Abstract

Iron homeostasis is vital for normal physiology, but in the majority of circumstances, like iron overload, this equilibrium is upset leading to free iron in the plasma. This condition with excess iron is known as hemochromatosis, which has been linked to many side effects, including cancer and liver cirrhosis. The current research aimed to investigate active molecules from Streptomyces sp. isolated from the extreme environment of Bahawalpur deserts. The strain was characterized using 16 S rRNA sequencing. Chemical analysis of the ethyl acetate cure extract revealed the presence of phenols, flavonoids, alkaloids, and tannins. Multiple ultraviolet (UV) active metabolites that were essential for the stated pharmacological activities were also demonstrated by thin layer chromatography (TLC) and high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). Additionally, Gas chromatography/mass spectrometry (GC-MS) analysis revealed the primary constituents of the extract to compose of phenol and ester compounds. The 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) assay was used to assess the extract’s antioxidant capacity, and the results showed a good half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) value of 0.034 µg/mL in comparison to the positive control ascorbic acid’s 0.12 µg/mL. In addition, iron chelation activity of extract showed significant chelation potential at 250 and 125 µg/mL, while 62.5 µg/mL showed only mild chelation of the ferrous ion using ethylene diamine tetra acetic acid (EDTA) as a positive control. Likewise, the extract’s cytotoxicity was analyzed through 3-(4,5-Dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay using varying concentrations of the extract and showed 51% cytotoxicity at 350 µg/mL and 65% inhibition of cell growth at 700 µg/mL, respectively. The bioactive compounds from Streptomyces sp. demonstrated strong antioxidant and iron chelating potentials and can prolong the cell survival in extreme environment.

Keywords: Actinomycetes, Streptomyces, Extremophiles, Antioxidant, Iron chealtion

Introduction

Natural products are essential bioactive compounds that are derived mostly from plants, animals and micro-organisms [1]. These includes a diverse group of unique chemical compounds with a wide range of biological activities [2]. Additionally, bacteria in particular those survive in extreme environments are considered a significant source of bioactive molecules. A class of bacteria known as actinomycetes is capable of producing a wide range of organic compounds as secondary metabolites. For instance, the industrial actinomycete Streptomyces avermitilis and the actinomycete Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) each have disclosed about 20 secondary metabolite production pathways. Another illustration is Streptomyces griseus, whose genome sequence led to the discovery of 34 secondary metabolites and 5 production pathways [3–6]. These gene clusters indicate a strong likelihood of finding novel natural compounds.

The largest genus of actinomycetes, Streptomyces, is a Gram-positive soil bacterium that is important in the development of natural products. Waksman and Henrici (1948) were the first to propose the genus Streptomyces, which is one of the most diverse and significant species among microbes. Recently, more than 30 additional genera have been created, and the Streptomyces genus now has 787 species and 38 subspecies [7]. Streptomyces thrive in harsh environments and produce secondary metabolites to extend their survival [8]. More than half of the naturally occurring antibiotics and over 75% of commercially utilized antibiotics have both been obtained from Streptomyces [9].

Chronic transfusions may result in iron excess, which, if left untreated, may harm internal organs. Iron overload can be treated with chelation therapy, which also helps to reduce its negative consequences. [10, 11]Excess of iron contributes to redox processes that stimulate the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and raise oxidative stress [12]. The development of selective iron (Fe) chelators for the treatment of Fe overload diseases such as β thalassemia is an area of much current interest. Chelation therapy provides a viable method of treating iron overload and minimizing the adverse effects associated with iron overload. Chelation therapy was first used in the early 20th century to treat metal poisoning. [13, 14]

The naturally occurring Streptomyces and other bacterial species are diverse and alternate sources of iron chelating compounds which are rarely investigated [15, 16]. The mangrove-derived Streptomyces bacteria known as MUM273b has been evidenced to produce antioxidative compounds with strong iron chelation activities. These natural compounds from bacteria are supposed to prevent protein oxidation and lipid peroxidation thereby protecting the cell damages and downregulating the Haber–Weiss cycle and Fenton pathway [17]. The current efforts in natural product research from plant and microbes portray a significant intents and potential in the field of drug discovery [18, 19]. Keeping in view that most of the sites, and bacteria isolated for natural compounds has the chances of 99% of the repeatability, a lot of attention has been paid to explore the microbes from unique sites [20]. Microbes living in extreme niches are tend to produce secondary metabolites with strong antioxidant and chelation potential to prolong their survival by protecting the radiation-mediated cell damages [21, 22]. In this study, we investigated the significance of the active compounds identified from Streptomyces sp. from the Bahawalpur desert. The ethyl acetate extract was assessed for its phytochemical contents followed by its structural investigation by using analytical techniques. The extract was also evaluated for its potential to quench the superoxide’s and iron chelation capacity and other pharmacological activities. We revealed through GC-MS that the extract has a high content of phenols and ester compounds thereby contributing to its active nature and bioactivities.

Materials and methods

Chemicals

All chemicals used were of analytical grade (E. Merck, Germany), Methanol, Ascorbic acid, Chloroform, Acetone, Ethanol, Glycerol, n-Hexane, Silica gel, Water for HPLC, TLC plate.

