ABSTRACT

Precise mosquito identification is integral to effective arbovirus surveillance. Nonetheless, the conventional morphological approach to identifying mosquito species is laborious, demands expertise and presents challenges when specimens are damaged. DNA barcoding offers a promising alternative, surmounting challenges inherent in morphological identification. To integrate DNA barcoding into arbovirus surveillance effectively, a robust dataset of mosquito barcode sequences is required. This study established a comprehensive repository of Cytochrome Oxidase I (COI) barcodes, encompassing 177 samples representing 45 mosquito species from southern and northern Western Australia (WA), including 16 species which have not been previously barcoded. The average intraspecific and interspecific genetic distances were 1% and 6.8%, respectively. Anopheles annulipes sensu lato had the highest intraspecific distance at 9.1%, signifying a genetically diverse species. While validating the potential of COI barcodes to accurately differentiate mosquito species, we identified that some species pairs have low COI divergence. This includes Aedes clelandi and Ae. hesperonotius, Tripteroides atripes and Tp. punctolaeralis and Ae. turneri and Ae. stricklandi. In addition, we observed ambiguity in identification of the members of Culex sitiens subgroup (Cx. annulirostris, Cx. palpalis and Cx. sitiens) and three members of Cx. pipiens complex (Cx. australicus, Cx. globocoxitus, Cx. quinquefasciatus). In summary, despite presenting challenges in the identification of some mosquito species, the COI barcode accurately identified most of the species and generated a valuable resource that will support the WA arbovirus surveillance program and enhance public health intervention strategies for mosquito‐borne disease control.

Keywords: Culicidae, DNA barcoding, mitochondrial COI, mosquitoes, Western Australia

DNA barcodes of 45 species of Western Australian mosquitoes sampled across a wide spatial range, were obtained using the universal COI barcode. Most species exhibited adequate genetic diversity, enabling reliable species identification. The barcodes generated in this study can serve as valuable resources for mosquito surveillance programs, aiding in species identification, enhancing our understanding of evolutionary relationships and identifying patterns of associations among different mosquito species.

1. Introduction

Accurate mosquito identification is of utmost importance for effective arbovirus surveillance, serving as a crucial prerequisite for the successful control of vector‐borne diseases. Traditional methods of field‐collected mosquito identification primarily rely on Linnaean taxonomic approaches, centred around the meticulous observation of morphological characteristics. These methods, often reliant on dichotomous keys, are notorious for their time‐intensive nature and demanding years of specialised training for reliable application. Moreover, the accuracy of morphological identification hinges on the preservation of sample integrity, a criterion that is not consistently attainable in the field. The potential for damage during collection introduces the possibility of error. In response to these challenges, DNA barcoding has emerged as a promising alternative that may mitigate the problems associated with morphological identification (Beebe 2018). This enables us to identify mosquitoes to species and subspecies levels, understand genetic diversity and make predictions on evolution and phylogenetic relationships.

Herbert and colleagues (Hebert et al. 2003) first applied the DNA barcoding approach in 2003 and it has since proven its utility in the identification of various animal species, including mosquitoes (Beebe 2018). DNA barcoding involves the genetic identification of mosquitoes through specific gene sequences that exhibit inter‐species variability while remaining conserved within species (Hebert and Gregory 2005). The most widely adopted barcode region for animals is the 648 bp Cytochrome Oxidase I (COI) gene fragment amplified using the primer pair LCO1490 and HCO2198, often referred to as ‘universal barcode’ (Folmer et al. 1994). Other regions within the COI gene have been assessed as alternative barcodes (Endersby et al. 2013; Lunt et al. 1996). The mitochondrial COI gene is ideal for its high copy number and substantial inter‐species sequence variation (Beebe 2018). Additionally, various other genetic markers, such as internal transcribed spacer subunit 2 (ITS2), acetylcholinesterase 2 (ace‐2), elongation factor‐1 alpha, alpha amylase, NADH dehydrogenase and zinc finger, have been employed in mosquito barcoding studies (Endersby et al. 2013; Foley et al. 2007; Hasan et al. 2009; Hemmerter, Slapeta, and Beebe 2009; Puslednik, Russell, and Ballard 2012). Combining two or more of these barcodes has proven effective in distinguishing members of species complexes and subgroups, which is often challenging when using a single barcode region (Bourke et al. 2013; Foster et al. 2013). Consequently, DNA barcoding has allowed identification of less familiar species that were prone to misidentification.

In Australia, over 300 mosquito species are known to be extant and about 100 species are found in Western Australia (WA). WA, the country's largest state, covers roughly one‐third of the entire landmass. The majority of the WA population is concentrated in the southwest, while the remainder of the state remains sparsely populated. Southwest WA is deemed a high‐risk region for Ross River virus (RRV) and Barmah Forest virus (BFV) disease outbreaks, whereas mosquitoes in the northern regions of WA transmit RRV, BFV, Murray Valley Encephalitis virus (MVEV) and West Nile virus Kunjin subtype (WNVKUN). Within the framework of arbovirus surveillance programs, mosquitoes are routinely collected from the southwest and from northern WA specifically in the Pilbara and Kimberley regions (Cheryl Johansen et al. 2014). Currently, these mosquito specimens are identified using morphological methods and dichotomous keys. Barcoding data of WA mosquitoes is limited to only a handful of species. The COI barcode data of only six WA mosquito species are available in the Barcode of Life Database (BOLD), a cloud‐based platform for storage and curation of DNA barcodes (accessed 11/01/2024) (Ratnasingham and Hebert 2007).

This study aimed to assess the utility of DNA barcoding in identifying mosquitoes and to generate a DNA barcode library for the common mosquito species found in WA. We applied DNA barcoding to specimens from 45 species belonging to nine genera of mosquitoes collected in the southwestern and Kimberley regions of WA, each characterised by distinct climatic conditions—a temperate climate in the southwest and a tropical monsoon climate in the Kimberley. Our primary objective is to significantly expand the COI barcode database of Australian mosquito species by creating a comprehensive barcode library of mosquito species from WA. This resource will significantly enhance WA mosquito surveillance programs.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Mosquito Collection and Morphological Identification

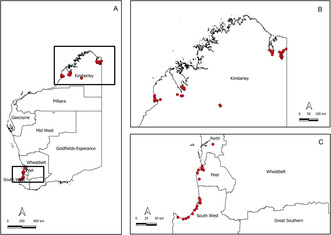

Adult mosquitoes were collected by the Medical Entomology team of the Department of Health, WA between 2018 and 2020 as a part of the routine arbovirus surveillance program. The samples were collected from 77 different locations (Figure 1) encompassing 13 sites within the Shire of Broome, 14 in the Shire of Derby‐West Kimberley, 28 within the Shire of Wyndham East Kimberley, 21 across Peel and South West WA and 1 from the Perth metropolitan area. Mosquitoes were collected using EVS CO2 traps (Rohe and Fall 1979) baited with dry ice and set at each location for approximately 12 h. The captured mosquitoes were euthanized immediately upon trap collection by placing them on dry ice, transferred to labelled vials and transported to the Department of Health Medical Entomology laboratory in Perth. Upon arrival, samples were stored at −80°C until further processing.

FIGURE 1.

Western Australian mosquito sample locations. Mosquitoes were sampled from geographically distinct regions in Western Australia (A, boxed), including the Kimberley region (B) and sites within Perth Metropolitan, Peel and South West regions (C). Within each region, samples were collected from multiple traps sites (red dots). Maps created with QGIS 3.14.

Morphological identification of the mosquitoes was performed on refrigerated tables under stereoscopic microscopes. The species were designated based on published taxonomic keys and descriptions (Lee et al. 1984; Liehne 1991; Russell and Debenham 1996). A total of 177 mosquito specimens, representing nine genera and 45 distinct species, were included in this study (Table S1).

2.2. DNA Extraction, Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) and Sequencing

Total genomic DNA was extracted from one to six legs of the individual mosquitoes using Qiagen DNeasy kit (Qiagen) following manufacturer's instructions. The standard 658 bp Cytochorme c oxidase subunit I (cox I) gene was amplified using the universal primer pair LCO1490 (5′‐GGT CAA CAA ATC ATA AAG ATA TTG G‐3′) and HCO2198 (TAA ACT TCA GGG TGA CCA AAA AAT CA‐3′) (Folmer et al. 1994). Each amplification was performed in 25 μL reaction which included 3ul DNA template 12.5 μL Taq 2X Mastermix (NEB), 0.5 μL of forward and reverse primers (10 μM) and 8.5 μL of H2O. PCR parameters were 95°C for 5 min and 35 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 48°C for 45 s and 68°C for 1 min followed by a final extension step of 68°C for 5 min. PCR products were run in 2% agarose gel stained with gel red (Fisher biotech) and visualised in Alliance Q9 imager (Uvitec).

