Abstract

Alcohol consumption increases oxidative stress and imbalances in the antioxidant system, even with ethanol (EtOH) exposure at a young age. This study assessed changes in the antioxidant system following young EtOH exposure in peripheral immunity and measured sensitive indicators of heavy alcohol consumption. We used peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from 197 male university students without smoking habits to examine changes in antioxidant-related gene expression in vitro and in PBMCs. In vitro, the antioxidant system was impaired by EtOH. Next, we examined the expression of 84 antioxidant-related genes in the PBMCs of 162 young adults, among which the superoxide dismutase (SOD) 1 expression was most negatively correlated with alcohol consumption degree. The plasma SOD1 level had the highest area under the curve value (0.806) for heavy alcohol consumption. Our data demonstrated that a decreased SOD1 level is a sensitive indicator of an impaired antioxidant system and heavy alcohol consumption with early EtOH exposure.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-024-76084-8.

Keywords: SOD1, Antioxidant gene expression, Peripheral immune cells, Young adults, Early ethanol exposure, Oxidative stress

Subject terms: Predictive markers, Gene expression, Alcoholic liver disease, Toxicology, Stress signalling

Introduction

Moderate alcohol consumption relieves mental and physical stress, whereas excessive drinking exerts adverse effects on immunity and organs, such as the liver and pancreas, by increasing oxidative stress (OS) in the body1–4. Several antioxidant enzymes suppress OS, and various changes in these enzymes following alcohol intake are observed in the cells, tissues, and organs5. Peripheral immunity is also directly influenced by alcohol/ethanol (EtOH), which adversely affects the antioxidant system6; however, this has not been investigated in detail. High alcohol consumption increases the risk of health damage, and globally, light-to-moderate alcohol consumption increases the risk of developing malignant tumors7–9. Notably, “heavy-drinking” individuals, consuming more than 100 g/week, have a higher mortality rate; furthermore, some young adults have inappropriate drinking habits, including heavy drinking10,11. The antioxidant system may also be adversely influenced by light-to-heavy alcohol consumption in young adults with early alcohol-drinking habits.

Previously, we reported a noninvasive diagnostic method for nonalcoholic steatohepatitis based on gene expression profiles in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs), finding that these profiles are useful for predicting pathology12. EtOH exposure induces OS and imbalances in the antioxidant system, including downregulating the gene expression of superoxide dismutase (SOD) and glutathione peroxidase (GPx) in PBMCs6,13; however, the changes in the antioxidant system in human peripheral immunity due to EtOH exposure at a young age have not been elucidated. Accordingly, identifying sensitive indicators of “heavy drinking” at a young age to prevent the risk of lifestyle-related diseases and high mortality will be necessary in the future10,14. Hematological and biochemical parameters related to alcohol consumption, such as liver enzymes including aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT), and mean corpuscular volume (MCV), are clinically used to assess alcohol consumption and liver damage in adults15,16; however, their usefulness in young adults has not been elucidated.

In this study, we focused on young adults who were exposed to EtOH at a young age and examined the changes in antioxidant-related gene expression profiles of their PBMCs to assess the role of the antioxidant system in peripheral immunity under EtOH exposure. We examined several antioxidant-related gene expression levels in vitro and in the PBMC samples of young male adults and identified the indicators.

Results

Decreased antioxidant gene expression in PBMCs

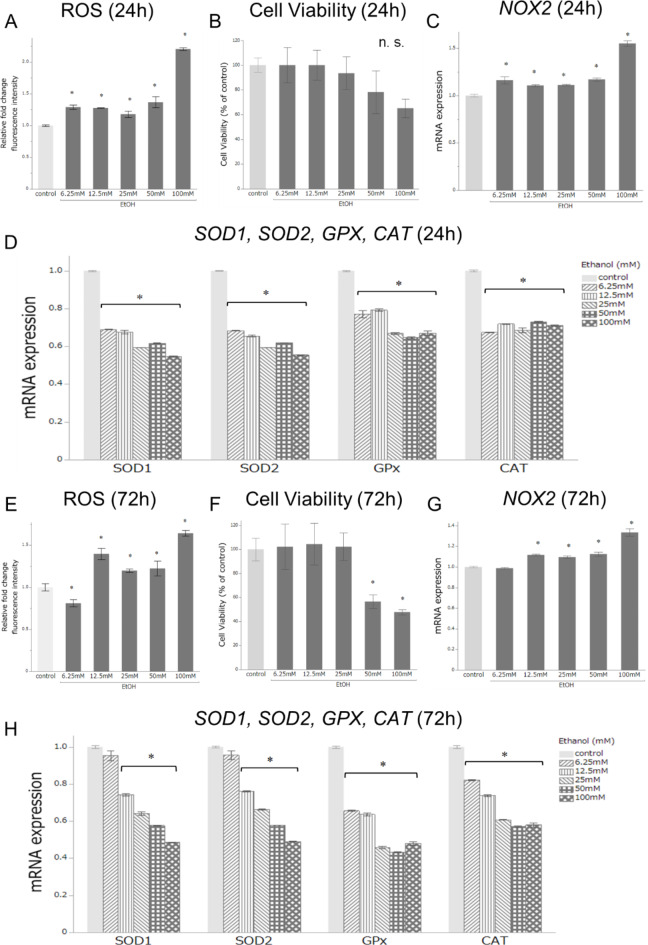

To assess OS-related changes in peripheral immunity, we first examined the in vitro intercellular ROS, cell viability, and expression levels of five OS-related genes: SOD1, SOD2, GPX1, CAT, and NOX2 in the PBMCs of healthy controls after treatment with several concentrations (0 [control], 6.2, 12.5, 25, 50, and 100 mM) of EtOH for different times (24 and 72 h exposure) (Fig. 1). The range of EtOH 6.25–100 mM corresponded to moderate-heavy drinking in young adults. Relative fold changes in intercellular ROS and NOX2 mRNA expression levels were significantly increased for all EtOH treatments compared to the control after 24 h of exposure (p < 0.05, Fig. 1A,C) and for all EtOH treatments except 6.2 mM after 72 h of exposure (p < 0.05, Fig. 1E,G).

Fig. 1.

Assessment of oxidative stress-related changes in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) in vitro after ethanol (EtOH) treatment. PBMCs were examined after treatment with several concentrations (0 [control], 6.2, 12.5, 25, 50, and 100 mM) over (A–D) 24 and (E–H) 72 h of exposure. (A,E) Relative fold changes in intercellular ROS expression levels compared to control. (B,F) Relative fold changes in cell viability compared to control. (C,G) Relative fold changes in NOX2 mRNA expression level compared to control. (D,H) Relative fold changes in mRNA expression levels of SOD1, SOD2, GPX, and CAT compared to control. Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM. (n = 3; *p < 0.05 compared to control; n.s., not significant; Student’s t-test).

No significant differences were observed in cell viability between the control and EtOH treatments at 24 h (Fig. 1B); however, the relative fold change was significantly decreased with the EtOH treatments (50 and 100 mM) compared to the control after 72 h of exposure (p < 0.05, Fig. 1F).

Except for NOX2, mRNA expression levels of the other four antioxidant-related genes were significantly decreased with all EtOH treatments compared to the control after 24 h of exposure (p < 0.05, Fig. 1D). GPX1 and CAT mRNA expression levels were significantly decreased with all EtOH treatments compared to the control after 72 h of exposure, and those of SOD1 and SOD2 were significantly decreased with all EtOH treatments except with 6.2 mM (p < 0.05, Fig. 1H). These results suggest that the antioxidant enzymes in PBMCs tend to decrease with increasing and early exposure to EtOH in vitro.

Students’ characteristics

The baseline characteristics of the 197 male students without smoking habits (35 adolescents aged 18–19 years and 162 young adults aged 22–29 years) are shown in Table 1. All 35 adolescents were non-drinkers and 162 young adults were drinkers. The drinkers were divided into three groups (light, < 0.31 g/kg/week: n = 63; moderate, 0.31–1.59 g/kg/week: n = 66; heavy, > 1.59 g/kg/week: n = 33) according to their average weekly alcohol consumption. In the 162 drinkers, no significant differences in age and BMI were observed among the three groups. No significant differences in AST and ALT were observed among the three groups, whereas the GGT level was significantly increased in the heavy-drinking group compared to the light-drinking group (p < 0.05). Further, the MCV level was significantly increased in the heavy-drinking groups compared to the light-drinking group (p < 0.05). In this study, clinical differences among non-drinkers were assessed between adolescent non-drinkers and young adults who are light drinkers, who were regarded as “non-drinking” young adults. No significant differences in AST, ALT, GGT, and MCV levels were observed between adolescent non-drinkers and light drinkers; however, significant differences were observed in DBP, TG, LDL-C, platelet count, and FBS levels (p < 0.05). These parameters may be influenced by aging and lifestyle habits. Therefore, in this study, the expression levels of several OS-related genes under early EtOH exposure were assessed in 162 young adults, excluding adolescents.

