Keywords: coenzyme Q, CoQ, CoQ deficiency, mitochondrial disease, ubiquinone

Abstract

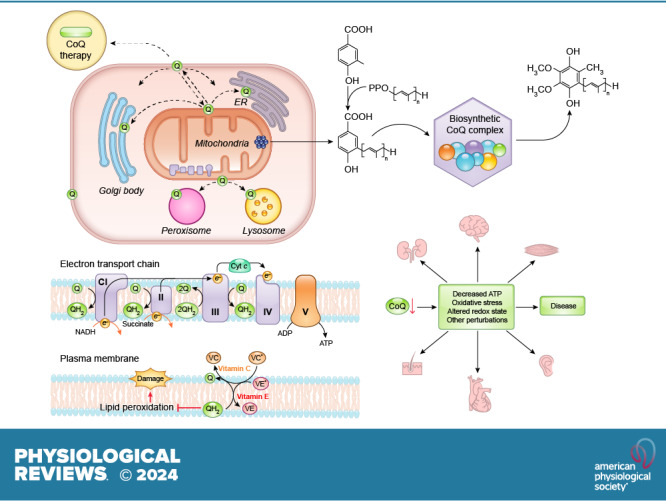

Coenzyme Q (CoQ), also known as ubiquinone, comprises a benzoquinone head group and a long isoprenoid side chain. It is thus extremely hydrophobic and resides in membranes. It is best known for its complex function as an electron transporter in the mitochondrial electron transport chain (ETC) but is also required for several other crucial cellular processes. In fact, CoQ appears to be central to the entire redox balance of the cell. Remarkably, its structure and therefore its properties have not changed from bacteria to vertebrates. In metazoans, it is synthesized in all cells and is found in most, and maybe all, biological membranes. CoQ is also known as a nutritional supplement, mostly because of its involvement with antioxidant defenses. However, whether there is any health benefit from oral consumption of CoQ is not well established. Here we review the function of CoQ as a redox-active molecule in the ETC and other enzymatic systems, its role as a prooxidant in reactive oxygen species generation, and its separate involvement in antioxidant mechanisms. We also review CoQ biosynthesis, which is particularly complex because of its extreme hydrophobicity, as well as the biological consequences of primary and secondary CoQ deficiency, including in human patients. Primary CoQ deficiency is a rare inborn condition due to mutation in CoQ biosynthetic genes. Secondary CoQ deficiency is much more common, as it accompanies a variety of pathological conditions, including mitochondrial disorders as well as aging. In this context, we discuss the importance, but also the great difficulty, of alleviating CoQ deficiency by CoQ supplementation.

CLINICAL HIGHLIGHTS.

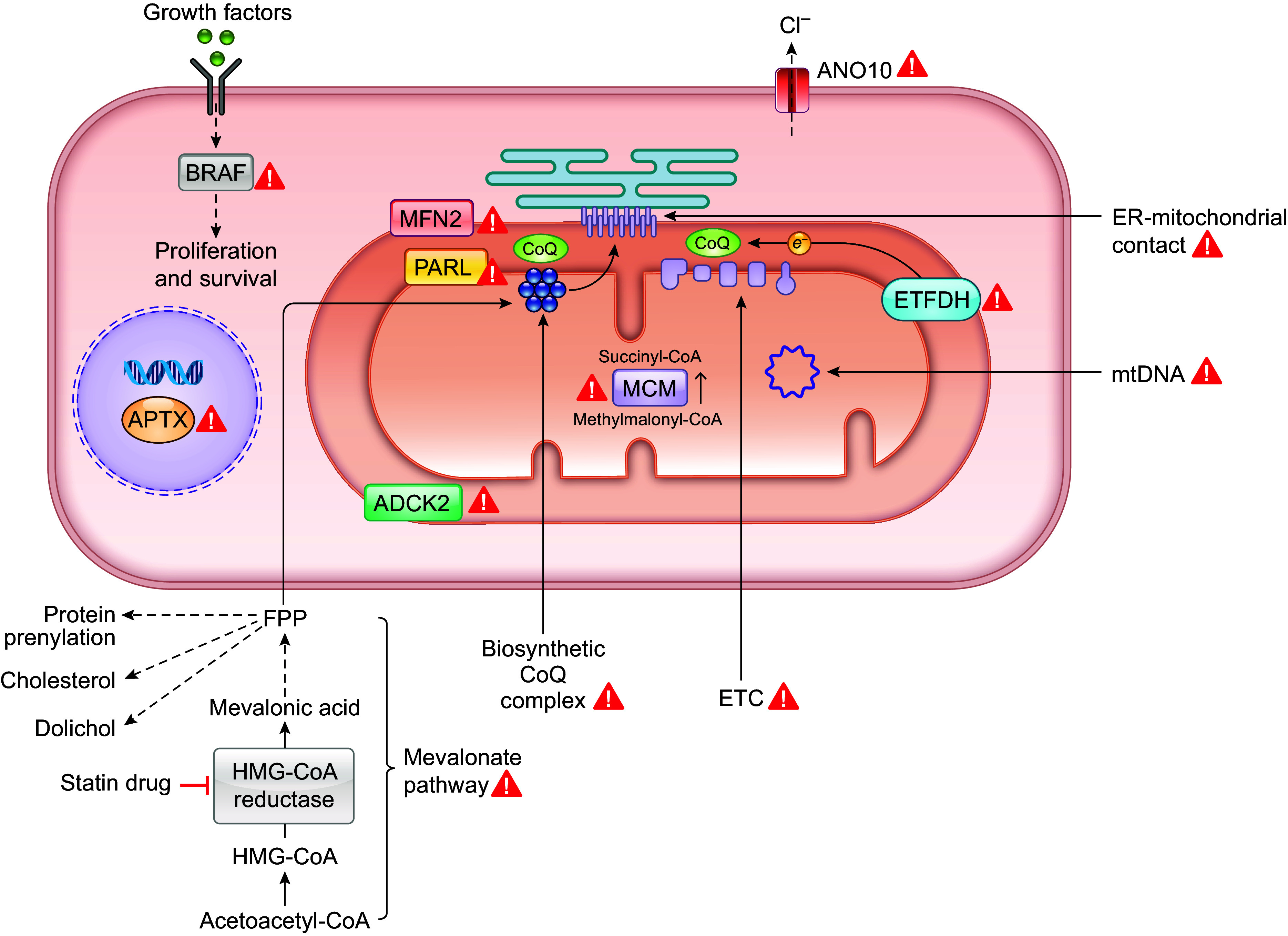

Coenzyme Q10 (CoQ10) was discovered more than half a century ago for its key role in mitochondrial respiration. It also participates in several other important cellular functions such as reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation during mitochondrial respiration, protection against oxidation of membrane lipids, and the redox balance of the cell. Mutations in the genes required for the biosynthesis of CoQ10 lead to primary CoQ10 deficiency (PCD) and present with heterogeneous clinical symptoms ranging from birth- or infantile-onset multisystem disorders to isolated symptoms involving single organs or systems. Overall, PCD frequently resembles mitochondrial disease syndromes. However, it is unknown whether the same pathophysiology underlies each symptom. For example, some studies in mice suggest that it is increased oxidative stress due to low CoQ, and not damaged mitochondrial function, that is responsible for renal symptoms. In addition to PCD, a variety of diseases and conditions have been found to be associated with secondary CoQ10 deficiency (SCD), which refers to all the conditions in which the etiology of the CoQ10 deficiency is not a molecular lesion in the CoQ10 biosynthetic pathway. These include mitochondrial disorders, multiple system atrophy, ataxia due to APTX mutations, mutations in ETFDH, and Parkinson’s disease. In addition to patients with documented CoQ10 deficiency and/or mutations of biosynthetic genes, CoQ10 is frequently recommended to mitochondrial disease patients as well as for treating a wide range of other conditions (e.g., heart failure and neurodegenerative diseases). Oral CoQ10 supplementation is the only currently available treatment option for CoQ10 deficiency. However, a recent systematic review of all PCD patients who have been treated with CoQ10 suggests that oral supplementation is virtually without effect, despite the fact that the lack of CoQ10 is the primary cause of these patients’ symptoms. Future research will be necessary to develop effective therapies to treat or prevent CoQ10 deficiency.

1. INTRODUCTION

Coenzyme Q (CoQ), also known as ubiquinone (UQ), is a lipophilic molecule that is essential for several distinct cellular processes, including energy production, and is thus essential for life. It is one of the most conserved molecules across all kingdoms of life. Frederick Crane and colleagues (1) at the Enzyme Institute of the University of Wisconsin in Madison first isolated it in 1957 from beef heart mitochondria as a yellow-orange lipophilic substance with redox properties, and it was proposed to function as a coenzyme for mitochondrial electron transfer. As such, it was given the name coenzyme Q. Its other name, ubiquinone, which was officially given to the substance in 1975 by the IUPAC-IUB Commission on Biochemical Nomenclature, refers to the fact that it has a ubiquitous presence from bacteria to humans.

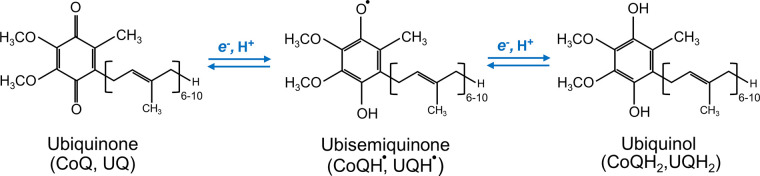

The chemical structure of CoQ was determined by Karl Folkers and coworkers at Merck. Its full chemical name is often given as 2,3-dimethoxy-5-methyl-6-multiprenyl-1,4-benzoquinone. Another possible formalism is 2-methyl-3-multiprenyl-5,6-dimethoxy-1,4-benzoquinone, which we are following in this review, including in the figures. CoQ is composed of a redox-active benzoquinone ring conjugated to an isoprenoid unbranched side chain whose length is species specific, ranging from 6 to 10 isoprenoid repeats (FIGURE 1). For example, in humans, the side chain is 10 isoprene subunits long and the molecule is therefore abbreviated as CoQ10. Rodents and Caenorhabditis elegans (C. elegans) mainly produce CoQ9, and Saccharomyces cerevisiae (S. cerevisiae) and Escherichia coli (E. coli) produce CoQ6 and CoQ8, respectively. Some species make more than one form of CoQ. For example, although CoQ9 is the main form in mice, small amounts of CoQ10 also occur in most tissues, with tissue-specific ratios of the two forms. Why different organisms have CoQ with varying side chain lengths is not understood. The CoQ benzoquinone ring is the functional group of the molecule, capable of reversible oxidation-reduction states without change in structure. The benzoquinone ring of quinone can exist in nine different redox states (2, 3). However, functionally there are three redox states of CoQ, that is, fully oxidized (CoQ, UQ), partially reduced (a semiquinone anion radical with a reactive unpaired electron, CoQ•−, UQ•−), and fully reduced (CoQH2, UQH2) (4, 5) (FIGURE 1). The redox chemistry of CoQ, which is able to accept/donate one or two electrons at a time, is at the core of its best-understood biological functions (6). The isoprenoid tail is responsible for the extreme hydrophobicity of CoQ and its solubility in membrane bilayers (6).

FIGURE 1.

Structure and redox states of coenzyme Q (CoQ). CoQ exists in 3 redox states: the fully oxidized form (CoQ) accepts 2 electrons to form CoQH2 or accepts 1 electron to form the ubisemiquinone intermediate, followed by acceptance of an additional electron to form CoQH2. The number of isoprene units in the tail varies between species from 6 to 10.

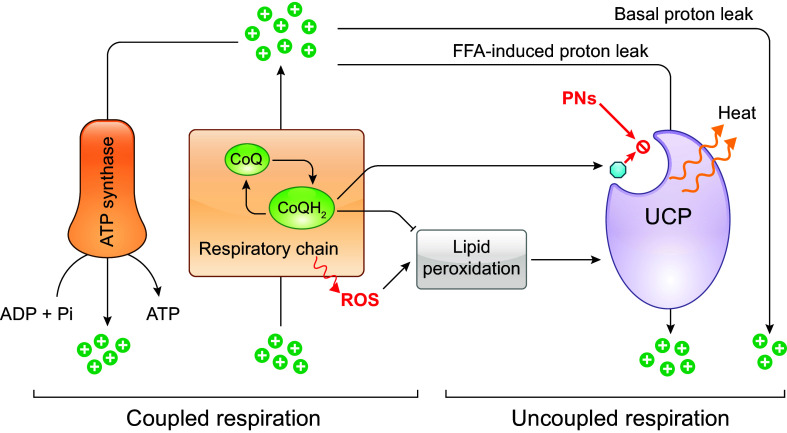

CoQ is likely found in all eukaryotic lipid membranes (7, 8). The best-known function of CoQ is to act as an electron carrier in the electron transport chain (ETC) in the inner membrane of mitochondria (IMM). In fact, mitochondria are the most enriched in CoQ among all subcellular compartments (9, 10). Other functions described for CoQ include participation in trans-plasma membrane electron transport, regulation of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore (mPTP), and activation of uncoupling proteins (UCPs), as well as an important dual role as pro- and antioxidant (7, 11–13). It has been proposed that CoQ may also play a role in the physicochemical properties of the lipid membranes in which it resides, but this is not yet well established or understood (14–23). In addition, new aspects of the function of CoQ are regularly reported. For example, a recent study suggests that the ratio of reduced to oxidized CoQ (CoQ/CoQH2) helps metabolic adaptation by acting as a sensor of the efficiency of the mitochondrial ETC (24). CoQ deficiency, no matter its cause, is currently defined as a decrease in the CoQ content in cells or organisms that can potentially impair many cellular functions, with mitochondria respiration expected to be the most vulnerable.

