Abstract

Classes de Recomendação

Classe I: Condições para as quais há evidências conclusivas e, na sua falta, consenso geral de que o procedimento é seguro e útil/eficaz.

Classe II: Condições para as quais há evidências conflitantes e/ou divergência de opinião sobre a segurança e utilidade/eficácia do procedimento.

Classe IIa: Peso ou evidência/opinião a favor do procedimento. A maioria aprova.

Classe IIb: Segurança e utilidade/eficácia menos estabelecidas, havendo opiniões divergentes.

Classe III: Condições para as quais há evidências e/ou consenso de que o procedimento não é útil/eficaz e, em alguns casos, pode ser prejudicial.

Níveis de Evidência

Nível A: Dados obtidos a partir de múltiplos estudos randomizados de bom porte, concordantes e/ou de metanálise robusta de estudos randomizados.

Nível B: Dados obtidos a partir de metanálise menos robusta, a partir de um único estudo randomizado e/ou de estudos observacionais.

Nível C: Dados obtidos de opiniões consensuais de especialistas.

| Diretriz Brasileira de Ergometria em Crianças e Adolescentes – 2024 | |

|---|---|

| O relatório abaixo lista as declarações de interesse conforme relatadas à SBC pelos especialistas durante o período de desenvolvimento deste posicionamento, 2023-2024. | |

| Especialista | Tipo de relacionamento com a indústria |

| Andréa Maria Gomes Marinho Falcão | Nada a ser declarado |

| Antonio Carlos Avanza Júnior | Nada a ser declarado |

| Carlos Alberto Cordeiro Hossri | Nada a ser declarado |

| Carlos Alberto Cyrillo Sellera | Nada a ser declarado |

| José Luiz Barros Pena | Nada a ser declarado |

| Luiz Eduardo Fonteles Ritt | Declaração financeira

A - Pagamento de qualquer espécie e desde que economicamente apreciáveis, feitos a (i) você, (ii) ao seu cônjuge/ companheiro ou a qualquer outro membro que resida com você, (iii) a qualquer pessoa jurídica em que qualquer destes seja controlador, sócio, acionista ou participante, de forma direta ou indireta, recebimento por palestras, aulas, atuação como proctor de treinamentos, remunerações, honorários pagos por participações em conselhos consultivos, de investigadores, ou outros comitês, etc. Provenientes da indústria farmacêutica, de órteses, próteses, equipamentos e implantes, brasileiras ou estrangeiras: - Boehringer Lilly: Jardiance; Novonordis: pesquisador em estudos; AstraZeneca; Novartis; Bayer; Bristol; Pfizer. B - Financiamento de pesquisas sob sua responsabilidade direta/pessoal (direcionado ao departamento ou instituição) provenientes da indústria farmacêutica, de órteses, próteses, equipamentos e implantes, brasileiras ou estrangeiras: - MDI Medical. Outros relacionamentos Financiamento de atividades de educação médica continuada, incluindo viagens, hospedagens e inscrições para congressos e cursos, provenientes da indústria farmacêutica, de órteses, próteses, equipamentos e implantes, brasileiras ou estrangeiras: - Novo Nordisk: Ozempic |

| Maria Eulália Thebit Pfeiffer | Nada a ser declarado |

| Mauricio Milani | Nada a ser declarado |

| Odilon Gariglio Alvarenga de Freitas | Nada a ser declarado |

| Odwaldo Barbosa e Silva | Nada a ser declarado |

| Ricardo Vivacqua Cardoso Costa | Nada a ser declarado |

| Rodrigo Imada | Nada a ser declarado |

| Susimeire Buglia | Nada a ser declarado |

| Tales de Carvalho | Nada a ser declarado |

| William Azem Chalela | Nada a ser declarado |

Parte 1 – Indicações, Aspectos Legais e Formação em Ergometria

1. Introdução

O Teste Ergométrico ou Teste de Exercício (TE) é um exame médico complementar, no qual o indivíduo é submetido a um esforço físico programado e individualizado, com a finalidade de avaliar as respostas clínica, hemodinâmica, autonômica, eletrocardiográfica, metabólica indireta e eventualmente enzimática. Recebe a denominação de Teste Cardiopulmonar de Exercício (TCPE) quando são adicionados ao TE parâmetros ventilatórios e a análise dos gases no ar expirado. A denominação Ergometria contempla o TE e o TCPE. 1

Em crianças e adolescentes, o TE e o TCPE são métodos de avaliação diagnóstica, prognóstica e do desempenho cardiorrespiratório em diversas situações clínicas. São procedimentos considerados seguros e de custo-efetividade comprovada na população pediátrica. 1

No Brasil, as anomalias congênitas e as doenças cardiovasculares (DCV) representam nas crianças, respectivamente, a segunda e a nona causa de morte. Nos adolescentes, as DCV são a terceira maior causa de morte, e as anomalias congênitas são a oitava causa. Esses dados demonstram a importância do cuidado da saúde cardiovascular (CV) na população pediátrica. 2

O Ministério da Saúde do Brasil segue como definição de adolescência a prescrita pela Organização Mundial da Saúde (OMS), que caracteriza o período de vida entre 10 e 19 anos. Entretanto, a legislação brasileira considera como adolescente a pessoa que estiver na faixa etária entre 12 e 18 anos. Publicações científicas também adotam outras faixas etárias para crianças (1 a 13 anos) e adolescentes (13 a 18 anos). 3 – 5

Esta diretriz buscou consolidar as informações mais recentes das publicações científicas sobre TE/TCPE em crianças e adolescentes quanto às indicações, contraindicações, riscos, aspectos metodológicos, respostas hemodinâmicas e eletrocardiográficas, critérios diagnósticos e particularidades dos exames em doenças específicas na população pediátrica. Adicionalmente, foram abordadas as variáveis ventilatórias e metabólicas provindas da análise dos gases expirados no TCPE e, também, TE e TCPE associados a métodos de imagem.

Ao longo do documento, enfatizamos as particularidades dos exames considerando a faixa etária do paciente, sexo, composição corporal, níveis de aptidão física e estados de saúde CV e pulmonar basais. 6 – 12

A presente diretriz tem o potencial de se tornar forte referência e relevante fonte de consultas para os cardiologistas, visando à difusão do TE e do TCPE na perspectiva de aprimorar a saúde CV de crianças e adolescentes.

2. Indicações e Contraindicações do TE e do TCPE em Crianças e Adolescentes

2.1. Indicações Gerais do TE

O TE na população pediátrica é uma ferramenta que contribui para o diagnóstico e avaliação da repercussão de DCV (congênitas, genéticas e adquiridas), estratificação de risco, determinação de prognóstico, ajustes terapêuticos e liberação/prescrição de exercícios, inclusive na reabilitação cardiovascular (RCV).

As indicações e objetivos gerais do TE na população pediátrica são: 6 – 12

Avaliar sintomas relacionados ao esforço.

Avaliar o comportamento hemodinâmico [pressão arterial (PA), frequência cardíaca (FC), duplo-produto (DP), resistência arterial periférica etc.].

Identificar respostas anormais ao esforço em crianças e adolescentes com DCV congênitas e adquiridas (valvopatias, cardiomiopatias etc.), pulmonares ou de outros órgãos.

Detectar isquemia miocárdica decorrente de anomalias coronárias congênitas, ateromatose (muito rara) ou no contexto da doença de Kawasaki.

Reconhecer as arritmias cardíacas quanto ao tipo, densidade e complexidade.

Avaliar o comportamento da pré-excitação e canalopatias ao esforço.

Estabelecer o prognóstico em determinadas DCV, inclusive através de exames seriados.

Na indicação e ajustes terapêuticos.

Avaliar a condição aeróbica, a tolerância ao esforço e o condicionamento físico.

Fornecer subsídios para a liberação e prescrição de exercícios físicos, incluindo RCV e atividades esportivas.

2.2. Indicações do TE em Situações Clínicas Específicas

Apresentaremos as situações clínicas específicas nas quais o TE tem sua efetividade estudada e testada, permitindo determinar o grau de indicação e nível de recomendação estabelecidos na literatura.

2.2.1. Na Suspeita de Isquemia Miocárdica e Doença Arterial Coronariana

Em crianças e adolescentes, a isquemia miocárdica e doença arterial coronariana (DAC) apresentam etiologias diferentes das encontradas nos adultos. Nesse contexto, o TE apresenta reconhecida utilidade na investigação diagnóstica, no seguimento, em decisões terapêuticas e na estratificação de risco ( Tabela 1 ). 6 , 13 , 14

Tabela 1. Indicações do TE na suspeita de isquemia miocárdica e doença arterial coronariana em crianças e adolescentes.

| Indicação | GR | NE |

|---|---|---|

| Na doença de Kawasaki, para investigação de arritmias esforço-induzidas, avaliação funcional, quantificação de repercussão de lesões coronarianas, estratificação de risco e liberação para exercícios. 15 – 18 | I | B |

| Investigação de queixa de dor torácica anginosa típica. 6 , 13 , 14 , 19 , 20 | I | C |

| Avaliação de isquemia miocárdica residual e tolerância ao esforço após o tratamento cirúrgico para correção da transposição das grandes artérias. 21 – 23 | I | C |

| Após cirurgia em artéria coronária (operação de troca arterial, procedimento de Ross, substituição da aorta ascendente, correção da síndrome de Bland-White-Garland), para detecção de isquemia miocárdica e arritmias esforço-induzidas e liberação de exercícios incluindo RCV. 6 , 24 – 27 | IIa | B |

| Nas anomalias das artérias coronárias para triagem, investigação de isquemia esforço-induzida, indicação de correção cirúrgica e liberação para exercícios físicos. 28 , 29 | IIa | B |

| Avaliação da capacidade funcional e decisão terapêutica de paciente em que outro método tenha detectado isquemia miocárdica. 6 , 30 | IIb | B |

| Na ponte miocárdica, para investigação de sintomas e arritmias esforço-induzidas e estratificação de risco. 31 , 32 | IIb | B |

| Seguimento de pacientes com arterite de Takayasu ou lúpus eritematoso sistêmico, para investigação de doença arterial coronariana secundária. 33 , 34 | IIb | C |

| Diagnóstico de DAC em pacientes com BRE, WPW, ritmo de MP e terapêutica com digitálicos. | III | B |

| Investigação de dor torácica tipicamente não anginosa. 13 , 35 , 36 | III | B |

| Na doença de Kawasaki, TE sem outro método associado, para avaliação de isquemia miocárdica. 37 | III | C |

GR: grau de recomendação; NE: nível de evidência; RCV: reabilitação cardiovascular; DAC: doença arterial coronariana; BRE: bloqueio de ramo esquerdo; WPW: síndrome de Wolff-Parkinson-White; MP: marca-passo; TE: teste ergométrico.

2.2.2. Indicações na Hipertensão Arterial Sistêmica

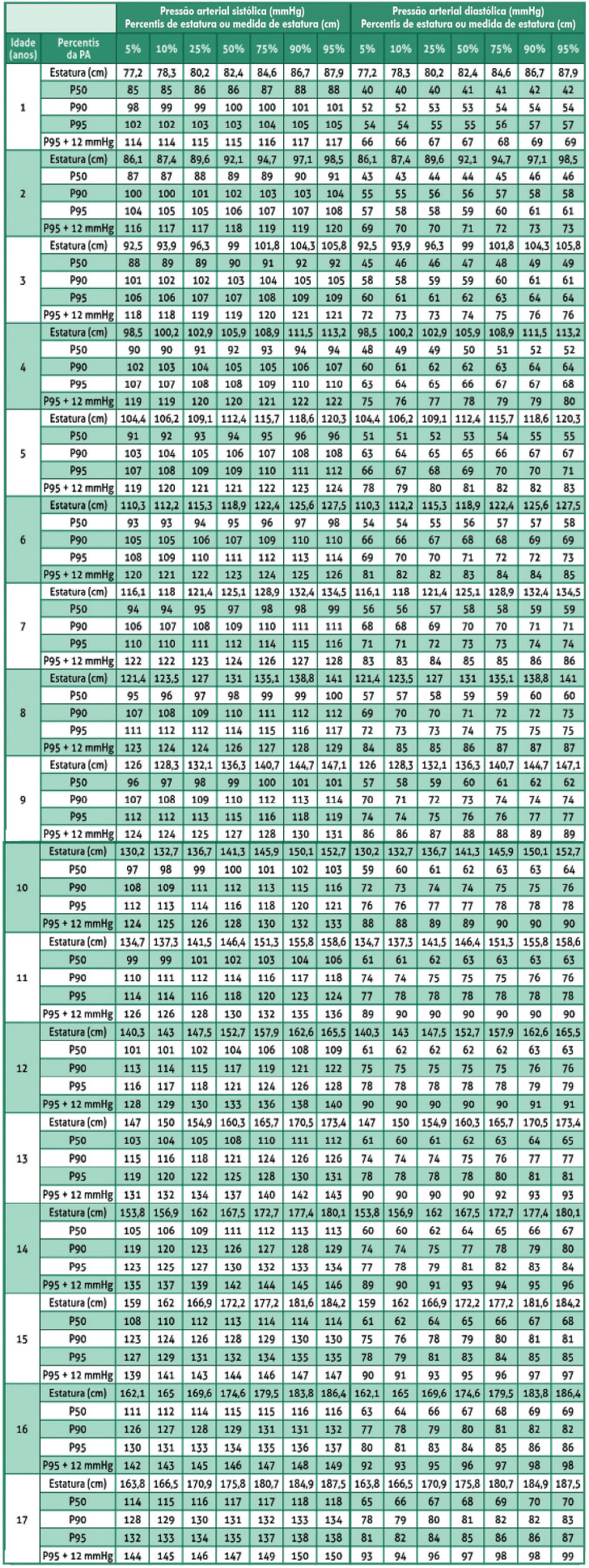

O TE permite a avaliação do comportamento pressórico ao esforço e diagnóstico de hipertensão arterial na população pediátrica, com e sem cardiopatia congênita (CC). O comportamento da pressão arterial (PA) durante o TE tem poder preditivo adicional às medidas esporádicas no consultório ( Tabela 2 ). 38