Table 1.

Clinical background of 162 young adult drinkers (ages 22–29) and 35 adolescent non-drinkers (ages 18–19).

| Parameter | Non-drinkers (age 18–19) | Drinkers (age 22–29) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| None (n = 35) | Light (n = 63) | Moderate (n = 66) | Heavy (n = 33) | |

| Age (years) | 18.5 ± 0.1 | 23.8 ± 0.3** | 23.9 ± 0.3** | 24.2 ± 0.4** |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 21.1 ± 0.5 | 20.9 ± 0.3 | 20.8 ± 0.3 | 21.4 ± 0.4 |

| BW (kg) | 61.7 ± 1.5 | 62.2 ± 1.0 | 62.3 ± 1.0 | 65.3 ± 1.5 |

| SBP (mmHg) | 118.7 ± 2.1 | 119.6 ± 1.5 | 124.1 ± 1.4* | 123.7 ± 1.9 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 66.9 ± 1.3 | 73.1 ± 1.1** | 75.2 ± 1.2** | 73.2 ± 1.5* |

| Alcohol consumption (g/kg/week) | 0.13 ± 0.01 | 0.87 ± 0.05## | 2.97 ± 0.32##†† | |

| Daily average consumtion (g/kg/day) | 0.08 ± 0.01 | 0.28 ± 0.01## | 0.58 ± 0.06##†† | |

| Frequency (days/week) | 1.4 ± 0.1 | 3.4 ± 0.2## | 5.2 ± 0.3##†† | |

| AST (U/L) | 20.4 ± 0.7 | 19.7 ± 0.7 | 20.8 ± 0.9 | 20.0 ± 1.6 |

| ALT (U/L) | 18.7 ± 1.4 | 18.5 ± 1.4 | 20.4 ± 1.6 | 19.6 ± 3.5 |

| GGT (U/L) | 19.9 ± 1.2 | 22.5 ± 1.4 | 30.0 ± 2.9* | 29.3 ± 3.3*# |

| TG (mg/dL) | 45.5 ± 2.4 | 94.7 ± 5.2** | 85.4 ± 6.4**# | 107.0 ± 17.5** |

| HDL-C (mg/dL) | 62.5 ± 1.8 | 59.6 ± 1.5 | 62.8 ± 1.5 | 64.6 ± 2.2 |

| LDL-C (mg/dL) | 96.3 ± 4.8 | 106.2 ± 3.4* | 103.0 ± 3.5 | 103.6 ± 4.6 |

| UA (mg/dL) | 5.6 ± 0.1 | 5.7 ± 0.1 | 5.6 ± 0.1 | 6.1 ± 0.2*† |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.83 ± 0.01 | 0.83 ± 0.01 | 0.83 ± 0.01 | 0.84 ± 0.02 |

| CRP (mg/dL) | 0.05 ± 0.03 | 0.03 ± 0.00 | 0.05 ± 0.01 | 0.05 ± 0.01 |

| Platelet count (10,000/µL) | 28.6 ± 1.0 | 24.3 ± 0.6** | 26.3 ± 0.6* | 24.4 ± 0.7* |

| FBS (mg/dL) | 79.7 ± 0.8 | 84.5 ± 1.7 | 82.5 ± 0.8* | 93.5 ± 7.3**† |

| MCV (fL) | 92.8 ± 0.5 | 93.0 ± 0.4 | 94.0 ± 0.4 | 95.0 ± 0.7*# |

*p < 0.05 compared with non-drinkers **p < 0.001 compared with non-drinkers.

#p < 0.05 compared with light drinkers among drinkers ##p < 0.001 compared with light drinkers among drinkers.

†p < 0.05 High drinkers compared with moderate drinkers ††p < 0.001 High drinkers compared with moderate drinkers.

Values are presented as means ± SEM.

Screening expression levels of 84 antioxidant-related genes

For screening, we first examined the mRNA expression levels of 84 antioxidant-related genes in the PBMCs of 24 randomly selected drinkers (light: n = 8; moderate: n = 8; heavy: n = 8; Table S1) using a commercially available expression array (Table S2). Genes whose mRNA expression levels were > 1.5-fold higher between at least two of the three groups were regarded as upregulated12. The mRNA expression levels of BNIP3, CAT, CCL5, cytochrome b-245 alpha polypeptide (CYBA), diacylglycerol kinase kappa (DGKK), dual specificity phosphatase (DUSP) 1, Soluble epoxide hydrolase (EPHX) 2, GPX1, GPX7, MT3, neutrophil cytosol factor (NCF) 1, PDLIM1, peroxiredoxin (PRDX) 6, SOD1, and TTN were > 1.5-fold higher between at least two of the three groups (Table 2). However, none of the differences were significant, likely because of the small number of patients examined.

Table 2.

Screening analysis of antioxidant-related gene expression in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) of 24 drinkers.

| Gene | Drinkers | Gene | Drinkers | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Light (n = 8) | Moderate (n = 8) | Heavy (n = 8) | Light (n = 8) | Moderate (n = 8) | Heavy (n = 8) | ||