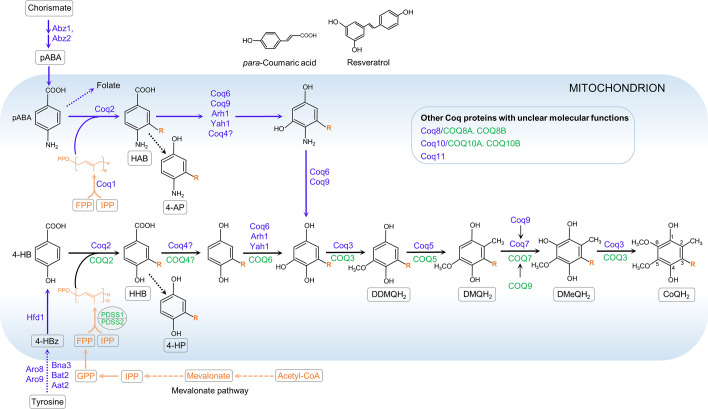

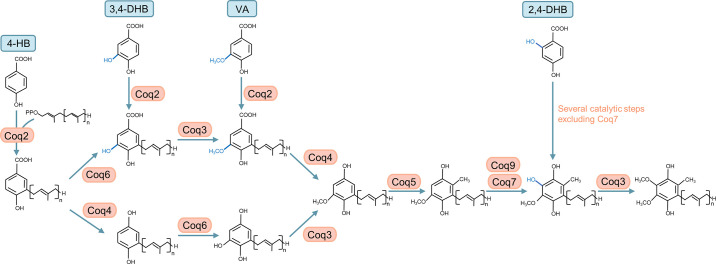

All cells rely on endogenous synthesis for their CoQ supply. CoQ biosynthesis is a complex and highly conserved pathway in which at least 10 proteins are involved. In eukaryotes, CoQ is synthesized from precursors in the IMM, from which it is then distributed to other subcellular compartments (25–27). To date, it is well established that several CoQ biosynthetic pathway components are recruited into a supramolecular complex that catalyzes sequential reactions that modify the aromatic ring (25–28). In animals, complete loss of CoQ biosynthesis is embryonic lethal in most species (8, 29–32). However, see the description in sect. 5.2 of the special case of clk-1 mutants of the nematode C. elegans, which can survive with a mixture of dietary CoQ and the CoQ biosynthetic intermediate demethoxyubiquinone (DMQ) (33–36). In humans, deleterious mutations in genes required for CoQ biosynthesis frequently cause severe multisystem disease due to impaired mitochondrial respiration (11, 26, 37–39). After diagnosis, the patients are generally treated with oral CoQ10 supplementation. Unfortunately, there is only very weak evidence for the efficacy of the treatment (40). Efforts are underway to develop methods for more effective CoQ10 delivery to overcome its extremely poor water solubility and limited oral bioavailability (41, 42). Moreover, in view of its essential role in mitochondrial respiration and its antioxidant capabilities, CoQ10 has been recommended to treat conditions with no evidence of CoQ10 deficiency as a causative factor, such as congestive heart failure, neurodegenerative diseases, cancer, and more (43). However, in our view, whether CoQ10 supplementation truly provides benefits to any type of patient remains in need of a clear demonstration.

2. THE FUNCTION OF CoQ AS MITOCHONDRIAL ELECTRON TRANSPORTER

2.1. Requirement of CoQ in Aerobic Respiration

After its discovery, the most crucial function that CoQ has been shown to perform is as an electron carrier in the mitochondrial ETC (44–46). This key function of CoQ became evident in the late 1960s when it was demonstrated that depletion of CoQ10 from beef heart submitochondrial particles (SMPs) by pentane extraction caused inhibition of both the NADH and succinate oxidase activities and that the activities were restored upon reconstitution of extracted SMPs with CoQ at physiological concentrations (47, 48).

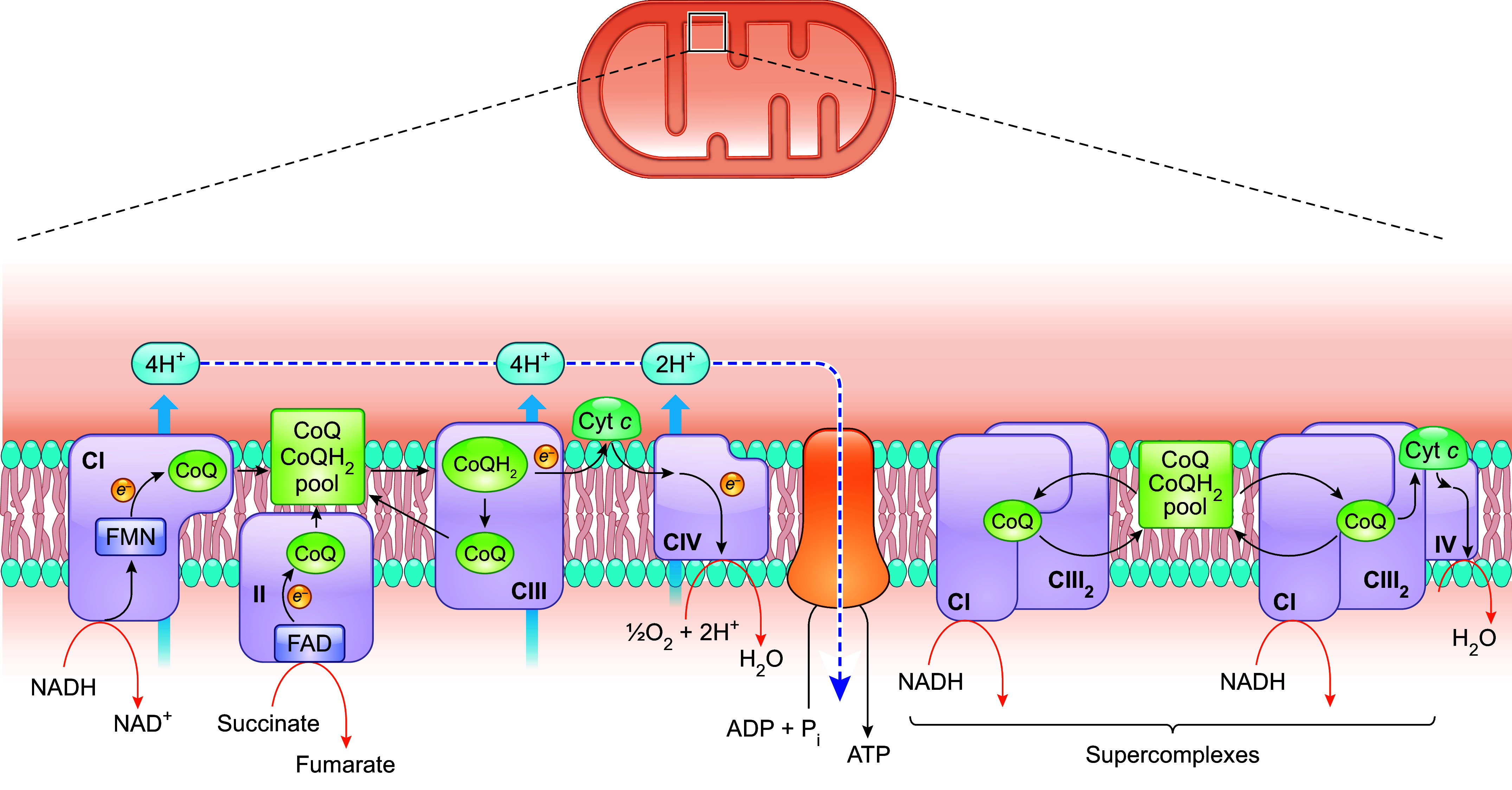

Mitochondrial complex I (CI) is the nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH)-CoQ oxidoreductase. Reduction of CoQ by electrons from CI is the last step of the electron transfers between sites across CI, which, as a whole, powers proton (H+) translocation across the IMM into the intermembrane space (FIGURE 2). CoQ also accepts electrons from complex II (CII is the succinate CoQ reductase), a process that does not translocate protons across the inner membrane directly but participates in respiratory chain function by increasing the size of the pool of reduced CoQ (CoQH2). CoQH2 resulting from electron transfer from CI and CII and other metabolic enzymes enters complex III (CIII is the cytochrome bc1 complex), where it transfers electrons to cytochrome c (cyt c) and thus becomes reoxidized (FIGURE 2). In CIII, CoQ undergoes the Q cycle (see below), whose net result is the translocation of 4 protons across the IMM for the full oxidation of each CoQH2 molecule (46). This ends the role of CoQ in electron transport and in creating the mitochondrial transmembrane potential and proton gradient (49).

FIGURE 2.

Functions of CoQ in the mitochondrial respiratory chain. CoQ is a pivotal component of the mitochondrial electron transport chain, acting as a mobile electron carrier shuttling electrons from CI and CII to CIII. During this process, CoQ cycles between reduced and oxidized states. In addition to moving randomly and colliding with CI and CII, CoQ is also present in CI- and CIII-containing respiratory supercomplexes (SCs), formed by the dynamic association of ETC complexes. In SCs, CIII is normally observed as a dimer (CIII2). All CoQ in the IMM likely behaves as a single functional pool, that is, CoQH2 can diffuse out of the CI and CIII assembled in SCs and become oxidized by CIII found outside of SCs. Conversely, CoQH2 generated independently of SCs can diffuse in, and be oxidized by, CIII attached to CI assembled in SCs. See glossary for other abbreviations.

It has been suggested that only 10–32% of total mitochondrial CoQ is bound to membrane proteins (50, 51). The classic liquid-state or random-collision model postulates that in the IMM there exists a bulk CoQ pool that is accessible to all the dehydrogenases that need to donate reducing equivalents to CoQ. In this model, CoQ diffuses freely within the lipid bilayer and electron transfer occurs after random collisions between CoQ and the enzymes that are themselves diffusing in the plane of the IMM, including the ETC complexes (52). This view, however, has been partially abandoned, after the discovery that individual ETC complexes can assemble into a variety of supramolecular structures known as supercomplexes (SCs) (53–57). The major SCs identified comprise CI/CIII2 (CI associated with a CIII dimer), CI/CIII2/CIV, and CIII2/CIV. The SC formed by CI, CIII2, and CIV is also known as the respirasome because, in principle, it has all the elements required to carry out respiration (53). There is evidence that molecules of CoQ are present in SC assemblies, more specifically in the lipid boundary between CI and CIII, and that the electron transfer between the two complexes occurs through CoQ trapped within (53, 58, 59). In fact, purified SCs (CI/CIII2 and CI/CIII2/CIV) were shown to be functional, being able to transfer electrons without the addition of any external CoQ (60).

One early hypothesis was that the purpose of SCs might be to mediate substrate channeling to enhance metabolic efficiency. This would mean that each SC sequesters its own subpopulation of the mobile electron carriers (CoQ and/or cytochrome c) and electron transfer between two sequential enzymes (CI-CIII and CIII-CIV) occurs by successive reduction and reoxidation of the mobile intermediates that are enclosed in internal channels connecting one enzyme active site to another (50, 61). Such channels would prevent the reaction intermediates from diffusing into the bulk membrane pool, thus minimizing the distance that the intermediates must travel between active sites, with an overall effect of increasing electron transport efficiency (50, 60). However, no robust evidence has yet been found that indicates the presence in SCs of confined spaces that connect active sites and retain mobile redox cofactors within (57, 62, 63). Rather, enzyme kinetic analyses and experiments where the addition of an alternative CoQH2 oxidase (AOX) to bovine heart mitochondrial membranes caused a substantial increase of the electron flux through the CI/CIII2/CIV suggest that there is no sealed-in CoQ pool in SCs (64, 65). AOX from plants directly oxidizes CoQH2, using oxygen (O2) as the terminal electron acceptor. The fact that it can compete with the CIII/CIV pathway for electrons indicates that it has access to the CoQH2 pool. In mammalian mitochondria, CI is shown to be mostly associated with other complexes in SCs (54). Therefore, if there is direct substrate channeling of CoQ in SCs, the presence of AOX outside of the SC structure should have a negligible effect on electron flux from CI to oxygen. The fact that the addition of AOX was found to increase the NADH oxidation rate suggests that CoQH2 can diffuse out of SCs to react with AOX (65). Furthermore, functional and structural characterization of mammalian SCs (from ovine heart mitochondria) demonstrated the existence of CoQ in three of four possible CoQ-binding sites in CI/CIII2 SCs: the two Qi sites and one of the two Qo sites of the two CIII. The study also showed that CoQ trapping in the SC actually reduces CI activity, which is also inconsistent with the substrate channeling hypothesis (59).

Even without direct channeling within SCs, the assembly of SCs could still decrease the traveling distance for the electron carriers and thus facilitate more efficient electron transfer (59, 66). As discussed in sect. 3.1, the ETC is the major site of ROS production in the cell. During respiration, electrons can escape from the ETC and be captured by molecular oxygen, thus generating superoxide (O2•−). CoQ in the ubisemiquinone state is known to be one of the sources of electron leakage. Overall, although the exact nature and role of SC formation are not yet clear, an often-accepted view is that it is beneficial. By facilitating electron transfer, it potentially increases respiration rate and lowers electron leakage to molecular oxygen, thus boosting OXPHOS efficiency and minimizing ROS generation (67, 68). Furthermore, a role in supporting the structural stability of the individual complexes has been proposed (56). Supporting evidence shows that respiratory activity is enhanced when more SCs are formed and an organism’s fitness is compromised when SCs formation is impaired (69–71).

