Abstract

Background

Shamanism is a spiritual tradition in which trance practitioners deliberately modify their state of consciousness to seemingly interact with an invisible world to resolve their community members’ problems. This review aims to provide a multidisciplinary overview of scientific research on shamanic trance.

Methods

The search was performed using PubMed and Google Scholar databases. Twenty-seven articles were found to be eligible, and their data were classified into four dimensions, namely, a) phenomenology, b) psychology, c) neuro-physiological functions, and d) clinical applications.

Results

These studies suggest that these trances are non-pathological, different from normal states of consciousness in terms of phenomenology and neurophysiology, and influenced by multiple personal and environmental variables. Furthermore, while trances may offer therapeutic potential, their scope should be approached cautiously, underscoring the need for rigorous studies to assess the effectiveness of shamanic approaches for complementary therapies.

Conclusion

Overall, shamanic trance and its potential benefits remain an intriguing and multifaceted area of scientific study, offering insights into the intersections of consciousness, spirituality, and possibly therapy.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12906-024-04678-w.

Keywords: Shamanism, Trance, Phenomenology, Psychology, Brain and physiological function, Clinical applications

Introduction

In the last few decades, scientists have been interested in consciousness and its modifications [1]. Non-ordinary states of consciousness (NSC) can be defined as changes in mental functioning, qualitatively different from ordinary waking consciousness [2–4]. Trance is a type of NSC. The term “trance” derives from the Latin transitus (a passage) and transire (to pass over), implying a shift to another psychic state [5]. As a general terminology, trance can be defined as a voluntary absorptive state of consciousness induced by an abrupt event that makes subjects lose their usual references, which modifies the way they perceive reality and leave them with an unusual, atypical, and transitory feeling [6]. Trance is thus characterized by narrowed awareness of external surroundings [7, 8], intense focus and a modulated sense of self [9].

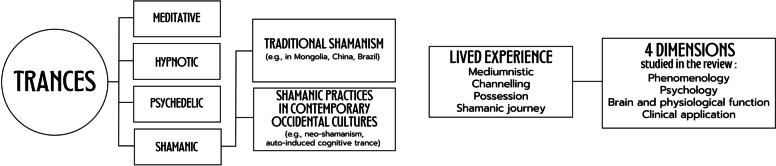

According to the way they are induced, we propose to distinguish four main trances: shamanic, meditative, hypnotic and psychedelic trances [10] (Fig. 1). Shamanic trance is originally experienced by shamans, also called a “State of Shamanic Consciousness” (SCC) by Harner [11]. During traditional rituals, shamans report reaching the spirit world in shamanic trance to help members of their community and solve their physical, psychological, and spiritual problems [12]. According to them, the aim of this trance is generally curative (diagnosis and treatment of illnesses), but it also seemingly allows shamans to accompany deceased persons’ souls to other realities, to locate animals for successful hunts, to solve problems encountered by members of the community and to predict future events [8, 13–19]. Generally, in shamanic trance, mental content emerges through symbols that make sense to the individual, which could lead to a better understanding of the problem [8]. Shamanism is believed to be the oldest spiritual tradition [20–22], nesting back from at least 20,000 to 30,000 years [23]. Supported by ethnographic evidence such as rock art sites, shamanism has been present in many areas of the world, such as central and northern Asia, the two Americas, Southeast Asia, Oceania, India, Tibet, China, Africa and among certain Indo-European peoples [23–26]. Despite geographical or temporal differences and distinctions related to the specificities of different cultures, the practices, techniques, and basic beliefs involved are surprisingly similar [11, 20]. Shamanic trance is a generic notion encompassing several techniques that have one thing in common: they are all induced by a shamanic inductor such as percussions, sounds, repetitive movements, dances, songs, chanting, prayers (e.g., mantra recitation), prolonged postures, sensory restriction or overload, fasting, and psychedelics (i.e., psilocybin, ayahuasca, peyote) [23, 27–31]. Repetitive drumming is a widespread technique in many shamanic traditions [11, 32]. During rituals, the shaman acts with theatrical and coded behaviors, such as the use of costumes, symbolic objects, or offerings to the spirits. The main figure of the ceremony also uses symbolic phrases and incantations [21, 33].

Fig. 1.

Proposed framework for trance research: Trance categories with a specific focus on shamanic trances, their lived experience and the four dimensions studied in this review

Meditative trance is defined as a group of “states, processes, and practices that self-regulate the body and mind, thereby affecting mental and physical events by engaging a specific attentional set” [34]. Meditation is used to improve voluntary control over mental processes. While meditative techniques are numerous, they present many similarities, such as a quiet location with few distractions, a specific posture, a focus on attention, and an open attitude of letting thoughts come and go without judgment [35].

Hypnotic trance can be defined as a process involving a modulation of self-awareness [36, 37], “focused attention and reduced peripheral awareness characterized by an enhanced capacity for response to suggestion” [38]. This trance is defined by four main components: absorption (ability to fully engage in a perceptive or an imaginative experience), dissociation (splitting of mental processes and bodily awareness and perceptions), suggestibility (tendency to comply with suggestions and to exhibit reduced critical thinking) [39], and automaticity (altered sense of agency, which is lived as a non-voluntary response to a suggestion) [40].

Psychedelic trance is induced by psychoactive substances. During this type of trance, perceptions change, but people are aware that they are in another reality [41]. At standard doses, psychedelics improve thought consistency and mood regularity and do not cause persistent mental confusion or memory impairment [42].

Several studies have reported some clinical benefits of hypnotic, meditative and psychedelic trances on pain, emotional regulation, sleep, fatigue, stress, cognitive difficulties and quality of life [43–48].

The distinction between these trances is necessary because they sometimes seem to overlap. For example, the use of psychoactive substances, which is originally used in many shamanic practices, is for some people automatically associated with shamanic trance, but it is far from being systematic [49]. Eliade, the historian of religion, described their use as an “aberrant technique and a vulgar substitute for the pure trance” [49]. According to Perrin [50], not using psychedelics in several societies is considered as a sign of great mastery and a great shaman.

While proposing a revision of (dis)similarities between these trances is a scientific necessity, the goal of this scoping review is to zoom-in on the shamanic trance with no psychedelic substances use. The term shaman, from “šamán” meaning “one who knows” [51], needs also to be specified. This terminology finds its origins from the tungus of Siberia and emerged in the intellectual circles of Europe with Russian scientific expeditions into Siberia in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries [26, 52]. In their society, shamans are people among thousands chosen by the spirits and are considered guides [17, 23, 26, 30]. They generally experience in their youth a specific trance that is considered as the initial “shamanic call” of future shamans, which would reveal capacities to easily experience a shamanic trance, or as a defense mechanism against a difficult situation or an offense of the spirits [53, 54]. This offers them a particular status with an immediate and integrative response from society [28, 53–56]. They are usually called upon by people in difficulty, the “consultants”, to help them with traditional rituals [57, 58]. To address their responsibilities, shamans self-induce a trance and report a special connection with the element of nature and animal spirits, with an invisible world [23, 26, 30, 59], and interconnected with the human world. They seemingly obtain information inaccessible in an ordinary state of consciousness to solve the consultant's problems [5, 8, 22]. At the end of the trance, the shamans return to the consultants to give them therapeutic advice [21]. In their trances, which are always voluntarily self-induced, shamans can experience different kinds of lived trances. We propose to distinguish 4 of them: mediumistic trance, channeling trance, possession trance and shamanic journey (Fig. 1). Note that most of the information about these trances is based on what individuals practicing these types of trance think about such states.

First, in a mediumistic trance in traditional shamanism, shamans report interacting with the spirit of a deceased person or other non-material person [60]. The shamans would “summon spirits to diagnose and cure illness, to divine the cause of a death and to reveal courses of action open” to their consultants [28]. Some argue that shamans may be disentangled from mediums, as the latter think that their role is only to inform the best they can the consultant. For example, MacDonald [28] said that mediums are the instruments taken over by the spirit whereas shamans are the masters of spirits who “restore the relationships, which prevail among people, land, and spirits”. However, to date, the distinction between medium and shaman is still debated.

