Abstract

Background

Clopidogrel is widely used for the secondary prevention of atherothrombotic events in patients with coronary artery disease (CAD), ischemic stroke, and peripheral arterial disease (PAD). CYP2C19 plays a pivotal role in the conversion of clopidogrel to its active metabolite. Clopidogrel-treated carriers of a CYP2C19 loss-of-function allele (LOF) may have a higher risk of new atherothrombotic events. Previous studies on genotype-guided treatment were mainly performed in CAD and showed mixed results.

Purpose

To simultaneously investigate the impact of CYP2C19 genotype status on the rate of atherothrombotic events in the most common types of atherosclerotic disease (CAD, stroke, PAD).

Methods

A comprehensive search in Pubmed, EMBASE, and MEDLINE from their inception to July 23rd 2023 was performed. Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) comparing genotype-guided and standard antithrombotic treatment, and cohort studies and post hoc analyses of RCTs concerning the association between CYP2C19 genotype status and clinical outcomes in clopidogrel-treated patients were included. The primary efficacy endpoint was major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) and the safety end point major bleeding. Secondary endpoints were myocardial infarction, stent thrombosis, and ischemic stroke.

Results

Forty-four studies were identified: 11 studies on CAD, 29 studies on stroke, and 4 studies on PAD. In CAD, genotype-guided therapy significantly reduced the risk of MACE [risk ratio (RR) 0.60, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.43–0.83], myocardial infarction (RR 0.53, 95% CI 0.42–0.68), and stent thrombosis (RR 0.64, 95% CI 0.43–0.94), compared with standard antithrombotic treatment. The rate of major bleeding did not differ significantly (RR 0.93, 95% CI 0.70–1.23). Most RCTs were performed in patients after percutaneous coronary intervention (9/11). In stroke, LOF carriers had a significantly higher risk of MACE (RR 1.61, 95% CI 1.25–2.08) and recurrent ischemic stroke (RR 1.89, 95% CI 1.48–2.40) compared with non-carriers. No significant differences were found in major bleeding (RR 0.90, 95% CI 0.43–1.89). In the 6955 patients with symptomatic PAD treated with clopidogrel in the EUCLID trial, no differences in MACE or major bleeding were found between LOF carriers and non-carriers. In three smaller studies on patients with PAD treated with clopidogrel after endovascular therapy, CYP2C19 genotype status was significantly associated with atherothrombotic events.

Conclusions

Genotype-guided treatment significantly decreased the rate of atherothrombotic events in patients with CAD, especially after PCI. In patients with history of stroke, LOF carriers treated with clopidogrel had a higher risk of MACE and recurrent stroke. The available evidence in PAD with regard to major adverse limb events is too limited to draw meaningful conclusions.

Registration

PROSPERO identifier no. CRD42020220284.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s40265-024-02076-7.

Key Points

| In patients with CAD, genotype-guided treatment significantly decreased the rate of atherothrombotic events, especially after PCI. |

| In patients with history of stroke, LOF carriers treated with clopidogrel had a higher risk of MACE and recurrent stroke. |

| In PAD, the available evidence with regard to major adverse limb events is too limited to draw meaningful conclusions. |

Introduction

Coronary artery disease (CAD), cerebrovascular disease, and peripheral arterial disease (PAD) are all clinical manifestations of systemic atherosclerosis. In patients with these atherosclerotic diseases, the platelet aggregation inhibitor clopidogrel is widely used for the secondary prevention of thrombotic events. Nevertheless, in clinical practice, many patients receiving clopidogrel show a high residual platelet reactivity. Consequently, these patients are still at risk of adverse cardiovascular atherothrombotic events.

A part of this “clopidogrel resistance” may be explained by genetic variations. Clopidogrel is a thienopyridine prodrug that needs biotransformation by hepatic cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzymes to generate its clinically active metabolite. CYP2C19 plays a pivotal role in this activation process [1]. The CYP2C19 gene is, however, highly polymorphic, with CYP2C19*2 and CYP2C19*3 being the most common polymorphisms. These loss-of-function variants (LOF) can be used to classify patients as normal or extensive metabolizers (EM; CYP2C19 *1/*1), intermediate metabolizers (IM; CYP2C19 *1/*2 and *1/*3), or poor metabolizers (PM; CYP2C19 *2/*2, *2/*3 and *3/*3).

There is substantial evidence that CYP2C19 IMs and PMs have higher on-treatment platelet reactivity than EMs [2, 3]. Most clinical studies on the rate of cardiovascular events in CYP2C19 IMs and PMs were performed in patients with acute coronary syndrome. In patients who underwent percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), a higher risk of cardiovascular events was observed in CYP2C19 LOF carriers compared with non-carriers [4, 5]. Moreover, the beneficial effects of a CYP2C19 genotype-guided treatment strategy on the reduction of cardiovascular events in this patient group was demonstrated in several meta-analyses [6–9]. In patients with ischemic stroke treated with clopidogrel, a meta-analysis showed that CYP2C19 LOF carriers had a 1.92 increased risk of recurrent stroke compared with non-carriers [10]. Less clinical evidence is available for patients with peripheral arterial disease [11].

The aim of this systematic review and meta-analysis is to integrate the available research data in patients with acute coronary syndrome, stroke and peripheral arterial disease and, thus, to provide one large overview of the impact of CYP2C19 metabolizer status on the risk of cardiovascular events in patients with the most common manifestations of atherosclerotic disease.

Methods

The study protocol was registered with PROSPERO, number CRD42020220284, and Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines were followed.

Search Strategy

A comprehensive search in the electronic databases Pubmed, EMBASE, and MEDLINE from their inception to 23 July 2023 was performed. Search terms referring to CYP2C19 genotype, peripheral arterial disease, coronary artery disease, stroke, and treatment with platelet aggregation inhibitors were used in various configurations. Furthermore, the reference lists of the selected articles were searched manually to identify additional studies. Lastly, ClinicalTrials.gov was screened for completed but yet unpublished studies. Details of our electronic search strategy in Pubmed, EMBASE, and MEDLINE are provided in the appendix.

Study Selection

After removal of duplicates, two authors (D.M. and L.W.) independently screened the title and abstract of each record. The same authors independently assessed the full text of all eligible articles. Any disagreements between the authors were resolved via consensus or, in case of persistent discrepancies, by discussion with a third author (M.W.).

Studies on patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease who had an indication for platelet aggregation inhibition therapy were considered eligible for inclusion if: (1) CYP2C19 genotype status was available and (2) clinical outcome measurements were reported. Clinical outcome measurements comprised major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE), myocardial infarction, (ischemic) stroke, cardiovascular death, stent thrombosis, and (major) bleeding. Animal studies, in vitro studies, reviews, editorials, and case reports were excluded. When different articles contained duplicate data, the article with the largest sample size or most complete information was included.

Two different types of studies were available: (1) randomized controlled trials (RCTs) comparing a genotype-guided antithrombotic treatment with standard treatment and (2) cohort studies or post hoc analyses of RCTs describing the association between CYP2C19 genotype status and clinical outcomes. Cohort studies were only included if clopidogrel was used as platelet aggregation inhibitor. For the post hoc analyses of RCTs, we included only the clopidogrel-treated arm in our analysis.

Our study population was divided in three subgroups based on the type of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease: (1) patients with coronary artery disease (stable disease or acute coronary syndrome), (2) patients with stroke or transient ischemic attack (TIA), and (3) patients with peripheral arterial disease. For each subgroup, the available data were analyzed separately.

For patients with coronary artery disease, only data from RCTs comparing genotype-guided and standard antithrombotic treatment were included, as this study type is generally considered to have the highest level of evidence. Because RCTs were not available in patients with peripheral arterial disease and scarcely available in patients with stroke or TIA (n = 3), only cohort studies or post hoc analyses of RCTs describing the association between CYP2C19 genotype status and clinical outcomes were included in these patient groups. The three RCTs in patients with stroke or TIA were described separately.

Data Extraction

Two reviewers (D.M. and L.W.) independently extracted data from the selected articles using a standardized form. Any disagreements were resolved by consensus. The following data were extracted: study acronym (if any), last name of the first author, full title, year of publication, study population, inclusion criteria, sample size, treatment groups (drug, dose, and duration of treatment), CYP2C19 genotype status, baseline patient characteristics, outcome measurements, and duration of follow-up. The primary efficacy endpoint was the occurrence of MACE. MACE was defined as a composite of cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction and stroke. However, broader definitions including other relevant complications of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease were also allowed.

The primary safety end point was (major) bleeding. Secondary end points were cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, stent thrombosis, and (ischemic) stroke.

Quality Assessment

The quality of all included studies was assessed by two independent reviewers (D.M. and L.W.). Any discrepancies were resolved by discussion. For the RCTs comparing genotype-guided and standard antithrombotic treatment, risk of bias was assessed with the Cochrane collaboration’s risk of bias tool for randomized trials [12]. In brief, this tool is based on the judgement of the risk of bias in five distinct domains: the randomization process, deviations from the intended interventions, missing outcome data, measurement of the outcome, and selection of the reported results. An overall low risk of bias was assigned to studies with a low risk of bias for all domains or studies that raised concerns in a maximum of one domain. An overall medium risk of bias was assigned to studies that raised concerns in two domains, and an overall high risk of bias to studies that raised concerns in more than two domains or studies with a high risk of bias in at least one domain. The quality of the cohort studies and post hoc analyses of RCTs was evaluated using the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) [13]. According to this tool, the quality of a study is judged in three different domains: selection of cohorts, comparability of cohorts, and assessment of outcome. An overall quality score (0–9 stars) was assigned for each included study.

CYP2C19 Alleles Measured in Cohort Studies and Post Hoc Analyses of RCTs

To determine CYPC219 genotype status, the loss-of-function (LOF) alleles *2 and/or *3 were measured in most studies. Few studies also described other LOF alleles: *4, *5, *6, *7, and *8. Furthermore, some studies also provided data on the gain-of-function allele *17. The included cohort studies and post hoc analyses of RCTs used different ways to classify patients according to CYP2C19 genotype status. Some studies compared clinical outcomes between LOF allele carriers (LOF carriers) and patients without a LOF allele (non-carriers), while other studies divided their study population in different types of metabolizers. In these last studies, extensive metabolizers had no LOF alleles (*1/*1), intermediate metabolizers had one copy of a LOF allele (*1/*2-*8), and poor metabolizers had two copies of a LOF allele (*2-*8/*2-*8). Some studies also provided data for ultrarapid metabolizers (patients carrying one or two copies of *17: *1/*17 or *17/*17) and/or unknown metabolizers (patients carrying one copy of a LOF allele and one copy of *17: *2-*8/*17).

