Highlights

-

•

Human respiratory syncytial virus is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality.

-

•

Viral culture, antigen detection, and molecular methods, can identify RSV.

-

•

Innate immune response determines the disease severity and viral infection outcome.

-

•

Nirsevimab and palivizumab protects against RSV in infants and young children.

-

•

Arexvy and abrysvo enhance immune response against RSV in adults and pregnant women.

Keywords: hRSV, Viral diagnosis, Pathogenesis, Immune response, Current vaccines against hRSV

Abstract

Human respiratory syncytial virus (hRSV) remains a leading cause of morbidity and mortality in infants, young children, and older adults. hRSV infection's limited treatment and vaccine options significantly increase bronchiolitis' morbidity rates. The severity and outcome of viral infection hinge on the innate immune response. Developing vaccines and identifying therapeutic interventions suitable for young children, older adults, and pregnant women relies on comprehending the molecular mechanisms of viral PAMP recognition, genetic factors of the inflammatory response, and antiviral defense. This review covers fundamental elements of hRSV biology, diagnosis, pathogenesis, and the immune response, highlighting prospective options for vaccine development.

1. Introduction

hRSV (human respiratory syncytial virus) is responsible for the highest rate of hospitalizations and substantial death among infants and young children due to lower respiratory tract infections (LRTIs) (Avendaño Carvajal and Perret Pérez, 2020; Li et al., 2021). In preschool children aged under 5, RSV results in 16 times more hospitalizations and emergency department visits as compared to influenza (Bont et al., 2016). Twenty-two percent of all global acute lower respiratory infection (ALRI) cases and approximately 3.6 million hospital admissions, as well as 26,300 deaths in 2019, were due to RSV (Li et al., 2022). Thirty-three million children under 5 years suffer from RSV-related acute lower respiratory infections annually, resulting in around 10% hospitalizations and approximately 200,000 deaths (Shi et al., 2015; Figueras-Aloy et al., 2016; Wingert et al., 2021). Globally, 1.4 million 0–6 month old children were admitted to hospitals for RSV-ALRTI in 2019, resulting in 13,300 deaths (Li et al., 2022). During serological tests, the majority of children had been infected with RSV by the age of 2, creating a significant healthcare concern (Anderson et al., 2022; Hassan et al., 2024). In 2017, approximately EUR 4.82 billion was spent globally on managing RSV-severe ALRI in pediatric patients (Del Riccio et al., 2023). Ten million dollars is the approximate median cost for hospitalizing children under the age of 5 infected with hRSV (Bhuiyan et al., 2017).

In children under 2 years of age, RSV-severe ALRI can be linked to maleness, low birth weight, prematurity, sibling presence, lack of breastfeeding, history of atopy, overcrowding, maternal smoking, and congenital heart disease (CHD) (Shi et al., 2017; Chida-Nagai et al., 2022). During each RSV epidemic season, the presence of two RSV subtypes, A and B, along with multiple genotypes, contributes to varying disease severity. Patients infected with RSV-A were statistically more likely to need both mechanical ventilation (p = 0.01) and intensive care (p = 0.008) than those infected with RSV-B (Vandini et al., 2017).

RSV, aside from its effect on children, is gaining recognition as a significant contributor to hospitalizations and mortality among the elderly aged 65 and above and frail older adults. In older adults, RSV infection can result in long-term respiratory tract disorders (LRTD), hospitalization, and death. Elderly people, specifically those who have diabetes, heart disease, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or weakened immune systems, are more vulnerable to severe RSV hospitalization. An estimated 214,000 (95% CI 100,000–459,000) annual hospitalizations from acute lower respiratory infections in adults aged 65 and above in industrialized countries could be attributed to RSV (Shi et al., 2020), whereas another study reported about 177,525 RSV hospitalizations annually in the USA for that age group (Falsey et al., 2005). In the US alone, the annual cost of treating hRSV infection in hospitals amounts to 394 million USD (Paramore et al., 2004). Thus, effective and safe vaccines for this virus are an urgent priority.

Primary infections usually cause upper respiratory symptoms and fever. Twenty-five to 40% of primary infections progress to the lower respiratory tract, with the primary manifestations of serious disease being bronchiolitis or pneumonia. Patients present with symptoms of rhinorrhea, cough, intermittent fever, and expiratory wheezes, frequently leading to middle-ear disease. Seriously ill infants require the administration of humidified oxygen due to increased coughing, wheezing, rapid respiration, and hypoxemia (Borchers et al., 2013). The population primarily contracts hRSV through inhalation of aerosolized droplets or direct contact with these droplets on the mucosa of the eye (Halfhide et al., 2011). During epidemic outbreaks, one strain of hRSV can cause multiple infections in individuals. Thirty-six perecent of individuals can be infected more than once in a season (Storey, 2010). The immune system's weakened response following the first encounter with the virus may cause subsequent reinfections (Watkiss, 2012).

Clinical specimens like nasal washes, nasopharyngeal swabs, and bronchoalveolar lavages can be used to diagnose RSV through various methods such as viral culture (conventional or shell vial), antigen detection, and molecular methods (viral RNA detection). The conventional culture method, considered the diagnostic gold standard for RSV infection, can take up to a week to produce results and offers limited sensitivity (Kuypers et al., 2006, 2009). Direct antigen testing, like direct immunofluorescence staining and shell vial culture techniques, offer 93% sensitivity and 97% specificity and provide results within 48 h, while real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) assays are more rapid with higher sensitivity and specificity for RSV infection diagnosis (Kuypers et al., 2006, 2009; Shah and Chemaly, 2011).

Prevention is the most effective approach to manage severe RSV infections, as treatment options are constrained. Discovering new RSV inhibitors is crucial for creating a viable RSV treatment. A single monoclonal antibody (palivizumab) was previously used for passive immunization in high-risk infants. The FDA has approved Arexvy and mRESVIA and Abrysvo (for older adults and pregnant individuals) and Nirsevimab-alip (the prevention of RSV in infants and young children) (Mullard, 2023; De et al., 2024). To date, 33 hRSV vaccine candidates are undergoing clinical trials across different populations, while numerous others are being developed preclinically and few are approved (Qiu et al., 2022; Mazur et al., 2023). Therefore, it is essential to comprehend RSV's impact on high-risk individuals for creating effective passive immunization products.

2. History of the hRSV

In 1955, at the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research (WRAIR), Washington, DC, USA, a respiratory illness causing coughing, sneezing, and mucopurulent discharge affected 20 chimpanzees. For the first time, a swab from a female chimpanzee's throat yielded the isolation of RSV, which later became known as the chimpanzee coryza agent (CCA) (Morris et al., 1956). Liver cells were the only ones inoculated with the virus that caused specific symptoms in chimpanzees.

In 1957, Chanock and colleagues isolated viruses resembling the causative agents of a child's pneumonia and croup in Baltimore (Chanock and Finberg, 1957; Chanock et al., 1957). Human respiratory syncytial virus (hRSV), which can form syncytia in cell culture and targets the human respiratory system, was given its name.

By the age of 4, most Baltimore children had already experienced a hRSV infection, according to serological findings. The hRSV has been linked to lower respiratory tract diseases in various regions and is now commonly associated with bronchiolitis and pneumonia in infants and preschool children (Collins et al., 1996). Approximately 95% of children experience their first hRSV infection before age 2, with the highest occurrence in the initial months (Anderson et al., 1990). Around 40% of kids exhibit symptoms of a lower respiratory tract infection during their first bout. Older children and adults generally experience milder symptoms upon reinfection (Hall et al., 1991).

Infants under 6 months, premature infants, immunodeficient children, and those with chronic lung or heart disease are at heightened risk for severe hRSV respiratory infections (Collins et al., 1996). Furthermore, studies link hRSV to severe infections in the elderly population (Falsey et al., 2005).

The hRSV is most inactivated in ether, chloroform, acidic environments (pH < 5), and at heat (55 °C). It weakly survives on porous surfaces and suffers reduced infectivity through slow freezing and storage above 4 °C (Proença-Módena et al., 2011).

3. Classification of RSV

RSV, which includes human, bovine, and murine strains, is a member of the Orthopneumovirus genus within the Pneumoviridae family and the Mononegavirales order (Davison, 2017). The two major antigenic subtypes of hRSV, A and B, primarily result from antigenic drift and sequence duplications in RSV-G, accompanied by significant genetic disparity across the entire genome, notably within RSV-F.