Second, channeling trance involves both spiritual communication and spirit possession [61]. There is no unanimous definition, and we will quote the one used by Wahbeh and colleagues: channeling trances correspond to NSCs in which a “physically embodied human being voluntarily connects through a channel to a source of information that would exist outside the normal world” [61]. This dimension would come from some other levels or realities than the physical one as we know it. Trance channelers report to “use their bodies as vehicles for the purported disincarnate being to incorporate into and to communicate directly by speaking or movement” [62]. Channeling was given many names in history, such as prophecy, oracle, spiritual communication, and spirit possession [61].

Third, shamans also report that they can be possessed. Possession trance would be experienced by individuals where a new identity attributed to the influence of a spirit or deity replaces the usual identity [63]. In traditional cultures, spirit possession is a trance experienced in mediumship and shamanism. In many traditions, members of a community might also be possessed. For instance, in Javanese culture, dancers called kuda lumping keep performing their dance until the spirit or endang (the king of horse) seemingly enters their body [64]. Regardless of social status, people who report experiencing possession trances all describe a temporary inability to control their body and a loss of identity [65].

Fourth, shamans believe they can access the power they are given by spirits to undertake shamanic journeys on behalf of the members of their community who request help [28]. Their soul would be allegedly able to leave their body and go on a spiritual journey in “a threshold between life and death, between the world of the living and the world of the dead” [5]. The shamans report to usually use drumming to directly experience the journey and meet up with their own helping guides. From an emic perspective, shamans considered that these spirits unlock answers to difficult personal questions, mobilize energy for reaching goals in everyday life, reconnect with nature and restore balance and harmony in the consultants’ lives and on the planet [66]. The human soul is perceived as the vital essence needed for life and can “split away” following a trauma. Shamans then help their consultants find these lost essences and bring them back to make them “whole” again and cure them [67]. Shamanic journeys can also be interactive. In contemporary therapies derived from shamanism, guided shamanic journeys are proposed to enable individuals to actively engage in their own well-being. The shamanic practitioner enters an NSC using vocals, drumming, rattling and narrating the journey out loud to bring their consultant along the “shamanic journey” to presumably restore their wholeness [17].

In the last four decades, Western culture has shown a growing interest in shamanism, which has led to the transformation of practices inherited from traditional cultures into practices without any traditional ritual features and accessible to everyone. These techniques, usually called “neo-shamanism”, are considered a spiritual way of life. Those practices foster personal and communal empowerment through different trainings allowing most people to induce the trance voluntarily [68, 69]. Michael Harner is a central figure who contributed to the development of this philosophy. In 1985, he founded the Foundation for Shamanic Studies in the United States of America to preserve, understand and transmit the techniques of shamanism, which he called “core-shamanism”. He created a training and internship framework intended for anyone feeling the shamanic call. His method is induced by a specific rhythm, using drums without the use of psychoactive substances [11]. Corine Sombrun has more recently developed the auto-induced cognitive trance (AICT), which is inspired by a traditional Mongolian tradition. AICT is a standardized practice that has no traditional ritual or cultural expression. Individuals can reach this state after 4 days of training [70]. This trance is induced first through the listening of sound loops (which consist of binaural sounds with pure tones between 100 and 200 Hz and beating rates lower than 10 Hz combined with serial music sequences and voice sounds). Participants are quickly encouraged to let the trance manifest itself through any manifestation (e.g., vocalizations, movements, yawn, sudden feelings of warmth or cold, eyelid fluttering, eye movements) [71]. While Harner and Sombrun are among the most known involved in the development of Western practices derived from shamanic practices, many other experts are developing similar techniques.

Given the recent interest in the potential implications of these trance techniques, we intended to draw a comprehensive overview of the scientific research on traditional shamanic trances and neo-shamanic trances (i.e., contemporary occidental shamanic trances). This scoping review is the first to offer a multidisciplinary overview of these trances, and we propose to focus on four dimensions, namely, a) phenomenology (i.e., subjective experience of individuals), b) psychology (i.e., psychological processes involved), c) brain and physiological functions (i.e., objective overview of cerebral and biological functioning), and d) clinical applications (i.e., benefits of shamanic trances on various symptoms and pathologies) (Fig. 1).

Materials and methods

Search strategy and information sources

We conducted a literature review based on the guidelines provided by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) [72]. A scoping review approach was chosen given that our aim is to offer an overview of the phenomenological, psychological, brain and physiological functions as well as clinical applications of shamanic trance and trance practices derived from shamanism. The search was performed using PubMed and Google Scholar databases. A tailored search strategy was developed for each database according to their thesaurus characteristics. Both databases and relative keywords were chosen following consensus among authors. In PubMed, we performed 3 searches, Shaman*, Shamanic Trance, and Trance, and selected similar articles proposed by the database. In Google Scholar, we used the exact keyword “Shamanic Trance”. The search was initially performed in September 2020 in each database. A second identical search was repeated in September 2022 to identify additional latest studies. The paper selection was restricted to articles about shamanic trance and practices derived from shamanism, written in English and dealing with Humankind only. Studies were excluded if they came from a book, a magazine or a monograph.

Screening and eligibility criteria for each step

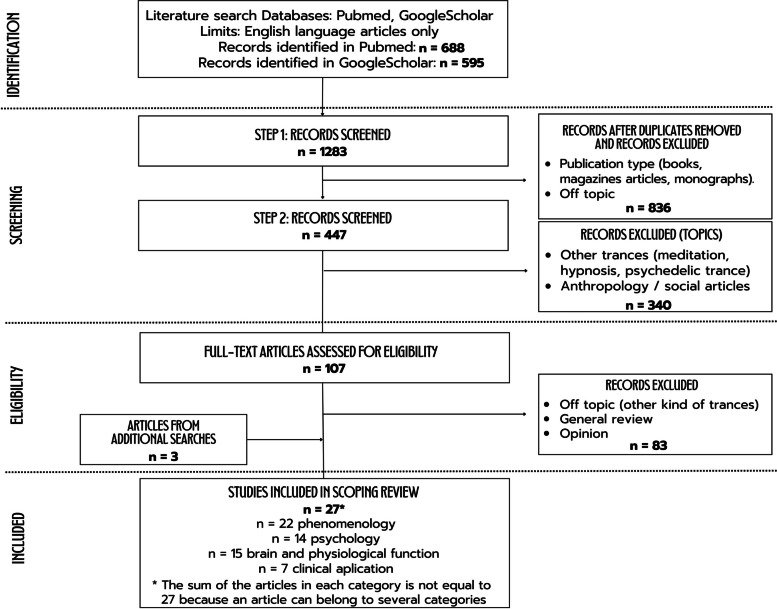

A three-step procedure was used, as illustrated in Fig. 2. The first step consisted of a screening of titles and abstracts. One rater (YL) screened all the 1283 articles provided by the two databases by title, abstract, and keywords to select articles about trances and shamanic trance specifically, with a focus on medical, biological, phenomenological, psychological, neurological, clinical, social, and anthropological articles. In this first step, 836 articles were excluded as they were coming from other publication types than articles (books, magazines or monographs), or were unrelated to trance phenomena. So, 447 articles were selected out of 1283.

Fig. 2.

Flowchart of the literature search process

In the second step, we downloaded the 447 full-text articles and exported them in web-based bibliographic management software: Rayyan [73]. Due to the large number of publications stemming from step 1, we decided to focus on articles about shamanic trances (both in traditional and current occidental cultures) and to exclude papers meeting the following criteria: (1) meditation, (2) hypnosis (without excluding articles investigating individual hypnotizability in shamanic trance practices), and (3) psychedelic trance. We decided not to include articles on psychedelics because even if these substances may potentially accelerate the process to reach a shamanic trance, our aim was to focus on induction without any drugs. Articles about social and anthropological topics were also excluded. Then, three raters (YL, AV, OG) blindly screened the abstracts of these articles. Four possibilities occurred: 1) all three raters agreed to reject the article: the article was rejected, 2) all three raters agreed to include the article: the article was selected, 3) two of 3 raters thought that the article should be rejected, and 4) two of 3 raters thought that the article should be included. In the last two cases, a consensus was reached for each article after unblinded review of the concerned articles among the three raters. At the end of this step, 107 articles were selected.

