Abstract

Diabetic kidney disease (DKD) represents the most lethal complication in both type 1 and type 2 diabetes. The disease progresses without obvious symptoms and is often refractory when apparent symptoms have emerged. Although the molecular mechanisms underlying the onset/progression of DKD have been extensively studied, only a few effective therapies are currently available. Pathogenesis of DKD involves multifaced events caused by diabetes, which include alterations of metabolisms, signals, and hemodynamics. While the considerable efficacy of sodium/glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitors or angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs) for DKD has been recognized, the ever-increasing number of patients with diabetes and DKD warrants additional practical therapeutic approaches that prevent DKD from diabetes. One plausible but promising target is the mechanistic target of the rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1) signaling pathway, which senses cellular nutrients to control various anabolic and catabolic processes. This review introduces the current understanding of the mTOR signaling pathway and its roles in the development of DKD and other chronic kidney diseases (CKDs), and discusses potential therapeutic approaches targeting this pathway for the future treatment of DKD.

Keywords: mTORC1, Rapamycin, Diabetic nephropathy, Diabetic kidney disease (DKD), Nutrients, SGLT2 inhibitors

Introduction

Diabetic complications such as DKD do not occur if levels of blood glucose are well controlled. In one sense, this statement is correct. However, recent studies suggested that this statement may be optimistic, as obesity as well as hypertension, primarily associated with type 2 diabetes, have been recognized as independent risk factors for chronic kidney disease (CKD) [1, 2]. Even though healthcare providers and patients are well aware that calorie restriction for maintaining ideal body weight and glycemic control is the effective and fundamental treatment to halt the onset and progression of DKD, achieving the goal remains challenging. Inhibition of cellular mTORC1 activity results in similar cellular responses derived from calorie restriction. The mTORC1 senses cellular nutrients, such as amino acids, lipids, and glucose, to control essential cellular anabolic and catabolic processes [3]. mTORC1 phosphorylates dozens of substrates that stimulate anabolic reactions (e.g., protein synthesis and lipid biogenesis). In contrast, it inhibits catabolic reactions, such as autophagy and lysosome biogenesis [4]. Recent studies demonstrated that hyperactivation of the mTORC1 signaling occurs in various organs, including the kidney, in both animals and humans under obese and diabetic conditions [5–8]. Preclinical studies using animal models of diabetes, obese, and kidney-specific knockout mice indicated that aberrant activation of mTORC1 in the kidney cells contributes to the development of several CKDs, including DKD [7–9]. Although preclinical studies using rodent diabetic animals have shown significant efficacy of rapamycin in protecting kidney cells and renal functions from diabetes, mTORC1 inhibitors, such as rapalogs, which are currently available in clinical practice, are difficult to use in individuals, especially those with CKDs [10, 11]. Intriguingly, these drugs often worsen renal function in these patients through poorly defined molecular mechanisms. Therefore, while mTOR signaling is undoubtedly an attractive and potentially valuable target in the treatment of DKD, further basic research is needed to modulate this pathway more selectively and safely. In this review, we introduce the current understanding of mTOR signaling and its role in chronic kidney diseases and discuss the approaches to target this pathway for the future treatment of DKD.

mTOR signaling: general background

mTOR kinase is a fundamental regulator of cell growth, differentiation, proliferation, and metabolic processes. Dysregulation of mTOR signaling is associated with various human health problems, including metabolic disorders and cancer, making it a target of interest in biomedical research and clinics [12, 13]. mTOR, an evolutionarily conserved serine/threonine kinase, forms two distinct functional complexes, mTOR complex 1 (mTORC1) and mTORC2, which are also conserved from yeast to mammals. mTORC1 receives multiple signals from growth factors, amino acids, glucose, and lipids to promote essential cellular anabolic processes such as protein, lipid, and nucleotide synthesis [14]. Simultaneously, mTORC1 inhibits autophagy, a major cellular catabolic process. In contrast, growth factors are primary upstream stimulants for mTORC2 to promote glucose metabolism, cell proliferation, cytoskeletal reorganization, and survival.

mTORC1 balances anabolic and catabolic processes by phosphorylating a plethora of substrates. For instance, the phosphorylation of Thr389 of S6 Kinase 1 (S6K1) by mTORC1 stimulates S6K1 activity, leading to the enhancement of protein, lipid, and nucleotide biogenesis, and is often used for monitoring cellular mTORC1 activity. In contrast, the phosphorylation of Unc-51-like autophagy-activating kinase 1 (ULK1) by mTORC1 blocks autophagy induction, and the phosphorylation of transcription factor EB (TFEB) transcription factor blocks its nuclear translocation, restricting lysosomal and autophagy-related gene expression [4].

mTORC2 exerts its function by mainly phosphorylating the hydrophobic motifs of AGC (cAMP-dependent protein kinase A/cGMP-dependent protein kinase G/protein kinase C) kinase family such as Akt, protein kinase C (PKC), and serum/glucocorticoid-regulated kinase (SGK) and increasing their kinase activity or stability. For instance, mTORC2-dependent Ser473 phosphorylation of Akt boosts its kinase activity around fivefold in vitro [15].

mTORC1 is highly sensitive to rapamycin, which forms a complex with FK506-binding protein prolyl Isomerase 1A (FKBP12) and interacts with the FKBP12–Rapamyycin binding (FRB) domain adjacent to the mTOR kinase domain in the mTORC1 complex [16]. The binding of the rapamycin–FKBP12 complex to the FRB domain restricts the accessibility of mTORC1 substrates to the kinase domain, thereby acting as a specific allosteric inhibitor for mTORC1. In contrast, mTORC2 is largely insensitive to rapamycin because the FRB domain is hindered by a specific component of mTORC2 (i.e., Rictor) [17]. While the mature mTORC2 is rapamycin resistant, newly synthesized mTOR can be captured by rapamycin, which mitigates the assembly of mTORC2 [18]. Thus, long-term treatment of rapamycin also inhibits the functions of mTORC2 by suppressing the formation of mTORC2 in various cells and tissues, including the kidney [11].

