Abstract

Lung health, the development of lung disease, and how well a person with lung disease is able to live all depend on a wide range of societal factors. These systemic factors that adversely affect people and cause injustice can be thought of as “structural violence.” To make the causal processes relating to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) more apparent, and the responsibility to interrupt or alleviate them clearer, we have developed a taxonomy to describe this. It contains five domains: 1) avoidable lung harms (processes impacting lung development, processes that disadvantage lung health in particular groups across the life course), 2) diagnostic delay (healthcare factors; norms and attitudes that mean COPD is not diagnosed in a timely way, denying people with COPD effective treatment), 3) inadequate COPD care (ways in which the provision of care for people with COPD falls short of what is needed to ensure they are able to enjoy the best possible health, considered as healthcare resource allocation and norms and attitudes influencing clinical practice), 4) low status of COPD (ways COPD as a condition and people with COPD are held in less regard and considered less of a priority than other comparable health problems), and 5) lack of support (factors that make living with COPD more difficult than it should be, i.e., socioenvironmental factors and factors that promote social isolation). This model has relevance for policymakers, healthcare professionals, and the public as an educational resource to change clinical practices and priorities and stimulate advocacy and activism with the goal of the elimination of COPD.

Keywords: epidemiology, advocacy, stigma, healthcare provision, inequality

At a Glance Commentary

Scientific Knowledge on the Subject

Healthcare systems and healthcare professionals tend to view health conditions as something that people “have.” However, lung disease, as exemplified by chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), can also usefully be represented as something that has been “done to” people. By framing it in this way, the causal processes driving social injustice become more apparent, and, with that, the need for means by which clinicians and others can interrupt or alleviate these mechanisms becomes clearer.

What This Study Adds to the Field

The model we have codeveloped defines five domains whereby structural processes cause or aggravate COPD: avoidable lung harms, diagnostic delay, inadequate COPD care, low status of COPD, and lack of support for people living with COPD. This model has relevance for policymakers, healthcare professionals, and the public as an education resource to change clinical practices and priorities and stimulate advocacy and activism for social justice and reparations.

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is one of the leading causes of disability and premature death (1). The link between socioeconomic deprivation and health status is undeniable, and, like all long-term health conditions, COPD is not distributed equally within and between populations (2, 3). Healthcare systems and healthcare professionals tend to view health conditions as something that people “have.” In this paper, we argue that lung disease, as exemplified by COPD, can also usefully be represented as something that has been “done to” people. By framing it in this way, the causal processes driving social injustice become more apparent, and, with that, the need for means by which clinicians and others can interrupt or alleviate these mechanisms becomes clearer.

To understand the processes that underpin systemic injustice, Johan Galtung introduced the term “structural violence” in 1969. This can help us to understand that, in addition to the more obvious consequences of direct violence whereby individuals are directly harmed by physical means, violence is also “built into the structure and shows up in unequal power and consequently as unequal life chances” (4). This is analogous to Stokely Carmichael’s distinction between two types of racism: individual racism and institutional racism (5). The absence of direct violence is peace, and the absence of structural violence would be social justice (4). A key consideration is to focus on factors that limit life experiences that are actually possible to achieve. For example, aging is inevitable, but the circumstances and manner in which we age vary enormously, impacting individual well-being and indeed the possibility of living a life of adequate length.

The use of the term “structural violence,” which is more direct than usual discourse while also unfamiliar but easily understood, is intended to focus attention on the way in which structural factors in societies cause people to develop COPD who need not have done so and disadvantage people who have COPD so that their lives are more limited than they could be. Focus on these is needed to develop strategies and solutions to reduce or eliminate the burden of COPD. The approach relates closely to the social conditions as fundamental causes of health inequalities theory (6), which posits that inequalities persist because socioeconomic status continues to embody an array of resources, such as money, knowledge, prestige, power, and beneficial social connections that protect health.

We therefore aimed to develop a taxonomy of structural violence, using an iterative process to refine the structural social factors that bear on COPD, on which people working in this field can build to guide research, advocacy, and reform. It should also help to identify and encourage areas for interdisciplinary work between the medical and social sciences. Some of the results of these studies have been previously reported in the form of a preprint (7).

Model Development

The model development followed a partnership-based approach, with collaboration among the research team, experts in various aspects of adult and pediatric lung health, and people affected by COPD. It was informed by the first three components of the Six Steps in Quality Development framework: 1) defining and understanding the problem and its causes; 2) identifying which causal or contextual factors are modifiable, i.e., which have the greatest scope for change and who would benefit most; and 3) deciding on the mechanisms of change (8).

Following informal discussions with respiratory experts and considering responses to Asthma + Lung UK surveys of people with respiratory disease (9, 10), the authors proposed an initial model containing five domains of concern: avoidable risks that cause COPD, diagnostic delay, inadequate COPD care, low status of COPD, and the lack of support that people living with COPD experience (11). These categories were then circulated online to an expert panel using SurveyMonkey (Momentive Inc) to canvas opinions about the validity of this structure, as well as to rate the importance of key elements that should be contained in each domain and suggest additional ones. Expert input through this process led to an increased emphasis on early life and transgenerational factors as well as the impact of racism.

The survey was also sent to members of an Asthma + Lung UK patient group who ranked elements to confirm their importance and were able to offer additional possible items. This led to an increased emphasis on the impact of stigma from the public and healthcare system as well as demands for legislation to tackle avoidable lung harms such as poverty and air pollution. Further stakeholder meetings were held to review and refine the model and evidence base, allowing a deeper discussion about key concepts. See online supplement for details of the development process.

Where mechanisms are described in the model, they are, in general, cited only once, in what was deemed to be the most relevant domain based on an assessment of impact or causal priority. For example, poor housing is a risk factor for the development of lung disease but also makes living with lung disease more difficult.

A Conceptual Model of COPD as a Manifestation of Structural Violence

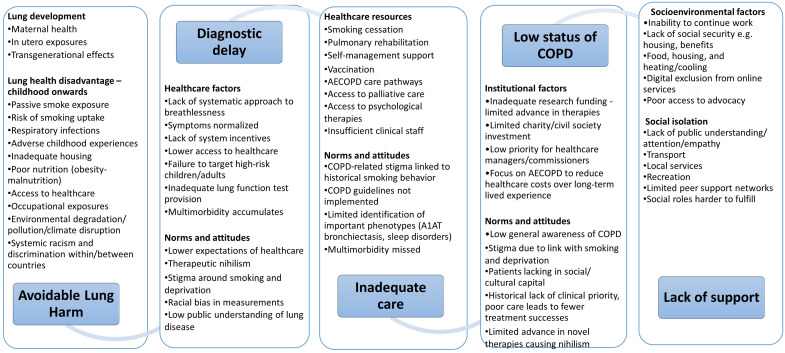

The final model included the following five domains, each consisting of two subdomains (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease as a locus for structural violence. AECOPD = acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Avoidable lung harms: 1) processes that impact on lung development and 2) processes that disadvantage lung health in particular groups across the life course.