In the third step, we split all 107 articles extracted during step 2 into 4 groups (YL–OG, AV-CG, AB-FR and NM-AB) for final eligibility and data extraction. To do so, each pair of raters had to read 26 or 27 articles in full. When both members of the same group could not find an agreement, a rater from another group had to fully read the article to help decide if the article was relevant or not. Twenty-four articles were selected at the end of Step 3. In September 2022, three new articles were included [70, 74, 75]. In total, twenty-seven original articles were eligible for this review (Table S1 in Additional file).

Outcome measures

Before beginning the review process, we developed a working thematic grid, with standardized table entries, to ease the extraction of specific information for each article: the article data (title, author name, year of publication, category and type), the definition or description of 4 concepts (i.e., shaman, shamanism, trance and ritual) proposed by the authors, if present, the induction technique used to enter the trance, the study’s aim(s), the participant(s) data (number, age, sex, nationality, religion, occupation, presence of pathology if any, expertise level regarding trance practice), the study localization, the methods used (summarized protocol, scale, measures), the results (phenomenological, psychological, brain and physiological functions, clinical applications, others), the conclusions, the presence of supplementary material (yes/no), the limitations (reported in the article or from our own critical thinking), and additional references possibly relevant for our purpose. The last two columns were dedicated to the comments of the raters and the final decision to keep or reject the publication.

Main dimensions analyzed

We focused on four dimensions while reviewing the articles: phenomenology, psychology, brain and physiological functions, and clinical applications. The phenomenological dimension described the shamans’ or other participants’ subjective experiences during trance. The psychological dimension identified the psychological processes underlying trances. The neuro-physiological functions characterized the biological and cerebral functioning related to trance. The clinical applications reported the potential benefits on various symptoms and pathologies.

Results

To see a detailed summary of all selected studies, refer to Table S1 in Additional file. All available information on shamans, inclusion and recruitment is mentioned in Table S1 in Additional file.

Phenomenology studies

Although trances share common points, we investigated the different experiences reported depending on the type of trance. In the context of shamanic journeys, a study investigating different phenomenological domains by questionnaire highlighted 8 domains reported by shamans during drumming: complex imagery, experience of unity, spiritual experience, state of happiness, disembodiment, insight, elementary visual alterations, and altered perceptions (N = 37) [22]. Other studies based on free speech similarly reported an increase in internal and external awareness (N = 1) [74], a modification of perception and awareness of the body (e.g., mental imagery, sensation of floating, communication with entities, reliving traumatic experiences from a new perspective/better understanding of life/disease) (N = 15, N = 4) [15, 19, 74], visual and auditory hallucinations (N = 30) [14], bodily manifestations (rapid fluttering of the eyelids, accelerated breathing, feeling of dizziness, buzzing head, heaviness, modification of heart rate) [4, 15, 74], and a mystical experience (feeling of ecstasy) (N = 1) [29, 74].

Possession trance was evaluated from subjective and inter-subjective point of view. First, trance experts from different temples reported during free recall bodily manifestations such as less body control (e.g., unable to move or speak, rolling the head, trembling, zigzag walking, falling to the ground), unintelligible language (N = 8, N = 1) [75, 76] or even vomiting when they interpret that a spirit was about to enter the body [76]. Participants also reported changes in body perception and awareness (e.g., change in body temperature, access to information from elsewhere, communication with alleged entities) [75, 76], mystical experiences (e.g., changes in the embodied experience of the self) [75], or a feeling of emotions such as joy and euphoria after the experience (N = 24) [77]. These manifestations were accompanied by observations from external evaluators who observed the participants in trance and highlighted sudden excitement marking entry into trance, staring and/or unfocused eyes, masked expression, muscle rigidity/limb stiffness, tremors/convulsions, repeated automatic movements, falls and loss of consciousness, as well as stiffening and tremors of the limbs (N = 24, N = 3, N = 12) [77–79]. Finally, all studies reported post-trance amnesia by participants [75–79].

For channeling and mediumistic trances, the practitioners reported that they used their own body as a “vehicle” so that the so-called disembodied “being” or “entity” could incorporate and communicate directly through speech, writing or movement (N = 13). Half of the participants reported having the impression of being in trance with the same being/entity throughout the experience [62]. Furthermore, these types of trance seemed to be deeper for experts (with an average of 37 years of practice) compared to less experts (with an average of 16 years of practice) (N = 10) [80]. Experts in psychography (involving the transcription of spirit messages by the hand of the medium) also reported partial or even complete amnesia of written content compared to fewer experts who reported that the content was dictated to them [80]. Writing content was more complex during trance than in ordinary consciousness among experts [80]. At the emotional level, experts in trance reported an increase in surprise and happiness during trance on the positive and negative affect scale (N = 16) [60, 81]. Furthermore, in free recall, expert participants reported auditory and visual hallucinations, modified perception and changes in body consciousness (e.g., sensation of being outside one's body, telepathy) [60, 80]. Finally, the verbal or written content produced during channeling generally concerned ethical principles, the importance of spirituality and the rapprochement between science and spirituality [80].

Finally, a single case of an expert in AICT reported an increase in arousal, absorption, dissociation, and a decrease in time perception on visual analog scales [82]. In the context of free recall, this expert reported modified perception and changes in body consciousness (e.g., increase in muscular strength, decrease in pain, change in body temperature, perception of dissonance, possession, change in breathing, modification of the perception of time and space), hallucinations (visual and auditory), bodily manifestations (e.g., trembling, protolanguage, production of songs) and mystical experiences (e.g., ego dissolution, feeling of inner peace, intense joy) [51, 82].

Overall, major common phenomenological characteristics can be highlighted for all types of trance: (a) modification of internal and external consciousness (e.g., increased absorption, amnesia, dissociation); (b) modulated somatosensory perceptions (e.g., hallucinations, modified perception and changes in body consciousness, mental imagery), (c) alteration of agency (i.e., movements and thoughts felt to be automatic or out of control such as trembling, possession, and protolanguage), and (d) emotionally intense or even mystical (e.g., dissolution of the ego, sensation of being outside one's body).

Psychological studies

Two trends were found in these categories, namely the factors that can influence the experience during trances and the question of psychopathology in expert participants.

Psychological factors

First, some authors tested the influence of suggestions on the subjective experience of the trance. A study on 39 novices (no trance experience) showed that when they listened to repetitive percussions with instructions for shamanic journeying, they had a greater likelihood of experiencing subjective states such as heaviness, dreamlike states, and a subjective decrease in heart rate compared to participants listening to the same repetitive percussions with instructions for relaxation [4]. Nevertheless, another study with 24 novices showed no difference between the suggestion group (text containing a suggestion that they may experience a trance during the drumming) and the control group (text referring to percussion, but no trance effect was mentioned) on the altered experience scores [83].

Paranormal and supernatural beliefs as influencers of trance states are still debated. Polito and colleagues [3] studied the beliefs of 55 participants (with 80% first experiences) attending a sweat lodge ceremony led by a shaman. If the total altered state of consciousness score did not correlate with any of the preexisting paranormal belief scores, paranormal beliefs in the dimensions of psi (e.g., mind reading is possible), spiritualism (e.g., when in altered states, such as sleep or trance, the spirit can leave the body), and precognition (e.g., dreams can provide information about the future) were positively correlated with ego dissolution scores. Since the paranormal beliefs score was not a significant predictor of the overall intensity of the experience, the authors hypothesize that there was a greater tendency for individuals with these paranormal beliefs to interpret these changes as experiences of ego dissolution. Supernatural beliefs were also reported as apparent in only one-third of 30 shamanic trance experiencers derived from Harner [11, 14].

Personality traits were also explored in a study that showed a positive relationship between alexithymia (involving the inability to distinguish between inner feelings and their associated body sensations [84]) and trance intensity. More particularly, the results suggested that one of the dimensions of alexithymia (i.e., “difficulty identifying feelings”) predicts the intensity of trance on two dimensions (“oceanic boundlessness”, i.e., positive experiences of ego dissolution and loss of boundaries; and “visionary restructuralization”, i.e., hallucinations and illusions as well as changes in the meaning of objects) [3]. Two hypotheses were put forward by the authors to explain these results, namely, that people with alexithymia have a greater ability to dissociate and therefore to enter a trance or that they would be more able to extract themselves from the emotional experience and therefore focus on the sensory inputs of the experience [3].