PCR products showing positive clear bands were purified using ExoSAP‐IT (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Following the clean‐up of the PCR product, the ABI Big Dye Terminator v3.1 system was used for the sequencing reaction. Capillary electrophoresis was performed on the samples using 16‐capillary genetic analyser (ABI 3130 genetic analyser, Thermo Fisher Scientific). All sequences were uploaded to the Barcode of Life Data Systems (BOLD) and can be found under the project ‘Western Australian Mosquitoes’.

2.3. DNA Sequence Analysis

The bi‐directional trace files of the sequences were trimmed for low quality bases and edited using the Geneious Prime 2020.1.2 (https://www.geneious.com). The forward and reverse sequences were assembled using de novo assembly function in Geneious Prime. The sequences were aligned using MAFFT version 7.450 (Katoh et al. 2002; Katoh and Standley 2013) embedded in Geneious Prime. The consensus sequences along with metadata, were uploaded to the BOLD. The Refined Single Linkage (RESL) algorithm within BOLD was used to assign Barcode Index Numbers (BINs) to the COI dataset (Ratnasingham and Hebert 2013). The RESL algorithm uses a two‐step procedure: an initial clustering at a 2.2% divergence threshold followed by a refinement step using Markov clustering. It also allows a direct comparison of the COI dataset with all sequences present in the BOLD database.

The maximum likelihood (ML) phylogenetic analyses were performed based on the general time‐reversible model with GTR+G+I model using MEGA X software (Kumar et al. 2018) with bootstrapping for 1000 replicates to assess nodal support. All phylogenetic trees were visualised and edited using FigTree v1.4.4 (https://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/Figtree/). To estimate intra‐ and interspecific genetic distances, Kimura 2 Parameter (K2P) (Kimura 1980) within MEGA X was used. The number of haplotypes, haplotype diversity, parsimony informative sites, variable sites and GC conten were estimated using DNA sequence polymorphism software (DnaSP, version 6) (Rozas et al. 2017). The presence and absence of the ‘barcode gap’ were evaluated using BOLD's barcode gap analysis function. For species delimitation, the assemble species by automatic partitioning (ASAP) method based on K2P distance and BIN‐RESL algorithm method were used.

3. Results

3.1. Morphological Identification

Of the 177 specimens, 91 were collected from the Kimberley region situated in the far north of WA while 86 were collected from Southern WA (Perth, Peel and South West regions). Information about the exact location of each specimen is presented in Table S1. The name of the species was verified using the Mosquito Taxonomic Inventory (Harbach 2023). The tribe Aedini, which includes approximately one quarter of known mosquito species and contains the genus Aedes, has undergone several taxonomic revisions however these classifications are not commonly used in Australia. To avoid confusion and for comparison with previous literature, both traditional and revised names according to the most recent revision (Reinert, Harbach, and Kitching 2009) are presented in Table 1. A total of 45 species from 9 genera were identified: Aedeomyia (1 species), Aedes (18 species), Anopheles (6 species), Coquillettidia (2 species), Culex (13 species), Culiseta (1 species), Mansonia (1 species), Tripteroides (2 species), and Uranotaenia (1 species).

TABLE 1.

Species names of mosquitoes of the tribe Aedini used in this study and the new names according to recent revisions.

| Species names used in this study | Name according to recent revisions |

|---|---|

| Aedes notoscriptus (Skuse, 1889) | Rampamyia notoscripta |

| Aedes vigilax (Skuse, 1889) | Ochlerotatus vigilax |

| Aedes alboannulatus (Macquart, 1850) | Dobrotworskyius alboannulatus |

| Aedes camptorhynchus (Thomson, 1869) | Ochlerotatus camptorhynchus |

| Aedes ratcliffei (Marks, 1959) | Ochlerotatus ratcliffei |

| Aedes clelandi (Taylor, 1914) | Ochlerotatus clelandi |

| Aedes hesperonotius (Marks, 1959) | Ochlerotatus hesperonotius |

| Aedes nigrithorax (Macquart, 1847) | Ochlerotatus nigrithorax |

| Aedes turneri (Marks, 1963) | Ochlerotatus turneri |

| Aedes stricklandi (Edwards, 1912) | Ochlerotatus stricklandi |

| Aedes elchoensis (Taylor, 1929) | Macleaya elchoensis |

| Aedes tremulus (Theobald, 1903) | Macleaya tremula |

| Aedes daliensis (Taylor, 1916) | Ochlerotatus daliensis |

| Aedes normanensis (Taylor, 1915) | Ochlerotatus normanensis |

| Aedes lineatopennis (Ludlow, 1905) | Neomelaniconion lineatopenne |

| Aedes mallochi (Taylor, 1944) | Ochlerotatus mallochi |

| Aedes pecuniosus (Edwards, 1922) | Molpemyia pecuniosa |

| Aedes alternans (Westwood, 1835) | Mucidus alternans |

| Aedes albopictus (Skuse, 1895) | Stegomyia albopicta |

3.2. Analyses of COI Barcodes

The COI sequences of the mosquito specimens in this study were adenosine and thymine‐rich (AT‐rich), with an average nucleotide composition of adenine (A) = 29.2%, thymine (T) = 39.4%, guanine (G) = 15.3% and cytosine (C) = 16.1%. DNA polymorphism analyses of the 177 COI sequences showed 359 monomorphic invariable sites and 278 polymorphic variable sites with 244 parsimony informative and 34 singleton variable sites. Haplotype analysis revealed 134 haplotypes. The nucleotide alignments of each species were also used to calculate haplotype number of haplotypes and haplotype diversity and the results are presented in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

List of mosquito species barcoded in this study, locations, BOLD Process IDs, number of haplotypes, polymorphic sites and haplotype diversity.

| Species | Region | Town/City | BOLD Process IDs | n | h | Polymorphic sites | Haplotype diversity (±SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aedeomyia catasticta | Kimberley | Wyndham | WAMOS056‐21 to WAMOS058‐21 | 3 | 3 | 6 | 1 ± 0.3 |

| Aedes alboannulatus | South West | Mandurah | WAMOS102‐21 to WAMOS103‐21 | 2 | 4 | 13 | 0.9 ± 0.2 |

| Quindalup | WAMOS104‐21 | 1 | |||||

| Mandurah | WAMOS105‐21 to WAMOS106‐21 | 2 | |||||

| Ae. alternans | Kimberley | Derby | WAMOS165‐21 to WAMOS166‐21 | 2 | 3 | 14 | 1 ± 0.3 |

| Wyndham | WAMOS167‐21 | 1 | |||||

| Ae. Camptorhynchus | South West | Mandurah | WAMOS107‐21 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 0.4 ± 0.1 |

| WAMOS114‐21 to WAMOS118‐21 | 5 | ||||||

| Australind | WAMOS108‐21 | 1 | |||||

| Eaton | WAMOS109‐21 to WAMOS110‐21 | 2 | |||||

| Capel | WAMOS111‐21 | 1 | |||||

| Stratham | WAMOS112‐21 | 1 | |||||

| Abbey | WAMOS113‐21 | 1 | |||||

| Ae. clelandi | South West | Eaton | WAMOS122‐21 | 1 | 6 | 13 | 0.9 ± 0.1 |

| Mandurah | WAMOS123‐21 | 1 | |||||

| WAMOS126‐21 to WAMOS128‐21 | 3 | ||||||

| Busselton | WAMOS124‐21 | 1 | |||||

| Quindalup | WAMOS125‐21 | 1 | |||||

| Ae. daliensis | Kimberley | Derby | WAMOS144‐21 to WAMOS145‐21 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 ± 0.5 |

| Ae. elchoensis | Kimberley | Wyndham | WAMOS140‐21 | 1 | 1 | NC | NC |

| Ae. hesperonotius | Southwest | Busselton | WAMOS129‐21 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 1 ± 0.5 |

| Mandurah | WAMOS130‐21 | 1 | |||||

| Ae. lineatopennis | Kimberley | Derby | WAMOS149‐21 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 0.7 ± 0.2 |

