Abstract

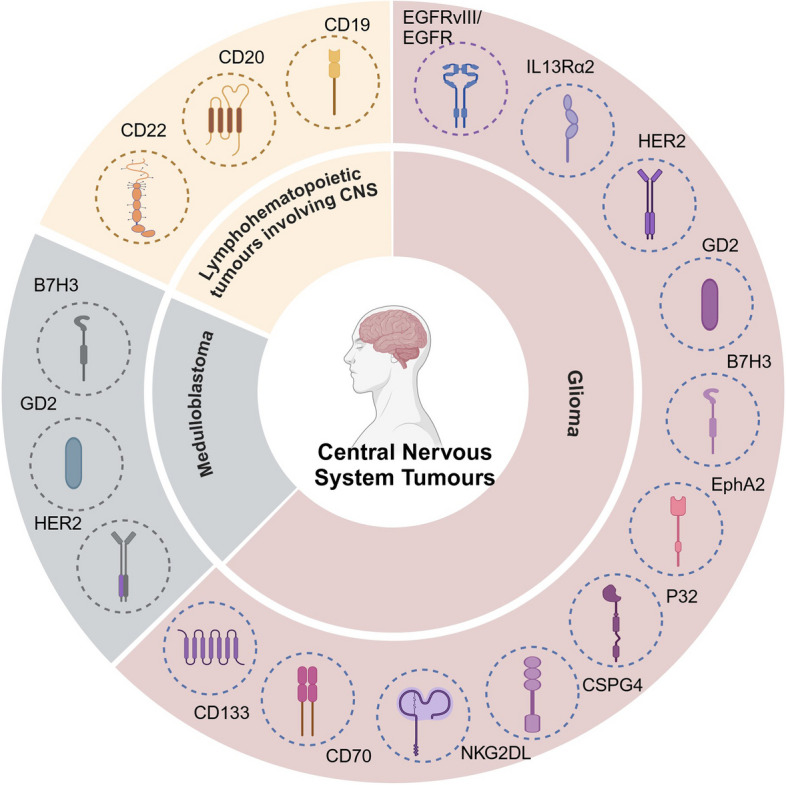

The application of chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy in central nervous system tumors has significantly advanced; however, challenges pertaining to the blood-brain barrier, immunosuppressive microenvironment, and antigenic heterogeneity continue to be encountered, unlike its success in hematological malignancies such as acute lymphoblastic leukemia and diffuse large B-cell lymphomas. This review examined the research progress of chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy in gliomas, medulloblastomas, and lymphohematopoietic tumors of the central nervous system, focusing on chimeric antigen receptor T-cells targeting antigens such as EGFRvIII, HER2, B7H3, GD2, and CD19 in preclinical and clinical studies. It synthesized current research findings to offer valuable insights for future chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapeutic strategies for central nervous system tumors and advance the development and application of this therapeutic modality in this domain.

Keywords: Central nervous system tumors, Chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy, Glioblastoma, Medulloblastoma, Central nervous system lymphoma, Central nervous system acute lymphoblastic leukemia, Brain tumors

Introduction

The principle of chimeric antigen receptor T-cell (CAR-T) therapy involves genetically modifying T cells to specifically recognize distinct targets on the tumor cell surface, thereby inducing cytotoxic effects. CAR-T therapy has become a major focus of immunotherapy research for malignant tumors in recent years, representing a milestone breakthrough in targeted therapy [1]. CAR-T therapy has shown success in treating various refractory or recurrent hematological malignancies and is considered a potentially curative approach for certain oncological conditions [2, 3]. However, its application in solid tumors, particularly central nervous system (CNS) tumors, remains limited owing to the complex tumor microenvironment (TME) of CNS tumors and the presence of the blood-brain barrier (BBB), introducing significant challenges for CAR-T therapy applications. Researchers are actively investigating various strategies to overcome these challenges, and various clinical and preclinical studies have established a foundation for the future development of CAR-T therapy for CNS tumors.

Challenges of CAR-T therapy in CNS tumors

Blood-brain barrier

The BBB is a highly selective, semi-permeable barrier separating the cerebral blood vessels and brain tissue (Fig. 1). The BBB comprises endothelial cells, a basement membrane, and astrocytic end feet. The main functions of the BBB include protecting brain tissue, maintaining CNS homeostasis, and regulating the passage of essential nutrients and oxygen while preventing the entry of harmful substances [4]. The tight junctions and adherens junctions between brain capillary endothelial cells form the physical barrier, limiting paracellular transport into the brain. Thus, molecules in the bloodstream must traverse both the apical and basolateral membranes of endothelial cells to access the brain. Additionally, efflux proteins, such as P-glycoprotein, multidrug resistance protein (MRP), and breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP), on endothelial cells form a biochemical barrier by actively transporting exogenous substances back into the systemic circulation, limiting their accumulation in the brain [5]. However, this selectivity impedes the delivery of drugs and therapeutic agents to the brain [6, 7]. Inflammation, infection, and cancer can compromise BBB integrity, leading to immune cell infiltration and accumulation within the CNS [8]. For instance, in gliomas, reduced expression of tight junction proteins and overexpression of aquaporin-4 impair the integrity of endothelial cell junctions [9]. Currently, the primary methods for delivering CAR-T cells to the brain include intravenous injection, local intracerebroventricular delivery, and intracavitary tumor injection [10]. Intravenous injection is the most common route in treatment and clinical trials, yet it poses significant challenges for CNS tumors, as CAR-T cells often struggle to infiltrate the TME. Intracerebroventricular administration involves direct injection of CAR-T cells into the ventricular system, facilitating their distribution into the cerebrospinal fluid. Intracerebroventricular injection was first employed in CAR-T cell therapy for recurrent GBM. Intracavitary tumor injection involves direct CAR-T cell administration into the tumor mass [11]. In contrast to intravenous injections, local delivery methods can transport CAR-T cells directly to the tumor site, bypassing the BBB. This approach enhances CAR-T cell tumor infiltration and anti-tumor activity, thereby improving therapeutic outcomes, especially in glioblastoma and brain metastases from breast cancer [12–14].

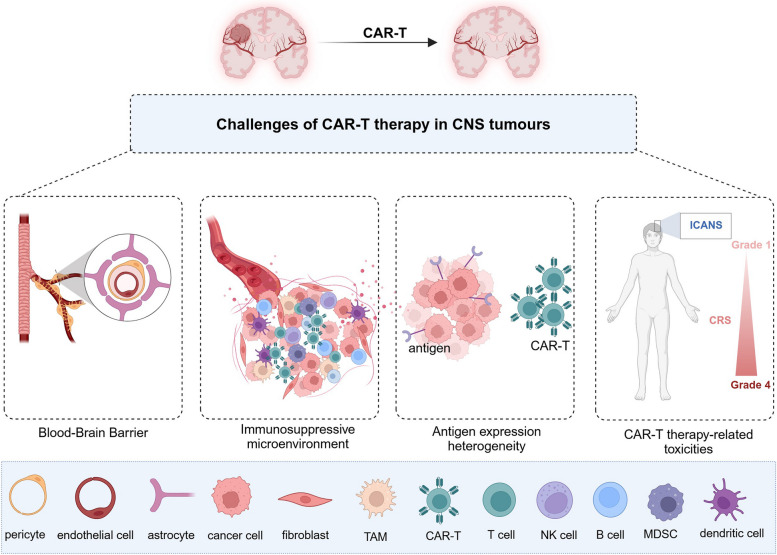

Fig. 1.

Challenges of CAR-T therapy in CNS tumors. The blood-brain barrier, immunosuppressive microenvironment, antigen expression heterogeneity, and CAR-T therapy-related toxicity are major challenges in CAR-T cell therapy for central nervous system tumors

Immunosuppressive microenvironment

The tumor immunosuppressive microenvironment weakens the ability of immune cells to attack tumors via diverse mechanisms. This microenvironment comprises various immunosuppressive components, such as tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs)/microglia, regulatory T cells (Tregs), and myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) (Fig. 1). These cells diminish the anti-tumor activity of effector T cells by releasing inhibitory factors or directly suppressing their function. In addition, the extracellular matrix (ECM) physically obstructs T-cell infiltration and promotes immunosuppression via signaling pathways, further facilitating tumor immune escape [15–17].

TAMs/microglia are crucial components of the CNS TME and can be classified into two subtypes: M1 and M2. M1 represents a pro-inflammatory phenotype with anti-tumor effects, whereas macrophages recruited to the TME are usually polarised to the M2 type, producing anti-inflammatory cytokines promoting immunosuppression, angiogenesis, and tumor progression [18]. Additionally, microglia within glioblastoma (GBM) microenvironments frequently experience high oxidative stress, triggering an imbalance in lipid metabolic homeostasis via the NR4A2/SQLE pathway and subsequently impairing antigen-presenting capacity [19]. This process diminishes cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) cell infiltration and impairs their cytotoxic function, further exacerbating the immunosuppressive microenvironment and promoting GBM tumor growth. MDSCs are limited in number within the CNS; nevertheless, they actively contribute to the initiation and regulation of immunosuppressive functions [20], primarily through mechanisms that include promoting tumor angiogenesis, inhibiting M1 macrophage polarisation, suppressing dendritic cell (DC) antigen presentation, and reducing natural killer (NK) cytotoxicity and T-cell activation [21]. MDSCs exert their immunosuppressive effects through multiple mechanisms, including the secretion of exosomes, the activity of pro-inflammatory cytokines (such as IL-13, IL-4, PGE2, IFN-γ, and IL-1β), and Toll-like receptor signaling pathways [21]. Additionally, immunosuppressive factors, including nitric oxide (NO), reactive oxygen species (ROS), and peroxynitrite (PNT), play significant roles in the immunosuppressive mechanisms employed by MDSCs [22]. Tumors promote the recruitment of MDSCs by secreting specific chemokines. For instance, chemokine axes such as C-X-C chemokine receptor type 4-C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 12 (CXCR4-CXCL12), CXCR2-CXCL5/8, and C-C chemokine receptor type 2- C-C motif chemokine ligand 2 (CCR2-CCL2) play a crucial role in this process [23]. Furthermore, IL-8 is regarded as a significant inducer of MDSC mobilization [24]. Studies have demonstrated that an increased number of MDSCs in GBM correlates with poorer patient prognosis [25]. Tregs can suppress the immune response in the tumor microenvironment and promote tumor development [26]. The primary mechanisms through which Tregs mediate immune suppression in the tumor microenvironment include the following: First, Tregs upregulate immune checkpoint receptors, including cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4), thereby inhibiting the interaction between CD80 and CD86 on antigen-presenting cells and the co-stimulatory receptor CD28 on effector T cells. Second, Tregs secrete a variety of immunosuppressive cytokines, including IL-10, IL-35, and transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β), and express the high-affinity α subunit of the IL-2 receptor (CD25), effectively depleting IL-2 and subsequently suppressing the activation and survival of effector T cells. Furthermore, Tregs exhibit elevated expression of ecto-nucleotidases CD39 and CD73 on their surface, which further enhances immune suppression in the tumor microenvironment [27], thereby undermining anti-tumor immune responses.