Tabela 2. Indicações do TE na hipertensão arterial sistêmica em crianças e adolescentes.

| Indicação | GR | NE |

|---|---|---|

| Avaliação do comportamento da PA ao esforço (com ou sem cardiopatia) para diagnóstico de HAS. 41 – 43 | I | C |

| Avaliação pré-participação de hipertensos para esporte competitivo. 44 , 45 | I | B |

| Suspeita de hipertensão do avental branco. 41 , 46 | IIa | B |

| Avaliação da resposta terapêutica e estratificação de risco em hipertensos. 4 , 47 , 48 | IIa | B |

| Após correção de coarctação da aorta, para avaliação do comportamento pressórico, índice tornozelo-braquial pós-esforço e estratificação de risco de hipertensão. * 8 , 49 – 51 | IIa | B |

| Suspeita de hipertensão mascarada em adolescente. 41 , 52 , 53 | IIa | C |

| Avaliação de pacientes com HAS descompensada. 11 | III | C |

GR: grau de recomendação; NE: nível de evidência; PA: pressão arterial; HAS: hipertensão arterial sistêmica.

Exame associado adicionalmente ao TE em esteira ergométrica com avaliação do índice tornozelo-braquial em repouso e pós-esforço.

A hipertensão na infância está relacionada ao risco elevado de DCV, aterosclerose, hipertrofia ventricular esquerda (HVE) e insuficiência renal no adulto. 39 , 40

2.2.3. Indicações em Assintomáticos

Estudos realizados nos últimos anos vêm elucidando o papel do TE na avaliação de pacientes pediátricos assintomáticos e em relação à sua utilidade na estratificação de risco e determinação prognóstica ( Tabela 3 ).

Tabela 3. Indicações do TE em crianças e adolescentes assintomáticos.

| Indicação | GR | NE |

|---|---|---|

| Triagem e acompanhamento nas hiperlipidemias genéticas e/ou presença de aterosclerose carotídea. 54 – 56 | IIa | B |

| História familiar de morte súbita inexplicada em indivíduos jovens. 57 , 58 | IIa | B |

| Assintomáticos com fatores de risco cardiometabólico na avaliação da aptidão cardiorrespiratória. * 59 – 61 | IIa | C |

| Assintomáticos, aparentemente saudáveis, em avaliação pré-participação de exercício físico como lazer e/ou esporte recreacional. 62 | III | C |

GR: grau de recomendação; NE: nível de evidência.

Vide estratificação de risco pré-TE (Parte 2, Sessão 2).

2.2.4. Indicações em Atletas

O TE em crianças e adolescentes atletas permite avaliar a aptidão cardiorrespiratória (ACR), o comportamento hemodinâmico e o diagnóstico/repercussão de eventuais DCV ( Tabela 4 ). 8 , 63 , 64

Tabela 4. Indicações do TE em crianças e adolescentes atletas.

| Indicação | GR | NE |

|---|---|---|

| Investigação de sintomas relacionados ao esforço. 8 , 64 | I | A |

| Doenças e condições de alto risco de morte súbita cardíaca. 64 – 66 | I | C |

| Diagnóstico e seguimento de asma esforço-induzida. 67 , 68 | IIa | B |

| Diagnóstico e seguimento de hipertensão arterial sistêmica. 44 , 53 , 69 | IIa | B |

| Diabetes tipo I para investigação de sintomas, avaliação da aptidão cardiorrespiratória e estratificação de risco. 70 – 72 | IIa | B |

| Diagnóstico e seguimento de cardiomiopatias. 73 , 74 | IIa | B |

| Avaliação pré-participação de esporte competitivo em assintomáticos, sem fatores de risco e aparentemente saudáveis. 8 | III | B |

GR: grau de recomendação; NE: nível de evidência.

2.2.5. Indicações nas Cardiopatias Congênitas

A prevalência mundial de CC varia entre 2,4 e 13,7 por 1.000 nascidos vivos, sendo que a maioria (85%) atinge a idade adulta. 75 , 76 Habitualmente, as crianças com CC, mesmo quando reparadas, são menos ativas fisicamente, inclusive por superproteção familiar. 77 , 78 Até 15 a 20% dos pacientes com CC apresentam algum comprometimento valvar, sendo as valvopatias isoladas aórtica (bicúspide, estenótica) e pulmonar as mais comuns. 79 – 81

O TE é recomendado para avaliação clínica, determinação da ACR, decisões terapêuticas, seguimento, estratificação de risco/prognóstico e liberação/prescrição de programas de exercícios, inclusive na RCV ( Tabela 5 ). 7 , 9 , 82 – 85

Tabela 5. Indicações do TE nas cardiopatias congênitas em crianças e adolescentes.

| Indicação | GR | NE |

|---|---|---|

| Avaliação da aptidão cardiorrespiratória e estratificação de risco/prognóstico na CC acianótica, pré e pós-operatório de cirurgia corretiva. 7 , 10 , 86 , 87 | IIa | B |

| Avaliação da aptidão cardiorrespiratória e estratificação de risco/prognóstico na CC cianótica após cirurgia corretiva. 7 , 86 , 87 | IIa | B |

| Avaliação do comportamento de arritmia e estratificação de risco. 82 , 83 , 88 | IIa | B |

| Prescrição e adequação de programa de exercícios, incluindo programa de reabilitação cardiovascular. 89 , 90 | IIa | B |

| Após cirurgia de Fontan, para avaliação da aptidão cardiorrespiratória e estratificação de risco/prognóstico. 84 , 91 , 92 | IIa | B |

| IC compensada após tratamento intervencionista para ajustes terapêuticos, estratificação de risco/prognóstico e liberação/prescrição de reabilitação cardiovascular. 93 , 94 | IIa | B |

| Avaliação de sintomas desencadeados ou agravados pelo esforço. 95 , 96 | IIa | C |

| Em assintomáticos, após reparo de tetralogia de Fallot, para avaliação de eventual substituição da valva pulmonar. 97 , 98 | IIb | B |

| Na tetralogia de Fallot reparada, para estratificação de risco/prognóstico. 99 , 100 | IIb | B |

| Na transposição corrigida das grandes artérias, para avaliação da aptidão cardiorrespiratória e estratificação de risco/prognóstico. 101 , 102 | IIb | B |

| Na doença de Fabry, para avaliação da aptidão cardiorrespiratória. 103 , 104 | IIb | B |

| Avaliação do grau de dessaturação com o esforço na CC cianótica clinicamente estável. * 7 | IIb | B |

| CC com IC descompensada. | III | C |

| CC cianótica descompensada. | III | C |

GR: grau de recomendação; NE: nível de evidência; CC: cardiopatia congênita; IC: insuficiência cardíaca.

Recomenda-se realizar exame adicional de monitorização oximétrica não invasiva concomitantemente ao TE.

2.2.6. Indicações no Contexto das Arritmias e Distúrbios de Condução

O TE está indicado no contexto das arritmias e distúrbios de condução em crianças e adolescentes para a avaliação de sintomas, diagnóstico de arritmias, definição de condutas terapêuticas, estratificação de risco e prescrição de exercícios físicos ( Tabela 6 ). 9 , 11 , 105 – 109

Tabela 6. Indicações do TE no contexto das arritmias e distúrbios de condução em crianças e adolescentes.

| Indicação | GR | NE |

|---|---|---|

| Palpitação, síncope, pré-sincope, equivalente sincopal, mal-estar indefinido ou palidez relacionada ao esforço físico e/ou imediatamente após. 105 , 110 , 111 | I | B |

| Na suspeita de taquicardia ventricular paroxística catecolaminérgica. 112 , 113 | I | B |

| No BAVT congênito, para avaliação da resposta ventricular e consequente indicação de implante de marca-passo. 114 , 115 | I | B |

| No BAVT congênito, para escolha do tipo de marca-passo através da avaliação da resposta da frequência atrial. 116 , 117 | I | C |

| Avaliação e diagnóstico de disfunção do nó sinusal secundária a CC ou após correção cirúrgica. 118 , 119 | IIa | B |

| Eficácia da terapêutica farmacológica e/ou ablação de arritmia. 7 , 120 , 121 | IIa | B |

| Arritmia conhecida e controlada, para liberação e prescrição de exercícios físicos (incluindo reabilitação cardiovascular). 122 , 123 | IIa | B |

| Na síndrome do QT longo, para confirmação diagnóstica, estratificação de risco, avaliação de potencial arritmogênico e ajustes terapêuticos. 57 , 109 , 124 | IIa | B |

| Na suspeita de síndrome de Brugada, para auxílio diagnóstico e estratificação de risco. 125 – 127 | IIa | B |

| Avaliação da resposta da frequência cardíaca em portador de marca-passo com biossensor. 7 , 116 , 120 , 128 | IIa | C |

| Avaliação do comportamento de via anômala (pré-excitação) e do potencial arritmogênico. 7 , 120 , 121 | IIb | B |

| Portador de marca-passo de frequência fixa. | III | B |

| BAVT não congênito. | III | B |

| Avaliação de extrassístoles atriais e/ou ventriculares isoladas em crianças e adolescentes aparentemente saudáveis, sem comorbidades ou queixas. 7 , 120 , 129 | III | C |

| Arritmia não controlada, sintomática ou com comprometimento hemodinâmico. | III | C |

GR: grau de recomendação; NE: nível de evidência; BAVT: bloqueio atrioventricular total; CC: cardiopatia congênita.

2.2.7. Indicações em Valvopatias nas Crianças e Adolescentes

As valvopatias representam importante porcentagem das doenças cardíacas na população pediátrica, seja de origem congênita ou adquirida. A doença cardíaca reumática (DCR) e seu comprometimento valvar é uma das principais causas de morbidade e mortalidade cardíaca entre crianças nos países subdesenvolvidos e em desenvolvimento. Em 2019, cerca de 40 milhões de casos de DCR foram relatados em todo o mundo, com 2.789.443 novos casos e 305.651 mortes anualmente. 130 , 131

A valvopatia pode gerar distúrbios hemodinâmicos dependendo do grau de acometimento valvar e miocárdico. As lesões estenóticas geralmente cursam com sobrecarga de pressão da câmara cardíaca envolvida, enquanto as lesões regurgitantes acarretam sobrecarga de volume. Muitas lesões são mistas, resultando em sobrecarga de pressão e volume, com potencial para desenvolvimento de insuficiência cardíaca (IC). Também é comum a ocorrência de valvopatias secundárias à cardiomiopatias adquiridas, miocardites e IC. Evolutivamente, o aumento do estresse da parede ventricular causa estiramento e fibrose miocárdica, resultando em cicatrizes com potencial arritmogênico. As arritmias podem complicar o quadro clínico da valvopatia e aumentar a morbimortalidade nas crianças e adolescentes. 132 – 134

A Tabela 7 apresenta as indicações do TE em valvopatias específicas em crianças e adolescentes e os respectivos graus de recomendação.

Tabela 7. Indicações do TE em valvopatias nas crianças e adolescentes.

| Indicação | GR | NE |

|---|---|---|

| Em valvopatia discreta/moderada para avaliação de sintomas, arritmias, aptidão cardiorrespiratória e liberação de exercícios físicos. 81 , 135 | I | B |

| EAo, EAo supravalvular e estenose subaórtica, para avaliação de sintomas, na estratificação de risco e definição de intervenção. 81 , 134 , 136 | IIa | B |

| IAo compensada, moderada a grave, para avaliação de sintomas e aptidão cardiorrespiratória, indicação de intervenção e liberação de exercícios. 137 , 138 | IIa | B |

| Valva aórtica bicúspide, para avaliação da resposta inotrópica e estratificação de risco. 62 , 139 | IIa | B |

| Pós-intervenção valvar, para avaliação de sintomas, aptidão cardiorrespiratória, prognóstico e liberação de exercícios. 140 , 141 | IIa | B |

| EAo ou mitral grave sintomática, para avaliação da aptidão cardiorrespiratória. | III | B |

GR: grau de recomendação; NE: nível de evidência; IAo: insuficiência aórtica; EAo: estenose aórtica.