Finally, hypnotizability, which is the individual's ability to experience suggested changes in physiology, sensations, emotions, thoughts, or behavior following suggestions during hypnosis [38], has been studied in regard to the shamanic trance experience. One study found that participants with a higher hypnotizability score were more likely to have a drum-induced shamanic trance experience (i.e., change in somatosensory perceptions, time and space alteration, greater dissociation or impression of becoming an animal) and to experience a greater intensity of trance than participants with a lower hypnotizability score (N = 169 psychology students) [85].

Psychopathology

The question of psychopathology among expert practitioners of shamanism has been the subject of numerous psychological debates. As part of an analysis of a preexisting database aimed at studying the impact of torture on Bhutanese refugees, a cross-sectional study focused on the epidemiology of mental disorders among self-reported shamans. The results indicated that these self-reported shamans (N = 42) did not differ significantly from the other Bhutanese refugees (N = 532) over the past 12 months and lifetime in terms of major depressive episode, specific phobia, persistent somatoform pain, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), generalized anxiety disorder, or dissociative disorders [16]. Second, in 2022, Lee & Kirmayer [75] recruited 8 male shamans to assess their mental health using interviews and standardized questionnaires. These authors highlighted emotionally stable, internal locus of control, confident, family oriented, and sociable individuals. Additionally, the Dissociative Experience Scale [86] indicated that although shamans’ scores were generally below the pathological threshold of 30, their scores were higher than the average scale’s scores found in Western and Chinese general populations, without causing clinically significant emotional distress. Thematic analysis of their experiences suggested that the therapeutic transformation of shamans initially undergoing spontaneous possession trances toward a role of shaman accepted by the community can be explained by (1) a change in identity and social role, (2) changes in self-perception during spirit possession, and (3) more lasting changes in the sense of self. Similarly, another case study suggested that it would be the feeling of control over the possession trance, moving from spontaneous possession to voluntary possession induced by rituals, that would promote the positive adaptation of shamans [76]. Furthermore, numerous other studies mentioned an absence of psychopathological symptoms in such experts (e.g., no abnormal behavior, dissociative or psychotic symptoms) [51, 60, 62, 78–80, 82].

Brain and physiological functions

Electroencephalographic studies

Nine studies reported electroencephalographic (EEG) findings during trances (Table 1). The first case study conducted with an expert in Korean shamanistic dancing (Salpuri dance) showed an increase in alpha1 and theta band activity in the frontal and occipital regions as well as a decrease in generalized frequency (Phi) during the Korean shamanistic trance [29]. Two other studies carried out on people judged to be in a possession trance by external observers (1 among 3 people [78] and 7 among 12 [79]) also showed an increase in alpha1, alpha2 and theta waves with a predominance of alpha2 found in the occipital region during trance [78] and a maintenance of the alpha2 frequency bands a few minutes after the trance, highlighting the temporary residual aspect of this state [79]. The authors suggested that the increase in alpha band activity was linked to a deactivation of the cerebral cortex and the activation of deep cerebral structures, such as the thalamus and the brainstem [78, 79], as well as the reward-generating neural network. This could explain the feeling of well-being associated with this state as well as the decrease in ordinary perception and memory during the trance experience [79]. Kawai and colleagues [79] also found an increase in the beta frequency band during trance.

Table 1.

Electroencephalographic findings of trances

| Frequency bands | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alpha | Beta | Thêta | Gamma | Others | ||

| EEG Studies |

Salpuri Dance (1 study, N = 1) |

↑ power (alpha1) [29] |

NDR |

↑ power [29] |

NDR |

↓ generalized frequency [29] |

|

Possession trance (3 studies, N = 28ab) No effect was found for Wahbeh et al., 2019 [62] |

↑ power (alpha1 et 2) |

↑ power [79] |

↑ power |

NDR | NA | |

|

Shamanic Trance (3 studies, N = 76a) No effect was found for Hove et al., 2016 [8] |

↓ power [76] ↓ connectivity [22] |

↑ criticallity ↑ connectivity [22] |

NDR |

↑ power ↓ complexity [22] |

NA | |

|

Auto-Induced Cognitive Trance (2 studies, N = 1b) |

NDR |

↓ right hemispheric coherence ↑ left hemispheric coherence ↑ anteroposterior coherence [51] |

NDR | NDR |

Modification of inter-hemispheric connectivity [51] ↑ amplitude of evoked potentials in frontal stimulation ↓ amplitude of evoked potentials in parietal stimulation [82] |

|

Legend: ↑ = increase, ↓ = decrease

NDR No difference reported, NA Not applicable

aincluding the control group

bpossible patient overlap in our table cannot be excluded

Conversely, a study showed a decrease in the alpha frequency band in the occipital lobe in a group of naive participants who listened to the drum combined with suggestions of experiencing a shamanic trance compared to the group who listened to the drum without any suggestion (N = 24) [83]. Decreased power in the alpha frequency range combined with low scores on the arousal subscale of the Phenomenology of Consciousness Inventory [87] was linked to a greater relaxation for the group that received suggestions [83]. A decrease in alpha band connectivity and an increase in beta band connectivity were also observed in 18 shamanic trance experts when listening to both shamanic drumming and classical music compared to the control group (listen to the same sounds without entering in trance). This may reflect a practitioner-related trait rather than a brain state specific to shamanic trance [22]. Moreover, an increase in the criticality (i.e., optimal point between neural order and disorder) of the low beta band and an increase in gamma band power were found in trance experts while listening to drum music. This was found to correlate positively with visual alteration for gamma and low beta bands and with the visualization of complex images for low beta bands (N = 37) [22]. A decrease in gamma complexity (i.e., neural signal diversity) was also found to be inversely correlated with insightfulness during drumming in these subjects [22]. However, gamma waves could also reflect artifacts caused by body movements. Furthermore, although components of alpha and theta activity were identified, analyses revealed no difference in alertness between the trance and non-trance states in 15 shamanic trance experts [8]. In addition, the hypothesis that the 4 Hz rhythm of the drum could induce a similar ∼4 Hz (theta) rhythm in the brain, as such “auditory excitation” of brain rhythms, was proposed as a mechanism for inducing trance, but it could not be verified as there were no differences in theta power.

A transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS)-EEG study conducted with an expert in AICT showed an increase in the amplitude of TMS-evoked potentials during frontal stimulations and a decrease in cortical excitability during parietal stimulations compared to the ordinary state of consciousness [82]. This increased activity observed during frontal stimulation could be related to the trance experience characterized by focused attention on internal stimuli or to the increased activation of premotor regions induced by mental imagery of movements and sounds. In contrast, the decreased amplitude of TMS-evoked potentials during parietal cortex stimulation could be related to a decrease in external awareness. Furthermore, another case study on the same AICT expert using EEG showed a modification in the interhemispheric connectivity, reflecting a shift from left anterior prefrontal activity to a dominance of the posterior right hemisphere [51]. The involvement of beta frequency bands was also found in this expert during trance with a decrease in right hemispheric coherence and an increase in left hemispheric coherence [51].

Nevertheless, substantial differences are not always observed in EEG power as shown during channeling trance among 13 experts despite a significant decrease in voice valence (= negativity), power of voice (dB/Hz) and subjective perception of a change in state reported by the participants [62].

If psychological studies showed an absence of psychopathology in people practicing trance, neurophysiological and neuroimaging results confirm this finding. No neurophysiological signs, such as epileptogenic signatures, rhythmic paroxysmal discharge or decremented electrical patterns, were observed in any of the participants [78, 79, 82], which tends to invalidate certain hypotheses that shamanic trance is a neurotic or psychotic state [16]. These results are in line with participants’ reporting, namely, the ability to enter and exit trance. Prospective randomized studies are nevertheless needed to better understand the neurophysiology of the shamanic trance and perhaps identify the neuronal signatures of different types of trances.

