Abstract

Lyssaviruses are unsegmented RNA viruses causing rabies. Their vectors belong to the Carnivora and Chiroptera orders. We studied 36 carnivoran and 17 chiropteran lyssaviruses representing the main genotypes and variants. We compared their genes encoding the surface glycoprotein, which is responsible for receptor recognition and membrane fusion. The glycoprotein is the main protecting antigen and bears virulence determinants. Point mutation is the main force in lyssavirus evolution, as Sawyer's test and phylogenetic analysis showed no evidence of recombination. Tests of neutrality indicated a neutral model of evolution, also supported by globally high ratios of synonymous substitutions (dS) to nonsynonymous substitutions (dN) (>7). Relative-rate tests suggested similar rates of evolution for all lyssavirus lineages. Therefore, the absence of recombination and similar evolutionary rates make phylogeny-based conclusions reliable. Phylogenetic reconstruction strongly supported the hypothesis that host switching occurred in the history of lyssaviruses. Indeed, lyssaviruses evolved in chiropters long before the emergence of carnivoran rabies, very likely following spillovers from bats. Using dated isolates, the average rate of evolution was estimated to be roughly 4.3 × 10−4 dS/site/year. Consequently, the emergence of carnivoran rabies from chiropteran lyssaviruses was determined to have occurred 888 to 1,459 years ago. Glycoprotein segments accumulating more dN than dS were distinctly detected in carnivoran and chiropteran lyssaviruses. They may have contributed to the adaptation of the virus to the two distinct mammal orders. In carnivoran lyssaviruses they overlapped the main antigenic sites, II and III, whereas in chiropteran lyssaviruses they were located in regions of unknown functions.

Emergence of viral diseases is a permanent threat for animal and public health and may happen whenever environmental conditions are propitious. Virus spillover to new hosts may lead to an emerging disease, provided the virus gains a sufficient fitness. RNA viruses (riboviruses and retroviruses) having a polymerase devoid of a proofreading mechanism are the fastest-evolving organisms (15). They produce a diverse viral population, i.e., quasispecies (14), ready to explore new conditions or escape defense systems. This property makes RNA viruses among the most dangerous pathogens. Indeed, RNA viruses cause two of the six leading infectious killers, i.e., AIDS and measles, and are implicated in two others, i.e., acute respiratory infections and diarrheal diseases (21a). Therefore, understanding their evolution and particularly their emergence may help in fighting them.

The Lyssavirus genus belongs to the Rhabdoviridae family of the Mononegavirales order and includes unsegmented RNA viruses causing rabies encephalomyelitis. They are well fitted to vectors belonging mainly to the orders Carnivora and Chiroptera. Seven genotypes (GTs) have so far been delineated within the genus (8, 21). These GTs were divided into two immunopathologically and genetically distinct phylogroups (3). Phylogroup I includes two African GTs: Mokola virus, which has been isolated from shrews and cats, although its reservoir remains unknown, and Lagos bat virus, which has been found mainly in frugivorous bats but also in an insectivorous bat. Phylogroup II has five GTs: Duvenhage virus (Africa), European bat lyssavirus 1 (EBLV-1; Europe), EBLV-2 (Europe), Australian bat lyssavirus (Australia), and the classical Rabies virus (RABV; worldwide). Members of the GTs Duvenhage virus, EBLV-1, and EBLV-2 are exclusively found in insectivorous bats, members of the GT Australian bat lyssavirus are found in both insectivorous and frugivorous bats, and members of the GT RABV are found in carnivores and American bats (insectivorous, frugivorous, and hematophagous) (28). The fact that lyssaviruses are well established in two ecologically distinct mammal orders may very likely be a consequence of successful host switching. Therefore, to phylogenetically investigate the possibility of this host switching during the evolution of the Lyssavirus genus, we assessed the evolutionary forces, rate, and model. We also searched for regions thought to be responsible for host adaptation.

The external viral glycoprotein (G) was appropriate for this study particularly because of its host adaptation potential. The mature G protein (without a signal peptide [SP]) forms a trimer (20) and has an endodomain (ENDO) that interacts with internal proteins (11, 30, 52), a transmembrane (TM) region, and an ectodomain (ECTO) protruding from the viral membrane. The ECTO carries the B- and T-cell antigenic sites (6, 26) and the regions responsible for receptor recognition (27, 48, 50, 51) and membrane fusion (16). It also bears residues important for virulence (9, 12, 33, 34).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Viruses.

Fifty-five isolates studied were of worldwide distribution and collected from various hosts (Table 1). Thirty-six of these isolates circulated in carnivores, 17 circulated in chiropters, and 2 corresponded to Mokola virus, which has an unknown vector. Twelve viruses were previously described (3). Eight sequences were retrieved from GenBank, and the G genes of 35 isolates obtained from collaborative laboratories were studied for the first time. Isolates were taken from either the brain of an infected mouse or the brain of a suckling mouse after limited passages.

TABLE 1.

The 55 isolates studied

| Virus | Country (state) of isolation | Host(s) | Variant host or GTa | Yr(s) of isolation | Original reference | Accession no.b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FRA1-FX | France | Fox | Fox | 1991 | 91047 | AF325461 |

