Summary

The Aba family played a pivotal role in Medieval Hungary, dominating vast territories and producing influential figures. We conducted an archaeogenetic study on remains from the necropolis in Abasár, the political center of the Aba clan, to identify family members and explore their genetic origins. Using Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS) data from 19 individuals and radiocarbon dating, we identified 6 Aba family members with close kinship ties. Four males carried identical N1a1a1a1a4∼ haplogroups, and our phylogenetic analysis traced this royal paternal lineage back to Mongolia, indicating migration to the Carpathian Basin with the conquering Hungarians. Genome analysis, including ADMIXTURE, principal-component analysis (PCA), and qpAdm, revealed East Eurasian genetic patterns, aligning with our phylogenetic findings. Identity by descent (IBD) analysis confirmed family kinship and revealed connections to prominent Hungarian noble families like the Árpáds, Báthorys, and Corvinus, as well as to the first-generation immigrant elite of the Hungarian conquest.

Subject areas: Archaeology, History, Genomics

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

With WGS and 14C dating we identified six members of the Medieval Hungarian noble Aba family

-

•

We determined that Aba’s paternal lineage belongs to haplogroup N1a1a1a1a4∼, of Asian origin

-

•

Genome analysis revealed East Eurasian genetic patterns in the Abasár genomes

-

•

IBD sharing indicated extensive kinship network among Abas and other Hungarian noble families

Archaeology, History, Genomics

Introduction

Over the past few decades, the collaboration between archaeology and archaeogenetics has opened up new avenues for identifying the remains of renowned historical figures and exploring their familial history. Such combined methods enabled the identification of Richard III’s skeleton,1 the remains of Romanov family members,2 or Birger Magnusson, the founder of Stockholm.3 This approach was also the key to identify the famous Hungarian king, Matthias Corvinus’ descendants,4 or the members of the Báthory family, one of the most prominent aristocratic families of Medieval Central Europe.5 Archaeogenetic methods have also facilitated the identification of members of the Árpád dynasty, Hungary’s first royal family, and to analyze their genomic heritage.6,7,8,9 Hence, archaeogenetics has become a valuable method for addressing both prehistoric and historic inquiries.

The Abas were one of the most prominent Hungarian noble families, holding extensive territories in Heves County (Northern Hungary) during the Middle Ages. The ethnic origin of the Aba family is a subject of controversy in historical records.10 According to the first surviving Hungarian medieval historical text Anonymus’ Gesta, Ed and Edemen, the progenitors of the clan, were identified as Cuman chiefs who had aligned themselves with the tribal alliance of the conquering Hungarians in present-day Russia prior to the Hungarian Conquest. As a result, they were granted extensive territories in Northern Hungary by Prince Árpád10,11,12,13 Since we know that the Cumans only moved to this area in the mid-11th century, it seems that Anonymus’ text anachronistically referred to the population, which living here before the arrival of the people of Almos and Árpád as Cuman.14 According to the 13th-century historian Simon of Kéza and later the 14th-century Chronicon Pictum, the forefathers of the clan, Ed and Edemen were the sons of Csaba, who was the legendary son of Attila, the grand King of Huns, according to medieval Hungarian historical tradition.12,13,15,16 The latest historical work, Chorincon Pictum was the first to claim that the Abas and the Árpáds would have had a direct common ancestor, Attila’s son Csaba.12,16 Modern historians propose an Eastern origin for the family, as both the Cumans and Huns can trace their origins back to the East. The most plausible ancestral groups linked to the Aba lineage are the Kabar clans, who separated from the Khazar Khaganate and joined the Hungarians shortly before the conquest.12,17

The honored progenitor of the clan, Samuel Aba (Sámuel in Hungarian) (c. 990–1044), initially served as comes palatii (count of the court) to Hungary’s first Christian king, St. Stephen I (István I) who ruled from 1000 to 1038. Sámuel was the “sororius” of the first King. One possible explanation is that this meant that due to his elevated status, entered into marriage with one of the king’s sisters.12 The other possibility is that Samuel was the king’s sister’s son, so nephew.18 Thus, through this marriage and their descendants, the Abas established a kin relationship with the Árpád dynasty. Sámuel later ascended to the throne as the third monarch of the Kingdom of Hungary (ruled 1041–1044), becoming the country’s first elected king. It is assumed that Sámuel’s social and political advancement may have been influenced by his family’s presumed prominent noble origin.

Following the death of István I, the power passed to his nephew, Peter Orseolo (Péter I) (ruled 1038–1041 and 1044–1046). Péter ruled with a firm hand, appointing foreign nobles to key positions, which elicited discontent among the Hungarian populace. Consequently, a revolt erupted in 1041, resulting in Péter’s deposition and the subsequent enthronement of Sámuel Aba, who wielded significant influence among the rebels. However, his reign was short-lived. After three years of battling external and internal adversaries, he met his demise in the Battle of Ménfő in 1044, where he confronted claimant Péter, supported by the German monarch Henrik III.12,19,20

King Sámuel’s body was interred temporarily until the completion of the church he founded in Abasár—the political hub of the clan in the late 10th and early 11th centuries. Subsequently, a few years later, his remains were exhumed and laid to rest in the Abasár church.10,12,20,21 Despite Sámuel’s downfall, the family’s presence endured on the medieval Hungarian political landscape. While historical records from the 11th and 12th centuries lack information about the family, from the 13th century onwards, their names appear regularly in written sources. By this time, the clan had splintered into dozens of families, some of which possessed extensive territories within the kingdom. They wielded significant political influence as dignitaries and even oligarchs during the 13th to 15th centuries.22,23,24

It is presumed that Abasár retained its position as an important political center for the clan and served as the final resting place for numerous descendants. According to the Hungarian chronicles the monastery in Abasár was funded by Sámuel Aba in the first half of the 11th century, however, it was first documented in a diploma issued by king Béla IV in 126112,25. In later centuries, the monastery and its domains became the subject of numerous ownership disputes among different branches of the clan, including the Nánai Kompolti, Csobánka, and Ugrai families, and other Hungarian nobilities.25 By the end of the 14th century the significance of the monastery had increased as the abbot of Abasár was mentioned twelve times in the papal bulls of Popes Boniface IX and Gregory XII.25 At the end of the 16th century, the Nyáry family owned the possessions of the abbey, and then during the Ottoman occupation those fell into the hands of the white clergy.25 In the 17th century, the domains were embroiled in several ownership disputes, and the abbey subsequently vanished from the sources, decaying over time.26

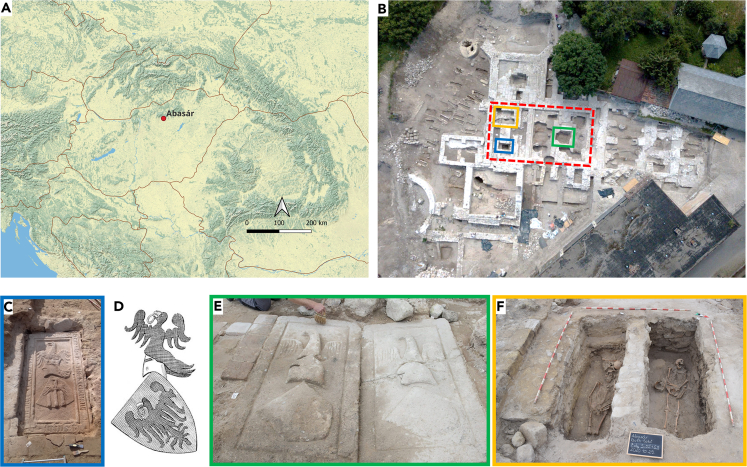

Between 2020 and 2022, the Department of Archaeology at the Institute of Hungarian Research conducted excavations at the Abasár Bolt-tető site in Northern Hungary, unveiling the remains of the church, primarily established by Sámuel Aba12,25 (Figures 1A and 1B). The excavation revealed various phases of the church’s existence, providing evidence of constructions, renovations, and instances of destruction. Although the tomb of the king could not be identified, graves belonging to notable members of the Aba family were discovered within the church building. In the sanctuary, an unearthed tomb with a stone cover (Figure 1C) featured a carved depiction of the Aba family’s coat of arms27 (Figure 1D) (for more details of the archaeological examination see Star Methods). The inscription on the border of the cover stone revealed that János and Mihály, two individuals from the Aba clan, were laid to rest there during the early years of the 15th century. Different branches of the Abas did rule extensive areas in Heves County in the 13th–14th centuries,23 and according to the medieval diplomas the monastery belonged to at least three different branches of the clan, as mentioned earlier.25 Thus, it is not clear which branch they exactly belonged to. Additionally, a double grave was found at the geometrical center of the church building, with its stone covers also adorned with the clan’s coat of arms (Figure 1E). Two more graves were uncovered within the sanctuary (Figure 1F), bringing the total count to at least five prominent burials that clearly belonged to significant family members. As in these graves multiple skeletons were discovered in multiple layers, in some cases it was hard to identify the prominent individuals with archaeological methods alone. For more details of the archaeological findings, see the description in the STAR Methods.

Figure 1.

Abasár Bolt-tető site

(A) The location of Abasár in Northern Hungary.

(B) The Abasár Bolt-tető site and the ruins of the monastery of Abasár viewed from above. The silhouette of the huge church building with the excavated graves is well discernible. The sanctuary is marked with a red dashed quadrate, while the exact positions of the prominent graves are indicated with yellow, blue and green quadrates respectively.