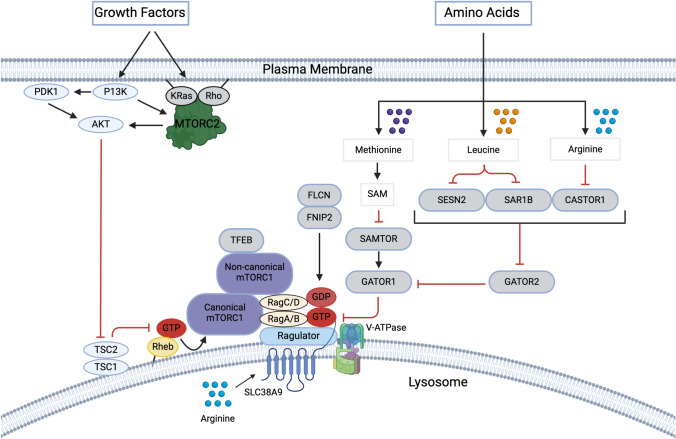

mTOR signaling: mechanisms of growth factor-induced mTORC1 activation

Growth factors such as insulin and insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) are common stimulants for both mTORC1 and mTORC2. Recent studies indicate that growth factors enhance the assembly of Ras-related small GTPases for mTORC2 activation (Fig. 1). Growth factors induce phosphorylation of KRas and RhoA, which promotes the formation of the KRas–RhoA heterodimer that recruits and activates mTORC2 on the membranes. Notably, in the active heterodimeric state, KRas displays a GTP-bound form, whereas RhoA forms a GDP-bound form [19]. The binding conformation of the super Kras–RhoA–mTORC2 complex (KARATE) remains elusive, and the detailed structure analyses warrant revealing the molecular mechanism underlying Kras–RhoA heterodimer-induced mTORC2 activation. Growth factors are also important inputs for mTORC1 activation. Interestingly, recent studies indicated that there are two structurally distinct mTORC1s, canonical and non-canonical mTORC1 [20]. The canonical mTORC1 activation that occurred on the lysosome requires growth factor-induced Akt activation. Active Akt phosphorylates and inactivates tuberous sclerosis 2 (TSC2, also known as tuberin) [21], the GTPase activating protein (GAP) for Rheb small GTPase [22], by inducing the dissociation of the TSC complex from the lysosome (Fig. 1) [23]. Upon inactivation of the GAP activity of the TSC complex on the lysosome, Rheb becomes active and directly interacts with canonical mTORC1, which induces a conformational change to the competent kinase complex [24, 25]. Hence, the active canonical mTORC1 phosphorylates the majority of mTORC1 substrates, such as S6K1 and eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E-binding protein 1 (4EBP1). In contrast to the canonical mTORC1, the non-canonical mTORC1, which phosphorylates and inactivates TFEB, does not require Rheb for the conformational change of mTORC1. This indicates that mTOR kinase in the non-canonical mTORC1 is already competent to phosphorylate TFEB without input from growth factors [20, 26]. In support of this idea, TFEB is structurally well integrated into the non-canonical mTORC1 with additional active Rag small GTPases as key compartments of non-canonical mTORC1 on the lysosome. Since the activity of Rag small GTPases is enhanced by amino acids such as leucine and arginine, the non-canonical mTORC1 is mainly stimulated by amino acids to phosphorylate TFEB.

Fig. 1.

Growth factor- and amino acid-sensing pathways for mTORC1 activation growth factors such as insulin activate PI3K, which triggers the recruitment of PDK1, Akt, and mTORC2 to the membrane through PI(3,4,5)P3 production. Growth factors also stimulate the KRas–RhoA heterodimer to scaffold mTORC2 on the membrane where mTORC2 and PDK1 phosphorylate and fully activate Akt. The active Akt phosphorylates TSC2 and repels the TSC complex, the GAP protein complex for Rheb, from the lysosome, providing a permissive condition where Rheb becomes an active form on the lysosome. While active Rheb interacts with mTOR kinase of the canonical mTORC1 and stimulates its activity, the non-canonical mTORC1 does not require Rheb to phosphorylate its substrate, TFEB. Cytosolic amino acids such as leucine or arginine interact with leucine (e.g., Sestrin2 and SAR1B) or arginine-sensing (e.g., CASTOR1) proteins, respectively. The binding of leucine or arginine to those amino acid-sensing proteins disrupts their interaction with GATOR2, leading to GATOR2 activation. Active GATOR2 inhibits GATOR1, the GAP protein complex toward Rag A/B, thereby activating Rag heterodimer and enhancing lysosomal canonical and non-canonical mTORC1 recruitment. The S-adenosylmethionine sensor upstream of mTORC1 (SAMTOR), an activator of GATOR1, senses methionine-derived metabolite SAM. SAM directly interacts with SAMTOR and inhibits its function, thereby inhibiting GATOR1. The FLCN–FNIP complex functions as a GAP for RagC/D and activates the Rag heterodimer. SLC38A9, a lysosomal membrane amino acid transporter, senses lysosomal luminal arginine and acts as a GEF for RagA/B. Together, these amino acid-sensing machinery play a major role in stimulating lysosomal canonical and non-canonical mTORC1 localization

mTOR signaling: amino acid-sensing mechanism for mTORC1 activation

Our bodies have a large variety of amino acids that can be utilized for critical cellular function. Interestingly, amino acids are essential for mTORC1 but not mTORC2 activation. Amino acids play a key role in recruiting both canonical and non-canonical mTORC1 to the lysosome membrane, where canonical mTORC1 interacts with Rheb for its activation [27]. It has been reported that thirteen amino acids, including Ala, Arg, Asn, Gln, His, Leu, Met, Phe, Ser, Thr, Trp, Tyr, and Val, are involved in the processes of mTORC1 activation [28]. All of these amino acids, except Asn and Gln, may contribute to the recruitment of mTORC1 to the lysosome through the activation of Rag small GTPases, another Ras-related small GTPases that capture the mTORC1 on the lysosome membrane. Mammalian Rag small GTPases are composed of four isoforms, Rag A, B, C, and D, forming a heterodimer between RagA or RagB and RagC or RagD [29]. In the active heterodimer that interacts with mTORC1, RagA/B is found in a GTP-bound, while RagC/D is in a GDP-bound form. Among those amino acids, Leu and Arg are the most potent stimulators for the Rag heterodimer, lysosomal mTORC1 recruitment, and subsequent mTORC1 activation (Fig. 1) [30]. Mechanistically, four Leu binding proteins, sestrin 1 (SESN1), SESN2, secretion-associated Ras-related GTPase 1A (SAR1A), and SAR1B [31, 32], and two Arg-binding proteins [33, 34], the cytosolic arginine sensor for mTORC1 subunit 1 (CASTOR1) and the solute carrier family 38 member 9 (SLC38A9) have been identified as upstream regulators of the Rag heterodimer. Other than SLC38A9, all other Leu- and Arg-binding proteins interact with and inhibit Gap Activity Toward Rags 2 (GATOR2), the protein complex that inhibits GATOR1, the GAP complex toward Rag A/B [35]. Leu or Arg binding to SESNs/SAR1s or CASTOR1, respectively, blocks their inhibitory effect on GATOR2; hence, GATOR2 suppresses GATOR1 function, resulting in the activation of Rag A/B. While these proteins respond to cytosolic Leu or Arg, SLC38A9 senses lysosomal luminal Arg. SLC38A9 is an amino acid transporter with low capacity and specificity, with a preference for polar amino acids. Recent studies demonstrated that Arg binding to SLC38A9 increases its flux for other luminal amino acids to the cytosol [36]. SLC38A9 has also been shown to interact with Ragulator, a pentametric lysosomal membrane binding protein responsible for anchoring the Rag heterodimer onto the lysosomal surface. Interestingly, Arg binding to SLC38A9 instigates a large conformational change of its N-terminal region, which functions as a key domain for guanine nucleotide exchange of Rag A/B [37]. Thus, cytosolic and lysosomal luminal Leu and Arg cooperatively regulate both the GAP and GEF proteins for Rag A/B, thereby enhancing lysosomal mTORC1 recruitment and its subsequent activation. In addition to Leu and Arg, Met sensing protein for mTORC1 activation has also been identified. The S-adenosylmethionine sensor upstream of mTORC1 (SAMTOR or C7ORF60) serves as an activator for the GATOR1 [38]. Once SAM binds to SAMTOR, its ability to support GATOR1 is mitigated, thereby enhancing the activity of Rag heterodimer.

Amino acids also stimulate GTP hydrolysis of Rag C/D to activate the Rag heterodimer. Folliculin (FLCN)–FLCN interacting protein (FNIP) 1/2 complex functions as the GAP for Rag C/D [39]. Interestingly, the FLCN–FNIP localizes on the lysosome with the Ragulator–SLC38A9 complex under amino acid-insufficient conditions [40, 41]. Upon amino acid stimulation, the N-terminal domain of SLC38A9 destabilizes this FLCN-containing super complex and triggers GAP activity of the FLCN–FNIP complex toward RagC/D, completing the processes for Rag heterodimer activation to recruit mTORC1 to the lysosomal surface. It is conceivable that other amino acids that possess a positive role in lysosomal mTOR1 recruitment may also exert similar actions impinging on the above major regulatory machinery to support the processes for Rag heterodimer activation.