4. Genome, structure and life cycle of RSV

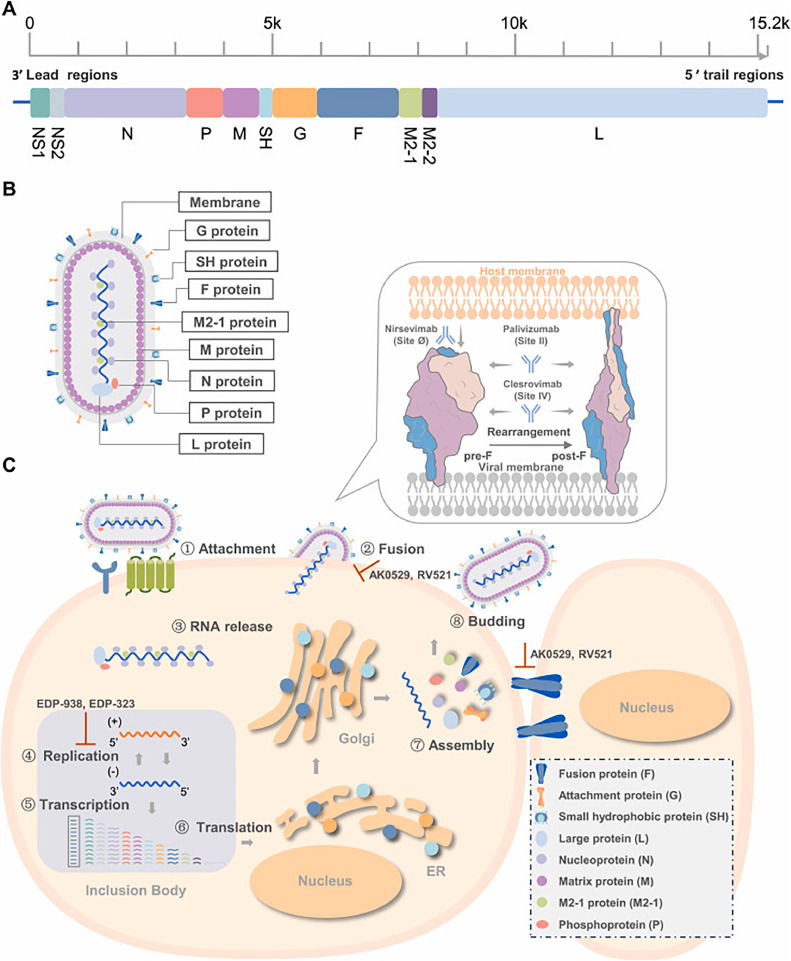

RSV is a non-segmented, negative-sense, single-stranded RNA virus with a 15.2 kb genome, encoding eleven proteins from the following ten genes in order from the 3′ to 5′ end: non-structural proteins (NS)1, NS2, nucleoprotein (N), phosphoprotein (P), matrix (M), small hydrophobic (SH), fusion (F), glycoprotein (G), M2, and large polymerase (L). The M2 gene encodes both the M2–1 and M2–2 proteins from two slightly overlapping open reading frames (Fig. 1A). The F, G, and SH proteins are located on the viral surface, while the N, P, L, M, and M2 proteins are situated beneath the viral envelope (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

Key targets in the RSV replication cycle. A. The RSV carries an RNA genome. 10 genes in the RSV genome encode for 11 proteins, with the M2 gene encoding for both M2–1 and M2–2 proteins. B. The respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) virion. The virion's filamentous structure is displayed. The M2–1 protein interacts directly with both the M and N proteins, while the large polymerase subunit (L) and phosphoprotein polymerase cofactor (P) bind to the N protein. The nucleocapsid, which consists of the RNA genome encased in N protein, is formed alongside the viral membrane, where attachment (G) and fusion (F) glycoproteins, small hydrophobic (SH) proteins, and the matrix (M) protein are embedded. C. RSV replication cycle and drug targets. The G protein initiates attachment by binding to cell surface factors, and the F protein aids in the nucleocapsid's entry into the cytoplasm. The F protein triggers viral and host membrane fusion by undergoing a significant conformational shift. In the inclusion body, the RSV polymerase complex, comprised of L and P proteins, produces both mRNAs and progeny genomes using the N-RNA complex as a template, with M2–1 assisting in transcription. The ER and Golgi apparatus synthesize, mature, and transport structural proteins. N protein plays a role in both the packaging of genomic RNA and the assembly of viral structures. Virus particles protrude from the cell membrane during the budding process. The process of fusion and replication is the primary target for inhibitor intervention. Reprinted with permission from (Zou et al., 2023). Copyright (2023) Elsevier B.V.

Understanding the RSV life cycle is crucial for creating effective antiviral medications. In Fig. 1C, RSV's replication cycle initiates with attachment to host cells via viral glycoprotein G bonding to cellular receptors (Teng et al., 2001). Multiple receptors and attachment factors for RSV have been discovered, consisting of heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPGs) (Feldman et al., 1999), intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) (Behera et al., 2001), CX3C chemokine receptor 1 (CX3CR1) (Tripp et al., 2001), nucleolin (Tayyari et al., 2011), epidermal growth factor (EGFR) (Currier et al., 2016), and insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor (IGF1R) (Griffiths et al., 2020). The G protein facilitates the virus's binding to host cells. The F protein facilitates the entry of the viral ribonucleoprotein into the cytoplasm by fusing the viral envelope with the host cell membrane. During RSV infection, inclusion bodies (IBs) function as the main sites for the viral RNA polymerase to produce both genomic and messenger RNA (Rincheval et al., 2017). Around 10–12 h post-infection, virus particles are synthesized, assembled, and released from the infected cell via budding at the plasma membrane, while intracellular mRNAs and proteins can be detected 4–6 h post-infection (PL, 2007). During an RSV infection, respiratory epithelial cells merge into multinucleated syncytia.

Examining the high-resolution structures of RSV F protein in its prefusion and postfusion forms, as well as the polymerase complex, sheds light on the intricacies of viral entry and replication processes (McLellan et al., 2013). The F0 precursor is cleaved by Furin-like host proteases into pep27 (27 amino acids), the F2 subunit, and the F1 subunit, which carries a fusion peptide at the N-terminus. The F1 and F2 subunits connect via two disulfide bonds to form a single protomer, which further assembles as a trimer. During the fusion process, the F protein transforms from its metastable prefusion state to a stable postfusion state (Harshbarger et al., 2020). Six antigenic sites, specifically Ø and V on pre-F and I-IV on both pre- and post-F, have been recognized in the RSV F protein (McLellan et al., 2011).

The RdRp (RNA-dependent RNA polymerase) complex, consisting of the catalytic core and cofactors L and P, promotes RSV RNA synthesis. Within the RdRp complex, the L protein encapsulates all pivotal enzymatic sities for RNA synthesis, polyadenylation, capping, and cap methylation (Fearns and Plemper, 2017). The L protein has five (RdRp, capping (Cap), connector domain (CD), cap methyltransferase (MT) domain, and C-terminal domain (CTD) domains:, while the P protein has three: N-terminal domain (NTD), oligomerization domain (OD), and CTD (Cao et al., 2020). The RdRp comprises the palm, fingers, thumb, and a putative structural support subdomain (Gilman et al., 2019). The tetrameric P protein plays a crucial role in forming an active RNA polymerase with L. The priming and supporting loops of RdRp undergo significant conformational shifts during the transition from RNA initiation to elongation in the polymerase (Ouizougun-Oubari and Fearns, 2023). Given the necessity of RdRp activity for viral replication and its absence in human cells, it constitutes an optimal target for antiviral drug development. Insights into the structure of viral replication and transcription will pave the way for the creation of novel therapeutics

5. Risk factors for hRSV

Prematurity, low birth weight (< 2.500 g), genetic and chromosomal abnormalities, underlying immunologic disorders, cardiopulmonary comorbidity, neoplasia, and immunodeficiency are linked to severe RSV bronchiolitis (Griffiths et al., 2017; Xing and Proesmans, 2019).

Preterm infants, having missed the third trimester maternal IgG transfer, face an increased risk of severe RSV infection (Meissner, 2016). Young children's smaller bronchial lumens and larger surface area-to-volume ratios increase their susceptibility to severe RSV infection (Griffiths et al., 2017).

Environmental factors contributing to RSV infection include smoke exposure from cooking and tobacco, low socioeconomic status, and overcrowding (Griffiths et al., 2017; Xing and Proesmans, 2019).

6. Pathogenesis and pathology of hRSV

The virus can enter the lower respiratory tract through the nasopharynx via aerosol particles or direct contact (Piedimonte and Perez, 2014; Battles and McLellan, 2019). During viral replication, the G-protein facilitates attachment of hRSV to ciliated epithelial cells through the CX3CR1 receptor, and the pre-F protein mediates the viral envelope fusion with the host cell membrane for entry via endocytosis (Tayyari et al., 2011; Zhivaki et al., 2017). The RdRp complex (RdRp, large protein-L, and phosphoprotein-P) facilitates the replication of the viral genome within cytoplasmic inclusion bodies (Sourimant et al., 2015). The M2–1 protein of the virus functions as a cofactor during transcription by joining the complex (Sourimant et al., 2015; Braun et al., 2021).

NF-κB and IFN response factors initiate the early immune response (Zeng et al., 2012) via various receptors, such as epidermal growth factor (EGF) (Weigl et al., 2001), intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1) (Law et al., 2004), annexin II (Fjaerli et al., 2004), calcium-dependent lectins (Fjaerli et al., 2004), and heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPGs) (Bradley et al., 2005). Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) binds to the F protein on bronchial (Marzec et al., 2019) and epithelial cells (Park et al., 2012), initiating innate immune response upon hRSV entry (Funchal et al., 2015). TLR4 triggers endocytosis by activating kinases to facilitate viral entry (Piedra et al., 2003). The CX3 chemokine receptor 1 (CX3CR1) (Anderson et al., 2020) present on the apical side of ciliated bronchial epithelial cells interacts with the G protein (Anderson et al., 2021). Mice deficient in CX3CR1 exhibit reduced susceptibility to virus infection due to the absence of an interaction between RSV-G and CX3CR1 that alters chemotaxis signaling (Anderson et al., 2020, 2021). Nucleolin has been reported to bind to the F protein (Nielsen et al., 2003). In dividing cells, the high surface expression of nucleolin could be significant in causing children's LRTIs (Ochola et al., 2009).

