Abstract

Triple-stranded DNA structures can be formed in living cells, either by native DNA sequences or following the application of antigene strategies, in which triplex-forming oligonucleotides are targeted to the nucleus. Recent studies imply that triplex motifs may play a role in DNA transcription, recombination and condensation processes in vivo. Here we show that very short triple-stranded DNA motifs, but not double-stranded segments of a comparable length, self-assemble into highly condensed and ordered structures. The condensation process, studied by circular dichroism and polarized-light microscopy, occurs under conditions that mimic cellular environments in terms of ionic strength, ionic composition and crowding. We argue that the unique tendency of triplex DNA structures to self-assemble, a priori unexpected in light of the very short length and the large charge density of these motifs, reflects the presence of strong attractive interactions that result from enhanced ion correlations. The results provide, as such, a direct experimental link between charge density, attractive interactions between like-charge polymers and DNA packaging. Moreover, the observations strongly support the notion that triple-stranded DNA motifs may be involved in the regulation of chromosome organization in living cells.

INTRODUCTION

DNA microheterogeneity, i.e. the formation of short non-B-DNA segments that are interspersed within the B-type double helix, is a well-established notion. It is known that local DNA conformations are sequence dependent and that DNA structural polymorphism may range from minor distortions at particular sites to major deviations from the B-DNA motif. These deviations include changes in DNA trajectory, handedness, number of strands in the helix and modes of base pairing (1–4). It is also widely accepted that whereas modified DNA structures are in general thermodynamically unstable under physiological conditions, their intracellular stability can be substantially enhanced by specific DNA-binding proteins, as well as by torsional stress that is effected by unconstrained supercoiling or transcriptional activity. Indeed, the in vivo existence of non-B-DNA motifs, including left-handed Z-DNA, cruciforms and triplex or quadruplex structures, has been repeatedly indicated by genetic and biochemical studies (2,4,5).

An issue that remains controversial, however, concerns the physiological roles and significance of the altered DNA structures. Several studies have pointed towards the possibility that non-B-DNA motifs play a role in regulating replication and transcription processes, serve as specific recognition signals for regulatory DNA-binding proteins and affect the rate of mutation and recombination events (2,4,6–8). In particular, it is becoming increasingly evident that DNA microheterogeneity may play an important role in promoting and regulating DNA condensation processes (9,10). Indeed, transition of right-handed B-DNA into the left-handed Z motif was shown to be accompanied by DNA condensation (11,12). Clusters of Z-DNA segments inserted into plasmids were found to substantially promote condensation of these plasmids (13). Moreover, the structural properties of DNA condensates derived from supercoiled DNA plasmids were reported to be dictated by the supercoiling parameters (14). These parameters are, in turn, modulated by right- to left-handed conformational changes that are sustained by particular segments within the constituent plasmid molecules. Similarly, several studies indicated that the condensation pathway of DNA molecules and the morphology of the resulting aggregates are highly sensitive to the presence of adenine tracts (15) or of telomere repeat sequences (16), as well as to the presence of sequence-directed intrinsic DNA curvature (15).

Pyrimidine·purine tracts, which are widespread in eukaryotic genomes, may adopt a number of altered DNA conformations, including triple-stranded structures that are obtained upon binding of a single-stranded DNA segment to the major groove of duplex DNA (17). The presence of such triplex structures in cell nuclei has been demonstrated by immunofluorescence, using specific anti-triplex DNA monoclonal antibodies (5,18). Intracellular triplex formation is promoted not only by native sequences but also by synthetic oligonucleotides that are vectored into the nucleus. This process has recently attracted much interest since it can be used as a general approach to sequence-specific targeting of duplex DNA for both basic research and antigene therapy applications (19,20).

Binding of triplex-specific antibodies to cell nuclei was found to be particularly extensive at the end of S phase and during G2, indicating that formation of ‘native’ triplex DNA structures is enhanced in these phases and implying that such motifs might be involved in chromosome condensation (18). Triplex-mediated chromosome condensation was indeed indicated by two-dimensional gel electrophoresis (21). Moreover, long triplex motifs were shown to reveal a large tendency to self-associate (22).

In order to assess the notion that triple-stranded structures might affect and promote DNA condensation, we have studied the properties of triplex motifs under conditions that mimic the cellular environment in terms of ionic composition and crowding. We find that under such conditions, very short triple-stranded DNA segments, but not double-stranded DNA species of identical length, self-assemble into highly condensed and ordered liquid-crystalline aggregates.

These observations buttress the notion that transient formation of short triplex motifs within the genome may indeed play a role in chromosome organization. Moreover, the results imply that enhanced regional chromosome condensation should be considered as a potential physiological determinant, when the effects of administrated triplex-forming oligonucleotides (TFOs) are assessed. Finally, since the relatively high charge density that characterizes triplex DNA is expected to enhance repulsive electrostatic interactions, it is not immediately apparent why triple-stranded DNA structures should enhance condensation. We show, however, that triplex-promoted packaging can be fully accounted for by considerations pertaining to ion condensation and ion correlation on the surface of the DNA molecules. As such, our results strongly support the notion that ion correlation critically contributes to attractive interactions between rod-like polyelectrolytes of identical charge.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Oligodeoxynucleotides (ODNs) and chemicals

ODNs were purchased from Midland Certified Reagent Co. (Midland, TX) and purified by anion exchange HPLC. The concentration of the ODNs was determined by UV absorption using extinction coefficients calculated from published nearest neighbor parameters (23). The purified ODNs were extensively dialyzed against 20 mM piperazine-N,N′-bis(2-ethane sulfonic acid) (PIPES), pH 7.0.

