Abstract

Purpose of Review

COVID -19 associated olfactory dysfunction is widespread, yet effective treatment strategies remain unclear. This article aims to provide a comprehensive systematic review of therapeutic approaches and offers evidence-based recommendations for their clinical application.

Recent Findings

A living Cochrane review, with rigorous inclusion criteria, has so far included 2 studies with a low certainty of evidence.

Summary

In this systematic review we list clinical data of 36 randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and non-randomised studies published between Jan 1, 2020 and Nov 19, 2023 regarding treatment options for COVID-19 associated olfactory dysfunction. Nine treatment groups were analysed, including olfactory training, local and systemic corticosteroids, platelet-rich plasma (PRP), calcium chelators, vitamin supplements including palmitoylethanolamide with luteolin, insulin, gabapentin and cerebrolysin. Primary objective was the effect of the studied treatments on the delta olfactory function score (OFS) for objective/psychophysical testing. Treatments such as PRP and calcium chelators demonstrated significant improvements on OFS, whereas olfactory training and corticosteroids did not show notable efficacy for COVID-19 associated olfactory dysfunction.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s11882-024-01182-6.

Keywords: COVID-19, Olfactory dysfunction, Treatment

Introduction

Olfactory dysfunction (OD) is a common clinical symptom of COVID-19 with a prevalence of up to 77% [1–3]. The clinical course is usually short, but varies significantly. A meta-analysis from 2023 showed a prevalence of 31% at 6 months [4]. Despite the significant proportion of patients having persistent OD, there is still no clear recommendation on the most appropriate treatment for COVID-19 associated OD [5]. A living Cochrane review, with rigorous inclusion criteria (only RCTs), has so far included 2 studies with a low certainty of evidence. The studies evaluated systemic corticosteroids plus intranasal corticosteroid/mucolytic/decongestant and PEA-LUT with very limited evidence and no meaningful conclusions could be drawn [6]. Olfactory training (OT) is widely suggested as a first-line treatment for post-infectious olfactory dysfunction, including COVID-19-associated OD [7].

A recent meta-analysis by Delgado-Lima showed a statistically significant positive impact of olfactory training on the enhancement of all domains of olfactory function [8]. However, the precise mechanism by which olfactory training restores or improves olfactory function remains elusive. Furthermore, there is still discussion about the true efficacy of olfactory training, with some studies showing no additional benefit [9]. A systematic review of Pekala suggests that OT may represent a promising intervention for OD due to multiple etiologies, but several limitations of the included studies prevented them from making generalized recommendations [10]. Studies assessing the efficacy of olfactory training are often heterogeneous, lacking standardization in protocols. There are variations in the duration, frequency, and types of odors used in training, and many studies do not include a control group. These factors make it challenging to compare results across different studies.

Experimental data suggest that olfactory training may improve olfactory function, although the degree of improvement can vary. Current evidence indicates that olfactory training alone might have modest effects, but it remains a valuable part of a comprehensive approach to treating olfactory dysfunction [11, 12].

Opinions on the use of intranasal or oral corticosteroids, however, are controversial and should be considered on an individual basis [13–15]. And so far, there is no consensus about the use of other treatment options such as alpha-lipoic acid, vitamin A or omega-3 supplements, platelet-rich plasma or calcium chelators [5].

Long lasting OD can result in depression and cognitive impairment and has a significant negative impact on a person’s quality of life (QoL) [16, 17]. To adequately counsel and guide patients, a systematic review of the current evidence regarding treatment options in COVID-19 associated OD is essential. In this systematic review, our focus is to summarise all current clinical data on pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatments for COVID-19 associated OD.

Methods

Search Strategy and Selection Criteria

A systematic review was conducted, in accordance with the PRIMS guidelines, to explore treatment strategies for COVID-19 associated OD. In collaboration with biomedical reference librarians of the KU Leuven Libraries, we defined a search strategy based on a predefined population, intervention, comparator, outcome (PICO) model. The population of interest included patients with COVID-19 associated OD, experiencing OD for at least one month to account for the high rate of spontaneous recovery within the first month. The intervention included any therapeutic options for OD, with comparisons against placebo/sham procedures, alternative treatments or no treatment at all. The primary outcome measure was the change in olfactory function score (ΔOFS), subjectively and/or objectively (panel) after the treatment/intervention or placebo/sham/no treatment. Next, we formulated a search strategy based on relevant keywords (Supp. 1), searching through 7 databases (PubMed, Embase, Web of Science Core Collection, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), ClinicalTrials.gov, ICTRP and Europe PMC). Relevant reviews were filtered and scanned for additional references. Manuscripts in English, Dutch, Spanish and German from Jan 1, 2020 on were eligible for inclusion. The study protocol was published in the Prospero database (ID CRD42022300627). After publication of the protocol, we searched the databases on Nov 19, 2023. All manuscripts were exported to a reference manager, EndNote, and duplicates were removed. Manuscripts were then exported to Rayyan and two reviewers (SB and MM) screened titles and abstracts for eligibility. Conflicts were resolved by consensus. Next, full texts were assessed by two reviewers (SB and MM) according to the inclusion criteria. An electronic data collection form (Microsoft Excel) was filled in for all studies. Two reviewers (SB and MM) assessed risk of bias using the “Risk of Bias 2 (RoB2) tool” for randomised trials and the “Risk of Bias in Non-randomised Studies – of Interventions (ROBINS-I) tool” for non-randomised trials. Manuscripts were then sorted by intervention, study design and outcome parameters.

Outcome

Primary objective was the effect of the studied treatments on the recovery rate, OFS of COVID-19 associated OD and serious adverse events (Prospero database ID CRD42022300627). Only a few articles reported on the recovery rate, therefore, we focused on the OFS. ΔOFS was defined as the delta (Δ) of the pre- and posttreatment score of objective/psychophysical testing.

The most common objective function tests were TDI, UPSIT, BSIT and CCRC. The TDI (Threshold, Discrimination, and Identification) test evaluates olfactory function through three components: threshold (detecting the minimum concentration of an odour), discrimination (distinguishing between different odours), and identification (recognizing specific odours). Each component is scored from 0 to 16, resulting in a combined maximum score of 48 [18]. The UPSIT (University of Pennsylvania Smell Identification Test) is a standardized smell identification test consisting of 40 odorants embedded in a scratch-and-sniff booklet. Subjects scratch each odorant and select the correct identification from four multiple-choice options [19]. The BSIT (Brief Smell Identification Test) is a shorter version of the UPSIT, typically consisting of 12 odorants [20]. It follows the same scratch-and-sniff format and multiple-choice identification method. The CCCRC (Connecticut Chemosensory Clinical Research Center) assesses olfactory function through two components: threshold and identification from a list of options [21]. Secondary objective was the effect of the studied treatments on parosmia and the duration of COVID-19 associated OD. We also assessed serious adverse effects.

Data synthesis

A descriptive synthesis of the intervention effects of the selected studies was done. Study characteristics were summarised in a descriptive table and full text according to treatment modalities. Quantitative analysis was performed with RevMan if sufficient studies with consistency in reporting on OD were available and statistical heterogeneity was limited (I2 < 50%). Continuous data were collected by mean difference (MD) with either 95% CIs or SDs. Taking different measurement tools for OD into account, the standardised MD (SMD) for the quantitative analysis was calculated. For studies that reported baseline and post-treatment OFS with standard deviations but did not specify the ΔOFS, we calculated the ΔOFS and its corresponding standard deviation. The study from D’Ascanio et al. and from Abu Shaby et al. did not provide a standard deviation for the OFS, so no proper analysis could be done with RevMan (Review Manager).