Functional magnetic resonance imaging and single photon emission computed tomography

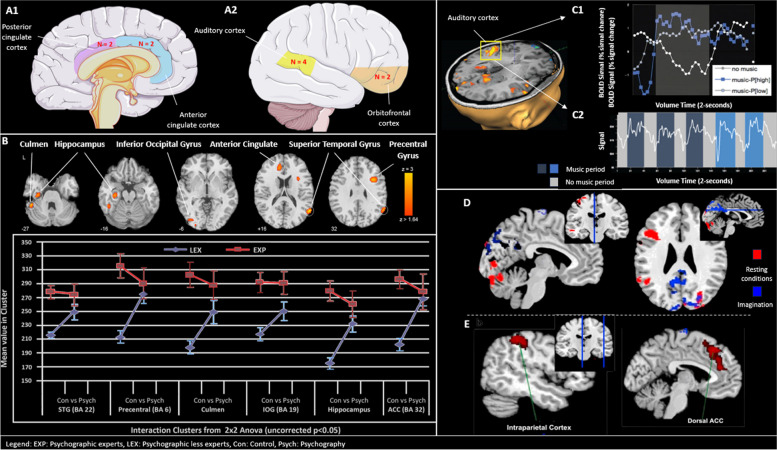

We found four studies (2 mediumistic and 2 shamanic trances) conducted with functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI, 3 studies) and single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT, 1 study) on trances.

The SPECT study with 10 expert mediums in psychography (divided into 2 groups, expert vs. less expert) found that experts showed higher activity levels during the control condition than less experts (Fig. 3B). Additionally, experts showed decreased activity levels during the psychography trance compared to less expert during the psychography trance, who showed an increase in activity in various cortical and subcortical areas (i.e., left culmen, left hippocampus, left inferior occipital gyrus, left anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), right superior temporal gyrus, and right precentral gyrus) (Fig. 3B). The decrease in activity in these regions during trance supports their subjective reports of ignoring written content during psychography, which may be related to a certain automaticity of thought. In addition, the 5 expert mediums found their trance less controllable than that of the less expert. The complexity of the written content produced during the trance was assessed using an analytic assessment [88]. There was a negative correlation between the change in complexity score for written content and the change in regional cerebral blood flow in each of these regions, which aligned with the notion of automatic writing and their claims that an “external source” was planning the written content. At the same time, the average complexity scores for content written in trance were higher than for content written during the control task for both expert and less expert mediums. The lack of recruitment of planning-related (frontal) areas and more complex written content during psychography is not consistent with the hypothesis of possible simulation or role-play during trance [80]. Conversely, another study highlighted an increase in the ACC and other brain areas (insula and posterior cingulate cortex (PCC)) during trance in 15 shamanic trance experts [8].

Fig. 3.

Main neuroimaging findings of trances: A Summary figures with the location of the main findings found in functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) trance studies (N = 4) [8, 60, 74, 80]. B Psychographic experts (EXP in red) showed lower Single Photon Emission Computed Tomography (SPECT) activity during trance (condition: control (Con) vs. psychography (Psych)) compared to fewer experts (LEX in blue) who showed greater activity during trance in the orange brain areas. Adapted with permission from [80]. C fMRI activity modulation in a trance case study. C1: Blood-oxygen-level-dependent (BOLD) signal modulation in the auditory cortex (yellow box) with signal increasing when trance was self-assessed as high (dark blue) and decreasing when reported as low (gray) while listening to music (white represents the condition of resting with no music), C2: BOLD signal in the auditory cortex (yellow box) show increased signal during music (blue boxes) compared to no music (gray boxes), and in the last two blocks (bright blue), the trance was perceived as high by the subject. Adapted with permission from [74]. D Significant BOLD activation during mediumistic trance compared to resting conditions (in red) and during mediumistic trance compared to imagination (in blue). Reproduced with permission from [60]. E Mediumistic trance vs. resting brain modulation within the sensorimotor network. Reproduced with permission from [60]

Moreover, three fMRI studies have highlighted the implication of important areas of the default mode network (DMN) with the activation of the PCC [8, 60] and the modulation of the orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) during trance [60, 74]. A case study with an expert in shamanic trance showed that activity in the OFC was modulated by the intensity of trance perception. The OFC would be active until the subject's trance perception rose to a high level, at which point the OFC showed a decrease in activation during the remaining period of data collection. This result could be the neural correlate marking entry into a deep trance according to a case study [74]. A study with 16 participants (8 mediums and 8 controls) also reported higher activation of the OFC, bilateral occipital cortex, temporal pole, left middle temporal gyrus and middle frontal gyrus during mediumistic trance compared to the ordinary consciousness resting state condition (Fig. 3D) [60]. The PCC is a major integration center in the DMN associated with inwardly directed mental states [89]. The stronger activation of the PCC found during the mediumistic trance compared to the imagine-trance condition would reflect the sustained effort not to engage in any cognitively demanding task, and the orbitofrontal cortex would involve higher-order processes of integration, evaluation and regulation of sensory information [60]. Similarly, co-activation of the PCC with the ACC and insula (belonging to the control network involved in maintaining relevant neural flows) suggests that inwardly directed neural flow was amplified by control processes in the shamanic trance [8]. Note that there was no difference during resting state condition when comparing trance experts and the control group in the DMN [60].

These studies also reported the involvement of the auditory cortex [8, 60, 74, 80]. Regarding mediumistic trance, an increase in activation of the superior temporal gyrus during trance could be observed in less expert reporting hearing voices [60, 80]. Additionally, functional connectivity was increased in the auditory and sensorimotor networks (Fig. 3E) during trance compared to the resting state and imaginative-trance conditions, respectively, although no differences in the resting state network were found between expert mediums and the control group, which could explain the reported voice perception by participants during a mediumistic trance [60]. Interestingly, the superior temporal gyrus, which contains the auditory cortex, was deactivated in expert mediums who reported no longer being aware of the environment, unlike less expert mediums [80]. Additionally, for the shamanic trance, other authors reported an increase in blood-oxygen-level-dependent (BOLD) signals in both auditory cortices when the trance was perceived as high and a decrease in these signals when there was no more music (Fig. 3C1-2). In addition, the BOLD signal was significantly higher when the subject's perception was high compared to low (Fig. 3C1), even though the same stimuli played revealed an intrinsic modification from the participant. Other regions were found to be linked to high perception of trance, such as the right parietal, right frontal and prostriata areas [74]. A different result was found for the second study on shamanic trance with a decrease in connectivity between auditory areas, suggesting perceptual decoupling during trance [8]. According to these authors, this perceptual decoupling would suppress auditory information that does not reach the cortex as easily during trance (for a summary of fMRI results, see Fig. 3A1-2).

Physiological studies

No significant physiological differences were reported for blood pressure and heart rate for trance possession group compared to the control group (N = 24) [77, 79]. Although heart rate increased significantly after the ritual, this change was the same for both groups [77]. Also, despite subjective participants' perception of change, no significant differences in blood pressure and physiological heart rate were reported for channeling state compared to resting state [62]. Although differences were observed for body temperature and skin conductance during channeling trance, they did not reach the significance threshold [62]. A significant decrease in salivary cortisol concentration was observed after exposure to 15 min of repetitive percussion or instrumental meditation music regardless of the instructions given (shamanic journey vs. relaxation) (N = 39) [4]. This indicates that listening to music, while lying down, was sufficient to induce a decrease in cortisol levels and therefore diminished stress. Moreover, an increase in noradrenaline, dopamine, and beta-endorphin was observed after a ritual of possession trance (N = 15) compared to the control group (no ritual, N = 9) [77].