As mentioned above, in mammalian mitochondria, it is believed that all or most of CI (≥90%) is associated with other complexes in SCs (54). Whether CII participates in any SC formation is still an open question (72). It has been proposed that, given the likelihood of free CoQ diffusion in and out of SCs, the overall electron flux through the ETC occurs by a mixture of electron transfer in SCs and random collision events between the two mobile electron carriers (CoQ and cyt c) and individual ETC complexes. This is consistent with data that show that all CoQ in the IMM (whether or not associated with SCs) behaves as a single functional pool (57, 59, 73). In other words, CI, CII, and other enzymes that deliver electrons to CoQ (see sect. 2.2) compete for the same CoQ pool (64, 74). However, it is worth noting that this is still a matter of controversy (50, 56, 65). Furthermore, as discussed further in sect. 2.3, CoQ deficiency is usually found to be associated with a partial loss of both CI- and CII-mediated respiration, which is not in support of the existence of two segregated CoQ pools.

2.2. Other Electron Transport Pathways That Deliver Electrons to Mitochondrial CoQ

In addition to the electrons that the two respiratory complexes CI and CII transfer to CoQ, it also receives electrons from at least seven other dehydrogenases that are associated with the IMM, either on the intermembrane space side or on the matrix side. These include 1) the mitochondrial glycerol 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (G3PDH), a part of the glycerophosphate shuttle (75), 2) the mitochondrial dihydroorotate dehydrogenase (DHODH), an enzyme involved in a key step in the production of pyrimidine nucleotides (76), 3) the electron transport flavoprotein dehydrogenase (ETFDH), a key enzyme of fatty acid β-oxidation and amino acid catabolism, 4) proline dehydrogenase (PRODH) and proline dehydrogenase 2 (PRODH2), both of which are involved in proline, glyoxylate, and arginine metabolism, 5) choline dehydrogenase (CHDH), which is primarily found in liver and kidney in humans and catalyzes the oxidation of choline to glycine betaine (77), and 6) sulfide-quinone oxidoreductase (SQOR), which is essential for detoxification of hydrogen sulfide (H2S) (78). Like CII, these dehydrogenases reduce flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD) to FADH2, which then transfers electrons to CoQ, but these processes are not coupled to proton translocation to the mitochondrial intermembrane space (IMS) because FADH2 and CoQ have similar reduction potentials and therefore these transfers do not result in a sufficiently large gain in Gibbs free energy to power proton translocation. To date, there is not much known about how tightly the rates at which these metabolic pathways function are linked to the level of CoQ in the IMM or whether an impact on these pathways contributes to the pathophysiology of CoQ deficiency. Below we briefly describe two of the enzymes whose activities have been reported to be affected by CoQ deficiency.

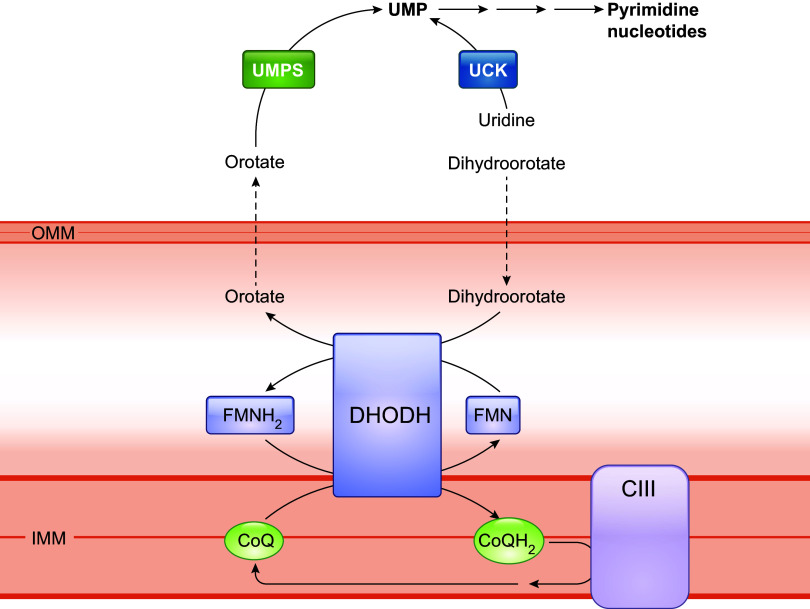

Eukaryotic cells devoid of mitochondrial DNA (ρ0) need supplementation with uridine to sustain viability. This is because DHODH, which catalyzes a crucial step in intracellular de novo pyrimidine biosynthesis (conversion of dihydroorotate to orotate), needs CoQ as a cofactor (FIGURE 3). The activity of DHODH is inhibited in ρ0 cells because of the loss of the ETC and the resultant lack of oxidized CoQ to which electrons can be transferred. Uridine is a downstream product of DHODH and therefore needs to be provided to ρ0 cells to compensate for the lack of endogenous pyrimidine biosynthesis, which is essential for RNA/DNA synthesis (76, 79). Uridine was reported to improve the growth rate of human COQ2 mutant fibroblasts that have <20% residual CoQ10, suggesting the possibility of a deficit of pyrimidine biosynthesis in these cells (80, 81). In contrast, no exogenous addition of uridine to the culture medium was needed for Pdss2/Coq7 double-knockout mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs), despite being completely devoid of detectable CoQ, and in fact these cells showed no sign of any growth defect under standard culture conditions in medium that contained sufficient glucose (82, 83). Normal culture medium contains a minimal amount of CoQ10. Thus, in contrast to ρ0 cells, Pdss2/Coq7 double-knockout cells sustain some ETC activity at an extremely low level despite a complete lack of CoQ biosynthesis (83). This low level of CoQ and respiratory function appears to allow for adequate pyrimidine synthesis, suggesting a very minimal requirement for mitochondrial respiratory function to maintain sufficient DHODH activity for cells to survive.

FIGURE 3.

CoQ is a cofactor for mitochondrial dihydroorotate dehydrogenase (DHODH). DHODH catalyzes the oxidation of dihydroorotate to orotate during the fourth step of the de novo biosynthesis of pyrimidine. The reaction is coupled to the reduction/oxidation of flavin mononucleotide (FMN) and CoQ. Orotate diffuses back to the cytosol to be converted by uridine monophosphate synthase (UPMS) to uridine 5-monophosphate (UMP), the precursor of all pyrimidine nucleotides. Preexisting uridine can be phosphorylated to UMP by uridine kinase (UCK), thereby bypassing the need for the DHODH-catalyzed step. See glossary for other abbreviations.

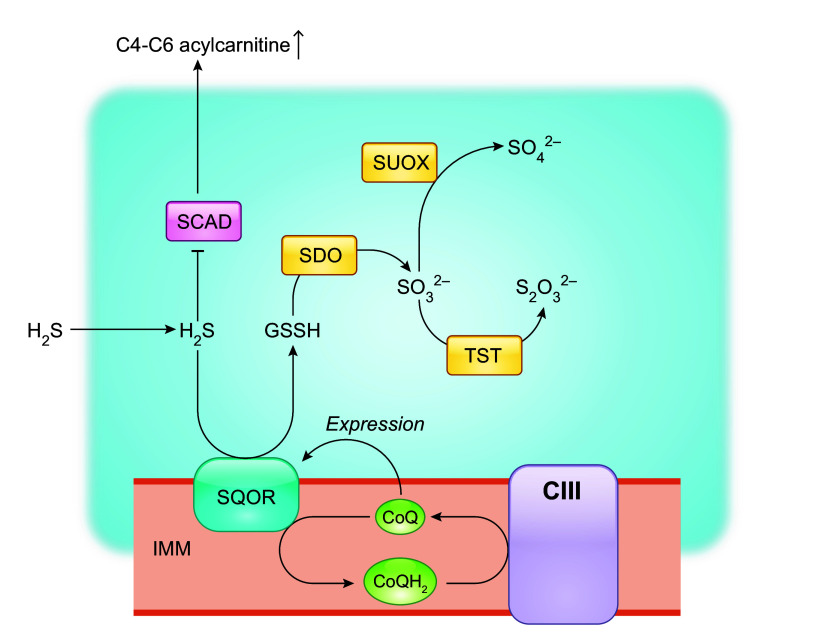

The IMM flavoprotein protein sulfide-quinone oxidoreductase (SQOR) is the first enzyme to act in the mitochondrial metabolism of hydrogen sulfide (H2S). It catalyzes two-electron oxidation of H2S and utilizes CoQ as the electron acceptor, thus coupling the reaction to CoQ in the ETC (84–86) (FIGURE 4). The oxidized sulfur is transferred to a small-molecule acceptor, which is predicted to be primarily glutathione (GSH) under physiological conditions (84). Glutathione persulfide (GSSH) produced by SQOR is converted to sulfite () which is further catabolized by thiosulfate sulfurtransferase (TST, also known as rhodanese) or sulfite oxidase (SUOX) to produce thiosulfate () or sulfate () (84). This sulfide oxidation pathway plays a key role in governing cellular H2S levels (85). H2S has toxic properties but also functions in regulating homeostasis as a cell signaling molecule (78). In human skin fibroblasts, a ≤50% reduction in CoQ10 levels was shown to cause an impairment of SQOR-driven oxygen consumption (87). Moreover, accumulation of H2S, a direct consequence of impaired sulfide oxidation, was reported for CoQ-deficient fission yeast and mouse tissues (87–89). Other abnormalities related to H2S accumulation include depletion of GSH, reduction of thiosulfate (), increased protein sulfhydration, and increased blood levels of C4-C6 acylcarnitines, consistent with inhibition of short-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase (SCAD), a known toxic effect of H2S (87, 89–91). Interestingly, among the mouse tissues examined, including the kidney, brain, and muscle, the kidney showed the most pronounced accumulation of H2S (87, 89). High levels of sulfide were observed in the kidney of two different CoQ9-deficient mouse models (Pdss2kd/kd and Coq9R239X) which have <15% residual CoQ9 levels, whereas in the cerebrum of Coq9R239X mice (with 10–15% residual CoQ9) and the whole brain of Pdss2kd/kd mice (with ≈30% residual CoQ9), the levels of sulfides were shown to be similar to those in wild-type control mice (87, 89). Somewhat surprisingly, CoQ deficiency decreases SQOR levels, worsening the effect on sulfide metabolism (87, 89, 90). Conversely, supraphysiological levels of CoQ10 (>2,300 fold!) were shown to upregulate SQOR expression in cultured skin fibroblasts, and a similar effect was observed in the liver of wild-type mice after supplementation with CoQ10H2 (92). Moreover, the amount of reduced SQOR in mutant HeLa cells with ≈50% residual CoQ10 was shown to be elevated after CoQ10 supplementation (90). Long-term CoQ10 treatment was shown to partially rescue decreased SQOR protein levels in the kidney of Pdss2kd/kd mutant mice despite only a small rise in CoQ10 levels, suggesting a high sensitivity of SQOR levels to CoQ levels (90). The mechanisms underlying the connection between the levels of CoQ and SQOR expression are not understood. It also remains to be elucidated how altered sulfide metabolism participates in the development and progression of kidney disease due to CoQ deficiency and what possible significance the CoQ-SQOR connection could have for CoQ10 supplementation therapy.

FIGURE 4.

CoQ levels modulate sulfide-quinone oxidoreductase (SQOR) activity. SQOR catalyzes the initial oxidation of hydrogen sulfide (H2S) and utilizes CoQ as the electron acceptor. Sulfur is primarily transferred to glutathione (GSH) under physiological conditions, forming glutathione persulfide (GSSH), which is then oxidized by sulfur dioxygenase (SDO), to produce sulfite () and regenerate GSH. SDO is also known as ethylmalonic encephalopathy protein1 (ETHE1), as its mutations are associated with ethylmalonic encephalopathy, an infantile metabolic disorder. GSSH is also a substrate for thiosulfate sulfurtransferase (TST), which converts to thiosulfate (). Alternatively, is converted to sulfate () by sulfite oxidase (SUOX) residing in the intermembrane space. A further effect of H2S accumulation is inhibition of the enzymatic activity of short-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase (SCAD) that catalyzes the first reaction in the β-oxidation of short-chain fatty acids. Elevated blood butyrylcarnitine (C4) is the hallmark biomarker of SCAD deficiency. In addition to acting as a cofactor of SQOR, CoQ levels regulate SQOR transcriptionally by an unknown mechanism. See glossary for other abbreviations.

2.3. CoQ Concentration and Respiratory Capacity

Most CoQ (>84%) is believed to be free in the bilayer (74). A direct measurement of the amount of CoQ associated with mitochondrial membrane proteins in five different mammalian species (namely mouse, rat, rabbit, pig, and cow) has shown values between 10% and 32% of total CoQ to be protein bound (51, 93). Kinetics studies of CoQ reduction, performed in vitro on mitochondria or submitochondrial particles (inverted vesicles of the IMM), suggest that mitochondrial CoQ concentration is limiting for NADH oxidation by CI. That is, endogenous CoQ concentration in the mitochondria appears to be lower than that allowing maximal NADH oxidation rates (94–97). On the other hand, the normal concentration of CoQ in the IMM appears to be saturating for succinate oxidation by CII (94, 96, 97). Furthermore, in agreement with the kinetic data, it was shown that the incorporation of excess CoQ10 into native beef heart SMPs (by cosonication) induces an increase in NADH oxidation rate, but no rate increase was found for succinate oxidation (97). These are important observations because if the normal endogenous CoQ concentration is limiting, then increasing it could improve respiration, possibly even in the presence of defects in mitochondrial function. However, it should be added that most of the kinetic studies required lyophilization and the use of organic solvents (e.g., pentane) to extract and reconstitute CoQ back into membranes. These are harsh treatments that may seriously perturb the native membrane environment. For example, they could cause SC disassembly. Furthermore, the kinetic studies were mostly conducted with beef heart mitochondria. Thus, how much these in vitro observations are relevant to the in vivo situation and mitochondria of different organisms and tissues needs to be further established.

