Abstract

Arts participation has been linked to positive health outcomes around the globe. As more research is taking place on this topic, there is heightened need for definitions for the complex concepts involved. While significant work to define “arts participation” has taken place in the arts sector, less work has been undertaken for the purpose of researching the arts in public health. This study developed a definition for “arts participation” to guide a national arts in public health research agenda and to advance and make more inclusive previous work to define the term. A convergent mixed-methods study design with sequential elements was used to iteratively develop a definition that integrated the perspectives of field experts as well as the general public. Literature review was followed by four iterative phases of data collection, analysis, and integration, and a proposed definition was iteratively revised at each stage. The final definition includes modes, or ways, in which people engage with the arts, and includes examples of various art forms intended to frame arts participation broadly and inclusively. This definition has the potential to help advance the quality and precision of research aimed at evaluating relationships between arts participation and health, as well as outcomes of arts-based health programs and interventions in communities. With its more inclusive framing than previous definitions, it can also help guide the development of more inclusive search strategies for evidence synthesis in this rapidly growing arena and assist researchers in developing more effective survey questions and instruments.

Keywords: arts, arts participation, health, public health, definition, arts in health

Background

Increasing attention is being given to the ways in which arts participation enhances individual and collective health and health equity (Fancourt & Finn, 2019; Jackson, 2021). For example, epidemiological studies focused on the impact of arts participation in national cohorts have revealed significant associations between arts participation and mental health (Bone et al., 2022), healthy aging (Rena et al., 2022), well-being (Bone et al., 2022), and mortality (Fancourt & Steptoe, 2019). Given its clear benefits to individual and population-level health outcomes, arts participation is increasingly being recognized as a health behavior and recognized by the public health sector as a health asset (Biden, 2022; Bone et al., 2021; Galea, 2021).

As relationships between arts participation and health are increasingly being studied, the need for definitions for the complex concepts involved in this research becomes more important. While concepts such as “the arts” rightly defy common definition, they must be defined or framed to enable precision and quality in research (Cousins et al., 2020; Raw et al., 2012). In addition, in order for the public health and arts in health fields to undertake meaningful research on the benefits of arts participation to health and health equity, definitions used in research must allow room for the full range of artistic and creative practices—including Indigenous, spiritual, cultural, and social practices—that exist across communities and groups, as opposed to more Euro-centric notions of art that exclude many of these practices, including those that are already deeply linked to health, well-being, social cohesion, and social change (Jackson, 2021; Parkinson, 2018; Van Styvendale et al., 2021).

While significant work to define “arts engagement” and “arts participation” has taken place in the arts sector (e.g., National Endowment for the Arts [NEA], 2019), less work has been undertaken for the purpose of researching the arts in public health. This study sought to establish an inclusive definition of “arts participation” for the purposes of researching a national arts in health initiative in the United States as well as for advancing previous work in this area and providing a foundation for public health research in this area of growing interest.

One notable study by Davies et al. (2012) in Australia created a definition of “arts engagement” for population-level health studies and has been a cornerstone in arts in health research over the past decade. It offers five categories of art forms—performing arts; visual arts, design, and craft; literature; community and cultural festivals, fairs, and events; and online, digital, and electronic arts. It also offers 91 types of arts activities positioned on a spectrum of passive to active engagement. While this taxonomy is broad, it lacks consideration of a wider range of cultural and Indigenous arts practices.

In the United Kingdom, a study of arts participation, illness, and health conducted by the Arts Council England framed “art engagement” across attendance and participation (Windsor, 2005). Arts participation was categorized across creative activities (e.g., drawing, writing poetry), sociable activities (e.g., clubbing, singing groups), and physically demanding activities (dance). England’s All-Party Parliamentary Group report on arts for health and well-being frames “the arts” inclusive of forms (dance, crafts, visual and performing arts, literature, film, music and singing) and includes places where arts engagement takes place, such as concert halls and heritage sites. It also includes activities that take place in the home, such as crafts and digital creativity (Coulter & Gordon-Nesbitt, 2017).

In the United States, the NEA has offered an evolving series of definitions that frame “arts participation” and “arts engagement.” In 2011, an NEA report based on the 2008 Survey of Public Participation in the Arts advanced the notion of arts engagement from generally synonymous with “arts attendance” to include “multiple modes of engagement” and a “broader scope of contexts and settings” (Novak-Leonard & Brown, 2011, p. 26). Those modes were defined as attendance, interactivity through electronic media, arts learning, and arts creation. In its reports on the 2012 Survey of Public Participation in the Arts, the NEA framed five broad areas of arts participation—arts attendance, reading literary works, arts consumption through electronic media, arts creation and performance, and arts learning (Iyengar et al., 2013). The report acknowledged the difficulty in defining or framing the concept of arts participation due to the ever-evolving nature of these categories and the arts forms and technologies they reference. In its report of the 2017 survey, the NEA (2019) further expanded its survey question to include a broader range of art forms and artistic modes.