Results

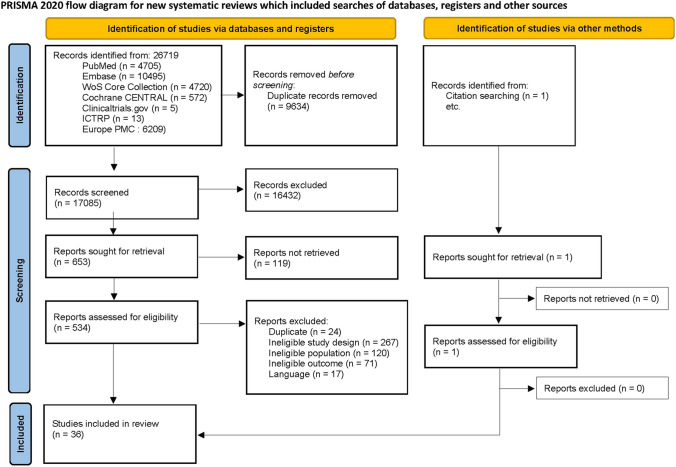

Our database search resulted in a total of 26,719 studies (Fig. 1). After removing duplicates, 17085 articles were retained. Titles and abstracts were screened, resulting in 653 articles that were eligible for further screening. After full text screening, 35 articles were eligible for inclusion based on the predefined selection criteria. In addition, one article about COVID-19 associated OD was included from citation searching, resulting in 36 studies included for qualitative synthesis. The main reasons for exclusion were ineligible study designs, not meeting the inclusion criteria for the population or outcome (i.e. focus not on olfactory dysfunction but on other COVID-19 symptoms). In the following sections we provide a detailed overview of the current evidence regarding therapies for COVID-19 associated OD.

Fig. 1.

Prisma flow-chart (From: Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2020;372:n71. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71)

Olfactory Training

Seven studies, five RCTs, and two non-randomised studies, have been published regarding OT for COVID-19 associated olfactory dysfunction (Table 1) [22–28]. Patients received OT with either the classical four scents or a modified training with eight scents. The duration of the therapy was 1.5 to 3 months, and the follow-up was 1–12 months. For the quantitative analysis, regarding the ΔOFS, we included 4 studies [24, 27–29]. Overall, the total effect across all studies indicates a standardized mean difference (SMD) of 0.05 (95% CI: -0.25 to 0.36), suggesting no significant overall impact of OT compared to control (p = 0.73) (Fig. 2). The analysis found no heterogeneity among the studies (I2 = 0%).

Table 1.

Included studies olfactory training

| Therapy | Reference | Study design |

Samplesize | Intervention | Comparison | Outcomes | Parosmia assessment | Measurement tool/time |

Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Olfactory Training | |||||||||

| [26] | RCT | 56 |

Oral Vitamin A (25,000 IU daily for 14 days) + Olfactory training (sniffing four odour each 20 s thrice daily for 4 weeks) |

Olfactory training (sniffing four odour each 20 s thrice daily for 4 weeks) No treatment |

Change in OFS, Change in OD classification |

No |

BTT, SIT, MRI, rs-fMRI at 0, 2, 4 weeks |

Significant improvement in intervention group (BTT, SIT) No significant improvement in both control groups |

|

| [24] | RCT | 63 |

Olfactory training (sniffing four scents for 15 s each twice daily for 12 weeks) |

No treatment | Change in OFS | No |

BSIT, QoL at 0, 12 weeks, 1 year |

No significant improvement | |

| [29] | RCT | 50 |

Olfactory training (sniffing four scents for 10 s each twice daily for 12 weeks) |

Placebo (sniffing odorless propylene glycol) |

Final OFS | Yes |

UPSIT, VAS-score, Parosmia assessment, QoL at 0, 12 weeks |

No improvement of UPSIT Significant improvement of VAS, Parosmia and QoL |

|

| [23] | RCT | 80 |

Modified Olfactory training (sniffing eight scents for 15 s each twice daily for 12 weeks) |

Olfactory training (sniffing four scents for 15 s each twice daily for 12 weeks) |

Final OFS Change in OFS |

No |

UPSIT, VAS-score at 0, 4 weeks |

No improvement between groups Significant improvement pre-, posttreatment both together |

|

| [28] | NRS | 67 |

Oral corticosteroids (Prednisolone 40 mg/daily for 5 days, then tapered down over 9 days) + Corticosteroid nasal spray (Betamethasone 0.1%, 2 drops/nostril twice daily for 2 weeks) + Olfactory training (idem as comparison group) |

Olfactory training (sniffing four scents twice daily for 12 week) No treatment |

Change in OFS | Yes |

TDI, VAS-score at 0, 6 months |

Significant improvement in intervention group and OT (TDI) Significant improvement in intervention group (VAS) No significant improvement between intervention group and OT |

|

| [25] | NRS | 75 |

Modified olfactory training (3 × sniffing 4 scents 10 s each for 5 min, twice a day for 12 weeks) |

No Treatment | Final OFS | Yes |

TDI, Parosmia assessment at 0, 3, 6, 9 months |

Significant improvement of Parosmia and TDI | |

| [27] | NRS | 69 |

PEA/Luteolin supplement (PEA 700 mg and Luteolin 70 mg once daily for 90 days) + Olfactory training (prior) (sniffing four scents 6 s each, three times daily for 6 min each session) |

PEA/Luteolin supplement (PEA 700 mg and Luteolin 70 mg twice daily for 90 days) + Olfactory training (naive) (same as intervention group) PEA/Luteolin supplement (PEA 700 mg and Luteolin 70 mg once daily for 90 days) |

Final OFS, Change in OFS |

Yes |

Sniffin’ Sticks Score Identification, Parosmia VAS at 0, 30, 60, 90 days |

Most significant improvement in PEA/Leotlin and OT group (prior) for Identification, Significant improvement of Parosmia in all groups at 90 days, between groups no difference |

RCT randomised clincial trial, NRS non-randomised studies, OFS olfactory function sceore

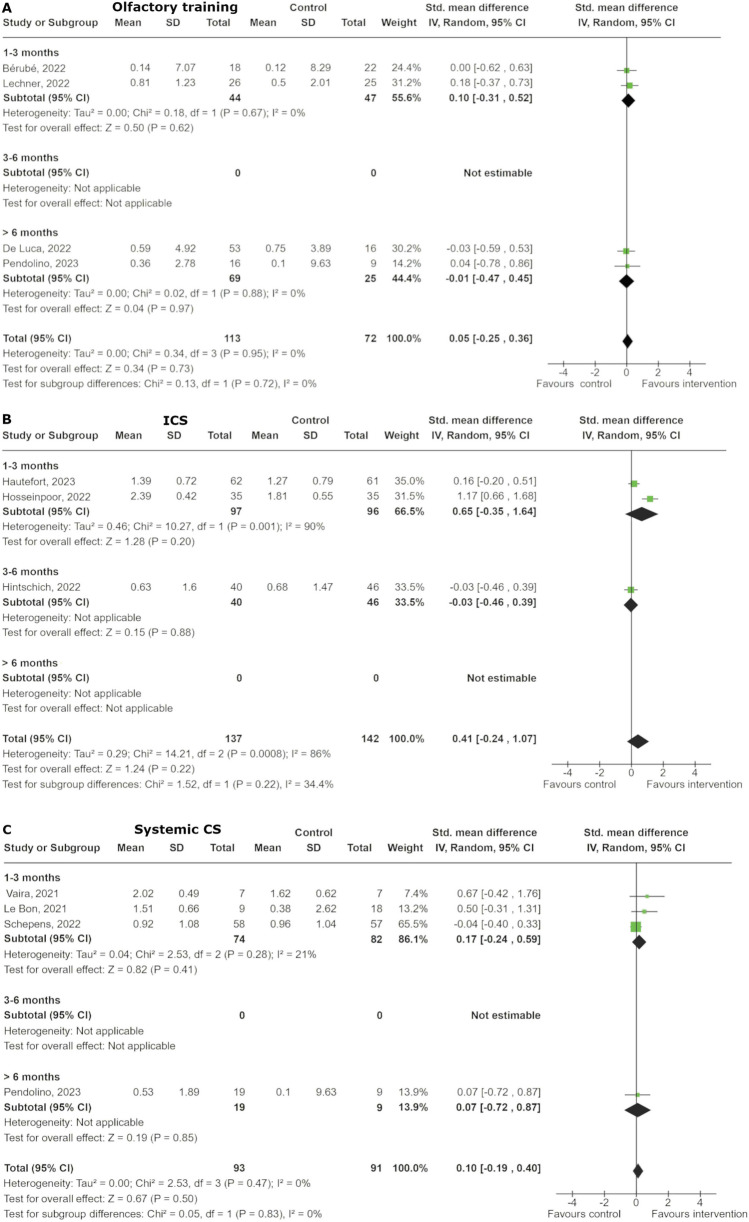

Fig. 2.

