Abstract

We produced transgenic mice expressing the sheep prion protein to obtain a sensitive model for sheep spongiform encephalopathies (scrapie). The complete open reading frame, with alanine, arginine, and glutamine at susceptibility codons 136, 154, and 171, respectively, was inserted downstream from the neuron-specific enolase promoter. A mouse line, Tg(OvPrP4), devoid of the murine PrP gene, was obtained by crossing with PrP knockout mice. Tg(OvPrP4) mice were shown to selectively express sheep PrP in their brains, as demonstrated in mRNA and protein analysis. We showed that these mice were susceptible to infection by sheep scrapie following intracerebral inoculation with two natural sheep scrapie isolates, as demonstrated not only by the occurrence of neurological signs but also by the presence of the spongiform changes and abnormal prion protein accumulation in their brains. Mean times to death of 238 and 290 days were observed with these isolates, but the clinical course of the disease was strikingly different in the two cases. One isolate led to a very early onset of neurological signs which could last for prolonged periods before death. Independently of the incubation periods, some of the mice inoculated with this isolate showed low or undetectable levels of PrPsc, as detected by both Western blotting and immunohistochemistry. The development of experimental scrapie in these mice following inoculation of the scrapie infectious agent further confirms that neuronal expression of the PrP open reading frame alone is sufficient to mediate susceptibility to spongiform encephalopathies. More importantly, these mice provide a new and promising tool for studying the infectious agents in sheep spongiform encephalopathies.

Transmissible spongiform encephalopathies are degenerative diseases of the central nervous system and include human Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease and animal diseases, such as scrapie in sheep and goats and bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE) in cattle. One of the main characteristics of these encephalopathies is the accumulation in the brain of a pathological protein, the insoluble and partly protease-resistant prion protein (PrPres or PrPsc) (24). PrPsc is a posttranslationally modified isoform of a soluble and protease-sensitive host protein (PrPsen or PrPc) (3, 4, 9, 24). The development of spongiform encephalopathies requires the presence of PrPc, as demonstrated by the fact that PrP knockout mice remained healthy after inoculation with mouse prions (7). According to the protein-only hypothesis, PrPsc is the only component of the infectious agent involved in disease transmission (24).

Disease transmission between different species, if it occurs, is generally characterized by prolonged incubation periods, interpreted as a species barrier phenomenon. Transgenic mice expressing different PrP protein sequences have shown that differences in PrP sequences between species have a major role in resistance to the onset of disease during transmission through different species. Mice, for example, became susceptible to hamster prions when they expressed the Syrian hamster prion gene (27). Moreover, transgenic mice showed that the disease incubation time was inversely proportional to the level of PrP protein produced in the host brain (25).

The existence of multiple strains of prions leading to different behavior (incubation periods, distribution of brain lesions) in mice has been difficult to accommodate with the protein-only hypothesis. Several scrapie strains have, in fact, been characterized from natural scrapie isolates following serial passage in mice (6). Nevertheless, the success rate of mouse transmission from natural scrapie isolates varied enormously, with some mice presenting no clinical disease or pathology throughout their entire life span and some leading to clinical disease but only after very long incubation periods (6). Since transgenic mice for human, bovine, hamster, and murine PrP have been shown to propagate the infectious agent from these species, thus avoiding the species barrier problem, further studies would therefore require transgenic mice expressing sheep PrP. Until now, no transgenic mice expressing the ovine PrP gene that allowed transmission of natural scrapie isolates have been described. The transmission of natural scrapie has only been reported in transgenic mice expressing the bovine PrP gene (29). However, such mice necessarily produced prions with bovine PrP primary structure, with a requirement for transconformation between PrP characterized by different primary sequences.

We report here the successful transmission of two different natural scrapie isolates in transgenic mice that specifically express the ovine PrP gene in the brain, under the control of the neuron-specific enolase. Our study thus undoubtedly provides a new and promising tool for studies of the infectious agent in a species commonly affected by natural scrapie, but for which possible contamination by the BSE agent under natural conditions is also feared.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Generation of transgenic mice.

To generate the required transgenic mice, the 768-bp complete PrP open reading frame (ORF) was amplified by PCR using genomic DNA from the brain of a scrapie infected sheep and specific primers (5′ GAATTCCATGGTGAAAAGCC 3′ and 5′ AGGAAGGTTGCCCCTA 3′), as in the ovine sequence described by Goldmann et al. (12). Sequencing of the fragment demonstrated the ovine PrP sequence with alanine, arginine, and glutamine (PrP ARQ) at codons 136, 154, and 171, respectively, which are mainly involved in susceptibility to natural scrapie (10, 12, 16, 18). The amplified fragment was inserted into the pNSE-Ex4 vector by using HindIII adapter sequences (kindly provided by M. Oldstone, Scripps Research Institue, La Jolla, Calif. [26]). The resulting vector was digested by Sal1 to remove any prokaryote sequences and to produce the purified DNA fragment shown in Fig. 1. This fragment was used to generate transgenic mice by microinjection into the pronuclei of OF1 ovocytes following the usual methods (15). The transgenic mice were identified by digesting 10-day-old mouse tail DNA with EcoRI, which cut the transgene at two sites to give a 0.8-kb fragment corresponding to the ORF. Southern blot analysis was performed using a randomly labeled DNA probe synthesized from the purified HindIII fragment using [α-32P]dCTP and Ready To Go DNA labeling beads (Pharmacia Biotech).