Creatives Rebuild New York, an initiative designed to mobilize the power of the arts to support COVID-19 pandemic recovery and rebuilding in New York state, offered a broad framing of arts and cultural activities, including craft, dance, design, film, literary arts, media arts, music, oral traditions, social practice, and theater (Creatives Rebuild New York, 2022). This definition denotes key disciplines and specific examples that frame a broad and inclusive arena of arts and cultural forms and practices in the United States.

Recently and in consideration of the value of the arts to health, the National Opinion Research Center (NORC, 2021) offered a definition of “arts engagement” that delineates art forms (performing arts, visual arts, crafts, creative writing, film/television/media), modes of engagement (active/doing and passive/consuming/attending), venues for engagement (arts venues, public spaces, community centers, homes), and providers of opportunities (arts organizations, community-based organizations, health care providers).

As such, a gap in the literature surrounding a comprehensive, culturally inclusive definition for arts participation exists. Pertaining to the comprehensiveness of arts participation definitions, several constructs, such as modes and forms of arts participation, exist distinctly across seminal definitions for arts participation but have yet to be integrated in a meaningful way. Furthermore, current definitions lack a community-based lens as well as cultural and Indigenous inclusivity. These current limitations not only affect arts participation definitions but also have implications for understanding diverse experiences related to individual health and well-being across a broader scope of practice.

The current study was initiated by the need for a more inclusive definition of “arts participation” for the purpose of researching the One Nation/One Project (ONOP) initiative in the United States. ONOP is a multifaceted initiative designed to engage the arts to strengthen the social fabric of U.S. communities on the heels of the COVID-19 pandemic. The initiative leverages collaborations between the arts, public health, and municipal sectors to build health, health equity, and well-being. The study sought to establish a more inclusive working definition as a foundation for ONOP’s research as well as for advancing community-based public health research on the health benefits of arts participation for individuals and communities.

Method

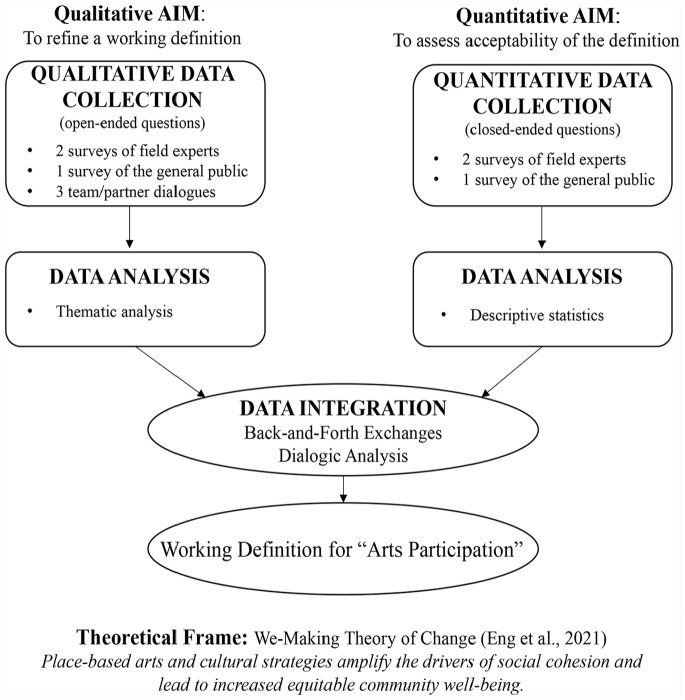

This convergent mixed-methods study with sequential elements was conducted by a research team at a public university, which serves as a partner to ONOP. The study was approved as exempt by the university’s institutional review board (IRB). The study utilized the “We-Making” theory of change (Engh et al., 2021) as its theoretical frame. This theory of change asserts that place-based arts and cultural strategies amplify the drivers of social cohesion and lead to increased equitable community well-being. ONOP’s overarching research agenda seeks to test this theory of change.

The study included a literature review followed by four iterative phases of data collection, analysis, and revision to the working definition. Study data were derived from three surveys conducted via the institutional Qualtrics and Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) interfaces between April 27 and November 14, 2022, as well from dialogues with the program team and partners. Each of the surveys collected both quantitative and qualitative data. Descriptive statistics were produced separately from each survey, as were qualitative themes and subthemes from the surveys and program team/partner dialogues.

Thematic analyses were conducted on the narrative data (Braun & Clarke, 2019). A team of six researchers, half of whom did not participate in the development of the original draft definition, engaged in this thematic analyses to reduce bias. After coding the data independently, the research team members engaged in dialogue to build consensus and a final set of themes for each data set. Data were integrated through back-and-forth exchanges that allowed comparison of quantitative and qualitative data in each phase of the project, and revisions were made iteratively (Fetters, 2020). A final data integration phase utilized back-and-forth exchanges to distill all feedback and to create a final version of the definition (see Figure 1). Like Davies et al. (2012), this study valued and engaged the views and ratings of field experts, but it additionally engaged perspectives of members of the general public.