(C) The prominent burial in the sanctuary, at the altar district with the carved and scripted cover stone (HUAS57 and HUAS581) (Blue). The inscription indicates that outstanding members of the Aba family were buried in the grave.

(D) The stylistic depiction of the Abas’ coat of arms27 which can be observed on the cover stones.

(E) The double grave in the geometrical center of the church Phase I (HUAS261 and HUAS262) (green).

(F) The graves of HUAS55B and HUAS59B individuals in the altar district (yellow). The position of the burials refers to the prominence of the deceased inside.

Although the royal tomb and the king’s remains could not be identified, the archaeogenetic analysis of the interred individuals inside the church provided an unparalleled opportunity to explore the genetic origins of one of medieval Hungary’s most influential dynasties. As the paternal lineage of the Árpáds had previously been identified,6,7,8,9 we also had the opportunity to determine whether they shared the same paternal lineage as the Abas. We could also investigate the possible connection between the Abas and the members of other remarkable aristocratic families of medieval Hungary, the Báthory and Corvinus families4,5 (for their short description see STAR Methods).

In this study, we present the results of our archaeogenetic investigation, employing a combination of archaeological and genetic methodologies to identify the family members, establish their kin relations, and analyze the phylogenetic connections of the Abas’ paternal lineage. Furthermore, we employ state-of-the-art genome analysis techniques to delineate their ancestral heritage.

Results

The medieval genomic dataset from Abasár

Owing to medieval customs, kings and prominent figures were interred within the confines of churches. Therefore, we collected samples from all the skulls excavated within the edifice. Multiple burials were discovered in the prominent graves within the sanctuary and at the geometric center of the church, but through careful analysis, we were able to identify the primary graves of potential members of the Aba family. These prominent remains are referred as HUAS55B, HUAS57, HUAS581, HUAS59B, HUAS261, and HUAS262 throughout the study. For a comprehensive account of the excavation and archaeological discoveries, please refer to the STAR Methods.

DNA was successfully extracted from the total of 38 indoor remains from Abasár. Double-stranded sequencing libraries were constructed, incorporating partial UDG treatment (refer to Table S1). The libraries from 19 Abasár samples met the quality criteria and were sequenced to achieve a 1.6x average genome coverage (0.5–3.11x). The observed postmortem damage (PMD) ratio aligned with the general patterns of ancient DNA. Rigorous testing for contamination in mitochondrial DNA and heterozygosity of polymorphic sites on the X chromosome in males revealed a minimal level of contamination in our dataset. Applying the genetic sex estimation method of Skoglund et al. 2013,28 two remains were identified as genetically female, while the remaining samples, were conclusively identified as males (Table S1). More detailed information on DNA extraction, library preparation, sequencing, PMD, contamination, and sex determination, is also provided in Table S1.

Radiocarbon analysis of nine skeletons dated the Abasár site to the period ranging from the 12th to 15th century CE (Table 1; Supplementary table 1; Figures S5–S13). This analysis corroborated historical and preliminary archaeological data, confirming that the burials can be attributed to the era of the medieval Kingdom of Hungary. Specifically, three notable individuals from stone-covered graves were dated from the late 13th to the end of the 14th century, closely matching the approximate date engraved on the stone cover indicating the burials took place in the very early years of the 15th century. However, radiocarbon dating generally lacks the precision needed to accurately distinguish between two consecutive generations, as illustrated by our samples mentioned further.

Table 1.

Radiocarbon data of the studied remains

| Sample type | Cal. CE | |

|---|---|---|

| HUAS261 | tooth | 1277–1301 (88.4%); 1371–1378 (7%) |

| HUAS262 | tooth | 1278–1301 (87.8%); 1371–1378 (7.6%) |

| HUAS309 | tooth | 1305–1365 (76.6%); 1383–1398 (18.9%) |

| HUAS341 | tooth | 1455–1505 (78.8%); 1596–1618 (16.6%) |

| HUAS390 | tooth | 1169–1222 (95.4%) |

| HUAS450 | tooth | 1301–1329 (43.8%); 1341–1369 (29.3%); 1379–1396 (22.3%) |

| HUAS55B | rib | 1276–1300 (92.6%); 1372–1377 (2.8%) |

| HUAS57 | tooth | 1279–1303 (79%); 1368–1379 (16.4%) |

| HUAS59B | rib | 1300–1325 (43.7%); 1352–1395 (51.7%) |

All Abasár samples were dated to the era of the medieval Kingdom of Hungary, corresponding to historical data. See also Supplementary table 1 and Figures S5–S13.

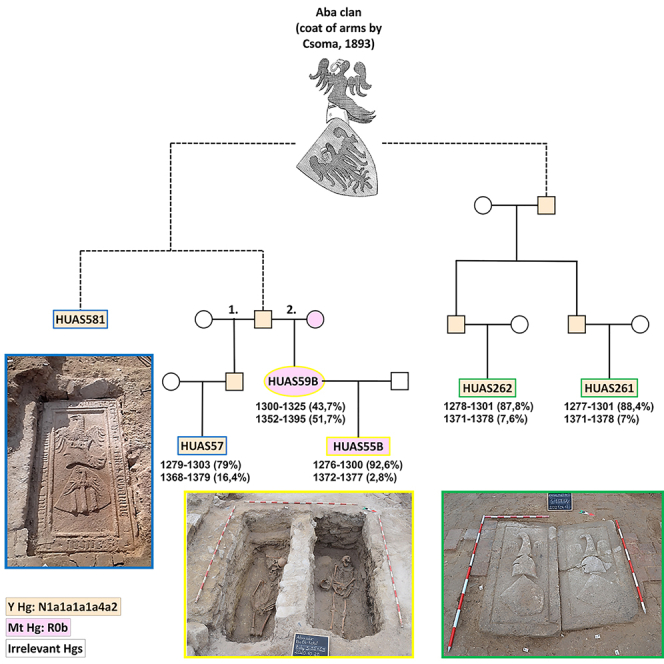

Kinship analysis

As the Abasár Bolt-tető site was believed to be the family cemetery of the Aba clan, we anticipated discovering kin relationships as well as identical uniparental haplotypes among the individuals under investigation.

The kinship analysis using correctKin revealed several family connections further supported by the uniparental data. Two small families were identified from the prominent graves mentioned earlier: one comprising four individuals (HUAS55B, HUAS59B, HUAS57, and HUAS581) and another consisting of two individuals (HUAS261 and HUAS262) (see Table S2).

The family of four, including one female and three males, was excavated from the sanctuary of the church. Two males, HUAS57 and HUAS581, turned out to be 5th degree relatives. Notably, these were uncovered from the grave with the carved stone cover (Figure 1C) of which inscription indicates that two significant male members of the clan were buried there. Two other members of the same family, HUAS55B male and HUAS59B female, were excavated from two uncovered tombs in the sanctuary (Figure 1F) and were found to be first-degree relatives of each-other with identical Mt haplotype. The HUAS59B female was a 3rd degree relative of HUAS57 and 4th degree relative of HUAS581 from the inscribed tomb, while the HUAS55B male was 4th degree relative of HUAS57 and its relation to HUAS581 could not be determined, as it was beyond 5th degree. HUAS55B and HUAS59B obviously were in a mother-son relationship, also confirmed by IBD analysis, as they shared 3477 centiMorgan (cM), the entire length of the genome with each-other (Table S7). For the reconstructed plausible family trees of this family refer to Figure S1.

The other two related male individuals (HUAS261 and HUAS262), found in the prominent stone-covered double grave in the geometric center of the church (Figure 1E), and were determined to be 3rd degree relatives. It is noteworthy that all four males unearthed from decorated tombs with cover stones shared the same N1a1a1a1a4∼ Y chromosome haplogroup, suggesting that two branches of the same extended family or clan were identified in this cemetery. Subsequent IBD analysis confirmed that the two families were indeed two branches of the same extended family.

Phylogenetic connections of the Aba paternal lineage

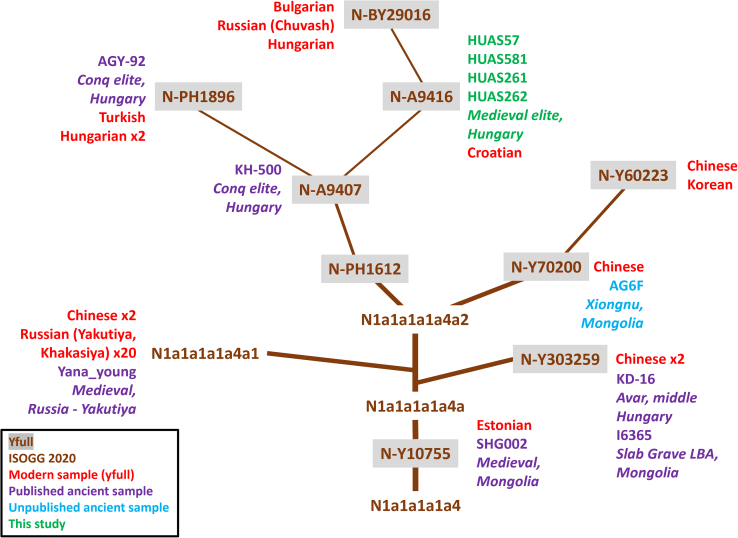

4 of 5 males in the extended Aba family carried identical N1a1a1a1a4∼ Haplogroup. Our comprehensive analysis revealed a diverse phylogenetic network of haplogroup N1a1a1a1a4∼, and its sub-branches (Figure 2). Utilizing the Yleaf software with the markers of ISOGG 2020, the Aba lineage could be classified within the N1a1a1a1a4a2∼ (N-A9408) sub-branch, except for the sample HUAS57, which lacked coverage over the A9408 marker of the haplogroup. Notably, two elite conquering Hungarians, along with an unpublished elite Xiongnu (AG6F) from the Ar Gunt site, Mongolia, also shared this sub-haplogroup. This suggests a Mongolian origin for the lineage that arrived in the Carpathian basin with the conquerors.