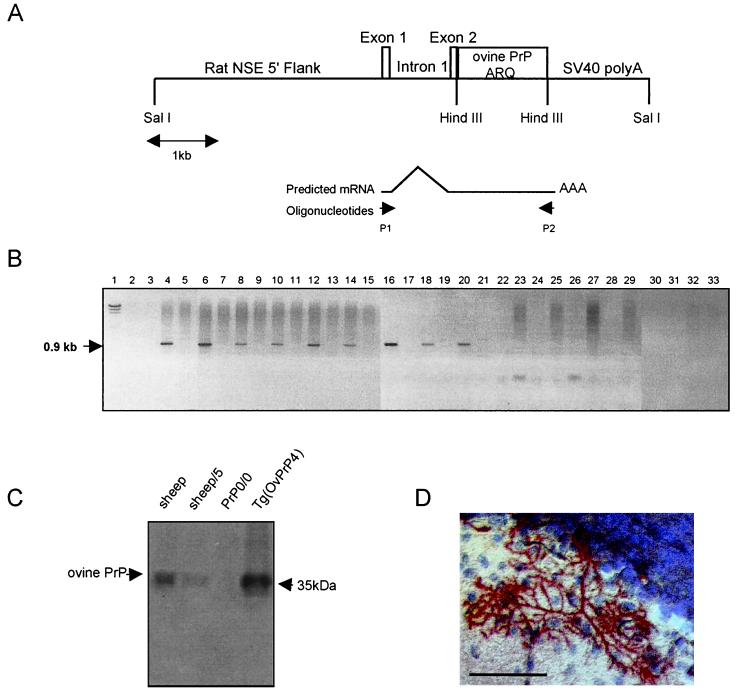

FIG. 1.

Structure of the neuron-specific enolase promoter OvPrP and predicted mRNA. (A) The ovine PrP ORF was inserted downstream from the neuron-specific enolase promoter of rat. Probes used for RT-PCR, named P1 and P2, are indicated by brown arrows just under the predicted mRNA. SV40, simian virus 40. (B) RT-PCR analysis of PrP mRNA in the brain. Lane 1, lambda HindIII marker; lane 2, sample without RNA; lane 3, total brain mRNA without reverse transcriptase; lanes 4 and 5, total brain mRNA; lanes 6 and 7, hippocampus mRNA; lanes 8 and 9, frontal cortex mRNA; lanes 10 and 11, mesencephalon mRNA; lanes 12 and 13, cerebellum mRNA; lanes 14 and 15, brain stem mRNA; lanes 16 and 17, thalamus mRNA; lanes 18 and 19, olfactory bulb mRNA; lanes 20 and 21, eye mRNA; lanes 22 and 23, spleen mRNA; lanes 24 and 25, heart mRNA; lanes 26 and 27, lung mRNA; lanes 28 and 29, muscle mRNA; lanes 30 and 31, intestine mRNA; lanes 32 and 33, liver mRNA. From lane 4 and on, mRNA were from Tg(OvPrP4) mice in even-numbered lanes and from PrP knockout mice in odd-numbered lanes. No band was observed in the blanks (lane 2) or in the control without reverse transcriptase (lane 3) or in Prn-P-/- mice. A 0.9-kb band was present in each sample related to brain and eye tissue of Tg(OvPrP4) mice (lanes 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 14, 16, and 18) but not in non-nervous tissue (lanes 20, 22, 24, 26, 28, 30, and 32). (C) Western blot analysis of brain homogenate (13 mg) from sheep, PrP knockout mice, and Tg(OvPrP4) mice. PrP was detected (by the presence of a 33- to 35-kDa band) with 4F2 monoclonal antibody (1:20,000 dilution) in sheep brain and Tg(OvPrP4) mice. No band was visible for PrP knockout mice. (D) Immunohistochemical detection of the ovine PrP protein showing a fine PrP labeling in neurons of the cerebellum, more precisely in the Purkinje cells, redrawing cell processes. Bar, 50 μm.

The transgenic founders were crossed with PrP knockout mice (kindly provided by C. Weissmann, University of Zürich—Switzerland) to obtain homozygous mice for both the transgene and the deleted locus (8).

The transgenic mice were cared for and housed in an autonomous filtered, pressurized enclosure according to the guidelines of the French Ethical Committee (Decree 87-848) and European Community Directive 86/609/EEC.

mRNA analysis by reverse transcription (RT)-PCR.

Total RNA was extracted from different organs (eyes, spleen, heart, liver, lung, spleen muscle, and intestine) and from different regions of the brain (thalamus, hippocampus, frontal cortex, mesencephalon, cerebellum, brain stem, and olfactory bulbs) using the Trizol extraction kit (Gibco).

