Abstract

Background

Adverse drug events, encompassing both adverse drug reactions and medication errors, pose a significant threat to health, leading to illness and, in severe cases, death. Timely and voluntary reporting of adverse drug events by healthcare professionals plays a crucial role in mitigating the morbidity and mortality linked to unexpected reactions and improper medication usage.

Objectives

To assess the effectiveness of different interventions aimed at healthcare professionals to improve the reporting of adverse drug events.

Search methods

We searched CENTRAL, Embase, MEDLINE and several other electronic databases and trials registers, including ClinicalTrials.gov and WHO ICTRP, from inception until 14 October 2022. We also screened reference lists in the included studies and relevant systematic reviews.

Selection criteria

We included randomised trials, non‐randomised controlled studies, controlled before‐after studies, interrupted time series studies (ITS) and repeated measures studies, assessing the effect of any intervention aimed at healthcare professionals and designed to increase adverse drug event reporting. Eligible comparators were healthcare professionals' usual reporting practice or a different intervention or interventions designed to improve adverse drug event reporting rate. We excluded studies of interventions targeted at adverse event reporting following immunisation. Our primary outcome measures were the total number of adverse drug event reports (including both adverse drug reaction reports and medication error reports) and the number of false adverse drug event reports (encompassing both adverse drug reaction reports and medication error reports) submitted by healthcare professionals. Secondary outcomes were the number of serious, high‐causality, unexpected or previously unknown, and new drug‐related adverse drug event reports submitted by healthcare professionals. We used GRADE to assess the certainty of evidence.

Data collection and analysis

We followed standard methods recommended by Cochrane and the Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC) Group. We extracted and reanalysed ITS study data and imputed treatment effect estimates (including standard errors or confidence intervals) for the randomised studies.

Main results

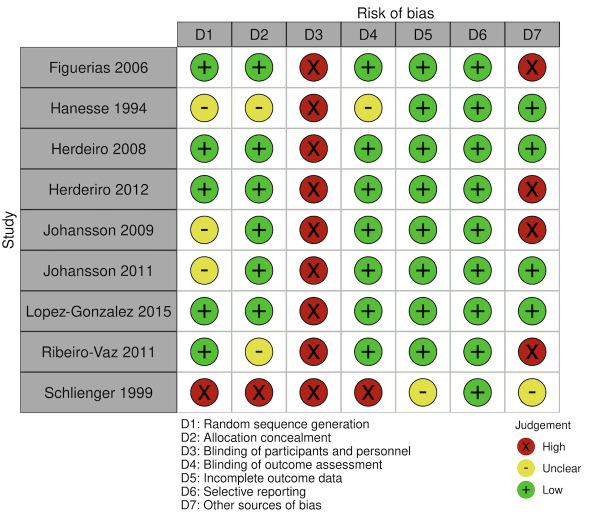

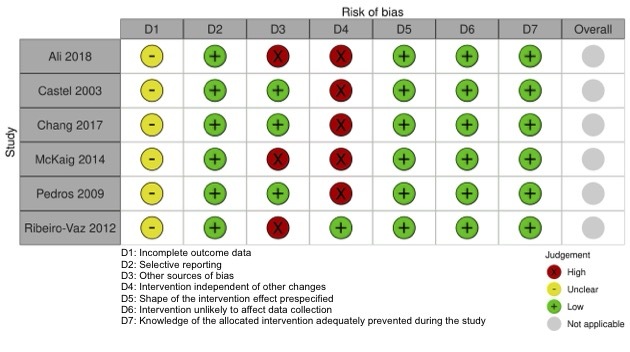

We included 15 studies (eight RCTs, six ITS, and one non‐randomised cross‐over study) with approximately 62,389 participants. All studies were conducted in high‐income countries in large tertiary care hospitals. There was a high risk of performance bias in the controlled studies due to the nature of the interventions. None of the ITS studies had a control arm, so we could not be sure of the detected effects being independent of other changes. None of the studies reported on the number of false adverse drug event reports submitted.

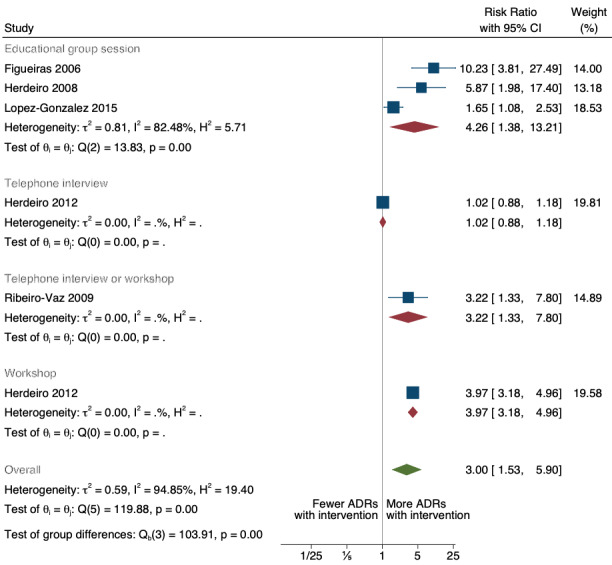

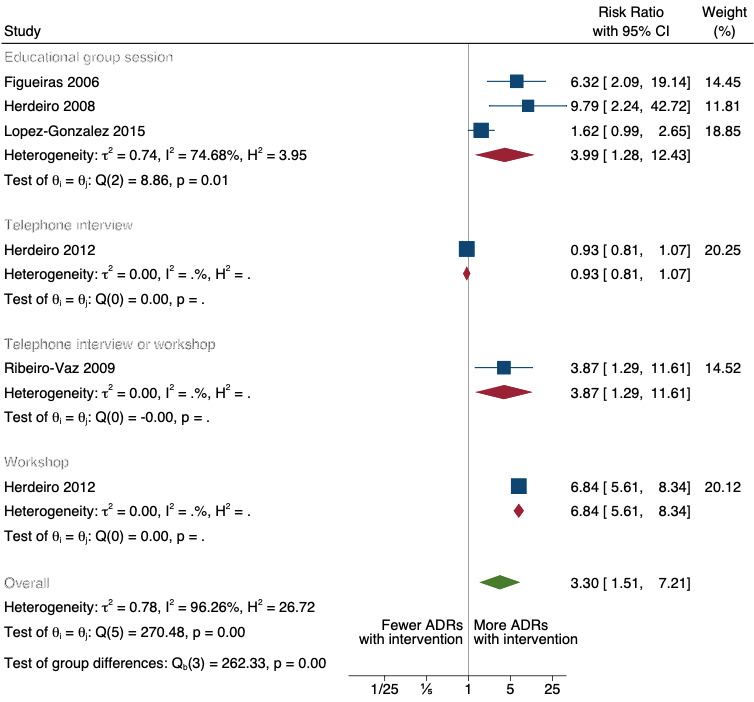

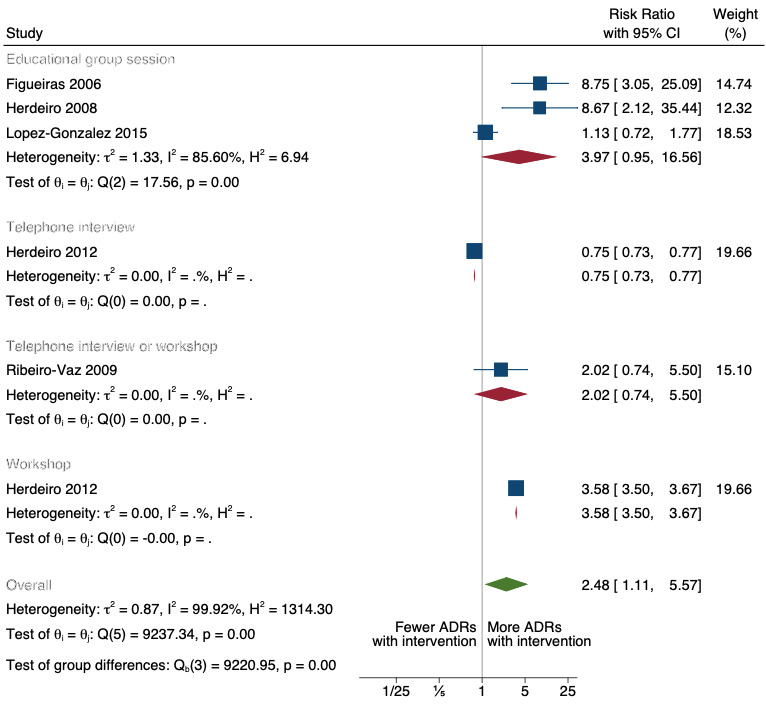

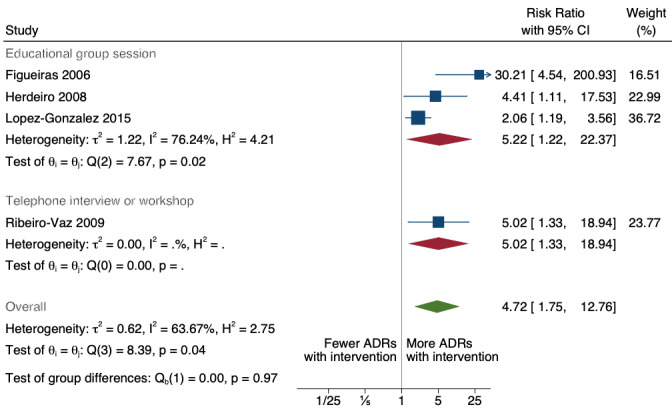

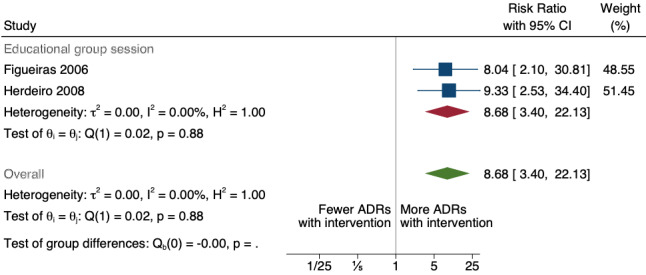

There is low‐certainty evidence suggesting that an education session, together with reminder card and adverse drug reaction (ADR) report form, may substantially improve the rate of ADR reporting by healthcare professionals when compared to usual practice (i.e. spontaneous reporting with or without some training provided by regional pharmacosurveillance units). These educational interventions increased the number of ADR reports in total (RR 3.00, 95% CI 1.53 to 5.90; 5 studies, 21,655 participants), serious ADR reports (RR 3.30, 95% CI 1.51 to 7.21; 5 studies, 21,655 participants), high‐causality ADR reports (RR 2.48, 95% CI 1.11 to 5.57; 5 studies, 21,655 participants), unexpected ADR reports (RR 4.72, 95% CI 1.75 to 12.76; 4 studies, 15,085 participants) and new drug‐related ADR reports (RR 8.68, 95% CI 3.40 to 22.13; 2 studies, 7884 participants).

Additionally, low‐certainty evidence suggests that, compared to usual practice (i.e. spontaneous reporting), making it easier to report ADRs by using a standardised discharge form with added ADR items may slightly improve the total number of ADR reports submitted (RR 2.06, 95% CI 1.11 to 3.83; 1 study, 5967 participants). The discharge form tested was based on the ‘Diagnosis Related Groups’ (DRG) system for recording patient diagnoses, and the medical and surgical procedures received during their hospital stay.

Due to very low‐certainty evidence, we do not know if the following interventions have any effect on the total number of adverse drug event reports (including both ADR and ME reports) submitted by healthcare professionals:

‐ sending informational letters or emails to GPs and nurses;

‐ multifaceted interventions, including financial and non‐financial incentives, fines, education and reminder cards;

‐ implementing government regulations together with financial incentives;

‐ including ADR report forms in quarterly bulletins and prescription pads;

‐ providing a hyperlink to the reporting form in hospitals' electronic patient records;

‐ improving the reporting method by re‐engineering a web‐based electronic error reporting system;

‐ the presence of a clinical pharmacist in a hospital setting actively identifying adverse drug events and advocating for the identification and reporting of adverse drug events.