Isolation of radio-resistant bacteria

In sterile zipper bags, 50 gram of surface soil samples were aseptically taken from the desert in District Bahawalpur, Punjab, (28.5062° N, 71.5724° E) Pakistan, and then transferred to the microbiology laboratory at the National University of Medical Sciences, Rawalpindi, Pakistan maintained at 4 °C. the samples were serially diluted in phosphate buffer saline (PBS) and spread on the surface of agar plates i.e. (trypton glucose yeast extract agar (TGY) medium consisting g/L: trypton, 10; yeast extract, 5; glucose, 1). Prior to incubation, all the plates were irradiated for 5 minutes’ with ultraviolet-B radiation, wavelength of 280 nm to isolate any potent strain with UV resistant [21].

Identification of radio-resistant bacterium

Using previously established techniques, Streptomyces strain was identified visually and biochemically based on its great tolerance to UV light [23]. By sequencing the 16 S rRNA gene, molecular identification was accomplished. This was accomplished by isolating the DNA by using an extraction kit from QIAGEN in Hilden, Germany, and amplification of the 16 S rRNA gene sequence by using the bacterial primers 27 F′ (5′-GAGTTTGATCMTGGCTCAG-3′) and 1492R′ (5′-GGYTACCTTGTTACGACTT-3′). The PCR product was sequenced at Macrogen Service Center (Geunchun-gu, Seoul, South Korea). In order to identify the sequence’s closest relatives, the sequence was BLAST (Basic Local Alignment Search Tool) in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) database using Molecular Evolutionary Genetic Analysis (MEGA) version 6.

Extract preparation of streptomyces strain

Fresh Streptomyces strain culture was inoculated into the 1000 mL fermentation medium to start the fermentation process. The selected fermentation media for the Streptomyces strain was the trypton glucose yeast extract (TGY) medium [21]. The TGY was fermented in an Erlenmeyer flask for three to four days at 28 °C in a shaking incubator (Thermo Scientific Heratherm, USA) at 200 rpm. The fermentation medium was centrifuges (Thermo Scientific Sorvall Legend XTR, USA) for 15 min to remove biomass at 12,000 x g, and the supernatant was collected using Whatman filter paper. The supernatant was mixed with an equal volume of ethyl acetate for 72-hours to ensure the bioactive molecules extraction. Using the rotary evaporator (Thermo Scientific Rotary Evaporator R-100, USA) the filtrate includes ethyl acetate was dried out at 40 oC. The residue was then refined with methanol to yield (5.4 g) of light brown crude extract [24].

Chemical analysis

Preliminary, qualitative tests of the extract from Streptomyces sp. for identification of alkaloids, flavonoids, glycosides, saponins, tannin, reducing sugars, anthraquinones, and terpenoids were carried out by the method described by Harborne, Saddiqui Cho, and Auwai [25–28].

Thin layer chromatography (TLC)

The extract from Streptomyces sp. was reconstituted in ethyl acetate and spotted on a TLC silica gel (60F254) plate which was used as a stationary phase. N-hexane: ethyl acetate (1:1) was used as a mobile phase for the determination of the eluent with maximum performance. The TLC plates were evacuated from the chamber when the mobile phase was less than 1 cm from their maximum position. The plates were quickly stained with molybdic acid and ceric sulphate and dried in a heating chamber after the solvent fronts were stamped. The TLC plates were visualized with a UV light (254–365 nm) for any possible spots and other dry phytochemical components. Molybdic acid was employed for phenol, steroid, and other compounds, whereas ceric sulphate was used for recognizable flavonoid evidence. On the basis of values for the retardation factor, the affinities of chemicals were computed (RF values).

Rf

High performance liquid chromatography

The extract of ethyl acetate was analyzed using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC Waters™ e2695) to identify the different chemicals and to check their available quantity in multiple concentrations. It was accomplished with the help of a combination of an extract with the exact HPLC grade methanol, then filtering the resulting mixture through a 0.45-millimetre syringe filter to generate a stock solution. The chromatogram was ultimately captured after a number of stock solution dilutions and the injection of 20 µL sample. The sample was analyzed by a 100Å, 5 μm, 4.6 mm X 250 mm, Waters C-18 reverse-phase column that was eluted at a rate of 1 mL/min using a gradient of 80 to 100% methanol, at 470 nm which lasted 30 min. The photodiode array (PDA) detector was used to capture the absorption spectra of all pertinent peaks [29].

Gas chromatography- mass spectrometry

To identify and measure the concentration of active compounds the sample was analyzed through gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) using a prescribed methodology with minor adjustments [30]. The sample was examined using THERMO Scientific’s (DSQ11) GC. A 30-meter-long TR-5MS capillary column with a 0.25 nm internal diameter and a 0.25 mm film thickness; installed in the GC. The temperature of the injector and detector was 250 °C with a carrier gas (Helium) at a speed of 1 mL/minute The injector was adjusted in split mode. The sample was injected into the oven at 50 °C for a few minutes, increased to 150 °C at a rate of 8 °C per minute, and then increased to 300 °C at a rate of 15 °C per minute, held for 5 min. By comparing the constituents’ mass spectral data to those in the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) collection, the constituents were identified.