| Wyndham | WAMOS150‐21 to WAMOS153‐21 | 4 | |||||

| Ae. mallochi | South West | Stratham | WAMOS154‐21 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 ± 0.5 |

| Capel | WAMOS155‐21 | 1 | |||||

| Ae. nigrithorax | South West | Bunbury | WAMOS131‐21 to WAMOS132‐21 | 2 | 4 | 12 | 1 ± 0.2 |

| Mandurah | WAMOS133‐21 to WAMOS134‐21 | 2 | |||||

| Ae. normanensis | Kimberley | Derby | WAMOS146‐21 to WAMOS148‐21 | 3 | 2 | 8 | 0.7 ± 0.3 |

| Ae. notoscriptus | Kimberley | Broome | WAMOS083‐21 to WAMOS085‐21 | 3 | 4 | 21 | 0.8 ± 0.2 |

| Wyndham | WAMOS088‐21 | 1 | |||||

| South West | Eaton | WAMOS086‐21 | 1 | ||||

| Quindalup | WAMOS087‐21 | 1 | |||||

| Ae. pecuniosus | Kimberley | Derby | WAMOS156‐21 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 1 ± 0.3 |

| Wyndham | WAMOS157‐21 to WAMOS158‐21 | 2 | |||||

| Ae. ratcliffei | South West | Eaton | WAMOS119‐21 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 0.7 ± 0.3 |

| Busselton | WAMOS120‐21 | 1 | |||||

| Australind | WAMOS121‐21 | 1 | |||||

| Ae. stricklandi | South West | Australind | WAMOS139‐21 | 1 | 1 | NC | NC |

| Ae. tremulus | Kimberley | Broome | WAMOS141‐21 to WAMOS142‐21 | 2 | 3 | 17 | 1 ± 0.3 |

| Derby | WAMOS143‐21 | 1 | |||||

| Ae. turneri | South West | Eaton | WAMOS135‐21 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 0.8 ± 0.2 |

| Busselton | WAMOS136‐21 | 1 | |||||

| Abbey | WAMOS137‐21 | 1 | |||||

| Mandurah | WAMOS138‐21 | 1 | |||||

| Ae. vigilax | Kimberley | Broome | WAMOS089‐21 to WAMOS090‐21 | 2 | 8 | 13 | 0.8 ± 0.1 |

| Derby | WAMOS091‐21 to WAMOS092‐21 | 2 | |||||

| Wyndham | WAMOS100‐21 to WAMOS101‐21 | 2 | |||||

| South West | Mandurah | WAMOS093‐21 | 1 | ||||

| WAMOS096‐21 to WAMOS099‐21 | 4 | ||||||

| Australind | WAMOS094‐21 | 1 | |||||

| Quindalup | WAMOS095‐21 | 1 | |||||

| Anopheles amictus | Kimberley | Derby | WAMOS059‐21 to WAMOS060‐21 | 2 | 3 | 8 | 1 ± 0.3 |

| Wyndham | WAMOS061‐21 | 1 | |||||

| An. annulipes sensu lato | Kimberley | Derby | WAMOS066‐21 to WAMOS067‐21 | 2 | 7 | 69 | 0.9 ± 0.1 |

| Wyndham | WAMOS075‐21 | 1 | |||||

| South West | Australind | WAMOS068‐21 | 1 | ||||

| WAMOS074‐21 | 1 | ||||||

| Eaton | WAMOS069‐21 | 1 | |||||

| Quindalup | WAMOS070‐21 | 1 | |||||

| Mandurah | WAMOS071‐21 to WAMOS073‐21 | 3 | |||||

| An. atratipes | South West | Eaton | WAMOS078‐21 to WAMOS079‐21 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 ± 0.5 |

| An. bancroftii | Kimberley | Wyndham | WAMOS080‐21 to WAMOS082‐21 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 1 ± 0.3 |

| An. Hilli | Kimberley | Wyndham | WAMOS062‐21 to WAMOS065‐21 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 1 ± 0.2 |

| An. meraukensis | Kimberley | Wyndham | WAMOS076‐21 to WAMOS077‐21 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 ± 0.5 |

| Coquillettidia species near linealis | South West | Australind | WAMOS168‐21 to WAMOS169‐21 | 2 | 3 | 6 | 1 ± 0.3 |

| Mandurah | WAMOS170‐21 | 1 | |||||

| Cq. xanthogaster | Kimberley | Wyndham | WAMOS171‐21 to WAMOS173‐21 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 1 ± 0.3 |

| Culex palpalis | Kimberley | Wyndham | WAMOS020‐21 to WAMOS023‐21 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 1 ± 0.2 |

| Cx. annulirostris | Kimberley | Broome | WAMOS001‐21 to WAMOS008‐21 | 8 | 16 | 33 | 1 ± 0.0 |

| Derby | WAMOS009‐21 to WAMOS010‐21 | 2 | |||||

| Wyndham | WAMOS018‐21 to WAMOS019‐21 | 2 | |||||

| South West | Mandurah | WAMOS011‐21 | 1 | ||||

| WAMOS015‐21 to WAMOS017‐21 | 3 | ||||||

| Australind | WAMOS012‐21 | 1 | |||||

| Eaton | WAMOS013‐21 | 1 | |||||

| Quindalup | WAMOS014‐21 | 1 | |||||

| Cx. australicus | South West | Mandurah | WAMOS033‐21 to WAMOS034‐21 | 2 | 3 | 7 | 1 ± 0.3 |

| Australind | WAMOS035‐21 | 1 | |||||

| Cx. Bitaeniorhynchus | Kimberley | Wyndham | WAMOS040‐21 to WAMOS042‐21 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0.7 ± 0.3 |

| Cx. gelidus | Kimberley | Wyndham | WAMOS049‐21 to WAMOS050‐21 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 |

| Cx. globlocoxitus | South West | Mandurah | WAMOS028‐21 | 1 | 4 | 9 | 0.9 ± 0.2 |

| WAMOS031‐21 | 1 | ||||||

| Australind | WAMOS029‐21 | 1 | |||||

| WAMOS032‐21 | 1 | ||||||

| Eaton | WAMOS030‐21 | 1 | |||||

| Cx. Hilli | Kimberley | Wyndham | WAMOS051‐21 | 1 | 1 | NC | NC |

| Cx. Latus | South West | Busselton | WAMOS052‐21 | 1 | 1 | NC | NC |

| Cx. pipiens biotype molestus | Perth | Lesmurdie | WAMOS026‐21 to WAMOS027‐21 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 |

| Cx. pullus | Kimberley | Derby | WAMOS044‐21 to WAMOS045‐21 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0.4 ± 0.2 |

| Wyndham | WAMOS046‐21 to WAMOS048‐21 | 3 | |||||

| Cx. Quinquefasciatus | South West | Quindalup | WAMOS036‐21 | 1 | 4 | 7 | 1 ± 0.2 |

| Mandurah | WAMOS037‐21 | 1 | |||||

| Wonnerup | WAMOS038‐21 | 1 | |||||

| Eaton | WAMOS039‐21 | 1 | |||||

| Cx. sitiens | Kimberley | Broome | WAMOS024‐21 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 ± 0.5 |

| Wyndham | WAMOS025‐21 | 1 | |||||

| Cx. starckeae | Kimberley | Wyndham | WAMOS043‐21 | 1 | 1 | NC | NC |

| Culiseta atra | South West | Eaton | WAMOS053‐21 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 ± 0.5 |

| WAMOS054‐21 | 1 | ||||||

| Mansonia uniformis | Kimberley | Wyndham | WAMOS174‐21 to WAMOS177‐21 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 0.8 ± 0.2 |

| Tripteroides atripes | South West | Mandurah | WAMOS163‐21 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 ± 0.5 |

| Bunbury | WAMOS164‐21 | 1 | |||||

| Tp. punctolateralis | Kimberley | Broome | WAMOS159‐21 to WAMOS161‐21 | 3 | 2 | 10 | 0.5 ± 0.3 |

| Derby | WAMOS162‐21 | 1 | |||||

| Uranotaenia albescens | Kimberley | Wyndham | WAMOS055‐21 | 1 | 1 | NC | NC |

Abbreviations: h = number of haplotypes, N = number of COI sequences, NC = not calculated (i.e., represented by only one specimen), SD = standard deviation.