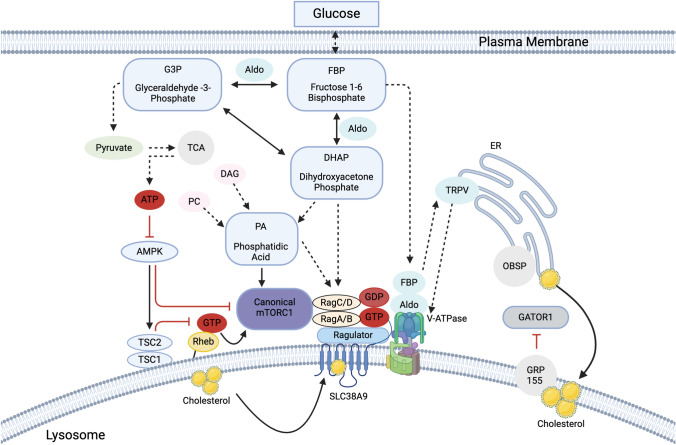

mTOR signaling: lipid and glucose-sensing mechanism for mTORC1 activation

In addition to growth factors and amino acids, several different types of lipids have significant roles in mTORC1 regulation. Phosphatidylinositol-3,4,5-triphosphate (PtdIns(3,4,5)P3) acts as a common and essential stimulator for both mTORC1 and mTORC2 [42]. It recruits mTORC2 and Akt to the membrane for their activation. In contrast to the general consensus of PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 as an essential activator for mTORC1, PtdIns(3,5)P2 may have bidirectional roles in regulating mTORC1 activity on the lysosome. On the lysosomal membrane, PtdIns(3,5)P2 can be generated by PIKfyve and support lysosomal mTORC1 localization [43, 44]. However, it also recruits the TSC complex to the lysosome, which inhibits mTORC1 activity [45]. It remains unclear if different levels of PtdIns(3,5)P2 on the lysosome determine its preference for binding either mTORC1 or the TSC complex. Lysosomal cholesterol also plays a key role in supporting mTORC1 activity. Oxysterol-binding protein (OSBP) is anchored to the ER by Vesicle-Associated Membrane Protein-Associated Protein (VAP) A and VAPB, and it delivers cholesterol from the ER to the lysosome [46]. The lysosomal membrane cholesterol enhances lysosomal recruitment of mTORC1 through SLC38A9 and G-protein-coupled receptor 155 (GPR155, also known as LYCHOS) by activating Rag heterodimer. When the cholesterol binds SLC38A9, it may support GTP-loading to RagA/B. When it binds GPR155, the cholesterol-bound GPR155 may sequester GATOR1 on the lysosome away from the Rag heterodimer, keeping RagA/B in the active state [47]. Consistently, Niemann–Pick disease type C1 (NPC1), an essential cholesterol exporter from the lysosome, reduces lysosomal mTORC1 localization [48]. When cells lack functional NPC1, mTORC1 reaches high levels of activation, resulting in loss of proteolysis and mitochondrial dysfunction [49]. These observations indicate that lysosomal cholesterol impinges on the amino acid-sensing mechanisms for supporting cellular mTORC1 activity (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Glucose- and lipid-sensing pathways for mTORC1 activation. Signals from fructose-1, 6-bisphosphate (FBP), and its metabolite, dihydroxyacetone phosphate (DHAP), activate mTORC1 through multiple pathways. DHAP derived from FBP by aldolase activates Rag heterodimer in a manner dependent on or independent of phosphatidic acid (PA). FBP-bound aldolase has also been reported to activate vATPase through their direct interaction that triggers TRPV activation and calcium release at the lysosome–endoplasmic reticulum (ER) contact site, thereby supporting Rag heterodimer activation. PA is also generated from diacylglycerol (DAG) or phosphatidylcholine (PC), and directly interacts with mTOR and supports mTORC1 activation. PA also enhances lysosomal mTORC1 localization through unknown mechanisms. Glyceraldehyde-3-Phosphate (G3P) derived from the aldolase-catalyzed FBP is converted to pyruvate and then ATP through the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle. Increased cellular ATP inhibits AMPK, which is a suppressor of the canonical mTORC1. AMPK is known to phosphorylate TSC2 and Raptor, which inhibits mTORC1 activity. Lysosomal cholesterol has been shown to interact with SLC38A9 and activate its function. In addition, lysosomal cholesterol also binds to G-protein-coupled receptor 155 (GRP155) and enhances its sequestration of GATOR1 away from the Rag heterodimer, thereby supporting the activation of the Rag heterodimer. It has also been indicated that cholesterol transferred from ER to the lysosomes via oxysterol binding protein (OSBP) supports lysosomal mTORC1 recruitment and its activation

Unlike phosphatidylinositol and lysosomal cholesterol, phosphatidic acid (PA) can activate mTORC1 directly [50]. There are three intracellular pathways to generate PA [51]. Phospholipase D (PLD) can convert phosphatidylcholine, and diacylglycerol kinase (DGK) or PRK-like ER kinase (PERK) can convert diacylglycerol to PA. If DGK or PLD are silenced, mTORC1 activity is reduced [52, 53]. The third pathway involves de novo synthesis from glucose. Glycolysis breaks glucose down into fructose-1,6-bisphosphate (FBP), which splits into dihydroxyacetone phosphate (DHAP) and glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate (G3P). GAPDH converts DHAP to glycerol 3-phosphate, which is further converted into PA by glycerol 3-phosphate acyltransferase (GPAT) and lysophosphatidic acid acyltransferase (LPAAT). Thus, glucose can support cellular mTORC1 activity in part via PA production. A recent study also demonstrated that PA may support mTORC1 activity by enhancing its lysosomal localization [54]. However, the molecular mechanism underlying PA-induced mTORC1 recruitment to the lysosome remains unclear.

In addition to its role in PA synthesis, DHAP synthesized from glucose or fructose can also enhance lysosomal mTORC1 localization and its activity independent of PA [55]. Although the exact molecular mechanisms underlying DHAP-induced mTORC1 activation remain unclear, DHAP can be an excellent marker for mTORC1 to monitor actual carbon uptake for controlling anabolic processes since fructose-derived DHAP synthesis is not subjected to the feedback inhibition from the downstream metabolites. It has also been postulated that the glucose level in a cell controls mTORC1 activity through several alternative mechanisms. Recent studies also proposed that glycolytic enzyme aldolase acts as a gatekeeper to monitor cellular glucose metabolites to regulate both 5' adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK) and mTORC1 independent of cellular ATP levels [56, 57]. Aldolase is an enzyme that converts FBP to DHAP and G3P (Fig. 2). When aldolase is occupied with FBP, it stimulates vacuolar-type ATPase (vATPase), which interacts with the Ragulator and enhances the activity of the Rag heterodimer and mTORC1 [58]. In contrast, FBP-free aldolase inhibits mTORC1 by suppressing vATPase, which stabilizes the Ragulator–Axin–LKB1 complex, triggering the activation of AMPK on the lysosome [57]. Interestingly, FBP-free aldolase-induced mTORC1 inhibition is independent of cellular DHAP and even occurs in cells lacking AMPK expression, suggesting that aldolase regulates mTORC1 in a manner independent of DHAP and AMPK activity. On the other hand, prolonged glucose starvation limits ATP generation in the cell. Considerable ATP reduction in the cells augments the activation of AMPK, which phosphorylates TSC2 and Raptor, a key component of mTORC1, and inhibits mTORC1 activity [59, 60]. Thus, signals from glucose metabolites act on multiple upstream molecules important for mTORC1 activation in a manner dependent on or independent of AMPK activity (Fig. 2).

mTORC1 signaling in diabetic kidney disease (roles of aberrant activation of mTORC1 in the development of DN)

Relevance of mTORC1 in the diabetic kidney

One of the most prominent histological alterations in the early diabetic kidney is aberrant cell growth in multiple kidney cells, including podocytes and tubular cells, which are associated with glomerular and renal hypertrophy. Under diabetic conditions, kidney cells are exposed to an enormous amount of nutrients (e.g., glucose and amino acids) and growth factors (e.g., insulin) due to increased filtration, excess calorie intake, hyperglycemia, hyperinsulinemia, and insulin supplementation. These factors are all essential for the activation of mTORC1. In fact, mTORC1 activity monitored by the phosphorylated form of S6 protein (pS240/244 S6) is largely elevated in the podocytes and tubular cells in both type 1 and type 2 diabetic animals and individuals with type 2 diabetes [7, 8]. Although these hypertrophic changes associated with hyper mTORC1 activity are considered adaptive cellular responses to maintain the glomerular filtration barrier and nephron function, the continuous aberrant mTORC1 activation in these cells causes vulnerability and injury in podocytes and proximal tubular cells [61, 62].