Stock solutions of double-stranded forms were prepared by mixing equimolar solutions of complementary strands, heating to 90°C and slowly (0.5°C min–1) cooling to room temperature. Solutions were diluted to the required concentration in 20 mM PIPES buffer, containing salts and polyethylene glycol 8000 (PEG) as specified in the text. Triplex solutions were prepared by adding the TFOs to the preformed duplex solution. For the circular dichroism (CD) experiments performed at different salt concentrations, salt was added to a solution with a given composition of buffer, PEG, DNA and other salts to give the desired final concentration.

PEG was purchased from US Biochemical and was used at 15% (w/v).

Circular dichroism

CD spectra were recorded on an Aviv spectropolarimeter Model 202 at 25°C. DNA samples (1.6 µM, 18–26 µg/ml of the various duplex forms and 26–38 µg/ml of the triplex) were placed in a 1 cm path length square quartz cell and equilibrated for 5 min at the desired solution composition before scanning. Longer incubation (1 h) resulted in identical spectra. Spectra of buffer solution were subtracted to correct for baseline artifacts. CD spectra were normalized in units of molar ellipticity (deg cm–1 M–1). At least three CD measurements were conducted for each set of conditions. Notably, the magnitude (but not the sign) of non-conservative CD spectra revealed by DNA microaggregates has been shown to be highly sensitive to the order of addition of the various components (9). A size variability of 10–20% was obtained in these experiments.

UV spectrophotometry

Thermal transitions of the DNA samples (1.6 µM) were measured by monitoring UV absorption at 260 nm using a Cary 5E spectrophotometer (Varian) equipped with a Peltier temperature controller. Melting profiles were recorded at a heating rate of 0.5°C min–1.

Polarized light microscopy

DNA solutions (16 µM) were deposited between a slide and a coverslip that were immediately sealed with Torr-Seal (Varian) to prevent evaporation. Specimens were observed at 25°C through cross polarizers with the use of a quartz retardation plate positioned at an angle of 45° relative to the samples on a Zeiss microscope (Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany).

RESULTS

Condensation of short triplex DNA

The optical properties exhibited by short duplex and triplex DNA motifs (Table 1) were studied in mixtures containing 140 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2 and 1 mM spermine tetrachloride (designated as 140:1:1 mM K:Mg:spermine). This particular composition and concentration of cations was chosen because it has been shown to mimic the estimated ionic conditions within eukaryotic cells (24). Experiments were conducted in either the absence or presence of the polymer PEG that acts as a neutral crowding agent, thus providing a means for reproducing the extremely crowded intracellular milieu (25–28). The formation of triple-stranded DNA structures under the various conditions was confirmed by UV melting experiments, which indicated the characteristic double melting pattern (29).

Table 1. List of DNA species.

| DNA species |

Name |

| Oligonucleotides | |

| 5′-T18-3′ | T18 |

| 5′-A18-3′ | A18 |

| 5′-CGCA20CGC-3′ | ‘A20’ |

| 5′-GCGT20GCG-3′ | ‘T20’ |

| Duplex DNA | |

| 5′-A18-3′ | AT18 |

| 3′-T18-5′ | |

| 5′-CGCA20CGC-3′ | ‘AT20’ |

| 3′-GCGT20GCG-5′ | |

| Triplex DNA | |

| 5′-T18-3′ | TAT18 |

| 5′-A18-3′ | |

| 3′-T18-5′ | |

| 5′-GCGT20GCG-3′ | ‘TAT20’ |

| 5′-CGCA20CGC-3′ | |

| 3′-GCGT20GCG-5′ |

In the absence of PEG, solutions of both the duplex AT18 and the triplex TAT18 in a 140:1:1 mM K:Mg:spermine salt mixture remain clear and exhibit conservative CD spectra that are characteristic of short double- and triple-stranded oligonucleotides (Fig. 1). The presence of 15% PEG in the salt mixture containing the double-stranded species AT18 does not cause observable aggregation nor lead to any changes in the DNA optical properties. In sharp contrast, the presence of 15% PEG in the salt mixture containing the triplex TAT18 results in salient formation of microaggregates. The CD spectrum revealed by this mixture is highly non-conservative, exhibiting a very large positive lobe centered at 278 nm (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

CD spectra exhibited by AT18 (1 and 3) and TAT18 (2 and 4) in a solution composed of 20 mM PIPES, 140 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2 and 1 mM spermine, pH 7.0, in the absence (1 and 2) and presence (3 and 4) of 15% PEG. Samples were monitored at 25°C. DNA concentration in all experiments was 1.6 µM. (Insert) Spectra 1–3 at magnified scale.