Pervasive TGF-β expression in the immunosuppressive microenvironment can promote tumor cell proliferation and enhance their invasiveness [28]. Additionally, TGF-β can modulate the composition and function of immune cells, thereby facilitating tumor cell evasion of the host immune system [29, 30]. Myeloid cells promote tumor immune escape by releasing interleukin-10 (IL-10), which accumulates within mesenchymal-like tumor regions and results in T-cell depletion. Studies have shown that JAK/STAT pathway inhibition restores T-cell function, highlighting the critical role of IL-10 in the immunosuppressive microenvironment of GBM [31]. Chemokines directly target non-immune cells in the tumor microenvironment (e.g., tumor and vascular endothelial cells) and play critical roles in regulating tumor cell proliferation, preserving cancer stem cell characteristics, and promoting tumor invasion and metastasis [32]. A significant elevation in cerebrospinal fluid and serum levels of CCL2 was observed in patients with CNS tumors undergoing HER2 CAR-T cell therapy. This cytokine is known for its role in recruiting Tregs and MDSCs and contributes to the attenuation of CAR-T cell-mediated tumor cell destruction [33]. Interactions between tumor cells and the microenvironment play a crucial role in tumor cell proliferation, migration, and drug resistance in GBM. Hypoxic regions of GBM attract and sequester TAMs and CTL, resulting in immunosuppression [34]. Additionally, single-cell transcriptomic analysis revealed that specific tumor subpopulations promote brain-wide proliferation through synaptic connections with neurons. This mechanism suggests that neuronal activity induces tumor microtubule formation, thereby accelerating tumor invasion and dissemination [35]. These mechanisms synergistically enable tumor cells to evade immune surveillance, fostering their growth and dissemination.

Antigen expression heterogeneity

Tumor targets can be classified into tumor-specific antigens (TSAs) and tumor-associated antigens (TAAs). TSAs are antigens that are exclusively expressed on tumor cells and not on normal tissues. Although these antigens are deemed ideal targets for CAR-T therapy, their expression on the surface of tumor cells is exceedingly rare, leading to significant limitations in clinical application. In contrast, TAAs are antigens that exhibit significantly higher expression levels in tumor cells than in normal tissues [36]. Currently, the vast majority of CAR-T products target TAAs, such as CD19, CD20, CD22, CD30, and BCMA in hematologic malignancies [37–39], as well as CEA, EGFR, HER2, EPHA2, and IL-13Rα2 in solid tumors [40]. Specific antigens play important roles in CAR-T cell functioning, however, antigen expression heterogeneity results in a limited number of antigens that can be targeted by CAR-T cells [41]. The expression levels of targets on tumor cell surfaces may fluctuate between patients and different time points or regions in the same patient, and primary and recurrent tumors show significantly different characteristics, demonstrating significant heterogeneity (Fig. 1) [42]. For instance, in a study investigating the efficacy of the epidermal growth factor receptor variant III (EGFRvIII) peptide vaccine Rindopepimut in treating GBM, it was observed that 21 patients (57%) experienced a loss of EGFRvIII expression after treatment; similarly, 23 out of 39 patients (59%) in the control group also exhibited the same outcome [43]. These results underscore the significant impact of antigen heterogeneity on targeted therapies. Furthermore, there exists a similar issue regarding declining antigen expression in CAR-T cell therapy. A study indicated that among patients receiving EGFRvIII CAR-T therapy, 71.4% exhibited reduced levels of antigen expression, while the growth of EGFRvIII-negative tumor cells was also observed [44]. These findings further emphasize the complexities of antigen heterogeneity during the therapeutic process. Additionally, the presence of cancer stem cells contributes to the extensive heterogeneity observed in GBM [45]. Therefore, ideal antigenic candidates for CAR-T therapy should be highly and uniformly expressed in tumor cells, with low inter-tumor heterogeneity [46], and should have minimal or almost no expression in normal tissues to improve treatment specificity and efficacy.

CAR-T therapy-related toxicities

Toxic reactions of CAR-T therapy for CNS tumors pose significant challenges, particularly cytokine release syndrome (CRS) and immune effector cell-associated neurotoxicity syndrome (ICANS) (Fig. 1) [47, 48]. Clinical manifestations of ICANS include delirium, somnolence, aphasia, and tremor. Severe cases can present with seizures, cerebral edema, coma, or even death, with a fatality rate of approximately 3% [49]. The symptoms of ICANS are often similar to those of primary brain tumors, potentially causing diagnostic challenges.

Studies have shown that ICANS onset is closely related to high levels of cytokines such as IL-1, IL-6, and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), which are primarily released by activated monocytes/macrophages [50]. CRS can be effectively controlled through monocyte depletion and administration of the IL-6 receptor blocker tocilizumab or the IL-1 receptor blocker anakinra; however, these measures have failed to completely prevent the development of fatal neurotoxicity [51]. Furthermore, endothelial cell activation triggered by CAR-T therapy results in increased vascular permeability, which is further exacerbated by BBB disruption by CNS tumors. Multiple cytokines, such as IL-6 and interferon-γ (IFN-γ), can selectively pass through the compromised BBB and exacerbate ICANS outcomes [52, 53]. Therefore, management and control of toxic reactions during CAR-T therapy are crucial for achieving therapeutic success.

In addition to the previously mentioned challenges, CAR-T cell therapy encounters several obstacles related to technical processes in its practical application. First, the complexity of CAR design poses a substantial challenge, particularly regarding the selection of appropriate antigen targets, optimization of co-stimulatory molecule combinations, and enhancement of CAR-T cell specificity and persistence. Second, the complexity of the production process further restricts the widespread application of CAR-T therapy, involving in vitro expansion of CAR-T cells, the risk of insertional oncogenesis from genetic modification [54], and the transfection efficiency of CAR-T cells [55]. Furthermore, during treatment, the selection of CAR-T cell dosage, evaluation of therapeutic efficacy, and monitoring of side effects necessitate further research and standardization. These challenges within the technical processes not only affect efficacy and application but also contribute to elevated treatment costs, presenting another significant barrier to the advancement of CAR-T cell therapy [56]. To address these challenges, ongoing innovation and improvement are essential to ensure the broader application of CAR-T therapy.

CAR-T therapy for CNS tumors

A wide variety of CNS tumors exist, nevertheless, this article focused on advances in CAR-T therapy for the following tumor types: GBM, diffuse midline glioma (DMG), diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma (DIPG), and ventricular meningiocytoma among gliomas; medulloblastoma among embryonal tumors; and lymphohematopoietic tumors involving the CNS. Table 1 lists relevant clinical trials that enrolled patients in recent years, with data from https://clinicaltrials.gov/.

Table 1.

Ongoing clinical trials recruiting patients for CAR-T therapy in Central Nervous System tumors (https://clinicaltrials.gov/)

| NCT | Study Title | Phase | Disease type | Target | Participants | Method of delivery | Research Institutions | Study Start | Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCT06186401 | Anti-EGFRvIII synNotch Receptor Induced Anti-EphA2/IL-13Ralpha2 CAR (E-SYNC) T Cells | phase 1 | GBM |

EGFRvIII; IL13Rα2; EphA2 |

20 | IV | University of California | 2024 | Recruiting |

| NCT05802693 | A Study to Evaluate the Safety, Tolerance and Initial Efficacy of EGFRvIII CAR-T on Glioblastoma | Early phase 1 | GBM | EGFRvIII | 22 | ICV | Beijing Tsinghua Chang Gung Hospital | 2023 | Not yet recruiting |

| NCT05063682 | The Efficacy and Safety of Brain-targeting Immune Cells (EGFRvIII-CAR T Cells) in Treating Patients With Leptomeningeal Disease From Glioblastoma. Administering Patients EGFRvIII -CAR T Cells May Help to Recognize and Destroy Brain Tumor Cells in Patients (CARTREMENDOUS) | phase 1 | GBM | EGFRvIII | 10 | ICV |

University Of Oulu; Jyväskylä Central Hospital; Apollo Hospital |

2020 | Unknown |

| NCT06355908 | IL13Rα2 CAR-T for Patients With r/r Glioma | phase 1 | Glioma | IL13Rα2 | 30 | ICV | Beijing Tiantan Hospital | 2024 | Recruiting |

| NCT05540873 | A Clinical Study of IL13Rα2 Targeted CAR-T in Patients With Malignant Glioma(MAGIC-I) | phase 1 | Malignant Glioma | IL13Rα2 | 18 | IV | National Cancer Center | 2022 | Recruiting |

| NCT04510051 | CAR T Cells After Lymphodepletion for the Treatment of IL13Rα2 Positive Recurrent or Refractory Brain Tumors in Children | phase 1 | Brain Neoplasm | IL13Rα2 | 18 | ICV | City of Hope Medical Center | 2020 | Recruiting |

| NCT04003649 | IL13Ra2-CAR T Cells With or Without Nivolumab and Ipilimumab in Treating Patients With GBM | phase 1 | GBM | IL13Rα2 | 60 | ICV/intracranital ICV | City of Hope Medical Center | 2019 | Recruiting |

| NCT04661384 | Brain Tumor-Specific Immune Cells (IL13Ralpha2-CAR T Cells) for the Treatment of Leptomeningeal Glioblastoma, Ependymoma, or Medulloblastoma | phase 1 |