Figure 1.

Study Model: A Convergent Mixed-Methods Study With Sequential Elements

Study Participants

Four groups of people were involved in the study: (a) cross-disciplinary field experts, (b) cross-disciplinary ONOP project leaders and partners, (c) the general public, and (d) the research team (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Participant Demographics

| Personal Identifiers | Research team (n = 8) | Project team (n = 12) | Field experts (n = 47) | General public (n = 267) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Race | ||||

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0.4% |

| Asian | 12.5% | 17% | 9% | 3.0% |

| Black or African American | 12.5% | 33% | 19% | 8% |

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0.8% |

| White | 75% | 33% | 70% | 84% |

| Other | 0% | 0% | 4% | 4% |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Hispanic, Latino/a/x, or of Spanish origin | 12.5% | 17% | 2% | 6% |

| Not Hispanic, Latino/a/x, or of Spanish origin | 87.5% | 0% | 98% | 94% |

| Gender (gender was not collected in the field expert surveys) | ||||

| Male | 12.5% | 42% | N/A | 23% |

| Female | 87.5% | 58% | N/A | 74% |

| Nonbinary | 0% | 0% | N/A | 3% |

| Other | 0% | 0% | N/A | 0.4% |

Study participants included convenience samples of 48 field experts over the age of 18, 12 ONOP team members/partners, and 267 members of the general public. The sample of field experts was drawn from a database of individuals who work at the intersection of the arts and public health developed by the research team for previous projects. Eighty individuals were selected from this list based on their disciplinary purview (arts/public health/community development) and their expertise related specifically to research or practice at the intersection of the arts and public health. An individual was considered a suitable expert if they (a) held/had previously held a leadership or academic role in an arts or public health agency or program AND had experience at the intersection of arts and public health, and/or (b) had authored a peer-reviewed publication or field report related to arts participation or use of the arts in public health. The sample of the general public was accessed through the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and Vanderbilt University’s ResearchMatch platform, a national database of research volunteers (Harris et al., 2012).

Data Collection and Analysis

Phase 1

Following an initial review of published literature and field reports that offer or include a definition of arts participation, the research team developed a first draft definition (see Supplemental Materials). The initial definition was highly influenced by Davies et al. (2012) and Creatives Rebuild New York (2022). It was reviewed by the project team, who provided feedback in a dialogic process. Thematic analysis was used to develop themes from the feedback. The research team examined these themes and engaged in dialogue that encouraged assent, dissent, and consensus building as a form of further analysis, which resulted in a second draft definition.

Phase 2

An original survey (see Supplemental Materials) was developed for assessment of the definition by field experts. The 13-item survey was tested for clarity, reliability, and comfort by 15 members of the principal investigator’s research lab. It was then sent via email to the 80 experts (six undeliverable). The email linked to the survey in Qualtrics, a secure site with SAS 70 certification and encrypted for security purposes using Secure Socket Layers (SSL). Only the study investigators had access to the data. Participants’ IP addresses were not available to investigators.

Data were analyzed quantitatively (mean/standard deviation, median/range, frequency/%) to produce descriptive statistics and qualitatively to produce themes. Again, the research team examined the themes and subthemes and engaged in dialogue as a form of further analysis, which resulted in a third draft definition (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Survey 1 Mixed-Methods Results: Statistics, Themes, Subthemes, and Revisions

| Quantitative Results (n = 18) | Qualitative Results | Revisions | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Question Type | Theme | Subthemes | ||

| Questions about categories | Do the three categories—Arts Practice; Cultural Practice; and Everyday Human Creativity—collectively encompass ways in which people participate in the arts? Yes—93% No—7% |

Three Section 1 categories (types/ways) don’t work well | • Categories are confusing • Categories don’t make a cohesive set • Arts practice category is confusing • Consider intent/ motivation |

• Changed section header from types to domains re: motivation/intent • Added new section for modes/ways people engage (as in NEA, 2019) • Added descriptors to each category |

| Questions about examples | Do these eight categories represent a broad and inclusive array of arts disciplines? Yes—77%; No—23% Do the disciplines and examples provided in the proposed definition represent the diverse array of arts and cultural practices and cultures in the United States? Yes—85%; No—15% |

Discipline headers in Section 2 are unclear | • Use clearer headers, e.g., music, theater | • Used clearer primary art forms as headers |

| Other questions | Do the disciplines and examples provided in the proposed definition represent the diverse array of arts and cultural practices and cultures in the United States? Extremely well—8.33% Very well—50% Moderately well—33.3% Slightly well—8.33% Mean—2.42/5 Are the examples provided in parentheses within each category in this section helpful in adding context or clarity to the categories? Yes—86%; No—14% |

Overlap in examples across categories is problematic | Interdisciplinary arts category is unnecessary/confusing in relation to others | • Re-examined and organized examples across categories • Removed Interdisciplinary arts category |

| More clarity is needed overall | Need for clarity re: active, passive, receptive concepts | Added language in intro to address spectrum of participation from creating to experiencing to observing | ||

Note. NEA = National Endowment for the Arts.

