Abstract

Cognitive impairment (CI) is common in α-synucleinopathies, i.e., Parkinson’s disease, Lewy bodies dementia, and multiple system atrophy. We summarize data from systematic reviews/meta-analyses on neuroimaging, neurophysiology, biofluid and genetic diagnostic/prognostic biomarkers of CI in α-synucleinopathies. Diagnostic biomarkers include atrophy/functional neuroimaging brain changes, abnormal cortical amyloid and tau deposition, and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) Alzheimer’s disease (AD) biomarkers, cortical rhythm slowing, reduced cortical cholinergic and glutamatergic and increased cortical GABAergic activity, delayed P300 latency, increased plasma homocysteine and cystatin C and decreased vitamin B12 and folate, increased CSF/serum albumin quotient, and serum neurofilament light chain. Prognostic biomarkers include brain regional atrophy, cortical rhythm slowing, CSF amyloid biomarkers, Val66Met polymorphism, and apolipoprotein-E ε2 and ε4 alleles. Some AD/amyloid/tau biomarkers may diagnose/predict CI in α-synucleinopathies, but single, validated diagnostic/prognostic biomarkers lack. Future studies should include large consortia, biobanks, multi-omics approach, artificial intelligence, and machine learning to better reflect the complexity of CI in α-synucleinopathies.

Subject terms: Parkinson's disease, Diagnostic markers, Prognostic markers, Parkinson's disease

Introduction

Abnormal aggregates of α-synuclein in the form of intraneuronal (e.g., Lewy bodies, Lewy neurites) or glial cytoplasmatic inclusions are involved in the pathophysiology of several neurodegenerative diseases, which have been collectively termed α-synucleinopathies1,2. In these disorders, α-synuclein is believed to self-propagate in a prion-like fashion, triggering the conversion from normal to misfolded protein isoforms, which in turn cause the progressive loss of vulnerable neurons in the central and peripheral nervous system3–5.

Depending on the topography of neuropathology and affected target cells (i.e., neurons, oligodendrocytes), α-synucleinopathies can be divided into Lewy body disease (LBD) and multiple system atrophy (MSA), each exhibiting distinct clinical and pathological features. Common clinical presentations of LBD include Parkinson’s disease (PD), PD-related dementia (PD-D) and dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB). PD is the most prevalent α-synucleinopathy, followed by DLB and PD-D6. DLB and PD/PD-D have been traditionally considered separate nosographic entities, but their consistent overlap in clinical, neuroimaging, pathophysiological and genetic features support a unifying view7. MSA is rarer, with ten-fold lower incidence and prevalence than PD8 (Table 1). Abnormal α-synuclein in the skin, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), and olfactory mucosa allows an in-vivo diagnosis of α-synucleinopathies and a biological definition of PD and DLB has been recently defined by means of genetic, α-synuclein and clinical biomarkers9,10.

Table 1.

Core neuropathological and clinical features of α-synucleinopathies

| α-synucleinopathy | Neuropathology | Clinical features | Cognitive features |

|---|---|---|---|

| PD, PD-D | Mild-to-moderate dopaminergic neuronal loss in the ventrolateral part of the substantia nigra; limbic and neocortical α-syn pathology1 | Bradykinesia, rigidity, resting tremor, non-motor features (e.g., olfactory loss, RBD, depression, cognitive impairment) | Impairment in executive domain in PD; deficits in multiple domains in PD-D |

| DLB | Moderate-to-severe dopaminergic neuronal loss in the ventrolateral part of the substantia nigra; limbic and neocortical α-syn pathology | Dementia, fluctuating cognition, visual hallucinations, RBD, parkinsonism | Significant impairment in executive, language, visuo-spatial domains |

| MSA | Glial cytoplasmatic inclusions in the basal ganglia, substantia nigra, pontine nuclei, medulla, cerebellum | Dysautonomia, parkinsonism, cerebellar syndrome, cognitive impairment | Significant deficit in executive (i.e., shifting) domain |

1For PD-D only.

α-syn alpha-synuclein, DLB dementia with Lewy bodies, MSA multiple system atrophy, PD Parkinson’s disease, PD-D Parkinson’s disease-related dementia, RBD rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder.

Cognitive impairment (CI) is one of the most disabling non-motor clinical manifestations of α-synucleinopathies, severely decreasing both patients’ and caregivers’ quality of life11,12. CI in α–synucleinopathies is highly heterogeneous in terms of prevalence, clinical, neuropathological and neuropharmacological features. CI is very common in PD, PD-D and DLB along the diseases course, with nearly half of the patients developing severe CI within 10 years after the diagnosis13. Mixed findings have been reported for CI in MSA; although severe CI was initially listed among its non-supporting diagnostic features, accumulating evidence suggests that cognitive symptoms are integral to the disease14,15. CI in α-synucleinopathies may range from subjective cognitive decline/impairment (SCD/SCI, i.e., subjective report of cognitive worsening despite no objective evidence of CI at cognitive testing and normal functioning in daily life), to mild cognitive impairment (MCI, i.e., mild cognitive disturbances with no functional impairment) and dementia (i.e., severe multidomain CI impacting basic daily life activities16). Different degrees of CI severity have been associated with specific α-synucleinopathies, with MSA and PD showing less severe CI (i.e., SCD/SCI, MCI) than PD-D and DLB, which are characterized by dementia. CI in α-synucleinopathies may also vary in terms of affected cognitive domains, with MSA being associated to deficits in shifting abilities compared to PD, whereas DLB shows more severe and widespread deficits involving attentive, visuo-spatial and language domains than PD-D17,18.

Multiple underlying neuropathologies (e.g., beta amyloid, tau neurofibrillary tangles) coexisting with α-synuclein accumulation may contribute to CI development and progression in α-synucleinopathies, further complicating neuropathological-based diagnosis19. Alzheimer’s disease (AD) neuropathology is common in DLB, with 18% of DLB patients showing advanced AD-related neuropathology according to in-vivo instrumental biomarkers and 28% having sufficient post-mortem AD neuropathology to receive a secondary diagnosis of AD20.

The neuropharmacology of CI in α-synucleinopathies involves the disruption of multiple neurotransmitter systems, including both dopaminergic and non-dopaminergic (i.e., serotonin, noradrenalin, acetylcholine) networks21–23, adding further complexity to the identification of effective treatment strategies16.

The clinical diagnosis of CI in α–synucleinopathies is now based on well-defined, widely available criteria24,25, however it is not always reliable and even expert centers may fail to early identify patients with subtle CI-related symptoms. Post-mortem studies are traditionally considered the gold standard for exploring neuropathology of CI in α–synucleinopathies, but they are limited to selected cases and do not offer information on early disease stages. Biomarkers are characteristics that may be objectively measured and evaluated as in-vivo indicators of presence of normal/pathological biologic processes, risk of developing neuropathology, biological responses to a therapeutic intervention. Biomarkers can be classified into diagnostic, prognostic, predictive, susceptibility/risk, monitoring, and pharmaco-dynamic/response according to the type of information they offer26,27. Several attempts have been made to validate single specific and sensitive diagnostic or prognostic biomarkers of CI in α-synucleinopathies, but results have been inconclusive28,29. Neuroimaging biomarkers, despite proving sensitive in detecting CI in α-synucleinopathies, appear not to be specific and reliable enough to accurately predict CI progression at a single-patient level30. Although reports on CSF biomarkers have shown promising results for diagnostic and prognostic purposes, data on less invasive and cost-effective modalities (e.g., blood, plasma-based) warrant further research28,31. These inconclusive findings may be due to the complexity of the neuropathology and neuropharmacology of CI in in α-synucleinopathies, as briefly discussed above.

In light of these considerations, the adoption of a multimodal approach based on a system biology perspective and coupling neuroimaging, neurophysiological, biofluid and genetic biomarkers, may better reflect the complexity of CI in α-synucleinopathies. This paper has been conceived within this framework; we herein provide an overview of systematic reviews (SRs) with/without meta-analyses (MAs) exploring structural/functional neuroimaging, neurophysiological, biofluid and genetic biomarkers for CI in α-synucleinopathies, with a focus on diagnostic and prognostic ones. We further introduced a preliminary classification approach to score biomarkers that proved diagnostic or prognostic significance according to evidence levels, clinical utility, and reproducibility, to provide recommendations for designing future multi-omics biomarker studies on CI diagnosis and prognosis.

Results

Identification and selection of the studies

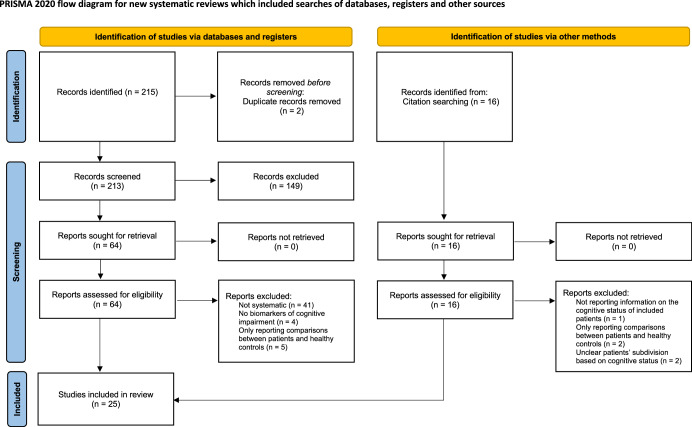

The literature search yielded a total of 215 records. After duplicates removal, 213 unique records were obtained for title and abstract screening. One hundred forty-nine articles were excluded based on title/abstract, and 64 full texts were in-depth examined according to eligibility criteria. Sixteen additional papers were retrieved from citation searching. Eighty papers were finally obtained for full-text screening. Two authors (EM, ST) independently assessed the selected full texts. Disagreement concerned two papers (inter-raters’ agreement: 96%) and was solved by discussion. Twenty-five papers fulfilled inclusion criteria and were therefore included in the overview (Fig. 1). The retrieved SRs and MAs were grouped according to the population of interest at review level (i.e., patients with PD) and the type of biomarkers (i.e., neuroimaging, neurophysiological, biofluids, genetics). No eligible SRs or MAs including patients with MSA were found.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flowchart of the study.