| YUG1-BV | Yugoslavia | Bovine | Wolf | 1984 | 86058 | AF325463 |

| HUN1-HM | Hungary | Human | Fox | 1992 | 92015 | AF325462 |

| POL1-RD | Poland | Raccoon, dog | Raccoon Dog | 1985 | 86018 | AF325464 |

| POL2-HM | Poland | Human | Dog | 1985 | 86017 | AF325465 |

| MOR1-DG | Morocco | Dog | Dog | 1989 | 89017 | AF325468 |

| MOR2-DG | Morocco | Dog | Dog | 1987 | 87012 | AF325467 |

| MOR3-HM | Morocco | Human | Dog | 1990 | 9106 | AF325469 |

| ALG1-DG | Algeria | Dog | Dog | ? | ? | M81058c |

| TUN1-HM | Tunisia | Human | Dog | 1986 | 86076 | AF325466 |

| GAB1-DG | Gabon | Dog | Dog | 1986 | 86098 | AF325470 |

| NGA1-HM | Nigeria | Human | Dog | 1983 | 86070 | AF325479 |

| MAD1-DG | Madagascar | Dog | Dog | 1985 | 86045 | AF325478 |

| MAU1-CL | Mauritania | Camel | Dog | 1986 | 86089 | AF325483 |

| CAM1-UN | Cameroon | Unknown | Dog | 1988 | 88005 | AF325481 |

| IVC1-UN | Ivory Coast | Unknown | Dog | 1986 | 86067 | AF325482 |

| GUI1-DG | Guinea | Dog | Dog | 1986 | 86060 | AF325484 |

| NIG1-DG | Niger | Dog | Dog | 1990 | 90012 | AF325480 |

| SAF1-MG | South Africa | Mongoose | Mongoose | 1987 | NIV378/87 | AF325485 |

| IRN1-HM | Iran | Human | Wolf | 1988 | 88011 | AF325472 |

| CHI1-BK | China | Buck | Dog | 1986 | 86090 | AF325471 |

| CH12-DG | China | Dog | Dog | 1989 | CGX89-1 | L04523c |

| MAL1-HM | Malaysia | Human | Dog | 1985 | 86077 | AF325487 |

| THA1-HM | Thailand | Human | Dog | 1983 | 87038 | AF325488 |

| NEP1-DG | Nepal | Dog | Dog | 1989 | V120 | AF325489 |

| ARC1-PF | Arctic Circle | Polar fox | Polar fox | <1981 | 0–210 | AF325486 |

| ARC2-DG | Arctic Circle | Dog | Polar fox | 1989–1992 | 4690 DG | U03766c |

| CAN3-SK | Canada | Skunk | Polar fox | 1989–1992 | 1578 SK | U11755c |

| USA1-DG | United States (Mont.) | Dog | Skunk | 1981 | 6–543 | AF325476 |

| USA2-SP | United States (Mont.) | Sheep | Skunk | 1981 | 4–267 | AF325475 |

| USA3-SK | United States (Mont.) | Skunk | Skunk | 1981 | 8–317 | AF325473 |

| USA4-SK | United States (Mont.) | Skunk | Skunk | 1981 | 8–364 | AF325474 |

| USA7-BT | United States (Mont.) | Bat (Myotis) | Lasiuris | 1979 | Bat 1 | AF298141d |

| USA8-BT | United States (Mont.) | Bat (Myotis) | Myotis | 1981 | Bat 20 | AF325494 |

| USA9-BT | United States (Mont.) | Bat (Myotis) | Myotis | 1982 | Bat 32 | AF325495 |

| USA10-BT | United States (Calif.) | Human | Lasionycteris | 1994 | SHBRV | U52946c |

| USA11-CO | United States (Tex.) | Coyote | Coyote | 1993 | COSRV | U52947c |

| USA12-RC | United States (Fla.) | Raccoon | Raccoon | ? | FLA 125 | U27216c |

| USA13-RC | United States (N.Y.) | Raccoon | Raccoon | ? | NY 516 | U27214c |

| MEX1-DG | Mexico | Dog | Dog | 1991 | 91026 | AF325477 |

| MEX2-BT | Mexico | Bat (Desmodus) | Desmodus | 1987 | 87023 | AF325492 |

| BRA2-BV | Brazil | Bovine | Desmodus | 1986 | 86115 | AF325491 |

| ARG1-BT | Argentina | Bat | Bat | 1991 | 91030 | AF325493 |

| GUY1-BV | French Guyana | Bovine | Desmodus | 1985 | 8640 | AF325490 |

| ABL-AUS | Australia | Bat | GT7 | 1997 | ABL | AF006497c |

| EBL1-POL | Poland | Bat | GT5 | 1985 | 8615POL | AF298142d |

| EBL1-FRA | France | Bat | GT5 | 1989 | 8918FRA | AF298143d |

| EBL2-FIN | Finland | Bat | GT6 | 1986 | 9007FIN | AF298144d |

| EBL2-HOL | Holland | Bat | GT6 | 1986 | 9018HOL | AF298145d |

| Duv1-SAF | South Africa | Bat | GT4 | 1970 | 86132SA | AF298146d |

| Duv2-SAF | South Africa | Bat | GT4 | 1981 | 9020SA | AF298147d |

| Lag-NGA | Nigeria | Bat | GT2 | 1956 | 8619NGA | AF298148d |

| Lag-CAR | Central Africa Republic | Bat | GT2 | 1974 | 8620CAR | AF298149d |

| Mok-ZIM | Zimbabwe | Cat | GT3 | 1981 | ? | S59447c |

| Mok-ETH | Ethiopia | Cat | GT3 | 1990 | Eth-16 | U17064c |

The variant and the GT are indicated for the 44 RABV and the 11 RABV-related isolates, respectively.

Accession numbers were created by this study unless otherwise indicated.

Sequence retrieved from GenBank.

Described in the work of Badrane et al. (3).

Sequencing.

RNA extraction from tissue, cDNA synthesis, reverse transcription-PCR amplification, and sequencing were done as described by Sacramento et al. (38). Sequences were obtained from both strands and were carefully verified. Only positive-strand primers were used for cDNA synthesis of the negative-strand viral genome, and consensus sequences were determined without subsequent cloning. This procedure avoided the influence of quasispecies variability on the observed genetic polymorphism. G gene sequencing used 23 primers dispersed between positions 2901 and 5543 of the Pasteur virus strain (PV) genome (49).

Sequence analyses.

Sequences were aligned using CLUSTAL W (47), and phylogenetic analyses were done using the PHYLIP phylogeny inference package software (version 3.52c; J. Felsenstein, University of Washington, Seattle [http://evolution.genetics.washington.edu/phylip.html]) or CLUSTAL W. Sawyer's test was used to look for evidence of recombination (40). For each pair of sequences, the test detects silent polymorphic (or informative) sites and calculates values of four parameters: the sum of the squares of the lengths of condensed fragments [SSCF], the sum of the squares of the lengths of uncondensed fragments [SSUF], the observed maximum length of a condensed fragment [MCF], and the observed maximum length of an uncondensed fragment [MUF]. The length of the condensed fragment or uncondensed fragment is the number (whole-sequence alignment) of silent polymorphic sites or of all sites, respectively, between two adjacent polymorphic sites (pair of sequences). To obtain simulated values for the four parameters, the test does 10,000 random permutations of silent polymorphic sites by respecting their class of degeneracy. The probability of a simulated value being larger than the observed value is estimated, and when the probability is less than 0.05 (or 0.01), recombination is evidenced.