The inflammatory host immune response primarily causes airway damage in the bronchi and bronchioles (Meissner, 2016; Griffiths et al., 2017), leading to lower airway obstruction due to swelling, mucus, and cell debris instead of bronchospasm (Xing and Proesmans, 2019).

Humoral immune response and Th1 cell-mediated response collaborate to generate neutralizing antibodies that prevent RSV infection, control viral replication, and promote clearance(Meissner, 2016; Griffiths et al., 2017).

Childhood LRTI caused by RSV is associated with subsequent recurrent wheezing and asthma (Griffiths et al., 2017).

7. Clinical features of hRSV

hRSV symptoms typically appear 3–7 days after infection, starting with a mild upper respiratory infection (URI) before potentially developing into severe lower respiratory infections such as pneumonia, bronchiolitis, tracheobronchitis, and croup. Bronchiolitis, following a URI, commonly presents with symptoms such as rapid breathing, labored breathing, cough, expiratory wheezing, air trapping, intercostal muscle retractions, and cyanosis. Approximately half of the patients show fever, while imaging reveals signs of lung hyperaeration and segmented atelectasis. In acute otitis media linked to hRSV infection in children, blood tests reveal lymphocytosis and neutrophilia, and 75% of middle ear effusions contain hRSV RNA. In tropical climates, children with weakened immune systems stand a greater chance of developing severe bacterial infections upon contracting hRSV (Proença-Módena et al., 2011).

Children with premature birth, congenital heart disease, underling pulmonary conditions such as cystic fibrosis and bronchopulmonary dysplasia, immunocompromised individuals, and HIV-infected children, though susceptible to severe hRSV infections, do not necessarily experience heightened disease severity. Instead, HIV-infected children exhibit increased rates of pneumonia, prolonged illness, and virus shedding. Acute bronchiolitis can be distinguished from asthma, pneumonia, congenital heart and lung diseases, and cystic fibrosis through differential diagnosis. In children over 3 and adults, hRSV frequently causes URI symptoms with a low-grade fever. Chronic pulmonary diseases in adults can also manifest with exacerbations and wheezing episodes. In severe hRSV infections, neurological complications such as seizures and encephalopathy are uncommon but can necessitate intensive care. hRSV, like influenza and parainfluenza, can trigger wheezing and asthma attacks in infants. Interstitial pneumonia in the elderly with chronic pulmonary conditions has seen a rise in hRSV cases, characterized by prolonged coughing and dyspnea (Proença-Módena et al., 2011).

8. Diagnosis of hRSV

Diagnosis can be challenging when a disease's symptoms overlap with those of other diseases or it is asymptomatic (Svraka et al., 2010; Bawage et al., 2013). Therefore, the diagnosis must be determined through observation and experience for effective treatment. Methods are detailed below for accurately diagnosing RSV using molecular and biophysical methods (Table 1).

Table 1.

Comparison of RSV detection techniques.

| Detection methods | Technique | Principle | Advantages | Drawbacks | Current usage status | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fluorescence based methods | DFA | Detecting RSV at the microscopic level involves using antibodies conjugated with a fluorophore for specific identification | Simple technique | The errors committed by humans and the faded colors are the issues | Under further investigation, at Hospital, and commercial available technique | (Jartti et al., 2013) |

| QDs | Fluorescent nanoparticles can be detected via microscopy or flow cytometry upon interaction with RSV | The photostable inorganic compound remains unchanged despite metabolic processes | Harmful, insolubility | Under investigation | (Tripp et al., 2007; Chen et al., 2010) | |

| Molecular beacon based imaging | Gold nanoparticles, functionalized with hairpin DNA and fluorophore, bind to target mRNA | Real-time imaging of live cells | Silencing and metabolic degradation are likely causes | Under investigation | (Santangelo et al., 2004; Jayagopal et al., 2010) | |

| Immunoassays | ELISA | Antigen-antibody complex can be specifically detected and measured through colorimetric methods | The protocol is simple yet produces accurate results | Often inefficient and error-prone due to their complexity | At Hospital,and commercial available technique | (Rochelet et al., 2012) |

| OIA | The formation of an antigen-antibody complex visibly alters the reflective properties of their surfaces | The test offers simplicity, quickness, precision, and affordability | Other tests are required to affirm the negatives | Under further investigation | (Aldous et al., 2005) | |

| LFIA | Chromatographic identification of immune complexes | An FDA-approved option that is both convenient and affordable | Detection is non-quantitative and influenced by sample volume limitations | At Hospital,and commercial available technique | (Slinger et al., 2004) | |

| Molecular methods | LAMP | The colorimetric/turbidimetric method detects isothermal amplification of DNA using specific primers | Sensitivity and specificity | A semiquantitative approach is employed for designing primer sets | Under further investigation | (Mahony et al., 2013) |

| PCR | Visualizing PCR product after amplifying viral cDNA | Faster and more responsive than traditional culture techniques | Detected pathogens at high limits | Under further investigation, and at Hospital | (Jartti et al., 2013) | |

| Real-Time -PCR | Amplifying target DNA or cDNA in real-time | 3–5 hour test, highly sensitive and with ultra-low detection limits | Costy | Under further investigation, at Hospital, and commercial available technique | (Kuypers et al., 2004) | |

| Multiplex PCR | Use of multiple primer and/or probe sets | Concurrent identification of several disease-causing pathogens or their strains | Insensitive | Under further investigation, and at Hospital, | (Choudhary et al., 2013) | |

| Immuno-PCR | Immunoassay and real-time real-time PCR are used in combination | The detection limits of this method are significantly lower than individual ELISAs, with improvements of 4000 and 4-fold for PCR and ELISA, respectively | Following complicated experimental fassion | Under further investigation | (Niemeyer et al., 2005; Perez et al., 2011) | |

| Microarray | Biomolecules attach to immobilized DNA or protein targets on a chip | The technology is capable of identifying numerous pathogens, both through protein and nucleic acid detection, in a large scale and sensitive manner | Costy | Research intent, hospital based procedure, commercial assay | (Chiu et al., 2008) | |

| Biophysical method | PCR-ESI-MS | Mass spectrometry analyzes PCR amplicons using electron spray dispersion | The assay demonstrates high sensitivity, specificity, and efficiency for detecting multiple pathogens at strain levels | Costy | Under further investigation | (Sampath et al., 2007; Chen et al., 2011) |

| SERS | Monochromatic radiation undergoes inelastic scattering when it interacts with an analyte bearing low-frequency vibrational and/or rotational energy | Detecting analytes at a fast and undamaging rate with high sensitivity | Sample preparation | Under further investigation | (Shanmukh et al., 2008) |

9. Innate immune response to hRSV

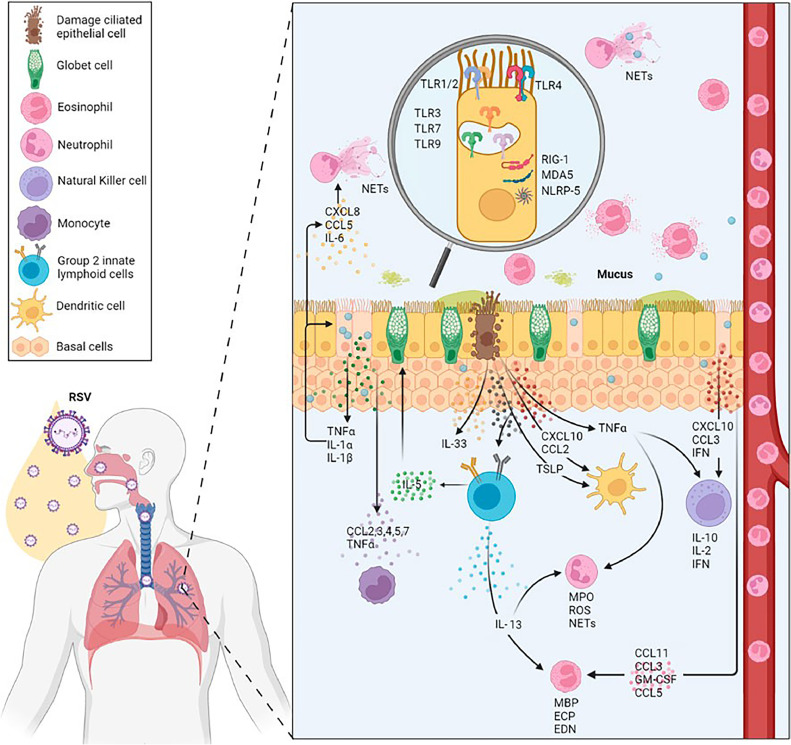

hRSV infection triggers multiple immune responses, including involvement of airway epithelial cells, dendritic cells, macrophages, monocytes, granulocytes, and pattern recognition receptors, such as TLRs, RIG-I-like receptors (RLRs), and NOD-like receptors (NLRs) (Zeng et al., 2012; Lachaud et al., 2017)(Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

The local human immune response to hRSV involves the production of type I interferons, recruitment of neutrophils, and production of antibodies. These cells, including neutrophils, dendritic cells, macrophages, and eosinophils, are the primary ones affected by hRSV infection. The response of cytokines, chemokines, and other immune molecules to local immune production is determined by their location and modulation in the infection process. During infection, the activated PRRs (TLR2, 3, 4, 7, and 9) are featured at the innate immune level. Reproduced with permission from Frontiers Publishing Partnership (Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License) (Correa et al., 2023).