RT was performed on 1 μg of total RNA in 7 μl of water, heated at 70°C for 10 min and added with 14 μl of polymerization mix (Promega buffer; 1.5 mM each Promega deoxynucleoside triphosphate, RNasin, Promega murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase, and Promega random primers), after which the mixture was incubated for 2 h at 37°C. PCR was performed using 0.6 U of Goldstar thermostable polymerase (Eurogentech), 100 ng of oligonucleotides specific for the transgene P1 (5′ CGGCTGAGTCTGCAGTCCTC 3′) corresponding to the 3′ end of the neuron-specific enolase promoter exon 1 and P2 (5′ ATAGATCTAAGCTTCTATCCTACTATGAGAAA 3′) corresponding to the 3′ end of the PrP ORF, and 1 μl of RT mix in a final volume of 50 μl. Thirty amplification cycles were performed at an annealing temperature of 55°C. The PCR products were separated on an agarose gel (1%).

Western blot analysis. (i) Extraction of cellular PrP.

The ovine cellular PrP protein in tissues of transgenic mice was detected by immunoblotting, and total proteins were extracted using the Trizol extraction kit (Gibco).

(ii) Extraction of PrPres.

The protease-resistant protein PrPres was extracted by homogenizing brain tissue in a 5% glucose solution (10%, wt/vol). The homogenates were forced through a 0.4-mm diameter needle before treatment at 37°C for 1 h with 10 μg of proteinase K (Boehringer)/100 mg of tissue. After the addition of N-lauroylsarkosyl (Sigma) to give a final concentration of 10%, samples were incubated for 15 min at room temperature and then centrifuged at 245,000 × g for 4 h on a 10% sucrose cushion (Beckman TL 100 ultracentrifuge). The pellets were finally resuspended in 30 μl of denaturing buffer (4% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 2% β-mercaptoethanol, 192 mM glycine, 25 mM Tris, and 5% sucrose), heated for 5 min at 100°C, and recentrifuged at 12,000 × g for 15 min at 20°C. Finally, the pellets were discarded and the supernatants were run on a sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel.

(iii) Western blotting procedures.

The proteins were separated on 15% polyacrylamide gels and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Bio-Rad) using a 25 mM Tris, 192 mM glycine, 10% isopropanol transfer buffer at 400 mA constant for 1 h. For immunoblotting, the membranes were blocked with 5% nonfat dried milk in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)-Tween 20 (PBST) (0.1%) and then incubated for 1 h at room temperature with monoclonal 4F2 antibody directed against 79-92 human PrP sequence (1:20,000 dilution) (kindly provided by J. Grassi, CEA/SPI, Saclay, France) (17) for the cellular PrP or rabbit antiserum RB1 raised against synthetic bovine 98–113 PrP peptide for the abnormal proteinase K-resistant protein as previously described (1:2,500 dilution) (21). The membranes were then washed twice in PBST (0.1%) and then incubated in a 1:2,500 dilution of peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (Southern Biotechnology Associates) in PBST (0.1%) or a 1:400 dilution of peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse or anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (Biosys) in PBST (0.1%) for 30 min at room temperature. The blots were finally washed in PBST (0.1%) (three times) and PBS (once), and the bound antibodies were detected using a chemiluminescent substrate of peroxidase (ECL [Amersham] or Supersignal [Pierce]) and visualized either onto films (Biomax Light; Kodak) or directly in an image analysis system (Fluor S MultiImager; Bio-Rad).

Immunohistochemical analysis. (i) Cellular PrP.

Adult (1 to 6 months old) transgenic mice brains were used for immunohistochemical analysis after being fixed in paraformaldehyde in PBS (0.1 M, pH 7.4) for one night at 4°C. The brains were dehydrated through graded alcohols and embedded in paraffin. Five-micrometer sections were collected onto pretreated glass slides (Polylysin or StarFrost; Fischer Scientific) and baked overnight at 57°C. The slides were then dewaxed and washed in PBS (0.1 M) and further treated with proteinase K (20 μg/ml; Roche-Boehringer) for 10 min at 37°C. All later steps were performed at room temperature (22 to 24°C). Endogenous peroxidase activity was inhibited with 2% H2O2 (Merck) in PBS (0.1 M) for 5 min. Nonspecific antigenic sites were blocked by a 30-min incubation in blocking reagent (Roche-Boehringer). Antibody 4F2 (1 μg/ml) was then applied overnight. The brain sections were rinsed before detection of the primary antibody using the ABC system (Vector). These steps were followed by rinsing the sections in PBS (0.1 M), and the peroxidase was finally revealed by incubating the sections in PBS (0.1 M) containing aminoethylcarbazole (AEC; Dako) to give a red deposit. The slides were weakly counterstained with aqueous hematoxylin mounting (GelMount).

(ii) Detection of abnormal PrP in scrapie-inoculated transgenic mice.

The above protocol was preceeded by pretreatments designed to destroy the normal cellular PrP. These treatments consisted of a formic acid treatment (98%; Merck) for 10 min at room temperature and 120°C for 30 min in water, each step being followed by a 5-min rinse in water. We also replaced the 4F2 monoclonal antibody with the SAF84 monoclonal antibody recognizing the human 142-160 PrP sequence (0.5 μg/ml) (kindly provided by J. Grassi), which appeared more appropriate for detection of PrPsc in immunohistochemistry.

Animal inoculation and follow-up.