To increase the uniformity of data in our analysis, we divided the participants into two groups: LOF carriers and non-carriers. Extensive metabolizers were classified as noncarrier and intermediate and poor metabolizers as LOF carriers. Ultrarapid and unknown metabolizers were, if possible, excluded from our analysis as the *17 allele was not consistently determined in all included studies and the presence of a *17 allele may influence the clinical outcome measurements.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using Cochrane Review Manager software, version 5.3 (RevMan 5.3). For all clinical outcomes, pooled effect estimates were calculated using a random-effects model based on the Mantel–Haenszel method and expressed as risk ratios (RR) with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). Results were graphically displayed using forest plots. The I2 statistic was calculated to assess heterogeneity between studies. Moderate heterogeneity was assumed when I2 was higher than 30% and substantial heterogeneity when I2 was higher than 50%.

Results

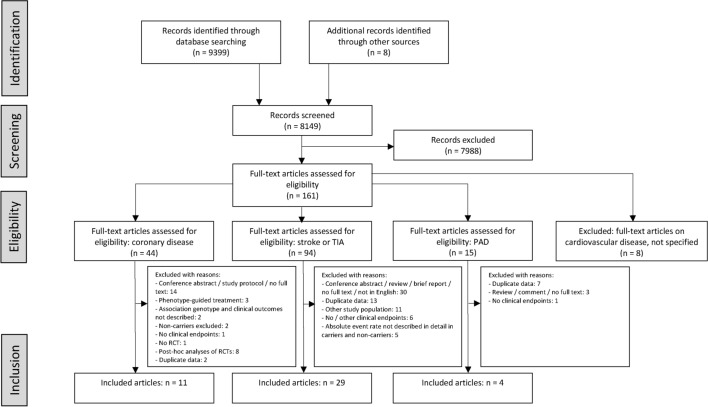

A total of 9407 records were identified by the search in the electronic databases and other sources (Fig. 1). After removal of exact duplicates and screening of title and abstract, 161 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility. Eventually, 44 articles were included in our analysis: 11 articles on patients with coronary disease, 29 articles on patients with stroke or TIA, and 4 articles on patients with peripheral arterial disease. Moreover, three studies (two RCTs and one post hoc analysis of an RCT) in patients with stroke or TIA involving only CYP2C19 LOF carriers were identified. The main results of these three studies were described separately.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart

Coronary Disease

Eleven RCTs comparing genotype-guided and standard antithrombotic treatment were included (Table 1) [14–24]. These 11 RCTs contained a total of 11,740 patients (range 60–5276). Of these 11,740 patients, 5958 were treated with genotype-guided treatment and 5782 with standard antithrombotic treatment.

Table 1.

Characteristics of studies on coronary artery disease

| Study | Region | Study period | Patients | Sample size | Age, mean (years) | Male (%) | Intervention | Method of genotyping + CYP2C19 alleles | Duration of follow-up | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genotype-guided | Standard | |||||||||

| Al-Rubaish, 2021 [14] | Saudi Arabia | 2013–2020 | STEMI + PCI |

687 G: 375 S: 312 |

56.2 | 80.8 |

LOF carriers: ticagrelor Non-carriers: clopidogrel All patients: DAPT for at least 12 months after STEMI |

Clopidogrel All patients: DAPT for at least 12 months after STEMI |

Spartan RX *2 |

12 months |

|

Claassens, 2019 [15] POPular Genetics |

Europe | 2011–2018 | STEMI + PCI |

2488 G: 1242 S: 1246 |

61.7 | 74.8 |

LOF carriers: ticagrelor or prasugrel Non-carriers: clopidogrel |

Ticagrelor or prasugrel |

Spartan RX or TaqMan StepOnePlus *2, *3 |

12 months |

|

Notarangelo, 2018 [16] PHARMCLO |

Europe | 2013–2015 | ACS |

888 G: 448 S: 440 |

70.9 | 68 | Clopidogrel, prasugrel, or ticagrelor based on an algorithm including genotyping and clinical characteristics | Clopidogrel, prasugrel, or ticagrelor based on clinical characteristics |

ST Q3 *2, *17 |

12 months |

|

Pereira, 2020 [17] TAILOR-PCI |

USA, Canada, South Korea, Mexico | 2013–2018 | ACS or stable CAD + PCI |

5276 G: 2641 S: 2635 |

62 (median) | 75.5 |

LOF carriers: ticagrelor (or prasugrel in case of ticagrelor intolerance) Non-carriers or inconclusive results: clopidogrel All patients: aspirin |

Clopidogrel All patients: aspirin |

TaqMan *2, *3 |

12 months |

| Roberts, 2012 [18] | Canada | 2010–2011 | NSTEMI or stable CAD + PCI |

187 G: 91 S: 96 |

60.2 | 78.1 |

LOF carriers: prasugrel Non-carriers: clopidogrel |

Clopidogrel |

Spartan RX *2 |

30 days |

| Shi, 2021 [19] | China | 2019 | STEMI, NSTEMI or unstable angina + PCI |

301 G: 201 S: 100 |

59.7 | 75.1 |

Initial selection of P2Y12 receptor inhibitors based on clinical characteristics (ticagrelor or clopidogrel). After genetic results: reconsidered by cardiologists. LOF carriers: ticagrelor recommended. All patients: aspirin |

Selection of P2Y12 receptor inhibitors based on clinical characteristics (ticagrelor or clopidogrel). All patients: aspirin |

TL988A *2, *3 |

12 months |

| Tam, 2017 [20] | China | 2013–2015 | STEMI, NSTEMI or unstable angina |

132 G: 65 S: 67 |

60.9 | 80.3 |

Clopidogrel LD 600 mg for STEMI + PCI, LD 300 mg for STEMI without PCI, NSTEMI or unstable angina LOF carriers: additional LD of ticagrelor 180 mg, MD ticagrelor 2 dd 90 mg Non-carriers: clopidogrel MD 75 mg/day |

Clopidogrel LD 600 mg for STEMI + PCI, LD 300 mg for STEMI without PCI, NSTEMI or unstable angina. Clopidogrel MD 75 mg/day |

Verigene or Roche LightCycler 480 *2, *3 |

1 month |

|

Tomaniak, 2017 [21] ONSIDE TEST |

Poland | 2012–2015 | Stable CAD + PCI |

60 G: 34 S: 26 |

62.1 | 77.3 |

LOF carriers: aspirin + prasugrel LD 60 mg before PCI, MD 10 mg/day for 1 week, followed by therapy de-escalation to clopidogrel + aspirin Non-carriers: clopidogrel + aspirin |

Clopidogrel + aspirin |

Spartan RX *2 |

12 months |

|

Tuteja, 2020 [22] ADAPT |

United States | 2014–2016 | ACS or stable CAD + PCI |

504 G: 249 S: 255 |

63 | 73.5 |

EM: clopidogrel IM: prasugrel or ticagrelor PM: prasugrel or ticagrelor Rapid or ultrarapid metabolizer: clopidogrel |

Choice of antiplatelet therapy: usual care decided by treating physician |

Spartan RX or Infinium Global Screening Array *2, *3, *17 |

16.4 months (mean) |

| Xie, 2013 [23] | China | 2011 | ACS or unstable angina + PCI |

600 G: 301 S: 299 |

57.9 | 78 |

EM: clopidogrel LD 300 mg, MD 75 mg/day IM: clopidogrel LD 600 mg, MD 150 mg/day PM: clopidogrel LD 600 mg, MD 150 mg + cilostazol LD 200 mg, MD 2 dd 100 mg |

Clopidogrel LD 300 mg, MD 75 mg/day |

Commercially available kits from Shanghai Baiao Technology Co *2, *3 |

180 days |

| Zhang, 2020 [24] | China | 2014–2017 | ACS + PCI |

617 G: 311 S: 306 |

64.1 | 70.3 |

EM: clopidogrel 75 mg/day IM: clopidogrel 2 dd 75 mg PM: ticagrelor 2 dd 90 mg All patients: aspirin |

Clopidogrel 75 mg/day All patients: aspirin |

Sinochips Bioscience Co *2, *3 |

12 months |

STEMI, ST-elevation myocardial infarction; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; G, genotype-guided treatment; S, standard treatment; LOF, loss-of-function allele; ACS, acute coronary syndrome; CAD, coronary artery disease; LD, loading dose; MD, maintenance dose; EM, extensive metabolizer; IM, intermediate metabolizer; PM, poor metabolizer

In three RCTs, the study population consisted of patients with acute coronary syndrome or stable coronary artery disease [17, 18, 22]. Of the remaining eight RCTs, seven studies included only patients with acute coronary syndrome [14–16, 19, 20, 23, 24], and one study included only patients with stable coronary artery disease [21]. Furthermore, performance of percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) was part of the inclusion criteria in nine RCTs [14, 15, 17–19, 21–24]. In the other two RCTs, not all patients underwent a revascularization procedure: in the PHARMCLO study, 62% underwent a PCI and 11% coronary artery bypass grafting [16], and in the study of Tam et al., 77% underwent a PCI and 4% coronary artery bypass grafting [20].

The drug regimens used as genotype-guided and standard treatment differed between the studies. In most RCTs, LOF carriers in the genotype-guided arm were treated with ticagrelor or prasugrel and non-carriers with clopidogrel. However, Xie et al. prescribed a double dose of clopidogrel in intermediate metabolizers and a combination of double-dose clopidogrel and cilostazol in poor metabolizers [23], Zhang et al. prescribed a double-dose of clopidogrel in intermediate metabolizers [24], and Tomaniak et al. used a treatment regimen with prasugrel for 1 week followed by therapy de-escalation to clopidogrel in LOF carriers [21]. In the standard treatment arm, most patients were treated with clopidogrel ± aspirin, except in the POPular genetics study, which used ticagrelor or prasugrel [15], and the PHARMCLO study [16], the ADAPT PCI study [22], and the study from Shi et al. [19], in which the choice of antiplatelet therapy was decided by the treating physician. Definitions of MACE and major bleeding differed among the included studies (Table 2).

Table 2.

