Abstract

SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern (VOC) have been associated with increased viral transmission and disease severity. We investigated the mechanisms of pathogenesis caused by variants using a host blood transcriptome profiling approach. We analysed transcriptional signatures of COVID-19 patients comparing those infected with wildtype (wt), alpha, delta or omicron strains seeking insights into infection in Asymptomatic cases.

Comparison of transcriptional profiles of Symptomatic and Asymptomatic COVID-19 cases showed increased differentially regulated gene (DEGs) of inflammatory, apoptosis and blood coagulation pathways, with decreased T cell and Interferon stimulated genes (ISG) activation. Between SARS-CoV-2 strains, an increasing number of DEGs occurred in comparisons between wt and alpha (196), delta (1425) or, omicron (2313) infections. COVID-19 cases with alpha or, delta variants demonstrated suppression transcripts of innate immune pathways. EGR1 and CXCL8 were highly upregulated in those infected with VOC; heme biosynthetic pathway genes (ALAS2, HBB, HBG1, HBD9) and ISGs were downregulated. Delta and omicron infections upregulated ribosomal pathways, reflecting increased viral RNA translation. Asymptomatic COVID-19 cases infected with delta infections showed increased cytokines and ISGs expression. Overall, increased inflammation, with reduced host heme synthesis was associated with infections caused by VOC infections, with raised type I interferon in cases with less severe disease.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-024-76401-1.

Keywords: SARS-CoV-2, Variants of concern, EGR1, ALAS2, ISG, Delta variant

Subject terms: Infectious diseases, Pathogenesis, Computational biology and bioinformatics, Gene ontology, Genome informatics

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic recorded 6.8 million deaths up to 10 March 20231. Infections caused by SARS-CoV-2 ranged in severity from asymptomatic to mild, moderate, severe to critical disease2. COVID-19 surges were caused by evolving SARS-CoV-2 strains, Wuhan and S clades evolved in 2020 to G clade strains characterized by D614G which were more transmissible and led to variants of concern (VOC)3. VOC were defined primarily based on mutations in the Spike glycoprotein responsible for binding to host receptors to drive viral entry into cells4,5. Alpha variants were first identified at the end of 2020, followed by beta, gamma, and then delta variants in 20216,7. Omicron and its sub-variants first emerged at the end of 2021. Epidemiological data show that alpha variants caused a surge in disease severity as did beta and gamma variants8–10.

Vulnerability of the host to new SARS-CoV-2 emerging strains was associated with their ability to escape host neutralizing antibodies8. Cellular immunity against SARS-CoV-2 was also shown to play an essential role in protection against the virus11. The severity of pandemic waves associated with particular VOCs varied across global populations, with disease severity attributed to specific characteristics of the population such as, age, density, access to health and vaccinations1. In Pakistan, about 30,000 COVID-19 related deaths were documented. Hospital-based studies have shown increased COVID-19 disease severity to be associated with delta variants12. Relatively low COVID-19 morbidity observed in Pakistan has been associated with higher antibody seroprevalence and pre-pandemic immunity in the population13.

Pathways associated with unfavourable COVID-19 outcomes have been identified through transcriptomic profiling of blood samples from individuals with COVID-19. Genes associated with neutrophil activation, inflammatory responses, and cytokine production were highly upregulated in symptomatic and critically ill patients14. The role of T cell exhaustion in severe COVID-19 is observed15. SARS-CoV-2 can alter hematological parameters resulting in lymphopenia, thrombocytopenia, coagulation disorders and stress erythropoiesis16. Earlier reports revealed the importance of Type I interferon (IFN) responses in protection against severe COVID-1917. Further, IFN-related gene signatures such as, IFI27 are proposed to be predictive of COVID-19 outcomes18. A study involving rhesus macaques showed that VOCs induced greater upregulation of RNAs involved in gene expression and metabolic pathways as compared with wildtype strains19, whilst, another found that whilst differing transcriptional signatures were evident in tissues this was not the case in blood20. There is limited information regarding VOC-induced pathogenesis through the study of COVID-19 patients.

Local data can help understand the observed epidemiological impact of COVID-19 severity in the context of the waves experienced in the population. We studied blood transcriptional profiles of COVID-19 patients recruited between June 2020 and May 2022, a period when Pakistan suffered 5 pandemic surges associated with wild-type, then alpha followed by beta/gamma, delta and omicron waves6,7. We investigated gene expression in individuals infected with wildtype and other variants including, VOCs alpha, delta and omicron. Our data reveals insights into variability of type I IFN-responses, hemapoietic pathways and humoral immunity in infections caused by wildtype or VOC infected COVID-19 cases.

Results

Description of study subjects

COVID-19 patients with Asymptomatic or Symptomatic disease were recruited and their disease severity assessed based on the WHO ordinal scoring (Table 1, S Table 1)21. We included patients for whom respiratory samples had been available and therefore SARS-CoV-2 variant identification had been performed in respiratory samples collected at the time of their first COVID-19 diagnostic PCR6,22. All cases were recruited to the study within 72 h of their positive SARS-CoV-2 diagnostic test and they had no known history of COVID-19 infection. The workflow and design of the study is illustrated in Fig. 1. Transcriptional profiles were determined based on RNA arrays run on blood samples of study subjects. DEGs identified were further investigated using GO and KEGG pathways-based analyses.

Table 1.

Description of study population.

| Variables | COVID-19 | Symptomatic | Asymptomatic | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 51 | N = 19 | N = 32 | ||

| Gender N(%) | ||||

| Male | 35 (69%) | 13 (60%) | 23 (72%) | NS, 0.059 |

| Female | 16 (31%) | 6 (40%) | 09 (28%) | |

| Age group in years N(%) | ||||

| 18–25 | 7 (14%) | 3 (16%) | 4 (12%) | 0.004* |

| 26–45 | 19 (37%) | 3 (16%) | 16 (50%) | |

| > 45 | 25 (49%) | 13 (68%) | 12 (38%) | |

| Median ± IQR | 45.5(55 − 33) | 53(31 − 24) | 39(48 − 30) | |

| Co-morbids (N, %) | ||||

| Diabetes | 3 (5.8%) | 3 (16%) | 1(3%) | |

| Hypertension | 3 (5.8%) | 3 (16%) | 1(3%) | |

| WHO ordinal Score (0–10) | ||||

| Ordinal Score 1–2 | 30 | 1 | 29 | |

| Ordinal Score 3–4 | 6 | 5 | 1 | |

| Ordinal Score 5–6 | 7 | 5 | 2 | |

| Ordinal Scale 7–8 | 3 | 3 | N/A | |

| Ordinal Score 9–10 | 5 | 5 | N/A | |

| D-dimer (mg/L) | 3.6 ± 4 | N/A | ||

| CRP (mg/L)a | 103.7 ± 79 | 2.6 ± 4.2 | 0.0041* | |

| LDH (I.U/L)*,a | 635.4 ± 919 | N/A | ||

| Ferritin (ng/ml)*,a | 793.4 ± 634 | 908.3 ± 735.7 | NS, 0.792 | |

| Poct-GLUF (mg/dl)*,a | 157.5 ± 82 | 119 ± 24.1 | ||

| NLR (Ratio)*,a | 8.2 ± 7 | 4.2

|

NS, 0.350 | |

| VoC N(%) | ||||

| Wild type | 28 (55%) | 11 (57.8%) | 17 (53.12%) | |

| Alpha | 4 (7.9%) | 1 (5.2%) | 3 (9.4%) | |

| Delta | 12 (23.5%) | 3 (15.8%) | 9 (28.12%) | |

| Omicron | 3 (5.8%) | 1 (5.3%) | 2 (6.3%) | |

| Others | 4 (7.8%) | 3 (15.8%) | 1 (3.12%) | |

| Vaccination status | ||||

| Fully vaccinated | 10 (20%) | 1 (5%) | 9 (28%) | |

| Un vaccinated | 41 (80%) | 18 (95%) | 23 (72%) | |

C- reactive protein (CRP), lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), point of care test for glucose fasting (Poct-GLUF), neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio (NLR). p value as compared across age groups between Asymptomatic and Symptomatic COVID-19 cases. ‘ ‘others’ were; 19A and Kappa variants. a’, Symptomatic cases (n = 18), Asymptomatic (n = 3). VOC. The Mann Whitney-U test was used to compare values between groups, ‘*’, p < 0.05 was significantly different; NS, not statistically significant.