Forest plot of the effect of (A) olfactory training, (B) intranasal corticosteroids (ICS) and (C) systemic corticosteroids (CS). The studies are categorized based on the duration of smell loss before the treatment, split into 3 subgroups: less than 3 months, between 3 to 6 months, and more than 6 months

In the subgroup analysis for OD duration of one to three months, the SMD was 0.10 (95% CI: -0.31 to 0.52) and for OD duration greater than six months, the SMD was 0.01 (95% CI: -0.47 to 0.45). Both analyses showed no significant differences (p = 0.62 and p = 0.97, respectively).

Intranasal Corticosteroids

We found six studies, five RCTs and one non-randomised study, involving the use of topical corticosteroids (Table 2) [30–35]. In most studies the patients received nasal corticosteroid sprays with a duration from two weeks to three months. Concomitant OT, in intervention and control group, was performed in four of the six studies.

Table 2.

Included studies corticosteroids

| Therapy | Reference | Study design |

Sample size |

Intervention | Comparison | Outcomes | Parosmia assessment | Measurement tool/time |

Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intranasal Coricosteroids | |||||||||

| [32] | RCT | 123 |

Corticosteroid nasal irrigation (with budesonide (1 mg/2 ml) and 250 ml saline solution in a 20 ml syringe twice daily for 30 days) + Olfactory training (idem as in comparison group) |

Nasal saline irrigation (saline solution in a 20 ml syringe twice daily for 30 days) + Olfactory training (idem as in intervention group) |

Change in OFS Recovery rate |

No |

ODORATEST at 0, 30, 60 days and 8 months |

No improvement compared to other group | |

| [34] | RCT | 40 |

Corticosteroid injection (8 × Dexamethasone injection (8 mg) near the olfactory cleft over 2 months) |

Saline injection (application idem as in intervention group) |

Final OFS | No |

QOD-NS at 0, 4 weeks |

Significant improvement in both groups No significant improvement between groups |

|

| [33] | RCT | 20 |

Corticosteroid nasal spray (Mometasone furoate spray 2 puffs/nostril with 50 µg once daily for 3 weeks) + Olfactory training (idem as in comparison group) |

Olfactory training (sniffing four scents for 10 s each twice daily for 3 weeks) |

Final OFS | No |

TDI, 20-item taste powder test at 0, 2, 3 months |

Significant improvement in both groups No significant improvement between groups |

|

| [30] | RCT | 80 |

Corticosteroid nasal spray (Mometasone Furoate 0.05% 1 puff/nostril twice daily for 4 weeks) |

Nasal saline irrigation (saline solution 1 puff/nostril twice daily for 4 weeks) |

Final OFS Change in OFS, Change in OD classification |

No |

Iran-SIT, VAS-score at 0, 2, 4 weeks |

Significant improvement in Final and Change in OFS No significant improvement in change in OD classification |

|

| [31] | RCT | 112 |

Corticosteroid nasal spray (Mometasone Furoate of 100 µg 2 puffs/nostril twice daily for 3 months) + Olfactory training (idem as in comparison group) |

Olfactory training (sniffing three scents for 30 s each twice daily for 3 weeks) |

Final OFS Change in OFS |

No |

TDI at 0, 3 months |

Significant improvement in both groups (Final OFS), No significant improvement in Change in OFS No significant improvement between groups |

|

|

Intranasal Vitamin A&E + Olfactory training (idem as in comparison group) |

Olfactory training (a sniffing session of 10 min twice daily for 30 days) |

Sniffin’ Sticks Threshold, VAS-score at 0, 3 months |

All significant improvement, with adjuvant therapy more No significant difference between the groups |

||||||

| [35] | NRS | 47 |

Corticosteroid nasal spray (Mometasone Furoate of 100 µg 2 puffs/nostril twice daily for 3 months) + Olfactory training (idem as in comparison group) |

Change in OFS | No | ||||

|

Corticosteroid nasal spray + Multivitamin supplement + Olfactory training (idem as in comparison group) |

|||||||||

| Oral Coricosteroid | |||||||||

| [37] | RCT | 115 |

Oral corticosteroids (Prednisolone 40 mg once daily for 10 days) + Olfactory training (for 12 weeks) |

Placebo (Matching Placobo pills for 10 days) + Olfactory training (idem) |

Change in OFS Final OFS |

No |

TDI, VAS-score, ODQ at 0, 12 weeks |

No improvement | |

| [36] | RCT | 18 |

Oral corticosteroids (Prednisolone starting at a concentration of 1 mg/kg once daily with tapering for 15 days) + Nasal irrigation corticosteroid spray (Bethamethasone, Ambroxol and Rinazine for 15 days) |

No treatment |

Recovery rate, Change in OFS, Change in OD classification |

No |

CCCRC at 0, 20 and 40 days |

Significant improvement at day 20 in intervention group, at day 40 in both groups | |

| [28] | NRS | 67 |

Oral corticosteroids (Prednisolone 40 mg/daily for 5 days, then tapered down over 9 days) + Corticosteroid nasal spray (Betamethasone 0.1%, 2 drops/nostril twice daily for 2 weeks) + Olfactory training (idem as comparison group) |

Olfactory training (sniffing four scents twice daily for 12 week) No treatment |

Change in OFS | Yes |

TDI, VAS-score at 0, 6 months |

Significant improvement in intervention group and OT (TDI) Significant improvement in intervention group (VAS) No significant improvement between intervention group and OT |

|

| [38] | NRS | 72 |

Oral corticosteroids (Methylprednisolone 32 mg once daily for 10 days) + Olfactory training (idem as in comparison group) |

Olfactory training (sniffing four scents for 10 s each twice daily for ten weeks) |

Change in OFS | No |

Sniffin’ Sticks battery test at 0 and 10 weeks |

Significant improvement in intervention group No significant improvemnt in control group |

RCT randomised clincial trial, NRS non-randomised studies, OFS olfactory function sceore

For the quantitative analysis we considered 3 studies, which evaluated the ΔOFS [30–32]. The overall pooled SMD across all subgroups is 0.41 [95% CI: -0.24, 1.07], indicating a non-significant trend, favouring the intervention group (Fig. 2). However, there is substantial heterogeneity (I2 = 86%). While there might be a trend towards a benefit with intranasal corticosteroids, the effect is inconsistent and not statistically significant.

Oral Corticosteroids

Four studies, two RCTs and two non-randomised trials, described the effect of oral CS on olfactory function (Table 2) [28, 36–38]. Patients received either 32 mg, 40 mg or 1 mg/kg once daily for 10–15 days. Concomitant OT was performed in two studies, and concomitant corticosteroid nasal spray in one study. Follow-up was conducted from 10 weeks to 6 months.

All studies reported on the ΔOFS with a pooled SMD of 0.10 [95% CI: -0.19, 0.40], indicating no significant difference between the systemic CS and control groups. Subgroup analysis regarding OD duration also showed no significant difference (Fig. 2).

Platelet-Rich Plasma (PRP)

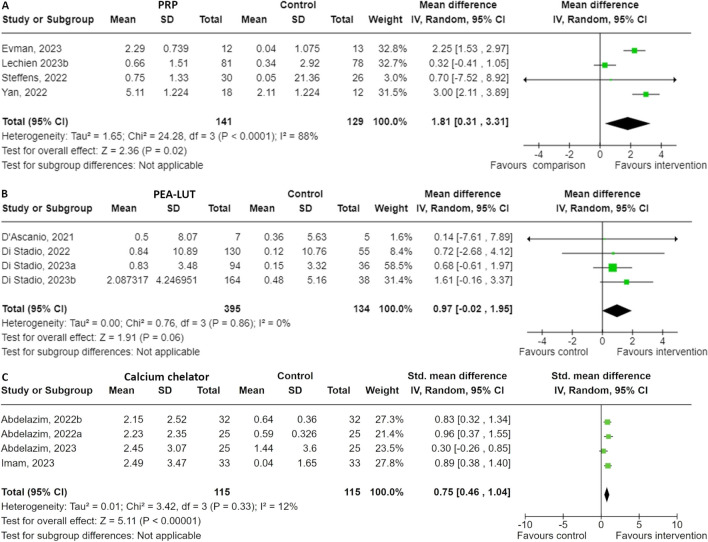

We found 5 studies, 3 RCTs and 2 non-randomised trials, examining the effect of platelet-rich plasma on olfactory dysfunction (Table 3) [39–43]. All 5 studies administered PRP injections into the olfactory cleft mucosa, ranging from one to three times. Control groups either received OT, placebo injection or no treatment at all. Four studies reported about the ΔOFS and were included in the quantitative analysis. The overall SMD favours PRP, with a pooled mean SMD of 1.81 [95% CI: 0.31, 3.31], indicating a statistically significant improvement for PRP treatment (p = 0.02) (Fig. 3. The heterogeneity is high (I2 = 88%), suggesting substantial variability among the study results, therefore, the results should be interpreted with caution. Three studies reported about the outcome of parosmia [40, 42, 43]. These studies compared PRP injection to either a control group with pre-existing treatments for OD, including OT, intranasal corticosteroids, omega-3, vitamin B12, and zinc supplementation for 6 weeks, to a placebo group with saline injection into the olfactory cleft. Due to substantial differences in measured outcomes, no quantitative analysis was conducted. The study of El Naga and the study of Lechien reported a significant improvement, while the study of Yan showed no improvement at all [40, 42, 43]. PRP injection was generally well tolerated.