Authors' conclusions

Compared to usual practice (i.e. spontaneous reporting with or without some training from regional pharmacosurveillance units), low‐certainty evidence suggests that the number of ADR reports submitted may substantially increase following an education session, paired with reminder card and ADR report form, and may slightly increase with the use of a standardised discharge form method that makes it easier for healthcare professionals to report ADRs.

The evidence for other interventions identified in this review, such as informational letters or emails and financial incentives, is uncertain.

Future studies need to assess the benefits (increase in the number of adverse drug event reports) and harms (increase in the number of false adverse drug event reports) of any intervention designed to improve healthcare professionals' reporting of adverse drug events. Interventions to increase the number of submitted adverse drug event reports that are suitable for use in low‐ and middle‐income countries should be developed and rigorously evaluated.

Keywords: Humans, Adverse Drug Reaction Reporting Systems, Adverse Drug Reaction Reporting Systems/statistics & numerical data, Bias, Controlled Before-After Studies, Drug-Related Side Effects and Adverse Reactions, Health Personnel, Interrupted Time Series Analysis, Medication Errors, Medication Errors/prevention & control, Medication Errors/statistics & numerical data, Non-Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic, Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic

Plain language summary

Improving healthcare professionals' reporting of adverse drug reactions and medication errors

Key messages

‐ Healthcare professionals have a responsibility to report unexpected and harmful responses to medicines. These responses are known as 'adverse drug events', a term that includes both adverse drug reactions (ADRs) and medication errors (MEs).

‐ An education session (outreach, in‐person workshops or via telephone), along with providing a reminder card and ADR report form, may substantially increase the number of ADR reports submitted.

‐ Using a standardised discharge form with additional ADR items that is designed to make it easier to report ADRs may slightly increase the number of ADR reports submitted.

‐ Future studies need to assess the benefit (increase in the number of adverse drug event reports submitted) and harm (increase in the number of false adverse drug event reports submitted) of any intervention designed to improve healthcase professionals' reporting of adverse drug events.

‐ Interventions suitable for use in low‐ and middle‐income countries need to be developed and rigorously evaluated.

What did we want to find out?

This Cochrane review investigated whether interventions for healthcare professionals are effective for improving at their reporting of adverse drug events. Adverse drug events include any adverse drug reaction (ADR) and any medication error (ME).

What did we do?

We looked at evidence from a range of different types of studies to find out if interventions aimed at healthcare professionals could increase the number of adverse drug event reports they make. We compared the total number of adverse drug event reports (which included both ADR and ME reports) submitted by healthcare professionals. We were also interested in the number of false adverse drug event reports they made. As well as the total number of reports, we looked separately at the number of reports submitted for adverse drug events that were categorised as serious, high‐causality (i.e. very likely to be caused by the drug), unexpected (i.e. previously unknown) or related to recent drugs (i.e. only used in the last five years).

What did we find?

This review included 15 studies (62,389 participants) that compared the effect of various interventions aimed at healthcare professionals to increase the number of adverse drug event reports they make. All the studies were carried out in high‐income countries. None of the studies looked at whether these interventions led to more false adverse drug event reports.

Compared to usual practice (spontaneous reporting and some training from regional units that monitor the safety of medicines), an education session about why and how to report adverse events, plus reminder of the session content and provision of an ADR report form, may increase the number of ADR reports made by healthcare professionals.

Compared to usual practice (spontaneous reporting), using a standardised discharge form with additional ADR items about when the ADR occurred and how it developed may also slightly improve the number of ADR reports made. The standardised form tested was based on the ‘Diagnosis Related Groups’ system for recording patient diagnoses and the medical and surgical procedures patients receive during their hospital stay.

We are very uncertain about the effectiveness of other interventions that were tested in the studies, including:

‐ sending informational letters or emails to GPs and nurses;

‐ interventions with multiple aspects, including financial and non‐financial incentives, fines, education and reminder cards;

‐ implementing government regulations together with financial incentives;

‐ including ADR report forms in quarterly bulletins and prescription pads;

‐ providing a hyperlink to the reporting form in hospitals' electronic patient records;

‐ improving the reporting method by re‐engineering the web‐based electronic error reporting system;

‐ the presence of a clinical pharmacist in hospital who actively identifies adverse drug events and encourages the identification and reporting of adverse drug events.

How up to date is this review?

The evidence in this review is based on searches up to October 2022.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings 1. Education session plus reminder card and ADR report form versus usual practice.

|

Participants: physicians and pharmacists Intervention: education session (in‐person workshop or via telephone), reminder card and ADR report form Comparator: usual practice (spontaneous reporting; briefing and standard training given by regional pharmacosurveillance unit) Setting: hospitals and outpatient centres in Northern Portugal and Spain | ||||||

| Outcomes |

Risk ratio* (95% CI) |

Illustrative comparative risks‡ (95% CI) |

Number of participants (studies) |

Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) |

Comments | |

| Assumed risk with usual practice | Corresponding risk with education session plus reminder card and report form | |||||

| Total number of ADE reports (including ADR reports and ME reports): number of ADR reports Follow‐up: 13 to 16 months |

3.00 (1.53 to 5.90) | 80 ADR reports per 1000 practitioner years | 240 ADR reports per 1000 practitioner years (122 to 472) | 21,665 (5 cRCTs)1 | Low4 | An education session, together with reminder card and ADR report form, may improve the reporting rate of ADRs. |

| Total number of false ADE reports (including false ADR reports and false ME reports) | None of the included studies reported on this outcome. | |||||

| Number of serious ADE reports (including serious ADR reports and serious ME reports) Follow‐up: 13 to 16 months |

3.30 (1.51 to 7.21) | 10 ADR reports per 1000 practitioner years | 33 ADR reports per 1000 practitioner years (15 to 72) | 21,665 (5 cRCTs)1 | Low5 | An education session, together with reminder card and ADR report form, may improve the reporting rate of serious ADRs. |

| Number of high‐causality ADE reports (including high‐causality ADR reports and high‐causality ME reports) Follow‐up: 13 to 16 months |

2.48 (1.11 to 5.57) | 20 ADR reports per 1000 practitioner years | 50 ADR reports per 1000 practitioner years (22 to 111) | 21,665 (5 cRCTs)1 | Low6 | An education session, together with reminder card and ADR report form, may improve the reporting rate of high‐causality ADRs. |

| Number of unexpected ADE reports (including unexpected ADR reports and unexpected ME reports) Follow‐up: 13 to 16 months |

4.72 (1.75 to 12.76) | 20 ADR reports per 1000 practitioner years | 94 ADR reports per 1000 practitioner years (35 to 255) | 15,085 (4 cRCTs)2 | Low7 | An education session, together with reminder card and ADR report form, may improve the reporting rate of unexpected ADRs |

| Number of new‐drug‐related ADE reports (including drug‐related ADR reports and drug‐related ME reports) Follow‐up: 13 to 16 months |

8.68 (3.40 to 22.13) | 5 ADR reports per 1000 practitioner years | 43 ADR reports per 1000 practitioner years (17 to 111) | 7884 (2 cRCTs)3 | Low8 | An education session, together with reminder card and ADR report form, may improve the reporting rate of new‐drug‐related ADRs. |

ADE: adverse drug event; ADR: adverse drug reaction; CI: confidence interval; cRCT: cluster‐randomised controlled trial; ME: medication error; vs: versus

*Risk ratios > 1 are associated with more ADRs with education session plus reminder card and ADR report form versus usual practice.

‡Illustrative comparative risks are presented as numbers of ADRs per 1000 practitioner years and are rounded to whole numbers.

1Figueiras 2006 (physicians, education group session); Herdeiro 2008 (pharmacists, education group session); Herdeiro 2012 (physicians; same intervention clusters from Herdeiro 2008 randomised a second time to telephone interview or workshop); Lopez‐Gonzalez 2015 (physicians, education group session); Ribeiro‐Vaz 2011 (pharmacists, telephone interview or workshop)

2Figueiras 2006 (physicians); Herdeiro 2008 (pharmacists); Lopez‐Gonzalez 2015 (physicians); Ribeiro‐Vaz 2011 (pharmacists)

3Figueiras 2006; Herdeiro 2008

4Downgraded once for serious risk of bias (performance bias and potential selection bias due to baseline differences in reporting rates between intervention and control group; see Figueiras 2006; Herdeiro 2012; Ribeiro‐Vaz 2011); downgraded once for serious inconsistency: I2 = 95%. The inconsistency might be explained by the mode of delivery of the education (i.e. telephone vs interactive group session vs workshop) or the different target audience (physicians vs pharmacist), but we are uncertain of this; no serious imprecision; no serious indirectness; no publication bias.

5Downgraded once for serious risk of bias (performance bias and potential selection bias due to baseline differences in reporting rates between intervention and control group; see Figueiras 2006; Herdeiro 2012; Ribeiro‐Vaz 2011); downgraded once for serious inconsistency: I2 = 96%. The inconsistency might be explained by the mode of delivery of the education (i.e. telephone vs interactive group session vs workshop) or the different target audience (physicians vs. pharmacist), or both, but we are uncertain of this; no serious imprecision; no serious indirectness; no publication bias.

6Downgraded once for serious risk of bias (performance bias and potential selection bias due to baseline differences in reporting rates between intervention and control group; see Figueiras 2006; Herdeiro 2012; Ribeiro‐Vaz 2011); downgraded once for serious inconsistency: I2 = 100%. The inconsistency might be explained by the mode of delivery of the educational outreach (i.e. telephone vs interactive group session vs workshop) or the different target audience (physicians vs pharmacist), but we are uncertain of this; no serious imprecision; no serious indirectness; no publication bias.

7Downgraded once for serious risk of bias (performance bias and potential selection bias due to baseline differences in reporting rates between intervention and control group; see Figueiras 2006; Ribeiro‐Vaz 2011); downgraded once for serious inconsistency: I2 = 64%. The inconsistency might be explained by the mode of delivery of the education (i.e. telephone vs interactive group session vs workshop) or the different target audience (physicians vs pharmacist), but we are uncertain of this; no serious imprecision; no serious indirectness; no publication bias.

