Summary

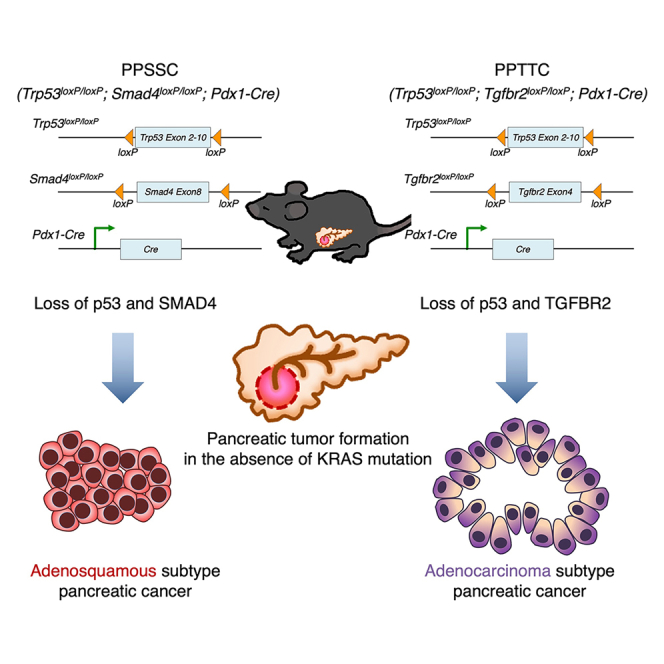

Pancreatic cancer is associated with an oncogenic KRAS mutation in approximately 90% of cases. However, a non-negligible proportion of pancreatic cancer cases harbor wild-type KRAS (KRAS-WT). This study establishes genetically engineered mouse models that develop spontaneous pancreatic cancer in the context of KRAS-WT. The Trp53loxP/loxP;Smad4loxP/loxP;Pdx1-Cre (PPSSC) mouse model harbors KRAS-WT and loss of Trp53/Smad4. The Trp53loxP/loxP;Tgfbr2loxP/loxP;Pdx1-Cre (PPTTC) mouse model harbors KRAS-WT and loss of Trp53/Tgfbr2. We identify that either Trp53/Smad4 loss or Trp53/Tgfbr2 loss can induce spontaneous pancreatic tumor formation in the absence of an oncogenic KRAS mutation. The Trp53/Smad4 loss and Trp53/Tgfbr2 loss mouse models exhibit distinct pancreatic tumor histological features, as compared to oncogenic KRAS-driven mouse models. Furthermore, KRAS-WT pancreatic tumors with Trp53/Smad4 loss reveal unique histological features of pancreatic adenosquamous carcinoma (PASC). Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) analysis reveals the distinct tumor immune microenvironment landscape of KRAS-WT (PPSSC) pancreatic tumors as compared with that of oncogenic KRAS-driven pancreatic tumors.

Keywords: pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, pancreatic adenosquamous carcinoma, single-cell RNA-sequencing analysis, genetically engineered mouse models, tumor microenvironment

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Loss of p53/SMAD4 or p53/TGFBR2 can induce pancreatic cancer without a KRAS mutation

-

•

Loss of p53 and SMAD4 induces adenosquamous subtype pancreatic cancer in mice

-

•

Pancreatic tumors with p53/SMAD4 loss reveal a distinct microenvironment landscape

-

•

Loss of p53 and TGFBR2 induces adenocarcinoma subtype pancreatic cancer in mice

Yang et al. identify that loss of p53/SMAD4 or p53/TGFBR2 can induce spontaneous pancreatic tumor development in the absence of KRAS mutation in mice. Pancreatic tumors harboring p53/SMAD4 loss exhibit an adenosquamous phenotype with a distinct microenvironment landscape, while pancreatic tumors harboring p53/TGFBR2 loss exhibit an adenocarcinoma phenotype.

Introduction

Pancreatic cancer is a highly lethal malignant disease that remains refractory to therapies. Pancreatic cancer development is associated with the dominant occurrence of an oncogenic KRAS gene mutation in approximately 90% of cases.1 In addition, mutations and/or deficiencies of tumor suppressor genes, including TP53 (60%–70%), CDKN2A (30%–40%), and SMAD4 (30%–40%), are commonly noted.2,3 Approximately 10% of pancreatic cancer cases harbor wild-type KRAS (hereafter referred to as “KRAS-WT”), whereas the mechanism of KRAS-WT pancreatic cancer development remains less understood.4,5,6,7 Recent studies identified a variety of alternative driver mutations, deletions, or fusions in KRAS-WT pancreatic cancer, providing insights into the molecular mechanism and potential therapeutic strategies for KRAS-WT pancreatic cancer.8,9,10,11,12

In the past decades, genetically engineered mouse models with spontaneous pancreatic cancer development have provided insights into the mechanisms by which the oncogenic KRAS mutation, in combination with tumor suppressor gene deficiency, drives pancreatic tumor initiation, progression, and metastasis.13,14,15 However, genetically engineered mouse models that recapitulate the development of KRAS-WT pancreatic cancer are still lacking.

In this study, we established genetically engineered mouse models that can develop autochthonous pancreatic tumors in the background of KRAS-WT. The Trp53loxP/loxP;Smad4loxP/loxP;Pdx1-Cre (PPSSC) mouse model harbors KRAS-WT and loss of Trp53/Smad4. The Trp53loxP/loxP;Tgfbr2loxP/loxP;Pdx1-Cre (PPTTC) mouse model harbors KRAS-WT and loss of Trp53/Tgfbr2. We identified that either Trp53/Smad4 loss or Trp53/Tgfbr2 loss is sufficient to induce spontaneous pancreatic tumor formation in the absence of the oncogenic KRAS mutation. We compared the pancreatic tumor histology of Trp53/Smad4 loss and Trp53/Tgfbr2 loss mouse models with that of oncogenic KRAS-driven mouse models. Interestingly, the Trp53/Smad4 loss pancreatic tumor, but not the Trp53/Tgfbr2 loss pancreatic tumor, reveals pancreatic adenosquamous carcinoma (PASC) phenotype. We utilized single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) analysis to identify the distinct tumor immune microenvironment landscape of Trp53/Smad4 loss pancreatic tumors, as compared to that of oncogenic KRAS-driven pancreatic tumors.

Results

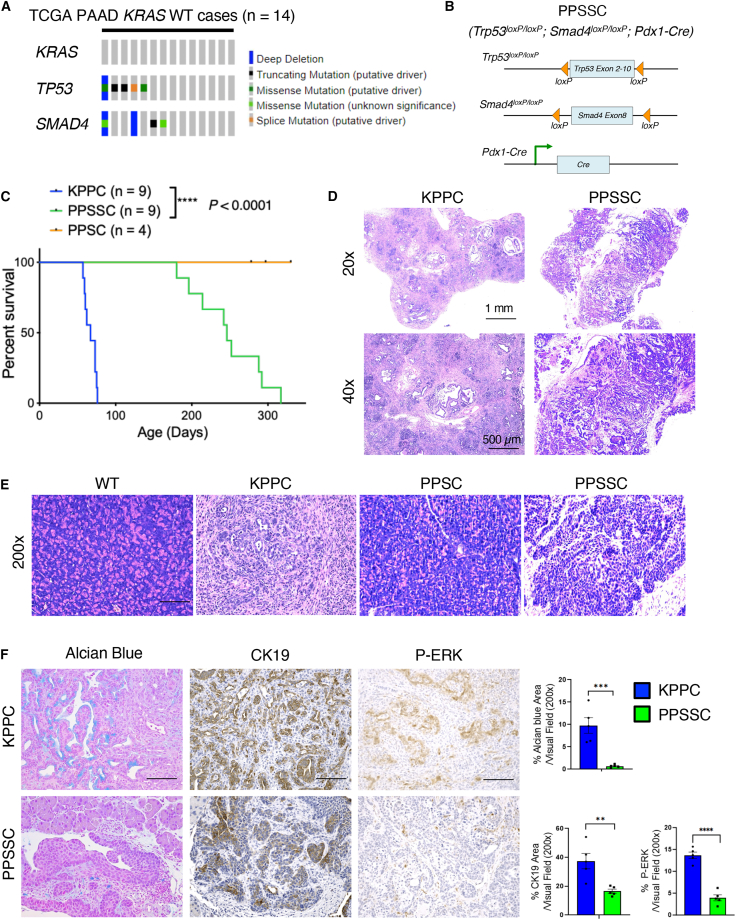

The PPSSC mouse model develops spontaneous pancreatic tumors in the background of KRAS-WT

Pancreatic cancer is predominantly associated with the occurrence of oncogenic KRAS gene mutations in approximately 90% of all cases. However, there are approximately 10% of pancreatic cancer cases harboring KRAS-WT gene. An analysis of The Cancer Genome Atlas dataset revealed that KRAS-WT pancreatic cancer cases often harbor alteration and/or deletion in tumor suppressor genes such as TP53 and SMAD4 (Figure 1A). To further test whether loss of p53 and SMAD4 is sufficient to induce autochthonous pancreatic tumor formation, we generated the PPSSC transgenic mouse model (Figure 1B). Due to the fact that currently there is no other KRAS-WT transgenic mouse model of pancreatic adenocarcinoma, the KPPC mouse model (LSL-KrasG12D;Trp53loxP/loxP;Pdx1-Cre) was used as the best available control group (Figures 1C and 1D). PPSSC mice exhibited significantly slower tumor progression than KPPC mice (Figure 1C). PPSSC mice developed spontaneous pancreatic tumors between 6 and 12 months of age with a median survival of 8 months, as compared to KPPC mice with a median survival of 2.5 months (Figure 1C). Interestingly, PPSSC mice developed adenosquamous subtype tumors, in contrast to the typical adenocarcinoma subtype tumors in KPPC mice (Figure 1D). We confirmed the Pdx1-Cre-driven recombination (conditional knockout) of Smad4 and Trp53 genes, as well as the KRAS-WT status, in the pancreas of PPSSC mice using genotyping PCR assays (Figure S1A). While PPSSC mice develop pancreatic tumors between 6 and 12 months of age, PPSC mice (with homozygous loss of Trp53 and heterozygous loss of Smad4) did not exhibit abnormal histology or tumorigenesis in the pancreas over a 12-month observation period (Figure 1E). Besides the tumor formation in the pancreas, PPSSC mice did not exhibit abnormal histology in other organs (Figure S1B). Additional histological analysis of PPSSC mice revealed the development of pancreatic tumors over time, from 1 to 10 months of age (Figure S2A). Further analyses revealed that PPSSC tumors had significantly lower levels of Alcian blue, cytokeratin-19, and phospho-ERK1/2 (P-ERK) staining than stage-matched KPPC tumors (Figure 1F). In addition, PPSSC tumors exhibited lower levels of type I collagen and CD45, while harboring similar alpha-smooth muscle actin levels, as compared to KPPC tumors (Figure S2B).

Figure 1.

The Trp53loxP/loxP;Smad4loxP/loxP;Pdx1-Cre mouse model develops distinct pancreatic tumors from the LSL-KrasG12D;Trp53loxP/loxP;Pdx1-Cre mouse model

(A) Genetic alterations of TP53 and SMAD4 among patients with wild-type KRAS gene (KRAS-WT) from The Cancer Genome Atlas-Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma (TCGA-PAAD) cohort. Mutation was color-coded for indicated genetic event.