The DnaSP program was used for the Hudson-Kreitman-Aguadé (HKA) (22), Tajima (45), and Fu and Li (19) neutrality tests (37). The HKA test compares the observed polymorphism with that expected by the neutral theory of molecular evolution (24), in which similar levels of polymorphism must be seen between and within species. Tajima's test compares two estimates of nucleotide diversity: the mutation parameter (θ) and the difference between pairs of isolates (π). Fu and Li's test is related to Tajima's and compares the number of singletons to that expected by the neutral theory and can be performed with an outgroup.

Relative-rate tests were done using the K2WuLi (54) and RRTree (36) programs. The first determines the nucleotide distance (all substitutions or only transversions) of an outgroup from two sequences of the tested lineages. The RRTree program performs similarly but accepts amino acid sequences and allows several lineages to be tested. It offers a larger choice of methods to estimate distance and can be weighted with a tree.

The rate of evolution was estimated for each pair of isolates that were within the same (or close) lineage(s) and had been isolated within at least 5 years of each other. The outgroup closest to the lineage was used to estimate the distance by using the dS (32). The evolutionary rate was estimated by dividing the difference between the distances of the two members of the pair by the difference in their years of isolation.

WINA was used to estimate along the G gene the proportions of synonymous substitions (dS) and nonsynonymous substitutions (dN) according to the method of Nei and Gojobori (32). The program detects regional differences in accumulations of ds and dn (17). Four levels of significance can be obtained (decreasing order): dN > 2dS and dN > 1, dN > 2dS and dN ≤ 1, dN> dS and dN > 1, and dN > dS and dN ≤ 1.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

GenBank accession numbers of the G genes of isolates sequenced for this study are noted in Table 1.

RESULTS

Glycoprotein diversity.

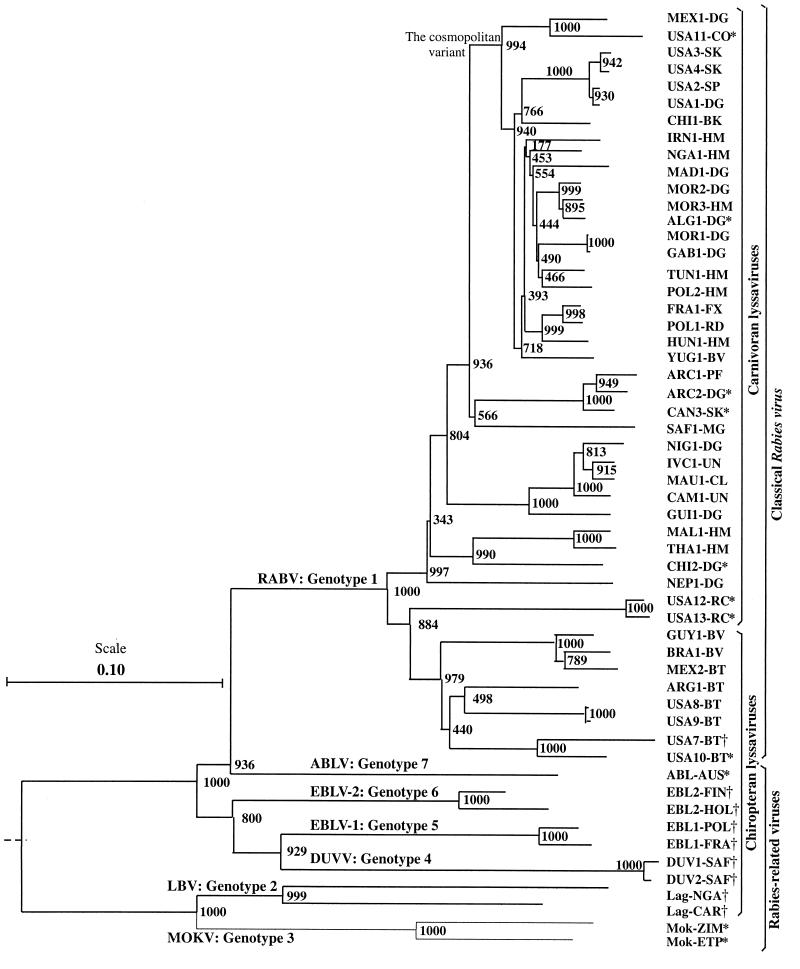

In order to analyze the driving forces in Lyssavirus evolution, the G genes of 55 isolates of the main variants and GTs (Table 1) were compared. Twenty isolates were sequenced previously (3) or retrieved from GenBank. Thirty-five isolates were sequenced from the G mRNA start signal to the downstream L mRNA start signal (approximately 2,100 nucleotides). Thus, 44 isolates corresponded to the RABV and 11 were RABV-related viruses (GT2 to -7). The ECTO is the most conserved part of the G protein, showing at least 61% amino acid identity. In particular, all cysteines are conserved among all lyssaviruses, as is the glycosylation site N319. By contrast, the other parts have identities as low as 20.5% (SP plus TM) and 24% (ENDO). The G gene 3′ noncoding region (Ψ) shows significant similarities within, but not between, GTs. All these data outline the importance of the structural and functional constraints on the ECTO in contrast to other parts of the G gene and the considerable genetic diversity of lyssaviruses. A neighbor-joining tree showed that the seven GTs are clearly distinct, and several lineages can be distinguished within GT1 (Fig. 1). Among the 44 RABV isolates, 22 illustrate the cosmopolitan variant that was probably caused by human activity through dog importation (25, 42). This lineage probably originated from the Palearctic region (Europe, Middle East, and North Africa), where it remains almost exclusive to some vectors (dog, red fox, raccoon dog, and wolf). It has been spread worldwide and is maintained mainly in dogs (Africa, Asia, and Latin America) but has also been adapted to wildlife vectors (skunk, gray fox, and coyote in North America). Out of the Palearctic region, the cosmopolitan variant coexists with autochthonous variants present before its importation. At least one autochthonous variant has spread in the Arctic region (arctic and red foxes), two have spread in sub-Saharan Africa (dog and mongoose), three have spread in Asia (dog), and several have spread in the Americas by means of both carnivores (skunk and raccoon) and chiropters (insectivorous, frugivorous, and hematophagous bats). In the last group, the variants are specific for the bat species (31, 41). It is obvious from the phylogenetic tree that carnivoran and chiropteran lyssaviruses are branching apart.