Table 3.

Included studies of other treatments

| Therapy | Reference | Study design |

Sample size |

Intervention | Comparison | Outcomes | Parosmia assessment | Measurement tool/time |

Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Platelet-Rich Plasma | |||||||||

| [39] | RCT | 32 |

PRP Injection (1 ml PRP into olfactory cleft once) |

No treatment | Change in OFS | No |

CCCRC at 0, 4 weeks |

Significant improvement in intervention group | |

| [40] | RCT | 35 |

PRP Injection (2 × 1 ml PRP into olfactory cleft submucosally at 2 sites three times) |

Placebo (1 ml Saline injection into the olfactory cleft) |

Change in OFS, Duration of OD |

Yes |

UPSIT, VAS-score at 0, 4 and 12 weeks |

Significant improvement in both groups (VAS) Significant improvement in intervention group (TDI) No improvement of Parosmia |

|

| [43] | RCT | 60 |

PRP Injection (1 ml PRP into into the olfactory region approximately every 1 cm2 three times at three weeks intervals) |

Pre-study treatment (olfactory training, topical corticosteroids, omega-three, vitamin B12, and zinc supplementation for 6 weeks) |

Final OFS | Yes |

Parosmia VAS at 0, 4 weeks after 3. Injection |

More significant improvement in intervention group | |

| [42] | NRS | 159 |

PRP Injection (bilateral 4 to 6 injections of 0.2 mL in the nasal septum of the olfactory cleft and medial part of the middle turbinate three times) + Olfactory training (sniffing four scents for 12 weeks) |

Olfactory training (sniffing four scents for 12 weeks) |

Final OFS | Yes |

TDI, Olfactory Disorder Questionnaire (ODQ) at 0, 10 weeks |

Significant improvement of TDI in both groups Significant improvement of Parosmia and ODQ in intervention group |

|

| [41] | NRS | 56 |

PRP Injection (1 ml PRP into each olfactory cleft submucosally) |

Olfactory training (a sniffing session of 10 min twice daily for 30 days) |

Change in OFS Final OFS |

No |

TDI, Likert-scale at 0, 4 weeks |

Significant improvement of TDI and Likert-scale in intervention group | |

| Vitamin supplement | |||||||||

| [48] | RCT | 139 |

Oral Omega-3 Fish Oil (2,000 mg daily of O3FA supplementation twice daily for 6 weeks) |

Placebo (placebo pill of identical size and shape twice daily for 6 weeks) |

Final OFS, Change in OFS |

No |

BSIT, mQOD-NS at 0, 6 weeks, long-term |

No significant improvement of BSIT in both groups Significant improvement of mQOD-NS in both groups |

|

| [26] | RCT | 56 |

Oral Vitamin A (25,000 IU daily for 14 days) + Olfactory training (sniffing four odour each 20 s thrice daily for 4 weeks) |

Olfactory training (sniffing four odour each 20 s thrice daily for 4 weeks) No treatment |

Change in OFS, Change in OD classification |

No |

BTT, SIT, MRI, rs-fMRI at 0, 2, 4 weeks |

Significant improvement in intervention group (BTT, SIT) No significant improvement in both control groups |

|

| [49] | RCT | 128 |

Alpha-lipoic acid (600 mg/day for 12 weeks) + Olfactory training (sniffing four scents for 10 s each twice daily for 12 weeks) |

Placebo (pills 600 mg/day for 12 weeks) + Olfactory training (idem as in intervention group) |

Final OFS, Change in OFS, Change in OD classification |

No |

CCCRC, VAS-score at 0, 12 weeks |

Significant improvement in both groups, but no difference between groups No improvement in Change in OD classification |

|

|

Vitamin A nasal drops (2drops 10.000 IU per each nostril once daily) |

|||||||||

| [50] | NRS |

Nasal theophylline (400 mg theophylline tablet diluted in 240 mL isotonic nasal saline, irrigation each nostril twice daily) |

Nasal saline irrigation (Isotonic saline in each nostril twice daily for 1 month) |

Recovery rate, OD duration |

No |

VAS-score at 0, 1, 2, 3, 4 weeks |

No difference between groups at 4 weeks (recovery rate) Significant improvement in OD duration between groups |

||

|

Corticosteroid nasal spray (Mometasone Furoate of 100 µg 2 puffs/nostril twice daily for four weeks) |

|||||||||

|

Intranasal Vitamin A&E (solution of Vitamin A palmitate 15 000 UI/ml + Vitamin E acetate 20 mg/ml twice daily) + Olfactory training (idem as in comparison group) |

Sniffin’ Sticks Threshold at 0, 3 months |

||||||||

| [35] | NRS | 47 |

Corticosteroid nasal spray (50 μg mometasone twice daily) + Olfactory training (idem as in comparison group) |

Olfactory training (sniffing four scents for 15 s each three times daily) |

Change in OFS | No | All significant improvement, with adjuvant therapy more | ||

|

Corticosteroid nasal spray (50 μg mometasone twice daily) + Multivitamin supplement (0.2 mg of B1, 200 mg of B6 and 100 mg of B12 twice daily) + Olfactory training (idem as in comparison group) |

|||||||||

| PEA-LUT | |||||||||

| [54] | RCT | 130 |

PEA/Luteolin supplement (PEA 700 mg and Luteolin 70 mg once daily for 90 days) + Olfactory training (idem as in comparison group) |

Placebo (multivitamin, vitamin D 400 UI, and/or alpha-lipoic acid 120 mg daily for 90 days) + Olfactory training (sniffing four scents 20 s each, three times every day for 6 min each session) |

Recovery rate, Final OFS |

Yes |

Sniffin’ Sticks identification, Parosmia questionnaire at 0, 90 days after treatment |

No improvement of Parosmia Significant improvement of quantitative OD |

|

| [53] | RCT | 250 |

PEA/Luteolin supplement (PEA 700 mg and Luteolin 70 mg once daily for 90 days) + Olfactory training (idem as in comparison group) PEA/Luteolin supplement (PEA 700 mg and Luteolin 70 mg twice daily for 90 days) PEA/Luteolin supplement (PEA 700 mg and Luteolin 70 mg once daily for 90 days) |

Placebo (multivitamin, vitamin D 400 UI, and/or alpha-lipoic acid 120 mg daily for 90 days) + Olfactory training (sniffing four scents 20 s each, three times every day for 6 min each session) |

Final OFS | No |

Sniffin’ Sticks identification test at 0, 30, 60, 90 days |

Significant improvement in all groups at 90 days Most significant improvement in PEA-LUT + OT group |

|

| [52] | RCT | 185 |

PEA/Luteolin supplement (PEA 700 mg and Luteolin 70 mg once daily for 90 days) + Olfactory training (idem as in comparison group) |

Placebo (multivitamin, vitamin D 400 UI, and/or alpha-lipoic acid 120 mg daily for 90 days) + Olfactory training (sniffing four scents 6 s each, three times daily for 6 min each session for 90 days) |

Finals OFS | No |

TDI at 0, 90 days |

Significant improvement in intervention group | |

| [51] | RCT | 12 |

PEA/Luteolin supplement (PEA 700 mg and Luteolin 70 mg once daily for 30 days) + Olfactory training (idem as in comparison group) |

