Abstract

Diabetes mellitus, characterized by chronic hyperglycemia due to insulin deficiency or resistance, poses a significant global health burden. Central to its pathogenesis is the dysfunction or loss of pancreatic beta cells, which are res-ponsible for insulin production. Recent advances in beta-cell regeneration research offer promising strategies for diabetes treatment, aiming to restore endogenous insulin production and achieve glycemic control. This review explores the physiological basis of beta-cell function, recent scientific advan-cements, and the challenges in translating these findings into clinical applications. It highlights key developments in stem cell therapy, gene editing technologies, and the identification of novel regenerative molecules. Despite the potential, the field faces hurdles such as ensuring the safety and long-term efficacy of regen-erative therapies, ethical concerns around stem cell use, and the complexity of beta-cell differentiation and integration. The review highlights the importance of interdisciplinary collaboration, increased funding, the need for patient-centered approaches and the integration of new treatments into comprehensive care strategies to overcome these challenges. Through continued research and collaboration, beta-cell regeneration holds the potential to revolutionize diabetes care, turning a chronic condition into a manageable or even curable disease.

Keywords: Diabetes therapies, Beta cell regeneration, Regenerative medicine, Stem cell therapy, Gene editing, Molecular therapeutics

Core Tip: Diabetes, a disease of uncontrolled blood sugar, arises from the loss or dysfunction of insulin-producing beta cells within the pancreas. While traditional management focuses on external insulin, cutting-edge research explores restoring these beta cells. Strategies include stem cell therapy, gene editing, and discovering molecules that promote beta cell growth. However, ensuring safety, overcoming biological complexities, and navigating the ethics of stem cell use present challenges. Through continued research, funding, and a patient-centered approach, beta-cell restoration offers the potential to move diabetes care from management to a possible cure.

INTRODUCTION

Diabetes mellitus encompasses a group of metabolic disorders characterized by chronic hyperglycemia resulting from defects in insulin secretion, insulin action, or both. The two primary forms are type 1 and type 2 diabetes. Type 1 diabetes, although less common, is primarily an autoimmune condition where the body’s immune system attacks and destroys pancreatic beta cells, leading to an absolute insulin deficiency. This form of diabetes typically manifests in childhood or adolescence but can occur at any age[1]. By contrast, type 2 diabetes, which accounts for approximately 90%-95% of all diabetes cases globally, is primarily driven by insulin resistance, coupled with a relative insulin deficiency due to beta-cell dysfunction. It is often associated with obesity, sedentary lifestyle, and genetic factors, and typically presents in adults, although its incidence is increasing among younger populations[2].

Recently, a newer concept known as type 3 diabetes has emerged, which is closely associated with Alzheimer’s disease and is characterized by insulin resistance and deficiency specifically in the brain. This hypothesis suggests that the brain’s inability to properly utilize insulin could contribute to cognitive decline, adding a neurodegenerative aspect to the complexity of diabetes. Although type 3 diabetes is not yet universally recognized as a formal classification, its implications for both neurodegenerative and metabolic disorders highlight the multifaceted nature of diabetes and the potential overlap in pathophysiological mechanisms[3].

Given the central role of pancreatic beta cells in insulin production, both forms of diabetes could potentially benefit from beta-cell regeneration therapies. For type 1 diabetes, restoring beta-cell mass could replace the destroyed cells, thereby re-establishing endogenous insulin production[4]. In type 2 diabetes, enhancing the function and quantity of beta cells could alleviate insulin deficiency and improve glycemic control, particularly in patients with significant beta-cell loss or dysfunction[5,6]. Although type 3 diabetes involves insulin resistance in the brain rather than beta-cell dysfunction, improving overall insulin signaling and management of glucose metabolism could indirectly support cognitive health and reduce the risk of neurodegenerative diseases[7]. Understanding the underlying pathophysiological mechanisms of the different diabetes subtypes is essential for developing effective therapeutic strategies. Table 1 provides a summary of the pathophysiological pathways in type 1, type 2, and type 3 diabetes.

Table 1.

Key pathophysiological pathways in type 1, type 2, and type 3 diabetes

|

Pathway

|

Type 1 diabetes

|

Type 2 diabetes

|

Type 3 diabetes (Alzheimer’s disease)

|

| Insulin production | Autoimmune destruction of pancreatic beta cells leads to absolute insulin deficiency | Insulin resistance in peripheral tissues leads to compensatory hyperinsulinemia, followed by beta-cell dysfunction and relative insulin deficiency | Insulin resistance and deficiency in the brain contribute to impaired glucose metabolism and cognitive decline |

| Immune system involvement | Autoimmune response targeting beta cells, involving T cell-mediated destruction | Chronic low-grade inflammation contributes to insulin resistance and beta-cell dysfunction | Possible involvement of neuroinflammation and immune dysregulation contributing to neurodegeneration |

| Glucose metabolism | Hyperglycemia due to lack of insulin, resulting in impaired glucose uptake by cells | Hyperglycemia due to insulin resistance and inadequate compensatory insulin secretion by beta cells | Impaired glucose metabolism in the brain leads to reduced energy supply and cognitive impairment |

| Beta-cell function | Progressive loss of beta-cell mass due to autoimmune attack | Gradual decline in beta-cell function due to chronic insulin resistance, oxidative stress, and inflammation | Not directly related to beta cells, but brain insulin signaling impairment is a key factor |

| Associated complications | Ketoacidosis, retinopathy, nephropathy, neuropathy, cardiovascular disease | Retinopathy, nephropathy, neuropathy, cardiovascular disease, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease | Cognitive decline, memory loss, dementia, potential overlap with Alzheimer’s disease |

| Therapeutic targets | Insulin replacement therapy, immunomodulation, beta-cell regeneration | Insulin sensitizers, lifestyle modifications, beta-cell support and regeneration, and anti-inflammatory agents | Improving brain insulin sensitivity, neuroprotective agents, and management of cognitive decline |

Recent research has shifted focus toward regenerative medicine as a promising avenue for diabetes management. The restoration of pancreatic beta cells, which are pivotal in insulin secretion, has emerged as a key target for therapeutic intervention. This approach aims to reestablish endogenous insulin production, potentially transforming diabetes from a chronic condition to a manageable or even curable disease[4,6]. Several innovative strategies are being explored to achieve beta-cell regeneration, including stem cell therapy, gene editing technologies, and the discovery of novel regenerative molecules. Stem cell therapy involves differentiating stem cells into insulin-producing beta cells, offering the potential to replenish the beta-cell population in diabetic patients[8-10]. Gene editing technologies, such as clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)-CRISPR-associated protein 9 (CRISPR-Cas9), provide precise tools to correct genetic defects and enhance beta-cell function, paving the way for personalized medical solutions[11-13]. Additionally, researchers are identifying small molecules and growth factors that can stimulate the proliferation and survival of existing beta cells[14-16].

However, translating these scientific advancements into clinical practice presents significant challenges. Ensuring the safety and long-term efficacy of regenerative therapies is paramount. Ethical concerns, particularly regarding the use of stem cells, must be addressed. Moreover, the complexity of beta-cell differentiation and integration within the existing cellular environment adds another layer of difficulty[17,18]. This review delves into beta-cell function’s physiological basis, highlights the recent scientific advancements, and discusses the challenges in translating these findings into clinical applications. Through continued research and interdisciplinary collaboration, the goal of turning diabetes into a manageable or curable condition appears increasingly attainable.

PHYSIOLOGICAL BASIS OF BETA-CELL FUNCTION

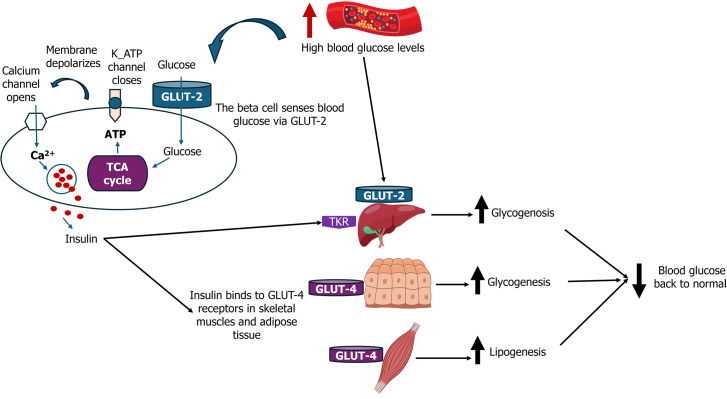

Pancreatic beta cells, located within the islets of Langerhans, play a crucial role in maintaining glucose homeostasis by producing and secreting insulin in response to high blood glucose levels. The intricate processes governing beta-cell function are fundamental to understanding diabetes pathophysiology and developing regenerative therapies[19]. Beta cells synthesize insulin, a peptide hormone essential for glucose uptake in tissues such as muscle and adipose tissue. Insulin secretion is tightly regulated by blood glucose levels through a series of well-coordinated steps. Glucose enters beta cells via glucose transporter type 2 and is metabolized through glycolysis and the citric acid cycle, leading to an increase in the ATP/ADP ratio. This metabolic shift closes ATP-sensitive potassium channels, resulting in cell membrane depolarization. The subsequent opening of voltage-gated calcium channels allows an influx of calcium ions, which triggers the exocytosis of insulin-containing granules[4,15,20]. Figure 1 presents an overview of beta cell function and insulin secretion.