FIG. 1.

Lyssavirus-rooted phylogenetic tree. The tree was estimated using the neighbor-joining method (39) on the basis of the ECTO nucleotide sequence. Bootstrap values of 1,000 replicates indicate the robustness of the corresponding node. The sequences retrieved from GenBank and those described in the work of Badrane et al. (3) are marked with * and †, respectively. RABV, Rabies virus; EBLV-1, European bat lyssavirus 1; EBLV-2, European bat lyssavirus 2; ABLV, Australian bat lyssavirus; DUVV, Duvenhage virus; LBV, Lagos bat virus; MOKV, Mokola virus.

Evolutionary forces and model.

We tested to see if recombination has played a significant role in Lyssavirus evolution. Seventeen isolates have available sequences of their G (this paper) and the nucleoprotein (N) (7) genes. We generated a bootstrapped neighbor-joining tree from each of the two genomic regions separated by almost 2.5 kb. Both trees exhibited very similar topologies with significant bootstrap values (data not shown). In addition, very similar trees were obtained with the N (8) and the G (3) genes in lyssaviruses. Using a different strategy, recombination was further assessed by Sawyer's test. We validated the test with a sample of 10 sequences in which few recombination events were artificially introduced. As shown in Table 2, recombination was clearly evidenced in this sample for both polymorphic and informative sites since the probabilities of obtaining larger values for the simulated parameters were equal to zero. With the genuine sequences (no artificial recombination), the probabilities were greater than 11%. The whole of 44 RABV G sequences were tested, and once again the probabilities were high (>10%). All these data provided no evidence of recombination.

TABLE 2.

Probabilities of Sawyer's test for recombination

| Parameter |

P value fora:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 genuine sequences

|

44 genuine sequences

|

|||

| Polymorphic | Informative | Polymorphic | Informative | |

| SSCF | 0.6222 | 0.3196 | 0.5085 | 0.5293 |

| MCF | 0.1117 | 0.4553 | 0.8215 | 0.8363 |

| SSUF | 0.4303 | 0.2680 | 0.1549 | 0.1019 |

| MUF | 0.1452 | 0.5842 | 0.6930 | 0.7066 |

The P values for 10 artificially recombined sequences were equal to 0.0000 for both polymorphic and informative sites.

Tajima's and Fu and Li's neutrality tests were applied to all sequences from carnivoran and chiropteran lyssaviruses using polymorphic sites or only segregating sites. Neither test rejected the neutral model of molecular evolution. Moreover, the Fu and Li and HKA tests were performed separately on each of the chiropteran and carnivoran set of sequences by taking one sequence from the other group as an outgroup. Similarly, neither test rejected the neutral model (data not shown). These results imply a neutral model in Lyssavirus evolution.

Evolutionary rate.

K2WuLi and RRTree programs were used for relative-rate tests. In K2WuLi, a G gene nucleotide alignment of representative lyssavirus lineages (9 from chiropters and 10 from carnivores) was used, with Mokola virus as an outgroup and excluding Lagos bat virus (too close to the outgroup). Ninety pairwise relative-rate tests were performed using all substitutions or the transversions alone (Table 3). Only four comparisons (2.2%) were significant and concerned two chiropteran GT1 lineages (one from Argentina and one from the United States), which have evolved slightly more slowly than two carnivoran GT1 lineages (French fox and sub-Saharan African dog). Using amino acid sequence, RRTree performed a relative-rate test either weighted or not weighted with a phylogenetic tree and used Chandipura virus (Vesiculovirus genus) as an outgroup. The test also resulted in nonsignificant differences (data not shown), thus supporting similar rates in all lineages of lyssaviruses.

TABLE 3.

Frequencies of Z-score intervals from 90 K2WULI relative-rate tests

| Z-score interval | Frequency for:

|

|

|---|---|---|

| All substitutions | Transversions | |

| 0.00–0.50 | 35 | 18 |

| 0.50–1.00 | 29 | 33 |

| 1.00–1.50 | 15 | 30 |

| 1.50–1.96 | 8 | 8 |

| 1.96–2.58 | 2a | 1a |

| >2.58 | 1b | 0 |

0.01 < P < 0.05.

P < 0.01.

The evolutionary rate was estimated for six selected pairs of close isolates spanning the whole Lyssavirus genus. The dS rate was estimated to be 3.1 × 10−4 to 5.5 × 10−4/site/year (Table 4). Accordingly, a molecular-clock tree (PHYLIP phylogeny inference package) using corrected distances (23) estimated that the most recent ancestor of the cosmopolitan variant existed 284 to 504 years ago. A dN rate of 1.4 × 10−5 to 2.3 × 10−5/site/year was deduced from the rate of dS. It allowed us to time distant divergences in which dS were saturated.

TABLE 4.

Evolutionary rate of dS in the Lyssavirus G gene

| Isolates compared | Closest outgroup | No. of yrs between isolations | Difference in dS | Rate range (10−4/site/yr) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lag-CAR, Lag-NGA | Mok-ETH | 18 | 0.0059 | 2.8–3.8 |

| USA8-BT, USA10-BT | GUY1-BV | 13 | 0.0043 | 2.6–4.0 |

| USA9-BT, USA10-BT | GUY1-BV | 12 | 0.0017 | 1.0–1.8 |

| Duv1-SAF, Duv2-SAF | EBL1-POL | 10 | 0.0020 | 1.6–2.4 |

| YUG1-BV, HUN1-HM | CHI1-BK | 8 | 0.0077 | 6.5–12.5 |

| THAI1-HM, NEP1-DG | USA12-RD | 6 | 0.0041 | 4.7–8.7 |

| Avg | 3.1–5.5 |

dN and dS analysis.