Under in vitro culture conditions, adding CoQ10 to cells with normal CoQ levels has only sometimes been found to have positive effects on mitochondrial respiration. For example, one study reported that supplementation with a water-soluble CoQ10 formulation resulted in an elevation of uncoupled cellular respiration in T67 human glioma and H9C2 rat myoblast cell lines, measured with a respirometry chamber (41). Other studies showed that treatment with CoQ10 had no effect on mitochondrial respiration in human skin fibroblasts and in a rat pancreatic beta cell line (INS-1), measured with a Seahorse XF Analyzer (98, 99).

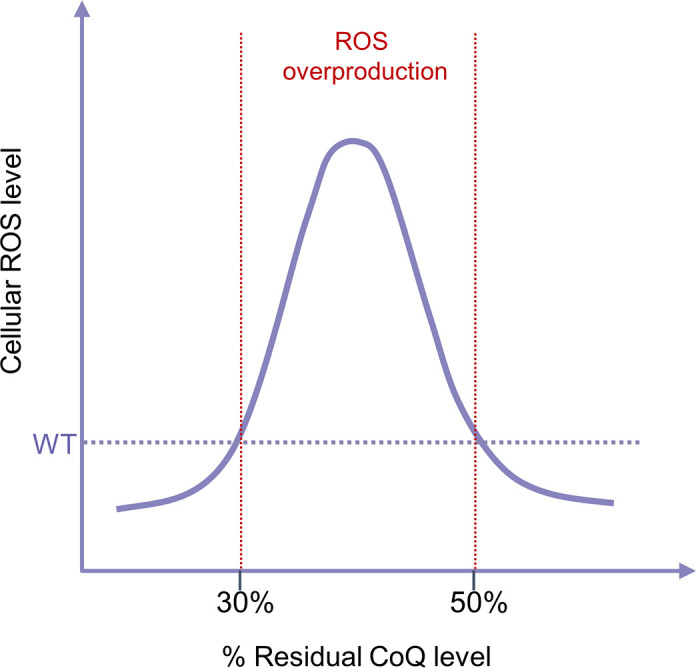

Extensive studies have been conducted on the effect of CoQ deficiency on mitochondrial respiration. Overall, as expected, CoQ deficiency impairs respiratory function, but this is only observed under conditions of severe CoQ deficiency. In E. coli, CoQ8 functions in the aerobic respiratory chain in the cytoplasmic membrane, where it serves to transfer electrons from various substrate-specific dehydrogenases to two terminal oxidases, cytochrome bo3 and cytochrome bd (100). E. coli mutants without CoQ8 biosynthesis (ΔubiA, ΔubiB, ΔubiE, ΔubiF, ΔubiH, ΔubiG) or with a very low level of CoQ8 (<15%) (ΔubiX) grow poorly on nonfermentable succinate, which is indicative of a respiratory defect (101–105). In contrast, ΔubiI and ΔubiK mutants that produce 15–20% of the normal level of CoQ8 showed no growth defect on nonfermentable carbon sources, whereas the ΔubiIΔubiK double mutant, which produces no CoQ8, cannot grow at all on succinate (106–109). As discussed in sect. 5.1.1., yeast mutants lacking CoQ6 biosynthesis are also respiration defective. Interestingly, some findings suggest that CoQ is actually required to stabilize CIII, but how much the effect on CIII stability contributes to the mutant phenotype is not clear (110).

In mammalian cells, a decrease of CoQ levels below ≈60–70% of normal levels was shown to cause an inhibition of CoQ-dependent ETC activities (CI-III and CII-III) as well as a reduction in respiratory capacity and ATP levels. These observations were mostly made in dermal fibroblasts obtained from patients or in mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) from mutants with defective CoQ biosynthesis (80, 83, 111–118). For other cell types, a pronounced depression of respiration was shown for mature murine brown adipocytes and T67 human glioma cells whose CoQ content was depleted to a similar degree (≈50–60% reduction of CoQ) by treatment with a COQ biosynthesis inhibitor (119, 120). It is worth noting that it is likely that the requirement for CoQ, especially for functions other than mitochondrial respiration, varies considerably among different cell types and under different physiological and pathological conditions. Therefore, the conclusions of any study about CoQ must be viewed in the context of cell types and experimental conditions.

Studies at the tissue level are confined to the measurements of CoQ-dependent ETC functions in whole tissues or mitochondria from genetic CoQ deficiency models in mice. The effects of reduced CoQ production on ETC function have been reported for the heart, skeletal muscle, brain, kidney, and liver, which revealed significant variation in the sensitivity to CoQ deficiency across different tissues (30, 82, 90, 121–124). In the liver, an almost complete depletion of CoQ obtained by genetic means in hepatocytes causes only mild or moderate impairment of ETC function (30, 82). However, in the kidney, brain, and heart, which are known to be more energy demanding, a greater loss of respiratory function was found to always accompany severe CoQ deficiency (121, 123). Nonetheless, full respiratory function was observed in mouse kidney mitochondria with less than half of the normal level of CoQ, which is in contrast to what was observed in the heart, where ≈35% of wild-type CoQ levels were found to only sustain about one-half of full oxidative phosphorylation capacity (state 3 respiration) (121, 123). It still remains poorly understood how CoQ deficiency affects individual tissues and cell types. The variation in the relation of CoQ level to mitochondrial respiration may reflect, at least in part, tissue differences in other CoQ functions besides its role in the ETC. The heart is one of the most energy-consuming organs in the body and rich in mitochondria. Thus, likely there is an unusually high proportion of cellular CoQ associated with the ETC in cardiomyocytes. One therefore expects a high correlation between CoQ levels and mitochondrial respiration in cardiomyocytes. In contrast, as further discussed in sect. 3.3.1.2, studies of Pdss2kd/kd mutant mice showed that oxidative stress, apparently caused by impaired H2S oxidation, is most prominent in the kidney, and kidney failure is the primary phenotypic consequence of CoQ deficiency in this strain. A small increase in tissue CoQ10 level after long-term supplementation is sufficient to alleviate oxidative stress and kidney pathology of the mutant (90, 124). We postulate that, although the kidney is also relatively enriched in mitochondria, respiration is not the main consumer of CoQ. As CoQ is made in mitochondria, in the kidney the requirement of CoQ for ETC function might be relatively easily met but not the requirements for CoQ functions that require CoQ export from the mitochondria and distribution to other membranes, which might suffer more. And this might be the case for the place where the antioxidant function of CoQ is so crucially needed. For the liver, whose respiratory function appears to require very little CoQ, the explanation could be in the fact that it is in hepatocytes that dietary CoQ accumulates and is incorporated into lipoproteins (see sect. 3.2.5).

3. DUAL PROOXIDANT AND ANTIOXIDANT ROLES OF CoQ

A free radical is an atom or molecule that contains one or more unpaired electrons. Because of the possession of odd electrons, free radicals are usually unstable, short lived, and highly reactive (125). They can be stabilized by losing or gaining electrons through interactions with other atoms or molecules (to which they provide or from which they steal an electron). This, in turn, can alter the chemical properties of the entities with which they interact. In biological systems, free radicals are mostly oxygen- or nitrogen-containing species, namely reactive oxygen species (ROS) and reactive nitrogen species (RNS), respectively. Their production is part of normal metabolism and an inevitable consequence of aerobic life (126). Under normal physiological conditions, the intracellular levels of ROS and RNS are maintained at low concentrations. Conversely, when produced in excess, their highly reactive nature makes them potentially harmful through their ability to damage macromolecules, such as lipids, proteins, and DNA, which can lead to irreparable cell damage and death (127, 128). ROS and RNS have also been recognized as signaling molecules involved in regulating various physiological processes (129, 130). Therefore, for cell health and survival, a delicate balance must be maintained between ROS and RNS production and elimination (131, 132). In general, an antioxidant is defined as any substance that is capable of neutralizing reactive free radicals into a relatively stable unreactive form. Cells are equipped with antioxidant defense systems, consisting of both ROS-scavenging enzymes (such as superoxide dismutase and catalase) and various nonenzymatic compounds, to neutralize ROS or RNS directly or through enzymatic reactions (133).

The principal ROS produced spontaneously or enzymatically in biological systems is the superoxide anion radical (O2•−), which results from the one-electron transfer to an oxygen molecule. The discovery of superoxide dismutase (SOD), a unique enzyme that converts O2•− into hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), helped launch the free radical theory of aging, which is centered on the accumulation of ROS-caused damage with time (134). ROS are generated by various sources, among which the mitochondrial ETC is one of the principal endogenous ROS generators. There are 12 sites in the mitochondria, with links to the ETC, that have been identified in mammalian cells to be capable of leaking electrons to oxygen and generating O2•− (135). CoQ is one of the major ROS-generating sources in the ETC. During CoQ-mediated electron transport a partially reduced state of CoQ, ubisemiquinone (CoQ•−) is produced as an intermediate that can donate one electron to molecular oxygen, resulting in the formation of O2•− at the CoQ binding sites of ETC complexes. Yet it remains to be established to what extent the amount of CoQ and its redox state contribute to total mitochondrial ROS in a given cell or cell type in a particular physiological state. On the other hand, CoQH2, the fully reduced form, can neutralize free radicals or regenerate other antioxidants, by giving up its own electrons, especially in the lipid membranes where it resides. In fact, CoQ is widely hailed as an antioxidant, and this property along with its key role in mitochondrial bioenergetics is the rationale given for providing CoQ10 as a health supplement. In this section, we summarize findings and analyses in support of the dual pro- and antioxidant role of CoQ.

3.1. Roles of CoQ in Mitochondrial ROS Generation

Superoxide (O2•−) is produced by one-electron reduction of molecular oxygen. SOD converts O2•− to H2O2, which is believed to play a central role in redox signaling. However, the reactivity of H2O2 itself can in turn lead to the formation of other reactive species, such as the very damaging hydroxyl radical (•OH) (136). O2•− also reacts with nitric oxide (NO•) to produce peroxynitrite (ONOO•), a toxic RNS. In fact, the reaction rate constant of O2•− with NO• (6.7 × 109 M−1 s−1) is several times faster than the rate constant of the action of SOD on O2•− (1.6 × 109 M−1 s−1) (137). Thus, changes in NO• levels can potentially affect O2•− levels and hence the cellular redox state. Conversely, excessive O2•− can have an impact on the level of NO• as a signaling molecule and on nitrosative stress as a result of increased production of ONOO• (138, 139).

In most cells, the ETC is the major O2•− production site, except in phagocytes, where ROS are deliberately produced by NADPH oxidases (NOX) to produce an oxidative burst designed to kill pathogens in the phagosome (140–142). It is commonly repeated that mitochondria generate ∼90% of cellular ROS and during mitochondrial respiration ∼0.2–2% of the molecular oxygen consumed is reduced to O2•− (143–146). However, the actual numbers are still debated. One commonly used method to measure total ROS produced by isolated intact mitochondria is to use Amplex Red dye, which, in the presence of H2O2, can be oxidized by horseradish peroxidase to give rise to a fluorescent oxidation product, resorufin (147). Although O2•− does not readily cross membranes, SOD is provided at a high concentration in the assay’s medium to ensure that all O2•− produced is actually converted to H2O2. It is because of this method that in the text below we sometimes refer to O2•−/H2O2 generation, although the species that is expected to be formed at a site of interest is O2•−.

Studies with isolated ETC complexes and mitochondria have identified a number of sites of ROS production including the CoQ binding sites of CI and CIII. CII is not normally a substantial source of ROS production by mitochondria. In conditions under which ROS production is induced from mammalian CII, it is the flavin site, not the CoQ binding site IIQ, that is the most likely source of electron leak (148–150). Interestingly, it is also worth noting that among the other IMM dehydrogenases, mitochondrial G3PDH (mGPDH) was shown to be capable of producing significant amounts of ROS, with CoQ suggested to be the source of ROS in this process (150, 151).

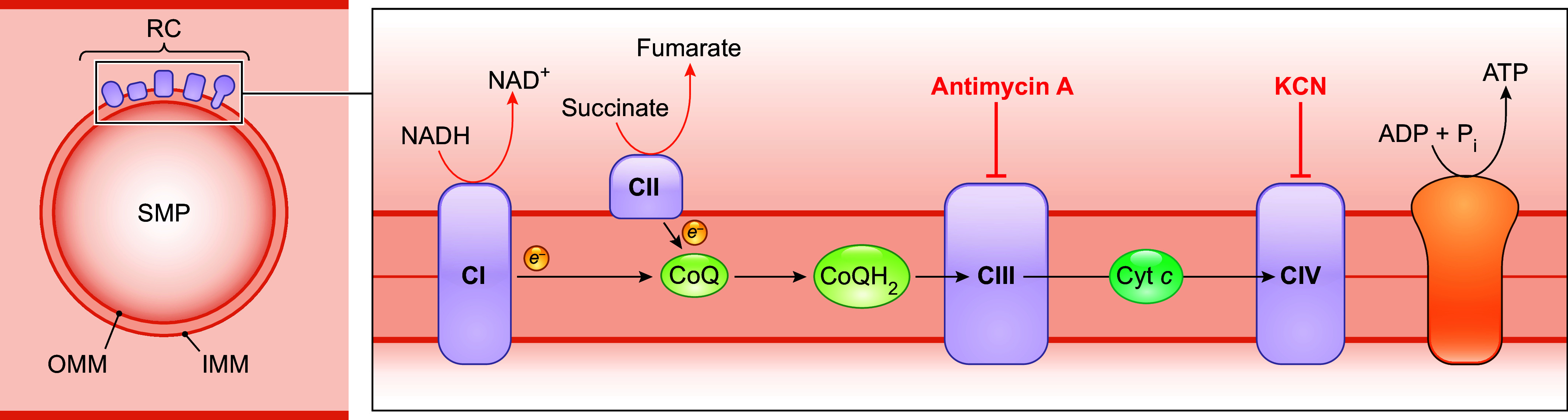

Reduction and oxidation of CoQ in mitochondria occur in two sequential one-electron steps (152). Inevitably, the process involves the creation of a partially reduced form of CoQ (CoQ•−) as an intermediate (FIGURE 1) (153, 154). As mentioned, CoQ•− is a source of mitochondrial O2•− because of its propensity to donate its unpaired electron to O2. Indeed, CoQ•− signals were detected at the CoQ binding sites of the ETC complexes CI, CII, and CIII by electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) (152, 154–157). The capability of CoQ to participate in O2•− formation was first demonstrated in beef heart SMPs from which CoQ10 was extracted and then replenished (153). SMPs are inverted (inside out) vesicles of the IMM (FIGURE 5). As they maintain the structural integrity of the IMM and have the substrate binding sites exposed to the outer surface, they have been a valuable tool for mitochondrial functional studies. Later studies also used electron transport inhibitors specific to particular ETC complexes or sites (such as antimycin A and potassium cyanide) and, more recently, electron leak suppressors for specific CoQ sites (147, 158–160). These studies further established the contribution of different CoQ binding sites to ROS production by mitochondria during the oxidation of different substrates. Yet, not surprisingly given the chemo-physical complexity of the reactions involved, many uncertainties remain.