GBM; Ependymoma; medulloblastoma |

IL13Rα2 | 30 | ICV | City of Hope Medical Center | 2021 | Recruiting |

| NCT03696030 | HER2-CAR T Cells in Treating Patients With Recurrent Brain or Leptomeningeal Metastases | phase 1 | Metastatic Malignant Neoplasm in the Brain/Leptomeninges | HER2 | 39 | ICV | City of Hope Medical Center | 2018 | Recruiting |

| NCT04903080 | HER2-specific Chimeric Antigen Receptor (CAR) T Cells for Children With Ependymoma | phase 1 | Ependymoma | HER2 | 50 | IV | Pediatric Brain Tumor Consortium | 2022 | Recruiting |

| NCT05768880 | Study of B7-H3, EGFR806, HER2, And IL13-Zetakine (Quad) CAR T Cell Locoregional Immunotherapy For Pediatric Diffuse Intrinsic Pontine Glioma, Diffuse Midline Glioma, And Recurrent Or Refractory Central Nervous System Tumors | phase 1 | DIPG, DMG, Recurrent CNS Tumors |

B7H3; EGFR806; HER2; IL13Rα2 |

72 | ICV | Seattle Children’s Hospital | 2023 | Recruiting |

| NCT05544526 | CAR T Cells to Target GD2 for DMG (CARMIGO) | phase 1 | DMG | GD2 | 12 |

IV; ICV |

University College, London | 2023 | Recruiting |

| NCT05298995 | GD2-CAR T Cells for Pediatric Brain Tumours | phase 1 | Brain Tumors | GD2 | 54 | IV | Bambino Gesù Hospital and Research Institute | 2023 | Recruiting |

| NCT06221553 | Safety and Efficacy of Loco-regional B7H3 IL-7Ra CAR T Cell in DIPG (CMD03DIPG) | phase 1 | DIPG | B7H3 | 9 | ICV | Chulalongkorn University | 2024 | Recruiting |

| NCT05835687 | Loc3CAR: Locoregional Delivery of B7-H3-CAR T Cells for Pediatric Patients With Primary CNS Tumors | phase 1 | Primary CNS Tumors | B7H3 | 36 | ICV | St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital | 2023 | Recruiting |

| NCT05131763 | NKG2D-based CAR T-cells Immunotherapy for Patient With r/r NKG2DL + Solid Tumors | phase 1 |

GBM; Medulloblastoma; Hepatocellular carcinoma; Colon cancer |

NKG2DL | 3 | IV | Fudan University | 2021 | Unknown |

| NCT04717999 | Pilot Study of NKG2D CAR-T in Treating Patients With Recurrent Glioblastoma | NA | GBM | NKG2DL | 20 | ICV | UWELL Biopharma | 2021 | Unknown |

| NCT05353530 | Phase I Study of IL-8 Receptor-modified CD70 CAR T Cell Therapy in CD70 + Adult Glioblastoma (IMPACT) (IMPACT) | phase 1 | GBM | CD70 | 18 | IV | University of Florida | 2023 | Recruiting |

| NCT05625594 | Intracerebroventricular Administration of CD19-CAR T Cells (CD19CAR-CD28-CD3zeta-EGFRt-expressing Tcm-enriched T-lymphocytes) for the Treatment of Primary Central Nervous System Lymphoma | phase 1 | CNSL | CD19 | 20 | ICV | City of Hope Medical Center | 2023 | Recruiting |

| NCT03064269 | CAR-T Therapy for Central Nervous System B-cell Acute Lymphocytic Leukemia | phase 1 | CNS B-ALL | CD19 | 10 | NA | Shanghai Unicar-Therapy Bio-medicine Technology | 2017 | Recruiting |

| NCT06213636 | Fourth-gen CAR T Cells Targeting CD19/CD22 for Highly Resistant B-cell Lymphoma/Leukemia (PMBCL/CNS-BCL). (BAH241) | phase 1/2 | R/R Leukemia/Lymphoma patients with or without CNS |

CD19; CD22 |

75 | IV | Essen Biotech | 2024 | Recruiting |

| NCT04532203 | A Study of CAR-T Cells Therapy for Patients With Relapsed and/or Refractory Central Nervous System Hematological Malignancies | Early phase 1 | R/ R CNS hematological malignancies | CD19 | 72 | IV | Zhejiang University | 2020 | Recruiting |

| NCT05651178 | Human CD19-CD22 Targeted T Cells Injection for Refractory/Relapsed Central Nervous System Leukemia/Lymphoma Patients | Early phase 1 | CNS Involvement of R/R B Cell malignancies |

CD19; CD22 |

20 | IV | Hrain Biotechnology Co., Ltd. | 2022 | Recruiting |

GBM Glioblastoma, IV Intravenous, ICV Intracerebroventricular, DIPG Diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma, DMG Diffuse midline glioma, CNS Central nervous system, CNSL Ventral nervous system lymphoma, ALL Acute lymphoblastic leukaemia

Gliomas

Malignant gliomas are the most common primary brain tumors within the CNS [57] and originate from various glial cell types, including astrocytes, oligodendrocytes, ependymal cells, and microglia [58]. Among these, GBM represents the most aggressive and lethal glioma, characterized by a high degree of heterogeneity. Despite the routine use of comprehensive treatments including surgical resection, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy, the prognosis for GBM remains dismal, with severely limited patient survival, and curative outcomes remain elusive with traditional therapies [59, 60]. Ependymomas constitute another significant glioma subtype, arising from ependymal cells lining the ventricular system. Approximately 50% of ependymomas in adults occur in the spinal cord, whereas nearly 90% are intracranial in pediatric patients. Notably, over half of pediatric patients with ependymomas experience recurrence despite standard treatments, and the cure rate for recurrent ependymomas remains low even after multiple surgeries, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy, resulting in poor clinical outcomes [61]. DMG and DIPG are common and significantly aggressive gliomas in children [62]. Research on CAR-T cell therapy for gliomas is rapidly advancing, with efforts focused on optimizing target selection and delivery strategies to enhance therapeutic efficacy and address current treatment limitations. We summarized the mechanisms of action of clinically studied CAR-T targets in gliomas (Fig. 2) and briefly analyzed the strengths and weaknesses of these targets and other targets that have only been explored in preclinical studies (Table 2).

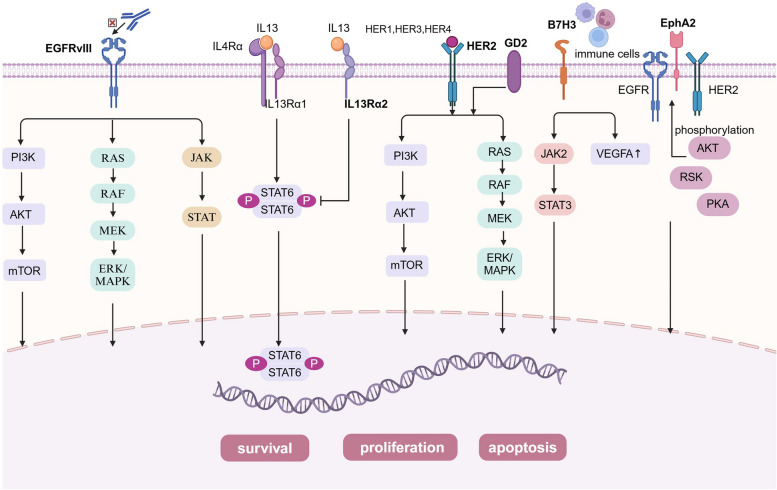

Fig. 2.

The mechanisms of action of clinically studied CAR-T targets in gliomas. EGFRvIII promotes GBM development mainly by enhancing the EGFRvIII-PI3K-AKT signalling pathway, EGFRvIII-Ras-Raf-MEK-ERK/MAPK signalling pathway and EGFRvIII-JAK-STAT signalling pathway; IL-13Rα2 competitively binds to IL-13, thereby inhibiting the STAT6 signaling pathway, promoting tumor cell invasion, metastasis, and proliferation, and inhibiting tumor cell apoptosis; Tumor formation via MAPK/ERK and PI3K/AKT/mTOR signalling pathways when HER2 gene expression is aberrant or GD2 is expressed; B7H3 enhanced cancer cell invasion by regulating the JAK2/STAT3 signalling pathway and upregulated the expression of vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGFA) to promote tumor angiogenesis; Overexpressed EphA2 promotes tumor progression through AKT/RSK/PKA-mediated phosphorylation events

Table 2.

Analysis of the advantages and disadvantages of CAR-T therapy targets for glioma

| Antigen | Characteristic | Antigen-expressing cancers | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EGFRvIII [44] | an 801 bp in-frame deletion of exons 2 to 7 |

glioblastoma; lung cancer; breast cancer; ovarian cancer; prostate cancer; |

• specifically expressed in tumors | • after CAR-T infusion, tumor samples showed increased levels of immunosuppressive molecules: IDO1,FOXP3,IL-10,PD-L1,and TGFβ. |

| IL13Rα2 [63, 64] | NA |

the central nervous system; melanoma; lung cancer; prostate cancer |

• aside from high testicular expression, it shows no expression elsewhere in the human body. | • on-target, off-tumor toxicity |

| HER2 [65–67] | a member of the EGFR family |

glioblastoma; ependymom; medulloblastoma; CNS cancer stem cells; breast cancer; renal cell carcinoma; lung adenocarcinoma |

• expressed across a spectrum of biologically diverse CNS tumors |

• the lower HER2 expression in CNS tumors relative to breast cancer, limit the application of HER2-targeting antibodies against CNS tumors; • on-target, off-tumor toxicity |

| GD2 [68, 69] | b-series ganglioside |

glioblastoma; astrocytoma; retinoblastoma; Ewing’s sarcoma; Rhabdomyosarcoma; osteosarcoma; leiomyosarcoma; liposarcoma; fibrosarcoma; small cell lung cancer; melanoma; breast cancer |

• tumor cells show high-density expression, while normal cells exhibit limited expression. |

• on-target, off-tumor toxicity; • GD2 is also expressed in low amounts on peripheral nerves and brain parenchyma |

| B7H3 [70, 71] | 316 amino acids encoded by 12 exons located in chromosome 9 in murine while in 15q24.1 in humans |