Diagnostic delay: 1) healthcare factors and 2) norms and attitudes that mean that COPD is not diagnosed in a timely way, denying people with COPD effective treatment to improve or maintain their quality of life and improve prognoses.

Inadequate COPD care: ways in which the provision of care for people with COPD falls short of what is needed to ensure they are able to enjoy the best possible health, considered as 1) healthcare resource allocation and 2) norms and attitudes influencing clinical practice.

Low status of COPD: ways in which COPD as a condition and people with COPD are held in less regard and considered less of a priority than other health problems of similar scale, considered as 1) institutional factors and 2) norms and attitudes.

Lack of support: factors that make living with COPD more difficult than it should be. These are categorized as 1) socioenvironmental factors and 2) factors that promote social isolation.

Avoidable Lung Harms

The lung pathology that underpins COPD—airway inflammation and remodeling, bronchiolitis, alveolar destruction, and pulmonary vascular damage—occurs first, because of factors that interfere with lung growth before and after birth and across generations (3, 12, 13). An adverse fetal environment produces lung structural changes, altered immunology, low birth weight and prematurity, sensitization to later insults, and premature aging (telomere shortening) (14), as well as increasing cardiovascular risk driving multimorbidity (15). The second main factor is exposures and processes that accelerate lung function decline across the life course, including second-hand smoke exposure, diet, smoking, air pollution, and occupation (1, 12, 16–23).

COPD is closely tied to inequality and deprivation (2, 14) and, in particular, failure to ensure the health and well-being of mothers and children (24). As Michael Marmot has observed, “child poverty is a political choice” (25). Absolute and relative poverty reduction (26, 27), tackling corporate determinants of health like the relative expense of healthy diets versus poor ones (28) and the promotion of alcohol (29), addressing neighborhood and partner violence (30), structured early-years support such as the U.S. Head Start (31) or U.K. SureStart schemes (32), policies that reduce workplace stress and occupational exposures (33, 34), as well as reducing indoor and outdoor air pollution (15, 35) and implementing comprehensive tobacco control measures (36) would all decrease the avoidable harm done to children’s lungs and thus reduce their risk of developing COPD in later life.

U.S. data show that the Neighborhood Environmental Vulnerability Index, which captures domains pertaining to demographic characteristics, economic indicators, residential characteristics, and health status characteristics, is associated with respiratory hospitalization in children (37), as is the neighborhood Child Opportunity Index (38), with evidence linking the Child Opportunity Index to a range of respiratory outcomes including asthma risk, the fitness of children with asthma, and exposure to triggers for developing or worsening lung disease (39–41), and the Area Deprivation Index is associated with an increased risk of hospitalization in children with bronchopulmonary dysplasia (42).

Most of the structural factors that drive lung health disadvantage in early life continue to operate across the life course. Failure to address smoking at the time of delivery increases children’s exposure to environmental tobacco smoke, and smoking behavior is passed on to children by carers and peer groups (43), sustaining health inequality. Smoking is the leading preventable cause of premature death and disability, responsible for half the difference in life expectancy between rich and poor (44), and two thirds of people who continue to smoke will die from a smoking-related disease (45, 46). Childhood smoking uptake substantially increases the risk of lung disease (47). There has been a failure to take action proportionate to this knowledge. In the United Kingdom, for example, there was a 36-year gap between the 1962 publication of Smoking Kills by the Royal College of Physicians and the first comprehensive government tobacco control plan in 1998. Smoking rates in U.K. 15-year-olds decreased from 20% to 3% in the following 20 years after having been unchanged at that level for the previous 20 years. A similar lag in policy implementation followed the U.S. Surgeon General’s 1964 report on the same subject (48). There is no technical reason why effective measures to reduce the affordability, availability, and appeal of smoking could not have been taken earlier, and the responsibility for millions of children taking up smoking rests with adult policymakers. Globally, although there has been progress since the World Health Organization Framework Convention on Tobacco Control treaty was instituted, virtually no country has chosen to implement the full range of measures needed to achieve its objectives (36, 49).

As with smoking, efforts to prevent youth uptake of vaping by reducing its affordability, availability, and appeal to nonsmokers continue to be inadequate to the task (50).

The use of illicit drugs, both inhaled and intravenous, is another cause of COPD that is determined by modifiable social factors and amenable to poverty reduction and other social interventions (51).

Respiratory infections in early childhood are associated with an increased risk of death from respiratory causes such as COPD in adult life (52), and tuberculosis is also an important and socially determined cause of COPD (15). Modifiable factors that increase the risk of childhood respiratory infections and their severity include poor housing and nutrition, reduced access to health care, smoking, and exposure to indoor and outdoor air pollution.

Occupations in which workers are exposed to dust, fumes, and chemicals increase the risk of developing obstructive lung disease, and the population-attributable fractions due to occupation are estimated to be 14% for COPD and 16% for asthma (15, 32). Structural issues here include the lower socioeconomic status of people performing factory and cleaning work and decisions about whether to provide workers with appropriate protection.

Global heating, climate disruption, and air pollution cause COPD through a range of synergistic mechanisms, including increased lung toxicity from particulates and nitrogen oxide, as well as increased allergen exposure driving asthma incidence (53, 54). Exposure to pollution is itself tightly linked to poverty (55) and an issue of environmental justice (56). Active transport and clean public transportation reduce air pollution, and physical inactivity is associated with accelerated lung function decline, so a failure to facilitate and promote physical activity is also a systemic risk (57).

Diagnostic Delay

The diagnostic criteria for COPD are straightforward, but the condition is typically diagnosed when there is already substantial lung damage and often when there have been suggestive symptoms for several years, meaning that patients miss out on interventions that could improve their quality of life, delay disease progression, and improve survival (58–61). Healthcare factors include a lack of a systematic approach to breathlessness in midlife, with symptoms normalized as an expected consequence of aging or a “smoker’s cough” (59, 62). Allowing slowly progressive breathlessness to restrict daily physical activity levels may also promote multimorbidity because sedentarism increases the risk of other long-term conditions such as diabetes, hypertension, and osteoporosis (57, 63). There is typically a lack of system incentives to identify COPD, lung function testing provision is poor, and bias in measurement may systematically underdiagnose lung disease in some ethnic groups (22, 64). High-risk groups such as those with a history of childhood chest disease, those with occupations associated with inhaled exposures or high smoking rates, those with mental health problems, and unhoused people are likely to be groups that also have less access to health care and lower expectations of health care (65, 66).