Subsequently, the revised definition was presented to the ONOP team, who engaged in dialogic critique. Investigators documented feedback in field notes and then developed themes. The research team examined the themes and engaged in analytic dialogue, which resulted in a fourth draft definition.

Phase 3

A second survey was developed to garner additional feedback from field experts on the fourth version of the definition. This survey consisted of the same three demographic questions, along with one closed-ended question (see Supplemental Materials).

The survey was conducted via Qualtrics and sent to the same 80 individuals between July 20 and August 10, 2022 (five were undeliverable). The data were analyzed, and the definition was iteratively refined using the same methods and processes as in Phase 2, resulting in a fifth version of the definition (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Survey 2 Thematic Analysis Results: Themes, Subthemes, and Key Resulting Revisions

| Theme | Subthemes | Key resulting revisions |

|---|---|---|

| Domains are confusing and not working | • Too many other potential motivations • Categories do not really represent intents or motivations |

Removed domains category from the definition and included its content in the pre-amble but without reference to intent or motivation. Determined that intents or motivations were outside of the scope of a definition, which sought in this study to inform what we mean when we say “arts participation” |

| Some confusion around modes | • “In person” may be missing • More than just digital and live |

Added “spanning a spectrum of active to receptive participation” to the descriptor in parentheses in the category header; added “live” to attending category |

| Health and well-being as motivations are missing | As noted above, removed the domains category and reference to intent and motivation |

Phase 4

A third survey (see Supplemental Materials) was developed to garner input from individuals representing the general public. Separate IRB approval was granted for this survey, and a convenience sample of research volunteers was accessed through the national ResearchMatch Network. The survey was administered through the university’s secure REDCap system. These data were analyzed as in Phases 2 and 3.

Data Integration

Data were integrated through back-and-forth exchanges and through a spiraling process that examined the descriptive statistics and themes, along with researcher memos, in a sequential manner intended to distill the most salient perspectives and priorities regarding both the structural elements and specific components of the definition (Fetters, 2020). The research team engaged a dialogic process to make final revisions to the definition in the final integration phase (Matusov et al., 2019).

Results

Summary of Respondents

Project Team Dialogue 1

Nine members of the project/partner team met via Zoom to consider the first draft of the definition and to provide feedback. Three themes emerged from this dialogue:

“Arts practice” should include social practice

Traditional or ceremonial arts should be included

“Cultural Practice” could be a separate category

Survey 1

The first survey was administered from April 27 to May 10, 2022, via email to 80 individuals and reached 74 (six undeliverable). Twenty-two people (30%) began the survey, and 18 (24%) complete responses were analyzed.

Quantitative results

The quantitative results showed approval for the three categories in Section 1, but less approval for arts disciplines categories and examples. See Table 2.

Qualitative results

Four themes and seven subthemes resulted from the thematic analysis of open-ended responses (see Table 2).

This process of analysis and distillation resulted in a clearer alignment with the definitions offered by the NEA and a revised working definition (see Supplemental Materials).

Project Team Dialogue 2

Nine members of the project team met to consider the first draft of the definition and to provide feedback. After providing the team with time to read and consider the definition, the principal investigator facilitated unstructured dialogue. Two themes emerged:

Confusion in modes category around distinctions between attending and consuming/live and digital

The notion of “live” should be considered in relation to attending in Section 2

Survey 2

The six-question survey was started by 37 people (49%), and 29 complete responses (40%) were analyzed. The second survey garnered a broader demographic representation than the first.

Quantitative data

Among the respondents, 55% (n = 16) identified as primarily affiliated with the arts and culture sector, 28% (n = 8) with the health sector, and 14% (n = 4) with the community development sector. When asked, on a scale of 1 to 10, how well the working definition framed “arts participation,” 70% (n = 21) selected 7 or above. The mean response was 8.04 (SD = 1.80).

Qualitative data

The first of two open-ended questions asked if any aspects or parts of the definition should be changed and, if so, what changes should be made. The second asked for additional comments or suggestions. From the thematic analysis, three themes and four subthemes were developed (Table 3).

Survey 3

The third survey, administered via REDCap between November 7 and 14, 2022, asked respondents from the general public to review the definition and respond to 10 questions. Four asked for demographic information, and six asked for feedback on the definition. The survey was opened by 316 people, and 267 responses (84%) were analyzed.

Quantitative data

Quantitative results indicated a very high level of approval and acceptability for the definition.

Qualitative data

In alignment with the quantitative data, open-ended responses indicated a high level of approval, with a common note that it is long/too long (Table 4).

Table 4.