Evaluation of anti-oxidant activity

DPPH-radical scavenging activity

Based on a previously established procedure with slight modifications, the radical scavenging activity of DPPH (2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl) of Streptomyces extract was investigated [31]. Different concentration of the ethanol-diluted extract (10,20 30 and 40 µL) was added to previously prepared 5 mill molar DPPH in a 96-well plate; adjusting the final volume to 200 µL respectively. The mixture was gently mixed and incubated for 30 mints at room temperature. A microplate reader was used to measure the absorbance at 550 nm. The experimental positive control was ascorbic acid. The proportion of DPPH radical scavenging activity was determined using the following formula:

%DPPH scavenging activity=

Metal chelating activity

The extract’s ability to scavenge ferrous ions was investigated using the previously described approach, with minor modifications [32] using ferrozine can quantitatively combine with ferrous iron to produce complexes that are red in color. Different concentration of the samples ranges from 250, 125, and 62.5 µg/mL was transferred in to 96 well plate followed by addition of 70 µL 2 mM FeCl2. The mixture was incubated for 10 min at room temperature and finally adding previously prepared 5 mM ferrozine in 10 µM sodium acetate making final volume to 200 µL. The reaction mixture was incubated at room temperature for 30 min. The absorbance was measured at 492 nm while using EDTA as a positive control, which is a strong chelator. All the experiments were performed in triplicate. The metal chelating activity was calculated by the following formula:

% Metal chelating activity =

Cytotoxicity assay

The cytpotoxic activity of the Streptomyces extract was evaluated by using Hep G2 (Hepatocellular carcinoma) cell lines through a rapid colorimetric test [33]. using MTT [3-(4,5-Dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-Diphenyltetrazolium Bromide]. In a 96-well plate, the Hep G2 cell lines seeded to a density of 104 cells/mL for 24 h using DMEM (Dulbecco’s Modified Essential Medium) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1x penicillin-streptomycin-neomycin to sustain the cells. To test the antiproliferative activity, various concentration ranges between (10–700 µg/mL) were added and incubated at 37 °C for one day using 5% carbon dioxide. To determine the metabolic activity of the cells, 20 µL of MTT solution (0.25 µg/mL), a yellow tetrazole that transforms into purple formazan in living cells, was added. The plates were agitated for 20 min to ensure the proper mixing and avoid any turbulence in the final reading followed by measurement of the optical density at 570 (Bio Rad). Cells without any treatment served as controls for 100% cellular viability. To calculate the accurate values, the average of blank (controls) was substituted using the medium components along with DMSO and finally plotting the cell viability versus time with different concentrations of the tested sample. The percent inhibition was calculated using the following formula.

% Inhibition =

Statistical analysis

To represent the data, the average across three (3) consecutive readings was taken. By using (IBM SPSS Statistics 29), Student’s t test was performed to assess the significance of the data, the p < 0.05 value was considered to be significant. Percentage scavenging and chelation activity of extract were studied by regression analysis between the percentage of scavenging and their respective concentrations. Single factor and two-way analysis of variance were applied for analysis of between groups and within a single group for MTT and iron chelation assay.

Results

Isolation and identification of the radioresistant strain

The studied Streptomyces strain isolated from Bahawalpur deserts was studied microscopically, was found Gram-positive long filamentous rod, with irregular, off-white, raised anddry, colonies on the surface of agar medium. Additionally, the 16 S rRNA sequencing of this strain was performed, which was put together using DNA Baser software, and was put through the BLAST search engine called NCBI. According to the findings, the obtained strain is a member of the Streptomyces genus submitted with accession PP494735. The isolated strain demonstrated 99.95% similarity to Streptomyces sp. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/PP494735.1/. The strain showed high UV resistance and was able to sustain at a UV dose of 2,000 J/m2.

Fermentation extraction from streptomyces culture

The cell-free supernatant was pooled with an equal amount of ethyl acetate for extraction The ethyl acetate extracts were combined and concentrated under low pressure, which afforded a dark brown crude extract that was 5.4 g Before proceeding further, the extract was assembled and mixed in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) with a final concentration of 5 mg/mL.

Chemical analysis of the extract

To verify the existence of major groups of chemical components, a chemical evaluation of the extract from Streptomyces was performed. The data showed that significant chemical groups were present, such as phenolic compounds, diterpenes, triterpenes, alkaloids, flavonoids, glycosides, and carbohydrates (Table 1).

Table 1.

Chemical results of streptomyces extract

| S. no | Chemical constituents | Results |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Carbohydrate | + |

| 2 | Alkaloids | + |

| 3 | Saponins | − |

| 4 | Phenol | + |

| 5 | Flavonoids | + |

| 6 | Glycosides | + |

| 7 | Tannins | − |

| 8 | Diterpenes | + |

| 9 | Anthraquinone | − |

Notes; absent: −, present: +

TLC analysis of crude extract of streptomyces

The crude extract upon TLC screening revealed different Rf values which demonstrated that our extract is a combination of several chemicals that were computed. The crude sample exhibited high UV activity, which was analyzed by UV-VISI at 254 and 365 nm to identify unique spot chemicals using a mobile stage (chloroform and ethyl acetate at a 1:1 ratio) (Fig. 1). Tables 2a, 2b, and 2c display deferent the Rf values for crude extract.

Fig. 1.

TLC plate displays the various fraction of Streptomyces crude extract. TLC plate shows the separation of compounds from Sample A by using chloroform and ethyl acetate at a 1:1 ratio

Table 2.