Fig. 1.

Description of work flow for analysis of blood RNA transcriptional profiles in COVID-19 cases. Samples were categorized based on COVID-19 cases with Symptomatic or Asymptomatic infections. They were identified by their infecting SARS-CoV-2 variant as wildtype, or Variants of Concern (VOC). Whole blood was processed for RNA microarray analysis using the Affymetrix system and differentially regulated genes identified (DEGs) identified. These were analysed by bioinformatics analysis using KEGG GO, Reactome and WikiPathways.

Of the 51 COVID-19 cases studied, the majority (80%) of cases were recruited prior to the introduction of COVID-19 vaccinations (Table 1). 31% of individuals were females. Nineteen individuals had Symptomatic whilst 32 had Asymptomatic COVID-19 at the time of PCR diagnosis. The median age of Symptomatic COVID-19 cases (53 years) was higher than those with Asymptomatic disease (39 years, p = 0.004, MWU test). 16% of those with Symptomatic COVID-19 as compared with 3% of Asymptomatic cases had history of diabetes and hypertension. C- Reactive Protein (CRP) levels were raised in those with Symptomatic disease (p = 0.004). The neutrophil lymphocyte ratio (NLR) showed a higher trend in Symptomatic patients but these data did not differ significantly likely due to the limited number of Asymptomatic cases for whom the laboratory parameters were available. SARS-CoV-2 genome sequencing of respiratory samples showed that (n = 28, 55%) patients were infected with wildtype (wt)s SARS-CoV-2. Nineteen patients were infected with VOC; four were infected with alpha, 12 with delta and three with omicron variants (other variants were 19 A and 21D). In two samples, variants could not be determined due to low viral RNA present.

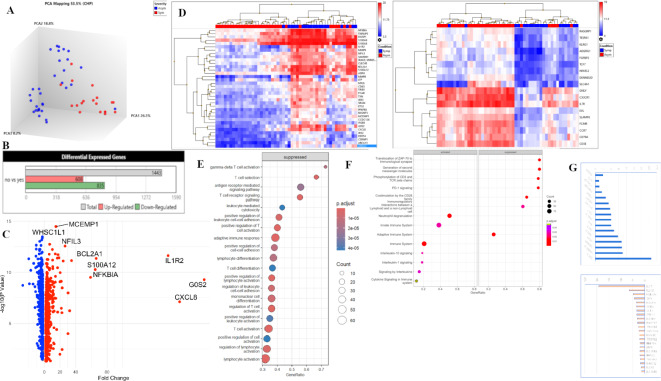

Differential gene expression between individuals with symptomatic versus asymptomatic COVID-19

To understand host gene expression profiles associated with disease susceptibility we first compared transcriptional profiles, identifying DEGs between cases with Symptomatic (n = 19) and Asymptomatic (n = 32) COVID-19. Unhierarchical Principal Component Analysis (PCA) of transcriptional signals from the 51 COVID-19 patients showed a separation of Symptomatic COVID-19 (blue) clustered in PC1 indicating that expression profiles can differentiate health and disease in COVID-19 (Fig. 2A). Interestingly, cases with Asymptomatic infections showed equal distribution in PC2 and PC3. A total of 1443 DEGs were identified of which 608 genes were upregulated and 835 downregulated DEGs (Fig. 2B). To identify genes most differentially regulated between Symptomatic and Asymptomatic COVID-19, a volcano plot was generated (Fig. 2C) depicting genes which showed > 2-logFC change with p value < 0.05. This analysis identified the neutrophil activating chemokine CXCL8 and the IL1R2 cytokine gene the most differentially increased. In addition, there was upregulation of other gene associated with inflammatory (NFKB1A, TNFAIP3, MMP8, LTF, NFIL3, MCMEMP1), apoptotic (BCL2A1 and ANXA3) and blood coagulation (TFPI) respectively, in Symptomatic cases. Notably, there was downregulation of TCF7, a transcription factor that plays an important role in T cell development23. A heat map was generated which identified the top 30 up-DEGs (Fig. 2D) in the unclustered hierarchical map. This analysis identified differential profiles of inflammatory genes belonging to the innate cellular network involved in host defense at the initial stages of viral infection. Meanwhile, the down-DEGs related to lymphocyte activation and signaling (such as, CD3E, CD79A, CCR7, IL7R, CXCR1) as well as TCF7 involved in immune activation of T cell subsets that play an important role in controlling disease progression in the case of viral escape in the earlier phase of infection.

Fig. 2.

Comparison of transcriptional expression between those with Symptomatic and Asymptomatic COVID-19. (A) Principal component analysis to visualize the clustering of datasets into Symptomatic, n = 19 (Symp = red), Asymptomatic, n = 32 (Asymp = blue) groups. (B) Barplots depict the 2051 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between Symptomatic and Asymptomatic COVID-19 cases as Up-regulated, or Down-regulated and Total genes. (C) Volcano plot of DEGs between Symptomatic versus Asymptomatic COVID-19 cases. The log2 (FC) (fold change) is plotted on the x-axis, and the negative log10 p-value is plotted on the y-axis. The red points on the plot show Upregulated expression, Downregulated genes are shown in blue. Analysis with the absolute value of log2 (FC) not less than 1 (FC = 2) and p values less than 0.05. (C) The upper panel shows the 36 top-most Up-DEGs and the lower panel shows 18 Down-DEGs identified in the volcano plot. (D) Unhierarchical clustered heat-map of DEGs. (E) Dotplot of GO Analysis on biological pathways applied on Symptomatic vs. Asymptomatic COVID-19, with pathways on y-axis and gene ratio on the x-axis. (F) GSE Reactome pathway analysis applied on data. Pathways displayed on the y-axis and gene ratio on x-axis. The greater the size of circle the greater the number of genes involved in a pathway the circles are colored based on p-adjusted value. (G) A histogram of DEGs compared between Symptomatic and Asymptomatic COVID-19 cases focusing on inflammatory genes and ISGs (Table 2). The upper panel shows up-DEGs (blue) with gene IDs on the horizontal axis and fold change (log2) on the y axis. The lower panel shows down-DEGs (pink) with y axis units are fold decrease. Genes selected had < 2 > fold change with p value < 0.05 between comparative groups. (H) mRNA expression was evaluated using RT-PCR for COVID-19 cases. HuPO was used as the housekeeping gene to normalize the expression of the target genes: MAVS, OAS1, IFNa, IF144, HBB and ALAS2. Relative expression levels were quantified using the 2–∆∆CT method. The Mann-Whitney tests were performed to determine significant difference (p ≤ 0.05) between gene expression between the asymptomatic group (n = 22) and the symptomatic group (n = 4).

We next conducted GO enrichment analysis of biological pathways which revealed that in those with Symptomatic COVID-19, pathways related to the antimicrobial humoral response, inflammatory response and others related cellular responses to cytokines and signal transduction were upregulated. Whilst genes related to T cell selection, activation and signaling were suppressed (Fig. 2E). This is further emphasized through the GSE reactome pathway analysis (Fig. 2F) which showed immune activation of IL-1 and IL-10 responses in addition to other cytokines identified through GSE analysis of KEGG molecular pathways.

We further focused on Interferon-driven responses which play a fundamental role in determining disease outcomes in COVID-19. We investigated the presence of 96 selected genes including interferon stimulated genes (ISG), cytokine, chemokine and inflammatory pathway genes (S Table 2). By comparison of DEGs between Symptomatic and Asymptomatic COVID-19 cases we observed that in Symptomatic cases there was an upregulation of 16 genes (e.g. IL1, IL4, IL18, AREG, SOCS3, VEGFA) with downregulation of 22 genes (e.g. IL12, IL2, IFNAR2, TGF, MAVS, IRF4) compared with Asymptomatic cases (Fig. 2G).