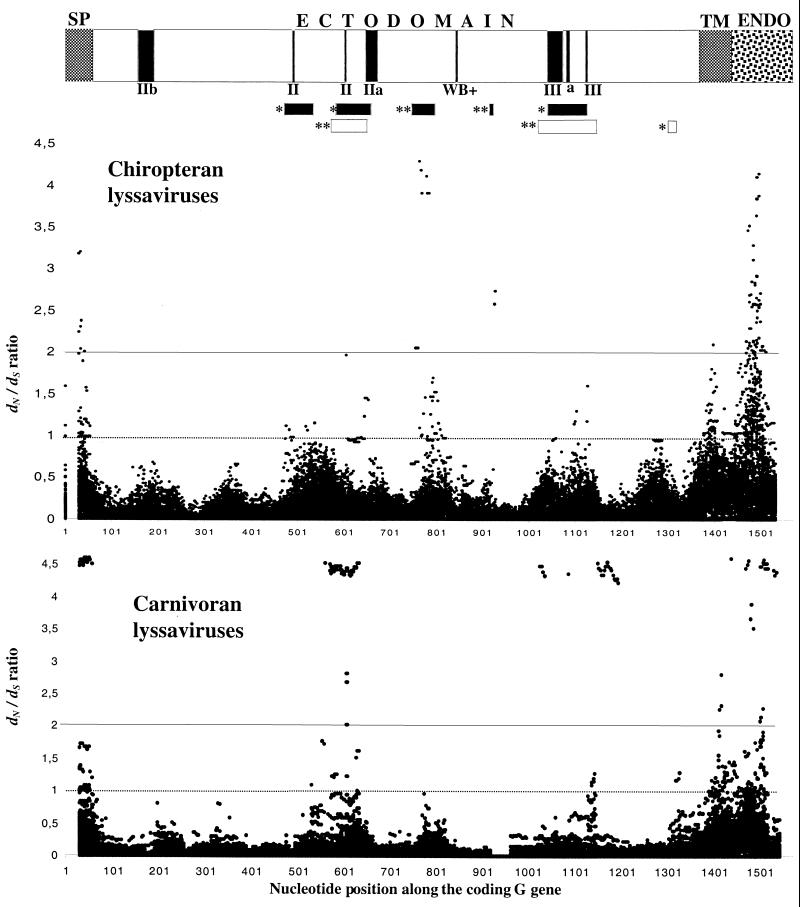

Although the dS/dN rates are globally high (>7), a delicate analysis of dS and dN was done along the G coding region (1,573 nucleotides). The WINA program estimated dS and dN in pairs of sequences from carnivoran or chiropteran lyssaviruses, and the dN/dS ratio was plotted (Fig. 2). Several segments were identified as having a greater dN than dS. The SP, TM, and ENDO parts were among these segments, as expected from their relatively weak constraints. However, in the ECTO, where the constraints are stronger, two segments with high significance (dN > 2dS and dN ≤ 1) were distinctively detected in carnivoran lyssaviruses (G residues 159 to 193 and 326 to 370; nucleotide positions 475 to 577 and 976 to 1,108, respectively) and chiropteran lyssaviruses (G residues 240 to 255 and 275 to 282; nucleotide positions 718 to 763 and 823 to 844, respectively). Interestingly, in carnivoran lyssaviruses they overlap the two major antigenic sites, II and III (6). In contrast, in chiropteran lyssaviruses the two segments are located around the Western blot-positive epitope in regions of unknown functions. Other segments with lower significance (dN> dS and dN ≤ 1) were found. In chiropteran lyssaviruses three segments (residues 139 to 160, 180 to 200, and 332 to 357; nucleotide positions 415 to 478, 538 to 598, and 994 to 1069, respectively) also overlap the main antigenic sites, II and III, while in carnivoran lyssaviruses one segment (residues 420 to 427; nucleotide positions 1,258 to 1,279) is in the C terminus. These peptides under positive selection are thought to bear host adaptation sites.

FIG. 2.

Ratios of dN to dS along the G gene coding region. We plotted the dS/dN ratio for each pairwise comparison (17) of chiropteran (top graph) and carnivoran (bottom graph) lyssaviruses along their G gene coding regions. Threshold lines of the significance of the ratios are shown at values 1 and 2. A schematic representation of the G gene shows the different domains, SP, TM, ENDO, and ECTO, where antigenic sites are indicated with vertical black boxes. Horizontal black or open boxes represent regions of the chiropteran or carnivoran lyssavirus G gene, respectively, which accumulate significantly more dN than dS. *, dN > dS and dN ≤ 1; **, dN > 2dS and dN ≤ 1.

DISCUSSION

Among the 3,400 taxonomic viral species reported in the virus taxonomy book (30a), 54% are RNA viruses and 43% are DNA viruses. It is noteworthy that, among human viruses, 141 species are RNA viruses while only 32 are DNA viruses (H. Badrane, personal analysis). Of the 42 emerging or reemerging infectious diseases between 1996 and 2000 (21a), 23 (55%) were caused by RNA viruses, showing to what extent they threaten the public health. Understanding the evolution of viruses can be a major step in fighting and controlling viral diseases. We studied lyssavirus evolution by analyzing sequences from the external G protein, a main factor in virus-host interactions. We first assessed the importance of evolutionary forces (point mutations and recombination) and model. We did a phylogenetic analysis to examine the possibility of successful host switching of lyssaviruses from chiropters to carnivores. We also estimated the rate of evolution and analyzed the dN/dS ratio along the G gene to search for putative host adaptation segments.