A: TLC rf value of crude extract at 254 nm

| S.no | Compound | Rf Value |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | A | 0.07 |

| b: TLC Rf values of crude extract at 365 | ||

| S.no | Compound | Rf Value |

| 1 | A | 0.07 |

| 2 | B | 0.75 |

| 3 | C | 0.88 |

| c: TLC Rf values of crude extract at 254 | ||

| S.no | Compound | Rf Value |

| 1 | A | 0.05 |

| 2 | B | 0.85 |

HPLC analysis of streptomyces crude extract

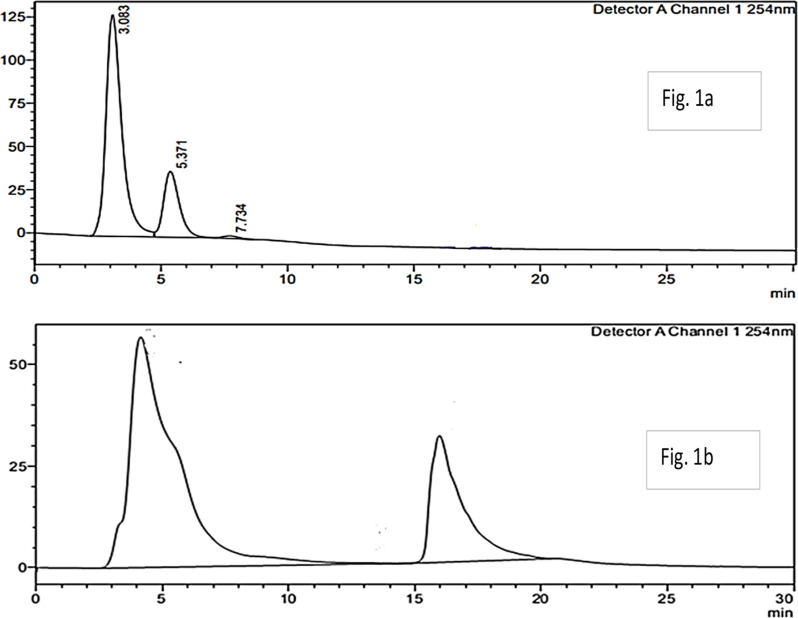

The crude ethyl acetate extract of Streptomyces sp. was initially investigated using the RP-HPLC (C-18) column. HPLC, UV analysis of the crude extract displayed two major broad peaks at 254 nm, whereas their intensity was very low at 360 nm which is shown in Fig. 2a. Moreover, both major peaks displayed shorter retention times with 2.6 and 5.7 min respectively. Furthermore, another HPLC method was developed in which the two major peak retention times were further increased by increasing the concentration of H2O during the elution (Fig. 2b).

Fig. 2.

HPLC chromatogram of Streptomyces sp. Crude extract: Mobile phase Methanol in a gradient mode 80–100%, Wavelength 254 and 360 nm gradient elution Fig. 1a. HPLC chromatogram of Streptomyces Crude extract with increase retention time and more visible peaks b adding water during elusion Fig. 1b

GC-MS analysis of ethyl acetate extract

GC-MS analysis of the ethyl acetate extract of Streptomyces sp. displayed several peaks that highlighted the presence of concerned compounds. The constituents that are present in the extract GC-MS spectra were compared with already reported compounds library, as a result, seven different bioactive chemicals responsible for the given pharmacological activities of the extract were identified as given in Table 3. Similarly, the mass spectra and chemical structures of the constituents which were detected in the ethyl acetate extract of Streptomyces sp. are displayed in Figs. 3 and 4.

Table 3.

Characteristic data of GC-MS analysis of the ethyl acetate extract

| S. No | Constituents | R T (minute) | M Formula | M W | P height |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Phenol, 2,4-bis(1,1-dimethyl ethyl) | 12.33 | C14H22O | 206 | 332038.28 |

| 2 | 1,2-Benzenedicarboxylic acid, dioctyl ester | 22.33 | C24H38O4 | 390 | 32,590,117. |

| 3 | 3-Methoxymethoxy-3,7,16,20 tetrameth yl-heneicosa- 1,7,11,15,19-pentaene | 21.49 | C 27H46O2 | 402 | 139740.82 |

| 4 | 1,3-Benzenedicarboxylic acid, bis(2-ethylhexyl) ester | 23.28 | C 24 H38O4 | 390 | 331262.79 |

| 5 | Glycine, N-[(3à,5á,7à,12à)-24-oxo-3,7,12tris[(trimethylsilyl)oxy]cholan-24-yl]-, methyl ester | 25.92 | C36H69NO6Si3 | 695 | 792109.21 |

| 6 | 1,2-Benzenedicarboxylic acid, di-isooctyl ester | 22.33 | C 24 H38O4 | 390 | 32,590,117. |

| 7 | Ethyl iso-allocholate | 23.65 | C 26 H44O5 | 436 | 220872.88 |

Fig. 3.

GC-MS spectra of the predicted compounds

Fig. 4.

Structure elucidation of compounds 1–7

Antioxidant assay

DPPH radical scavenging activity (%)

Our results revealed that ethyl acetate extract has a significant DPPH radical scavenging activity and the color of diphenyl picrylhydrazine (reduced form) changed from a violet DPPH radical solution to a yellow. The results showed that Streptomyces sp. extract, exhibited an increased activity in a concentration dependent manner when used in a concentration ranges from 0.015625 to 0.5 mg/mL, as shown in Fig. 5. The IC50 value was calculated 0.034 mg/mL which indicated potent activity. Similarly, ascorbic acid which was used as a positive control demonstrated an IC50 at 0.12 mg/mL, as shown in Table 4.