There is generally poor awareness of COPD and lung disease, and there has been a lack of strategies to communicate this and change health behavior (67). People with symptoms may consider them self-inflicted, worry about stigma, or worry that the symptoms represent cancer. Therapeutic nihilism and stigma around COPD produce a self-fulfilling failure to make the diagnosis (68, 69).

Inadequate Care

COPD management aims to improve shortness of breath and other symptoms, reduce disease progression, and improve the prognosis (24, 70). The United Kingdom’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence has defined “five fundamentals of COPD care”: smoking cessation, vaccination, pulmonary rehabilitation, personalized self-management plans, and optimizing treatment for multimorbidity (70). However, most people with COPD are currently denied effective treatment, in both low and high-income countries (8, 71–73). Limited time and resources mean that basics like guidance on inhaler technique are not delivered. An insufficient respiratory workforce (60) and the move away from specialist respiratory care can also mean that treatable phenotypes such as bronchiectasis, sleep-disordered breathing, and pulmonary hypertension may go unidentified and untreated. The acceptance of symptoms as normal or untreatable also means that multimorbidity including cardiac disease, lung cancer, and mental health problems go underdiagnosed and undertreated (10). Referral for specialist intervention like lung volume reduction procedures often occurs too late, if it is considered at all (74). Despite a high symptom burden, COPD patient access to palliative care is limited (75, 76), as is access to treatment for psychological comorbidities (77). Care pathways do not systematize universal engagement with charities that could support patients (60).

Globally, the majority of people with COPD are among the lowest-income people in low-income countries and do not have access to affordable medication (78). This contributes to patients missing out on effective treatment in low-resource settings (79, 80). Access to smoking-cessation pharmacotherapy is also limited (81), and research and development focus on high-income countries.

The explanations for poor care can be found in an interplay between healthcare system choices about prioritization and norms and attitudes of healthcare workers and patients (82, 83), which drive a mutually reinforcing therapeutic nihilism (24). Training of healthcare providers and professionals in implicit bias and cultural competency may help to address issues that arise related to minoritized groups.

Low Status of COPD

In 2019, there were estimated to be 212 million people diagnosed with COPD globally, and COPD accounted for 3.3 million deaths (1). Given its impacts on healthcare systems and the lives of individual citizens, COPD receives proportionately less attention and investment in clinical care and research than would be expected (60, 84). This is matched by a lack of public awareness of COPD as a health condition (85, 86). Respiratory disease is often omitted from healthcare policy discussion, even when it is highly relevant (87). Choices about which conditions to link to performance targets have impacted COPD care. In the United Kingdom, for example, National Service Frameworks—10-year plans to achieve performance targets for conditions such as cancer, coronary heart disease and stroke, accidents, and mental health—were introduced around the turn of the 21st century. The omission of respiratory disease from these has inevitably led to a diversion of resources and attention toward the conditions that were prioritized.

In addition, meager allocation of research funds has translated into a lack of progress in understanding COPD and developing new treatments, and this lack of progress has deterred further investment (88). The low status of COPD clinical care also makes COPD research more difficult, as the starting point of a well-phenotyped patient receiving established standard care is less accessible than, for example, a person with coronary artery disease, for which treatment is typically highly protocolized and relatively well resourced.

The socioeconomic distribution of COPD means that people with the condition lack social and cultural capital, which impacts how they are perceived by healthcare professionals. Stigma is an important aspect of living with COPD that feeds into the low priority that the condition and people with it are given (68, 69, 83).

Care pathways for acute exacerbations of COPD have changed little in recent decades, in stark contrast to the treatment of myocardial infarction and stroke. Although mortality and readmission rates after hospitalization for acute exacerbations of COPD are high, acceptance of this as a normal aspect of COPD means postdischarge support and investigation are typically limited (89).

Lack of Support for Living with COPD

The experience of having COPD is influenced for the worse by factors that make living with the condition more difficult. COPD is more common in poorer people and increases the likelihood that people will have to give up work prematurely, reducing their income and savings (90). Lack of money, poor housing, and absence of transportation deny people with COPD the chance to mitigate some of the limitations caused by the disease, and living in a cold, damp home increases the risk of acute exacerbations (91). Choices about welfare such as disability benefits, and public provision of resources such as public transportation, libraries, and recreation centers will influence the constraints under which poorer individuals with COPD live (25). Older people with COPD may lack digital access or literacy, so digital-by-default services become inaccessible (92).

Stigma and a lack of public understanding make living with COPD more difficult. Related to but distinct from the more quantitative domain of social welfare are factors that determine the experience of social isolation and loneliness, including limited peer support networks and an inability to fulfill social roles such as grandparenting and participation in social activities and recreation (93).

Mitigating Structural Violence: Scope and Scale

Having set out the mechanisms through which structural processes manifest in COPD, the question arises: what should be done about them? For healthcare professionals, these can be considered in terms of what can be addressed by making systematic improvements to clinical practice, by advocacy, and by healthcare professionals collectively through representative bodies such as thoracic societies (Table 1).

Table 1.

Responsibility to Address Structural Processes Related to COPD

| Responsible Group | Measures to Address Structural Violence Around COPD |

|---|---|

| Policymakers |

|

| The public |

|

| People with COPD |

|

| Healthcare professionals as individuals |

|

Definition of abbreviations: COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; NGO = nongovernmental organization.