Figure 1.

Overview of beta-cell function and insulin secretion. ATP: Adenosine triphosphate; Ca²+: Calcium ion; GLUT-2: Glucose transporter 2; GLUT-4: Glucose transporter 4; K_ATP: Adenosine triphosphate-sensitive potassium channel; TCA cycle: Tricarboxylic acid cycle.

Beyond glucose, several other factors influence beta-cell function and insulin secretion. Incretins such as glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) enhance insulin secretion in a glucose-dependent manner, linking nutrient intake to insulin release[21]. Additionally, neural and hormonal signals, including parasympathetic innervation and hormones like somatostatin and leptin, modulate beta-cell activity[22-24]. The beta-cell mass and function are dynamically regulated by several mechanisms. Beta cells have the capacity to proliferate in response to metabolic demands and can undergo apoptosis under stress conditions. Under normal physiological conditions, beta-cell turnover in adults is relatively low, with an estimated replication rate of about 0.5%-1% per day[25,26]. However, this rate can increase significantly in response to metabolic stressors such as pregnancy, obesity, or insulin resistance, reflecting the plasticity of beta cells to adapt to changing metabolic needs[27].

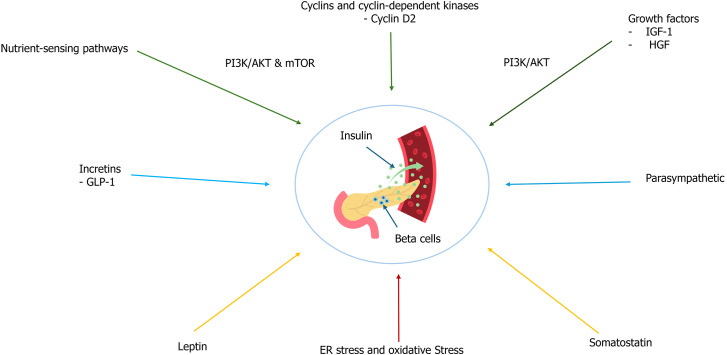

Several key pathways and factors regulate beta-cell proliferation and survival. One of the primary mechanisms involves cell cycle regulators, such as cyclins and cyclin-dependent kinases[28]. Cyclin D2, for instance, is crucial for beta-cell replication and its expression is upregulated in response to increased metabolic demands. This ensures that beta cells can proliferate adequately to meet the body’s insulin requirements[29]. Another critical regulatory mechanism is the nutrient-sensing pathway, particularly the mechanistic target of the rapamycin (mTOR) pathway. This pathway plays a significant role in regulating beta-cell growth and function. Activation of mTOR complex 1 promotes beta-cell proliferation and insulin secretion in response to nutrients and growth factors, highlighting the importance of nutrient availability in beta-cell dynamics[30,31]. Growth factors also play a vital role in beta-cell proliferation and survival. Insulin-like growth factor 1 and hepatocyte growth factor are notable stimulators[32,33]. These growth factors activate signaling pathways such as phosphoinositide 3-kinase/protein kinase B, which enhance beta-cell mass and function. Their role in beta-cell biology underscores the potential of growth factor-based therapies for diabetes[34].

Transcription factors are essential for beta-cell development, identity, and function. Key transcription factors, including pancreatic and duodenal homeobox 1 (PDX1), NK6 homeobox 1, and V-Maf avian musculoaponeurotic fibrosarcoma oncogene homolog A (MAFA), are critical in these processes. PDX1 is vital for pancreatic development and beta-cell maturation, while NK6 homeobox 1 and MAFA maintain beta-cell identity and regulate insulin gene expression[35-37]. These factors ensure the maintenance of the differentiated state and regulate genes involved in insulin synthesis and secretion, making them indispensable in beta-cell physiology.

Beta-cell apoptosis can be triggered by various stressors, including endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress, oxidative stress, and pro-inflammatory cytokines[38]. The intrinsic apoptotic pathway, involving mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization and activation of caspases, is a significant route for beta-cell death under these conditions[39]. Understanding these pathways is crucial for developing interventions to prevent beta-cell loss in diabetes[39]. Figure 2 presents an overview of the factors influencing beta-cell function and insulin secretion.

Figure 2.

Factors influencing beta-cell function and insulin secretion. The green arrow refers to the promotion of beta-cell proliferation. The red arrow refers to promoting beta-cell apoptosis. The blue arrow indicates stimulation of insulin release. The orange arrow indicates inhibiting insulin secretion. AKT: Protein kinase B; ER: Endoplasmic reticulum; GLP-1: Glucagon-like peptide 1; HGF: Hepatocyte growth factor; IGF-1: Insulin-like growth factor 1; mTOR: Mechanistic target of rapamycin; PI3K: Phosphoinositide 3-kinase.

Autophagy, a cellular degradation process, plays a protective role in beta cells by removing damaged organelles and proteins. Proper regulation of autophagy is essential for beta-cell health, and its dysregulation can contribute to beta-cell dysfunction and the progression of diabetes. This highlights the importance of maintaining autophagic balance for beta-cell survival and function[40,41]. Epigenetic modifications, including DNA methylation, histone modifications, and non-coding RNAs such as microRNAs (miRNAs), also play significant roles in modulating beta-cell gene expression and function. These epigenetic changes can affect beta-cell proliferation, survival, and insulin secretion, emphasizing the importance of epigenetic regulation in beta-cell biology[42,43]. Understanding these modifications offers new avenues for therapeutic interventions aimed at preserving or restoring beta-cell function.

MECHANISMS OF BETA-CELL DYSFUNCTION IN DIABETES

In type 1 diabetes, the autoimmune destruction of beta cells leads to an absolute insulin deficiency[1]. Pro-inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin 1 beta, tumor necrosis factor alpha, and interferon gamma play a significant role in inducing beta-cell apoptosis, exacerbating beta-cell loss[44]. The regenerative capacity of beta cells is severely compromised due to the ongoing immune-mediated destruction, preventing effective beta-cell mass restoration[45].

Conversely, in type 2 diabetes, chronic metabolic stress, such as hyperglycemia and lipotoxicity, contributes to beta-cell dysfunction and increased apoptosis[46,47]. Although beta cells initially attempt to compensate by proliferating, the regenerative capacity diminishes over time, leading to progressive beta-cell failure[48,49]. Furthermore, beta-cell dedifferentiation, where beta cells lose their differentiated phenotype and insulin-secretory capacity, and/or trans-differentiation where beta cells differentiate into other islet hormone-producing cells are other contributing factors in type 2 diabetes[50,51]. This process further impairs insulin secretion and exacerbates hyperglycemia[52].

Beta cells are highly active in insulin synthesis, making them particularly susceptible to ER stress. Prolonged ER stress can lead to beta-cell apoptosis, contributing to both type 1 and type 2 diabetes[53,54]. Additionally, chronic hyper-glycemia can result in the overproduction of reactive oxygen species, leading to oxidative stress. This oxidative damage can impair beta-cell function and induce apoptosis[55]. Inflammatory pathways also play a significant role in beta-cell dysfunction. In type 2 diabetes, low-grade chronic inflammation can contribute to insulin resistance and beta-cell failure[56].

In type 3 diabetes, the beta-cell dysfunction extends beyond the pancreas. It involves insulin resistance within the brain, leading to cognitive decline and neurodegeneration[3]. Although the primary pathology is related to neuronal insulin resistance, beta-cell dysfunction and impaired insulin signaling in the brain also contribute to the disease process. This highlights the broader systemic implications of insulin resistance and the potential role of beta-cell dysfunction in neurodegenerative diseases[7]. While the exact mechanisms remain under investigation, there is evidence that similar pathways, such as oxidative stress, inflammation, and impaired insulin signaling, contribute to both beta-cell dysfunction and neurodegeneration in type 3 diabetes[57].

MiRNAs have emerged as important regulators of beta-cell function and mass, influencing key processes such as beta-cell proliferation, apoptosis, and insulin secretion. MiRNAs are small, non-coding RNAs that play crucial roles in the post-transcriptional regulation of gene expression. MiRNAs exert their effects by binding to the 3’ untranslated regions of target mRNAs, leading to either mRNA degradation or inhibition of translation[43]. Among the miRNAs studied, miR-375 is one of the most extensively researched in the context of beta-cell biology. It is highly expressed in pancreatic beta cells and has been shown to regulate insulin secretion and beta-cell proliferation. Overexpression of miR-375 can lead to beta-cell apoptosis by downregulating anti-apoptotic genes such as B-cell lymphoma 2, while its inhibition has been found to promote beta-cell proliferation, indicating its potential as a therapeutic target for diabetes[43,58]. Other miRNAs, such as miR-7, miR-9, and miR-124a, have also been implicated in regulating beta-cell function[59]. For example, miR-7 has negatively regulated insulin secretion by targeting key genes involved in the insulin signaling pathway, such as paired box 6 and mTOR[60]. Dysregulation of miR-7 expression has been associated with impaired beta-cell function in type 2 diabetes[61]. Similarly, miR-9 has been linked to the modulation of glucose-stimulated insulin secretion and beta-cell proliferation, acting through pathways involving one cut homeobox 2 and sirtuin 1[62].