Fig. 5.

DPPH scavenging activity (%) using different concentrations (0.03125-01 mg/mL) of ethyl acetate extract and ascorbic acid

Table 4.

% DPPH free radical scavenging activities and IC50 of ethyl acetate extract and ascorbic acid

| Sample | Concentration mg/mL | % DPPH scavenging activity | IC50 mg/mL |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ethyl acetate extract | 0.5 | 80.862 ± 0.170 | 0.034 |

| 0.25 | 76.080 ± 0.121 | ||

| 0.125 | 70.664 ± 0.092 | ||

| 0.0625 | 66.657 ± 0.085 | ||

| 0.03125 | 46.668 ± 0.134 | ||

| 0.015625 | 40.732 ± 0.115 | ||

| Ascorbic acid | 0.12 |

Metal chelating activity

The extract showed substantial iron chelation activity when used at 250 and 125 µg/mL concentration that signify its potential in iron chelation therapy. The chelation activity was declined when the sample was used in low concertation i.e. 62.5 g/mL as shown in Fig. 6. Our study revealed that, in comparison to the control EDTA which is a strong chelator, the crude ethyl acetate extract of Streptomyces sp. demonstrated strong ion chelating activity, which further pointed out the importance of this extract against reactive oxygen species suppression.

Fig. 6.

Metal chelating activity of different concentrations of extract and EDTA

Cytotoxicity

MTT assay

By using the MTT assay on 96-well plates, the cytotoxic effects of various doses of ethyl acetate extract on HepG2 cell lines were assessed. The IC50 values were calculated as 352 µg/mL for HepG2 cell lines. The results revealed that the extract exhibited concentration-dependent inhibition on HepG2 cells. As illustrated by Fig. 7, 350 µg/mL of the extract showed 51% cytotoxicity whereas 700 µg/mL inhibited 65% of cell growth. According to the reported IC50 value, the extract was less harmful to normal cells than it was to cancerous cells. Antiproliferative activity of Streptomyces extract against HepG2 cell line using MTT assay was measured by plotting the dose response curve verses concentration of tested sample and percentage viable cells through linear regression analysis by which the IC50 was obtained.

Fig. 7.

% Cell viability of Hep G2 cell after 48 h incubation with different concentrations (10.75–700 µg/Ml) of Streptomyces sp. extract

Discussion

Natural products are usually obtained from different sources including plants animals and microbes. Among the microbes, the extremophiles are getting attention due to their ability to survive in extreme environments and high diversity which consequently lead them to produce diverse biomolecules with potent biological activities [8, 34]. These organisms have biosynthesized various biomolecules such as carotenoids, and compatible solutes as part of their defense mechanisms to extend their survival [35, 36]. Streptomyces, which is the genus of the actinomycetes, is significantly important in the manufacture of therapeutically important compounds such as antibacterial, antifungal, antitumor agents, and immunosuppressants. Interestingly hundreds of compounds have been isolated from Streptomyces, most of which are currently used as allopathic medicine to suppress various ailments [8].

Among the 12 isolates from desert samples, WM-32 was selected based on high UV tolerance and ability to produce high-active compounds. The strain demonstrated 99% of the similarity to the Streptomyces genera through phylogenetic analysis. TGY broth was the choice of fermentation at a small scale for Streptomyces sp. The ethyl acetate extract was further fractionated and finally evaporated using a rotary evaporator having low temperature and high pressure, and a crude extract of 5.4 g was obtained. This whole process unveiled that the targeted bacteria Streptomyces sp. was a good source to produce secondary metabolites. Furthermore, chemical analysis was carried out to determine the presence of different classes of compounds, this analysis disclosed that phenols, flavonoids, terpenoids, and alkaloids class of compounds are present in the extract whereas tannins, steroids, and anthraquinones were not detected. The bioactivities of the extract may be the reason for the resonance double ring structure and phenolic groups, which are able to give free electrons to form stable final products and inhibit the formation of superoxides. This phenomenon is quite justifiable by revealing the different antioxidant activities of the extract from Streptomyces sp.

Our analytical analysis i.e. TLC, HPLC, and GC-MS and chromatogram extracted demonstrated a clearer picture of the respective molecules present in the crude extract. The TLC results additionally identified UV active chemicals using spot detection with sulfuric acid and iodine reagent, this led to the discovery of three sites with Rf values of 0.07, 0.75, and 0.88 as well (chloroform: ethyl acetate,1:1). Most of the compounds produced by microbes in extreme environment exhibit a strong coloring potential. The reason might be that those coloring compounds possess a strong chromophore to absorb the toxic UV rays thereby preventing the oxidative damages. The absorption maxima (λmax) at 254 and 360 nm detected through HPLC also suggest the presence of strong phenolics, flavonoids, and keto groups [37]. The resonance structure of such molecules is thought to contribute towards the antioxidant and iron chelating potential [38]. The peak resolution and retention time during the HPLC was also improved by addition of H2O to the mobile phase which results in the HPLC peaks separating apart [39]. Our GC-MS analysis of the ethyl acetate extract demonstrated 6 different compounds that contributing to the bioactivities. These bioactive compounds are supposed to be produced by extremophiles in harsh environment to prevent desiccation, cell damage and thereby these are also considered as cell factories for bioactive compounds [40]. Based on the NIST database it was predicted that the bioactive molecule is the constituent of seven predominant compounds composed preliminarily of components like alcohols, esters, phenolics, and cyclic terpenoids.