8Downgraded once for serious risk of performance bias and potential selection bias due to baseline differences in reporting rates between intervention and control group (see Figueiras 2006); no serious inconsistency; downgraded once for serious imprecision (wide confidence intervals so uncertain of the true estimate of effect); no serious indirectness; no publication bias

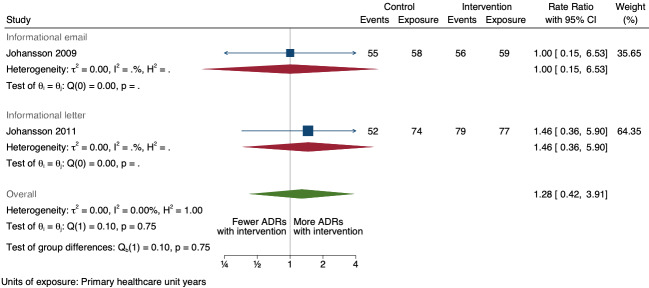

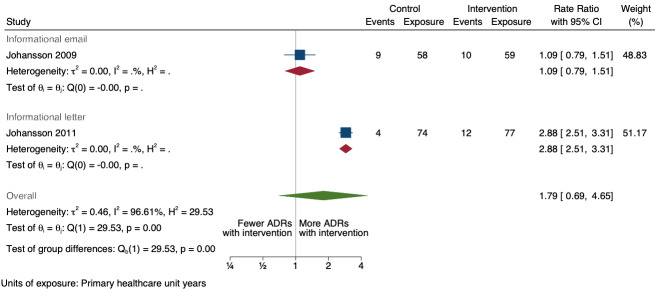

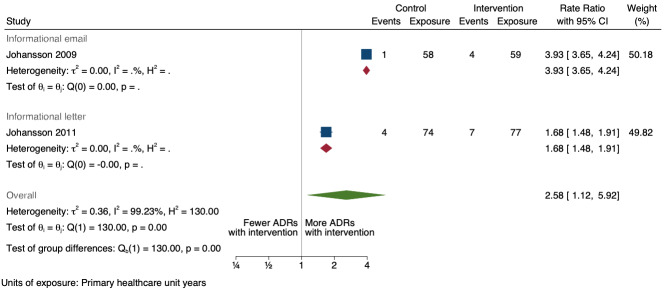

Summary of findings 2. Informational letter or email versus usual practice.

|

Participants: general practitioners and nurses Intervention: informational letter or email Comparator: usual practice (spontaneous reporting) Setting: primary healthcare units in Sweden | ||||||

| Outcomes | Rate ratio* (95% CI) | Illustrative comparative rates‡(95% CI) | Exposure†(studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed rate with usual practice | Corresponding rate with informational letter or email | |||||

| Total number of ADE reports (including ADR reports and ME reports): number of ADR reports after one year | 1.28 (0.42 to 3.91) | 80 ADR reports per 100 practitioner years | 102 ADR reports per 100 practitioner years (34 to 313) | 268 primary healthcare unit years (2 RCTs)1 | Very low2 | We do not know if informational letters or emails to GPs and nurses increase the total number of ADR reports because the evidence is very uncertain. |

| Total number of false ADE reports (including false ADR reports and false ME reports) | None of the included studies reported on this outcome. | |||||

| Number of serious ADE reports (including serious ADR reports and serious ME reports): number of serious ADR reports after one year | 1.79 (0.69 to 4.65) | 10 ADR reports per 100 practitioner years | 18 ADR reports per 100 practitioner years (7 to 47) | 268 primary healthcare unit years (2 RCTs)1 | Very low2 | We do not know if informational letters or emails to GPs and nurses increase serious ADR reports because the evidence is very uncertain. |

| Number of high‐causality ADE reports (including high‐causality ADR reports and high‐causality ME reports) | None of the included studies reported on this outcome. | |||||

| Number of unexpected ADE reports (including unexpected ADR reports and unexpected ME reports): number of unexpected ADR reports after one year | 1.46 (0.92 to 2.30) | 20 ADR reports per 100 practitioner years | 29 ADR reports per 100 practitioner years (18 to 46) | 268 primary healthcare unit years (2 RCTs)1 | Very low2 | We do not know if informational letters or emails to GPs and nurses increase the number of unexpected ADR reports as the certainty of the evidence is very low. |

| Number of new drug‐related ADE reports (including drug‐related ADR reports and drug‐related ME reports): number of new drug‐related ADR reports after one year | 2.58 (1.12 to 5.92) | 5 ADR reports per 100 practitioner years | 13 ADR reports per 100 practitioner years (6 to 30) | 268 primary healthcare unit years (2 RCTs)1 | Very low3 | We do not know if informational letters or emails to GPs and nurses increase the total number of new drug‐related ADR reports because the evidence is very uncertain. |

ADE: adverse drug event; ADR: adverse drug reaction; CI: confidence interval; RCT: randomised controlled trials; ME: medication error; vs: versus

*Rate ratios > 1 are associated with more ADRs with informational letter or email versus usual practice.

†Unit of exposure is primary healthcare unit years.

‡Illustrative comparative rates are presented as numbers of ADR reports per 100 practitioner years and are rounded to whole numbers.

1Johansson 2009; Johansson 2011

2Downgraded once for serious risk of bias (performance bias and potential contamination bias); no serious inconsistency; downgraded twice for very serious imprecision: wide confidence intervals that cross the line of no effect (in the case of total number of ADR reports, number of serious ADR reports and number of unexpected ADR reports), small event rate (total of 242 ADR reports from 268 units in 2007 and 2008, total of 35 serious ADR reports from 268 units in 2007 and 2008, total of 85 unexpected ADR reports from 268 units in 2007 and 2008); no serious indirectness; no publication bias

3Downgraded once for serious risk of bias (performance bias and potential contamination bias); no serious inconsistency; downgraded twice for very serious imprecision: wide confidence intervals, small event rate (total of 16 new drug‐related ADRs reported from 268 units in 2007 and 2008); no serious indirectness; no publication bias

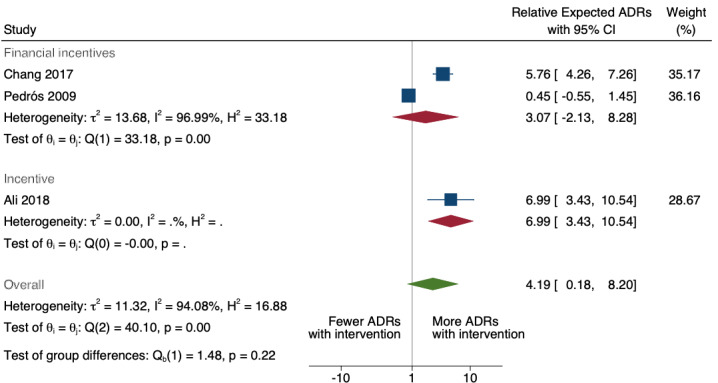

Summary of findings 3. Multifaceted interventions versus usual practice.

|

Participants: physicians and pharmacists Intervention: multifaceted intervention (including financial incentives, fines, non‐financial incentives, education, reminders) Comparator: usual practice (spontaneous reporting) Setting: hospital | ||||||

| Outcome | Relative numbers of ADES* (95% CI) | Illustrative comparative numbers of ADEs‡(95% CI) | Mean study duration (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed number with usual practice | Corresponding number with multifaceted intervention | |||||

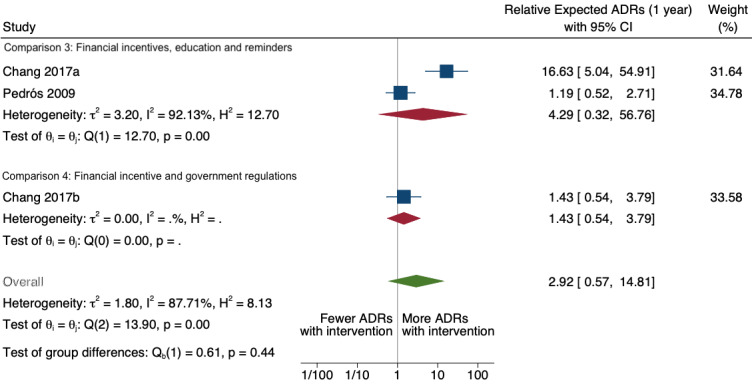

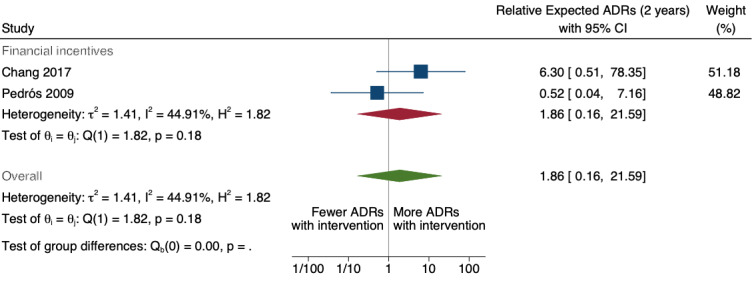

| Total number of ADE reports (including ADR reports and ME reports): number of ADR reports after one year | 4.29 (0.32 to 56.76) | 80 ADR reports per 1000 practitioners | 343 ADR reports per 1000 practitioners (26 to 4541) | 6.5 years (2)1 | Very low2 | We do not know if multifaceted interventions increase the total number of ADR reports in physicians and pharmacists one year after implementation because the evidence is very uncertain.3 Data after two years in footnotes4 |

| Total number of false ADE reports (including false ADR reports and false ME reports) | None of the included studies reported on this outcome. | |||||

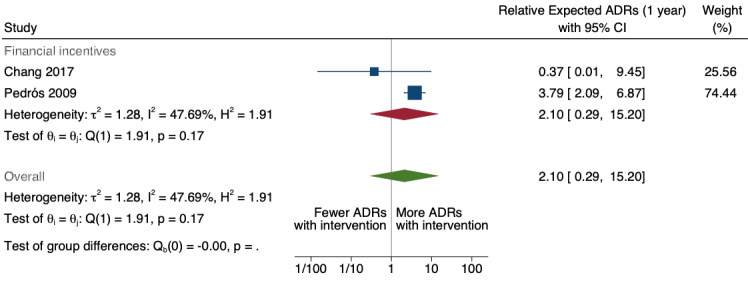

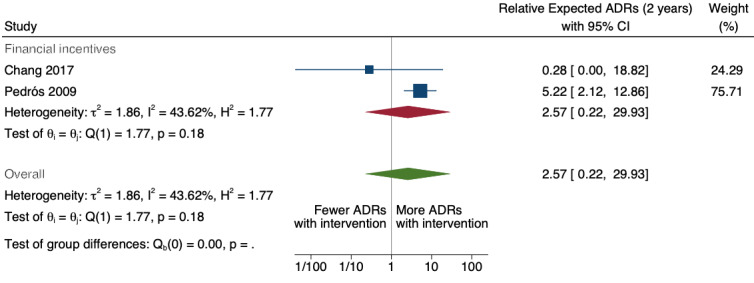

| Number of serious ADE reports (including serious ADR reports and serious ME reports): number of serious ADR reports after one year | 2.10 (0.29 to 15.20) | 10 ADR reports per 1000 practitioners | 21 ADR reports per 1000 practitioners (3 to 150) | 6.5 years (2)1 | Very low2 | We do not know if multifaceted interventions increase the total number of serious ADR reports in physicians and pharmacists one year after implementation because the evidence is very uncertain. Data after two years in footnotes5 |

| Number of high‐causality ADE reports (including high‐causality ADR reports and high‐causality ME reports) | None of the included studies reported on this outcome. | |||||

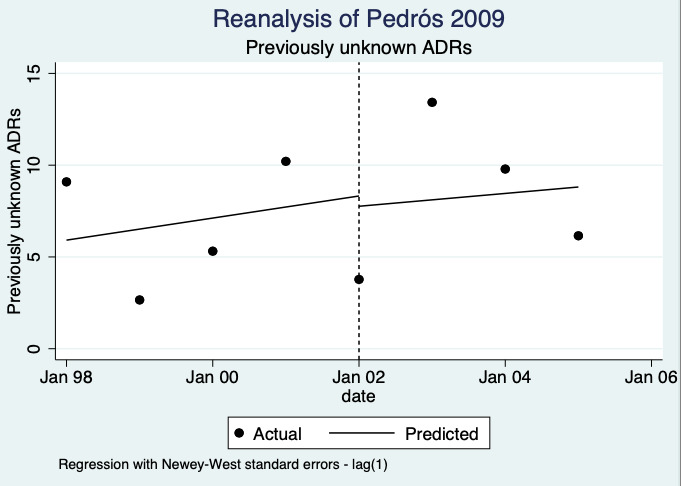

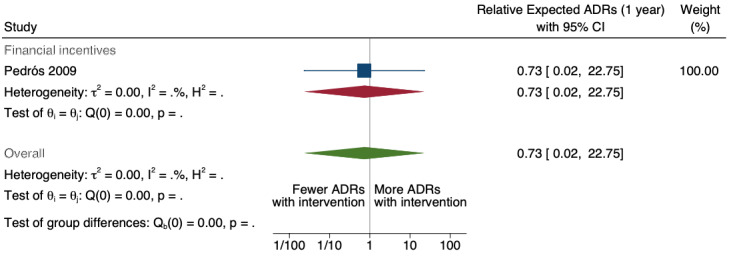

| Number of unexpected ADE reports (including unexpected ADR reports and unexpected ME reports): unexpected or previously unknown ADR reports after one year | 0.73 (0.02 to 22.75) | 20 ADR reports per 1000 practitioners | 15 ADR reports per 1000 practitioners (0 to 455) | 7.0 years (1)6 | Very low7 | We do not know if multifaceted interventions increase the total number of unexpected (previously unknown) ADR reports in physicians and pharmacists one year after implementation because the evidence is very uncertain Data after two years in footnotes8 |