Survey 3 Mixed-Methods Results: Statistics, Themes, Subthemes, and Revisions

| Quantitative | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Survey question | N | % missing | Response | M (SD) |

Median

(min–max) |

| From your perspective, how good is this definition of “arts participation?” (1 = not good, 10 = extremely good) | 257 | 3.75% | 1–6: 3% 7: 3% 8: 19% 9: 26% 10: 44% |

8.9 (1.4) |

9 (1–10) |

| Does this definition match with your understanding of what “arts participation” means? (y/n) | 267 | 0% | 1, Yes: 90% 2, Partially: 10% 3, No: .3% |

1.1 (0.3) |

1 (1–3) |

| Does this definition include the ways in which you participate in the arts? (y/n) | 265 | 0.75% | 1, Yes: 97% 2, No: 3% |

1.03 (0.2) |

1 (1–2) |

| From your perspective, are there any parts of this definition that should be changed? (y/n) | 264 | 1.1% | 1, Yes: 11% 2, No: 89% |

1.89 (0.3) |

2 (1–2) |

| Qualitative | |||||

| Survey question | Themes | Resulting revisions | |||

| Does this definition include the ways in which you participate in the arts? (y/n) (If no) What is missing? | (6 responses, no themes) | ||||

| From your perspective, are there any parts of this definition that should be changed? (y/n) (If yes) Please specify the changes that should be made. | • Definition is good/excellent • Definition is long/too long • Emphasize that examples are not meant to be inclusive |

• Removed a few insignificant words • Added: “examples provided are intended to suggest a broad range and are not intended to note every possible art form” |

|||

| Do you have any other comments? | • Definition is good/excellent • Examples are comprehensive • Definition is comprehensive • Definition is long/too long |

||||

Data Integration

The data integration process resulted in a final version of the definition, including five modes and six art forms through/in which people participate. This process also resulted in the re-integration of elements of participation related to social, civic, spiritual, and cultural arts practices that had been deleted in previous phases.

The Definition

The definition includes two sections. The first section defines modes, or ways, in which people engage with the arts. It includes participation by makers, collaborators, audiences, observers, and others. The second section includes various art forms intended to frame the arts broadly and inclusively. These modes and forms span a spectrum of participation from creating to actively experiencing to observing the arts. The examples provided suggest a broad range and are not intended to denote every possible mode or form of participation.

Modes (ways in which people engage, including informal, formal, live, virtual, individual, and group participation)

Attending live arts and cultural events and activities

Creating, practicing, performing, and sharing art

Participating in social, civic, spiritual, and cultural arts practices

Consuming arts via electronic, digital, or print media

Learning in, through, and about the arts

Forms (art forms or disciplines with which people engage; the examples provided are intended to suggest a broad range and are not intended to note every possible art form)

Dance/Movement (such as aerial, ballet, ballroom, ceremonial, contemporary, cultural, hip-hop, jazz, step, or tap)

Literary Arts (such as storytelling, fiction, nonfiction, short stories, memoir, screenwriting, poetry, literature for children, or graphic novels)

Media (such as film, animation, video, or other work at the intersection of technology, aesthetics, storytelling, and digital cultures)

Music (such as rap, choral, contemporary, experimental, gospel, instrumental, hip-hop, classical, chanting, rock, electronic, drumming, pop, world, or jazz)

Theater/Performance (such as theater, musical theater, devised theater, puppetry, performance art, ritual, opera, spoken word, stage design, circus arts, comedy)

Visual Arts, Craft, and Design (such as illustration, painting, drawing, collage, printmaking, installation, photography, gardening, sculpture, video art, street art, pottery, glass, jewelry, metalworking, textiles, fashion, culinary arts, and graphic, floral, architectural, environmental, or industrial design)

Discussion

Using a convergent mixed-methods design with sequential elements, and the input of 327 individuals, this study iteratively developed a definition of “arts participation.” The study aimed to create a more inclusive definition for both the purpose of ONOP research and for advancing the rapidly growing arena of public health research on the health benefits of arts participation for individuals and communities. The resulting definition advances previous definitions by recognizing and including a broader range of modes (e.g., social, civic, spiritual, and cultural arts practices) and forms of cultural and community-based arts participation (e.g., experimental music, ritual, and street art) than previous definitions have included. It also does so by framing and by providing examples, rather than by describing arts participation as a static construct or by attempting to name or categorize all possible art forms and practices.

The resulting definition both aligns with and builds on the definitions offered by Davies et al. (2012) and the NEA (2019). Our definition combines the strengths of this previous work as it offers both modes and forms of arts participation. It also broadens these definitions by including socially engaged arts practices, including those that involve people in dialogue, collaboration, or interaction around local health, health equity, and well-being concerns, and that engage artists in partnering with communities to address these concerns. It also brings more attention to everyday and informal forms of creativity, such as reading for pleasure, gardening, and culinary arts than previous definitions. The inclusion of such activities as examples (rather than an exhaustive list) is helpful in ensuring that the definition is not limited to a static construct which may exclude practices that continue to evolve and that are distinct to various communities, particularly those that are historically excluded and underrepresented.