COPD and Legal Considerations

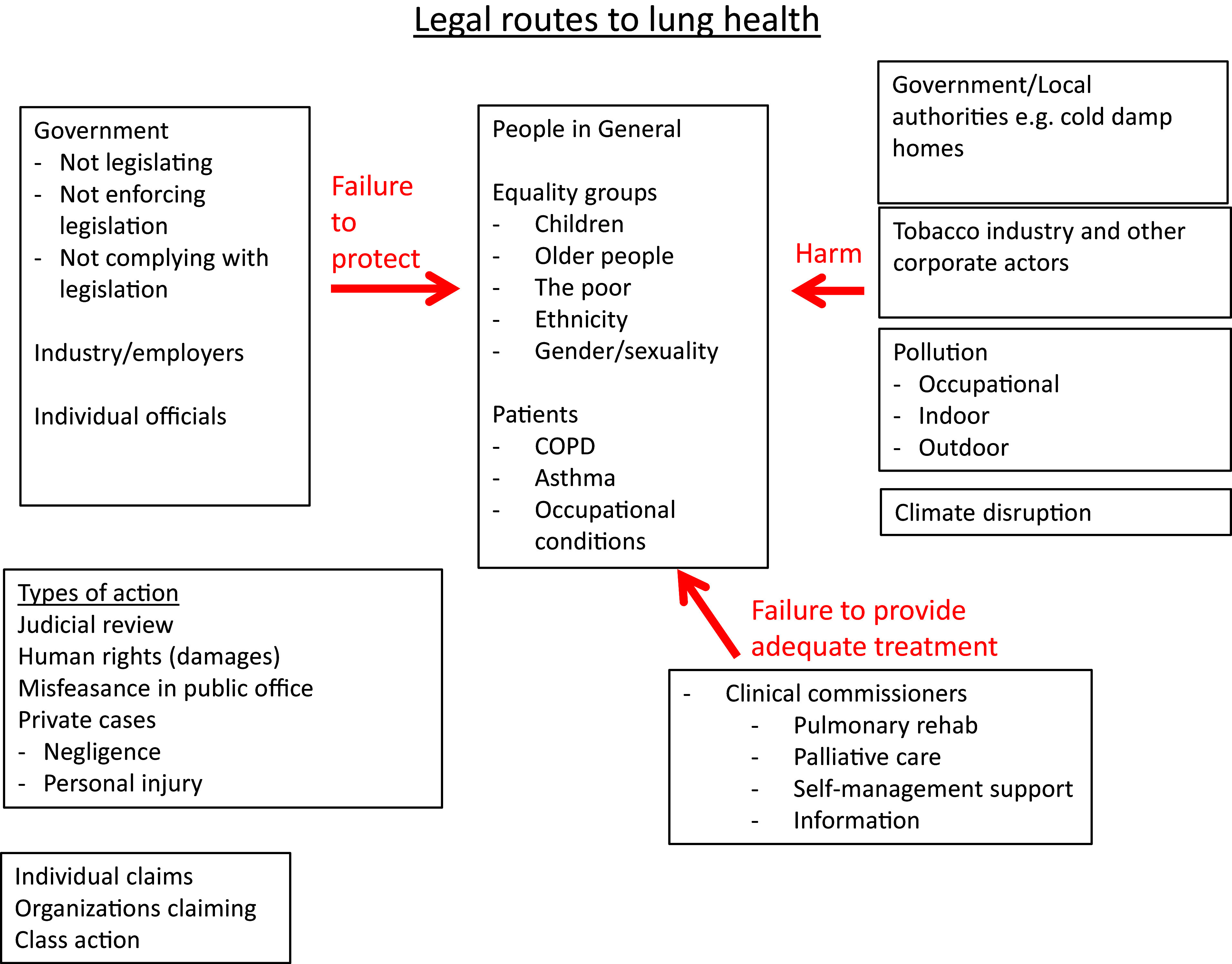

A person with lung disease may have been the victim of one of three broad types of injustice with possible legal remedies (Figure 2). First, an individual or entity may have harmed them directly by exposing them to noxious materials. The tobacco industry is the obvious example, but other polluters or occupational exposures are also relevant. The second broad possibility is that an individual or entity with a duty to protect them from harm has failed to do so. In the case of government, this could represent a failure to legislate, to comply with legislation, or to enforce legislation. Examples include inaction on air quality and failure to restrain the harm caused by the tobacco industry (36). The third potential injustice is the failure to provide effective treatments or the means to access them. Inadequate provision of the five fundamentals of COPD care, including pulmonary rehabilitation and smoking-cessation services, is an example of this (70).

Figure 2.

Legal routes to lung health. COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

The practical implications of this will vary from country to country depending on legal systems, but potential approaches depend on the entity considered to be at fault. There may also be specific issues in which the group affected comes from a designated group or minority. For government or quasi-governmental bodies, judicial review and human rights–based approaches might be considered. Private actions for negligence or personal injury may be appropriate in some situations, and possible claims might be from individuals or class actions. Exemplary cases may prompt action. In 2020, Ella Kissi-Debra, a 9-year-old girl who died in 2013, became the first person in the world to have air pollution given as a cause of death. Her case has been a spur to expand London’s Ultra Low Emission Zone, which is intended to restrict the most polluting vehicles from driving in the city. Table E5 in the online supplement comprehensively details the evidence for harms related to each domain and potential mitigation.

Discussion

The model described in this work was developed through an iterative process involving a range of experts and people with COPD. Its five domains provide a systematic approach to considering the factors that cause people to develop COPD and to live lives that are limited in terms of well-being and agency: the extent to which they are able to pursue goals and objectives they have reason to value. The model should help guide advocacy, modify clinical priorities and practice, and be a stimulus to activism for people with COPD and those who care about them.

Within each domain, we set out the key processes in play, presenting salient examples and potential strategies for mitigation. The model is intended to serve as a starting point; achieving social justice through the elimination of structural violence requires action at a range of scales.

In three of the five domains, we identified a subset of structural factors that could be defined as representing “norms and attitudes.” Although these are, to a great extent, culturally and institutionally determined, they nevertheless are likely to be the most amenable to individual, smaller-scale, and local action by healthcare professionals.

Potential action ranges from steps taken to ensure that health literacy is addressed and systematic encouragement given to engage with health charities and patient-advocacy organizations, as well as nonprofit groups and community stakeholders in individual patient consultations, through decisions to provide an appropriate proportion of healthcare resources to the needs of people with COPD, up to societal choices to reduce or eliminate poverty and inequality.

Much of the literature in this field comes from high-income countries, which itself is a manifestation of structural injustice (94), even though most of the items discussed are likely to apply across different countries, and we have used examples from a range of regions. The persistence of structural factors that cause and worsen COPD in wealthy countries with well-developed healthcare systems is striking, even though the very existence of low-income countries can be considered to represent injustice and structural violence on a much greater scale.

A key underpinning element of structural violence is the impact of anthropogenic global heating. This will increase the occurrence of lung disease, make living with lung disease more difficult, and reduce the resilience of societies in general and healthcare systems specifically. The fact that the countries and people most vulnerable to the effects of climate disruption are precisely those least responsible for it should be a readily accessible analogy for the processes addressed in this paper: people with COPD and their families are typically from the social groups that are least likely to dictate laws or determine the behavior of corporations.