(B) Genetic strategy of pancreatic (Pdx1-lineage)-specific deletion (conditional knockout) of Trp53 and Smad4 using the Trp53loxP/loxP;Smad4loxP/loxP;Pdx1-Cre (PPSSC) mouse model.

(C) Survival of PPSSC mice (n = 9) and LSL-KrasG12D;Trp53loxP/loxP;Pdx1-Cre (KPPC) mice (n = 9). PPSC (Trp53loxP/loxP;Smad4loxP/+;Pdx1-Cre) mice were also shown (n = 4). Log rank (Mantel-Cox) was used.

(D) Overview images of H&E staining for pancreatic tumor sections from PPSSC mice (8-month-old) and KPPC mice (2.5-month-old). See also Figures S1B and S2A.

(E) Representative images of H&E staining for pancreatic tissue sections from indicated mice: PPSSC mice (8-month-old), PPSC mice (8-month-old), and KPPC mice (2.5-month-old). Representative images were shown from each group (n = 5/group).

(F) Pancreatic tumor sections from KPPC mice (2.5-month-old) and stage-matched PPSSC mice (8-month-old) stained for Alcian blue, cytokeratin-19 (CK19), and phospho-ERK1/2 (P-ERK). Representative images were shown from each group (n = 5/group). Staining positivity quantification was shown with Student’s t test. Scale bar: 100 μm. See also Figure S2B. ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

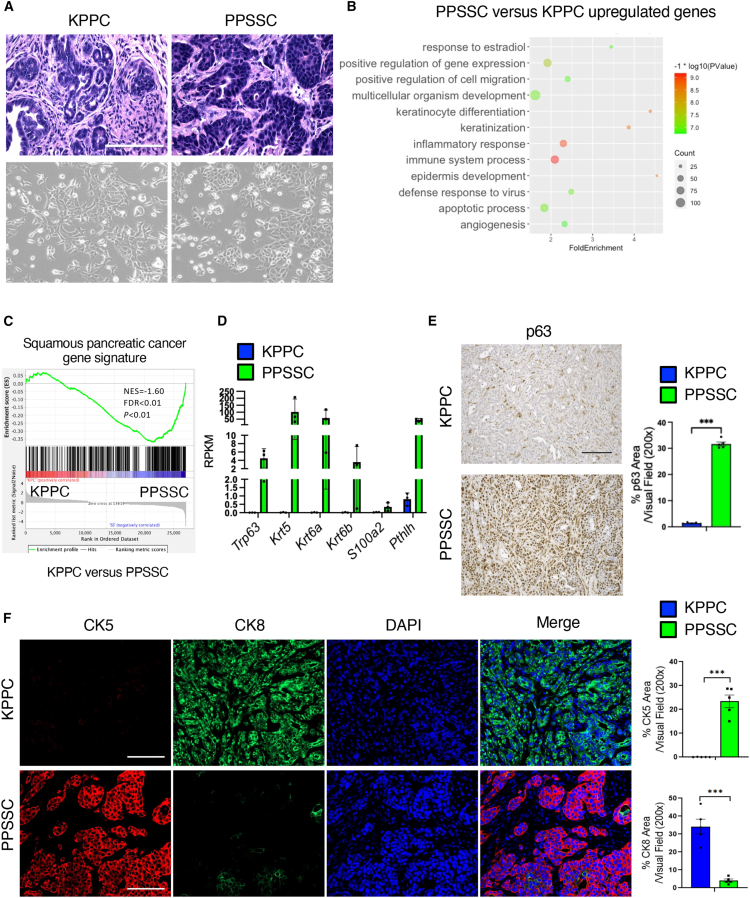

Loss of p53 and SMAD4 induces pancreatic tumorigenesis with adenosquamous carcinoma phenotype

In our previous assays (Figures 1D–1F), we noticed that PPSSC tumors exhibited significantly different histology as compared to KPPC tumors. Further analyses revealed the cancer cells of PPSSC tumors harbor unique adenosquamous carcinoma phenotype, in contrast to the typical adenocarcinoma phenotype observed in cancer cells of KPPC tumors (Figure 2A). Primary cancer cell lines established from PPSSC tumors revealed significant upregulation of keratinization pathway genes associated with squamous differentiation as compared with cancer cell lines from KPPC tumors, based on the bulk RNA sequencing analysis on these cancer cell lines (Figures 2B and 2C). As expected, PPSSC cancer cells harbored significantly elevated levels of squamous genes including Trp63 (encoding p63), Krt5 (encoding CK5), Krt6a/b (encoding CK6), and other squamous signature genes (Figure 2D), consistent with previous definitions.5 Immunohistochemistry staining further validated that PPSSC tumors had significantly higher p63 level than KPPC tumors (Figure 2E). In addition, PPSSC tumors exhibited significantly higher CK5 level and lower CK8 level than KPPC tumors, further confirming the squamous phenotype of PPSSC tumors (Figure 2F). Our observations on the PPSSC tumor model are consistent with recent studies showing the squamous phenotype of a commonly used human pancreatic cancer cell line BxPC3, harboring TP53 mutation and SMAD4 loss in the background of KRAS-WT.16

Figure 2.

Loss of p53 and SMAD4 induces pancreatic tumor formation with unique adenosquamous carcinoma features

(A) Representative images of H&E staining on tumor sections from KPPC mice (2.5-month-old) and stage-matched PPSSC mice (8-month-old), in comparison with representative images of primary cancer cell lines established from KPPC and PPSSC tumors. Scale bar: 100 μm.

(B) Top enriched biological process pathways by gene ontology analysis for the upregulated genes in PPSSC cancer cells, as compared to KPPC cancer cells.

(C) Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) of RNA-seq data on KPPC and PPSSC cancer cell lines. Squamous pancreatic cancer signature genes were enriched in PPSSC cancer cells, as compared with KPPC cancer cells.

(D) The expression levels of featured genes from squamous pancreatic cancer signature in KPPC and PPSSC cancer cells.

(E) Representative images of immunohistochemistry staining of p63 on tumor sections from KPPC mice (2.5-month-old) and stage-matched PPSSC (8-month-old) mice (n = 5/group). Quantitative results were shown with Student’s t test. Scale bar: 100 μm. ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

(F) Representative images of immunofluorescence staining for CK5 (red), CK8 (green), and nuclei/DAPI (blue) on tumor sections from KPPC mice (2.5-month-old) and PPSSC mice (8-month-old) (n = 5/group). Quantitative results were shown with Student’s t test. Scale bar: 100 μm. ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

The adenosquamous carcinoma phenotype of PPSSC model is correlated with p63 upregulation

Many previous studies identified p63 as a master regulator of squamous differentiation.16,17,18,19 Therefore, we conducted additional assays and identified that PPSSC cancer cells exhibited higher levels of both p63 protein and ΔNp63 transcript (the oncogenic form of p63), while the level of TAp63 isoform transcript remained unchanged, as compared to KPPC cancer cells (Figures 3A and 3B). Knockdown of Trp63 by small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) significantly inhibited the cell viability of PPSSC cancer cells (Figures 3C and 3D). Next, we sought to address how Smad4 deficiency results in Trp63 upregulation. Previous studies showed that Notch1 downregulation contributes to the squamous neoplasm development, while Notch1 suppresses p63 expression by downregulating interferon-responsive factors (IRFs), such as IRF7 and IRF3, that bind to the IRF-binding sites in the ΔNp63 promoters.20,21 Consistently, Notch1 downregulation was observed in PPSSC cancer cells, while Notch2 level remained unaltered, as compared with KPPC cancer cells (Figure 3E). We also observed that Irf7 and the interferon-induced gene Ifit1 were upregulated in PPSSC cancer cells (Figure 3F). Consistently, gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) on the bulk RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) data of PPSSC cancer cells validated that the interferon-α/γ signaling pathways were enriched in PPSSC cancer cells, as compared to KPPC cancer cells (Figure 3G). Furthermore, PPSSC cancer cells exhibited higher expression levels of Cebpd (encoding C/EBPδ) and Cebpg (encoding C/EBPγ) than KPPC cancer cells, while Cebpa and Cebpb levels were similar between PPSSC and KPPC cancer cells (Figure 3H). These results are consistent with the previous report showing that C/EBPδ can bind to and activate the ΔNp63 promoter directly.22 Furthermore, we observed a significant decrease in ΔNp63 transcript levels in PPSSC cancer cells transfected with a vector of SMAD4 expression, as compared to PPSSC cells transfected with a control vector (Figure S3A). Taken together, our results indicated that PPSSC cancer cells upregulate p63 due to the downregulation of Notch1, as well as the upregulation of Irf7 and Cebpd.

Figure 3.

The upregulation and function of p63 in PPSSC cancer cells with adenosquamous phenotype

(A) Detection of p63 and CK5 in KPPC and PPSSC cancer cell lines by western blot assay.

(B) Quantitative reverse-transcription PCR (qRT-PCR) analysis of TAp63 and ΔNp63 expression in KPPC and PPSSC cancer cells (n = 3 biological replicates). Gene expression levels were compared with Student’s t test.

(C) Cell viability of KPPC and PPSSC cancer cell lines (n = 3 biological replicates) after transfection with siRNA-Trp63 (si-Trp63) or non-targeting siRNA-control (si-Ctrl). Cell viability was presented as a percentage normalized to the si-Ctrl group and compared with Student’s t test.

(D) Detection of p63 by western blot assay in KPPC and PPSSC cancer cell lines transfected with indicated siRNAs.

(E and F) qRT-PCR analysis of Notch1/Notch2 (E) or Irf3/Irf7/Ifit1 (F) expression in KPPC and PPSSC cancer cells (n = 3 biological replicates). Gene expression levels were compared with one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test.

(G) GSEA results of RNA-seq data on KPPC and PPSSC cancer cell lines. Interferon-α and interferon-γ pathway genes were enriched in PPSSC cancer cells, as compared with KPPC cancer cells.

(H) qRT-PCR analysis of Cebpa, Cebpb, Cebpg, and Cebpd expression in KPPC and PPSSC cancer cells (n = 3 biological replicates). Gene expression levels were compared with one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test.

(I) Schematic of syngeneic orthotopic pancreatic tumor formation experiments in C57BL/6J mice using KPPC and PPSSC cancer cells. Tumor-bearing mice were sacrificed for further analysis at 2 months after orthotopic implantation of cancer cells.

(J) Representative images of H&E staining and p63 immunohistochemistry staining on KPPC and PPSSC orthotopic pancreatic tumor sections (n = 5/group). KPPC pancreatic tumors were collected 1 month after orthotopic injection, while PPSSC pancreatic tumors were collected 2 months after orthotopic injection. Scale bar: 100 μm. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01. See also Figures S3B and S3C.