G sequences were obtained from 35 isolates, and 20 additional sequences were analyzed previously (3) or retrieved from GenBank. So far, our panel of isolates represents the most complete picture of lyssaviruses diversity. Sequence analysis indicated that the Ψ noncoding region is hypervariable, although its maintenance at similar sizes (450 to 514 nucleotides) in all lyssaviruses studied is surprising. This may be explained by the role of noncoding regions in the regulation of transcription of lyssaviruses (18). G proteins exhibited great diversity among lyssaviruses, having as little as 54% amino acid identity. Our data clearly show that point mutation and purifying selection are the major forces in lyssavirus evolution. Phylogenetic analysis of Lyssavirus isolates produced very similar trees on genomic regions separated by 2.5 kb. Moreover, Sawyer's test randomly produced parameters (SSCF, MCF, SSUF, and MUF) with larger values than the observed values (P > 0.1). Hence, both analyses suggest no evidence of recombination in Lyssavirus evolution. Although recombination has been described for some DNA and RNA viruses (1), Pringle suggested no recombination for the whole order Mononegavirales (35). Different constraints may prevent recombination (53). The viability of recombined genomes (4) and the replication in the same cell do not seem restrictive. However, the most-limiting processes leading to recombination may be a rare coinfection with very distinct lyssaviruses and/or the constant association of the N protein with the viral genome (35).

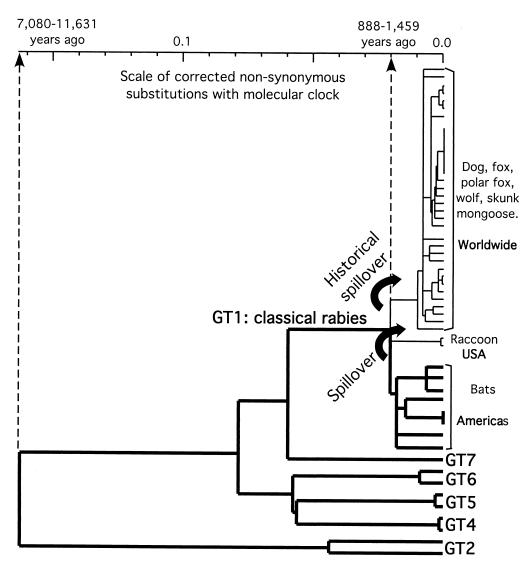

As lyssaviruses do not recombine significantly and evolve at similar rates, the tree in Fig. 1 should provide a good estimate of their true phylogeny. It strongly indicates that chiropteran lyssaviruses existed long before carnivoran RABV (Fig. 3), and that successful host switching from chiropters to carnivores has occurred in the history of Lyssavirus. Spillovers of lyssaviruses from bats to carnivores are not unusual, and contemporaneous episodes have been described (10, 29). The phylogeny of lyssaviruses implies at least two ancient spillover events, both within the GT1. One spillover that is predicted to have occurred in North America produced the raccoon RABV lineage (eastern United States) and possibly the closely related skunk lineage (central United States), as was suggested by partial G gene sequencing (data not included). However, a second spillover in an unknown region spread the RABV worldwide in a variety of carnivores from an unknown vector. It produced an RABV responsible for 32,000 human deaths per year (52a), constituting a historical spillover, and made rabies a public health problem. Spillovers of lyssaviruses from chiropters to other animals, mainly carnivores, may have occurred repeatedly in history and still occur (10). However, it is not known why only rare spillovers have succeeded in being maintained through time or why others have been extinguished. The present work give strong evidence that what is today known as carnivoran rabies is indeed a result of a few successful episodes of host switching from bats.

FIG. 3.

Lyssavirus phylogenetic tree with a molecular clock (PHYLIP phylogeny inference package) derived from nonsynonymous corrected distances (23). Six of the seven Lyssavirus GTs are represented (except GT3). Bold branches distinguish chiropteran Lyssavirus lineages. The geographic locations and vectors of RABV main lineages are indicated. Curved arrows symbolize the two spillover events. Timing estimations of spillovers and of the most recent Lyssavirus ancestor are indicated on the scale.

The rate of Lyssavirus evolution was roughly estimated to be 3.1 × 10−4 to 5.5 × 10−4 dS/site/year. This rate date the divergence of the cosmopolitan variant to 284 to 504 years ago, which is in agreement with the intense human movements of the last five centuries. dS are generally neutral and more sensitive to evolutionary time than dN. However, they saturate faster over long periods of evolution. Therefore, to evaluate older divergences, the rate of dN was used. It was deduced from that of dS to an average of 1.85 × 10−5/site/year. This rate seems low compared to that for Human immunodeficiency virus or Human influenza A virus but similar to that estimated for the G gene of Ebola virus (3.6 × 10−5 substitutions/site/year), another member of the Mononegavirales (44). The lower rate of molecular evolution in some RNA viruses might be due to a higher fidelity of their polymerase or a lower degree of viral multiplication. A phylogenetic tree was constructed with nonsynonymous corrected distances (23) by assuming a molecular clock (PHYLIP phylogeny inference package) (Fig. 3). It dated the host switching of the RABV from chiropters to carnivores to 888 to 1,459 years ago. This estimation seems questionable, as carnivoran rabies was described back in Mesopotamian civilizations about 4,000 years ago (46). Nevertheless, the type of Lyssavirus responsible for Mesopotamian rabies is unknown, and it is admitted that RABV lineages may be extinct because of historical or environmental events or of the fatality of the disease. Timing the emergence of carnivoran rabies to 4,000 years ago makes the evolution of lyssaviruses extremely slow (4.1 × 10−6 to 6.7 × 10−6 dN /site/year). Hence, the extinction of the Mesopotamian Lyssavirus is the most likely hypothesis, as the neutral model of evolution implies a random genetic drift, which may lead to extinction and loss of polymorphism (24).

Because lyssaviruses migrate from the peripheral to the central nervous systems, they hide from and avoid the immunity of the host. Therefore, it is not surprising that their G genes are globally not subject to selection pressure, as suggested by the neutrality tests. Nevertheless, positive selection may be detected regionally (17) or even at single amino acid sites (43). Hence, several G segments accumulating more dN than dS were distinctively detected in carnivoran and chiropteran lyssaviruses. The conformational main antigenic sites bearing several residues linked to virulence (9, 34) are the putative sites for host adaptation (not including immune system escape), particularly in carnivores and to a lesser extent in chiropters. In addition, two distinct segments of unknown functions are putative sites for adaptation specifically to chiropters.