| ALB | ND | ND | ND | MTL5 | ND | ND | ND |

| ALOX12 | 1.13 ± 0.50 | 0.85 ± 0.47 | 0.99 ± 0.36 | NCF1 | 1.64 ± 0.42 | 1.14 ± 0.49 | 1.08 ± 0.49 |

| ANGPTL7 | ND | ND | ND | NCF2 | 1.38 ± 0.59 | 1.40 ± 0.59 | 1.59 ± 0.61 |

| AOX1 | ND | ND | ND | NME5 | ND | ND | ND |

| APOE | ND | ND | ND | NOS2 | ND | ND | ND |

| ATOX1 | 5.56 ± 2.37 | 5.94 ± 2.39 | 6.42 ± 2.35 | NOX5 | ND | ND | ND |

| BNIP3 | 1.31 ± 0.23 | 0.51 ± 0.23 | 0.38 ± 0.17 | NUDT1 | 0.38 ± 0.15 | 0.27 ± 0.12 | 0.35 ± 0.15 |

| CAT | 1.52 ± 0.46 | 0.90 ± 0.27 | 1.75 ± 0.47 | OXR1 | 0.48 ± 0.15 | 0.33 ± 0.16 | 0.43 ± 0.18 |

| CCL5 | 1.27 ± 0.49 | 0.97 ± 0.32 | 0.59 ± 0.23 | OXSR1 | 0.58 ± 0.16 | 0.59 ± 0.25 | 0.72 ± 0.29 |

| CCS | 0.44 ± 0.14 | 0.39 ± 0.11 | 0.52 ± 0.15 | PDLIM1 | 1.56 ± 0.59 | 0.71 ± 0.23 | 0.74 ± 0.23 |

| CSDE1 | 2.92 ± 1.19 | 1.72 ± 0.62 | 2.86 ± 1.32 | PIP3-E | 0.54 ± 0.15 | 0.51 ± 0.25 | 0.48 ± 0.18 |

| CYBA | 2.16 ± 0.91 | 0.73 ± 0.27 | 1.05 ± 0.27 | PNKP | 0.42 ± 0.14 | 0.29 ± 0.12 | 0.36 ± 0.14 |

| CYGB | ND | ND | ND | PRDX1 | 0.31 ± 0.12 | 0.25 ± 0.12 | 0.35 ± 0.14 |

| DGKK | 1.38 ± 0.44 | 0.71 ± 0.25 | 1.04 ± 0.35 | PRDX2 | 0.61 ± 0.22 | 0.61 ± 0.25 | 0.61 ± 0.32 |

| DHCR24 | 0.40 ± 0.14 | 0.43 ± 0.17 | 0.40 ± 0.14 | PRDX3 | 0.30 ± 0.11 | 0.21 ± 0.11 | 0.22 ± 0.03 |

| DUOX1 | ND | ND | ND | PRDX4 | 0.48 ± 0.14 | 0.43 ± 0.21 | 0.50 ± 0.22 |

| DUOX2 | ND | ND | ND | PRDX5 | 0.50 ± 0.16 | 0.50 ± 0.25 | 0.42 ± 0.14 |

| DUSP1 | 1.40 ± 0.62 | 1.92 ± 0.96 | 1.75 ± 0.90 | PRDX6 | 1.13 ± 0.46 | 0.66 ± 0.24 | 0.65 ± 0.20 |

| EPHX2 | 1.40 ± 0.44 | 0.55 ± 0.17 | 0.75 ± 0.29 | PREX1 | 0.32 ± 0.12 | 0.25 ± 0.12 | 0.27 ± 0.08 |

| EPX | ND | ND | ND | PRG3 | ND | ND | ND |

| FOXM1 | 0.54 ± 0.15 | 0.37 ± 0.15 | 0.52 ± 0.17 | PRNP | 0.69 ± 0.15 | 0.54 ± 0.18 | 0.44 ± 0.18 |

| GLRX2 | ND | ND | ND | PTGS1 | 0.46 ± 0.17 | 0.33 ± 0.24 | 0.36 ± 0.15 |

| GPR156 | ND | ND | ND | PTGS2 | 0.49 ± 0.16 | 0.48 ± 0.24 | 0.36 ± 0.14 |

| GPX1 | 0.98 ± 0.31 | 1.74 ± 0.45 | 0.70 ± 0.14 | PXDN | ND | ND | ND |

| GPX2 | ND | ND | ND | PXDNL | ND | ND | ND |

| GPX3 | 0.59 ± 0.16 | 0.43 ± 0.17 | 0.42 ± 0.17 | RNF7 | 0.51 ± 0.14 | 0.39 ± 0.14 | 0.36 ± 0.15 |

| GPX4 | 0.50 ± 0.16 | 0.37 ± 0.15 | 0.40 ± 0.15 | SCARA3 | ND | ND | ND |

| GPX5 | ND | ND | ND | SELS | 4.51 ± 1.88 | 5.63 ± 2.24 | 4.15 ± 1.34 |

| GPX6 | ND | ND | ND | SEPP1 | 0.59 ± 0.15 | 0.42 ± 0.24 | 0.43 ± 0.18 |

| GPX7 | 1.29 ± 0.43 | 0.62 ± 0.22 | 1.14 ± 0.43 | SFTPD | 0.49 ± 0.16 | 0.42 ± 0.24 | 0.37 ± 0.15 |

| GSR | 0.86 ± 0.28 | 0.81 ± 0.47 | 0.76 ± 0.28 | SGK2 | 7.24 ± 2.7 | 7.38 ± 0.32 | 6.38 ± 2.62 |

| GSS | 0.32 ± 0.12 | 0.31 ± 0.12 | 0.36 ± 0.15 | SIRT2 | 0.31 ± 0.12 | 0.29 ± 0.13 | 0.35 ± 0.14 |

| GSTZ1 | 0.49 ± 0.17 | 0.52 ± 0.25 | 0.46 ± 0.14 | SOD1 | 1.20 ± 0.23 | 0.62 ± 0.20 | 0.54 ± 0.13 |

| GTF2I | 0.33 ± 0.12 | 0.28 ± 0.09 | 0.26 ± 0.07 | SOD2 | 0.48 ± 0.16 | 0.42 ± 0.24 | 0.48 ± 0.18 |

| KRT1 | ND | ND | ND | SOD3 | ND | ND | ND |

| LPO | ND | ND | ND | SRXN1 | 0.28 ± 0.12 | 0.28 ± 0.13 | 0.36 ± 0.15 |

| MBL2 | ND | ND | ND | STK25 | 0.61 ± 0.15 | 0.51 ± 0.24 | 0.54 ± 0.16 |

| MGST3 | 1.99 ± 0.99 | 1.73 ± 0.68 | 2.11 ± 1.23 | TPO | ND | ND | ND |

| MPO | 0.31 ± 0.12 | 0.24 ± 0.12 | 0.27 ± 0.08 | TTN | 1.89 ± 0.35 | 0.86 ± 0.25 | 1.31 ± 0.61 |

| MPV17 | 0.85 ± 0.29 | 0.58 ± 0.25 | 0.71 ± 0.29 | TXNDC2 | ND | ND | ND |

| MSRA | 0.63 ± 0.24 | 0.54 ± 0.24 | 0.62 ± 0.18 | TXNRD1 | 0.41 ± 0.15 | 0.42 ± 0.24 | 0.36 ± 0.14 |

| MT3 | 1.51 ± 0.47 | 0.95 ± 0.34 | 0.94 ± 0.32 | TXNRD2 | 0.32 ± 0.12 | 0.41 ± 0.23 | 0.36 ± 0.15 |

Values are presented as means ± SEM. ND not determined.

Bold text indicates upregulated genes; that is, those with > 1.5-fold higher expression levels between any two of the three groups of drinkers.

Expression levels of 15 antioxidant-related genes in drinkers

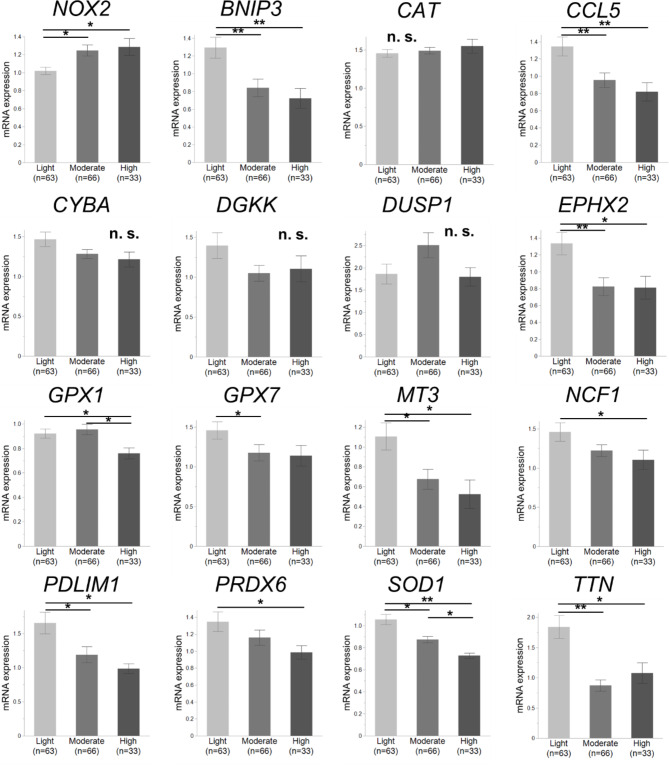

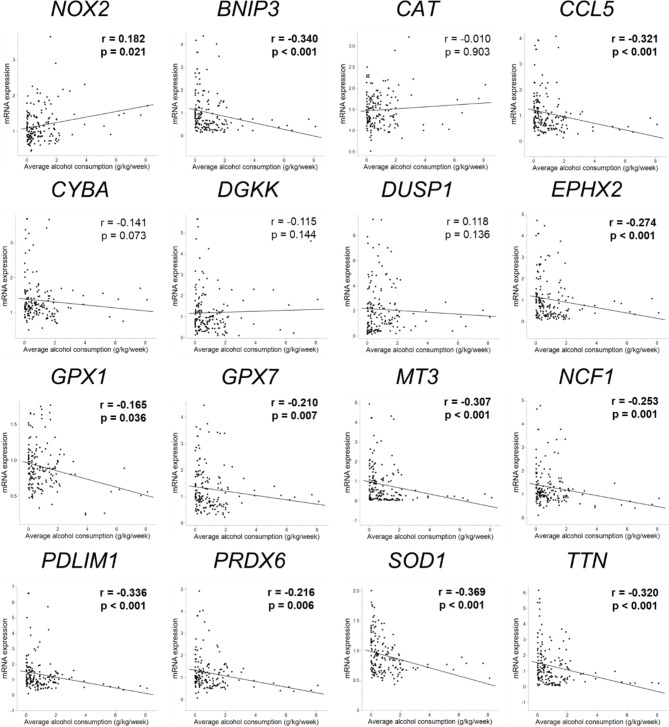

We determined the mRNA expression levels of these 15 candidate genes in the PBMCs of all 197 students via real-time PCR using specific primers and probes, and the NOX2 mRNA expression level was also examined as an assessment of the degree of OS in PBMCs. Notably, significant differences for antioxidant-related genes were observed between adolescent non-drinkers and light drinkers (p < 0.05, Fig. S1); therefore, the expression levels of these genes in drinkers were assessed among 162 young adults. Only SOD1 expression was significantly downregulated in the heavier-drinking group compared to that in any two of the three drinking groups (p < 0.05, Fig. 2). The expression levels of BNIP3, CCL5, EPHX2, GPX1, GPX7, MT3, NCF1, PDLIM1, PRDX6, and TTN were significantly downregulated in the heavier-drinking group in at least two of the three groups (p < 0.05). The expression of all 11 genes was negatively correlated with average weekly alcohol consumption (p < 0.05, Fig. 3), and SOD1 expression was the most negatively correlated (p < 0.001). The NOX2 expression level was significantly upregulated in the moderate- and heavy-drinking groups compared to the light group (p < 0.05); furthermore, it was positively correlated with average weekly alcohol consumption (p = 0.021). Similar results were observed in the changes and correlations in the expression of these 15 genes and NOX2 according to average daily alcohol consumption and frequency of alcohol consumption (Table S3). These results suggest that the expression of several antioxidant-related genes, especially SOD1, in peripheral immunity during young EtOH exposure tends to decrease with an increase in consumption.