The anomalous CD signals revealed by TAT18 indicate that under the specified conditions, triple-stranded DNA species form highly condensed aggregates characterized by a well-defined long range chiral order (30). The formation of such tightly packed and ordered DNA aggregates has been extensively studied and was found to be induced either by DNA charge neutralization or by DNA confinement in small volumes (31). It has, however, been repeatedly shown that DNA segments <150 bp cannot undergo condensation from dilute solution into ordered aggregates. This has been attributed to the inability of short segments to produce cumulative attractive interactions that would be strong enough to stabilize a condensation nucleus (32). Similarly, ordered DNA packaging promoted by DNA confinement has not been demonstrated for segments <130 bp and a critical minimal segment size has been postulated (33). The finding that triplex DNA segments of only 18 bases are capable of forming chiral aggregates is, therefore, intriguing.

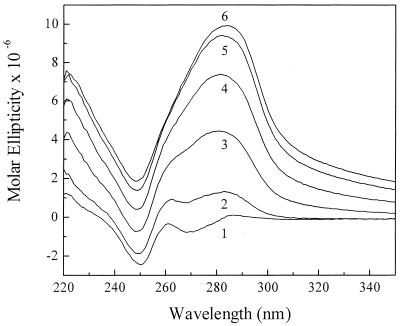

The interaction of the T18 oligonucleotide with the double-stranded AT18 to form the TAT18 triplex could, in principle, lead to the assembly of long wire-like superstructures. Such a self-assembly may result from an out-of-register binding of the T18 strand to two duplex segments, causing them to stick together in a mechanism similar to that previously shown to occur in guanine-rich oligonucleotide (34). In order to rule out the possibility that the ordered packaging of TAT18 represents condensation of self-assembled long wires and not of short, well-defined segments, we have studied the effects of the above-specified ionic environment and PEG on the triplex ‘TAT20’. All three strands of this triplex motif contain C and G bases at both ends, thus effectively destabilizing out-of-register wire-like long assemblies. As was observed for the AT18 segment, solutions of the double-stranded ‘AT20’ in 140:1:1 mM K:Mg:spermine and 15% PEG remain clear and exhibit a conservative CD spectrum (Fig. 2). Yet, upon addition of the triple-strand-forming oligonucleotide ‘T20’ in increasing amounts, the magnitude of the CD signals progressively increases and the spectra assume a non-conservative shape (Fig. 2). The alteration of the optical properties proceeds until complete saturation of the duplex by the third strand occurs (corresponding to curve 6) and is accompanied by the appearance of microaggregates. Addition of ‘T20’ in excess to a 1:1 molar ratio of single-strand to duplex species does not result in further changes of the non-conservative ellipticity.

Figure 2.

CD spectra revealed by ‘AT20’ (1.6 µM) upon progressive addition of ‘T20’ (20 mM PIPES, 140 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 1 mM spermine and 15% PEG, pH 7.0). The molar ratios between ‘T20’ and ‘AT20’ are: 0 (1), 0.2 (2), 0.4, (3), 0.6 (4), 0.8 (5) and 1.0 (6). Further increase in the molar ratio does not affect the CD spectrum. Samples were monitored at 25°C.

The optical properties exhibited by TAT18 and ‘TAT20’ demonstrate that ordered chiral condensation can be sustained by triplex DNA motifs that are well defined in terms of composition and length. The results further indicate that ordered packaging of very short DNA segments is uniquely and exclusively promoted by triple-stranded motifs. This notion is buttressed by the observation that addition of the oligonucleotide ‘A20’ to the duplex ‘AT20’ in a solution consisting of 140:1:1 mM K:Mg:spermine and 15% PEG has no effect on the chirality of the solution, which remains conservative and characteristic of a double-stranded oligonucleotide (results not shown). Indeed, triplex motifs composed of poly(T)·2poly(A) were found to be highly unstable (35). Moreover, following addition of ‘A20’ to the triplex ‘TAT20’ in 140:1:1 mM K:Mg:spermine and 15% PEG, the non-conservative CD spectra are suppressed and replaced by a conservative spectrum characteristic of double-stranded DNA segments. This observation further supports the suggestion that chiral packaging of very short DNA segments is specifically promoted by triplex motifs, since addition of ‘A20’ to ‘TAT20’ results in dissociation of the triplex into a double-stranded structure. The occurrence of such a dissociation (36), which proceeds according to: ‘TAT20’ + ‘A20’ ⇔ 2 ‘AT20’, was unambiguously demonstrated by UV melting experiments, where only one transition, characteristic of ‘AT20’ melting, is detected (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

UV (A260) melting curves of the triple-stranded motif ‘TAT20’ (1.6 µM, in 20 mM PIPES, 140 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 1 mM spermine) in the absence (1) and presence (2) of 15% PEG. The low and high temperature transitions correspond to the triplex and duplex melting, respectively. Curve 3 is the melting curve of a 1:1 molar ratio mixture of ‘A20’ and ‘TAT20’, in both the absence and presence of PEG. Notably, whereas PEG is shown to stabilize the triplex motif, no such effect is observed for duplex DNA, as indeed previously reported (49). (Insert) Corresponding derivative curves dA260/dT.