To explore whether PPSSC cancer cells maintain their unique squamous phenotype in vivo, we established a syngeneic (orthotopic) pancreatic tumor mouse model by orthotopically injecting PPSSC cancer cells into the pancreas of C57BL/6 mice (Figure 3I). PPSSC cancer cells were able to form pancreatic tumors preserving the adenosquamous carcinoma histology (Figure 3I), identical to the spontaneous pancreatic tumors from PPSSC transgenic mice. Consistently, the orthotopic PPSSC tumors also preserved high expression levels of CK5 and p63, in contrast to low CK8 expression (Figures 3J, S3B, and S3C). These results suggested that PPSSC cancer cells consistently exhibit adenosquamous characteristics in vitro and in vivo.

Loss of p53 and SMAD4 in PPSSC cancer cells is not associated with mesenchymal or basal-like phenotype

Next, we queried whether the PPSSC cancer cells might harbor mesenchymal or basal-like phenotype, in addition to the adenosquamous phenotype. GSEA results revealed that the epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) pathway was downregulated in PPSSC cancer cells, as compared with KPPC cancer cells (Figure S4A). EMT signature genes such as Cdh2 (encoding N-cadherin), Vim (encoding vimentin), and genes encoding EMT transcriptional factors (including Snal1, Snal2, Zeb1, Zeb2, and Tcf3) were downregulated in PPSSC cancer cells, while the epithelial-subtype marker gene Cdh1 (encoding E-cadherin) was upregulated (Figures S4B and S4C). Immunohistochemistry staining results further validated that the spontaneous pancreatic tumors from PPSSC mice possessed a higher E-cadherin level and lower levels of vimentin/ZEB1, as compared to KPPC tumors (Figure S4D). Moreover, the transwell migration assay indicated that PPSSC cancer cells exhibited lower migration capability than KPPC cancer cells (Figure S4E).

Recent studies have established that pancreatic cancer cases can be classified into multiple subtypes, such as the basal-like subtype and classical subtype.5,23,24,25 We examined the expression of 11 basal-like subtype signature genes and 11 classical subtype signature genes to compare the KPPC and PPSSC cancer cells. However, the expression profiles of basal-like subtype and classical subtype genes were not significantly different between KPPC and PPSSC cancer cells (Figures S5A and S5B).

In addition, we compared the cell proliferation rate between PPSSC and KPPC cancer cell lines. PPSSC cancer cells exhibited a lower proliferation rate than KPPC cancer cells (Figure S6A). Due to the absence of the oncogenic KRASG12D driver mutation, PPSSC cancer cells were resistant to the treatment of KRASG12D inhibitor MRTX1133 (Figure S6B), a potent drug candidate being widely evaluated in the context of pancreatic cancer.26,27,28 In contrast, the KPPC cancer cells were sensitive to MRTX1133 treatment (Figure S6B). P-ERK, a downstream signal induced by oncogenic KRASG12D, was significantly reduced by MRTX1133 treatment in KPPC cancer cells, but not in PPSSC cancer cells (Figure S6C). Consistently, PPSSC cancer cells were also resistant to the inhibitor of MEK, another key mediator of the oncogenic KRASG12D signaling pathway, while KPPC cancer cells were sensitive to MEK inhibitor treatment (Figure S6D). Furthermore, we conducted an additional assay to examine the sensitivity of KPPC and PPSSC cancer cell lines to the treatment of multiple agents, including YAP inhibitor (verteporfin), STAT3 inhibitor (niclosamide), PARP inhibitor (olaparib), BET inhibitor (JQ1), AKT inhibitor (MK-2206), DDR1 inhibitor (7RH), FAK inhibitor (VS-4718), mTOR inhibitor (rapamycin), ferroptosis inducers (RSL3 and erastin), and gemcitabine, all of which showed similar effects on KPPC and PPSSC cancer cell lines (Figures S6E–S6O).

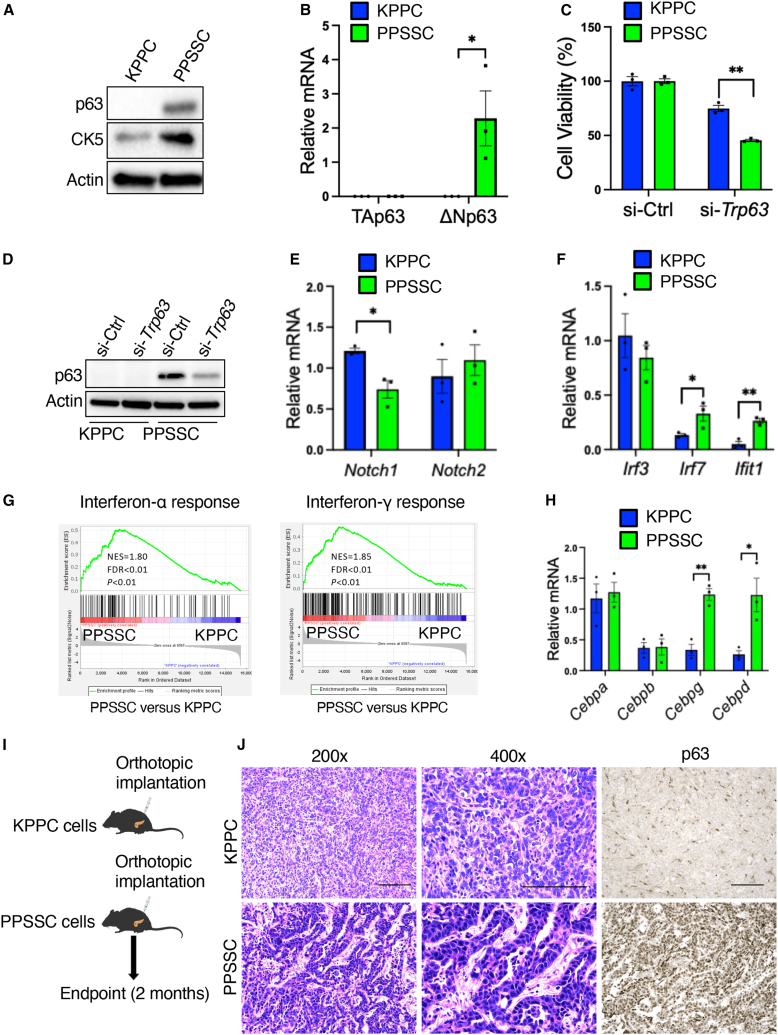

Another mouse model (PPTTC) with a loss of p53 and TGFBR2 also develops spontaneous pancreatic tumors in the absence of the oncogenic KRAS mutation

Given the close association between SMAD4 and TGFBR2 in pancreatic cancer, we next queried whether loss of p53 and TGFBR2 could also induce pancreatic tumor formation, similar to that induced by loss of p53 and SMAD4. We established the PPTTC mouse model (Figure 4A), which developed spontaneous pancreatic tumors between 8 and 12 months of age with a median survival of 9 months, while the Trp53loxP/loxP;Tgfbr2loxP/+;Pdx1-Cre control mice harboring homozygous loss of Trp53 and heterozygous loss of Smad4 did not exhibit abnormal histology or tumorigenesis in the pancreas over a 12-month observation period (Figure 4B). Interestingly, both PPSSC and PPTTC tumors showed minimal signs of pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PanIN), as shown by both H&E staining and Alcian blue staining (Figure 4C). In contrast, oncogenic KRASG12D-driven transgenic mouse models, including KPPC model, KSSC (LSL-KrasG12D;Smad4loxP/loxP;Pdx1-Cre) model, KTTC (LSL-KrasG12D;Tgfbr2loxP/loxP;Pdx1-Cre) model, and KPR172HC (LSL-KrasG12D;LSL-Trp53R172H;Pdx1-Cre) model, ubiquitously exhibited prominent signs of PanIN and adenocarcinoma phenotypes (Figure 4C). Additional histology examinations identified that the pancreatic tumors from PPTTC mice exhibited poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma phenotype (Figures 4C and S7), which was different from the adenosquamous carcinoma phenotype of PPSSC tumors. Immunohistochemistry staining for CK5, CK8, and p63 further demonstrated that the tumor phenotype of PPTTC model (CK5low/CK8medium/p63low) was different from that of either PPSSC model (CK5high/CK8low/p63high) or KRASG12D-driven models (CK5low/CK8high/p63low) such as KPPC, KSSC, KTTC, and KPR172HC (Figure 4D). The genotypes and tumor phenotypes between PPTTC, PPSSC, KPPC, KSSC, KTTC, and KPR172HC mouse models were summarized in Figure 4E. Taken together, these observations indicated that both p53/SMAD4 loss and p53/TGFBR2 loss (in our PPSSC and PPTTC mouse models, respectively) are sufficient to induce spontaneous KRAS-WT pancreatic tumor formation. Both PPSSC and PPTTC mouse models exhibited distinct tumor histological features from the conventional KRASG12D-driven transgenic mouse models (KPPC, KSSC, KTTC, or KPR172HC). Interestingly, the histological feature of PPSSC tumors was not completely the same as that of PPTTC tumors, suggesting the different tumor development trajectories caused by SMAD4 loss and TGFBR2 loss.

Figure 4.

Loss of p53 and TGFBR2 in the PPTTC mouse model also induces autochthonous pancreatic tumor formation

(A) Genetic strategy of pancreatic (Pdx1-lineage)-specific deletion (conditional knockout) of Tgfbr2 and Trp53 using the PPTTC mouse model.

(B) Survival of PPTTC mice (n = 4). PPTC (Trp53loxP/loxP;Tgfbr2loxP/+;Pdx1-Cre) mice were also shown (n = 4). Log rank (Mantel-Cox) was used.

(C) Representative images of H&E and Alcian blue staining on tumor sections from indicated mouse models (n = 5/group): PPSSC mice (8-month-old), PPTTC mice (9-month-old), KPPC mice (2.5-month-old), KSSC mice (4-month-old), KTTC mice (4-month-old), and KPR172HC mice (5-month-old). Scale bar: 100 μm. See also Figure S7.

(D) Representative images of immunohistochemistry staining of CK5, CK8, and p63 on tumor sections from indicated genotype mice (n = 5/group): PPSSC mice (8-month-old), PPTTC mice (9-month-old), KPPC mice (2.5-month-old), KSSC mice (4-month-old), KTTC mice (4-month-old), and KPR172HC mice (5-month-old). Scale bar: 100 μm.

(E) Summary of genotypes and phenotypes of indicated mouse models.