Hyperactivity of mTORC1 in the onset/development of diabetic kidney disease

The first evidence that supports the idea that aberrant mTORC1 activation in renal cells leads to their dysfunction in DKD is the findings that rapamycin, an mTORC1 inhibitor, significantly protects renal pathological alterations in diabetic mice without affecting their blood glucose levels [63–65]. These observations suggested that mTORC1 contributes to the pathogenesis of DKD downstream of hyperglycemia [63–65]. The varying roles of mTORC1 activation in the podocytes or proximal tubular cells in the development of DKD were further elucidated by a series of genetic studies using podocyte (Podo)- or proximal tubular cell (PRT)-specific knockout mouse models under normal or diabetic conditions. In non-diabetic mice, ablation of the functional TSC complex in either podocytes or proximal tubular cells displaying cell-specific aberrant mTORC1 activation recapitulated many pathological and functional alterations seen in the diabetic kidney [8, 9]. Conversely, in diabetic mice, a heterozygous knockout of Raptor (mTORC1) resulted in fewer DKD-associated glomerular and tubular injuries. However, complete ablation of Raptor in these cells led to dysfunction of the cells and organs in non-diabetic mice; Podo-specific Raptor KO mice displayed severe podocyte growth defect and proteinuria [7], and PRT-specific Raptor KO mice showed glucosuria, phosphaturia, amino-aciduria, and albuminuria [66]. While these studies highlighted the significant role of aberrant mTORC1 activation in the development of DKD phenotypes, they also indicated that physiological levels of mTORC1 activity in these cells are vital to the normal function of podocytes and proximal tubular cells. Since the detailed molecular mechanisms underlying mTORC1 activation-induced renal cell injury under diabetic conditions remain unclear, and further studies elucidating the event downstream of mTORC1 in these kidney cells warrant future investigations.

Chronic kidney diseases associated with hyper mTORC1 signaling

Preclinical studies indicate that aberrant activation of mTORC1 signaling may contribute to several distinct chronic kidney diseases in addition to DKD. These include obesity-related kidney disease (ORKD), polycystic kidney disease (PKD), and focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS). It has been seen in the kidney tissues of patients as well as model animals with ORKD, FSGS, and PKD that hyperactivation of mTORC1 is present. The aberrant activation of mTORC1 in renal cells can be attributed to a variety of mechanisms based on the different CKD. These mechanisms that lead to mTORC1 activation in specific kidney cells are caused by aforementioned nutrients (e.g., glucose, amino acids, and lipids), alteration of hemodynamics (e.g., glomerular hypertension), and genetic mutations (e.g., polycystin-1 (PKD1), TSCs) to the upstream mTOR suppressors.

Polycystic kidney disease

The primary causes of autosomal-dominant PKD (ADPKD) or autosomal-recessive PKD (ARPKD) are mutations in PKD1, PKD2 or fibrocystin (PKHD1 or polyductin) [67]. Cyst development in these diseases is advanced by the hyperactivation of the mTORC1 in renal tubular cells [68]. PKD1 and PKD2 form a heteromeric transmembrane complex that functions as an ion channel for calcium. PKD1 acts as a receptor for Wingless and integrated (WNT) ligands and controls WNT-induced calcium flux and tubular morphogenesis [69]. Another protein found at the cilia is PKHD1, which is a receptor protein associated with the membrane that may regulate WNT signaling alongside PKD2 [70]. The specific mechanisms that promote mTORC1 activation due to the loss of PKD2 or PKHD1 are still not clear; however, this loss may alter the cellular functions of PKD1. Both TSC2 and PKD1 are found on the same chromosome, and they are often deleted together, which is known as TSC2/PKD1 contiguous deletion syndrome, resulting in severe early-onset ADPKD [71]. Given this result, it is suggested that the seriousness of the disease increases after the hyperactivation of mTORC1 due to TSC2 deletion. Under physiological conditions, PKD1 is a suppressor of mTORC1, but the functional role of PKD1 on the lysosome where the inhibitory effects should be displayed has not been conclusive. While the inhibitors of mTORC1, such as rapamycin, can decrease cystogenesis in animal models of PKD [72, 73], clinical trials of rapamycin analogs (rapalogs) in ADPKD patients have proven to be non-beneficial [74, 75]. However, these trials were limited due to a variety of factors (study duration, dosage of rapalogs, etc.); hence, further trials with an improved study design and a larger sampling size are needed.

Obesity-related and diabetic kidney disease

The excessive intake of nutrients can lead to the activation of mTORC1 via lysosomal recruitment. While there is minimal evidence suggesting enhanced lysosomal localization of mTORC1 in the kidney cells with obesity or diabetes due to a lack of reliable assays in the renal tissues, there is increased mTORC1 activity in the tubular cells and podocytes of individuals who have obesity and diabetes. The key triggers for aberrant mTORC1 activation in both patients and animal models, determined under obese or diet-induced diabetic conditions, are high-calorie diets consisting of amino acids (e.g., leucine), carbohydrates (e.g., sucrose), and lipids (e.g., cholesterol) paired with elevated plasma insulin levels. Although insulin insufficiency, as seen in uncontrolled type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) or severe insulin resistance, is likely to lessen the activation of mTORC1 on the lysosomes of kidney cells [6], increased glucose intake may contribute to abnormal mTORC1 activity in the kidney in both type 2 and type 1 diabetes. Hyperactivation of mTORC1 in the podocytes of kidney cells may be caused by increased cellular levels of FBP or DHAP because of high blood glucose or fructose consumption due to the dependence on glycolytic pathways for their energy needs [55, 57]. Under diabetic conditions, energy production in proximal tubular cells is converted from fatty acid oxidation (FAO) to glycolysis due to mitochondrial dysfunction-related metabolic reprogramming [76]. This may also lead to increased cellular FBP and DHAP, which enhance mTOCR1 activation in podocytes and renal proximal tubular cells.

Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis

FSGS is a lesion within the glomerulus resulting from either glomerular hypertrophy, hyperfiltration, or direct podocyte injury/death/detachment. The potent inhibition of mTORC1 activity by the ablation of Raptor or the ectopic expression of active 4EBP1 in podocytes exacerbates their loss, albuminuria, and the development of FSGS in animal models, indicating that impairment of podocyte growth underlies the etiology of FSGS [61, 62, 77]. Interestingly, increased mTORC1 activity in podocytes has been observed in glomerular lesions of several mouse models of FSGS and individuals with primary FSGS [62, 77, 78]. mTORC1 activation increases podocyte volume, allowing the remnant podocytes to cover/maintain an intact filtration surface. However, continuous mTORC1 activation in the remnant podocytes may reduce their integrity and viability, further reducing glomerular podocyte number and density. This suggests that mTORC1 activation in podocytes is critical in adaptative growth when podocyte density is reduced. Importantly, a moderate reduction of mTORC1 activity by calorie restriction or low-dose rapamycin treatment attenuates the progression of glomerular dysfunction in FSGS animal models [61, 77]. These studies indicate that it is critical for mTORC1 activity to be lower but not potently inhibited to maintain the integrity of remnant podocytes in the glomeruli with FSGS. Thus, a better way to maintain podocyte function in FSGS is to combine approaches that reduce the glomerular volume/capillary surface area and aberrant mTORC1 activity in podocytes.