The transgenic mice and the C57BL/6 mice used as controls (IFFA-CREDO, L'Arbresle, France) (4 to 6 weeks old) were inoculated intracerebrally with 20 μl of a 10% (wt/vol) solution of brain homogenate in glucose (5%) from two naturally scrapie-affected sheep from two different regions in France detected by the French Epidemiological Surveillance Network (D. Calavas, AFSSA-Lyon, Lyon, France). The amino acid changes of these sheep were AV136 RR154 QQ171 and AA136 RR154 QQ171 for isolates 1 and 2, respectively. The mice were then checked weekly for the presence of clinical signs, such as tremors, plastic tail, ruffled fur, abnormal gait, clasping feet, dorsal kyphosis, and leanness.

As soon as a mouse showed one of these clinical signs, it was isolated and monitored daily until death. Mice were sacrificed when the intensity of clinical symptoms appeared life threatening; in some cases they were found dead. The whole brain was quickly removed and sagittaly cut in two equal parts, one fixed (2% paraformaldehyde) for immunohistochemical analysis, the other frozen and stored at −80°C for Western blot analysis.

RESULTS

Generation and characterization of Tg(OvPrP4) mice.

The third 0.8-kb exon, containing the complete ORF of the ovine PrP, with alanine, arginine, and glutamine (PrP ARQ) at susceptibility codons 136, 154, and 171, respectively (12), was inserted downstream from the neuron-specific enolase promoter (Fig. 1A). The transgenic founders were identified by Southern blot analysis of 45 mice. These founders were crossed with PrP knockout mice to produce a mouse line [Tg(OvPrP4)] homozygous for both the transgene locus and the Prn-P deleted locus.

The Tg(OvPrP4) mice expressed the ovine PrP mRNA as shown by the presence of a 0.9-kb fragment corresponding to the predicted size of the amplified reverse-transcribed mRNA of the transgene (Fig. 1B). Ovine PrP mRNA was detected in all the brain areas studied (hippocampus, frontal cortex, mesencephalon, cerebellum, brain stem, and thalamus olfactory bulbs) and in the eyes but not in peripheral non-nervous organs, such as the spleen, heart, lung, muscle, gut, and liver (Fig. 1B).

The presence of the cellular ovine PrP protein (PrPc) was detected by Western blot analysis using the 4F2 monoclonal antibody as a single 33- to 35-kDa band in both transgenic mice and sheep (Fig. 1C). Image analysis showed that the quantity of ovine PrP protein remains two- to fourfold higher in the brains of Tg(OvPrP4) mice than in a normal sheep brain. Mouse brains were also analyzed by immunohistochemistry, using 4F2 monoclonal antibody, to study the cellular localization of ovine PrP. A neuronal localization of the ovine protein was observed with a high intensity essentially in the Purkinje cells, in which the staining consisted of fine deposits covering the cytoplasm of the cells and redrawing the dendritic extensions in the molecular cell layer of the cerebellum (Fig. 1D).

The Tg(OvPrP4) mice showed normal development. No spontaneous neurological sign was observed, even in some animals that stayed alive and healthy for more than 2 years.

Susceptibility of Tg(OvPrP4) mice to the scrapie agent.

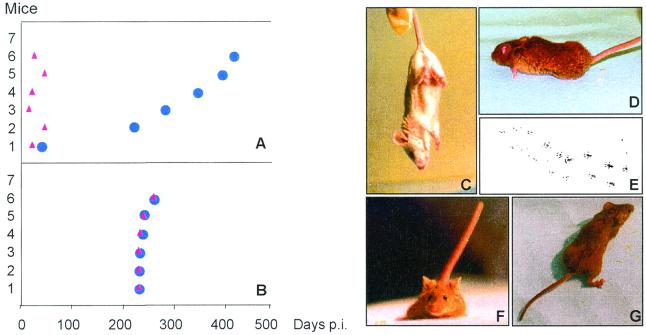

The susceptibility of Tg(OvPrP4) mice to the scrapie infectious agent was assessed by intracerebral inoculation of brain homogenates from two different isolates of scrapie-affected sheep, namely AV136 RR154 QQ171 and AA136 RR154 QQ171, designated isolates 1 and 2, respectively. Uninoculated Tg(OvPrP4) mice and nontransgenic C57BL/6 mice inoculated with isolate 1 or 2 remained healthy for more than 400 days postinoculation (p.i.) (Table 1). The transgenic mice died 290 ± 104 days p.i. (n = 6) and 238 ± 7 days p.i. (n = 6) after inoculation with isolates 1 and 2, respectively (Table 1). Mice inoculated with isolate 1 showed protracted clinical signs, the first symptoms occurring as early as 1 month p.i. (Fig. 2A). These clinical signs included tremors, foot clasping (Fig. 2C), dorsal kyphosis, ruffled fur (Fig. 2D), abnormal gait (Fig. 2E), plastic tail (Fig. 2F), and extension of the sustentation polygon (Fig. 2G). In contrast, the mice inoculated with isolate 2 did not show any clinical sign until 7.5 months p.i. and then showed the clinical symptoms described above, with rapid subsequent evolution so that the animals died or had to be sacrificed within 2 weeks (Fig. 2B).

TABLE 1.