2.2.8. Indicações em Crianças e Adolescentes com Cardiopatias Adquiridas e Cardiomiopatias

As cardiomiopatias em crianças abrangem uma ampla gama de doenças que se manifestam como doença primária ou secundária a doenças sistêmicas (exemplos: distúrbio neuromuscular, secundária a HIV e COVID-19). 142 – 144

As cardiomiopatias têm incidência anual estimada de 1,1 a 1,5 casos por 100.000 pacientes da faixa etária de 0 a 18 anos. 145 Podem cursar com IC sistólica e/ou diastólica progressivas. A IC afeta 0,87 a 7,4 por 100.000 crianças e tem uma mortalidade em 5 anos de 40%. 146 Nesses pacientes e nos recuperados de miocardites, o TE é indicado no acompanhamento clínico, decisões terapêuticas e prescrição/adequação de programa de exercícios ( Tabela 8 ). 6 , 143 , 147 , 148

Tabela 8. Indicações do TE em crianças e adolescentes com cardiopatias adquiridas e cardiomiopatias.

| Indicação | GR | NE |

|---|---|---|

| Jovens recuperados de miocardite (incluindo viral), após 6 meses, para avaliação de arritmias esforço-induzidas. 62 , 149 , 150 | IIa | B |

| IC compensada secundária a cardiopatia para avaliação prognóstica, ajustes terapêuticos e liberação/prescrição de exercícios (incluindo reabilitação cardiovascular). 151 – 153 | IIa | B |

| Cardiomiopatia hipertrófica, para avaliação da aptidão cardiorrespiratória e de marcadores prognósticos (sintomas, arritmia ventricular e resposta inotrópica). 154 – 157 | IIa | B |

| Nas cardiomiopatias compensadas (exemplos: doença de Chagas e amiloidose), para seguimento e ajustes terapêuticos. 158 , 159 | IIb | B |

| Após transplante cardíaco, para avaliação da aptidão cardiorrespiratória, liberação/prescrição de programa de exercícios (incluindo reabilitação cardiovascular). 160 , 161 | IIb | B |

| Miocardite e pericardite agudas ou IC descompensada. | III | B |

| Diagnóstico de insuficiência cardíaca. | III | C |

| Seleção para transplante cardíaco pelo TE (com base nos valores de VO2 estimados e não medidos). | III | C |

GR: grau de recomendação; NE: nível de evidência; IC: insuficiência cardíaca; VO2: consumo de oxigênio; TE: teste ergométrico.

2.2.9. Outras Situações Clínicas em Crianças e Adolescentes

Há outras situações clínicas em que o TE está indicado no diagnóstico, avaliar a ACR e o estado hemodinâmico, auxiliar nas decisões terapêuticas e estratificar o risco em doenças específicas ( Tabela 9 ).

Tabela 9. Indicações do TE em outras situações clínicas de crianças e adolescentes.

| Indicação | GR | NE |

|---|---|---|

| Na suspeita de asma e obstrução laríngea esforço-induzidas e adequação de programa de exercícios. 162 – 164 | IIa | B |

| Após pelo menos 6 meses de miocardite ou pericardite recuperadas (incluindo por COVID-19), para avaliação pré-participação/liberação de prática de esportes. 150 , 165 , 166 | IIa | B |

| Anemia falciforme, para esclarecimento de sintomas, avaliar a aptidão cardiorrespiratória e liberar/prescrever exercícios físicos. 167 , 168 | IIa | C |

| Na hipertensão arterial pulmonar primária, para avaliação de sintomas, aptidão cardiorrespiratória e estratificação de risco/prognóstico. 169 , 170 | IIb | B |

| Pacientes em hemodiálise e pós-transplante renal, para prescrição e adequação de programa de exercícios (incluindo reabilitação cardiovascular). 171 – 173 | IIb | B |

| Avaliação de risco e prognóstico em pacientes oncológicos com suspeita de cardiotoxicidade. 104 , 174 , 175 | IIb | B |

| Após pelo menos 6 meses de recuperação de síndrome inflamatória multissistêmica (incluindo miocardite e pericardite) secundária a COVID-19. 150 , 165 | IIb | C |

GR: grau de recomendação; NE: nível de evidência.

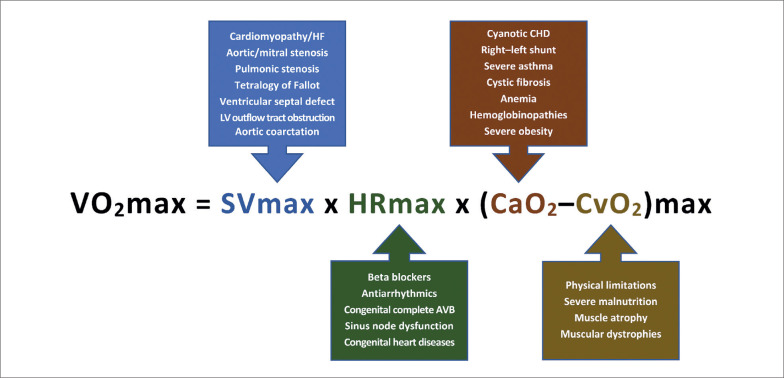

2.3. Indicações do TCPE nas Crianças e Adolescentes

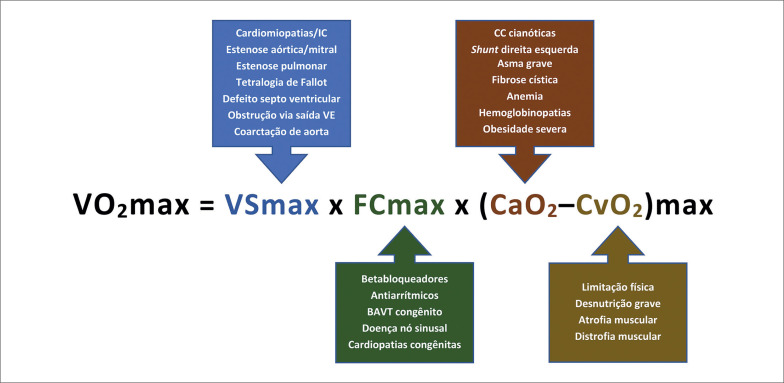

O TCPE, além das informações obtidas no TE, possibilita a avaliação dos volumes pulmonares (ergoespirometria) e a análise dos gases no ar expirado com a mensuração direta do consumo de oxigênio (VO2) e produção de dióxido de carbono (VCO2). 100 , 176 , 177 Dessa forma, o TCPE pode ajudar a identificar a fisiopatologia da dispneia inexplicável, identificar características fisiopatológicas específicas de doenças e fornecer informações relevantes para decisões terapêuticas. 11 , 178

Temos como indicações gerais do TCPE em crianças e adolescentes: 100 , 176 – 178

Todas as indicações do TE descritas nesta diretriz em que seja necessária a quantificação das variáveis ventilatórias e metabólicas de maneira direta.

Aprimoramento da avaliação de sinais e/ou sintomas cardiorrespiratórios esforço-induzidos (dispneia, estridor laríngeo, sibilos etc.).

Avaliação aprimorada de doenças cardíacas (CC, valvopatias, IC, cardiomiopatias, arritmias), pulmonares e de outros órgãos (anemia falciforme, insuficiência renal, doenças neurodegenerativas etc.).

Contribuição para indicação e seguimento de tratamentos cirúrgicos específicos.

Avaliação da eficácia e ajustes terapêuticos.

Avaliação da ACR na indicação de transplante cardíaco.

Avaliação pré-participação e seguimento no esporte competitivo.

Avaliação prognóstica nas doenças cardiovasculares, pulmonares e em outros órgãos.

Pré-participação e seguimento na RCV.

As indicações específicas do TCPE e respectivos graus de recomendação e nível de evidência encontram-se na Tabela 10 .

Tabela 10. Principais indicações específicas para TCPE em crianças e adolescentes.

| Indicação | GR | NE |

|---|---|---|

| Avaliação de aptidão cardiorrespiratória. 176 , 179 | I | A |

| Ajuste de intensidade de treinamento aeróbico em esporte competitivo. 63 , 149 , 177 , 180 , 181 | I | A |

| Liberação e prescrição de exercícios em programa de reabilitação cardiovascular. 141 , 182 – 184 | I | A |

| Seleção de candidatos ao transplante cardíaco. * 185 , 186 | I | A |

| Avaliação de dispneia ou asma esforço-induzidas. 178 , 179 , 187 , 188 | I | B |

| CC cianótica. ** 81 , 100 , 189 | I | B |

| Seguimento após transplante cardíaco. ** 190 – 192 | I | B |

| Doença de Kawasaki e arterite de Takayasu estabilizadas, para avaliação da aptidão cardiorrespiratória e liberação/prescrição de exercícios, incluindo reabilitação cardiovascular. 15 , 17 , 18 , 193 | I | C |

| Lesões assintomáticas de shunt direita-esquerda. ** 184 , 194 , 195 | IIa | A |

| Hipertensão arterial pulmonar. ** 169 , 196 – 198 | IIa | A |

| Lesões valvares regurgitantes moderadas a graves assintomática. ** 81 , 199 , 200 | IIa | B |

| Estenose aórtica grave assintomática. ** 81 , 199 , 200 | IIa | B |

| Fibrose cística, para avaliação da aptidão cardiorrespiratória e prognóstico. 67 , 201 , 202 | IIa | B |

| Doenças neuromusculares (esclerose múltipla, distrofia muscular de Becker e de Duchenne), para avaliação da aptidão cardiorrespiratória e prescrição de exercícios na reabilitação. 203 – 206 | IIa | B |

| Cardiomiopatia hipertrófica obstrutiva moderada assintomática. ** 207 – 209 | IIa | B |

| Avaliação de pacientes em tratamento oncológico na suspeita de cardiotoxicidade, estratificação de risco e liberação/prescrição de exercícios. 104 , 174 , 175 , 210 | IIa | B |

| Lesões obstrutivas leves a moderadas do coração direito. ** 81 , 199 , 211 | IIb | B |

| Após correção cirúrgica de CC, assintomática, estável hemodinamicamente. ** 212 , 213 | IIb | B |

GR: grau de recomendação; NE: nível de evidência; CC: cardiopatia congênita.

Em indivíduos com idade, tamanho corporal, capacidade de compreensão e adaptação/colaboração imprescindíveis à correta realização do exame.

Para avaliação da aptidão cardiorrespiratória, decisões terapêuticas e prognóstico.

2.4. Indicações do TE e TCPE Associados a Métodos de Imagem

2.4.1. Cintilografia de Perfusão Miocárdica

A cintilografia de perfusão miocárdica na população pediátrica tem seu papel estabelecido na avaliação de perfusão/viabilidade miocárdica e função ventricular. Pode ser útil na identificação de isquemia induzível ou residual, anormalidade do movimento de parede ventricular e estratificação de risco ( Tabela 11 ).

Tabela 11. Indicações da cintilografia miocárdica em crianças e adolescentes.

| Indicação | GR | NE |

|---|---|---|

| Avaliação tardia da doença de Kawasaki com comprometimento coronariano (com ou sem sintomas). 18 , 214 – 217 | I | C |

| Seguimento pós-operatório da transposição das grandes artérias, para pesquisa de isquemia miocárdica, estratificação de risco e indicação de reintervenção. 22 , 214 , 220 – 222 | IIa | B |

| Avaliação tardia da doença de Kawasaki sem comprometimento coronariano. 18 , 30 , 214 , 218 , 219 | IIb | B |

| Cardiomiopatia hipertrófica, para pesquisa de isquemia, estratificação de risco e manejo terapêutico. 214 , 223 | IIb | B |

| Pós-transplante cardíaco, para avaliação de doença vascular do enxerto. 214 , 224 , 225 | IIb | C |

| Na tetralogia de Fallot, após cirurgia de Fontan, para identificação de isquemia residual. 225 , 226 | IIb | C |

| Identificação de isquemia/fibrose miocárdica em pacientes com origem anômala da artéria coronária esquerda (origem na artéria pulmonar). 225 , 227 , 228 | IIb | C |

GR: grau de recomendação; NE: nível de evidência.

