Abstract

Objective

With an aging population and higher prevalence of dementia, there is a paucity of data regarding dementia patients undergoing cardiovascular surgery. We examined the nationwide trends and outcomes of cardiovascular surgery patients with dementia to determine its effect on morbidity, mortality, and discharge disposition.

Methods

From 2002 to 2014, 11,414 (0.27%) of the 4,201,697 cardiac surgery patients from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample had a preoperative diagnosis of dementia. Propensity-score matching was used to balance dementia and non-dementia groups. Primary outcomes included postoperative morbidity, mortality, and discharge to skilled nursing facility (SNF).

Results

Dementia patients were more often male (67%) and 65–84 years old (84%). Postoperative mortality among patients with dementia was lower compared to patients without dementia (3.4% vs. 4.6%, p < 0.05). In dementia patients, there were more complications (65% vs. 60%, p < 0.01), more blood transfusions [OR 1.3, 95%CI (1.1, 1.5), p < 0.01] and delirium [OR 3.6, 95%CI (2.9, 4.5), p < 0.0001). Dementia patients (n = 5,623, 49.8%) were twice as likely to be discharged to SNF [OR 2.1, 95%CI (1.9, 2.4), p < 0.0001]. Dementia patients discharged to SNF more often had delirium (18.2% vs. 12%, p < 0.01), renal complications (17% vs. 8%, p < 0.01), and prolonged mechanical ventilation (15% vs. 8%, p < 0.01).

Conclusions

Despite an aging population with increasing prevalence of dementia, patients with dementia can undergo cardiovascular surgery with a lower in-hospital mortality and similar hospitalization costs compared to their non-dementia counterparts. Dementia patients are more likely to experience complications and require discharge to skilled nursing facility. Careful patient selection and targeted physical therapy may help mitigate some dementia associated complications.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13019-024-03120-z.

Keywords: Dementia, CABG, Valve procedures, Aortic procedures, Trends, Outcomes, Mortality, Stroke, Delirium

Background

Cardiovascular surgery (CVS) is becoming safer and more effective, especially in the elderly population [1, 2]. However, an aging world population has led to an increased prevalence of dementia [3], resulting in more nuanced perioperative evaluation [4, 5]. Current literature demonstrates poor outcomes after non-cardiovascular surgery in patients with pre-operative dementia. These patients have increased rate of complications, higher 90-day mortality, longer pre- and post-operative length of stay, longer intensive care unit length of stay, and higher total hospital cost [5–8]. However, cardiovascular surgical outcomes in this population have not been well-established.

Understanding these outcomes will help determine whether pre-operative dementia should serve as an independent risk factor for mortality after open cardiovascular surgery and more specifically help guide the recommended therapy (serial percutaneous interventions and medical management vs. open cardiovascular surgery). In order to answer this question in a relatively homogenous group of dementia patients, we felt that it was prudent to examine patients within a timeframe precluding mainstream adoption of structural cardiology interventions such as transcatheter aortic valve implantation/replacement (TAVI/TAVR), transcatheter edge to edge repair of mitral valve (TEER), or transcatheter mitral valve replacement (TMVR).

Our objective was to use a large national database to determine which patients undergoing CVS had preoperative dementia, and compare their postoperative mortality, complications and discharge disposition as compared to their non-dementia counterparts. Risk factors associated with higher discharge acuity were also identified in the dementia group.

Patients and methods

Data

The National Inpatient Sample (NIS) Healthcare Cost Utilization Project (HCUP) database is the largest all-payer inpatient discharge database and represents a 20% stratified sample of all discharges occurring in a given year. This cross sectional analysis of the NIS was queried from 2002 to 2014 for patients undergoing cardiovascular surgery in the United States, specifically coronary artery bypass grafts (CABG), valve procedures, aortic procedures, or multi-component procedures. Patients were identified using the 2003 International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) diagnosis and procedure codes. Patients undergoing CVS and dementia were identified based on ICD-9-CM codes. The Institutional Review Board at Cleveland Clinic determined that the use of NIS publicly available data does not contain any identifiable information and is not considered “human subject research” and therefore does not require IRB approval.

Outcomes

Outcomes included in-hospital mortality, complications, length of stay (LOS), discharge disposition, and hospitalization cost. Complications included stroke, blood transfusion, infection, pneumonia, cardiac syndrome, respiratory, PE, DVT, gastrointestinal syndromes, mental disorder, ventilation, pain, and sepsis and were identified through secondary ICD-9 codes. Discharge disposition was defined as routine discharge to home, home with home healthcare, transfer to another inpatient facility, and transfer to another facility (e.g. long-term acute care and skilled nursing facilities). Hospitalization costs were adjusted for inflation and converted to 2019 US dollars using the Consumer Price Index.