Definitions of outcome measurements in studies on coronary artery disease

| Study | MACE | Major bleeding |

|---|---|---|

| Al-Rubaish, 2021 | 1, 2, 3, 4 | PLATO |

| Claassens, 2019 | 1, 2, 3, 5 | PLATO |

| Notarangelo, 2018 | 1, 2, 3 | BARC type 3–5 |

| Pereira, 2020 | 1, 2, 3, 5, 6 | TIMI |

| Roberts, 2012 | 1, 2, 5, 7 | TIMI |

| Shi, 2021 | 2, 3, 5, 8, 9 | BARC ≥ type 2 |

| Tam, 2017 | - | Not further specified |

| Tomaniak, 2017 | 1, 2, 5, 10 | BARC type 3 + 5 |

| Tuteja, 2020 | 1, 2, 3, 5, 9 | BARC type 3 + 5 |

| Xie, 2013 | 2, 3, 8 | – |

| Zhang, 2020 | 2, 5, 8 | BARC type 2, 3, 5 |

MACE, major adverse cardiovascular events

1 = cardiovascular death; 2 = myocardial infarction; 3 = stroke; 4 = major bleeding; 5 = stent thrombosis; 6 = severe recurrent ischemia; 7 = readmission to hospital; 8 = all-cause death; 9 = urgent revascularization; 10 = revascularization at 1 year

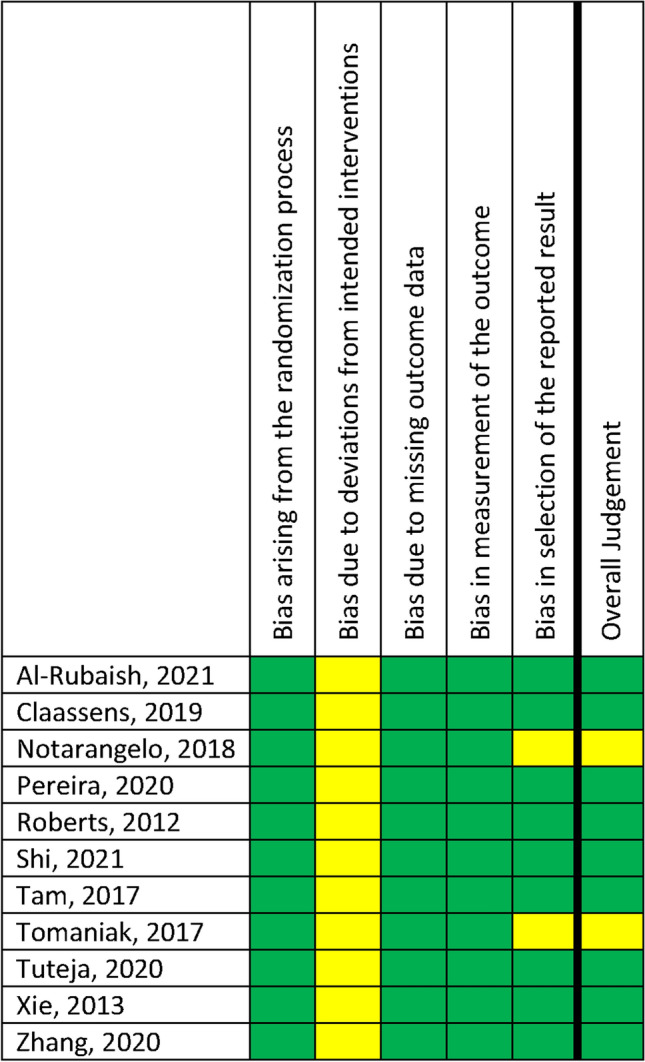

Risk of Bias Assessment

Some concerns on the risk of bias due to deviations from intended interventions were noted in all studies and some concerns on the risk of bias in selection of the reported result in two studies (Fig. 2). In none of the studies, a high risk of bias was found. Overall, nine studies were classified as low risk for bias and two studies raised some concerns.

Fig. 2.

Risk of bias assessment in studies on coronary artery disease. The risk of bias was assessed with the Cochrane collaboration’s risk of bias tool for randomized trials

Clinical Outcomes

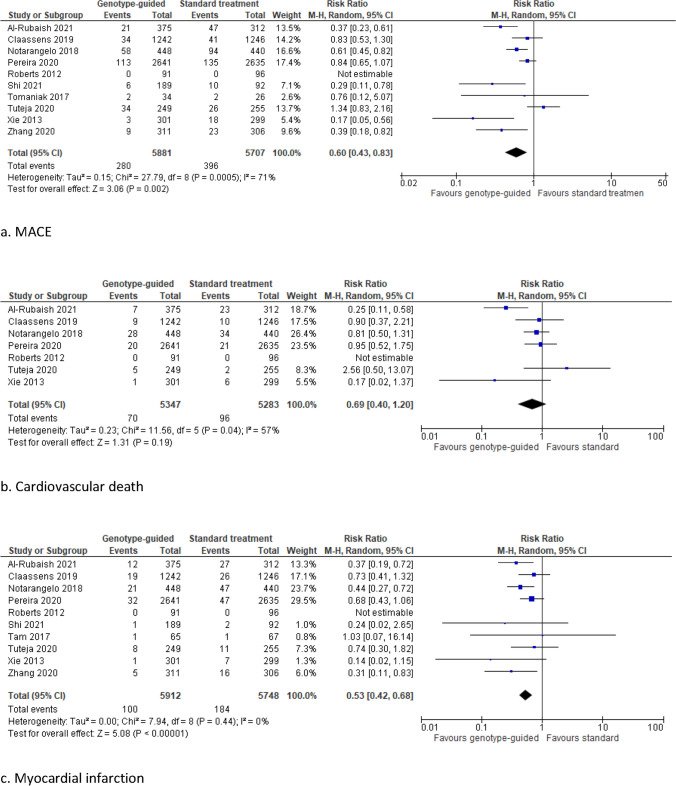

Compared with standard antithrombotic treatment, genotype-guided therapy significantly reduced the risk of MACE (RR 0.60, 95% CI 0.43–0.83, I2 71%), myocardial infarction (RR 0.53, 95% CI 0.42–0.68, I2 0%), and stent thrombosis (RR 0.64, 95% CI 0.43–0.94, I2 0%) (Fig. 3). No significant differences between treatment groups were observed in the rate of cardiovascular death (RR 0.69, 95% CI 0.40–1.20, I2 57%), stroke (RR 0.65, 95% CI 0.42–1.01, I2 0%), and major bleeding (RR 0.93, 95% CI 0.70–1.23, I2 0%).

Fig. 3.

Forest plots for the ischemic and bleeding outcomes in studies on coronary artery disease

Comparable results were found for all thrombotic and bleeding outcomes in a subgroup analysis excluding the two RCTs that raised some concerns (Supplementary Fig. 1), in a subgroup analysis on the nine RCTs that included only patients in whom a percutaneous coronary intervention was performed (Supplemental Fig. 2), and in a subgroup analysis that excluded the only RCT using a genotype-guided de-escalation strategy (POPular Genetics) (data not shown). In a subgroup analysis based on studies with a follow-up duration of 12 months or more and in a subgroup analysis on studies including only patients with acute coronary syndrome, the risk of stent thrombosis did not differ significantly between genotype-guided and standard antithrombotic treatment (RR 0.68, 95% CI 0.46–1.02, I2 0%, and RR 0.63, 95% CI 0.39–1.01, I2 0%, respectively) (Supplementary Figs. 3d and 4d). A significantly decreased risk of stroke was found in the subgroup analysis on studies including only patients with acute coronary syndrome (RR 0.56, 95% CI 0.33–0.97, I2 0%) (Supplementary Fig. 4e).

Stroke

A total of 29 studies describing the association between CYP2C19 genotype status, and clinical outcomes were eligible for inclusion in our analysis [25–51]. Of these 29 studies, 22 were cohort studies and 7 were post hoc analyses of RCTs. Characteristics of these studies are described in Table 3.

Table 3.

Characteristics of studies on stroke or TIA

| Study | Study type | Region | Study period | Patients | Sample size | Age, mean (years) | Male (%) | Medication | Follow-up | Method of genotyping + CYP2C19 alleles | Mode of reporting results in original article |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Al-Rubaish, 2022 [25] | Cohort | Saudi Arabia | 2018–2019 | Acute IS | 42 | – | – | Clopidogrel 75 mg/day or clopidogrel 75 mg/day + aspirin 50–325 mg/day | 6 months |

Spartan RX, confirmed by TaqMan *2 |

LOF–no LOF |

| Fu, 2020 [26] | Cohort | Chinese-Han | Acute IS | 131 | 61.4 | 79 | Clopidogrel 75 mg/day | 6 months |

PCR-RFLP *2, *3 |

LOF–no LOF | |

| Fukuma, 2022 [27] | Cohort | Japan | 2013–2015 | Acute IS or TIA with large-artery atherosclerosis | 194 | – | – | Clopidogrel 75 mg/day ± other antiplatelet agents (aspirin 200 mg/day, cilostazol 200 mg/day), anticoagulant agents (including argatroban injection) | 90 days |

TaqMan *2, *3, *17 |

EM–IM–PM (patients with *17 excluded from analysis) |

| Hoh, 2015 [28] | Cohort | USA | Stroke or TIA due to ICAD | 188 | 67 | 63.3 | Clopidogrel + aspirin | 12 months |

Sequenom, TaqMan or pyrosequencing (Qiagen) *2, *3, *8, *17 |

LOF–no LOF | |

| Jardaq, 2022 [73] | Cohort | Kurdistan | 2021 | IS | 60 | – | 57 | Clopidogrel 75 mg/day | NR |

ABI PRISM 3700 genetic analyzer *2, *3 |

EM–IM–PM |

| Kitazono, 2023 [74] | Post hoc analysis RCT (PRASTRO-III) | Japan | 2018–2020 | IS (large-artery atherosclerosis or small-vessel occlusion) + age ≥ 50 years + cardiovascular risk factors | 112 | 70 | 70.5 | Clopidogrel 75 mg/day | 24–48 weeks treatment, FU 2 weeks after completion or discontinuation of treatment |

Independent laboratory (SRL Mediserch Inc) NR |

EM–IM–PM |

| Li, 2017 [29] | Cohort | China | 2012–2016 | Acute IS | 196 | 62.9 | 82.1 | Clopidogrel 75 mg/day | 6 months |

ABI 3730 *2, *3 |

*2 LOF–no LOF |

| Li, 2021 [30] | Cohort | China | 2016–2019 | Cerebrovascular stent due to atherosclerotic stenosis or occlusion of the internal carotid artery, subclavian artery, vertebral artery or intracranial arteries | 154 | 61.2 | 81.8 |

Clopidogrel 75 mg/day + aspirin 100 mg/day In case of aspirin intolerance: cilostazol 200 mg/d |

6 months |

PCR-RFLP *2, *3 |

EM–IM–PM |

| Lin, 2018* [31] | Cohort | China | 2014–2015 | Acute IS | 375 | 69 | 63.8 |

Clopidogrel 75 mg/day Minor IS or symptomatic carotid or intracranial artery stenosis: clopidogrel 75 mg/day + aspirin 200 mg/day for 2 weeks, followed by clopidogrel 75 mg/day |