Glioblastoma; pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma; ovarian cancer; neuroblastoma; diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma; medulloblastoma; craniopharyngiom; atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumor; metastatic brain tumors |

• expressed on tumor cells and abnormal vessels, but rarely on normal cells. | • on-target, off-tumor toxicity |

| EphA2 [72] | a member of the Eph family of receptor tyrosine kinases (RTK) |

breast cancer; lung cancer; glioblastoma; melanoma |

• expressed highly in glioblastoma but only at low levels in normal brain tissue | • on-target, off-tumor toxicity |

| P32 [57, 73] | a mitochondrial protein |

breast cancer; glioblastoma; prostate cancer; melanoma cancer; lung cancer; pancreatic cancer; colon cancer; malignant pleural mesothelioma |

• expressed glioma cells and tumor derived endothelial cells | • on-target, off-tumor toxicity |

| CSPG4 [74, 75] | a cell surface type I transmembrane protein |

melanoma; triple-negative breast cancer; glioblastoma; mesothelioma; sarcoma |

• expressed on tumor cells, but rarely on normal cells. | • on-target, off-tumor toxicity |

| NKG2DL [76–78] | an activating receptor |

multiple myeloma; ovarian carcinoma; lymphoma; osteosarcoma |

• expressed on tumor cells and cancer stem cells, but rarely on normal cells. | • on-target, off-tumor toxicity |

| CD70 [79, 80] | a type II transmembrane protein |

renal cell carcinoma; leukemia; non-small cell lung cancer; melanoma; glioblastoma |

• expressed on tumor cells, but rarely on normal cells. | • on-target, off-tumor toxicity |

| CD133 [81, 82] | transmembrane glycoprotein |

hepatocellular carcinoma; glioblastoma; pancreatic cancer; gastric cancer; intrahepatic cholangiocarcinomas |

• expressed by cancer stem cells of various epithelial cell origins | • on-target, off-tumor toxicity |

EGFRvIII and EGFR

EGFRvIII is a common tumor-specific mutation widely expressed in GBM and other tumors but rarely expressed in normal tissues [83, 84]. Its expression results from an 801 bp in-frame deletion of exons 2 to 7, resulting in a new glycine residue. This leads to the absence of the ligand-binding domain and low-level constitutive activity of EGFRvIII. This alteration confers tumor specificity, immunogenicity, and oncogenicity to the extracellular domain of EGFRvIII [85]. EGFRvIII establishes a regulatory network of signaling pathways through ligand-independent autophosphorylation and tyrosine kinase activity, which plays a significant role in GBM growth, metastasis, and angiogenesis. Specifically, EGFRvIII enhances the EGFRvIII-PI3K-AKT signaling pathway, the EGFRvIII-Ras-Raf-MEK-ERK/MAPK signaling pathway, and the EGFRvIII-JAK-STAT signaling pathway to promote the proliferation, survival, invasion, and angiogenic capabilities of GBM [86]. Therefore, EGFRvIII has become an important target for CAR-T therapy owing to these characteristics.

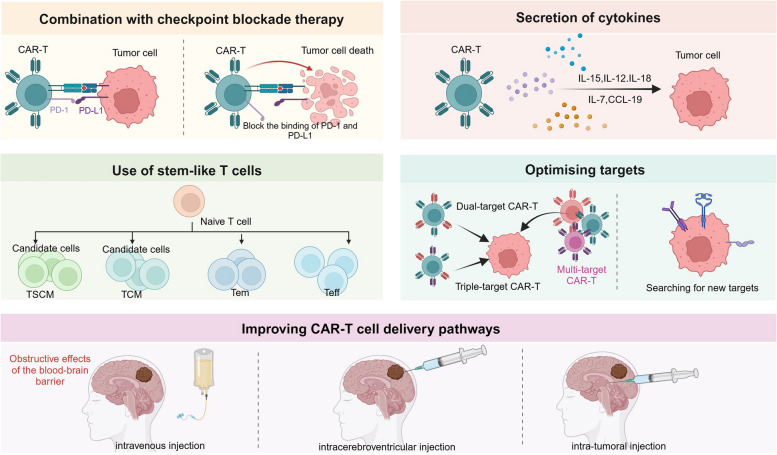

EGFRvIII CAR-T therapy has demonstrated efficacy in GBM murine models; however, its effectiveness is frequently constrained by the tumor’s immunosuppressive microenvironment, limiting the ability to fully control large gliomas. Studies have shown that IL-12 enhances the cytotoxicity of EGFRvIII CAR-T cells and remodels the immune-TME by reducing the proportion of Treg cells and increasing pro-inflammatory CD4 + T cells [87]. These findings suggest that combining IL-12 with EGFRvIII CAR-T therapy may enhance treatment efficacy for GBM. Moreover, inhibition of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) can aid in improving the infiltration and distribution of EGFRvIII CAR-T cells within GBM’s immunosuppressive microenvironment, thereby suppressing tumor growth and extending the survival time of mice [88]. These strategies indicate that the efficacy of EGFRvIII CAR-T cells in treating GBM can be improved by combining immunomodulatory factors and anti-angiogenic agents. However, additional clinical studies are necessary to confirm the efficacy and safety of these approaches and identify the optimal therapeutic regimen to improve clinical outcomes.

Johnson et al. developed a humanized CAR-T cell targeting EGFRvIII, demonstrating its ability to eradicate EGFRvIII-positive GBM in subcutaneous and orthotopic xenograft models [89]. Based on these results, their research center initiated a phase I clinical trial in which 10 patients with recurrent GBM (rGBM) received EGFRvIII CAR-T cell therapy, with a median survival of approximately eight months. One patient showed no disease progression for over 18 months following a single infusion of EGFRvIII CAR-T cells. Among these patients, the incidence of neurological events was 30%, with no cases of CRS or off-tumor toxicity targeting EGFR. Seven patients underwent surgery either within two weeks or two months post-infusion. Tumor specimens showed higher EGFRvIII CAR-T cell concentrations in the brain compared to peripheral blood at two weeks post-infusion but lower levels in the brain than the blood at two months post-infusion. This indicates that EGFRvIII CAR-T cells effectively trafficked to active GBM regions and possibly proliferated in situ, albeit transiently. The study also found that after EGFRvIII CAR-T cell infusion, the expression of immunosuppressive molecules such as indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase 1 (IDO1) and FoxP3 were upregulated, and there was a notable increase in Tregs. These factors collectively initiated an adaptive immune escape mechanism, thereby diminishing the antitumor effects [44]. Despite the poor prognosis of the patients, this study demonstrated the feasibility and safety of manufacturing and infusing EGFRvIII CAR-T cells. Nonetheless, the utilization of EGFRvIII CAR-T cells did not yield clinically significant results in patients with GBM. This study reported that almost all patients experienced transient hematologic toxicity, and two suffered from severe hypoxia. The median progression-free survival (PFS) was only 1.3 months, and the median overall survival (OS) was 6.9 months [90]. This suggests the need for further optimization of treatment regimens and additional research into the long-term efficacy and safety of EGFRvIII CAR-T cells to optimize future treatment strategies.

Although EGFRvIII demonstrates promising targeting capability and therapeutic potential in gliomas, the widespread expression of EGFR and its crucial role in tumorigenesis render it an equally significant target antigen. As a member of the ErbB/HER receptor family, EGFR is a transmembrane glycoprotein consisting of 1,186 amino acids, commonly found in various human cancers, including GBM, non-small cell lung cancer, and breast cancer, where it is frequently overexpressed and activated. However, the ubiquitous presence of EGFR in normal tissues poses a substantial challenge [91], as therapies targeting EGFR may lead to significant off-tumor toxicity [92]. To address this challenge, Dobersberger M et al. developed a CAR-T cell engineering strategy that specifically recognizes the conformational changes in EGFR following ligand activation. This approach enables CAR-T cells to effectively distinguish between tumor cells and unactivated EGFR present in normal tissues, thereby reducing toxicity to normal tissues and enhancing therapeutic specificity for EGFR-positive solid tumors [93]. In constructing a CAR targeting EGFR expression in CNS tumors, researchers selected the single-chain variable fragment (scFv) derived from mAb806. This choice is based on mAb806’s ability to bind both to EGFRvIII and to full-length EGFR expressed due to gene amplification while also exhibiting tumor specificity. This specificity is primarily attributed to the conformational changes in EGFR resulting from overexpression in tumor cells, which expose the binding site of mAb806; conversely, the normal conformation of EGFR in normal cells impedes this binding [94].Through this strategy, EGFR806-CAR T cells exhibited significant anti-tumor activity in mouse models [95]. Moreover, CART.BiTE cell therapy employs a bicistronic structure to co-express both an EGFRvIII-specific CAR and an EGFR-specific BiTE. This approach facilitates the direct targeting of EGFRvIII-positive tumor cells while also recruiting bystander T cells to attack EGFR-positive but EGFRvIII-negative tumor cells, thereby overcoming antigen heterogeneity and reducing toxicity to normal tissues [96].

In summary, while CAR T-cell therapies targeting EGFR and EGFRvIII exhibit significant potential and therapeutic specificity in targeting tumor cells, the widespread expression of EGFR continues to pose a risk of unintended toxicity to normal tissues, highlighting the necessity for further research to optimize treatment strategies that balance efficacy and safety.

IL13Rα2

IL-13Rα2 is expressed in most patients with diffuse high-grade glioma (HGG) but not in normal brain tissue [64] and it is associated with poor tumor prognosis [97, 98]. IL-13Rα2 is a decoy receptor for IL-13, with a higher affinity for IL-13 than IL-13Rα1. Under normal conditions, the IL-13/IL-13Rα complex binds to IL-4Rα to form an IL-13/IL-13Rα/IL-4Rα complex, which activates STAT6 through its intracellular tail. STAT6 subsequently translocates to the nucleus to regulate gene transcription, promoting apoptosis. However, in GBM, IL-13Rα2 competitively binds to IL-13, thereby inhibiting the STAT6 signaling pathway, promoting tumor cell invasion, metastasis, and proliferation, and inhibiting tumor cell apoptosis [64, 99]. Therefore, IL-13Rα2 is considered a tumor marker specifically expressed in various tumors owing to these characteristics.