Susceptibility of Tg(OvPrP4) mice to scrapie isolatesa

| Isolate (amino acid change) | First appearance of clinical signs (days p.i.) | Death (days p.i.) | Result ofb:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PrPres Western blot | PrPsc immunohistochemistry | Vacuolization | |||

| 1 (ARQ/VRQ) | 26 | 43 | − | − | No |

| 51 | 228 | +++ | +++ | Yes | |

| 19 | 288 | − | − | Yes | |

| 26 | 354 | +++ | +++ | Yes | |

| 51 | 404 | + | + | Yes | |

| 31 | 427 | + | nd | nd | |

| 29 | / | / | / | / | |

| 2 (ARQ/ARQ) | 230 | 231 | +++ | nd | nd |

| 230 | 231 | +++ | nd | nd | |

| 231 | 232 | +++ | +++ | Yes | |

| 232 | 238 | ++ | nd | nd | |

| 239 | 240 | +++ | +++ | Yes | |

| 259 | 260 | +++ | nd | nd | |

| / | / | / | / | / | |

Seven Tg(OvPrP4) mice were inoculated with isolate 1 and seven were inoculated with isolate 2. Two noninoculated Tg(OvPrP4) mice were used as controls; no spontaneous disease appeared and no death occurred until 500 days p.i. Twenty C57BL/6 mice were inoculated with isolate 1 or 2; no disease was developed until 400 days p.i.

nd, not determined (no fixed material); /, still alive; +, PrPsc present; −, no detectable PrPsc.

FIG. 2.

(A and B) Kinetics of the clinical signs (red triangles) and deaths (blue circles) of the animals inoculated with isolate 1 (A) or isolate 2 (B). (C through G) Clinical signs of Tg(OvPrP4) mice inoculated with sheep scrapie. Clinical signs shown are foot clasping (C), dorsal syphosis and abnormal fur (D), abnormal gait assessed by dipping back feet in ink (E), plastic tail (F), and extension of the sustentation polygon (G).

Accumulation of pathological PrPsc in the brain of Tg(OvPrP4) mice.

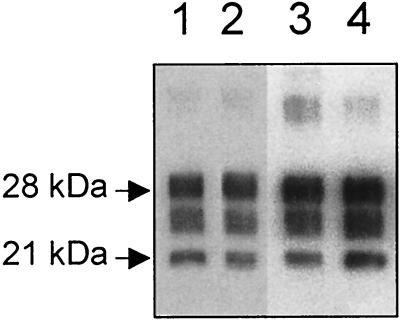

PrPsc accumulation was analyzed by both Western blot analysis of proteinase K-resistant protein and immunohistochemistry. Four out of the six mice inoculated with isolate 1 showed detectable levels of PrPsc (one of the negatives being the animal that died after 43 days) and six out of the six animals inoculated with isolate 2 (Table 1) showed detectable levels of PrPsc, with the three typical glycoforms of PrPsc being detected by RB1 antibody (Fig. 3). Comparison of the electrophoretical patterns between PrPsc from the sheep brain homogenate used for inoculation and PrPsc accumulated in the brain of Tg(OvPrP4) mice showed identical apparent molecular masses of unglycosylated PrPres (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Western blot analysis of protease-resistant PrP protein with RB1 polyclonal antibody comparing electrophoretical patterns of brain homogenate of isolate 1 (10 mg) (lane 1), of Tg(OvPrP4) mice inoculated with isolate 1 (12 mg) (lane 2), of isolate 2 (10 mg) (lane 3), and of Tg(OvPrP4) mice inoculated with isolate 2 (8 mg) (lane 4).

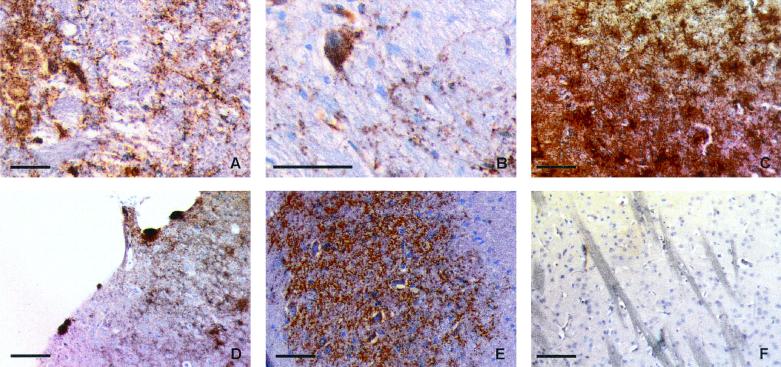

Immunohistochemical analysis using SAF84 monoclonal antibody revealed different patterns of PrPsc accumulation in the internal sagittal sections of brain from mice inoculated with isolate 1. We observed a parenchymatous staining in the brain stem (Fig. 4A), the cerebellar nuclei, and the dorsalis hypothalamus and a granular cytoplasmic accumulation in big neurons of the cerebellar stem (Fig. 4B). A stellate cytoplasmic pattern, redrawing the dendritic processes, was observed in the raphe area and colliculus (Fig. 4C), in the septum and caudate putamen, in isolated cells of the hippocampus, and in the IV layer of the cerebral cortex. A plaque-like accumulation was present in the cortex (Fig. 4D). No accumulation was observed in the very lateral sections. These patterns were characterized by distinct intensities in the different mice tested, ranging from a strong accumulation of PrPsc to a merely faint staining of the brain stem correlated with a negative or scarcely detectable signal in the Western blot analysis (Table 1).

FIG. 4.