Like any model, the five domains of structural violence and the elements they contain may be subject to revision. We believe the categories identified by our consensus process will prove useful, and they are also intended to be as unobtrusive as possible so that the content rather than the classification is the focus.

A criticism of this model is that it displaces concepts of personal responsibility and agency. Do people who make bad choices deserve to experience bad outcomes? There are a number of arguments against this. First, the approaches are not mutually exclusive (95). People can be taken to be free to choose within the situation in which they find themselves, but the point of structural violence as a concept is precisely that the range of choices available to an individual is limited by the structural processes we describe here. Second, individual choice is of no relevance to processes acting in early life and before birth: welfare policies that have the intent of chastening the “undeserving” poor have the consequence of blighting the lives of the innocent unborn. In particular, choice is of limited relevance to smoking, which is driven for most people by an addiction starting in childhood, and, as such, is better thought of as a failure—since the 1950s, when the harms became incontrovertible—of adults to protect children (96).

There are other economic arguments that addressing structural violence is a general good: investment in public health is likely to improve economic performance, a general benefit that goes beyond just those who are prevented from developing COPD or where the impact of the condition is reduced (97). Many of the interventions that would reduce the incidence of COPD would also reduce other long-term conditions and improve the general population’s experience of fairness and other aspects of quality of life.

In addition to the examples in the main text, a more comprehensive selection from the literature is provided in the online supplement. We hope people in different countries will take the model presented as a stimulus to consider how these issues manifest in their own contexts and internationally.

Conclusions

As Virchow famously asserted, “Medicine is a social science and politics is nothing else but medicine on a large scale. Medicine as a social science, as the science of human beings, has the obligation to point out problems and to attempt their theoretical solution.” The model developed and presented in this paper highlights how COPD is a manifestation of structural processes in society and argues that, rather than observing COPD as something people have done to themselves, we should view it as something that has been and continues to be done to them. This model has relevance for policymakers, healthcare professionals, and the public as an education resource to change clinical practices and priorities and to stimulate advocacy and activism for social justice and reparations.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgment

The authors thank the people with COPD who participated in the project for their support, input, and insight; and the following clinical and academic colleagues for their suggestions and help in the development process: Professor Mona Bafadhel, King’s College London; Professor Andrew Bush, Imperial College London; Professor James Dodd, University of Bristol; Rachael Evans, University of Leicester; Professor John Hurst, University College, London; Ms Rasleen Kahai, Royal Brompton and Harefield Hospitals; Dr Anu Kumar, NHS City & Hackney Clinical Commissioning Group; Professor Keir Lewis, Hywel Dda University Health Board; Professor John Moxham, King’s College London; Professor Najib Rahman, Oxford University; Dr Victoria Singh, Royal Brompton and Harefield Hospitals; Dr Ian Sinha, University of Liverpool; Dr Laura-Jane Smith, King’s College London; Dr Paul Walker, British Thoracic Society/University of Liverpool; Dr Andrew Whittamore, Clinical Director Asthma + Lung UK; and Ms Sarah Woolnough, Chief Executive Asthma + Lung UK.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: The initial model was developed by P.J.W., S.C.B., A.A.L., and N.S.H. The collection and collation of stakeholder input was conducted by P.J.W. and N.S.H. wrote the first draft, to which all authors contributed and approved the final version.

This article has an online supplement, which is accessible from this issue’s table of contents at www.atsjournals.org.

CME will be available for this article at https://shop.thoracic.org/collections/cme-moc/ethos-format-type-journal.

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1164/rccm.202309-1650CI on February 1, 2024