MiRNAs are also implicated in beta-cell dedifferentiation and transdifferentiation, which are particularly relevant in the context of type 2 diabetes. For instance, alterations in miRNA expression profiles have been associated with the loss of beta-cell identity and the conversion of beta cells into other endocrine cell types, contributing to the progressive decline in beta-cell function observed in diabetes[51]. Given their regulatory role in beta-cell biology, miRNAs represent promising therapeutic targets for diabetes treatment. Modulating the expression of specific miRNAs could potentially restore beta-cell function, enhance insulin secretion, and prevent beta-cell apoptosis, offering new avenues for diabetes management. However, further research is needed to fully understand the complex interactions between miRNAs and their target genes in the context of beta-cell dysfunction and to develop safe and effective miRNA-based therapies[59]. Additionally, the immune system’s interaction with beta cells is also crucial, particularly in type 1 diabetes, where immune cells specifically target and destroy beta cells. Understanding the mechanisms of this immune-mediated attack is essential for developing interventions to protect and restore beta-cell mass[9,63].

Beta-cell communication within islets and the overall islet architecture play vital roles in synchronized insulin secretion[64]. Gap junctions and paracrine signaling within the islets ensure coordinated insulin release, highlighting the importance of maintaining islet integrity for optimal beta-cell function[65]. Understanding the physiological basis of beta-cell function has paved the way for innovative therapeutic strategies. Regenerative approaches aim to restore or replace beta-cell mass and function. This includes the use of stem cells to generate insulin-producing cells, gene editing techniques to enhance beta-cell resilience and function, and small molecules to promote beta-cell proliferation and survival[10,12,14,66]. Recent studies have highlighted the potential of reprogramming non-beta cells within the pancreas into functional beta cells. For instance, alpha cells and exocrine cells have been experimentally converted into insulin-producing cells, offering a potential endogenous source for beta-cell regeneration[67,68]. These advances underscore the importance of a detailed understanding of beta-cell physiology in developing effective treatments for diabetes.

RECENT SCIENTIFIC ADVANCEMENTS IN BETA-CELL REGENERATION

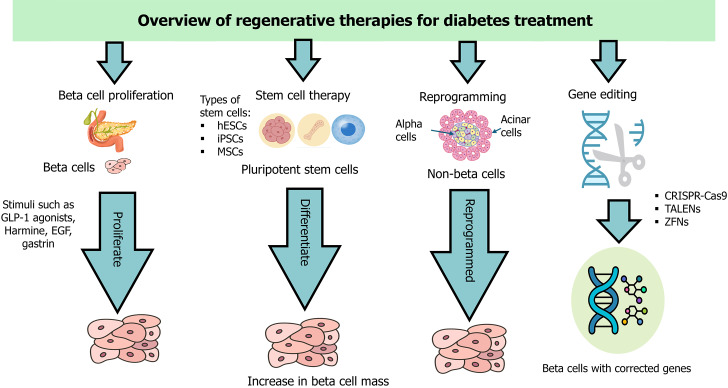

Advancements in beta-cell regeneration hold significant promise for transforming the treatment of diabetes. These approaches aim to restore the population of insulin-producing beta cells, which are diminished or dysfunctional in diabetic patients. Cutting-edge research has focused on three primary strategies: Stem cell therapy, gene editing technologies, and the identification of novel regenerative molecules. Each of these strategies offers unique pathways to enhance beta-cell mass and function, potentially revolutionizing diabetes management and offering new hope for patients[69]. Figure 3 provides a visual summary of these strategies, highlighting their mechanisms in the context of beta-cell regeneration for diabetes treatment.

Figure 3.

Overview of regenerative therapies for diabetes treatment. Cas9: CRISPR-associated protein 9; CRISPR: Clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats; EGF: Epidermal growth factor; hESCs: Human embryonic stem cells; GLP-1: Glucagon-like peptide-1; iPSCs: Induced pluripotent stem cells; MSCs: Mesenchymal stem cells; TALENs: Transcription activator-like effector nucleases; ZFNs: Zinc finger nucleases.

Stem cell therapy

Stem cell therapy represents a promising frontier in the quest for effective diabetes treatments, particularly for regenerating pancreatic beta cells. Various types of stem cells have been explored for this purpose, including mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), human embryonic SCs (hESCs), and induced pluripotent SCs (iPSCs). These cells have the potential to differentiate into insulin-producing beta cells, offering a potential solution for restoring endogenous insulin production in diabetic patients[70,71].

MSCs: MSCs can be derived from multiple sources, including bone marrow, adipose tissue, umbilical cord blood, and dental pulp[72]. They are known for their immunomodulatory properties and ability to differentiate into various cell types, including beta cells[73]. MSCs also secrete growth factors that support beta-cell survival and function. These characteristics make MSCs a versatile and promising option for cell-based therapies aimed at diabetes treatment[74-76].

hESCs: hESCs, derived from the inner cell mass of blastocysts, have the potential to differentiate into any cell type, including beta cells[77]. Recent advances have focused on deriving functional beta cells from hESCs through carefully controlled culture conditions and the introduction of specific growth factors and signaling molecules. These protocols mimic the natural developmental pathways of pancreatic cells, ensuring that the derived beta cells exhibit characteristics similar to native beta cells, such as glucose-stimulated insulin secretion[10,78,79]. The differentiation process typically requires several weeks to months, and the exact duration can vary across different species and experimental conditions[70,71,80].

iPSCs: iPSCs are generated by reprogramming adult somatic cells to a pluripotent state, giving them the ability to differentiate into various cell types, including beta cells[81]. iPSCs offer the advantage of being derived from the patient’s own cells, potentially reducing the risk of immune rejection. However, there are ongoing challenges related to the efficiency and consistency of iPSCs in differentiating into fully functional beta cells. Conflicting results in the literature highlight the need for further comparative studies to determine the most effective source of stem cells for beta-cell regeneration[82,83].

Stem cells can be transplanted into various sites within the body, to regenerate beta cells and restore insulin production. Common transplantation sites include the liver, where cells can integrate into the existing vasculature and receive appropriate signals for insulin secretion, and the subcutaneous space, where encapsulated stem cells can be protected from immune attack while providing systemic insulin release[76,84,85]. Most stem cell research related to beta-cell regeneration is currently in the preclinical stage, involving animal models. These studies have shown significant improvements in glucose regulation and reductions in the need for exogenous insulin upon transplantation of stem cell-derived beta cells. However, the translation to human clinical trials is still in its early stages, with ongoing trials assessing the safety and efficacy of these therapies in humans[71,86,87]. Several clinical trials have been registered on ClinicalTrials.gov over the past decade, focusing on both type 1 and type 2 diabetes. These trials are being conducted in various locations, including the United States, Canada, Europe, China, and other parts of Asia. Notable trials include the VC-01 and VC-02 trials by ViaCyte, which involve subcutaneous transplantation of hESC-derived pancreatic progenitor cells encapsulated in devices designed to protect from immune rejection[75,88].

Despite the promising advancements, several challenges remain in stem cell-based therapies. These include ensuring the long-term survival and functionality of transplanted beta cells, preventing immune rejection, and avoiding potential complications such as tumorigenesis. The risk of incomplete differentiation leading to undifferentiated cells that could form tumors, and achieving consistent glucose responsiveness in derived beta cells, are significant concerns. Strategies to address these issues involve encapsulating beta cells in biocompatible materials to protect them from immune attack and genetically modifying stem cells to reduce their immunogenicity[89,90]. In summary, stem cell therapy for beta-cell regeneration holds substantial promise but also faces numerous challenges. Ensuring the consistent and safe differentiation of stem cells into functional beta cells, addressing immune rejection, and mitigating the risk of complications are critical areas that require further research.

Gene editing technologies

Gene editing technologies, particularly CRISPR-Cas9, have revolutionized genetic engineering and opened new avenues for beta-cell regeneration in diabetes treatment. These technologies enable precise genome modifications, allowing researchers to correct genetic defects, enhance cellular functions, and explore gene functions. Various gene editing tools have been developed and applied to beta-cell regeneration with varying degrees of success[91].