Characteristics of the included studies

Neuroimaging and neurophysiology biomarkers of cognitive impairment in Parkinson’s disease

Fourteen papers, of which six SRs30,32–36 and eleven MAs37–47, were found on neuroimaging and neurophysiology biomarkers of CI associated with PD and DLB (Table 2).

Table 2.

Systematic reviews and meta-analyses of neuroimaging and neurophysiology biomarkers of cognitive impairment in Parkinson’s disease and dementia with Lewy bodies

| Ref. | Study design | Included studies (N, design) | Included subjects (N, diagnosis) | Biomarker | Cognitive dysfunction severity | Group comparisons | Main results | Conclusions | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type | Purpose | ||||||||

| Structural neuroimaging | |||||||||

| 44 | Voxel-wise MA | N: 15, cross-sectional |

PD-NC: 192 PD-ND: 233 PD-MCI: 92 PD-D: 168 |

Structural MRI (GM volume) | Diagnosis |

PD-ND PD-MCI PD-D |

PD-MCI vs PD-NC PD-D vs PD-ND |

GM atrophy in the left superior temporal lobe, insula and superior frontal lobe in PD-MCI vs PD-NC GM atrophy in bilateral superior temporal lobe extending to hippocampus, insula, inferior frontal lobe, left superior frontal lobe in PD-D vs PD-ND |

PD-MCI and PD-D are associated with reduced GM volume within frontal, limbic and temporal regions |

| 40 | Voxel-wise MA | N: 20, cross-sectional |

PD-NC: 554 PD-MCI: 504 |

Structural MRI (GM volume) | Diagnosis | PD-MCI | PD-MCI vs PD-NC | GM atrophy in the left anterior (most robust) and posterior (less robust) insula in PD-MCI vs PD-NC | GM atrophy in the anterior insula may serve as a biomarker for PD-MCI |

| 43 | Voxel-wise MA | N: 12, cross-sectional |

PD-NC: 326 PD-MCI: 243 |

Structural MRI (GM volume) | Diagnosis | PD-MCI | PD-MCI vs PD-NC | GM atrophy in left insula, superior and inferior temporal gyri in PD-MCI vs PD-NC | PD-MCI is associated with insula and temporal gyrus atrophy |

| 41 | MA | N: 11, longitudinal, (2 on PD-CI) |

PD-NC: 41 PD-CI: 23 |

Structural MRI (GM volume) | Prognosis | PD-CI | PD-CI vs PD-NC | Greater whole brain volume loss in PD-CI vs PD-NC (SMD: −1.16% per year; 95% CI: [−1.71, −0.60]) | PD-CI is associated with progressive whole brain volume loss |

| 34 | SR | N: 39 (6 longitudinal studies on PD-CI) |

PD-NC: 228 PD-MCI: 95 |

Structural MRI (GM volume; diffusion) | Prognosis | PD-MCI or PD-D |

PD-MCI vs PD-NC PD-D vs PD-MCI |

Reduced hippocampal volume over time predicts conversion from PD-NC to PD-MCI and from PD-MCI to PD-D | Structural hippocampal alterations may be related to PD-CI progression |

| 30 | SR | N: 39, longitudinal (18 on PD-CI) |

PD-N: 53 PD-MCI + PD-D: 352 |

Structural MRI (cth; GM volume; WM volume, diffusion) | Prognosis | PD-MCI or PD-D |

PD-MCI vs PD-NC PD-D vs PD-MCI |

PD-MCI. Whole-brain, right caudate, thalamus, amygdala, NAcc volume loss, frontal, temporal, parietal and occipital Cth reduction over time. PD-MCI converters. GM atrophy in the right temporal pole and in the caudal anterior cingulate at baseline; whole brain, left thalamus, caudate, right NAcc volume loss, ventricular enlargement, right temporal, bilateral frontal lobe GM, hippocampus atrophy and reduced FA in WM frontal regions over time PD-D converters. Whole-brain atrophy and WM loss, right precentral gyrus, frontal gyri and anterior cingulum Cth reduction, and hippocampus atrophy at baseline; whole-brain, temporal, insular, occipital, hippocampal GM volume loss, frontal, temporal, parietal and occipital Cth reduction over time |

Volume loss in various cortical and subcortical brain areas and atrophy and widespread WM changes are associated with progression of CI in PD |

| Functional neuroimaging | |||||||||

| 39 | Voxel-wise MA | N: 17, cross-sectional |

PD-NC: 289 PD-MCI: 222 PD-D: 68 |

rs-fMRI (functional connectivity) | Diagnosis |

PD-MCI PD-D |

PD-CI vs PD-NC | Lower connectivity of the left precuneus, superior frontal gyri, right median cingulate gyrus, precentral gyrus and increased connectivity of the right cerebellum in PD-CI vs PD-NC | PD-CI is associated with reduced connectivity within the DMN (medial parietal, bilateral inferior-lateral-parietal, ventromedial frontal cortices) |

| PET (metabolism, synaptic density, amyloid and tau) neuroimaging | |||||||||

| 37 | MA | N: 11, cross-sectional |

PD-MCI: 60 PD-D: 74 DLB: 99 |

PiB PET (amyloid deposition) | Diagnosis |

PD-MCI PD-D DLB |

Indirect comparisons between groups | Higher prevalence of PiB positive PET imaging for DLB (0.68; 95% CI: [0.55, 0.82]) vs PD-D (0.34; 95% CI: [0.13, 0.56]) and PD-MCI (0.05; 95% CI: [-0.07, 0.17]) | Higher PiB-positive PET imaging in DLB vs. PD-D, and lower prevalence in PD-MCI vs PD-D and DLB. |

| 46 | MA | N: 15, cross-sectional (4 studies on PD-CI) |

PD-NC: 61 PD-MCI: 96 PD-D: 13 |

Tau PET (tau deposition) | Diagnosis |

PD-MCI PD-D |

PD-CI vs PD-NC PD-D vs PD-ND |

Higher binding in the entorhinal region for PD-CI vs PD-NC (SMD: 0.55; 95% CI: [0.19, 0.91]) Inconsistent data in regional tracer binding for PD-D vs PD-ND |

Region-specific higher binding of the tau-tracer in the entorhinal region in PD-CI vs PD-NC |

| 36 | SR | N: 36, cross-sectional (4 studies on PD-CI and DLB) |

PD-ND: 21 PD-D: 4 DLB: 9 |

[18F] FDG PET (brain metabolism), [11C] UCB-J PET (synaptic density) | Diagnosis |

PD-ND PD-D DLB |

DLB/PD-D vs PD-ND | Reduced [18F] FDG uptake and [11C] UCB-J in DLB/PD-D vs PD-ND with the former exceeding the latter | The progressive hypometabolism in LBD cannot be fully explained by generalized synaptic degeneration |

| Combined neuroimaging | |||||||||

| 38 | Coordinate-based MA | N: 34, cross-sectional |

PD-NC: 796 PD-MCI: 577 PD-ND: 278 PD-D: 178 |

Structural MRI (GM volume, cth); fMRI; FDG PET | Diagnosis | PD-MCI or PD-D |

PD-MCI vs PD-NC PD-D vs PD-NC |

GM atrophy in the right supramarginal gyrus, left posterior insula and mid-cingulate cortex in PD-MCI vs PD-NC Left angular gyrus and bilateral DLPFC functional changes in PD-MCI vs. PD-NC GM atrophy in bilateral insula in PD-D vs PD-ND |

Structural and functional changes in not-overlapping areas of the somatosensory and executive networks in PD-MCI PD-D is associated to larger GM volume loss, involving bilateral insula |

| Neurophysiology | |||||||||

| 33 | SR | N: 36, cross-sectional, longitudinal (23 on PD-CI) | PD: 1387 (no details on cognitive status) | qEEG (α, β, δ, θ power; slowing ratio; dominant frequency; connectivity) |

Diagnosis Prognosis |

NR | PD-CI vs PD-NC |

Cross-sectional. EEG slowing (lower α and β, higher δ and θ power) correlates with global and domain specific PD-CI; some connectivity measures may be associated to PD-CI Longitudinal. Higher θ power at baseline predicts cognitive deterioration in PD-CI |

EEG slowing correlates with PD-CI and may predict cognitive decline at individual level |

| 32 | SR | N: 50, cross-sectional, longitudinal (9 on PD-CI) |

PD-NC: 57 PD-D: 46 |

MEG (spectral power analysis; connectivity) |

Diagnosis Prognosis |

NR | PD-D vs PD-ND |

Cross-sectional. Conflicting data on connectivity measures associated to PD-D Longitudinal. Lower β band power, higher θ power at baseline, spectral slowing and more random θ band topology correlated with cognitive decline |