Covariables

Patient characteristics included age, sex, race, admission status, median household income, insurance status, and comorbidities. Admission status was categorized as elective or urgent.

To stratify for surgical risk, comorbidities were derived from secondary ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes using The Elixhauser Comorbidity Score (ECS) [9]. ECS was applied instead of the risk score stratification suggested by the Society of Thoracic Surgeons (http://riskcalc.sts.org/stswebriskcalc/#/calculate), because the latter risk analysis implements variables that may not appear in the ICD-9 diagnosis code-based NIS database. For our investigation, patients were stratified by ECS into low (0–5), medium (6–15), and high-risk (> 15) categories.

Hospital-level characteristics included hospital location, bed size, teaching status, and ownership. Hospital region was classified as Northeast, Midwest, South, or West according to the United States Census Bureau. Hospital bed size was classified as small, medium, or large based on an HCUP-developed algorithm.

Statistical analysis

Chi-square tests were calculated to compare categorical variables. To assess linear trends of complications over time (years), the Mantel-Haenszel Chi-square test was used. All P-values were two-tailed and P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Patients with dementia undergoing CVS were compared to those without dementia. To adjust for possible confounding covariates, One to one greedy propensity score matching (PSM) with a caliper of 0.1 times the mean of the standard deviation of log propensity score was used to balance the groups. The model was constructed using a forward selection algorithm, with patient demographic variables and hospital volume, as a categorical variable, forced into the model. All other terms with a multivariate regression P > 0.05 were excluded from the model. To account for clustering of cases at the hospital level, the final model was constructed as a hierarchical model, in which a grouping term for hospitals was entered as a random effect. Patient-level predictor variables included patient demographics, (age, gender, and race as categories), comorbidities, and prior cardiac procedures as determined by secondary diagnoses for admission. The final propensity matched cohort included 11,294 pairs of patients with and without dementia who were well-matched. Outcomes between the dementia group and non-dementia group using differences in means with paired t tests and conditional logistic regression for in-hospital mortality and complications. Weighted estimates are reported throughout. All statistical analyses were performed with SAS.

Results

Patient characteristics

There were 4,201,697 patients who underwent cardiovascular surgery in the NIS for analysis, with 11,414 (0.27%) who had a diagnosis of dementia (Table 1). Prior to propensity matching, the distribution of CVS procedures was similar between both dementia and non-dementia patients (Table 1). Within the dementia group, 17% (n = 1,926) of patients were low-risk, 64% (n = 7,206) were medium-risk, and 19% (n = 2,208) were high-risk (Supplemental Table 1). The distribution of the type of CVS procedure was similar across risk groups (Supplemental Table 1).

Table 1.

Unmatched patient demographics

| Variable | Dementia N = 11,414 (0.27%) |

No dementia N = 4,190,283 (99.73%) |

Chi-square P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y)* | < 0.0001 | ||