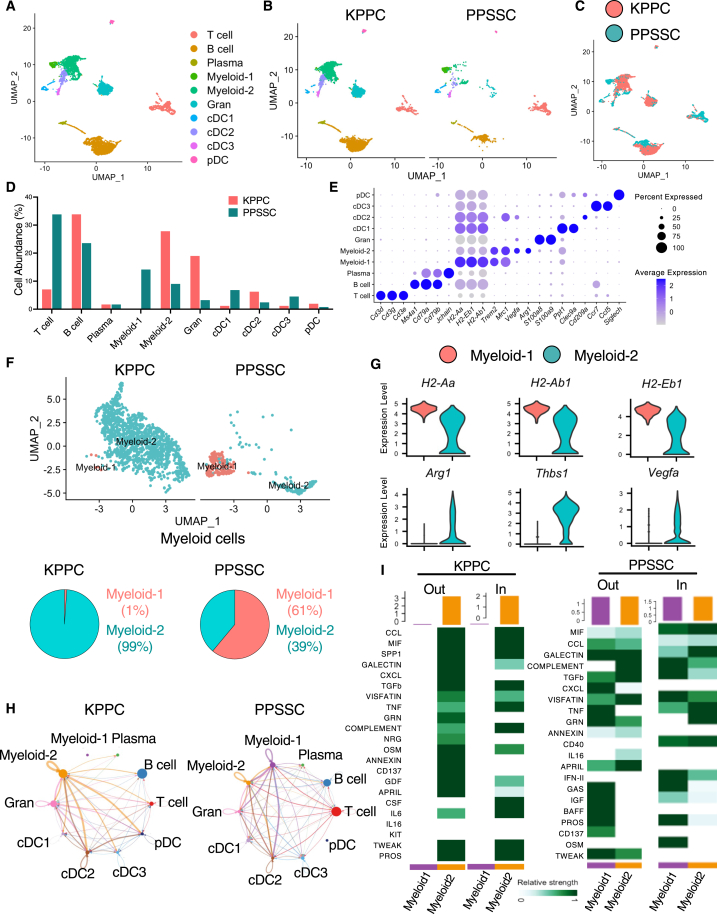

scRNA-seq analysis reveals the unique tumor immune microenvironment in PPSSC pancreatic tumors

Based on our previous results showing the unique tumor phenotypes of PPSSC model (Figures 2 and 3), we queried whether such phenotypes could influence the tumor immune microenvironment. We conducted scRNA-seq analysis to examine the total immune cells from the spontaneous tumors of PPSSC mice (Figure 5A). The major immune cell populations in PPSSC tumors revealed significantly different profiles and compositions as compared to those in KPPC tumors (Figures 5B and 5C). Specifically, PPSSC tumors harbored more T cells and “myeloid-1” subtype myeloid cells, while exhibiting less “myeloid-2” subtype myeloid cells (Figure 5D). The myeloid-1 subtype and myeloid-2 subtype exhibited different gene expression profiles (Figure S8). Signature genes of myeloid-1 subpopulations included the major histocompatibility complex class II (MHCII) genes, such as H2-Aa, H2-Ab1, and H2-Eb1 (Figure 5E). Signature genes of myeloid-2 subpopulations included Arg1, Thbs1, and Vegfa, associated with the immunosuppressive “M2-like” macrophage phenotype (Figure 5E). A direct comparison of the cell compositions and signature gene profiles between myeloid-1 and myeloid-2 subpopulations also confirmed that the enriched myeloid-1 subcluster in PPSSC tumors highly expressed MHCII genes, in contrast to the enriched myeloid-2 subcluster in KPPC tumors with high expression of Arg1, Thbs1, and Vegfa (Figures 5F and 5G). The cell-cell interaction network in PPSSC tumors, as shown by the CellChat algorithm,29 exhibited significantly diminished crosstalk from the myeloid-2 subcluster to other immune cell populations, while the crosstalk from the myeloid-1 subcluster and T cells to other immune cells was enhanced (Figures 5H, 5I, and S9).

Figure 5.

Single-cell RNA sequencing analysis reveals distinct immune cell compositions between KPPC and PPSSC pancreatic tumors

(A) Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) analysis of live CD45+ immune cell mixture from KPPC and PPSSC tumors. The major immune cell clusters were shown in the uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP) plot.

(B and C) UMAP plot comparing the immune cell compositions between KPPC and PPSSC tumors (B). UMAP distributions of immune cell clusters were also compared between KPPC and PPSSC tumors (C).

(D) Comparison of the relative abundance (%) of various immune cell clusters between KPPC and PPSSC tumors.

(E) Dot plot showing the expression profiles of representative marker genes for indicated cell clusters.

(F) Myeloid cells from KPPC and PPSSC groups were stratified into two distinct subclusters, myeloid-1 and myeloid-2, in the UMAP plot. The abundance (%) of myeloid-1 and myeloid-2 subclusters was also shown in the pie chart.

(G) Expression profiles of signature genes for the two myeloid subpopulations, shown as violin plots.

(H) The cell-cell communication network across indicated immune cell subclusters was calculated and visualized using a circular plot.

(I) The communication levels of cytokine-mediated outgoing (Out) or incoming (In) signaling pathways associated with myeloid-1 and myeloid-2 subclusters in KPPC tumors and PPSSC tumors. See also Figure S8.

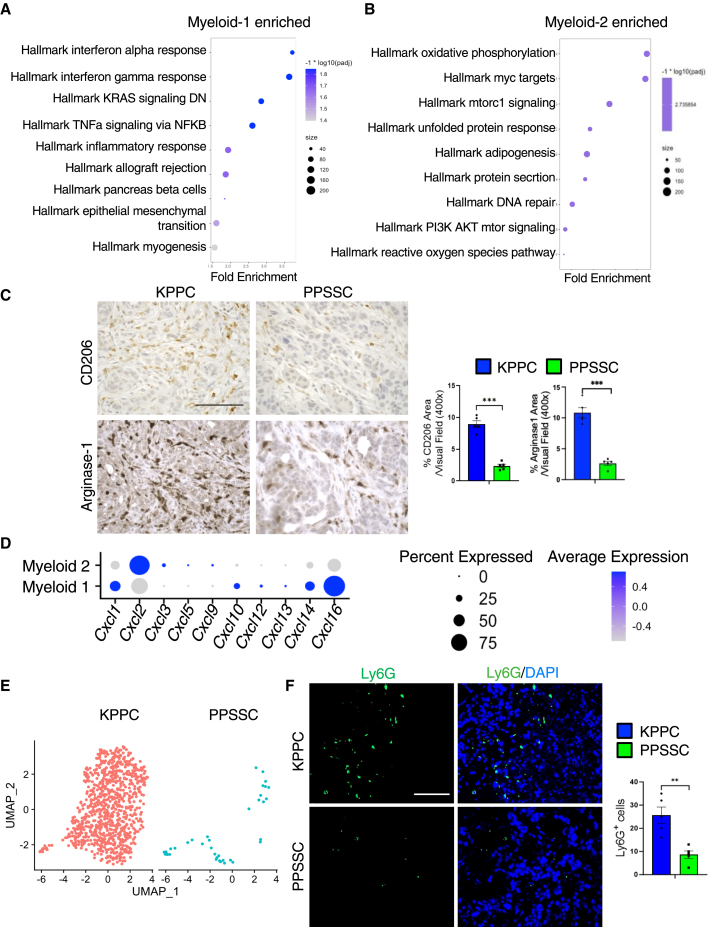

GSEA results identified that the enriched myeloid-1 subcluster in PPSSC tumors exhibited upregulation of interferon-related pathways, indicating the enhanced immune-stimulatory functions of this subcluster (Figure 6A). In contrast, the myeloid-2 subcluster exhibited upregulation of genes associated with oxidative phosphorylation and MYC target pathways (Figure 6B). Consistent with our previous observations (Figures 5E–5G), immunohistochemistry staining also validated the decreased levels of myeloid-2 subcluster markers such as CD206 (encoded by Mrc1) and Arginase-1 (encoded by Arg1) in PPSSC tumors, as compared to KPPC tumors (Figure 6C). In addition, we assessed the expression of chemokine CXC-motif ligand (CXCL) genes in the myeloid-1 subtype and myeloid-2 subtypes. Cxcl2 was highly expressed in the myeloid-2 subtype, while Cxcl16 was enriched in the myeloid-1 subtype (Figure 6D). Since CXCL2 is a key factor for granulocyte/neutrophil recruitment by binding to CXCR2, we then compared the presence of granulocytes between KPPC and PPSSC tumors. As expected, PPSSC tumors exhibited a significantly decreased number of granulocytes, as shown by scRNA-seq and immunofluorescence staining assays (Figures 6E and 6F), consistent with the decreased number of CXCL2-expressing myeloid-2 cells in PPSSC tumors.

Figure 6.

Different compositions of myeloid cells and granulocytes between KPPC and PPSSC tumors

(A and B) GSEA results showing the enriched/upregulated pathways in the myeloid-1 subtype cells (A) or myeloid-2 subtype cells (B). The top enriched pathways based on GSEA were visualized in the dot plots.

(C) Representative images of immunohistochemistry staining for CD206 and Arginase-1 on pancreatic tumor sections from KPPC mice (2.5-month-old) and stage-matched PPSSC mice (8-month-old) (n = 5/group). Quantitative results were shown with Student’s t test. Scale bar: 100 μm. ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

(D) The myeloid subpopulations were examined for the expression profiles of CXCL family genes, as shown in the dot plot.

(E) Granulocyte compositions in KPPC and PPSSC tumors compared in the UMAP plot.

(F) Representative images of immunofluorescence staining for Ly6G (green) and nuclei/DAPI (blue) on tumor sections from KPPC mice (2.5-month-old) and stage-matched PPSSC mice (8-month-old) (n = 5/group). Quantitative results were shown with Student’s t test. Scale bar: 100 μm. ∗∗p < 0.01.

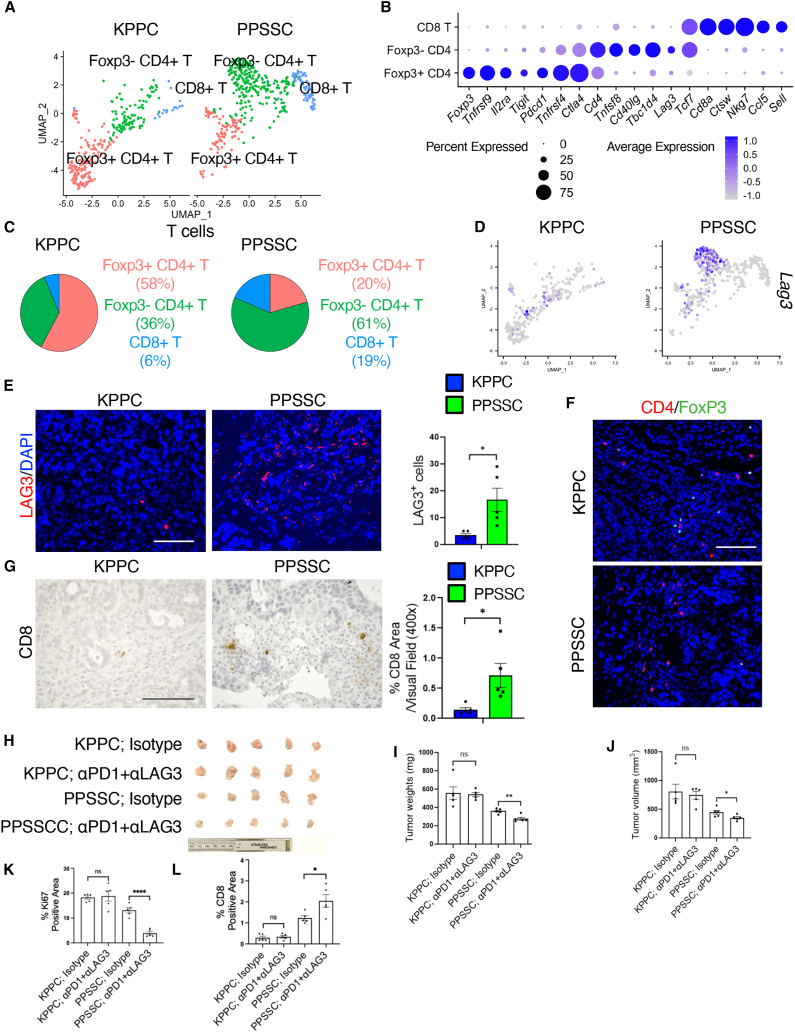

Distinct T cell composition in KRAS-WT pancreatic tumors enhances the efficacy of anti-LAG3 and anti-PD-1 immunotherapy