10 days |

MALDI-TOF MS *2, *3 |

*2 LOF–no LOF |

| Lin, 2021 [32] | Cohort | China | 2016–2017 | IS | 89 | 65.1 | 57.3 | Clopidogrel ± aspirin | 12 months |

Unknown *2, *3 |

LOF–no LOF |

| Liu, 2020 [33] | Cohort | China | 2015–2018 | Acute IS | 289 | 66.6 | 58.1 | Clopidogrel 75 mg/day | 6 months (mean) |

CYP2C19 genotyping kit (Shanghai, China) (DNA Microarray) *2, *3 |

EM–IM–PM |

| Lv, 2021 [34] | Cohort | China | 2012–2013 | Acute IS | 311 | 67.9 | 68.5 | Clopidogrel 75 mg/day | 54 months |

Sequenom MassARRAY iPLEX platform *2, *3, *4, *5, *7, *8, *17 |

EM–IM–PM (ultrarapid excluded, unknown included) |

| McDonough, 2015 [35] | Post hoc analysis RCT (SPS3) | North America, Latin America, Spain | Symptomatic small subcortical stroke or TIA | 493 | 62.5 | 62 | Clopidogrel 75 mg/day + aspirin 325 mg/day | 3.4 years (mean) |

TaqMan *2, *17 |

UM–EM versus IM-PM | |

| Meschia, 2020 [36] | Post hoc analysis RCT (POINT) | North America, Europe | Minor IS or high-risk TIA | 282 | 62.5 (median) | 56.4 | Clopidogrel 75 mg/day + aspirin 50–325 mg/day | 90 days |

TaqMan *2, *3, *17 |

EM–IM–PM (ultrarapid and unknown excluded) |

|

| Ni, 2017 [37] | Cohort | China | 2012–2014 | Acute IS | 191 | 61.5 | 67 | Clopidogrel | 9.5 months (mean) |

iMIDR *2, *3 |

EM–IM–PM |

| Patel, 2022 [38] | Cohort | USA |

Carotid artery stenosis without cerebral infarction: 1. Medical therapy cohort 2. Procedural cohort (endarterectomy or stenting) |

Medical therapy cohort: 743 Procedural cohort: 60 |

Medical therapy cohort: 67.9 (median) Procedural cohort: 67.2 (median) |

Medical therapy cohort: 63.5 Procedural cohort: 68.3 |

Clopidogrel + aspirin | 2.8 years (median) |

Unknown *2, *3, *4, *5, *6, *7, *8, *17 |

EM–IM–PM (ultrarapid excluded, unknown included) | |

| Qiu, 2015 [39] | Cohort | China | 2012–2013 | Acute IS | 198 | 67.1 | 55.6 | Clopidogrel 75 mg/day | 6 months |

PCR-RELP *2, *3 |

LOF–no LOF |

| Sen, 2014 [40] | Cohort | Turkey | Acute ischemic cerebrovascular disease | 51 | 66.4 | 41.2 | Clopidogrel 75 mg/day | 12 months |

LightCycler 2.0 *2, *3 |

EM–IM–PM | |

| Spokoyny, 2014 [41] | Cohort | USA | 2010–2012 | Stroke or TIA | 43 | 69.6 | 53.4 | Clopidogrel | NR |

Unknown NR |

EM–IM–PM Indeterminate and mixed ultrarapid/poor excluded |

| Sun, 2015 [42] | Cohort | China | 2008–2010 | First-ever IS | 625 | 61.6 | 74.4 | Clopidogrel 75 mg/day | 12.7 months (mean) |

iMLDR *2, *3, *17 |

LOF–no LOF |

| Tomek, 2018 [43] | Cohort | Czech Republic | 2010–2015 | Acute IS | 72 | 64.5 | 60 | Clopidogrel | 14.9 months (mean) |

LightScanner *2, *17 |

EM–IM Ultrarapid and unknown excluded. PM in article excluded. |

| Tornio, 2017 [44] | Cohort | Scotland | 1997–2007 | Hospitalization for IS | 94 | 74 | 62 | Clopidogrel | 24 months |

Unknown *2 |

EM–IM–PM |

| Wang, 2016 [45] | Cohort | China | 2009–2011 | IS | 321 | 62 | 75.5 | Clopidogrel | 12 months |

iMLDR *2, *3, *4, *5, *6, *7, *8 |

LOF–no LOF |

| Wang, 2016 (CHANCE) [47] | Post hoc analysis RCT | China | 2010–2012 | Acute minor IS or TIA | 1463 | 62.7 (median) | 66.9 | Clopidogrel 75 mg/day [3 months] + aspirin 75 mg/day [21 days] | 90 days |

Sequenom MassARRAY iPLEX platform *2, *3, *17 |

MACE + all strokes + all bleeding: EM–IM–PM (ultrarapid and unknown excluded) Other EP’s: LOF–no LOF |

| Wang, 2019 [46] | Post hoc analysis RCT (PRINCE) | China | 2015–2017 | Acute minor IS or moderate to high-risk TIA | 329 | 60.4 | 73.3 | Aspirin 100 mg/day (until day 21) + clopidogrel 75 mg/day (until day 90) | 1 year |

Sequenom MassARRAY iPLEX platform If results inconclusive: ABI 3500 *2, *3, *17 |

MACE + all strokes: EM–IM–PM (ultrarapid and unknown excluded) Other EP’s: LOF–no LOF |

| Won Han, 2017 [51] | Post hoc analysis RCT (MAESTRO) | South Korea | 2010–2014 | First time noncardiogenic IS | 393 | 61 | 67 | Clopidogrel 75 mg/day | 2.7 years (median) |

Seeplex CYP2C19 ACE genotyping system or Real-Q CYP2C19 genotyping kit *2, *3, *17 |

IS + all strokes: EM–IM–PM Other EP’s: UM–EM versus IM–PM–unknown |

| Yi 2016* [49] | Cohort | China | 2014–2015 | Acute IS | 514 | 68.6 | 65.2 |

Clopidogrel 75 mg/day Minor IS or symptomatic carotid or intracranial artery stenosis: clopidogrel 75 mg/day + aspirin 200 mg/day for 2 weeks, followed by clopidogrel 75 mg/day |

6 months |

MALDI-TOF MS *2, *3 |

*2 LOF–no LOF |

| Yi, 2018 [48] | Post hoc analysis RCT | China | 2009–2011 | Acute large-artery atherosclerosis IS | 284 | 69.2 | 54.9 | Aspirin 200 mg/day + clopidogrel 75 mg/day for 30 days, followed by clopidogrel 75 mg/day | 5 years |

MALDI-TOF MS *2 |

LOF–no LOF |

| Zhu, 2016 [50] | Cohort | China | 2012–2014 | IS and carotid artery stenting | 241 | 64.3 | 90 |

3–5 days before intervention until 3 months after intervention (at least 1 month): clopidogrel 75 mg/day + aspirin 100 mg/day Long-term: clopidogrel 75 mg/day |

1 year |

Commercially available kit (BaiO Technology Co) *2, *3 |

EM–IM–PM |

IS, ischemic stroke; TIA, transient ischemic attack; ICAD, intracranial atherosclerotic disease; RCT, randomized controlled trial; NR, not reported

*Lin 2018 and Yi 2016 included patients from the same study population but described other study endpoints: Lin 2018 ischemic stroke and all bleeding, Yi 2016 MACE

The 22 cohort studies contained a total of 5182 patients (range 42–743), and the seven post hoc analyses of RCTs contained 3356 patients (range 112–1463). In seven studies, both ischemic stroke and TIA patients were included [27, 28, 35, 36, 41, 46, 47]. One of these studies specified ischemic stroke as symptomatic small subcortical stroke [35]. Two studies only included patients who received a cerebrovascular stent because of atherosclerotic stenosis [30, 50]. In the study of Patel et al., only patients with asymptomatic extracranial carotid artery stenosis were included, and these patients were divided in a medical therapy cohort and a procedural cohort [38]. In the remaining 19 studies, only patients with history of ischemic stroke were included [25, 26, 29, 31–34, 37, 39, 40, 42–45, 48, 49, 51]. Definitions of MACE and bleeding differed among the included studies (Table 4).

Table 4.

Definitions of outcome measurements in studies on stroke or TIA

| Study | MACE | All bleeding | Major bleeding |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fu, 2020 | 1, 2, 3, 4 | – | – |

| Fukuma, 2022 | – | – | 1, 2, 3 |

| Hoh, 2015 | 1, 2, 4, 5 | – | – |

| Kitazono, 2023 | 1, 3, 9 | – | – |

| Li, 2017 | 3, 6, 7 | – | – |

| Li, 2021 | 2, 3, 4, 8 | – | 4, 5 |

| Lin, 2018 | – | 1, 2, 3 | – |

| Lin, 2021 | – | Not further specified | – |

| Lv, 2021 | 1, 3, 4, 9 | – | – |

| McDonough, 2015 | – | – | 6 |

| Meschia, 2020 | 1, 3, 9 | – | 1, 7, 8, 9, 10 |

| Ni, 2017 | 1, 3, 9 | – | – |

| Qiu, 2015 | 1, 3, 9 | – | – |

| Sun, 2015 | 1, 3, 9 | 4 | – |

| Tomek, 2018 | 1, 3, 4, 9 | 5 | 11 |

| Tornio, 2017 | 2, 10 | – | – |

| Wang, 2016 | 1, 3, 9 | – | – |

| Wang, 2016 (CHANCE) | 1, 5, 9 | 4 | 12 |

| Wang, 2019 | 1, 4, 5, 9 | 6 | 13 |

| Won Han, 2017 | 1, 5, 9 | Not further specified | – |

| Yi, 2016 | 1, 3, 9 | – | – |

| Yi, 2018 | 1, 2, 3, 4 | – | – |

| Zhu, 2016 | 2, 8, 11, 12, 13 | – | – |

MACE: major adverse cardiovascular events: 1 = myocardial infarction; 2 = death; 3 = (recurrence of) ischemic stroke; 4 = TIA; 5 = stroke; 6 = progressive ischemic stroke (an increase of NIHSS score ≥ 2) during admission; 7 = other ischemic diseases; 8 = stent thrombosis; 9 = (cardio)vascular death; 10 = hospitalization for an arterial thrombo-occlusive event (myocardial infarction, ischemic stroke, peripheral arterial disease); 11 = previous ischemic symptom recurrence; 12 = previous cerebrovascular transient ischemic attack; 13 = new cerebral infarction caused by previous cerebrovascular

All bleeding: 1 = symptomatic or asymptomatic hemorrhagic transformation; 2 = symptomatic or asymptomatic intracerebral hemorrhage; 3 = extracranial hemorrhages; 4 = GUSTO; 5 = ISTH; 6 = PLATO (major, minor or minimal bleeding)

Major bleeding: 1 = (symptomatic) intracranial hemorrhage; 2 = symptomatic bleeding (such as intraspinal, intraocular, retroperitoneal, intra-articular, pericardial or intramuscular bleeding with compartment syndrome); 3 = episodes that caused ≥ 2 g/dL decline in hemoglobin level or required at least 280 ml of red cell transfusion; 4 = gastro-intestinal hemorrhage; 5 = hemorrhagic stroke; 6 = major extracranial hemorrhage defined as serious or life-threatening bleeding requiring transfusion of red cells or surgery, or resulting in permanent functional sequelae or death; 7 = intraocular hemorrhage causing vision loss; 8 = transfusion of ≥ 2 units of red blood cells or an equivalent of whole blood; 9 = hospitalization or prolongation of an existing hospitalization; 10 = death due to hemorrhage; 11 = ISTH; 12 = GUSTO severe bleeding; 13 = PLATO

Risk of Bias Assessment

The mean NOS score of included studies was 7.2 (Table 5). A total of 22 studies were scored as high quality studies (NOS score ≥ 7); 4 of these 22 studies were rated with the highest NOS score of 9. Seven studies had a NOS score < 7.