Airway epithelial cells detect viral PAMPs using distinct PRRs, triggering an early immune response (Lay et al., 2013). Through MyD88 and TRIF (Kumar et al., 2011), interferon-regulatory factor 3 (IRF-3), nuclear factor κB (NF-κB), and ATF-2/cJun were activated. The mentioned elements primarily facilitate the transcription of antiviral genes, dendritic cell activation, and the generation of soluble cytokines and chemokines by dendritic cells and macrophages in the alveoli (Goritzka et al., 2015; Lay et al., 2016; Feng et al., 2018).

TLR4 interacts with hRSV F protein via CD14, resulting in NF-kB activation, innate immune responses, and inflammation (Kurt-Jones et al., 2000). TLR-4 and NF-κB pathways mediate the enhanced activation and release of Transglutaminase 2 from human lung epithelial cells upon RSV-induced oxidative stress (Rayavara et al., 2022). The function of transglutaminase 2 in hRSV infection is yet to be clarified, while TLR-2 manages pro-IL-1β and NLRP3 gene activation during RSV illness. During RSV infection, the activation of TLR2 initiates the formation of NLRP3 inflammasome, resulting in caspase-1 activation and IL-1β release (Segovia et al., 2012).

TLR7 and TLR3 recognize ssRNA and dsRNA, respectively, within endosomal compartments (Aeffner et al., 2011). Upon hRSV infection, TLR3 signaling pathways are activated, leading to the expression of MyD88-independent chemokines IP-10/CXCL10 and CCL5, while also upregulating TLR3 expression in infected cells (Rudd et al., 2005). TLR3 activation during hRSV infection promotes a Th1-type immune response essential for adaptive immune response initiation (Rudd et al., 2006), while TLR7 is crucial for RSV detection and immune response initiation. Classical and plasmacytoid dendritic cells acknowledge RSV via TLR7, leading to an antiviral reaction and immunomodulation (Smit et al., 2006; Lukacs et al., 2010). A study showcased the regulatory role of TLR7 in dendritic cells' IL-12/IL-23 responsiveness to RSV, with TLR7-deficient dendritic cells producing significantly less IL-12 but more IL-23 upon RSV stimulation (Lindell et al., 2009). Dendritic cells produce interferon-β during RSV infection, enhancing initial antiviral activities (Kim et al., 2019).

Upon hRSV infection, airway epithelial cells generate pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as type-I and III interferons, which, upon binding to their receptors, activate signaling pathways via STAT-1 and STAT-2, leading to the binding of STAT to IFN-regulatory factors in ISGs. Several pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, including IL-6, interferon-alpha (INF-α), CXCL8, CCL3, CCL2, and CCL5, are induced and secreted. These chemokines, CCL2 and CCL5, recruit monocytes, neutrophils, dendritic cells, macrophages, natural killer cells, and CD4+ T cells to infection sites (Lay et al., 2016; Aronen et al., 2019) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Function of immune molecules during the infection.

| Molecules | Response |

|---|---|

| CX3CR1 | The viral G-protein interaction facilitates viral entry |

| MyD88 and TRIF | The early immune response triggers the activation of transcription factors |

| IRF-3, NF-κB and ATF2/cJun | Triggering the transcription of antiviral genes, DC activation, and the generation of pro-inflammatory cytokines |

| TLR2 | Regulates expression of pro-IL-1b and NLRP3 genes |

| TLR3 | In endosomes, intermediates regulate viral replication, control MyD88 expression, and elicit a Th1-response profile |

| TLR4 and CD14 | Attach to viral F-protein |

| TLR7 | In endosomes, viral genome recognition leads to regulation of IL-12/IL-23 responsiveness |

| NLRP3 | Activate caspase-1 to release IL-1b |

| IFN-II and IFN-III | STAT-1 and STAT-2 are responsible for activating signaling pathways |

| STAT | Bonds with IFN-regulatory elements in ISGs |

| CCL2 and CCL5 | Boost the arrival of monocytes, neutrophils, dendritic cells, macrophages, natural killer cells, and CD4+ T cells towards the infection site |

Airway epithelial cells in vitro secrete IL-1β, IL-6, INFα, macrophage inflammatory protein-1a (MIP-1a/CCL3), monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1/CCL2), RANTES/CCL5, eotaxin/CCL11, IL-8/CXCL8, monokine induced by interferon-gamma (IFNγ) − (MIG/CXCL9), IP-10/CXCL10, and fractalkine/CX3CL1 (Miller et al., 2004; Mochizuki et al., 2009; Villenave et al., 2011). The controversy remains over the impact of cytokine production during hRSV infection (Tayyari et al., 2011; Villenave et al., 2012). When exposed to the same strain of the virus, cell lines produce different cytokine profiles than primary cells (Fonceca et al., 2012). Cells from different donors distinctly change the profile. The epithelial cells' localization in the airways influences both their constitutive production and the upregulation of cytokines (Correa et al., 2023).

In bronchiolitis-affected infant airways, hRSV infection triggers a neutrophil-dominated inflammatory response (Habibi et al., 2020). In severe RSV infection in infants, the virus directly interacts with neutrophils, as evidenced by the presence of RSV N genomic RNA in both BAL and their blood (Halfhide et al., 2011). In response, neutrophils release myeloperoxidase (MPO), elastase, defensins, and other toxic substances as cytokines and granular enzymes. During viral infections, ROS are released into the extracellular milieu. Neutrophils in the BAL fluid of ventilated children form neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) during infection. NETs trap RSV, inhibiting its ability to bind and infect cells. Net overproduction triggers immunopathology in hRSV-infected patients (Liegl et al., 2008).

After hRSV exposure, eosinophils also produce superoxide. After exposure to hRSV, eosinophil cationic protein (ECP) and eosinophil-derived neurotoxin (EDN) decreased its infectivity, demonstrating their antiviral properties. Myelin basic protein (MBP) induces the death of hRSV-infected epithelial cells (Glaser et al., 2019).

10. Evasion mechanisms of hRSV

Poor immune control has been linked to various underlying mechanisms. Balancing Th1 and Th2 responses optimally enhances hRSV clearance through IFNγ generation by CD8+ cells (Schmidt et al., 2018). hRSV infection does not seem to elicit a protective memory response against future exposures. In recovery, there's a deficiency in IgA-producing memory B cells, not in IgG-producing ones, which could be a factor for repeated infections, particularly in children (Russell et al., 2017).

The proper assembly of the immunological synapse between antigen-presenting cells (APC), such as dendritic cells and T cells, is hindered by hRSV. The virus impairs T cells' ability to react appropriately, enhancing their susceptibility to repeated infections through the adaptive immune system (González et al., 2008). Dendritic cells, though infected with hRSV and impeded in their maturation process, continue to present antigens and stimulate T cells. The NS1 and NS2 proteins of the infection prevent IFN production by inhibiting the formation of the immune synapse and generating inhibitory factors (Collins and Graham, 2008; Watkiss, 2012). An immature or hypofunctional immune system in neonates and young infants increases their susceptibility to RSV infection. Neonatal macrophages display decreased PRR expression and/or lower cytokine production upon activation (Basha et al., 2014). hRSV strains exhibit less antigenic diversity than other respiratory viruses. Reinfections with hRSV can occur throughout life due to incomplete and short-lived immunity. Despite its mechanisms of evasion, the immune response against hRSV is hindered (Watkiss, 2012). The heavily glycosylated G and F proteins of the virus generate neutralizing antibodies that hinder antibody recognition (Palomo et al., 2000). The central conserved domain of the G protein contains a CX3C motif with chemokine fractalkine-like activity (Jartti et al., 2009). The activation of NF-κB and cytokine production in human monocytes is suppressed, indicating an immune-inhibiting effect (Levine et al., 2004). The secreted form of G protein reportedly hinders the TLR3/4-triggered IFN-beta response in vitro (Shingai et al., 2008), possibly suppressing the innate immune system.

The F protein crucial for attachment, fusion, and syncytia formation interacts with the hRSV receptor, nucleolin (Sun et al., 2013). The protein triggers an innate immune response through TLR4 on leukocytes and epithelial cells, resulting in p53-dependent apoptosis (Freymuth et al., 2006). The INF-α pathway implicates the SH protein in inhibiting apoptosis (Stockman et al., 2012; Zhou et al., 2012)

G protein was produced in both membrane-bound full-length and secreted truncated forms. The protein decoys neutralizing antibodies (Watkiss, 2012). The CX3C motif of the protein is responsible for its chemotactic activity through the CX3CR1 receptor, similar to that of fractalkine (CX3CL1). The impact of this capacity on in vivo leukocyte recruitment to infected lungs remains uncertain (Collins and Graham, 2008). Studies have shown that the G protein can stimulate certain T cell clones to secrete IL-4 and IL-10, whereas T cells specific to the F protein initiate a Th1 immune response akin to the immune response elicited by whole hRSV. The G protein may hinder cellular immunity and elicit a negative immune response, opposing TLR signaling (Collins and Graham, 2008; Watkiss, 2012).

11. Immune response of TH1-TH2 during hRSV infection

The analysis of cytokine profiles in primary hRSV infection in children has yielded variable results. Some studies did not find IFNγ levels to increase in mitogen-stimulated peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) (Bendelja et al., 2000; Pinto et al., 2006). The production level of this cytokine was lower than that of other respiratory infection agents (Aberle et al., 2004).