The mono-esterified, phenolics and flavonoids from Streptomyces sp. showed a twofold stronger quenching ability of superoxides than has been reported for other active metabolites and β-carotenes. This characteristic may be attributed to the extra keto-group substitution and length of their conjugated double-bond system [21]. The antioxidant potential of bioactive compounds from radio-resistant microbes has been recognized as a contributory factor to the radioprotection offered by different compounds [41].

Recent studies highlighted that the reactive oxygen species (ROS) has a considerable role in different diseases like cancer, autoimmune disorders, `and neurodegenerative diseases [42]. Phenolic compounds and their derivatives are well known for their antioxidant activities. Interestingly the ethyl acetate crude extract exhibited considerable scavenging activity concentration concentration-dependent manner in comparison with the reference compound i.e. ascorbic acid. The potential of any active molecule to scavenge the free radicals is dependent on its capability of donating hydrogen atoms to other radicals thereby producing end stable products [43]. The degree of discoloration of DPPH is strong evidence for any active compound to scavenge free radicals showing that with an increase in concentration of the compound the ability to quench superoxide also increases.

Our ethyl acetate extract demonstrated high chelation activity in a concentration-dependent manner. The complex formation of ferrozine with ferrous ion yields a red color. However, any presence of the chelating agent disrupts the formation of complex resulting in decrease in red color formation. The iron chelation activity is of great significance because the transition metal ions are helpful to oxidize agents through fenton pathway which results in oxidative damage in neurodegenerative disorders [44]. The current studied strain isolated from Bahawalpur desert and its bioactive extract offers significant iron chelation potential. Chelation therapy to treat iron overload diseases include thalassemia and other anemic conditions is on rise to neutralize the freely available iron in the body. Exploring the metabolic pathways and further investigation the active ingredients in the extract will open new avenues in chelators from extremophiles [23].

Further we also evaluated the cytotoxic effect by use of MTT assay in 96-well plate on Hep G2 cell lines. Streptomyces sp. is considered as potentially important source of novel bioactive anticancer compounds and capable of producing chemically diverse compounds without any side effects for variety of clinical applications [45]. The cytotoxic mechanism of such natural compounds is to interfere with the basic cellular functions i.e. cell cycle arrest, invasion, inflammation and apoptosis. Many anticancer drugs from the extremophiles and other marine microbes reported to cause cytotoxicity and cell death through apoptosis. Several cytotoxic drugs are available in the market today however most of them lack tumor specificity and can cause damage to the normal tissues as well. Our study revealed that the crude ethyl acetate extract of Streptomyces sp. was a mixture of various bioactive compounds which displayed significant pharmacological activities, especially the antioxidant potential of the crude extract was several fold more effective than the antioxidant effect of ascorbic acid, which was used as a positive control in this study.

Conclusion

It was concluded that Streptomyces sp. is a rich source of several bioactive constituents which were initially highlighted by the presence of various chemical classes such as alkaloids, flavonoids, phenols, and terpenoids. In pharmacological screening, the ethyl acetate crude extract displayed potent antioxidant activities using DPPH. Similarly, the ethyl acetate crude extract also exhibited significant iron-chelation activity and cytotoxic activities against HepG2 cancer cells dose-dependently. These overall results highlighted that Streptomyces sp. is a rich source of important bioactive metabolites and could be a potential source of antioxidant and anti-cancerous compounds to prevent the cells from oxidative damage induced by superoxide’s.

Limitations of the study and future work

Identifying and characterizing the specific compounds responsible for antioxidant and iron chelating activities is a complex process. The study faced challenges in isolating and purifying these compounds, potentially leading to incomplete identification of bioactive molecules. However, by incorporating these metabolomics-focused future directions, researchers can gain a deeper understanding of the metabolic landscape of Streptomyces sp., optimize the production of valuable bioactive compounds, and explore new applications for antioxidants and iron chelators in various fields.

Author contributions

Conceptualization, original draft writing, reviewing, and editing: Imran* Shah, Zia Uddin*, Maheer Hussain, Muhammad Imran Amirzada, Atif Ali Khan Khalil, Arshia Amin. Formal analysis, investigations, funding acquisition, reviewing, and editing: Faisal Hanif, Liaqat Ali, Wasim Sajjad, Tawaf Ali Shah. Resources, data validation, data curation, and supervision. Turki M. Dawoud, Mohammed Bourhia, Wen-Jun Li.