Fig. 2.

mRNA expression levels of NOX2 and 15 antioxidant-related genes in 162 young adults. Students were divided into three alcohol-drinking groups (light: n = 63; moderate: n = 66; heavy: n = 33) by average weekly alcohol consumption. Only the SOD1 expression level was significantly downregulated in the heavier drinking group compared to any two of the three drinking groups. The NOX2 expression level was significantly upregulated in the moderate- and heavy-drinking groups compared to the light group. Expression levels of BNIP3, CCL5, EPHX2, GPX1, GPX7, MT3, NCF1, PDLIM1, PRDX6, and TTN were significantly downregulated in the heavier-drinking group between at least two of the three groups. Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.001; n.s., not significant; Wilcoxon Kruskal–Wallis test).

Fig. 3.

Correlations between mRNA expression levels of NOX2 and 15 antioxidant-related genes and average weekly alcohol consumption in 162 young adults. NOX2 expression was positively correlated with average weekly alcohol consumption, and expression levels of 11 other mRNAs: SOD1, BNIP3, CCL5, EPHX2, GPX1, GPX7, MT3, NCF1, PDLIM1, PRDX6, and TTN were negatively correlated with average weekly alcohol consumption. Associations with p < 0.05 are shown in bold.

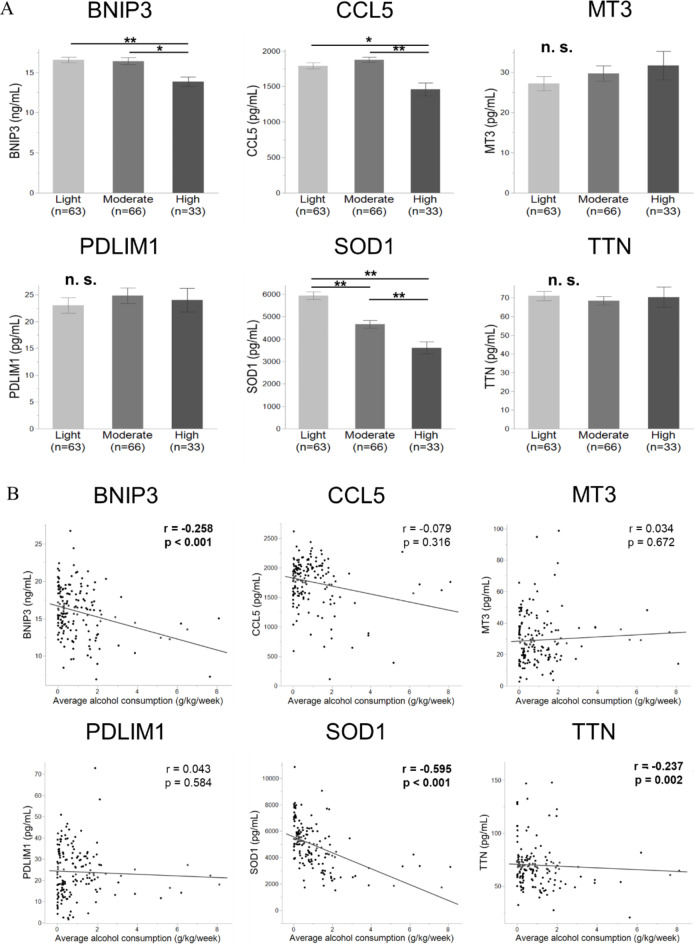

Plasma levels of six antioxidant-related proteins in drinkers

We measured the plasma levels of several antioxidant-related proteins using commercially available ELISA kits (Table S4). In this study, genes with correlation coefficients > 0.30 were regarded as having stronger correlations with EtOH consumption. Proteins of the six applicable antioxidant-related genes, BNIP3, CCL5, MT3, PDLIM1, SOD1, and TTN, were selected to assess significant candidate indicators of EtOH exposure at a young age. Only the SOD1 plasma level was significantly downregulated in the heavier-drinking group between any two of the three drinking groups (p < 0.001, Fig. 4A). The plasma levels of BNIP3 and CCL5 were significantly downregulated in the heavier drinking group in at least two of the three groups (p < 0.05). No significant difference in MT3, PDLIM1, and TTN plasma levels was observed among the three groups. Among the proteins of the six antioxidant-related genes, the plasma levels of BNIP3, SOD1, and TTN were negatively correlated with average weekly alcohol consumption (p < 0.002, Fig. 4B), and SOD1 plasma levels were most negatively correlated (p < 0.001). Similar results were observed for the changes and correlations of plasma levels of these three proteins according to the average daily alcohol consumption and frequency of alcohol consumption (Table S5). These results suggest that a decreased plasma level of SOD1 in the peripheral blood is a powerful indicator of increased EtOH consumption.

Fig. 4.

Plasma levels of six antioxidant-related proteins and correlations between the levels and average weekly alcohol consumption in 162 young adults. (A) The six applicable antioxidant-related gene proteins, namely those of the genes BNIP3, CCL5, MT3, PDLIM1, SOD1, and TTN, were selected. Only the SOD1 plasma level was significantly downregulated in the heavier-drinking group between any two of the three drinking groups. Plasma levels of BNIP3 and CCL5 were significantly downregulated in the heavier-drinking group between at least two of the three groups (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.001; n.s., not significant; Wilcoxon Kruskal–Wallis test). (B) Plasma levels of BNIP3, SOD1, and TTN were negatively correlated with average weekly alcohol consumption. Associations with p < 0.05 are shown in bold.

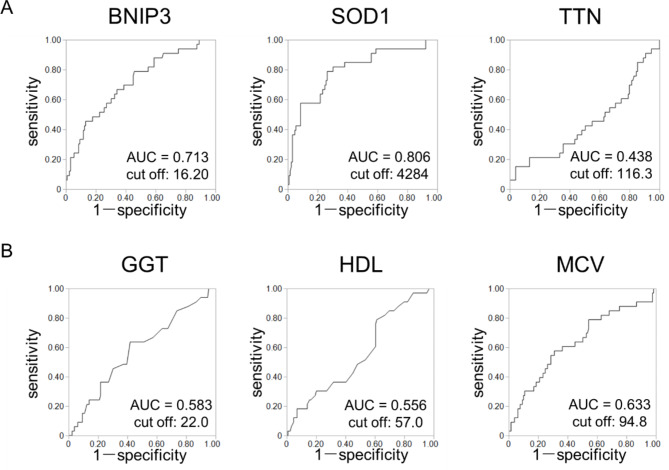

SOD1 as a sensitive indicator of heavy alcohol consumption

In this study, we assessed the changes and correlations of 16 clinical and biochemical parameters in drinkers according to their average weekly and daily alcohol consumption and the frequency of alcohol consumption (Table S6). GGT, HDL-C, and MCV levels were positively correlated with average weekly and daily alcohol consumption (p < 0.025), and GGT and MCV levels were positively correlated with daily frequency (p < 0.012). As shown in Fig. 5, the selection of sensitive indicators of heavy consumption under EtOH exposure at a young age was assessed among three antioxidant-related genes: BNIP3, SOD1, and TTN (Fig. 5A) and the three previously mentioned alcohol-related parameters: GGT, HDL-C, and MCV levels (Fig. 5B), based on the area under the curve (AUC). Of the six AUC values, the SOD1 level had the highest AUC value of 0.806. These results suggest that a decreased plasma level of SOD1 may be a sensitive indicator of heavy alcohol consumption in young adults when they have been exposed to EtOH at a young age.

Fig. 5.

Selection of the sensitive indicators of high alcohol consumption at a young age. Indicators were assessed based on the area under curve (AUC) values calculated from receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves. (A) ROC curves for plasma levels of antioxidant-related genes: BNIP3, SOD1, and TTN. (B) ROC curves for levels of alcohol-related parameters: gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), and mean corpuscular volume (MCV). Of these 6 AUC values, the SOD1 level had the highest AUC value of 0.806.

Discussion

In this study, we examined the expression of several antioxidant-related genes in PBMCs in vitro and found that the antioxidant system was impaired by EtOH exposure at a young age. Next, we examined the expression of 84 antioxidant-related genes in PBMC samples from young male adults consuming alcohol early in life and found that the antioxidant system tended to be impaired according to the degree of alcohol consumption. Our results demonstrated that, among these 84 genes, SOD1 is a powerful indicator of an impaired antioxidant system in peripheral immunity and can be a sensitive indicator of heavy alcohol consumption in young adulthood during EtOH exposure at a young age.