MEG markers of spectral slowing may predict conversion to PD-D |

| 42 | MA | N: 15, cross-sectional (8 on PD-CI) | NR | TMS (SAI) | Diagnosis | PD-CI | PD-CI vs PD-NC | SAI more impaired in PD-CI than PD-NC and associated to visuo-spatial, executive, memory, and attention deficits | SAI correlated to PD-CI and strongly with visuo-spatial and executive function |

| 47 | MA | N: 71, cross-sectional (15 on PD-CI) |

PD-NC: 39 PD-MCI: 31 PD-D: 30 |

TMS (SAI, SICI, ICF) | Diagnosis |

PD-MCI PD-D |

PD-MCI vs PD-NC PD-D vs PD-NC |

Reduced SAI in PD-MCI than PD-NC Increased SICI and reduced ICF in PD-D vs PD-MCI and PD-NC |

Increased GABAergic, and decreased glutamatergic and cholinergic transmission in PD-CI |

| 45 | MA | N: 39, cross-sectional (3 on PD-CI) |

PD-NC: 75 PD-D: 29 |

ERP (P300) | Diagnosis | PD-D | PD-D vs PD-NC | Prolonged P300 latency at Cz in PD-D than PD-NC (SMD: 1.49; 95%CI: [0.05–2.92]) | Prolonged P300 may be a potential biomarker of PD-D |

| Combined neuroimaging and neurophysiology | |||||||||

| 35 | SR | N: 10, cross-sectional |

PD-NC: 170 PD-MCI: 355 |

Neuroimaging (structural and functional MRI, PET, SPECT), EEG | Diagnosis | PD-MCI | PD-MCI vs PD-NC |

PD-aMCI vs PD-NC. Reduced FA in the corpus callosum, bilateral cingulate gyri, bilateral posterior thalamic radiation, bilateral posterior corona radiata, left superior corona radiata, right tapetum, bilateral superior and inferior longitudinal fascicles, bilateral inferior fronto-occipital fascicles, left fornix; reduced functional connectivity within the DMN; reduced dopaminergic receptor availability in the right parahippocampal gyrus, bilateral insula, bilateral anterior cingulate cortex; reduced striatal vesicular monoamine transporter binding in the associative striatum PD-naMCI vs PD-NC. Reduced functional connectivity within the visual network; reduced dopaminergic receptor availability in the bilateral insula, right parahippocampal gyrus PD-exMCI vs PD-NC. Abnormal spectral ratio in the frontal cortex and frontal pole; reduced binding in the bilateral frontal, temporal and parietal cortices, the cerebellum, the midbrain and the putamen; reduced binding in the bilateral caudate nuclei |

PD-aMCI is associated with structural and functional changes in posterior (parietal, occipital, temporal) regions. PD-naMCI and PD-exMCI are associated with less robust functional and neurophysiological changes. More severe CI is associated with more marked structural and functional neuroimaging changes |

Aß beta-amyloid, BBB blood–brain barrier; CI confidential interval, CSF cerebrospinal fluid, cth cortical thickness, Cys C Cystatin C, DLB dementia with Lewy Bodies, DLPFC dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, DMN default-mode network, dMRI diffusion magnetic resonance imaging, DTI diffusion tensor imaging, EEG electroencephalography, ERP event related potential, FA fractional anisotropy, FDG [18 F]-fluorodeoxyglucose, fMRI functional magnetic resonance imaging, FU follow-up, GM gray matter, GWAS genome-wide association study, HC healthy controls, ICF intracortical facilitation, LBD Lewy body disease, MA meta-analysis, MCI mild cognitive impairment, MEG magnetoencephalography, MRI magnetic resonance imaging, N number, NAcc nucleus accumbens, NfL neurofilament light chain, NR not reported, PD Parkinson’s disease, PD-aMCI patients with Parkinson’s disease and amnestic mild cognitive impairment, PD-D patients with Parkinson’s disease related dementia, PD-CI patients with Parkinson’s disease and cognitive impairment, PD-exMCI patients with Parkinson’s disease and executive mild cognitive impairment, PD-MCI patients with Parkinson’s disease and mild cognitive impairment, PD-naMCI patients with Parkinson’s disease and non-amnestic mild cognitive impairment, PD-NC patients with Parkinson’s disease and normal cognition, PD-ND patients with Parkinson’s disease and no dementia, PET positron emission tomography, PiB Pittsburgh Compound B, p-tau phosphorylated tau, Qalb = CSF/serum albumin quotient, qEEG quantitative electroencephalography, rs-fMRI resting state functional magnetic resonance imaging, SAI short afferent inhibition, SICI short-interval intracortical inhibition, SMD standardized mean difference, SPECT single photon emission computed tomography, SR systematic review, TMS transcranial magnetic stimulation. t-tau total tau, WM white matter.

Neuroimaging biomarkers

Eleven studies were found on neuroimaging biomarkers, of which six on structural30,34,40,41,43,44, one on functional39, one on amyloid37, one on tau46, one on brain metabolism and synaptic density36, and one on combined measures38. Eight SRs and MAs included studies with diagnostic purposes36–40,43,44,46, whilst one MA41 and two SRs30,34 included studies with prognostic purposes.

Three voxel-wise MAs explored gray matter volume changes associated to CI in PD and converged in reporting GM atrophy in the left insula that extended to the superior and inferior temporal lobe, and superior frontal lobe when comparing PD-MCI to PD without CI40,43,44. A single voxel-wise MA found gray matter atrophy involving the bilateral superior temporal lobe extending to hippocampus, insula, inferior frontal lobe, and the left superior frontal lobe in PD vs. PD-D44. A MA of region-of-interest-based volumetric longitudinal analyzes of structural MRI data documented significant whole-brain volume loss of 1.16% per year in PD with cognitive decline compared to cognitively normal PD41. A SR of MRI studies reported that reduced hippocampal volume over time may predict conversion from PD with normal cognition (PD-NC) to PD-MCI and from PD-MCI to PD-D34. A SR of structural MRI studies addressing gray and white matter reported atrophy in various cortical and subcortical brain areas and widespread white matter changes to be associated with conversion to PD-MCI and PD-D; in particular, PD-MCI converters showed greater atrophy accumulation in fronto-temporal areas, caudate, thalamus and nucleus accumbens compared to non-converters over time30.

A voxel-wise MA of resting-state functional MRI studies reported reduced connectivity in the left precuneus, right median cingulate gyrus, left superior frontal gyrus and right precentral gyrus, together with an increased functional connectivity of the right cerebellum suggesting reduced connectivity within the DMN when comparing PD with CI to PD-NC39.

A MA of amyloid imaging using Pittsburgh Compound B (PiB), i.e., the most validated PET tracer for non-invasive in vivo imaging of abnormal amyloid deposition in the brain48, in subjects with α-synucleinopathies and CI reported substantial variability in the prevalence of “PiB-positive” studies, with higher prevalence in DLB than PD-D, while PD-MCI subjects showed overall lower PiB-positive prevalence than PD-D and DLB, as well as in comparison to reported findings in non-PD associated MCI37.

A MA of tau PET imaging reported higher tau tracer binding in the entorhinal region in PD with CI than PD-NC, while inconsistent results were found when comparing PD-D to PD without dementia (PD-ND, i.e., PD-NC and PD-MCI)46.

A SR of brain metabolism and synaptic density PET imaging studies found a regional decoupling of metabolic activity and synaptic density when comparing DLB/PD-D to PD-ND, with the former exceeding the latter36.

A coordinate-based MA documented structural alterations in the right supramarginal gyrus, left posterior insula and mid-cingulate cortex that did not overlap with functional changes in areas (i.e., left angular gyrus, bilateral dorsolateral prefrontal cortex) underlying executive processing and supporting the existence of PD-MCI subtyping, and gray matter atrophy in bilateral insula in PD-D38.

Neurophysiological biomarkers

A SR of cross-sectional and longitudinal quantitative electroencephalography (EEG) studies reported EEG slowing (i.e., lower α and β, higher δ and θ power), and some connectivity measures to be associated to PD with CI compared to PD-NC, and higher θ power levels at baseline as a predictor of PD-related cognitive deterioration at single patient level33. A SR of cross-sectional and longitudinal magnetoencephalography (MEG) studies reported conflicting data on connectivity measures as diagnostic biomarkers of PD-D, while lower β band power, higher θ power at baseline, spectral slowing and more random θ band topology correlated with cognitive decline32. A MA documented that short-latency afferent inhibition (SAI), a neurophysiological marker of cholinergic dysfunction, which is obtained through the conditioning of a cortical transcranial magnetic stimulus by electrically stimulating contralateral peripheral hand nerves with an inter-stimulus interval (ISI) of ∼20 ms, was more impaired in PD with CI than PD-NC. Furthermore, the SAI was associated to visuo-spatial, executive, memory, and attention deficits of PD, with a stronger association to the two former domains42. Short-interval intracortical inhibition (SICI, ISI = 1–4 ms) and intracortical facilitation (ICF; ISI = 7–20 ms), neurophysiological markers of GABAergic and glutamatergic function, respectively, were reported to be altered in PD-D than PD-MCI and PD-NC47. The latency of P300, an event-related potential that is thought to reflect cognitive processing, has been reported to be prolonged for PD-D patients compared to PD-NC in a recent MA45.

Combined neuroimaging and neurophysiological biomarkers

A SR on diagnostic biomarkers summarized the main structural and functional neuroimaging and the neurophysiological changes associated with PD-MCI subtypes and found consistent structural and functional changes in posterior (i.e., occipital, parietal, temporal) regions in amnestic PD-MCI compared to PD-NC, with less robust functional neuroimaging and neurophysiological changes in non-amnestic and executive PD-MCI subtypes and more marked structural and functional neuroimaging abnormalities associated with more severe CI35.

Biofluid and genetic biomarkers of cognitive impairment in Parkinson’s disease

Seven papers, of which one SR49 and six MAs50–55 were found on biofluid and genetic biomarkers of CI in PD (Table 3).