Previous researchers screened and identified a scFv clone termed 14−1, which exhibits approximately five times higher binding affinity for IL-13Rα2 compared to the previous clone 4−1. The study demonstrated that these scFv-IL-13Rα2-CAR-T cells exhibited significant antitumor activity in vitro and in vivo, effectively killing IL-13Rα2-positive tumor cells while showing low toxicity in non-tumor-bearing mice [100]. These findings indicate that scFv-IL-13Rα2-CAR-T therapy is a potentially effective antitumor treatment modality, warranting further preclinical and clinical investigations.

IL-13Rα2 CAR-T cells were locally injected into resected tumor cavities of three patients with rGBM. Two patients showed evidence of a transient antitumor response. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of one patient post-treatment showed increased necrotic tumor tissue volume at the injection site, and all patients tolerated the treatment well [101]. The largest clinical trial to date for CAR-T cell therapy targeting solid tumors utilized a localized delivery method targeting IL-13Rα2 to treat rGBM and other HGGs. The results indicated that among the 58 patients who received the treatment, 29 (50%) achieved stable disease (SD) or improvement. The median OS for all patients was eight months, with the rGBM subgroup achieving a median OS of 7.7 months. Two cases of partial remission (PR) and one of complete remission(CR) were observed with additional CAR-T treatment cycles. However, 35% of the patients experienced grade 3 or higher toxicities, including one case of grade 3 encephalopathy and one of ataxia [102]. In summary, localized IL-13Rα2-targeted CAR-T therapy demonstrated safety and efficacy in a subset of patients, however, some patients experienced toxic reactions, underscoring the necessity for diligent monitoring and management of potential adverse effects in clinical applications.

Currently, autologous CAR-T cells are widely used; however, their application is limited. Therefore, researchers have developed allogeneic IL-13Rα2 CAR-T cell products for GBM treatment. They employed zinc finger nucleases (ZFN) to genetically engineer CAR-T cells, knocking out the glucocorticoid receptor and resulting in modified CAR-T cells termed GRm13Z40-2 that are resistant to glucocorticoids. GRm13Z40-2 and aldesleukin were intracranially injected into six patients with GBM, in addition to systemic dexamethasone maintenance therapy. Among the six treated patients, four showed signs of transient tumor reduction and/or necrosis at the T-cell injection site [103]. This treatment demonstrated efficacy in certain patients, suggesting that this therapy may constitute an effective strategy for GBM treatment.

HER2

Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) is a tyrosine kinase receptor membrane [104] glycoprotein encoded by the ErbB gene on chromosome 17q21. This gene is classified as a proto-oncogene and typically plays a role in regulating cell growth and division. However, HER2 gene expression dysregulation increases the susceptibility of normal cells and tissues to malignant transformation, leading to tumorigenesis [105]. This process is primarily mediated through the MAPK/ERK and PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathways [106]. HER2 is expressed in approximately 80% of patients with GBM, whereas its expression in normal neural tissue is significantly restricted [107, 108]. Overexpression of the protein encoded by this gene enhances tumor aggressiveness, resulting in poor prognosis and contributing to drug resistance development [65, 109]. Considering its high expression in GBM and its correlation with tumor progression, HER2 is regarded as a critical target for CAR-T therapy, potentially offering novel therapeutic strategies for GBM treatment.

HER2-specific CAR-T cells have been shown to exhibit high selectivity for HER2-positive GBM. One study co-cultured third-generation HER2 CAR-T cells, which contain CD28 and CD137 costimulatory domains, with HER2-positive U251 GBM cells. This study demonstrated that HER2 CAR-T cells exhibited significant cytotoxicity against the tumor cells, accompanied by a significant increase in the secretion levels of IL-2 and IFN-γ [65]. HER2 CAR-T cells exhibited significant anti-tumor activity and robust immune responses in preclinical studies, thereby reinforcing their potential utility for future clinical applications.

A phase 1 dose-escalation clinical study used second-generation HER2-CAR-T (FRP5.CD28.ζ) cells derived from virus-specific T cells (VST), reporting that 17 patients who received CAR-T cell infusions exhibited good tolerability. Among them, eight patients showed signs of PR or SD, with a median OS of 11.1 months for all patients. These findings suggest that HER2-CAR VST infusion is both safe and feasible in clinical applications, demonstrating notable efficacy in treating adult GBM. However, although these cells remained detectable post-infusion, no significant expansion of CAR-T cells was observed in peripheral blood, suggesting a limited in vivo response. Moreover, the assessment of CAR-T therapy in pediatric CNS tumors remains limited, reflecting further constraints on in vivo responses [66]. In a previous study, autologous CD4 + and CD8 + T cells expressing HER2-specific CAR were transduced using a lentivirus and delivered locally via intratumoral or intraventricular administration. Among the three patients who received this treatment, no dose-limiting toxicity occurred, and evidence of CNS immune activation was observed, as indicated by elevated levels of CXCL10 and CCL2 in cerebrospinal fluid and serum, indicating that the treatment was well tolerated [110]. This study provides preliminary evidence for the feasibility of repeated administration of HER2-specific CAR-T cells for CNS tumor treatment in pediatric and young adult populations.

GD2

GD2 is a disialoganglioside prominently expressed in several malignancies, such as neuroblastoma, GBM, and melanoma. GD2 expression in normal tissues is primarily limited to specific cells within the central and peripheral nervous systems, exhibiting relatively low expression levels [111]. GD2 inhibits T cell proliferation, induces apoptosis, and suppresses human CD34 + cell differentiation into mature dendritic cells [68, 112]. Furthermore, GD2 plays a role in tumor cell invasion, angiogenesis, and metastasis [113]. Therefore, GD2 has become a highly attractive tumor target and an excellent candidate for cancer immunotherapy owing to these properties.

A mouse glioma xenograft model showed that mice that received intravenous injections of GD2 CAR-T cells exhibited a longer average survival time of 47 days compared to control and T cell groups, indicating that intravenously administered GD2 CAR-T cells were able to penetrate the brain tumor tissue. Additionally, the research team developed a CAR-T cell capable of secreting IL-15, resulting in more comprehensive and sustained tumor control [111]. However, another study demonstrated that while intratumoral injection of GD2 CAR-T cells was effective, intravenous administration was not, which can be attributed to the lack of cross-reactivity with GD2 in mice [114]. Further studies are required to determine the optimal administration route for GD2 CAR-T cells. Additionally, studies have shown that radiation therapy can enhance the infiltration and expansion of GD2 CAR-T cells within the TME, thereby boosting the antitumor immune response [115]. This suggests that combining radiotherapy with CAR-T cell therapy may be a promising strategy for enhancing the treatment efficacy of malignant tumors, necessitating further investigation in subsequent studies. DMG with H3K27M mutations is a fatal CNS tumor in children [116]. Preclinical studies have demonstrated that GD2 CAR-T cells can significantly eliminate tumors in patient-derived H3K27M + DMG orthotopic xenograft models [117], offering new hope for the treatment of these deadly childhood cancers.

Researchers have developed and applied fourth-generation CAR-T cells (4S CAR) incorporating CD28 transmembrane and cytoplasmic regions, intracellular TRAF-binding domain of the co-stimulatory molecule 4-1BB, intracellular structural domain of the CD3z chain, and suicide-inducing caspase 9 gene. Overall, eight patients with GD2-positive GBM were enrolled in this study. All patients underwent lymphodepletion prior to CAR-T cell administration, with CAR-T cells delivered either via intravenous infusion alone or in combination with intracavitary injection. The results demonstrated that 4S CAR-T cells persisted at a low copy number in peripheral blood for 1–3 weeks following expansion. Moreover, 50% of these patients (4/8) experienced PR within 3–24 months post-infusion, 37.5% (3/8) exhibited progressive disease (PD) within 6–23 months post-infusion, and 12.5% (1/8) had stable disease at four months post-infusion. The median OS for the overall patient cohort was 10 months, and no serious adverse events were reported [118]. These findings suggest that 4S CAR-T cells possess a favorable safety and tolerability profile for the treatment of patients with GD2-positive GBM. However, the OS rate remains limited and warrants further investigation with an expanded sample size. Supported by preclinical studies, GD2-CAR-T therapy was administered to patients with H3K27M-mutant DIPG and DMG of the spinal cord. Among the four enrolled patients, three exhibited clinical and radiographic improvements, in addition to increased levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines in the blood and cerebrospinal fluid, suggesting effective interaction between CAR-T cells and tumor cells. Patients experienced CNS symptoms and signs related to CAR-T therapy; nevertheless, these toxic effects were reversible with appropriate management strategies [119]. Overall, these findings highlight the considerable potential of GD2-CAR-T therapy in enhancing the clinical outcomes of patients with DIPG and DMG. A previous study developed C7R-GD2 CAR-T cells expressing the IL-7 receptor (IL-7R) to enhance GD2 CAR-T cell efficacy in treating CNS tumors. This modification enabled C7R-GD2 CAR-T cells to activate downstream signaling pathways independently of IL-7, thereby enhancing the effectiveness of CAR-T therapy. Among the 11 patients enrolled in the study, eight were diagnosed with H3K27-mutant DMG. Patients receiving GD2 CAR-T treatment exhibited neurofunctional improvement for less than three weeks, with no cases of CRS or tumor inflammation-associated neurotoxicity (TIAN). TIAN represents a form of neuronal dysfunction resulting from localized inflammation and the consequent transient edema, which contrasts with the generalized and diffuse cerebral edema seen in ICANS. TIAN can be categorized into two types: Type 1 primarily manifests as inflammatory edema, resulting in elevated intracranial pressure and limited mechanical spaces; Type 2 indicates local inflammation triggered by immunotherapy, subsequently leading to functional impairment in specific neural regions [120]. In contrast, patients treated with C7R-GD2 CAR-T cells experienced a median duration of neurofunctional improvement of five months, with 88% achieving PR or SD. Additionally, the PFS of patients who received C7R-GD2 CAR-T cells was significantly longer than that of those who received GD2 CAR-T cells [121]. These results suggest that C7R-GD2 CAR-T therapy exhibits excellent clinical efficacy in patients with CNS tumors.