Table 5.

Quality assessment (Newcastle–Ottawa Scale score) of studies on stroke or TIA

| Study | Selection | Comparability | Outcome | Total score | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Representativeness of the exposed cohort | Selection of the nonexposed cohort | Ascertainment of exposure | Demonstration that outcome of interest was not present at start of study | Comparability of cohorts based on the design or analysis | Assessment of outcome | Was follow-up long enough for outcomes to occur | Adequacy of follow-up of cohorts | ||

| Al-Rubaish, 2022 | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | 5 | |||

| Fu, 2020 | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★★ | 7 | ||

| Fukuma, 2022 | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★★ | ★ | ★ | 8 | |

| Hoh, 2015 | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★★ | ★ | 6 | |||

| Jardaq, 2022 | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | 6 | ||

| Kitazono, 2023 | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | 5 | |||

| Li, 2017 | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★★ | ★ | ★ | 8 | |

| Li, 2021 | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★★ | ★ | ★ | 8 | |

| Lin, 2018 | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★★ | ★ | 7 | ||

| Lin, 2021 | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | 9 |

| Liu, 2020 | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★★ | ★ | 7 | ||

| Lv, 2021 | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★★ | ★ | ★ | 8 | |

| McDonough, 2015 | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | 9 |

| Meschia, 2020 | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★★ | ★ | 7 | ||

| Ni, 2017 | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★★ | ★ | ★ | 8 | |

| Patel, 2022 | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★★ | ★ | ★ | 8 | |

| Qiu, 2015 | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★★ | ★ | ★ | 8 | |

| Sen, 2014 | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | 4 | ||||

| Spokoyny, 2014 | ★ | ★ | ★ | 3 | |||||

| Sun, 2015 | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★★ | ★ | ★ | 8 | |

| Tomek, 2018 | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | 8 |

| Tornio, 2017 | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★★ | ★ | 7 | ||

| Wang, 2016 | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | 9 |

| Wang, 2016 (CHANCE) | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★★ | ★ | ★ | 8 | |

| Wang, 2019 | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | 7 | |

| Won Han, 2017 | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | 6 | ||

| Yi, 2016 | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★★ | ★ | ★ | 8 | |

| Yi, 2018 | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | 9 |

| Zhu, 2016 | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★★ | ★ | ★ | 7 | ||

Clinical Outcomes

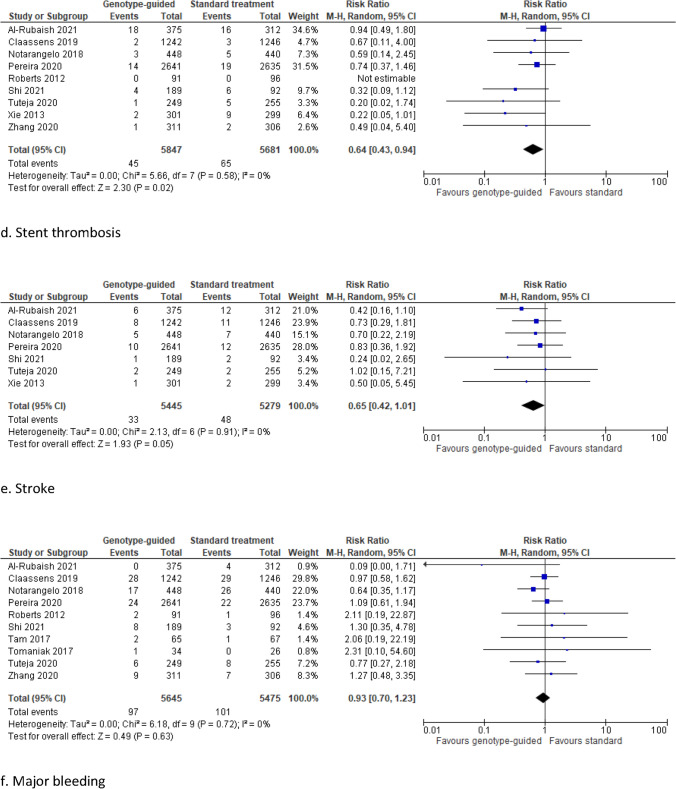

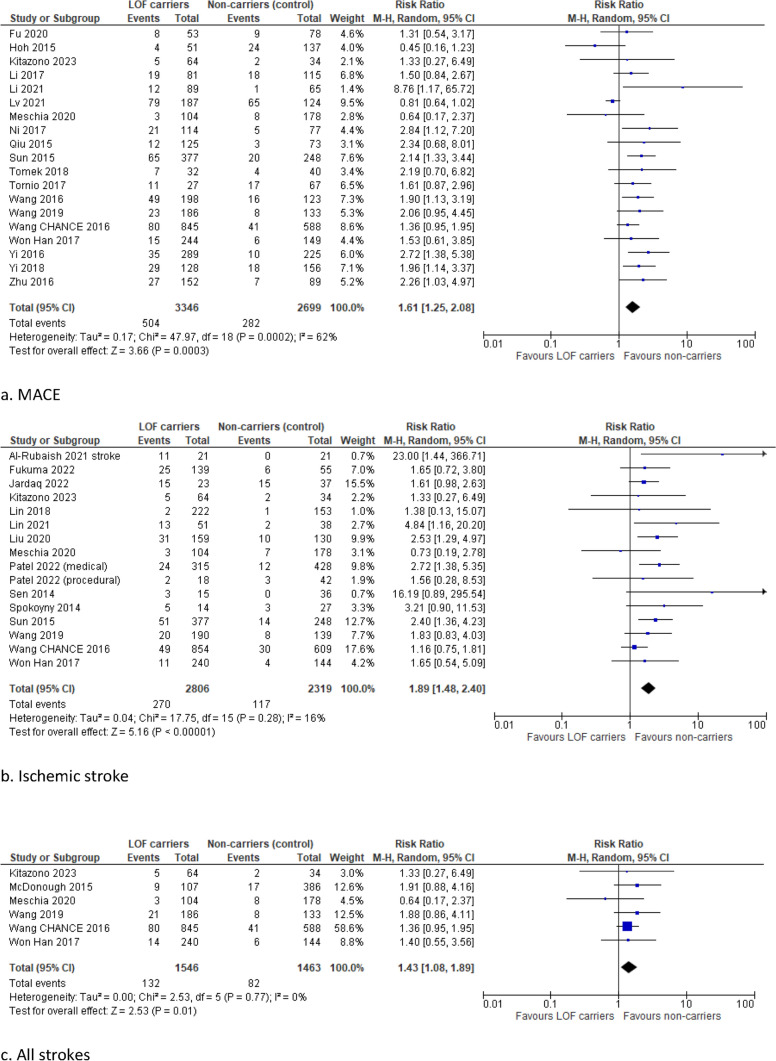

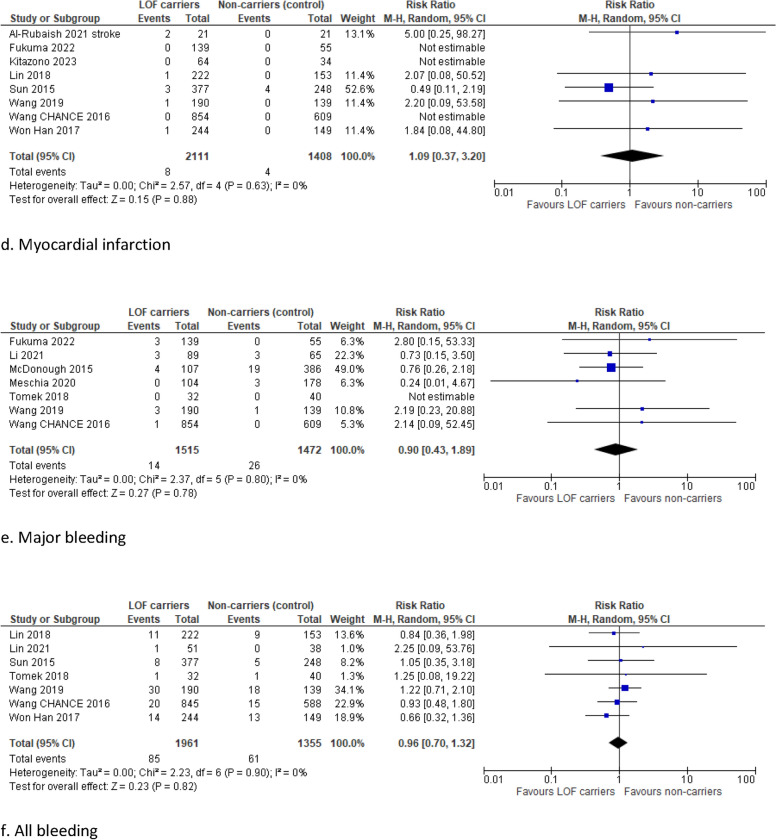

Carriers of a LOF allele had a significantly higher risk of MACE compared with non-carriers (RR 1.61, 95% CI 1.25–2.08, I2 62%) (Fig. 4). Moreover, the risk of ischemic stroke and all strokes was significantly higher in LOF carriers than in non-carriers (RR 1.89, 95% CI 1.48–2.40, I2 16% and RR 1.43, 95% CI 1.08–1.89, I2 0%, respectively).

Fig. 4.