2.4.2. Indicações da Ecocardiografia sob Estresse

Na população pediátrica, a ecocardiografia sob estresse (EcoE) é mais comumente utilizada para a detecção de isquemia em pacientes com DAC, na doença de Kawasaki e origem anômala de coronárias. Outras indicações pediátricas incluem: pós-transplante cardíaco; cardiopatias congênitas para avaliação da resposta hemodinâmica e miocárdica; detecção precoce de disfunção miocárdica em populações específicas (exemplo: uso de antraciclinas); avaliação da resposta funcional do ventrículo direito (VD) e pressão da artéria pulmonar ( Tabela 12 ). 229 – 233

Tabela 12. Indicações do ecocardiograma sob estresse em crianças e adolescentes com sintomas ou DCV 234 , 235 .

| Indicação | GR | NE |

|---|---|---|

| Pesquisa de insuficiência coronária em crianças pós-transplante cardíaco tardio. 160 , 236 – 238 | IIa | B |

| Avaliação tardia da doença de Kawasaki com comprometimento coronariano. 239 , 240 | IIa | B |

| No pós-operatório de cirurgia de Jatene, de origem e trajetos anormais das artérias coronárias e de fístulas coronário-cavitárias. 241 , 242 | IIa | B |

| Avaliação da função ventricular nas cardiomiopatias e nas insuficiências valvares (mitral e aórtica). 229 , 232 , 243 | IIa | B |

| Pacientes oncológicos com suspeita de cardiotoxicidade, para avaliação da função ventricular. 233 , 244 , 245 | IIa | B |

| Avaliação da função ventricular no pós-transplante. 160 , 237 , 238 , 246 | IIa | B |

| Pacientes sob risco de doença coronariana aterosclerótica precoce (hipercolesterolemia familiar homozigótica, diabetes mellitus I etc.). 247 , 248 | IIb | B |

| Pesquisa de insuficiência coronária na atresia pulmonar com septo ventricular íntegro ou estenose aórtica supravalvar. 229 , 249 | IIb | B |

| Avaliação do gradiente de pressão na cardiomiopatia hipertrófica e nas estenoses valvares (pulmonar e aórtica). 229 , 231 , 250 , 251 | IIb | B |

| Avaliação pós-operatória de cirurgias em plano atrial para transposição dos grandes vasos e de correção da tetralogia de Fallot. 222 , 252 , 253 | IIb | B |

GR: grau de recomendação; NE: nível de evidência.

2.5. Contraindicações Relativas e Absolutas do TE e TCPE em Crianças e Adolescentes

O TE/TCPE em população pediátrica não é um exame isento de riscos de complicações ou eventos adversos. Em algumas situações clínicas, o risco dos exames atinge uma magnitude que supera o benefício das informações obtidas, contraindicando-os. O TE em população pediátrica tem baixa morbidade e mortalidade, sendo que a incidência geral de complicações varia entre 0,5 e 1,79%. 7 , 11 , 254 , 255 As complicações mais frequentes: dor torácica (0,69%), tontura ou síncope (0,29%), hipotensão (0,35%) e arritmias graves (0,46%). 254 Em crianças e adolescentes com CC, a incidência de taquicardia ventricular (TV) variou de 1,9 a 7,3%. 256 , 257

2.5.1. Contraindicações Relativas do TE e TCPE em Crianças e Adolescentes

São situações clínicas de alto-risco ( Quadro 1 ) para a execução do TE/TCPE em população pediátrica e exigem a realização do exame em ambiente hospitalar (com pediatra emergencista de retaguarda) e adoção de cuidados especiais. Esses cuidados incluem: adequação de protocolos e carga de esforço a ser atingida; monitorização da saturação de oxigênio (oximetria); presença de pessoal e equipamento para possível reprogramação de marca-passo (MP)/cardioversor-desfibrilador implantável (CDI); etc. 6 – 11

Quadro 1. Contraindicações relativas e precauções na realização do TE e TCPE em crianças e adolescentes 1 , 6 – 11 .

| Ambiente hospitalar + cuidados especiais |

|---|

| Estenoses valvares graves em assintomáticos * |

| Insuficiências valvares graves em assintomáticos * |

| Cardiopatias congênitas complexas (cianóticas ou acianóticas) |

| Hipertensão pulmonar moderada/grave |

| Síndromes arrítmicas genéticas (QT longo, taquicardia catecolaminérgica e síndrome de Brudaga) documentadas |

| Suspeita de arritmias complexas (taquiarritmias e bradiarritmias) |

| Síncope por provável etiologia arritmogênica ou suspeita de bloqueio atrioventricular de alto grau esforço-induzido |

| Cardiomiopatia arritmogênica de ventrículo direito ** 258 , 259 |

| Marca-passo e CDI |

| Cardiomiopatia dilatada/restritiva com IC ou arritmia, quando estáveis clinicamente |

| Cardiomiopatia hipertrófica obstrutiva assintomática, com gradiente de repouso grave * |

| Obstrução grave da via de saída do ventrículo direito ou ventrículo esquerdo, quando assintomáticas * |

| Insuficiência cardíaca congestiva estável (Classe II ou III da NYHA) |

| TCPE na seleção de candidatos ao transplante cardíaco |

| Insuficiência renal dialítica |

| Suspeita de obstrução grave das vias aéreas * |

| SpO2 >85% em repouso, em ar ambiente, em uso de oxigênio suplementar * |

NYHA: New York Heart Association; CDI: cardioversor-desfibrilador implantável; IC: insuficiência cardíaca; TCPE: teste cardiopulmonar de exercício; SpO2: saturação arterial de oxigênio.

Situação onde o risco/benefício do exame deverá ser criteriosamente avaliada.

Na suspeita e/ou para confirmação diagnóstica e investigação do desaparecimento da arritmia ventricular.

2.5.2. Contraindicações Absolutas do TE e TCPE em Crianças e Adolescentes

As situações apresentadas no Quadro 2 são consideradas contraindicações absolutas, não devendo ser realizado o TE/TCPE em crianças e adolescentes. 7 , 9 , 11 , 105 , 181 , 188 , 260

Quadro 2. Contraindicações absolutas do TE e TCPE em crianças e adolescentes 1 , 7 , 9 , 11 , 105 , 181 , 188 , 260 .

| Contraindicações absolutas |

|---|

| Enfermidade aguda, febril ou grave |

| Deficiência mental ou física com incapacidade de se exercitar adequadamente |

| Intoxicação medicamentosa |

| Deslocamento recente de retina, em fase de recuperação |

| Distúrbios hidroeletrolíticos e metabólicos não corrigidos |

| Hipertireoidismo descontrolado |

| Diabetes mellitus descompensada |

| Estenoses valvares graves sintomáticas |

| Insuficiências valvares graves sintomáticas |

| Cardiopatia congênita descompensada |

| Insuficiência cardíaca descompensada |

| Infarto do miocárdio recente |

| Embolia pulmonar aguda ou infarto pulmonar * |

| Febre reumática ativa, com ou sem cardite |

| Miocardite, pericardite ou endocardite agudas |

| Doença de Kawasaki na fase aguda |

| Arritmia cardíaca não controlada |

| Síndrome de Marfan com suspeita de dissecção aórtica |

| Aneurisma de aorta ou em outras artérias com indicação de intervenção |

| Hipertensão arterial sistêmica grave não controlada |

| Cardiomiopatia hipertrófica com história de síncope e/ou arritmia complexa |

| Estágio final de fibrose cística |

| Marca-passo unicameral, ventricular, sem resposta de frequência (VVI) |

| SpO2 ≤85% em repouso, em ar ambiente, com ou sem uso de oxigênio suplementar |

SpO2: saturação arterial de oxigênio.

Recente ou na fase crônica com grande repercussão clínica/hemodinâmica.

3. Aspectos Legais da Prática do TE e TCPE em Crianças e Adolescentes

Além dos aspectos legais e éticos do TE e TCPE já apresentados na Diretriz Brasileira de Ergometria para população adulta, devem ser considerados os aspectos específicos para a população pediátrica descritos a seguir. 1

3.1. Aspectos Legais da Prática do TE e TCPE

O TE e o TCPE são métodos não invasivos, com baixo risco de complicações em populações não selecionadas, fácil acessibilidade e reprodutibilidade. Por se tratarem de ato médico, são regidos pelo Código de Ética Médica e, assim, o médico deve conhecer as possíveis implicações éticas e jurídicas devidamente abordadas no próprio Código de Ética Médica do Conselho Federal de Medicina (CFM), Código Civil Brasileiro, Código de Proteção ao Consumidor e demais leis vigentes ( Anexo 1 ). 261 – 264

3.2. Condições Imprescindíveis à Realização do TE e TCPE em Crianças e Adolescentes

Baseado no exposto, são necessárias adoções de condições imprescindíveis às crianças e aos adolescentes:

O TE e o TCPE são atos médicos, de exclusiva competência do médico habilitado, inscrito no Conselho Regional de Medicina e apto ao exercício profissional. O Departamento de Ergometria, Exercício, Cardiologia Nuclear e Reabilitação Cardiovascular da Sociedade Brasileira de Cardiologia (DERC/SBC) recomenda que o médico possua Título de Especialista em Cardiologia e Título de Atuação em Ergometria da Associação Médica Brasileira (AMB) devidamente registrados no CFM e tenha realizado treinamento em TE/TCPE em população pediátrica.

Em se tratando de exame com potencial risco de complicações (que embora raras, inclui morte), quando realizado em menores de idade ou legalmente incapazes, recomenda-se que um dos pais ou seu representante legal permaneça na sala de exame. O médico executante deve reconhecer o adolescente, entre 12 e 18 anos de idade, como indivíduo possivelmente capaz e atendê-lo de forma diferenciada, respeitando sua individualidade, mantendo uma postura centrada na orientação e participação do adolescente.

É obrigatória a obtenção prévia de termo de consentimento livre e esclarecido (TCLE) assinado por um dos pais ou responsável legal. No exame em adolescente, recomenda-se que o mesmo seja incluído no processo de decisão, de forma a obter sua concordância na realização do exame dando seu assentimento livre e esclarecido (ALE). Caso haja recusa na assinatura do TCLE e/ou do ALE, o médico executante não poderá realizar o exame. Quando se tratar de pesquisa científica, tanto o TCLE quanto o ALE são obrigatórios. O termo assentimento é empregado para diferenciá-lo do consentimento, que é fornecido por pessoas adultas e totalmente capazes para tomar decisões.

O local destinado à realização dos exames deve dispor dos equipamentos adaptados à população pediátrica, bem como de equipamentos/medicamentos essenciais para o atendimento de emergências nessa população, conforme recomenda esta diretriz. 265 – 268

O médico executante deverá seguir expressamente as recomendações das autoridades públicas e sanitárias e das entidades médicas referentes às possíveis endemias, epidemias e pandemias, assim como as normas dos núcleos de segurança do paciente. 269 – 271

Todos os procedimentos pertinentes ao TE e TCPE descritos nesta diretriz devem ser observados e cumpridos.

O TE e o TCPE somente devem ser realizados com a solicitação formal médica.

Avaliar a presença de contraindicações relativas e absolutas para a realização do exame.

Na eventualidade de eventos adversos de natureza grave decorrentes do exame, o médico executante assumirá o suporte ao paciente até contato efetivo com o médico assistente e/ou eventual encaminhamento ao serviço de emergência. Sugere-se, em casos de evento fatal, a comunicação e solicitação de parecer da comissão de ética e do Conselho Regional de Medicina.

Orientar os pais/responsável legal a retornar ao médico solicitante para as devidas condutas. Caso seja arguido pelo paciente, pais ou seu representante legal sobre o resultado do exame, o médico executante deverá prestar as informações pertinentes.

A remuneração pelo exame realizado deve contemplar honorários médicos justos e todos os custos operacionais.

A realização de TE e/ou TCPE envolve a obtenção e o tratamento de dados sensíveis dos pacientes, devendo os serviços de ergometria respeitarem a Lei Geral de Proteção de Dados (LGPD) e legislações do CFM. 272 – 274

3.3. Termo de Consentimento e de Assentimento para o TE e TCPE em Crianças e Adolescentes

O modelo e o processo de obtenção de TCLE para a realização de TE e TCPE devem observar os critérios norteadores do Código de Ética Médica e Recomendação do CFM N° 1/2016, assinado por um dos pais ou pelo representante legal. 275 No caso de adolescentes, é também recomendada a obtenção do ALE.

4. Condições Imprescindíveis à Capacitação em TE/TCPE em População Pediátrica

O TE/TCPE na população pediátrica é diferente dos exames realizados em adultos devido à prevalência específica de DCV (incluindo cardiopatias congênitas), às adequações de protocolos e parâmetros necessários aos exames, bem como às particularidades envolvidas na interpretação, no diagnóstico e definição de prognóstico.

Recomenda-se que os cardiologistas passem por capacitação/treinamento específico em TE/TCPE em população pediátrica: 276 , 277

O treinamento poderá ocorrer durante (simultâneo) ou após a formação na área de atuação em ergometria (consultar a Parte 1, Sessão 4 da Diretriz Brasileira de Ergometria em População Adulta), de maneira adicional e complementar, incorporando as cargas horárias e os requisitos abaixo descritos. Esse treinamento não substitui a formação na área de atuação em ergometria, não confere titulação adicional e não cria nova área de atuação. 1

O treinamento deverá ocorrer em instituição com serviço de ergometria atuante na população pediátrica, legalmente constituído, com inscrição nos órgãos públicos, documentação sanitária e registros regulares e atualizados. Essa instituição poderá ser submetida a processo de cadastramento, avaliação e credenciamento por parte do DERC/SBC.