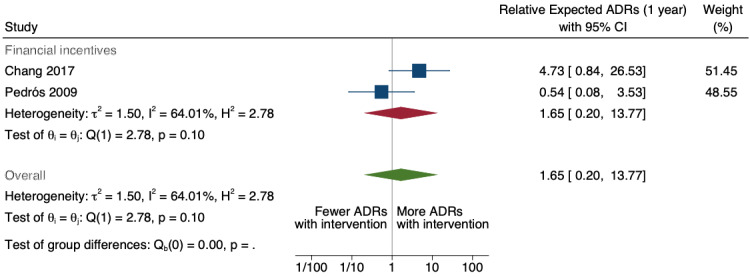

| Number of new drug‐related ADE reports (including drug‐related ADR reports and drug‐related ME reports): number of new drug‐ related ADR reports after one year | 1.65 (0.20 to 13.77) | 5 ADR reports per 1000 practitioners | 8 ADR reports per 1000 practitioners (1 to 69) | 6.5 years (2)1 | Very low2 | We do not know if multifaceted interventions increase the total number of new‐drug‐related ADR reports in physicians and pharmacists one year after implementation, because the evidence is very uncertain. Data after two years in footnotes9 |

ADE: adverse drug event; ADR: adverse drug reaction; CI: confidence interval; ITS: interrupted time series; ME: medication error; vs: versus

*Relative numbers of ADRs > 1 are associated with more ADRs with multifaceted intervention versus usual practice.

‡Illustrative comparative numbers of ADRs are presented as numbers of ADRs after 1 and 2 years in a setting with 1000 practitioners.

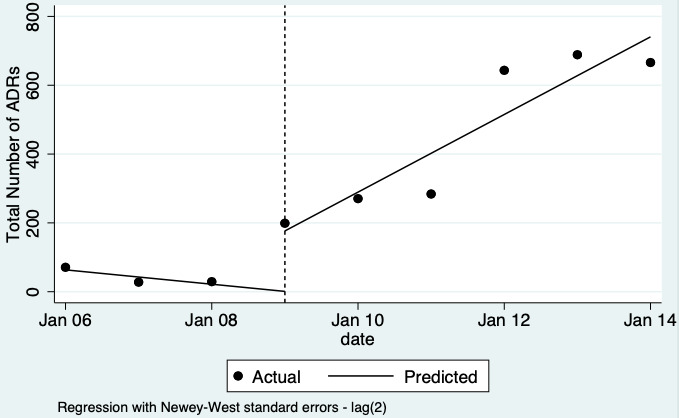

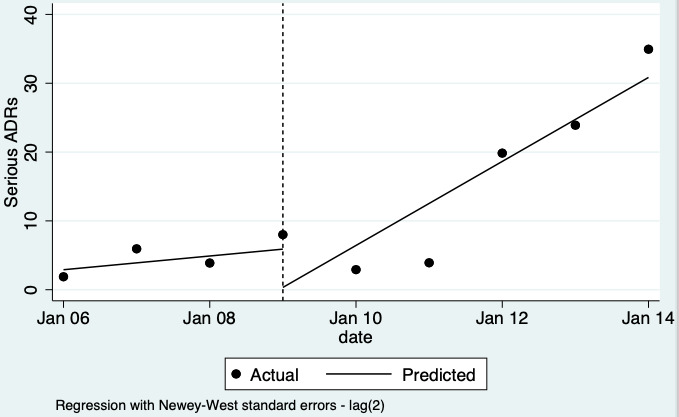

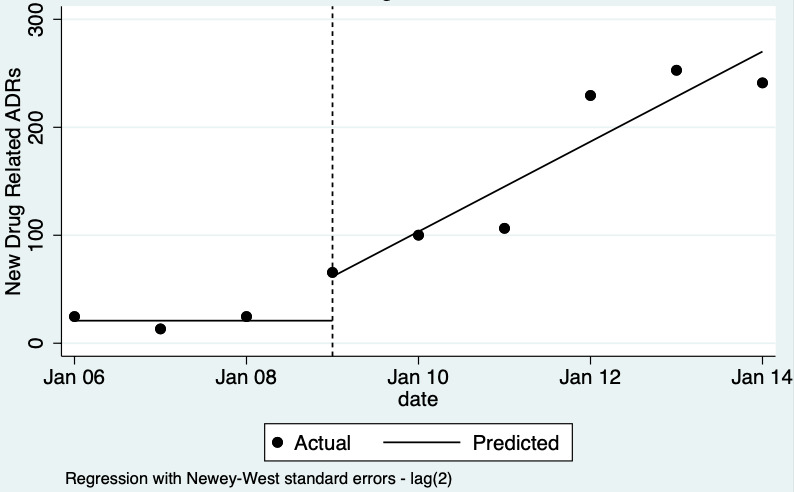

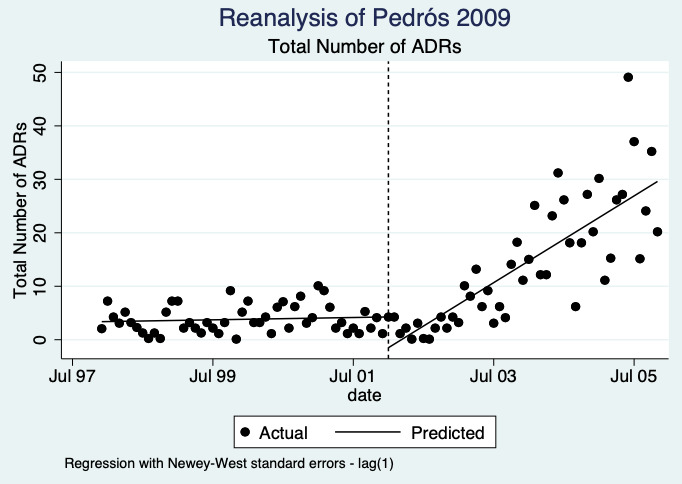

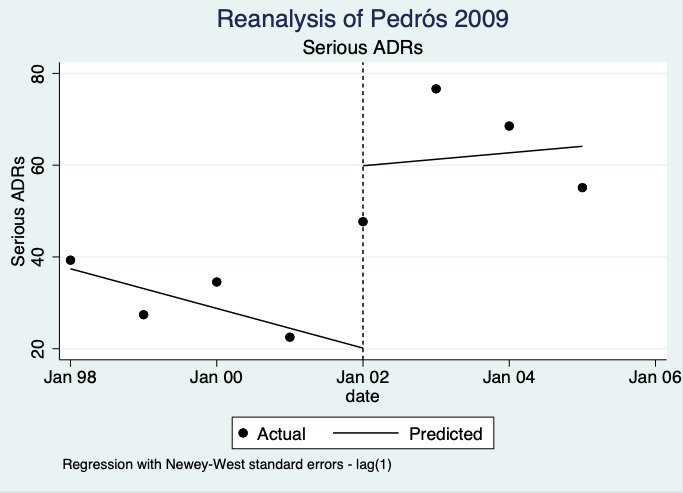

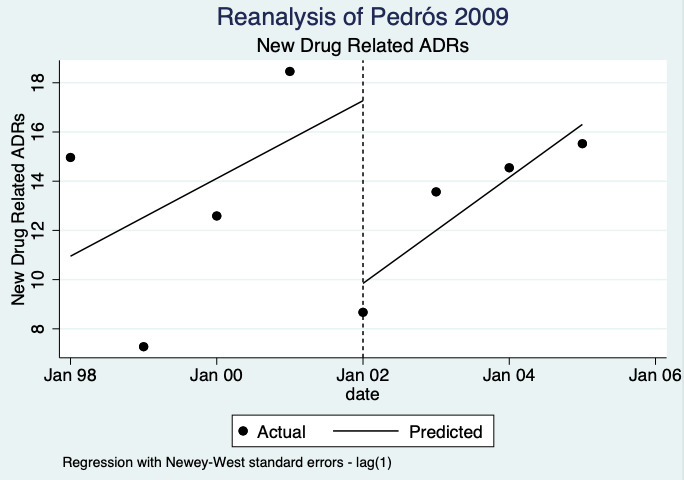

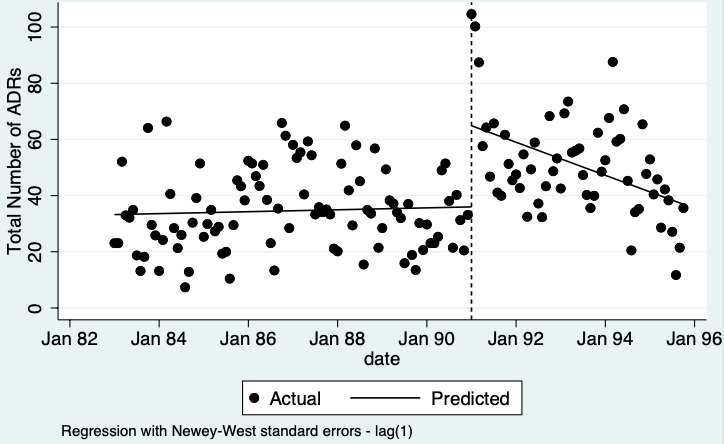

1Meta‐analysis of data from Chang 2017: financial incentive (1% of physician salary) for spontaneous reporting of ADRs plus fine (double the amount of the incentive) for not reporting or missing an ADR (study timeline ‐ 2006 to 2009 (pre‐intervention), 2009 to 2011 (financial incentive), 2012 to 2014 (financial incentive plus government regulations for antimicrobial agents), December 2014 (last time point), total 108 observations); and Pedrós 2009: financial incentives (1% of physicians salary) for spontaneous reporting of ADRs, twice‐yearly education meeting, reminder cards and list of the most important ADRs (study timeline ‐ January 1998 (first point); December 2002 (intervention implemented); December 2005 (last time point); a total of 96 observations)

2Both studies are observational ITS studies, so GRADE starts at low; downgraded once for serious risk of bias (high risk of bias for domain: intervention independent of other changes; there are no compelling arguments that the intervention occurred independently of other changes over time and the outcome was not influenced by other confounding variables or historic events during study period); downgraded once for serious inconsistency (I2 = 92% for year 1 and 81% for year 2, inconsistency between the studies may be explained by the fact that one study was conducted in China and the other in Spain, but not certain of this); no serious indirectness; downgraded once for serious imprecision (wide confidence intervals that cross the line of no effect); no other considerations.

3Data from Ali 2018 (intervention included implementation of financial and non‐financial incentives, i.e. employee of the month award, letters of appreciation, a day's leave, performance excellence award of extra month’s salary and a certificate) could not be included in the meta‐analysis as the length of follow‐up was much shorter (study timelines ‐ 2 years; a total of 24 observations) than Chang 2017 (8 years; 108 observations) and Pedrós 2009 (7 years; 96 observations). Data from Ali 2018 shows relative numbers of ADR reports after 1 year: 6.99, 95% CI 3.43 to 10.54; prior to intervention ‐ 80 ADR reports per 1000 practitioners, post intervention implementation ‐ 560 ADR reports per 1000 practitioners (274 to 843); very low certainty evidence as based on observational ITS study, so GRADE starts at low; downgraded once for serious risk of bias (high risk of bias for other bias ‐ seasonality not adjusted for; and intervention independent of other changes ‐ there are no compelling arguments that the intervention occurred independently of other changes over time and the outcome was not influenced by other confounding variables or historic events during study period); no serious inconsistency; no serious indirectness; no serious imprecision; no other considerations.