Forest plots for the ischemic and bleeding outcomes in studies on stroke or TIA

No significant differences were found in the risk of myocardial infarction (RR 1.09, 95% CI 0.37–3.20, I2 0%), major bleeding (RR 0.90, 95% CI 0.43–1.89, I2 0%), and all bleeding (RR 0.96, 95% CI 0.70–1.32, I2 0%). Subanalyses including only high-quality studies with a NOS score ≥ 7, studies with a duration of follow-up longer than 12 months, and only the post hoc analyses of RCTs demonstrated robust results (Supplementary Figs. 5, 6, and 7).

RCTs Including Only LOF Carriers: Description of Main Results

In our full-text screening, two RCTs involving only CYP2C19 LOF carriers were identified. The CHANCE-2 trial was a double-blind, placebo-controlled RCT among mainly Han Chinese patients (98%) with an acute minor ischemic stroke (NIHSS score ≤ 3) or high-risk TIA (ABCD2 score ≥ 4) [52]. Patients were randomized to receive ticagrelor or clopidogrel through day 90. All patients received aspirin for 21 days. A total of 3205 patients were assigned to the ticagrelor group and 3207 to the clopidogrel group. Patients who were treated with ticagrelor-aspirin had a significantly lower risk of a new ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke within 90 days compared with patients with clopidogrel–aspirin [6.0% versus 7.6% respectively; hazard ratio (HR) 0.77, 95% CI 0.64–0.94]. Ticagrelor increased the risk of any bleeding compared with clopidogrel (5.3% versus 2.5% respectively, HR 2.18, 95% CI 1.66–2.85). A post hoc analysis showed that these bleedings were generally mild and occurred mostly in the first 21 days after randomization [53]. No significant differences were found in the risk of severe or moderate bleeding (both 0.3%, HR 0.82, 95% CI 0.34–1.98) [52].

Another RCT included only single CYP2C19 LOF carriers (*1/*2, *1/*3) with an acute minor ischemic stroke (NIHSS score ≤ 5) and moderate-to-severe cerebral artery stenosis (> 50%). Patients were randomly assigned to receive a combination of high dose clopidogrel (150 mg per day) and aspirin (100 mg per day) or a combination of normal dose clopidogrel (75 mg per day) and aspirin (100 mg per day). After the first 21 days, clopidogrel was stopped and monotherapy with aspirin was continued during the 90-day observation period. In total, 62 patients with high dose clopidogrel and 69 patients with normal dose clopidogrel were analyzed. No significant differences in the vascular event rate were found between these two treatment groups [54].

RCT Comparing Genotype-Guided with Standard Treatment

Our full-text screening identified one RCT that compared a personalized genotype-guided treatment strategy with standard treatment. In this RCT, 650 adult patients with a mild-to-moderate acute noncardioembolic ischemic stroke (NIHSS ≤ 5) or a moderate-to-high risk TIA (ABCD2 score ≥ 4) were included from 2019 to 2021 in China [55]. Patients were randomized in a pharmacogenetic or standard treatment group. In the pharmacogenetic group, all patients were treated with aspirin (until day 90). Ultrarapid (*17/*17), rapid (*1/*17), and extensive (*1/*1) metabolizers were also treated with clopidogrel 75 mg/day, intermediate (*1/*2, *1/*3, *17/*2, *17/*3) metabolizers with clopidogrel 150 mg/day, and poor (*2/*2, *2/*3, *3/*3) metabolizers with ticagrelor 90 mg twice daily (until day 21). The standard group was treated with aspirin (until day 90) and clopidogrel 75 mg/day (until day 21). After a 90-day follow-up, patients in the pharmacogenetic group had a significantly lower risk of new stroke (RR 0.27, 95% CI 0.08–0.97) and composite vascular events (RR 0.38, 95% CI 0.16–0.92). No differences in major bleeding were found between treatment groups (RR 1.50, 95% CI 0.25–8.95) [55].

Peripheral Arterial Disease

After full-text screening, four studies were eligible for inclusion: a retrospective study [56], a prospective study [57], a conference abstract [58], and a research letter describing the results from an RCT substudy [59]. Due to the low number of studies and the heterogeneity in study design, the main results of each study are described separately.

Lee et al. retrospectively analyzed the association between CYP2C19 genetic profiles and clinical outcomes (major amputation free survival and all-cause mortality) in a cohort of Taiwanese patients with critical limb ischemia treated with clopidogrel after endovascular treatment [56]. All patients had a Rutherford classification of V or VI. A total of 278 patients were included: 153 EMs, 79 IMs, and 46 PMs. Significant differences in the estimated amputation free 12-month survival rates (EM 82.1%, IM 66.1%, PM 56.6%) and overall one year survival rate (EM 83.7%, IM 72.2%, PM 71.3%) were found between the different types of metabolizers. Moreover, the gene polymorphism number had a significant negative association with the clinical outcomes in a multivariable analysis.

In the prospective study from Guo et al, 50 patients with peripheral arterial disease in the superficial femoral artery (TASC II A–C) in whom successful recanalization was achieved by endovascular therapy were included [57]. Of these 50 patients, 26 were LOF carriers. The risk of in-stent restenosis or occlusion was significantly higher in LOF carriers compared with non-carriers. The primary patency rate at 12 months was 73.1% in non-carriers compared with 34.6% in LOF carriers. Also after adjustment for confounding factors, CYP2C19 genotypic classification was an independent risk factor for the occurrence of in-stent restenosis or occlusion.

In a study among 72 patients with peripheral arterial disease treated with clopidogrel after percutaneous transluminal angioplasty, a significant association between carriage of CYP2C19 LOF alleles and the occurrence of atherothrombotic ischemic events was found in the univariate analysis [odds ratio (OR) 4.49, 95% CI 1.45–13.84, p = 0.009] and multivariate analysis (OR 4.89, 95% CI 1.32–12.83, p = 0.018) [58].

Lastly, the EUCLID trial was an RCT involving 13.885 patients with symptomatic PAD who were assigned to receive ticagrelor or clopidogrel [59]. Of the 6955 patients treated with clopidogrel, 2873 were non-carriers, 1596 had one LOF allele, 10 had two LOF alleles, 1676 had one gain-of-function allele, 342 had two gain-of-function alleles, and 458 had a combination of one gain-of-function and one LOF allele. No differences in the rate of the primary composite endpoint (cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction or ischemic stroke) or TIMI major bleeding were found between these CYP2C19 polymorphism subgroups [59].

Discussion

This systematic review and meta-analysis investigates the impact of CYP2C19 genotype status on the rate of adverse arterial thrombotic events in the most common types of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. In patients with coronary artery disease, mostly undergoing PCI, genotype-guided treatment significantly reduced the risk of MACE, myocardial infarction and stent thrombosis, while the rate of major bleeding remained unchanged. In patients with history of stroke treated with clopidogrel, LOF allele carriage was associated with a higher risk of MACE and stroke compared with noncarriage. For PAD, it remains unclear whether LOF allele carriage is associated with the risk of thrombotic limb events in patients treated with clopidogrel.

Coronary artery disease, carotid artery disease, and peripheral arterial disease are all clinical manifestations of atherosclerosis and thus share the same underlying pathophysiological mechanisms [60]. In these patients, antiplatelet therapy is widely prescribed for the secondary prevention of atherothrombotic events. The specific regimen of antiplatelet therapy used in these different atherosclerotic diseases slightly differs but commonly exists of a P2Y12 inhibitor ± acetylsalicylic acid. In symptomatic peripheral arterial disease, international guidelines recommend the use of monotherapy with clopidogrel over acetylsalicylic acid [61–63]. For patients with a stroke or TIA, the current guidelines advise acetylsalicylic acid or clopidogrel monotherapy or the combination of acetylsalicylic acid and dipyridamole [64]. Guidelines on acute coronary syndrome advise the use of dual antiplatelet therapy with acetylsalicylic acid and prasugrel or ticagrelor over clopidogrel [65]. However, clopidogrel is globally still frequently prescribed in these patients. In the guideline and updated expert consensus statement (2019) of the European Society of Cardiology, the routine use of CYP2C19 genotyping in clinical practice is not recommended because of the lack of robust scientific evidence [66]. In selected patients, however, genotyping can be used in combination with clinical risk factors and platelet function tests to aid in the decision whether treatment should be escalated or de-escalated [66]. The last guideline for the management of acute coronary syndromes from the European Society of Cardiology (2023) includes the use of genetic testing to guide de-escalation of P2Y12 receptor inhibitor treatment after PCI as one of the research gaps that should be addressed in the following years [67]. In a recent real-world study in 2751 elderly patients (> 65 years) carrying a CYP2C19 LOF variant who underwent PCI after ACS, a similar rate of ischemic events and a higher bleeding rate was observed in patients who were treated with ticagrelor compared with clopidogrel. These results emphasize that more research data are needed to answer the question how to integrate genotyping, platelet function tests and clinical risk factors in clinical decision making [68]. The guidelines on carotid artery disease and peripheral arterial disease do not contain recommendations about the use of CYP2C19 genotyping [69].

The results of our meta-analysis demonstrate that the CYP2C19 genotype status can be used to reduce the rate of adverse arterial thrombotic events in selected patient groups. Most evidence exists for patients with coronary artery disease, specifically for patients who underwent PCI in whom the risk of MACE, myocardial infarction and stent thrombosis were all reduced by the use of genotype-guided treatment. In patients with stroke or TIA, only few studies included patients who received a carotid stent or underwent a carotis endarterectomy. In three of four included studies on peripheral arterial disease, the study population was treated with a revascularization procedure. In all these studies, CYP2C19 LOF allele carriage was a risk factor for the occurrence of atherothrombotic events. In the EUCLID trial, no differences in ischemic or bleeding endpoints were found between the different CYP2C19 polymorphism subgroups. In the clopidogrel-treated arm of this study, however, only 57% underwent a revascularization procedure. The remaining patients had an ankle–brachial index of 0.80 or lower at screening. From these results in patients with coronary artery disease or peripheral arterial disease, it can be hypothesized that CYP2C19 genotyping is especially of additional value in patients who underwent a revascularization procedure for their atherosclerotic disease.

Currently, there is much debate whether CYP2C19 genotype status should be determined in all “new” patients with atherosclerotic disease. However, in the future, an enlarging number of patients will already know their CYP2C19 genotype status before they present to the emergency department or outpatient clinic with atherosclerotic disease as genetic testing is becoming more easily available. Irrespective of the discussion whether CYP2C19 genotyping should be performed, clinical guidelines on the management of patients with a known CYP2C19 genotype should be available. Recently, the Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) updated their guideline including recommendations on the management of the different CYP2C19 metabolizer types with coronary artery disease, cerebrovascular disease and peripheral arterial disease [1].