FIGURE 5.

Diagram of a submitochondrial particle (SMP). A SMP is an inside-out vesicle of the inner mitochondrial membrane (IMM). It retains all the respiratory chain (RC) components, and the inversion of the IMM exposes CI and CII to the medium, allowing unrestricted access to oxidation substrates, including NADH, which could not pass through the IMM. See glossary for other abbreviations.

3.1.1. Role of CoQ in ROS production from complex I.

3.1.1.1. ros production by complex i during forward electron flow.

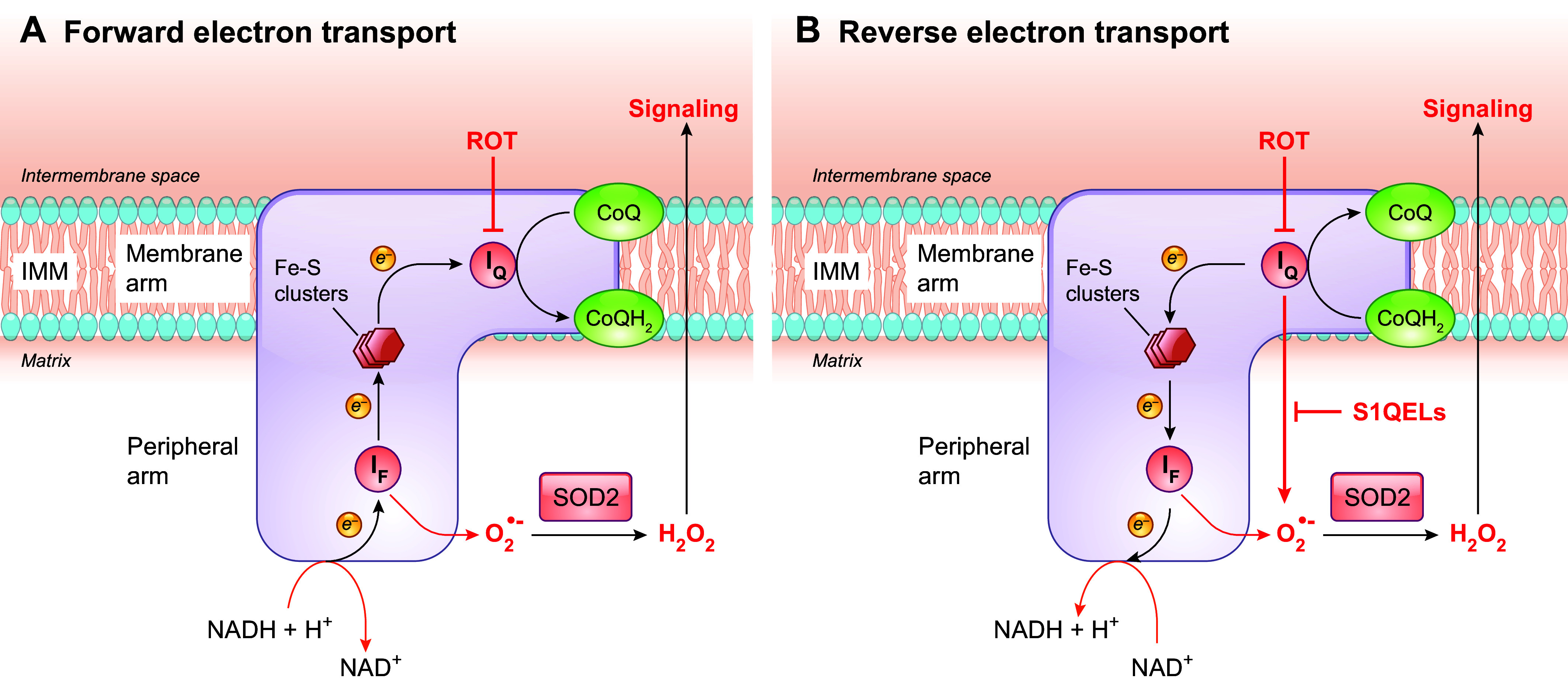

At CI, electrons move from NADH to the flavin mononucleotide (FMN, the IF site) to iron-sulfur clusters, and finally to CoQ (FIGURE 6). CI from the yeast Yarrowia lipolytica and E. coli were shown to contain 0.2–1 CoQ molecules per complex (161). The CoQ reduction site (the IQ site) is located at the junction of the hydrophobic membrane arm and the hydrophilic matrix arm (162). CI-linked substrates (i.e., glutamate or pyruvate in combination with malate) that feed electrons from NADH to the respiratory chain in the forward direction (starting from the IF site) are generally considered to give low rates of O2•− production, and ROS production under these conditions largely originates from the IF site (FIGURE 6). In other words, the IQ site normally does not dominate ROS production from CI, although this is debated (147, 163–165).

FIGURE 6.

ROS production sites in CI. A: with forward electron transport, NADH is oxidized at the flavin mononucleotide (FMN, the IF site). Electrons are then passed via several iron-sulfur (Fe-S) clusters to the CoQ binding site (IQ), where CoQ is reduced before it dissociates from CI. B: reverse electron transport occurs when electrons from an overreduced CoQ pool flow back to CI and reduce NAD+. The IF site has been considered to be the main site of ROS production from CI under the oxidation of NADH-linked substrates. ROS production during reverse electron transport mainly originates from electron leakage from reduced CoQ formed at the IQ site, but the IF site has also been shown to contribute. Rotenone (ROT) blocks the flow of electrons by inhibiting the binding of CoQ to IQ, whereas S1QELs suppress electron leak from CoQ•− to oxygen at the IQ site specifically. They do this without interfering with normal electron flow, and therefore this is expected to affect ROS generation during reverse electron transport. The O2•− produced by CI is released into the matrix, where superoxide dismutase 2 (SOD2) converts it to H2O2. See glossary for other abbreviations.

3.1.1.2. ros production by complex i during reverse electron flow.

CI can also produce ROS when electrons flow through CI in the reverse direction. That is, electrons flow back from CoQH2 to CI and reduce NAD+ to NADH. Reverse electron transport (RET) has been known since the 1960s. It was first associated with ROS production in well-coupled SMPs, and it was later also shown to take place in isolated mitochondria from different tissues (166, 167). The conventional substrate to drive RET is the CII substrate succinate. In fact, in the setting of isolated mitochondria, succinate-induced RET produces the highest rate of ROS production (167, 168). Although the question of exactly where ROS are produced during RET is still controversial, it has been largely accepted that the CoQ binding site in CI, the IQ site, is one of the prime loci of electron leak during RET (FIGURE 6) (135). Superoxide production by CI during RET is sensitive to the classic IQ site inhibitors, such as rotenone and piericidin A (147, 169, 170). These inhibitors block the binding of CoQ to IQ, thus preventing the possibility of electron escape from CoQ•− to oxygen (171). However, their use also inhibits reverse electron flow into CI, potentially affecting O2•− production from other sites as well. In fact, more recently, both IF and IQ sites were shown to generate ROS in mitochondria isolated from rat skeletal muscle when respiring on succinate (also see sect. 3.1.1.3) (172). Notably, in recent studies by Martin Brand’s group, a novel approach was developed that allows estimation of the rate of rotenone-sensitive O2•− production from the site IQ while considering any change of ROS production by the two other key sites (the IF site of CI and the Qo site of CIII). With this approach it was estimated that in rat skeletal muscle mitochondria under succinate oxidation, ≈83% of O2•− originates from the IQ site, whereas that site made little or no contribution when the substrates were glutamate plus malate (163). Furthermore, in a step toward understanding ROS production in muscles in vivo, it was shown ex vivo that under conditions that mimic those in resting muscles a quarter of the total O2•− production of rat skeletal muscle mitochondria could be attributed to the IQ site, whereas the IF site of CI became the dominant contributor (≈99%) under conditions mimicking intense exercise, when total O2•− production is much lower (173).

RET is energetically uphill (i.e., against the difference of redox potentials). For IQ to generate O2•− at high rates, a highly reduced CoQ pool (to provide the electrons) and a high protonmotive force (PMF) that drives protons back into the matrix through CI are necessary (167, 174, 175). These conditions are thought unlikely to occur often under normal physiological conditions. Moreover, mitochondrial succinate levels and succinate dehydrogenase (SDH) activity in normal cells are low (176). Therefore, succinate-driven RET had initially been proposed to be minimal under normal conditions but capable of being triggered by particular stresses and thus leading to damage. One of the most cited examples is ischemia-reperfusion (I/R) injury. Succinate and other metabolic substrates accumulate during ischemia, but upon reperfusion succinate is rapidly oxidized, leading to a burst of ROS production through RET, which may contribute significantly to reperfusion injury (168, 177, 178). It is noteworthy, however, that the role of succinate-driven RET in I/R injury still remains to be fully elucidated, as it has been challenged by some studies (179). RET-dependent ROS is now thought to exist also beyond pathological conditions. It has been associated with various cellular processes, including differentiation of myoblasts into myotubes, initiation of macrophage inflammatory responses, oxygen sensing by the carotid body chemoreceptors, and uncoupling of mitochondria in brown adipose tissue (180–183). Of particular interest, ROS generation from RET has been implicated in metabolic adaptation, with the CoQ redox status acting as a sensor to adjust the respiratory chain organization for optimal efficiency. During a metabolic shift from glucose to fatty acids, which increases electron flux through FAD, it has been shown that accumulation of reduced CoQ (CoQH2) induces RET and results in the local generation of ROS that oxidizes CI proteins. These events, in turn, lead to CI degradation, which liberates CIII from CI + CIII SCs to receive FADH2 electrons from CII in order to adapt to substrate utilization (24).

3.1.1.3. findings with specific suppressors of the iq site electron leak.

Additional insight on CI ROS generation and CoQ has been provided by more recent studies with novel site-selective suppressors of electron leak. As mentioned above, the classic IQ site inhibitors, such as rotenone, block the electron transfer from, or to, CoQ through the IQ site (171). This inevitably perturbs regular electron flow and thus affects ROS production from other sites as well. In the forward direction under oxidation of NADH-linked substrates, rotenone suppresses electron flow to CIII but raises ROS production from the CI sites upstream of IQ as a result of increased FMN and iron-sulfur center reduction. Conversely, during succinate oxidation, by inhibiting electrons flowing back to CI, rotenone reduces ROS production at the IQ site as well as at the IF site (172). In contrast, the newly developed S1QELs (suppressors of site IQ electron leak) can specifically suppress electrons leaking from the IQ site without interfering with normal electron flow and respiration, making them a better tool for studying ROS generation from the IQ site (172, 184). With this tool, it was shown that S1QELs can suppress ROS generation from CI without affecting reverse electron flow during RET, providing better evidence for IQ being a source of mitochondrial ROS when CoQ becomes overly reduced by electrons from CII or other enzymes. Moreover, with this tool, it was shown that ≈12% of the total rate of H2O2 release in C2C12 mouse myoblasts comes from the IQ site. After differentiation into myotubes, total ROS release was increased, and the relative contribution of the IQ site doubled (185). A similar study with several other cell lines further showed that although the absolute cellular H2O2 production rates vary considerably, the relative contribution of the IQ site to total H2O2 release is similar (range 11–26%) among the diverse cell types under unstressed conditions (186). In isolated mitochondria from rat muscle incubated in media mimicking the cytosol of resting muscle, ≈12–18% of total ROS emission was sensitive to S1QELs, consistent with the above-mentioned measurements made using endogenous reporters of H2O2 levels (173, 185). S1QELs have also demonstrated a protective effect against stress-induced stem cell hyperplasia in the Drosophila intestine and in mice I/R injury models (184). These findings argue for the physiological significance of ROS production at the IQ site. Whether all IQ site ROS production is via RET is not yet clear (165, 187).

Emerging studies suggest that RET could be favored by other conditions besides a high concentration of succinate. This includes an elevation of the activity of the other metabolic pathways that feed electrons to the CoQ pool (see sect. 2.2) and a slowdown of CoQH2 reoxidation at CIII (24, 75, 160, 163, 188). For example, the IQ site has been shown to contribute substantially (≈33%) to the total O2•− production rate when glycerol 3-phosphate is provided as a respiratory substrate (163).