Differential gene expression of selected genes was validated through RT-PCR studies using a sub-set of RNA samples available from Symptomatic (n = 4) and Asymptomatic (n = 19) cases, Fig. 2H. mRNA levels of MAVS were higher in Asymptomatic patients (p = 0.009) whilst levels of OAS1, IFN-a and IFI44 did not significantly differ between COVID-19 groups. Expression of ALAS2 was reduced in Symptomatic patients (p = 0.02) whilst, HBB showed a lower trend but was not different. These data fit with the DEGs pattern observed in the microarray analysis (S Table 3; MAVS p = 0.0007; OAS1 p = 0.08; IFN-a p = 0.57; IFI44 p = 0.48; HBB p = 0.26; ALAS2 p = 0.059).

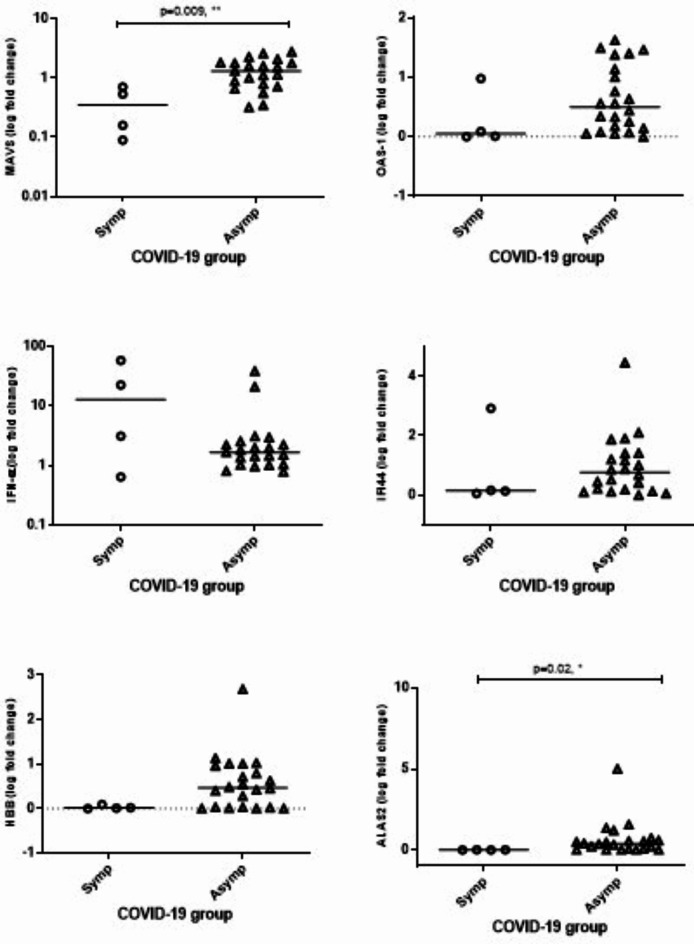

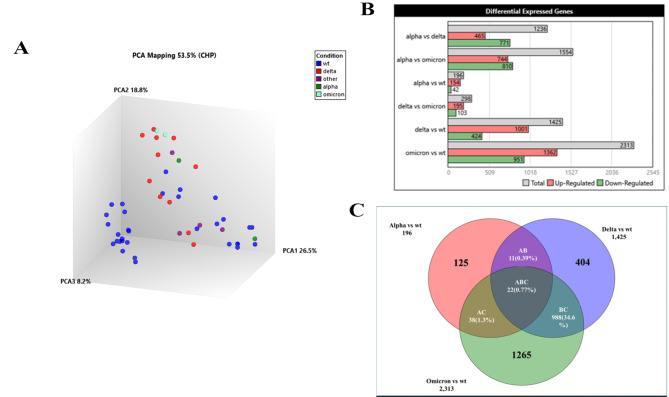

Investigating the effect of different SARS-CoV-2 variants on the modification host transcriptional responses during COVID-19

To compare how infections with SARS-CoV-2 wt compared with VOC comprising, alpha, delta and omicron strains. We studied the transcriptional profiles of 47 COVID-19 cases. First, a PCA analysis was used to view transcriptional signatures from wt (n = 28) and VOC (n = 19) infections (Fig. 3A). PCA analysis revealed clustering of individuals infected with delta and omicron, which were in a more distant compartment from profiles of those infected with wildtype and alpha variants. In total, we observed 3934 DEGs between COVID-19 cases infected with different SARS-CoV-2 variants and the analysis revealed an increasing number of DEGs with each emerging VOC; 196 DEGs between alpha and wildtype, 1425 DEGs between delta and wildtype whilst there were 2313 DEGs between omicron and wt individuals. Up DEGs were 78.6% in the case of alpha, 70.2% in the case of delta and 58.9% in the case of omicron comparisons with wt, respectively.

Fig. 3.

Differential transcriptional expression between those infected with VOC or wildtype SARS-CoV-2. (A) Clustering of DEGs using PCA analysis of transcriptional profiles of COVID-19 cases infected with wildtype (blue, wt, n = 32), or VOC comprising; alpha (green, n = 2), delta (red, n = 11), omicron (teal, n = 2) or other (n = 4, purple) variants. (B) Venn diagram depicts overlaps between DEGs between individuals infected with wt, alpha (n = 196), delta (n = 1475) or omicron (n = 2313) strains. The numbers in the non-overlapping segments indicate unique DEGs in each comparison. (C) Comparison of ISGs genes between COVID-19 cases infected with alpha, delta and omicron variants compared with wildtype (wt), respectively. ISGs between Symptomatic (Symp) and Asymptomatic (Asymp) cases are also displayed. The red color shows the higher fold change and the lower foldchange is shown by blue color.

A Venn diagram depicts the pattern of overlapping DEGs between COVID-19 VOC and wildtype infections. Only 22 genes were common DEGs between the three VOC vs. wildtype comparisons (Fig. 3B). The numbers in the non-overlapping segments indicate unique DEGs in each comparison. Despite limitations in the number of alpha and omicron, as well as non-stratification by disease category due to the small numbers in the two COVID-19 severity groups, our data suggests that the VOCs induced differential responses in the host, and we explored this further by separately comparing their gene expression against wt COVID-19 infections.

Dendrogram heatmap of ISGs in the context of disease severity and infection with SARS-CoV-2 variants

Activation of type I interferon responses is associated with anti-viral immunity with increased levels associated with improved COVID-19 outcomes We compared the expression patterns of a gene signature of 47 ISGs within the DEGs identified between Symptomatic and Asymptomatic COVID-19 as well as the comparison of DEGs between alpha, delta and omicron infections, respectively. The comparative gene expression of the 47 ISGs is represented in a heatmap dendrogram (Fig. 3C). ISGs were most highly upregulated in those infected with delta, followed by omicron, alpha and then in those with Symptomatic disease. The highest fold change was observed in IF144L and IF144 in delta infected individuals, and for IRAK3 in those with Symptomatic as compared with Asymptomatic COVID-19. The lowest foldchange of the ISGs was observed for DDX5 expression in omicron infected COVID-19 cases.

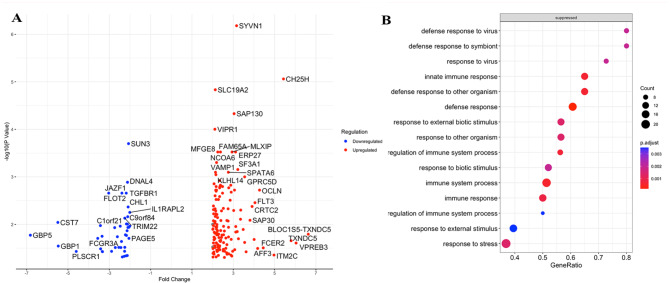

Alpha variants upregulate pro-inflammatory responses but downregulate protective responses as compared with wild-type SARS-CoV-2 strains

To further investigate the 196 DEGs identified in COVID-19 patients infected with alpha (n = 4) and wt cases (n = 28), we used a volcano plot analysis. Of the 151 Up-genes, highly upregulated DEGs included SYVN1, CH25H, SAP130, VIPR1, ITM2C, TXNDC5, VPREB3, AFF3 and ITM2C, these genes may play roles in various cellular processes, including immune response, antiviral defense, and inflammation (S Table 4). SYVN1 (regulates the signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3)/vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) axis) and CH25H (inflammatory factor present in macrophage populations)24 both are important inflammatory genes (Fig. 4A). Of the 42 Down-genes; CST7 (Cystatin F encoded by CST7 is a cysteine peptidase inhibitor known to be expressed in natural killer (NK) and CD8(+) T cells during steady-state conditions). GBP5 and GBP1 (guanylate binding proteins) are involved in intracellular pathogen defense mechanisms. PLSCR1 (phospholipid scramblase 1) plays roles in membrane dynamics and apoptosis. TRIM22 is an antiviral protein with roles in innate immune responses. FCGR3A (Fc-gamma receptor 3 A) is involved in immune cell activation and antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity. GSE analysis of biological pathways revealed that a number of innate immune and defense response related processes were suppressed in those infected with alpha variants (defense to viruses, cytokine signaling). Interestingly, no biological pathway genes were enriched in this comparison (Fig. 4B). A gene net plot of Wiki Enriched pathways further revealed that genes affected were associated with immune and inflammatory pathways with SARS-CoV-2 related signaling, apoptosis and type II interferon signaling (Fig. 4C).