The impact of CYP2C19 genotyping can be different according to the type of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. The latest guidelines on acute coronary syndrome recommend the use of ticagrelor or prasugrel over clopidogrel [67]. Therefore, in these patients, CYP2C19 genotyping could be used as de-escalation strategy with the use of clopidogrel in non-carriers and prasugrel or ticagrelor (if no contraindications) for all other patients. For patients with stroke and PAD, the “standard therapy” is clopidogrel. In these patients, CYP2C19 genotyping can be used to escalate antithrombotic treatment. For patients with stroke, alternative P2Y12 inhibitors are ticagrelor and ticlopidine. Patients with a history of stroke or TIA have a contraindication for prasugrel [1]. For patients with PAD, genotype-guided escalation strategies are currently under investigation. The ongoing GENPAD trial does not use ticagrelor or prasugrel but explores the beneficial effects of double dose clopidogrel for intermediate metabolizers and acetylsalicylic acid plus rivaroxaban for poor metabolizers [11].

Only 5–12% of the variation in clopidogrel response is explained by the CYP2C19*2 genotype [70–72]. Clinical characteristics (such as age, BMI, adherence, and comorbidity), use of comedication, and additional polymorphisms in other genes might also affect the response to clopidogrel. Most of the variability in clopidogrel response is, however, still unexplained. Future research should focus on the identification of other relevant factors that influence the response to clopidogrel. However, at this moment carriage of the loss-of-function CYP2C19*2 variant is the most important known determinant of the residual platelet aggregation on clopidogrel.

A great strength of this meta-analysis is that it provides an overview of all (recent) studies on the relationship between CYP2C19 polymorphisms and clinical outcomes in patients with one of the three most common types of atherosclerotic disease simultaneously. The meta-analysis was performed in accordance with PRISMA guidelines, and it was preregistered in PROSPERO. For each included study the same definitions were used for LOF carriers and non-carriers. However, our study also has some limitations. First, substantial heterogeneity was found for MACE in studies on coronary artery disease and cerebrovascular disease and for cardiovascular death in studies on coronary artery disease. Second, different definitions of MACE and major bleeding were used in the included studies. In general, MACE was used as a composite outcome including cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, and/or stroke. Broader definitions including relevant endpoints (such as stent thrombosis, severe recurrent ischemia, revascularization, all-cause death, major bleeding, and readmission to hospital) were also accepted. Because we selected the definitions that most closely resembled the general definition of MACE and we included only the relevant endpoints for this meta-analysis, we do not expect that the differences in definitions influenced our study outcomes. For major bleeding, different definitions according to the most frequently used and globally accepted classification schemes were used (PLATO, BARC, TIMI). Third, the classification of patients according to CYP2C19 genotype status differed among studies. In some studies, the patient cohort was divided in extensive, intermediate and poor metabolizers, while in other studies information on the number of CYP2C19 LOF alleles was lacking as patients were only classified as LOF carrier or non-carrier. Therefore, we unfortunately were not able to explore a potential association between clinical outcomes and the number of CYP2C19 LOF alleles. Fourth, the dosage and type of drugs used in the genotype-guided and standard treatment groups differed (slightly) between studies. Fifth, the length of follow-up differed between studies. Compared with the overall analysis, separate subgroup analyses based on studies with a follow-up duration of 12 months or more in patients with coronary artery disease and cerebrovascular disease demonstrated robust results for our primary outcomes. Sixth, in the majority of stroke studies, the type of ischemic stroke was not further specified or clinical outcomes were not reported separately for each stroke subtype. Finally, RCTs comparing a genotype-guided antithrombotic treatment with standard treatment were only available in patients with coronary artery disease. These RCTs are not performed in patients with peripheral arterial disease and are scarce in patients with cerebrovascular disease. For these patient categories, we used the best evidence that is currently available: cohort studies and post hoc analyses of RCTs describing the association between CYP2C19 genotype status and clinical outcome measurements. The pooled results of all RCTs comparing genotype-guided and standard antithrombotic treatment (i.e., all RCTs in CAD and one RCT in stroke) were comparable to the analyses described in individual indications (Supplementary Fig. 8A–E).

For patients with cerebrovascular disease, this is the first meta-analysis in recent years on the relationship between CYP2C19 genotype status and clopidogrel response. The last meta-analysis on this subject was published in 2017 by Pan et al. [10], but numerous new studies have been published since. The least evidence was available for peripheral arterial disease. However, our study is the first that included the results of a post hoc analysis of the EUCLID study. It is important to note that this post-hoc analysis did not include major adverse limb events.

In the future, (more) large RCTs comparing genotype-guided antithrombotic treatment with standard treatment are also required in patients with conservatively treated coronary artery disease and cerebrovascular disease. In recent years, one RCT comparing genotype-guided with standard treatment was conducted among patients with cerebrovascular disease, showing promising results [55]. The efficacy of a CYP2C19 genotype-guided treatment strategy in comparison to conventional clopidogrel treatment in patients with peripheral arterial disease is currently being investigated in the ongoing GENPAD trial [11].

In conclusion, genotype-guided treatment significantly decreased the rate of adverse atherothrombotic events in patients with coronary artery disease, mostly undergoing PCI. In patients with history of stroke, LOF carriers who were treated with clopidogrel had a higher risk of MACE and stroke. The evidence in peripheral arterial disease is limited but CYP2C19 LOF carriage seemed to be a risk factor for adverse events in patients who underwent a revascularization procedure. In the future, large RCT’s comparing genotype-guided treatment with standard treatment are required, particularly in stroke and peripheral arterial disease, to give accurate management recommendations and to optimize care for these patients.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

This work was presented at the ESC23 and published as abstract in a Supplement of the European Heart Journal in Nov 23.

Declarations

Funding

No external funds were used to support this work.

Conflicts of Interest

D.P.M.S.M.M., L.H.W., J.K., C.K., and M.C.W. declare that they have no potential conflicts of interest that might be relevant to the contents of this manuscript.

Data Availability

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Authors’ Contributions

D.P.M.S.M.M., L.H.W., J.K., C.K., and M.C.W. contributed to the concept of the study and the study design. D.P.M.S.M.M., L.H.W., and M.C.W. contributed to the data search. D.P.M.S.M.M., L.H.W., and M.C.W. contributed to the data selection and data extraction. D.P.M.S.M.M., L.H.W., and M.C.W. contributed to the quality assessment. All authors contributed to the interpretation of the data. D.P.M.S.M.M., L.H.W., J.K., and M.C.W. wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed by editing the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics Approval

Not applicable.

Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

References

- 1.Lee CR, Luzum JA, Sangkuhl K, et al. Clinical pharmacogenetics implementation consortium guideline for CYP2C19 genotype and clopidogrel therapy: 2022 update. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2022;112(5):959–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mega JL, Close SL, Wiviott SD, et al. Cytochrome p-450 polymorphisms and response to clopidogrel. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(4):354–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Castrichini M, Luzum JA, Pereira N. Pharmacogenetics of antiplatelet therapy. Ann Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2023;63:211–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sorich MJ, Rowland A, McKinnon RA, et al. CYP2C19 genotype has a greater effect on adverse cardiovascular outcomes following percutaneous coronary intervention and in Asian populations treated with clopidogrel: a meta-analysis. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2014;7(6):895–902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Niu X, Mao L, Huang Y, et al. CYP2C19 polymorphism and clinical outcomes among patients of different races treated with clopidogrel: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Huazhong Univ Sci Technol Med Sci. 2015;35(2):147–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tang B, Wang X, Wang X, et al. Genotype-guided antiplatelet therapy versus standard therapy for patients with coronary artery disease: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2022;25:9–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Galli M, Benenati S, Capodanno D, et al. Guided versus standard antiplatelet therapy in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2021;397(10283):1470–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pereira NL, Rihal C, Lennon R, et al. Effect of CYP2C19 Genotype on ischemic outcomes during oral P2Y(12) inhibitor therapy: a meta-analysis. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2021;14(7):739–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kheiri B, Abdalla A, Osman M, et al. Personalized antiplatelet therapy in patients with coronary artery disease undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: a network meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2019;94(2):181–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pan Y, Chen W, Xu Y, et al. Genetic polymorphisms and clopidogrel efficacy for acute ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Circulation. 2017;135(1):21–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kranendonk J, Willems LH, Vijver-Coppen RV, et al. CYP2C19 genotype-guided antithrombotic treatment versus conventional clopidogrel therapy in peripheral arterial disease: study design of a randomized controlled trial (GENPAD). Am Heart J. 2022;254:141–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sterne JAC, Savović J, Page MJ, et al. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2019;366: l4898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wells GA SB, O'Connell D, Peterson J, et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. Available from: http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp.