Next, we compared the T cell profiles between PPSSC and KPPC tumors (Figure 7A). T cells were classified into three subtypes: FoxP3+CD4+ regulatory T (Treg) cells, FoxP3−CD4+ effector T (Teff) cells, and CD8+ T cells (Figure 7B). The signature genes of FoxP3+CD4+ T cells included Foxp3 and Pdcd1 (encoding PD-1). The signature genes of FoxP3−CD4+ T cells included Lag3 and Cd40lg. PPSSC tumors harbored significantly more FoxP3−CD4+ Teff cells and CD8+ T cells, while having less FoxP3+CD4+ Treg cells, as compared with KPPC tumors (Figure 7C). In particular, PPSSC tumors exhibited the enrichment of Lag3-high T cells, which belonged to the FoxP3−CD4+ Teff cells (Figure 7D). The increased numbers of LAG3+ T cells, FoxP3−CD4+ T cells, and CD8+ T cells in PPSSC tumors were also validated by immunohistochemistry and immunofluorescence staining (Figures 7E–7G, S10A, and S10B). Further analysis revealed the different correlations between Cd8a and other T cell-related genes in PPSSC tumors, as compared with KPPC tumors (Figure S10C). The enriched FoxP3−CD4+ and LAG3+ T cells in PPSSC tumors prompted us to examine the possibility of utilizing combination immunotherapy to enhance the antitumor effect of these T cells. An orthotopic pancreatic tumor model was established using the inoculation of PPSSC or KPPC cancer cells into the pancreas of C57BL/6 mice. The PPSSC tumor-bearing mice exhibited a significantly improved response to the combined immunotherapy of anti-LAG3 and anti-PD-1 neutralizing antibodies, while the KPPC tumor-bearing mice showed minimal response (Figures 7H–7J). Furthermore, our histology and immunohistochemistry/immunofluorescence assessment showed that the treatment of anti-LAG3 plus anti-PD-1 neutralizing antibodies reduced Ki67 levels, while increasing CD8+ T cells and CD4+/FoxP3− T cells in PPSSC tumors, as compared with KPPC tumors (Figures 7K–7L, S10D, and S10E).

Figure 7.

The unique T cell composition in PPSSC tumors results in enhanced efficacy of anti-LAG3 and anti-PD-1 immunotherapy

(A) T cells from KPPC and PPSSC tumors were classified into indicated subclusters: FoxP3+CD4+ regulatory T (Treg) cells, FoxP3−CD4+ effector T (Teff) cells, and CD8+ T cells, as shown in the UMAP plot.

(B) The expression profiles of signature genes of indicated T cell subclusters were depicted in the dot plot.

(C) The abundance (%) of indicated T cell subclusters from KPPC and PPSSC tumors was shown in the pie charts.

(D) The expression profile of Lag3 in KPPC and PPSSC tumors, as compared in the UMAP plot.

(E and F) Representative images of immunofluorescence staining for LAG3 (E), CD4 and FoxP3 (F), and nuclei/DAPI on tumor sections from KPPC mice (2.5-month-old) and stage-matched PPSSC mice (8-month-old) (n = 5/group). Quantitative results were shown with Student’s t test. Scale bar: 100 μm. ∗p < 0.05. See also Figures S10A and S10B.

(G) Representative images of CD8 immunohistochemistry staining on pancreatic tumor sections from KPPC mice (2.5-month-old) and stage-matched PPSSC mice (8-month-old) (n = 5/group). Quantitative results were shown with Student’s t test. Scale bar: 100 μm. ∗p < 0.05.

(H) Demonstration of endpoint pancreatic tumors from mice with indicated treatments.

(I and J) The endpoint tumor weight (I) and volume (J) of mice with indicated treatments (n = 5/group). Data were shown using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01. ns: not significant.

(K and L) Staining positivity quantification of Ki67 cells (K) and CD8+ cells (L) in orthotopic pancreatic tumors with indicated treatments. Data were shown using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test (n = 5/group). ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001. ns: not significant. See also Figure S10D.

Taken together, our findings reveal that the combination of anti-LAG3 and anti-PD-1 neutralizing antibodies suppresses the PPSSC tumor progression, indicating the potential application of this combined immunotherapy for KRAS-WT pancreatic cancer.

Discussion

Pancreatic cancer is the third leading cause of cancer-related death in the United States. A significant proportion, approximately 90%, of total pancreatic cancer cases are associated with the oncogenic KRAS mutations. In addition, genetic alterations in tumor suppressor genes, such as TP53, CDKN2A, and SMAD4, are also frequently observed among pancreatic cancer cases. To investigate the mechanisms of tumor formation induced by oncogenic KRAS, genetically engineered mouse models harboring oncogenic KRAS mutation-driven spontaneous pancreatic tumors have been widely utilized. Our recent studies established a variety of transgenic mouse models with pancreatic tumors, all of which were driven by oncogenic KRAS mutation in combination with tumor suppressor gene alterations.30,31,32,33

A non-negligible proportion of pancreatic tumors harbor KRAS-WT, which are often associated with genetic alterations of TP53 (mutation) or BRAF (mutation or gene fusions).8,9,10,11,12 However, genetically engineered mouse models for KRAS-WT pancreatic cancer are still lacking. Furthermore, it remains unclear whether the loss of major tumor suppressor genes could induce pancreatic tumor formation without oncogenic KRAS mutation. In this study, we established genetically engineered mouse models that spontaneously develop KRAS-WT pancreatic cancer. Both Trp53/Smad4 loss (Trp53loxP/loxP;Smad4loxP/loxP;Pdx1-Cre: PPSSC mouse model) and Trp53/Tgfbr2 loss (Trp53loxP/loxP;Tgfbr2loxP/loxP;Pdx1-Cre: PPTTC mouse model) are sufficient to induce autochthonous pancreatic tumor formation in the background of KRAS-WT. Our transgenic mouse models (PPSSC and PPTTC) and related cancer cell lines represent valuable model systems of pancreatic cancer that are evolutionarily independent of oncogenic KRAS, in contrast to oncogenic KRAS-driven transgenic mouse models such as KPPC (LSL-KrasG12D;Trp53loxP/loxP;Pdx1-Cre) and KPR172HC (LSL-KrasG12D;LSL-Trp53R172H;Pdx1-Cre).

PASC is a relatively rare subtype of pancreatic cancer compared to pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) in human patients. Both PASC and PDAC commonly harbor KRAS mutations and exhibit similar genomic variations, suggesting that they may originate from the same progenitor cells during pancreatic cancer development.12 PASC exhibits a higher prevalence of TP53 mutations compared to PDAC, indicating a potential role of the p53 pathway in PASC differentiation. Oncogenic KRAS mutations can accelerate pancreatic tumor development, but do not seem to directly contribute to preferential differentiation into PDAC or PASC.10,11,12 Further studies are still required to elucidate the distinct contributions of various genetic alterations in KRAS and TP53 to the development of PASC or PDAC. Interestingly, the PPSSC mouse model, harboring Trp53/Smad4 loss, develops spontaneous tumors with a unique PASC phenotype. The PPSSC mouse model uniquely develops pancreatic tumors with a predominant adenosquamous carcinoma phenotype. In this study, we examined the unique transcriptomic profiles and phenotypic features of PPSSC cancer cells, as compared with KPPC cancer cells harboring oncogenic KRASG12D mutation. We identified the important role of p63 and related factors in the development of adenosquamous pancreatic tumors in the PPSSC mouse model. Our study revealed that the PPSSC mouse model with PASC exhibited increased p63 expression. However, the precise molecular mechanisms by which SMAD4 loss results in p63 upregulation require further investigations.

In this study, we utilized scRNA-seq analysis to compare the tumor immune microenvironment between PPSSC and KPPC tumors, revealing the unique myeloid cell and T cell compositions in PPSSC tumors. The alterations in immune cells, especially T cells, provide opportunities for anti-LAG3 and anti-PD-1 immune checkpoint blockade in PPSSC tumors. In future investigations, it would also be intriguing to further examine whether the PPSSC pancreatic tumors may have distinct features in other aspects such as tumor metabolism, microbiome, and metastasis, as compared with oncogenic KRAS-driven pancreatic tumor models.

In addition, the PPTTC mouse model, harboring Trp53/Tgfbr2 loss, can also develop spontaneous pancreatic tumors in the background of KRAS-WT. Both PPSSC tumors and PPTTC tumors exhibit tumor histological features that are different from oncogenic KRAS-driven mouse models such as KPPC, KSSC, and KTTC. These two models are complementary in supporting the critical role of the SMAD4-TGFBR2 pathway in suppressing pancreatic tumor initiation. Nevertheless, a more careful examination revealed that the tumor phenotype of the PPTTC mouse model is not entirely the same as that of the PPSSC mouse model. PPSSC pancreatic tumors exhibited adenosquamous carcinoma phenotypes, while PPTTC pancreatic tumors exhibited poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma phenotypes. More investigations are still needed to further delineate the mechanism by which SMAD4 loss and TGFBR2 loss differentially regulate the tumorigenesis in the context of KRAS-WT pancreatic cancer.

Taken together, this study established two transgenic mouse models of spontaneous pancreatic cancer in the context of KRAS-WT. PPSSC (with KRAS-WT and loss of Trp53/Smad4) and PPTTC (with KRAS-WT and loss of Trp53/Tgfbr2) mouse models develop autochthonous pancreatic tumors with distinct histological phenotypes. PPSSC pancreatic tumors exhibit unique adenosquamous carcinoma features. Single-cell analysis identifies the unique compositions and transcriptomic profiles of immune cell populations in the PPSSC pancreatic tumors, with indications for the development of potential therapeutic approaches.

Limitations of the study

It is noteworthy that the KRAS-WT pancreatic cancer cases in human patients are not directly associated with adenosquamous subtype.11 This discrepancy suggests a potential limitation of the PPSSC mouse model with predominant adenosquamous KRAS-WT pancreatic cancer, differing from most KRAS-WT human pancreatic cancer cases with adenocarcinoma phenotype. The mechanism by which PPSSC mouse model predominantly develops adenosquamous subtype of pancreatic cancer remains unclear. Interestingly, this phenotype coincides with the squamous-like characteristics observed in the widely used human pancreatic cancer cell line BxPC3 also harboring KRAS-WT and loss of SMAD4.19 Future investigations using PPSSC and PPTTC mouse models are still needed to further elucidate the alternative tumorigenic mechanisms and differentiation trajectories in the absence of oncogenic KRAS mutations. Nevertheless, the PPSSC mouse model can still serve as a useful tool for the study of adenosquamous subtype pancreatic cancer. Our results demonstrate that combined treatment with anti-PD-1 and anti-LAG3 inhibits PPSSC tumor growth in an orthotopic pancreatic tumor mouse model. However, the efficacy of this combination therapy needs further validation in additional preclinical studies, while tumor growth should be carefully monitored longitudinally at various time points during the treatment process using bioluminescence or magnetic resonance imaging techniques.