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1. Safiri S, Carson-Chahhoud K, Noori M, Nejadghaderi SA, Sullman MJM, Ahmadian Heris J, et al. Burden of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and its attributable risk factors in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: results from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. BMJ . 2022;378:e069679. doi: 10.1136/bmj-2021-069679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Burney P. Chronic respiratory disease – the acceptable epidemic? Clin Med (Lond) . 2017;17:29–32. doi: 10.7861/clinmedicine.17-1-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Stolz D, Mkorombindo T, Schumann DM, Agusti A, Ash SY, Bafadhel M, et al. Towards the elimination of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a Lancet Commission. Lancet . 2022;400:921–972. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01273-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Galtung J. Violence, peace, and peace research. J Peace Res . 1969;6:167–191. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carmichael S.Cooper D. Carmichael S. Laing RD. Marcuse H. Goodman P. The dialectics of liberation (radical thinkers) London: Verso Books; 1968. Black power; p. 151. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Phelan JC, Link BG, Tehranifar P. Social conditions as fundamental causes of health inequalities: theory, evidence, and policy implications. J Health Soc Behav . 2010;51:S28–S40. doi: 10.1177/0022146510383498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Williams PJ, Buttery SC, Laverty AA, Hopkinson NS.Being responsible for COPD - lung disease as a manifestation of structural violence. 2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8. Wight D, Wimbush E, Jepson R, Doi L. Six steps in quality intervention development (6SQuID) J Epidemiol Community Health . 2016;70:520–525. doi: 10.1136/jech-2015-205952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Philip K, Gaduzo S, Rogers J, Laffan M, Hopkinson NS. Patient experience of COPD care: outcomes from the British Lung Foundation Patient Passport. BMJ Open Respir Res . 2019;6:e000478. doi: 10.1136/bmjresp-2019-000478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Buttery S, Philip KEJ, Williams P, Fallas A, West B, Cumella A, et al. Patient symptoms and experience following COVID-19: results from a UK-wide survey. BMJ Open Respir Res . 2021;8:e001075. doi: 10.1136/bmjresp-2021-001075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Buttery SC, Zysman M, Vikjord SAA, Hopkinson NS, Jenkins C, Vanfleteren LEGW. Contemporary perspectives in COPD: patient burden, the role of gender and trajectories of multimorbidity. Respirology . 2021;26:419–441. doi: 10.1111/resp.14150_842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wang G, Hallberg J, Faner R, Koefoed HJ, Kebede Merid S, Klevebro S, et al. Plasticity of individual lung function states from childhood to adulthood. Am J Respir Crit Care Med . 2023;207:406–415. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202203-0444OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Magnus MC, Håberg SE, Karlstad Ø, Nafstad P, London SJ, Nystad W. Grandmother’s smoking when pregnant with the mother and asthma in the grandchild: the Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort Study. Thorax . 2015;70:237–243. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2014-206438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bush A. Impact of early life exposures on respiratory disease. Paediatr Respir Rev . 2021;40:24–32. doi: 10.1016/j.prrv.2021.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Limperopoulos C, Wessel DL, du Plessis AJ. Understanding the maternal-fetal environment and the birth of prenatal pediatrics. J Am Heart Assoc . 2022;11:e023807. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.121.023807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Yang IA, Jenkins CR, Salvi SS. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in never-smokers: risk factors, pathogenesis, and implications for prevention and treatment. Lancet Respir Med . 2022;10:497–511. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(21)00506-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Peters A, Nawrot TS, Baccarelli AA. Hallmarks of environmental insults. Cell . 2021;184:1455–1468. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.01.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bui DS, Agusti A, Walters H, Lodge C, Perret JL, Lowe A, et al. Lung function trajectory and biomarkers in the Tasmanian Longitudinal Health Study. ERJ Open Res . 2021;7:00020-2021. doi: 10.1183/23120541.00020-2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bui DS, Lodge CJ, Burgess JA, Lowe AJ, Perret J, Bui MQ, et al. Childhood predictors of lung function trajectories and future COPD risk: a prospective cohort study from the first to the sixth decade of life. Lancet Respir Med . 2018;6:535–544. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(18)30100-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Okyere DO, Bui DS, Washko GR, Lodge CJ, Lowe AJ, Cassim R, et al. Predictors of lung function trajectories in population-based studies: a systematic review. Respirology . 2021;26:938–959. doi: 10.1111/resp.14142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ubags NDJ, Alejandre Alcazar MA, Kallapur SG, Knapp S, Lanone S, Lloyd CM, et al. Early origins of lung disease: towards an interdisciplinary approach. Eur Respir Rev . 2020;29:200191. doi: 10.1183/16000617.0191-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Beijers RJHCG, Steiner MC, Schols AMWJ. The role of diet and nutrition in the management of COPD. Eur Respir Rev . 2023;32:230003. doi: 10.1183/16000617.0003-2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gheissari R, Liao J, Garcia E, Pavlovic N, Gilliland FD, Xiang AH, et al. Health outcomes in children associated with prenatal and early-life exposures to air pollution: a narrative review. Toxics . 2022;10:458. doi: 10.3390/toxics10080458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hopkinson NS, Lenney W, Langton-Hewer S, Bennett J, Swingwood E, Hughes A, et al. Children’s charter for lung health. Thorax . 2022;77:11–12. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2021-217766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Zoumot Z, Jordan S, Hopkinson NS. Emphysema: time to say farewell to therapeutic nihilism. Thorax . 2014;69:973–975. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2014-205667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Gibson M, Hearty W, Craig P. The public health effects of interventions similar to basic income: a scoping review. Lancet Public Health . 2020;5:e165–e176. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30005-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Patel JH, Amaral AFS, Minelli C, Elfadaly FG, Mortimer K, Sony AE, et al. Chronic airflow obstruction attributable to poverty in the multinational Burden of Obstructive Lung Disease (BOLD) study. Thorax . 2023;78:942–945. doi: 10.1136/thorax-2022-218668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Varraso R, Chiuve SE, Fung TT, Barr RG, Hu FB, Willett WC, et al. Alternate Healthy Eating Index 2010 and risk of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease among US women and men: prospective study. BMJ . 2015;350:h286. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gilmore AB, Fabbri A, Baum F, Bertscher A, Bondy K, Chang H-J, et al. Defining and conceptualising the commercial determinants of health. Lancet . 2023;401:1194–1213. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(23)00013-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bailey BA. Partner violence during pregnancy: prevalence, effects, screening, and management. Int J Womens Health . 2010;2:183–197. doi: 10.2147/ijwh.s8632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Deming D. Early childhood intervention and life-cycle skill development: evidence from Head Start. Am Econ J Appl Econ . 2009;1:111–134. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Melhuish E, Belsky J, Barnes J. Evaluation and value of Sure Start. Arch Dis Child . 2010;95:159–161. doi: 10.1136/adc.2009.161018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. De Matteis S, Jarvis D, Darnton L, Consonni D, Kromhout H, Hutchings S, et al. Lifetime occupational exposures and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease risk in the UK Biobank cohort. Thorax . 2022;77:997–1005. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2020-216523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Blanc PD, Annesi-Maesano I, Balmes JR, Cummings KJ, Fishwick D, Miedinger D, et al. The occupational burden of nonmalignant respiratory diseases. An Official American Thoracic Society and European Respiratory Society Statement. Am J Respir Crit Care Med . 2019;199:1312–1334. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201904-0717ST. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Altman MC, Kattan M, O’Connor GT, Murphy RC, Whalen E, LeBeau P, et al. National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease’s Inner City Asthma Consortium Associations between outdoor air pollutants and non-viral asthma exacerbations and airway inflammatory responses in children and adolescents living in urban areas in the USA: a retrospective secondary analysis. Lancet Planet Health . 2023;7:e33–e44. doi: 10.1016/S2542-5196(22)00302-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Levy DT, Yuan Z, Luo Y, Mays D. Seven years of progress in tobacco control: an evaluation of the effect of nations meeting the highest level MPOWER measures between 2007 and 2014. Tob Control . 2018;27:50–57. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2016-053381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kannoth S, Chung SE, Tamakloe KD, Albrecht SS, Azan A, Chambers EC, et al. Neighborhood environmental vulnerability and pediatric asthma morbidity in US metropolitan areas. J Allergy Clin Immunol . 2023;152:378–385.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2023.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Heneghan JA, Goodman DM, Ramgopal S. Hospitalizations at United States children’s hospitals and severity of illness by Neighborhood Child Opportunity Index. J Pediatr . 2023;254:83–90.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2022.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kumar A, Zhang S, Neshteruk CD, Day SE, Konty KJ, Armstrong S, et al. The longitudinal association between asthma severity and physical fitness by neighborhood factors among New York City public school youth. Ann Epidemiol . 2023;88:37–42. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2023.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Aris IM, Perng W, Dabelea D, Padula AM, Alshawabkeh A, Vélez-Vega CM, et al. Environmental Influences on Child Health Outcomes Neighborhood opportunity and vulnerability and incident asthma among children. JAMA Pediatr . 2023;177:1055–1064. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2023.3133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Shanahan KH, James P, Rifas-Shiman SL, Gold DR, Oken E, Aris IM. Neighborhood conditions and resources in mid-childhood and dampness and pests at home in adolescence. J Pediatr . 2023;262:113625. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2023.113625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Banwell E, Collaco JM, Oates GR, Rice JL, Juarez LD, Young LR, et al. Area deprivation and respiratory morbidities in children with bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Pediatr Pulmonol . 2022;57:2053–2059. doi: 10.1002/ppul.25969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Laverty AA, Filippidis FT, Taylor-Robinson D, Millett C, Bush A, Hopkinson NS. Smoking uptake in UK children: analysis of the UK Millennium Cohort Study. Thorax . 2019;74:607–610. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2018-212254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Jha P, Peto R, Zatonski W, Boreham J, Jarvis MJ, Lopez AD. Social inequalities in male mortality, and in male mortality from smoking: indirect estimation from national death rates in England and Wales, Poland, and North America. Lancet . 2006;368:367–370. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68975-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Thun MJ, Carter BD, Feskanich D, Freedman ND, Prentice R, Lopez AD, et al. 50-year trends in smoking-related mortality in the United States. N Engl J Med . 2013;368:351–364. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1211127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Banks E, Joshy G, Weber MF, Liu B, Grenfell R, Egger S, et al. Tobacco smoking and all-cause mortality in a large Australian cohort study: findings from a mature epidemic with current low smoking prevalence. BMC Med . 2015;13:38. doi: 10.1186/s12916-015-0281-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. He H, He M-M, Wang H, Qiu W, Liu L, Long L, et al. In utero and childhood/adolescence exposure to tobacco smoke, genetic risk, and lung cancer incidence and mortality in adulthood. Am J Respir Crit Care Med . 2023;207:173–182. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202112-2758OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Alberg AJ, Shopland DR, Cummings KM. The 2014 Surgeon General’s report: commemorating the 50th anniversary of the 1964 report of the Advisory Committee to the US Surgeon General and updating the evidence on the health consequences of cigarette smoking. Am J Epidemiol . 2014;179:403–412. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwt335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.World Health Organization. 2023. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240077164