Finally, it should be mentioned that different subpopulations of CoQ•− have been reported to be associated with CI (189). Rotenone-sensitive and -nonsensitive CoQ•− were first described to be detectable in bovine heart purified CI upon reduction by NADH and in SMPs from bovine heart mitochondria under oxidation of NADH or succinate (157, 190). Later studies with bovine heart SMPs and isolated CI from different species also demonstrated the presence of at least two types of CI-associated CoQ•− species with distinct spin relaxation behaviors: namely, the fast-relaxing ubisemiquinone (SQNf) and the slowly relaxing ubisemiquinone (SQNs) (154, 156, 191–196). The SQNf signal is sensitive to uncouplers and rotenone and was more obvious in the presence of the ATP synthase inhibitor oligomycin (156, 194, 196). The presence of two different EPR-detectable CI-associated CoQ•− species has been taken to indicate the presence of two spatially separated CoQ binding sites in CI. However, this is still debated (154, 156, 161, 192, 195, 197).

3.1.2. The role of CoQ in ROS production from complex III.

3.1.2.1. the q cycle.

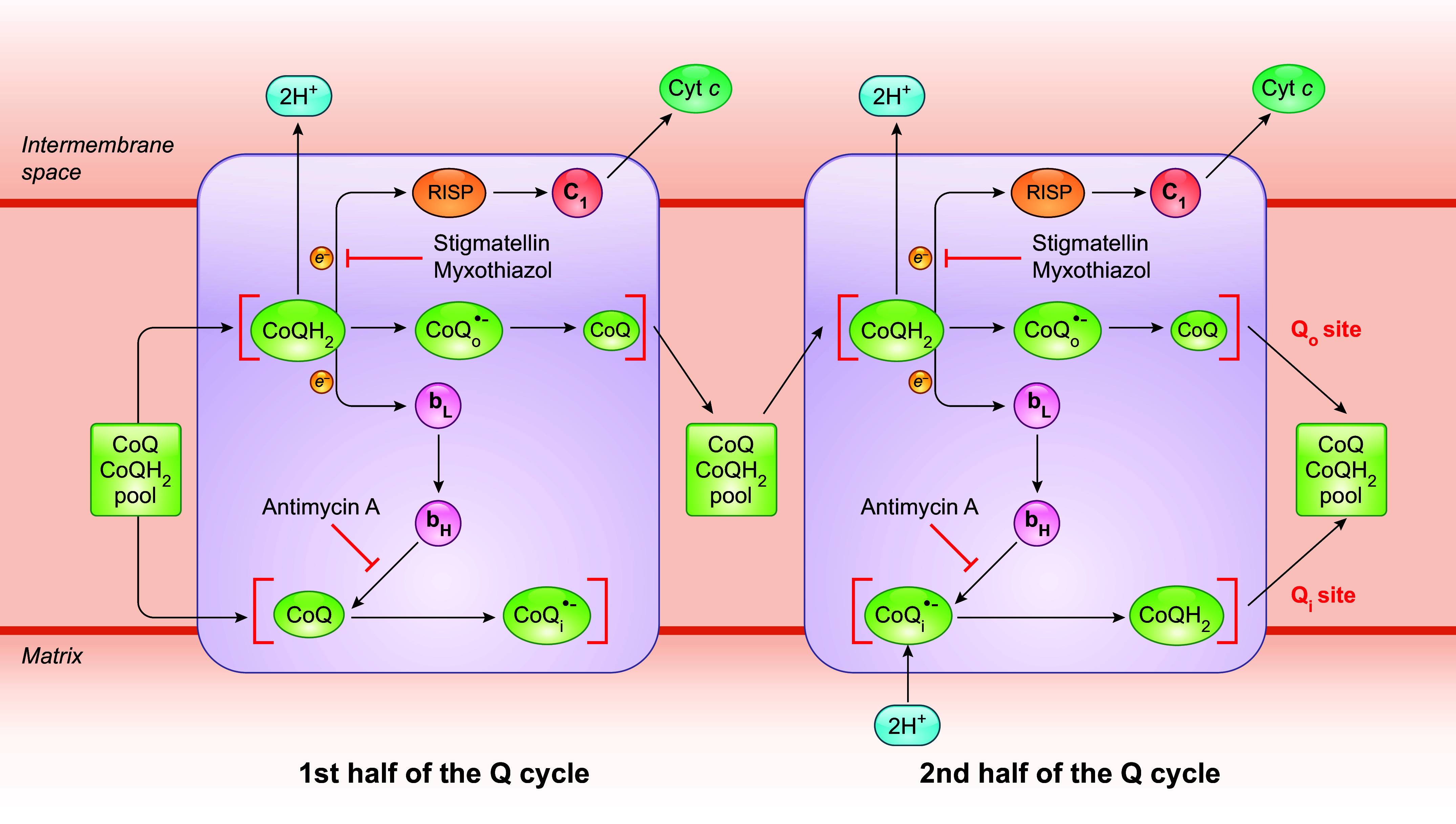

CIII, which is also often called the cytochrome bc1 complex (cyt bc1), harbors two separate CoQ binding sites: Qo (also called Qp) and Qi (also called Qn), which face the compartments on opposite sides of the IMM. Qo is located close to the outer surface of the IMM in mitochondria and on the periplasmic side in bacteria, whereas Qi is facing the matrix (mitochondria) or cytoplasm (bacteria) (198). The Qo and Qi sites are connected electronically by two cyt b hemes, bL and bH (3). As mentioned above, CIII catalyzes a reaction of net oxidation of CoQH2 and reduction of cyt c. Oxidation of CoQH2 occurs at the Qo site and is accompanied by a CoQ reduction reaction at the other site (Qi) (199, 200). The electron transfer reactions are coupled with proton movement. That is, protons are taken up by CoQ at the Qi site, carried across the membrane by CoQH2, and released at the Qo site (200). The mechanism by which electrons are transferred from CoQH2 to cyt c and by which, at the same time, protons get translocated into the intermembrane space is known as the Q cycle (FIGURE 7). This mechanism was originally proposed by Peter Mitchell almost a half-century ago but has since been modified by several groups (46, 201–203). In essence, in the version generally adopted nowadays, the Qo site oxidizes two CoQH2 molecules in two successive steps, which provides two electrons needed to fully reduce one CoQ molecule at the Qi site. In the first step, following the binding of one CoQH2 molecule to the Qo site, the transfer of two electrons from that molecule is bifurcated. That is, one electron moves through the “Rieske” iron-sulfur protein (RISP), a component of CIII, and the cyt c1 heme before it is accepted by cyt c. The other electron enters the Q cycle, where it is routed through the cyt bL and cyt bH hemes and moves across the membrane to reach the Qi site, where it acts as an electron donor to reduce CoQ to CoQ•−. The second step is the repeat of the first, where a new CoQH2 binds to the Qo site and again one electron is sent through the cyt b chain but now it encounters a CoQ•− at site Qi. Therefore, at the end of a complete Q cycle, as a net result two CoQH2 molecules are oxidized at the Qo site and four electrons move through the Q cycle, resulting in the passaging of two electrons to cyt c and sequential reduction of one CoQ molecule to CoQH2 at the Qi site before it is released to the CoQ pool (198). Concurrently, there is a net release of four protons (H+) into the intermembrane space from the two CoQH2 molecules oxidized at the Qo site and uptake of two H+ from the mitochondrial matrix into the Qi site.

FIGURE 7.

Schematics of the mechanism of the Q cycle. The Q cycle mechanism defines 2 reaction sites in CIII: CoQH2 oxidation (Qo) and CoQ reduction (Qi). The Qo site is located between the Rieske iron-sulfur protein (RISP) and heme bL, toward the intermembrane space, whereas the Qi site is close to the matrix side. It takes 2 CoQH2 oxidation cycles to complete the Q cycle. At first, a CoQH2 moves into the Qo site and undergoes oxidation, with 1 electron being transferred to RISP and then to cyt c via cyt c1. The other electron passes through 2 b-type hemes (bL and bH) across the membrane to the Qi site, where a bound CoQ is reduced to CoQ•− and finally to CoQH2. CoQ and CoQH2 are recycled back to the CoQ pool from the Qo and Qi sites, respectively, after being fully oxidized or reduced. Oxidation of each CoQH2 molecule releases 2 protons into the intermembrane space, and in the second half of the cycle 2 protons from the matrix are used to reduce CoQ•−. Given that it takes 2 electrons to fully reduce a CoQ molecule, a CoQ•− intermediate is expected to be formed at the 2 distinct CoQ binding sites. Stigmatellin and myxothiazol are Qo site inhibitors, whereas antimycin A blocks electron transfer from bH to the CoQ molecule at the Qi site. See glossary for other abbreviations.

3.1.2.2. mechanism of coqh2 reoxidation at the qo site.

A key feature of the mechanism of the Q cycle is that there are two distinct CoQ reaction sites: a CoQH2 oxidation center (the Qo site) and a CoQ reduction center (the Qi site). There has been much research aimed at understanding electron bifurcation at the Qo site, which is believed to be the only known reaction of its kind in biology. One model of Qo site catalysis postulates two sequential electron transfer steps: the first electron transfer from CoQH2 to the [2Fe-2S] cluster (ISC) of RISP, leading to the generation of a CoQ•− radical intermediate, CoQo•−, followed by the oxidation of this intermediate by heme bL in the second reaction (3, 152, 204). So far, native CoQ or CoQH2 molecules have not been resolved at the Qo position in X-ray crystallography studies (205, 206). Characterization of the bindings of different Qo inhibitors, through observations of their effects on the absorption spectrum of heme bL or the EPR spectrum and redox properties of the ISC, and later crystallographic studies of cyt bc1 complexes, suggests that separate functional domains might be present within the Qo site. For example, although myxothiazol, stigmatellin, and 5-undecyl-6-hydroxy-4,7-dioxobenzothiazol (UHDBT) all bind to the Qo site and prevent CoQH2 oxidation, myxothiazol binds to the proximal region near cyt bL, whereas the binding site of UHDBT is at a greater distance from cyt bL and interacts specifically with the ISC of RISP and stigmatellin overlaps both the distal and proximal positions (204, 207–209). Based on studies with the inhibitors, two subsites within the Qo site have been proposed: the proximal part of the site, close to the bL heme (≈7 Å from the heme bL and ≈12 Å from the ISC), and the distal part of the site, closer to RISP (≈7 Å from the ISC and ≈12 Å from heme bL) (208, 209).

Although the binding of a CoQH2 molecule to the different regions of the Qo site still remains to be formally confirmed, the possibility of two separate CoQ binding regions in the Qo pocket leads to a hypothesis that a CoQo•− intermediate generated after the first electron transfer from CoQH2 to RISP might diffuse from one subsite to another before the second electron transfer from the CoQo•− to heme bL occurs. To be more specific, it is postulated that CoQH2 is first bound in the distal part of the Qo pocket where CoQH2 transfers one electron to RISP, generating a CoQo•− intermediate. After having formed, the partially oxidized intermediate moves into the pocket at the proximal end of the site, near heme bL. The movement, together with a conformation change of the site, provides the mechanistic barrier for preventing any CoQo•− formed from further interaction with the oxidized ISC of RISP (208). Separately, an alternative double-occupancy model proposes that the Qo site can accommodate two CoQH2 molecules at the proximal and distal regions simultaneously (209–211). However, this hypothesis has been challenged by crystal structure studies suggesting there might not be enough room in the Qo site to accommodate two CoQH2 at the same time (205).

Experimental detection of CoQ•− bound at the Qo site has proven difficult. It has been variously interpreted as indicating a high instability of CoQo•−, or extreme difficulty in its detection, possibly due to magnetic coupling between CoQo•− and the reduced ISC of RISP, or the possibility that, if both electron transfers to RISP and heme bL occur simultaneously, no CoQo•− intermediate would actually be formed (3, 152, 204, 212). However, several recent studies have reported successful CoQo•− detection when its reoxidation is blocked, by the use of either a Qi site-specific inhibitor or a heme bH knockout by genetic means (155, 213, 214). These findings, though not accepted by everyone, argue against a Qo site model of simultaneous two one-electron transfers from CoQH2.

3.1.2.3. coq reduction at the qi site.

The Qi site is at the end of the cyt bL-cyt bH electron transfer chain and is situated near the matrix side of mitochondria and the cytoplasmic side of the bacterial membrane, where protons are taken up during catalysis for reduction of CoQ (215). In contrast to the situation with the Qo site, X-ray and cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) structural studies of the cyt bc1 complexes have documented a CoQ occupancy within the Qi site (198, 206, 216–218). Mechanistically, heme bH reduces CoQ to CoQi•− after an electron is transferred from the first CoQH2 that moves to the Qo site and reduces CoQi•− to CoQH2 after a second oxidation event. As the CoQi•− intermediate that is formed after every first CoQH2 oxidation at Qo needs to remain at the Qi site until the second CoQH2 oxidation takes place, CoQi•− is predicted to be more tightly bound than CoQo•−. This has been regarded as a plausible explanation of why CoQi•− intermediate is easier to detect than CoQo•−. Antimycin A, the best-known Qi site inhibitor, blocks the electron transfer from cyt bH to the Qi site and thus inhibits the reduction of the CoQ pool.

3.1.2.4. ubisemiquinone is the source of mitochondrial ros generated by complex iii.