CRISPR-Cas9: CRISPR-Cas9 is the most widely known and utilized gene editing tool due to its simplicity, efficiency, and versatility[92,93]. It uses a guide RNA to target specific DNA sequences and the Cas9 nuclease to create double-strand breaks. These breaks are repaired by the cell’s natural repair processes, allowing for targeted gene modifications[94]. One promising application of CRISPR-Cas9 in beta-cell regeneration is correcting mutations associated with monogenic forms of diabetes, such as maturity-onset diabetes of the young[95]. By targeting specific mutations in beta-cell genes, CRISPR-Cas9 can restore normal function and improve insulin secretion. Additionally, this technology has been used to knock out genes that inhibit beta-cell proliferation, thereby enhancing the regenerative capacity of these cells[91,96].

Further advancements involve modifying beta cells to express molecules that confer resistance to apoptosis or immune-mediated destruction. Such as modifying beta cells to overexpress anti-apoptotic genes can enhance their survival under stress conditions, improving beta-cell transplantation outcomes[34]. However, a recent study demonstrated the successful application of CRISPR-Cas9 in primary human islets, efficiently targeting both protein-coding exons and non-coding regulatory elements, this approach led to the acute loss of key beta-cell regulators such as PDX1 and potassium inwardly rectifying channel, subfamily J, member 11 (KIR6.2), significantly impairing beta-cell function. While promising, translating these findings to clinical applications requires addressing off-target effects, delivery methods, and ensuring long-term safety and efficacy[96].

Zinc finger nucleases: Zinc finger nucleases (ZFNs) are engineered proteins that bind to specific DNA sequences and induce double-strand breaks. They were among the first gene editing tools developed and have been used in various research and therapeutic contexts. ZFNs have targeted beta-cell genes, but their design is complex and less flexible compared to CRISPR-Cas9, limiting their widespread adoption[97,98]. Despite these limitations, ZFNs have shown potential in enhancing beta-cell function by targeting genes involved in insulin production and secretion[97].

Transcription activator-like effector nucleases: Transcription activator-like effector nucleases are engineered proteins that function similarly to ZFNs but offer higher specificity and fewer off-target effects[99]. They bind to specific DNA sequences and induce double-strand breaks, facilitating targeted gene modifications. Transcription activator-like effector nucleases have shown promise in enhancing beta-cell function by targeting genes critical for beta-cell survival and insulin secretion. However, their construction is more challenging and time-consuming compared to CRISPR-Cas9[100].

CRISPR-Cpf1 (also known as CRISPR-Cas12a): Cpf1 is another CRISPR-associated protein with unique properties compared to Cas9. It recognizes different protospacer adjacent motif sequences and creates staggered cuts in DNA, which can be advantageous for certain types of gene editing. Cpf1 also processes its own guide RNAs, simplifying the CRISPR system’s design and application for beta-cell gene editing. This tool has shown promise in editing beta-cell genes, offering an alternative to Cas9 with potentially different advantages and limitations[101].

Prime editing: Prime editing is a newer gene editing technology that uses a modified Cas9 protein fused to a reverse transcriptase. This system allows for precise DNA modifications without inducing double-strand breaks, enabling targeted insertions, deletions, and base substitutions with high accuracy and fewer off-target effects. Prime editing holds promise for correcting beta-cell gene mutations and enhancing beta-cell function[102,103].

Base editing: Base editing allows the direct conversion of one DNA base into another without causing double-strand breaks. This method uses a modified Cas9 protein fused to a deaminase enzyme to achieve targeted base changes, making it particularly useful for correcting point mutations in beta-cell genes. Base editing has shown potential in correcting genetic mutations that impair beta-cell function[102]. Gene editing holds significant promise but remains largely experimental, with most research in animal models. While studies demonstrate the feasibility of correcting genetic defects and enhancing beta-cell function, translating these findings to human trials is challenging. Ensuring safety and precision is critical due to potential off-target effects, which could lead to tumorigenesis or immune reactions[104,105]. Several preclinical studies show promising results in improving beta-cell function and survival through gene editing. However, clinical trials are needed to validate these findings and assess long-term safety and efficacy. Currently, a few early-phase trials in the United States, China, and Europe investigate CRISPR-Cas9 for various genetic disorders, with limited focus on diabetes or beta-cell regeneration[106-108]. Challenges in gene editing include achieving high efficiency and specificity in targeting beta-cell genes, avoiding off-target effects, and ensuring the edited cells can be safely and effectively integrated into the patient’s pancreas. Ethical considerations surrounding the use of gene editing, particularly in human embryos or germline cells, must be carefully addressed to gain public trust and regulatory approval[105,109].

Gene editing technologies offer a more targeted approach to correcting genetic defects and enhancing beta-cell function compared to stem cell therapy, which focuses on generating new beta cells from pluripotent or multipotent cells. Both approaches face challenges related to safety, efficacy, and immune rejection, but gene editing holds the potential for permanent correction of genetic defects, providing long-lasting solutions for diabetes management[110].

Novel regenerative molecules

The discovery of novel regenerative molecules that stimulate beta-cell proliferation and enhance its function is crucial for diabetes treatment. These molecules include small molecules, peptides, and growth factors targeting pathways involved in beta-cell development, maintenance, and regeneration. High-throughput screening has identified several small molecules that promote beta-cell proliferation by activating key signaling pathways such as wingless/integrated (Wnt) and β-catenin signaling (Wnt/β-catenin), Hedgehog, and Notch signaling. Notable examples include harmine, a dual-specificity tyrosine-(y)-phosphorylation regulated kinase 1a inhibitor, and γ-secretase inhibitors that modulate notch signaling to enhance beta-cell regeneration[111].

Peptides and growth factors also play significant roles in beta-cell regeneration. Betatrophin was initially reported to stimulate beta-cell proliferation, but subsequent studies have cast doubt on its efficacy, highlighting the complexities and controversies in this area of research[112]. By contrast, GLP-1 analogs, such as exenatide and liraglutide, are more established and known to promote beta-cell survival and proliferation by enhancing insulin secretion and reducing apoptosis[38]. Additionally, reprogramming molecules, which convert other pancreatic cell types, such as alpha cells, into beta-like cells, offer another innovative approach to increasing beta-cell mass. Factors such as PDX1, neurogenin 3, and MAFA induce such reprogramming, although the efficiency and stability of the reprogrammed cells remain areas of active investigation[113].

Recent studies have identified additional molecules, such as epidermal growth factor and gastrin, which synergistically promote beta-cell regeneration in preclinical models[114,115]. However, not all identified molecules are effective, and there is ongoing controversy regarding the reproducibility and translation of some findings from animal models to humans[116]. Extensive experimental and preclinical studies evaluate the efficacy and safety of these regenerative molecules. In vitro studies, using isolated pancreatic cells, assess the effects on beta-cell proliferation and function, measuring cell proliferation, insulin secretion, and gene expression. Numerous studies show promise in enhancing beta-cell regeneration. Preclinical in vivo studies with animal models, such as diabetic mice or rats, evaluate the therapeutic potential, studying effects on beta-cell mass, glucose homeostasis, and overall metabolic health. For instance, GLP-1 analogs have improved beta-cell function and reduced blood glucose levels in diabetic mice[117]. These studies also assess potential side effects and long-term safety, optimizing dosage, administration route, and treatment duration to ensure maximal efficacy with minimal adverse effects[117,118].

A recent systematic review on the combination therapy of SGLT2 inhibitors and GLP-1 receptor agonists demonstrated significant improvements in glycemic control, weight reduction, and blood pressure management without increasing the incidence of adverse events, including genital and urinary infections, in patients with T2DM or obesity. This evidence supports the therapeutic potential of these molecules in diabetes management and highlights their safety and efficacy profiles. Given the importance of enhancing beta-cell function and survival, the positive outcomes associated with GLP-1 receptor agonists make this combination therapy a relevant and promising strategy in the context of regenerative treatments for diabetes[119].

The administration of regenerative molecules varies based on their type and pharmacokinetic properties. Common routes include intravenous injection for peptides and growth factors, subcutaneous injection for molecules such as GLP-1 analogs, and oral administration for small molecules[119]. Localized delivery to the pancreas can enhance local effects and reduce systemic side effects. The duration for these molecules to show effects can range from days to weeks, depending on the specific molecule and model used[120].

Despite promising results, significant challenges and controversies exist with regenerative molecules. Reproducibility across studies and species is a major concern, and translating preclinical successes to clinical applications has proven difficult, with many molecules failing to show the same efficacy in human trials. Long-term safety and potential off-target effects remain critical areas of concern, requiring rigorous testing and validation to address these issues[116]. Table 2 summarizes the key distinctions between various regenerative approaches for diabetes treatment, highlighting their mechanisms of action, advantages, challenges, and examples.

Table 2.