Table 3.

Systematic reviews and meta-analyses of biofluid and genetic biomarkers of cognitive impairment in Parkinson’s disease

| Ref. | Study design | Included studies (N, design) | Included subjects (N, diagnosis) | Biomarker | Cognitive dysfunction severity | Group comparisons | Main results | Conclusions | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type | Purpose | ||||||||

| Biofluids (CSF) | |||||||||

| 49 | SR | N: 58, cross-sectional, prospective cohort (14 on PD-CI) |

PD-NC: 1696 PD-MCI: 62 PD-D: 136 |

ILs, serpin A1, BDNF, Aß1-42; t-tau; p-tau; APO A1/A2/ε; VDBP |

Diagnosis Prognosis |

PD-MCI or PD-D | PD-MCI/PD-D vs PD-NC |

Cross-sectional. Lower CSF Aß1-42 associated with single cognitive domain dysfunction and PD-D. Increased CSF p-tau and t-tau correlate with poorer cognitive performance Longitudinal. Aß1-42 is a predictor of cognitive decline and dementia in PD |

CSF amyloid fractions and tau-protein may be associated and have predictive value in the development of CI in PD |

| 50 | MA | N: 16, retrospective, prospective and cross-sectional |

PD-NC: 1182 PD-CI (PD-MCI or PD-D): 590 |

Aß42; t-tau; p-tau | Diagnosis | PD-MCI or PD-D |

PD-MCI vs PD-NC PD-D vs PD-NC |

Lower CSF Aß42 (SMD: -0.44; 95% CI: [-0.61, -0.26]; p < 0.00001) levels in PD-CI vs PD-NC Lower CSF Aß42 (SMD: −0.60; 95% CI: [−0.75, −0.45]; p < 0.00001), increased t-tau (SMD: 0.21; 95% CI: [0.06, 0.35]; p = 0.006) and p-tau (SMD: 0.36; 95% CI: [0.02, 0.69]; p = 0.04) levels in PD-D vs PD-NC |

Amyloid pathology and tauopathy may participate in the development of PD-D |

| Biofluids (plasma/serum) | |||||||||

| 51 | MA | N: 15, cross-sectional |

PD-NC: 843 PD-CI: 573 |

Plasma Hcy, vitamin B12, and folate | Diagnosis | PD-CI | PD-CI vs PD-NC | Higher Hcy (MD: 5.05; 95% CI: [4.03, 6.07]), and lower vitamin B12 (MD: -47.58; 95% CI: [-72.07, -23.09]) and folate levels (MD: -0.21; 95% CI: [-0.34, -0.08]) in PD-CI vs PD-NC | Increased Hcy and reduced vitamin B12 and folate levels are potentially associated with PD-CI |

| 54 | MA | N: 16, cross-sectional (4 on PD-CI) | PD: 411 | Serum Cys C | Diagnosis | PD-MCI | PD-MCI vs PD-NC | Higher Cys C serum levels (SMD: 1.29; 95% CI: [0.47, 2.10]; p < 0.05) in PD-MCI vs PD-NC | Serum Cys C may be a promising biomarker for PD-CI |

| Biofluids (combined CSF and blood) | |||||||||

| 55 | MA | N: 51, cross-sectional (7 including PD-D patients) |

PD-NC: 414 PD-D: 163 |

CSF and blood biomarkers of BBB disruption | Diagnosis | PD-D | PD-D vs PD-NC | Increased blood NfL level (SMD: 0.60; 95% CI: [0.35, 0.84; p < 0.001) and Qalb (SMD: 0.48; 95% CI: [0.19, 0.77]; p = 0.010) in PD-D vs PD-NC | BBB disruption may be involved in CI in PD |

| Genetics | |||||||||

| 52 | MA | N: 6 case-control | PD | BDNF Val66Met polymorphism | Prognosis | PD-CI | PD-CI vs PD-NC | BDNF Val66Met polymorphism is significantly associated with CI in Caucasian PD populations | BDNF Val66Met polymorphism may be a risk factor for PD-CI among Caucasians |

| 53 | MA | N: 6 case-control |

PD-NC: 547 PD-CI: 340 |

BDNF Val66Met polymorphism | Prognosis | PD-CI | PD-CI vs PD-NC | BDNF Val66Met is associated with increased risk of CI in additive (OR: 3.82; 95% CI: [1.32, 11.08]; p = 0.01) and recessive (OR: 3.81; 95% CI: [1.38, 10.53]; p = 0.01) models in Caucasians | Homozygote BDNF Val66Met may be associated with increased risk of PD-CI among Caucasians |

Aß = beta-amyloid, BBB blood–brain barrier, BDNF brain-derived neurotrophic factor, CI confidential interval, CSF cerebrospinal fluid, Cys C Cystatin C, GWAS genome-wide association study, HC healthy controls, Hcy homocysteine, ILs interleukins, MA meta-analysis, MCI mild cognitive impairment, N number, NfL neurofilament light chain, PD Parkinson’s disease, PD-CI patients with Parkinson’s disease and cognitive impairment, PD-D patients with Parkinson’s disease related dementia, PD-MCI patients with Parkinson’s disease and mild cognitive impairment, PD-NC patients with Parkinson’s disease and normal cognition, p-tau phosphorylated tau, Qalb CSF/serum albumin quotient, OR, odds ratio, SMD standardized mean difference, SR systematic review, t-tau total tau, VDBP vitamin D binding protein.

Biofluid biomarkers

We found five studies on biofluid biomarkers, of which two on cerebrospinal fluid (CSF)49,50, two on plasma/serum51,54 and one addressing both CSF and plasma/serum biomarkers55. Most of them focused on studies with diagnostic purposes50,51,54,55, while only one included prognostic biomarkers studies49 (Table 3).

A SR that included CSF biomarker studies focusing on different disease pathways (i.e., oxidative stress, neuroinflammation, lysosomal dysfunction and proteins involved in PD and other neurodegenerative disorders) reported lower amyloid beta 1–42 (Aß42) and increased total tau (t-tau) and phosphorylated tau181 (p-tau), which are core biomarkers for AD diagnosis, in the CSF of PD-D compared to PD-NC49. These findings were confirmed in a MA focusing on CSF AD biomarkers in PD 50. Besides, CSF levels of Aß42 were shown as good predictors of cognitive decline in PD and progression to PD-D49.

A MA reported increased plasma homocysteine and lower levels of vitamin B12 and folate, which together might be toxic on neurons and vascular walls, in PD patients with CI compared to cognitively intact ones51. Higher serum levels of Cystatin C, a protease inhibitor and a reliable biomarker of kidney disfunction that has been associated to several neurological disorders including AD, were reported in PD-MCI compared to PD-NC in a MA54.

Higher levels of serum neurofilament light chain (NfL) and increased CSF/serum albumin quotient were reported in PD-D patients compared to those with normal cognition in a recent MA focused on biomarkers of blood–brain barrier disruption55.

Genetic biomarkers

We found two MAs on genetic biomarkers of CI in PD with prognostic purposes52,53. Both MAs explored the relationship between the functional polymorphism Val66Met in the gene encoding brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and increased CI risk and converged in reporting a significant association in Caucasian populations with PD52,53.

Mixed biomarkers of cognitive impairment in Parkinson’s disease

We found one prognostic MA56 on clinical, neuroimaging, neurophysiological, biofluid and genetic prognostic biomarkers that included prospective cohort studies of PD patients without CI at baseline and found apolipoprotein E (APOE) ε2 and ε4 alleles and EEG slowing (i.e., reduced α, increased θ power) to be associated with an increased risk of CI in PD56 (Table 4).

Table 4.

Systematic reviews and meta-analyses of combined biomarkers of cognitive impairment in Parkinson’s disease

| Ref. | Study design | Included studies (N, design) | Included subjects (N, diagnosis) | Biomarker | Cognitive dysfunction severity | Group comparisons | Main results | Conclusions | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type | Purpose | ||||||||

| 56 | MA | N: 57 prospective, cohort |

PD-CI (CSF): 1698 PD-CI (EEG): 180 |

Neuroimaging (MRI, DAT SPECT); EEG (α, β, δ, θ power); CSF (Aß42; t-tau); genetics (APOE alleles; MAPT H1/H1; GBA mutations) | Prognosis | PD-CI | PD-CI vs PD-NC |

APOE ε2 (RR: 6.47; 95% CI: [1.29, 32.53]; p = 0.09) and ε4 alleles (RR: 3.04; 95% CI: [1.88, 4.91]; p = 0.06) are associated with an increased risk of PD-CI Reduced median α power (RR: 1.77; 95% CI: [1.07, 2.92]; p = 0.75) and increased median θ power (RR: 2.93; 95% CI: [1.61, 5.33]; p = 0.92) are associated with an increased risk of PD-CI |

APOE alleles and EEG slowing may be promising predictors for PD-CI |

Aß beta-amyloid, APOE apolipoprotein gene, CI confidential interval, CSF cerebrospinal fluid, DAT dopamine transporter, EEG electroencephalogram, GBA glucocerebrosidase, MA meta-analysis, MAPT microtubule associated protein tau, MRI magnetic resonance imaging, PD-CI patients with Parkinson’s disease and cognitive impairment, PD-NC patients with Parkinson’s disease and normal cognition, SPECT single-photon emission computed tomography, RR relative risk, t-tau total tau.

Risk of bias of included studies

The results of the JBI checklist showed a mean overall score of 4.16, indicating that the overall quality of the included SRs and MAs was generally low. Specifically, twelve papers were judged to be of moderate quality, while the remaining thirteen were deemed to be of low quality (Supplementary Table 1).