Nature of triplex DNA aggregates

The large non-conservative CD spectra exhibited by triplex DNA species in 140:1:1 mM K:Mg:spermine and 15% PEG, as well as the appearance of microaggreagates, imply that under such conditions short triple-stranded DNA segments assemble into a cholesteric liquid-crystalline phase. Such a phase is characterized by its large birefringence (37), which can be detected by polarized light. Polarized light microscopy of ‘TAT20’ in 140:1:1 mM K:Mg:spermine and 15% PEG reveals highly birefringent fluid droplets that are floating in a non-birefringent isotropic phase (Fig. 4). The droplets, which segregate from the dilute supernatant, appear to represent a large-pitch cholesteric mesophase. Notably, no birefringent droplets could be detected in mixtures containing the duplex ‘AT20’ in 140:1:1 mM K:Mg:spermine and 15% PEG, thus supporting the notion that very short double-stranded DNA segments cannot segregate into chiral condensed phases.

Figure 4.

Liquid-crystalline phase of ‘TAT20’ observed by polarized light microscopy at 25°C. Samples consisted of DNA (16 µM) in 20 mM PIPES, 140 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 1 mM spermine and 15% PEG, pH 7.0. Final magnification ×1000.

Factors affecting triplex condensation

In order to assess the effects of the various ionic components on the chiral condensation of short triplex structures, the concentrations of these components have been systematically varied. As shown in Figure 5A, increasing the concentration of the monovalent ion K+ above 140 mM, while keeping the concentrations of all other components unaltered, results in a large and progressive decrease in the non-conservative ellipticities. At KCl concentration of 250 mM or higher only conservative CD spectra characteristic of non-aggregated triplex motifs are observed. Notably, at these concentrations the triplex-containing solutions become clear and do not exhibit any birefringence. Decreasing the concentration of K+ to 100 mM has no effect on the non-conservative ellipticitiy revealed by the triplex motifs.

Figure 5.

CD spectra of ‘TAT20’ (1.6 µM) at different KCl or spermine concentrations. (A) ‘TAT20’ in 20 mM PIPES, 1 mM MgCl2, 1 mM spermine, 15% PEG and the following KCl concentrations (mM): 140 (1), 200 (2), 250 (3) and 300 (4). (B) ‘TAT20’ in 20 mM PIPES, 140 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 15% PEG and the following spermine concentrations (mM): 0 (1), 0.5 (2), 1.0 (3), 1.5 (4), 2 (5), 2.5 (6), 3.0 (7) and 4.0 (8). The shift in ellipticity maxima exhibited upon the progressive addition of spermine is assigned to the very large sensitivity of non-conservative CD spectra to minute changes in the structural parameters of the cholesteric phase (14).

The optical properties of the short triple-stranded DNA segments are also found to be highly sensitive to the concentration of the tetravalent cation spermine (Fig. 5B). In the absence of the polyamine, or in its presence at a concentration of 0.5 mM, triplex DNA solutions containing 140 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2 and 15% PEG are clear, not birefringent, and reveal conservative CD spectra characteristic of short non-aggregated triple-stranded structures. Increasing spermine concentration to 1 mM results in microaggregation, appearance of birefringent patterns and large, positive, non-conservative CD spectra. At spermine concentrations >1.5 mM, the size of the ellipticities substantially and progressively decreases.

In contrast to the salient effects exerted by KCl and spermine on the structural properties of the short triple-stranded DNA segments, variation of MgCl2 results in negligible effects on these properties. In the absence of MgCl2, the CD spectrum exhibited by the triplex motif is positive and non-conservative, albeit slightly smaller than the spectrum revealed in the presence of 1 mM MgCl2. Increasing the concentration of MgCl2 to values that are >1 mM (studied up to 5 mM) leads to an attenuation of the non-conservative ellipticities. This attenuation is, however, smaller than that detected upon increasing the concentration of spermine (results not shown).

Notably, no microaggregation, birefringence or non-conservative CD spectra are revealed by the various triplex structures in the absence of the neutral polymer PEG. The triple-stranded forms in a 140:1:1 mM K:Mg:spermine salt mixture exhibit only conservative ellipticities characteristic of a short triplex motif.

DISCUSSION

Physical aspects of triplex DNA condensation

The results reported in this study indicate that triple-stranded DNA segments undergo packaging into tight, highly ordered chiral condensates under conditions that mimic the estimated ionic conditions within eukaryotic cells, as well as simulate the crowded environment that characterizes the cellular milieu. Moreover, the observations imply that such conditions specifically and uniquely promote a cholesteric self-assembly of very short triplex motifs, but not of double-stranded DNA segments of identical length.

These results are intriguing for several reasons. First, according to the mean field Poisson–Boltzmann approach, two like-charge polymers such as DNA molecules (or, similarly, two like-charge surfaces) are expected to repel each other under all conditions (38,39). The very occurrence of DNA packaging thus seems to contradict the basic Poisson–Boltzmann theory because it indicates that under certain conditions attraction between DNA molecules outweighs repulsion. Second, since the charge density of triple-stranded DNA conformations is substantially higher than that characterizing duplex motifs, electrostatic repulsion between triplex DNA is supposed to be larger than that revealed by duplex structures. Consequently, it could be expected that under a given set of solution conditions and for a particular DNA length, the energy barrier for triplex DNA packaging would be higher than that revealed by duplex condensation, in contrast to the observations presented here. Third, numerous studies have indicated that for DNA condensation into ordered liquid-crystalline phases to occur, a minimal size of the DNA segments is required. The strict minimal length prerequisite has been interpreted in terms of cumulative attractive DNA–DNA interactions that are required to stabilize an initial nucleating condensate (32). Thus, if DNA molecules are too short to provide a specific threshold of attractive free energy, the resulting nucleus would be unstable and unable to add more molecules. Indeed, ordered packaging induced either by DNA confinement or by DNA neutralization has not been hitherto observed for segments <130 bp. The finding that triple-stranded DNA segments of 18 bases readily form ordered chiral condensates is therefore unexpected. An additional intriguing observation concerns the resolubilization of microaggregates and the concomitant disappearance of non-conservative ellipticities following the increase in cation concentration.