The antioxidant system in peripheral immunity was found to be impaired by EtOH exposure at a young age in both in vitro and human studies. Notably, the system was impaired even with light alcohol consumption. Chronic, excessive alcohol consumption induces ROS production, which in turn induces OS in various organs and cells, including immune cells17,18, consequently impairing the immune system19. Alcohol-induced oxidative damage leads to the impairment of antioxidant activity, including those of SOD, CAT, and GPx20–23, and significantly affects the antioxidant-related expression of SOD and GPX in PBMCs6,13. However, consensus has not been reached on the decrease in antioxidant-related gene expression following acute EtOH exposure24. No reports have mentioned the decrease in antioxidant-related gene expression in peripheral immunity under EtOH exposure at a young age and damage to antioxidant enzymes due to light drinking. Light-to-moderate alcohol consumption increases the risk of developing cancer8,9, and a weekly alcohol consumption of 20 g/week adversely affects fetal growth25,26. Light-to-moderate alcohol consumption may also adversely affect the antioxidant system in peripheral immunity.

The reason why EtOH impairs PBMCs and reduces their antioxidant activity remains unknown. Originally, antioxidant enzymes are upregulated as a compensatory response to protect PBMCs from the damage of heavy alcohol consumption6. Alcohol intake alters the functions of both innate and adaptive immune cells, including PBMCs, and immune dysfunction has been associated with alcohol-induced end organ damage27. Chronic alcohol exposure impairs several immune cells, reduces the dysfunction of peripheral T cells, and causes the loss of peripheral B cells28. In this process, the activity of antioxidant enzymes such as SOD and GPx is impaired by decreasing copper/zinc or selenium deposits in the body26,29. Although similar reports on peripheral immune cells remain lacking, the antioxidant system in PBMCs may be impaired by a similar mechanism.

SOD is an enzyme that alternately catalyzes the dismutation of the superoxide radical into ordinary molecular oxygen and hydrogen peroxide, compared to the catalase and glutathione family30,31. Superoxide is a by-product of oxygen metabolism and, if not regulated, causes many types of cell damage. Therefore, SOD is an important antioxidant defense in nearly all living cells exposed to oxygen30. Lack of SOD decreases EtOH metabolism and is linked to enhanced OS29. Three forms of SOD are present in all mammals, including humans: SOD1 in the cells, SOD2 in the mitochondria, and SOD3 outside the cells30. SOD1, a key antioxidant marker in this study, also plays a protective role against OS and protects many of the cellular structures except the mitochondrial membrane. A lack of SOD1 results in accelerated aging, increased oxidative DNA damage, and promotes carcinogenesis, such as hepatocellular carcinoma32–34. In this study, the decreased level of SOD1 was the most sensitive indicator of EtOH exposure at a young age in human peripheral immunity. Although the reason for this is unclear, SOD1 itself is a major target of oxidative damage and also acts as a transcription factor regulating the OS response32. EtOH-induced oxidative damage primarily targets SOD1, and a reduced SOD1 mRNA level has been observed in the liver tissues of EtOH-fed mice35. Therefore, SOD1 can be more susceptible to oxidative damage from EtOH exposure, unlike the catalase and glutathione family36. Furthermore, SOD1 in PBMCs may be more susceptible to oxidative damage from EtOH exposure in blood circulation. When considering non-alcohol-induced diseases, SOD1 can be pathogenic in various neurodegenerative diseases, and mutant SOD1 is especially associated with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS)30,33,37,38. However, alcohol consumption is not directly related to the pathology of ALS39, and the role of SOD1 may differ between ALS and alcohol-induced pathology.

In addition to SOD1, BNIP3, CCL5, MT3, PDLIM1, and TTN showed relatively strong negative correlations with the amount of alcohol consumed early in life. Acute EtOH treatment increases BNIP3 expression in the liver40, and BNIP3-dependent mitophagy limits ROS production and promotes cell survival in cardiomyocytes, tumor cells, and hepatocytes41. BNIP3 is also expressed in PBMCs42, and its deletion increases cellular ROS43. CCL5 is a member of the proinflammatory cytokine superfamily and the CC chemokine family and is produced by PBMCs, especially monocytes44. Patients with alcoholic liver disease have increased hepatic CCL5 levels45, and EtOH augments CCL5 expression in vivo46. CCL5, via GPX1 activation, protects hepatocytes from ROS damage47. MT has a high affinity for zinc48, and zinc sulfate has antioxidant effects on acute EtOH-induced oxidative damage49. MT can scavenge reactive species, and MT3 exerts a greater protective effect against DNA degradation from oxidative damage than that of MT1/250. In peripheral immunity, activated MT3 impairs antibacterial immunity51; however, the expression and detailed role of MT3 in PBMCs remain unknown.

PDLIM1 has several important roles in cytoskeletal organization, neuronal signaling, and organ development. It also plays roles in cell proliferation and metastasis during tumor initiation and progression when expressed in PBMCs52,53. PDLIM1 has an antioxidant effect on neuro- and cardio-degenerative diseases53. TTN has an accepted role in mechanical protein in muscle cells, such as passive force production and stabilization of sarcomeres, and has controversial contributions to residual force enhancement, passive force enhancement, energetics, and work production in shortening muscles54. TTN is expressed in human T and B lymphocytes as a critical and versatile housekeeping regulator of T lymphocyte trafficking55. Chronic alcohol consumption reduces the TTN level and promotes muscle atrophy56. ROS modify TTN in cardiomyocytes57; however, the reduction of ROS by TTN is unclear.

These reports suggest that all five antioxidant-related genes contribute to the reduction of ROS damage via antioxidant reactions. However, the detailed mechanisms have not been elucidated, and these associations with EtOH-induced OS in peripheral immunity are unknown and must be elucidated in the future. These five genes may also be targets of oxidative damage via unknown mechanisms, similar to SOD1, which is a novel finding in this study.

In this study, SOD1 at the plasma and mRNA levels was most negatively correlated with the amount of alcohol consumed. Plasma SOD1 levels are significant indicators of cutaneous leishmaniasis and ALS38,58; however, the change in SOD1 plasma levels as well as in the BNIP3, CCL5, MT3, PDLIM1, and TTN plasma levels due to EtOH exposure remains unknown. Possibly, SOD1, BNIP3, CCL5, MT3, PDLIM1, and TTN are secreted from not only PBMCs but also other cells such as vascular endothelial, muscle, nerve, and cancer cells, which may affect their plasma levels. Among the six antioxidant-related genes, SOD1 may be secreted at greater levels from PBMCs under early EtOH exposure. Furthermore, our results indicate that, compared to GGT, HDL, and MCV, the SOD1 level is a more sensitive indicator of heavy alcohol consumption in young male adults. The levels of GGT, HDL, and MCV are higher in heavy drinkers among adults and are clinically used as significant indicators of heavy alcohol consumption59,60. Although the reason for the above results is unclear, intracellular SOD1 in PBMCs, a major target of oxidative damage23,25, may be impaired earlier by EtOH exposure, and the impairment may be faster than GGT, HDL, and red blood cells, which are gradually impaired by exposure to various mechanisms.

In this study, we demonstrated that SOD1 is an important indicator of the downregulation of the antioxidant system in peripheral immunity under EtOH exposure at a young age and among heavy alcohol consumers at a young age. Human PBMC samples are required to verify the results of decreased antioxidant-related gene expression obtained from in vitro PBMCs. To eliminate errors induced by sex differences, we standardized our investigation to male PBMC samples; however, this was a limitation. In the future, a validation study including both male and female PBMC and plasma samples will be necessary for clinical applications of our findings. As females are more susceptible to alcohol-induced liver damage than males22, differential SOD1 expression by sex may also be observed in susceptibility to liver damage. Therefore, our results should only be generalized following separate analyses of males and females to avoid sex biases. Furthermore, we excluded subjects with smoking habits and several diseases that may affect OS, and focused on examining the relationship between early alcohol drinking and OS; this was a limited study. The relationship between alcohol drinking and OS should be examined from various perspectives, including smoking and these diseases, which will be a future task.

In conclusion, the antioxidant system in peripheral immunity tends to be impaired by EtOH exposure at a young age. Among several antioxidant-related genes, SOD1 is a powerful indicator of antioxidant system impairment and can be a sensitive indicator of heavy alcohol consumption in young adulthood. Our data suggest that even a small amount of early alcohol consumption downregulates the antioxidant system, which can be a novel risk factor for OS-induced diseases. Our study introduces the prospect of preventing immunity-related disorders caused by an increase in OS through guidance on appropriate alcohol drinking in young adulthood and will contribute to the early detection of excessive drinkers among young adults.