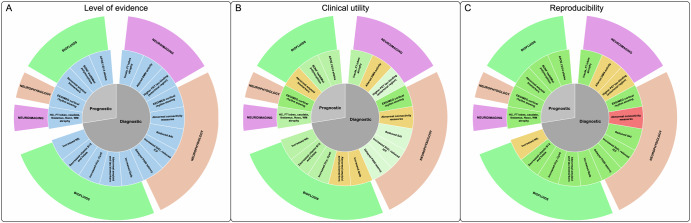

Assessment of evidence levels, clinical utility and reproducibility

Nineteen biomarkers were considered to have diagnostic (N = 14) and prognostic (N = 5) significance according to the level of evidence, clinical utility, and reproducibility. All biomarkers had B2 level of evidence (i.e., evidence from cross-sectional and longitudinal cohort biomarker studies); five had questionable clinical utility, while the remaining 14 had higher-to-intermediate clinical utility. Most biomarkers (N = 14) had high-to-moderate reproducibility, while 3/19 and 1/19 had low and questionable reproducibility, respectively (Table 5; Fig. 2).

Table 5.

Proposed classification of the biomarkers here reviewed that proved diagnostic or prognostic significance according to level of evidence, clinical utility and reproducibility

| Type of biomarker | Level of evidence1 | Clinical utility2 | Reproducibility3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical/research application | Diagnostic/prognostic yield | Non-invasiveness | Accessibility | ||||

| Diagnosis | Neuroimaging | ||||||

| Atrophy of the insula, and frontal and temporal lobes | B2 | C | + | + | - | + | |

| Altered DMN activity | B2 | R | - | + | - | - | |

| Higher PET tau-binding in the entorhinal region | B2 | C | + | + | - | - | |

| Neurophysiology | |||||||

| EEG/MEG cortical rhythm slowing | B2 | C | + | + | + | + | |

| Abnormal connectivity measures | B2 | R | - | + | - | - | |

| Reduced SAI | B2 | C | + | + | - | + | |

| Increased SICI, reduced ICF | B2 | C | + | + | - | + | |

| Delayed P300 latency | B2 | R | - | + | - | + | |

| Biofluids – CSF | |||||||

| Increased albumin quotient | B2 | C | - | - | - | + | |

| Anormal amyloid and tau biomarkers | B2 | C | + | - | - | + | |

| Biofluids – plasma/serum | |||||||

| Increased albumin quotient | B2 | C | - | + | + | + | |

| Increased homocysteine, cystatin C | B2 | C | - | + | + | + | |

| Decreased vitamin B12 and folate | B2 | C | - | + | + | + | |

| Increased NfL | B2 | C | + | + | - | - | |

| Prognosis | Neuroimaging | ||||||

| Atrophy of the hippocampus, fronto-temporal lobes, caudate, thalamus, NAcc, WM | B2 | C | + | + | - | + | |

| Neurophysiology | |||||||

| EEG/MEG cortical rhythm slowing | B2 | C | + | + | + | + | |

| Biofluids - CSF | |||||||

| Abnormal amyloid biomarkers | B2 | C | + | - | - | + | |

| Genetics | |||||||

| BDNF Val66Met polymorphism | B2 | R | + | + | - | + | |

| APOE ε2/ε4 alleles | B2 | C | + | + | - | + | |

APOE apolipoprotein E gene, BDNF brain-derived neurotrophic factor, C clinical, CSF cerebrospinal fluid, DMN default mode network, EEG electroencephalography, ICF intracortical facilitation, MEG magnetoencephalography, NAcc nucleus accumbens, NfL neurofilament light chain, PET positron emission tomography, R research, SAI short afferent inhibition, SICI short-interval intracortical inhibition, WM white matter.

1Level of evidence defined according to the following classification 106: A = proven/consensus association in human medicine; B1 = prospective, randomized clinical trial; B2 = cross-sectional and longitudinal cohort biomarker studies; B3 = retrospective biomarker studies; C = individual case reports from clinical journals; D = in vivo or in vitro models support associations; E = indirect evidence.

2Clinical utility, i.e., the actual usefulness/added value of the biomarker in clinical routine considering the defined context of use (i.e., clinical, research), diagnostic/prognostic yield (i.e., + = definite, - = uncertain), non-invasiveness (i.e., + = non-invasive, - = invasive) and accessibility (i.e., + = available in both primary and specialized care centers; - = access limited to some primary and specialized care centers or available only in specialized care centers).

3Reproducibility has been defined according to standardization and interoperability (i.e., + = established, - = unclear or not defined).

Fig. 2. Neuroimaging, neurophysiological and biofluid biomarkers for cognitive impairment in Parkinson’s disease scored according to the level of evidence (panel A), clinical utility (panel B) and reproducibility (panel C).

Panel A: all biomarkers had a B2 level of evidence (i.e., evidence from cross-sectional and longitudinal cohort biomarker studies)106. Panel B: clinical utility, i.e., the actual usefulness/added value of the biomarker in clinical routine considering the defined context of use, diagnostic/prognostic yield, non-invasiveness and accessibility with greenish/yellowish shades indicating higher/intermediate clinical utility, respectively. Panel C: reproducibility defined according to standardization and interoperability with greenish/yellowish/reddish shades indicating higher/intermediate/low reproducibility, respectively. APOE apolipoprotein E gene, BDNF brain-derived neurotrophic factor, CSF cerebrospinal fluid, CysC cystatin C, DMN default mode network, EEG electroencephalography, FT frontal lobe, HC hippocampus, Hcy homocysteine, ICF intracortical facilitation, MEG magnetoencephalography, NAcc nucleus accumbens, NfL neurofilament light chain, PET positron emission tomography, Qalb albumin quotient, SAI short afferent inhibition, SICI short-interval intracortical inhibition, WM white matter.

Discussion

The present study aims to identify diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers for CI in α-synucleinopathies using a multimodal approach based on a system biology perspective and coupling neuroimaging, neurophysiological, biofluid and genetic biomarkers. Twenty-five SRs with or without MAs on structural/functional neuroimaging, neurophysiological and biofluid biomarkers for CI in PD have been identified, while data on other α-synucleinopathies are largely lacking. We will discuss the results separately according to the diagnostic (i.e., SRs and MAs of cross-sectional studies) and prognostic (i.e., SRs and MAs of longitudinal studies) aim of the explored biomarkers.

We identified several structural and functional neuroimaging, neurophysiology, and biofluid diagnostic biomarkers of CI in PD.

Three voxel-wise MAs including structural neuroimaging studies provided converging evidence that CI in PD is associated to gray matter atrophy in a brain network including the insula, the superior and inferior temporal lobe, and the superior and inferior frontal lobe, with a predominant left side involvement in PD-MCI and bilateral atrophy in PD-D40,43,44. The involvement of frontal and temporal lobes is in keeping with the frequent impairment of executive and attention domains that can be documented since the early stages of PD38,57–59. At variance, the temporal involvement may correlate with the impairment of memory, which is frequently found later in PD course38,60,61. Striatal and insular dopamine denervation have been suggested to underlie MCI, and in particular executive dysfunction, in PD62. The bilateral gray matter atrophy in PD-D is in keeping with evidence of a unilateral-to-bilateral spread of dopaminergic cell loss in a genetic model of PD63, the clinical observation that onset of PD motor symptoms is usually asymmetrical, and early susceptibility of left hemisphere to cortical atrophy in PD64. Indeed, the predominant left-side atrophy in PD-MCI seems counterintuitive, as it would imply an involvement of language domain that is not commonly affected in early PD stages61. However, the left hemisphere is highly specialized for other complex abilities that may be affected by CI in PD, such as motor planning, organization of complex movements and actions, motor learning65,66. The cross-sectional design of the original studies however does not support direct evidence of unilateral-to-bilateral progression of gray matter atrophy in the frontal-limbic-temporal region associated to CI in PD.

In keeping with the role of the anterior insula as a crucial hub in the salience network that mediates dynamic interactions between other large-scale brain networks, such as the default mode network and the central executive network67, a voxel-wise MA of functional MRI studies documented reduced connectivity specifically in the default mode network39. The default mode network includes the medial parietal, bilateral inferior-lateral-parietal and ventromedial frontal cortex and plays an important role in various cognitive functions, including memory, processing speed and executive function, which are affected in PD-MCI68. Changes in the default mode network have been reported in PD69 and in several other neurodegenerative disorders such as AD, Huntington’s disease, and frontotemporal dementia39.

Structural and functional changes and their overlap in PD with CI were explored by a coordinate-based MA that confirmed larger gray matter atrophy, involving bilateral insula, in PD-D than PD-MCI but yielded conflicting results in PD-MCI, which showed structural alterations in somatosensory brain areas that do not overlap with functional changes in areas underlying executive processing38. A hypothesis to reconcile this paradoxical finding is that the somatosensory network functional deficit may not be visualized because the somatosensory brain areas in PD-MCI may have developed early structural atrophy70 with no functional imaging signal to be detected38.

The pattern of structural and functional neuroimaging and the neurophysiological changes associated with PD-MCI subtypes (i.e., according to the main cognitive domain involved) were examined in a SR that reported structural and functional changes in occipital, parietal, and temporal regions in amnestic PD-MCI, while non-amnestic and executive PD-MCI was mainly associated with functional neuroimaging and neurophysiological rather than structural abnormalities35. However, only few studies considered the cognitive variability of PD-MCI, and the conclusions are biased by the high heterogeneity of the included studies35.