DNA condensation has been analyzed within the framework of two interrelated theories: counterion condensation and counterion correlation. Manning’s counterion condensation theory predicts the fraction of DNA charge that is specifically neutralized by ‘condensed’ cations of a given valency (40). Following interaction with polyelectrolytes, condensed ions remain delocalized, capable of moving in an unrestrained manner along the charged polymers. The magnitude of the fractional neutralization provided by condensed ions is given by:

1 – 1/Zζ 1

where Z is the counterion valency and ζ denotes the Manning parameter. This dimensionless parameter is defined by the ratio

ζ = lB/b 2

where lB is the Bjerrum length that corresponds to the distance at which the electrostatic potential between two charges equals their thermal energy kT (∼7.1 Å for aqueous solutions at room temperature) and 1/b represents the line density of fixed charges along the polyelectrolyte. Thus, the counterion condensation approach predicts that saturating monovalent cations will neutralize 76% of the charge on duplex DNA, whereas saturating divalent and trivalent cations are expected to neutralize 88 and 92% of the charge, respectively. Since DNA condensation has been shown to occur only when 89–90% of the polyelectrolyte charge is neutralized (41), mono or divalent cations cannot promote DNA packaging in aqueous solutions and trivalent or higher valency ions are required for this process.

The line density 1/b of fixed charges along triple-stranded DNA motifs is higher than in duplex structures (0.9 and 0.6 Å–1, respectively) and, hence, ζ(triplex) is larger than ζ(duplex). It follows from equation 1 that the higher charge density characterizing triple DNA strands will result in a larger magnitude of charge neutralization by condensed ions for this motif relative to the duplex structure. Specifically, whereas 88% of the fixed charge on double-stranded DNA will be neutralized by divalent cations, triplex motifs will sustain 92% neutralization.

These considerations indicate that ion condensation facilitates DNA condensation by substantially attenuating the net charge of the polyelectrolyte, thereby reducing electrostatic repulsion. It is also evident that charge neutralization and hence packaging of triple-stranded structures should be promoted by ion condensation to a greater extent than duplex DNA. The phenomenon of ion condensation is, however, insufficient to fully account for DNA condensation since it fails to directly indicate a source of attractive interactions required for packaging; even tri or tetravalent cations condensed on triplex DNA leave this motif with a net negative charge.

An attractive force that outweighs repulsion results, nevertheless, from the particular properties of condensed ions which, being fully mobile, allow for the emergence of ion correlation. Random fluctuations of counterion concentrations were originally predicted by Oosawa to result in charge inhomogeneities (42). At polyelectrolyte separation distances below the Bjerrum length, these inhomogeneities lead to attractive components (43), whose source is akin to that exhibited by van der Waal’s forces (38). Rouzina and Bloomfield developed a model according to which Coulomb repulsion between condensed counterions produces a periodic alteration of positive and negative charges at the surface of the polyelectrolyte (39). Electrostatic attraction is obtained when such surface patterns, belonging to two different polyelectrolytes, complementarily adjust to each other. A large entropic contribution to attractive interactions between two like-charge surfaces, which derives from the overlap of condensed ion layers from two different polyelectrolytes, has also been suggested (38). Thus, DNA packaging results from both direct and indirect effects associated with ion condensation: partial charge neutralization and local attractive interactions.

The particularly effective packaging of triplex DNA motifs reported in this study can be interpreted in terms of the model developed by Rouzina and Bloomfield (39). The model predicts that when the two complementary surfaces are superimposed (i.e. reach zero separation), the attractive electrostatic pressure between these surfaces is given by:

Pel0 = 2πσ2/ɛ 3

where σ is the surface charge density of the polyelectrolyte and ɛ is the solution dielectric constant. It follows that maximum attractive pressure between like-charge surfaces strongly correlates with the surface charge density. Thus, not only does the higher charge density of the triplex motifs promote charge neutralization through ion condensation, but it also substantially enhances attractive electrostatic interactions between these motifs through ion correlation. It has indeed been previously reported that long triplex structures reveal a higher tendency to undergo spermine-mediated aggregation and precipitation than duplex motifs (29). The different behavior was, however, interpreted in terms of specific preferential binding of the polyamine to the triplex motif and, hence, enhanced charge neutralization. Although such preferential binding may be present and affect condensation, we submit that the enhanced tendency of triplex DNA structures to undergo ordered packaging represents a general outcome of the large charge density which characterizes these structures.