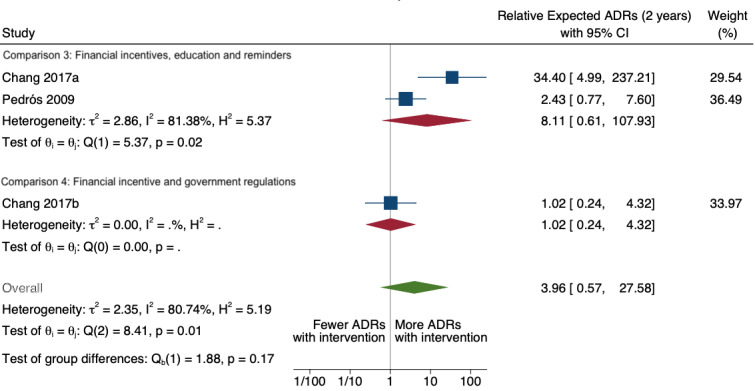

4Total number of ADE reports (including ADR reports and ME reports): relative number of ADR reports after 2 years 8.11 (95% CI 0.61 to 107.93); assumed number with usual practice 160 expected ADR reports per 1000 practitioners, corresponding number with multifaceted intervention 1298 expected ADR reports per 1000 practitioners (98 to 17,269), mean study duration 6.5 years, 2 studies1 ; certainty of the evidence: very low (see footnote2)

5Relative number of serious ADR reports after 2 years: 2.57 (95% CI 0.22 to 29.93); prior to intervention ‐ 20 ADR reports per 1000 practitioners, post intervention ‐ 51 ADR reports per 1000 practitioners (4 to 599) mean study duration 6.5 years (Chang 2017; Pedrós 2009); very low certainty evidence (see footnote2)

7Observational ITS study, so GRADE starts at low; downgraded once for serious risk of bias (high risk of bias for domain: intervention independent of other changes; there are no compelling arguments that the intervention occurred independently of other changes over time and the outcome was not influenced by other confounding variables or historic events during study period); no serious inconsistency; no serious indirectness; downgraded once for serious imprecision (wide confidence intervals that cross the line of no effect); no other considerations.

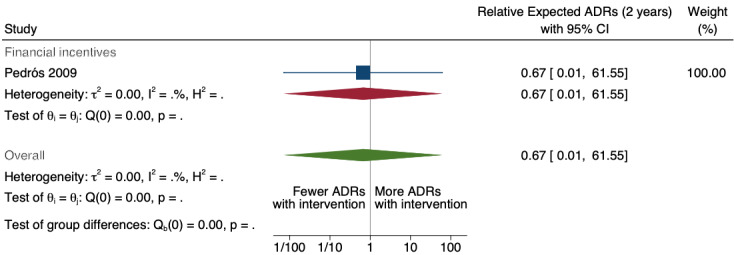

8Relative number of unexpected (previously unknown) ADR reports after 2 years: 0.67 (95% CI 0.01 to 61.55); prior to intervention ‐ 40 ADR reports per 1000 practitioners; post intervention implementation ‐ 27 ADR reports per 1000 practitioners (0 to 2462); mean study duration 7.0 years (Pedrós 2009); very low certainty evidence (see footnote7)

9Relative number of new drug‐related ADR reports after 2 years: 1.86 (95% CI 0.16 to 21.59); prior to intervention ‐ 10 ADR reports per 1000 practitioners; post intervention implementation ‐ 19 ADR reports per 1000 practitioners (2 to 216); mean study duration 6.5 years (Chang 2017; Pedrós 2009); very low certainty evidence (see footnote2)

Summary of findings 4. Government regulations plus financial incentives versus usual practice.

|

Participants: healthcare professionals Intervention: financial incentive, fines, plus government regulation, mandatory monitoring, and reporting of ADRs (timeline: 2009 to 2011 (financial incentive or fine); 2012 to 2014 (financial incentive or fine plus government regulations for antimicrobial agents) Comparator: spontaneous reporting (2006 to 2009: pre‐intervention) Setting: hospital | ||||||

| Outcome | Relative numbers of ADEs* (95% CI) | Illustrative comparative numbers of ADEs‡(95% CI) | Mean study duration (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed number with usual practice | Corresponding number with multifaceted intervention | |||||

| Total number of ADE reports (including ADR reports and ME reports): Total number of ADR reports after one year | 1.43 (0.54 to 3.79) | 80 ADR reports per 1000 practitioners | 114 ADR reports per 1000 practitioners (43 to 303) | 8.0 years (1)1 | Very low2 | We do not know if government regulations and financial incentives increase the total number of ADR reports by physicians one year after implementation of these interventions because the evidence is very uncertain. Data after two years in footnotes3 |

| Total number of false ADE reports (including false ADR reports and false ME reports) | None of the included studies reported on this outcome. | |||||

| Number of serious ADE reports (including serious ADR reports and serious ME reports) | None of the included studies reported on this outcome. | |||||

| Number of high‐causality ADE reports (including high‐causality ADR reports and high‐causality ME reports) | None of the included studies reported on this outcome. | |||||

| Number of unexpected ADE reports (including unexpected ADR reports and unexpected ME reports) | None of the included studies reported on this outcome. | |||||

| Number of new drug‐related ADE reports (including drug‐related ADR reports and drug‐related ME reports) | None of the included studies reported on this outcome. | |||||

ADE: adverse drug event; ADR: adverse drug reaction; CI: confidence interval; cRCT: cluster randomised controlled trials; ME: medication error; vs: versus

*Relative numbers of ADRs > 1 are associated with more ADRs with multifaceted intervention versus usual practice.

‡Illustrative comparative numbers of ADRs are presented as numbers of ADRs after 1 and 2 years in a setting with 1000 practitioners.

1Chang 2017: financial incentive (1% of physician salary) for spontaneous reporting of ADRs plus fine (double the amount of the incentive) for not reporting or missing an ADR plus government regulation of antimicrobial use including detailed ADR classification, mandatory monitoring, and reporting of ADRs associated with antimicrobial agents; (timeline ‐ 2006 to 2009 (pre‐intervention); 2009 to 2011 (financial incentive); 2012 to 2014 (financial incentive plus government regulations for antimicrobial agents); December 2014 (last time point); total of 108 observations)

2Observational ITS study so GRADE starts at low; downgraded by one for risk of bias (high risk of bias for domain: Intervention independent of other changes; there are no compelling arguments that the intervention occurred independently of other changes over time and the outcome was not influenced by other confounding variables or historic events during study period); no serious inconsistency; no serious indirectness; downgraded once for serious imprecision (wide confidence intervals that cross the line of no effect); no other considerations.

3Total number of ADE reports, including ADR reports and ME reports: number of ADR reports after 2 years 1.02 (95% CI 0.24 to 4.32, mean study duration: 8 years, 1 study1; assumed number of ADR reports with usual practice 160 ADR reports per 1000 practitioners, corresponding number of ADR reports with multifaceted intervention 163 ADR reports per 1000 practitioners (38 to 346); certainty of the evidence: very low2

Summary of findings 5. Improving access to ADR report forms versus usual practice.

|

Participants: healthcare professionals Intervention: improved access to ADE reporting (standardised discharge form method; yellow card ADR report form in bulletin and prescription pad; online hyperlink to ADR report form) Comparator: spontaneous reporting Setting: hospital | ||||||

| Outcome | Relative effect (95% CI)* | Illustrative comparative rates and numbers of ADEs‡(95% CI) | Number of participants or mean study duration (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed rate or number with usual practice | Corresponding rate or number with improving access | |||||

| Total number of ADE reports, including ADR reports and ME reports Data from cRCT |

2.06 (1.11 to 3.83) | 80 ADR reports per 1000 practitioner years | 165 ADR reports per 1000 practitioner years (89 to 306) | 5967 (1)1 | Low2 | Use of a standardised discharge form (for recording patient diagnoses, medical and surgical acts received during hospital stay; based on the ‘Diagnosis Related Groups’ (DRG) system) with additional ADR items (time of occurrence and evolution) may slightly increase the number of ADR reports. |

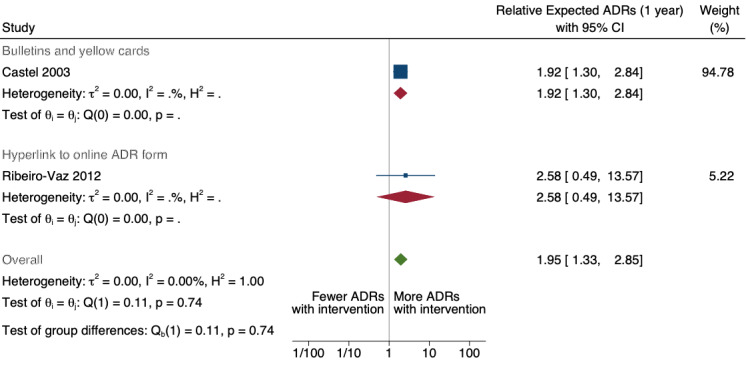

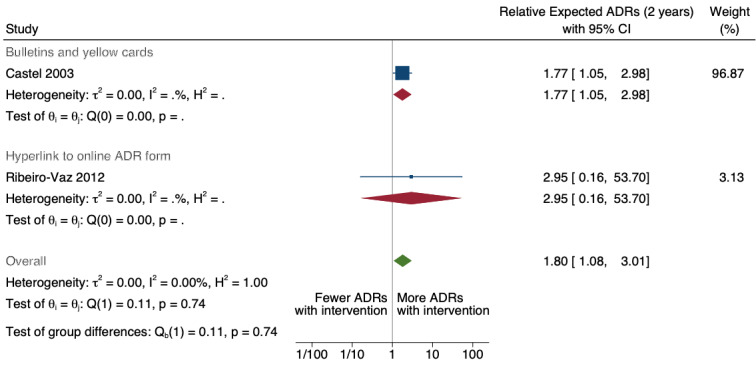

| Total number of ADE reports, including ADR reports and ME reports Data from ITS study after one‐year follow up |

1.95 (1.33 to 2.85) | 80 ADR reports per 1000 practitioners | 156 ADR reports per 1000 practitioners (106 to 228) | 8.4 years (2)3 | Very Low4 | We do not know if including yellow card ADR report form in quarterly bulletins and prescription pads or providing a hyperlink to the ADR report form in hospitals' electronic patient records may lead to more ADRs being reported after one year because the evidence is very uncertain. Data after two years in footnote5 |

| Total number of false ADE reports (including false ADR reports and false ME reports) | None of the studies included in this comparison reported on this outcome. | |||||

| Number of serious ADE reports (including serious ADR reports and serious ME reports) | None of the studies included in this comparison reported on this outcome. | |||||

| Number of high‐causality ADE reports (including high‐causality ADR reports and high‐causality ME reports) | None of the studies included in this comparison reported on this outcome. | |||||

| Number of unexpected ADE reports (including unexpected ADR reports and unexpected ME reports) | None of the studies included in this comparison reported on this outcome. | |||||

| Number of new‐drug‐related ADE reports (including new‐drug‐related ADR reports and new‐drug‐related ME reports) | None of the studies included in this comparison reported on this outcome. | |||||

ADE: adverse drug event; ADR: adverse drug reaction; CI: confidence interval; cRCT: cluster randomised controlled trial; ITS: interrupted time series; ME: medication error; vs: versus

*Relative treatment effects are expressed as risk ratios and, for ITS analyses, relative expected numbers of ADRs after 1 and 2 years. Relative treatment effects > 1 are associated with more ADRs with improving access versus usual practice.

‡Illustrative comparative rates and numbers of ADRs are presented as numbers of ADRs per 1000 practitioner years (for risk ratio) and expected numbers of ADRs after 1 and 2 years in a setting with 1000 practitioners (for the ITS studies).