3.3. BOLD BIN Analysis

The RESL clustering approach applied to the COI marker assigned 47 BINs for 45 species sequenced in this study (Table 3). BIN analysis revealed that 28 species perfectly clustered into respective single BIN. Six species were split into multiple BINs, which include: Ae. nigrithorax (BOLD: AAE2446 and ACS6163), Ae. normanensis (BOLD: AEI6697 and AAV4152), Ae. notoscriptus (BOLD: AAG3835, ADM7085 and ADM7086), Ae. tremulus (BOLD: AEI4268 and AAZ2708), An. annulipes s.l (BOLD: AAB2268, AAF0630, ABZ0076 and ACE2888) and Cx. annulirostris (BOLD: AAG3833 and AEG7306).

TABLE 3.

Barcode Index Number (BIN) results and minimum interspecific distance based on barcode gap analysis in the BOLD database.

| Species | Barcode Index Number (BIN) results | Nearest species | Distance to the nearest neighbour | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BIN ID | Total members | Count in project | |||

| Ad. catasticta | ACV8061 | 6 | 3 | Ur. albescens | 11.47 |

| Ae. alboannulatus | ABX6893 | 15 | 5 | Ae. camptorhynchus | 7.51 |

| Ae. alternans | AAG3831 | 18 | 3 | Ae. nigrithorax | 11.85 |

| Ae. camptorhynchus | ACB5426 | 110 | 12 | Ae. ratcliffei | 5.71 |

| Ae. clelandi | AEI2751 | 9 | 7 | Ae. hesperonotius | 0.46 |

| Ae. daliensis | AEI7628 | 2 | 2 | Ae. Clelandi | 10.07 |

| Ae. elchoensis | AEI5460 | 1 | 1 | Ae. Turneri | 9.55 |

| Ae. hesperonotius | AEI2751 | 9 | 2 | Ae. clelandi | 0.46 |

| Ae. lineatopennis | ADJ4564 | 6 | 5 | Ae. nigrithorax | 10.25 |

| Ae. mallochi | ACS5624 | 11 | 2 | Ae. camptorhynchus | 9.72 |

| Ae. nigrithorax | AAE2446 | 21 | 3 | Ae. clelandi | 6.18 |

| ACS6163 | 7 | 1 | |||

| Ae. normanensis | AEI6697 | 2 | 2 | Ae. nigrithorax | 10.44 |

| AAV4152 | 3 | 1 | |||

| Ae. notoscriptus | AAG3835 | 12 | 4 | Ae. nigrithorax | 9.55 |

| ADM7085 | 32 | 1 | |||

| ADM7086 | 8 | 1 | |||

| Ae. pecuniosus | AEI5196 | 3 | 3 | Ae. camptorhynchus | 10.95 |

| Ae. ratcliffei | AEI8195 | 3 | 3 | Ae. camptorhynchus | 5.71 |

| Ae. stricklandi | AEI1635 | 5 | 1 | Ae. turneri | 2.01 |

| Ae. tremulus | AEI4268 | 2 | 2 | Ae. nigrithorax | 10.07 |

| AAZ2708 | 4 | 1 | |||

| Ae. turneri | AEI1635 | 5 | 4 | Ae. stricklandi | 2.01 |

| Ae. vigilax | AAC1707 | 250 | 13 | Ae. nigrithorax | 8.86 |

| An. amictus | AAF0754 | 7 | 3 | An. Hilli | 5.23 |

| An. annulipes s.l | AAB2268 | 41 | 7 | An. meraukensis | 9.31 |

| AAF0630 | 5 | 1 | |||

| ABZ0076 | 10 | 1 | |||

| ACE2888 | 20 | 1 | |||

| An. Atratipes | AEI9151 | 2 | 2 | An. meraukensis | 10.94 |

| An. Bancroftii | ADZ1695 | 10 | 3 | An. meraukensis | 9.84 |

| An. Hilli | AAD3119 | 11 | 4 | An. amictus | 5.23 |

| An. meraukensis | AAE5341 | 6 | 2 | An. annulipes | 9.31 |

| Cq. sp. near linealis | AEI9641 | 3 | 3 | Co. xanthogaster | 13.14 |

| Cq. xanthogaster | AAF1119 | 108 | 3 | Ur. albescens | 13.14 |

| Cx. annulirostris | AAG3833 | 232 | 16 | Cx. sitiens | 0.15 |

| AEG7306 | 43 | 3 | |||

| Cx. australicus | AEW0336 | 248 | 3 | Cx. quinquefasciatus | 0 |

| Cx. bitaeniorhynchus | AAJ7281 | 108 | 3 | Cx. starckeae | 6.18 |

| Cx. gelidus | AAC6669 | 163 | 2 | Cx. australicus | 7.85 |

| Cx. globocoxitus | AEW0336 | 248 | 5 | Cx. quinquefasciatus | 0 |

| Cx. hilli | AEI7284 | 1 | 1 | Cx. bitaeniorhynchus | 8.01 |

| Cx. latus | ACV5066 | 2 | 1 | Cx. pipiens | 9.74 |

| Cx. palpalis | AAG3833 | 232 | 4 | Cx. sitiens | 0 |

| Cx. pipiens | AAA4751 | 5980 | 2 | Cx. australicus | 2.96 |

| Cx. pullus | ACW1597 | 9 | 5 | Cx. australicus | 6.85 |

| Cx. quinquefasciatus | AEW0336 | 248 | 4 | Cx. globocoxitus | 0 |

| Cx. sitiens | AAG3833 | 232 | 2 | Cx. palpalis | 0 |

| Cx. starckeae | AEI0300 | 1 | 1 | Cx. bitaeniorhynchus | 6.18 |

| Cs. Atra | ACV7089 | 40 | 2 | Cx. Latus | 11.69 |

| Ma. uniformis | AAB7892 | 25 | 4 | Ae. nigrithorax | 13.81 |

| Tp. atripes | ACS4308 | 9 | 2 | Tr. punctolateralis | 0.77 |

| Tp. punctolateralis | ACS4308 | 9 | 4 | Tr. atripes | 0.77 |

| Ur. albescens | AAG3844 | 40 | 1 | Cx. gelidus | 10.42 |

Some of the species shared the same BIN. All the members within Cx. australicus, Cx. globocoxitus and Cx. quinquefasciatus shared BIN BOLD: AEW0336. Likewise, 16 members from Cx. annulirostris and all of Cx. palpalis and Cx. sitiens shared the same BIN BOLD: AAG3833. The other three members of Cx. annulirostris were under the BIN BOLD: AEG7306. Also, the species pairs including Ae. clelandi and Ae. hesperonotius (BOLD: AEI2571), Ae. stricklandi and Ae. turneri (BOLD: AEI1635) and Tripteroides atripes and Tp. punctolateralis (BOLD: ACS4308) shared the same BINs. A total of 12 unique BINs were identified.

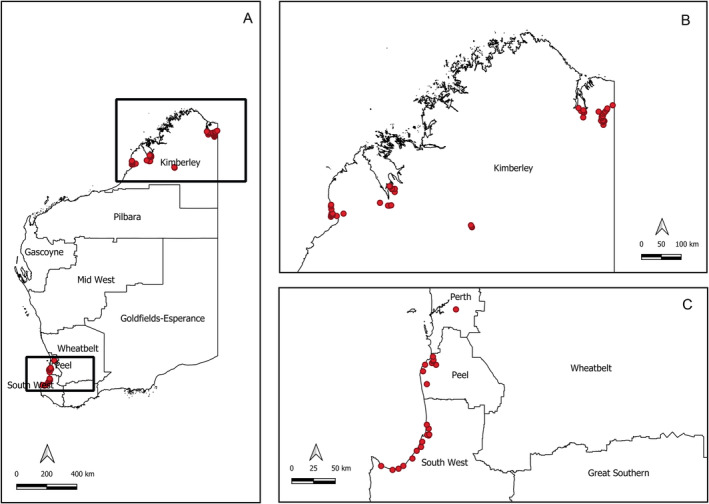

3.4. Intraspecific and Interspecific Sequence Divergence

The average intraspecific K2P distance of the 45 mosquito species was 1% (range 0%–9.1%). The maximum observed intraspecific divergence was 9.1% for An. annulipes s.l followed by 3.12 for Cx. annulirostris (Table 4). The average minimum interspecific genetic variation inferred by the distance to the nearest neighbour of the 45 mosquito species was 6.8% ranging from 0% to 13.8% (Table 3). The lowest minimum interspecific divergence of 0% was observed in the members of Cx. pipiens complex (Cx. australicus, Cx. globocoxitus and Cx. quinquefasciatus) and Cx. sitiens subgroup (Cx. annulirostris, Cx. sitiens, Cx. palpalis) followed by the species pairs Ae. clelandi and Ae. hesperonotius at 0.46% to each other. Another species pairs with low minimum interspecific divergence were Tp. atripes and Tp. punctolateralis (0.77%). These differences collectively account for all the overlap between intraspecific and interspecific differences seen in Figure 2. The highest minimum interspecific divergence was found in Ma. uniformis (closest to Ae. nigrithorax, 13.8%).