Figure 2.

The phylogenetic analysis of haplogroup N1a1a1a1a4

The tree was generated according to the data of ISOGG2020 and yfull.com. Haplogroup assignment of ancient sequences was conducted based on SNPs collected from each ancient genomes in the Y chromosome positions indicated in Table S3. The studied lineage of the Abas belongs to the N-A9416 subbranch near the branch of elite members of the conquering Hungarians. See also Table S3.

Enhancing our analysis with markers and modern data from the yfull database enabled us to position the ancient samples within the deeper branches of the phylogenetic tree. The N-A9408 haplogroup bifurcates into Eastern and Western branches. The Eastern branch, N-Y70200, is present in modern-day Chinese and Korean individuals, with the unpublished Xiongnu sample allocated to this sub-branch. The Western branch, N-PH1612, is predominantly found in Europeans, and after the haplogroup N-A9407 it further divides into two sub-branches: N-PH1896 and N-A9416. The conqueror samples belong to N-PH1896 and N-A9407, along with a contemporary Turkish individual and two Hungarians. The Aba lineage, along with a modern Croatian male, was assigned to N-A9416. The sub-haplogroup of N-A9416 is also present in a Hungarian, a Chuvash, and a Bulgarian individual.

The initial identification of haplogroup N1a1a1a1a4∼ traces back to a Mongolian individual from the Late Bronze Age Slab Grave culture.29 Presently, it exhibits the highest prevalence among Yakut males and is also notably common among Evenks and Evens.30 These findings strongly indicate an origin in Inner Asia. Our phylogenetic tree further supports this narrative, revealing that its sub-branch, N-PH1612, made its way to Europe and Hungary through medieval migrations including the conquering Hungarians.

Uniparental haplogroups and phylogenetic connections of the cemetery

The mitochondrial genomes from Abasár showed high heterogeneity, with 18 different haplotypes determined (Table S1C). HUAS55B and HUAS59B belonged to the same R0b haplotype, consistent with the result of the kinship analysis. Most of the mitochondrial lineages (14/18) have been detected in preceding populations of the Carpathian basin31,32,33 and several were present in the late medieval Hungarian elite cemetery of the Báthory family.5 Based on the comparison with our published ancient whole mitogenome database,31 eight lineages have a feasible Near Eastern (H13a1d, R0b, and T2) and/or Steppe origin (H28, T1a1, I1b, HV14a, and J1c5a), while the remainder are most probably of European origin.

As anticipated in the case of a family cemetery, the Y chromosomal haplogroups displayed much less diversity. Among the 17 males there were representatives from 13 different sub-branches of the Y chromosomal phylogenetic tree of ISOGG (https://isogg.org/tree/index.html). In addition to individuals belonging to the royal family with haplogroup N1a1a1a1a4∼, different I1∼, I2∼, R1a1a1b1∼, R1a1a1b2∼, and R1b ∼ lineages were represented by single individuals, while one pair belonged to haplogroup R1a1a1b1a2b3a3a2g2∼ (Table S1C). Similarly, to the mitochondrial lineages, most of the Y chromosome lineages (12/17) had European origin. A considerable number (7/17) were detected in preceding periods of the Carpathian basin, and several were prevalent among contemporary Hungarian elite.5,32 Besides the royal lineage, only one haplogroup with obvious Asian origin was detected: R1a1a1b2a2a3c2∼. It belongs to the Asian subbranch of R1a, specifically R1a-Z2125, which emerged in the Middle-Late Bronze Age among people of the Sintashta and Andronovo cultures. It was widespread among the Scythians and their descended populations.29,34,35,36 The sub-haplogroup found in Abasár has been detected in Hun samples,37 and its supergroups were prevalent among Huns and Avars in the Carpathian basin.32 It has also been found among the Pazyryk and Kangju peoples.38,39 Today, R1a1a1b2a2a3c2∼ is primarily observed in males from Eastern and Central Eurasia, with a higher prevalence in Russian Tatars.

Genomic heritage of the Abasár remains

The analysis of uniparental markers revealed an Inner-East Asian paternal origin for the Aba clan, raising the question of whether these ancestral ties were also discernible within their genomes. To address this question, we conducted genome analyses, leveraging the power of ADMIXTURE, principal-component analysis (PCA), and qpAdm.

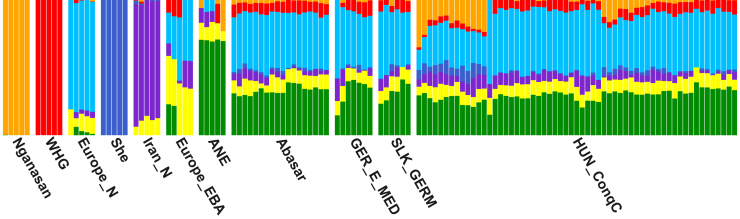

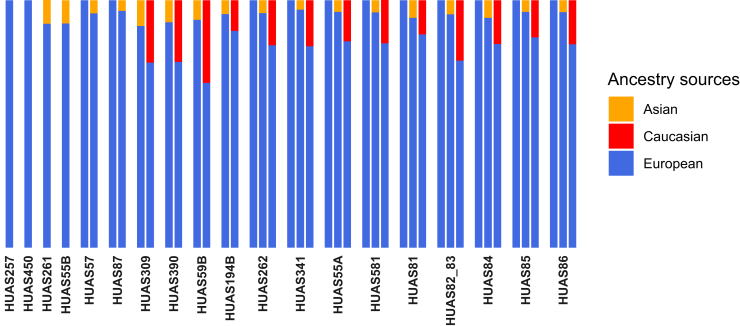

The ADMIXTURE analysis (K = 7) unveiled a strikingly similar genome component pattern between the Abasár group and Germanic populations from early medieval Germany and Slovakia. Additionally, Hungarian samples from commoner (village) cemeteries of the conquering period exhibited a remarkably comparable genetic profile too (Figure 3; Table S4). The Abasár genomes were composed of 0–3.5% Nganasan-, 6–11% Western Hunter-Gatherer-, 38–45% European neolithic farmer-, 0–3.5% She-, 0–9% Iranian neolithic-, 3,5–13% Early Bronze Age Western Eurasian- and 29–39% Ancient North Eurasian (ANE)-related genome components. The East Eurasian (Nganasan, She) components indicate the presence of minor eastern ancestry.

Figure 3.

Unsupervised ADMIXTURE analysis (K = 7) results of the Abasár individuals

Besides the early medieval population from Bavaria, Germany (GER_E_MED) and a Germanic group from modern-day Slovakia (SLK_GERM), the commoner people from the Hungarian conquering era of the Carpathian basin (HUN_ConqC) had the most similar genome composition to the Abasár samples. See also Table S4.

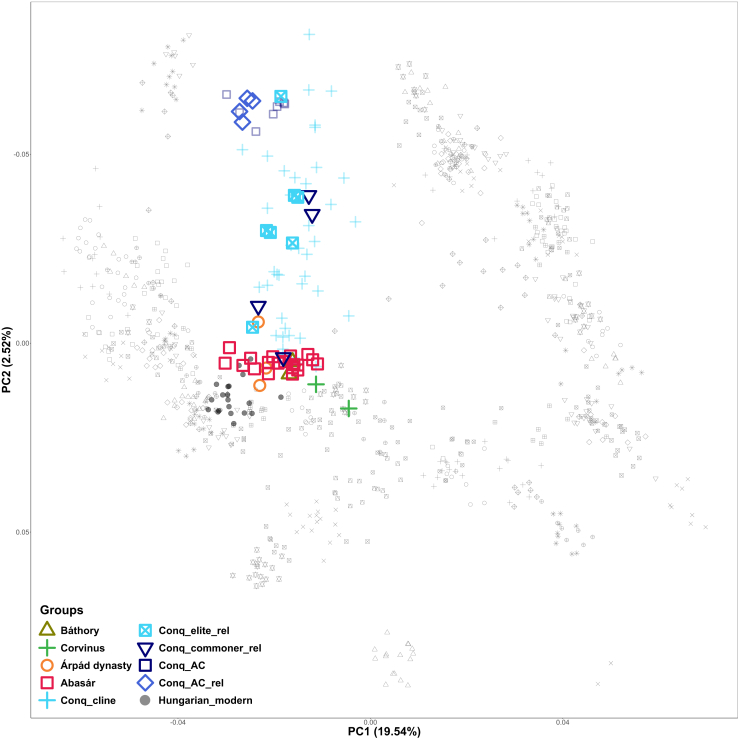

On the European PCA (Figures 4 and S2), the majority of the samples clustered together, separate from the cloud of Central European populations, shifted to the direction of the conquering Hungarians, with some outliers falling within the variance of present-day Hungarians. The Abasár cluster overlaps with the genomes of the Árpád dynasty, as well as with the two Báthorys, a prominent dynasty of late medieval Hungary and Poland.5 Notably, the Abasár cluster also overlaps with the cluster of other samples from the cemetery of the Báthory family at Pericei (Figure S3). As Abasár Bolt-tető site and the Pericei graveyard are thought to be aristocratic cemeteries, this observation suggests a characteristic and uniform genome composition for the medieval Hungarian noble stratum. On the Eurasian PCA, the Abasár group also exhibited a noticeable eastward genetic shift compared to modern Europeans (Figure S4). Moreover, most samples overlapped with the genetic cline of the conquering Hungarians from the 9th–11th centuries (Figures 4 and S4). Both ADMIXTURE and PCA findings underscored the eastern connections of the Abasár genomes, potentially linked to the subsequent influx of steppe immigrants into the Carpathian basin.