Funding

This research was supported by Higher Education Commission Pakistan under Startup Research Grant Program SRGP-1987. The authors also express their gratitude to the Researchers Supporting Project number (RSP2024R197), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia for supporting this reseach

Data availability

The 16 S rRNA sequence data has been submitted to GenBank/DDBJ/ENA under accession no PP494735.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Imran Shah and Zia Uddin contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Pagmadulam B, Tserendulam D, Rentsenkhand T, et al. Isolation and characterization of antiprotozoal compound-producing Streptomyces species from Mongolian soils. Parasitol Int. 2020;74:101961. 10.1016/j.parint.2019.101961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Katz L, Baltz RH. Natural product discovery: past, present, and future. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol. 2016;43(2–3):155–76. 10.1007/s10295-015-1723-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hertweck C, Luzhetskyy A, Rebets Y, Bechthold A. Type II polyketide synthases: gaining a deeper insight into enzymatic teamwork. Nat Prod Rep. 2007;24(1):162–90. 10.1039/B507395M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baltz RH. Genome mining for drug discovery: progress at the front end. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol. 2021;48(9–10):kuab044. 10.1093/jimb/kuab044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ikeda H, Ishikawa J, Hanamoto A, et al. Complete genome sequence and comparative analysis of the industrial microorganism Streptomyces avermitilis. Nat Biotechnol. 2003;21(5):526–31. 10.1038/nbt820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ohnishi Y, Ishikawa J, Hara H, et al. Genome sequence of the streptomycin-producing microorganism Streptomyces griseus IFO 13350. J Bacteriol. 2008;190(11):4050–60. 10.1128/JB.00204-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Amin A, Ahmed I, Khalid N, et al. Streptomyces caldifontis sp. nov., isolated from a hot water spring of Tatta Pani, Kotli, Pakistan. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek Int J Gen Mol Microbiol. 2017;110(1):77–86. 10.1007/s10482-016-0778-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sajjad W, Ahmad S, Aziz I, Azam SS, Hasan F, Shah AA. Antiproliferative, antioxidant, and binding mechanism analysis of prodigiosin from newly isolated radio-resistant Streptomyces sp. strain WMA-LM31. Mol Biol Rep. 2018;45(6):1787–98. 10.1007/s11033-018-4324-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sujatha P, Bapi Raju KVVSN, Ramana T. Studies on a new marine streptomycete BT-408 producing polyketide antibiotic SBR-22 effective against methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Microbiol Res. 2005;160(2):119–26. 10.1016/j.micres.2004.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eckes EJ. Chelation therapy for iron overload: nursing practice implications. J Infus Nurs. 2011;34(6):374–80. 10.1097/NAN.0b013e3182306356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maurya N, Arya DP, Sengar N. Anaemia in Chronic Renal Failure Patients Undergoing Haemodialysis: A Cross Sectional Study.; 2020. 10.15515/iaast.0976-4828.11.2.4448

- 12.Sheikh D, Kosalge S, Desai T, Dewani A, Mohale D, Tripathi DA. Natural Iron Chelators as potential therapeutic agents for the treatment of Iron Overload diseases. In: ; 2021. 10.5772/intechopen.98749

- 13.Ravalli F, Vela Parada X, Ujueta F, et al. Chelation therapy in patients with Cardiovascular Disease: a systematic review. J Am Heart Assoc. 2022;11(6):e024648. 10.1161/JAHA.121.024648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vinuesa V, McConnell MJ. Recent advances in Iron Chelation and Gallium-based therapies for antibiotic resistant bacterial infections. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(6):2876. 10.3390/ijms22062876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tan LTH, Chan KG, Khan TM et al. Streptomyces sp. MUM212 as a Source of Antioxidants with Radical Scavenging and Metal Chelating Properties. Front Pharmacol. 2017;8. Accessed May 19, 2023. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fphar.2017.00276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Caruffo M, Mandakovic D, Mejías M, et al. Pharmacological iron-chelation as an assisted nutritional immunity strategy against Piscirickettsia salmonis infection. Vet Res. 2020;51(1):134. 10.1186/s13567-020-00845-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Imlay JA. Cellular defenses against superoxide and hydrogen peroxide. Annu Rev Biochem. 2008;77:755–76. 10.1146/annurev.biochem.77.061606.161055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tan LTH, Lee LH, Yin WF, et al. Traditional uses, Phytochemistry, and Bioactivities of Cananga odorata (Ylang-Ylang). Evid-Based Complement Altern Med ECAM. 2015;2015:896314. 10.1155/2015/896314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tang C, Hoo PCX, Tan LTH, et al. Golden Needle mushroom: a Culinary Medicine with Evidenced-based Biological activities and Health promoting Properties. Front Pharmacol. 2016;7:474. 10.3389/fphar.2016.00474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xu J. Bioactive natural products derived from mangrove-associated microbes. RSC Adv. 2014;5(2):841–92. 10.1039/C4RA11756E. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sajjad W, Ahmad M, Khan S, et al. Radio-protective and antioxidative activities of astaxanthin from newly isolated radio-resistant bacterium Deinococcus sp. strain WMA-LM9. Ann Microbiol. 2017;67(7):443–55. 10.1007/s13213-017-1269-z. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang P, Omaye ST. Beta-carotene and protein oxidation: effects of ascorbic acid and alpha-tocopherol. Toxicology. 2000;146(1):37–47. 10.1016/s0300-483x(00)00160-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shah A, Eguchi T, Mayumi D, et al. Purification and properties of novel aliphatic-aromatic co-polyesters degrading enzymes from newly isolated Roseateles depolymerans strain TB-87. Polym Degrad Stab. 2013;98:609–18. 10.1016/j.polymdegradstab.2012.11.013. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ahsan T, Chen J, Zhao X, Irfan M, Wu Y. Extraction and identification of bioactive compounds (eicosane and dibutyl phthalate) produced by Streptomyces strain KX852460 for the biological control of Rhizoctonia Solani AG-3 strain KX852461 to control target spot disease in tobacco leaf. AMB Express. 2017;7(1). 10.1186/s13568-017-0351-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Harborne JB. Phytochemical Methods. Springer Netherlands; 1984. 10.1007/978-94-009-5570-7