Fig. 4.

Comparison of transcriptional profiles and biological pathways in COVID-19 cases infected with alpha versus wild-type SARS-CoV-2 strains. (A) A volcano plot showing fold change in 196 DEGs between the analysis of patients infected with alpha (n = 2) versus wt (n = 32) SARS-CoV-2. The log2 (FC) (fold change) is plotted on the x-axis, and the negative log10 p-value is plotted on the y-axis. The red dot depicts up-regulated genes and blue represents downregulated genes. Highly Up- and Down- regulated genes are labelled. (B) GSE applied on GO specifically on Biological pathways on 1475 DEGs. (C) GSE dot plot analysis applied to DEGs. Or 5D. GSEA showed GO terms related to COVID-19 disease. Pathways details are displayed on the y-axis and gene ratio is plotted on x-axis. The greater the size of circle the greater the number of genes involved in a pathway; the circles are colored based on p-adjusted value.

Analysis with the absolute value of log2 (FC) not less than 1 (FC = 2) and p values less than 0.05.

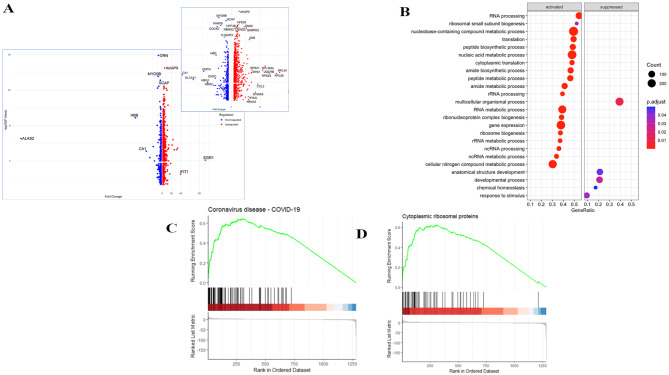

Delta variants upregulate inflammatory and ISGs as well as viral translation as compared with wild-type SARS-CoV-2 strains

We investigated the 1425 DEGs identified between delta (n = 12) as compared with wt (n = 28) infections. Of the 1041 Up-genes, a Volcano plot analysis revealed EGR1 (> 100 FC) to be the most Up-regulated DEG followed by IFIT (> 40 FC), S Table 5. Of the 425 Down-genes ALAS2, which catalyzes heme biosynthetic pathway (<-200 FC) to be most down-regulated DEG (Fig. 5A). A volcano plot excluding these three genes further reveals key up-DEGs as inflammatory genes (IFIT1, CCL2) and ribosomal pathway genes (RPL26, RPS24, RPL34, CCL2, RPS7, RPS21 and RPL36L and UQCRB). On the other hand, down-DEGs were CA1, MYO9B, GRN as well as erythrocyte synthesis related genes; HBB, DMTN, SCL4A1, HBD9 and GYPC. GSE analysis of GO Biological pathways revealed that the greatest number of upregulated genes were those related to cytoplasmic ribosomal proteins. Activated pathways included, VEGFA-VEGFR2 signaling, the network map of SARS-CoV-2 signaling, oxidative phosphorylation as well as nucleic acid metabolic processes (Fig. 5B). GSE dot plot analysis (Fig. 5C) which identified that all pathways were activated except for that related to multicellular organismal process, which was suppressed. Activated WikiPathways were related to RNA processing, ribosomal biogenesis, translation, peptide biosynthesis, and amide metabolic processes. These data indicate RNA, translation and ribosomal processes are activated greater in delta infected individuals, likely reflecting increased viral replication in the host. GSEA analysis of GO pathways further elaborated the enrichment score of genes involved in particular processes; with a positive regulation observed in the coronavirus disease COVID-19 pathway (Fig. 5D) as well as the GSE seen for cytoplasmic ribosomal proteins (Fig. 5E) when individuals infected with delta and SARS-CoV-2 wildtype variants were compared.

Fig. 5.

Comparison of transcriptional profiles and biological pathways in COVID-19 cases infected with delta versus wild-type SARS-CoV-2 strains. (A) A volcano plot showing fold change in 1475 DEGs between the analysis of patients infected with delta (n = 11) versus wt (n = 32) SARS-CoV-2. The log2 (FC) (fold change) is plotted on the x-axis, and the negative log10 p-value is plotted on the y-axis. The red dot depicts up-regulated genes and blue represents downregulated genes. EGR1 was most up-regulated and ALAS2 was most down-regulated. The inset shows the volcano plot without EGR1 and IFIT1. Highly Up- and Down- regulated genes are labelled. (B) GSE applied on GO specifically on Biological pathways on DEGs. (C) GSE WikiPathway analysis applied to DEGs. GSEA showed GO terms related to COVID-19 disease. Pathways details are displayed on the y-axis and gene ratio is plotted on x-axis. The greater the size of circle the greater the number of genes involved in a pathway; the circles are colored based on p-adjusted value. Figures show the enrichment score of D, KEGG pathways that shows Positive regulation of Coronavirus disease pathways and E, WikiPathway analysis shows Positive regulation of genes involved in ribosomal protein synthesis.

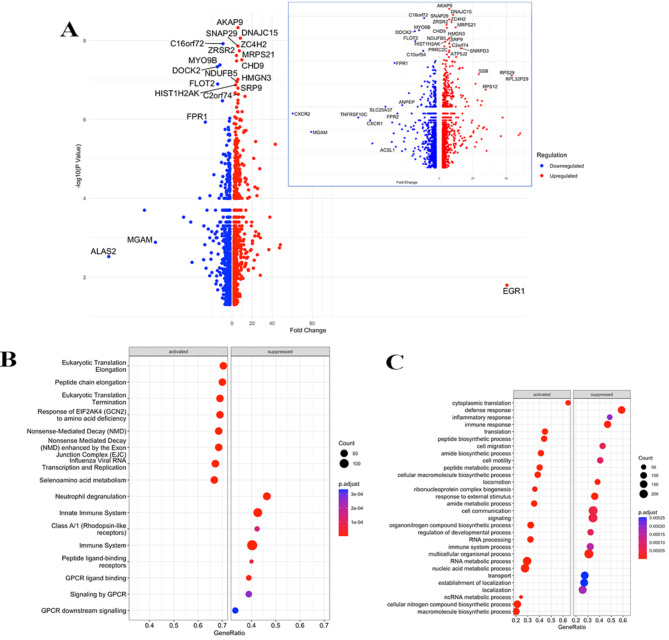

Omicron variants induced upregulation of viral mRNA translation and downregulation of immune responses as compared with wild-type SARS-CoV-2 strains

Investigation of the 2313 DEGs observed between transcriptional profiles of individuals infected with omicron (n = 3) as compared with wt (n = 28) strains. A volcano plot analysis revealed EGR1 as the most Up-regulated of 1362 DEGs whilst, ALAS2 was most Down-regulated of 951 DEGs (Fig. 6A, S Table 6). Additional upregulated genes were, DNAJC15, AC4H2, MRPS21, CHD9, HMGN3 and SRP9, which suggests activation of various cellular processes, including protein folding, lipid metabolism, mitochondrial function, chromatin remodeling, and protein targeting. Of note, MGAM, a marker of innate immunity was highly down-regulated. Some of the down regulated genes were chemokine receptors (CXCR1 and CXCR2) and other inflammation related genes are TNFRSF10C, ACSL1, FPR2, SLC25A37 and ANPEP. A GSE Reactome and biological pathway analysis of the DEGs further revealed that in those infected with omicron, viral mRNA translation, cytoplasmic ribosomal pathways, gene expression, nucleic acid metabolic processes and RNA processing pathways were all activated (Fig. 6B-C). In contrast, genes involved in inflammatory and immune responses such as, chemokine signaling and viral protein interaction with cytokines were suppressed.