Cortical amyloid deposition in CI associated to α-synucleinopathies was examined by a MA that reported higher amyloid deposition in DLB than PD-D, while PD-MCI subjects showed lower deposition than PD-D and DLB, with substantial variability in the findings37. Of interest, results in PD-MCI diverged from those in MCI associated to AD and in cognitively normal elderly controls, where the prevalence of amyloid deposition is reported to be larger71,72. Increased tau PET tracer binding was found in the entorhinal region in PD patients with CI in comparison to cognitively intact ones, but tau binding did not differ according to the degree of CI in PD52. The time course of amyloid and tau PET findings in relation to CI in PD differs to some extent from the classical AD findings73. These data suggest that PD-MCI may be more related to dopamine denervation and α-synuclein than amyloid deposition in comparison to PD-D and DLB, or that PD brain is less prone to amyloid deposition, at least in early disease stages37. Conversely, abnormal tau deposition appears to be related to CI in PD but is not associated to its severity, again pointing to the importance of coexisting α-synucleinopathy74.

Brain metabolism reduction was found to exceed changes in synaptic density in DLB/PD-D according to PET imaging studies36 suggesting the presence of additional functional changes that may be ascribed to a functional rather than structural damage related to α-synuclein, amyloid or tau proteinopathy.

A SR of quantitative EEG studies reported cortical rhythm slowing, which have been reported to reflect cortical neurodegeneration75 and degeneration of the cholinergic nucleus basalis of Meynert in AD and DLB76, and abnormalities in some connectivity measures in PD with CI compared to PD-NC, with data in PD-MCI ranging between those of cognitively unimpaired PD and PD-D33, while a SR of MEG studies yielded conflicting data on connectivity measures associated to PD-D32. Both reviews converge on insufficient evidence for the use of EEG and MEG connectivity measures as a biomarker of cognitive function in PD because of the small number of studies32,33.

SAI, a measure of cortical inhibitory cholinergic activity, was reported to be more impaired in PD with CI than PD-NC and its reduction was found to be associated to visuo-spatial, executive, and less strongly to memory, and attention deficits in PD in a MA42. Cholinergic dysfunction has been hypothesized to play a key role in the appearance of cognitive deficits in PD77. The “dual syndrome hypothesis” suggests that dopaminergic dysfunction in the fronto-striatal regions and cholinergic dysfunction within the posterior cortical and temporal lobes, the latter being more involved in early deficits in visuo-spatial function and semantic fluency and more rapid cognitive decline to dementia, contribute to CI in PD78.

Increased SICI and reduced ICF, which suggest enhanced cortical GABAergic and reduced glutamatergic activity, respectively, were reported to be associated with the severity of CI in PD47. These abnormalities, which differ from those typically found in PD irrespective of CI (i.e., reduced SICI and increased ICF that can be partially reverted by dopaminergic treatment) suggest the additional involvement of other neurotransmitter deficits or the bias effect of concomitant medications79.

The event related potential P300 is associated to visual perception, verbal fluency, working memory, and planning and its latency is related to cognitive processing and mainly reflects the time of stimulus evaluation80. A MA reported P300 latency to be prolonged in PD-D patients compared to PD-NC45. This finding is in keeping with a study that suggested prolonged P300 latency to reflect early changes in attention and cognitive processing81.

A SR and a MA on CSF biomarkers of CI in PD converged in reporting classical AD biomarkers (i.e., reduced Aß42, increased t-tau and p-tau) in PD patients with CI and especially in PD-D49,50, supporting a potential role of amyloid brain deposition as a core feature of CI in PD, in accordance with the neuropathological evidence of AD neuropathology in PD patients with advanced disease course and CI13,19,82.

Plasma homocysteine, a metabolic product of methionine, was found to be increased and plasma vitamin B12 and folate, which together regulate homocysteine methylation, were found to be reduced in PD with CI when compared to PD-NC in a MA51. Homocysteine has been suggested to exert neurotoxicity and contribute to vascular damage51, and increased homocysteine has been reported as a risk factor for AD and dementia83,84. However, the scenario appears to be more complex because of the intricate relationships between homocysteine, vitamin B metabolites, long-term L-dopa/dopa-decarboxylase inhibitor treatment, and PD motor and non-motor symptoms, and the lack of longitudinal studies ruling out a possible reverse causation relationship85. Serum levels of cystatin C, a cysteine protease inhibitor that regulates several biological processes, including matrix proteases activity, inflammation, and autophagy86, has been found to be increased in PD patients with MCI compared to PD-NC54. Cystatin C has been reported as a biomarker of motor progression and to correlate with NfL, an axonal damage marker, in PD86.

A MA explored CSF and blood biomarkers of blood–brain barrier disruption in α-synucleinopathies and reported significantly increased levels of serum NfL, suggesting axonal damage and increased CSF/serum albumin quotient associated with PD-D, lending some support to the presence of blood–brain barrier disruption in the pathogenesis of CI in PD55.

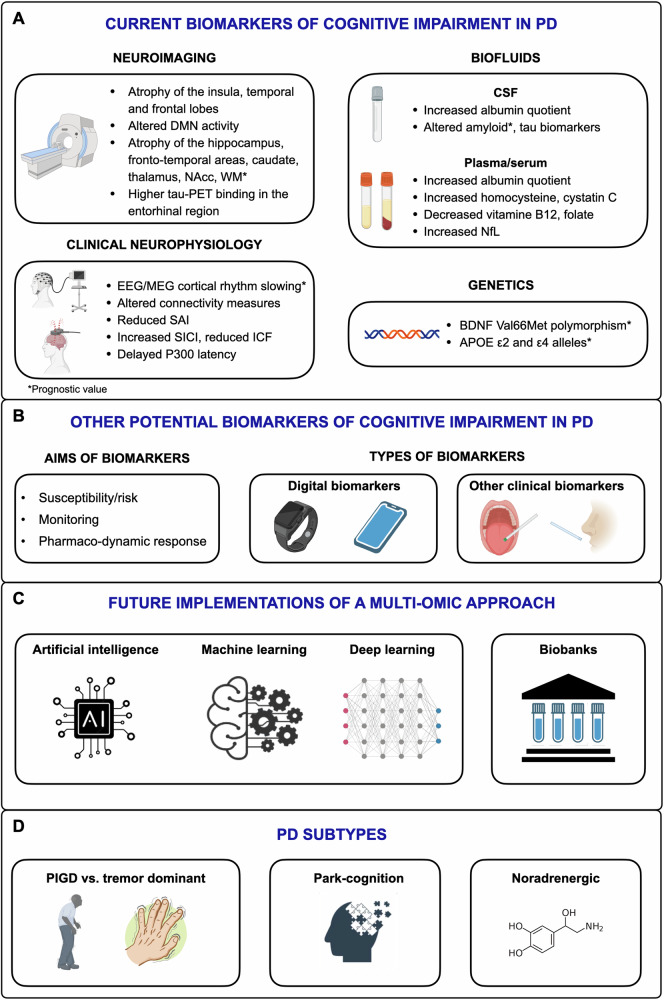

In summary, the reported diagnostic biomarkers of CI in PD include: a) atrophy of the insula, frontal and temporal lobes and to less extent the somatosensory areas, with more marked and more widespread/bilateral changes in PD-D than PD-MCI; b) functional changes in the default mode network and in areas underlying executive processing, with some mismatch between the areas undergoing structural and functional changes; c) abnormal cortical amyloid and increased tau deposition in the entorhinal region, and positive CSF amyloid and tau biomarkers, more marked in PD-D than PD-MCI; d) slowing of EEG and MEG cortical rhythm, with to less extent changes in some connectivity measures; e) reduced cortical inhibitory cholinergic activity documented by SAI measure; f) increased cortical GABAergic activity and decreased cortical glutamatergic and cholinergic transmission in PD-D than PD-MCI and PD-NC; g) delayed P300 latency; h) increased plasma homocysteine and cystatin C and decreased vitamin B12 and folate, with unclear pathophysiological significance; i) increased CSF/serum albumin quotient and serum NfL, suggesting blood–brain barrier disruption and axonal damage, respectively (Fig. 3). Biomarkers associated to CI subtypes have been seldom explored, with some evidence supporting more consistent structural neuroimaging changes in amnestic PD-MCI, and SAI cholinergic abnormalities to be more marked in PD patients with visuo-spatial and executive deficits.

Fig. 3. State of the art and opportunities and issues for future development of biomarkers for cognitive impairment in Parkinson’s disease (PD).

The overview of the literature yielded neuroimaging, neurophysiological, biofluid and genetic diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers with conflicting results and limited application at single patient level (panel A). Susceptibility/risk, monitoring, pharmaco-dynamic response, digital and minimally invasive clinical biomarkers should be tested in future studies (panel B). Artificial intelligence, machine and deep learning combined with large biobanks including traditionally neglected may implement a multi-omics approach that might be more informative in single patients (panel C). PD subtypes might be associated with different multi-omics fingerprints that may represent the basis for a personalized medicine approach to cognitive impairment in PD (panel D). This figure was partially created with Biorender.com. APOE apolipoprotein E gene, BDNF brain-derived neurotrophic factor, CSF cerebrospinal fluid, DMN default mode network, EEG electroencephalography, ICF intracortical facilitation, MEG magnetoencephalography, NAcc nucleus accumbens, NfL neurofilament light chain, PET positron emission tomography, PIGD postural instability gait disorder, SAI short afferent inhibition, SICI short-interval intracortical inhibition, WM white matter.

We identified some structural neuroimaging, neurophysiology, CSF and genetic prognostic biomarkers of CI in PD.