Olfactory training (a sniffing session of 10 min twice daily for 30 days) |

Final OFS | No |

TDI at 0, 60 days |

Significant improvement in intervention group No significant improvement in control group |

|

| Calcium chelators | |||||||||

| [44] | RCT | 66 |

Pentasodium diethylenetriamine pentaacetate (Intranasal 2% DTPA-containing nasal spray, three times daily for 1 month) |

Nasal saline spray (Intranasal 0.9% sodium chloride, three times daily for 1 month) |

Final OFS, Change in OD classification |

No |

TDI at 0, 1 month |

Significant improvement | |

| [47] | RCT | 50 |

Ethylene diamine tetra acetic acid spray (Intranasal 1% EDTA in phosphate buffer solution, pH 7.5 three times daily for 3 month) + Olfactory training (same as comparison group) |

Olfactory training (sniffing four scents daily for 3 months) |

Change in OFS, Final OFS |

No |

TDI at 0, 3 month |

Significant improvement in both groups, Intervention group more | |

| [46] | RCT | 50 |

Sodium Gluconate spray (sodium gluconate in borate buffer solution, pH 8, three times daily for 1 month |

Nasal saline spray (Intranasal 0.9% sodium chloride, three times daily for 1 month) |

Final OFS, Change in OFS, Change in OD classification |

No |

TDI at 0, 1 month |

Significant improvement | |

| [45] | RCT | 64 |

Tetra sodium pyrophosphate spray (Intranasal 1% TSPP in borate buffer solution with a pH of 8, three times daily for 1 month) |

Nasal saline spray (Intranasal 0.9% sodium chloride, three times daily for 1 month) |

Final OFS, Change in OFS, Change in OD classification |

No |

TDI at 0, 1 month |

Significant improvement | |

| Insulin | |||||||||

| [55] | RCT | 40 |

Insulin fast-dissolving film (application of insulin fast-dissolving film 100 units twice weekly for four weeks) |

Placebo fast-dissolving film (application of placebo film twice weekly for four weeks) |

Final OFS | No |

Olfactory discrimination and threshold test at 0, 1, 2, 3, 4 weeks |

Significant improvement | |

| Gabapentin | |||||||||

| [56] | RCT | 188 |

Oral Gabapentin (titrated to a maximum tolerable dose, maintained during an 8-week fixed-dose phase, then tapered off) |

Placebo (same appearing pills) |

Change in OFS | Yes |

UPSIT, ODOR, NASAL-7, CGI-S, CGI-P at 0, 8, 12 weeks |

No improvement | |

| Cerebrolysin | |||||||||

| [57] | RCT | 250 |

Cerebrolysin injection (5 ml/d x 5 day/week through intramuscular injection for ≥ 8–24 weeks) + Olfactory, gustatory training (idem as comparison group) |

Olfactory, gustatory training (sniffing four scents for 20 s each twice daily for ≥ 8–24 weeks) |

Final OFS, Recovery rate |

Yes |

SOIT, GRS, Flavor identification test, at 0, 8, 12, 18, 24 weeks |

Significant improvement of Parosmia and SOIT |

RCT randomised clincial trial, NRS non-randomised studies, OFS olfactory function sceore

Fig. 3.

Forest plot of the effect of (A) platelet-rich plasma (PRP), (B) palmitoylethanolamide and luteolin (PEA-LUT) and (C) calcium chelators

Calcium Chelators

In the past years 4 RCTs have been published regarding lowering the calcium level intranasally (Table 3) [44–47]. All studies were conducted by the same research group in Egypt. In each study, a different intranasal spray was used, all of which aimed to lower the calcium levels in the nose and enhance the sense of smell. The overall SMD favours the calcium chelators, with a pooled SMD of 0.75 [95% CI: 0.46, 1.04], indicating a statistically significant positive effect (p < 0.00001) (Fig. 3). The heterogeneity is low (I2 = 12%), indicating that the results are relatively consistent across studies, which is not surprising since all the included studies were performed by the same team in Egypt. Each study individually demonstrates a positive effect, all favouring the calcium buffer intervention.

Vitamin Supplements

In this section, we included all studies using vitamin supplements, either orally or intranasally administered, to evaluate the effect on olfactory function. Five studies, three RCTs and two non-randomised trials, were included (Table 3) [26, 35, 48–50]. A 2023 RCT by Lerner involving 139 patients, examined the impact of oral omega-3 supplementation (“Omega-3 Fish Oil”) compared to placebo [48]. No significant improvement was observed on the final OFS between the two groups.

Another RCT by Chung in 2023 with 56 participants, evaluated the combination of oral vitamin A supplementation and OT [26]. This intervention led to significant improvements in the OFS scores within the treatment group, whereas no significant improvements were observed in the control group.

Figueiredo’s 2023 RCT, which included 128 participants, evaluated the effects of alpha-lipoic acid combined with OT compared to a placebo [49]. Both the intervention and placebo groups showed significant improvements in the OFS. However, there was no significant difference between the groups regarding changes in olfactory dysfunction classification.

A preprint study by Abu Shaby in 2023 used a non-randomized design to compare nasal theophylline to isotonic saline irrigation alone [50]. This study found a significant improvement in the VAS-score of OD in the theophylline group.

Finally, a 2022 non-randomized study by Sousa with 47 participants explored the use of mometasone nasal spray (50 µg twice daily) in combination with OT [35]. An additional group received a multivitamin supplement along with the nasal spray and training. Both groups demonstrated significant improvements.

Palmitoylethanolamide with Luteolin (PEA-LUT)

Four RCTs described the effect of PEA-LUT (Table 3) [51–54]. All studies were conducted by the same research group in Italy. The overall SMD is 0.97 [95% CI: -0.02, 1.95] and with very low heterogeneity among the studies (I2 = 0%), indicating consistent results across studies. The individual SMDs range from 0.14 to 1.61, with Di Stadio (2023a) and Di Stadio (2023b) demonstrating the most positive effects. The analysis suggests that the PEA-LUT intervention may have a beneficial effect compared to the control; however, the overall effect is not statistically significant (p = 0.06) (Fig. 3).

Insulin

One RCT was published, involving 49 patients, describing local insulin application as a treatment for OD (Table 3) [55]. Twice a week for 4 weeks fast dissolving insulin was applied at the olfactory cleft. At the end of the therapy, a clinically significant improvement of OFS was seen. No serious adverse effects were mentioned.

Gabapentin

One RCT was identified that investigated the use of oral gabapentin as a treatment (Table 3) [56]. 188 patients were involved and received gabapentin titrated to a maximum tolerable dose, maintained during an 8-week fixed-dose phase, then tapered off. There were no serious adverse events, but some patients suffered of fatigue, dizziness, weight gain or brain fog. Overall, there was no clinical improvement in OFS nor parosmia.

Cerebrolysin

One RCT described the treatment effect of cerebrolysin on olfactory function (Table 3) [57]. This study included 250 patients receiving 5 ml cerebrolysin 5 days a week through intramuscular injection for ≥ 8–24 weeks. Intervention and control group performed both concomitant olfactory and gustatory training. At the end of the therapy, a clinically significant improvement of OFS and parosmia was measured. No serious adverse effects were described.

Discussion

In this systematic review, we present a structured overview of treatment options for COVID-19 associated olfactory dysfunction, analyzing various therapeutic strategies and their efficacy. To date, there is only one living systematic (Cochrane) review, which has included only two studies due to its rigorous inclusion criteria and exclusive focus on randomized controlled trials (RCTs) [58].

Our search yielded a total of 36 studies published between 2019 and 2023. We grouped these studies into 9 different treatment categories: OT, topical and systemic CS, PRP, calcium chelators, vitamin supplements, PEA-LUT, insulin, gabapentin and cerebrolysin. We included only studies with patients experiencing OD for at least one month to account for the high rate of spontaneous recovery within the first month [59]. Therefore, two studies were excluded because they recruited patients with OD lasting more than one month, but conducted olfactory function tests within two weeks of OD onset without subsequent testing after starting the treatment. This exclusion ensures that the included studies focus on patients with persistent OD, providing a more accurate assessment of treatment efficacy and size effect [60, 61].