Materials and methods

University students (undergraduates and graduates)

From March 2021 to June 2022, 197 male university students (young adults aged 22–29 years, n = 162; adolescents aged 18–19: n = 35) who underwent health checkups overnight at a university in Japan were enrolled in the study. According to Erikson’s psychosocial theory, adolescence (12–18 years old) and young adulthood (19–29 years old) are divided at age 18–1961,62. In this study, first-year students were 18–19 years old and integrated as “adolescents”. All the participants were Japanese and provided informed consent to participate in this study. To avoid the effects of OS caused by smoking and several diseases, the participants were non-smokers and had no symptoms of acute infectious diseases, history of malignant tumors, or inflammatory or autoimmune diseases. Female students were excluded to eliminate differences in susceptibility to alcohol exposure between the sexes; notably, they have been found to consume less alcohol than males at our university63,64. In Japan, drinking alcohol under the age of 20 is prohibited by law, and all adolescents are non-drinkers. Although the recent rate of alcohol drinking among adolescents in Japan is about 2%65, in this study, the non-drinkers had no alcohol-drinking habits through our detailed interviews. This study was approved by the Ethics Committees of the University of Tokyo Clinical Research Review Board (Protocol No. 18-277). The study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki guidelines and regulations.

Alcohol consumption

The health checkup included the completion of a standard questionnaire, a physical examination, and biochemical tests. The questionnaire, which was created for this study, evaluated alcohol drinking habits, and the average daily consumption per kg of body weight (BW) (g/kg/day) and frequency (days/week) of alcohol consumption (amount of pure alcohol) were recorded66,67. To obtain accurate information on alcohol consumption, we carefully explained to the participants that self-reporting would not be detrimental to them. In this study, the daily consumption was defined as the average drinking amount only on drinking days, and weekly consumption (g/kg/week) was calculated by multiplying the frequency by the daily consumption. Young adults who were exposed to EtOH early were divided into three alcohol-drinking groups: light, moderate, and heavy, according to their average weekly alcohol consumption, compared to adolescent non-drinkers. The non-drinkers were also non-smokers, and had no comorbidities, no history of alcohol consumption, no family history of alcohol/drug use, or no special medications, which may affect OS.

Standard definitions of alcohol consumption vary according to the country68. First, in this study, “heavy-drinking” group was defined based on the alcohol consumption of > 100 g/week, with a higher mortality rate10,69, whereas alcohol consumption of ≤ 100 g/week was considered “light-to-moderate drinking”69. The alcohol-drinking group of ≤ 100 g/week was dichotomized into 20–100 g/week (moderate-drinking) and < 20 g/week (light-drinking). Next, individual average weekly alcohol consumption (g/kg/week) was calculated. Furthermore, to recalculate the two cutoff values, 20 and 100 (g/week) in g/kg/week, they were divided by the mean of the participants’ BW, 62.8 kg; its standard error was 0.6. Finally, they were divided into the following three groups: light (< 0.31 g/kg/week), moderate (0.31–1.59 g/kg/week), and heavy (> 1.59 g/kg/week).

Clinical parameters

Body height, BW, body mass index (BMI), systolic blood pressure, and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) were measured on the day of the health checkup. Biochemical parameters included the levels of AST, ALT, GGT, triglyceride (TG), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), uric acid, creatinine, C-reactive protein, and fasting blood glucose (FBS) and platelet count and MCV.

PBMC samples

PBMCs were separated from the whole blood samples of 197 university students using a Ficoll kit using 8 mL Vacutainer Cell Processing tubes (BD Biosciences; Franklin Lakes, NJ, United States), as described in our previous study12. All participants provided informed consent for PBMC collection. In brief, blood samples were processed within 4 h of blood collection by collecting the PBMC-containing upper phase and washing with ice-cold phosphate buffered saline (PBS). PBMCs were either frozen for later experiments or used directly for the enrichment of the erythroblast population.

Cell culture

PBMCs were obtained from healthy, non-drinking university students (non-drinkers) and were suspended in 10 mL RPMI 1640 medium (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) supplemented with penicillin (100 U/mL), streptomycin (100 µg/mL), L-glutamine, and 10% fetal bovine serum after two washes (1500 g, 5 min, 23 °C). They were adjusted to 5.0 × 105/mL and incubated at 37 °C in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2 for 24 h in 6-well plates with RPMI 1640 medium (1.0 × 106 cells/well) as previously reported70,71. At 70–80% confluence, PBMCs were treated with or without (used as a control) various concentrations of EtOH (6.25, 12.5, 25, 50, and 100 mM) for 24–72 h. According to the Widmark formula, EtOH 6.25 mM was equivalent to 0.18 g/kg/day, and 100 mM to 2.93 g/kg/day, in human daily alcohol consumption72; as shown in Table 1, the range of EtOH 6.25–100 mM corresponded to moderate-heavy drinking. Thereafter, PBMCs were withdrawn, followed by two or three washes with PBS, and were directly used or frozen for reactive oxygen species (ROS) detection, cell viability, and examination of antioxidant-related gene expression. EtOH was obtained from Wako Industries (Osaka, Japan).

ROS detection

Intercellular ROS formation was assessed using a DCFDA/H2DCFDA-Cellular ROS Assay kit (Abcam, Cambridge, UK) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. DCFDA is a cell-permeable non-fluorescent probe that diffuses into the cytoplasm and then forms a non-fluorescent moiety through deacetylation by cellular esterase. It is oxidized by cellular ROS to form the fluorescent product DCF73.

PBMCs were cultured in gelatin-coated 96-well black plates (5.0 × 104 cells/well) and 6-well plates (2.0 × 106 cells/well) overnight and treated with or without (used as a control) various concentrations of EtOH (6.25, 12.5, 25, 50, and 100 mM) for 24–72 h at 37 °C in an atmosphere containing 5% CO2, followed by incubation with 20 µM DCFDA at 37 °C in the dark for 45 min. After two or three washes with PBS buffer, the fluorescence intensity of cellular ROS in the 96-well black plates was measured at 485/535 nm using a DTX plate reader (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA, USA). ROS levels are expressed as the relative fold change in DCF fluorescence units with respect to the control.

Cell viability

Cell viability was evaluated using an XTT Cell Viability Assay kit (Biological Industries, Cromwell, CT, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. PBMCs were cultured in gelatin-coated 96-well plates (5.0 × 104 cells/well) with or without (used as a control) various concentrations of EtOH (6.25, 12.5, 25, 50, and 100 mM) for 24–72 h at 37 °C with 5% CO2. After incubation, the medium was discarded, and 100 µL of fresh medium was added to each well. Then, 50 µL of the activated XTT solution was added, and samples were incubated for 2 h at 37 °C. The absorbance (λ = 450 nm) was measured using the above DTX plate reader. The percentage of cell viability was calculated using the following formula:

Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction

mRNA was extracted from PBMCs using the RNeasy Micro Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), and complementary DNA was synthesized using the RT2 First Strand Kit (Qiagen) as previously reported12. First, TaqMan™ Array, Human Antioxidant Mechanisms, Fast 96-well (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) was used to examine the expression levels of 84 antioxidant-related genes in 24 young adults (light: moderate: heavy = 8: 8: 8) who were randomly selected. A list of the genes examined using this array is shown in Table S2. Gene expression analysis was performed using TaqMan PCR (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Next, the expression levels of the identified genes in all 197 students were determined using TaqMan PCR. The same PCR primers and probes as those used for the above array were used. The other specific PCR primer and probe were for nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase (NOX) 2; Hs00166163_m1, another member of the NOx families that produce ROS in immune cells (including PBMCs), was used to evaluate the degree of ROS production in human PBMC samples in this study74. Furthermore, in vitro expression changes of five genes (SOD1, SOD2, GPX1, catalase [CAT], and NOX2) in PBMCs were examined with or without treatments of various concentrations of EtOH for 24–72 h. Expression levels were normalized to those of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), and the relative expression levels were calculated.

Measurement of antioxidant markers in plasma

Whole blood samples were obtained from all 197 students and centrifuged at 1000 g for 10 min. Plasma samples were separated and stored at − 20 °C until analyzed. The plasma levels of six antioxidant-related proteins, Bcl-2/adenovirus E1B 19-kDa protein-interacting protein (BNIP) 3, CC chemokine ligand (CCL) 5, metallothionein (MT) 3, PDZ and LIM domain (PDLIM) 1, SOD1, and titin (TTN), were measured using a commercial ELISA kit, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The plasma levels were determined and validated using commercially available ELISA kits (Table S4).

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using JMP 17 software (SAS Institute Japan, Tokyo, Japan). p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The sample size required for this study was calculated using G*power calculator 3.1.9.7 software (Heinrich-Heine-Universität, Düsseldorf, Germany) (effect size = 0.65, alpha error = 0.05, power = 0.80).75 For in vitro absorbance and fluorescence analyses and mRNA expression determined using TaqMan PCR, data were analyzed using an unpaired Student’s t-test. Nonparametric data were analyzed using Wilcoxon Kruskal–Wallis test. Correlations among alcohol consumption in alcohol drinkers, gene expression, and plasma levels were examined using Spearman’s rank correlation method. Age-related changes in non-drinkers were assessed in the above analyses between adolescents and young adults consuming light alcohol. Data are expressed as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) unless stated otherwise.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We thank Ms. Seiko Shinzawa (Department of Gastroenterology, Graduate School of Medicine, University of Tokyo, Japan) for providing technical assistance. We thank the staff of the Department of Pathology, Graduate School of Medicine, University of Tokyo, for the processing and pathological examination of the specimens. This research was supported by a Health Sciences Research Grant from the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare of Japan (Research on Hepatitis) and a Grant from the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED) under Grant Number JP23fk0210090. No additional external funding was received for the study. The funders played no role in the study design, data collection, analysis, decision to publish, or manuscript preparation.