While there has been advancement in understanding the mTORC1 signaling pathway, the key upstream or downstream that cause damage to the kidney cells in CKDs have not been clearly understood. The mechanisms that cause continuous aberrant mTORC1 activation remain mostly unknown. A proposed cause of the dysfunction of podocytes is the impairment of autophagy due to mTORC1 hyperactivity; however, it has been demonstrated that autophagic activity in podocytes remains high even when a functional TSC complex is not present [79]. These observations suggest that loss of autophagy may not be a key event in compromising the podocyte because of increased mTORC1 activity. It has been seen in renal tubular cells, hypertrophic phenotypes seen in DKD and PKD are induced by S6K1, which acts downstream of mTOCR1 [80]. Mice with S6K1 knocked out were resistant to diabetes-induced renal hypertrophy. S6K1 plays a critical role in cyst formation in tubular cells specific TSC1 (hamartin) knockout mice by interrupting cell division but not cell proliferation, suggesting that mTORC1 hyperactivity compromises normal development through aberrant S6K1 activation [81]. However, the downstream effectors of S6K1 and other substrates of mTORC1 that cause podocyte deterioration due to aberrant mTORC1 activation remain elusive. Revealing the effects of downstream mTORC1 effectors in podocytes and other kidney cells is critical in understanding the mechanisms that cause mTORC1-related CKDs.

Current and future therapeutic approaches for ORKD and DKD treatment by targeting mTORC1 signaling

mTOR inhibitors

Consistent with the observations revealed by various genetic approaches using rodent models, mTORC1 inhibitors, such as rapamycin or rapalogs, effectively protect renal cell injury and dysfunction from diabetes. However, despite these positive findings in animal models, some studies reported harmful outcomes of rapalogs in treating CKD patients with glomerular and tubular dysfunction, which makes it challenging to use rapamycin as a safe agent to treat patients potentially bearing renal cell injury or dysfunction [11, 82]. Two potential mechanisms that may underlie the nephrotoxicity caused by rapamycin can be considered. First, prolonged rapamycin treatment may eliminate essential mTORC1 functions that support the physiological roles of kidney cells or adaptive responses under disease conditions with renal cell stresses. Second, the prolonged rapamycin treatment also inhibits the mTORC2–Akt pathway, which plays a pivotal role in renal cell survival [11, 18]. Thus, moderate but specific inhibition of mTORC1 is critical and would be a promising strategy for long-term treatment for mTORC1-associated ORKD and DKD. A potential approach to fulfilling these conditions is to target the amino acid-sensing machinery for mTORC1 activation. At least in podocytes, the ablation of this machinery by knocking out Ragulator, an essential scaffold and activator for the Rag heterodimer, does not eliminate mTORC1 activity in podocytes, although the podocytes lose largely their sensitivity to amino acids for inducing acute mTORC1 activation [83]. Targeting more upstream branches that impinge on the Ragulator-Rag system would be a more attractive and feasible strategy for reducing but not eliminating mTORC1 activity without affecting mTORC2 (Fig. 1).

SGLT2 inhibitors and metformin: the ideal suppressor of mTORC1?

Sodium–glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors (SGLT2i) and metformin are two frontline anti-diabetic agents that not only ameliorate hyperglycemia but also protect kidney and other organ functions from metabolic disorders. Importantly, both SGLT2i and metformin also exert moderate inhibitory effects on mTORC1 activity. In addition to lowering the concentrations of glucose metabolites (e.g., FBP and DHAP) in the cell, the reduction of blood glucose levels by SGLT2i is known to increase in ketone bodies such as β-hydroxybutyrate, which have inhibitory effects on mTORC1 activity in kidney cells [84]. However, the molecular mechanisms by which the ketone body suppresses mTORC1 activity remain elusive. SGLT2i may also have a role in stimulating the TSC complex, the GAP for Rheb, as reno-protective effects of SGLT2i are diminished when the TSC1 is ablated in the proximal tubules of Akita diabetic mice [9]. A recent study also demonstrated that the treatment of SGLT2i reduced gene expression of enzymes related to glycolysis and gluconeogenesis in proximal tubular cells in individuals with type 2 diabetes [85]. SGLT2i also decreased the gene expression of the proteins involving mTORC1 activation. Thus, the SGLT2i exerts its inhibitory effects on the mTORC1 through multiple mechanisms.

Metformin, a major anti-diabetic agent, exerts pleiotropic effects on cellular metabolism. A recent study demonstrated that clinically relevant concentrations of metformin interact with presenilin enhancer protein 2 (PEN-2), a gamma-secretase subunit, and suppress vATPase activity on the lysosome, thereby enhancing AMPK and suppressing mTORC1 activity [86]. Given the observations that vATPase activity is required for activating Rag heterodimer through the Ragulator–SLC38A9–FLCN–FNIP complex [87], low-dose metformin may inhibit mTORC1 activity independent of AMPK activation. Although the inhibitory effects of these drugs with clinically relevant concentrations on the mTORC1 activity are moderate; they did not inhibit mTORC2 activity, rather they may enhance mTORC2-dependent Akt phosphorylation by mitigating the negative feedback inhibition toward PI3K activity from mTORC1 [88, 89].

While the exact contribution of the lowering mTORC1 activity to the reno-protective outcome of these drugs needs to be further studied, the moderate and specific mTORC1 inhibitory properties are ideal for the long-term treatment for maintaining physiologic function of the kidney and other organs. Recent studies demonstrated that not only amino acids but also other nutrients, such as glucose and lipids, impinge on the amino acid-sensing machinery to facilitate lysosomal mTORC1 localization (Fig. 2) [47, 55, 57]. Thus, any branch of those nutrient-sensing mechanisms is an attractive target to reduce the activity of the Rag heterodimer and lysosomal mTORC1 localization specifically without inhibiting the mTORC2–Akt pathway.

Conclusion remarks

Recent basic and preclinical studies have made significant progress in understanding the etiology of DKD. Kidney cells respond and adapt to unexpected supplies of nutrients, altered growth factors, and hemodynamics, and ultimately display their dysfunction. As introduced in this review, among multiple pathogenic events, the aberrant mTORC1 activation in the kidney cells is also a potential target for halting the onset/progression of DKD. The FDA-approved rapalogs are relatively safe agents that are well tolerated by patients as immunosuppressants. However, the non-specific inhibitory effect of rapalogs, especially with long-term treatment, on the mTORC2–Akt pathway causes unwanted cell vulnerability and metabolic derangements in kidney cells. Thus,

exploring new strategies by targeting nutrient-sensing machinery for mTORC1 activation, which enables specific and moderate suppression of cellular mTORC1 activity, would warrant the development of new mTORC1 inhibitors for mTORC1-related metabolic disorders with improved tolerance and precision.

Acknowledgements

This review is a summary of my presentation in a Special Lecture at the 66th annual meeting of the Japan Diabetes Society, Kagoshima, Japan. This work is supported by the National Institute of Health (NIH) RO1 grants (DK124709 and GM145631) to K. I.