Serious ADRs: resulting in death; is life‐threatening; is a congenital anomaly; requires hospital admission or prolongation of stay in hospital; or results in persistent or great disability, incapacity, or both; high‐causality ADRs: ADRs with attribution of definitive or probable causality; unexpected (previously unknown) ADRs: previously unknown ADRs that are not described in the summary of product characteristics; new‐drug‐related ADRs: ADRs concerning medications that have been on the market for less than five years.

1Hanesse 1994: cluster‐RCT (with cross‐over after 8 weeks, plus 2‐week washout period); the two methods for reporting ADRs were the spontaneous reporting method (SR method; usual care) and the standardised discharge form with additional ADR items (DRG method; intervention).

2Downgraded twice for very serious risk of bias (possible contamination effect due to cross‐over design and inability to blind physicians to the intervention; also unclear if the outcome assessors were blinded); no serious inconsistency; no serious indirectness; no serious imprecision; no other considerations

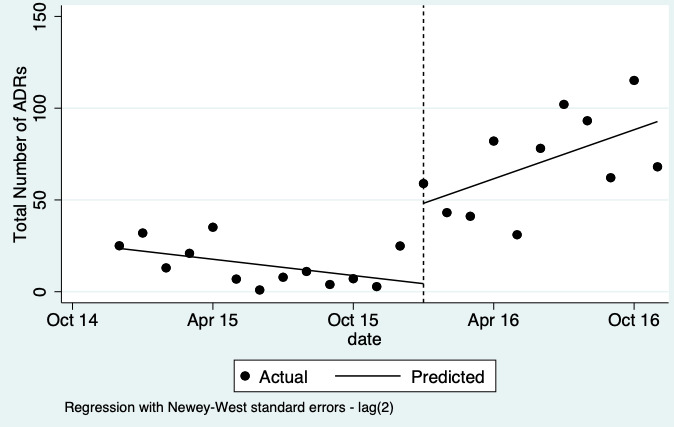

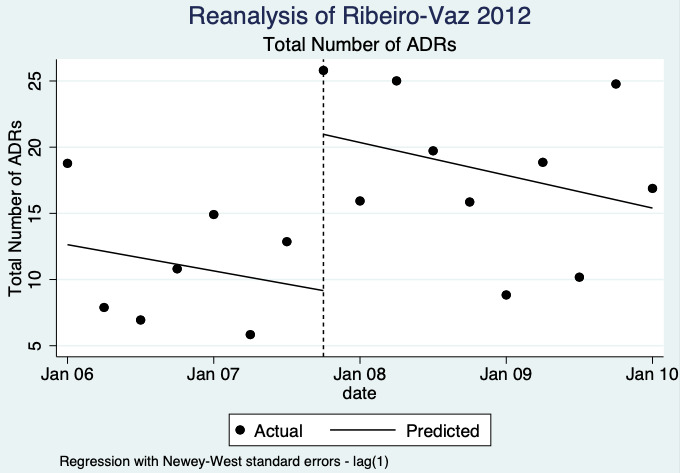

3Two ITS studies; Castel 2003: combined effect of quarterly adverse drug reaction bulletin with ADR yellow card report form (introduced Sept 1985) and a ADR yellow card report form in the prescription pad (introduced January 1991 to December 1994); Ribeiro‐Vaz 2012: 2006 to 2010 ‐ hyperlinks to the ADR online reporting pharmacovigilance centre form included either in the electronic patient record or on a desktop computer.

4Both studies are observational ITS studies so GRADE starts at low; downgraded once for serious risk of bias (high risk of bias for domain: intervention independent of other changes; there are no compelling arguments that the intervention occurred independently of other changes over time and the outcome was not influenced by other confounding variables or historic events during study period); no serious inconsistency: no serious imprecision: no serious indirectness; no other considerations.

5Total number of ADE reports, including ADR reports and ME reports: number of ADR reports after 2 years of follow‐up: RR1.80 (95% CI 1.08 to 3.01, assumed rate or number with usual practice: 160 ADR reports per 1000 practitioners; corresponding rate or number with improved access: 288 ADR reports per 1000 practitioners (173 to 482); mean study duration for 2 ITS studies3: 8.4 years; certainty of the evidence: very low4

Summary of findings 6. Improving ADE reporting method (new web‐based electronic error reporting system) versus usual practice (existing web‐based electronic error reporting system).

|

Participants: healthcare professionals Intervention: September 2010 replace existing electronic error reporting system with new web‐based electronic error reporting system (equipped with a series of standardised screens, drop‐down menu choices, and input fields designed to collect specific information and improve communication with all departments involved); post‐implementation segment (1 September 2010 to 31 October 2012) Comparator: pre‐implementation segment (1 January 2009 to 31 August 2010) ‐ web‐based electronic error reporting system Setting: hospital | ||||||

| Outcome | Relative numbers of reports (95% CI)* | Illustrative comparative numbers of reports‡ (95% CI) | Mean study duration (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed number with usual practice | Corresponding number with improved reporting system | |||||

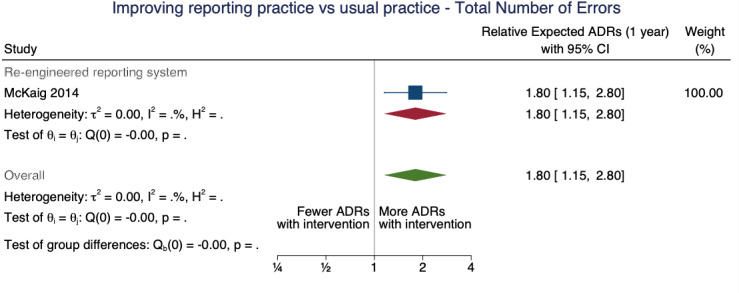

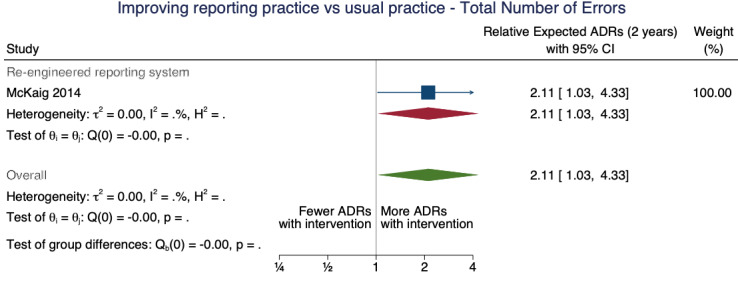

| Total number of ADE reports: number of ME reports after one year | 1.80 (1.15 to 2.80) | 80 ME reports per 1000 practitioners | 144 ME reports per 1000 practitioners (92 to 224) | 3.75 (1)1 | Very low2 | We do not know if the re‐engineering the web‐based electronic error reporting system may have increased the number of ME reports after one year because the evidence is very uncertain. Data after two years in footnotes3 |

| Total number of false ADE reports, including false ADR reports and false ME reports | None of the included studies reported on this outcome. | |||||

| Number of serious ADE reports (including serious ADR reports and serious ME reports) | None of the studies included in this comparison reported on this outcome. | |||||

| Number of high‐causality ADE reports (including high‐causality ADR reports and high‐causality ME reports) | None of the studies included in this comparison reported on this outcome. | |||||

| Number of unexpected ADE reports (including unexpected ADR reports and unexpected ME reports) | None of the studies included in this comparison reported on this outcome. | |||||

| Number of new‐drug‐related ADE reports (including new‐drug‐related ADR reports and new‐drug‐related ME reports) | None of the studies included in this comparison reported on this outcome. | |||||

ADE: adverse drug event; ADR: adverse drug reaction; CI: confidence interval; ITS: interrupted time series; ME: medication error; vs: versus

*Relative expected numbers of ME reports > 1 are associated with more ME reports with improving reporting practice versus usual practice.

‡Illustrative comparative rates are presented as expected numbers of ME reports after 1 and 2 years in a setting with 1000 practitioners.

1McKaig 2014: ITS; pre‐implementation segment (1 January 2009 to 31 August 2010), replace one web‐based electronic error reporting system with new web‐based electronic error reporting system (equipped with a series of standardised screens, drop‐down menu choices, and input fields designed to collect specific information and improve communication with all departments involved) implemented in September 2010, post‐implementation segment (1 September 2010 to 31 October 2012)

2Observational ITS so GRADE starts at low; downgraded once for serious risk of bias (authors do not appear to have considered seasonal effects and there is no control arm to counter this). Furthermore, there is no compelling argument that the effects of the intervention occurred independently of other changes over time; inconsistency: none; downgraded once for serious imprecision (wide confidence intervals that include little or no effect to substantial effect); indirectness: none; other: none.

3Total number of ADE reports, including ADR reports and ME reports: Relative number of ME reports after 2 years: 2.11 (95% CI 1.03 to 4.33), assumed number with usual practice: 160 ME reports per 1000 practitioners, corresponding number with different web‐based electronic error reporting system: 338 ME reports per 1000 practitioners (165 to 693); 1 study, 3.75 years exposure to intervention; very low certainty of evidence (see footnote2)

Summary of findings 7. Case finding versus spontaneous reporting (usual practice).

|

Participants: healthcare professionals Intervention: case finding ‐ clinical pharmacist identified ADEs by joining daily hospital rounds, screening patient charts and interviewing patients, daily meetings with physicians and nurses, comprehensive review of patient charts post‐discharge using specific data extract form to identify in‐hospital ADEs; ADEs were identified by (a) spontaneous or solicited reporting by a physician, (b) spontaneous or solicited reporting by a nurse, (c) detection on regular ward rounds and (d) detection by the clinical pharmacist by chart review after hospital discharge. Comparator: usual practice (clinical pharmacist not present; ADEs identified through spontaneous reporting by nurses and physicians) Setting: hospital | ||||||

| Outcome | Relative effect (95% CI)* | Illustrative comparative numbers of ADEs‡ (95% CI) | Number of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed number with usual practice | Corresponding number with case finding | |||||

| Total number of ADE reports (including ADR reports and ME reports): number of ADE reports Follow‐up: 12 months |

11.07 (6.24 to 21.38) | 1.4 per 1000 patient‐days | 15.5 (95% CI 8.74 to 29.9) per 1000 patient‐days | 1016 (1)1 | Very low2 | We do not know if having clinical pharmacists actively identifying and encouraging the identification of ADEs in a hospital setting leads to more ADEs being reported per 1000 patient‐days because the evidence is very uncertain. |

| Total number of false ADE reports (including false ADR reports and false ME reports): number of false ADE reports Follow‐up: 12 months |

None of the studies included in this comparison reported on this outcome. | |||||

| Number of serious ADE reports (including serious ADR reports and serious ME reports) | None of the studies included in this comparison reported on this outcome. | |||||

| Number of high‐causality ADE reports (including high‐causality ADR reports and high‐causality ME reports) | None of the studies included in this comparison reported on this outcome. | |||||

| Number of unexpected ADE reports (including unexpected ADR reports and unexpected ME reports) | None of the studies included in this comparison reported on this outcome. | |||||

| Number of new‐drug‐related ADE reports (including new‐drug‐related ADR reports and new‐drug‐related ME reports) | None of the studies included in this comparison reported on this outcome. | |||||

ADE: adverse drug event; ADR: adverse drug reaction; CI: confidence interval; ME: medication error; vs: versus

*Incidence rate ratio (IRR) of ADEs; IRR > 1 is associated with more ADE reports with case finding (clinical pharmacist present) versus usual practice (spontaneous reporting, no clinical pharmacist present).

‡Illustrative comparative rates are presented as expected numbers of ADEs per 1000 patient‐days.

Serious ADRs: resulting in death; is life‐threatening; is a congenital anomaly; requires hospital admission or prolongation of stay in hospital; or results in persistent or great disability, incapacity, or both); high‐causality ADRs: ADRs with attribution of definitive or probable causality; unexpected (previously unknown) ADRs: previously unknown ADRs that are not described in the summary of product characteristics; new‐drug‐related ADRs: ADRs concerning medications that have been on the market for fewer than 5 years.