- 50. Parnham JC, Vrinten C, Cheeseman H, Bunce L, Hopkinson NS, Filippidis FT, et al. Changing awareness and sources of tobacco and e-cigarettes among children and adolescents in Great Britain. Tob Control . 2023:tc-2023-058011. doi: 10.1136/tc-2023-058011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Burhan H, Young R, Byrne T, Peat R, Furlong J, Renwick S, et al. Screening heroin smokers attending community drug services for COPD. Chest . 2019;155:279–287. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2018.08.1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Allinson JP, Chaturvedi N, Wong A, Shah I, Donaldson GC, Wedzicha JA, et al. Early childhood lower respiratory tract infection and premature adult death from respiratory disease in Great Britain: a national birth cohort study. Lancet . 2023;401:1183–1193. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(23)00131-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Sarkar C, Zhang B, Ni M, Kumari S, Bauermeister S, Gallacher J, et al. Environmental correlates of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in 96 779 participants from the UK Biobank: a cross-sectional, observational study. Lancet Planet Health . 2019;3:e478–e490. doi: 10.1016/S2542-5196(19)30214-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Shin S, Bai L, Burnett RT, Kwong JC, Hystad P, van Donkelaar A, et al. Air pollution as a risk factor for incident chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and asthma. A 15-year population-based cohort study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med . 2021;203:1138–1148. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201909-1744OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Rentschler J, Leonova N. Global air pollution exposure and poverty. Nat Commun . 2023;14:4432. doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-39797-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Burbank AJ, Hernandez ML, Jefferson A, Perry TT, Phipatanakul W, Poole J, et al. Environmental justice and allergic disease: a Work Group Report of the AAAAI Environmental Exposure and Respiratory Health Committee and the Diversity, Equity and Inclusion Committee. J Allergy Clin Immunol . 2023;151:656–670. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2022.11.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Hopkinson NS, Polkey MI. Does physical inactivity cause chronic obstructive pulmonary disease? Clin Sci (Lond) . 2010;118:565–572. doi: 10.1042/CS20090458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Jones RCM, Price D, Ryan D, Sims EJ, von Ziegenweidt J, Mascarenhas L, et al. Respiratory Effectiveness Group Opportunities to diagnose chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in routine care in the UK: a retrospective study of a clinical cohort. Lancet Respir Med . 2014;2:267–276. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(14)70008-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Doe GE, Williams MT, Chantrell S, Steiner MC, Armstrong N, Hutchinson A, et al. Diagnostic delays for breathlessness in primary care: a qualitative study to investigate current care and inform future pathways. Br J Gen Pract . 2023;73:e468–e477. doi: 10.3399/BJGP.2022.0475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Taskforce for Lung Health. 2018. https://cdn.shopify.com/s/files/1/0221/4446/files/PC1802_Taskforce_Report_MASTER_v8.pdf?30