Notably, the notion that increased charge density of DNA molecules may promote their condensation has recently been tested by investigating DNA packaging in borate-containing buffers, in which DNA negative charge is augmented. The lack of observed effect in this case was assigned to polyvalent ion-mediated hindrance of DNA–borate association (44). The findings reported here, which indicate that very short DNA segments undergo condensation when organized as a triple strand, but not as a double strand, thus provide a direct experimental link between charge density, ion correlation, attractive interactions and DNA packaging. This link is further substantiated by the observation that condensation of a short triplex absolutely requires the presence of the neutral polymer PEG. Specifically, ion correlation-mediated attractive interactions between like-charge surfaces are short range. The decay length of counterion correlation attraction scales with the average distance aZ between ions condensed to the DNA. This distance is given by (39):

aZ = (zqe/σ)1/2 4

where qe is the electron charge.

It follows that while the magnitude of attractive interactions is larger for triplex structures than for double-stranded motifs (equation 3), the decay length of this force is shorter. Hence, for triplex conformations to self-assemble and form stable aggregates, the molecules must be brought into very close vicinity. PEG has been shown to act as a potent osmotic stressing agent (45), to effectively induce DNA phase separation (46) and to exert volume exclusion (47,48). The resulting effect is a substantial DNA crowding that has been shown to increase the extent of associations between macromolecules (25,26). Indeed, we have recently found that in the presence of PEG the stability of triplex motifs is significantly enhanced (49). We therefore submit that the enhanced DNA crowding effected by PEG allows for attractive interactions to outweigh repulsion that is dominant at larger intermolecular separations. Apparently, for triplex structures, but not for duplex motifs, this effect is strong enough to overcome the intrinsic instability of the initial nucleating condensates that is associated with the very short length of the DNA segments used in this study.

The resolubilization of the microaggregates and concomitant disappearance of birefringence and of non-conservative ellipticities upon increasing the concentration of either monovalent (31) or polyvalent salts (37) has been previously detected and analyzed. In the case of monovalent cations, resolubilization has been assigned to competition (50). Specifically, although multivalent ions condense preferentially to DNA, excess of monovalent ions may reverse the trend, resulting in a weaker counterion condensation and hence stronger repulsion, as well as the screening of short range electrostatic interactions, thus negating condensation. Resolubilization of DNA aggregates by excess polyvalent cations has recently been proposed to result from charge inversion (51). According to this model, when the bulk concentration of multivalent cations is increased, the net negative charge density of DNA molecules progressively decreases due to ion condensation and becomes positive above a threshold value, leading to electrostatic repulsion. For short DNA molecules, the range of polyvalent cation concentrations within which packaging occurs is predicted to be narrower than for long molecules due to entropic considerations (51). This prediction is indeed confirmed by the observations presented in this study, which indicate a very narrow window of spermine concentrations in which packaging of the short triplex structures is induced.

Biological implications of triplex DNA condensation

We have recently reported that in the presence of a crowding agent that mimics the extremely crowded environments present in living systems, both formation and stability of triple-stranded DNA structures is substantially enhanced (49). It has also been shown that nucleosome-bound DNA is not refractory to the formation of stable triplex motifs, provided that these motifs are relatively short (52). Several studies have indicated that TFOs used for gene therapy can produce triple-stranded structures in vivo and that the resulting conformations specifically elicit a variety of physiological responses, including mutagenesis and recombination, as well as inhibition of transcription of the targeted genes (7,53–58). Other observations implied that formation of triplex DNA structures is enhanced at the end of the S phase and during G2, leading to the suggestion that these motifs might be involved in chromosome condensation (18).

Taken together, these observations strongly imply that short triple-stranded DNA motifs can be formed in the cellular context and may be physiologically significant. The results reported here highlight the dramatically enhanced inclination of very short triplex motifs to self-associate into highly condensed structures under ionic and crowding conditions that mimic the cellular environment. It should be noted that such an enhanced tendency to condense might not be restricted to triplex–triplex interactions. Ray and Manning proposed a theory according to which attraction between polyelectrolytes may arise even if the individual charge density of each polyelectrolyte lies below the critical value required for counterion condensation and hence for packaging (59). Thus, DNA condensation may occur if the combined charge density of the charged polymers exceeds the critical value, indicating that the particular properties of triplex motifs may also promote triplex–duplex association and condensation.

In conjunction with these observations and considerations, our results imply that in vivo triplex formation either by native DNA sequences or following administration of TFOs may significantly affect the packaging state of the genome. Thus, even very short triplex motifs generated in vivo may exert their effect not only through local secondary structural modifications, but also via their potential ability to modulate the global organization of the chromosome.

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank S. Safran, V. Bloomfield and I. Rouzina for helpful discussions and suggestions. This work was supported by the Israel Science Foundation founded by the Academy of Sciences and Humanities and by the Minerva Foundation, Germany.

