Abstract

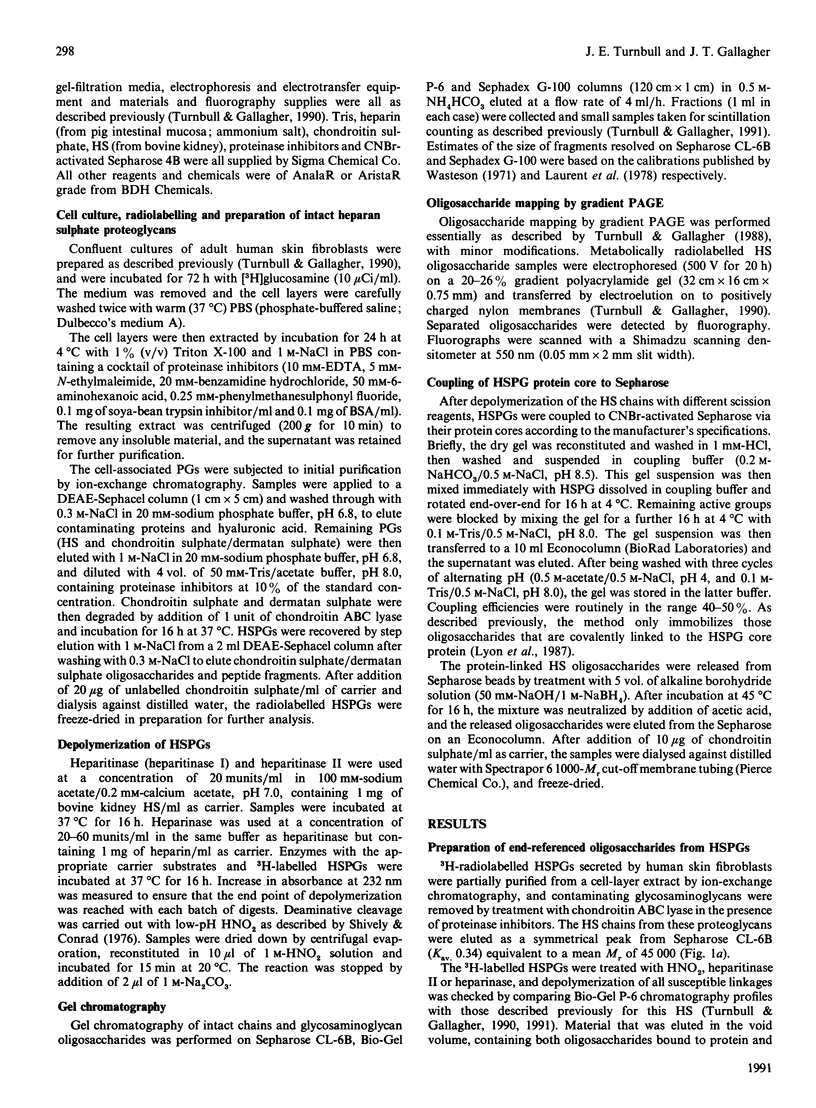

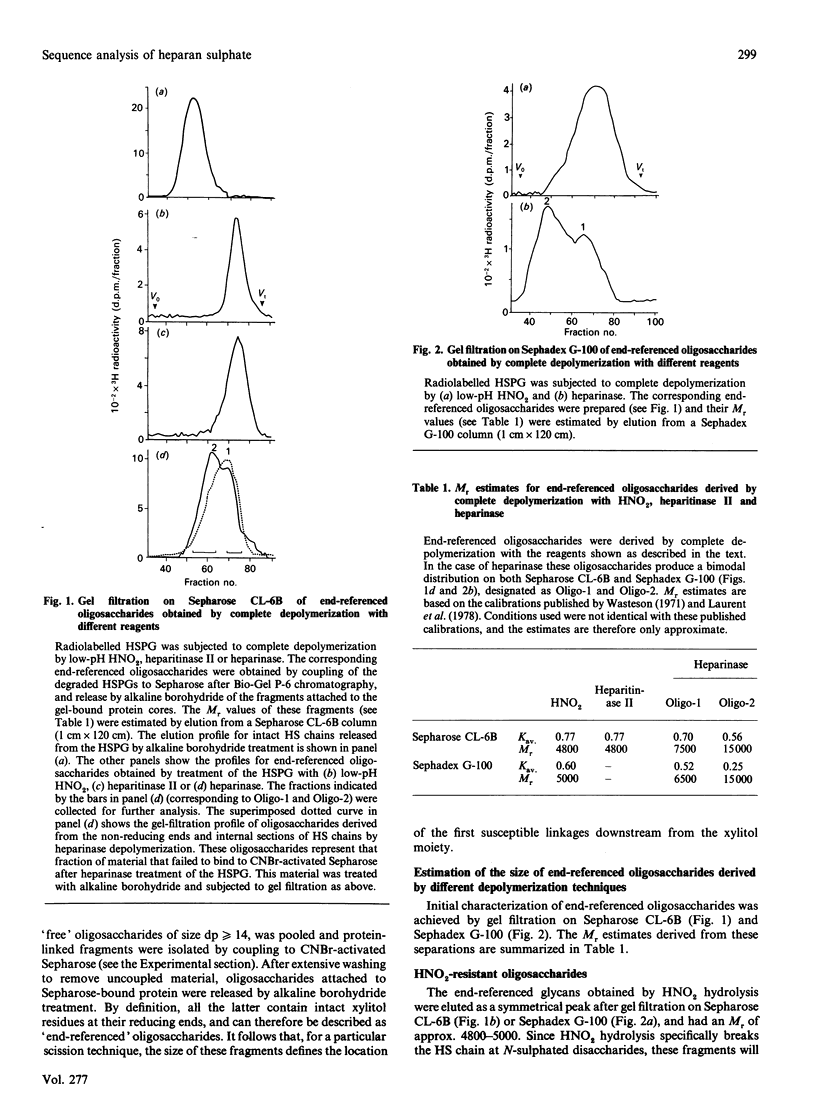

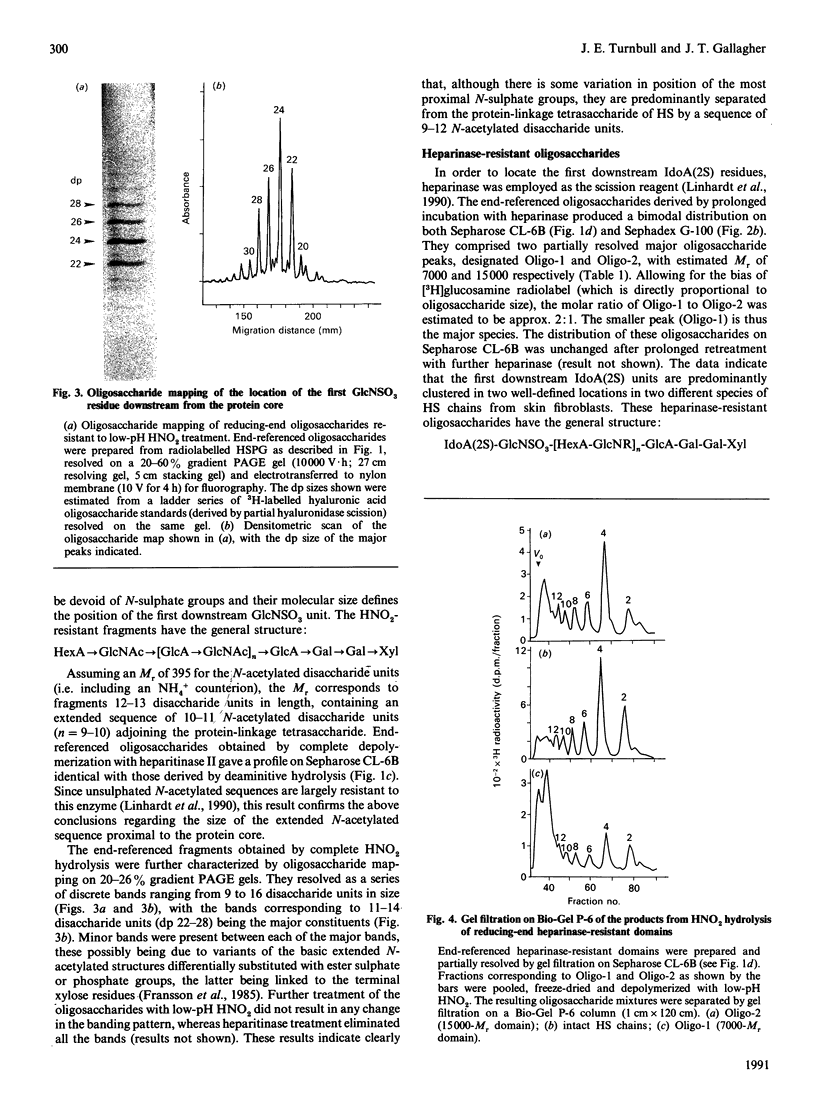

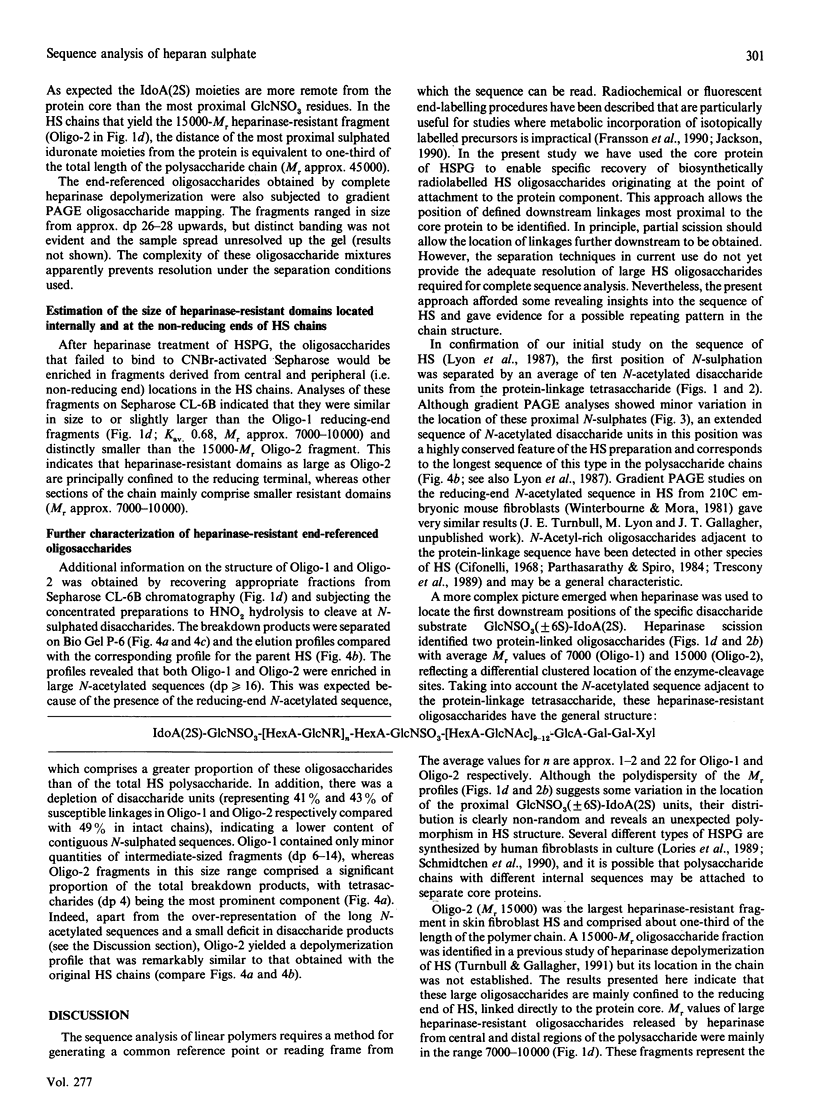

A strategy that we originally used to identify an N-acetylated domain adjacent to the protein-linkage sequence of heparan sulphate proteoglycan (HSPG) [Lyon, Steward, Hampson & Gallagher (1987) Biochem. J. 242, 493-498] has been adapted for analysis of the location of GlcNSO3-HexA and GlcNSO3(+/- 6S)-IdoA(2S) units most proximal to the core protein. [3H]Glucosamine-labelled HSPG from human skin fibroblasts was depolymerized by using HNO2 or heparinase under conditions that allowed cleavage of all susceptible linkages. The degraded PG was coupled to Sepharose beads through the protein component, enabling specific recovery of protein-linked resistant oligosaccharides. These were released by treatment with alkaline borohydride and analysed by gel filtration and gradient PAGE. This strategy allowed investigation of the sequence of sugar residues along the chain relative to a common reference point (i.e. the reducing end of the chain). HNO2 scission confirmed the presence of a well-defined N-acetylated sequence predominantly 9-12 disaccharide units in length proximal to the core protein. Heparinase scission produced two classes of oligosaccharides (Mr approx. 7000 and 15,000) with the general formula: IdoA(2S)-GlcNSO3-[HexA-GlcNR]n-HexA-GlcNSO3-[Hex A-GlcNAc]9 12-GlcA-Gal-Gal-Xyl in which the average value for n is 1-2 for the 7000-Mr species and approx. 22 for the 15,000-Mr species. The latter oligosaccharides extend to about one-third of the total length of the HS chains (Mr approx. 45,000). HNO2 scission of these oligosaccharides enabled hypothetical models for their sequence to be proposed. The general arrangement of N-sulphated and N-acetylated disaccharides between the proximal GlcNSO3 and terminal IdoA(2S) residues of the 15,000-Mr fragment was similar to that in the original polysaccharide, suggesting the possibility of a tandemly repeating pattern in the sequence of HS.