- 14.Al-Rubaish AM, Al-Muhanna FA, Alshehri AM, et al. Bedside testing of CYP2C19 vs. conventional clopidogrel treatment to guide antiplatelet therapy in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction patients. Int J Cardiol. 2021;343:15–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Claassens DMF, Vos GJA, Bergmeijer TO, et al. A genotype-guided strategy for oral P2Y(12) inhibitors in primary PCI. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(17):1621–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Notarangelo FM, Maglietta G, Bevilacqua P, et al. Pharmacogenomic approach to selecting antiplatelet therapy in patients with acute coronary syndromes: the PHARMCLO trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71(17):1869–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pereira NL, Farkouh ME, So D, et al. Effect of genotype-guided oral P2Y12 inhibitor selection vs conventional clopidogrel therapy on ischemic outcomes after percutaneous coronary intervention: the TAILOR-PCI randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2020;324(8):761–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roberts JD, Wells GA, Le May MR, et al. Point-of-care genetic testing for personalisation of antiplatelet treatment (RAPID GENE): a prospective, randomised, proof-of-concept trial. Lancet. 2012;379(9827):1705–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shi X, Zhang Y, Zhang Y, et al. Personalized antiplatelet therapy based on CYP2C19 genotypes in Chinese ACS patients undergoing PCI: a randomized controlled trial. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2021;8: 676954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tam CC, Kwok J, Wong A, et al. Genotyping-guided approach versus the conventional approach in selection of oral P2Y12 receptor blockers in Chinese patients suffering from acute coronary syndrome. J Int Med Res. 2017;45(1):134–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tomaniak M, Kołtowski Ł, Kochman J, et al. Can prasugrel decrease the extent of periprocedural myocardial injury during elective percutaneous coronary intervention? Pol Arch Intern Med. 2017;127(11):730–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tuteja S, Glick H, Matthai W, et al. Prospective CYP2C19 genotyping to guide antiplatelet therapy following percutaneous coronary intervention: a pragmatic randomized clinical trial. Circ Genom Precis Med. 2020;13(1): e002640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xie X, Ma YT, Yang YN, et al. Personalized antiplatelet therapy according to CYP2C19 genotype after percutaneous coronary intervention: a randomized control trial. Int J Cardiol. 2013;168(4):3736–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang M, Wang JR, Zhang Y, et al. Effects of individualized antiplatelet therapy based on CYP2C19 genotype and platelet function on the prognosis of patients after PCI. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2020;24(20):10753–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Al-Rubaish AM, Al-Muhanna FA, Alshehri AM, et al. Prevalence of CYP2C19*2 carriers in Saudi ischemic stroke patients and the suitability of using genotyping to guide antiplatelet therapy in a university hospital setup. Drug Metab Pers Ther. 2021;37(1):35–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fu H, Hu P, Ma C, et al. Association of clopidogrel high on-treatment reactivity with clinical outcomes and gene polymorphism in acute ischemic stroke patients: an observational study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2020;99(15): e19472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fukuma K, Yamagami H, Ihara M, et al. P2Y12 reaction units and clinical outcomes in acute large artery atherosclerotic stroke: a multicenter prospective study. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2022. 10.5551/jat.63369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hoh BL, Gong Y, McDonough CW, et al. CYP2C19 and CES1 polymorphisms and efficacy of clopidogrel and aspirin dual antiplatelet therapy in patients with symptomatic intracranial atherosclerotic disease. J Neurosurg. 2016;124(6):1746–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li W, Xie X, Wei D, et al. Baseline platelet parameters for predicting early platelet response and clinical outcomes in patients with non-cardioembolic ischemic stroke treated with clopidogrel. Oncotarget. 2017;8(55):93771–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li YJ, Chen X, Tao LN, et al. Association between CYP2C19 polymorphisms and clinical outcomes in patients undergoing stent procedure for cerebral artery stenosis. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):5974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lin J, Han Z, Wang C, et al. Dual therapy with clopidogrel and aspirin prevents early neurological deterioration in ischemic stroke patients carrying CYP2C19*2 reduced-function alleles. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2018;74(9):1131–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lin J, Mo Y, Cai D, et al. CYP2C19 polymorphisms and clopidogrel efficacy in the secondary prevention of ischemic stroke: a retrospective observational study. Ann Palliat Med. 2021;10(12):12171–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu G, Yang S, Chen S. The correlation between recurrent risk and CYP2C19 gene polymorphisms in patients with ischemic stroke treated with clopidogrel for prevention. Medicine (Baltimore). 2020;99(11): e19143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lv H, Yang Z, Wu H, et al. High on-treatment platelet reactivity as predictor of long-term clinical outcomes in stroke patients with antiplatelet agents. Transl Stroke Res. 2022;13(3):391–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McDonough CW, McClure LA, Mitchell BD, et al. CYP2C19 metabolizer status and clopidogrel efficacy in the Secondary Prevention of Small Subcortical Strokes (SPS3) study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2015;4(6): e001652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Meschia JF, Walton RL, Farrugia LP, et al. Efficacy of clopidogrel for prevention of stroke based on CYP2C19 allele status in the POINT trial. Stroke. 2020;51(7):2058–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ni G, Liang C, Liu K, et al. The effects of CES1A2 and CYP2C19 polymorphisms on responsiveness to clopidogrel and clinical outcomes among Chinese patients with acute ischemic stroke. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2017;10:3190–6. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Patel PD, Niu X, Shannon CN, et al. CYP2C19 loss-of-function associated with first-time ischemic stroke in non-surgical asymptomatic carotid artery stenosis during clopidogrel therapy. Transl Stroke Res. 2022;13(1):46–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Qiu LN, Sun Y, Wang L, et al. Influence of CYP2C19 polymorphisms on platelet reactivity and clinical outcomes in ischemic stroke patients treated with clopidogrel. Eur J Pharmacol. 2015;747:29–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sen HM, Silan F, Silan C, et al. Effects of CYP2C19 and P2Y12 Gene polymorphisms on clinical results of patients using clopidogrel after acute ischemic cerebrovascular disease. Balkan J Med Genet. 2014;17(2):37–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Spokoyny I, Barazangi N, Jaramillo V, et al. Reduced clopidogrel metabolism in a multiethnic population: prevalence and rates of recurrent cerebrovascular events. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2014;23(4):694–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sun W, Li Y, Li J, et al. Variant recurrent risk among stroke patients with different CYP2C19 phenotypes and treated with clopidogrel. Platelets. 2015;26(6):558–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tomek A, Matʼoška V, Frýdmanová A, et al. Impact of CYP2C19 polymorphisms on clinical outcomes and antiplatelet potency of clopidogrel in caucasian poststroke survivors. Am J Ther. 2018;25(2):e202–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tornio A, Flynn R, Morant S, et al. investigating real-world clopidogrel pharmacogenetics in stroke using a bioresource linked to electronic medical records. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2018;103(2):281–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang Y, Cai H, Zhou G, et al. Effect of CYP2C19*2 and *3 on clinical outcome in ischemic stroke patients treated with clopidogrel. J Neurol Sci. 2016;369:216–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang Y, Chen W, Lin Y, et al. Ticagrelor plus aspirin versus clopidogrel plus aspirin for platelet reactivity in patients with minor stroke or transient ischaemic attack: open label, blinded endpoint, randomised controlled phase II trial. BMJ. 2019;365: l2211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang Y, Zhao X, Lin J, et al. Association between CYP2C19 loss-of-function allele status and efficacy of clopidogrel for risk reduction among patients with minor stroke or transient ischemic attack. JAMA. 2016;316(1):70–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yi X, Lin J, Zhou J, Wang Y, et al. The secondary prevention of stroke according to cytochrome P450 2C19 genotype in patients with acute large-artery atherosclerosis stroke. Oncotarget. 2018;9(25):17725–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yi X, Zhou Q, Wang C, et al. Concomitant use of proton pump inhibitors and clopidogrel is not associated with adverse outcomes after ischemic stroke in Chinese population. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2016;25(12):2859–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhu WY, Zhao T, Xiong XY, et al. Association of CYP2C19 polymorphisms with the clinical efficacy of clopidogrel therapy in patients undergoing carotid artery stenting in Asia. Sci Rep. 2016;6:25478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Han SW, Kim YJ, Ahn SH, et al. Effects of triflusal and clopidogrel on the secondary prevention of stroke based on cytochrome P450 2C19 genotyping. J Stroke. 2017;19(3):356–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang Y, Meng X, Wang A, et al. Ticagrelor versus clopidogrel in CYP2C19 loss-of-function carriers with stroke or TIA. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(27):2520–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang A, Meng X, Tian X, et al. bleeding risk of dual antiplatelet therapy after minor stroke or transient ischemic attack. Ann Neurol. 2022;91(3):380–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wu H, Song H, Dou L, et al. Effectiveness and safety of high dose clopidogrel plus aspirin in ischemic stroke patients with the single CYP2C19 loss-of-function allele: a randomized trial. BMC Neurol. 2020;20(1):395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhang X, Jiang S, Xue J, et al. Personalized antiplatelet therapy guided by clopidogrel pharmacogenomics in acute ischemic stroke and transient ischemic attack: a prospective, randomized controlled trial. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13: 931405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lee J, Cheng N, Tai H, et al. CYP2C19 Polymorphism is associated with amputation rates in patients taking clopidogrel after endovascular intervention for critical limb ischaemia. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2019;58(3):373–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Guo B, Tan Q, Guo D, et al. Patients carrying CYP2C19 loss of function alleles have a reduced response to clopidogrel therapy and a greater risk of in-stent restenosis after endovascular treatment of lower extremity peripheral arterial disease. J Vasc Surg. 2014;60(4):993–1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Díaz-Villamarín X, Dávila-Fajardo CL, Blánquez-Martínez D, et al. 5PSQ-008 CYP2C19 SNP’s influence on clopidogrel response in peripheral artery disease patients 2019. A205.1-A p.

- 59.Gutierrez JA, Heizer GM, Jones WS, et al. CYP2C19 status and risk of major adverse cardiovascular events in peripheral artery disease: Insights from the EUCLID Trial. Am Heart J. 2020;229:118–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bauersachs R, Zeymer U, Brière JB, et al. Burden of coronary artery disease and peripheral artery disease: a literature review. Cardiovasc Ther. 2019;2019:8295054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Willems LH, Maas D, Kramers K, et al. Antithrombotic therapy for symptomatic peripheral arterial disease: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Drugs. 2022;82(12):1287–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Aboyans V, Ricco JB, Bartelink MEL, et al. 2017 ESC Guidelines on the DIAGNOSIS AND TREATMENT OF PERIPHERAL ARTERIAL DISEASES, IN COLLABORATION WITH The European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS): document covering atherosclerotic disease of extracranial carotid and vertebral, mesenteric, renal, upper and lower extremity arteriesEndorsed by: the European Stroke Organization (ESO)The Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Peripheral Arterial Diseases of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and of the European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS). Eur Heart J. 2018;39(9):763–816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gerhard-Herman MD, Gornik HL, Barrett C, et al. 2016 AHA/ACC Guideline on the management of patients with lower extremity peripheral artery disease: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2017;135(12):e686–725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Del Brutto VJ, Chaturvedi S, Diener HC, et al. Antithrombotic therapy to prevent recurrent strokes in ischemic cerebrovascular disease: JACC Scientific Expert Panel. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;74(6):786–803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Collet JP, Thiele H, Barbato E, et al. 2020 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation. Eur Heart J. 2021;42(14):1289–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sibbing D, Aradi D, Alexopoulos D, et al. updated expert consensus statement on platelet function and genetic testing for guiding P2Y(12) receptor inhibitor treatment in percutaneous coronary intervention. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2019;12(16):1521–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Byrne RA, Rossello X, Coughlan JJ, et al. 2023 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes. Eur Heart J. 2023;44(38):3720–826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zhang D, Li P, Qiu M, et al. Net clinical benefit of clopidogrel versus ticagrelor in elderly patients carrying CYP2C19 loss-of-function variants with acute coronary syndrome after percutaneous coronary intervention. Atherosclerosis. 2024;390: 117395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Naylor R, Rantner B, Ancetti S, et al. Editor’s Choice - European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS) 2023 clinical practice guidelines on the management of atherosclerotic carotid and vertebral artery disease. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2023;65(1):7–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Olie RH, Hensgens RRK, Wijnen P, et al. Differential impact of cytochrome 2C19 allelic variants on three different platelet function tests in clopidogrel-treated patients. J Clin Med. 2021;10(17):3992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hochholzer W, Trenk D, Fromm MF, et al. Impact of cytochrome P450 2C19 loss-of-function polymorphism and of major demographic characteristics on residual platelet function after loading and maintenance treatment with clopidogrel in patients undergoing elective coronary stent placement. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55(22):2427–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]