TABLE 4.

The maximum observed intraspecific Kimura two‐parameter (K2P) distances among the COI sequences.

| Species | Number of specimens | Average K2P distance (%) | Maximum observed K2P difference between intraspecific specimens (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aedeomyia catasticta | 3 | 0.61 | 0.77 |

| Aedes alboannulatus | 5 | 0.92 | 1.70 |

| Aedes alternans | 3 | 1.44 | 1.70 |

| Aedes lineatopennis | 5 | 0.12 | 0.30 |

| Aedes notoscriptus | 6 | 1.24 | 2.33 |

| Aedes pecuniosus | 3 | 0.20 | 0.30 |

| Aedes tremulus | 3 | 1.75 | 2.48 |

| Aedes camptorhynchus | 12 | 0.19 | 0.46 |

| Aedes clelandi | 7 | 0.66 | 1.39 |

| Aedes daliensis | 2 | 0.15 | 0.15 |

| Aedes hesperonotius | 2 | 0.77 | 0.77 |

| Aedes mallochi | 2 | 0.15 | 0.15 |

| Aedes nigrithorax | 4 | 0.95 | 1.85 |

| Aedes normanensis | 3 | 0.82 | 1.23 |

| Aedes ratcliffei | 3 | 0.30 | 0.46 |

| Aedes turneri | 4 | 0.38 | 0.77 |

| Aedes vigilax | 13 | 0.49 | 1.39 |

| Anopheles amictus | 3 | 0.82 | 1.23 |

| Anopheles annulipes sensu lato | 10 | 4.00 | 9.08 |

| Anopheles atratipes | 2 | 0.15 | 0.15 |

| Anopheles bancroftii | 3 | 0.31 | 0.46 |

| Anopheles hilli | 4 | 0.31 | 0.46 |

| Anopheles meraukensis | 2 | 0.16 | 0.16 |

| Coquillettidia species near linealis | 3 | 0.61 | 0.61 |

| Coquillettidia xanthogaster | 3 | 0.41 | 0.61 |

| Culex annulirostris | 19 | 1.07 | 3.12 |

| Culex australicus | 3 | 0.72 | 0.92 |

| Culex bitaeniorhynchus | 3 | 0.10 | 0.15 |

| Culex gelidus | 2 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Culex globlocoxitus | 5 | 0.61 | 1.38 |

| Culex pipiens biotype molestus | 2 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Culex palpalis | 4 | 0.36 | 0.61 |

| Culex pullus | 5 | 0.06 | 0.15 |

| Culex quinquefasciatus | 4 | 0.53 | 0.92 |

| Culex sitiens | 2 | 0.30 | 0.30 |

| Culiseta atra | 2 | 0.16 | 0.16 |

| Mansonia uniformis | 4 | 0.15 | 0.30 |

| Tripteroides atripes | 2 | 0.15 | 0.15 |

| Tripteroides punctolateralis | 4 | 0.77 | 1.54 |

FIGURE 2.

Intra and interspecies Kimura‐2 Parameter (K2P) genetic distances of COI sequences from WA mosquito species. Centre lines show medians; whiskers extend to the minimum and maximum values. Singleton species are excluded from the analysis.

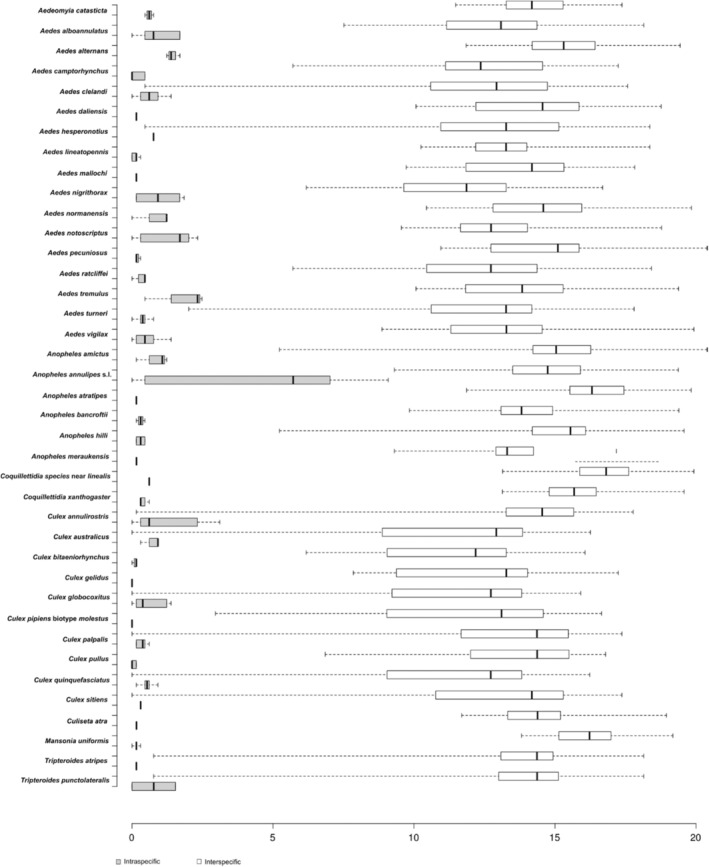

3.5. Phylogenetic Analysis and Species Delimitation

The maximum likelihood phylogenetic analysis revealed that most of the species demonstrated well‐supported clades (Figure 3). Three members of a Cx. pipiens subgroup, namely, Cx. australicus, Cx. globocoxitus and Cx. quinquefasciatus were clustered together. Similarly, Cx. annulirostris, Cx. sitiens and Cx. palpalis also formed a single clade with no separation between these species. They are part of a Cx. sitiens subgroup. A similar pattern was observed with species pairs Tp. atripes and Tp. punctolateralis and Ae. clelandi and Ae. hesperonotius. This clustering of these species' subgroups was, to a large extent, supported by the ASAP based on Kimura 2 parameter (K2P) distance and BIN‐RESL algorithm implemented in BOLD except that three Cx. annulirostris members were assigned a separate BIN (Table 3).

FIGURE 3.

Maximum likelihood (ML) tree based on 177 cytochrome c oxidase subunit I (COI) sequences representing 45 mosquito species. Bootstrap support values are shown near each branch. Species are coloured blue if they share single BIN with other species or split into multiple BINs. Vertical bars indicate species delimited using BIN‐refined single linkage analysis (RESL) algorithm (black bar) and assemble species by automatic partitioning (ASAP) algorithm (green bar).

Both BOLD and ASAP failed to separate the Ae. turneri and Ae. stricklandi suggesting they are members of the same species subgroup. In contrast to the BIN‐RESL algorithm, ASAP worked well with Ae. normanensis, Ae. nigrithorax, Ae. notoscriptus, Cx. annulirostris, where members of respective species were kept together. ASAP method, however, failed to separate An. hilli and An. amictus, which BOLD assigned separate BINs. An. annulipes was split into four BINs by BOLD, while it was divided into two groups by ASAP.

4. Discussion

Accurate identification of mosquito species is crucial in selecting the optimal vector control approach for the target mosquito species (Sumruayphol et al. 2020) to successfully reduce mosquito populations. However, traditional morphological approaches to mosquito identification take years to develop the experience and knowledge for accurate identification of mosquito species and is a skill developed by few researchers across Australia. Mosquito identification is routinely performed by less experienced Local Government Environmental Health Officers taking considerable time and effort to correctly identify the mosquito fauna within their jurisdiction. Accurate identification is required to ensure targeted mosquito control options are deployed, considering the likely breeding sites and life history traits of the individual species identified that may be causing a nuisance or disease risk. The COI barcode of 177 mosquitoes, classified into 45 species and nine genera from the present study, provides support for DNA barcoding as a genetic approach for identifying mosquito species in WA. Furthermore, the addition of barcode data of 16 previously unbarcoded species (Table S2) has not only broadened the international reference library but also contributed to the Mosquito Barcoding Initiative (Linton 2009), further advancing the field of mosquito species identification and classification. As DNA barcoding libraries are further developed, efficiencies in mosquito identification through these techniques will provide more accurate assessments of mosquito populations and targeted approaches for their control.