While some studies suggest a Th2 dominance with concurrent upregulation of Th2 cytokines (Bendelja et al., 2000; Gut et al., 2013), others could not detect IL-4 or IL-5 production (Pinto et al., 2006). Despite other evidence suggesting a protective role for IFNγ, determining its specific role in PBMC and its correlation with disease severity is challenging (Bendelja et al., 2000). In RSV-hospitalized patients, PBMC stimulated by RSV demonstrate a balanced Th1 and Th2 immune response, indicated by the expression of Th1 and Th2 cytokines and augmented production of IL-2, IL-4, and IL-13 (Tripp et al., 2002). The study reported higher levels of IFN-gamma compared to IL-4 and IL-10, but no correlation to clinical severity was detected (Brandenburg et al., 2000).

While hRSV RNA can be found in blood monocytes and neutrophils, its infection remains confined to the respiratory system (Halfhide et al., 2011). Through analysis of PBMCs, hRSV-specific CD8+ T cells were detected in the blood with demonstrable differences in number compared to the respiratory tract, indicating their active recruitment into the tissue (Heidema et al., 2008). In children with ventilation, cytokine levels in the upper respiratory tract exhibit a stronger or moderately stronger correlation than those in the lower respiratory tract (Semple et al., 2007). During acute hRSV infection, IFNγ production is greater than in healthy controls (Kim et al., 2012) or bronchiolitis patients unrelated to hRSV(Bennett et al., 2007). In some studies, IFNγ production was low or undetectable (Kristjansson et al., 2005).

Some studies have reported high Th2 cytokine levels (Legg et al., 2003), whereas others have found low or undetectable levels comparable to control groups (Bont et al., 2001; Pinto et al., 2006; Kim et al., 2012). Patients with lower respiratory tract infection exhibit a Th2-skewed response compared to those with upper respiratory tract infection (Legg et al., 2003). Some studies suggest a shift towards a Th2 response in upper respiratory tract infections and hypoxic bronchiolitis (Garofalo et al., 2001). In bronchiolitis patients, excessive IFN-γ release in the airway is the result of an immunologic imbalance triggered by viral infection (van Schaik et al., 1999). Significant differences in the Th1 and Th2 cytokine expression profiles have been identified through cytokine mRNA analysis (Mobbs et al., 2002). This study found that hRSV infection in infants stimulated a Th2-like response in the nose, accompanied by local production of IL-4, IL-5, macrophage inflammatory protein 1b, and eosinophil infiltration and activation (Kristjansson et al., 2005).

The production of IFNγ and IL-12 displays age-dependent variation, with the responsiveness to IL-12 influencing type 1 immune responses (Buck et al., 2002; Motegi et al., 2006; Yerkovich et al., 2007). Both IL-12 and IL-18 independently contribute to the induction of IFNγ and offer protection against bronchiolitis (van Benten et al., 2003). In mouse models of hRSV infection, it's uncertain if increased IL-4 production and decreased IFNγ production have significance (Culley et al., 2002; Dakhama et al., 2005). The impact of disease severity on the lower respiratory tract following a first infection and the immune response during secondary infections remains uncertain (Chung et al., 2005). In certain cohorts, IL-10 levels are higher, whereas in others, they are comparable. In acute infection, IL-10 production might be associated with atopy (Chung et al., 2005). Some reports dispute the link between the two (Joshi et al., 2003).

The correlation between nasopharyngeal or tracheal IL-10 levels and disease severity is strong (Sheeran et al., 1999; Bennett et al., 2007; Vieira et al., 2010). IL-10′s pro-inflammatory and regulatory functions could partly explain the researchers' conflicting findings. The timing and intensity of production can impact its protective or detrimental effect. The particular hRSV strains' methodological concerns and unequal IL-10 induction ability might impact the study outcomes (Lukacs et al., 2006).

During the early phase of RSV infection in mice, IL-13 production is robustly observed regardless of Th1/Th2 response. During RSV infection, Group 2 innate lymphoid cells mediate IL-13 production in various pulmonary diseases, contributing to immunopathology (Stier et al., 2016).

12. Animal models to understand the immune response against hRSV

To understand the human immune response against hRSV, various animal models have been essential, but none provide a comprehensive representation. Animals such as cotton rats, mice, ferrets, guinea pigs, hamsters, chinchillas, neonatal lambs, bovines, chimpanzees, African green monkeys, and macaques have been employed as research models (Taylor, 2017). However, only chimpanzees exhibit symptomatic hRSV infection among nonhuman primates due to their permissiveness to the virus (Teng et al., 2000). Green monkeys are more resistant to the virus compared to chimpanzees, but viral load can reliably determine infection levels (Ispas et al., 2015).

In the context of hRSV infection, mice serve as a prominent model for vaccine development and understanding the underlying mechanisms of immunopathology (Andersen and Winter, 2017; Mazur et al., 2018). In this model, Th2 cytokines (IL-4, IL-10, IL-13, and CCL5) were upregulated, indicating Th2 immune response polarization (Sawada and Nakayama, 2016).

Understanding the infection's pathology and vaccine development relies heavily on using animal models. Studies highlight the lack of a consistent animal model for predicting the morbidity and mortality of human hRSV infection. The significance of researching infected humans cannot be overstated (Altamirano-Lagos et al., 2019).

13. Current information on vaccines against hRSV and concerns

Infants, pregnant women, and older adults are the groups targeted for hRSV vaccination. Thirty-three hRSV vaccine candidates, using 6 platforms, are in various clinical trial phases, including 9 in pivotal phase III and 3 FDA-approved. These vaccines include particle-based, vector-based, live-attenuated, chimeric, subunit, mRNA, and monoclonal antibody types (Qiu et al., 2022; Mazur et al., 2023).

The target populations consist of pediatric, maternal, and older adult groups. Pediatrics employ passive immunoprophylaxis using monoclonal antibodies that provide immediate protection against RSV such as (Nirsevimab (Beyfortus) − preventing RSV-LRTI in infants and children up to 24 months and Palivizumab (Synagis®) −recommended for high-risk infants and young children), live attenuated vaccines, and maternal antibodies; maternal subunit vaccines are under advanced studies to safeguard infants; older adults are protected using vector, subunit, and nucleic acid approaches (Mazur et al., 2023).

In May 2023, the first hRSV vaccine for adults aged 60 and older was approved by the FDA (FDA, 2023a) for preventing RSV-induced lower respiratory tract diseases (LRTD). An 82.6% (96.95%; CI: 57.9–94.1) efficacy in adults aged 60 and above was demonstrated in the landmark phase III AReSVi-006 trial of the AS01Eadjuvanted RSV prefusion F protein-based vaccine (RSVPreF3 OA) from GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) (Papi et al., 2023). Moderna also developed the mRNA-based RSV vaccine called mRESVIA, which is approved by the FDA and is indicated for active immunization for the prevention of LRTD caused by RSV in individuals 60 years of age and older with 83.7% efficacy (95% CI: 66.0% to 92.2%) and was used in the phase 3 ConquerRSV clinical trial (NCT05127434) that involved approximately 37,000 adults aged 60 and older across multiple countries (https://www.fda.gov/vaccines-blood-biologics/vaccines/mresvia). The Pfizer vaccine ABRISVOTM, a RSV A and RSV B prefusion F protein which has an 85.7% (96.66%; CI: 32.0–98.7) vaccine efficacy and was used in the RENOIR phase 3 clinical trial (NCT05035212) that enrolled 35,971 participants, has recently received approval from the FDA for use in older adults (Walsh et al., 2023). It is also the first vaccine approved for pregnant individuals to prevent LRTD and severe LRTD in infants from birth through 6 months caused by RSV. Abrysvo also used during pregnancy from week 32 to 36 (FDA, 2023b; Fleming-Dutra, 2023). These are vaccines that stimulate the body's immune system to produce antibodies against RSV. Actually, extensive research over the years has led to current vaccines that can significantly decrease the global prevalence, health, and financial impact of hRSV infections.

Wide range of efficacies (35–90%) observed in the RSV vaccines, resistance issues (large-scale deployment of vaccines poses a significant risk of selecting for resistant viruses, for example, presatovir (Gilead), for which resistance was found in 10–30% of treated patients (dose dependent), and cost and affordability (high costs can hinder vaccine distribution in low- and middle-income countries) are the major concerns of the RSV vaccine.

14. Conclusions

During hRSV infection, the innate immune response plays a critical role. HRSV has been shown to modulate immune responses through PRR activation, cytokine induction, antiviral response, and the shape of adaptive immunity. During viral infections, local and systemic immune responses, including the role of Th1 and Th2 responses, contribute to pathogenesis with varying degrees. Developing new therapeutics for hRSV infection requires an understanding of the immune response it generates. These advancements could significantly improve vaccine development for all demographics, mitigating the impact of RSV infection on public health. Currently, Nirsevimab (Beyfortus) and Palivizumab (Synagis) provide immediate protection against RSV in infants and young children, while Arexvy and mRESVIA and Abrysvo stimulate the body's immune system to produce antibodies against RSV in adults and pregnant women, respectively.

Funding

This research did not receive any financial support.

Declaration of use of AI in scientific writing

None.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Abayeneh Girma: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Resources, Investigation, Data curation, Conceptualization.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

None.

Data availability

No data was used for the research described in the article.