REFERENCES

- 1.Jaworski A., Hsieh,W.T., Blaho,J.A., Larson,J.E. and Wells,R.D. (1987) Left-handed DNA in vivo. Science, 238, 773–777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wells R.D. (1988) Unusual DNA structures. J. Biol. Chem., 263, 1095–1098. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Palecek E. (1991) Local supercoil-stabilized DNA structures. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol., 26, 151–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van Holde K. and Zlatanova,J. (1994) Unusual DNA structures, chromatin and transcription. Bioessays, 16, 59–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burkholder G.D., Latimer,L.J.P. and Lee,J.S. (1991) Immunofluorescent localization of triplex DNA in polytene chromosomes of Chironomus and Drosophila. Chromosoma, 101, 11–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wittig B., Wolfl,S., Dorbic,T., Vahrson,W. and Rich,A. (1992) Transcription of human c-myc in permeabilized nuclei is associated with formation of Z-DNA in three discrete regions of the gene. EMBO J., 11, 4653–4663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barre F.X., Ait-Si-Ali,S., Giovannangeli,C., Luis,R., Robin,P., Pritchard,L.L., Helene,C. and Harel-Bellan,A. (2000) Unambiguous demonstration of triple-helix-directed gene modification. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 97, 3084–3088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sheridan S.D., Opel,M.L. and Hatfield,G.W. (2001) Activation and repression of transcription initiation by a distant DNA structural transition. Mol. Microbiol., 40, 684–690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reich Z., Ghirlando,R. and Minsky,A. (1991) Secondary conformational polymorphism of nucleic acids as a possible functional link between cellular parameters and DNA packaging processes. Biochemistry, 30, 7828–7836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bloomfield V.A. (1996) DNA condensation. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol., 6, 334–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thomas T.J. and Bloomfield,V.A. (1985) Toroidal condensation of Z DNA and identification of an intermediate in the B to Z transition of poly(dG-m5dC) × poly(dG-m5dC). Biochemistry, 24, 713–719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chaires J.B. and Norcum,M.T. (1988) Structure and stability of Z* DNA. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn., 5, 1187–1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ma C., Sun,L. and Bloomfield,V.A. (1995) Condensation of plasmids enhanced by Z-DNA conformation of d(CG)n inserts. Biochemistry, 34, 3521–3528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Levin-Zaidman S., Reich,Z., Wachtel,E.J. and Minsky,A. (1996) Flow of structural information between four DNA conformational levels. Biochemistry, 35, 2985–2991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reich Z., Ghirlando,R. and Minsky,A. (1992) Nucleic acids packaging processes: effects of adenine tracts and sequence-dependent curvature. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn., 9, 1097–1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schnell J.R., Berman,J. and Bloomfield,V.A. (1998) Insertion of telomere repeat sequence decreases plasmid DNA condensation by cobalt(III) hexaammine. Biophys. J., 74, 1484–1491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sun J.S. and Helene,C. (1993) Oligonucleotide-directed triple-helix formation. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol., 3, 345–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Agazie Y.M., Burkholder,G.D. and Lee,J.S. (1996) Triplex DNA in the nucleus: direct binding of triplex-specific antibodies and their effect on transcription, replication and cell growth. Biochem. J., 316, 461–466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sun J.S., Garestier,T. and Helene,C. (1996) Oligonucleotide directed triple helix formation. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol., 6, 327–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Praseuth D., Guieysse,A.L. and Helene,C. (1999) Triple helix formation and the antigene strategy for sequence-specific control of gene expression. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 1489, 181–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hampel K.J. and Lee,J.S. (1993) Two-dimensional pulsed-field gel-electrophoresis of yeast chromosomes: evidence for triplex-mediated DNA condensation. Biochem. Cell Biol., 71, 190–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sakamoto N., Chastain,P.D., Parniewski,P., Ohshima,K., Pandolfo,M., Griffith,J.D. and Wells,R.D. (1999) Sticky DNA: self-association properties of long GAA·TTC repeats in R·R·Y triplex structures from Friedreich’s ataxia. Mol. Cell, 3, 465–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Puglisi J.D. and Tinoco,I.J. (1989) Absorbance melting curves of RNA. Methods Enzymol., 180, 304–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Singleton S.F. and Dervan,P.B. (1993) Equilibrium association constants for oligonucleotide-directed triple helix formation at single DNA sites: linkage to cation valence and concentration. Biochemistry, 32, 13171–13179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zimmerman S.B. (1993) Macromolecular crowding effects on macromolecular interactions: some implications for genome structure and function. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 1216, 175–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zimmerman S.B. and Minton,A.P. (1993) Macromolecular crowding: biochemical, biophysical and physiological consequences. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct., 22, 27–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ellis R.J. (2001) Macromolecular crowding: an important but neglected aspect of the intracellular environment. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol., 11, 114–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ellis R.J. (2001) Macromolecular crowding: obvious but underappreciated. Trends Biochem. Sci., 26, 597–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Saminathan M., Antony,T., Shirahata,A., Sigal,L.H., Thomas,T. and Thomas,T.J. (1999) Ionic and structural specificity effects of natural and synthetic polyamines on the aggregation and resolubilization of single-, double- and triple-stranded DNA. Biochemistry, 38, 3821–3830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Keller D. and Bustamante,C. (1986) Theory of the interaction of light with large inhomogeneous molecular aggregates. II. Psi-type circular dichroism. J. Chem. Phys., 84, 2972–2980. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pelta J., Durand,D., Doucet,J. and Livolant,F. (1996) DNA mesophases induced by spermidine: structural properties and biological implications. Biophys. J., 71, 48–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bloomfield V.A. (1991) Condensation of DNA by multivalent cations: considerations on mechanism. Biopolymers, 31, 1471–1481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Merchant K. and Rill,R.L. (1997) DNA length and concentration dependencies of anisotropic phase transitions of DNA solutions. Biophys. J., 73, 3154–3163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marsh T.C. and Henderson,E. (1994) G-wires: self-assembly of a telomeric oligonucleotide, d(GGGGTTGGGG), into large superstructures. Biochemistry, 33, 10718–10724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Howard F.B., Miles,H.T. and Ross,P.D. (1995) The poly(dT)·2poly(dA) triple helix. Biochemistry, 34, 7135–7144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Plum G.E. (1998) Thermodynamics of oligonucleotide triple helices. Biopolymers, 33, 241–256. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pelta J., Livolant,F. and Sikorav,J.L. (1996) DNA aggregation induced by polyamines and cobalthexamine. J. Biol. Chem., 271, 5656–5662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ray J. and Manning,G.S. (1994) Attractive force between two rodlike polyions mediated by the sharing of condensed counterions. Langmuir, 10, 2450–2461. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rouzina I. and Bloomfield,V.A. (1996) Macroion attraction due to electrostatic correlation between screening counterions. 1. Mobile surface-adsorbed ions and diffuse ion cloud. J. Phys. Chem., 100, 9977–9989. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Manning G.S. (1978) The molecular theory of polyelectrolyte solutions with applications to the electrostatic properties of polynucleotides. Q. Rev. Biophys., 1, 179–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wilson R.W. and Bloomfield,V.A. (1979) Counterion-induced condensation of deoxyribonucleic acid. A light-scattering study. Biochemistry, 18, 2192–2196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Oosawa F. (1971) Polyelectrolytes. Marcel Dekker, New York, NY.