Comparison of regenerative approaches for diabetes treatment

|

Regenerative approach

|

Mechanism of action

|

Advantages

|

Challenges

|

Examples

|

Ref.

|

| Beta-cell regeneration and novel regenerative molecules | Stimulates proliferation, enhances function, and supports survival of existing beta cells | Potential for restoring endogenous insulin production and enhancing beta-cell mass | Reproducibility, safety concerns, and challenges in achieving efficient beta-cell proliferation | GLP-1 analogs, EGF, gastrin, Harmine (DYRK1A inhibitor) | [111,114-116,119] |

| Stem cell therapy | Differentiates stem cells into beta-like cells | Can potentially replace lost beta cells | Ethical concerns, risk of tumorigenesis, and immune rejection | hESCs, iPSCs | [89,124,125] |

| Gene editing | Corrects genetic defects in beta cells | Precise genetic modifications | Off-target effects, ethical concerns | CRISPR-Cas9, TALENs, ZFNs | [116,121,123] |

| Reprogramming molecules | Converts other pancreatic cell types into beta-like cells | Increases beta-cell mass | Efficiency and stability of reprogrammed cells remain areas of investigation | PDX1, NGN3, MAFA | [113] |

CRISPR-Cas9: Clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats and CRISPR-associated protein 9; DYRK1A: Dual-specificity tyrosine-(Y)-phosphorylation regulated kinase 1A; EGF: Epidermal growth factor; GLP-1: Glucagon-like peptide 1; hESCs: Human embryonic stem cells; iPSCs: Induced pluripotent stem cells; MAFA: V-Maf musculoaponeurotic fibrosarcoma oncogene homolog A; NGN3: Neurogenin 3; PDX1: Pancreatic and duodenal homeobox 1; TALENs: Transcription activator-like effector nucleases; ZFNs: Zinc finger nucleases.

CHALLENGES IN TRANSLATING FINDINGS TO CLINICAL APPLICATIONS

Translating the promising results of regenerative molecule studies into clinical applications faces significant challenges that must be addressed to effectively treat diabetes.

Safety and long-term efficacy

Ensuring the safety and long-term efficacy of regenerative therapies is paramount. While preclinical studies show promise, translating these results to humans has been difficult. Many regenerative molecules that are effective in animal models fail in human trials[121-123]. Potential off-target effects pose risks, such as tumorigenesis or immune reactions. Long-term studies are needed to evaluate the sustained benefits and risks of these therapies, ensuring beta-cell regeneration does not introduce new health issues[124].

Ethical concerns

The ethical implications of regenerative approaches, particularly those involving stem cells and gene editing, must be carefully considered.

Stem cell research ethics: The use of hESCs remains one of the most contentious ethical issues in regenerative medicine. The primary ethical dilemma arises from the process of deriving hESCs, which involves the destruction of human embryos. This has sparked intense moral debates regarding the status of the embryo and the ethical acceptability of such research[125]. In the United States, the Dickey-Wicker Amendment prohibits federal funding for research that involves the creation or destruction of human embryos, reflecting the ongoing ethical and legal struggle to balance scientific progress with respect for human life[125]. While this regulation aims to protect ethical standards, it also constrains the potential of hESC research to advance regenerative therapies for conditions like diabetes.

Although iPSCs offer an alternative as they are derived from adult cells and do not require the destruction of embryos, they are not entirely free from ethical challenges. Concerns about genetic manipulation during the reprogramming process, potential genetic instability, and the risk of tumorigenesis highlight the need for careful ethical scrutiny and long-term safety evaluations. The use of iPSCs may bypass the ethical issues associated with hESCs, but it introduces new questions about the consequences of genetic alterations and the broader implications of manipulating human cells at a fundamental level[124,126,127].

Gene editing ethics and medicolegal implications: Gene editing technologies also raise significant ethical and medicolegal concerns. The possibility of germline editing, where genetic modifications could be passed down to future generations, presents profound ethical dilemmas[128]. The case of CRISPR-edited embryos in China, which led to international outcry, exemplifies the risks and ethical questions surrounding gene editing[129]. This case underscored the urgent need for global ethical standards and regulatory oversight to govern the use of such powerful technologies.

Medicolegal concerns are equally pressing. Ensuring that patients provide fully informed consent is critical, especially when the long-term risks of gene editing are not fully understood[130]. There is also the issue of liability - who bears responsibility if unforeseen complications arise from gene-editing interventions? The literature emphasizes the necessity of establishing clear legal frameworks that not only protect patient rights but also ensure that researchers and clinicians are held accountable for the outcomes of these cutting-edge treatments[131].

Complexity of beta-cell differentiation and integration

Differentiating stem cells into functional beta cells and ensuring their proper integration into the patient’s existing cellular architecture remains highly complex. Achieving the precise conditions for beta-cell differentiation in vitro does not guarantee success in vivo. Newly formed beta cells must produce insulin effectively, respond to glucose levels, and integrate seamlessly with the host’s immune system to avoid rejection. Additionally, the pancreatic microenvironment and interactions between various cell types add layers of complexity that are challenging to replicate and control[132].

INTERDISCIPLINARY COLLABORATION AND COMPREHENSIVE CARE STRATEGIES

Effective diabetes management, particularly when incorporating regenerative therapies, necessitates a coordinated, interdisciplinary approach involving various healthcare professionals[133]. For example, a patient with type 2 diabetes struggling to maintain glycemic control may benefit from a care team comprising an endocrinologist, a dietitian, a diabetes educator, and a psychologist. This collaborative approach addresses the patient’s medical, nutritional, and psychological needs, leading to improved health outcomes[134].

In a more advanced scenario, a patient with type 1 diabetes considering beta-cell regeneration therapy would work with an interdisciplinary team including an endocrinologist, a transplant surgeon, and a genetic counselor. The team discusses potential risks and benefits, with the genetic counselor providing insights into how the patient’s genetic profile might influence the therapy’s success. The active involvement of the patient and their family ensures a patient-centered, fully informed care strategy[133]. The advancement of regenerative medicine for diabetes demands integrating the expertise of various specialists to address the complexities of beta-cell regeneration. Collaborative research networks and cross-disciplinary training are essential for accelerating discovery and enhancing innovation in diabetes care[135].

Patient-centered approaches are essential for aligning diabetes therapies with individual needs, involving patients in research, and developing personalized treatment plans[136]. Integrating regenerative therapies into comprehensive care strategies, which include lifestyle interventions, continuous monitoring, and support systems, enhances effectiveness and ensures holistic patient management[137]. Personalized treatment plans, informed by genetic profiles and disease progression, optimize efficacy and minimize adverse effects[138,139]. Educating patients about their condition and emphasizing treatment adherence empowers them to actively manage their condition[140,141]. Additionally, utilizing digital health tools and data analytics enhances diabetes management, leading to improved health outcomes and quality of life[142,143].

CONCLUSION

Integrating regenerative therapies into diabetes treatment represents a promising frontier in medical science. Beta-cell regeneration, in particular, offers the potential to restore endogenous insulin production and achieve long-term glycemic control. By fostering interdisciplinary collaboration and adopting patient-centered approaches, scientific advancements can be effectively translated into practical, safe, and personalized treatments. Comprehensive care strategies that include personalized treatment plans, multidisciplinary support, lifestyle interventions, patient education, and technological integration are essential for maximizing the benefits of regenerative therapies. Addressing the challenges of safety, long-term efficacy, ethical concerns, and the complexity of beta-cell differentiation and integration is crucial. Through these efforts, the aim is to improve health outcomes and enhance the quality of life for individuals with diabetes.

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest statement: The author has no conflicts of interest to declare.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Endocrinology and metabolism

Country of origin: Malaysia

Peer-review report’s classification

Scientific Quality: Grade B

Novelty: Grade B

Creativity or Innovation: Grade B

Scientific Significance: Grade B

P-Reviewer: Aydin S S-Editor: Wang JJ L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Chen YX