Fig. 6.

Comparison of transcriptional profiles of COVID-19 cases infected with omicron versus wild-type SARS-CoV-2 strains. (A) A volcano plot of 2313 DEGs found between transcriptional profiles of cases infected with omicron (n = 2) versus wildtypes (n = 32). The x-axis is labelled with Fold change and y-axis shows –log10(p-value), the red dot depicts up-regulated genes and blue represents downregulated genes. The inset shows the volcano plot without the ALAS2 gene. (B) GSE function applied on DEGs using the Reactome pathway. (C) GSE of biological pathways. Pathways details are displayed on the y-axis and gene ratio is plotted on x-axis. The greater the size of circle the greater the number of genes involved in a pathway; the circles are colored based on p-adjusted value.

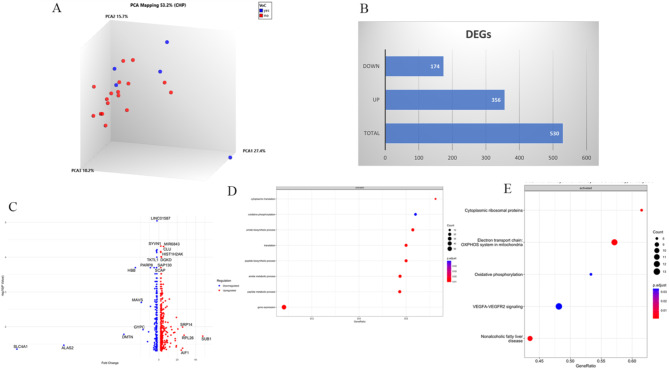

Investigating VOC induced transcription in the asymptomatic host

Thus far, our study of SARS-CoV-2 VOC infections showed enhanced inflammation, innate immune pathways including ISG and cytokines, with increased dysregulation of adaptive immune function. We wanted to understand how VOC may affect individuals who are able to control disease well. We therefore focused next only on studying transcriptome profiles of individuals who suffered Asymptomatic COVID-19, comprising 18 individuals infected with wt and nine cases infected with VOC (alpha, n = 4 or delta, n = 5). Of note, we excluded any vaccinated individuals in for this analysis. A PCA analysis revealed that profiles of three of the VOC cases were separated from wildtype, but two were clustered with the latter (Fig. 7A). There were 530 DEGs, with 356 Up and 174 Down DEGs between VOC and wildtype SARS-CoV-2 infections (Fig. 7B). A volcano plot analysis of the DEGs showed upregulation of AIF1, RPL26, SUB1 and SRP14. ALAS2 and SLC4A1 were highly down-regulated, as well as DMTN, GYPC, HBB, MAVS and PARP8 (Fig. 7C). GSE of biological processes identified the upregulation of cytoplasmic translation, oxidative phosphorylation and nucleotide metabolism in those infected with VOC (Fig. 7D). WikiPathway analysis of the DEGs further showed activation of ribosomal pathways, inflammatory VEGFA signaling and oxidative phosphorylation (Fig. 7E). Notably, no suppressed pathways were evident here.

Fig. 7.

Differential transcriptional expression between Asymptomatic cases infected with VOC or wildtype SARS-CoV-2. (A) Principal component analysis helps to visualize the clustering of COVID-19 Asymptomatic cases infected with wildtype, or VOC (n = 5) strains. (B) A barplot depicts the hierarchical clustering of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) as Upregulated (red) or Downregulated (green) between individuals infected with VOC as compared with VOC. (C) A volcano plot of DEGs between infection with VOC or wt infections. The x-axis is labelled by fold change and y-axis shows –log10(p-value), the red dot depicts up-regulated genes and blue represents downregulated genes. (D) GSE of Biological processes run on the DEGs. (E) GSE WikiPathways analysis is depicted. Pathways details are displayed on the y-axis and gene ratio is plotted on x-axis. The greater the size of circle the greater the number of genes involved in a pathway; the circles are colored based on p-adjusted value.

We next screened the DEGs for inflammatory pathway related genes and ISGs, observing the upregulation of inflammatory genes TNFA, CXCL8 and CCL3 but downregulation of T cell chemoattractants CXCR2 and CXCR1 in those infected with VOC as compared with wt (S Table 7). Amongst ISGs, Interferon responses were inhibited as seen by downregulation of IFIT6, IFII6, MAVS, OAS3, SAMD3, TRIM22, TRIM56. This further demonstrates that VOC infections reduced ISG responses in the host.

Discussion

We used a transcriptomic approach to study gene expression in whole blood comparing COVID-19 subjects with differing disease severities and investigating transcriptional signatures by comparing SARS-CoV-2 VOC with wildtype strains. Our data show that VOC such as the delta variant downregulate host anti-viral responses through interferon stimulated genes, innate immunity through chemokine activation, T cell development and erythropoiesis by downmodulating erythrocyte and heme function. We observed VOCs enhanced host inflammatory pathways such as VEGFalpha and ribosomal pathways to be associated with increased viral mRNA translation. This is the first report describing VOC- induced host transcriptional profiles in a population that experienced a low burden of COVID-19 disease associated morbidity.

We first focused on the comparison of COVID-19 patients with Symptomatic or Asymptomatic disease. The age of Symptomatic COVID-19 cases was older than those who had Asymptomatic COVID-19. Symptomatic cases were those admitted to the hospital for treatment and therefore this trend fits with data showing older age to be associated with increased COVID-19 severity. Transcriptional profiles of those with Symptomatic as compared with Asymptomatic COVID-19 revealed an increase in inflammatory responses as well as cellular signaling associated with increased pathogenesis in COVID-19, Fig. 2. The upregulation of neutrophil markers and apoptotic markers (BCL2A1 and ANXA3 likely reflects greater pathogenesis, tissue damage and cell death in symptomatic COVID-19. CXCL8 is reflective of exacerbation of inflammation and has been found to correlate with severity of acute SARS-CoV-2 infection25. Interleukins were activated; IL-1 is a pro-inflammatory cytokine involved in the initiation of immune responses, while IL-10 limits excessive inflammation. The TFPI gene (involved in coagulation and the complement pathway) was upregulated. TPFIs has been shown to be raised in delta infections in the macaque model20. In Symptomatic cases, lymphocyte differentiation was suppressed and adaptive immunity downmodulated, highlighted by reduced activation of CD28 co-stimulation and ZAP-70 pathways aligning with earlier reports of immune suppression in severe COVID-1926,27. TCF7, a transcription factor, crucial for T cell development and differentiation was downregulated in symptomatic COVID-1923. Previous ARDS data showed downregulation of adaptive immunity and T cell exhaustion, with T-cell apoptosis associated with T-cell depletion14.

Analysis of interferon-driven responses, showed upregulation of IL1, IL4, IL18, AREG, SOCS3, VEGFA and downregulation of IL12, IL2, IFNAR2, TGF, MAVS, IRF4, TRIM14, SAMDH1 in Symptomatic patients. Interferon-mediated signaling is critical in protection against SARS-CoV-2 and is negatively related to COVID-19 severity27,28. ISGs are proposed as part of predictive biomarker for assessment of disease outcomes18. The upregulation of Interferon-genes in the Asymptomatic COVID-19 patients matches earlier reports of from infection with SARS-CoV-2 wildtype variants17. Downregulation of MAVS in Symptomatic COVID-19 was confirmed through RT-PCR analysis (Fig. 2H). The expression of two heme pathway genes, HBB and ALAS2, through array-based DEG identification and RT-PCR were also found to be comparable, with a downregulation of ALAS2 in Symptomatic disease.