We have discussed that an unstable CoQ•− can directly reduce O2, forming O2•−, and that the CoQ•− formed at the Qo site is less stable than that at the Qi site (219, 220). Moreover, only the CoQ•− at the Qo site is thought to have a sufficiently low redox potential to be able to give an electron to oxygen (221). Thus, the Qo site, not the Qi site, is the most likely electron donor in the production of O2•− at CIII. This has been demonstrated experimentally in various types of preparations (intact mitochondria, SMPs, and isolated cyt bc1 complexes) by the use of inhibitors that bind specifically to only one of the two distinct CoQ-binding sites (3, 147). Generally, Qi site inhibitors (the most classic one being antimycin A) are found to induce high rates of ROS production, whereas Qo site inhibitors (e.g., stigmatellin and myxothiazol) suppress antimycin A-induced ROS production (209, 222, 223). These findings can be best explained by the Q cycle mechanism of CIII. In the presence of antimycin A, hemes bH and bL cannot be reoxidized by electron transfer to the Qi site. Thus, CoQ•− formed upon the first oxidation of the first CoQH2 at the Qo site is unable to donate electrons to hemes bL, resulting in longer residence of CoQo•− at the Qo site and greater probability of electron transfer to oxygen resulting in O2•− formation (224). Qo site inhibitors stigmatellin and myxothiazol on the other hand prevent the formation of CoQ•− at the Qo site and thus eliminate the stimulation of O2•− production by antimycin A. But, notably, in contrast to stigmatellin, which completely blocks O2•− production by CIII, myxothiazol only partially (by ≈70%) prevented antimycin A-induced O2•− production (225, 226). Furthermore, the effect of myxothiazol on its own also leads for O2•− formation. The rate of myxothiazol-induced O2•− production is lower than that observed with antimycin A and is highly sensitive to stigmatellin as well (209, 225, 227). Stigmatellin, as mentioned above, binds to the Qo site in the distal part of the site, near RISP. A crystal structure with bound stigmatellin shows it binding in the same position as CoQH2, to a histidine ligand of the ISC of RISP via a hydrogen bond. This would be expected to exclude CoQH2 and prevent CoQo•− formation [Crofts (198)]. Myxothiazol, however, is binding to the proximal part of the Qo site, near cyt bL (209, 216). This suggests that myxothiazol does not entirely exclude CoQH2 from binding at Qo. Overall, these findings suggest a model in which the distal part of the Qo site pocket is the main source of CoQ•− formation at Qo but both the distal and proximal parts of the CoQ binding sites transiently contain CoQ•−, with the potential to reduce oxygen and contribute to CIII ROS production.

With regard to the relative contribution of the Qo site to mitochondrial ROS, it was shown that, in rat skeletal muscle mitochondria, the Qo site made only a modest contribution (≈10%) to the total O2•− production under succinate oxidation but accounted for ≥30% of the total production rate when CI substrates (glutamate or malate) or substrates of β-oxidation (palmitoylcarnitine plus carnitine) were being oxidized. This estimate was made possible by using the state of cyt bL reduction as an endogenous reporter for the rate of O2•− formation at the Qo site (163, 228). Under ex vivo conditions that mimic rest or mild aerobic exercise, ≈15% of total O2•− was produced from the Qo site, whereas very little or no ROS was produced from the Qo site under conditions that mimic intense aerobic exercise in skeletal muscles (173). These findings are in good agreement with the reported value obtained with several S3QELs (Suppressors of site IIIQo electron leak), which selectively suppress O2•− formation from the Qo site but do not block electron flow or affect OXPHOS (185, 229). S3QELs were also used to assess the contribution of Qo-derived O2•− to cell physiology and pathology. In various cell types, treatment with S3QELs was shown to suppress the total rate of extracellular H2O2 release by a similar extent within a 13–30% range, despite the fact that the absolute cellular H2O2 production rates vary greatly among the diverse cell types (141, 185, 186). In vivo studies with Drosophila reported that feeding S3QELs protects against ROS-induced stem cell hyperplasia in the intestine, and S3QELs also decrease diet-induced intestinal barrier disruption in both flies and mice, suggesting a key role for Qo ROS in these pathologies (184, 230).

Finally, it is important to note that, in contrast to most mitochondrial ROS forming sites, which release O2•− into the matrix, the Qo site emits at least some O2•− directly into the IMS (145, 160, 186, 231, 232). As mentioned above, O2•− cannot easily diffuse through the IMM, so after being released into the matrix it is mostly confined to the matrix, where it can directly oxidize the Fe-S clusters of enzymes such as aconitase or be converted to H2O2 by SOD2 (233). H2O2 can then diffuse out of the mitochondria and function as a signaling agent. A minor fraction of cytosolic SOD1 is found in the IMS, where it can catalyze the dismutation of O2•− into H2O2 (234–236). Unlike the IMM, the OMM is porous, allowing the easy passage of small molecules including H2O2. Moreover, some of the O2•− in the IMS may also escape into the cytosol via voltage-dependent anion channels in the OMM (237). Consequently, O2•− and H2O2 produced in the IMS should have easier access to the cytosol, where they can act as signaling molecules. For example, several studies showed that ROS from the Qo site is required for the stabilization of the HIF-1α protein during hypoxia, although conflicting findings have also been published (238, 239).

3.2. The Antioxidant Function of CoQ

It is well known that by virtue of its chemical properties, CoQ can act as an antioxidant. In its reduced state, it can give up its electrons to free radicals, thus stabilizing them and neutralizing their reactivity (240, 241). CoQ is also known for its ability to help regenerate other antioxidants such as vitamin E back to their active states. CoQ appears present in all cellular membranes, where its reduced form (CoQH2) can be restored from the oxidized form (CoQ) by various enzymatic mechanisms, and its primary antioxidant role is believed to act on lipid radicals generated when lipids are peroxidized (12). In fact, significant amounts of CoQH2 can be measured in various membrane fractions (including the plasma membrane and endomembranes) (242, 243). The antioxidant activity/capacity of CoQ is doubtlessly dependent on both the total amount of CoQ and the ratio between reduced and oxidized forms (CoQH2/CoQ). In the IMM, where CoQ passes through oxidation and reduction reactions during electron transport, the balance of reduced and oxidized CoQ is maintained by the activity of the respiratory chain. Yet what affects total CoQ content and the ratio between CoQH2 and CoQ in the IMM remains largely elusive. Outside the mitochondria, the plasma membrane redox system (PMRS), also called the trans-plasma membrane electron transport (PMET) system, is the best-understood mechanism that involves the redox cycling of CoQ.

3.2.1. Redox cycling of CoQ in the plasma membrane redox system.

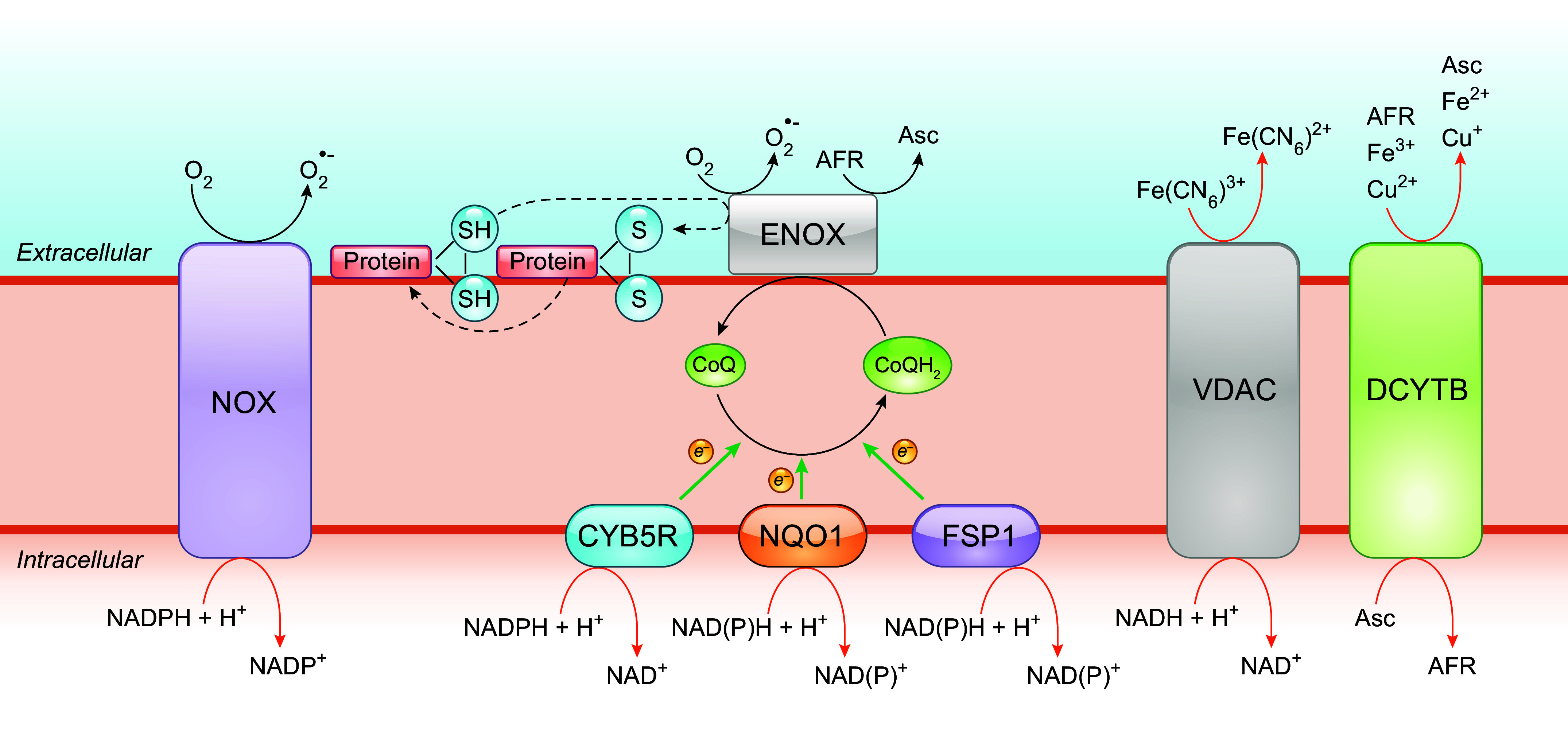

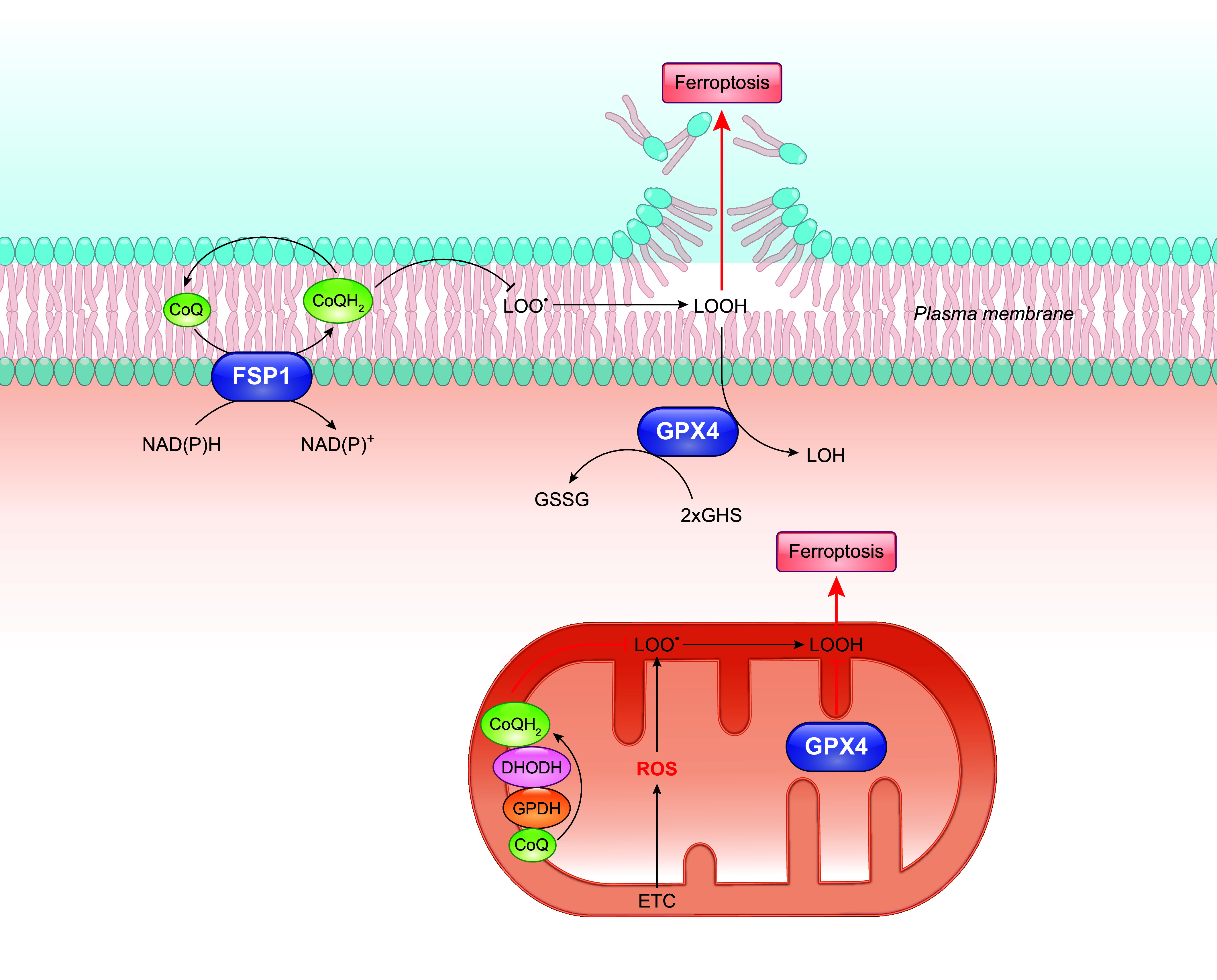

The PMRS operates in all living cells, from bacteria to humans, although its components may vary depending on cell type (244, 245). Mainly, it allows electrons from intracellular substrates to flow outward to extracellular electron acceptors, by a process that is centered on CoQ (7, 246, 247). Physically, the classic description of the PMRS in mammalian cells consists of cytosolic and plasma membrane-associated oxidoreductases that transfer electrons, derived from NADH or NADPH, to the membrane-embedded intermediate electron carrier CoQ and finally to extracellular electron acceptors such as oxygen (248) (FIGURE 8). The enzymes involved in CoQ-dependent PMRS activity include NADH-cytochrome b5 reductase (CYB5R), NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase 1 (NQO1), formerly known as DT-diaphorase, and the recently identified ferroptosis suppressor protein 1 (FSP1) (249–253). CYB5R, present at the inner surface of the plasma membrane (also in mitochondria and the endoplasmic reticulum), catalyzes the one-electron reduction of CoQ by NADH, resulting in the formation of ubisemiquinone (CoQ•−), which can be further reduced to CoQH2, whereas NQO1 reduces CoQ with either NADH or NADPH by a two-electron reaction, directly to CoQH2 (245, 254). NQO1 is known to be primarily cytosolic but can be translocated to the inner surface of the plasma membrane under stress conditions (255). FSP1 (also known as AIFM2), like NQO1, utilizes both NADH and NADPH as electron donors to reduce CoQ. The NH2 terminus of FSP1 contains a canonical myristoylation site that is essential for its plasma membrane localization (252, 253, 256). The reduced CoQH2 can then shuttle electrons to the cell surface NADPH/NADH oxidase (NOX) (external NOX, ENOX) that is able to reduce oxygen to yield O2•– or use the oxidized form of ascorbate (Asc), the ascorbyl free radical (AFR), as the terminal electron acceptor (246, 257–259). Other PMRS activities that do not involve CoQ include electron transfer by the transmembrane NOX proteins, the duodenal cytochrome b (DCYTB), or the NADH:ferricyanide reductase [known as the voltage-dependent anion-selective channel (VDAC)] (260–265) (FIGURE 8). Of note, it was suggested that CoQ might also function as a physiological substrate of VDAC (261).