The definition recognizes that arts participation happens within many domains of human life, including within cultural traditions, artistic practices, and the creativity that occurs in everyday life. Within cultural traditions, people participate in arts and creative activities rooted in cultural heritage, identity, preservation, and celebration, including dance, music, storytelling, ritual, ceremony, and culinary arts practice (Canada Council for the Arts & Archipel Research and Consulting Inc., 2022; First Peoples Fund, 2022). Artistic practices may include performances, exhibits, workshops, classes, projects, creative groups, and individual or shared artmaking, as well as social, civic, and commercial practices that involve people and communities in dialogue, collaboration, celebration, expression, or interaction through the arts. Everyday creativity can include arts and creative activities as part of everyday life, including craft, gardening, reading for pleasure, singing, creative hobbies, and music listening. This definition recognizes that arts participation happens in many ways outside of these domains and may or may not involve the development of arts proficiency.

As arts in health practices and research seek to advance health equity (Burch, 2021; Epstein et al., 2021; Jackson, 2021), it is critical that a broad range of arts and cultural practices are included in definitions used in research. Notably, the World Health Organization (WHO, 2020) recommends the consideration of cultural factors in the development of inclusive health systems. Historically, however, many Indigenous and culture-based arts practices have been left out of arts in health research and are only more recently being incorporated into government tracked data about the arts (Iyengar, 2022). The definition proposed in this study adds to the discourse on arts in public health as it offers grounding and parameters to promote both cohesiveness and inclusivity in arts in public health research at both individual and community levels through an equitable lens. While there have been notable calls in the field to further mobilize the arts to promote health and health equity (Rodriguez et al., 2023), future research must continue to explore this broadening, as these forms of socially engaged art are an important part of the landscape of how the arts affect public health. This further emphasizes the need to continue the reevaluation and further development of such research in parallel with the evolution and broadening that continually takes place in arts and cultural practices.

Strengths and Limitations

The study had several strengths. It was able to build on work previously undertaken and was able to garner the input of field experts and the general public. The second survey had a high response rate (49%), suggesting strong interest in such a definition among field professionals. The survey also garnered opinions of members of the general public presumably unaffiliated with the arts in health field. The definition received very high levels of acceptability (8.88/10), alignment with how people understand the term “arts participation” (90% agreement), and the ways in which people participate in the arts (97% agreement). The mixed-methods approach allowed for quantitative data to be explained and corroborated by qualitative data. The dialogic analyses allowed for deep consideration and careful iteration of the definition by the research team.

That the study was undertaken during the pandemic may have been both a strength and a weakness. Previous studies have shown that more people participated in the arts during lockdown than prior, which may have heightened interest and participation in the study (Mak et al., 2022). It may also have influenced the breadth of what people consider to be an art form or practice, influencing the breadth of this definition.

The study had several limitations. One was that in the first two surveys, data were collected using convenience samples of people identified by the researchers. Similarly, the convenience sampling of the general public accessed via ResearchMatch represents a segment of the general population interested in participating in research conducted by medical institutions.

Lack of diversity among the field expert and general public groups is a major limitation of the study, with a disproportional majority of White and female participants. It is assumed that the low response rate among non-White groups likely reflects the historic and ongoing harm done to Black and Brown people by researchers in the United States, and the rightful reluctance to participate in research that persists among these groups (Jaiswal & Halkitis, 2019; Scharff et al., 2010). Future research must engage different means of surveying the general public to ensure a more diverse and representative sample.

The study may also have been limited by the lack of a standard definition for “arts” and by the interchangeable nature of engagement/participation in related research. Such issues are common in young, transdisciplinary areas of science, such as arts in health (Titler, 2018). In addition, given that the study was conducted to develop a working definition for the purposes of researching a specific initiative, it lacked an intention for generalizability. This definition is offered herein as a building block for future research and, as such, should be challenged and advanced through subsequent work.

Implications for Practice and/or Policy and Research

This work provides an important foundation for defining the concept of arts participation in public health practice, research, and policy. This definition has the potential to help advance the quality and precision of related research, particularly research aimed at evaluating relationships between arts participation and health, as well as outcomes of arts-based health programs and interventions in communities. This definition of arts participation can help guide the development of more inclusive search strategies for evidence synthesis in this rapidly growing arena and assist researchers in developing more effective survey questions and instruments.

This definition may have broader implications as well. In 2022, U.S. President Biden released an executive order on promoting the arts, humanities, museum, and library services in America, citing them as “essential to the well-being, health, vitality, and democracy of our Nation.” He asserted that,

Under my Administration, the arts, the humanities, and museum and library services will be integrated into strategies, policies, and programs that advance the economic development, well-being, and resilience of all communities, especially those that have historically been underserved. [They] will be promoted and expanded to strengthen public, physical, and mental health; wellness; and healing, including within military and veteran communities (Biden, 2022).