Como pré-requisito obrigatório ao treinamento, o candidato deverá ter concluído Residência Médica em Cardiologia ou ser detentor do Título de Especialista em Cardiologia da AMB/CFM e estar em formação ou possuir o Título na Área de Atuação em Ergometria da AMB/CFM.

O treinamento deverá permitir que o cardiologista adquira experiência no TE e TCPE em população pediátrica (crianças e adolescentes), de modo a ser responsável pela organização de serviços, realização e interpretação desses exames. O programa deverá ser teórico-prático, com carga horária mínima de 100 horas.

-

O programa teórico poderá ser feito na própria instituição ou em parceria com o DERC/SBC, devendo incluir no mínimo todos os tópicos e assuntos abordados nesta diretriz. Recomenda-se conteúdo programático teórico adicional:

-

–

Revisão das DCV em crianças e adolescentes (incluindo cardiopatias congênitas), seus tratamentos e exames complementares.

-

–

Revisão das medicações utilizadas em população pediátrica e ajustes posológicos.

-

–

Fisiologia cardiovascular e fisiologia do exercício em população pediátrica saudável e com doenças cardíacas (incluindo cardiopatias congênitas não reparadas, tratadas ou sob tratamento paliativo).

-

–

O treinamento prático deverá corresponder a pelo menos 80% do período total do treinamento, devendo contemplar TE e TCPE. Deve ocorrer sob supervisão direta e presencial de preceptor que possua Título de Especialista em Cardiologia, Título da Área de Atuação em Ergometria e experiência na realização dos exames em população pediátrica. O treinamento prático deve ter uma proporção de um preceptor para no máximo dois alunos.

É recomendado o treinamento regular em atendimento de urgências correspondendo aos cursos de Pediatric Advanced Life Support (PALS) e de Advanced Cardiovascular Life Support (ACLS).

A instituição deverá se responsabilizar pela elaboração e submissão da avaliação dos alunos, durante e/ou ao final do programa do treinamento. Recomenda-se transparência nas avaliações, definindo previamente os critérios objetivos que serão exigidos. Caso não haja aprovação, sugere-se que a instituição forneça opções de treinamento adicional para sanar pendências, seguido de nova avaliação. A instituição deverá fornecer certificado oficial ao aluno aprovado e declaração de cumprimento de todos os itens correspondentes ao treinamento teórico-prático.

É imprescindível que, após o término da formação, haja participação periódica em eventos científicos/programas de atualização em TE e TCPE em crianças e adolescente, em âmbito nacional e/ou internacional, para aperfeiçoamento constante dos conhecimentos adquiridos.

Parte 2 – Teste Ergométrico

1. Metodologia do TE em Crianças e Adolescentes

1.1. Condições Básicas para a Programação do TE/TCPE

1.1.1. Equipe

O TE/TCPE deve ser realizado por médico habilitado, com experiência no método em crianças e adolescentes e com treinamento em PALS.

Profissionais da área de saúde (auxiliar de enfermagem ou técnica de enfermagem ou enfermeira) que estejam auxiliando o médico executante deverão estar treinados no cuidado de crianças e adolescentes, bem como no auxílio ao atendimento de eventuais emergências nessa população. 265 – 268

Nos casos de TE/TCPE em pacientes com cardiopatias congênitas complexas ou de risco aumentado de complicações (vide Quadro 1 ), recomenda-se a realização do exame em ambiente hospitalar com pediatra emergencista de retaguarda.

A instituição e/ou o médico executante deverão orientar e treinar adequadamente outros possíveis profissionais envolvidos no TE/TCPE na marcação/orientação do exame, higienização de equipamentos, limpeza da área física e cuidado/transporte de pacientes.

1.1.2. Área Física

Ambiente planejado, adequadamente iluminado e ventilado, com dimensões suficientes para a acomodação de todos equipamentos do TE/TCPE (incluindo maca, cadeiras para paciente e acompanhante e carro de emergência) e a aparelhagem adicional necessária aos exames em crianças e adolescentes. Deve permitir circulação de pelo menos quatro pessoas (no mínimo de 10 m 2 ), com temperatura ambiente entre 18 e 22 oC, sendo desejável umidade relativa do ar em pelo menos 40%. É necessária a presença de um dos pais ou responsável legal na sala de exame. 264 , 278 – 284

1.1.3. Equipamentos

Equipamentos básicos recomendados: ergômetro; sistema de ergometria com monitor para observação do eletrocardiograma (ECG); impressora (ou acesso para servidor de impressão); esfigmomanômetro calibrado e estetoscópio; termômetro de parede e higrômetro; oxímetro digital; cadeiras destinadas ao paciente, acompanhante e médico; maca ou cama; carro de emergência (se sala única); cilindro de oxigênio (junto ao carro de emergência) ou ponto de oxigênio em cada sala de TE/TCPE; aspirador portátil (junto ao carro de emergência) ou ponto de aspiração em cala sala; lixeiras (lixo comum e hospitalar). 149 , 264 , 278 – 280 , 285 , 286

Os equipamentos devem ser customizados para a população pediátrica:

-

Os ergômetros devem ser adaptados à idade, estatura e peso da criança/adolescente:

-

–

Esteira ergométrica com barras laterais de segurança e barra frontal com altura ajustável para permitir o apoio das mãos de crianças de menor estatura. Deve permitir velocidade inicial menor para que as crianças mais novas se adaptem à caminhada.

-

–

Colocar tapete acolchoado no chão, logo após o final da esteira, para proteção da criança.

-

–

A bicicleta ergométrica deve permitir ajustes na altura do banco, na altura e posição do guidão, no tamanho da alça do pedal e menor frenagem para adaptação ao ato de pedalar em crianças mais novas.

-

–

Sugere-se a utilização de arnês de segurança em crianças mais novas, constituído por conjunto de tiras ligadas entre si, envolvendo o tronco e a cintura, fixadas na esteira ou suporte próprio.

-

–

No TCPE, utilizar máscara facial ou sistema bucal para população pediátrica, que permita os necessários ajustes.

Eletrodo de monitorização cardíaca infantil/pediátrico (em crianças mais novas). Em adolescentes com maior estatura e circunferência torácica, poderá ser utilizado eletrodo de monitorização cardíaca para adultos.

Conjunto de manguitos de vários tamanhos para aferição da PA em população pediátrica. 287

Sistema de ergometria que adote os critérios e parâmetros para a população pediátrica e que permita ampliação do ECG para adequada visualização do sinal.

Em caso de realização de oximetria não invasiva simultaneamente/adicionalmente ao TE/TCPE, utilizar sensores de modelo pediátrico.

1.1.4. Material e Medicamentos para Emergência Médica

O serviço deverá manter disponível um carro de emergência pediátrica, com material e medicação para suporte básico e avançado de vida, no local de realização do TE e/ou TCPE, conforme padronização do carro de emergência da Diretriz de Ressuscitação Cardiopulmonar e Cuidados Cardiovasculares de Emergência da Sociedade Brasileira de Cardiologia (Quadro 17.3 – Padronização do carro de emergência pediátrica na unidade de internação, terapia intensiva e pronto-socorro). 266

1.1.5. Orientações ao Paciente e Pais/Responsáveis na Marcação do TE/TCPE

É necessário fornecer à família e ao paciente orientações no momento da marcação (idealmente por escrito) sobre o preparo pré-teste que permitirá a execução adequada do exame. Quando o exame for de crianças muito novas, sugere-se orientar os pais a explicarem as recomendações de modo a obter uma maior cooperação.

O paciente deverá vir descansado para o exame (evitar realizar esforços físicos no dia do exame).

Evitar jejum ou alimentação excessiva antes do exame; fazer uma refeição leve 2 horas antes. Não consumir bebidas com cafeína (incluindo refrigerante) no dia do exame.

O paciente deverá comparecer com roupas confortáveis para a prática de exercícios físicos: shorts (ou bermuda), camiseta e calçado esportivo (de preferência tênis; evitar sapatos abertos ou sandálias). Recomenda-se que adolescente do sexo feminino utilize sutiã ou top .

Trazer o pedido médico do exame.

Sugere-se trazer TE/TCPE realizado anteriormente.

A suspensão ou manutenção de uso de medicações ficará a critério do médico assistente do paciente.

Um dos pais ou representante legal deverá acompanhar a criança/adolescente na realização do exame.

No caso de TCPE, orientar o paciente que será necessário o uso de máscara facial durante o exame, o que não interfere na respiração.

Observação: no caso de adolescentes, verificar se fazem uso de bebida alcoólica e/ou tabagismo (mesmo que esses sejam proibidos por lei) e, quando for o caso, orientar a interrupção para a realização do exame.

1.1.6. Orientações ao Paciente e Pais/Responsáveis no Momento da Realização do Exame

Quando a criança/adolescente e seus pais (ou representante legal) chegarem para a realização do exame, todo o procedimento deve ser explicado em linguagem e termos de modo que ambos possam entender. A criança e os pais devem ter a oportunidade de realizar todas as perguntas que desejarem visando esclarecer qualquer possível dúvida sobre o exame. 11

A equipe deve demonstrar à criança/adolescente o modo de utilização do ergômetro e deixar claro que o exame normalmente não provoca dor e pode ser até divertido. Orientar os pais de que a criança/adolescente:

-

–

Realizará um esforço físico (andar na esteira ou pedalar), dentro das suas habilidades e capacidade, podendo interromper o esforço a qualquer momento que ela desejar ou precisar.

-

–

O médico e a equipe realizarão vários procedimentos necessários à monitorização e registro dos dados do exame.

-

–

Com o esforço, poderão ocorrer sintomas como cansaço e outros associados às doenças da criança/adolescente.

1.1.7. Orientações quanto ao Uso de Medicações

Diferentemente do que ocorre em adultos, são raras as indicações de suspensão de medicações para a realização do TE/TCPE em crianças e adolescentes. Geralmente, a população pediátrica só faz uso de medicamentos de comprovada necessidade para o controle e estabilidade clínica de suas doenças. Quando necessária, a suspensão deve ser indicada pelo médico assistente da criança/adolescente, levando em consideração os riscos envolvidos. Para determinação do período de suspensão considerar o tempo de eliminação de cada medicamento e suas variações na faixa etária pediátrica. 6 – 12

Nos pacientes com asma, a manutenção do uso de medicamentos deve considerar a indicação do exame. 288 Na suspensão de outras medicações considerar possíveis interferências no desempenho físico, na resposta cronotrópica, no limiar de isquemia e angina, na resposta do segmento ST, nas arritmias esforço-induzidas etc.

1.2. Procedimentos Básicos para a Realização do Exame

O TE/TCPE em crianças é mais desafiador do que em adolescentes, especialmente naquelas com comprometimento crônico da saúde. As dificuldades em testá-las surgem por três razões: 289

Tamanho corporal muito pequeno mesmo quando o equipamento é adaptado à população pediátrica.

Capacidade física muito baixa, dificultando a adaptação, mesmo com a utilização de protocolos com pequenos incrementos da carga de esforço.

Geralmente apresentam um menor período de atenção, menor motivação durante exames longos e baixa colaboração, tornando difícil diferenciar a limitação ao esforço de falta de cooperação.

1.2.1. Fase Pré-teste, Avaliação Inicial, Exame Físico Sumário e Específico

Recomenda-se ao médico executante avaliar a indicação do exame e os sintomas atuais do paciente, constatar se as orientações pré-teste foram cumpridas, realizar anamnese e exame físico dirigidos aos sistemas cardiovascular e pulmonar ( Quadro 3 ). 264 , 279 , 280

Quadro 3. Recomendações quanto à anamnese e exame físico dirigido em paciente pediátrico 1 , 264 , 279 , 280 .

| Anamnese | Exame Físico |

|---|---|

| Sintomas atuais * | Ectoscopia geral (anemia, faces sindrômicas, palidez cutânea, cianose) |

| Antecedentes patológicos/cirúrgicos ** | FC/PA *3 |

| História familiar de morte súbita ou doença arterial coronariana precoce ** | Ausculta cardíaca e pulmonar |

| Fatores de risco (vide Parte 2, Sessão 2 – Estratificação de Risco Pré-TE) ** | Oximetria não invasiva *4 |

| Medicações em uso ** | Pulsos periféricos e índice tornozelo-braquial *5 |

| Tolerância ao esforço físico * | |

| Realizou TE/TCPE anteriormente? Teve alguma anormalidade? ** |

TE: teste ergométrico; TCPE: teste cardiopulmonar de esforço; FC: frequência cardíaca; PA: pressão arterial.