Figure 4.

European PCA of the Abasár genomes (red squares) projected onto the axes determined by 784 modern genomes (light gray shapes)

The studied samples form a distinct cluster from modern-day Central European peoples overlapping with the cline of the conquering Hungarians (skyblue crosses), and some outliers fall into the variance of present-day Hungarians (dark gray spots). The Abasár samples mapped close to the remains of the Báthorys (greenish brown triangles), the Corvins (green crosses) and the Árpád dynasty members (gold circles). The immigrant core group of the conquerors is also included (Conq_AC, dark blue squares). Conq_elite_rel (blue square with X-shape), Conq_commoner_rel (dark blue triangle) and Conq_AC_rel (blue diamonds) represent the conquerors sharing significant length of IBDs with the Abas based on our IBD sharing analysis (see below). See also Figures S2–S4.

To identify the plausible source of the Asian genome elements in the Abasár samples, we conducted qpAdm analysis. In the left population list, we included contemporaneous and preceding medieval populations from the Carpathian basin and Central Europe, a medieval group from Northern Caucasus (Anapa), and eastern immigrant groups of the Carpathian basin from the Middle Ages. The “base model strategy” run resulted in dozens of plausible two-source models for almost all samples (Table S6, summarized in Figure 5).

Figure 5.

qpAdm models for the medieval genomes from Abasár Bolt-tető site with significant p values

In most cases multiple models were valid with different European, Asian and Caucasian source combinations indicating a low amount of Asian ancestry in the Abasár genomes. See also Table S6.

Two samples (HUAS257 and HUAS450) could be modeled from single European sources, forming clades with Germanic or Carpathian basin sources, and two could be obviously modeled as an admixture of major European and minor Asian sources. In all other samples, qpAdm unequivocally indicated the admixture of European and different Eastern sources subserving the results of ADMIXTURE and PCA. Equivalent models of these genomes with comparable p values supported the single-source explanation or identified significant minor components of Asian (Hun/Avar/conquering Hungarian) and/or Caucasian origin. The average ratio of the Asian ancestry in these genomes ranged between 4.3–10.4%.

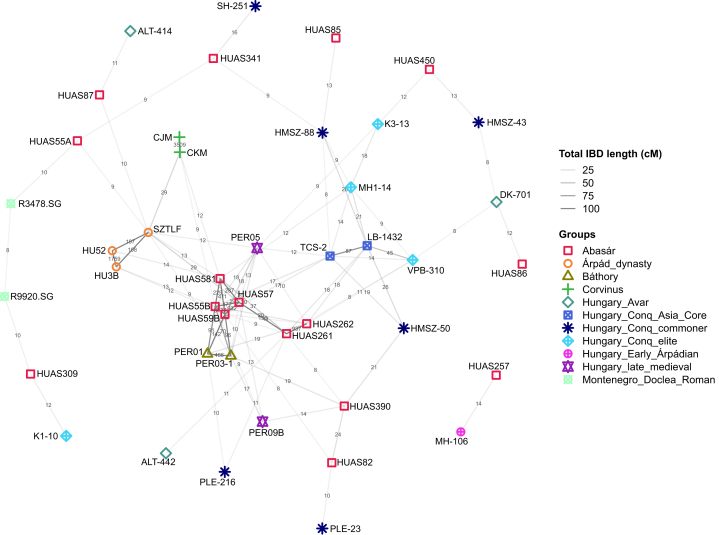

Shared IBD analysis

In order to identify genetic relations of the Abasár individuals at a finer scale, we utilized genome imputation and conducted IBD analysis using ancIBD (Table S7). We identified shared IBD segments longer that 8cM between the Abasár genomes and those of the Huns, Avars and conquering Hungarians published in the study by Maróti et al.32 We also tested IBD sharing with the additional medieval samples from Hungary, as the Pericei genomes5 the Corvinus4 and the Árpáds.8 In the IBD graph of Figure 6, we illustrated all detected IBD connections between the samples from Abasár and other samples with a minimum cumulative IBD length of 10 cM.

Figure 6.

Shared IBD network

The network indicates the IBD connections among the Abasár remains and other medieval individuals from the Carpathian basin, including the elite individuals of the conquering Hungarians, and the members of different aristocratic families as the Corvinus, the Báthorys and the Árpáds. The length of the edges linking the individuals is inversely proportional with the total length of shared IBDs between the two genomes. Total IBD length is indicated at the middle of each edge. The network was generated in R, with the packages igraph and ggplot2. See also Table S7.

First of all, the IBD graph distinctly illustrates the familial patterns, with cumulative lengths of shared IBD among family pairs closely aligning with their genealogical relatedness as measured by correctKin. Notably, this analysis revealed a significant amount of shared IBD among members of the two distinct families, indicating an approximately 6th–7th degree of relationship between them. This emphasizes the identification of two branches within a single extended family or clan. Furthermore, we identified two additional Abasár remains (HUAS390 and HUAS82) as distant relatives to the two families, suggesting that members of distantly related branches of the clan were also interred within the church. This observation aligns with historical data, which documents at least three branches of the clan governing the monastery during the 13th–15th centuries.

Importantly, based on shared IBDs, these families exhibit distant connections to medieval and early modern Hungarian noble lineages, including the Corvins4 and the Báthorys.5 The shared IBDs between some Abasár samples and members of the Árpád dynasty align with historical records, which document at least one marriage between the two families. Additionally, various samples excavated in Abasár share IBDs with different noble individuals but not with the aforementioned Aba family, suggesting their affiliation with other noble families of the Kingdom of Hungary.

The IBD connections to the immigrant core of the Hungarian conquering elite32 imply that the genetic relationship of the family to the conquerors predates the settlement of the Hungarians in the Carpathian basin. This conclusion aligns with the results of our phylogenetic investigation and definitively establishes that the minor eastern genomic component originates from the conquering Hungarians.

Discussion

Medieval Hungarian kings, including Sámuel Aba, were traditionally interred in churches, following the custom of Christian monarchs. While nearly half of the medieval Hungarian rulers found their final resting place in Székesfehérvár,40,41 within the coronating basilica founded by István I, the others were buried in temples that they had either privately funded or renovated for funeral purposes. Unfortunately, the ravages of time lead to the destruction of these temples, and the tombs of many kings were lost. Béla III’s intact burial discovered in 1848 in Székesfehérvár was a rare exception.42,43 According to Hungarian chronicles, Sámuel Aba was buried in the monastery of Abasár, a foundation attributed to him. However, the church associated with his burial site vanished over the centuries, and the Abasár Bolt-tető site was identified as the most likely location.25 The archaeological findings of the new excavation provided further evidence confirming that this was the monastery of the king.

In the stone graves inside the church, human remains were uncovered in primary anatomical order. Some tombs contained multiple skeletons arranged in both primary and secondary positions, indicating the reuse of graves across successive generations. Instances of an ossuary-like arrangement of skeletons indicated episodes where numerous remains were exhumed and then collectively reburied in common graves, possibly during reconstruction, rebuilding operations, grave robberies, or mass grave burials due to epidemics or wars. The part of the destruction is likely associated with the Mongol invasion of 1241-42, as the site is located along the marching route of Tatar troops, who were known to devastate Christian churches and plunder graves. Therefore, the archaeological investigation encountered difficulties in pinpointing the royal burial of Sámuel Aba.

Despite the inability to locate the king’s tomb, the excavations unearthed burials of prominent family members inside the church, underscoring the enduring significance of the church in the clan’s history. A double grave and a single tomb, all adorned with stone covers depicting the coat of arms of the Aba clan were discovered. The sanctuary tomb, with an inscription indicating the interment of János and Mihály, members of the genus, in the 15th century, aligned with historical records, that large territories in Heves county, including the monastery of Abasár, were possessed by different branches of the clan Aba, including the Kompolti, Ugrai, and Csobánka branches.22,23,25 Four males from these prominent graves shared the same Y chromosome haplogroup, likely representing two branches of the Aba family. The results of shared IBD analysis confirmed that two branches of one large family were uncovered in these tombs, and they obviously were nobilities as they had extended kinship network with other Hungarian noble families. Thus, archaeological and archaeogenetic data indicate that Aba clan members were identified at Abasár Bolt-tető site, and these results fit with the historical records.