References

- 1.DiMeglio LA, Evans-Molina C, Oram RA. Type 1 diabetes. Lancet. 2018;391:2449–2462. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31320-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Skyler JS, Bakris GL, Bonifacio E, Darsow T, Eckel RH, Groop L, Groop PH, Handelsman Y, Insel RA, Mathieu C, McElvaine AT, Palmer JP, Pugliese A, Schatz DA, Sosenko JM, Wilding JP, Ratner RE. Differentiation of Diabetes by Pathophysiology, Natural History, and Prognosis. Diabetes. 2017;66:241–255. doi: 10.2337/db16-0806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peng Y, Yao SY, Chen Q, Jin H, Du MQ, Xue YH, Liu S. True or false? Alzheimer's disease is type 3 diabetes: Evidences from bench to bedside. Ageing Res Rev. 2024;99:102383. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2024.102383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bourgeois S, Coenen S, Degroote L, Willems L, Van Mulders A, Pierreux J, Heremans Y, De Leu N, Staels W. Harnessing beta cell regeneration biology for diabetes therapy. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2024 doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2024.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu T, Zou X, Ruze R, Xu Q. Bariatric Surgery: Targeting pancreatic β cells to treat type II diabetes. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2023;14:1031610. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2023.1031610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Soldovieri L, Di Giuseppe G, Ciccarelli G, Quero G, Cinti F, Brunetti M, Nista EC, Gasbarrini A, Alfieri S, Pontecorvi A, Giaccari A, Mezza T. An update on pancreatic regeneration mechanisms: Searching for paths to a cure for type 2 diabetes. Mol Metab. 2023;74:101754. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2023.101754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dutta BJ, Singh S, Seksaria S, Das Gupta G, Singh A. Inside the diabetic brain: Insulin resistance and molecular mechanism associated with cognitive impairment and its possible therapeutic strategies. Pharmacol Res. 2022;182:106358. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2022.106358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang X, Gao M, Wang Y, Zhang Y. The progress of pluripotent stem cell-derived pancreatic β-cells regeneration for diabetic therapy. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2022;13:927324. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2022.927324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhao Y, Jiang Z, Zhao T, Ye M, Hu C, Yin Z, Li H, Zhang Y, Diao Y, Li Y, Chen Y, Sun X, Fisk MB, Skidgel R, Holterman M, Prabhakar B, Mazzone T. Reversal of type 1 diabetes via islet β cell regeneration following immune modulation by cord blood-derived multipotent stem cells. BMC Med. 2012;10:3. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-10-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dadheech N, James Shapiro AM. Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells in the Curative Treatment of Diabetes and Potential Impediments Ahead. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2019;1144:25–35. doi: 10.1007/5584_2018_305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.El Nahas R, Al-Aghbar MA, Herrero L, van Panhuys N, Espino-Guarch M. Applications of Genome-Editing Technologies for Type 1 Diabetes. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;25 doi: 10.3390/ijms25010344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gerace D, Martiniello-Wilks R, Nassif NT, Lal S, Steptoe R, Simpson AM. CRISPR-targeted genome editing of mesenchymal stem cell-derived therapies for type 1 diabetes: a path to clinical success? Stem Cell Res Ther. 2017;8:62. doi: 10.1186/s13287-017-0511-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wal P, Aziz N, Prajapati H, Soni S, Wal A. Current Landscape of Various Techniques and Methods of Gene Therapy through CRISPR Cas9 along with its Pharmacological and Interventional Therapies in the Treatment of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Curr Diabetes Rev. 2024;20:e201023222414. doi: 10.2174/0115733998263079231011073803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McCarty SM, Clasby MC, Sexton JZ. High-Throughput Methods for the Discovery of Small Molecule Modulators of Pancreatic Beta-Cell Function and Regeneration. Assay Drug Dev Technol. 2024;22:148–159. doi: 10.1089/adt.2023.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goode RA, Hum JM, Kalwat MA. Therapeutic Strategies Targeting Pancreatic Islet β-Cell Proliferation, Regeneration, and Replacement. Endocrinology. 2022;164 doi: 10.1210/endocr/bqac193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Townsend SE, Gannon M. Extracellular Matrix-Associated Factors Play Critical Roles in Regulating Pancreatic β-Cell Proliferation and Survival. Endocrinology. 2019;160:1885–1894. doi: 10.1210/en.2019-00206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moradi S, Mahdizadeh H, Šarić T, Kim J, Harati J, Shahsavarani H, Greber B, Moore JB 4th. Research and therapy with induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs): social, legal, and ethical considerations. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2019;10:341. doi: 10.1186/s13287-019-1455-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lo B, Parham L. Ethical issues in stem cell research. Endocr Rev. 2009;30:204–213. doi: 10.1210/er.2008-0031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Losada-Barragán M. Physiological effects of nutrients on insulin release by pancreatic beta cells. Mol Cell Biochem. 2021;476:3127–3139. doi: 10.1007/s11010-021-04146-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goren HJ. Role of insulin in glucose-stimulated insulin secretion in beta cells. Curr Diabetes Rev. 2005;1:309–330. doi: 10.2174/157339905774574301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Drucker DJ. Mechanisms of Action and Therapeutic Application of Glucagon-like Peptide-1. Cell Metab. 2018;27:740–756. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2018.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moullé VS. Autonomic control of pancreatic beta cells: What is known on the regulation of insulin secretion and beta-cell proliferation in rodents and humans. Peptides. 2022;148:170709. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2021.170709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Damsteegt EL, Hassan Z, Hewawasam NV, Sarnsamak K, Jones PM, Hauge-Evans AC. A Novel Role for Somatostatin in the Survival of Mouse Pancreatic Beta Cells. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2019;52:486–502. doi: 10.33594/000000035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tudurí E, Marroquí L, Soriano S, Ropero AB, Batista TM, Piquer S, López-Boado MA, Carneiro EM, Gomis R, Nadal A, Quesada I. Inhibitory effects of leptin on pancreatic alpha-cell function. Diabetes. 2009;58:1616–1624. doi: 10.2337/db08-1787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Manesso E, Toffolo GM, Saisho Y, Butler AE, Matveyenko AV, Cobelli C, Butler PC. Dynamics of beta-cell turnover: evidence for beta-cell turnover and regeneration from sources of beta-cells other than beta-cell replication in the HIP rat. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2009;297:E323–E330. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00284.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Teta M, Long SY, Wartschow LM, Rankin MM, Kushner JA. Very slow turnover of beta-cells in aged adult mice. Diabetes. 2005;54:2557–2567. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.9.2557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Boland BB, Rhodes CJ, Grimsby JS. The dynamic plasticity of insulin production in β-cells. Mol Metab. 2017;6:958–973. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2017.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fatrai S, Elghazi L, Balcazar N, Cras-Méneur C, Krits I, Kiyokawa H, Bernal-Mizrachi E. Akt induces beta-cell proliferation by regulating cyclin D1, cyclin D2, and p21 levels and cyclin-dependent kinase-4 activity. Diabetes. 2006;55:318–325. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.55.02.06.db05-0757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Montemurro C, Vadrevu S, Gurlo T, Butler AE, Vongbunyong KE, Petcherski A, Shirihai OS, Satin LS, Braas D, Butler PC, Tudzarova S. Cell cycle-related metabolism and mitochondrial dynamics in a replication-competent pancreatic beta-cell line. Cell Cycle. 2017;16:2086–2099. doi: 10.1080/15384101.2017.1361069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Asahara SI, Inoue H, Watanabe H, Kido Y. Roles of mTOR in the Regulation of Pancreatic β-Cell Mass and Insulin Secretion. Biomolecules. 2022;12 doi: 10.3390/biom12050614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Blandino-Rosano M, Barbaresso R, Jimenez-Palomares M, Bozadjieva N, Werneck-de-Castro JP, Hatanaka M, Mirmira RG, Sonenberg N, Liu M, Rüegg MA, Hall MN, Bernal-Mizrachi E. Loss of mTORC1 signalling impairs β-cell homeostasis and insulin processing. Nat Commun. 2017;8:16014. doi: 10.1038/ncomms16014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Alvarez-Perez JC, Rosa TC, Casinelli GP, Valle SR, Lakshmipathi J, Rosselot C, Rausell-Palamos F, Vasavada RC, García-Ocaña A. Hepatocyte growth factor ameliorates hyperglycemia and corrects β-cell mass in IRS2-deficient mice. Mol Endocrinol. 2014;28:2038–2048. doi: 10.1210/me.2014-1207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Agudo J, Ayuso E, Jimenez V, Salavert A, Casellas A, Tafuro S, Haurigot V, Ruberte J, Segovia JC, Bueren J, Bosch F. IGF-I mediates regeneration of endocrine pancreas by increasing beta cell replication through cell cycle protein modulation in mice. Diabetologia. 2008;51:1862–1872. doi: 10.1007/s00125-008-1087-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Camaya I, Donnelly S, O'Brien B. Targeting the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway in pancreatic β-cells to enhance their survival and function: An emerging therapeutic strategy for type 1 diabetes. J Diabetes. 2022;14:247–260. doi: 10.1111/1753-0407.13252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Melloul D. Transcription factors in islet development and physiology: role of PDX-1 in beta-cell function. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004;1014:28–37. doi: 10.1196/annals.1294.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schaffer AE, Taylor BL, Benthuysen JR, Liu J, Thorel F, Yuan W, Jiao Y, Kaestner KH, Herrera PL, Magnuson MA, May CL, Sander M. Nkx6.1 controls a gene regulatory network required for establishing and maintaining pancreatic Beta cell identity. PLoS Genet. 2013;9:e1003274. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang H, Brun T, Kataoka K, Sharma AJ, Wollheim CB. MAFA controls genes implicated in insulin biosynthesis and secretion. Diabetologia. 2007;50:348–358. doi: 10.1007/s00125-006-0490-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Costes S, Bertrand G, Ravier MA. Mechanisms of Beta-Cell Apoptosis in Type 2 Diabetes-Prone Situations and Potential Protection by GLP-1-Based Therapies. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22 doi: 10.3390/ijms22105303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nguyen TT, Wei S, Nguyen TH, Jo Y, Zhang Y, Park W, Gariani K, Oh CM, Kim HH, Ha KT, Park KS, Park R, Lee IK, Shong M, Houtkooper RH, Ryu D. Mitochondria-associated programmed cell death as a therapeutic target for age-related disease. Exp Mol Med. 2023;55:1595–1619. doi: 10.1038/s12276-023-01046-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ebato C, Uchida T, Arakawa M, Komatsu M, Ueno T, Komiya K, Azuma K, Hirose T, Tanaka K, Kominami E, Kawamori R, Fujitani Y, Watada H. Autophagy is important in islet homeostasis and compensatory increase of beta cell mass in response to high-fat diet. Cell Metab. 2008;8:325–332. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2008.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bugliani M, Mossuto S, Grano F, Suleiman M, Marselli L, Boggi U, De Simone P, Eizirik DL, Cnop M, Marchetti P, De Tata V. Modulation of Autophagy Influences the Function and Survival of Human Pancreatic Beta Cells Under Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress Conditions and in Type 2 Diabetes. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2019;10:52. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2019.00052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhu Y, Sun Y, Zhou Y, Zhang Y, Zhang T, Li Y, You W, Chang X, Yuan L, Han X. MicroRNA-24 promotes pancreatic beta cells toward dedifferentiation to avoid endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced apoptosis. J Mol Cell Biol. 2019;11:747–760. doi: 10.1093/jmcb/mjz004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sun X, Wang L, Obayomi SMB, Wei Z. Epigenetic Regulation of β Cell Identity and Dysfunction. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2021;12:725131. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2021.725131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Størling J, Pociot F. Type 1 Diabetes Candidate Genes Linked to Pancreatic Islet Cell Inflammation and Beta-Cell Apoptosis. Genes (Basel) 2017;8 doi: 10.3390/genes8020072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Saunders D, Powers AC. Replicative capacity of β-cells and type 1 diabetes. J Autoimmun. 2016;71:59–68. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2016.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vela-Guajardo JE, Garza-González S, García N. Glucolipotoxicity-induced Oxidative Stress is Related to Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Apoptosis of Pancreatic β-cell. Curr Diabetes Rev. 2021;17:e031120187541. doi: 10.2174/1573399816666201103142102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Benito-Vicente A, Jebari-Benslaiman S, Galicia-Garcia U, Larrea-Sebal A, Uribe KB, Martin C. Molecular mechanisms of lipotoxicity-induced pancreatic β-cell dysfunction. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol. 2021;359:357–402. doi: 10.1016/bs.ircmb.2021.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Marchetti P, Lupi R, Del Guerra S, Bugliani M, Marselli L, Boggi U. The beta-cell in human type 2 diabetes. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2010;654:501–514. doi: 10.1007/978-90-481-3271-3_22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Eizirik DL, Pasquali L, Cnop M. Pancreatic β-cells in type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus: different pathways to failure. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2020;16:349–362. doi: 10.1038/s41574-020-0355-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Son J, Accili D. Reversing pancreatic β-cell dedifferentiation in the treatment of type 2 diabetes. Exp Mol Med. 2023;55:1652–1658. doi: 10.1038/s12276-023-01043-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Moin ASM, Butler AE. Alterations in Beta Cell Identity in Type 1 and Type 2 Diabetes. Curr Diab Rep. 2019;19:83. doi: 10.1007/s11892-019-1194-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cinti F, Bouchi R, Kim-Muller JY, Ohmura Y, Sandoval PR, Masini M, Marselli L, Suleiman M, Ratner LE, Marchetti P, Accili D. Evidence of β-Cell Dedifferentiation in Human Type 2 Diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2016;101:1044–1054. doi: 10.1210/jc.2015-2860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Laybutt DR, Preston AM, Akerfeldt MC, Kench JG, Busch AK, Biankin AV, Biden TJ. Endoplasmic reticulum stress contributes to beta cell apoptosis in type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2007;50:752–763. doi: 10.1007/s00125-006-0590-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Brozzi F, Eizirik DL. ER stress and the decline and fall of pancreatic beta cells in type 1 diabetes. Ups J Med Sci. 2016;121:133–139. doi: 10.3109/03009734.2015.1135217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Eguchi N, Vaziri ND, Dafoe DC, Ichii H. The Role of Oxidative Stress in Pancreatic β Cell Dysfunction in Diabetes. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22 doi: 10.3390/ijms22041509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zatterale F, Longo M, Naderi J, Raciti GA, Desiderio A, Miele C, Beguinot F. Chronic Adipose Tissue Inflammation Linking Obesity to Insulin Resistance and Type 2 Diabetes. Front Physiol. 2019;10:1607. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2019.01607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Abdalla MMI. Insulin resistance as the molecular link between diabetes and Alzheimer's disease. World J Diabetes. 2024;15:1430–1447. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v15.i7.1430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Guo C, Sun YQ, Li Q, Zhang JC. MiR-7, miR-9 and miR-375 contribute to effect of Exendin-4 on pancreatic β-cells in high-fat-diet-fed mice. Clin Invest Med. 2018;41:E16–E24. doi: 10.25011/cim.v41i1.29459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kaur P, Kotru S, Singh S, Behera BS, Munshi A. Role of miRNAs in the pathogenesis of T2DM, insulin secretion, insulin resistance, and β cell dysfunction: the story so far. J Physiol Biochem. 2020;76:485–502. doi: 10.1007/s13105-020-00760-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wang Y, Liu J, Liu C, Naji A, Stoffers DA. MicroRNA-7 regulates the mTOR pathway and proliferation in adult pancreatic β-cells. Diabetes. 2013;62:887–895. doi: 10.2337/db12-0451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wan S, Wang J, Wang J, Wu J, Song J, Zhang CY, Zhang C, Wang C, Wang JJ. Increased serum miR-7 is a promising biomarker for type 2 diabetes mellitus and its microvascular complications. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2017;130:171–179. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2017.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hu D, Wang Y, Zhang H, Kong D. Identification of miR-9 as a negative factor of insulin secretion from beta cells. J Physiol Biochem. 2018;74:291–299. doi: 10.1007/s13105-018-0615-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Roep BO, Wheeler DCS, Peakman M. Antigen-based immune modulation therapy for type 1 diabetes: the era of precision medicine. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2019;7:65–74. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(18)30109-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Roscioni SS, Migliorini A, Gegg M, Lickert H. Impact of islet architecture on β-cell heterogeneity, plasticity and function. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2016;12:695–709. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2016.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Adams MT, Blum B. Determinants and dynamics of pancreatic islet architecture. Islets. 2022;14:82–100. doi: 10.1080/19382014.2022.2030649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rathwa N, Patel R, Palit SP, Parmar N, Rana S, Ansari MI, Ramachandran AV, Begum R. β-cell replenishment: Possible curative approaches for diabetes mellitus. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2020;30:1870–1881. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2020.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Spezani R, Reis-Barbosa PH, Mandarim-de-Lacerda CA. Update on the transdifferentiation of pancreatic cells into functional beta cells for treating diabetes. Life Sci. 2024;346:122645. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2024.122645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lu J, Zhou Q. In Vivo Reprogramming for Regenerating Insulin-Secreting Cells. In: Yilmazaer A. In Vivo Reprogramming for Regenerating Medicine. Stem Cell Biology and Regenerative Medicine. Cham: Hunmana Press, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Azad A, Altunbas HA, Manguoglu AE. From islet transplantation to beta-cell regeneration: an update on beta-cell-based therapeutic approaches in type 1 diabetes. Expert Rev Endocrinol Metab. 2024;19:217–227. doi: 10.1080/17446651.2024.2347263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hogrebe NJ, Maxwell KG, Augsornworawat P, Millman JR. Generation of insulin-producing pancreatic β cells from multiple human stem cell lines. Nat Protoc. 2021;16:4109–4143. doi: 10.1038/s41596-021-00560-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Song WJ, Shah R, Hussain MA. The use of animal models to study stem cell therapies for diabetes mellitus. ILAR J. 2009;51:74–81. doi: 10.1093/ilar.51.1.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Crisan M, Yap S, Casteilla L, Chen CW, Corselli M, Park TS, Andriolo G, Sun B, Zheng B, Zhang L, Norotte C, Teng PN, Traas J, Schugar R, Deasy BM, Badylak S, Buhring HJ, Giacobino JP, Lazzari L, Huard J, Péault B. A perivascular origin for mesenchymal stem cells in multiple human organs. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;3:301–313. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kerby A, Jones ES, Jones PM, King AJ. Co-transplantation of islets with mesenchymal stem cells in microcapsules demonstrates graft outcome can be improved in an isolated-graft model of islet transplantation in mice. Cytotherapy. 2013;15:192–200. doi: 10.1016/j.jcyt.2012.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Al-azzawi B, Mcguigan DH, Koivula FNM, Elttayef A, Dale TP, Yang Y, Kelly C, Forsyth NR. The Secretome of Mesenchymal Stem Cells Prevents Islet Beta Cell Apoptosis via an IL-10-Dependent Mechanism. Open Stem Cell J. 2020;6:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 75.de Klerk E, Hebrok M. Stem Cell-Based Clinical Trials for Diabetes Mellitus. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2021;12:631463. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2021.631463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Gan J, Wang Y, Zhou X. Stem cell transplantation for the treatment of patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus: A meta-analysis. Exp Ther Med. 2018;16:4479–4492. doi: 10.3892/etm.2018.6769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Thomson JA, Itskovitz-Eldor J, Shapiro SS, Waknitz MA, Swiergiel JJ, Marshall VS, Jones JM. Embryonic stem cell lines derived from human blastocysts. Science. 1998;282:1145–1147. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5391.1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Russ HA, Parent AV, Ringler JJ, Hennings TG, Nair GG, Shveygert M, Guo T, Puri S, Haataja L, Cirulli V, Blelloch R, Szot GL, Arvan P, Hebrok M. Controlled induction of human pancreatic progenitors produces functional beta-like cells in vitro. EMBO J. 2015;34:1759–1772. doi: 10.15252/embj.201591058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Shapiro AM, Lakey JR, Ryan EA, Korbutt GS, Toth E, Warnock GL, Kneteman NM, Rajotte RV. Islet transplantation in seven patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus using a glucocorticoid-free immunosuppressive regimen. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:230–238. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200007273430401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Rezania A, Bruin JE, Arora P, Rubin A, Batushansky I, Asadi A, O'Dwyer S, Quiskamp N, Mojibian M, Albrecht T, Yang YH, Johnson JD, Kieffer TJ. Reversal of diabetes with insulin-producing cells derived in vitro from human pluripotent stem cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2014;32:1121–1133. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Takahashi K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell. 2006;126:663–676. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Nair GG, Tzanakakis ES, Hebrok M. Emerging routes to the generation of functional β-cells for diabetes mellitus cell therapy. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2020;16:506–518. doi: 10.1038/s41574-020-0375-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Maxwell KG, Millman JR. Applications of iPSC-derived beta cells from patients with diabetes. Cell Rep Med. 2021;2:100238. doi: 10.1016/j.xcrm.2021.100238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Shapiro AJ, Thompson D, Donner TW, Bellin MD, Hsueh WA, Pettus JH, Wilensky JS, Daniels M, Wang RM, Kroon EJ, Brandon EP, D'amour K, Foyt H. Insulin Expression and Glucose-Responsive Circulating C-Peptide in Type 1 Diabetes Patients Implanted Subcutaneously with Pluripotent Stem Cell-Derived Pancreatic Endoderm Cells in a Macro-Device. Soc Sci Res Netw. 2019 [Google Scholar]