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Fransson L. A., Havsmark B., Silverberg I. A method for the sequence analysis of dermatan sulphate. Biochem J. 1990 Jul 15;269(2):381–388. doi: 10.1042/bj2690381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fransson L. A., Silverberg I., Carlstedt I. Structure of the heparan sulfate-protein linkage region. Demonstration of the sequence galactosyl-galactosyl-xylose-2-phosphate. J Biol Chem. 1985 Nov 25;260(27):14722–14726. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher J. T., Lyon M., Steward W. P. Structure and function of heparan sulphate proteoglycans. Biochem J. 1986 Jun 1;236(2):313–325. doi: 10.1042/bj2360313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher J. T. The extended family of proteoglycans: social residents of the pericellular zone. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1989 Dec;1(6):1201–1218. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(89)80072-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher J. T., Turnbull J. E., Lyon M. Heparan sulphate proteoglycans. Biochem Soc Trans. 1990 Apr;18(2):207–209. doi: 10.1042/bst0180207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher J. T., Walker A. Molecular distinctions between heparan sulphate and heparin. Analysis of sulphation patterns indicates that heparan sulphate and heparin are separate families of N-sulphated polysaccharides. Biochem J. 1985 Sep 15;230(3):665–674. doi: 10.1042/bj2300665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson P. The use of polyacrylamide-gel electrophoresis for the high-resolution separation of reducing saccharides labelled with the fluorophore 8-aminonaphthalene-1,3,6-trisulphonic acid. Detection of picomolar quantities by an imaging system based on a cooled charge-coupled device. Biochem J. 1990 Sep 15;270(3):705–713. doi: 