Our IBD analysis has revealed dynastic connections among medieval Hungarian noble families, both those known from written sources and those previously unknown. The relationship through marriage was indicated in historical records between the Abas and the Árpáds,10,12,19 but we lack data in the relation of the Abas and the Báthorys, and also between the Abas and the Corvins. Nevertheless, we detected genealogical connections among all these prominent Hungarian families, indicating the existence of frequent marital relations in the noble stratum of the medieval Kingdom of Hungary, even it is undefinable that the identified connections derived from direct or indirect marriages between these families. The results also revealed direct connection between the Abas and the first generation immigrant core of the conquering Hungarians,32 suggesting that this connection predates the Conquest Period. It suggests that the forefathers of the Abas were the members of the wondering and conquering Hungarian tribes, aligning with the results of the phylogenetic connections as well.

Regarding the family’s ethnic roots, historical sources have proposed Hunnic and Cuman origins, but the prevailing consensus among historians tends to favor Khazar or Kabar ancestry,12,17 as well as direct conqueror nobility.10 Our phylogenetic results reveal that the paternal lineage of the family belongs to haplogroup N1a1a1a1a4∼, with Inner-Asian origin. This aligns with potential connections to the Hunnic, Cuman, Kabar, or Khazar groups. However, the more deeply characterized sub-haplogroup of the Aba paternal lineage, N-A9416, belongs to the N-PH1612 subgroup identified in Eastern Europe, with the majority of carriers located in present-day Hungary. Among them the oldest samples include two elite individuals from the conquering Hungarians. Notably, two additional conqueror samples with haplogroup N1a1a1a1a4∼ were identified.44 However, later they were excluded from our analysis because the haplogroup determination of these samples relied on a hybridization-based amplicon sequencing method, which lacked information about inner SNP markers. Taking all the available data into account, our results strongly support the association of the Abas’ paternal lineage with an elite paternal line among the conquering Hungarians. The paternal ancestors of the Aba family could potentially include one of the high ranked persons of the conquering Hungarian tribes.

In Hungarian chronicles both the Abas and the Árpáds are identified as descendants of Attila, the grand prince of the Hunnic empire. This would imply that the paternal lineages of the two families are the same. Since the R1a paternal lineage of the Árpáds has been previously identified6,7,8 and it does not match the paternal lineage identified in the Abas, we can now definitively exclude this possibility. Nonetheless, the unverified assertion of either royal lineage being descended from Attila persists. Detailed Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS) data revealed the Árpáds' paternal ancestry originating from East Eurasia,6 with potential Hunnic connections.45 In this study, the Abas also demonstrated Hunnic/Xiongnu phylogenetic connections, rendering both families to be credible candidate for this esteemed genealogy.

The genomic-level analyses align with the uniparental data. Both ADMIXTURE and PCA analyses indicated minor Asian ancestry in the studied medieval individuals. The qpAdm analysis also identified a notable minor East Asian component in the majority of the Abasár genomes; however, due to the low fraction of this component, the program could not pinpoint its precise source. Potential sources include the Huns, Avars, or conquering Hungarians, however, the IBD results propose that the minor Asian component among the previous likely originated from the conquering Hungarians. In summary, all genetic results consistently point toward the Abas being descendants of one of the tribal elites among the conquering Hungarians.

Limitations of the study

The population genetic analysis is limited by the available reference genomes. Furthermore, in addition to their main European component, the examined genomes contained so small minor components (Asian and Caucasian) whose precise identification is not possible with the available methods. The study is based on remains from 19 individuals, which may not be fully representative of the entire Aba family or broader population. Limited sample size can lead to biases or overgeneralization. Radiocarbon dating has inherent uncertainties. Calibration errors or reservoir effect could affect the accuracy of the timelines established for the remains. The East Eurasian genetic patterns found may reflect complex admixture events beyond the scope of Hungarian conquest migrations. The genetic comparison with modern populations or other historical figures might be limited by the availability and quality of contemporary genetic data.

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Gergely I. B. Varga (varga.gergely@mki.gov.hu).

Materials availability

This study did not generate new unique reagents.

Data and code availability

-

•

Aligned sequence data have been deposited at European Nucleotide Archive (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/ena) under accession number ENA: PRJEB72247 and are publicly available as of the date of publication. Accession numbers are listed in the key resources table.

-

•

This paper analyses existing, publicly available data. These accession numbers for the datasets are listed in the key resources table.

-

•

This paper does not report original code.

-

•

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Miklós Kásler for supporting the excavation and the genetic analysis. We owe a debt of gratitude to Imre Küzmös for his help in the yfull phylogenetics. We thank Gelegdorj Eregzen for the sample of the elite Xiongnu individual (AG6F). This research was partially funded by the Competence Center of the Life Sciences Cluster of the Centre of Excellence for Interdisciplinary Research, Development and Innovation of the University of Szeged to T.T., Z.M., and E.N. (the authors are members of the “Ancient and modern human genomics competence center” research group). This research was funded by grants from the National Research, Development and Innovation Office (TUDFO/5157-1/2019-ITM and TKP2020-NKA-23) to E.N. This work was partially supported by ÚNKP-23-4 (grant agreement no. ÚNKP-23-4-SZTE-650) New National Excellence Program of the Ministry for Culture and Innovation from the Source of the National Research, Development and Innovation Fund to B.T.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: G.I.B.V., T.T., and E.N. methodology: G.I.B.V., Z.M., O.S., and T.T. formal analysis: G.I.B.V., Z.M., O.S., and T.T. investigation: G.I.B.V., Z.M., O.S., K.M., E.N., B.T., O.A.V., A.G., B.K., P.K., and M.D. resources: Z.G. and M.M. data curation: Z.M. and E.N. writing—original draft: G.I.B.V. writing—review and Editing: Z.M., O.S., K.M., E.N., B.T., A.G., B.K., Z.G., T.T., J.B.S., M.M., and E.N. visualization: G.I.B.V. and O.S. supervision: G.I.B.V. and E.N. project administration: G.I.B.V. and E.N. funding acquisition: T.T. and E.N.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

STAR★Methods

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Biological samples | ||

| Human archaeological remains | This paper | N/A |

| Critical commercial assays | ||

| MinElute PCR Purification Kit | QIAGEN | Cat No./ID: 28006 |

| Accuprime Pfx Supermix | ThermoFisher Scientific | Cat. No: 12344040 |

| Qubit fluorometric quantification system | ThermoFisher Scientific | Cat. No: Q33231 Cat. No: Q33238 |

| TapeStation 2200 system | Agilent Technologies | G2964AA |

| Deposited data | ||

| Human reference genome NCBI build 37, GRCh37 | Genome Reference Consortium | http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/projects/genome/assembly/grc/human/ |

| Modern comparison dataset | Allen Ancient DNA Resource (Version v42.4)46 |

https://reich.hms.harvard.edu/allen-ancientdna-resource-aadr-downloadable-genotypespresent-day-and-ancient-dna-data |

| Ancient comparison dataset | Allen Ancient DNA Resource (Version v42.4)46 |

https://reich.hms.harvard.edu/allen-ancientdna-resource-aadr-downloadable-genotypespresent-day-and-ancient-dna-data |

| Modern comparison dataset | yfull database | https://www.yfull.com/ |

| Ancient mitochondrial database | Maár et al. 202131 | N/A |

| Newly published ancient genomes | This paper |

https://www.ebi.ac.uk/ena/browser/view/; ENA: PRJEB72247 |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| Illumina specific adapters | Custom synthetized | https://www.sigmaaldrich.com/HU/en/product/sigma/oligo?lang=en®ion=US&gclid=CjwKCAiAgvKQBhBbEiwAaPQw3FDDFnRPc3WV75qapsXvcTxxzBXy48atqyb6Xi5f_8e6Df2EJI0NNhoCmzIQAvD_BwE |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| Cutadapt | Martin et al.47 | https://cutadapt.readthedocs.io/en/stable/# |

| FastQC | Andrews48 | https://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/ |

| Burrow-Wheels-Aligner | Li and Durbin49 | http://bio-bwa.sourceforge.net/ |

| samtools | Li et al.50 | http://www.htslib.org/ |

| PICARD tools | Broad Institute51 | https://github.com/broadinstitute/picard |

| ATLAS software package | Link et al.52 | https://bitbucket.org/wegmannlab/atlas/wiki/Home |

| MapDamage 2.0 | Jónsson et al.53 | https://ginolhac.github.io/mapDamage/ |

| Schmutzi software package | Renaud et al.54 | https://github.com/grenaud/schmutzi |

| ANGSD software package | Korneliussen et al.55 | https://github.com/ANGSD/angsd |

| HaploGrep 2 | Weissensteiner et al.56 | https://haplogrep.i-med.ac.at/category/haplogrep2/ |

| Yleaf software tool | Ralf et al.57 | https://github.com/genid/Yleaf |

| mosdepth software | Pedersen and Quinlan58 | https://github.com/brentp/mosdepth |

| IGV | Thorvaldsdóttir et al.59 | https://igv.org/ |

| smartpca | Patterson et al.60 | https://github.com/chrchang/eigensoft/blob/master/POPGEN/README |

| ADMIXTURE software | Alexander et al.61 | https://dalexander.github.io/admixture/ |

| R 4.1.2 | R core development team62 | https://cran.r-project.org/bin/windows/base/old/4.1.2/ |

| ADMIXTOOLS software package | Patterson et al.63 | https://github.com/DReichLab/AdmixTools |

| READ algorithm | Kuhn et al.64 | https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0195491.s007 |

| correctKin | Nyerki et al.65 | https://pkg.go.dev/github.com/zmaroti/correctKin |

| PLINK | Purcell et al.66 | https://zzz.bwh.harvard.edu/plink/ |

| GLIMPSE2 | Rubinacci et al.67 | https://odelaneau.github.io/GLIMPSE/ |

| ancIBD v.0.5 | Ringbauer et al.68 | https://github.com/hringbauer/ancIBD |

| Python 3.6.8 | Python Software Foundation69 | https://www.python.org/downloads/release/python-368/ |

Experimental model and study participant details

Ancient samples

We present shotgun sequenced genome data of 19 ancient individuals from the Abasár Bolt-tető site, Hungary between the 12th and 17th centuries. All 38 in-door remains from Abasár with available petrous bone, or tooth were undergone genetic sampling (Table S1B).