Verificados tanto com a criança/adolescentes quanto com seus pais/representante legal.

Verificados principalmente através de informações dos pais/representante legal.

Utilizar manguito adequado a circunferência do membro superior.

Exame adicional. Indicado principalmente nos casos de cardiopatia congênita cianótica, insuficiência cardíaca, valvopatas, pós-COVID.

Exame adicional. Indicado na investigação de coarctação de aorta, síndrome de Takotsubo e claudicação de membros inferiores.

É imprescindível verificar a possibilidade de eventuais contraindicações relativas e absolutas para a realização do TE/TCPE, bem como informações sobre tratamentos realizados anteriormente (especialmente nos casos de CC). Não é recomendado o uso de escore clínico pré-teste de adultos (não são validados para a população pediátrica).

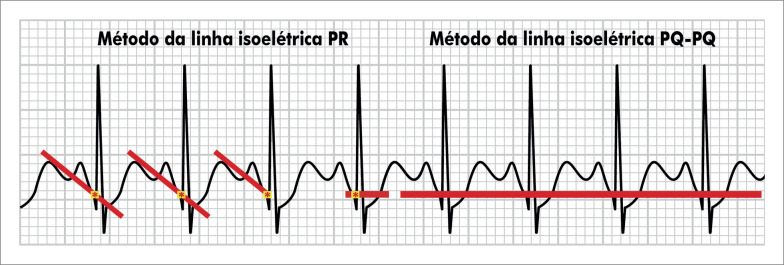

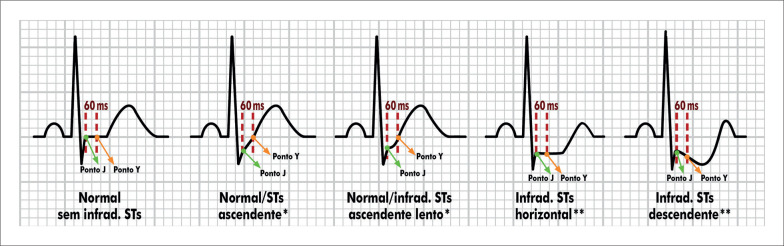

1.2.2. Sistema de Monitoração e Registro Eletrocardiográfico

A monitorização contínua do ECG e a realização de registros são obrigatórios em todas as etapas do exame (repouso, esforço e recuperação). Recomenda-se a utilização de sistema computadorizado de ergometria para a monitorização do ECG e de software que permita a obtenção, registro e interpretação de dados em população pediátrica. Sugere-se utilizar eletrodo para monitorização de ECG de longa duração, hipoalergênico, extra-aderente e em crianças pequenas utilizar o eletrodo infantil/pediátrico. 264 , 279 , 280

Recomenda-se seguir as orientações da Diretriz Brasileira de Ergometria para a População Adulta quanto ao número de derivações a serem utilizadas (12 ou 13) e ao posicionamento dos eletrodos. Nos sistemas de 12 derivações utilizar o posicionamento clássico de Mason-Likar ou sua versão modificada preservando CM5. Nos sistemas de 13 derivações utilizar o posicionamento das derivações clássicas com adição de CM5. Não é mais recomendado o uso de sistemas de três derivações, tendo em vista a superioridade dos sistemas com 12, 13 ou mais derivações. 1

Os procedimentos de preparo da pele são similares aos dos adultos, inclusive quanto à eventual necessidade de retirada de excesso de pelos nos adolescentes do sexo masculino nas regiões de fixação dos eletrodos. Em crianças pequenas, no momento da limpeza da pele com álcool, devido à maior sensibilidade, deve-se ter o cuidado de evitar o excesso de abrasão da pele e, também, assegurar que o procedimento não indica recebimento de uma injeção (muitas crianças associam compressas com álcool a injeções). Pode-se utilizar um colete ou uma camisa de rede para ajudar a manter os eletrodos e fios firmemente no lugar.

1.2.3. Ergômetros

A escolha do ergômetro deve ser individualizada levando-se em conta a idade da criança e adolescente, estatura, capacidade de adaptação, segurança e eventuais limitações físicas. São três os principais tipos de ergômetros utilizados no TE/TCPE: bicicleta ergométrica, esteira ergométrica e cicloergômetro de braço. Tanto a bicicleta ergométrica quanto a esteira produzem cargas máximas adequadas, confiáveis e reprodutíveis, permitindo a coleta de informações diagnósticas e de desempenho físico. 290

1.2.3.1. Bicicleta Ergométrica

A utilização de bicicleta ergométrica (cicloergômetro de membros inferiores) é mais frequente em crianças a partir dos 6 anos de idade. Crianças que não estão acostumadas ao ciclismo geralmente apresentam:

-

–

Fadiga muscular precoce nos membros inferiores, podendo não atingir o esforço máximo.

-

–

Dificuldade em manter a cadência do pedalar entre 40 e 70 rotações por minuto (rpm).

-

–

Dificuldade em manter os pés nos pedais, mesmo quando ajustados para o tamanho da criança.

Para acomodar adequadamente as crianças e adolescentes na bicicleta ergométrica, deve-se ajustar a altura do assento, a altura e a posição do guidão e o tamanho da alça do pedal. Crianças e adolescentes com estatura ≥125 cm poderão realizar o TE/TCPE em bicicleta ergométrica padrão para adultos. 200 A utilização de bicicleta ergométrica é preferida quando for necessária uma avaliação mais precisa da PA.

1.2.3.2. Esteira Ergométrica

O TE/TCPE em esteira ergométrica é possível em crianças a partir dos 3 anos de idade, pois as mesmas estão mais familiarizadas com o andar rápido ou até mesmo correr. Entretanto, o esforço na esteira não é uma forma natural de caminhar, sendo recomendável previamente avaliar a capacidade de adaptação e a coordenação ao ergômetro. Recomenda-se ajustar a altura da barra frontal de apoio conforme a estatura da criança.

Em TE de crianças muito pequenas ou limitadas sugere-se: 6 – 12

-

–

Utilização de arnês de segurança de modo a proteger a criança em caso de mal súbito ou desequilíbrio.

-

–

Utilização de grades laterais e tapete acolchoado colocado no chão ao final da esteira para proteção da criança.

-

–

Permanência de um membro extra da equipe executora, posicionado imediatamente atrás da esteira, para auxílio e proteção da criança durante o esforço.

O TE em esteira geralmente apresenta consumo máximo de oxigênio (VO2max) ≈10% superior ao obtido na bicicleta ergométrica. 291 – 293

1.2.3.3. Cicloergômetro de Braço

Em nosso meio, o cicloergômetro de braço é raramente utilizado em crianças e adolescentes. Geralmente, é empregado em pacientes com deficiência de mobilidade nos membros inferiores causada por lesão medular (torácica ou lombar superior), amputação de membro inferior, meningocele, espinha bífida etc. 294 , 295

O TE com cicloergômetro de braço, usando um protocolo de rampa validado, permite avaliar adequadamente a aptidão cardiorrespiratória de crianças e adolescentes. 295 , 296

1.2.4. Escolha do Protocolo

A escolha do protocolo deve ser individualizada considerando a finalidade do exame, a prática de atividades físicas diárias, eventuais limitações físicas e visando tempo de esforço de ≈10 minutos (entre 6 e 12 minutos). O protocolo também deverá respeitar as características do paciente: idade, tamanho corporal, capacidade de adaptação ao incremento de carga de esforço etc. 6

Os protocolos são divididos quanto à forma do esforço:

-

Incrementais (aumento gradativo de carga):

-

–

Escalonado (em degraus): com aumento de cargas em estágio (etapas) em tempo predeterminado (a cada um ou mais minutos por estágio).

-

–

Rampa: com incrementos pequenos de carga, frequentes (tendendo a linear) e em curtos intervalos de tempo (incrementos em segundos, sempre inferiores a 1 minuto).

-

–

Sem incremento (carga fixa): sem aumento de cargas. Em esteira ergométrica, mantém velocidade e inclinação fixas. 1 , 12 , 285

1.2.4.1. Protocolos para Bicicleta Ergométrica

Os principais protocolos para bicicleta ergométrica são apresentados na Tabela 13 . A carga de trabalho realizada na bicicleta normalmente é expressa em watts (W). A maioria dos protocolos requer uma cadência de pedalar entre 50 e 60 rpm, limitando a variação entre 40 e 70 rpm.

Tabela 13. Comparação dos principais protocolos para bicicleta ergométrica.

| Protocolo | Indicado para | Carga inicial | Incremento de carga |

|---|---|---|---|

| Balke | Crianças e adolescentes saudáveis | 25 W | 25 W a cada 2 minutos |

| Astrand 299 | Crianças e adolescentes | 25 W | 25 W a cada 3 minutos |

| McMaster * 300 | Crianças ** e adolescentes *** | 12,5 W a 25 W | 5 modos de incremento, dependendo da estatura e do sexo, a cada 2 minutos |

| James * 301 , 302 | Crianças e adolescentes, ativos | 33 W | 3 modos de incremento, dependendo da área de superfície corporal, a cada 3 minutos |

| Godfrey * 303 , 304 | Crianças* e adolescentes | 10 W a 20 W | 3 modos de incremento, dependendo da estatura, a cada 1 minuto |

| Rampa 297 , 305 | Todas as populações sendo o ideal para atletas | 10 W a 20 W | 5 a 20 W a cada 1 minuto. Subdividir o aumento em valores iguais e o incremento em intervalos regulares (<60 segundos) **** |

Vide Tabela 14 para descrição detalhada dos protocolos;

Baseado na estatura, correspondendo a crianças a partir dos 6 anos de idade;

Pacientes com doenças cardíacas, pulmonares ou musculares podem exigir reduções na carga inicial de trabalho;

Exemplo: protocolo de rampa com incremento de carga de 15 W a cada 1 minuto = aumentar a carga em 5 W a cada 20 segundos.

Os protocolos de Balke e de Astrand apresentam a desvantagem de serem fixos, não considerarem o tamanho corporal, podendo ser muito intensos para crianças mais novas (principalmente as cardiopatas).

Nos protocolos de McMaster, James e Godfrey, as cargas iniciais e os incrementos são feitos de acordo com o tamanho corporal [estatura ou área de superfície corporal (ASC)] e/ou sexo ( Tabela 14 ). Em adolescentes, utilizam-se elevadas cargas de esforço, o que pode ser uma limitação para os sedentários ou doentes (cardiopatas, pneumopatas etc.). 297 , 298

Tabela 14. Descrição dos Protocolos de Godfrey, McMaster e James para bicicleta ergométrica 300 – 304 .

| Protocolo de Godfrey

Estágio: 1 min Ritmo: 60 rpm |

Protocolo de McMaster

Estágio: 2 min Ritmo: 50 rpm |

Protocolo de James

Estágio: 3 min Ritmo: 60-70 rpm |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Altura

<120 cm * |

Altura

120-150 cm * |

Altura

>150 cm * |

Altura

≤119,9 cm * |

Altura

120-139,9 cm * |

Altura

140-159,9 cm * |

Altura

≥160 cm (masc) |

Altura

≥160 cm (femin) |

ASC <1,0 * | ASC

1,0-1,2 * |

ASC >1,2 * | |

| Tempo (min) | 10 W/est | 15 W/est | 20 W/est | 12,5 W/est | 25 W/est | 50 W/est | 50 W/est | 25 W/est | 16,5 W/est | 33 W/est | 49,5 W/est |

| 0 | 10 W | 15 W | 20 W | 12,5 W | 12,5 W | 25 W | 25 W | 25 W | 33 W | 33 W | 33 W |

| 1 | 10 W | 15 W | 20 W | ||||||||

| 2 | 20 W | 30 W | 40 W | 25 W | 37,5 W | 50 W | 75 W | 50 W | |||

| 3 | 30 W | 45 W | 60 W | 49,5 W | 66 W | 82,5 W | |||||

| 4 | 40 W | 60 W | 80 W | 37,5 W | 62,5 W | 75 W | 125 W | 75 W | |||

| 5 | 50 W | 75 W | 100 W | ||||||||

| 6 | 60 W | 90 W | 120 W | 50 W | 87,5 W | 100 W | 175 W | 100 W | 66 W | 99 W | 132 W |

| 7 | 70 W | 105 W | 140 W | ||||||||

| 8 | 80 W | 120 W | 160 W | 62,5 W | 112,5 W | 125 W | 225 W | 125 W | |||

| 9 | 90 W | 135 W | 180 W | 82,5 W | 132 W | 181,5 W | |||||

| 10 | 100 W | 150 W | 200 W | 75 W | 137,5 W | 150 W | 275 W | 150 W | |||

| 11 | 110 W | 165 W | 220 W | ||||||||

| 12 | 120 W | 180 W | 240 W | 87,5 W | 162,5 W | 175 W | 325 W | 175 W | 99 W | 165 W | 231 W |

| 13 | 130 W | 195 W | 260 W | ||||||||

| 14 | 140 W | 210 W | 280 W | 100 W | 187,5 W | 200 W | 375 W | 200 W | |||

| 15 | 150 W | 225 W | 300 W | 115,5 W | 198 W | 280,5 W | |||||

| 16 | 160 W | 240 W | 320 W | 112,5 W | 212,5 W | 225 W | 425 W | 225 W | |||

| 17 | 170 W | 255 W | 340 W | ||||||||

| 18 | 180 W | 270 W | 360 W | 125 W | 237,5 W | 250 W | 475 W | 250 W | 132 W | 231 W | 330 W |

| 19 | 190 W | 285 W | 380 W | ||||||||

| 20 | 200 W | 300 W | 400 W | 137,5 W | 262,5 W | 275 W | 525 W | 275 W | |||

ASC: área de superfície corporal – metros quadrados (m2); W: Watts; min: minuto; rpm: rotações por minuto; est: estágio; cm: centímetro; masc: masculino; femin: feminino.