The average AT‐richness of 68.6% in the DNA barcode sequences generated in the present study is consistent with similar studies describing AT‐richness in mosquito COI sequences (Wang et al. 2012; Chaiphongpachara et al. 2022). The majority of the barcoded species in this study formed distinct clusters in the phylogenetic analysis, thus confirming the utility of DNA barcoding.

This study reported ambiguous identification within the Cx. sitiens subgroup members (Lee, Bryan, and Russell 1989), namely, Cx. annulirostris, Cx. sitiens and Cx. palpalis, as their barcodes were all identified as Cx. annulirostris. These three members of Cx. sitiens subgroup are of significant interest in the Australasian region, owing to their wide geographical distribution and role in arbovirus transmission (Jansen et al. 2013). The difficulty in separating these species both morphologically and using non‐morphological methods is a known issue (Lee, Bryan, and Russell 1989; Chapman et al. 2000). Beebe et al. successfully employed PCR‐Restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) in the ribosomal ITS1 sequences to discriminate between the three species (Beebe et al. 2002). Additionally, Hemmerter et al. reported COI identification of Cx. annulirostris and Cx. palpalis supporting the PCR‐RFLP method (Hemmerter, Slapeta, and Beebe 2009) but few samples from WA were included in that analysis. It is possible that in our present study we misidentified Cx. annulirostris as Cx. palpalis and/or Cx. sitiens. Nevertheless, a comprehensive investigation into the barcodes and morphological characteristics of the Culex sitiens subgroup members across a wide geographical range in Australia is warranted before drawing any definitive conclusions.

The Culex pipiens complex comprises four members in Australia: two indigenous, Cx. australicus and Cx. globocoxitus and two introduced, Cx. quinquefasciatus and Cx. pipiens biotype molestus (Russell 2012). The present study could not discriminate between the Cx. australicus, Cx. globocoxitus and Cx. quinquefasciatus while Cx. pipiens biotype molestus formed a separate cluster. The inability of the COI barcodes to distinguish the members of Cx. pipiens complex is known and the ACE‐2 marker has been used to differentiate between these species (Kasai et al. 2008; Laurito et al. 2013; Lee et al. 2012; Smith and Fonseca 2004). A similar Australian study from Victoria targeting COI barcodes reported very low divergence (0%–1%) between Cx. australicus and Cx. globocoxitus and no divergence between Cx. quinquefasciatus and Cx. pipiens biotype molestus (Batovska et al. 2016). It is now well established that the current COI barcoding method cannot discriminate between Cx. pipiens complex members; therefore, the use of other barcodes should be explored.

Other species groups with low genetic divergence found in this study were species pairs Ae. clelandi and Ae. hesperonotius; Tp. atripes and Tp. punctolateralis; and Ae. turneri and Ae. stricklandi. Among them Ae. clelandi, Ae. hesperonotius, Tp. punctolateralis, Ae. turneri and Ae. stricklandi were barcoded for the first time and are new additions to the BOLD and Genbank databases. It is to be noted that these species pairs are morphologically very similar (Liehne 1991; Webb and Russell 2016). Although COI identification of the former two species pairs could not be made, a phylogenetic tree assisted in discriminating between Ae. turneri and Ae. stricklandi in this study.

Species complexes and subgroups can confuse identification and create issues in the application of the ‘barcode gap’ (Candek and Kuntner 2015), the difference between intra‐ and interspecific genetic distances and is effective in species identification (Meier, Zhang, and Ali 2008; Sheraliev and Peng 2021). Several studies have shown the absence of a barcode gap in mosquitoes that are closely related or that belong to species complexes (Chaiphongpachara et al. 2022; Batovska et al. 2016; Meier, Zhang, and Ali 2008; Cywinska, Hunter, and Hebert 2006; Versteirt et al. 2015). Despite the lack of a barcode gap in some groups in this study, all other species clustered separately, thereby validating the diagnostic competence of DNA barcoding using COI. Additionally, phylogenetic analysis in concert with species delimitation methods can assist in correctly identifying species (Chaiphongpachara et al. 2022). Thus, phylogenetic analysis remains an essential aspect of DNA barcoding for species assessment.

Anopheles annulipes sensu lato, meaning An. annulipes in the broad sense, is a complex of genetically distinct but morphologically similar mosquitoes with at least 15 sibling species (Foley et al. 2007; Foley, Bryan, and Wilkerson 2007). A previous study by Foley et al. analysed the barcodes COI, COII, EF‐1α and ITS2 of An. annulipes s.l from across Australia found two major clades, one in northern Australia and one mainly in the south of the country (Foley et al. 2007). The COI analysis of 10 An. annulipes s.l species in the present study corroborated the earlier findings of Foley et al. Notably, we identified two well‐supported clades of An. annulipes s.l, with strong bootstrap support, one comprising three northern WA members and the other with seven members from southwest WA (Figure 3). Although ASAP analysis also split them into two groups, the BIN‐RESL algorithm further partitioned the three members from northern WA into three BINs, increasing the total number of BINs to four. Furthermore, the intraspecific divergence based on K2P distance was highest within An. annulipes s.l compared to other species. Therefore, this study reinforces the species richness of An. annulipes s.l and with further sampling, additional sibling species will likely be discovered.

Northern WA has a higher species diversity of Anopheles species compared to the south, with at least nine species extant (Liehne 1991). There was no publicly available COI data for An. atratipes, a single short (258 bp) sequence available for each of An. meraukensis, An. hilli and An. amictus and none for Australian An. bancroftii species (Genbank and BOLD, accessed 11/01/2023). Although the vector potential of most of the Anopheles species in WA remains largely unknown, An. bancroftii is the known vector of malaria and Wuchereria bancrofti in Papua New Guinea (PNG) (Beebe et al. 2001). The inclusion of COI sequences of Anopheles species from this study into the Genbank and BOLD databases will aid in investigating genetic variations of these mosquito vectors as more sequences are added in the future.

For species delimitation in this study's COI dataset, the ASAP method performed better than the BIN‐RESL method. In contrast to the BIN‐RESL approach, ASAP did not split Ae. normanensis, Ae. tremulus, Ae. nigrithorax, Ae. notoscriptus and failed to separate An. amictus and An. hilli. The ASAP method used in this study was based on the K2P substitution model that builds partitions from the barcode database using the threshold values to distinguish between intra‐ and interspecific divergence (Puillandre, Brouillet, and Achaz 2021). On the other hand, the BIN‐RESL algorithm is based on assigning Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs) and putative species from the BOLD database using RESL (Ratnasingham and Hebert 2013). Our findings indicate, in line with other studies, that more than one species delimitation method must be used when delineating species as each method possesses its own distinct advantages (Puillandre, Brouillet, and Achaz 2021). One limitation of our study is the limited number of representative samples for each species. A larger sample size would offer a more accurate depiction of haplotype diversity and intraspecific divergence.

The DNA barcodes for WA mosquitoes presented in this study will assist public health officials to strengthen arbovirus surveillance programs targeted at the identified mosquitoes' life history traits to enhance the success of mosquito control efforts. Furthermore, accurate identification can assist in determining the risk posed by mosquitoes (whether they are a vector of human or animal diseases) further enhancing public health response measures and potentially reducing the incidence of disease. By incorporating DNA barcoding as an additional identification tool, it becomes possible to overcome challenges associated with species identification, especially when dealing with morphologically similar subgroups and species complexes. DNA barcoding is useful when the mosquito species are physically damaged or if the larval stages cannot be distinguished from each other. As the DNA barcodes are further developed, greater efficiencies can be achieved in this approach for mosquito identification. DNA barcoding can be integrated with next‐generation sequencing (NGS) technology, allowing the simultaneous processing of thousands of samples in a cost‐effective single run (Ji et al. 2013). A similar barcode library has been created in Victoria, an Australian state located on the eastern coast of the country (Batovska et al. 2016), demonstrating its utility in identifying mosquitoes from bulk samples using NGS. (Batovska et al. 2018). Internationally, countries including Canada, India, China, Belgium, Thailand, Saudi Arabia, Mexico and Singapore have established COI barcode databases for mosquito species in their respective regions (Wang et al. 2012; Chaiphongpachara et al. 2022; Cywinska, Hunter, and Hebert 2006; Versteirt et al. 2015; Chan et al. 2014; Chan‐Chable et al. 2019; Kumar et al. 2007; Noureldin et al. 2022). Notably, these studies have also utilised the universal COI barcode, making the data generated in the present study compatible for comparative analyses.