Archaeological description of Abasár, Bolt-tető site

The Abasár, Bolt-tető archaeological site has been known since 1954, when the construction of a fire station on the previously undeveloped inner-city hilltop in Abasár revealed Árpád-era stone walls and tombs by the researchers of the Eger Museum.70,71 Already at this time, carved column capitals of such quality were unearthed that made it clear that the hilltop is the location of the Benedictine monastery founded by Sámuel Aba in 1042, where eventually the king himself was laid to rest.25,72 During the communist and socialist eras, several buildings were constructed on the hilltop, unfortunately without archaeological excavation or artifact preservation, despite the clear archaeological significance of the area.

In the 1950s, the residence of the president of the Egerszólát Farmer’s Co-operative (922nd lot) was built, followed by the cultural center of the village (958th lot) and Aba Borozó (957th lot) around 1960, all on a 600m2 area. In the '70s, another residential building (953/3rd lot) and a winemaking processing building with three levels below ground (952nd lot) were added. The basement of the president’s residence destroyed one-third of the circular rotunda turned out to be an earlier building than the Benedictine monastery, along with the early cemetery around it. The cultural center and the wine bar caused immeasurable damage to the Benedictine monastery wings, and the other residential building damaged the nave of the monastery church and partially covered it. The winemaking processing building destroyed the cemetery around the church.

In the unbuilt area, archaeological work took place in 1970-71 in connection with the landscaping of the courtyard of the cultural center. At that time, Nagy Árpád uncovered important sections, but due to the early death of the archaeologist and poorly documented excavation, only limited excavation documentation remains, including a three-page excavation report and some detailed drawings stored in the Hungarian National Museum archive from 1971.73,74,75 Based on these, it can be seen or inferred that the circular rotunda’s almost fully excavatable area was uncovered at that time. Nagy also found the eastern, straight-ended sanctuary wall of the Benedictine monastery church, the walls of the side chapel added to the sanctuary from the south, a spiral staircase, and the presumed wall of the western closure of the monastery church. Numerous graves and three carved tomb covers were also found during the excavation, some of which were located in the middle of the side nave next to the sanctuary, near the spiral staircase. Although Nagy Árpád uncovered significant areas and important findings, the lack of documentation and an overall excavation plan means we don’t know exactly where and what he excavated – we can only infer from the current excavation results that he may have excavated in certain areas, but it is certain that he did not dig under the parking lot poured in 1970.

After 1971, the area was landscaped, and despite significant findings, no further archaeological excavations took place. Sámuel Aba’s Benedictine monastery did not receive further attention or financial resources at that time. Local residents were dissatisfied with this situation, and in 2006, forming an association, they excavated the rotunda section that was not destroyed by the construction of the president’s residence.76 This work, involving local volunteers and students from Eger, took place intermittently until 2011 when a temporary roof was placed over the excavated area of approximately 100 m2.77 However, the work did not continue, and the protective roof aged, leading to the deterioration of the exposed ruins.

A year after the establishment of the Institute for Hungarian Research, in the fall of 2020, the dismantling of the protective roof and a more comprehensive, interpretable excavation of the site began at the initiative of the local government in 2019. The work continued at full speed in 2021, and parallel to the excavation, efforts began to conserve the uncovered artifacts. In 2021, the president’s residence on lot 922 was dismantled, and the remaining, partially destroyed parts of the rotunda were excavated. The years 2022–2023 focused on the conservation of the excavated walls and structures, and by the end of 2023, the floor plan reconstruction of the rotunda was completed, along with the preservation and partial reconstruction of the sanctuary and side chapel of the Benedictine monastery church and one room in the eastern wing of the monastery – making part of the excavation area partially accessible to the public.

New archaeological results

During the 2020–2021 excavation, our knowledge expanded significantly, as the previously explored area of 100m2 increased to nearly 1800 m2. The excavation was conducted by Ásatárs Kft. under the archaeological leadership of the Institute for Hungarian Research led by Miklós Makoldi, with the overall leadership of Zsolt Gallina and Gyöngyi Gulyás. The anthropological material recovered from the site underwent genetic analysis at the Archaeogenetic Research Center of the Magyarságkutató Intézet, led by Endre Neparáczki and Gergely Varga. Here are the main results of the excavation.

The rotunda

During the excavation, it became clear that the earliest building on the site is the rotunda, partially destroyed by the President of the Agricultural Cooperative. It is fully oriented from East to West and is surrounded by a cemetery consisting mainly of tombs lined with stone slabs, which were partially overbuilt by the 1042-founded Benedictine monastery – the orientation of the monastery buildings differs (northeast-southwest), indicating that the rotunda predates Sámuel Aba’s constructions. This also suggests that the rotunda is earlier than Sámuel Aba’s constructions, including his tomb. This is supported by the fact that no graves were found inside the rotunda, and the rock surface in the interior was untouched, contradicting the earlier belief that Sámuel Aba was buried here. The dating of the rotunda will likely be determined through isotopic analysis of the early stone-lined graves around it.

The monastery church and the monastery

The most significant discovery in 2020 was the identification of a large, straight-ended sanctuary to the southwest of the circular church. This sanctuary belonged to a late-Romanesque style church, associated with the Benedictine monastery founded by Sámuel Aba in 1042. The excavation revealed three periods of the monastery church, notably the late-Romanesque single-nave church with straight-ended sanctuary (KT2 period), a possible 15th-century floor in the same church (KT3 period), and the original 11th-century remains of a two-towered church with a three-nave, semi-circular sanctuary (KT1 period).

The monastery Church’s first period (KT1)

To the southwest and west of the round rotunda, previously built on the eastern edge of the Bolt Hill rock dome, the Benedictine monastery founded by Sámuel Aba in 1042 was established, intended as the burial place for the king. Originally, the monastery church was built as a three-nave, circular apse, two-towered structure, measuring 10 × 30 m, which was almost completely destroyed during the Mongol invasion. During the archaeological excavation, the outer wall plane of the circular apse, "protruding" to the east from under the straight-ended apse of the 13th-century period (KT2 period), and the protruding foundation plane were clearly identified. The walls of the apse of the KT1 period, which facilitated the calculation of the radius, were found during the excavation. Unfortunately, the apse of the side aisles is either completely covered by the 13th-century masonry (KT2 period) or destroyed by burial pits to the rock surface—hence, deductions can be made regarding the semi-circular apse of the side aisles. Additional clues to the early period are the square cross-sectioned Budakalász limestone column at the northeastern corner of the church, originating from the northern aisle of the KT1 period, which was entirely walled into the northern apse wall of the KT2 period. Similarly, a large Budakalász limestone "in situ" block found at the eastern end of the northern wall of the nave (KT1 period) provides a reference point for the early church’s northeastern corner.

In the apse of the main nave of the KT1 period, the supporting pillar of the 13th-century period altar stone (KT2 period) is centrally located, suggesting that the early period may have had its altar for celebrating Mass. Among the pillars at the intersections of the aisles of the KT1 period, only the foundations of two remain, as the rest were destroyed by later constructions and later burials. However, at the western end of the church, the massive, high foundations of a pair of towers connected from the inside to the western gable wall of the church were clearly visible, indicating robust towers.

The floor level of the KT1 church could only be sporadically identified just above the rock surface. According to the archaeological excavation, the church floor was likely at a single level and may have been covered with stone or terrazzo, although in most places, only the dusty floor indicated this, with remnants of terrazzo plaster remaining in one or two corners.

Sámuel Aba may have been buried in the main nave of the KT1 church, as this was the holiest place in the Benedictine monastery he founded for burial. In the central line of the main nave, there were several rock-cut graves suitable for the royal burial, but without exception, these contained burials from later centuries, according to C-14 dating. Unfortunately, Sámuel Aba’s remains, buried with royal accompaniments, were not found, which is not surprising given that the Mongol devastation almost completely destroyed this church to the floor level, likely disturbing the graves as well. In the geometric center of the KT1 church, a large burial pit was found, with later burials, equipped with 15th-century tomb slabs, indicate, but the size and position of the burial pit could have been suitable for Sámuel Aba’s royal burial place, which unfortunately did not survive due to the Mongol destruction.

A monastery wing was also attached to the KT1 church from the north, the remnants of which were found under the walls of the northern side of the church’s apse during the 13th-century alterations, with the same floor plan as the 13th-century monastery. These monastery remnants only remained 1–2 courses high compared to the original 11th-century floor, which we found under the Gothic floor levels. However, the excavation successfully identified the remains of the monastery belonging to the KT1 period as well. This monastery, too, was likely a square-shaped building complex with an internal courtyard, similar to its counterpart rebuilt in the 13th century. It is important to note that even this early monastery (KT1 period) was built on top of the earlier cemetery, with graves around the earlier rotunda to the east. Therefore, we believe that the rotunda could be much older than the KT1 period. The further exploration of the monastery wings is greatly hindered, of course, by the building of the cultural house, which partly conceals and partly destroys it and is still standing today.