- 85.Delaune V, Berney T, Lacotte S, Toso C. Intraportal islet transplantation: the impact of the liver microenvironment. Transpl Int. 2017;30:227–238. doi: 10.1111/tri.12919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Jeon K, Lim H, Kim JH, Thuan NV, Park SH, Lim YM, Choi HY, Lee ER, Kim JH, Lee MS, Cho SG. Differentiation and transplantation of functional pancreatic beta cells generated from induced pluripotent stem cells derived from a type 1 diabetes mouse model. Stem Cells Dev. 2012;21:2642–2655. doi: 10.1089/scd.2011.0665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Hua XF, Wang YW, Tang YX, Yu SQ, Jin SH, Meng XM, Li HF, Liu FJ, Sun Q, Wang HY, Li JY. Pancreatic insulin-producing cells differentiated from human embryonic stem cells correct hyperglycemia in SCID/NOD mice, an animal model of diabetes. PLoS One. 2014;9:e102198. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0102198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Ng NHJ, Tan WX, Koh YX, Teo AKK. Human Islet Isolation and Distribution Efforts for Clinical and Basic Research. OBM Transplant. 2019;3:068. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Ghoneim MA, Gabr MM, El-Halawani SM, Refaie AF. Current status of stem cell therapy for type 1 diabetes: a critique and a prospective consideration. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2024;15:23. doi: 10.1186/s13287-024-03636-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Ochyra Ł, Łopuszyńska A. The use of stem cells in the treatment of diabetes mellitus and its complications - review. J Educ Health Sport. 2024;74:51736. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Balboa D, Prasad RB, Groop L, Otonkoski T. Genome editing of human pancreatic beta cell models: problems, possibilities and outlook. Diabetologia. 2019;62:1329–1336. doi: 10.1007/s00125-019-4908-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Ferreira P, Choupina AB. CRISPR/Cas9 a simple, inexpensive and effective technique for gene editing. Mol Biol Rep. 2022;49:7079–7086. doi: 10.1007/s11033-022-07442-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Lotfi M, Butler AE, Sukhorukov VN, Sahebkar A. Application of CRISPR-Cas9 technology in diabetes research. Diabet Med. 2024;41:e15240. doi: 10.1111/dme.15240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Dhanjal JK, Radhakrishnan N, Sundar D. CRISPcut: A novel tool for designing optimal sgRNAs for CRISPR/Cas9 based experiments in human cells. Genomics. 2019;111:560–566. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2018.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Maxwell KG, Augsornworawat P, Velazco-Cruz L, Kim MH, Asada R, Hogrebe NJ, Morikawa S, Urano F, Millman JR. Gene-edited human stem cell-derived β cells from a patient with monogenic diabetes reverse preexisting diabetes in mice. Sci Transl Med. 2020;12 doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aax9106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Bevacqua RJ, Dai X, Lam JY, Gu X, Friedlander MSH, Tellez K, Miguel-Escalada I, Bonàs-Guarch S, Atla G, Zhao W, Kim SH, Dominguez AA, Qi LS, Ferrer J, MacDonald PE, Kim SK. CRISPR-based genome editing in primary human pancreatic islet cells. Nat Commun. 2021;12:2397. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-22651-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Eksi YE, Sanlioglu AD, Akkaya B, Ozturk BE, Sanlioglu S. Genome engineering and disease modeling via programmable nucleases for insulin gene therapy; promises of CRISPR/Cas9 technology. World J Stem Cells. 2021;13:485–502. doi: 10.4252/wjsc.v13.i6.485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Mittelman D, Moye C, Morton J, Sykoudis K, Lin Y, Carroll D, Wilson JH. Zinc-finger directed double-strand breaks within CAG repeat tracts promote repeat instability in human cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:9607–9612. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0902420106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Mussolino C, Alzubi J, Fine EJ, Morbitzer R, Cradick TJ, Lahaye T, Bao G, Cathomen T. TALENs facilitate targeted genome editing in human cells with high specificity and low cytotoxicity. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:6762–6773. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Kues WA, Kumar D, Selokar NL, Talluri TR. Applications of Genome Editing Tools in Stem Cells Towards Regenerative Medicine: An Update. Curr Stem Cell Res Ther. 2022;17:267–279. doi: 10.2174/1574888X16666211124095527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Safari F, Zare K, Negahdaripour M, Barekati-Mowahed M, Ghasemi Y. CRISPR Cpf1 proteins: structure, function and implications for genome editing. Cell Biosci. 2019;9:36. doi: 10.1186/s13578-019-0298-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Saber Sichani A, Ranjbar M, Baneshi M, Torabi Zadeh F, Fallahi J. A Review on Advanced CRISPR-Based Genome-Editing Tools: Base Editing and Prime Editing. Mol Biotechnol. 2023;65:849–860. doi: 10.1007/s12033-022-00639-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Chen PJ, Liu DR. Prime editing for precise and highly versatile genome manipulation. Nat Rev Genet. 2023;24:161–177. doi: 10.1038/s41576-022-00541-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Yee JK. Off-target effects of engineered nucleases. FEBS J. 2016;283:3239–3248. doi: 10.1111/febs.13760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Lopes R, Prasad MK. Beyond the promise: evaluating and mitigating off-target effects in CRISPR gene editing for safer therapeutics. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2023;11:1339189. doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2023.1339189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Reardon S. First CRISPR clinical trial gets green light from US panel. Nature. 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 107.Liu Q. World-First Phase I Clinical Trial for CRISPR-Cas9 PD-1-Edited T-Cells in Advanced Nonsmall Cell Lung Cancer. Glob Med Genet. 2020;7:73–74. doi: 10.1055/s-0040-1721451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.UK trials first CRISPR-edited wheat in Europe. Nat Biotechnol. 2021;30:1174. doi: 10.1038/s41587-021-01098-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Cyranoski D. CRISPR gene-editing tested in a person for the first time. Nature. 2016;539:479. doi: 10.1038/nature.2016.20988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Millette K, Georgia S. Gene Editing and Human Pluripotent Stem Cells: Tools for Advancing Diabetes Disease Modeling and Beta-Cell Development. Curr Diab Rep. 2017;17:116. doi: 10.1007/s11892-017-0947-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Akhavan S, Tutunchi S, Malmir A, Ajorlou P, Jalili A, Panahi G. Molecular study of the proliferation process of beta cells derived from pluripotent stem cells. Mol Biol Rep. 2022;49:1429–1436. doi: 10.1007/s11033-021-06892-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Sun LL, Liu TJ, Li L, Tang W, Zou JJ, Chen XF, Zheng JY, Jiang BG, Shi YQ. Transplantation of betatrophin-expressing adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells induces β-cell proliferation in diabetic mice. Int J Mol Med. 2017;30:936–948. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2017.2914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]