Clinical studies

In the shamanic worldview, poor health or illnesses may be due to both non spiritual and spiritual factors [17]. For shamans, the soul is indeed the vital essence needed for life and can “split away” following a trauma. In contemporary Western practice, shamanic practitioners use more interactive therapies to supposedly restore wholeness to their consultants [17]. Several techniques are reported, such as “extraction”, “rapport building and power animal”, and “spirit release”. “Extraction” consists of removing “dense energies” caused by traumas using drumming with the shaman practitioner's intentions and the spirit realm's guidance. “Rapport building and power animal retrieval” consists of retrieving one’s power animal. The new ally is a personal emissary who helps assist consultants in the shamanic landscape (called the “spirit world”) during shamanic interventions and can be used regularly for companionship, protection, and guidance in everyday life. “Spirit release” consists of relieving a consultant from a lost soul, trapped and energetically incorporated into the consultant energy systems. A loving conversation and help from the “spirit realm's angelic guides” clear off the interfering energy and free the consultant from the “discarnate” spirit [19].

The next section describes several clinical studies that explored the potential benefits of different kinds of shamanic therapy on well-being. It is important to highlight that all these observational studies were conducted with small sample sizes and did not include any kind of control groups or conditions. The way the shamans were selected and what their qualifications were, was also not always specified.

Contemporary occidental shamanic practice

Vuckovic and colleagues conducted a clinical trial that resulted in 3 cohort studies in 2007, 2010 and 2012 [17, 18, 90]. The authors evaluated the efficacy of shamanic therapy for people with temporomandibular joint disorders (TMDs). TMD is a chronic disorder with non-progressive pain conditions (e.g., facial pain, jaw-joint pain, headaches, and earaches) that can be accompanied by stress, depression and disabilities. In the trial, patients (N = 20) had 5 visits with a shamanic practitioner and received an intervention including soul retrieval, extraction, and guided meditation. The shamanic practitioners were all women trained by Sandra Ingerman and received extensive training from the Foundation for Shamanic Studies. They were recommended by Ingerman because of their years of experience and their reputation in the community, in the Portland metropolitan area. Before and after the 5 interventions, participants self-reported their temporomandibular pain perception and its functional impact on a 0 to 10 scale, where 10 was “pain as bad as could be”. These measures were also repeated (through telephone interviews) four times (after 1, 3, 6 and 9 months post-intervention). In 2007, the authors first showed that this first-ever clinical trial of shamanic healing for TMDs was feasible, safe and acceptable to patients [90]. In 2010, they focused on the immediate outcomes. After the shamanic therapy, the worst pain score improved the most (from a mean of 7.48 ± 1.4 before the intervention to 3.6 ± 2.5 at the end of the intervention) [17]. In 2012, the authors highlighted that nine months later, the mean was similar (i.e., 3.4 ± 2.5). Even though there was no control group, Vuckovic and colleagues consequently suggested a positive long-lasting effect [18]. According to them, the therapy mechanism involved reframing the patient’s perception of their symptoms as a dysfunction so that these were viewed as a cue to physical and mental states that were within the individual’s control. This was supported by an improved quality of life reported by 14 patients: TMD symptoms disappeared in 3 women who observed positive changes in psychosocial well-being (i.e., “more balanced”, “more calm”, “at peace”), and 11 women who still reported perceptible but decreased TMD symptoms and consistent positive changes in psychosocial well-being. Those 11 women felt less hopeless about the pain, which is often long-lasting in TMDs. They perceived that the shamanic intervention had given them ways to cope with their pain. They also felt more at ease, balanced, and in control of their lives.

Wahbeh and colleagues [19] published a case series in which 8 sessions of shamanic therapy were proposed by 12 expert shamanic practitioners for 15 to 20 weeks to veterans (N = 6) with PTSD. Shamanic healing methods were derived from core shamanic principles taught by the Foundation for Shamanic Studies, and all sessions were delivered by one single practitioner, in the same location. Only 4 participants completed at least 7 shamanic interventions. During the sessions, the reported aim was to remove energetic toxins and illness-stimulating spiritual factors and fill with retrieving energies that promote spiritual health that have been lost through trauma. Interventions were centered on rapport building, power animal retrieval, extraction, compassionate spirit release, curses unraveling, soul retrieval, forgiveness/cord-cutting, aspect maturing/soul rematrixing and divination. After the intervention, PTSD symptoms decreased in all participants but one, while an improvement in quality of life was observed in all patients. Patients mentioned that being more in the “present moment” helped them alleviate their symptoms and that the shamanic therapy improved their capacity to deal with ambiguous and unknown situations, re-instill a feeling of safety in the world, a freedom from fear, and desire. Participants said that spirits and animal power interventions prevented dramatic and potentially destructive behavior by interrupting their anger cycles. They also reported some improvements through renegotiating traumatic experiences in shamanic journeying and seeing the event from different perspectives. The authors suggest that shamanic interventions seem to be helpful for people with PTSD symptoms, although this interpretation should be taken cautiously given that there were neither controls nor statistical analyses in this study.

In Krycka’s study [15], a shamanic intervention centered on power animal retrieval and soul retrieval was offered to patients (N = 15) with life-threatening illnesses (e.g., acquired immune deficiency syndrome, cancers). Shamanic practitioners were described as “qualified” but there was no information on the selection process. After the intervention, the participants reported some changes. Regarding agency, they at last felt able to act in their lives, “to do something” about being ill. Thanks to their omniscient guides, they said they could anticipate events that they did not even see before the intervention. In addition, the retrieval allowed for the return of embodiment in many participants who felt oddness or a significant loss of place in the world. With the help of shamans, the lost parts seemed to be restored back into consciousness. Self-information would thereby become available to the person and would enhance their understanding of their present situation. The self-directed nature of the shamanic treatment (linked to volition) gave the participants room to use control and experience surrender (self-direction was experienced as increased volition). They all learned to trust their own processes and accept their health concerns. Finally, the technique would strengthen the participants’ resilience. They report that they managed to handle their own trauma to readily adapt to new and changing circumstances brought on by illness.

Finally, a preference-based controlled study is currently underway at the University and the University Hospital of Liege to investigate the influence of AICT, self-hypnosis, and self-compassion meditation on the quality of life of post-treatment oncology patients. This longitudinal clinical trial assesses a range of symptoms, such as pain, fatigue, sleep difficulties, emotional distress (anxiety and depression) and cognitive difficulties [70].

Dang-ki: an ancestral shamanic possession practice

In Southeast Asia, dang-kis are shamans, originally coming from China, who are usually reportedly possessed by a helping deity to heal and serve the patients [76]. These shamans usually apply more than one method to treat a given problem that generally includes words, talismans and physical manipulations. In Lee and colleagues’ cohort study [58], ethnographic interviews were conducted in Singapore. The three shamans’ shrines were recruited through an informal Taoist organization in Singapore. In this experiment, the “appointment” of the three shamans was hereditary. There was no formal training for shamans but they all received an apprenticeship under an experienced shaman. Patients (N = 21) had physical concerns (e.g., gastric, blood circulation, energetic concerns), cognitive-affective problems (e.g., agitation, nervousness, sense of insecurity, lack of self-awareness, hopelessness), or interpersonal functioning issues (e.g., interpersonal conflict). There were three outcome measures: immediately before and after the shamanic therapy (one session) and approximately 1 month later. Overall, 11 patients perceived their consultations as helpful, 4 perceived their consultations as helpful but were unable to follow all recommendations, 5 were not sure of the outcome because they had yet to see any concrete results and 1 patient considered his consultation unhelpful. In traditional Chinese Medicine, where supernatural beliefs still remain, the shaman attaches the patient’s emotions and needs to the transactional symbols (e.g., a fu) to transform the patient’s experience. For the authors, the symbolic therapy model provides a useful framework to understand the perceived helpfulness of the therapy. The authors believe that other factors may contribute, such as expectations, faith, hope and pragmatic attitude. Some patients could also construct a common clinical reality through reframing and selective perception.

The preliminary results of all these clinical studies appear to yield encouraging outcomes, both in terms of physical benefits (e.g., reduced functional pain) and psychological well-being (e.g., improved quality of life, restoration of agency despite illness). Nevertheless, these findings only stem from case reports and small cohort studies with methodological limitations. Moreover, the types of trance explored and the investigated patient populations are heterogeneous. Future research endeavors must therefore prioritize rigorous protocols, including adding a placebo condition or a control group, for such interventions.