Author contributions

L.H., S.V., E.O., A.T., O.K-G., and K.I. wrote the manuscript, and A.K. generated figures.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Vinamra Swaroop, Eden Ozkan, Lydia Herrmann, Aaron Thurman, Oliviamae Kopasz-Gemmen, and Abhiram Kunamneni have contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Jha V, Garcia-Garcia G, Iseki K, Li Z, Naicker S, Plattner B, Saran R, Wang AY, Yang CW. Chronic kidney disease: global dimension and perspectives. Lancet. 2013;382:260–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nawaz S, Chinnadurai R, Al-Chalabi S, Evans P, Kalra PA, Syed AA, Sinha S. Obesity and chronic kidney disease: a current review. Obes Sci Pract. 2023;9:61–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huynh C, Ryu J, Lee J, Inoki A, Inoki K. Nutrient-sensing mTORC1 and AMPK pathways in chronic kidney diseases. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2023;19:102–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Battaglioni S, Benjamin D, Walchli M, Maier T, Hall MN. mTOR substrate phosphorylation in growth control. Cell. 2022;185:1814–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yamahara K, Kume S, Koya D, Tanaka Y, Morita Y, Chin-Kanasaki M, Araki H, Isshiki K, Araki S, Haneda M, Matsusaka T, Kashiwagi A, Maegawa H, Uzu T. Obesity-mediated autophagy insufficiency exacerbates proteinuria-induced tubulointerstitial lesions. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;24:1769–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sakai S, Yamamoto T, Takabatake Y, Takahashi A, Namba-Hamano T, Minami S, Fujimura R, Yonishi H, Matsuda J, Hesaka A, Matsui I, Matsusaka T, Niimura F, Yanagita M, Isaka Y. Proximal tubule autophagy differs in type 1 and 2 diabetes. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2019;30:929–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Godel M, Hartleben B, Herbach N, Liu S, Zschiedrich S, Lu S, Debreczeni-Mor A, Lindenmeyer MT, Rastaldi MP, Hartleben G, Wiech T, Fornoni A, Nelson RG, Kretzler M, Wanke R, Pavenstadt H, Kerjaschki D, Cohen CD, Hall MN, Ruegg MA, Inoki K, Walz G, Huber TB. Role of mTOR in podocyte function and diabetic nephropathy in humans and mice. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:2197–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Inoki K, Mori H, Wang J, Suzuki T, Hong S, Yoshida S, Blattner SM, Ikenoue T, Ruegg MA, Hall MN, Kwiatkowski DJ, Rastaldi MP, Huber TB, Kretzler M, Holzman LB, Wiggins RC, Guan KL. mTORC1 activation in podocytes is a critical step in the development of diabetic nephropathy in mice. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:2181–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kogot-Levin A, Hinden L, Riahi Y, Israeli T, Tirosh B, Cerasi E, Mizrachi EB, Tam J, Mosenzon O, Leibowitz G. Proximal tubule mtorc1 is a central player in the pathophysiology of diabetic nephropathy and its correction by sglt2 inhibitors. Cell Rep. 2020;32:107954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fantus D, Rogers NM, Grahammer F, Huber TB, Thomson AW. Roles of mTOR complexes in the kidney: implications for renal disease and transplantation. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2016;12:587–609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Canaud G, Bienaime F, Viau A, Treins C, Baron W, Nguyen C, Burtin M, Berissi S, Giannakakis K, Muda AO, Zschiedrich S, Huber TB, Friedlander G, Legendre C, Pontoglio M, Pende M, Terzi F. AKT2 is essential to maintain podocyte viability and function during chronic kidney disease. Nat Med. 2013;19:1288–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cornu M, Albert V, Hall MN. mTOR in aging, metabolism, and cancer. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2013;23:53–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saxton RA, Sabatini DM. mTOR signaling in growth, metabolism, and disease. Cell. 2017;168:960–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ben-Sahra I, Manning BD. mTORC1 signaling and the metabolic control of cell growth. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2017;45:72–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sarbassov DD, Guertin DA, Ali SM, Sabatini DM. Phosphorylation and regulation of Akt/PKB by the rictor-mTOR complex. Science. 2005;307:1098–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Loewith R, Jacinto E, Wullschleger S, Lorberg A, Crespo JL, Bonenfant D, Oppliger W, Jenoe P, Hall MN. Two TOR complexes, only one of which is rapamycin sensitive, have distinct roles in cell growth control. Mol Cell. 2002;10:457–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yip CK, Murata K, Walz T, Sabatini DM, Kang SA. Structure of the human mTOR complex I and its implications for rapamycin inhibition. Mol Cell. 2010;38:768–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sarbassov DD, Ali SM, Sengupta S, Sheen JH, Hsu PP, Bagley AF, Markhard AL, Sabatini DM. Prolonged rapamycin treatment inhibits mTORC2 assembly and Akt/PKB. Mol Cell. 2006;22:159–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Senoo H, Murata D, Wai M, Arai K, Iwata W, Sesaki H, Iijima M. KARATE: PKA-induced KRAS4B-RHOA-mTORC2 supercomplex phosphorylates AKT in insulin signaling and glucose homeostasis. Mol Cell. 2021;81(4622–34):e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cui Z, Napolitano G, de Araujo MEG, Esposito A, Monfregola J, Huber LA, Ballabio A, Hurley JH. Structure of the lysosomal mTORC1-TFEB-rag-ragulator megacomplex. Nature. 2023;614:572–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Inoki K, Li Y, Zhu T, Wu J, Guan KL. TSC2 is phosphorylated and inhibited by Akt and suppresses mTOR signalling. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4:648–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Inoki K, Li Y, Xu T, Guan KL. Rheb GTPase is a direct target of TSC2 GAP activity and regulates mTOR signaling. Genes Dev. 2003;17:1829–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Menon S, Dibble CC, Talbott G, Hoxhaj G, Valvezan AJ, Takahashi H, Cantley LC, Manning BD. Spatial control of the TSC complex integrates insulin and nutrient regulation of mTORC1 at the lysosome. Cell. 2014;156:771–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Long X, Lin Y, Ortiz-Vega S, Yonezawa K, Avruch J. Rheb binds and regulates the mTOR kinase. Curr Biol. 2005;15:702–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yang H, Jiang X, Li B, Yang HJ, Miller M, Yang A, Dhar A, Pavletich NP. Mechanisms of mTORC1 activation by RHEB and inhibition by PRAS40. Nature. 2017;552:368–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Napolitano G, Di Malta C, Esposito A, de Araujo MEG, Pece S, Bertalot G, Matarese M, Benedetti V, Zampelli A, Stasyk T, Siciliano D, Venuta A, Cesana M, Vilardo C, Nusco E, Monfregola J, Calcagni A, Di Fiore PP, Huber LA, Ballabio A. A substrate-specific mTORC1 pathway underlies birt-hogg-dube syndrome. Nature. 2020;585:597–602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sancak Y, Peterson TR, Shaul YD, Lindquist RA, Thoreen CC, Bar-Peled L, Sabatini DM. The Rag GTPases bind raptor and mediate amino acid signaling to mTORC1. Science. 2008;320:1496–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Meng D, Yang Q, Wang H, Melick CH, Navlani R, Frank AR, Jewell JL. Glutamine and asparagine activate mTORC1 independently of rag GTPases. J Biol Chem. 2020;295:2890–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sekiguchi T, Hirose E, Nakashima N, Ii M, Nishimoto T. Novel G proteins, rag C and rag D, interact with GTP-binding proteins, rag A and rag B. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:7246–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hara K, Yonezawa K, Weng QP, Kozlowski MT, Belham C, Avruch J. Amino acid sufficiency and mTOR regulate p70 S6 kinase and eIF-4E BP1 through a common effector mechanism. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:14484–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wolfson RL, Chantranupong L, Saxton RA, Shen K, Scaria SM, Cantor JR, Sabatini DM. Sestrin2 is a leucine sensor for the mTORC1 pathway. Science. 2016;351:43–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen J, Ou Y, Luo R, Wang J, Wang D, Guan J, Li Y, Xia P, Chen PR, Liu Y. SAR1B senses leucine levels to regulate mTORC1 signalling. Nature. 