Para ambos os sexos.

1.2.4.2. Protocolos para Esteira Rolante

1.2.4.2.1. Protocolos Escalonados

1.2.4.2.1.1. Protocolo de Bruce

É o protocolo escalonado mais utilizado ( Tabela 15 ). É mais apropriado para o TE em crianças sem cardiopatia grave e em adolescentes aparentemente saudáveis, inclusive pré-escolares. Pode ser utilizado em TE seriados para a comparação de dados à medida que a criança cresce. Desvantagens potenciais:

Tabela 15. Principais protocolos escalonados para a população pediátrica e suas características 1 , 7 , 306 .

| Estágio | Bruce | Bruce modificado | Ellestad | Balke | Naugthon | Naugthon modificado | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Min | mph/km/h | E% | Min | mph/km/h | E% | Min | mph/km/h | E% | Min | mph/km/h | E% | Min | mph/km/h | E% | Min | mph/km/h | E% | |

| 01 | 3 | 1,7/2,7 | 10 | 3 | 1,7/2,7 | 0 | 3 | 1,7/2,7 | 10 | 1 | 3,5/5,6 | 1 | 2 | 1,0/1,6 | 0 | 2 | 3,0/4,8 | 0 |

| 02 | 6 | 2,5/4,0 | 12 | 6 | 1,7/2,7 | 5 | 5 | 3,0/4,8 | 10 | 2 | 3,5/5,6 | 2 | 4 | 2,0/3,2 | 0 | 4 | 3,0/4,8 | 2,5 |

| 03 | 9 | 3,4/5,5 | 14 | 9 | 1,7/2,7 | 10 | 7 | 4,0/6,4 | 10 | 3 | 3,5/5,6 | 3 | 6 | 2,0/3,2 | 3,5 | 6 | 3,0/4,8 | 5,0 |

| 04 | 12 | 4,2/6,7 | 16 | 12 | 2,5/4,0 | 12 | 10 | 5,0/8,0 | 10 | 4 | 3,5/5,6 | 4 | 8 | 2,0/3,2 | 7,0 | 8 | 3,0/4,8 | 7,5 |

| 05 | 15 | 5,0/8,0 | 18 | 15 | 3,4/5,5 | 14 | 12 | 6,0/9,7 | 15 | 5 | 3,5/5,6 | 5 | 10 | 2,0/3,2 | 10,5 | 10 | 3,0/4,8 | 10 |

| 06 | 18 | 5,5/8,8 | 20 | 18 | 4,2/6,7 | 16 | 14 | 7,0/9,6 | 15 | 6 | 3,5/5,6 | 6 | 12 | 2,0/3,2 | 14,0 | 12 | 3,0/4,8 | 12,5 |

| 07 | 21 | 6,0/9,7 | 22 | 21 | 5,0/8,0 | 18 | 16 | 8,0/11,2 | 15 | 7 a 21 | 3,5/5,6 | +1%/min * | 14 | 2,0/3,2 | 17,5 | 14 | 3,0/4,8 | 15,0 |

| 08 | 24 | 6,5/10,5 | 24 | 24 | 5,5/8,8 | 20 | 18 | 9,0/12,8 | 15 | 22 | 3,5/5,6 | 22,0 | 16 | 2,0/3,2 | 21,0 | 16 | 3,0/4,8 | 17,5 |

Min.: minutos; mph: milhas por hora; km/h: quilômetros por hora; E%: elevação/inclinação da esteira (em %); MET: metabolic equivalent of task (equivalente metabólico da tarefa).

Aumentar 1% na inclinação a cada minuto do exame (velocidade constante).

-

–

Em crianças mais novas ou mais limitadas, os incrementos de esforço entre os estágios podem ser muito grandes, levando frequentemente à desistência no primeiro minuto de um novo estágio.

Pode ser demasiadamente longo em jovens treinados/atletas, causando, inclusive, tédio.

1.2.4.2.1.2. Protocolo de Bruce Modificado

O protocolo de Bruce modificado, sem inclinação inicial, é mais adequado para crianças menores ou mais limitadas fisicamente. É utilizado em crianças a partir de 3 anos, portadoras de cardiopatia ou pneumopatia. A maior limitação é que após o terceiro estágio ocorrem incrementos abruptos de esforço a cada estágio (semelhante ao Protocolo de Bruce).

1.2.4.2.1.3. Protocolo de Ellestad

Emprega aumentos expressivos de velocidade, sendo indicado preferencialmente para adolescentes fisicamente ativos e atletas. As principais limitações desse protocolo são: altas velocidades em cargas iniciais, dificultando a adaptação de quem não está acostumado a correr; dificuldade para realização de medições pressóricas.

1.2.4.2.1.4. Protocolo de Balke

O protocolo de Balke incorpora uma velocidade constante da esteira (3,5 mph) com inclinação crescente de 1% a cada minuto. É mais adequado para crianças obesas, crianças muito novas, cronicamente doentes e/ou muito limitadas. 7 , 306

Uma desvantagem é que, em pacientes fisicamente ativos, a duração do exame é muito longa. Para esses pacientes, é preferível a versão modificada do protocolo de Balke (" running Balke ") utilizando velocidade constante mais rápida, visando a manter o tempo de esforço entre 8 e 10 minutos.

1.2.4.2.1.5. Protocolo de Naughton

Existem várias adaptações do protocolo de Naughton para a população pediátrica, variando a velocidade inicial e inclinação, envolvendo pequenos incrementos de carga por estágio, permitindo melhor adaptação de crianças menores e/ou com limitações físicas. Não deve ser utilizado em crianças e adolescentes saudáveis por prolongar demasiadamente o exame. 307

1.2.4.2.2. Protocolo em Rampa

O protocolo em rampa pode ser totalmente individualizado às características da criança/adolescente, variando a velocidade, a inclinação (iniciais e finais) e a duração do exame. Permite a melhor determinação do consumo máximo de oxigênio (direto ou estimado), limiares ventilatórios, medição ou estimativa da potência máxima, avaliação das causas da limitação do esforço, avaliação de isquemia e arritmias. Deverá manter a meta de duração do exame entre 8 e 12 minutos com a inclinação da rampa ajustada ao tamanho e às habilidades físicas da criança.

Em crianças cardiopatas, sugere-se programar o protocolo com velocidade inicial de 1 km/hora (sem inclinação) e, posteriormente, realizar pequenos e constantes incrementos na intensidade do esforço.

A Tabela 16 apresenta a individualização do protocolo de rampa baseada em estudo na população infanto-juvenil brasileira, que se mostrou mais confortável do que o protocolo de Bruce. 121

Tabela 16. Individualização do protocolo em rampa por sexo e faixa etária, baseado em estudo na população pediátrica brasileira.

| Faixa etária (anos) | Sexo feminino | Sexo masculino | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Velocidade (km/h) | Inclinação (%) | VO2max | Velocidade (km/h) | Inclinação (%) | VO2max | |||||

| Inicial | Final | Inicial | Final | Média ± DP | Inicial | Final | Inicial | Final | Média ± DP | |

| 4-7 | 3,0 | 6,5 | 4,0 | 14,0 | 39,4±4,7 | 3,5 | 7,5 | 5,0 | 15,0 | 45,3±9,2 |

| 8-11 | 3,5 | 7,0 | 5,0 | 15,0 | 43,9±6,2 | 4,0 | 8,0 | 5,0 | 15,0 | 48,6±7,9 |

| 12-14 | 4,0 | 8,0 | 5,0 | 15,0 | 48,3±7,3 | 4,0 | 8,5 | 6,0 | 16,0 | 53,2±9,0 |

| 15-17 | 4,0 | 8,0 | 5,0 | 15,0 | 47,8±10,1 | 4,5 | 9,0 | 6,0 | 16,0 | 55,1±9,4 |

DP: desvio padrão; km/h: quilômetros por hora; VO2max: consumo máximo de oxigênio. Duração final prevista de 10 minutos. Adaptado de: Silva et al. Teste ergométrico em crianças e adolescentes: maior tolerância ao esforço com o protocolo em rampa. 121

1.2.5. Monitorização da Frequência Cardíaca

A FC é monitorada e medida diretamente do traçado eletrocardiográfico durante todas as fases do TE/TCPE. Recomenda-se o registro da FC, pelo menos no pré-esforço, ao final de cada estágio de protocolo escalonado ou a cada 2 minutos em protocolo de rampa e na recuperação (1, 2, 4 e 6 minutos). Caso necessário, o registro deve ser mantido por tempo maior na recuperação.

Recomenda-se a realização de ECG convencional de 12 derivações de forma adicional, precedendo o TE/TCPE. O ECG convencional é um exame complementar que permite avaliar a condição cardíaca, podendo, inclusive, contribuir para a eventual contraindicação do exame. O ECG convencional de 12 derivações é um procedimento médico previsto na Classificação Brasileira Hierarquizada de Procedimentos Médicos (Código: 4.01.01.01-0). 1 , 278 , 308

No TE, conceitua-se como: 95 , 264

-

–

FC máxima (FCmax) é aquela atingida em nível de exaustão ao esforço.

-

–

FC de pico (FCpico) é a maior FC observada no pico do esforço, mesmo que não haja exaustão.

É importante ressaltar que, em crianças aparentemente saudáveis, a FCmax praticamente não muda ao longo da infância, sendo, portanto, limitado o uso das equações de regressão para estimar a FCmax na população pediátrica (predição menos precisa e dispersão média entre 5 e 10 bpm). Na adolescência, por volta dos 16 anos, a FCmax começa a declinar a uma taxa de 0,7 ou 0,8 bpm por ano de idade. 177

Sugere-se a adoção de um valor médio de FC máxima prevista para toda a faixa etária pediátrica (crianças e adolescentes) correspondendo a 197 bpm, e uma FC submáxima prevista de 180 bpm (valor correspondente a −2 desvios padrão). 309 , 310

Na eventualidade de uso de equações para estimar a FCmax na população pediátrica, considerar que: 309 , 311

-

–

Equação de Karvonen (FCmax = 220 – idade) geralmente superestima a FCmax. 312 , 313

-

–

Equação de Tanaka [FCmax = 208 – (0,7 x idade)] pode tanto subestimar quanto superestimar a FCmax, sendo considerada a equação de melhor precisão. 311 , 314 , 315

-

–

Equação de Nikolaidis [FCmax = 223 – (1,44 x idade)], que foi elaborada para atletas adolescentes, também não se mostrou adequada. 315 , 316

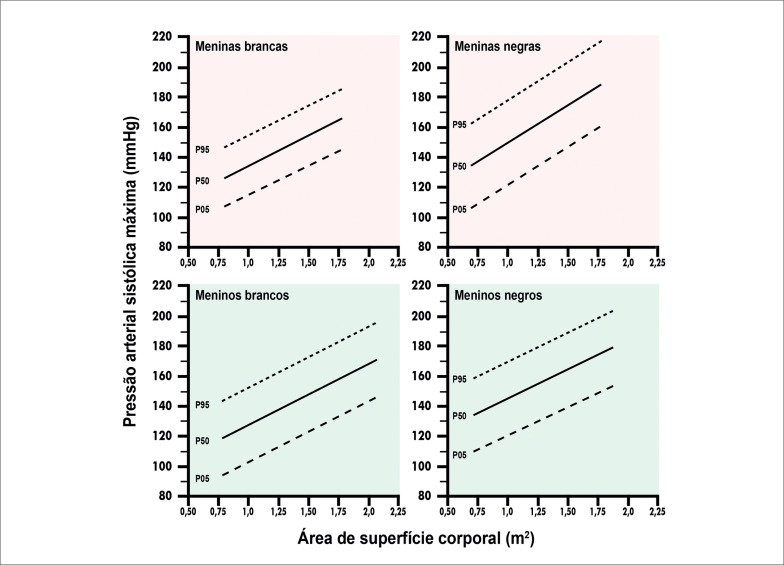

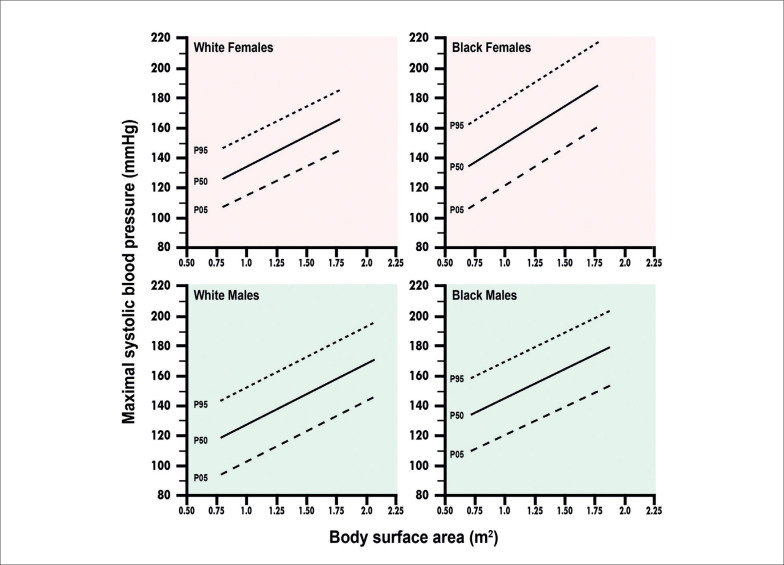

1.2.6. Monitorização da Pressão Arterial Sistêmica

A medida da PA deve ser executada em todas as fases do TE (pré-teste, esforço e recuperação) por médico devidamente treinado e com experiência em população pediátrica.