Discussion

Findings

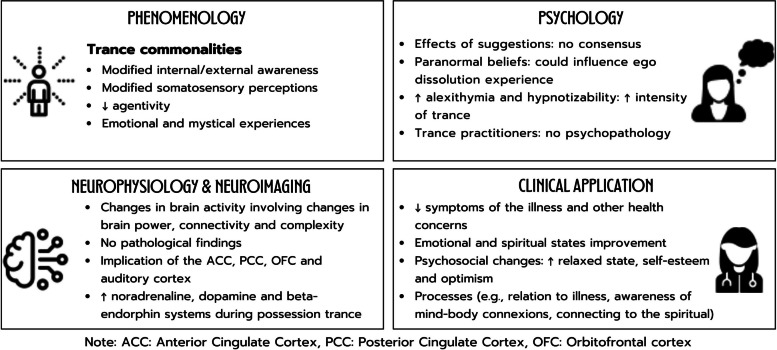

Through the different types of trance inherited from shamanic practice, 4 common points can be highlighted in phenomenology: (1) modification of internal and external consciousness; (2) modulated somatosensory perceptions; (3) alteration of agency/increased automaticity; and (4) states experienced as emotionally intense or even mystical. More specifically, possession and channeling trances exhibited distinct characteristics such as entity possession and amnesia. The feeling of a replacement of personal identity by an “external entity” seem to be central in these trances resulting in uncontrolled moves, tremors and less awareness of what happened during the state [60, 75, 76, 80]. This is reflected by partial amnesia (often reported in channeling) or even complete amnesia for the possession trance [75–80]. It would therefore seem that the experience depends on the depth of the trance and the extent to which the entity communicates only with the individual or takes place directly in the body of the participant. Concerning the shamanic journey and AICT, the experience seems to be broader and variable. Roney-Dougal [91] suggested that all states of consciousness, even if they are unique, would be located on a continuum. More studies are therefore needed to identify what is phenomenologically common or not in these practices (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Main results of the scoping review divided into 4 categories

Two main categories emerge in psychological variables: influencing factors and psychopathology. The role of suggestions before experimentation is still debated. While some authors have shown a change in the experience, such as heaviness, dreamlike states, and a subjective decrease in heart rate (not found with physiological measures) [4], others have found no influence of suggestions [83]. Concerning paranormal beliefs, these could influence the interpretation of the experience in terms of dissolution of the self but not in terms of the intensity of the trance experience [3, 14]. In addition to these observations, one study showed that people who reported a greater difficulty in identifying their emotions (i.e., alexithymia) could also be those with a greater ability to dissociate easily, which could facilitate entry into trance [3]. Furthermore, people with greater suggestibility are also more likely to have a more intense shamanic experience [85]. Regarding the potential psychopathological aspect of trance practice, studies tend to invalidate any presence of psychiatric pathologies among shamans [16, 51, 60, 62, 75, 76, 78–80, 82]. In fact, numerous articles and community-based psychiatric epidemiological surveys among shamans indicated no evidence that shamanism is an expression of psychopathology. These findings help rectifying shamans’ reputation, which has been tainted by past speculation of psychopathology [16]. Additionally, the spiritual training for entering and exiting the trance state, the change in self-perception or even the change in identity and the role associated with this new status would be some of the factors leading to more lasting changes in one’s sense of self [75, 76] (Fig. 4).

Neurophysiological studies confirm the absence of neurological issues in shamanic trances [78, 79, 82]. While no single frequency signature was found for all trances, possession and salpuri dancing showed increased alpha and theta bands [29, 78, 79]. Conversely, shamanic practitioners and drum listeners exhibited decreased alpha frequency band and connectivity [22, 83], with beta and gamma bands linked to complex internal imagery [22, 51]. These findings align with increased internal awareness during frontal stimulation for AICT [82]. Various studies showed that the DMN’s connectivity may distinguish schizophrenia from trance states [60] as it seems preserved only in trance experts during trance [8, 60, 92–94]. An increase in the activity of the PCC and its co-activation with the ACC and insula would suggest heightened self-referential experiences enhanced by certain control-related brain areas [8, 60, 82]. Additionally, a decrease in activation of the OFC at the onset of trance perception could be the neuronal correlate marking deepness of the trance [74], akin to findings in psychedelic studies [95, 96]. In mediumistic trances, written stories became more complex despite an overall drop in brain activity among experts, which is consistent with the absence of consciousness reported by participants [80]. Additionally, mediumistic studies found increased activity and connectivity in the auditory cortex, possibly associated with participants hearing voices [60, 80], similar to auditory hallucinations in psychotic patients [97]. Studies on shamanic trance are not unanimous with a study that showed a higher activation in the auditory cortex, suggesting that it is the perception of the trance that modulates the auditory cortical signals [74]. In contrast, reduced connectivity between auditory regions was also found, suggesting a sensory decoupling that would maintain the trance state [8]. Additionally, studies did not find differences in blood pressure, heart rate, temperature, or skin conductance during trance [62, 77, 79]. Moreover, possession trance showed increased noradrenaline, dopamine, and beta-endorphin levels, possibly explaining memory alterations and changes in pain or motor behaviors [21, 53, 77–79, 98, 99]. These latter findings suggest that possession trance might involve less control over the body and self-awareness compared to other trance types [5, 100] (Fig. 4).

The physiological changes observed can also be related to the beneficial effects reported by people experiencing trances. Studies have shown that shamanic therapies could potentially be an avenue of clinical exploration, particularly in the area of pain, quality of life and psychosocial well-being in TMD [17, 18, 90]. Similarly, studies are paving the way for further investigation of shamanic interventions on symptoms and quality of life in veterans' PTSD [19] or life-threatening illnesses [15]. The major advantage of these techniques reported by patients is the impression of becoming an actor in their health. The feeling of well-being and the improvement of disturbing symptoms could be linked to the stimulation of the immune system during trance by decreasing cortisol levels [4]. According to the traditional vision, the explanation for the clinical improvement could come from the role of the shaman who came to collect “parts of souls” to treat the consultants. In Western shamanic therapies, the individual is an integral part of the healing process. However, it is important to note that these clinical studies suffer from major limitations, as the majority of the studies did not carry out statistical analyses of the data and lack of control group and conditions (Fig. 4). Rigorous studies are therefore necessary to draw firm conclusions about the power of these practices as complementary techniques. Clinically, a study of shamanism in a therapeutic setting highlights the need to develop symbolic therapy models that focus on patients' expectations, beliefs and culture [58].

Limitations

This paper presents some limitations. First, research on shamanic trance and trances derived from shamanic practices is still in its infancy. All the above-mentioned studies have major methodological limitations, such as the absence of control groups, lack of randomization, small sample sizes, insufficient statistical analysis and a lack of information about the recruitment of shamans, their qualifications and their level of expertise. This lack of scientific rigor prevents any generalizability of the findings, and caution is warranted regarding their interpretation.

The second limitation is that our search only consulted two databases (PubMed and Google Scholar), which could be considered a lack of completeness. However, PubMed is the main database for searching bibliographic documents specifically in biology and medicine areas. In addition, using the Google Scholar database allowed us to diversify our fields of interest and to take into account all the multidisciplinary and academic documentation in the scientific fields. Furthermore, the search of the references of the cited literature as well as the use of search alert strategies throughout the writing of this paper may represent reasonable remedies to mitigate possible shortcomings in accessing relevant material.

The third limitation concerns the articles’ criteria for selection: shamanic trance had to be the main object of the article. This rigid criterion would exclude records on topics or some aspects related to other trances such as mediumistic trance or possession trance that were not experienced in a shamanic context. We also excluded records about psychedelics to focus on induction trance with no substance use. As mentioned above, the categorization of the different types of trance is still debated to determine where the boundaries stand between specific trance states. We therefore decided to adhere to our initial criteria and to include only articles comprising the indicated keywords. Our review can therefore refer to articles on mediumistic trance and possession trance without having made an exhaustive inventory of the subject. In addition, our search was restricted to articles written in English, which prevents the selection of potentially relevant studies written in other languages.