B7H3

B7H3, also referred to as CD276, is a highly conserved type I transmembrane protein encoded by human chromosome 15, comprising 316 amino acids [122, 123]. B7H3 exists in two human isoforms owing to variations in its extracellular domain: 2IgB7-H3 and 4IgB7-H3 [70]. B7H3 is highly expressed in a variety of tumor cells and within TMEs, particularly during pathological angiogenesis. B7H3 expression is markedly elevated in GBM, neuroblastoma, and ovarian cancer [71, 124], where it is strongly associated with tumor malignancy and poor prognosis [125]. B7H3 is expressed in certain peritumoral tissues; however, its expression remains low and is either minimally detectable or nearly absent in normal tissues and organs [126]. It enhances cancer cell invasiveness by regulating the JAK2/STAT3 signaling pathway and facilitates angiogenesis in the TME by upregulating vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGFA) expression [70]. Therefore, B7H3 has been identified as a promising therapeutic target for the selective disruption of tumors and their vascular networks.

A third-generation B7H3 CAR-T cell was engineered, and its potent cytotoxicity on primary GBM cells and GBM cell lines was demonstrated through in vitro assays. The median survival in the B7H3 CAR-T cell-treated group was significantly prolonged compared to the control group in xenograft models, However, tumor recurrence was observed in the brains of mice receiving CAR-T cell therapy, suggesting that this may be due to insufficient CAR-T cell dosing [125]. Therefore, it is crucial to pay special attention to the dosing of CAR-T cells to optimize therapeutic outcomes. Similarly, another study demonstrated that B7H3 is overexpressed in GBM specimens, and CAR-T cells targeting B7H3 can effectively inhibit tumor cell proliferation [127]. These studies demonstrated that B7H3 CAR-T cells exhibit significant anti-tumor effects in GBM treatment; nevertheless, a potential to further enhance therapeutic efficacy remains. Recent research indicates that pre-treatment with radiation before B7H3 CAR-T cell infusion can significantly improve therapeutic efficacy in solid tumor models [128]. Moreover, oncolytic adenoviruses carrying CXCL11 can enhance the efficacy of B7H3 CAR-T cells in GBM treatment by remodeling the immunosuppressive microenvironment [129]. Researchers have developed a novel B7H3 CAR-T cell incorporating the transmembrane and immunoglobulin domain–containing 2 (TMIGD2) co-stimulatory domain, which is a co-stimulatory factor for T cells and NK cells, to further optimize CAR-T therapy. B7H3 CAR-T cells with the TMIGD2 co-stimulatory domain exhibited superior anti-tumor activity, enhanced expansion, and improved persistence compared to traditional CAR-T cells incorporating CD28 and/or 4-1BB co-stimulatory domains. The underlying mechanisms include maintenance of mitochondrial metabolism, reduced cytokine production, decreased cell exhaustion, and an increased proportion of central memory and CD8 + T cells [130]. This CAR-T cell type exhibits notable advantages in combating solid tumors, thereby warranting further research and development.

Intracranial administration of B7H3 CAR-T cells in patients with DIPG has shown good tolerance, with B7H3 CAR-T cells persisting in the cerebrospinal fluid, showing evidence of immune activation. Notably, one patient exhibited continuous clinical and radiological improvement over a 12-month follow-up period, without experiencing dose-limiting toxicity [131]. Vitanza et al. reported data from a clinical trial involving 21 pediatric patients with DMG who received B7H3 CAR-T cell therapy. Meanwhile, Mahdi et al. presented results from a clinical trial at Stanford University, in which nine patients with DMG were treated with B7H3 CAR-T cells. Of these, four (44%) experienced tumor reduction of more than 50%, and one achieved CR [132]. These findings suggest that B7H3 CAR-T cells have potential in glioma treatment, as evidenced by significant tumor shrinkage and complete remission in some patients.

EphA2

EphA2 is a tyrosine kinase receptor that binds ligands of the EphrinA family [133]. It is highly expressed in tumors such as GBM, breast cancer, lung cancer, and melanoma, whereas its expression is limited in healthy tissues [72]. Elevated EphA2 expression correlates with poor prognosis, reduced survival, and increased metastasis rates in patients with tumors. In cancer cells, EphA2 exhibits a dual role: its ligand-dependent function inhibits cancer cell invasion and migration upon ligand binding, whereas its ligand-independent kinase activity involves overexpressed EphA2 altering downstream signaling pathways through dimerization with E-cadherin, EGFR, HER2, and integrins. Additionally, EphA2 can be activated through phosphorylation events mediated by AKT/RSK/PKA [72, 134], thereby promoting tumor progression.

CAR-T cells targeting EphA2 have shown significant antitumor effects in preclinical studies [135]. A research team developed two third-generation EphA2 CAR-T cells: EphA2-a CAR-T and EphA2-b CAR-T. In vitro experiments demonstrated that both CAR-T cells could be activated by EphA2-positive tumor cells, with EphA2-a CAR-T exhibiting significantly higher tumor-killing efficiency compared to EphA2-b CAR-T. In vivo experiments similarly demonstrated that both CAR-T cells significantly prolonged mouse survival, which may be attributed to the modulation of the CXCR-1/2 signaling pathways and moderate increases in IFN-γ levels. However, the reduced efficacy of EphA2-b CAR-T may attributed to excessive IFN-γ expression, which leads to PD-L1 upregulation in GBM cells and consequently diminishes the antitumor effect [136]. These findings indicate that EphA2 CAR-T cell therapy has the potential for GBM treatment.

A clinical trial of three patients with rGBM showed that EphA2 CAR-T therapy resulted in SD in one patient and PD in two patients, with OS ranging from 86–181 days. Two patients developed grade 2 CRS accompanied by pulmonary edema, which resolved after dexamethasone treatment, indicating favorable tolerability following EphA2 CAR-T infusion. However, the therapeutic effect was suboptimal, and its duration was relatively brief, with the occurrence of pulmonary edema suggesting potential on-target off-tumor toxicity [137]. Consequently, further optimization is required to improve its safety and durability, as well as to broaden its potential for clinical application.

P32

P32, also known as gC1qR/HABP/C1qBP, is a mitochondrial protein that acts as a receptor for CGKPK and is expressed on surfaces of tumor cells and endothelial cells involved in tumor angiogenesis [73, 138]. Rousso Noori et al. demonstrated that P32 is specifically expressed in GBM cells, making it a promising target for CAR-T therapy. Further studies showed that P32 CAR-T cells can specifically recognize and eliminate P32-expressing glioma cells and tumor-derived endothelial cells in vitro and significantly inhibit tumor growth in xenograft and syngeneic mouse models [57]. These findings indicate that P32 CAR-T cells exhibit both antitumor activity and anti-angiogenic effects. Therefore, P32 CAR-T cells represent a promising therapeutic option for patients with GBM, although no related clinical trials have been reported to date.

CSPG4

Chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan 4 (CSPG4) is a type I transmembrane protein widely expressed across multiple malignant tumors, including melanoma, triple-negative breast cancer, mesothelioma, and sarcoma [74]. Notably, CSPG4 is expressed in up to 67% of GBM, whereas its expression is more limited in normal tissues, and it is strongly correlated with reduced patient survival [75, 139, 140]. CSPG4 CAR-T cells exhibited potent inhibitory effects on a glioblastoma neurosphere (GBM-NS) model in vitro and in vivo. In GBM-NS models with low CSPG4 expression, microglial cells surrounding the tumor induced CSPG4 upregulation on the tumor cell surface by releasing TNF-α, thereby enhancing the therapeutic efficacy of CAR-T cells [139]. Preclinical studies demonstrated significant efficacy of CSPG4 CAR-T in GBM treatment; however, further clinical trial data is required to validate its efficacy and safety.

NKG2DL

Natural killer cell group 2 member D (NKG2D) is an activating cell surface receptor [76] primarily expressed on immune cells, including NK cells and CD8 + T cells. Its ligands (NKG2DLs) consist of eight distinct proteins in humans, including major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I chain-related molecules (MICA, MICB) and six UL16-binding proteins (ULBPs) [141]. These ligands are widely expressed on the surface of GBM cells, cancer stem cells, and other tumor cells [77]. Preclinical studies reveal that murine NKG2D CAR-T cells demonstrate strong cytolytic activity against glioma cells in vitro, significantly prolonging survival in a glioma mouse model, with additional long-term protective effects. Moreover, local radiotherapy enhanced the migration of NKG2D CAR-T cells to the tumor site, thereby enhancing their cytotoxic efficacy [142]. Meister et al. developed mRNA-based CAR-T cells co-expressing the NKG2D receptor and pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-12 and IFNα2, which efficiently killed mouse glioma cell lines in vitro and exhibited anti-tumor activity in a glioma mouse model with intravenous and intratumoral administration [143]. Further studies demonstrated that human CAR-T cells expressing NKG2D could target GBM and cancer stem cells, efficiently lysing these cells [78]. NKG2D CAR-T cells have shown significant efficacy against gliomas in preclinical studies; however, no clinical trial data have been reported to date, necessitating further clinical validation of these findings.

CD70

CD70, a member of the tumor necrosis factor superfamily and ligand for CD27, is overexpressed in renal cell carcinoma, leukemia, non-small cell lung cancer, melanoma, and GBM [45, 144], where its high expression is strongly correlated with reduced patient survival [145]. The mechanisms underlying this association may involve the induction of apoptosis in CD8+ T cells, recruitment of TAMs to the GBM microenvironment resulting in immunosuppression, and participation in glioma chemokine production [79, 145]. CD70 is transiently expressed in activated T cells, B cells, and mature dendritic cells, with very low expression levels in most normal tissues. Notably, CD70 expression is significantly elevated in samples from patients with recurrent GBM compared to primary GBM.