10.1042/bj2700705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsson K. G., Lindahl U., Horner A. A. Location of antithrombin-binding regions in rat skin heparin proteoglycans. Biochem J. 1986 Dec 15;240(3):625–632. doi: 10.1042/bj2400625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurent T. C., Tengblad A., Thunberg L., Hök M., Lindahl U. The molecular-weight-dependence of the anti-coagulant activity of heparin. Biochem J. 1978 Nov 1;175(2):691–701. doi: 10.1042/bj1750691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lidholt K., Kjellén L., Lindahl U. Biosynthesis of heparin. Relationship between the polymerization and sulphation processes. Biochem J. 1989 Aug 1;261(3):999–1007. doi: 10.1042/bj2610999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindahl U., Thunberg L., Bäckström G., Riesenfeld J., Nordling K., Björk I. Extension and structural variability of the antithrombin-binding sequence in heparin. J Biol Chem. 1984 Oct 25;259(20):12368–12376. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linhardt R. J., Cohen D. M., Rice K. G. Nonrandom structural features in the heparin polymer. Biochemistry. 1989 Apr 4;28(7):2888–2894. doi: 10.1021/bi00433a021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linhardt R. J., Merchant Z. M., Rice K. G., Kim Y. S., Fitzgerald G. L., Grant A. C., Langer R. Evidence of random structural features in the heparin polymer. Biochemistry. 1985 Dec 17;24(26):7805–7810. doi: 10.1021/bi00347a045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linhardt R. J., Turnbull J. E., Wang H. M., Loganathan D., Gallagher J. T. Examination of the substrate specificity of heparin and heparan sulfate lyases. Biochemistry. 