Comparison of the VOC-induced transcriptional profiles with wildtype strains revealed differing host genetic perturbations between variant types, Fig. 3. Overall, the majority of DEGs were upregulated. Comparing the ISG expression patterns between Symptomatic and Asymptomatic cases, as well as in the context of alpha, delta, and omicron variants, provides insights into the host immune response to SARS-CoV-2 (Fig. 3). Delta variants caused the greatest upregulation of ISGs (IFI44, IFI44L)29. ISGs control pathways induced during pathogen life cycles and are induced by IRF independent of JAK/STAT pathways30. The high fold change observed in IRAK3 in individuals with Symptomatic COVID-19 compared to Asymptomatic cases suggests a potential association between IRAK3 expression and disease severity. Expression of IRAK3 may reflect an attempt by the host immune system to regulate inflammation and outcome on disease severity.

DEGs induced by alpha variants were associated with cellular signaling and inflammatory factors SYVN1 (regulated the signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3)/vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) axis) and CH25H (inflammatory factor present in macrophage populations)24. Down-DEGs included those involved in NK cell activation and CD8-T cell activation (CST7), IL1RAPL2, as well as cellular signaling molecules associated with innate immunity such as, endocytosis (GBP1/2/5), TRIM22 involved in antiviral killing31 and, FCR3E involved in humoral responses (Fig. 4). The reduction of innate immune and defense response related processes may explain the increased virulence of alpha strains, previously reported to suppress innate responses to escape initial stages of host immunity32.

Between delta and wildtype strains, the greatest enhancement was seen in EGR1 (Fig. 5), a host transcription factor that inhibits SARS-CoV-2 replication through E3 ubiquitin pathway. EGR1 also inhibits the replication of viruses including CMV, SARS-CoV-2 and EBV33, and facilitates the transcription of immune genes including TNF, IL-2, IL-6, IL-8. Delta variants upregulated IFIT1 and IFI44L expression. This fits with earlier report that delta variants induce lower interferon expression than wildtype SARS-CoV-2 in vitro34. IFIT downregulation would likely negatively affect inflammatory and interferon responses as IFI44L as part of innate immune responses35. CCL2 along with cytoplasmic ribosomal proteins and RNA processing pathways and VEGFA-VEFFR2 pathway genes were upregulated. Ribosomal proteins play a critical role viral propagation36 and VEGF signalling indicates inflammatory pathway activation and viral replication. These data are concordant with increased inflammation and disease severity observed during the delta virus waves, globally37,38 and at our center in Karachi39. Delta infections downregulated genes related to erythrocyte synthesis and development (HBB, DMTN, SCL4A1, HBD9, GYPC). Of note, ALAS2, the most downregulated gene, is the enzyme responsible for the rate-limiting step in heme biosynthesis, catalyzing the synthesis of aminolaevulinic acid (ALA), the precursor of heme, from glycine and succinyl-CoA. Downregulation of ALAS2 could decrease in heme biosynthesis by feedback inhibition by high levels of heme or regulatory signals that suppress ALAS2 expression. Our results describing the impact of delta variants on RBC development align with earlier reports indicating that delta variant infections resulted in reduced RBC width, correlating with COVID-19 severity40.

Omicron versus wildtype infections displayed the greatest number of DEGs, including activation of viral mRNA translation, cytoplasmic ribosomal pathways, and RNA processing pathways while inflammatory and immune response pathways were suppressed, Fig. 6. EGR1 was the most upregulated DEG whilst ALAS2 was most downregulated. Notably, chemokine receptors, CXCR1 and CXCR2, as well as MGAM, markers of innate immunity, were also found downregulated. The upregulation of viral RNA translation and ribosomal pathways fits with the increased host protein synthesis observed during infections with higher viral loads. Previously it was shown that those infected with omicron had lower CT values indicating higher viral loads compared to the alpha variants, but omicron infections were associated with less severe in-patient mortality12. Mutations across various sites in Spike glycoprotein genes such as D614G, have facilitated increased viral entry and replication41, leading to immune escape32.

Vaccinations also impact transcriptional profiling of COVID-19 patients42,43.To focus on the mechanisms that are protective against controlling infection with VOC to prevent confounders due to vaccination, we focused only on unvaccinated Asymptomatic cases. Transcriptional profiles of those infected with VOC as compared with wildtype strains revealed upregulation of ribosomal genes, whilst downregulated genes involved in heme synthesis (ALAS2, HBB) as well as MAVS, an ISG (Fig. 7). A strong association is shown between anemia and increased mortality in COVID-19 patients44. Therefore, altered erythropoietic pathways as seen through transcriptional profiles of COVID-19 patients in our study may be a biomarker of severe disease in the patients. The activation of ribosomal pathways in COVID-19 patients infected with VOCs, indicating that the ribosomes are engaged in translating viral RNA into viral proteins thus increasing viral replication45. This suggests the delta and omicron variants replicate more efficiently than the wild type, potentially contributing to their increased transmissibility or virulence32.

Our data is unique that it sheds light on VOC infections in Asymptomatic individuals in a population which experienced relatively low COVID-19 morbidity through the pandemic. The reduced trend of ISGs after VOC infection fits data shown in the rhesus macaque model20. However, reports of infection with SARS-CoV-2 variants have varied in other models. A comparison of transcriptional responses to SARS-CoV-2 variants as compared with wildtype strains in rhesus macaques noted that VOC induced greater upregulation of RNAs involved in gene expression and metabolic pathways, but downregulated RNAs involved in cardiac contraction19. However, this study noted differential transcriptional changes in the study of tissues but not in blood gene expression profiles. Another study of SARS-CoV-2 variants conducted in cynomolgus macaques infected with delta and omicron variants showed differences only in TFPI2 gene which was upregulated in the alveolar ROIs of the delta-infected group compared to those of the omicron-infected group20. Of note, we found TFPI to be upregulated only in the comparison between Symptomatic as compared with Asymptomatic infections, but not in a VOC-specific manner.

Our data supports the view that that alpha and delta have progressively evolved over the ancestral variants by silencing the innate immune response46. Reduced neutralizing activity against variants has been demonstrated in the context of alpha, delta and omicron infections with mutations such as, N501Y and E484K which were first shown to be associated with antibody escape in the host47. Increased inflammation in individuals infected with alpha and delta as compared with wildtype variants fits with COVID-19 trends observed in the population from the UK, with an increase in deaths due to alpha variants48. Studies from Brazil and Singapore also reported increased severity of disease in COVID-19 patients with the gamma variant and delta variant respectively49. In Europe, the CFR from infections with omicron was significantly lower as compared with delta38. In Pakistan, studies showed that delta variants were associated with increased risk of severe disease39, and also that omicron was associated with reduced in-hospital mortality12.

A limitation of our study was that the sample size for VOC was relatively small. However, this was limited by the number of individuals on whom we had SARS-CoV-2 variant data based on NGS or RT-PCR, and on the number of individuals who consented to the study. Unfortunately, we were unable to include omicron infected individuals who were unvaccinated and Asymptomatic to compare in this cohort. By the time omicron infections were introduced in Pakistan, a large majority of the population had received COVID-19 vaccinations50. Also, we do not have longitudinal transcriptional profiles of the COVID-19 cases, to see what changes may occur as their infections progress or resolve. RT-PCR based studies could be conducted on a selected number of cases for a limited number of gene targets due to the limited availability of RNA. However, the results of our mRNA levels comparison for the dataset studied were comparable to the result of the DEGs for the same, validating our results. Whilst we have results for only a single sample from each COVID-19 case, we do know that of the 32 individuals with asymptomatic infections, only two progressed to have severe disease whilst the others recovered well. Although our data set was small, it is robust in the classification of COVID-19 cases and therefore provides insights into infections wildtype and VOCs.

Overall, our data highlights the role of interferon-pathways in protection against viral diseases and ISGs as markers predictive of immune clearance. Our work describing the effect of VOCs provides key insights by identifying genes involved in pathways that related to erythrocyte development and suggest these as potential targets which can be explored further to reduce the negative impact observed in patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 strains.

Methods

Ethics approval

This study received approval from the Ethics Review Committee of the Aga Khan University (AKU). All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. All study subjects were aged over 18 years. Informed consent was taken from all study subjects or their adult next of kin.

Laboratory tests

Diagnostic testing was performed at the AKUH Clinical Laboratory, Karachi. Nasopharyngeal swab samples from patients were tested using the COBAS® SARS-CoV-2 assay (COBAS® 6800 Roche platform). COVID-19 patients were those who had a positive SARS-CoV-2 PCR assay diagnosed from the section of Molecular Pathology, Aga Khan University Hospital Clinical Laboratories, Karachi.