5. Conclusions

We have successfully barcoded 45 species of Western Australian mosquitoes sampled across a wide spatial range, significantly expanding the barcode data for WA mosquitoes. Most species exhibited adequate genetic diversity in their barcodes, enabling reliable species identification. However, we also report low genetic divergence between certain species pairs, including Ae. clelandi and Ae. hesperonotius; Tp. atripes and Tp. punctolateralis; and Ae. turneri and Ae. stricklandi, indicating that COI alone may not be sufficient for species discrimination. Other barcode regions should be explored for reliable identification of these species. Most importantly, the barcodes generated in this study and accompanying analysis can serve as valuable resources for mosquito surveillance programs, aiding in species identification, enhancing understanding of evolutionary relationships and identifying patterns of associations among different mosquito species. We have submitted all COI nucleotide sequences from mosquitoes analysed in this study to BOLD and Genbank databases to allow an analysis of genetic variations related to the geographical distribution of these mosquito species.

Author Contributions

Binit Lamichhane: conceptualization (equal), data curation (equal), formal analysis (equal), investigation (equal), methodology (equal), writing – original draft (lead), writing – review and editing (equal). Craig Brockway: investigation (equal), resources (equal), writing – review and editing (equal). Kimberly Evasco: investigation (equal), resources (equal), writing – review and editing (equal). Jay Nicholson: investigation (equal), resources (equal), writing – review and editing (equal). Peter J. Neville: investigation (equal), resources (equal), writing – review and editing (equal). John S. Mackenzie: resources (equal), writing – review and editing (equal). David Smith: funding acquisition (equal), investigation (equal), project administration (equal), resources (equal), software (equal), writing – review and editing (equal). Allison Imrie: conceptualization (equal), funding acquisition (equal), project administration (equal), resources (equal), software (equal), supervision (lead), writing – review and editing (equal).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Supporting information

Table S1. Details of mosquito species used in this study.

Table S2. Barcode records and medical importance of mosquito species sequenced in this study.

Acknowledgements

We thank the staff at the Environmental Health Directorate of the Department of Health, Western Australia for the collection of mosquitoes and help with the morphological identification of the mosquitoes.

Funding: This work was supported by Western Australia Department of Health West Australian Mosquito‐borne Disease Scholarship. Sibyl Gibbons Wife of Wylie Postgraduate Scholarship. University of Western Australia Scholarship for International Research Fees and RTP Domestic Fees Offset.

Data Availability Statement

All barcode sequences used in this study are uploaded into the BOLD Database under the project Western Australia Mosquitoes (WAMOS) with BOLD accession numbers from WAMOS001‐21 to WAMOS177‐21. The sequences were also stored on NCBI GenBank under the accession numbers PP145112 to PP145288. The photographs of mosquito species described in this study can be found at the following web address: https://www.health.wa.gov.au/~/media/Corp/Documents/Health‐for/Mosquitoes/PDF/Species‐Sheets‐for‐Mosquitoes‐in‐WA‐updated.pdf

References

- Batovska, J. , Blacket M. J., Brown K., and Lynch S. E.. 2016. “Molecular Identification of Mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae) in Southeastern Australia.” Ecology and Evolution 6, no. 9: 3001–3011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batovska, J. , Lynch S. E., Cogan N. O. I., et al. 2018. “Effective Mosquito and Arbovirus Surveillance Using Metabarcoding.” Molecular Ecology Resources 18, no. 1: 32–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beebe, N. W. 2018. “DNA Barcoding Mosquitoes: Advice for Potential Prospectors.” Parasitology 145, no. 5: 622–633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beebe, N. W. , Maung J., van den Hurk A. F., Ellis J. T., and Cooper R. D.. 2001. “Ribosomal DNA Spacer Genotypes of the Anopheles Bancroftii Group (Diptera: Culicidae) From Australia and Papua New Guinea.” Insect Molecular Biology 10, no. 5: 407–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beebe, N. W. , van den Hurk A. F., Chapman H. F., Frances S. P., Williams C. R., and Cooper R. D.. 2002. “Development and Evaluation of a Species Diagnostic Polymerase Chain Reaction‐Restriction Fragment‐Length Polymorphism Procedure for Cryptic Members of the Culex Sitiens (Diptera: Culicidae) Subgroup in Australia and the Southwest Pacific.” Journal of Medical Entomology 39, no. 2: 362–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourke, B. P. , Oliveira T. P., Suesdek L., Bergo E. S., and Sallum M. A.. 2013. “A Multi‐Locus Approach to Barcoding in the Anopheles Strodei Subgroup (Diptera: Culicidae).” Parasites & Vectors 6: 111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Candek, K. , and Kuntner M.. 2015. “DNA Barcoding Gap: Reliable Species Identification Over Morphological and Geographical Scales.” Molecular Ecology Resources 15, no. 2: 268–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaiphongpachara, T. , Changbunjong T., Laojun S., et al. 2022. “Mitochondrial DNA Barcoding of Mosquito Species (Diptera: Culicidae) in Thailand.” PLoS One 17, no. 9: e0275090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan, A. , Chiang L. P., Hapuarachchi H. C., et al. 2014. “DNA Barcoding: Complementing Morphological Identification of Mosquito Species in Singapore.” Parasites & Vectors 7: 569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan‐Chable, R. J. , Martinez‐Arce A., Mis‐Avila P. C., and Ortega‐Morales A. I.. 2019. “DNA Barcodes and Evidence of Cryptic Diversity of Anthropophagous Mosquitoes in Quintana Roo Mexico.” Ecology and Evolution 9, no. 8: 4692–4705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman, H. F. , Kay B. H., Ritchie S. A., van den Hurk A. F., and Hughes J. M.. 2000. “Definition of Species in the Culex Sitiens Subgroup (Diptera: Culicidae) From Papua New Guinea and Australia.” Journal of Medical Entomology 37, no. 5: 736–742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheryl Johansen, J. N. , Power S., Wong S., et al. 2014. The University of Western Australia Arbovirus Surveillance and Research Laboratory Annual Report: 2013–2014. Perth, Australia: University of Western Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Cywinska, A. , Hunter F. F., and Hebert P. D. N.. 2006. “Identifying Canadian Mosquito Species Through DNA Barcodes.” Medical and Veterinary Entomology 20, no. 4: 413–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endersby, N. M. , White V. L., Chan J., et al. 2013. “Evidence of Cryptic Genetic Lineages Within Aedes Notoscriptus (Skuse).” Infection, Genetics and Evolution 18: 191–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foley, D. H. , Bryan J. H., and Wilkerson R. C.. 2007. “Species‐Richness of the Anopheles Annulipes Complex (Diptera: Culicidae) Revealed by Tree and Model‐Based Allozyme Clustering Analyses.” Biological Journal of the Linnean Society 91, no. 3: 523–539. [Google Scholar]

- Foley, D. H. , Wilkerson R. C., Cooper R. D., Volovsek M. E., and Bryan J. H.. 2007. “A Molecular Phylogeny of Anopheles Annulipes (Diptera: Culicidae) Sensu Lato: The Most Species‐Rich Anopheline Complex.” Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 43, no. 1: 283–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folmer, O. , Black M., Hoeh W., Lutz R., and Vrijenhoek R.. 1994. “DNA Primers for Amplification of Mitochondrial Cytochrome c Oxidase Subunit I From Diverse Metazoan Invertebrates.” Molecular Marine Biology and Biotechnology 3, no. 5: 294–299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster, P. G. , Bergo E. S., Bourke B. P., et al. 2013. “Phylogenetic Analysis and DNA‐Based Species Confirmation in Anopheles (Nyssorhynchus).” PLoS One 8, no. 2: e54063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harbach, R. E. 2023. “Mosquito Taxonomic Inventory.” https://mosquito‐taxonomic‐inventory.myspecies.info/valid‐species‐list.