Author contributions

A.K., K.M., and Y.I. contributed to the study design, data acquisition, data analysis, and interpretation, and manuscript drafting. S.Y., T.T., and K.K. participated in critical revision of the manuscript. M.F. participated in the analysis and interpretation of the data, drafting and critical revision of the manuscript, and supervision. All authors have reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Schrieks, I. C., Joosten, M. M., Klöpping-Ketelaars, W. A., Witkamp, R. F. & Hendriks, H. F. Moderate alcohol consumption after a mental stressor attenuates the endocrine stress response. Alcohol57, 29–34. 10.1016/j.alcohol.2016.10.006 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Louvet, A. & Mathurin, P. Alcoholic liver disease: Mechanisms of injury and targeted treatment. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol.12, 231–242. 10.1038/nrgastro.2015.35 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hoek, J. B., Cahill, A. & Pastorino, J. G. Alcohol and mitochondria: A dysfunctional relationship. Gastroenterology122, 2049–2063. 10.1053/gast.2002.33613 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khair, S. et al. New insights into the mechanism of alcohol-mediated organ damage via its impact on immunity, metabolism, and repair pathways: A summary of the 2021 Alcohol and Immunology Research Interest Group (AIRIG) meeting. Alcohol103, 1–7. 10.1016/j.alcohol.2022.05.004 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Forman, H. J. & Zhang, H. Targeting oxidative stress in disease: Promise and limitations of antioxidant therapy. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov.20, 689–709. 10.1038/s41573-021-00233-1 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tseng, Y. M. et al. Effects of alcohol-induced human peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PBMC) pretreated whey protein concentrate (WPC) on oxidative damage. J. Agric. Food Chem.56, 8141–8147. 10.1021/jf801034k (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.GBD. Alcohol use and burden for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2016: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet392, 1015–1035. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31310-2 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Caprio, G. G. et al. Light alcohol drinking and the risk of cancer development: A controversial relationship. Rev. Recent Clin. Trials15, 164–177. 10.2174/1574887115666200628143015 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zaitsu, M., Takeuchi, T., Kobayashi, Y. & Kawachi, I. Light to moderate amount of lifetime alcohol consumption and risk of cancer in Japan. Cancer126, 1031–1040. 10.1002/cncr.32590 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wood, A. M. et al. Risk thresholds for alcohol consumption: Combined analysis of individual-participant data for 599 912 current drinkers in 83 prospective studies. Lancet391, 1513–1523. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30134-X (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Okubo, R. & Tabuchi, T. Smoking and drinking among patients with mental disorders: Evidence from a nationally representative Japanese survey. J. Affect. Disord.279, 443–450. 10.1016/j.jad.2020.10.037 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kado, A. et al. Noninvasive diagnostic criteria for nonalcoholic steatohepatitis based on gene expression levels in peripheral blood mononuclear cells. J. Gastroenterol.54, 730–741. 10.1007/s00535-019-01565-x (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thangavel, S. et al. Oxidative stress in HIV infection and alcohol use: Role of redox signals in modulation of lipid rafts and ATP-binding cassette transporters. Antioxid. Redox Signal.28, 324–337. 10.1089/ars.2016.6830 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.World Health Organization. Global Status Report on Alcohol and Health 2018 (World Health Organization, 2018).