A descriptive synthesis of the effects of the different intervention modalities was done, considering subjective and objective/psychophysical outcome parameters. For the quantitative analysis, however, we exclusively included studies with objective testing. While some studies demonstrate a significant association between subjective (VAS-score, Likert-scale) and objective olfactory function, others indicate a lack of correlation [62–64]. The discrepancy underscores the importance of conducting objective testing and reducing the potential biases and variabilities in subjective self-assessments. Due to the inclusion of objective testing studies only for quantitative OD, 2 studies were excluded.

OD significantly impacts quality of life, as it affects various daily activities and overall well-being.[65, 66]. However, QoL questionnaires, while valuable in assessing the broader impact of OD, do not directly measure olfactory function itself. Consequently, they were excluded from the quantitative analysis to ensure that the evaluation remained focused on direct, objective measures of olfactory function.

In the following section, we will focus on the three most significant treatment modalities, identified in our systematic review: olfactory training, corticosteroids, and PRP. These treatments have been more frequently and extensively studied, offering more substantial evidence of their efficacy in managing olfactory dysfunction.

Olfactory Training

OT, which typically involves regularly smelling specific scents, is widely suggested as a first-line treatment for post-infectious OD, including COVID-19 associated OD.

Aims to retrain the brain to accurately interpret the neurological signals generated when odorants are detected, which then travel through the olfactory nerve, olfactory bulb, and olfactory cortex [8].

The relatively low cost, the non-invasive nature and absence of associated complications, supports its use as first-line therapy. This therapy was firstly presented by Hummel et al., with a clinically significant improvement on olfaction in patients with post-infectious, post-traumatic, and idiopathic olfactory loss [67]. A meta-analysis of 2016 found benefit in the total TDI scores as well as odour identification and discrimination [10]. Further, functional magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies demonstrated alterations in connectivity among cortical olfactory networks after OT [68]. However, no control group was included in the latter study.

Pieniak et al. stated that OT can be considered as an established method for smell rehabilitation, supporting cognitive functions in both developmental and aging processes [69].

In our analysis, OT showed no significant overall impact compared to control groups. This suggests that, while OT is a widely recommended non-pharmacological intervention and considered as the standard of care for post-viral OD, its efficacy may not be as substantial in COVID-19 associated OD as previously thought. OT has been adopted as a foundational treatment in general otorhinolaryngology practices, even though the mechanisms of action are not well understood.

In addition, it is important to note that the duration of OT in the included studies ranged from one and a half to three months. This variability must be considered, as prior researches recommend a minimum training duration of three months to observe potential effects [8, 70]. Therefore, we can only conclude that short-term OT does not significantly improve OD.

Furthermore,while there is a slight numerical trend indicating better results for patients with a shorter duration of olfactory dysfunction (less than 3 months), the differences between the subgroups are minimal, and the confidence intervals overlap. This suggests that the duration of smell loss does not have a strong or significant effect. With such a small number of studies per subgroup, however, it’s difficult to draw conclusions about the impact of the duration of smell loss on the effectiveness of OT.

Corticosteroids

The use of topical corticosteroids carries some controversy. For instance, a systematic review highlighted that, while topical corticosteroids showed some potential in improving olfactory function, systemic corticosteroids did not demonstrate a significant benefit over placebo treatments in most studies reviewed [13]. However, another study showed no beneficial effect [71].Our results suggest that intranasal corticosteroids might provide some benefit for COVID-19-associated OD, although the evidence is not statistically significant. Furthermore, systemic corticosteroids do not appear to offer significant benefits for improving olfactory function, aligning with other research findings. It is important to note that our study did not consider different application methods, such as nasal irrigations, sprays or specific head positions, which could potentially influence the efficacy of the treatments. As Helman et al. stated in their systematic review on treatment strategies for post-viral OD, that studies that examined the efficacy of nasal corticosteroid spray should be interpreted with consideration of the administration method [72]. The administration of topical steroids via irrigations may increase delivery of medication to the olfactory cleft compared with standard nasal spray administration, and this effect may be augmented by using special head positions [73].

Despite the limited evidence on the efficacy of systemic corticosteroids for olfactory dysfunction, we must remain vigilant about their potentially severe adverse effects. The recent EAACI position paper on the benefits and harms of systemic steroids also reports the short- term effects of corticosteroids used in upper airway disease [74].

PRP

The growth factors in PRP, such as vascular endothelial growth factor and epidermal growth factor, contribute significantly to tissue regeneration and may play a role in olfactory recovery by promoting neurogenesis and modulating the inflammatory response [75]. A systematic review and meta-analysis examined the efficacy of PRP for treating persistent olfactory impairment, including post-COVID-19 and post-infectious cases [75]. The analysis revealed significant improvements in olfactory function. However, substantial inter-study heterogeneity was noted. Our findings suggest a statistically significant improvement in olfactory function with PRP treatment, aligning with studies that have reported beneficial outcomes. However, the substantial variability among studies highlights the need for standardized protocols and further large-scale RCTs to validate these results comprehensively.

The heterogeneity in some treatment outcomes complicates direct comparisons and limits definitive conclusions. Moreover, the inclusion of studies conducted by the same research teams could introduce bias, emphasizing the need for broader, multicentric trials.

Future research should, therefore, focus on two main areas to address the challenges in treating OD following COVID-19. First, standardizing treatment protocols and outcome assessments is essential to reduce heterogeneity and allow for more direct comparisons across studies. This standardization would facilitate the identification of the most effective interventions and ensure consistency in measuring their outcomes. Additionally, long-term studies are necessary to determine the long-term efficacy of various interventions.

Second, further research on the underlying pathophysiology of OD is important. A deeper understanding of the mechanisms by which SARS-CoV-2 causes OD could guide finding targeted treatment options [76, 77]. For instance, if scarring or fibrosis is identified as a key factor, then agents that inhibit fibrosis formation might be useful. Similarly, insights into the role of inflammation could lead to the use of anti-inflammatory drugs. By elucidating the pathophysiological mechanisms involved in COVID-19 associated OD, researchers can develop more effective and specific treatment strategies, ultimately improving the quality of life for those affected by this condition.

Nonetheless, in this systematic review, we have provided an overview of the most recently published studies regarding therapy options for COVID-19 associated OD. By highlighting the current state of research and the need for further studies, we aim to contribute to the ongoing efforts to find effective treatments for this challenging condition.

Conclusion

In conclusion, while several therapeutic options show promise for treating COVID-19-associated OD, the available evidence remains inconclusive. Olfactory training, intranasal corticosteroids, and PRP are potential interventions, but their efficacy varies. Calcium chelators and certain vitamin supplements offer hope, yet require further validation. Continued research is essential to establish clear, evidence-based guidelines for managing persistent OD in COVID-19 patients.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Author Contribution

The pre-published protocol and the search strategy was developed by MC and A V. SB and MM screened titles and abstracts for eligibility. Full texts and risk of bias were also assessed by SB and MM according to the inclusion criteria. SB and MM wrote the main manuscript text, prepared the figures and tables. LVG served as the supervising professor, contributing to the overall guidance and coordination of the project and reviewed the manuscript.

Funding

Laura Van Gerven was supported by Research Foundation Flanders (FWO): Senior Clinical Investigator Fellowship 18B2222N.

Data Availability

Some Data are provided within the manuscript as supplementary information (search strategy).