- 61. Elbehairy AF, Quint JK, Rogers J, Laffan M, Polkey MI, Hopkinson NS. Patterns of breathlessness and associated consulting behaviour: results of an online survey. Thorax . 2019;74:814–817. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2018-212950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Hopkinson NS, Baxter N, London Respiratory Network Breathing SPACE-a practical approach to the breathless patient. NPJ Prim Care Respir Med . 2017;27:5. doi: 10.1038/s41533-016-0006-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Burke H, Wilkinson TMA. Unravelling the mechanisms driving multimorbidity in COPD to develop holistic approaches to patient-centred care. Eur Respir Rev . 2021;30:210041. doi: 10.1183/16000617.0041-2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Jamali H, Castillo LT, Morgan CC, Coult J, Muhammad JL, Osobamiro OO, et al. Racial disparity in oxygen saturation measurements by pulse oximetry: evidence and implications. Ann Am Thorac Soc . 2022;19:1951–1964. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.202203-270CME. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Peters DH, Garg A, Bloom G, Walker DG, Brieger WR, Rahman MH. Poverty and access to health care in developing countries. Ann N Y Acad Sci . 2008;1136:161–171. doi: 10.1196/annals.1425.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Hart JT. The inverse care law. Lancet . 1971;1:405–412. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(71)92410-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Wakefield MA, Loken B, Hornik RC. Use of mass media campaigns to change health behaviour. Lancet . 2010;376:1261–1271. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60809-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Nyblade L, Stockton MA, Giger K, Bond V, Ekstrand ML, Lean RM, et al. Stigma in health facilities: why it matters and how we can change it. BMC Med . 2019;17:25. doi: 10.1186/s12916-019-1256-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Brighton LJ, Chilcot J, Maddocks M. Social dimensions of chronic respiratory disease: stigma, isolation, and loneliness. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care . 2022;16:195–202. doi: 10.1097/SPC.0000000000000616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hopkinson NS, Molyneux A, Pink J, Harrisingh MC, Guideline Committee (GC) Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: diagnosis and management: summary of updated NICE guidance. BMJ. 2019;366:l4486. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l4486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Bourbeau J, Sebaldt RJ, Day A, Bouchard J, Kaplan A, Hernandez P, et al. Practice patterns in the management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in primary practice: the CAGE study. Can Respir J . 2008;15:13–19. doi: 10.1155/2008/173904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Meiwald A, Gara-Adams R, Rowlandson A, Ma Y, Watz H, Ichinose M, et al. Qualitative validation of COPD evidenced care pathways in Japan, Canada, England, and Germany: common barriers to optimal COPD care. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis . 2022;17:1507–1521. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S360983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Awokola BI, Amusa GA, Jewell CP, Okello G, Stobrink M, Finney LJ, et al. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in sub-Saharan Africa. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis . 2022;26:232–242. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.21.0394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Buttery S, Lewis A, Oey I, Hargrave J, Waller D, Steiner M, et al. Patient experience of lung volume reduction procedures for emphysema: a qualitative service improvement project. ERJ Open Res . 2017;3:00031-2017. doi: 10.1183/23120541.00031-2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Bloom CI, Slaich B, Morales DR, Smeeth L, Stone P, Quint JK. Low uptake of palliative care for COPD patients within primary care in the UK. Eur Respir J . 2018;51:1701879. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01879-2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Halpin DMG. Palliative care for people with COPD: effective but underused. Eur Respir J . 2018;51:1702645. doi: 10.1183/13993003.02645-2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Pumar MI, Gray CR, Walsh JR, Yang IA, Rolls TA, Ward DL. Anxiety and depression-important psychological comorbidities of COPD. J Thorac Dis . 2014;6:1615–1631. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2014.09.28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Stolbrink M, Thomson H, Hadfield RM, Ozoh OB, Nantanda R, Jayasooriya S, et al. The availability, cost, and affordability of essential medicines for asthma and COPD in low-income and middle-income countries: a systematic review. Lancet Glob Health . 2022;10:e1423–e1442. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(22)00330-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Montes de Oca M, Lopez Varela MV, Jardim J, Stirvulov R, Surmont F. Bronchodilator treatment for COPD in primary care of four Latin America countries: the multinational, cross-sectional, non-interventional PUMA study. Pulm Pharmacol Ther . 2016;38:10–16. doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2016.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Stolbrink M, Thomson H, Hadfield RM, Ozoh OB, Nantanda R, Jayasooriya S, et al. The availability, cost, and affordability of essential medicines for asthma and COPD in low-income and middle-income countries: a systematic review. Lancet Glob Health . 2022;10:e1423–e1442. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(22)00330-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Abdullah ASM, Husten CG. Promotion of smoking cessation in developing countries: a framework for urgent public health interventions. Thorax . 2004;59:623–630. doi: 10.1136/thx.2003.018820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Madawala S, Osadnik CR, Warren N, Kasiviswanathan K, Barton C. Healthcare experiences of adults with COPD across community care settings: a meta-ethnography. ERJ Open Res . 2023;9:00581–02022. doi: 10.1183/23120541.00581-2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Woo S, Zhou W, Larson JL. Stigma experiences in people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: an integrative review. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis . 2021;16:1647–1659. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S306874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Williams S, Sheikh A, Campbell H, Fitch N, Griffiths C, Heyderman RS, et al. Global Health Respiratory Network Respiratory research funding is inadequate, inequitable, and a missed opportunity. Lancet Respir Med . 2020;8:e67–e68. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30329-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Mun SY, Hwang YI, Kim JH, Park S, Jang SH, Seo JY, et al. Awareness of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in current smokers: a nationwide survey. Korean J Intern Med (Korean Assoc Intern Med) . 2015;30:191–197. doi: 10.3904/kjim.2015.30.2.191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Soriano JB, Calle M, Montemayor T, Alvarez-Sala JL, Ruiz-Manzano J, Miravitlles M. The general public’s knowledge of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and its determinants: current situation and recent changes. Arch Bronconeumol . 2012;48:308–315. doi: 10.1016/j.arbr.2012.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Hopkinson N. Acknowledging breathlessness post-covid. BMJ . 2021;373:n1264. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n1264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Hall I, Walker S, Holgate ST. Respiratory research in the UK: investing for the next 10 years. Thorax . 2022;77:851–853. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2021-218459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Laverty AA, Elkin SL, Watt HC, Millett C, Restrick LJ, Williams S, et al. Impact of a COPD discharge care bundle on readmissions following admission with acute exacerbation: interrupted time series analysis. PLoS One . 2015;10:e0116187. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0116187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Fletcher MJ, Upton J, Taylor-Fishwick J, Buist SA, Jenkins C, Hutton J, et al. COPD uncovered: an international survey on the impact of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [COPD] on a working age population. BMC Public Health . 2011;11:612. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Williams PJ, Cumella A, Philip KEJ, Laverty AA, Hopkinson NS. Smoking and socioeconomic factors linked to acute exacerbations of COPD: analysis from an Asthma + Lung UK survey. BMJ Open Respir Res . 2022;9:e001290. doi: 10.1136/bmjresp-2022-001290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Lu X, Yao Y, Jin Y. Digital exclusion and functional dependence in older people: findings from five longitudinal cohort studies. EClinicalMedicine . 2022;54:101708. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2022.101708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Philip KEJ, Polkey MI, Hopkinson NS, Steptoe A, Fancourt D. Social isolation, loneliness and physical performance in older-adults: fixed effects analyses of a cohort study. Sci Rep . 2020;10:13908. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-70483-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Lee JP, Maddox R, Kennedy M, Nahvi S, Guy MC. Off-White: decentring Whiteness in tobacco science. Tob Control . 2023;32:537–539. doi: 10.1136/tc-2023-057998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Cockerham WC. Health lifestyle theory and the convergence of agency and structure. J Health Soc Behav . 2005;46:51–67. doi: 10.1177/002214650504600105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Royal College of Physicians. 1962. https://www.rcplondon.ac.uk/projects/outputs/smoking-and-health-1962

- 97. Masters R, Anwar E, Collins B, Cookson R, Capewell S. Return on investment of public health interventions: a systematic review. J Epidemiol Community Health . 2017;71:827–834. doi: 10.1136/jech-2016-208141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]