whether the target TSH range for treated thyroid dysfunction should be the same as the range used to define thyroid dysfunction in an older individual also requires evaluation. Additional study of the clinical importance of free T4 measurement in euthyroid older individuals is needed.

Osteoporosis

Natural History/Observational Data in Older Individuals

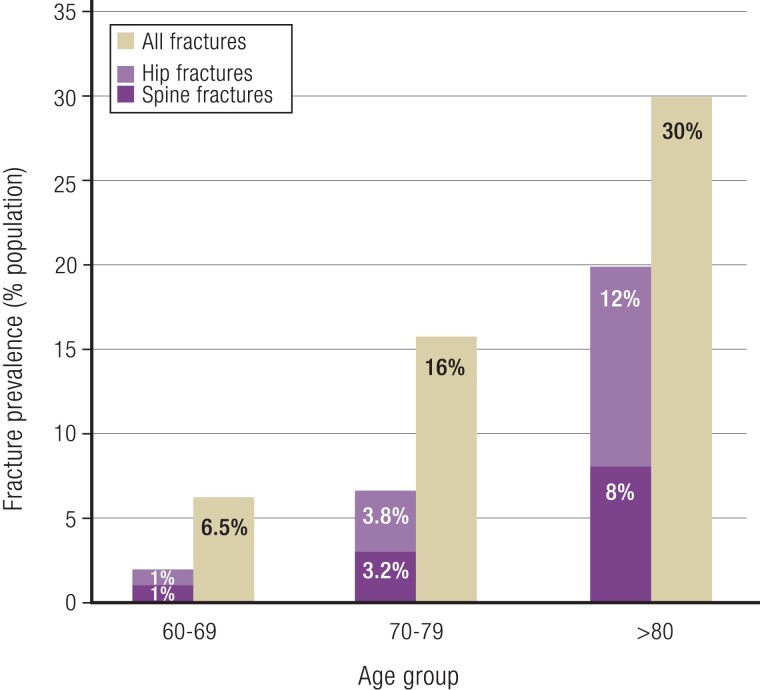

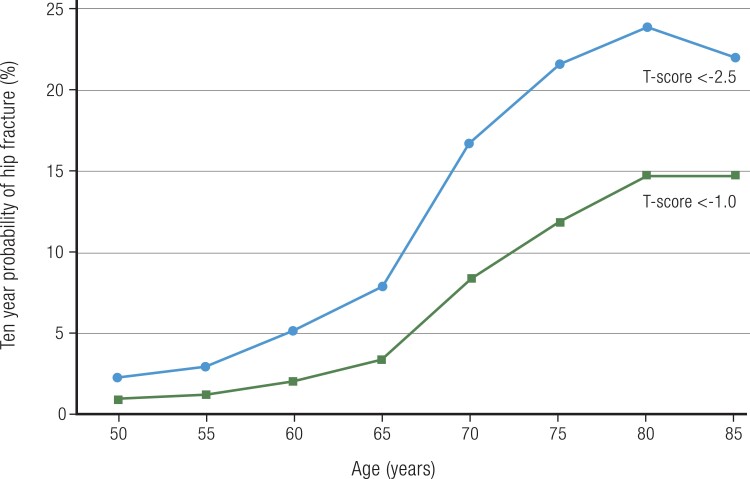

Osteoporosis is a chronic skeletal disorder resulting from progressive bone loss after menopause in women and with advancing age in both men and women (235). This bone loss gradually disrupts bone microarchitecture, impairing bone strength and predisposing to fracture. Patients at high risk of fracture can be readily identified, effective strategies for reducing fracture risk are available, and evidence-based guidelines for managing osteoporosis have been published (235-237).