Declarations

Human and Animal Rights

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Competing Interest

HippoDx (stocks and scientific advisory board), speakers fees from GSK.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Sabrina Bischoff and Mathilde Moyaert are shared first authors and contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Tong JY, Wong A, Zhu D, Fastenberg JH, Tham T. The prevalence of olfactory and gustatory dysfunction in COVID-19 patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2020;163(1):3–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Borsetto D, Hopkins C, Philips V, Obholzer R, Tirelli G, Polesel J, et al. Self-reported alteration of sense of smell or taste in patients with COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis on 3563 patients. Rhinology. 2020;58(5):430–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hannum ME, Ramirez VA, Lipson SJ, Herriman RD, Toskala AK, Lin C, et al. Objective sensory testing methods reveal a higher prevalence of olfactory loss in COVID-19-positive patients compared to subjective methods: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Chem Senses. 2020;45(9):865–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hu S, Zhang S, You Y, Tang J, Chen C, Wang C, et al. Olfactory dysfunction after COVID-19: metanalysis reveals persistence in one-third of patients 6 months after initial infection. J Infect. 2023;86(5):516–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Whitcroft KL, Altundag A, Balungwe P, Boscolo-Rizzo P, Douglas R, Enecilla MLB, et al. Position paper on olfactory dysfunction: 2023. Rhinology. 2023;61(33):1–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.O’Byrne L, Webster KE, MacKeith S, Philpott C, Hopkins C, Burton MJ. Interventions for the treatment of persistent post-COVID-19 olfactory dysfunction. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2022;9(9):13876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hwang SH, Kim SW, Basurrah MA, Kim DH. The efficacy of olfactory training as a treatment for olfactory disorders caused by coronavirus disease-2019: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2023;37(4):495–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Delgado-Lima AH, Bouhaben J, Delgado-Losada ML. The efficacy of olfactory training in improving olfactory function: a meta-analysis. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2024;281(10):5267–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fornazieri MA, Garcia ECD, Lopes NMD, Miyazawa INI, Silva GDS, Monteiro RDS, et al. Adherence and efficacy of olfactory training as a treatment for persistent olfactory loss. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2020;34(2):238–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pekala K, Chandra RK, Turner JH. Efficacy of olfactory training in patients with olfactory loss: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2016;6(3):299–307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Turner JH. Olfactory training: what is the evidence? Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2020;10(11):1199–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Langdon C, Lehrer E, Berenguer J, Laxe S, Alobid I, Quintó L, et al. Olfactory training in post-traumatic smell impairment: mild improvement in threshold performances: results from a randomized controlled trial. J Neurotrauma. 2018;35(22):2641–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Winn PZ, Hlaing T, Tun KM, Lei SL. Effect of any form of steroids in comparison with that of other medications on the duration of olfactory dysfunction in patients with COVID-19: A systematic review of randomized trials and quasi-experimental studies. PLoS ONE. 2023;18(8):e0288285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hopkins C, Alanin M, Philpott C, Harries P, Whitcroft K, Qureishi A, et al. Management of new onset loss of sense of smell during the COVID-19 pandemic - BRS Consensus Guidelines. Clin Otolaryngol. 2021;46(1):16–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim DH, Kim SW, Kang MJ, Hwang SH. Efficacy of topical steroids for the treatment of olfactory disorders caused by COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Otolaryngol. 2022;47(4):509–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rochet M, El-Hage W, Richa S, Kazour F, Atanasova B. Depression, olfaction, and quality of life: a mutual relationship. Brain Sci. 2018;8(5):80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hummel T, Nordin S. Olfactory disorders and their consequences for quality of life. Acta Otolaryngol. 2005;125(2):116–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hummel T, Sekinger B, Wolf SR, Pauli E, Kobal G. ‘Sniffin’ sticks’: olfactory performance assessed by the combined testing of odor identification, odor discrimination and olfactory threshold. Chem Senses. 1997;22(1):39–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Doty RL, Shaman P, Dann M. Development of the university of pennsylvania smell identification test: A standardized microencapsulated test of olfactory function. Physiol Behav. 1984;32(3):489–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Doty RL, Marcus A, Lee WW. Development of the 12-item cross-cultural smell identification test (CC-SIT). Laryngoscope. 1996;106(3 Pt 1):353–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cain WS, Gent JF, Goodspeed RB, Leonard G. Evaluation of olfactory dysfunction in the connecticut chemosensory clinical research center. Laryngoscope. 1988;98(1):83–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Berube S, Demers C, Pek V, Chen A, Bussiere N, Cloutier F, et al. Effects of olfactory training on olfactory dysfunction induced by COVID-19. ORL. 2022;85(2):57–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pires IDT, Steffens ST, Mocelin AG, Shibukawa DE, Leahy L, Saito FL, et al. Intensive olfactory training in post-covid-19 patients: a multicenter randomized clinical trial. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2022;36(6):780–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lechner M, Liu J, Counsell N, Gillespie D, Chandrasekharan D, Ta NH, et al. The COVANOS trial - insight into post-COVID olfactory dysfunction and the role of smell training. Rhinology. 2022;60(3):188–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aldundag A, Yilmaz E, Kesimli MC. Modified olfactory training is an effective treatment method for COVID-19 induced parosmia. Laryngoscope. 2022;132(7):1433–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chung TWH, Zhang H, Wong FKC, Sridhar S, Lee TMC, Leung GKK, et al. A pilot study of short-course oral vitamin A and aerosolised diffuser olfactory training for the treatment of smell loss in long COVID. Brain Sci. 2023;13(7):1014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.De Luca P, Camaioni A, Marra P, Salzano G, Carriere G, Ricciardi L, et al. Effect of ultra-micronized palmitoylethanolamide and luteolin on olfaction and memory in patients with long COVID: Results of a longitudinal study. Cells. 2022;11(16):2552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pendolino AL, Ottaviano G, Nijim J, Scarpa B, De Lucia G, Berro C, et al. A multicenter real-life study to determine the efficacy of corticosteroids and olfactory training in improving persistent COVID-19-related olfactory dysfunction. Laryngoscope Invest Otolaryngol. 2023;8(1):46–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bérubé S, Demers C, Bussière N, Cloutier F, Pek V, Chen AEL, et al. Olfactory training impacts olfactory dysfunction induced by COVID-19: A pilot study. Orl-J Oto-Rhino-Laryngol Head Neck Surg. 2023;85(2):57–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hosseinpoor M, Kabiri M, Haghi MR, Soltani TG, Rezaei A, Faghfouri A, et al. Intranasal corticosteroid treatment on recovery of long-term olfactory dysfunction due to COVID-19. Laryngoscope. 2022;132(11):2209–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hintschich CA, Dietz M, Haehner A, Hummel T. Topical administration of mometasone is not helpful in post-COVID-19 olfactory dysfunction. Life-Basel. 2022;12(10):1483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hautefort C, Corre A, Poillon G, Jourdaine C, Housset J, Eliezer M, et al. Local budesonide therapy in the management of persistent hyposmia in suspected non-severe COVID-19 patients: Results of a randomized controlled trial. Int J Infect Dis. 2023;136:70–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schmidt F, Azar C, Goektas O. Treatment of Olfactory Disorders After SARS - CoViD 2 Virus Infection. Ent-Ear Nose Throat J. 2023;103(1):48S-53S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lasheen H, Abou-Zeid MA. Olfactory mucosa steroid injection in treatment of post-COVID-19 olfactory dysfunction: a randomized control trial. Egypt J Otolaryngol. 2023;39(1):118. [Google Scholar]