The side chapel attached to the KT1 period church from the east

After the completion of the KT1 period early church and the northern side of its apse, a small side chapel was added from the east, which connected to the sanctuary of the northern side aisle of the KT1 church from the east. It became clear during the archaeological excavation that Nagy Árpád likely already explored the chapel, but between 2006 and 2011, the northern half of the building and the tomb inside were definitely excavated since, at the beginning of the excavation by the Institute of Hungarian Research in 2020, this area was open and exposed under the protective roof.

The small building is divided into a straight-ended "sanctuary" and a small nave, with internal buttress-supported vaulting likely holding a cross vault over the sanctuary. In the middle of the nave, there is a grave, which was either excavated by Nagy Árpád or during the excavations of the early 2000s—hence, the bone material cannot be identified, although the person buried there may have been significant.

The building’s construction history is clearly visible in the results of the 2020-21 excavation. It is evident that the building was added to the semi-circular apses of the KT1 period church, but it is not contemporary with them. The same can be observed at the square-shaped stone at the northeastern corner of the KT1 church, where it is clearly visible that the corner element was added to the chapel wall from the east. However, it is also apparent that the straight-ended apse wall and the northeastern support pillar of the KT2 period monastery church were already built on top of the chapel wall—thus, the building could no longer stand at that time, and the external ground level was higher after the Mongol devastation than the ruined chapel walls.

From all this, it can be inferred that the chapel may have been built sometime in the second half of the 11th century, but the Mongol invasion of 1241 razed it to the ground, and the building was not reconstructed. Instead, the grand KT2 church was erected on top of the ruins, leaving only the part below the external floor level of the KT2 church preserved. Additionally, it is observable that part of the lintel of the chapel’s doorway remains in the western direction—thus, it is certain that the chapel could be accessed through a door created by breaking the apse wall of the northern side aisle of the KT1 church, and its entrance opened from the sanctuary zone of the first-period monastery church. This suggests that the person buried here could be identified with one of the important members of the Aba lineage who died between 1060 and 1240 or possibly with one of the abbots of the monastery. Unfortunately, the bone material recovered from here cannot be identified today due to the lack of documentation.

The second period of the monastery church and monastery (KT2)

The Benedictine monastery founded by Sámuel Aba underwent its first destruction during the Mongol invasion, as it fell within the main route of the Tatar armies heading toward Buda, resulting in the devastation of both the monastery church and the monastery itself. Interestingly, there is no apparent destruction or reconstruction up to a height of 1 m 50 cm on the walls of the rotunda. Of course, the vault and higher walls of the rotunda could have also been destroyed, as the Mongols surely did not spare this building either. However, the destruction was elemental. The KT1 period church and the monastery were almost completely destroyed.

Nevertheless, after the Mongol invasion, the Aba clan embarked on a gigantic construction project. The monastery church underwent significant alterations and was reconstructed, along with the monastery wings. However, the burial chapel connected to the KT1 church from the east was never rebuilt. The walls of the KT1 church were uniformly dismantled up to a height of 50 cm from its internal floor level, and new external and internal floor levels were established, higher than the original.

The KT2 period church evolved into a late Romanesque style, single-nave church with corner pilasters, and the internal dimensions of the sanctuary were 9x18 m. The length of the church could reach up to 30 m, but the complete area is not yet excavated, so the exact data are unknown; however, the width of the nave is 12 m. With these dimensions, the straight-ended pilastered sanctuary, and the large monastery church with divided nave using the western wall of the KT1 church as a dividing wall, the KT2 monastery church shows many parallels in its layout, size, and form with the first period of the Dominican monastery church on Margaret Island, which was built by Béla IV as the monastery and final resting place of his daughter, Saint Margaret. Moreover, later, King István V was also laid to rest in this church.17,78,79 The size, quality, and similarity of the two churches and monasteries indicate that the Aba clan, not prominently featured in historical sources in the 13th century, had financial resources after the Mongol invasion comparable to those of the king, who, due to the country’s escape from the Mongols, built a monastery for his daughter with royal splendor!

The wealth of the Aba clan is also indicated by the painted marble fragment found under the southern side altar of the church sanctuary, depicting the Virgin Mary with the infant Jesus. The quality and beauty of the carving can be compared to the finest late Romanesque to early Gothic European stone carvings, unparalleled in Hungary until now. This stone carving might have been the altarpiece of the XIII. century monastery church (KT2) dedicated to the Virgin Mary, during its reconstruction after the Mongol invasion.

The KT2 period monastery is essentially a completely rebuilt multi-level monastery constructed on the almost ground-level ruins of the KT1 monastery. The monastery has a courtyard with a brick-paved cloister and a well carved into the rock in the center of the courtyard. The floor plan study may still pose many questions, as only the initiation of the eastern wing of the monastery and a part of the monastery courtyard fell into the excavated 1800m2 area, and the well of the monastery courtyard, accessible from the cellar system below the site, was covered during the construction of the cultural house but fortunately not entirely or only partially walled up.

The Gothic chapel connected to the sanctuary of the KT2 church from the south

After the Mongol invasion, a large, solid, multi-level chapel was added to the southern wall of the sanctuary of the KT2 church, built in early Gothic style. The southern corners of this chapel were supported by diagonal, large-area Gothic pillars. The construction of the chapel presumably took place in the 14th century. During the construction of the chapel, they pierced the southern wall of the sanctuary of the KT2 church, making the ground floor of the chapel accessible. In the center of this ground floor, a large burial pit is located, which Árpád Nagy already excavated in 1971.80 Presumably, it was from here that the Gothic tombstone decorated with a 14th-century lace cross, currently inventoried in the Mátra Museum in Gyöngyös in an unidentified state, was unearthed. The carved stone floor chapel must have been two stories high, as the foundation of a stone spiral staircase was found in its southwest corner. Árpád Nagy also mentioned this staircase in his report, describing that a piece of carved staircase element is still in place … Unfortunately, this stone has disappeared over time.

The Gothic two-story burial chapel could have been built for a person of high rank, as it required the disruption of the southern wall of the sanctuary of the KT2 church. The existence of a two-story building indicates a very high prestige. It is assumed that this 14th-century chapel was built for none other than Amádé Aba, one of the most famous members of the Aba clan and a powerful oligarch of the 14th century, possibly before his death. Unfortunately, the identification of the skeletal remains from the ground floor of the chapel seems hopeless due to the lack of documentation.

Perhaps related to the vault of this chapel are two fragments of 14th-century Gothic rib vaults, each with two ribs. These fragments were used to support, or possibly horizontally align, a carved, Aba-coated tombstone with an inscription located north of the main altar of the KT3 church. This repositioning and leveling took place after the Hussite destruction in the second half of the 15th century.

The third period of the monastery church and monastery (KT3)

In the life of the monastery, the second period of destruction and subsequent reconstruction occurs in the 15th century under circumstances that are not exactly clear. In any case, the major openings, especially the doors of the monastery, are replaced with finely carved eyebrowed stone-framed doors, which, in several cases, are substituted for the original 13th-century openings, sometimes altering their size. A good example of this is the doorway leading from the inner courtyard of the monastery to the rotunda, used as a baptistery at the time, where the wide stone threshold is significantly narrowed and fitted with a smaller-sized, fine-arched Gothic stone frame in the 15th century, with the original threshold left in place.

During this time, the interior of the monastery church also receives a new brick covering, laid with 20 × 20 × 5cm Gothic floor tiles.

But what could have been the reason for the 15th-century renovation? Most likely, a serious devastation, as evidenced by several factors within the church and the monastery. The most striking evidence of serious devastation and the accompanying massacre is found in the upper layers of the 15th-century carved stone-covered graves in the sanctuary of the KT2 church. Masses of scattered human bones are discovered, and often partial human remains are found in anatomical order, indicating that after the construction of the graves, a complete destruction ensued on the monastery grounds. It seems that everyone was slaughtered to such an extent that there was no one left to bury the dead. The corpses could have lain unburied for months, partially disintegrated by wild animals. Later, those returning to the monastery threw these human remains into the graves with hinged stone covers, in some cases as scattered bone remains, and in other cases, the remains of bodies somewhat preserved in anatomical order.

Such devastation in the 15th century could have only been carried out by the Hussites who repeatedly invaded the area and caused significant damage to the fortress in Kisnána. Aba’s relative, Péter Kompolti, already falls in battle against the Hussites in 1420.71,81,82 The incursions likely continued until the time of King Matthias.83 It is probable that the benedictine monastery in Abasár was destroyed in this period and was probably rebuilt during the era of the Hunyadis, where renovations took place, such as the retiling of the monastery church with bricks or the replacement of door openings in the monastery wings with Gothic stone-framed openings.

An indication of the use of Gothic door frames on the upper floor of the monastery is an uncovered, scorched door frame among burned wooden beams in the northern wing of the monastery. This suggests that there might have been Gothic door frames on the upper floor of the monastery since, in the vicinity of the fallen frame on the ground floor, has no wall opening.