- 15.Warner, J. B. et al. Analysis of alcohol use, consumption of micronutrient and macronutrients, and liver health in the 2017–2018 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res.46, 2025–2040. 10.1111/acer.14944 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McDonald, H. et al. Comparative performance of biomarkers of alcohol consumption in a population sample of working-aged men in Russia: The Izhevsk Family Study. Addiction108, 1579–1589. 10.1111/add.12251 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martins, F. R. B. et al. Chronic ethanol exposure impairs alveolar leukocyte infiltration during pneumococcal pneumonia, leading to an increased bacterial burden despite increased CXCL1 and nitric oxide levels. Front. Immunol.14, 1175275. 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1175275 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bhattacharyya, A., Chattopadhyay, R., Mitra, S. & Crowe, S. E. Oxidative stress: An essential factor in the pathogenesis of gastrointestinal mucosal diseases. Physiol. Rev.94, 329–354. 10.1152/physrev.00040.2012 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fernández-Regueras, M. et al. Predominantly pro-inflammatory phenotype with mixed M1/M2 polarization of peripheral blood classical monocytes and monocyte-derived macrophages among patients with excessive ethanol intake. Antioxidants (Basel)12, 1708. 10.3390/antiox12091708 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saribal, D., Hocaoglu-Emre, F. S., Karaman, F., Mırsal, H. & Akyolcu, M. C. Trace element levels and oxidant/antioxidant status in patients with alcohol abuse. Biol. Trace Elem. Res.193, 7–13. 10.1007/s12011-019-01681-y (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tsermpini, E. E., Plemenitaš Ilješ, A. & Dolžan, V. Alcohol-induced oxidative stress and the role of antioxidants in alcohol use disorder: A systematic review. Antioxidants (Basel)11, 1374. 10.3390/antiox11071374 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huang, M. C., Chen, C. C., Peng, F. C., Tang, S. H. & Chen, C. H. The correlation between early alcohol withdrawal severity and oxidative stress in patients with alcohol dependence. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry33, 66–69. 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2008.10.009 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Contreras, M. L. et al. NADPH oxidase Isoform 2 (NOX2) is involved in drug addiction vulnerability in progeny developmentally exposed to ethanol. Front. Neurosci.11, 338. 10.3389/fnins.2017.00338 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sommavilla, M. et al. The effects of acute ethanol exposure and ageing on rat brain glutathione metabolism. Free Radic. Res.46, 1076–1081. 10.3109/10715762.2012.688963 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cho, K. et al. Prenatal alcohol exposure and adverse fetal growth restriction: Findings from the Japan Environment and Children’s Study. Pediatr. Res.92, 291–298. 10.1038/s41390-021-01595-3 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nogales, F., Ojeda, M. L., Jotty, K., Murillo, M. L. & Carreras, O. Maternal ethanol consumption reduces Se antioxidant function in placenta and liver of embryos and breastfeeding pups. Life Sci.190, 1–6. 10.1016/j.lfs.2017.09.021 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ruiz-Cortes, K., Villageliu, D. N. & Samuelson, D. R. Innate lymphocytes: Role in alcohol-induced immune dysfunction. Front. Immunol.13, 934617. 10.3389/fimmu.2022.934617 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pasala, S., Barr, T. & Messaoudi, I. Impact of alcohol abuse on the adaptive immune system. Alcohol Res.37, 185–197 (2015). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Curry-McCoy, T. V., Osna, N. A., Nanji, A. A. & Donohue, T. M. Jr. Chronic ethanol consumption results in atypical liver injury in copper/zinc superoxide dismutase deficient mice. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res.34, 251–261. 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2009.01088.x (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fujiwara, N. et al. Oxidative modification to cysteine sulfonic acid of Cys111 in human copper-zinc superoxide dismutase. J. Biol. Chem.282, 35933–35944. 10.1074/jbc.M702941200 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miao, L. & St Clair, D. K. Regulation of superoxide dismutase genes: Implications in disease. Free Radic. Biol. Med.47, 344–356. 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.05.018 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Che, M., Wang, R., Li, X., Wang, H. Y. & Zheng, X. F. S. Expanding roles of superoxide dismutases in cell regulation and cancer. Drug Discov. Today21, 143–149. 10.1016/j.drudis.2015.10.001 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zuo, X. et al. TDP-43 aggregation induced by oxidative stress causes global mitochondrial imbalance in ALS. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol.28, 132–142. 10.1038/s41594-020-00537-7 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mohammed, S. et al. Role of necroptosis in chronic hepatic inflammation and fibrosis in a mouse model of increased oxidative stress. Free Radic. Biol. Med.164, 315–328. 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2020.12.449 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stewart, S. F., Vidali, M., Day, C. P., Albano, E. & Jones, D. E. Oxidative stress as a trigger for cellular immune responses in patients with alcoholic liver disease. Hepatology39, 197–203. 10.1002/hep.20021 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gopal, T. et al. Nanoformulated SOD1 ameliorates the combined NASH and alcohol-associated liver disease partly via regulating CYP2E1 expression in adipose tissue and liver. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol.318, G428–G438. 10.1152/ajpgi.00217.2019 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Trotti, D., Rolfs, A., Danbolt, N. C., Brown, R. H. Jr. & Hediger, M. A. SOD1 mutants linked to amyotrophic lateral sclerosis selectively inactivate a glial glutamate transporter. Nat. Neurosci.2, 427–433. 10.1038/8091 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lu, C. H. et al. Plasma neurofilament heavy chain levels correlate to markers of late stage disease progression and treatment response in SOD1(G93A) mice that model ALS. PLoS ONE7, e40998. 10.1371/journal.pone.0040998 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.D’Ovidio, F. et al. Association between alcohol exposure and the risk of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis in the Euro-MOTOR study. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry90, 11–19. 10.1136/jnnp-2018-318559 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ni, H. M. et al. Role of hypoxia inducing factor-1β in alcohol-induced autophagy, steatosis and liver injury in mice. PLOS ONE9, e115849. 10.1371/journal.pone.0115849 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Merjaneh, M. et al. Pro-angiogenic capacities of microvesicles produced by skin wound myofibroblasts. Angiogenesis20, 385–398. 10.1007/s10456-017-9554-9 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sajjanar, B. et al. Genome-wide expression analysis reveals different heat shock responses in indigenous (Bos indicus) and crossbred (Bos indicus X Bos taurus) cattle. Genes Environ.45, 17. 10.1186/s41021-023-00271-8 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhao, Q. et al. BNIP3-dependent mitophagy safeguards ESC genomic integrity via preventing oxidative stress-induced DNA damage and protecting homologous recombination. Cell Death Dis.13, 976. 10.1038/s41419-022-05413-4 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lee, B. C. & Lee, J. Cellular and molecular players in adipose tissue inflammation in the development of obesity-induced insulin resistance. Biochim. Biophys. Acta1842, 446–462. 10.1016/j.bbadis.2013.05.017 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ambade, A. et al. Pharmacological inhibition of CCR2/5 signalling prevents and reverses alcohol-induced liver damage, steatosis, and inflammation in mice. Hepatology69, 1105–1121. 10.1002/hep.30249 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yeligar, S. M., Machida, K., Tsukamoto, H. & Kalra, V. K. Ethanol augments RANTES/CCL5 expression in rat liver sinusoidal endothelial cells and human endothelial cells via activation of NF-kappa B, HIF-1 alpha, and AP-1. J. Immunol.183, 5964–5976. 10.4049/jimmunol.0901564 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ho, M. H. et al. CCL5 via GPX1 activation protects hippocampal memory function after mild traumatic brain injury. Redox Biol.46, 102067. 10.1016/j.redox.2021.102067 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kambe, T., Tsuji, T., Hashimoto, A. & Itsumura, N. The physiological, biochemical, and molecular roles of zinc transporters in zinc homeostasis and metabolism. Physiol. Rev.95, 749–784. 10.1152/physrev.00035.2014 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bayrak, B. B., Arda-Pirincci, P., Bolkent, S. & Yanardag, R. Zinc prevents ethanol-induced oxidative damage in lingual tissues of rats. Biol. Trace Elem. Res.200, 720–727. 10.1007/s12011-021-02682-6 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jeong, H. G. et al. Metallothionein-III prevents gamma-ray-induced 8-oxoguanine accumulation in normal and hOGG1-depleted cells. J. Biol. Chem.279, 34138–34149. 10.1074/jbc.M402530200 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chowdhury, D. et al. Metallothionein 3-zinc axis suppresses caspase-11 inflammasome activation and impairs antibacterial immunity. Front. Immunol.12, 755961. 10.3389/fimmu.2021.755961 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhou, J. K., Fan, X., Cheng, J., Liu, W. & Peng, Y. PDLIM1: Structure, function and implication in cancer. Cell Stress5, 119–127. 10.15698/cst2021.08.254 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hayashi, G. & Cortopassi, G. Lymphoblast oxidative stress genes as potential biomarkers of disease severity and drug effect in Friedreich’s ataxia. PLoS ONE11, e0153574. 10.1371/journal.pone.0153574 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Herzog, W. The multiple roles of titin in muscle contraction and force production. Biophys. Rev.10, 1187–1199. 10.1007/s12551-017-0395-y (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Toffali, L. et al. An isoform of the giant protein titin is a master regulator of human T lymphocyte trafficking. Cell Rep.42, 112516. 10.1016/j.celrep.2023.112516 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gritsyna, Y. V. et al. Increased autolysis of μ-calpain in skeletal muscles of chronic alcohol-fed rats. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res.41, 1686–1694. 10.1111/acer.13476 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Loescher, C. M. et al. Regulation of titin-based cardiac stiffness by unfolded domain oxidation (UnDOx). Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA117, 24545–24556. 10.1073/pnas.2004900117 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Khouri, R. et al. SOD1 plasma level as a biomarker for therapeutic failure in cutaneous leishmaniasis. J. Infect. Dis.210, 306–310. 10.1093/infdis/jiu087 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Andresen-Streichert, H., Müller, A., Glahn, A., Skopp, G. & Sterneck, M. Alcohol biomarkers in clinical and forensic contexts. Dtsch. Arztebl. Int.115, 309–315. 10.3238/arztebl.2018.0309 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tverdal, A. et al. Alcohol consumption, HDL-cholesterol and incidence of colon and rectal cancer: A prospective cohort study including 250,010 participants. Alcohol56, 718–725. 10.1093/alcalc/agab007 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Knight, Z. G. A proposed model of psychodynamic psychotherapy linked to Erik Erikson’s eight stages of psychosocial development. Clin. Psychol. Psychother.24, 1047–1058. 10.1002/cpp.2066 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Silverberg, J. I. et al. Atopic dermatitis in the pediatric population: A cross-sectional, international epidemiologic study. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol.126, 417-428.e2. 10.1016/j.anai.2020.12.020 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Okui, T. Age-period-cohort analysis of healthy lifestyle behaviors using the National health and nutrition survey in Japan. J. Prev. Med. Public Health53, 409–418. 10.3961/jpmph.20.159 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kado, A. et al. Triglyceride level and soft drink consumption predict nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in nonobese male adolescents. Hepatol. Res.53, 497–510. 10.1111/hepr.13889 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yoshida, K. et al. Association and dose-response relationship between exposure to alcohol advertising media and current drinking: A nationwide cross-sectional study of Japanese adolescents. Environ Health Prev Med.28, 58. 10.1265/ehpm.23-00127 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Fernie, G., Christiansen, P., Cole, J. C., Rose, A. K. & Field, M. Effects of 0.4 g/kg alcohol on attentional bias and alcohol-seeking behaviour in heavy and moderate social drinkers. J. Psychopharmacol.26, 1017–25. 10.1177/0269881111434621 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Duke, A. A., Giancola, P. R., Morris, D. H., Holt, J. C. & Gunn, R. L. Alcohol dose and aggression: Another reason why drinking more is a bad idea. J. Stud. Alcohol. Drugs72, 34–43. 10.15288/jsad.2011.72.34 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kalinowski, A. & Humphreys, K. Governmental standard drink definitions and low-risk alcohol consumption guidelines in 37 countries. Addiction111, 1293–1298. 10.1111/add.13341 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Stelander, L. T. et al. The effects of exceeding low-risk drinking thresholds on self-rated health and all-cause mortality in older adults: The Tromsø study 1994–2020. Arch. Public Health81, 25. 10.1186/s13690-023-01035-0 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kado, A. et al. Noninvasive approach to indicate risk factors of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis overlapping autoimmune hepatitis based on peripheral lymphocyte pattern. J. Gastroenterol.58, 1237–1251. 10.1007/s00535-023-02038-y (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kado, A. et al. Differential peripheral memory T cell subsets sensitively indicate the severity of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatol. Res.54, 525–539. 10.1111/hepr.14009 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Maskell, P. D. & Korb, A. S. Revised equations allowing the estimation of the uncertainty associated with the Total Body Water version of the Widmark equation. J. Forensic Sci.67, 358–362. 10.1111/1556-4029.14859 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Testa, M. P. et al. Screening assay for oxidative stress in a feline astrocyte cell line, G355–5. J. Vis. Exp.G355–5, e2841. 10.3791/2841 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Li, H. M., Huang, Q., Tang, F. & Zhang, T. P. Altered NCF2, NOX2 mRNA expression levels in peripheral blood mononuclear cells of pulmonary tuberculosis patients. Int. J. Gen. Med.14, 9203–9209. 10.2147/IJGM.S339194 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Leveque, C. et al. Oxidative stress response kinetics after 60 minutes at different levels (10% or 15%) of normobaric hypoxia exposure. Int. J. Mol. Sci.24, 10188. 10.3390/ijms241210188 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.