- 35.de Sousa FA, Machado AS, da Costa JC, Silva AC, Pinto AN, Coutinho MB, et al. Tailored approach for persistent olfactory dysfunction after SARS-CoV-2 infection: A pilot study. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2023;132(6):657–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vaira LA, Hopkins C, Petrocelli M, Lechien JR, Cutrupi S, Salzano G, et al. Efficacy of corticosteroid therapy in the treatment of long-lasting olfactory disorders in COVID-19 patients. Rhinology. 2021;59(1):21–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schepens EJA, Blijleven EE, Boek WM, Boesveldt S, Stokroos RJ, Stegeman I, et al. Prednisolone does not improve olfactory function after COVID-19: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. BMC Med. 2022;20(1):445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Le Bon SD, Konopnicki D, Pisarski N, Prunier L, Lechien JR, Horoi M. Efficacy and safety of oral corticosteroids and olfactory training in the management of COVID-19-related loss of smell. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2021;278(8):3113–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Evman MD, Cetin ZE. Effectiveness of platelet-rich plasma on post-COVID chronic olfactory dysfunction. Rev Assoc Méd Bras. 2023;69(11):e20230666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yan CH, Jang SS, Lin HF, Ma Y, Khanwalker AR, Thai A, et al. Use of platelet-rich plasma for COVID-19 related olfactory loss, a randomized controlled trial. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2022;13(6):989–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Steffens Y, Le Bon SD, Lechien J, Prunier L, Rodriguez A, Saussez S, et al. Effectiveness and safety of PRP on persistent olfactory dysfunction related to COVID-19. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2022;279(12):5951–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lechien JR, Saussez S, Vaira LA, De Riu G, Boscolo-Rizzo P, Tirelli G, et al. Effectiveness of Platelet-Rich Plasma for COVID-19-Related Olfactory Dysfunction: A Controlled Study. Otolaryngol-Head Neck Surg. 2023;170(1):84–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Abo El Naga HA, El Zaiat RS, Hamdan AM. The potential therapeutic effect of platelet-rich plasma in the treatment of post-COVID-19 parosmia. Egypt J Otolaryngol. 2022;38(1):130. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Imam MS, Abdelazim MH, Abdelazim AH, Ismaiel WF, Gamal M, Abourehab MAS, et al. Efficacy of pentasodium diethylenetriamine pentaacetate in ameliorating anosmia post COVID-19. Am J Otolaryngol. 2023;44(4):103871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Abdelazim MH, Abdelazim AH, Moneir W. The effect of intra-nasal tetra sodium pyrophosphate on decreasing elevated nasal calcium and improving olfactory function post COVID-19: a randomized controlled trial. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol. 2022;18(1):67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Abdelazim MH, Abdelazim AH. Effect of sodium gluconate on decreasing elevated nasal calcium and improving olfactory function post COVID-19 infection. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2022;36(6):841–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Abdelazim MH, Mandour Z, Abdelazim AH, Ismaiel WF, Gamal M, Abourehab MAS, et al. Intra nasal use of ethylene diamine tetra acetic acid for improving olfactory dysfunction post COVID-19. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2023;37(6):630–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lerner DK, Garvey KL, Arrighi-Allisan A, Kominsky E, Filimonov A, Al-Awady A, et al. Omega-3 fatty acid supplementation for the treatment of persistent COVID-related olfactory dysfunction. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2023;37(5):531–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Figueiredo LP, Paim P, Cerqueira-Silva T, Barreto CC, Lessa MM. Alpha-lipoic acid does not improve olfactory training results in olfactory loss due to COVID-19: a double-blind randomized trial. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2023;90(1):101356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.M SESAMAG. Different modalities in the management of post-COVID-19 olfactory dysfunction.Preprint. 2023.

- 51.D’ascanio L, Vitelli F, Cingolani C, Maranzano M, Brenner MJ, Di Stadio A. Randomized clinical trial “olfactory dysfunction after COVID-19: Olfactory rehabilitation therapy vs. intervention treatment with Palmitoylethanolamide and Luteolin”: Preliminary results. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2021;25(11):4156–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Di Stadio A, D’Ascanio L, Vaira LA, Cantone E, De Luca P, Cingolani C, et al. Ultramicronized palmitoylethanolamide and luteolin supplement combined with olfactory training to treat post-COVID-19 olfactory impairment: A multi-center double-blinded randomized placebo-controlled clinical trial. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2022;20(10):2001–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Di Stadio A, Gallina S, Cocuzza S, De Luca P, Ingrassia A, Oliva S, et al. Treatment of COVID-19 olfactory dysfunction with olfactory training, palmitoylethanolamide with luteolin, or combined therapy: a blinded controlled multicenter randomized trial. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2023;280(11):4949–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Di Stadio A, Cantone E, De Luca P, Di Nola C, Massimilla EA, Motta G, et al. Parosmia COVID-19 related treated by a combination of olfactory training and ultramicronized PEA-LUT: A prospective randomized controlled trial. Biomedicines. 2023;11(4):1109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mohamad SA, Badawi AM, Mansour HF. Insulin fast-dissolving film for intranasal delivery via olfactory region, a promising approach for the treatment of anosmia in COVID-19 patients: Design, in-vitro characterization and clinical evaluation. Int J Pharm. 2021;601:120600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mahadev A, Hentati F, Miller B, Bao JM, Perrin A, Kallogjeri D, et al. Efficacy of gabapentin for post-COVID-19 olfactory dysfunction. Jama Otolaryngol-Head Neck Surg. 2023;149(12):1111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hamed SA, Ahmed MAAR. The effectiveness of cerebrolysin, a multi-modal neurotrophic factor, for treatment of post-covid-19 persistent olfactory, gustatory and trigeminal chemosensory dysfunctions: a randomized clinical trial. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2023;16(12):1261–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Webster KE, O’Byrne L, MacKeith S, Philpott C, Hopkins C, Burton MJ. Interventions for the prevention of persistent post-COVID-19 olfactory dysfunction. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2022;9(9):Cd013877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.D’Ascanio L, Pandolfini M, Cingolani C, Latini G, Gradoni P, Capalbo M, et al. Olfactory dysfunction in COVID-19 patients: Prevalence and prognosis for recovering sense of smell. Otolaryngol-Head Neck Surg. 2021;164(1):82–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lechien JR, Vaira LA, Saussez S. Effectiveness of olfactory training in COVID-19 patients with olfactory dysfunction: a prospective study. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2023;280(3):1255–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Khan AM, Piccirillo J, Kallogjeri D, Piccirillo JF. Efficacy of combined visual-olfactory training with patient-preferred scents as treatment for patients with COVID-19 Resultant Olfactory loss: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Otolaryngol-Head Neck Surg. 2023;149(2):141–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Heian IT, Helvik AS, Hummel T, Øie MR, Nordgård S, Bratt M, et al. Measured and self-reported olfactory function in voluntary Norwegian adults. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2022;279(10):4925–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Landis BN, Hummel T, Hugentobler M, Giger R, Lacroix JS. Ratings of overall olfactory function. Chem Senses. 2003;28(8):691–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Welge-Luessen A, Hummel T, Stojan T, Wolfensberger M. What is the correlation between ratings and measures of olfactory function in patients with olfactory loss? Am J Rhinol. 2005;19(6):567–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Croy I, Nordin S, Hummel T. Olfactory disorders and quality of life–an updated review. Chem Senses. 2014;39(3):185–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zou LQ, Hummel T, Otte MS, Bitter T, Besser G, Mueller CA, et al. Association between olfactory function and quality of life in patients with olfactory disorders: a multicenter study in over 760 participants. Rhinology. 2021;59(2):164–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hummel T, Rissom K, Reden J, Hähner A, Weidenbecher M, Hüttenbrink K-B. Effects of olfactory training in patients with olfactory loss. Laryngoscope. 2009;119(3):496–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kollndorfer K, Kowalczyk K, Hoche E, Mueller CA, Pollak M, Trattnig S, et al. Recovery of olfactory function induces neuroplasticity effects in patients with smell loss. Neural Plast. 2014;2014:140419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Pieniak M, Oleszkiewicz A, Avaro V, Calegari F, Hummel T. Olfactory training - Thirteen years of research reviewed. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2022;141:104853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Konstantinidis I, Tsakiropoulou E, Constantinidis J. Long term effects of olfactory training in patients with post-infectious olfactory loss. Rhinology. 2016;54(2):170–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Chen RD, Yang CW, Chen XB, Hu HF, Cui GZ, Zhu QR, et al. Therapeutic efficacy of nasal corticosteroids in COVID-19-related olfactory dysfunction: A comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2024;170(4):999–1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Helman SN, Adler J, Jafari A, Bennett S, Vuncannon JR, Cozart AC, et al. Treatment strategies for postviral olfactory dysfunction: A systematic review. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2022;43(2):96–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Trabut S, Friedrich H, Caversaccio M, Negoias S. Challenges in topical therapy of chronic rhinosinusitis: The case of nasal drops application - A systematic review. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2020;47(4):536–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hox V, Lourijsen E, Jordens A, Aasbjerg K, Agache I, Alobid I, et al. Benefits and harm of systemic steroids for short- and long-term use in rhinitis and rhinosinusitis: an EAACI position paper. Clin Transl Allergy. 2020;10:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Aaraj MA, Boorinie M, Salfity L, Eweiss A. The use of platelet rich plasma in covid-19 induced olfactory dysfunction: Systematic review. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2023;75(4):1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Khan M, Yoo SJ, Clijsters M, Backaert W, Vanstapel A, Speleman K, et al. Visualizing in deceased COVID-19 patients how SARS-CoV-2 attacks the respiratory and olfactory mucosae but spares the olfactory bulb. Cell. 2021;184(24):5932-49.e15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Khan M, Clijsters M, Choi S, Backaert W, Claerhout M, Couvreur F, et al. Anatomical barriers against SARS-CoV-2 neuroinvasion at vulnerable interfaces visualized in deceased COVID-19 patients. Neuron. 2022;110(23):3919-35.e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Some Data are provided within the manuscript as supplementary information (search strategy).