With such determination at the national level to advance utilization of the arts for health, well-being, and health equity, increased activity in related practice, policy, and research is likely, making this definition a timely contribution to the public health field.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-hpp-10.1177_15248399231183388 for Defining “Arts Participation” for Public Health Research by Jill Sonke, Alexandra K. Rodriguez, Aaron Colverson, Seher Akram, Nicole Morgan, Donna Hancox, Caroline Wagner-Jacobson and Virginia Pesata in Health Promotion Practice

Footnotes

Authors’ Note: We would like to acknowledge the contribution of Abel Abraham, Alexa Jaskiel, Francesca Leo, Stefany Marjani, Mariana Occhiuzzi, Ashley Quigley, the University of Florida’s Center for Arts in Medicine’s Interdisciplinary Research Laboratory, and Sunil Iyengar, director of the Office of Research & Analysis at the National Endowment for the Arts. In addition, funding for One Nation/One Project was provided by the Anne Clarke Wolff and Ted Wolff Foundation, Bloomberg Philanthropies, the Katie McGrath & J.J. Abrams Family Foundation, the Tow Foundation, the Sozosei Foundation, and the Eichholz Family Foundation. REDCap is supported by NCATS Grant UL1 TR000064.

ORCID iDs: Jill Sonke  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9232-793X

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9232-793X

Alexandra K. Rodriguez  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9254-3392

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9254-3392

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available at https://journals.sagepub.com/home/hpp.

References

- Biden J. (2022). Executive order on promoting the arts, humanities, museum, and library services in America. The White House. https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/presidential-actions/2022/09/30/executive-order-on-promoting-the-arts-the-humanities-and-museum-and-library-services/#:~:text=Under%20my%20Administration%2C%20the%20arts,that%20have%20historically%20been%20underserved. [Google Scholar]

- Bone J. K., Bu F., Fluharty M. E., Paul E., Sonke J. K., Fancourt D. (2021). Who engages in the arts in the United States? A comparison of several types of engagement using data from the General Social Survey. BMC Public Health, 21(1), 1–13. 10.1186/s12889-021-11263-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bone J. K., Fancourt D., Sonke J., Fluharty M., Cohen R., Lee J., Kolenic A. J., Radunovich H., Feifei BuBu F. (2022, August 2). Creative leisure activities, mental health, and wellbeing during five months of the COVID-19 pandemic: A fixed effects analysis of data from 3,725 US adults. 10.31234/osf.io/n76wj [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Braun V., Clarke V. (2019). Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 11(4), 589–597. 10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Burch S. R. (2021). Perspectives on racism: Reflections on our collective moral responsibility when leveraging arts and culture for health promotion. Health Promotion Practice, 22(Suppl. 1), 12S–16S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canada Council for the Arts & Archipel Research and Consulting Inc. (2022). Research on the value of public funding for indigenous arts and cultures (pp. 1–39). https://canadacouncil.ca/research/research-library/2022/09/research-on-public-funding-for-indigenous-arts-and-cultures

- Coulter A., Gordon-Nesbitt R. (2017). All party parliamentary group on arts, health and wellbeing. All-Party Parliamentary Group. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cousins E., Tischler V., Garabedian C., Dening T. (2020). A taxonomy of arts interventions for people with dementia. The Gerontologist, 60(1), 124–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creatives Rebuild New York. (2022). How CRNY defines “artist.” https://www.creativesrebuildny.org/how-crny-defines-artist/

- Davies C. R., Rosenberg M., Knuiman M., Ferguson R., Pikora T., Slatter N. (2012). Defining arts engagement for population-based health research: Art forms, activities and level of engagement. Arts & Health, 4(3), 203–216. 10.1080/17533015.2012.656201 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Engh R., Martin B., Laramee Kidd S., Gadwa Nicodemus A. (2021). WE-making: How arts & culture unite people to work toward community well-being. Metris Arts Consulting. [Google Scholar]

- Epstein R. N. E., Bluethenthal A., Visser D., Pinsky C., Minkler M. (2021). Leveraging Arts for Justice, Equity, and Public Health: The Skywatchers Program and Its Implications for Community-Based Health Promotion Practice and Research. Health Promotion Practice, 22(Suppl. 1), 91S–100S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fancourt D., Finn S. (2019). What is the evidence on the role of the arts in improving health and well-being? A scoping review (Health Evidence Network Synthesis Report No. 67; pp. 1–146). World Health Organization. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK553773/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fancourt D., Steptoe A. (2019). The art of life and death: 14 year follow-up analyses of associations between arts engagement and mortality in the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. BMJ, 367, Article l6377. 10.1136/bmj.l6377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Fetters M. D. (2020). The mixed methods research workbook: Activities for designing, implementing, and publishing projects. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 14(4), 548–549. 10.1177/1558689820943700 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- First Peoples Fund. (2022). Brightening the spotlight: The practices and needs of native American, native Hawaiian, and Alaska native creators in the performing arts (pp. 1–100). https://www.firstpeoplesfund.org/brightening-the-spotlight