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further information and requests for reagents may be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Yang Chen (ychen23@mdanderson.org).

Materials availability

This study did not generate any unique reagents.

Data and code availability

Bulk RNA-seq and single-cell RNA-seq data were deposited in GEO and publicly available as of the date of publication. The accession numbers are: GSE268896 and GSE268899. This paper does not generate any original codes. Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this work paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the MDACC Start-Up Funding, The University of Texas System Rising STARs Award, the MDACC Division of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine Research Grant Program, and the MDACC SPORE in Gastrointestinal Cancer Grant P50 CA221707 Career Enhancement Program (CEP) Award. The flow cytometry assays were performed in the Flow Cytometry & Cellular Imaging Facility, which is supported in part by the National Institutes of Health through MD Anderson Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA016672. The single-cell RNA sequencing assays were performed in the Advanced Technology Genomics Core Facility of MDACC. The bulk RNA sequencing dataset was generated in the UTHealth Cancer Genomics Core funded by the Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas (CPRIT) grant (RP180734).

Author contributions

Conceptualization, Y.C.; data curation, Y.C., D.Y., and X.S.; formal analysis, Y.C., D.Y., and X.S.; methodology, Y.C., D.Y., and X.S.; investigation, D.Y., X.S., R.M., Hua Wang, C.C., and Z.Z.; resources, Y.C.; supervision, Y.C., I.I.W., Huamin Wang, and A.M.; validation, Y.C. and D.Y.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

STAR★Methods

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Rabbit CK19 | Abcam | Cat# ab52625, RRID: AB_2281020 |

| Rabbit Ki67 | Abcam | Cat# ab15580, RRID: AB_443209 |

| Goat Col1 | SouthernBiotech | Cat# 1310-01, RRID: AB_2753206 |

| Mouse αSMA | DAKO | Cat# M0851, RRID: AB_2223500 |

| Rabbit CD4 | Abcam | Cat# ab183685, RRID: AB_2686917 |

| Rabbit CD8 | Cell Signaling | Cat# 85336S, RRID: AB_2800052 |

| Rabbit Arginase 1 | Abcam | Cat# ab91279, RRID: AB_10674215 |

| Rabbit CD45 | Cell Signaling | Cat# 70257, RRID: AB_2799780 |

| Rat CK8 | Sigma | Cat# MABT329, RRID: AB_2891089 |

| Rabbit Cadherin 1 | Cell Signaling | Cat# 3195, RRID: AB_2291471 |

| Rabbit Vimentin | Cell Signaling | Cat# 5741, RRID: AB_10695459 |

| Rabbit ZEB1 | Novus Biological | Cat# NBP1-05987, RRID: AB_1556166 |

| Rabbit phospho-ERK1/2 | Cell Signaling | Cat# 9101S, RRID: AB_331646 |

| Rabbit ERK | Cell Signaling | Cat# 9102, RRID: AB_330744 |

| Rabbit Cleaved Caspase-3 | Cell Signaling | Cat# 9664S, RRID: AB_2070042 |

| Rabbit p63 | Abcam | Cat# ab124762, RRID: AB_10971840 |

| Rabbit β-actin | Cell Signaling | Cat# 4970, RRID: AB_2223172 |

| Rabbit CK5 | Cell Signaling | Cat#71536T, RRID: AB_3101753 |

| Rabbit HSP90 | Cell Signaling | Cat# 4877T, RRID: AB_2233307 |

| Goat CD206 | R&D Systems | Cat# AF2535, RRID: AB_2063012 |

| Rabbit CK5 | BioLegend | Cat# 905501, RRID: AB_2565050 |

| Mouse CK8 | Abcam | Cat# ab9023, RRID: AB_306948 |

| Rat Ly6G | Abcam | Cat# ab25377, RRID: AB_470492 |

| Rabbit CD4 | Cell Signaling | Cat# 25229, RRID: AB_2798898 |

| Rat FoxP3 | eBioscience | Cat# 4-4771-80, RRID: AB_529583 |

| Rat Granzyme B | eBioscience | Cat# 50-8898-82, RRID: AB_11219679 |

| Rat LAG3 | Bio X Cell | Cat# BP0174, RRID: AB_10949602 |

| Rat PD-1 | Bio X Cell | Cat# BE0273, RRID: AB_2687796 |

| Bacterial and virus strains | ||

| pCMV5B-Smad4 | Addgene | Cat# 11743 |

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| Protease inhibitor | Roche | Cat# 4693116001 |

| Crystal violet | Sigma | Cat# C0775 |

| Lipofectamine 2000 | Invitrogen | Cat# 11668027 |

| RNAiMAX | Invitrogen | Cat# 13778-150 |

| MRTX1133 | Selleck | Cat# E1051 |

| GSK1120212 | Selleck | Cat# S2673 |

| Verteporfin | Selleck | Cat# S1786 |

| Gemcitabine | LC Laboratories | Cat# G4199 |

| Niclosamide | Selleck | Cat# S3030 |

| Olaparib | Selleck | Cat# S1060 |

| JQ1 | Selleck | Cat# S7110 |

| MK-2206 2HCl | Selleck | Cat# S1078 |

| 7RH | MedChemExpress | Cat# HY-U00444 |

| VS-4718 | Selleck | Cat# S7653 |

| Rapamycin | Selleck | Cat# S1039 |

| RSL3 | MedChemExpress | Cat# HY100218A |

| Erastin | MedChemExpress | Cat# HY15763 |

| Collagenase IV | Gibco | Cat# 17104019 |

| Dispase II | Gibco | Cat# 17105041 |

| Type I collagen solution from rat tail | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# C3867 |

| Critical commercial assays | ||

| Direct-zol RNA Kit | Zymo Research | Cat# 11-331 |

| Reverse Transcription Kit | Applied Biosystems | Cat# 4368814 |

| SYBR Green Master Mix | Applied Biosystems | Cat# 4367659 |

| Cell Counting Kit-8 | Abcam | Cat# ab228554 |

| Chromium Single Cell 3′ Reagent Kits (v2) | 10x Genomics | Cat# PN-120237 |

| ABC-Kit | Vector | Cat# PK-6100 |

| Stable DAB | Invitrogen | Cat# 750118 |

| Alcian blue Stain Kit | Abcam | Cat# 150662 |

| Pierce BCA protein assay kit | Thermo Fisher | Cat# 23208 |

| Picrosirius Red | Abcam | Cat# 150681 |

| TruSeq Stranded mRNA Sample Prep Kit | Illumina | Cat# 20020594 |

| Deposited data | ||

| KPPC and PPSSC cancer cell lines RNA-sequencing | This paper | GEO: GSE268896 |

| KPPC and PPSSC pancreatic tumors Single-cell RNA-sequencing | This paper | GEO: GSE268899 |

| TCGA pancreatic adenocarcinoma cohort survival and gene expression data (GDAC Firehose PAAD) | Broad Institute | http://gdac.broadinstitute.org/runs/stddata__2016_01_28/data/PAAD/20160128/ |

| Experimental models: Cell lines | ||

| Primary mouse KPPC cancer cell line | This paper | N/A |

| Primary mouse PPSSC cancer cell line | This paper | N/A |

| Experimental models: Organisms/strains | ||

| Mouse: LSL-KrasG12D/+;Trp53loxP/+;Pdx1-Cre | Chen et al.32 | N/A |

| Mouse: LSL-KrasG12D/+;Trp5R172H/+;Pdx1-Cre | Chen et al.32 | N/A |

| Mouse: Smad4loxP/loxP | Jackson Laboratory | 017462 |

| Mouse: Tgfbr2loxP/loxP | Jackson Laboratory | 012603 |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| See Table S1 | Sigma | N/A |

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| pCMV5B-Smad4 | Addgene | Cat# 11743 |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| Prism v10.0.0 | GraphPad Software Inc. | http://www.graphpad.com/ |

| cBioportal v2.2.0 | MSK Center for Mol Onc | https://www.cbioportal.org/ |

| Seurat R package (3.5.3) | Satija et al.34 | https://satijalab.org/seurat/ |

| DESeq2 | Anders and Huber35 | https://bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/DESeq2.html |

| STAR aligner | Dobin et al.36 | https://github.com/alexdobin/STAR |

| Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) | Broad Institute | http://software.broadinstitute.org/gsea/index.jsp |

Experimental model and subject details

Mice and housing conditions

The Smad4loxP/loxP (#017462) and Tfgbr2loxP/loxP (#012603) mouse strains were purchased from Jackson Laboratory. Trp53loxP/loxP;Smad4loxP/loxP;Pdx1-Cre (PPSSC) mice were generated from the crossbreeding between Trp53loxP/loxP;Pdx1-Cre and Smad4loxP/loxP. Trp53loxP/loxP;Tfgbr2loxP/loxP;Pdx1-Cre (PPTTC) mice were generated from the crossbreeding between Trp53loxP/loxP;Pdx1-Cre and Tfgbr2loxP/loxP. LSL-KrasG12D;Smad4loxP/loxP;Pdx1-Cre (KSSC) mice were from the crossbreeding between LSL-KrasG12D; Pdx1-Cre and Smad4loxP/loxP. LSL-KrasG12D;Tfgbr2loxP/loxP;Pdx1-Cre (KTTC) mice were from crossbreeding between LSL-KrasG12D; Pdx1-Cre and Tfgbr2loxP/loxP. LSL-KrasG12D;Trp53loxP/loxP;Pdx1-Cre (KPPC) and LSL-KrasG12D;Trp53R172H/+;Pdx1-Cre (KPR172HC) mouse strains were generated following the same design as previously described.32 The experimental mice with desired genotypes were monitored and analyzed with blindness. Both female and male mice were used for experimental mice. All mice were housed under standard housing conditions at MDACC animal facilities. All animal procedures were reviewed and approved by MDACC Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC; protocol number 00002328-RN00).

Cell lines and cell cultures

KPPC and PPSSC cancer cell lines were isolated from KPPC and PPSSC pancreatic tumors. All cells were maintained at 37°C in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2, and regular test of mycoplasma.