Immunostaining of PrPsc with SAF84 monoclonal antibody on Tg(OvPrP4) mice inoculated with isolate 1 (A through D) or with isolate 2 (E) showing parenchymatous labeling in the brain stem (A) and cerebellum stem (E), granular cytoplasmic accumulation in big neurons of the cerebellar stem (B), stellate labeling of the dendritic processes (C), and plaque-like accumulation in the cortex (D). No labeling was detected in noninoculated Tg(OvPrP4) mice (F). Bar, 50 μm.

The accumulation patterns observed in the internal sagittal sections with isolate 2 were similar to the one observed for isolate 1, except for the cerebellum nuclei, where the staining was more intense (Fig. 4E), the raphe, where it was less intense, and the hippocampus, where there was no staining. The lateral sections revealed a cytoplasmic and dendritic accumulation in the neurons of the hippocampus and a granular accumulation of abnormal PrP in the Purkinje cells and in their processes in the cerebellum (data not shown). In noninfected Tg(OvPrP4) mice, no labeling was observed (Fig. 4F).

Neuropathology in Tg(OvPrP4) mice.

Spongiform changes and astrocyte proliferation were observed in the clinically sick Tg(OvPrP4) mice that died more than 200 days p.i. (Table 1). Limited astrogliosis was observed in the thalamic area of the two mice that died 43 days p.i., but while they showed clinical signs (Fig. 2C through G), there was no vacuolization.

In other animals, vacuolization was mainly identified in the cerebellum nuclei, mesencephalum, thalamus, hypothalamus, septum, and brain stem, with a more intense vacuolization in the brain stem with isolate 2 and in the cerebellum nuclei with isolate 1.

DISCUSSION

We have produced ovine PrP transgenic mice suitable for the detection of the sheep scrapie infectious agent. We demonstrate the transmission of two natural sheep scrapie isolates in these transgenic mice expressing the ovine prion protein in a neuron-specific manner. This was assessed by the development of neurological signs, spongiform changes, and accumulation of abnormal prion protein in the brain. Our results confirm that the neuron-specific expression of PrPc is sufficient to allow the development of spongiform encephalopathies, as has been shown in previous studies with the hamster PrP gene (26), and that PrPsc accumulation is not only correlated to the expression site of the PrPc gene (11, 26). Indeed, immunohistochemical analysis demonstrates that the cellular ovine PrP is strongly expressed in the Purkinje cells, which accumulate PrPsc after inoculation with isolate 2 but not with isolate 1. The levels of PrPc protein in these ovine transgenic mice were higher than those in sheep. Despite this, we never observed any spontaneous neurologic sign in uninoculated animals, as has been observed in previous attempts to produce sheep PrP transgenic mice (31).

The expected reduction of the species barrier regarding disease transmission occurred with these ovine PrP transgenic mice, as shown by mean incubation periods of 238 to 290 days after intracerebral inoculation of the sheep scrapie isolates, whereas C57BL/6 mice failed to develop clinical scrapie for at least 700 days with both isolates. Moreover, PrPsc accumulation is undetectable during the lifespan of these conventional mice, illustrating the necessity of using transgenic models in further studies. The transmission of natural scrapie isolates within transgenic animals had previously only been reported in transgenic mice that expressed the bovine PrP gene (29). Surprisingly, for these mice the mean incubation periods (203 to 245 days) were similar to those observed for our Tg(OvPrP4) mice and did not appear to differ significantly from those observed after inoculation of BSE isolates from cattle (217 to 265 days). Although other parameters may be important, the very high expression level of the bovine protein (4- to 16-fold higher than that in cattle) might explain these relatively short incubation periods observed for scrapie transmission (25, 28, 29), since there is an inverse relationship between incubation periods and PrPc expression in the brains of PrP transgenic mice (25, 29). Nevertheless, it has already been shown that strain characteristics may change by passage into a host with a different prion gene (30). Most scrapie strains originated from a pool of scrapie-infected Cheviot sheep brains but finally appeared distinct following a different passage history (2, 6). In addition, a unique donor PrPsc conformation could lead to multiple primary structures in a new species (30). In this context, the use of bovine PrP transgenic mice will not necessarily reflect the original scrapie properties, since there is an adaptation to the host species during the conversion. Ovine PrP transgenic mice seem more appropriate and are required to study natural scrapie diversity (29).

Unexpectedly, for isolate 1 we did not find any PrPsc detectable in two out of six mice, despite the fact that they were ill. In addition, the other mice accumulated PrPsc at different levels. Several studies on conventional mice (14, 19), transgenic mice (13, 22), and sheep (20) have already indicated a lack of correlation between the development of clinical signs and the levels of protease-resistant prion protein. In these other experimental murine models, some very low (22) or undetectable (19) levels of PrPsc were found when mice were inoculated with infected brain homogenates from other species, such as BSE from cattle (19) or human Gerstmann-Straüssler-Scheinker disease (22). In our case, the apparent absence of PrPsc could suggest that other forms of the prion protein that are protease sensitive may be involved in the disease. This possibility has been proposed to explain similar observations during serial passage of a mouse-adapted Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease strain with the early appearance but lagged accumulation of a detergent-insoluble, and protease-sensitive, form of the prion protein as early as 4 weeks p.i. and before the detection of PrPsc (23).