FIGURE 8.

Role of CoQ in the plasma membrane redox system (PMRS). The PMRS consists of multiple component operations that result in electron transfer from cytosolic reducing equivalents to extracellular electron acceptors. NADH-cytochrome b5 reductase (CYB5R), NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase 1 (NQO1), and ferroptosis suppressor protein 1 (FSP1) are CoQ reductases that oxidize NADH or NADPH to reduce CoQ. The cell surface protein ENOX is the terminal oxidase by catalyzing electron transport from CoQH2 to extracellular electron acceptors, including oxygen (O2) and ascorbyl (monodehydroascorbate) free radical (AFR). Besides oxidizing CoQH2, ENOX also possesses an alternative activity, which is catalyzing protein disulfide-thiol interchange. Other enzymes of the PMRS include the NADPH/NADH oxidase (NOX) that directly catalyzes the 1-electron transfer from cytosolic NADPH to molecular oxygen, the voltage-dependent anion-selective channel (VDAC) that reduces extracellular ferricyanide using NADH as electron donor, and the duodenal cytochrome b (DCYTB) that utilizes ascorbate (Asc) in the cytosol as an electron donor to reduce either extracellular ferric iron (Fe3+), cupric copper (Cu2+), or AFR. See glossary for other abbreviations.

One of the recognized roles of the PMRS, perhaps the most important one, is the control of the cytosolic NAD+-to-NADH ratio, thus modulating the cellular energy balance and redox homeostasis (see also sect. 4.4) (245). The PMRS is also implicated in iron uptake and immune cell function (246). Furthermore, the PMRS allows for the reduction of CoQ at the expense of intracellular reducing equivalents. This reduced pool of CoQ is believed to play an important role in antioxidant protection, mainly against membrane lipid peroxidation and also via regenerating other antioxidants (see below).

3.2.2. Antioxidant role of CoQ by regenerating vitamin C and E.

3.2.2.1. role of coq in vitamin c regeneration.

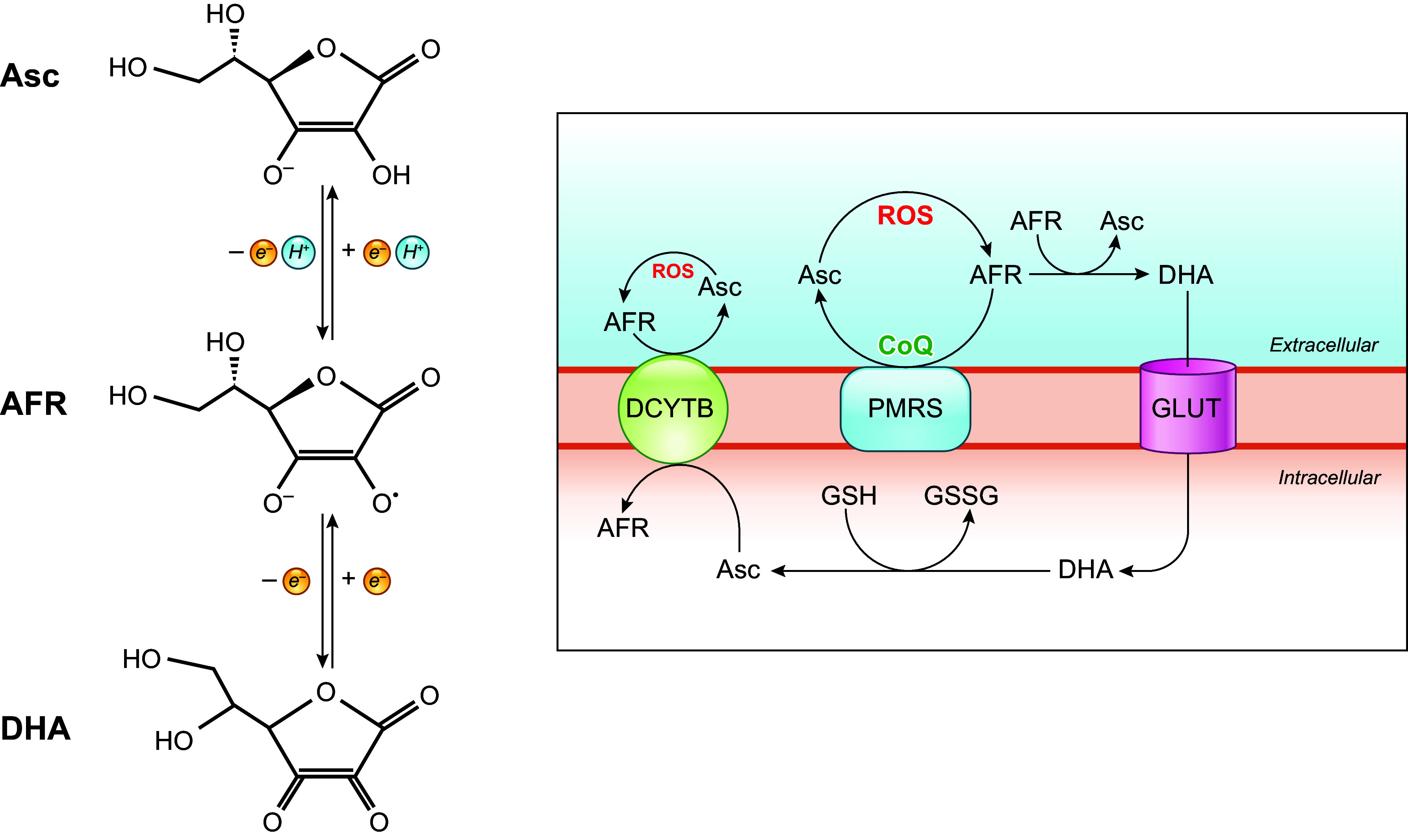

As indicated above, in addition to oxygen, oxidized vitamin C (VC) is one of the extracellular targets of the PMRS. Vitamin C, also known as ascorbic acid or ascorbate (Asc), is the most abundant water-soluble antioxidant in the extracellular fluid. Because of its low redox potential (+0.282 V at pH 7), Asc can readily donate electrons to stabilize free radicals (266). Asc reacts with all kinds of biologically generated radicals (267). It is a particularly effective scavenger of aqueous peroxyl radicals (•OH), with a rate constant of 7.9 × 109 M−1 s−1 to 1.1 × 1010 M−1 s−1 (268, 269), although, according to its rate constant toward O2•− (2.7 × 105 M−1 s−1), it is not an effective scavenger of O2•−. Nonetheless, the reaction between O2•− and Asc is likely to happen in vivo given the abundance of Asc in tissues (270–272). For its antioxidant action, Asc preferably serves as a one-electron donor, generating a relatively stable AFR (also written as Asc•−) (FIGURE 9) (273, 274). Losing the second electron from AFR leads to its transformation into dehydroascorbic acid (DHA). Asc cycles predominantly between the fully reduced form and AFR. DHA is produced mainly by disproportionation of AFR, reactions of 2 AFR to yield 1 DHA and 1 ascorbate molecule (FIGURE 9) (275). More importantly, as AFR is the major product of Asc oxidation, the ability to recycle AFR back to the reduced form is most crucial for the regeneration of antioxidant Asc. As indicated above, in addition to oxygen, AFR is a terminal electron acceptor in the PMRS as well. Thus, the CoQ-dependent PMRS serves to reduce AFR in the extracellular space and restore the Asc pool. But other mechanisms have also been identified. DHA produced extracellularly can be transported into the cell, where it can be reduced back to Asc, for example by glutathione-dependent DHA reductase (275, 276). In human erythrocytes, it was shown that DCYTB can contribute to extracellular Asc recycling by using intracellular Asc as an electron donor (FIGURE 9) (277–279). Moreover, Asc export to the extracellular space has been reported, which could help replenish the Asc pool (277, 278).

FIGURE 9.

Redox metabolism of ascorbate. Ascorbate (Asc) can undergo 2 consecutive 1-electron oxidations that generate the ascorbyl free radical (AFR) as an intermediate and the complete oxidation product dehydroascorbate (DHA). Free radical-mediated oxidative stress results in the oxidation of Asc, yielding AFR. The CoQ-dependent plasma membrane redox system (PMRS) transfers reducing equivalents from intracellular electron donors to AFR outside of the cell, converting AFR back to reduced Asc. Two molecules of AFR can react with each other to form 1 DHA and 1 Asc. DHA made extracellularly can be transported through glucose transporters (GLUT) into the cell, where it can be recycled back to Asc using glutathione (GSH) as a reductant, yielding glutathione disulfide (GSSG). Extracellular AFR can also be reduced by duodenal cytochrome b (DCYTB) using intracellular Asc as an electron donor in some species and tissues. See glossary for other abbreviations.

A number of experimental findings point to an important role of the CoQ-dependent PMRS in ascorbate regeneration. CoQ extraction (with heptane) from lyophilized plasma membranes (from pig liver or K562 human leukemia cells) results in inhibition of NADH-ascorbate free radical (AFR) reductase (250). Incorporation of CoQ10 stimulates NADH-AFR reductase activity, and supplementation of K562 cells with CoQ10 is associated with a dose-dependent increase of extracellular ascorbate stabilization, which indicates a higher rate of plasma membrane AFR reduction (280–282). Furthermore, a yeast coq3 mutant defective in CoQ6 production was documented to have diminished NADH-AFR reductase activity and reduced extracellular ascorbate stabilization, and both activities were rescued after restoration of CoQ6 levels (283, 284). However, the physiological and pathological significance of the plasma membrane CoQ in contributing to extracellular antioxidant defense by allowing ascorbate regeneration needs further study and clarification.

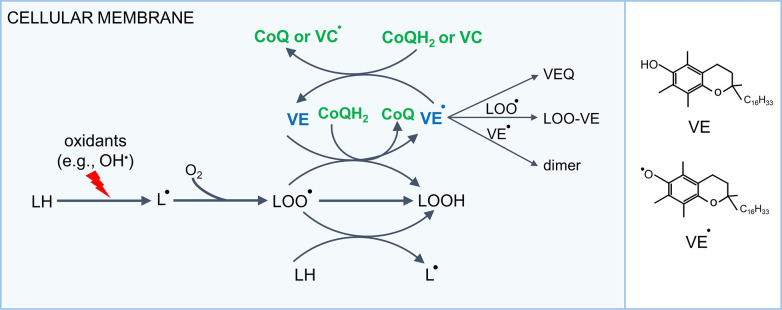

3.2.2.2. role of coq in vitamin e regeneration.

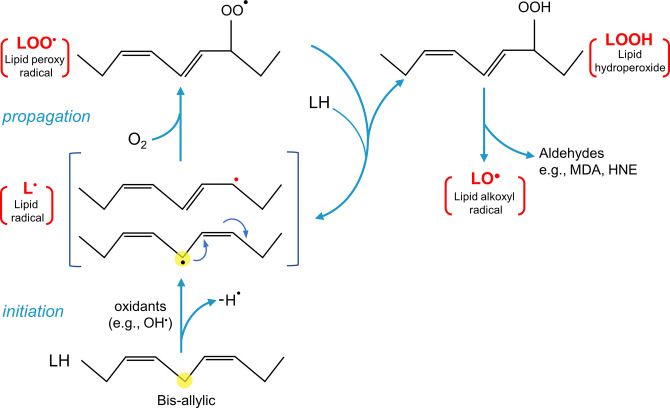

CoQ is also believed to play a role in regenerating another primary exogenous antioxidant: vitamin E (VE), also known as α-tocopherol. Like CoQ, VE is lipophilic and located in membranes and lipoprotein fractions (285). A role for VE in membrane structural stabilization has been generally recognized, although how it is achieved is not yet well defined (286). Another important function of vitamin E is to act as an antioxidant protecting membrane lipids against peroxidation by scavenging lipid radicals.