Study subjects

COVID-19 patients included in the study were recruited between April 2021 and May 2022. All COVID-19 cases had a respiratory sample which was positive for SARS-CoV-2 by PCR within 48 h prior to collection of blood samples Six individuals included those recruited by the Aga Khan University COVID-19 biorepository. They were anonymized by the biorepository who was able to provide necessary samples together with data variables. Data collected on COVID-19 patients included information regarding clinical history, co-morbid conditions, vaccination status.

COVID-19 cases were classified according to their disease severity fined by the WHO ordinal score21. In this study, we categorized those with scores 1–2 as Asymptomatic and those with scores of 3 and over as Symptomatic COVID-19 cases. Asymptomatic cases were those who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 at the AKUH clinical laboratory and received a positive COVID-19 diagnosis. They were approached to volunteer for the study. These individuals were either completely asymptomatic or had a short (1–2 days) history of fever, sore throat or myalgia which subsequently resolved. Asymptomatic cases were detected by a diagnostic test. None from this group required any medical treatment.

Symptomatic cases were all admitted to AKUH at the time of recruitment. Samples from Symptomatic cases were taken prior to interventions such as, an anti-viral agent, or IL-6 antagonist. Symptomatic cases required oxygen support and their disease severity ranged from moderate to critical.

SARS-CoV-2 variant identification

COVID-19 cases chosen were those for whom SARS-CoV-2 RNA present in respiratory swabs of COVID-19 cases was performed using PCR-based variant testing and Illumina-sequencing as described previously6,50,51.

had been sequenced and identified as per VOC; Alpha, Beta, Gamma, Delta and Omicron lineages6,17.

RNA microarray data

RNA was extracted from whole blood collected in plasma/EDTA tube using the Qiagen RNA Blood Mini Kit (Qiagen, GmbH, Germany). One hundred nanogram of RNA was used for the preparation of cRNA for use in the Clariom S Array Type gene expression, Affymetrix, USA. The arrays were scanned using an Affymetrix autoloader system. Array data was generated and used for processing. For accession number generation, array output raw files (CEL files) and processed files (CHP) were submitted to Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) NCBI and available as Bioproject numbers PRJNA737074 GSE177477 and GSE269780 and are listed in S Table 8.

Functional enrichment analysis

CEL files were analysed using the TAC Transcriptome Analysis Software Suite (TACS version 2) using the Summarization Method: Gene Level - SST-RMA Pos vs. Neg AUC Threshold: 0.7 against Genome Version: hg38 (Homo sapiens). Cellular pathway analysis of significant differentially expressed genes (DEGs) up- or down-regulated (log FC (fold change) < -2 or > 2; FDR adjusted P value < 0.05) were identified by TAC software. Significantly modified pathways were sub-grouped. Further, hierarchical clustering and volcano plots were made using TACS.

To obtain further insights into the function of the differentially expressed genes (DEGs), we performed Gene Ontology (GO) analysis52 and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway enrichment analysis, using clusterProfiler53–57. The R package clusterProfiler, perform statistical methods to analyze and visualize functional profiles (GO and KEGG) of gene and gene clusters56. We use two types of functions from clusterProfiler i.e., enricher function (enrichGO, enrichKEGG) for hypergeometric test and GSEA (gseGO, gseKEGG) function for gene set enrichment analysis on user defined data. GO enrichment analysis is carried out employing enrichGO function which requires a gene list as input vector. The results are annotated along three ontologies: Molecular Functions, Biological Processes and Cellular Components with the following parameters: pvalueCutoff = 0.05, pAdjustMethod = “BH” (Benjamani and Hochberg) and qvalueCutoff = 0.05. While the enrichKEGG is simpler, it requires a gene-list as input, parameter of pvalueCutoff = 0.05 and organism of interest (homo sapiens “hsa”). Gene set enrichment analysis is performed on GO terms using gseGO which requires gene-list in the form of input vector, organism of interest (database: org.Hs.eg.db), pvalueCutoff = 0.05, minGSSize (minimal size of genes annotated by Ontology term for testing) = 10 and maxGSSize (maximum number of genes annotated for testing) = 800. gseKEGG function is similar with respect to input parameters (genelist, organism = hsa, minGSSize, maxGSSize and pvalueCutoff), applied on KEGG database. Additional analysis was performed on wiki-pathways, using enrichWP (organism = “Homo sapiens” ) and gseWP (organism = “Homo sapiens” ). Reactome pathway was also performed as it can analyse multiple datasets simultaneously for comparative pathway analysis. The function used was gsePathway (geneList, pvalueCutoff = 0.2, pAdjustMethod = “BH”). For visualization of results related R packages such as GOplot, enrichplot, DOSE and pathview were used to generate pathway maps, dotplots, heatmaps and barplot57–59.

mRNA gene expression

cDNA was synthesized from 200 ng RNA using the RevertAid First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Cat #K1621) as per the manufacturer’s instructions. RT-PCR was performed for targets (MAVS, OAS1, IFN-a, IFI44, HBB and ALAS2) with HuPO used as a housekeeping genes using 5 pmol concentration each. Primer sequences are listed in S Table 9. Real-time PCR was performed in duplicate with 2 µl of diluted cDNA using SYBR® Green PCR master mix (Applied Biosystems cat #4309155) on the CFX Opus-96 (Bio-Rad) equipment. The relative amount of gene target/HuPO transcripts was calculated using the 2−(DDCt) method as described previously60.

Statistical analysis

Differences between age groups and lab parameters were compared using Kruskal-Wallis test. Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare gene expression data. Analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 10. s.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Section of Molecular Pathology, Aga Khan University Hospital Clinical Laboratories and the Aga Khan University COVID-19 biorepository for providing samples for the study. We thank Shama Qaiser for technical assistance in the study.

Author contributions

ZH, MM, JA and KIM, RH and AN wrote the main manuscript text. MY and ZH conducted the experimental work. MM and JA conducted the data analysis and prepared figures. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Funding

This study was received funding by a Grand Challenges Fund – grant number 913, Higher Education Commission (HEC), Pakistan.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article (and its Supplementary Information files). Data was submitted to Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) NCBI and available as Bioproject numbers PRJNA737074 GSE177477 and GSE269780.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.JHU. Coronavirus Resource Center. https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html (2023).

- 2.Zhao, D. et al. A comparative study on the clinical features of Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) Pneumonia With Other Pneumonias. Clin. Infect. Dis. 71(15), 756–761 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Korber, B. et al. Tracking changes in SARS-CoV-2 spike: evidence that D614G increases infectivity of the COVID-19 Virus. Cell. 182(4), 812–827e19 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aldridge, R. W. et al. SARS-CoV-2 antibodies and breakthrough infections in the Virus Watch cohort. Nat. Commun. 13(1), 4869 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Williams, H. H. & Stone, D. H. Watching Brief: The evolution and impact of COVID-19 variants B. 1.1. 7, B. 1.351, P. 1 and B. 1.617. Glob. Biosecurity. 3 (2021).