Our data already indicate that the two isolates analyzed displayed clearly distinct features. In particular, the incubation periods and clinical courses until death are quite different. Isolate 1 also showed an unusual development of the disease, with a very early onset of the first clinical signs that persisted for a very prolonged period, and these neurological signs did not threaten life for several weeks or even months. This behavior was observed in repeated experiments, even following the inoculation of previously heat-treated brain homogenates (data not shown). These behavioral differences may be related to the presence of different strains of scrapie in the two isolates. Whereas a number of scrapie strains could be isolated from sheep, and aside from the clinical and histopathological diversity of this disease in its natural host, scrapie strains have been defined through serial transmission into different species (6). The outcome of strain selection could depend on the kinetics of replication of the different agents in the case of a mixture of different strain-specific PrPsc conformations (1, 2). Serial passages from infected transgenic mice have to be performed in order to examine the stability of the features we have observed in our first-passage experiments. Besides the incubation period, this will allow further comparison of the sites, levels, and patterns of PrPsc accumulation with those observed during the first passage of the two isolates. The maintenance of these features would confirm that these Tg(OvPrP4) mice permit us to characterize natural scrapie strains.

The A136R154Q171 isolate used in this study, one of the most frequent in sheep flocks, is considered to be the ancestral allele in sheep, from which have been derived other genotypes, such as those encoding A136R154R171 or V136R154Q171 (12, 16, 18). This A136R154Q171 isolate is associated with an increased susceptibility to scrapie alleles (10, 12, 16, 18) and is thus relevant for studies of natural scrapie transmission in ovine transgenic mice. In vitro conversion experiments showed a less efficient conversion of ARQ PrPc in the presence of VRQ PrPsc than in the presence of ARQ PrPsc (5). In this study, the use of two genotypically different isolates from sheep, with AV136 and AA136 in isolates 1 and 2, respectively, may contribute to the differences in the behavior of the two isolates. Whether the strain diversity is associated to the initial PrP gene polymorphism present in sheep populations remains an open question.

Whereas several different prion strains have been identified from natural scrapie in sheep and goats following transmission in wild-type mice, further studies are required to analyze the behavior of a large number of different field scrapie isolates in transgenic mice expressing the ovine PrP protein. These mice should also permit evaluation of sheep infection with the BSE agent.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported in part by grants from the French Programme de Recherches sur les ESST et les Prions. Carole Crozet is financially supported by a grant from AFSSA: Agence Française de Sécurité Sanitaire des Aliments and from the Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale.