- Galea S. (2021). The Arts and Public Health: Changing the Conversation on Health. Health Promotion Practice, 22(Suppl. 1), 8S–11S. 10.1177/1524839921996341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris P. A., Scott K. W., Lebo L., Hassan N., Lighter C., Pulley J. (2012). ResearchMatch: A national registry to recruit volunteers for clinical research. Academic Medicine: Journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges, 87(1), 66–73. 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31823ab7d2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iyengar S. (2022, November 3). Making space for Indigenous arts practices in government data about the arts. https://www.arts.gov/stories/blog/2022/making-space-indigenous-arts-practices-government-data-about-arts

- Iyengar S., Shewfelt S., Ivanchenko R., Menzer M., Shingler T. (2013). How a nation engages with art—Highlights from the 2012 survey of public participation in the arts. https://www.arts.gov/sites/default/files/highlights-from-2012-sppa-revised-oct-2015.pdf

- Jackson M. R. (2021). Addressing inequity through public health, community development, arts, and culture: Confluence of fields and the opportunity to reframe, retool, and repair. Health Promotion Practice, 22(Suppl. 1), 141S–146S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaiswal J., Halkitis P. N. (2019). Towards a more inclusive and dynamic understanding of medical mistrust informed by science. Behavioral Medicine, 45(2), 79–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mak H. W., Bu F., Fancourt D. (2022). Comparisons of home-based arts engagement across three national lockdowns during the COVID-19 pandemic in England. PLOS ONE, 17(8), Article e0273829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matusov E., Marjanovic-Shane A., Kullenberg T., Curtis K. (2019). Dialogic analysis vs. discourse analysis of dialogic pedagogy: Social science research in the era of positivism and post-truth. Dialogic Pedagogy: An International Online Journal, 7, E20–E62. [Google Scholar]

- National Endowment for the Arts. (2019). U.S. patterns of arts participation: A full report from the 2017 survey of public participation in the arts. https://www.arts.gov/sites/default/files/US_Patterns_of_Arts_ParticipationRevised.pdf

- National Opinion Research Center. (2021). The outcomes of arts engagement for individuals and communities. University of Chicago. https://www.norc.org/PDFs/The%20Outcomes%20of%20Arts%20Engagement%20for%20Individuals%20and%20Communities/NORC%20Outcomes%20of%20Arts%20Engagement%20-%20Full%20Report.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Novak-Leonard J. L., Brown A. S. (2011). Beyond attendance: A multi-modal understanding of arts participation. National Endowment for the Arts. https://www.arts.gov/sites/default/files/2008-SPPA-BeyondAttendance.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Parkinson C. (2018). Weapons of mass happiness: Social justice and health equity in the context of the arts. In Sunderland N., Lewandowski N., Bendrups D., Bartleet B. L. (Eds.), Music, Health and Wellbeing: Exploring Music for Health Equity and Social Justice (pp. 269–288). Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Raw A., Lewis S., Russell A., Macnaughton J. (2012). A hole in the heart: Confronting the drive for evidence-based impact research in arts and health. Arts & Health, 4(2), 97–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rena M., Fancourt D., Bu F., Paul E., Sonke J., Bone J. K. (2022, August 30). Receptive and participatory arts engagement and healthy aging: Longitudinal evidence from the health and retirement study. 10.31234/osf.io/q4h6y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez A. K., Akram S., Colverson A., Hack G., Sonke J. (2023). Arts engagement as a health behavior: An opportunity to address mental health inequities Community Health Equity Research & Policy, 0(0). Advance online publication. 10.1177/2752535X231175072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scharff D. P., Mathews K. J., Jackson P., Hoffsuemmer J., Martin E., Edwards D. (2010). More than Tuskegee: Understanding mistrust about research participation. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 21(3), 879–897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Titler M. G. (2018). Translation research in practice: An introduction. OJIN: The Online Journal of Issues in Nursing, 23(2), Article 1. 10.3912/OJIN.Vol23No02Man01 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Van Styvendale N., McDougall J. D., Henry R., Innes R. A. (Eds.) (2021). The arts of Indigenous health and well-being. University of Manitoba Press. [Google Scholar]

- Windsor J. (2005). Your health and the arts: A study of the association between arts engagement and health. Arts Council England. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2020). WHO recommends considering cultural factors to develop more inclusive health systems. https://www.who.int/news-room/feature-stories/detail/who-recommends-considering-cultural-factors-to-develop-more-inclusive-health-systems

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-hpp-10.1177_15248399231183388 for Defining “Arts Participation” for Public Health Research by Jill Sonke, Alexandra K. Rodriguez, Aaron Colverson, Seher Akram, Nicole Morgan, Donna Hancox, Caroline Wagner-Jacobson and Virginia Pesata in Health Promotion Practice