Method details

Single-cell RNA-sequencing (scRNA-seq)

KPPC pancreatic tumors were collected from two individual KPPC mice. PPSSC pancreatic tumors were collected from two individual PPSSC mice. All samples were processed and examined following the same protocol as described in our recent studies.31,33,37 Cell suspension obtained from each tumor sample was stained with Live/Dead viability dye eFluor 780 (65-0865-14, eBioscience) and CD45 antibody (157608, BioLegend; anti-mouse CD45.1/CD45.2). Cells were then sorted for live immune cells with Aria II sorter (BD Biosciences) at the North Campus Flow Cytometry and Cellular Imaging Core Facility of MDACC. Then these live immune cells were sent to the Advanced Technology Genomics Core Facility of MDACC. Cells were captured using the 10X Genomics’ Chromium controller and Single Cell 3′ Reagent Kits v3. cDNA was synthesized and amplified to construct Illumina sequencing libraries. The libraries were sequenced by Illumina NovaSeq 6000 system. Seurat version 3.5.3,34 dplyr and cowplot were installed into the R package (version 4.2.2) and used for data analyses. To exclude the cells with poor sequencing quality, a threshold was set as a minimum of 200 and a maximum of 7000 genes per cell. Cells with more than 10% of the mitochondrial genome were excluded. For the cell-cell interaction network analysis, we used the R package CellChat algorithm (version 1.5.0) and the netVisual circle function to visualize circular plot. The signaling role analysis on the aggregated cell-cell communication network was conducted using the netAnalysis_signalingRole_heatmap function in CellChat. The correlation between CD8 and T cell-related genes was analyzed in the T cell population using the corrplot package (version 0.93) with the Pearson method.

Animal studies

C57BL/6J mice (at 2-month age) were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory. KPPC and PPSSC cancer cells (3 × 106 cells in 50 μL PBS) were orthotopically injected into the tail of the pancreas of mice using a 27-gauge Hamilton syringe. After seven days, mice were treated with anti-mouse PD-1 antibody (200 μg/mice) (BE0273-R025mg, Bio X cell) and anti-mouse LAG3 antibody (200 μg/mice) (BP0174-R025mg, Bio X cell), twice weekly for three weeks. The control mice received the Rat IgG2a (200 μg/mice) (clone 2A3, Bio X cell). At four weeks after the orthotopic injection, mice were sacrificed. The pancreatic tumors were dissected, measured, and processed into formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue samples.

Cell culture

Isolation of primary cancer cells from mouse pancreatic tumors was conducted as described in our recent studies.30,32 Briefly, Fresh tumor tissues from KPPC and PPSSC mice were minced with sterilized lancets, and digested with collagenase IV (17104019, Gibco, 4 mg/mL)/dispase II (17105041, Gibco, 4 mg/mL) in DMEM medium at 37°C for 1 h, sequentially filtered by 70 μm and 40 μm cell strainers to generate single cell suspension. The cells were cultured in the DMEM medium containing 20% FBS and 1% penicillin-streptomycin-amphotericin B (PSA) antibiotic mixture.

Histology and immunohistochemistry

Mouse tissues were fixed in 4% formaldehyde, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned at 5 μm thickness. Sections were processed for hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining. Picrosirius red staining for collagen fibers was performed using 0.1% Picrosirius Red (ab150681; Abcam) and counterstained with Weigert’s haematoxylin. Alcian blue staining was performed using the Alcian blue Stain Kit (ab150662, Abcam). Paraffin-embedded sections were processed for immunohistochemical staining as previously described.31 Sections were incubated with primary antibodies: CK19 (ab52625, Abcam, 1:200), Ki67 (ab15580, Abcam, 1:100), Col1 (1310-01, SouthernBiotech, 1:200), αSMA (M0851, DAKO, 1:100), CD4 (ab183685, Abcam, 1; 100), CD8 (85336S, Cell Signaling Technology, 1:100), CD206(AF2535, R&D systems, 1:100), Arginase 1 (ab91279, Abcam, 1:100), CD45 (70257, Cell Signaling Technology, 1:100), p63 (ab124762, Abcam, 1:100), P-ERK (9101S, Cell Signaling Technology, 1:100), CK5 (71536T, Cell Signaling Technology, 1:100), CK8 (MABT329, Sigma, 1:100), Cadherin1 (3195, Cell Signaling Technology, 1; 100), Vimentin (5741, Cell Signaling Technology, 1:100), ZEB1 (NBP1-05987, Novus Biologicals, 1:100) followed by biotinylated secondary antibodies, and streptavidin HRP (Biocare Medical). For all immunolabeling experiments, sections were developed by DAB and counterstained with hematoxylin. Images were taken with a Nikon Eclipse Ci-L Plus microscopy with NIS-Elements 4.5 software. The immunohistochemical staining signaling was quantified by ImageJ. All the procedures for staining, imaging, and quantification were performed blinded to the sample identity and phenotype.

Immunofluorescence

Paraffin-embedded sections were deparaffinized, antigen retrieved and immunostained overnight at 4°C with antibodies for cytokeratin-5 (CK5) (905501, Biolegend, 1:50), cytokeratin-8 (CK8) (ab9023, Abcam, 1:100), LAG3 (ab175841, Abcam, 1:100), Ly6G (ab25377, Abcam, 1:100), CD4 (25229S, Cell Signaling Technology, 1:100), FoxP3 (14-4771-80, eBioscience, 1:100), CD8 (85336S, Cell Signaling Technology, 1:100), and Granzyme B (50-8898-82, eBioscience, 1:200), followed by fluorescent dye-labeled secondary antibodies (Invitrogen) respectively. Slides were then mounted with DAPI-containing Vectashield Mounting Medium (Vector Laboratories). The immunofluorescence was visualized under the Zeiss Axio Observer 7 fluorescence microscope and analyzed with ZEN software (Zeiss).

qRT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted from cells using Direct-Zol RNA MiniPrep Kit (11–331, Zymo Research). For each sample, 2 μg RNA was used for cDNA synthesis with the Reverse Transcription Kit (4368814, ThermoFisher). The cDNA was subjected to the qRT-PCR using PowerUp SYBR Green Master Mix (A25741, Applied Biosystems). The expression levels of indicated genes were normalized to the expression of 18S as the housekeeping gene. The qRT-PCR primers are listed in Table S1.

siRNA interference and plasmid transfection

The KPPC cell lines were transfected with siRNA against Trp63 (SAS_Mm02_00310147 from Sigma). Universal siRNA negative control (SIC002-10NMOL) was purchased from Sigma. For siRNA transfection, 5 × 103 cells were seeded in each well of 96-well tissue culture plates (or 1 × 105 cells seeded in each well of 6-well tissue culture plates) for an additional 1 day prior to siRNA transfection. Then the transfection was performed using Lipofectamine RNAiMAX (13778-150, Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For plasmid transfection, 5 × 104 PPSSC cancer cells were seeded into each well of 12-well tissue culture plate and the transfection of pCMV5B-Smad4 (11743, Addgene) was performed using Lipofectamine 2000 (11668027, Invitrogen). At 72 h after transfection, cells were subjected to cell viability detection, mRNA extraction, and Western blot assays.

Cell proliferation and viability assay

Approximately 5 × 103 cells (calculated using the Countess cell counter, Invitrogen) were seeded into 96-well plates and then treated with indicated conditions for the indicated time. To coat the tissue culture dishes with collagen, 50 μg/mL type I collagen solution (C3867, Sigma) was added into the dishes for 1 h at room temperature, then washed with PBS. Cell viability in each well of 96-well plates was determined using the Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK8; ab228554, Abcam), examined at OD 450 nm on a microplate reader following the manufacturer’s instructions.

Transwell migration assay

The transwell assay was carried out to assess the cell migration of indicated cancer cell lines. Transwell chambers were seeded with 5 × 104 KPPC or PPSSC cancer cells. Then the chambers were kept in 700 μL cell culture medium with 10% FBS. After 16 h, the cells were fixed with 3.7% formaldehyde in PBS for 20 min, followed by staining with 1% crystal violet (C0775-25G, Sigma) in 2% ethanol for another 20 min. After removing the excess dye and the cells on the upper side of the chambers, the migrated cells on the lower side of the chambers were counted and imaged by microscopy. The average cell number of every field represented the number of migrated cells.

Western blot assay

Cells were lysed with RIPA buffer containing the protease inhibitor, and protein concentration was calculated using Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kits (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Isolated protein was solubilized in reducing SDS Laemmli Sample Buffer (Bio-Rad) and denatured at 95°C for 20 min. Samples were then subjected to electrophoresis using Mini-PROTEAN TGX (4–15%) precast polyacrylamide gels (Bio-Rad) and transferred onto polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes using Trans-Blot Turbo Transfer System (Bio-Rad). 5% BSA in TBST buffer was used as the blocking buffer. Following blocking, membranes were incubated 24 h at 4°C in the following primary antibodies: P-ERK (9101S, Cell Signaling Technology, 1:1000), ERK (9102, Cell Signaling Technology, 1:1000), HSP90 (4877T, Cell Signaling Technology, 1:1000), Cleaved Caspase-3 (9664S, Cell Signaling Technology, 1:1000), β-Actin (4970, Cell Signaling Technology, 1:5000), p63 (ab124762, Abcam, 1:500), CK5 (71536T, Cell Signaling Technology, 1:1000), SMAD4 (46535, Cell Signaling Technology, 1:1000). Membranes were incubated with secondary antibodies (Peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit/mouse IgG, Jackson ImmunoResearch) for 1 h at room temperature. Membranes were incubated with chemiluminescence reagents (Chemiluminescent Substrate, 34580, Thermo Scientific) and then developed in the ChemiDoc MP Imaging System according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Total mRNA sequencing (bulk RNA-seq) assay

For RNA-seq, total RNA samples were used to prepare the DNA library and were sequenced on the Illumina Hiseq 2000/2500 platform using the paired-end sequencing method. The raw sequencing data was filtered and aligned to the mouse genome assembly GRCm39 using HISAT2. The Fastq reads were processed by quality control and adaptor trimming, alignment, check strandness and gene count. Different expression gene (DEG) analysis was performed using DESeq2. TPM normalized counts were calculated with the DGEobj.utils package. Functional categorization and pathway reconstitution from the RNA-seq data were conducted using gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) following the guidelines on the GSEA website of Broad Institute (http://www.broadinstitute.org/gsea/index.jsp). The squamous signature gene set was based on a previous study.5

Quantification and statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism software (version 9.0). Quantitative data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Spearman correlation analysis was used to examine the correlation between two factors. For the quantification of staining assays, the staining positive areas in multiple visual fields were quantified by the ImageJ software (v1.53) and averaged to produce an averaged value for each mouse, which was then combined to generate the mean value for all mice in each group. TCGA data were downloaded from the cBioPortal system.38,39 The Z score was calculated using the formula z = (x-μ)/σ, where x is the quantification value for each sample, μ is the population mean for all samples, and σ is the population standard deviation of all samples. For the comparison of two groups, an unpaired t-test was used for comparison of the means. For comparison of more than 2 groups, one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test was used. Kaplan–Meier plots were drawn for survival analysis and Log rank test was used to compare the survival distributions among experimental groups. A p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001, ns: not significant.

Published: September 3, 2024

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xcrm.2024.101711.