1Schlienger 1999: non‐randomised cross‐over study, without a washout period. To minimise any possible learning effect, we have only included and analysed the data from the first period (1 to 12 months) of the study. In the test units: case finding ‐ clinical pharmacist identified ADEs by joining daily hospital rounds, screening patient charts and interviewing patients, daily meetings with physicians and nurses, comprehensive review of patient charts post‐discharge using specific data extract form to identify in‐hospital ADEs; ADEs were identified by (a) spontaneous or solicited reporting by a physician, (b) spontaneous or solicited reporting by a nurse, (c) detection on regular ward rounds and (d) detection by the clinical pharmacist by chart review after hospital discharge. In control units: clinical pharmacist not present; ADEs identified through spontaneous reporting by nurses and physicians.

2Because it is not a randomised study, the GRADE assessment starts at low; downgraded twice for very serious risk of bias (risk of selection bias as not randomised, risk of performance as no blinding of physicians or nurses, and risk of detection bias as no blinding of outcome assessors); no serious inconsistency: no serious indirectness; no serious imprecision; no other considerations.

Background

Description of the condition

Approximately 1.4% of the global Gross Domestic Product (US$1 trillion) is spent on medicines (World Bank). Medicines cure, arrest or prevent disease, ease symptoms or help diagnose illnesses. However, a great deal of morbidity and mortality is associated with unforeseen reactions to and inappropriate use of medicines. Adverse drug events, defined as “any untoward medical occurrence that may present during treatment with a pharmaceutical product but which does not necessarily have a causal relationship with this treatment” (Uppsala Monitoring Center), are a global public health issue.

Adverse drug events (ADEs) include all adverse drug reactions and medication errors. An adverse drug reaction is “a harmful effect suspected to be caused by a drug at doses normally used in humans for the prophylaxis, diagnosis, or therapy of disease, or for the modification of physiological function” (Uppsala Monitoring Center). A medication error is “any preventable event that may cause or lead to inappropriate medication use or patient harm while the medication is controlled by the health care professional, patient, or consumer. Such events may be related to professional practice, health care products, procedures, and systems, including prescribing, order communication, product labelling, packaging, nomenclature, compounding, dispensing, distribution, administration, education, monitoring, and use” (NCCMERP 2016).

No medicine is without ADEs. While some ADEs are detected during pre‐marketing phase clinical trials, limitations associated with the conduct of these trials make it impossible to identify all ADEs related to a product. Trial characteristics such as small sample size, relatively short follow‐up periods, close monitoring of study participants (to ensure strict adherence to study protocol), and narrowly defined characteristics of study participants and study indications (study indications for a drug are often limited to a particular disease; Gad 2009) are important for study validity and efficacy but limit the generalisability and effectiveness of the study findings. Continually monitoring the use and effects (both beneficial and harmful) of clinically approved medicines in large numbers of people is therefore important to better understand the effectiveness and safety of medication under everyday circumstances.

Pharmacovigilance, which is "the science and activities relating to the detection, assessment, understanding, and prevention of adverse effects or any other drug‐related problems" (WHO 2006), aims to improve patient safety related to the use of medicines (Fornasier 2018). More than 170 countries have pharmacovigilance agencies that collate and manage adverse event reporting (WHO 2016). Identifying any adverse drug events associated either with a medication or with the use of a medication, as soon as possible, prevents or minimises any potential harm. These efforts enable healthcare professionals to maximise the benefits of medicines while avoiding or minimising the risks associated with their use. Spontaneous or voluntary reporting of ADEs (i.e. case reports of ADEs that are voluntarily submitted from healthcare professionals and pharmaceutical manufacturers to the national regulatory authority (Uppsala Monitoring Center)) is the cornerstone of effective pharmacovigilance and is considered "usual practice" in most parts of the world. The level of pharmacovigilance and adverse drug event reporting differs greatly based on the regulations established by the respective regulatory agencies. Data collection also varies amongst countries. France, for example, has regional centres for collecting spontaneous reports, while Iran has a single national pharmacovigilance centre to collect data (Shalviri 2009). Although spontaneous reporting of ADEs is the most common method for collecting information on the safety of medicines during the post‐marketing phase (Figueiras 2001; Pal 2013), it is limited and is associated with gross underreporting of ADEs. According to the WHO Monitoring Center in Uppsala, annual reporting rates of over 200 adverse drug event reports per million inhabitants indicate a healthy national pharmacovigilance system (Lindquist 2008). Many countries have yet to achieve this goal. It is estimated that only 2% to 4% of non‐serious adverse drug events and 10% of serious ADEs are reported spontaneously by healthcare professionals (Hazell 2006; Moride 1997). It should be noted that reports from patients and healthcare students are also valuable contributors to drug‐related data in many countries. However, these populations are not within the scope of this review.

Description of the intervention

Although spontaneous reporting of adverse drug events is the most common method of collecting safety data associated with medications, there are other methods of collecting safety information (WHO 2006). Some countries have implemented active surveillance systems to complement spontaneous reporting, for example, the prescription event monitoring (PEM) system in New Zealand and the United Kingdom (WHO 2006). In the European Union, a set of measures called “good pharmacovigilance practices” have been drawn up to facilitate pharmacovigilance (EMA 2016). Various interventions have been used in different settings to improve healthcare professionals' spontaneous reporting of ADEs. The most commonly used interventions include the following (Gonzalez‐Gonzalez 2013; Molokhia 2009).

Educational activities such as training sessions

Reminders such as letters, emails or posters

Simplification of the adverse drug event reporting form

Increased availability of reporting forms

Modification of reporting procedures (e.g. reporting by telephone or email)

Incentives such as provision of educational credits, awards or financial motivations, or disincentives for not reporting, e.g. fines

Assistance from a colleague (e.g. a clinical pharmacist, physician or nurse) with ADE reporting

Providing feedback to reporters about adverse drug events

Use of computerised monitoring systems to signal changes in laboratory results

Some studies focus specifically on developing interventions to improve medication error reporting. For example, a study in New Zealand designed a web‐based medication error reporting programme (MERP) to supplement pharmacovigilance (Kunac 2014). Some studies choose to examine more than one intervention. For example, seven overlapping interventions were used in a study to improve ADE reporting, including a poster displaying days since the last medication error resulting in harm, a continuous slide show in the staff lounge showing performance metrics, multiple didactic curricula, unit‐wide emails providing information on medication errors, computerised physician order entry, introduction of unit‐based pharmacy technicians for medication delivery, and patient safety report form streamlining (Abstoss 2011).

How the intervention might work

Reasons for inadequate spontaneous reporting or underreporting of adverse drug events by healthcare professionals include complacency (e.g. the belief that very serious adverse drug reactions are well documented by the time a drug is marketed), insecurity (e.g. the belief that it is nearly impossible to determine whether a drug is responsible for a particular adverse reaction), diffidence (e.g. healthcare professionals are afraid of looking foolish or over‐reactive by submitting a report for an adverse event that is not severe or not obviously related to a medical product or the use of a medical product), indifference (e.g. some healthcare professionals feel that the one case they might observe could not contribute to medical knowledge), ignorance (e.g. the belief that it is only necessary to report serious or unexpected adverse drug reactions), and lack of time to complete the adverse drug event reporting procedure (Mirbaha 2015; Varallo 2014). Healthcare professionals may also fear being blamed for any adverse event they draw attention to, that acknowledging an adverse reactions may reflect negatively on their competence or put them at risk of litigation (WHO 2006).

Understanding the barriers associated with underreporting of adverse drug events guides the design of interventions to address or minimise the impact of these barriers or reasons for inadequate spontaneous reporting of ADEs. Educational interventions and informational reminders could raise awareness of the importance of reporting adverse drug events. Other interventions aim to simplify or improve the accessibility of the reporting process itself and, in this way, increase the reporting rate. Interventions that reward healthcare professionals with either financial or non‐financial incentives for reporting ADEs may also facilitate increases in the reporting rates of adverse drug events. Incentivised interventions may also lead to false reports, however, so checks and balances in the system are necessary.

Results of observational studies seem to suggest that although interventions involving educational sessions (Bäckström 2002), improving access to ADR report forms (McGettigan 1997), or financial incentives (Feely 1990) increase the reporting rate of adverse drug events, the effect of these interventions is temporary, and reporting rates decline once the intervention is removed (McGettigan 1997). The ultimate aim of interventions is to create a "culture of reporting" amongst healthcare professionals that is effective and sustained. Integrating the reporting of adverse drug events into existing hospital electronic reporting systems may be one example of a way to achieve this (Ortega 2008).

Why it is important to do this review

The World Health Organization (WHO) International Drug Monitoring Program was created in response to the lack of global harmonisation for monitoring of ADEs (WHO 2006). The programme currently includes over 170 countries as full members and associate members (WHO 2016). Despite the numerous pharmacovigilance activities undertaken in many countries, the problem of underreporting adverse drug events is still a major threat to the public's health and well‐being. Adverse drug events are a significant cause of death in many countries (Lazarou 1998; Pirmohamed 2004; Shalviri 2009; Shalviri 2012; Wester 2008), and a significant cause of hospital admissions (Al Hamid 2014; Wilson 2012). Furthermore, a substantial portion of healthcare costs are directly related to adverse drug events, with the economic burden amounting to hundreds of billions of dollars each year (Andel 2012; Classen 1997; Ernst 2001; Gyllensten 2013; Johnson 1995).

Many adverse drug events are preventable. Studies have reported that 10% to 80% of all adverse drug events can be prevented (WHO 2014). Improved spontaneous reporting of suspected adverse drug events enables early detection of any patient safety issues associated with the medication itself or with how the medication is used (Pal 2013), which can reduce drug‐related morbidity and mortality (Pal 2013). Several systematic reviews have assessed the effectiveness of interventions to enhance the reporting of adverse drug events (Gonzalez‐Gonzalez 2013; Li 2019; Pagotto 2013; Paudyal 2020). These reviews are limited in their scope in terms of intervention (educational interventions; Pagotto 2013) or outcome (ADRs; Gonzalez‐Gonzalez 2013; Li 2019; Paudyal 2020). Furthermore, none of the systematic reviews have provided an assessment of the certainty of the evidence for each of the interventions assessed (see Table 8). This Cochrane review aims to identify all interventions directed at healthcare professionals that may improve reporting of adverse drug events, including all ADRs and any MEs. Our review will also systematically assess the certainty of the evidence associated with each type of intervention.