- Hasan, A. U. , Suguri S., Ahmed S. M., et al. 2009. “Molecular Phylogeography of Culex Quinquefasciatus Mosquitoes in Central Bangladesh.” Acta Tropicaica 112, no. 2: 106–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hebert, P. D. , Cywinska A., Ball S. L., and deWaard J. R.. 2003. “Biological Identifications Through DNA Barcodes.” Proceedings of the Biological Sciences 270, no. 1512: 313–321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hebert, P. D. , and Gregory T. R.. 2005. “The Promise of DNA Barcoding for Taxonomy.” Systematic Biology 54, no. 5: 852–859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemmerter, S. , Slapeta J., and Beebe N. W.. 2009. “Resolving Genetic Diversity in Australasian Culex Mosquitoes: Incongruence Between the Mitochondrial Cytochrome c Oxidase I and Nuclear Acetylcholine Esterase 2.” Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 50, no. 2: 317–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansen, C. C. , Hemmerter S., van den Hurk A. F., Whelan P. I., and Beebe N. W.. 2013. “Morphological Versus Molecular Identification of Culex Annulirostris Skuse and Culex Palpalis Taylor: Key Members of the Culex Sitiens (Diptera: Culicidae) Subgroup in Australasia.” Australian Journal of Entomology 52, no. 4: 356–362. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, Y. , Ashton L., Pedley S. M., et al. 2013. “Reliable, Verifiable and Efficient Monitoring of Biodiversity via Metabarcoding.” Ecology Letters 16, no. 10: 1245–1257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasai, S. , Komagata O., Tomita T., et al. 2008. “PCR‐Based Identification of Culex Pipiens Complex Collected in Japan.” Japanese Journal of Infectious Diseases 61, no. 3: 184–191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katoh, K. , Misawa K., Kuma K., and Miyata T.. 2002. “MAFFT: A Novel Method for Rapid Multiple Sequence Alignment Based on Fast Fourier Transform.” Nucleic Acids Research 30, no. 14: 3059–3066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katoh, K. , and Standley D. M.. 2013. “MAFFT Multiple Sequence Alignment Software Version 7: Improvements in Performance and Usability.” Molecular Biology and Evolution 30, no. 4: 772–780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura, M. 1980. “A Simple Method for Estimating Evolutionary Rates of Base Substitutions Through Comparative Studies of Nucleotide Sequences.” Journal of Molecular Evolution 16, no. 2: 111–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, N. P. , Rajavel A. R., Natarajan R., and Jambulingam P.. 2007. “DNA Barcodes Can Distinguish Species of Indian Mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae).” Journal of Medical Entomology 44, no. 1: 1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, S. , Stecher G., Li M., Knyaz C., and Tamura K.. 2018. “MEGA X: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Across Computing Platforms.” Molecular Biology and Evolution 35, no. 6: 1547–1549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurito, M. , Oliveira T. M., Almiron W. R., and Sallum M. A.. 2013. “COI Barcode Versus Morphological Identification of Culex (Culex) (Diptera: Culicidae) Species: A Case Study Using Samples From Argentina and Brazil.” Memórias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz 108, no. Suppl 1: 110–122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, D. J. , Hicks M. M., Griffiths M., Russell R. C., and Marks E. N.. 1984. The Culicidae of the Australasian Region. Canberra: Australian Government Publishing Service. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, E. N. , Bryan J. H., and Russell R. C.. 1989. Genus Culex, subgenera Acallyntrum, Culex, edited by Debenham M. L.. Canberra: Australian Government Publishing Service. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Y. , Seifert S. N., Nieman C. C., et al. 2012. “High Degree of Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms in California Culex Pipiens (Diptera: Culicidae) Sensu Lato.” Journal of Medical Entomology 49, no. 2: 299–306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liehne, P. F. S. 1991. An Atlas of the Mosquitoes of Western Australia. Perth: Health Department of Western Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Linton, Y. M. 2009. “The First Barcode Release Paper. Third International Barcode of Life Conference.”

- Lunt, D. H. , Zhang D. X., Szymura J. M., and Hewitt G. M.. 1996. “The Insect Cytochrome Oxidase I Gene: Evolutionary Patterns and Conserved Primers for Phylogenetic Studies.” Insect Molecular Biology 5, no. 3: 153–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meier, R. , Zhang G. Y., and Ali F.. 2008. “The Use of Mean Instead of Smallest Interspecific Distances Exaggerates the Size of the "Barcoding Gap" and Leads to Misidentification.” Systematic Biology 57, no. 5: 809–813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noureldin, E. , Tan D., Daffalla O., et al. 2022. “DNA Barcoding of Potential Mosquito Disease Vectors (Diptera, Culicidae) in Jazan Region, Saudi Arabia.” Pathogens 11, no. 5: 486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puillandre, N. , Brouillet S., and Achaz G.. 2021. “ASAP: Assemble Species by Automatic Partitioning.” Molecular Ecology Resources 21, no. 2: 609–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puslednik, L. , Russell R. C., and Ballard J. W. O.. 2012. “Phylogeography of the Medically Important Mosquito Aedes (Ochlerotatus) Vigilax (Diptera: Culicidae) in Australasia.” Journal of Biogeography 39, no. 7: 1333–1346. [Google Scholar]

- Ratnasingham, S. , and Hebert P. D.. 2007. “bold: The Barcode of Life Data System (http://www.barcodinglife.org).” Molecular Ecology Notes 7, no. 3: 355–364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratnasingham, S. , and Hebert P. D. N.. 2013. “A DNA‐Based Registry for all Animal Species: The Barcode Index Number (BIN) System.” PLoS One 8, no. 7: e66213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinert, J. F. , Harbach R. E., and Kitching I. J.. 2009. “Phylogeny and Classification of Tribe Aedini (Diptera: Culicidae).” Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 157, no. 4: 700–794. [Google Scholar]

- Rohe, D. L. , and Fall R. P.. 1979. “A Miniature Battery Powered CO2 Baited Light Trap for Mosquito Borne Encephalitis Surveillance.” Bulletin of the Society of Vector Ecologists 4: 24–27. [Google Scholar]

- Rozas, J. , Ferrer‐Mata A., Sanchez‐DelBarrio J. C., et al. 2017. “DnaSP 6: DNA Sequence Polymorphism Analysis of Large Data Sets.” Molecular Biology and Evolution 34, no. 12: 3299–3302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell, R. C. 2012. “A Review of the Status and Significance of the Species Within the Culex Pipiens Group in Australia.” Journal of the American Mosquito Control Association 28, no. 4 Suppl: 24–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell, R. C. , and Debenham M. L.. 1996. A Colour Photo Atlas of Mosquitoes of Southeastern Australia, edited by Russell R. C. and Debenham M. L.. Sydney: R.C. Russell. [Google Scholar]

- Sheraliev, B. , and Peng Z. G.. 2021. “Molecular Diversity of Uzbekistan's Fishes Assessed With DNA Barcoding.” Scientific Reports 11, no. 1: 16894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith, J. L. , and Fonseca D. M.. 2004. “Rapid Assays for Identification of Members of the Culex (Culex) Pipiens Complex, Their Hybrids, and Other Sibling Species (Diptera: Culicidae).” American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 70, no. 4: 339–345. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sumruayphol, S. , Chaiphongpachara T., Samung Y., et al. 2020. “Seasonal Dynamics and Molecular Differentiation of Three Natural Anopheles Species (Diptera: Culicidae) of the Maculatus Group (Neocellia Series) in Malaria Hotspot Villages of Thailand.” Parasites & Vectors 13, no. 1: 574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Versteirt, V. , Nagy Z. T., Roelants P., et al. 2015. “Identification of Belgian Mosquito Species (Diptera: Culicidae) by DNA Barcoding.” Molecular Ecology Resources 15, no. 2: 449–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, G. , Li C. X., Guo X. X., et al. 2012. “Identifying the Main Mosquito Species in China Based on DNA Barcoding.” PLoS One 7, no. 10: e47051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb, C. E. , and Russell R.. 2016. A Guide to Mosquoties of Australia. Victoria: CSIRO Publishing. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Details of mosquito species used in this study.

Table S2. Barcode records and medical importance of mosquito species sequenced in this study.

Data Availability Statement

All barcode sequences used in this study are uploaded into the BOLD Database under the project Western Australia Mosquitoes (WAMOS) with BOLD accession numbers from WAMOS001‐21 to WAMOS177‐21. The sequences were also stored on NCBI GenBank under the accession numbers PP145112 to PP145288. The photographs of mosquito species described in this study can be found at the following web address: https://www.health.wa.gov.au/~/media/Corp/Documents/Health‐for/Mosquitoes/PDF/Species‐Sheets‐for‐Mosquitoes‐in‐WA‐updated.pdf