1990 Mar 13;29(10):2611–2617. doi: 10.1021/bi00462a026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lories V., Cassiman J. J., Van den Berghe H., David G. Multiple distinct membrane heparan sulfate proteoglycans in human lung fibroblasts. J Biol Chem. 1989 Apr 25;264(12):7009–7016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyon M., Steward W. P., Hampson I. N., Gallagher J. T. Identification of an extended N-acetylated sequence adjacent to the protein-linkage region of fibroblast heparan sulphate. Biochem J. 1987 Mar 1;242(2):493–498. doi: 10.1042/bj2420493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nader H. B., Dietrich C. P., Buonassisi V., Colburn P. Heparin sequences in the heparan sulfate chains of an endothelial cell proteoglycan. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1987 Jun;84(11):3565–3569. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.11.3565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oeben M., Keller R., Stuhlsatz H. W., Greiling H. Constant and variable domains of different disaccharide structure in corneal keratan sulphate chains. Biochem J. 1987 Nov 15;248(1):85–93. doi: 10.1042/bj2480085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oscarsson L. G., Pejler G., Lindahl U. Location of the antithrombin-binding sequence in the heparin chain. J Biol Chem. 1989 Jan 5;264(1):296–304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parthasarathy N., Spiro R. G. Isolation and characterization of the heparan sulfate proteoglycan of the bovine glomerular basement membrane. J Biol Chem. 1984 Oct 25;259(20):12749–12755. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radoff S., Danishefsky I. Location on heparin of the oligosaccharide section essential for anticoagulant activity. J Biol Chem. 1984 Jan 10;259(1):166–172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenfeld L., Danishefsky I. Location of specific oligosaccharides in heparin in terms of their distance from the protein linkage region in the native proteoglycan. J Biol Chem. 1988 Jan 5;263(1):262–266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidtchen A., Carlstedt I., Malmström A., Fransson L. A. Inventory of human skin fibroblast