A structural MRI MA documented more marked and progressive whole-brain volume loss in PD patients with CI than PD-NC but did not report data on specific regions of interest41. A SR of MRI studies focusing on the hippocampus reported atrophy of hippocampal volume and hippocampal subfields over time as a potential prognostic biomarker for conversion from PD-NC to PD-MCI and from PD-MCI to PD-D34. These findings align with AD neuroimaging literature, which has similarly found reductions in hippocampal volume to predict cognitive progression and the 20–30% prevalence of AD pathology at post-mortem autopsy in PD patients87. Another SR on multimodal structural neuroimaging reported greater volume loss in several brain areas, including fronto-temporal areas, caudate, thalamus and nucleus accumbens and widespread white matter changes over time in PD-MCI30. Taken together, these figures indicate that various cortical and subcortical regions might play a key role in the progression of CI in PD.

Two SRs of quantitative EEG and MEG converged in reporting cortical rhythm slowing as biomarkers of cognitive worsening in PD even at single-subject level32,33. Changes in cortical oscillatory slowing activity are supposed to rely upon the involvement of brainstem dopaminergic, noradrenergic, and serotonergic projection systems in early PD32, while cortical Lewy body and tau pathology, degeneration of the cholinergic nucleus of Meynert and thalamo-cortical circuits pathology take place in later disease stages88,89 and may contribute to cortical neurophysiological changes in PD patients with CI.

SAI was reported to be abnormal in PD patients with CI, but the lack of longitudinal studies impedes any conclusion on SAI as a potential biomarker of CI progression in PD42. Similarly, P300 was found to be abnormally prolonged in patients with PD-D, but the absence of longitudinal studies on P300 and other event related potentials does not offer information on the role as potential predictor of CI evolution45.

In keeping with the data on CSF AD biomarkers for the diagnosis of CI in PD (see above), CSF Aß42 levels were reported to be good predictors of cognitive decline in PD and progression to PD-D in a SR of prognostic studies49.

Two MAs reported significant association with the BDNF Val66Met polymorphism and increased risk of CI in Caucasian populations with PD52,53. These findings are in keeping with the role of the BDNF gene product in dopaminergic neurons survival and differentiation, synaptic plasticity, and dopamine activity in the fronto-striatal circuitry53.

A MA on a wide range (i.e., clinical, neuroimaging, neurophysiological, biofluids, genetics) of prognostic biomarkers reported only APOE ε2 and ε4 alleles, reduced α and increased θ power to be associated with increased risk of CI in PD, while clinical, neuroimaging, CSF and other included biomarkers yielded negative findings56.

To summarize, the reported prognostic biomarkers of CI in PD include: a) atrophy of the whole brain and specific regions, including the hippocampus, fronto-temporal areas, caudate, thalamus, nucleus accumbens and white matter; b) cortical rhythm slowing that can be informative at single-subject level; c) CSF amyloid biomarkers; d) the BDNF Val66Met polymorphism and APOE ε2 and ε4 alleles (Fig. 3).

The main strength of this overview is that it offers an updated and comprehensive scenario on the state-of-the-art of diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers of CI in α-synucleinopathies, through an overview of SRs and MAs and a proposal of scoring based on evidence levels, clinical utility, and reproducibility.

There are several limitations with our findings. First, no SRs/MAs including patients with CI due to MSA were found, while only one SR included patients with CI due to DLB36. CI has been consistently reported as an important non-motor feature in DLB and MSA18, and further studies are warranted on diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers for CI in these conditions. Second, the diagnosis of PD-MCI and PD-D differed across the original studies included in the SRs and MAs that we examined, and only 8 out of 25 reports explicitly mentioned this as one of the main constraints33,35,39,45,46,52,55,56. Before the publication of diagnostic criteria for PD-MCI according to abbreviated or comprehensive assessment by a Movement Disorders Society task force24, the construct of MCI in PD was unclearly defined and older studies might differ in terms of MCI diagnostic criteria. Third, most of the original studies did not provide sub-scores for single cognitive domains or offer information on MCI subtypes, hampering the analysis of the association between single biomarkers and specific patterns of CI in most of the included studies. Fourth, many of the SRs and MAs we included were based on cross-sectional studies that offer diagnostic biomarkers of CI but does not allow the assessment of a direct causation effect between biomarkers and CI and cognitive decline. Indeed, data on prognostic biomarkers were less robust than diagnostic ones, in terms of the number of SRs/MAs and subjects included, and findings on susceptibility/risk, monitoring, and pharmaco-dynamic/response biomarkers of CI in PD are largely lacking. Fifth, some of the association between reported biomarkers and CI might have been at least partially biased by covariates such as age, sex, education, disease duration, pharmacological treatment, motor severity, other PD non-motor symptoms, but moderator analyses were performed only in 7/25 studies42–45,47,55,56. Finally, the original studies might have been affected by publication bias as this issue was assessed in only 16/25 MAs and SRs included32–35,37,39,40,45,47,50–52,54–56.

This overview reported updated evidence on diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers of CI in PD, offering a state-of-the-art based on SRs and MAs, together with a proposed scoring based on evidence levels, clinical utility, and reproducibility that might represent a starting point for assessing their clinical significance in terms of sensitivity, specificity and area under the curve for diagnosis and prognosis of CI in patients with α-synucleinopathies.

Future studies on biomarkers of CI in PD should consider the open questions on this topic (Fig. 3). First, they should include biomarkers of susceptibility/risk, monitoring of CI worsening, and those offering information on pharmaco-dynamic/response biomarkers27. Second, given they can be more easily applied, clinical biomarkers of CI should be tested in addition to more complex, expensive, and not widely available instrumental ones90. Third, the application of plasma/serum neurodegeneration/neuropathological biomarkers, instead of the more invasive CSF ones is an emerging field of study91. Promising results have been shown for plasma NfL, which has recently been reported as a sensitive biomarker for predicting cognitive decline in PD. According to two recent prospective studies, increased plasma NfL, but not p-tau181, was a better predictor of progression to dementia during follow-up in PD patients92,93. In this review we found only preliminary evidence on NfL and these data, although interesting, remain inconclusive. Fourth, studies should assess the significance of digital biomarkers27, an emerging topic in CI and dementia, in that they may offer the unique chance of being recorded remotely and in a more ecological home environment94. Fifth, the complexity of the motor and non-motor PD clinical subtypes that include the classical tremor-dominant and postural-instability-gait-disorder motor phenotypes95, but have consistently expanded in recent years, encompassing both non-motor symptoms and putative specific pathophysiological features96,97 should be considered. The large heterogeneity of findings in the included MAs might derive from an imbalance in PD clinical phenotype in the original studies. From this perspective, the combination of clinical features, biomarkers of abnormal α-synuclein deposition together with CI biomarkers might lead to a better PD subtyping based on clinical and biological features. Sixth, the increasing availability and the lower cost of biomarkers yield technical, analytical and standardization challenges that can be addressed by artificial intelligence, machine learning solutions, and digital twin technology to realize the full potential of a multiomics approach to CI in PD98–100. Large multicenter consortia and biobanks that include sex- and gender-balanced subjects and traditionally poorly represented minorities will be of paramount importance to address these issues.

Methods

Overview of systematic reviews and meta-analyses

This overview of SRs and MAs was performed following the recommendations for conducting umbrella reviews according to the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) methodology101, the Cochrane Handbook for SRs of Interventions102 and the principles of the Preferred Reporting Items for SRs and MAs (PRISMA) guidance103, where applicable. The review protocol was not registered.

Eligibility criteria

The SPIDER tool104 was used to frame the inclusion criteria for this overview. The Sample (S) included patients with α-synucleinopathies (i.e., PD/PD-D, DLB, MSA); the Phenomenon of Interest (PI) was the association between neuroimaging, neurophysiological, biofluid and genetic biomarkers of any type (i.e., diagnostic, prognostic, predictive, susceptibility/risk, monitoring, pharmaco-dynamic/response) and CI of any severity or degree (i.e., SCI/SCD, MCI, dementia); the Design (D) encompassed SRs with/without MAs clearly identified by the authors in either the title or abstract of the review and presenting evidence of a systematic search and process (i.e., duplicates removal, titles/abstracts screening, full-texts screening, data extraction and analysis) according to PRISMA guidance103; the Evaluation (E) was any neuroimaging, neurophysiological, biofluid and/or genetic measure that served as a biomarker; the Research type (R) included qualitative and quantitative peer-reviewed studies. Eligible SRs and MAs were included regardless the number or breadth of search engines used, the study design and methodology of the primary studies. SRs and MAs were excluded when comparing patients with CI vs. healthy controls (including normal aging) or other conditions due to different neuropathologies (e.g., AD), only.

Search strategy

PubMed/MEDLINE and Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews were searched to identify relevant articles published from databases inception to December 16th 2022. The following search string was used: (alpha synucleinopathies OR Parkinson’s disease OR “PD” OR Lewy body dementia OR “LBD” OR multiple system atrophy OR “MSA”) AND (cognitive dysfunction OR “cognitive impairment”) AND (biomarker) AND (magnetic resonance imaging OR “MRI” OR positron emission tomography OR “PET” OR single photon emission tomography OR “SPECT” OR electroencephalography OR “EEG” OR magnetoencephalography OR “MEG” OR evoked potentials OR transcranial magnetic stimulation OR “TMS” OR cerebrospinal fluid OR “CSF” OR blood OR plasma OR serum OR epigenomics OR proteomics OR genetics OR genomics). The search on PubMed/MEDLINE was filtered for reviews, SRs and MAs. Besides, the reference lists of relevant publications were manually inspected for any additional citation to ensure a comprehensive literature search. The search was updated on June 4th, 2024 to ensure currency of results.