- 6.Nasir, A. et al. Tracking SARS-CoV-2 variants through pandemic waves using RT-PCR testing in low-resource settings. PLOS Glob Public. Health. 3(6), e0001896 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Umair, M. et al. Genomic surveillance reveals the detection of SARS-CoV‐2 delta, beta, and gamma VOCs during the third wave in Pakistan. J. Med. Virol. 94(3), 1115–1129 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ren, W. et al. Characterization of SARS-CoV-2 variants B.1.617.1 (Kappa), B.1.617.2 (Delta), and B.1.618 by cell entry and immune evasion. mBio, e0009922. (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Lambrou, A. S. et al. Genomic surveillance for SARS-CoV-2 variants: predominance of the Delta (B.1.617.2) and Omicron (B.1.1.529) variants - United States, June 2021-January 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 71(6), 206–211 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tian, D. et al. The global epidemic of the SARS-CoV-2 Delta variant, key spike mutations and Immune escape. Front. Immunol. 12, 751778 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peng, Y. et al. Broad and strong memory CD4 + and CD8 + T cells induced by SARS-CoV-2 in UK convalescent individuals following COVID-19. Nat. Immunol. 21(11), 1336–1345 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mushtaq, M. Z. et al. Exploring the relationship between SARS-CoV-2 variants, illness severity at presentation, in-hospital mortality and COVID-19 vaccination in a low middle-income country: a retrospective cross-sectional study. Health Sci. Rep., 6(12). (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Masood, K. I. et al. Humoral and T cell responses to SARS-CoV-2 reveal insights into immunity during the early pandemic period in Pakistan. BMC Infect. Dis. 23(1), 846 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wu, P. et al. The trans-omics landscape of COVID-19. Nat. Commun. 12(1), 4543 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhao, P. et al. Immune features of COVID-19 convalescent individuals revealed by a single-cell RNA sequencing. Int. Immunopharmacol. 108, 108767 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang, X. et al. Dysregulated hematopoiesis in bone marrow marks severe COVID-19. Cell. Discov. 7(1), 60 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Masood, K. I. et al. Upregulated type I interferon responses in asymptomatic COVID-19 infection are associated with improved clinical outcome. Sci. Rep. 11(1), 22958 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Armignacco, R. et al. Whole blood transcriptome signature predicts severe forms of COVID-19: results from the COVIDeF cohort study. Funct. Integr. Genomics. 24(3), 107 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Du, T. et al. Differential transcriptomic landscapes of SARS-CoV-2 variants in multiple organs from infected Rhesus macaques. Genomics Proteom. Bioinf. 21(5), 1014–1029 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oh, T. et al. Comparative spatial transcriptomic profiling of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 Delta and Omicron variants infections in the lungs of cynomolgus macaques. J. Med. Virol. 95(6), e28847 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Organization, W. H. Ordinal Scale for Clinical Improvement. (2020).

- 22.Ghanchi, N. K. et al. Higher entropy observed in SAR-CoV-2 genomes from the first COVID-19 wave in Pakistan. PLoS ONE. 16(8), e0256451 10.1371/journal.pone.0256451 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Zhang, J. et al. Role of TCF-1 in differentiation, exhaustion, and memory of CD8(+) T cells: a review. FASEB J. 35(5), e21549 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Canfran-Duque, A. et al. Macrophage-derived 25-hydroxycholesterol promotes vascular inflammation, atherogenesis, and Lesion Remodeling. Circulation. 147(5), 388–408 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Henriquez, K. M. et al. Association of interleukin-8 and neutrophils with nasal symptom severity during acute respiratory infection. J. Med. Virol. 87(2), 330–337 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aschenbrenner, A. C. et al. Disease severity-specific neutrophil signatures in blood transcriptomes stratify COVID-19 patients. Genome Med. 13(1), 7 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kramer, B. et al. Early IFN-alpha signatures and persistent dysfunction are distinguishing features of NK cells in severe COVID-19. (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Zhang, J. et al. Transcriptome changes of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells in the Peripheral blood of COVID-19 patients by scRNA-seq. Int. J. Mol. Sci., 24(13). (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Busse, D. C. et al. Interferon-induced protein 44 and interferon-induced protein 44-like restrict replication of respiratory syncytial virus. J. Virol., 94(18). (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Schoggins, J. W. & Rice, C. M. Interferon-stimulated genes and their antiviral effector functions. Curr. Opin. Virol. 1(6), 519–525 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lian, Q. & Sun, B. Interferons command Trim22 to fight against viruses. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 14(9), 794–796 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harvey, W. T. et al. SARS-CoV-2 variants, spike mutations and immune escape. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 19(7), 409–424 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Woodson, C. M. & Kehn-Hall, K. Examining the role of EGR1 during viral infections. Front. Microbiol. 13, 1020220 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Laine, L. et al. SARS-CoV-2 variants alpha, Beta, Delta and Omicron show a slower host cell interferon response compared to an early pandemic variant. Front. Immunol. 13, 1016108 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.John, S. P. et al. IFIT1 exerts Opposing Regulatory effects on the inflammatory and Interferon Gene Programs in LPS-Activated human macrophages. Cell. Rep. 25(1), 95–106e6 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li, S. Regulation of ribosomal proteins on viral infection. Cells, 8(5). (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.Ong, S. W. X. et al. Clinical and virological features of severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) variants of concern: a retrospective cohort study comparing B.1.1.7 (alpha), B.1.351 (Beta), and B.1.617.2 (Delta). Clin. Infect. Dis. 75(1), e1128–e1136 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nyberg, T. et al. Comparative analysis of the risks of hospitalisation and death associated with SARS-CoV-2 omicron (B.1.1.529) and delta (B.1.617.2) variants in England: a cohort study. Lancet. 399(10332), 1303–1312 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mwendwa, F. et al. Shift in SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern from Delta to Omicron was associated with reduced hospitalizations, increased risk of breakthrough infections but lesser disease severity. J. Infect. Public. Health. 17(6), 1100–1107 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang, J. et al. Association between Red Blood cell distribution width and COVID-19 severity in Delta variant SARS-CoV-2 infection. Front. Med. (Lausanne). 9, 837411 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Laha, S. et al. Characterizations of SARS-CoV-2 mutational profile, spike protein stability and viral transmission. Infect. Genet. Evol. 85, 104445 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Qi, F. et al. Single-cell analysis of the adaptive immune response to SARS-CoV-2 infection and vaccination. Front. Immunol. 13, 964976 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang, Y. et al. Single-cell transcriptomic atlas reveals distinct immunological responses between COVID-19 vaccine and natural SARS-CoV-2 infection. J. Med. Virol. 94(11), 5304–5324 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bellmann-Weiler, R. et al. Prevalence and Predictive Value of Anemia and Dysregulated Iron Homeostasis in patients with COVID-19 infection. J. Clin. Med., 9(8). (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 45.Maurya, R. et al. Intertwined dysregulation of ribosomal proteins and immune response delineates SARS-CoV-2 vaccination breakthroughs. Microbiol. Spectr. 11(3), e0429222 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tandel, D. et al. SARS-CoV-2 variant delta potently suppresses innate immune response and evades Interferon-activated antiviral responses in human colon epithelial cells. Microbiol. Spectr. 10(5), e0160422 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Alenquer, M. et al. Signatures in SARS-CoV-2 spike protein conferring escape to neutralizing antibodies. PLoS Pathog. 17(8), e1009772 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Challen, R. et al. Risk of mortality in patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 variant of concern 202012/1: matched cohort study. BMJ. 372, n579 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nonaka, C. K. V. et al. SARS-CoV-2 variant of concern P.1 (Gamma) infection in young and middle-aged patients admitted to the intensive care units of a single hospital in Salvador, northeast Brazil, February 2021. Int. J. Infect. Dis. (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 50.Bukhari, A. R. et al. Sequential viral introductions and spread of BA.1 across Pakistan provinces during the Omicron wave. BMC Genom. 24(1), 432 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nasir, A. et al. Evolutionary history and introduction of SARS-CoV-2 Alpha VOC/B.1.1.7 in Pakistan through international travelers. Virus Evol. 8(1), veac020 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Huang da, W., Sherman, B. T. & Lempicki, R. A. Bioinformatics enrichment tools: paths toward the comprehensive functional analysis of large gene lists. Nucleic Acids Res. 37(1), 1–13 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kanehisa, M. Toward understanding the origin and evolution of cellular organisms. Protein Sci. 28(11), 1947–1951 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kanehisa, M. & Goto, S. KEGG: kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 28(1), 27–30 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kanehisa, M. et al. KEGG for taxonomy-based analysis of pathways and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 51(D1), D587–D592 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yu, G. et al. clusterProfiler: an R package for comparing biological themes among gene clusters. OMICS. 16(5), 284–287 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yu, G. et al. DOSE: an R/Bioconductor package for disease ontology semantic and enrichment analysis. Bioinformatics. 31(4), 608–609 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yu, G. Enrichplot: Visualization of Functional Enrichment Result (p. R package, 2021).

- 59.Luo, W. & Brouwer, C. Pathview: an R/Bioconductor package for pathway-based data integration and visualization. Bioinformatics. 29(14), 1830–1831 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Livak, K. J. & Schmittgen, T. D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25(4), 402–408 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article (and its Supplementary Information files). Data was submitted to Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) NCBI and available as Bioproject numbers PRJNA737074 GSE177477 and GSE269780.