We thank Michèle Lavoine and Annie Kato for excellent technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Baron T G, Biacabe A G. Molecular analysis of the abnormal prion protein during coinfection of mice by bovine spongiform encephalopathy and a scrapie agent. J Virol. 2001;75:107–114. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.1.107-114.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bartz J C, Bessen R A, McKenzie D, Marsh R F, Aiken J M. Adaptation and selection of prion protein strain conformations following interspecies transmission of transmissible mink encephalopathy. J Virol. 2000;74:5542–5547. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.12.5542-5547.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Basler K, Oesch B, Scott M, Westaway D, Walchli M, Groth D F, McKinley M P, Prusiner S B, Weissmann C. Scrapie and cellular PrP isoforms are encoded by the same chromosomal gene. Cell. 1986;46:417–428. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90662-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Borchelt D R, Scott M, Taraboulos A, Stahl N, Prusiner S B. Scrapie and cellular prion proteins differ in their kinetics of synthesis and topology in cultured cells. J Cell Biol. 1990;110:743–752. doi: 10.1083/jcb.110.3.743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bossers A, deVries R, Smits M A. Susceptibility of sheep for scrapie as assessed by in vitro conversion of nine naturally occurring variants of PrP. J Virol. 2000;74:1407–1414. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.3.1407-1414.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bruce M. Strain typing studies of scrapie and BSE. In: Baker H, Ridley R M, editors. Prion diseases. Totowa, N.J: Humana Press; 1996. pp. 223–236. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Büeler H, Aguzzi A, Sailer A, Greiner R A, Autenried P, Aguet M, Weissmann C. Mice devoid of PrP are resistant to scrapie. Cell. 1993;73:1339–1347. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90360-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Büeler H, Fischer M, Lang Y, Bluethmann H, Lipp H P, DeArmond S J, Prusiner S B, Aguet M, Weissmann C. Normal development and behaviour of mice lacking the neuronal cell-surface PrP protein. Nature. 1992;356:577–582. doi: 10.1038/356577a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Caughey B W, Dong A, Bhat K S, Ernst D, Hayes S F, Caughey W S. Secondary structure analysis of the scrapie-associated protein PrP 27–30 in water by infrared spectroscopy. Biochemistry. 1991;30:7672–7680. doi: 10.1021/bi00245a003. . (Erratum, 30:10600.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clouscard C, Beaudry P, Elsen J-M, Milan D, Dussaucy M, Bounneau C, Schelcher F, Chatelain J, Launay J-M, Laplanche J-L. Different allelic effects of the codons 136 and 171 of the prion protein gene in sheep with natural scrapie. J Gen Virol. 1995;76:2097–2101. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-76-8-2097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.DeArmond S J, Mobley W C, DeMott D L, Barry R A, Beckstead J H, Prusiner S B. Changes in the localization of brain prion proteins during scrapie infection. Neurology. 1998;50:1271–1280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goldmann W, Hunter N, Foster J D, Salbaum J M, Beyreuther K, Hope J. Two alleles of a neural protein gene linked to scrapie in sheep. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:2476–2480. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.7.2476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hill A, Desbruslais M, Joiner S, Sidle K C L, Gowland I, Collinge J. The same prion strain causes vCJD and BSE. Nature. 1997;389:448–450. doi: 10.1038/38925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hill A F, Joiner S, Linehan J, Desbruslais M, Lantos P L, Collinge J. Species-barrier-independent prion replication in apparently resistant species. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:10248–10253. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.18.10248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hogan B, Beddington R, Costantini F, Lacy E. Manipulating the mouse embryo. A laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Plainview, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hunter N, Foster J D, Hope J. Natural scrapie in British sheep: breeds, ages and PrP gene polymorphisms. Vet Rec. 1992;130:389–392. doi: 10.1136/vr.130.18.389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Krasemann S, Groschup M, Hunsmann G, Bodemer W. Induction of antibodies against human prion proteins (PrP) by DNA-mediated immunization of PrP0/0 mice. J Immunol Methods. 1996;199:109–118. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(96)00165-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Laplanche J-L, Chatelain J, Westaway S, Thomas S, Dussaucy M, Brugère-Picoux J, Launay J-M. PrP polymorphisms associated with natural scrapie discovered by denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis. Genomics. 1993;15:30–37. doi: 10.1006/geno.1993.1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lasmézas C I, Deslys J-P, Robain O, Jaegly A, Beringue V, Peyrin J-M, Fournier J-G, Hauw J-J, Rossier J, Dormont D. Transmission of the BSE agent to mice in the absence of detectable abnormal prion protein. Science. 1996;275:402–405. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5298.402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Madec J, Groschup M H, Calavas D, Junghans F, Baron T. Protease-resistant prion protein in brain and lymphoid organs of sheep within a naturally scrapie-infected flock. Microb Pathog. 2000;28:353–362. doi: 10.1006/mpat.2000.0357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Madec J Y, Vanier A, Dorier A, Bernillon J, Belli P, Baron T. Biochemical properties of protease resistant prion protein PrPsc in natural sheep scrapie. Arch Virol. 1997;142:1603–1612. doi: 10.1007/s007050050183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Manson J C, Jamieson E, Baybutt H, Tuzi N L, Barron R, McConnell I, Somerville R, Ironside J, Will R, Sy M S, Melton D W, Hope J, Bostock C. A single amino acid alteration (101L) introduced into murine PrP dramatically alters incubation time of transmissible spongiform encephalopathy. EMBO J. 1999;18:6855–6864. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.23.6855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nakaoke R, Sakaguchi S, Atarashi R, Nishida N, Arima K, Shigematsu K, Katamine S. Early appearance but lagged accumulation of detergent-insoluble prion protein in the brains of mice inoculated with a mouse-adapted Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease agent. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2000;20:717–730. doi: 10.1023/A:1007054909662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Prusiner S B, Bolton D C, Groth D F, Bowman K A, Cochran S P, McKinley M P. Further purification and characterization of scrapie prions. Biochemistry. 1982;21:6942–6950. doi: 10.1021/bi00269a050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Prusiner S B, Scott M, Foster D, Pan K M, Groth D, Mirenda C, Torchia M, Yang S L, Serban D, Carlson G A, et al. Transgenetic studies implicate interactions between homologous PrP isoforms in scrapie prion replication. Cell. 1990;63:673–686. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90134-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Race R E, Priola S A, Bessen R A, Ernst D, Dockter J, Rall G F, Mucke L, Chesebro B, Oldstone M B. Neuron-specific expression of a hamster prion protein minigene in transgenic mice induces susceptibility to hamster scrapie agent. Neuron. 1995;15:1183–1191. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90105-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Scott M, Foster D, Mirenda C, Serban D, Coufal F, Walchli M, Torchia M, Groth D, Carlson G, DeArmond S J, et al. Transgenic mice expressing hamster prion protein produce species-specific scrapie infectivity and amyloid plaques. Cell. 1989;59:847–857. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90608-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Scott M R, Safar J, Telling G, Nguyen O, Groth D, Torchia M, Koehler R, Tremblay P, Walther D, Cohen F E, DeArmond S J, Prusiner S B. Identification of a prion protein epitope modulating transmission of bovine spongiform encephalopathy prions to transgenic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:14279–14284. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.26.14279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Scott M R, Will R, Ironside J, Nguyen H O, Tremblay P, DeArmond S J, Prusiner S B. Compelling transgenetic evidence for transmission of bovine spongiform encephalopathy prions to humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:15137–15142. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.26.15137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Scott R, Groth D, Tatzelt J, Torchia M, Tremblay P, DeArmond S, Prusiner S. Propagation of prion strains through specific conformers of the prion protein. J Virol. 1997;71:9032–9044. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.12.9032-9044.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Westaway D, DeArmond S J, Cayetano-Canlas J, Groth D, Foster D, Yang S L, Torchia M, Carlson G A, Prusiner S B. Degeneration of skeletal muscle, peripheral nerves, and the central nervous system in transgenic mice overexpressing wild-type prion proteins. Cell. 1994;76:117–129. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90177-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]