A medição manual com utilização de esfigmomanômetro aneroide é a mais utilizada. Medições com equipamentos semiautomáticos e/ou automáticos são possíveis, entretanto podem não fornecer medições precisas em determinadas circunstâncias devido a: 317 , 318

-

–

Presença de excesso de movimento e vibração que ocorre comumente em crianças mais novas.

-

–

Alguns dispositivos funcionam medindo a PA média e calculando as PA sistólica (PAS) e diastólica (PAD) por meio de algoritmos, que podem apresentar limitações na avaliação da PAD em crianças por não distinguirem as fases IV e V de Korotkoff. 319 , 320

-

–

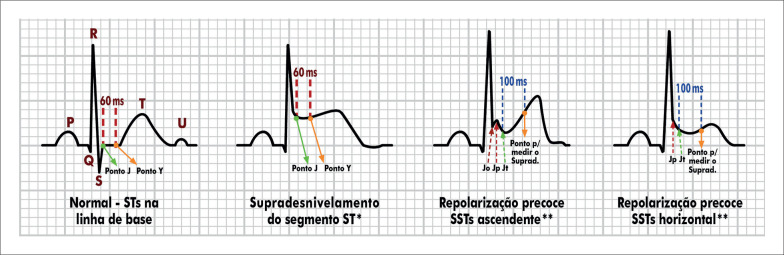

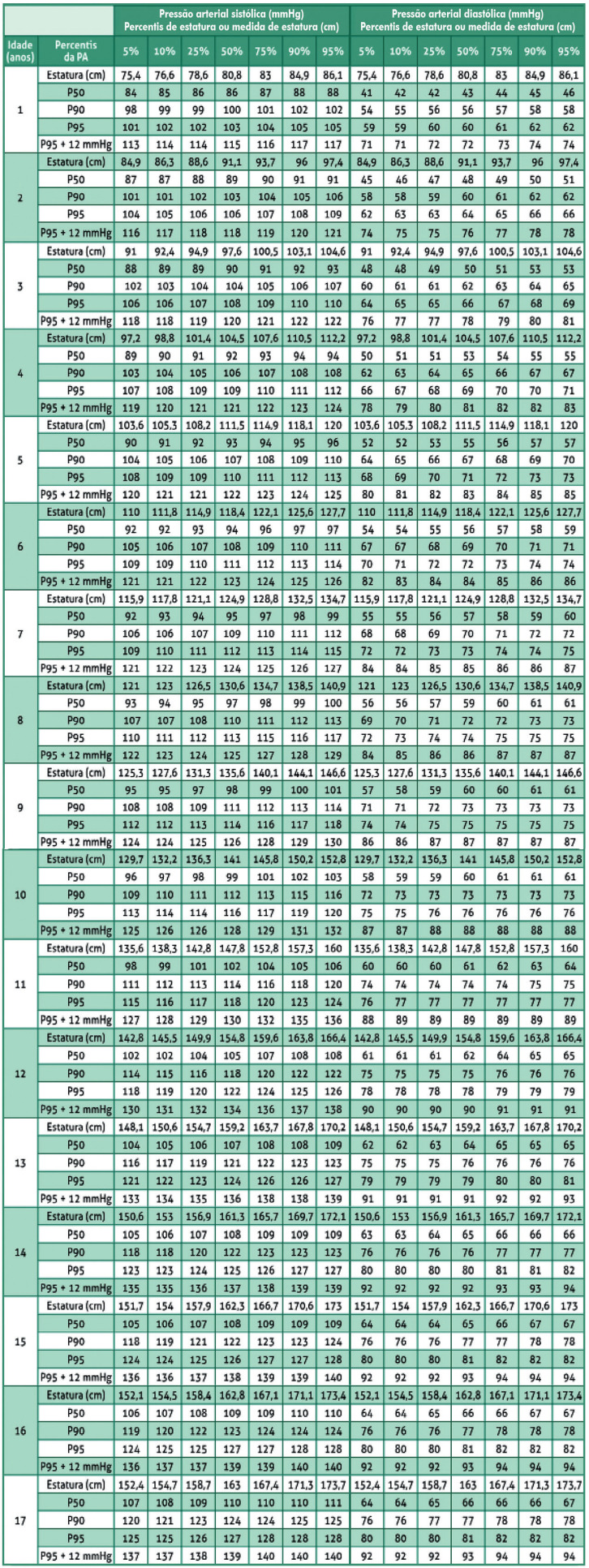

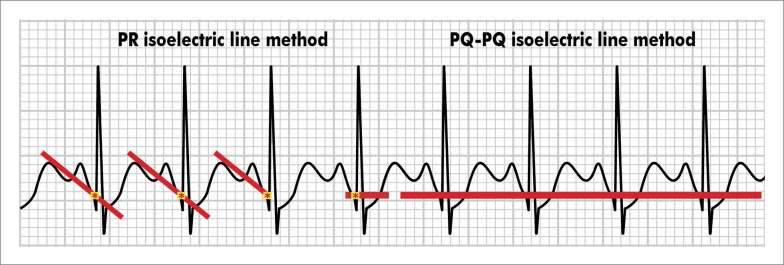

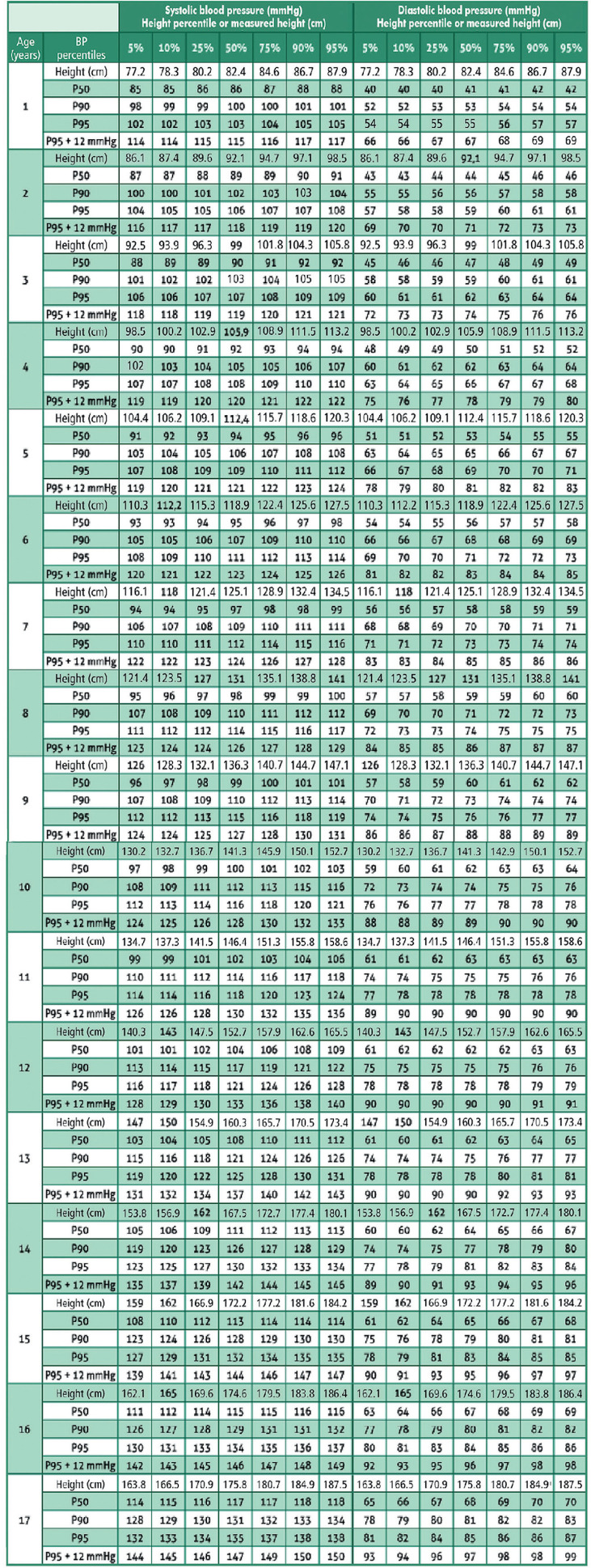

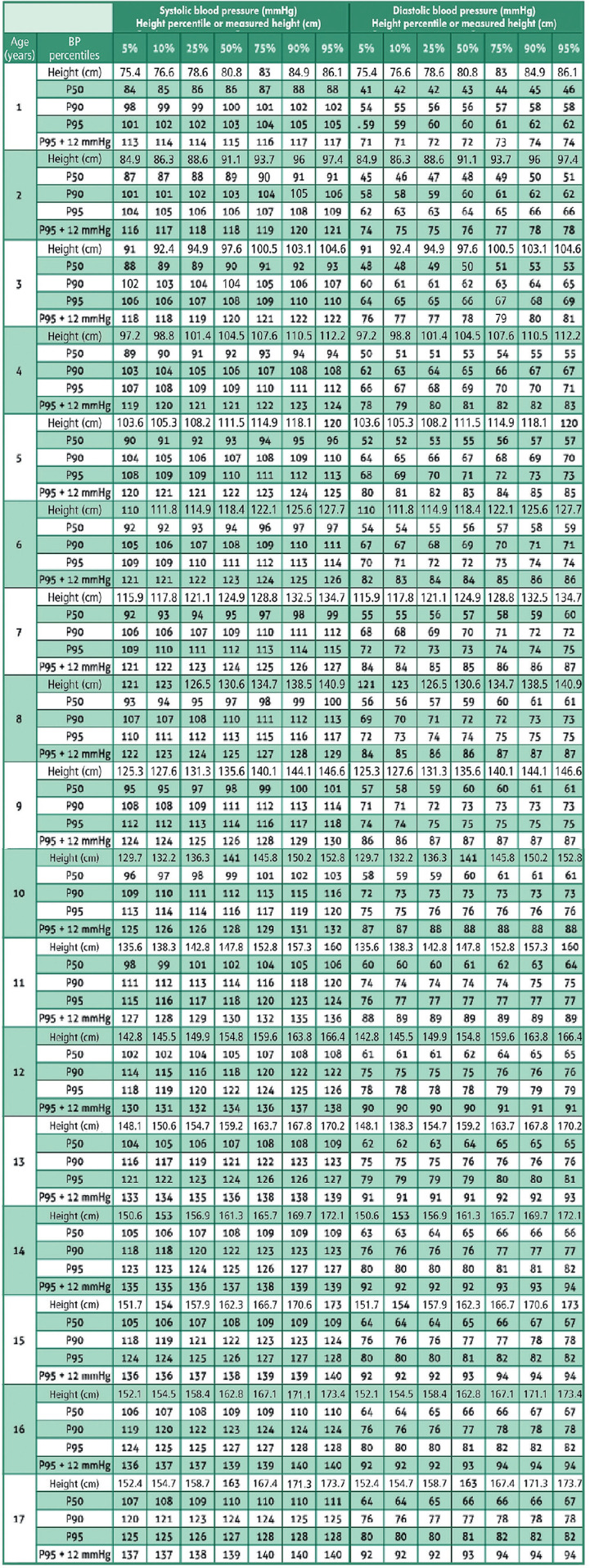

A maioria dos equipamentos automáticos não foi validada na população pediátrica para medições em repouso e esforços intensos. 4