- 26.Ahmed M, Ji M, Sikandar A, et al. Phytochemical Analysis, biochemical and Mineral composition and GC-MS profiling of Methanolic Extract of Chinese Arrowhead Sagittaria trifolia L. from Northeast China. Molecules. 2019;24(17):3025. 10.3390/molecules24173025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cho EJ, Yokozawa T, Rhyu DY, Kim SC, Shibahara N, Park JC. Study on the inhibitory effects of Korean medicinal plants and their main compounds on the 1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl radical. Phytomedicine Int J Phytother Phytopharm. 2003;10(6–7):544–51. 10.1078/094471103322331520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Auwal MS, Saka S, Mairiga IA, Sanda KA, Shuaibu A, Ibrahim A. Preliminary phytochemical and elemental analysis of aqueous and fractionated pod extracts of Acacia nilotica (Thorn mimosa). Vet Res Forum Int Q J. 2014;5(2):95–100. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Raghava Rao KV, Mani P, Satyanarayana B, Raghava Rao T. Purification and structural elucidation of three bioactive compounds isolated from Streptomyces coelicoflavus BC 01 and their biological activity. 3 Biotech. 2017;7(1):24. 10.1007/s13205-016-0581-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Supriady H, Kamarudin MNA, Chan CK, Goh BH, Kadir HA. SMEAF attenuates the production of pro-inflammatory mediators through the inactivation of akt-dependent NF-κB, p38 and ERK1/2 pathways in LPS-stimulated BV-2 microglial cells. J Funct Foods. 2015;17:434. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xu J, Chen S, Hu Q. Antioxidant activity of brown pigment and extracts from black sesame seed (Sesamum indicum L). Food Chem. 2005;91:79–83. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2004.05.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Haro Vicente J, martinez graciá C, Ros G. Optimisation of in vitro measurement of available iron from different fortificants in citric fruit Juices. Food Chem. 2006;98:639–48. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2005.06.040. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mosmann T. Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. J Immunol Methods. 1983;65(1–2):55–63. 10.1016/0022-1759(83)90303-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schröter MA, Meyer S, Hahn MB, Solomun T, Sturm H, Kunte HJ. Ectoine protects DNA from damage by ionizing radiation. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):15272. 10.1038/s41598-017-15512-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tian B, Sun Z, Shen S, et al. Effects of carotenoids from Deinococcus radiodurans on protein oxidation. Lett Appl Microbiol. 2009;49(6):689–94. 10.1111/j.1472-765X.2009.02727.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Daly MJ, Gaidamakova EK, Matrosova VY, et al. Small-molecule antioxidant proteome-shields in Deinococcus radiodurans. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(9):e12570. 10.1371/journal.pone.0012570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dutra RP, Abreu BV, de Cunha B. Phenolic acids, hydrolyzable tannins, and antioxidant activity of geopropolis from the stingless bee Melipona fasciculata Smith. J Agric Food Chem. 2014;62(12):2549–57. 10.1021/jf404875v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cherrak SA, Mokhtari-Soulimane N, Berroukeche F, Bensenane B, Cherbonnel A, Merzouk H, Elhabiri M. In vitro antioxidnt versus metal ion chelating properties of flavonoids: a structure-activity investigation. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(10):e0165575. 10.1371/journal.pone.0165575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sun L, Jin H, yu, Tian R et al. tao,. A simple method for HPLC retention time prediction: linear calibration using two reference substances. Chin Med. 2017;12:16. 10.1186/s13020-017-0137-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40.Kochhar N, Shrivastava S, Ghosh A, Rawat VS, Sodhi KK, Kumar M. Perspectives on the microorganism of extreme environments and their applications. Curr Res Microb Sci. 2022;3:100134. 10.1016/j.crmicr.2022.100134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Albrecht M, Takaichi S, Steiger S, Wang ZY, Sandmann G. Novel hydroxycarotenoids with improved antioxidative properties produced by gene combination in Escherichia coli. Nat Biotechnol. 2000;18:843–6. 10.1038/78443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu SP, Mao J, Liu YY, et al. Bacterial succession and the dynamics of volatile compounds during the fermentation of Chinese rice wine from Shaoxing region. World J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2015;31(12):1907–21. 10.1007/s11274-015-1931-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bondet V, Brand-Williams W, Berset C. Kinetics and mechanisms of antioxidant activity using the DPPH.Free Radical Method. LWT - Food Sci Technol. 1997;30(6):609–15. 10.1006/fstl.1997.0240. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhao Z. Iron and oxidizing species in oxidative stress and Alzheimer’s disease. Aging Med. 2019;2(2):82–7. 10.1002/agm2.12074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sharma P, Dutta J, Thakur D. Future prospects of actinobacteria in health and industry. In New and Future Developments in Microbial Biotechnology and Bioengineering 2018;305–324). Elsevier. 10.1016/b978-0-444-63994-3.00021-7

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The 16 S rRNA sequence data has been submitted to GenBank/DDBJ/ENA under accession no PP494735.