Note that 14 out of 27 articles were published before 2016, including 2 before 2000. This leads us to mention that articles are sometimes based on a lack of contemporary methodological rigor. Nevertheless, this limitation also highlights the small number of studies carried out thus far in neurophysiology, neuroimagery, clinical and psychology fields and underlines the need to look further into the subject. Shamanic trance is now beginning to gain interest from a scientific point of view.

Finally, following a rigorous observation of the selected articles, we have chosen to present our results according to 4 main categories of results, namely, phenomenology, psychology, brain and physiological function and clinical applications. This choice resulted in the exclusion of articles with an anthropological or ethnopsychiatric orientation (mainly published work in book form) and perhaps other more cultural and societal domains. We may have lost some data by including only those four categories of articles, but we did take stock of the situation to provide a well-structured overview of the subject in medical and psychological sciences.

Future research directions

Future research should pursue a number of objectives. First, studies with methodologically sound designs should be conducted to determine the generality of some of the results found for each dimension. In addition, randomized controlled trials based on large samples as well as standardization of protocols, training, and qualification for so-called 'expert' shamans are needed. To evaluate the potential effectiveness of shamanic therapies, it would also be necessary to establish control groups without prior knowledge or experience of shamanic practices. Additionally, to highlight the specific effects of shamanic interventions, future work should compare them to other types of spiritual practices (yoga, tai chi, qi gong, etc.) or even practices exclusively involving the concept of movement (dance, gymnastics, etc.). Regarding the auditory dimension, an interesting placebo could be to compare sounds known to induce trances with "neutral" sounds or binaural beats to experiment with what sounds or representations actually induce shamanic-like trances. It is also necessary to conduct studies that analyze shamanic trances from a multidimensional perspective. The understanding of these complex phenomena can only be achieved by putting neurophysiological, psychological, phenomenological and, where relevant, clinical data into perspective [70]. Taking individual, social and cultural variables into account is also very important in the study of shamanic trances. This, in order to avoid the “Western fallacy” of applying a Western explanatory model to the experiences of other cultures [101], but also to better understand Western practices derived from the shamanic tradition (e.g., AICT).

From a clinical point of view, considering cultural context in psychopathology would avoid over-diagnosis of psychotic disorders in people with strong supernatural beliefs. Conversely, another bias would be to systematically interpret all experiences as normal due to cultural differences [56]. This highlights the need for a specialized approach to disorders such as dissociative disorders and psychoses in clinical practice [63]. Moreover, traditional cultures could be a source of inspiration for the treatment of certain psychiatric disorders in the West. The normalization of trances and early training in the mastery of these states seem to promote their integration into the traditional community [53, 91, 100]. Studies could therefore be carried out to compare traditional and Western treatments for certain forms of psychosis such as schizophrenia. Clinical trials are also encouraged to determine whether trance control could reduce symptoms associated with conditions such as schizophrenia. From a fundamental point of view, cultural differences in phenomena with similarities raise questions about the nature of what we call “psychosis” or “dissociative disorders” in the West. We can legitimately ask what differentiates the trajectory of people who have experienced spontaneous trances during what they call “shamanic calls”, conferring on them the status of shaman in traditional societies, and people experiencing dissociative states with hallucinations, conferring on them a diagnosis of schizophrenia in Western societies. To answer these questions, future studies could compare patients with schizophrenia and experts, considered “adapted” to trance at the neurophenomenological and psychological level.

Studies should also investigate the different types of shamanic trances depending on their induction methods to understand the difference in experience [55]. In this context, the role of music deserves in-depth research. Both ancestral [14, 15, 85] and modern (e.g., Foundation for Shamanic Studies 1979, TranceScience Research Institute, 2019) traditions share the common denominator of using sound to bring the individual into trance. Concretely, it could be interesting to compare the phenomenological experience and the cerebral correlates associated with different sound loops (loops supposed to induce trances compared to “non inducing” loops). Beyond sound loops, the group is also a common variable to investigate. In fact, the presence of peers undergoing the same experience could have a real influence, even encouraging mimicry. Studies could therefore be carried out on the sociological aspect of induction and experience. In addition, analyses could be carried out to establish which individuals are most likely to experience certain types of trance based on their personality, psychological, sociodemographic, neurophysiological profiles and experience at baseline.

Finally, it might be interesting to explore the potential clinical benefits of the different types of trance and the influence of the different practice contexts. Studies could be carried out on the advantages and disadvantages of trances practiced in a hetero-induced way, more often encountered outside the West (a shaman enters a trance at the patient's request) compared to trances practiced increasingly in a self-induced way, emerging in the West (the patient enters a trance alone). It might also be interesting to explore the physical and mental health benefits of trance.

Conclusions

Differences exist between the various types of trances at the phenomenological level which highlights the need to better characterize what distinguishes and brings together these different practices. Several psychological variables, such as music, expectancies and personality, seem to play a role in the induction and experience of trance and should be taken into account in future studies. Moreover, the different psychological and neurophysiological results point to an absence of pathological state in advanced trance practitioners compared to control participants. There are also differences between brain activity at rest and during trance. Finally, shamanic practices appear to be worthy of interest in future studies on complementary therapies that aim to reduce symptoms and improve quality of life in pathologies such as TMD and PTSD. However, the lack of methodological rigor highlights the need to continue multidisciplinary controlled and randomized studies in order to confirm these preliminary results and thus offer patients a wider range of complementary therapies and medicines. Only by pursuing these objectives will we be able to gain essential understanding about the relevance of new shamanic trance techniques, such as AICT, in Western societies.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

The study was supported by the University and University Hospital of Liege and the Algology Interdisciplinary Center, the Belgian National Funds for Scientific Research (FRS-FNRS –Télévie), the MIS FNRS (F.4521.23), the BIAL Foundation, the Mind Science Foundation, the European Commission, the fund Generet, the King Baudouin Foundation, AstraZeneca foundation, the Leon Fredericq foundation and Belgium Foundation Against Cancer (Grants Number: 2017064 and C/2020/1357). NM is a PhD Student and FRESH-FNRS fellow, CG is a postdoctoral researcher and OG is a research associate at FRS-FNRS. We thank Fatemeh Seyfzadehdarabad for helping with figure illustration.

Abbreviations:

- ACC

Anterior Cingulate Cortex

- BOLD

Blood-Oxygen-Level-Dependent

- DMN

Default Mode Network

- EEG

Electroencephalogram

- fMRI

Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging

- NA

Not Applicable

- NDR

No Difference Reported

- NSC

Non-ordinary States of Consciousness

- OFC

OrbitoFrontal Cortex

- PCC

Posterior Cingulate Cortex

- PRISMA-ScR

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews

- PTSD

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder

- SCC

State of Shamanic Consciousness

- AICT

Auto-Induced Cognitive Trance

- SPECT

Single Photon Emission Computed Tomography

- TMD

TemporoMandibular joint Disorder

- TMS

Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation

Authors’ contributions

YL, OG and AV were responsible for the conception and design of the study. YL was responsible for researching the articles. YL was responsible for creating the database for entering results. NM, YL, AB1, CG, FR, AB3, OG and AV were responsible for reading, collecting information and analyzing the articles. NM and YL were responsible for compiling the results. NM, YL, OG and AV were responsible for drafting the manuscript. NM and YL were responsible for the interpretation of the data. NM and YL were responsible for the design of the figures. AB1, CG, FR, AB3, OG and AV were responsible for proofreading and editing. OG and AV were responsible for supervising. NM was responsible for submitting the article. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by BIAL Foundation, grant number 344/20.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and in the supplementary information file: Table S1—Summary of the results reported by studies included in the scoping review. For more information, please contact the corresponding author (nmarie@uliege.be; ogosseries@uliege.be; avanhaudenhuyse@chuliege.be).

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Audrey Vanhaudenhuyse and Olivia Gosseries contributed equally as last authors.

Nolwenn Marie and Yannick Lafon contributed equally as first authors.

Contributor Information

Nolwenn Marie, Email: nmarie@uliege.be.

Audrey Vanhaudenhuyse, Email: avanhaudenhuyse@chuliege.be.

Olivia Gosseries, Email: ogosseries@uliege.be.

References

- 1.Shear, J. (Éd.). Explaining Consciousness (1st edition). Bradford Books. 1997.