Human- and murine-derived CD70 CAR-T cells demonstrated tumor regression in in vitro studies, human xenograft models, and syngeneic in situ glioma models. Researchers developed CD70 CAR-T cells modified with the rabies virus glycoprotein-derived RVG29 peptide (70R CAR-T) to address the challenge of CD70 CAR-T cells penetrating the BBB. In vitro cellular experiments demonstrated that 70R CAR-T cells exhibited markedly increased cytotoxic activity against CD70-positive glioma cells. Furthermore, 70R CAR-T cells in vivo demonstrated improved capability in crossing the BBB and enhanced therapeutic potency compared to conventional CD70 CAR-T cells. However, it is crucial to acknowledge that the RVG29 peptide, being an exogenous substance, may be identified by the host immune system as “non-self” potentially inducing both humoral and cellular anti-CAR immunity, which could consequently restrict its overall efficacy and influence the persistence of CAR-T cells. Despite these concerns, the study provided preliminary insights into the enhanced killing mechanisms of 70R CAR-T cells, which exhibited a lower apoptosis rate, increased proportion of central memory T cells (TCM), and decreased proportion of effector memory T cells (TEM), leading to improved phenotypic characteristics [80]. Nevertheless, the generalizability of these research findings is constrained and necessitates further validation. Therefore, future research should investigate the immunogenicity of the RVG29 peptide more comprehensively and evaluate its safety and tolerability across diverse patient populations to ensure that the clinical application of 70R CAR-T cells is not impeded by immunogenicity concerns.

CD133

CD133 is a transmembrane glycoprotein widely recognized as a crucial marker of malignant tumor recurrence and poor prognosis, and it is expressed in a variety of malignant tumors, including hepatocellular carcinoma, pancreatic cancer, and gastric cancer [81]. In addition, CD133 is also a marker for tumor stem cells (CSCs) and endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs) [146]. In GBM, CD133 expression is significantly elevated compared to low-grade gliomas, and studies have shown that GBM patients with high CD133 expression have a poorer prognosis [147]. In a humanized mouse model of GBM, CD133 CAR-T cells demonstrated robust anti-tumor activity and significant therapeutic efficacy while not triggering acute systemic toxicity by intratumoral injection [147]. However, data from clinical trials targeting CD133 CAR-T cells for the treatment of GBM remain unpublished.

multi-targeted CAR-T

Given the role of TGF-β in the immunosuppressive microenvironment, Chang ZL, et al. designed CAR-T cells to simultaneously target GBM and TGF-β within the TME. These CAR-T cells directly kill tumor cells by targeting IL-13Rα2 and convert TGF-β from an immunosuppressant to an immunostimulant through TGF-β targeting [148]. Compared to traditional IL-13Rα2-targeting CAR-T cells, the IL-13Rα2/TGF-β CAR-T cells demonstrate enhanced efficacy against GBM in mouse models and possess the ability to resist and remodel the immunosuppressive microenvironment [149]. What’s more, the research team has developed a dual-target CAR-T cell therapy for GBM, named CART-EGFR-IL3Rα2 cell therapy. This therapy administers CAR-T cells to the cerebrospinal fluid via intrathecal injection. Results indicated that in the six patients who received the dual-target CAR-T cell therapy, MRI scans showed a reduction in brain tumor size, with some patients maintaining this reduction for several months [150]. This research offers new insights and methods for GBM immunotherapy, potentially improving patient prognosis. However, further large-scale clinical trials are necessary to evaluate the long-term safety and efficacy of this therapy.

Although EGFRvIII is highly specific, it exhibits heterogeneous expression [89]. CAR-T cells that selectively target this antigen can allow antigen-negative tumor cells to escape [151], leading to insufficient efficacy. Some antigens, such as EphA2 and IL13Rα2, are uniformly expressed in GBM cells; however, they have specificity drawbacks as they are also expressed in some healthy tissues, such as the liver, kidneys, and esophagus [152]. Targeting such antigens with CAR-T cells poses the potential risk of attacking normal tissue cells. To address this challenge, researchers have designed SynNotch-CAR T cells that recognize multiple antigen combinations. The mechanism involves first activating the expression of the CAR through a synNotch receptor, which recognizes the tumor-specific but heterogeneously expressed EGFRvIII antigen. Upon recognition, the engaged CAR undergoes cleavage, leading to the transcriptional upregulation of a second CAR. This second CAR is responsible for killing cancer cells by recognizing antigens such as EphA2 or IL13Rα2, which are uniformly expressed in cancer cells but not tumor-specific [153, 154]. In a xenogeneic GBM mouse model, the infusion of synNotch-CAR T cells demonstrated significantly higher antitumor efficacy and CAR-T cell persistence compared to traditional constitutively expressed CAR-T cells. Additionally, a higher proportion of CAR-T cells remained in the naïve/stem cell memory state, thereby reducing their exhaustion levels [154]. In addition, SynNotch-CAR T cells have effectively addressed the limitations of traditional CAR-T therapy by employing a multi-antigen recognition strategy. They have demonstrated enhanced therapeutic efficacy and improved safety profiles, offering novel approaches for GBM treatment. However, one potential limitation of the SynNotch-CAR strategy is the risk of on-target off-tumor activity. If T cells expressing the second CAR leave the TME, they could potentially target normal tissues expressing EphA2 or IL13Rα2, leading to off-target effects. This issue underscores the necessity for a careful balance between antitumor efficacy and safety. To enhance the specificity and safety of CAR-T cell therapy, the research team developed two CARs that target distinct tumor antigens. This strategy’s core involves utilizing distinct signaling chains to transmit cytotoxic and proliferative signals, thereby achieving a synergistic effect. Notably, the activation of CAR-T cells depends on the simultaneous expression of both antigens by target tumor cells, effectively minimizing the risk of harming normal tissues [155]. This approach provides new insights for developing CAR-T therapies aimed at targeting malignant tumors of the CNS in the future.

In summary, we systematically reviewed the progress of preclinical and clinical studies of CAR-T cells in the treatment of gliomas, and CAR-T cell therapies for different targets showed their respective therapeutic potentials and challenges in targeting gliomas. These findings have helped us to gain a clearer understanding of the effectiveness and limitations of different targets in the treatment of gliomas. To further explore the practical clinical application of CAR-T cell therapy in glioma treatment, we summarised the data from the current preclinical studies and clinical studies, which are detailed in Tables 3 and 4. These data provide an important basis for evaluating the clinical efficacy of CAR-T cell therapy for gliomas and provide valuable guidance for future research directions and clinical practice.

Table 3.

Preclinical study outcomes of CAR-T cell therapy for gliomas and medulloblastoma

| Target | Disease type | Experimental Approach | Time | The structure of CAR-T cells |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EGFRvIII | GBM | in vitro and in vivo | 2021 [87] | EGFRvIII scFv-CD8stk-mCD28-CD3ζ |

| EGFRvIII | GBM | in vitro and in vivo | 2023 [88] | EGFRvIII scFv-CD8α(H/M)-CD28-CD3ζ-Myc tag |

| EGFRvIII | GBM | in vitro and in vivo | 2015 [89] | 3C10scFv-CD8α hinge-4-1BB-CD3ζ |

| IL13Rα2 | GBM | in vitro and in vivo | 2024 [100] | CD8α SP-scFv IL-13Rα2-CD8α hinge-CD28 TM-CD28cyto-4-1BB-CD3ζ |

| HER2 | GBM | in vitro | 2019 [65] | HER2 scFv-hinge-CD28 and CD137-CD3ζ |

| GD2 | GBM | in vitro and in vivo | 2022 [111] | NA |

| GD2 | GBM | in vitro and in vivo | 2020 [115] | GD2 scFv-hinge-CD28 -CD3ζ |

| GD2 | glioma | in vivo | 2018 [117] | GD2 scFv-CD8 TM-4-1BB -CD3ζ |

| B7H3 | DIPG | in vitro and in vivo | 2024 [130] | B7H3 scFv-CD8α(H/M)-TMIGD2 -CD3ζ-P2A-hEGFRt |

| B7H3 | GBM | in vitro and in vivo | 2023 [129] | B7H3 scFv-CD8α hinge-4-1BB -CD3ζ-mCherry |

| EphA2 | GBM | in vitro and in vivo | 2018 [135] |

EphA2 scFv-CD28 TM-CD28 -CD3ζ; EphA2 scFv-CD8 TM-4-1BB -CD3ζ; EphA2 scFv-CD28 TM-CD28 and 4-1BB -CD3ζ |

| EphA2 | GBM | in vitro and in vivo | 2021 [136] | EphA2 scFv-a-CD28 TM-CD28 and 4-1BB -CD3ζ; EphA2 scFv-b-CD28 TM-CD28 and 4-1BB -CD3ζ |

| P32 | GBM | in vitro and in vivo | 2021 [57] | P32 scFv-CD28-FcRγ -P2A-mCherry |

| CSPG4 | GBM-NS | in vitro and in vivo | 2018 [139] | CSPG4 scFv-CD8α(H/M)-CD28/4-1BB/CD28 and 4-1BB-CD3ζ |

| NKG2DL | glioma | in vitro and in vivo | 2022 [143] | NA |

| NKG2DL | GBM | in vitro and in vivo | 2019 [78] | NKG2D ECD-CD8 hinge and TM- 4-1BB -CD3ζ |

| CD70 | GBM | in vitro and in vivo | 2018 [79] |

hCD27-4-1BB-CD3ζ-P2A-tT; mCD27-4-1BB-CD3ζ-P2A-tT |

| CD70 | GBM | in vitro and in vivo | 2021 [45] | CD70 scFv-CD8α-4-1BB -CD3ζ |

| CD70 | GBM | in vitro and in vivo | 2023 [80] | RVG29-CD70scFv-CD8 hinge-4-1BB -CD3ζ |

| CD133 | GBM | in vitro and in vivo | 2020 [147] | CD133scFv-Myc tag-CD8α-CD28 -CD3ζ |

|

IL-13Rα2 TGF-β |

GBM | in vitro and in vivo | 2024 [149] | NA |

|

EGFRvIII EphA2 IL13Rα2 |

GBM | in vitro and in vivo | 2021 [154] | EGFRvIII scFv, EphA2 scFv and IL13 mutein scFv or IL13 mutein-G4Sx4-EphA2 scFv-CD8α hinge-4-1BB-CD3ζ |

| HER2 | MB | in vitro and in vivo | 2018 [156] | 4D5 anti-HER2 scFv-αCD8 hinge TM-4-1BB -CD3ζ |

| GD2 | MB | in vitro and in vivo | 2024 [157] | FKBP12-F36V-iCasp9-scFv(14g2a)-CD28TM-CD28 and 4-1BB -CD3ζ |

| B7H3 | MB | in vitro and in vivo | 2019 [158] | CD276 scFv-CD8 TM-4-1BB -CD3ζ |

| B7H3 | MB | in vitro and in vivo | 2021 [159] | B7H3 scFv-CD28(H/TM)-CD28 -CD3ζ |

GBM Glioblastoma, MB Medulloblastoma, scFv Single-chain variable fragment, TM Transmembrane

Table 4.