- 43.Marquet R. and Houssier,C. (1991) Thermodynamics of cation-induced DNA condensation. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn., 9, 159–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schwinefus J.J. and Bloomfield,V.A. (2000) The greater negative charge density of DNA in Tris-borate buffers does not enhance DNA condensation by multivalent cations. Biopolymers, 54, 572–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Podgornik R., Strey,H.H., Gawrisch,K., Rau,D.C., Rupprecht,A. and Parsegian,V.A. (1996) Bond orientational order, molecular motion and free energy of high-density DNA mesophases. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 93, 4261–4266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Podgornik R., Strey,H.H., Rau,D.C. and Parsegian,V.A. (1995) Watching molecules crowd: DNA double helices under osmotic stress. Biophys. Chem., 57, 111–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Minton A.P. (1998) Molecular crowding: analysis of effects of high concentrations of inert cosolutes on biochemical equilibria and rates in terms of volume exclusion. Methods Enzymol., 295, 127–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Minton A.P. (2001) The influence of macromolecular crowding and macromolecular confinement on biochemical reactions in physiological media. J. Biol. Chem., 276, 10577–10580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Goobes R. and Minsky,A. (2001) Thermodynamic aspects of triplex DNA formation in crowded environments. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 123, 12692–12693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.de la Cruz M.O., Belloni,L., Delsanti,M., Dalbiez,J.P., Spalla,O. and Drifford,M. (1995) Precipitation of highly-charged polyelectrolyte solutions in the presence of multivalent salts. J. Chem. Phys., 103, 5781–5791. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nguyen T.T., Rouzina,I. and Shklovskii,B.I. (2000) Reentrant condensation of DNA induced by multivalent counterions. J. Chem. Phys., 112, 2562–2568. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Brown P.M. and Fox,K.R. (1998) DNA triple-helix formation on nucleosome-bound poly(dA)·poly(dT) tracts. Biochem. J., 333, 259–267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Giovannangeli C., Diviacco,S., Labrousse,V., Gryaznov,S., Charneau,P. and Helene,C. (1997) Accessibility of nuclear DNA to triplex-forming oligonucleotides: the integrated HIV-1 provirus as a target. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 94, 79–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Catapano C.V., McGuffie,E.M., Pacheco,D. and Carbone,G.M. (2000) Inhibition of gene expression and cell proliferation by triple helix-forming oligonucleotides directed to the c-myc gene. Biochemistry, 39, 5126–5138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bailey C. and Weeks,D.L. (2000) Understanding oligonucleotide-mediated inhibition of gene expression in Xenopus laevis oocytes. Nucleic Acids Res., 28, 1154–1161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Faria M., Wood,C.D., Perrouault,L., Nelson,J.S., Winter,A., White,M.R., Helene,C. and Giovannangeli,C. (2000) Targeted inhibition of transcription elongation in cells mediated by triplex-forming oligonucleotides. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 97, 3862–3867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Faria M., Wood,C.D., White,M.R., Helene,C. and Giovannangeli,C. (2001) Transcription inhibition induced by modified triple helix-forming oligonucleotides: a quantitative assay for evaluation in cells. J. Mol. Biol., 306, 15–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Luo Z., Macris,M.A., Faruqi,A.F. and Glazer,P.M. (2000) High-frequency intrachromosomal gene conversion induced by triplex-forming oligonucleotides microinjected into mouse cells. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 97, 9003–9008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ray J. and Manning,G.S. (1997) Effect of counterion valence and polymer charge density on the pair potential of two polyions. Macromolecules, 30, 5739–5744. [Google Scholar]