Insectivorous bats are possible vectors for six Lyssavirus GTs and are exclusive to three. It can be speculated that lyssaviruses originated from an insect rhabdovirus, which insectivorous bats contracted from insects. Several arguments are in favor of this speculation. Most of the other Rhabdoviridae genera, except Novirhabdovirus, have isolates from insects. Strikingly, three unclassified viruses proposed to belong to the Lyssavirus genus have been isolated so far only from insects, i.e., the kotonkan, Obodhiang (5), and Rochambeau (13) viruses. Moreover, Mokola virus, which was also isolated from an insectivorous animal (shrew), was demonstrated to replicate in inoculated Aedes aegypti mosquitoes (2). If this contraction of an insect rhabdovirus by bats really resulted in the emergence of lyssaviruses, it can be timed to the most recent common ancestor of lyssaviruses, about 7,080 to 11,631 years ago (Fig. 3).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We deeply thank the following worldwide collaborators, who provided viral samples: D. Briggs (Kansas State University), D. Lodmell (Rocky Mountain Laboratories, Hamilton, Mont.), A. Fayaz (IPI, Teheran, Iran), B. Swanepoel (NIV, Johannesburg, South Africa), and H. Bourhy (IP, Paris, France). We are grateful to two anonymous reviewers, whose constructive criticism and suggestions improved the manuscript.