proteoglycans. Identification of multiple heparan and chondroitin/dermatan sulphate proteoglycans. Biochem J. 1990 Jan 1;265(1):289–300. doi: 10.1042/bj2650289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shively J. E., Conrad H. E. Formation of anhydrosugars in the chemical depolymerization of heparin. Biochemistry. 1976 Sep 7;15(18):3932–3942. doi: 10.1021/bi00663a005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trescony P. V., Oegema T. R., Jr, Farnam B. J., Deloria L. B. Analysis of heparan sulfate from the Engelbreth-Holm-Swarm (EHS) tumor. Connect Tissue Res. 1989;19(2-4):219–242. doi: 10.3109/03008208909043898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turnbull J. E., Gallagher J. T. Distribution of iduronate 2-sulphate residues in heparan sulphate. Evidence for an ordered polymeric structure. Biochem J. 1991 Feb 1;273(Pt 3):553–559. doi: 10.1042/bj2730553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turnbull J. E., Gallagher J. T. Molecular organization of heparan sulphate from human skin fibroblasts. Biochem J. 1990 Feb 1;265(3):715–724. doi: 10.1042/bj2650715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turnbull J. E., Gallagher J. T. Oligosaccharide mapping of heparan sulphate by polyacrylamide-gradient-gel electrophoresis and electrotransfer to nylon membrane. Biochem J. 1988 Apr 15;251(2):597–608. doi: 10.1042/bj2510597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasteson A. A method for the determination of the molecular weight and molecular-weight distribution of chondroitin sulphate. J Chromatogr. 1971 Jul 8;59(1):87–97. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(01)80009-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winterbourne D. J., Mora P. T. Cells selected for high tumorigenicity or transformed by simian virus 40 synthesize heparan sulfate with reduced degree of sulfation. J Biol Chem. 1981 May 10;256(9):4310–4320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]