References

- Aberle J., Aberle S., Rebhandl W., Pracher E., Kundi M., Popow-Kraupp T. Decreased interferon-gamma response in respiratory syncytial virus compared to other respiratory viral infections in infants. Clin. Exper. Immunol. 2004;137:146–150. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2004.02504.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aeffner F., Traylor Z.P., Yu E.N., Davis I.C. Double-stranded RNA induces similar pulmonary dysfunction to respiratory syncytial virus in BALB/c mice. Am. J. Physiol.-lung cell. Mole. Physiol. 2011;301:L99–L109. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00398.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aldous W.K., Gerber K., Taggart E.W., Rupp J., Wintch J., Daly J.A. A comparison of Thermo Electron™ RSV OIA® to viral culture and direct fluorescent assay testing for respiratory syncytial virus. J. Clin. Virol. 2005;32:224–228. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2004.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altamirano-Lagos M.J., Díaz F.E., Mansilla M.A., Rivera-Pérez D., Soto D., McGill J.L., Vasquez A.E., Kalergis A.M. Current animal models for understanding the pathology caused by the respiratory syncytial virus. Front. Microbiol. 2019;10:873. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.00873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen M.L., Winter L.M. Animal models in biological and biomedical research-experimental and ethical concerns. Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências. 2017;91 doi: 10.1590/0001-3765201720170238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson C.S., Chirkova T., Slaunwhite C.G., Qiu X., Walsh E.E., Anderson L.J., Mariani T.J. CX3CR1 engagement by respiratory syncytial virus leads to induction of nucleolin and dysregulation of cilium-related genes. J. Virol. 2021;95 doi: 10.1128/JVI.00095-21. 10.1128/jvi. 00095-00021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson C.S., Chu C.-Y., Wang Q., Mereness J.A., Ren Y., Donlon K., Bhattacharya S., Misra R.S., Walsh E.E., Pryhuber G.S. CX3CR1 as a respiratory syncytial virus receptor in pediatric human lung. Pediatr. Res. 2020;87:862–867. doi: 10.1038/s41390-019-0677-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson J., Oeum M., Verkolf E., Licciardi P.V., Mulholland K., Nguyen C., Chow K., Waller G., Costa A.-M., Daley A. Factors associated with severe respiratory syncytial virus disease in hospitalised children: a retrospective analysis. Arch. Dis. Child. 2022;107:359–364. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2021-322435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson L.J., Parker R.A., Strilms R.L. Association between respiratory syncytial virus outbreaks and lower respiratory tract deaths of infants and young children. J. Infect. Diseases. 1990;161:640–646. doi: 10.1093/infdis/161.4.640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aronen M., Viikari L., Kohonen I., Vuorinen T., Hämeenaho M., Wuorela M., Sadeghi M., Söderlund-Venermo M., Viitanen M., Jartti T. Respiratory tract virus infections in the elderly with pneumonia. BMC Geriatr. 2019;19:1–11. doi: 10.1186/s12877-019-1125-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avendaño Carvajal L., Perret Pérez C. Pediatric Respiratory diseases: a Comprehensive Textbook. 2020. Epidemiology of respiratory infections; pp. 263–272. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Basha S., Surendran N., Pichichero M. Immune responses in neonates. Expert Rev. Clin. Immunol. 2014;10:1171–1184. doi: 10.1586/1744666X.2014.942288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battles M.B., McLellan J.S. Respiratory syncytial virus entry and how to block it. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2019;17:233–245. doi: 10.1038/s41579-019-0149-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bawage S.S., Tiwari P.M., Pillai S., Dennis V., Singh S.R. Recent advances in diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of human respiratory syncytial virus. Adv. Virol. 2013;2013 doi: 10.1155/2013/595768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behera A.K., Matsuse H., Kumar M., Kong X., Lockey R.F., Mohapatra S.S. Blocking intercellular adhesion molecule-1 on human epithelial cells decreases respiratory syncytial virus infection. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2001;280:188–195. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.4093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bendelja K., Gagro A., Baće A., Lokar-Kolbas R., Kršulović-Hrešić V., Drazenović V., Mlinaric-Galinović G., Rabatić S. Predominant type-2 response in infants with respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) infection demonstrated by cytokine flow cytometry. Clin. Exper. Immunol. 2000;121:332–338. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2000.01297.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett B.L., Garofalo R.P., Cron S.G., Hosakote Y.M., Atmar R.L., Macias C.G., Piedra P.A. Immunopathogenesis of respiratory syncytial virus bronchiolitis. J. Infect. Dis. 2007;195:1532–1540. doi: 10.1086/515575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhuiyan M.U., Luby S.P., Alamgir N.I., Homaira N., Sturm–Ramirez K., Gurley E.S., Abedin J., Zaman R.U., Alamgir A.S., Rahman M. Costs of hospitalization with respiratory syncytial virus illness among children aged< 5 years and the financial impact on households in Bangladesh, 2010. J. Glob. Health. 2017;7 doi: 10.7189/jogh.07.010412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bont L., Checchia P.A., Fauroux B., Figueras-Aloy J., Manzoni P., Paes B., Simões E.A., Carbonell-Estrany X. Defining the epidemiology and burden of severe respiratory syncytial virus infection among infants and children in western countries. Infect. Dis. Ther. 2016;5:271–298. doi: 10.1007/s40121-016-0123-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bont L., Heijnen C.J., Kavelaars A., Van Aalderen W.M., Brus F., Draaisma J.M.T., Pekelharing-Berghuis M., van Diemen-Steenvoorde R.A., Kimpen J.L. Local interferon-γ levels during respiratory syncytial virus lower respiratory tract infection are associated with disease severity. J. Infect. Dis. 2001;184:355–358. doi: 10.1086/322035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borchers A.T., Chang C., Gershwin M.E., Gershwin L.J. Respiratory syncytial virus—a comprehensive review. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 2013;45:331–379. doi: 10.1007/s12016-013-8368-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley J.P., Bacharier L.B., Bonfiglio J., Schechtman K.B., Strunk R., Storch G., Castro M. Severity of respiratory syncytial virus bronchiolitis is affected by cigarette smoke exposure and atopy. Pediatrics. 2005;115:e7–e14. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-0059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandenburg A., Kleinjan A., van Het Land B., Moll H., Timmerman H., De Swart R., Neijens H., Fokkens W., Osterhaus A. Type 1-like immune response is found in children with respiratory syncytial virus infection regardless of clinical severity. J. Med. Virol. 2000;62:267–277. doi: 10.1002/1096-9071(200010)62:2<267::AID-JMV20>3.3.CO;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun M.R., Noton S.L., Blanchard E.L., Shareef A., Santangelo P.J., Johnson W.E., Fearns R. Respiratory syncytial virus M2-1 protein associates non-specifically with viral messenger RNA and with specific cellular messenger RNA transcripts. PLoS Pathog. 2021;17 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1009589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buck R., Cordle C., Thomas D., Winship T., Schaller J., Dugle J. Longitudinal study of intracellular T cell cytokine production in infants compared to adults. Clin. Exper. Immunol. 2002;128:490–497. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2002.01851.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao D., Gao Y., Roesler C., Rice S., D'Cunha P., Zhuang L., Slack J., Domke M., Antonova A., Romanelli S. Cryo-EM structure of the respiratory syncytial virus RNA polymerase. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:368. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-14246-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chanock R., Finberg L. Recovery from infants with respiratory illness of a virus related to chimpanzee coryza agent (CCA) II. Epidemiologie Aspect. Infec.n Infants Young Children. 1957 doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a119902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chanock R., Roizman B., Myers M., Ruth R. Recovery from infants with respiratory illness of a virus related to chimpanzee coryza agent (CCA) I. Isol., Proper. Characteriz. 1957 doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a119901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen K.-F., Blyn L., Rothman R.E., Ramachandran P., Valsamakis A., Ecker D., Sampath R., Gaydos C.A. Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction and electrospray ionization mass spectrometry for identifying acute viral upper respiratory tract infections. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2011;69:179–186. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2010.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M., Chang J., Nason M., Rangel D., Gall J., Graham B., Ledgerwood J. A flow cytometry-based assay to assess RSV-specific neutralizing antibody is reproducible, efficient and accurate. J. Immunol. Methods. 2010;362:180–184. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2010.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chida-Nagai A., Sato H., Sato I., Shiraishi M., Sasaki D., Izumi G., Yamazawa H., Cho K., Manabe A., Takeda A. Risk factors for hospitalisation due to respiratory syncytial virus infection in children receiving prophylactic palivizumab. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2022:1–9. doi: 10.1007/s00431-021-04216-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu C.Y., Urisman A., Greenhow T.L., Rouskin S., Yagi S., Schnurr D., Wright C., Drew W.L., Wang D., Weintrub P.S. Utility of DNA microarrays for detection of viruses in acute respiratory tract infections in children. J. Pediatr. 2008;153:76–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2007.12.035. e71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choudhary M.L., Anand S.P., Heydari M., Rane G., Potdar V.A., Chadha M.S., Mishra A.C. Development of a multiplex one step RT-PCR that detects eighteen respiratory viruses in clinical specimens and comparison with real time RT-PCR. J. Virol. Methods. 2013;189:15–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2012.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung H.L., Kim W.T., Kim J.K., Choi E.J., Lee J.H., Lee G.H., Kim S.G. Relationship between atopic status and nasal interleukin 10 and 11 levels in infants with respiratory syncytial virus bronchiolitis. Annal. Allergy, Asthma Immunol. 2005;94:267–272. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)61307-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins P., Chanock R., Murphy B., Knipe D., Howley P., Griffin D., Lamb R., Martin M., Roizman B., Straus S. In: Fields Virology. Fields BN, Knipe DM, editors. 1996. Respiratory syncytial virus. [Google Scholar]