2021;596:281–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chantranupong L, Scaria SM, Saxton RA, Gygi MP, Shen K, Wyant GA, Wang T, Harper JW, Gygi SP, Sabatini DM. The CASTOR proteins are arginine sensors for the mTORC1 pathway. Cell. 2016;165:153–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang S, Tsun ZY, Wolfson RL, Shen K, Wyant GA, Plovanich ME, Yuan ED, Jones TD, Chantranupong L, Comb W, Wang T, Bar-Peled L, Zoncu R, Straub C, Kim C, Park J, Sabatini BL, Sabatini DM. Lysosomal amino acid transporter SLC38A9 signals arginine sufficiency to mTORC1. Science. 2015;347:188–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bar-Peled L, Chantranupong L, Cherniack AD, Chen WW, Ottina KA, Grabiner BC, Spear ED, Carter SL, Meyerson M, Sabatini DM. A Tumor suppressor complex with GAP activity for the rag GTPases that signal amino acid sufficiency to mTORC1. Science. 2013;340:1100–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wyant GA, Abu-Remaileh M, Wolfson RL, Chen WW, Freinkman E, Danai LV, Vander Heiden MG, Sabatini DM. mTORC1 activator SLC38A9 is required to efflux essential amino acids from lysosomes and use protein as a nutrient. Cell. 2017;171(642–54):e12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shen K, Sabatini DM. Ragulator and SLC38A9 activate the rag GTPases through noncanonical GEF mechanisms. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018;115:9545–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gu X, Orozco JM, Saxton RA, Condon KJ, Liu GY, Krawczyk PA, Scaria SM, Harper JW, Gygi SP, Sabatini DM. SAMTOR is an S-adenosylmethionine sensor for the mTORC1 pathway. Science. 2017;358:813–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tsun ZY, Bar-Peled L, Chantranupong L, Zoncu R, Wang T, Kim C, Spooner E, Sabatini DM. The folliculin tumor suppressor is a GAP for the RagC/D GTPases that signal amino acid levels to mTORC1. Mol Cell. 2013;52:495–505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Petit CS, Roczniak-Ferguson A, Ferguson SM. Recruitment of folliculin to lysosomes supports the amino acid-dependent activation of rag GTPases. J Cell Biol. 2013;202:1107–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lawrence RE, Fromm SA, Fu Y, Yokom AL, Kim DJ, Thelen AM, Young LN, Lim CY, Samelson AJ, Hurley JH, Zoncu R. Structural mechanism of a rag GTPase activation checkpoint by the lysosomal folliculin complex. Science. 2019;366:971–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Manning BD, Toker A. AKT/PKB signaling: navigating the network. Cell. 2017;169:381–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bridges D, Ma JT, Park S, Inoki K, Weisman LS, Saltiel AR. Phosphatidylinositol 3,5-bisphosphate plays a role in the activation and subcellular localization of mechanistic target of rapamycin 1. Mol Biol Cell. 2012;23:2955–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hasegawa J, Tokuda E, Yao Y, Sasaki T, Inoki K, Weisman LS. PP2A-dependent TFEB activation is blocked by PIKfyve-induced mTORC1 activity. Mol Biol Cell. 2022;33:ar26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fitzian K, Bruckner A, Brohee L, Zech R, Antoni C, Kiontke S, Gasper R, Linard Matos AL, Beel S, Wilhelm S, Gerke V, Ungermann C, Nellist M, Raunser S, Demetriades C, Oeckinghaus A, Kummel D. TSC1 binding to lysosomal PIPs is required for TSC complex translocation and mTORC1 regulation. Mol Cell. 2021;81(2705–21):e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lim CY, Davis OB, Shin HR, Zhang J, Berdan CA, Jiang X, Counihan JL, Ory DS, Nomura DK, Zoncu R. ER-lysosome contacts enable cholesterol sensing by mTORC1 and drive aberrant growth signalling in niemann-pick type c. Nat Cell Biol. 2019;21:1206–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shin HR, Citron YR, Wang L, Tribouillard L, Goul CS, Stipp R, Sugasawa Y, Jain A, Samson N, Lim CY, Davis OB, Castaneda-Carpio D, Qian M, Nomura DK, Perera RM, Park E, Covey DF, Laplante M, Evers AS, Zoncu R. Lysosomal GPCR-like protein LYCHOS signals cholesterol sufficiency to mTORC1. Science. 2022;377:1290–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Castellano BM, Thelen AM, Moldavski O, Feltes M, van der Welle RE, Mydock-McGrane L, Jiang X, van Eijkeren RJ, Davis OB, Louie SM, Perera RM, Covey DF, Nomura DK, Ory DS, Zoncu R. Lysosomal cholesterol activates mTORC1 via an SLC38A9-niemann-pick c1 signaling complex. Science. 2017;355:1306–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Davis OB, Shin HR, Lim CY, Wu EY, Kukurugya M, Maher CF, Perera RM, Ordonez MP, Zoncu R. NPC1-mTORC1 signaling couples cholesterol sensing to organelle homeostasis and is a targetable pathway in niemann-pick type c. Dev Cell. 2021;56(260–76):e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fang Y, Vilella-Bach M, Bachmann R, Flanigan A, Chen J. Phosphatidic acid-mediated mitogenic activation of mTOR signaling. Science. 2001;294:1942–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kooijman EE, Burger KN. Biophysics and function of phosphatidic acid: a molecular perspective. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1791:881–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Foster DA. Phosphatidic acid signaling to mTOR: signals for the survival of human cancer cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1791:949–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Huang C, Bruggeman LA, Hydo LM, Miller RT. Shear stress induces cell apoptosis via a c-Src-phospholipase D-mTOR signaling pathway in cultured podocytes. Exp Cell Res. 2012;318:1075–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Frias MA, Mukhopadhyay S, Lehman E, Walasek A, Utter M, Menon D, Foster DA. Phosphatidic acid drives mTORC1 lysosomal translocation in the absence of amino acids. J Biol Chem. 2020;295:263–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Orozco JM, Krawczyk PA, Scaria SM, Cangelosi AL, Chan SH, Kunchok T, Lewis CA, Sabatini DM. Dihydroxyacetone phosphate signals glucose availability to mTORC1. Nat Metab. 2020;2:893–901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhang CS, Hawley SA, Zong Y, Li M, Wang Z, Gray A, Ma T, Cui J, Feng JW, Zhu M, Wu YQ, Li TY, Ye Z, Lin SY, Yin H, Piao HL, Hardie DG, Lin SC. Fructose-1,6-bisphosphate and aldolase mediate glucose sensing by AMPK. Nature. 2017;548:112–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Li M, Zhang CS, Feng JW, Wei X, Zhang C, Xie C, Wu Y, Hawley SA, Atrih A, Lamont DJ, Wang Z, Piao HL, Hardie DG, Lin SC. Aldolase is a sensor for both low and high glucose, linking to AMPK and mTORC1. Cell Res. 2021;31:478–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lin SC, Hardie DG. AMPK: sensing glucose as well as cellular energy status. Cell Metab. 2018;27:299–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gwinn DM, Shackelford DB, Egan DF, Mihaylova MM, Mery A, Vasquez DS, Turk BE, Shaw RJ. AMPK phosphorylation of raptor mediates a metabolic checkpoint. Mol Cell. 2008;30:214–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Inoki K, Zhu T, Guan K-L. TSC2 mediates cellular energy response to control cell growth and survival. Cell. 2003;115:577–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fukuda A, Chowdhury MA, Venkatareddy MP, Wang SQ, Nishizono R, Suzuki T, Wickman LT, Wiggins JE, Muchayi T, Fingar D, Shedden KA, Inoki K, Wiggins RC. Growth-dependent podocyte failure causes glomerulosclerosis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;23:1351–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Puelles VG, van der Wolde JW, Wanner N, Scheppach MW, Cullen-McEwen LA, Bork T, Lindenmeyer MT, Gernhold L, Wong MN, Braun F, Cohen CD, Kett MM, Kuppe C, Kramann R, Saritas T, van Roeyen CR, Moeller MJ, Tribolet L, Rebello R, Sun YB, Li J, Muller-Newen G, Hughson MD, Hoy WE, Person F, Wiech T, Ricardo SD, Kerr PG, Denton KM, Furic L, Huber TB, Nikolic-Paterson DJ, Bertram JF. mTOR-mediated podocyte hypertrophy regulates glomerular integrity in mice and humans. JCI Insight. 2019. 10.1172/jci.insight.99271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nagai K, Matsubara T, Mima A, Sumi E, Kanamori H, Iehara N, Fukatsu A, Yanagita M, Nakano T, Ishimoto Y, Kita T, Doi T, Arai H. Gas6 induces Akt/mTOR-mediated mesangial hypertrophy in diabetic nephropathy. Kidney Int. 2005;68:552–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lloberas N, Cruzado JM, Franquesa M, Herrero-Fresneda I, Torras J, Alperovich G, Rama I, Vidal A, Grinyo JM. Mammalian target of rapamycin pathway blockade slows progression of diabetic kidney disease in rats. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17:1395–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sakaguchi M, Isono M, Isshiki K, Sugimoto T, Koya D, Kashiwagi A. Inhibition of mTOR signaling with rapamycin attenuates renal hypertrophy in the early diabetic mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;340:296–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Grahammer F, Haenisch N, Steinhardt F, Sandner L, Roerden M, Arnold F, Cordts T, Wanner N, Reichardt W, Kerjaschki D, Ruegg MA, Hall MN, Moulin P, Busch H, Boerries M, Walz G, Artunc F, Huber TB. mTORC1 maintains renal tubular homeostasis and is essential in response to ischemic stress. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:E2817–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bergmann C, Guay-Woodford LM, Harris PC, Horie S, Peters DJM, Torres VE. Polycystic kidney disease. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2018;4:50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Fischer DC, Jacoby U, Pape L, Ward CJ, Kuwertz-Broeking E, Renken C, Nizze H, Querfeld U, Rudolph B, Mueller-Wiefel DE, Bergmann C, Haffner D. Activation of the AKT/mTOR pathway in autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease (ARPKD). Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2009;24:1819–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kim S, Nie H, Nesin V, Tran U, Outeda P, Bai CX, Keeling J, Maskey D, Watnick T, Wessely O, Tsiokas L. The polycystin complex mediates Wnt/Ca(2+) signalling. Nat Cell Biol. 2016;18:752–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kim I, Fu Y, Hui K, Moeckel G, Mai W, Li C, Liang D, Zhao P, Ma J, Chen XZ, George AL Jr, Coffey RJ, Feng ZP, Wu G. Fibrocystin/polyductin modulates renal tubular formation by regulating polycystin-2 expression and function. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19:455–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Brook-Carter PT, Peral B, Ward CJ, Thompson P, Hughes J, Maheshwar MM, Nellist M, Gamble V, Harris PC, Sampson JR. Deletion of the TSC2 and PKD1 genes associated with severe infantile polycystic kidney disease–a contiguous gene syndrome. Nat Genet. 1994;8:328–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Tao Y, Kim J, Schrier RW, Edelstein CL. Rapamycin markedly slows disease progression in a rat model of polycystic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:46–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zafar I, Ravichandran K, Belibi FA, Doctor RB, Edelstein CL. Sirolimus attenuates disease progression in an orthologous mouse model of human autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2010;78:754–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Walz G, Budde K, Mannaa M, Nurnberger J, Wanner C, Sommerer C, Kunzendorf U, Banas B, Horl WH, Obermuller N, Arns W, Pavenstadt H, Gaedeke J, Buchert M, May C, Gschaidmeier H, Kramer S, Eckardt KU. Everolimus in patients with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:830–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Serra AL, Poster D, Kistler AD, Krauer F, Raina S, Young J, Rentsch KM, Spanaus KS, Senn O, Kristanto P, Scheffel H, Weishaupt D, Wuthrich RP. Sirolimus and kidney growth in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:820–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sas KM, Kayampilly P, Byun J, Nair V, Hinder LM, Hur J, Zhang H, Lin C, Qi NR, Michailidis G, Groop PH, Nelson RG, Darshi M, Sharma K, Schelling JR, Sedor JR, Pop-Busui R, Weinberg JM, Soleimanpour SA, Abcouwer SF, Gardner TW, Burant CF, Feldman EL, Kretzler M, Brosius FC 3rd, Pennathur S. Tissue-specific metabolic reprogramming drives nutrient flux in diabetic complications. JCI Insight. 2016;1:e86976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Zschiedrich S, Bork T, Liang W, Wanner N, Eulenbruch K, Munder S, Hartleben B, Kretz O, Gerber S, Simons M, Viau A, Burtin M, Wei C, Reiser J, Herbach N, Rastaldi MP, Cohen CD, Tharaux PL, Terzi F, Walz G, Godel M, Huber TB. Targeting mTOR signaling can prevent the progression of FSGS. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;28:2144–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Nishizono R, Kikuchi M, Wang SQ, Chowdhury M, Nair V, Hartman J, Fukuda A, Wickman L, Hodgin JB, Bitzer M, Naik A, Wiggins J, Kretzler M, Wiggins RC. FSGS as an adaptive response to growth-induced podocyte stress. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;28:2931–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Bork T, Liang W, Yamahara K, Lee P, Tian Z, Liu S, Schell C, Thedieck K, Hartleben B, Patel K, Tharaux P-L, Lenoir O, Huber TB. Podocytes maintain high basal levels of autophagy independent of mtor signaling. Autophagy. 2020;16:1932–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Chen JK, Chen J, Thomas G, Kozma SC, Harris RC. S6 kinase 1 knockout inhibits uninephrectomy- or diabetes-induced renal hypertrophy. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2009;297:F585–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Bonucci M, Kuperwasser N, Barbe S, Koka V, de Villeneuve D, Zhang C, Srivastava N, Jia X, Stokes MP, Bienaime F, Verkarre V, Lopez JB, Jaulin F, Pontoglio M, Terzi F, Delaval B, Piel M, Pende M. mTOR and S6K1 drive polycystic kidney by the control of Afadin-dependent oriented cell division. Nat Commun. 2020;11:3200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Torras J, Herrero-Fresneda I, Gulias O, Flaquer M, Vidal A, Cruzado JM, Lloberas N, Franquesa M, Grinyo JM. Rapamycin has dual opposing effects on proteinuric experimental nephropathies: is it a matter of podocyte damage? Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2009;24:3632–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Yao Y, Wang J, Yoshida S, Nada S, Okada M, Inoki K. Role of ragulator in the regulation of mechanistic target of rapamycin signaling in podocytes and glomerular function. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;27:3653–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Tomita I, Kume S, Sugahara S, Osawa N, Yamahara K, Yasuda-Yamahara M, Takeda N, Chin-Kanasaki M, Kaneko T, Mayoux E, Mark M, Yanagita M, Ogita H, Araki SI, Maegawa H. SGLT2 inhibition mediates protection from diabetic kidney disease by promoting ketone body-induced mtorc1 inhibition. Cell Metab. 2020;32(404–19):e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Schaub JA, AlAkwaa FM, McCown PJ, Naik AS, Nair V, Eddy S, Menon R, Otto EA, Demeke D, Hartman J, Fermin D, O’Connor CL, Subramanian L, Bitzer M, Harned R, Ladd P, Pyle L, Pennathur S, Inoki K, Hodgin JB, Brosius FC 3rd, Nelson RG, Kretzler M, Bjornstad P. SGLT2 inhibitors mitigate kidney tubular metabolic and mTORC1 perturbations in youth-onset type 2 diabetes. J Clin Invest. 2023. 10.1172/JCI164486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ma T, Tian X, Zhang B, Li M, Wang Y, Yang C, Wu J, Wei X, Qu Q, Yu Y, Long S, Feng JW, Li C, Zhang C, Xie C, Wu Y, Xu Z, Chen J, Yu Y, Huang X, He Y, Yao L, Zhang L, Zhu M, Wang W, Wang ZC, Zhang M, Bao Y, Jia W, Lin SY, Ye Z, Piao HL, Deng X, Zhang CS, Lin SC. Low-dose metformin targets the lysosomal AMPK pathway through PEN2. Nature. 2022. 10.1038/s41586-022-04431-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Zoncu R, Bar-Peled L, Efeyan A, Wang S, Sancak Y, Sabatini DM. mTORC1 senses lysosomal amino acids through an inside-out mechanism that requires the vacuolar H(+)-ATPase. Science. 2011;334:678–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Shah OJ, Wang Z, Hunter T. Inappropriate activation of the TSC/Rheb/mTOR/S6K cassette induces IRS1/2 depletion, insulin resistance, and cell survival deficiencies. Curr Biol. 2004;14:1650–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Um SH, Frigerio F, Watanabe M, Picard F, Joaquin M, Sticker M, Fumagalli S, Allegrini PR, Kozma SC, Auwerx J, Thomas G. Absence of S6K1 protects against age- and diet-induced obesity while enhancing insulin sensitivity. Nature. 2004;431:200–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]