It is evident that the Aba clan still had significant financial resources in the 15th century to rebuild the church and monastery, incorporating openings that matched the style of the time. This is not surprising, given that the Nánai branch of the Abas, who were probably donors to the monastery at this time, are frequently mentioned in royal positions in contemporary sources.71,81,82

The destruction of the monastery

After the 15th century, there is scarce historical information about the life of the monastery or the Nánai Kompolti family who owned it. However, archaeological findings indicate that life in the complex did not cease. According to numismatic evidence, the monastery was used until the 1630s when, in all likelihood, a Turkish invasion put an end to its existence.

What is certain is that the devastation during the Turkish era involved intense fires, and even the Gothic door frames were found severely burnt and collapsed on-site. After the Mongol and Hussite devastations, the church and monastery were rebuilt, but they succumbed to the Turkish invasion. The area remained uninhabited and undeveloped until the 20th century. The ruins were likely visible until the 19th or early 20th century.

In the 17th century, traces suggesting bronze casting and blacksmith activities were found among the ruins. Subsequently, there were wine-making developments and constructions associated with the active use of the underground cellar system beneath the ruins. Large wine cellars and pressing houses were built in the field of the ruins.

However, the development and destruction of the site only began in the mid-20th century with the construction of József Dér’s house, followed by the main building of the cultural center. These constructions and subsequent gradual urbanization posed significant challenges in excavating, interpreting, and presenting the ruins.

Archaeological description of the studied burials

During the excavation at Abasár Bolt-tető site, more than 300 burials were uncovered within and outside of the gothic church building (Object 7). As the indoor graves potentially harbor aristocratic individuals’ skeletons, we took those into archaeogenetic investigation to identify the potential Aba clan members. Below we present the archaeological description of the studied indoor burials. Since various construction phases of the temple were identified during the excavation, the archaeological phenomena uncovered in each layer were separated with stratigraphic numbers (Snr). We start with the description of the most important burials, whose findings were genetically characterized in the main text.

-

(1)

The prominent burial in the sanctuary with the carved and scripted cover stone, labeled with blue quadrate in Figure 1. This includes Snr 8, Snr 57 and Snr 58/1–2.

-

(2)

The two graves in the sanctuary labeled with yellow quadrate in Figure 1. This includes Snr 55/a-b and Snr 59/a-b.

-

(3)

The double grave in the geometrical center of the church labeled with green quadrate in Figure 1. This includes Snr 194/a-d, Snr 261 and Snr 262.

-

(4)

All other graves within the temple. These include Snr 200, Snr 201, Snr 309, Snr 310, Snr 311/a-b, Snr 316, Snr 341, Snr 390, Snr 401, Snr 445, and Snr 450.

Snr 8

Archaeological dating: 15th century CE

Burial with a tombstone in the temple (Figure 7), toward the east from the stone stairway and toward the northwest from the altar foundation. At the northeast end, a brick floor is observed. In the northwest section, there is a stone frame (straight-moulded, Gothic vault), squared stones to the southwest, a larger stone slab to the southeast, supported by squared stones, likely added later. The cover stone is 190 cm long, 100 cm wide, and 25 cm thick. The original cover stone displayed the crest of the Aba clan and a presumably readable Gothic minuscule inscription in a circular pattern: 'In the year of the Lord MCCC?, here rest János and … … … …. sons: Mihály and János.' Unfortunately, the last numeral of date inscribed with Latin numbers was damaged and could not be decode, thus, the date can be equivalently translated as 1401 or 1405 or 1450. Based on the year and names, we can likely assume these are the sons of János, who was a member of the Aba clan.

Figure 7.

The cover stone of the grave Snr 8

The cover stone was lifted with a machine, revealing a layer of 50 cm thick stone rubble underneath. From the level of appearance, down to a depth of 60–70 cm, five jumbled human skulls lay next to the northwest wall. Unfortunately, the bones in the grave were disturbed, but at the bottom of the grave, we found two relatively intact skeletons in anatomical positions (Snr 56, Snr 57). As these two remains could be unambiguously regarded as primary burials, based on the preliminary archaeological data it is assumable that they were Mihály and János. Above these skeletons, however, we found the mixed bones of more than a dozen individuals and a few anatomically ordered body parts, suggesting that these bones may be the remains of untended dead collected after some larger massacre or the exhumed bones of earlier burials (perhaps relatives of the Kompolti branch brought here during the devastation of the Kisnána Castle in the Hussite attack of 1470?). After extracting the Snr 57 skeleton, we found human remains likely placed in a chest or coffin at the same time and then buried (Snr 58). Under Snr 58, the stone floor of the burial chamber, breaking in the middle, began to deepen in a square area of approximately 90 x 110 cm. Here, at a depth of about 140 cm, we found human bones throughout the depression. The depression may be an early ossuary (Snr 60), possibly contemporaneous with the early period of the temple, containing the scattered bones of several dozen individuals – along with a fragment of spiral-lined early Árpádian pottery.

From the grave, iron nails, a glass bead, a coin, an 'L'-shaped right-angled iron clasp, round stained glass(?) inserts, and glass melts were unearthed. Fabric remnants were found in the southwest corner of the grave. In the south section, many iron nails, 'L'-shaped iron clasp with round lead inserts, marble pieces, and glass melts were found. From the filling of the grave, a coin from the western corner emitted by Matthias (1463) also emerged. Carved stone finding: Gothic arch – vaulting element.

Sampled remains from the Snr8: HUAS81, HUAS82, HUAS83, HUAS84, HUAS85, HUAS86, HUAS87, HUAS88, HUAS89 and HUAS57F.

Snr 57

As indicated above, this is a sub-feature of Snr 8, with archaeological dating: 15-16th century CE

In the grave marked Snr 8 (on its north side), bones were found approximately 90 cm deep from the level of the grave’s appearance. Adjacent to it was the skeleton marked Snr 56 (Figure 8). Beneath it, bones belonging to several individuals from Snr 58 were uncovered (HUAS58.1 and HUAS58.2). The burial of the individual in Snr 57 (HUAS57) was lying on its back in an extended position. Only a small piece of the skull remained, with the left forearm bones missing. The right lower leg was positioned among the femurs of Snr 56. The bones of the upper body were disturbed. Orientation of Snr 57 (HUAS57): Southwest to Northeast. No grave goods were present. As it was already mentioned in the description of Snr 8: it is conceivable that at the bottom of the grave, two relatively intact skeletons lying in anatomical positions can be identified as János’s sons, Mihály and János. One of them, marked Snr 56 was not sampled, because of the lack of skull.

Figure 8.

The skeletons of Snr 56 (left) and Snr 57 (right)

Snr 58/1-2

Archaeological dating: 15-16th century CE. Graves or ossuary

In the temple, in the grave marked Snr 8 (on its north side), various skeletal parts belonging to multiple individuals were uncovered beneath the Snr 57 skeleton. These skeletal parts were contiguous but not in anatomical order. Since the bones appeared on a regular rectangular surface, it is conceivable that they were gathered in a coffin and placed in the pit (Figure 9). Several femurs (belonging to at least 3 individuals), forearm bones, pelvic bones, sacral bones, and smaller bones (vertebrae, ribs) can be mentioned. Studied samples: HUAS581 and HUAS582.

Figure 9.

The skeletons of Snr 58

Snr 55/a-b

Archaeological dating: 15-16th century CE

In the temple, a rectangular grave Snr 55 appeared at the corner of the walls. Parallel to it, toward the northwest, lay the burial marked Snr 59 (Figure 10). During the excavation of the grave, the brick floor and the mortar layer underneath were damaged. The appearance level of the grave was sunken, and around it, the mortar layer in which the former brick floor was embedded is clearly visible. Irregular rounded stones were found in the middle and northeast part of the grave. The Snr 55 grave extended into the bottom of the later church.

Figure 10.

The burials Snr 55 (left) and Snr 59 (right)

The burial chamber of Snr 55, constructed with smaller and larger stones in five rows, was revealed. Its bottom was 85–90 cm below the appearance level. The grave pit was a regular rectangle, with steep walls, and the bottom was on the raw rock surface. In the grave, the well-preserved skeleton (HUAS55A) of an adult individual lying on its back in an extended position was found. The skeleton was preserved up to the knees; the lower legs were missing, likely removed during later disturbance. The burial was evident in the eastern wall of the grave. It was a coffin burial, with the coffin visible 50 cm below the appearance level of the grave. Measured dimensions: height 120 cm (up to the knees), shoulder width 37 cm. The facial part of the skull of the Snr 55/a skeleton was damaged, both arms were extended. The left forearm was placed on the left pelvis, and the right forearm on the outer side of the right pelvis. On the left side of the skull and the shoulder area, one of the femurs of the Snr 55/b skeleton was found. Orientation of Snr 55a Southwest to Northeast.

On the deceased’s skull and behind it, at the western end of the grave pit, about 10–15 cm higher, human bones belonging to a separate individual Snr 55/b (HUAS55B) were gathered. Among them: a skull, pelvic bones, lower legs, clavicle.

Finds: Árpád-era coin, iron elements of the coffin, more than 10 iron coffin nails, a large quantity of 14-16th-century ceramics, few animal bones. During the excavation, a gilded bronze object was also uncovered, which could be a shepherd’s staff or, more likely, the decorated lower part of a goblet. The four protruding, round-shaped parts were decorated with enamel, presumably showing the four apostles. Sampled remains: HUAS55A, HUAS55B.

Snr 59/a-b

Archaeological dating: 14-15th century CE