- Collins P.L., Graham B.S. Viral and host factors in human respiratory syncytial virus pathogenesis. J. Virol. 2008;82:2040–2055. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01625-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Correa D., Giraldo D.M., Gallego S., Taborda N.A., Hernandez J.C. Immunity towards human respiratory syncytial virus. Acta Virol. 2023;67:11887. doi: 10.3389/av.2023.11887. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Culley F.J., Pollott J., Openshaw P.J. Age at first viral infection determines the pattern of T cell–mediated disease during reinfection in adulthood. J. Exp. Med. 2002;196:1381–1386. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Currier M.G., Lee S., Stobart C.C., Hotard A.L., Villenave R., Meng J., Pretto C.D., Shields M.D., Nguyen M.T., Todd S.O. EGFR interacts with the fusion protein of respiratory syncytial virus strain 2-20 and mediates infection and mucin expression. PLoS Pathog. 2016;12 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dakhama A., Park J.-W., Taube C., Joetham A., Balhorn A., Miyahara N., Takeda K., Gelfand E.W. The enhancement or prevention of airway hyperresponsiveness during reinfection with respiratory syncytial virus is critically dependent on the age at first infection and IL-13 production. J. Immunol. 2005;175:1876–1883. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.3.1876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davison A. ICTV: international committee on taxonomy of viruses. Virus Taxon. 2017 https://ictv.global/taxonomy Retrieved from. Accessed June 25, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- De R., Jiang M., Sun Y., Huang S., Zhu R., Guo Q., Zhou Y., Qu D., Cao L., Lu F. A scoring system to predict severe acute lower respiratory infection in children caused by respiratory syncytial virus. Microorganisms. 2024;12:1411. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms12071411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Riccio M., Spreeuwenberg P., Osei-Yeboah R., Johannesen C.K., Fernandez L.V., Teirlinck A.C., Wang X., Heikkinen T., Bangert M., Caini S. Burden of respiratory syncytial virus in the European Union: estimation of RSV-associated hospitalizations in children under 5 years. J. Infect. Dis. 2023;228:1528–1538. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiad188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falsey A.R., Hennessey P.A., Formica M.A., Cox C., Walsh E.E. Respiratory syncytial virus infection in elderly and high-risk adults. New Engl. J. Med. 2005;352:1749–1759. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FDA, 2023a. FDA approves first respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) vaccine. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-first-respiratory-syncytial-virus-rsv-vaccine (Accessed June 10, 2024).

- FDA, 2023b. FDA approves first vaccine for pregnant individuals to prevent RSV in infants. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-first-vaccine-pregnant-individuals-prevent-rsv-infants (Accessed June 10, 2024).