Study selection

Search results were uploaded to Rayyan software, a web-based application to facilitate collaboration among reviewers during the selection of the studies105. Two authors (EM, ST) independently screened titles and abstracts. Any disagreement was solved by consensus.

Data extraction and management

A shared, previously pilot-tested data extraction sheet was created to record the following data from included SRs and MAs: study design (i.e., SR with/without MA), type(s) and number of included studies and participants, biomarker type according to nature (i.e., neuroimaging, neurophysiological, biofluids, genetics) and purpose of measurement (i.e., susceptibility/risk, diagnosis, monitoring, prognosis, prediction), cognitive dysfunction severity (i.e., SCI/SCD, MCI, dementia), group comparisons, main results and conclusions. Results pertaining comparisons between patients with CI vs. healthy controls (including normal aging) or other conditions due to different neuropathologies (e.g., AD) were not reported, as we were specifically interested on the association between biomarkers and CI in α-synucleinopathies.

Data analysis

A systematic and descriptive analysis of the results was reported in the text and tables.

Risk of bias

The JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist for Systematic Reviews and Research Syntheses was used to assess the methodological quality of the included SRs and MAs101. Quality assessment according to JBI checklist involves eleven domains: 1) clarity and explicity of the review question, 2) inclusion criteria, 3) search strategy, 4) adequacy of sources and resources used, 5) criteria for study appraisal, 6) number of reviewers, 7) methods to minimize errors in data extraction, 8) methods used for combined studies, 9) assessment of publication bias, 10) recommendations for policy and practice, 11) directives for new research. Every domain was given a rating of “yes”, “unclear”, “no” or “not applicable”, and one point was given to every domain rated “yes”. Based on the sum of points, the overall quality of the paper was judged as being low (0–4), moderate (5–8) or high (9–11). Two authors (EM, ST) performed the risk of bias assessment independently, and disagreements were solved by consensus.

Assessment of evidence levels, clinical utility and reproducibility

To provide guidance for prioritizing biomarkers for future research, we assessed and scored each biomarker that demonstrated diagnostic and prognostic value in terms of level of evidence, clinical utility and reproducibility106. The classification of level of evidence was stratified as follows: A = proven/consensus association in human medicine; B1 = prospective, randomized clinical trial; B2 = cross-sectional and longitudinal cohort biomarker studies; B3 = retrospective biomarker studies; C = individual case reports from clinical journals; D = in vivo or in vitro models support associations; E = indirect evidence. The definition of clinical utility was based on diagnostic/prognostic yield (i.e., definite or uncertain), non-invasiveness (i.e., invasive or non-invasive) and accessibility (i.e., availability in primary and/or specialized care centers). Finally, reproducibility was defined according to the presence/absence of standardized and interoperable protocols.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by funding from the University of Verona (Bando Joint Research 2021). Figure 3 has been partially created with a licensed version of BioRender.com.

Author contributions

E.M.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Data curation, Writing - Original draft preparation. A.M., A.D., C.Z., S.F., S.M., M.T.: Methodology, Data curation, Writing – Reviewing and Editing. S.T.: Conceptualization, Data curation, Writing – original draft preparation, Reviewing and Editing, Supervision. All authors critically revised and approved the manuscript.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Competing interests

All authors declare no financial or non-financial competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Elisa Mantovani, Email: elisa.mantovani@univr.it.

Stefano Tamburin, Email: stefano.tamburin@univr.it.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41531-024-00823-x.

References

- 1.Wong, Y. C. & Krainc, D. α-synuclein toxicity in neurodegeneration: mechanism and therapeutic strategies. Nat. Med23, 1–13 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Koga, S., Sekiya, H., Kondru, N., Ross, O. A. & Dickson, D. W. Neuropathology and molecular diagnosis of Synucleinopathies. Mol. Neurodegener.16, 83 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Uchihara, T. & Giasson, B. I. Propagation of alpha-synuclein pathology: hypotheses, discoveries, and yet unresolved questions from experimental and human brain studies. Acta Neuropathol.131, 49–73 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dugger, B. N. & Dickson, D. W. Pathology of Neurodegenerative Diseases. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol.9, a028035 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goedert, M., Masuda-Suzukake, M. & Falcon, B. Like prions: the propagation of aggregated tau and α-synuclein in neurodegeneration. Brain140, 266–278 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Savica, R., Grossardt, B. R., Bower, J. H., Ahlskog, J. E. & Rocca, W. A. Incidence and pathology of synucleinopathies and tauopathies related to parkinsonism. JAMA Neurol.70, 859–866 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weintraub, D. What’s in a Name? The Time Has Come to Unify Parkinson’s Disease and Dementia with Lewy Bodies. Mov Disord10.1002/mds.29590 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Poewe, W. et al. Multiple system atrophy. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim.8, 56 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Höglinger, G. U. et al. A biological classification of Parkinson’s disease: the SynNeurGe research diagnostic criteria. Lancet Neurol.23, 191–204 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Simuni, T. et al. A biological definition of neuronal α-synuclein disease: towards an integrated staging system for research. Lancet Neurol.23, 178–190 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barone, P., Erro, R. & Picillo, M. Quality of Life and Nonmotor Symptoms in Parkinson’s Disease. Int Rev. Neurobiol.133, 499–516 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bhatia, K. P. & Stamelou, M. Nonmotor Features in Atypical Parkinsonism. Int Rev. Neurobiol.134, 1285–1301 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aarsland, D. et al. Parkinson disease-associated cognitive impairment. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim.7, 47 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stankovic, I. et al. Cognitive impairment in multiple system atrophy: a position statement by the Neuropsychology Task Force of the MDS Multiple System Atrophy (MODIMSA) study group. Mov. Disord.29, 857–867 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cui, Y., Cao, S., Li, F. & Feng, T. Prevalence and Clinical Characteristics of Dementia and Cognitive Impairment in Multiple System Atrophy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Parkinsons Dis.12, 2383–2395 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mantovani, E., Zucchella, C., Argyriou, A. A. & Tamburin, S. Treatment for cognitive and neuropsychiatric non-motor symptoms in Parkinson’s disease: current evidence and future perspectives. Expert Rev. Neurother.23, 25–43 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martini, A. et al. Differences in cognitive profiles between Lewy body and Parkinson’s disease dementia. J. Neural Transm. (Vienna)127, 323–330 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Raimo, S. et al. The Cognitive Profile of Atypical Parkinsonism: A Meta-Analysis. Neuropsychol. Rev.33, 514–543 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Karanth, S. et al. Prevalence and Clinical Phenotype of Quadruple Misfolded Proteins in Older Adults. JAMA Neurol.77, 1299–1307 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Walker, L., Stefanis, L. & Attems, J. Clinical and neuropathological differences between Parkinson’s disease, Parkinson’s disease dementia and dementia with Lewy bodies - current issues and future directions. J. Neurochem150, 467–474 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gratwicke, J., Jahanshahi, M. & Foltynie, T. Parkinson’s disease dementia: a neural networks perspective. Brain138, 1454–1476 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Frouni, I., Kwan, C., Belliveau, S. & Huot, P. Cognition and serotonin in Parkinson’s disease. Prog. Brain Res269, 373–403 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van der Zee, S. et al. Altered Cholinergic Innervation in De Novo Parkinson’s Disease with and Without Cognitive Impairment. Mov. Disord.37, 713–723 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Litvan, I. et al. Diagnostic criteria for mild cognitive impairment in Parkinson’s disease: Movement Disorder Society Task Force guidelines. Mov. Disord.27, 349–356 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Donaghy, P. C. et al. Research diagnostic criteria for mild cognitive impairment with Lewy bodies: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Alzheimers Dement19, 3186–3202 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aronson, J. K. & Ferner, R. E. Biomarkers-A General Review. Curr. Protoc. Pharm.76, 9.23.1–9.23.17 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Coravos, A., Khozin, S. & Mandl, K. D. Developing and adopting safe and effective digital biomarkers to improve patient outcomes. NPJ Digit. Med. 2, 14 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Delgado‐Alvarado, M., Gago, B., Navalpotro‐Gomez, I., Jiménez‐Urbieta, H. & Rodriguez‐Oroz, M. C. Biomarkers for dementia and mild cognitive impairment in Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord.31, 861–881 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kalia, L. V. Biomarkers for cognitive dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord.46, S19–S23 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sarasso, E., Agosta, F., Piramide, N. & Filippi, M. Progression of grey and white matter brain damage in Parkinson’s disease: a critical review of structural MRI literature. J. Neurol.268, 3144–3179 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ryman, S. G. & Poston, K. L. MRI biomarkers of motor and non-motor symptoms in Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord.73, 85–93 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Boon, L. I. et al. A systematic review of MEG‐based studies in Parkinson’s disease: The motor system and beyond. Hum. Brain Mapp.40, 2827–2848 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Geraedts, V. J. et al. Clinical correlates of quantitative EEG in Parkinson disease: A systematic review. Neurology91, 871–883 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pourzinal, D. et al. Hippocampal correlates of episodic memory in Parkinson’s disease: A systematic review of magnetic resonance imaging studies. J. Neurosci. Res.99, 2097–2116 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Devignes, Q., Lopes, R. & Dujardin, K. Neuroimaging outcomes associated with mild cognitive impairment subtypes in Parkinson’s disease: A systematic review. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord.95, 122–137 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Visser, M., O’Brien, J. T. & Mak, E. In vivo imaging of synaptic density in neurodegenerative disorders with positron emission tomography: A systematic review. Ageing Res. Rev.94, 102197 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]