1. Overview of published systematic reviews assessing interventions to increase ADE reporting.

| Pagotto 2013 | Gonzalez‐Gonzalez 2013 | Ribeiro‐Vaz 2016 | Li 2019 | Paudyal 2020 | Khalili 2020(scoping review) | |

| Objectives | To identify the techniques of educational intervention for promotion of pharmacovigilance by healthcare professionals and to assess their impact. | To conduct a critical review of papers that assessed the effectiveness of different strategies to increase ADR reporting, regardless of the healthcare professionals or patients included. | To describe the state of the art information systems used to promote ADR reporting. | To determine the features and successes of the various strategies undertaken to improve ADR reporting by healthcare professionals, and propose alternative initiatives that may enhance these existing methods. | To evaluate the effectiveness of interventions used for improving ADR reporting by patients and healthcare professionals. | To systematically map interventions and strategies to improve ADR reporting among health care professionals. |

| Eligible study designs | All study designs included | Pre‐post experimental design; time series; non‐randomised controlled experimental study; randomised controlled experimental study; cluster randomised controlled experimental study | Any studies describing or evaluating the use of information systems to promote adverse drug reaction reporting. Studies with data related to the number of ADRs reported before and after each intervention and the follow‐up period were included in the quantitative analysis. | RCTs, quasi‐experimental, time series studies | All forms of interventional designs were considered. Meta analysis not undertaken for non‐randomised trials | Quantitative methods focused on healthcare professionals |

| Eligible participants | Healthcare professionals | Professionals to whom the intervention for increasing ADR reporting is addressed: physicians, nurses, pharmacists, young physicians, house officers, pharmacy students, section head, ‘quality review staff’, medical students. | Healthcare professionals or patients | Healthcare professionals | Healthcare professionals and patients | Healthcare professionals |

| Eligible interventions | Educational interventions only | Educational activity, reminders, modification of reporting forms, modifciation of reporying process, incentives, assistance from another professiionl, increased availability of reporting forms, feedback on reporting | Studies describing or evaluating the use of information systems to promote adverse drug reaction reports were selected | Any intervention aimed at increasing ADR reporting | Any pharmacovigilence intervention | Any intervention or strategy (such as ones implemented by government policies, applied experimentally or non‐experimentally, or adopted in specific settings) to improve ADR reporting |

| Eligible comparison | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated |

| Outcomes reported on | ADE reporting | Increase in ADR reporting | Rate of ADR reporting increase | ADR rporting | Primary outcome: quantity of ADRs reported as a result of the intervention including improvement in the number or rate of reporting. Secondary outcomes: the quality of ADR reporting including the nature of ADRs reported (e.g. serious, nonserious ADRs) and completeness of the reports. | ADR reporting rate |

| Number and type of studies | 16 met the inclusion criteria 6 RCT, 5 quasi‐experimental, 2 case‐ control studies, 2 ecological time series analysis, 1 observational analytic) | 43 studies | 33 articles were included in the analysis; these articles described 29 different projects. | 13 studies included (3 cRCTs, 1 RCT, 7 quasi‐experimental, 2 ITS) | 28 studies | 90 studies included in qualitative synthesis |

| Findings and conclusions | Pharmacovigilance‐based educational interventions showed positive impacts (quantitative and qualitative) on ADE spontaneous reporting by health professionals. Multifaceted techniques for interventions, included: lectures, placement of yellow cards, distribution of printed educational materials and giveaways, as well as the or‐ ganization of workshops | Multiple interventions have a greater impact than single. Evidence to show that, when it comes to bringing about changes in professional practice, interventions that boost the active participation of professionals (i.e. workshops) can be more effective than passive didactic sessions. Another vital factor is the duration of the effect of the intervention. It can be concluded that, as was to be expected, the longer the period from the date of the intervention, the more the latter's effect is progressively reduced. |

Most projects performed passive promotion of ADR reporting (i.e., facilitating the process). Developed in hospitals and tailored to healthcare professionals. Interventions doubled the number of ADR reports. Authors believe that it would be useful to develop systems to assist healthcare professionals with completing ADR reporting within electronic health records because this approach seems to be an efficient method to increase the ADR reporting rate. When this approach is not possible, it is essential to have a tool that is easily accessible on the web to report ADRs. This tool can be promoted by sending emails or through the inclusion of direct hyperlinks on healthcare professionals’ desktops. | Multi‐faceted approach including education, reminders, and electronic reporting would likely to be the most successful. | Limited evidence showed that active interventions involving face to face educational approaches, financial incentives, and electronic features targeted at healthcare professionals could improve ADR reporting. However, the results need to be interpreted cautiously given the short term evaluation out‐ comes, dominance of observational designs and low quality of included studies. Interventions need to be developed and tested in countries low‐and‐middle income countries. Most of the included studies included educational interventions to improve ADR reporting. A variety of educational methods were used including reminders, face to face educational sessions and newsletters. While most of these studies were reported to have improved ADR reporting, there was a lack of long‐term follow up of the outcomes. The cluster‐ randomized controlled trials included in the study reported that the impact of interventions observed by the difference in the intervention and control group in the ADR reporting rate lasted for only 12 months after which such difference was no longer significant. | Interventions aimed at enhancing ADR reporting have a good chance of producing positive results, although their effect, especially in the case of educational interventions, could be temporary. Multiple inter‐ ventions might cause greater increase in ADR reporting rates compared with single interventions. Further research is warranted to improve the methodological quality using control groups, large sample sizes, longer follow‐up periods, and adjustment for the confounders. |

| Any limits noted | Language limit: English, Portuguese, or Spanish search for publications from November 2011 to January 2012, updated in March 2013. Quality assessment of the manuscripts was not carried out. | Limit publication date: up to 2010; Language limited to English, French or Spanish | Language limited to English, Portuguese or French Excluded articles based on: (1) only focused on medication errors; (2) only focused on ADR detection; (3) studies without any information system implemented; (4) studies concerning data quality; (5) studies focused on website usability; (6) authors’ reflections on the theme; (7) studies only related to incidents that occurred in health institutions; (8) studies concerning signal detection and (9) studies concerning electronic transmission between the authority and other institutions (pharmaceutical companies or regional pharmacovigilance centres). | Search limited to studies published from 2010 to 2019; English only; NO medication error reporting | Educational research with student participants; interventions not including qualified healthcare practitioners or patients were excluded as well as the interventions related to devices and planned ADR surveillance monitoring programmes, such as those used for mass vaccinations; Abstract only publications including conference abstracts were excluded. | Search date limited from 1999 to February 2019; no language restrictions; methodological quality or risk of bias of the included articles were not appraised |

ADE: adverse drug event; ADR: adverse drug reaction; cRCT: cluster‐randomised controlled trial; ITS:interrupted time series; RCT: randomised controlled trial

Objectives

To assess the effectiveness of different interventions aimed at healthcare professionals to improve the reporting of adverse drug events.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included both individually randomised trials and cluster‐randomised trials, non‐randomised controlled studies and controlled before‐after studies. For cluster‐randomised trials, non‐randomised cluster trials and controlled before‐after studies, we included only those with at least two intervention sites and two control sites (EPOC 2013a). In addition, for controlled before‐after studies, data collection had to be contemporaneous in both the intervention and control groups during the pre‐ and post‐intervention periods, and identical measurement methods had to be used in these periods. We also included interrupted time series and repeated measures studies that had a clearly defined time point when the intervention occurred and at least three data points before and after the intervention (EPOC 2013b). We included data from both published (full‐text articles and conference abstracts) and unpublished eligible studies.

Types of participants

We included studies in which healthcare professionals (including but not limited to general practitioners, pharmacists, nurses and specialists) from any healthcare setting were the target audience of the intervention. We excluded studies aimed at patients and healthcare students (e.g. medical, nursing, pharmacy) as the target audience.

Types of interventions

We included studies assessing any intervention designed to increase adverse drug event reporting, compared with healthcare professionals' usual adverse drug event reporting practice (mainly spontaneous or voluntary reporting) or a different intervention or interventions designed to improve adverse drug event reporting. We excluded studies of interventions targeted at adverse events reporting following immunisation (AEFI) as AEFI monitoring uses different mechanisms and settings.

Types of outcome measures

An adverse drug event (ADE) is defined as "any untoward medical occurrence that may present during treatment with a pharmaceutical product but which does not necessarily have a causal relationship with this treatment" (Uppsala Monitoring Center). ADEs can include both adverse drug reactions (ADRs) and medication errors (MEs). According to the Uppsala Monitoring Center, an adverse drug reaction (ADR) is defined as "a harmful effect suspected to be caused by a drug", including "all kinds of adverse events, many of which are not 'reactions' in the strict sense and have not been subject to any assessment of causality" (Uppsala Monitoring Center). A medication error (ME) is "any preventable event that may cause or lead to inappropriate medication use or patient harm while the medication is controlled by the health care professional, patient, or consumer. Such events may be related to professional practice, health care products, procedures, and systems, including prescribing, order communication, product labelling, packaging, nomenclature, compounding, dispensing, distribution, administration, education, monitoring, and use" (NCCMERP 2016).

Primary outcomes

Total number of ADE reports, including ADR reports and ME reports, submitted by healthcare professionals

Total number of false ADE reports, including false ADR reports and false ME reports, submitted by health care professionals

Secondary outcomes

-

Number of serious ADE reports (including serious ADR reports and serious ME reports)

ADEs that result in death, are life‐threatening, are a congenital anomaly, require hospital admission or prolongation of stay in hospital, or result in persistent or significant disability or incapacity or both

-

Number of high‐causality ADE reports (including high‐causality ADR reports and high‐causality ME reports)

ADEs with attribution of definitive or probable causality

-

Number of unexpected ADE reports (including unexpected ADR reports and unexpected ME reports)

Previously unknown ADEs that are not described in the drug's summary of product characteristics

-

Number of new‐drug‐related ADE reports (including new‐drug‐related ADR reports and new‐drug‐related ME reports)

ADEs relating to medications that have been on the market for less than five years

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

An EPOC Information Specialist developed the search strategies in consultation with the review authors. We searched the following databases from inception to 14 October 2022.

Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) via EbscoHost (1980 to 14 October 2022)

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR), Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE), Health Technology Assessment (HTA) database, and NHS Economic Evaluation Database (NHS EED) via the Cochrane Library (Issue 10, 2022; searched on 14 October 2022)

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (includes the entirety of the EPOC Group Specialised Register) via the Cochrane Library (Issue 10, 2022; searched on 14 October 2022)

Embase via OvidSP (1974 to 14 October 2022)

Science Citation Index (SCI), Social Sciences Citation Index (SSCI) via Web of Knowledge (1975 to 14 October 2022)

Conference Proceedings Citation Index‐ Science (CPCI‐S) via Web of Science (1990 to 14 October 2022)

MEDLINE (In‐Process and other non‐indexed citations) via OvidSP (1946 to 14 October 2022)

Dissertations & Theses (COS Conference Papers Index; ProQuest Dissertations & Theses: UK & Ireland; ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global) via ProQuest (1861 to 11 March 2021)

Virtual Health Library (VHL) Regional Portal via pesquisa.bvsalud.org/portal/advanced/?lang=en; search date: 17 October 2022

World Health Organization Library Catalogue (WHOLIS/IRIS) via https://kohahq.searo.who.int; search date: 17 October 2022

We also searched the following trial registries for potentially eligible ongoing studies on 17 October 2022.

Word Health Organization (WHO) International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) via www.who.int/ictrp/en;

ClinicalTrials.gov via clinicaltrials.gov.

Searches were not restricted by language, date or format of publication. The search strategies used are provided in Appendix 1.

Searching other resources

We conducted a grey literature search of the following databases using key terms "adverse drug event" OR "adverse drug reaction" OR "medication error" to identify additional potentially eligible studies.

OpenGrey via opengrey.eu (last search date 20 August 2018; database no longer updated)

Grey Literature Report, New York Academy of Medicine via www.nyam.org/library/collections-and-resources/#greylit (last search date 20 August 2018; database no longer updated)

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) via www.ahrq.gov (last search date 20 August 2018);

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) via www.nice.org.uk (last search date 20 August 2018)

Bielefeld Academic Search Engine (BASE) via www.base-search.net (last search date 20 August 2018)

We also screened the reference lists of all included studies and relevant systematic reviews and primary studies. We contacted authors of relevant studies or reviews to clarify reported published information and to seek unpublished results or other data for potentially eligible studies. We contacted experts in the field for information on additional eligible ongoing or completed studies.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

All references retrieved through electronic searching were downloaded into a reference management database (EndNote 2013). After removing all duplicate references, the search records were uploaded to the review management programme Covidence (Covidence). Two review authors (from GS, NM, LG, WYC) independently screened the titles and abstracts for inclusion. We obtained the full texts of all the potentially eligible studies, and two review authors (from GS, NM, LG, WYC) independently screened these for inclusion. We noted the reasons for excluding any potentially eligible full‐text studies, and these are provided in a Characteristics of excluded studies table. Any disagreement between review authors regarding study eligibility was resolved through discussion or, if required, consultation with a third author (KG). We collated multiple reports of the same study so that each study, rather than each report, was the unit of interest in the review. Details about (potentially) eligible ongoing studies are provided in a Characteristics of ongoing studies table. If we were unable to obtain the full text of a potentially eligible study and could not determine the eligibility of the study, we recorded the study details in a Characteristics of studies awaiting classification table. We presented the study selection process in a PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1).

1.

PRISMA flow diagram