Clinical study outcomes of CAR-T cell therapy for gliomas

| Disease type | Target | Registration Number | Research Phase | Partici-pants | Time | Research Institution | Authors | Clinical outcomes | Adverse events |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GBM | EGFRvIII | NCT02209376 | phase 1 | 10 | 2017 | Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, USA | O’Rourke DM, et al [44] | Median OS: 8 months |

CRS:0; ICANS:30%; off-tumor toxicity:0 |

| GBM | EGFRvIII | NCT01454596 | phase 1 | 18 | 2019 | National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health | Goff SL, et al [90] |

Median PFS: 1.3 months; Median OS: 6.9 months |

severe hypoxia:2 patients; transient hematologic toxicities: 100% |

| GBM | IL13Rα2 | NCT00730613 | phase 1 | 3 | 2015 | City of Hope Beckman Research Institute and Medical Center, USA | Brown CE, et al [101] | Evidence of a transient antitumor response was observed in two patients. |

107 or 5×107 T cell dose: Grade 3 or higher adverse events:0; 108 T cell dose: one Grade 3 headache, one Grade 3 neurologic- event |

| GBM | IL13Rα2 | NCT02208362 | phase 1 | 1 | 2016 | City of Hope Beckman Research Institute and Medical Center, USA | Brown CE, et al [13] | PFS:7.5 months | toxic effects of grade 3 or higher: none |

| high-grade glioma | IL13Rα2 | NCT02208362 | phase 1 | 58 | 2024 | City of Hope Beckman Research Institute and Medical Center, USA | Brown CE, et al [102] |

Median OS: 8 months; the subset with rGBM:7.7 months; SD or better:50%; PR:2 patients; CR: 1 patient |

Grade 3 and above toxicities:35% |

| GBM | IL13Rα2 | NCT01082926 | phase 1 | 6 | 2022 | City of Hope Beckman Research Institute and Medical Center, USA | Brown CE, et al [103] | four showed signs of transient tumor reduction and/or necrosis | All ≤ grade 3 |

| GBM | HER2 | NCT01109095 | phase 1 | 17 | 2017 | Baylor College of Medicine, Houston Methodist Hospital, and Texas Children’s Hospital, USA | Ahmed N, et al [66] |

Median OS: 11.1 months; PR and SD:8 patients |

NA |

| CNS tumors | HER2 | NCT03500991 | phase 1 | 3 | 2021 | Seattle Children’s Research Institute, USA | Vitanza NA, et al [110] | well tolerated | headache, pain or transient worsening of a baseline neurologic deficit |

| GBM | GD2 | NCT03170141 | phase 1 | 8 | 2023 | Shenzhen Hospital, Southern Medical University, China | Liu Z, et al [118] |

Median OS: 10 months; 3–24 months:50%PR; 6–23 months:37.5% PD; 4 months:12.5% SD |

No severe adverse effects were observed |

| DIPG or spinal cord diff-use DMG | GD2 | NCT04196413 | phase 1 | 4 | 2022 | Stanford Center for Cancer Cell Therapy, Stanford Cancer Institute, Stanford University, USA | Majzner RG, et al [119] | Clinical and radiographic improvement:75% | TIAN |

| H3K27M-mutated DMG; MD; AT/RT | GD2 | NCT04099797 | phase 1 | 11 | 2024 | Baylor College of Medicine, USA | Lin FY, et al [121] |

C7R-GD2 CAR-T: a median duration of neurofunctional improvement:5 months, PR and SD:88%; GD2 CAR-T: duration of neurofunctional improvement for less than 3 weeks |

C7R-GD2 CAR-T: 1 TIAN:88%; CRS:75%; GD2 CAR-T: no CRS and TIAN |

| DIPG | B7H3 | NCT04185038 | phase 1 | 5 | 2023 | Seattle Children’s Research Institute, USA | Vitanza NA, et al [131] | one patient exhibited continuous clinical and radiological improvement over a 12-month follow-up period | headache (3/3), nausea/vomiting (3/3), and fever (3/3),gait disturbance, dysphagia |

| GBM | EphA2 | NCT03423992 | phase 1 | 3 | 2021 | Xuanwu Hospital, Capital Medical University, China | Lin Q, et al [137] |

SD:1 patient; PD:2 patients; OS:86-181d |

2 CRS accompanied by pulmonary edema: 2 patients |

| GBM | EGFRvIII and IL13Rα2 | NCT05168423 | phase 1 | 6 | 2024 | University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine, USA. | Bagley SJ, et al [150] |

reductions in tumor size:100%; none met criteria for ORR |

Dose-limiting toxicity: 1 patient |

GBM Glioblastoma, OS Overall survival, CRS Cytokine release syndrome, ICANS Immune effector cell-associated neurotoxicity syndrome, PFS Progression-free survival, rGBM Recurrent glioblastoma, SD Stable disease, PR Partial response, CR Complete response, PD Progressive disease, TIAN Tumor-associated inflammatory adverse events, ORR Overall response rate

Medulloblastoma

Medulloblastoma(MB) is one of the most prevalent malignant brain tumors in children and is classified into four distinct subtypes based on molecular characteristics: WNT, SHH, G3, and G4 [160]. WNT MBs are typically associated with mutations in the CTNNB1 gene, nuclear immunohistochemical staining positive for β-catenin, and monosomy six (deletion of one copy of chromosome 6 in the tumor). These changes are associated with the aberrant activation of the WNT signaling pathway, which is characterized by this subtype having the most favorable prognosis among all MBs. SHH MBs are strongly associated with the abnormal activation of the Sonic Hedgehog signaling pathway. Studies have demonstrated that individuals with mutations in the PTCH, SMO, or SUFU genes are predisposed to this subtype, with the most common histological subtypes being the classic and desmoplastic variants. In comparison, the tumorigenic molecular mechanisms of the G3 group of MBs remain unclear, characterized by MYC amplification, which is rarely observed in adults and primarily occurs in infants and children, representing the worst prognosis among all subtypes. The G4 group of MBs is the most prevalent molecular subtype, accounting for approximately 35% of all MBs, with characteristic mutations frequently affecting the KDM6A gene [161, 162]. Standard treatment options include surgical intervention, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy; however, these approaches frequently result in considerable neurological and endocrine damage [163]. Research indicates that MB exhibits high expression levels of EphA2, HER2, and IL-13Rα2 [164]. These antigens represent promising targets for CAR-T cell immunotherapy, offering new avenues for the treatment of MB.

HER2

Studies have demonstrated that both MB and posterior fossa A(PFA) ependymoma specifically overexpress EphA2, HER2, and IL-13Rα2 [164]. HER2 CAR-T cells exhibited significant anti-tumor activity in treating MB and effectively cleared xenografted tumors in a mouse model via both regional and intravenous administration, with the dose required for regional administration being significantly lower than that for intravenous. Furthermore, non-human primate studies confirmed that ventricular administration of HER2 CAR-T cells was feasible and safe, with no systemic toxicity observed [156]. These findings provide strong support for future clinical trials involving direct injection of HER2 CAR-T cells into the CSF for patients with MB. Treatment with EphA2-targeted CAR-T cells significantly extended the survival of tumor-bearing mice and effectively inhibited MB metastasis to the spinal cord. Repeated local administration via intraventricular injection resulted in improved therapeutic outcomes, with EphA2 CAR-T monotherapy showing superior efficacy compared to the EphA2/HER2/IL-13Rα2 trivalent CAR-T therapy. Additionally, the study concluded that the combination of Azacytidine with CAR-T cells further enhances their efficacy in tumor clearance in mice [164]. However, as this study did not comprehensively evaluate systemic toxicity, additional research is warranted to thoroughly investigate its long-term safety and potential adverse effects.

GD2

GD2 is a potential antigen for MB and is expressed in approximately 80% of MB patient samples, despite its heterogeneous expression [157]. In vitro co-culture assays demonstrated that GD2 CAR-T cells exhibited significant anti-tumour activity. In the NSG mouse model of MB, intravenous injection of GD2 CAR-T cells significantly inhibited tumor growth and prolonged the OS of mice. To mitigate the potential toxicities associated with GD2 CAR-T cells, the researchers introduced a suicide gene, inducible caspase 9 (iC9), into the CAR-T cells as a safety switch [165]. The gene can be activated by the chemical dimeriser AP1903, which rapidly eliminates CAR-T cells from circulation and the brain, thereby reducing the risk of toxicity [157]. The results of this study provide robust evidence supporting the application of GD2 CAR-T cells in clinical trials.

B7H3

B7H3 is highly expressed in pediatric CNS tumor tissues. CAR-T cells targeting B7H3 were significantly activated when co-cultured with MB cell lines in vitro, as evidenced by the secretion of cytokines including TNF-α, IL-2, and IFN-γ. Furthermore, studies demonstrated that tail vein-injected B7H3 CAR-T cells crossed the BBB and successfully infiltrated the brain of DAOY MB and c-MYC-amplified group 3 MB xenograft mouse models, resulting in tumor clearance and significantly prolonged survival [158]. Local administration and systemic infusion of B7H3 CAR-T cells in a patient derived orthotopic xenograft (PDOX) MB mouse model resulted in significantly increased mouse survival rates [159]. These findings indicate that B7H3 CAR-T cells exhibit substantial anti-tumor efficacy and demonstrate effective BBB penetration, offering robust evidence for their potential application in treating pediatric MB. Nonetheless, additional clinical trials are required to confirm their long-term efficacy and safety.

Tumours of the lymphohematopoietic system involving the CNS

Non-hodgkin lymphoma

Central nervous system lymphoma (CNSL), comprising primary CNSL (PCNSL) and secondary CNSL (SCNSL), has a worse prognosis than extracerebral lymphoma, with a 5-year survival rate of only 29.9%. The overall prognosis remains poor, despite advances in high-dose cytarabine and methotrexate treatments, which have significantly improved survival [166]. Moreover, patients with CNSL are frequently excluded from key clinical trials owing to concerns about severe adverse events, such as ICANS, that may arise following CAR-T therapy [167]. These challenges highlight the particularly complex nature of CNSL treatment.