H.B. was the recipient of fellowships from the Moroccan Government and French-Moroccan cooperation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aaziz R, Tepfer M. Recombination in RNA viruses and in virus-resistant transgenic plants. J Gen Virol. 1999;80:1339–1346. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-80-6-1339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aitken T H, Kowalski R W, Beaty B J, Buckley S M, Wright J D, Shope R E, Miller B R. Arthropod studies with rabies-related Mokola virus. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1984;33:945–952. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1984.33.945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Badrane H, Bahloul C, Perrin P, Tordo N. Evidence of two Lyssavirus phylogroups with distinct pathogenicity and immunogenicity. J Virol. 2001;75:3268–3276. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.7.3268-3276.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ball L A, Pringle C R, Flanagan B, Perepelitsa V P, Wertz G W. Phenotypic consequences of rearranging the P, M, and G genes of vesicular stomatitis virus. J Virol. 1999;73:4705–4712. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.6.4705-4712.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bauer S P, Murphy F A. Relationship of two arthropod-borne rhabdoviruses (kotonkan and Obodhiang) to the rabies serogroup. Infect Immun. 1975;12:1157–1172. doi: 10.1128/iai.12.5.1157-1172.1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Benmansour A, Leblois H, Coulon P, Tuffereau C, Gaudin Y, Flamand A, Lafay F. Antigenicity of rabies virus glycoprotein. J Virol. 1991;65:4198–4203. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.8.4198-4203.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bourhy H, Kissi B, Audry L, Smreczak M, Sadkowska-Todys M, Kulonen K, Tordo N, Zmudzinski J F, Holmes E C. Ecology and evolution of rabies virus in Europe. J Gen Virol. 1999;80:2545–2557. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-80-10-2545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bourhy H, Kissi B, Tordo N. Molecular diversity of the Lyssavirus genus. Virology. 1993;194:70–81. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coulon P, Ternaux J P, Flamand A, Tuffereau C. An avirulent mutant of rabies virus is unable to infect motoneurons in vivo and in vitro. J Virol. 1998;72:273–278. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.1.273-278.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crawford-Miksza L K, Wadford D A, Schnurr D P. Molecular epidemiology of enzootic rabies in California. J Clin Virol. 1999;14:207–219. doi: 10.1016/s1386-6532(99)00054-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Delagneau J F, Perrin P, Atanasiu P. Structure of rabies virus: spatial relationships of the proteins G, M1, M2 and N. Ann Virol (Paris) 1981;132E:473–493. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dietzschold B, Wunner W H, Wiktor T J, Lopes A D, Lafon M, Smith C L, Koprowski H. Characterization of an antigenic determinant of the glycoprotein that correlates with pathogenicity of rabies virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1983;80:70–74. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.1.70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Digoutte J P. Rapport Annuel de l'Institut Pasteur de la Guyane Francaise, 31–32. French Guiana: Institute Pasteur; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Domingo E, Baranowski E, Ruiz-Jarabo C M, Martin-Hernandez A M, Saiz J C, Escarmis C. Quasispecies structure and persistence of RNA viruses. Emerg Infect Dis. 1998;4:521–527. doi: 10.3201/eid0404.980402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Drake J W, Charlesworth B, Charlesworth D, Crow J F. Rates of spontaneous mutation. Genetics. 1998;148:1667–1686. doi: 10.1093/genetics/148.4.1667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Durrer P, Gaudin Y, Ruigrok R W H, Graf R, Brunner J. Photolabeling identifies a putative fusion domain in the envelope glycoprotein of rabies and vesicular stomatitis virus. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:17575–17581. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.29.17575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Endo T, Ikeo K, Gojobori T. Large-scale search for genes on which positive selection may operate. Mol Biol Evol. 1996;13:685–690. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a025629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Finke S, Cox J H, Conzelmann K K. Differential transcription attenuation of rabies virus genes by intergenic regions: generation of recombinant viruses overexpressing the polymerase gene. J Virol. 2000;74:7261–7269. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.16.7261-7269.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fu Y X, Li W H. Statistical tests of neutrality of mutations. Genetics. 1993;133:693–709. doi: 10.1093/genetics/133.3.693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gaudin Y, Ruigrok R W H, Tuffereau C, Knossow M, Flamand A. Rabies virus glycoprotein is a trimer. Virology. 1992;187:627–632. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(92)90465-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gould A R, Hyatt A D, Lunt R, Kattenbelt J A, Hengstberger S, Blacksell S D. Characterisation of a novel lyssavirus isolated from Pteropid bats in Australia. Virus Res. 1998;54:165–187. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1702(98)00025-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21a.Heymann D L. The urgency of a massive effort against infectious diseases. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hudson R R, Kreitman M, Aguade M. A test of neutral molecular evolution based on nucleotide data. Genetics. 1987;116:153–159. doi: 10.1093/genetics/116.1.153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jukes T H, Cantor C R. Evolution of protein molecules. In: Munro I H N, editor. Mammalian protein metabolism. New York, N.Y: Academic Press; 1969. pp. 21–132. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kimura M. The neutral theory of molecular evolution. Cambridge, Mass: Cambridge University Press; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kissi B, Tordo N, Bourhy H. Genetic polymorphism in the rabies virus nucleoprotein gene. Virology. 1995;209:526–537. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lafay F, Benmansour A, Chebli K, Flamand A. Immunodominant epitopes defined by a yeast-expressed library of random fragments of the rabies virus glycoprotein map outside major antigenic sites. J Gen Virol. 1996;77:339–346. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-77-2-339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lentz T L, Wilson P T, Hawrot E, Speicher D W. Amino acid sequence similarity between rabies virus glycoprotein and snake venom curaremimetic neurotoxins. Science. 1984;226:847–848. doi: 10.1126/science.6494916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McColl K A, Tordo N, Aguilar Setien A. Bat Lyssavirus infections. Rev Sci Tech Off Int Epizoot. 2000;19:177–196. doi: 10.20506/rst.19.1.1221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mebatsion T, Cox J H, Frost J W. Isolation and characterization of 115 street rabies virus isolates from Ethiopia by using monoclonal antibodies: identification of 2 isolates as Mokola and Lagos bat viruses. J Infect Dis. 1992;166:972–977. doi: 10.1093/infdis/166.5.972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mebatsion T, Weiland F, Conzelmann K K. Matrix protein of rabies virus is responsible for the assembly and budding of bullet-shaped particles and interacts with the transmembrane spike glycoprotein G. J Virol. 1999;73:242–250. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.1.242-250.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30a.Murphy F A, Fauquet C M, Bishop D H L, Ghabrial S A, Jarvis A W, Martelli G P, Mayo M A, Summers M D, editors. Sixth report of the International Committee on the Taxonomy of Viruses. New York, N.Y: Springer-Verlag; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nadin-Davis S A, Huang W, Armstrong J, Casey G A, Bahloul C, Tordo N, Wandeler A I. Antigenic and genetic divergence of rabies from bat species indigenous to Canada. Virus Res. 2001;74:139–156. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1702(00)00259-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nei M, Gojobori T. Simple methods for estimating the numbers of synonymous and nonsynonymous nucleotide substitutions. Mol Biol Evol. 1986;3:418–426. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Préhaud C, Coulon P, Diallo A, Martinet-Edelist C, Flamand A. Characterization of a new temperature-sensitive and avirulent mutant of the rabies virus. J Gen Virol. 1989;70:133–143. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-70-1-133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Préhaud C, Coulon P, Lafay F, Thiers C, Flamand A. Antigenic site II of the rabies virus glycoprotein: structure and role in viral virulence. J Virol. 1988;62:1–7. doi: 10.1128/jvi.62.1.1-7.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pringle C R. The genetics of paramyxoviruses. In: Kingsbury D, editor. The paramyxoviruses. New York, N.Y: Plenum Press; 1991. pp. 1–39. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Robinson-Rechavi M, Huchon D. RRTree: relative-rate tests between groups of sequences on a phylogenetic tree. Bioinformatics. 2000;16:296–297. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/16.3.296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rozas J, Rozas R. DnaSP version 3: an integrated program for molecular population genetics and molecular evolution analysis. Bioinformatics. 1999;15:174–175. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/15.2.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sacramento D, Bourhy H, Tordo N. PCR technique as an alternative method for diagnosis and molecular epidemiology of rabies virus. Mol Cell Probes. 1991;6:229–240. doi: 10.1016/0890-8508(91)90045-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Saitou N, Nei M. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol Biol Evol. 1987;4:406–425. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sawyer S. Statistical tests for detecting gene conversion. Mol Biol Evol. 1989;6:526–538. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Smith J S. New aspects of rabies with emphasis on epidemiology, diagnosis, and prevention of the disease in the United States. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1996;9:166–176. doi: 10.1128/cmr.9.2.166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Smith J S, Orciari L A, Yager P A, Seidel H D, Warner C K. Epidemiologic and historical relationships among 97 rabies virus isolates as determined by limited sequence analysis. J Infect Dis. 1992;166:296–307. doi: 10.1093/infdis/166.2.296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Suzuki Y, Gojobori T. A method for detecting positive selection at single amino acid sites. Mol Biol Evol. 1999;16:1315–1328. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Suzuki Y, Gojobori T. The origin and evolution of Ebola and Marburg viruses. Mol Biol Evol. 1997;14:800–806. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a025820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tajima F. Statistical method for testing the neutral mutation hypothesis by DNA polymorphism. Genetics. 1989;123:585–595. doi: 10.1093/genetics/123.3.585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Théodoridès J. Histoire de la rage. Paris, France: Masson; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Thompson J D, Higgins D G, Gibson T J. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Thoulouze M I, Lafage M, Schachner M, Hartmann U, Cremer H, Lafon M. The neural cell adhesion molecule is a receptor for rabies virus. J Virol. 1998;72:7181–7190. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.9.7181-7190.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tordo N, Poch O, Ermine A, Keith G, Rougeon F. Walking along the rabies genome: is the large G-L intergenic region a remnant gene? Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:3914–3918. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.11.3914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tuffereau C, Bénéjean J, Blondel D, Kieffer B, Flamand A. Low-affinity nerve-growth factor receptor (P75NTR) can serve as a receptor for rabies virus. EMBO J. 1998;17:7250–7259. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.24.7250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tuffereau C, Benejean J, Roque Alfonso A-M, Flamand A, Fishman M C. Neuronal cell surface molecules mediate specific binding to rabies virus glycoprotein expressed by a recombinant baculovirus on the surfaces of lepidoptera cells. J Virol. 1998;72:1085–1091. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.2.1085-1091.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Whitt M A, Buonocore L, Prehaud C, Rose J K. Membrane fusion activity, oligomerization, and assembly of the rabies virus glycoprotein. Virology. 1991;185:681–688. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(91)90539-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52a.World Health Organization. World survey of rabies no. 34 for the year 1998. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Worobey M, Holmes E C. Evolutionary aspects of recombination in RNA viruses. J Gen Virol. 1999;80:2535–2543. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-80-10-2535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wu C I, Li W H. Evidence for higher rates of nucleotide substitution in rodents than in man. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:1741–1745. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.6.1741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]