Supplemental information

References

- 1.Feig C., Gopinathan A., Neesse A., Chan D.S., Cook N., Tuveson D.A. The pancreas cancer microenvironment. Clin. Cancer Res. 2012;18:4266–4276. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-3114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hezel A.F., Kimmelman A.C., Stanger B.Z., Bardeesy N., Depinho R.A. Genetics and biology of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Genes Dev. 2006;20:1218–1249. doi: 10.1101/gad.1415606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network Integrated Genomic Characterization of Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. Cancer Cell. 2017;32:185–203.e13. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2017.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Waddell N., Pajic M., Patch A.M., Chang D.K., Kassahn K.S., Bailey P., Johns A.L., Miller D., Nones K., Quek K., et al. Whole genomes redefine the mutational landscape of pancreatic cancer. Nature. 2015;518:495–501. doi: 10.1038/nature14169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bailey P., Chang D.K., Nones K., Johns A.L., Patch A.M., Gingras M.C., Miller D.K., Christ A.N., Bruxner T.J.C., Quinn M.C., et al. Genomic analyses identify molecular subtypes of pancreatic cancer. Nature. 2016;531:47–52. doi: 10.1038/nature16965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kamisawa T., Wood L.D., Itoi T., Takaori K. Pancreatic cancer. Lancet. 2016;388:73–85. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00141-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Singhi A.D., George B., Greenbowe J.R., Chung J., Suh J., Maitra A., Klempner S.J., Hendifar A., Milind J.M., Golan T., et al. Real-Time Targeted Genome Profile Analysis of Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinomas Identifies Genetic Alterations That Might Be Targeted With Existing Drugs or Used as Biomarkers. Gastroenterology. 2019;156:2242–2253.e4. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.02.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Singh H., Keller R.B., Kapner K.S., Dilly J., Raghavan S., Yuan C., Cohen E.F., Tolstorukov M., Andrews E., Brais L.K., et al. Oncogenic Drivers and Therapeutic Vulnerabilities in KRAS Wild-Type Pancreatic Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2023;29:4627–4643. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-22-3930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heining C., Horak P., Uhrig S., Codo P.L., Klink B., Hutter B., Fröhlich M., Bonekamp D., Richter D., Steiger K., et al. NRG1 Fusions in KRAS Wild-Type Pancreatic Cancer. Cancer Discov. 2018;8:1087–1095. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-18-0036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Luchini C., Paolino G., Mattiolo P., Piredda M.L., Cavaliere A., Gaule M., Melisi D., Salvia R., Malleo G., Shin J.I., et al. KRAS wild-type pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: molecular pathology and therapeutic opportunities. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2020;39:227. doi: 10.1186/s13046-020-01732-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Philip P.A., Azar I., Xiu J., Hall M.J., Hendifar A.E., Lou E., Hwang J.J., Gong J., Feldman R., Ellis M., et al. Molecular Characterization of KRAS Wild-type Tumors in Patients with Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2022;28:2704–2714. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-21-3581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fang Y., Su Z., Xie J., Xue R., Ma Q., Li Y., Zhao Y., Song Z., Lu X., Li H., et al. Genomic signatures of pancreatic adenosquamous carcinoma (PASC) J. Pathol. 2017;243:155–159. doi: 10.1002/path.4943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hingorani S.R., Wang L., Multani A.S., Combs C., Deramaudt T.B., Hruban R.H., Rustgi A.K., Chang S., Tuveson D.A. Trp53R172H and KrasG12D cooperate to promote chromosomal instability and widely metastatic pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma in mice. Cancer Cell. 2005;7:469–483. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ying H., Kimmelman A.C., Lyssiotis C.A., Hua S., Chu G.C., Fletcher-Sananikone E., Locasale J.W., Son J., Zhang H., Coloff J.L., et al. Oncogenic Kras maintains pancreatic tumors through regulation of anabolic glucose metabolism. Cell. 2012;149:656–670. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.01.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Collins M.A., Bednar F., Zhang Y., Brisset J.C., Galbán S., Galbán C.J., Rakshit S., Flannagan K.S., Adsay N.V., Pasca di Magliano M. Oncogenic Kras is required for both the initiation and maintenance of pancreatic cancer in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 2012;122:639–653. doi: 10.1172/JCI59227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Somerville T.D., Biffi G., Daßler-Plenker J., Hur S.K., He X.Y., Vance K.E., Miyabayashi K., Xu Y., Maia-Silva D., Klingbeil O., et al. Squamous trans-differentiation of pancreatic cancer cells promotes stromal inflammation. Elife. 2020;9:e53381. doi: 10.7554/eLife.53381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mills A.A., Zheng B., Wang X.J., Vogel H., Roop D.R., Bradley A. p63 is a p53 homologue required for limb and epidermal morphogenesis. Nature. 1999;398:708–713. doi: 10.1038/19531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Soares E., Zhou H. Master regulatory role of p63 in epidermal development and disease. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2018;75:1179–1190. doi: 10.1007/s00018-017-2701-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Somerville T.D.D., Xu Y., Miyabayashi K., Tiriac H., Cleary C.R., Maia-Silva D., Milazzo J.P., Tuveson D.A., Vakoc C.R. TP63-Mediated Enhancer Reprogramming Drives the Squamous Subtype of Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. Cell Rep. 2018;25:1741–1755.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.10.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nguyen B.C., Lefort K., Mandinova A., Antonini D., Devgan V., Della Gatta G., Koster M.I., Zhang Z., Wang J., Tommasi di Vignano A., et al. Cross-regulation between Notch and p63 in keratinocyte commitment to differentiation. Genes Dev. 2006;20:1028–1042. doi: 10.1101/gad.1406006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sakamoto K., Fujii T., Kawachi H., Miki Y., Omura K., Morita K.i., Kayamori K., Katsube K.i., Yamaguchi A. Reduction of NOTCH1 expression pertains to maturation abnormalities of keratinocytes in squamous neoplasms. Lab. Invest. 2012;92:688–702. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2012.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Borrelli S., Testoni B., Callari M., Alotto D., Castagnoli C., Romano R.A., Sinha S., Viganò A.M., Mantovani R. Reciprocal regulation of p63 by C/EBP delta in human keratinocytes. BMC Mol. Biol. 2007;8:85. doi: 10.1186/1471-2199-8-85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Collisson E.A., Sadanandam A., Olson P., Gibb W.J., Truitt M., Gu S., Cooc J., Weinkle J., Kim G.E., Jakkula L., et al. Subtypes of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma and their differing responses to therapy. Nat. Med. 2011;17:500–503. doi: 10.1038/nm.2344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moffitt R.A., Marayati R., Flate E.L., Volmar K.E., Loeza S.G.H., Hoadley K.A., Rashid N.U., Williams L.A., Eaton S.C., Chung A.H., et al. Virtual microdissection identifies distinct tumor- and stroma-specific subtypes of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Nat. Genet. 2015;47:1168–1178. doi: 10.1038/ng.3398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hayashi A., Fan J., Chen R., Ho Y.J., Makohon-Moore A.P., Lecomte N., Zhong Y., Hong J., Huang J., Sakamoto H., et al. A unifying paradigm for transcriptional heterogeneity and squamous features in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Nat. Cancer. 2020;1:59–74. doi: 10.1038/s43018-019-0010-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang X., Allen S., Blake J.F., Bowcut V., Briere D.M., Calinisan A., Dahlke J.R., Fell J.B., Fischer J.P., Gunn R.J., et al. Identification of MRTX1133, a Noncovalent, Potent, and Selective KRAS(G12D) Inhibitor. J. Med. Chem. 2022;65:3123–3133. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.1c01688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kemp S.B., Cheng N., Markosyan N., Sor R., Kim I.K., Hallin J., Shoush J., Quinones L., Brown N.V., Bassett J.B., et al. Efficacy of a Small-Molecule Inhibitor of KrasG12D in Immunocompetent Models of Pancreatic Cancer. Cancer Discov. 2023;13:298–311. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-22-1066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mahadevan K.K., McAndrews K.M., LeBleu V.S., Yang S., Lyu H., Li B., Sockwell A.M., Kirtley M.L., Morse S.J., Moreno Diaz B.A., et al. KRAS(G12D) inhibition reprograms the microenvironment of early and advanced pancreatic cancer to promote FAS-mediated killing by CD8(+) T cells. Cancer Cell. 2023;41:1606–1620.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2023.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jin S., Guerrero-Juarez C.F., Zhang L., Chang I., Ramos R., Kuan C.H., Myung P., Plikus M.V., Nie Q. Inference and analysis of cell-cell communication using CellChat. Nat. Commun. 2021;12:1088. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-21246-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen Y., LeBleu V.S., Carstens J.L., Sugimoto H., Zheng X., Malasi S., Saur D., Kalluri R. Dual reporter genetic mouse models of pancreatic cancer identify an epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition-independent metastasis program. EMBO Mol. Med. 2018;10:e9085. doi: 10.15252/emmm.201809085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen Y., Kim J., Yang S., Wang H., Wu C.J., Sugimoto H., LeBleu V.S., Kalluri R. Type I collagen deletion in alphaSMA(+) myofibroblasts augments immune suppression and accelerates progression of pancreatic cancer. Cancer Cell. 2021;39:548–565.e546. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2021.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen Y., Yang S., Tavormina J., Tampe D., Zeisberg M., Wang H., Mahadevan K.K., Wu C.J., Sugimoto H., Chang C.C., et al. Oncogenic collagen I homotrimers from cancer cells bind to alpha3beta1 integrin and impact tumor microbiome and immunity to promote pancreatic cancer. Cancer Cell. 2022;40:818–834.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2022.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McAndrews K.M., Chen Y., Darpolor J.K., Zheng X., Yang S., Carstens J.L., Li B., Wang H., Miyake T., Correa de Sampaio P., et al. Identification of Functional Heterogeneity of Carcinoma-Associated Fibroblasts with Distinct IL6-Mediated Therapy Resistance in Pancreatic Cancer. Cancer Discov. 2022;12:1580–1597. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-20-1484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Satija R., Farrell J.A., Gennert D., Schier A.F., Regev A. Spatial reconstruction of single-cell gene expression data. Nat. Biotechnol. 2015;33:495–502. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Anders S., Huber W. Differential expression and analysis for sequence count data. Genome Biol. 2010;11:R106. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-10-r106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dobin A., Davis C.A., Schlesinger F., Drenkow J., Zaleski C., Jha S., Batut P., Chaisson M., Gingeras T.R. STAR: ulterfast univeral RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics. 2013;29:15–21. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yang D., Sun X., Moniruzzaman R., Wang H., Citu C., Zhao Z., Wistuba I.I., Wang H., Maitra A., Chen Y. Genetic Deletion of Galectin-3 Inhibits Pancreatic Cancer Progression and Enhances the Efficacy of Immunotherapy. Gastroenterology. 2024;167:298–314. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2024.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cerami E., Gao J., Dogrusoz U., Gross B.E., Sumer S.O., Aksoy B.A., Jacobsen A., Byrne C.J., Heuer M.L., Larsson E., et al. The cBio cancer genomics portal: an open platform for exploring multidimensional cancer genomics data. Cancer Discov. 2012;2:401–404. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gao J., Aksoy B.A., Dogrusoz U., Dresdner G., Gross B., Sumer S.O., Sun Y., Jacobsen A., Sinha R., Larsson E., et al. Integrative analysis of complex cancer genomics and clinical profiles using the cBioPortal. Sci. Signal. 2013;6:pl1. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2004088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Bulk RNA-seq and single-cell RNA-seq data were deposited in GEO and publicly available as of the date of publication. The accession numbers are: GSE268896 and GSE268899. This paper does not generate any original codes. Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this work paper is available from the lead contact upon request.