- Fearns R., Plemper R.K. Polymerases of paramyxoviruses and pneumoviruses. Virus Res. 2017;234:87–102. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2017.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman S.A., Hendry R.M., Beeler J.A. Identification of a linear heparin binding domain for human respiratory syncytial virus attachment glycoprotein G. J. Virol. 1999;73:6610–6617. doi: 10.1128/JVI.73.8.6610-6617.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng S., Zeng D., Zheng J., Zhao D. MicroRNAs: mediators and therapeutic targets to airway hyper reactivity after respiratory syncytial virus infection. Front. Microbiol. 2018;9:2177. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.02177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figueras-Aloy J., Manzoni P., Paes B., Simões E.A., Bont L., Checchia P.A., Fauroux B., Carbonell-Estrany X. Defining the risk and associated morbidity and mortality of severe respiratory syncytial virus infection among preterm infants without chronic lung disease or congenital heart disease. Infect. Dis. Ther. 2016;5:417–452. doi: 10.1007/s40121-016-0130-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fjaerli H.-O., Farstad T., Bratlid D. Hospitalisations for respiratory syncytial virus bronchiolitis in Akershus, Norway, 1993–2000: a population-based retrospective study. BMC Pediatr. 2004;4:1–7. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-4-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming-Dutra K.E. Use of the Pfizer respiratory syncytial virus vaccine during pregnancy for the prevention of respiratory syncytial virus–associated lower respiratory tract disease in infants: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices—United States, 2023. MMWR. Morb. Mortal. Weekly Report. 2023;72 doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7241e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonceca A., Flanagan B., Trinick R., Smyth R., McNamara P. Primary airway epithelial cultures from children are highly permissive to respiratory syncytial virus infection. Thorax. 2012;67:42–48. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2011-200131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freymuth F., Vabret A., Cuvillon-Nimal D., Simon S., Dina J., Legrand L., Gouarin S., Petitjean J., Eckart P., Brouard J. Comparison of multiplex PCR assays and conventional techniques for the diagnostic of respiratory virus infections in children admitted to hospital with an acute respiratory illness. J. Med. Virol. 2006;78:1498–1504. doi: 10.1002/jmv.20725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funchal G.A., Jaeger N., Czepielewski R.S., Machado M.S., Muraro S.P., Stein R.T., Bonorino C.B., Porto B.N. Respiratory syncytial virus fusion protein promotes TLR-4–dependent neutrophil extracellular trap formation by human neutrophils. PloS one. 2015;10 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0124082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garofalo R.P., Patti J., Hintz K.A., Hill V., Ogra P.L., Welliver R.C. Macrophage inflammatory protein-1α (not T helper type 2 cytokines) is associated with severe forms of respiratory syncytial virus bronchiolitis. J. Infect. Dis. 2001;184:393–399. doi: 10.1086/322788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilman M.S., Liu C., Fung A., Behera I., Jordan P., Rigaux P., Ysebaert N., Tcherniuk S., Sourimant J., Eléouët J.-F. Structure of the respiratory syncytial virus polymerase complex. Cell. 2019;179:193–204. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2019.08.014. e114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser L., Coulter P.J., Shields M., Touzelet O., Power U.F., Broadbent L. Airway epithelial derived cytokines and chemokines and their role in the immune response to respiratory syncytial virus infection. Pathogens. 2019;8:106. doi: 10.3390/pathogens8030106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González P.A., Prado C.E., Leiva E.D., Carreño L.J., Bueno S.M., Riedel C.A., Kalergis A.M. Respiratory syncytial virus impairs T cell activation by preventing synapse assembly with dendritic cells. Proc. National Acad. Sci. 2008;105:14999–15004. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802555105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goritzka M., Makris S., Kausar F., Durant L.R., Pereira C., Kumagai Y., Culley F.J., Mack M., Akira S., Johansson C. Alveolar macrophage–derived type I interferons orchestrate innate immunity to RSV through recruitment of antiviral monocytes. J. Experim. Med. 2015;212:699–714. doi: 10.1084/jem.20140825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths C., Drews S.J., Marchant D.J. Respiratory syncytial virus: infection, detection, and new options for prevention and treatment. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2017;30:277–319. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00010-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths C.D., Bilawchuk L.M., McDonough J.E., Jamieson K.C., Elawar F., Cen Y., Duan W., Lin C., Song H., Casanova J.-L. IGF1R is an entry receptor for respiratory syncytial virus. Nature. 2020;583:615–619. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2369-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gut W., Pancer K., Abramczuk E., Cześcik A., Dunal-Szczepaniak M., Lipka B., Litwińska B. RSV respiratory infection in children under 5 yo–dynamics of the immune response Th1/Th2 and IgE. Przegl Epidemiol. 2013;67:17–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habibi M.S., Thwaites R.S., Chang M., Jozwik A., Paras A., Kirsebom F., Varese A., Owen A., Cuthbertson L., James P. Neutrophilic inflammation in the respiratory mucosa predisposes to RSV infection. Science. 2020;370:eaba9301. doi: 10.1126/science.aba9301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halfhide C.P., Flanagan B.F., Brearey S.P., Hunt J.A., Fonceca A.M., McNamara P.S., Howarth D., Edwards S., Smyth R.L. Respiratory syncytial virus binds and undergoes transcription in neutrophils from the blood and airways of infants with severe bronchiolitis. J. Infect. Dis. 2011;204:451–458. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall C.B., Walsh E.E., Long C.E., Schnabel K.C. Immunity to and frequency of reinfection with respiratory syncytial virus. J. Infect. Dis. 1991;163:693–698. doi: 10.1093/infdis/163.4.693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harshbarger W., Tian S., Wahome N., Balsaraf A., Bhattacharya D., Jiang D., Pandey R., Tungare K., Friedrich K., Mehzabeen N. Convergent structural features of respiratory syncytial virus neutralizing antibodies and plasticity of the site V epitope on prefusion F. PLoS Pathog. 2020;16 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1008943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassan M.Z., Islam M.A., Haider S., Shirin T., Chowdhury F. Respiratory syncytial virus-associated deaths among children under five before and during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Bangladesh. Viruses. 2024;16:111. doi: 10.3390/v16010111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heidema J., Rossen J.W., Lukens M.V., Ketel M.S., Scheltens E., Kranendonk M.E., van Maren W.W., van Loon A.M., Otten H.G., Kimpen J.L. Dynamics of human respiratory virus-specific CD8+ T cell responses in blood and airways during episodes of common cold. J. Immunol. 2008;181:5551–5559. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.8.5551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ispas G., Koul A., Verbeeck J., Sheehan J., Sanders-Beer B., Roymans D., Andries K., Rouan M.-C., De Jonghe S., Bonfanti J.-F. Antiviral activity of TMC353121, a respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) fusion inhibitor, in a non-human primate model. PloS one. 2015;10 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0126959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jartti T., Lehtinen P., Vuorinen T., Ruuskanen O. Bronchiolitis: age and previous wheezing episodes are linked to viral etiology and atopic characteristics. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2009;28:311–317. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e31818ee0c1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jartti T., Söderlund-Venermo M., Hedman K., Ruuskanen O., Mäkelä M.J. New molecular virus detection methods and their clinical value in lower respiratory tract infections in children. Paediatr Respir Rev. 2013;14:38–45. doi: 10.1016/j.prrv.2012.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jayagopal A., Halfpenny K.C., Perez J.W., Wright D.W. Hairpin DNA-functionalized gold colloids for the imaging of mRNA in live cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:9789–9796. doi: 10.1021/ja102585v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi P., Shaw A., Kakakios A., Isaacs D. Interferon-gamma levels in nasopharyngeal secretions of infants with respiratory syncytial virus and other respiratory viral infections. Clin. Exper. Immunol. 2003;131:143–147. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2003.02039.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim C.K., Callaway Z., Koh Y.Y., Kim S.-H., Fujisawa T. Airway IFN-γ production during RSV bronchiolitis is associated with eosinophilic inflammation. Lung. 2012;190:183–188. doi: 10.1007/s00408-011-9349-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim T.H., Oh D.S., Jung H.E., Chang J., Lee H.K. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells contribute to the production of IFN-β via TLR7-MyD88-dependent pathway and CTL priming during respiratory syncytial virus infection. Viruses. 2019;11:730. doi: 10.3390/v11080730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kristjansson S., Bjarnarson S.P., Wennergren G., Palsdottir A.H., Arnadottir T., Haraldsson A., Jonsdottir I. Respiratory syncytial virus and other respiratory viruses during the first 3 months of life promote a local TH2-like response. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2005;116:805–811. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar H., Kawai T., Akira S. Pathogen recognition by the innate immune system. Int. Rev. Immunol. 2011;30:16–34. doi: 10.3109/08830185.2010.529976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurt-Jones E.A., Popova L., Kwinn L., Haynes L.M., Jones L.P., Tripp R.A., Walsh E.E., Freeman M.W., Golenbock D.T., Anderson L.J. Pattern recognition receptors TLR4 and CD14 mediate response to respiratory syncytial virus. Nat. Immunol. 2000;1:398–401. doi: 10.1038/80833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuypers J., Campbell A., Cent A., Corey L., Boeckh M. Comparison of conventional and molecular detection of respiratory viruses in hematopoietic cell transplant recipients. Transpl. Infect. Dis. 2009;11:298–303. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3062.2009.00400.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuypers J., Wright N., Ferrenberg J., Huang M.-L., Cent A., Corey L., Morrow R. Comparison of real-time PCR assays with fluorescent-antibody assays for diagnosis of respiratory virus infections in children. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2006;44:2382–2388. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00216-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuypers J., Wright N., Morrow R. Evaluation of quantitative and type-specific real-time RT-PCR assays for detection of respiratory syncytial virus in respiratory specimens from children. J. Clin. Virol.y. 2004;31:123–129. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2004.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachaud L., Fernández-Arévalo A., Normand A.-C., Lami P., Nabet C., Donnadieu J.L., Piarroux M., Djenad F., Cassagne C., Ravel C. Identification of Leishmania by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization–time of flight (MALDI-TOF) mass spectrometry using a free Web-based application and a dedicated mass-spectral library. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2017;55:2924–2933. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00845-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Law B.J., Langley J.M., Allen U., Paes B., Lee D.S., Mitchell I., Sampalis J., Walti H., Robinson J., O'Brien K. The Pediatric Investigators Collaborative Network on Infections in Canada study of predictors of hospitalization for respiratory syncytial virus infection for infants born at 33 through 35 completed weeks of gestation. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2004;23:806–814. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000137568.71589.bd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lay M.K., Bueno S.M., Gálvez N., Riedel C.A., Kalergis A.M. New insights on the viral and host factors contributing to the airway pathogenesis caused by the respiratory syncytial virus. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2016;42:800–812. doi: 10.3109/1040841X.2015.1055711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lay M.K., González P.A., León M.A., Céspedes P.F., Bueno S.M., Riedel C.A., Kalergis A.M. Advances in understanding respiratory syncytial virus infection in airway epithelial cells and consequential effects on the immune response. Microb. Infec. 2013;15:230–242. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2012.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legg J.P., Hussain I.R., Warner J.A., Johnston S.L., Warner J.O. Type 1 and type 2 cytokine imbalance in acute respiratory syncytial virus bronchiolitis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2003;168:633–639. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200210-1148OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine D.A., Platt S.L., Dayan P.S., Macias C.G., Zorc J.J., Krief W., Schor J., Bank D., Fefferman N., Shaw K.N. Risk of serious bacterial infection in young febrile infants with respiratory syncytial virus infections. Pediatrics. 2004;113:1728–1734. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.6.1728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Johnson E.K., Shi T., Campbell H., Chaves S.S., Commaille-Chapus C., Dighero I., James S.L., Mahé C., Ooi Y. National burden estimates of hospitalisations for acute lower respiratory infections due to respiratory syncytial virus in young children in 2019 among 58 countries: a modelling study. Lancet Respir. Med. 2021;9:175–185. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30322-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Wang X., Blau D.M., Caballero M.T., Feikin D.R., Gill C.J., Madhi S.A., Omer S.B., Simões E.A., Campbell H. Global, regional, and national disease burden estimates of acute lower respiratory infections due to respiratory syncytial virus in children younger than 5 years in 2019: a systematic analysis. The Lancet. 2022;399:2047–2064. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00478-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liegl B., Kepten I., Le C., Zhu M., Demetri G., Heinrich M., Fletcher C., Corless C., Fletcher J. Heterogeneity of kinase inhibitor resistance mechanisms in GIST. J. Pathol. 2008;216:64–74. doi: 10.1002/path.2382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindell D.M., Morris S., Mukherjee S., Lukacs N.W. TLR-7 Mediated Responses to Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV)(133.45) J. Immunol. 2009;182:133.145. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.182.Supp.133.45. -133.145. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lukacs N.W., Moore M.L., Rudd B.D., Berlin A.A., Collins R.D., Olson S.J., Ho S.B., Peebles R.S., Jr Differential immune responses and pulmonary pathophysiology are induced by two different strains of respiratory syncytial virus. Am. J. Pathol. 2006;169:977–986. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.051055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukacs N.W., Smit J.J., Mukherjee S., Morris S.B., Nunez G., Lindell D.M. Respiratory virus-induced TLR7 activation controls IL-17–associated increased mucus via IL-23 regulation. J. Immunol. 2010;185:2231–2239. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahony J., Chong S., Bulir D., Ruyter A., Mwawasi K., Waltho D. Development of a sensitive loop-mediated isothermal amplification assay that provides specimen-to-result diagnosis of respiratory syncytial virus infection in 30 min. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2013;51:2696–2701. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00662-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marzec J., Cho H.-Y., High M., McCaw Z.R., Polack F., Kleeberger S.R. Toll-like receptor 4-mediated respiratory syncytial virus disease and lung transcriptomics in differentially susceptible inbred mouse strains. Physiol. Genomics. 2019;51:630–643. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00101.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazur N.I., Higgins D., Nunes M.C., Melero J.A., Langedijk A.C., Horsley N., Buchholz U.J., Openshaw P.J., McLellan J.S., Englund J.A. The respiratory syncytial virus vaccine landscape: lessons from the graveyard and promising candidates. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2018;18:e295–e311. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(18)30292-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazur N.I., Terstappen J., Baral R., Bardají A., Beutels P., Buchholz U.J., Cohen C., Crowe J.E., Cutland C.L., Eckert L. Respiratory syncytial virus prevention within reach: the vaccine and monoclonal antibody landscape. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2023;23:e2–e21. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(22)00291-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLellan J.S., Ray W.C., Peeples M.E. Structure and function of respiratory syncytial virus surface glycoproteins. Challeng. Opportun. Respir. Syncyt. Virus Vaccines. 2013:83–104. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-38919-1_4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLellan J.S., Yang Y., Graham B.S., Kwong P.D. Structure of respiratory syncytial virus fusion glycoprotein in the postfusion conformation reveals preservation of neutralizing epitopes. J. Virol. 2011;85:7788–7796. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00555-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meissner H.C. Viral bronchiolitis in children. New Engl. J. Med. 2016;374:62–72. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1413456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller A.L., Bowlin T.L., Lukacs N.W. Respiratory syncytial virus-induced chemokine production: linking viral replication to chemokine production in vitro and in vivo. J. Infect. Dis. 2004;189:1419–1430. doi: 10.1086/382958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mobbs K.J., Smyth R.L., O'Hea U., Ashby D., Ritson P., Hart C.A. Cytokines in severe respiratory syncytial virus bronchiolitis. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2002;33:449–452. doi: 10.1002/ppul.10101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mochizuki H., Todokoro M., Arakawa H. RS virus-induced inflammation and the intracellular glutathione redox state in cultured human airway epithelial cells. Inflammation. 2009;32:252–264. doi: 10.1007/s10753-009-9128-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]