| 18–44 | 14 (0.1) | 198,119 (4.7) | |

| 45–54 | 189 (1.7) | 551,591 (13.2) | |

| 55–64 | 727 (6.4) | 1,084,974 (25.9) | |

| 65–74 | 3,349 (29.3) | 1,312,970 (31.3) | |

| 75–84 | 6,228 (54.6) | 928,837 (22.2) | |

| 85–99 | 907 (7.9) | 113,793 (2.7) | |

| Sex* | 0.26 | ||

| Male | 7,672 (67.2) | 2,862,153 (68.3) | |

| Female | 3,742 (32.8) | 1,327,732 (31.7) | |

| Race | < 0.0001 | ||

| White | 7,675 (67.2) | 2,665,037 (63.6) | |

| Black | 638 (5.6) | 221,379 (5.3) | |

| Hispanic | 699 (6.1) | 225,692 (5.4) | |

| Other/Missing | 2,402 (21) | 1,078,175 (25.7) | |

| Median Household Income | 0.0959 | ||

| 1st | 2,857 (25) | 952,411 (22.7) | |

| 2nd | 2,805 (24.6) | 1,066,809 (22.5) | |

| 3rd | 2,691 (23.6) | 1,027,499 (24.5) | |

| 4th | 2,842 (24.9) | 1,040,487 (24.8) | |

| Missing | 219 (1.9) | 103,077 (2.5) | |

| Insurance | < 0.0001 | ||

| Medicare | 9,913 (86.8) | 2,276,133 (54.3) | |

| Medicaid | 249 (2.2) | 223,772 (5.3) | |

| Private | 1,052 (9.2) | 1,424,973 (34) | |

| Uninsured | 76 (0.7) | 134,380 (3.2) | |

| Other | 106 (0.9) | 123,881 (3) | |

| Missing | 18 (0.2) | 7,144 (0.2) | |

| Hospital Location/teaching status | 0.043 | ||

| Rural | 371 (3.3) | 147,824 (3.5) | |

| Urban/nonteaching | 4,257 (37.3) | 1,445,941 (34.5) | |

| Urban/teaching | 6,741 (59.1) | 2,582,062 (61.6) | |

| Missing | 45 (0.4) | 14,456 (0.3) | |

| Hospital Region | 0.004 | ||

| Northeast | 2,458 (21.5) | 769,913 (18.4) | |

| Midwest | 2,688 (23.6) | 1,005,976 (24) | |

| South | 4,475 (39.2) | 1,679,865 (40.1) | |

| West | 1,794 (15.7) | 734,530 (17.5) | |

| Hospital Bed size | 0.493 | ||

| Small | 664 (5.8) | 269,977 (6.4) | |

| Medium | 2,146 (18.8) | 796,282 (19) | |

| Large | 8,560 (75) | 3,109,569 (74.2) | |

| Missing | 44 (0.4) | 14,455 (0.3) | |

| Hospital Ownership | 0.009 | ||

| Government | 737 (6.5) | 332,616 (7.9) | |

| Private, not-profit | 9,005 (78.9) | 3,306,454 (78.9) | |

| Private, invest-own | 1,551 (13.6) | 509,213 (12.2) | |

| Missing | 121 (1.1) | 42,000 (1) | |

| Surgery Status* | < 0.0001 | ||

| Not elective | 6,488 (56.8) | 2,012,864 (48) | |

| Elective | 4,882 (42.8) | 2,169,068 (51.8) | |

| Missing | 44 (0.4) | 8,351 (0.2) | |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Alcohol abuse | 945 (8.3) | 102,613 (2.4) | < 0.0001 |

| Arrhythmia | 6,025 (52.8) | 1,875,504 (44.8) | < 0.0001 |

| Iron deficiency anemia | 1,917 (16.8) | 643,976 (15.4) | 0.0762 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 159 (1.4) | 77,013 (1.8) | 0.1094 |

| Blood loss anemia | 176 (1.5) | 54,930 (1.3) | 0.3344 |

| Congestive heart failure* | 175 (1.5) | 57,657 (1.4) | 0.565 |

| Chronic lung disease* | 2,686 (23.5) | 878,238 (21) | 0.0037 |

| Coagulopathy | 2,109 (18.5) | 600,526 (14.3) | < 0.0001 |

| Depression | 1,038 (9.1) | 213,454 (5.1) | < 0.0001 |

| Diabetes mellitus* | 3,592 (31.5) | 1,372,283 (32.7) | 0.1227 |

| Drug abuse | 155 (1.4) | 48,725 (1.2) | 0.3855 |

| Hypertension* | 7,996 (70.1) | 2,814,016 (67.2) | 0.0094 |

| Hypothyroidism | 1,294 (11.3) | 346,008 (8.3) | < 0.0001 |

| Liver disease* | 125 (1.1) | 48,408 (1.2) | 0.7547 |

| Lymphoma | 38 (0.3) | 17,825 (0.4) | 0.4592 |

| Fluid and electrolyte imbalance | 2,772 (24.3) | 948,350 (22.6) | 0.0783 |

| Metastatic cancer | 19 (0.2) | 7,319 (0.2) | 0.9063 |

| Neurological disorders | 8,360 (73.2) | 125,302 (3) | < 0.0001 |

| Obesity* | 906 (7.9) | 595,569 (14.2) | < 0.0001 |

| Paralysis | 197 (1.7) | 54,721 (1.3) | 0.0821 |

| Peripheral vascular disease* | 1,808 (15.8) | 566,329 (13.5) | 0.0014 |

| Psychoses | 528 (4.6) | 64,282 (1.5) | < 0.0001 |

| Pulmonary circulation disorders | 25 (0.2) | 12,642 (0.3) | 0.4452 |

| Renal failure* | 1,404 (12.3) | 438,860 (10.5) | 0.0059 |

| Solid tumor without metastasis | 229 (2) | 58,788 (1.4) | 0.0159 |

| Peptic ulcer disease | 15 (0.1) | 6,911 (0.2) | 0.7094 |

| Valvular disease | 117 (1) | 35,356 (0.8) | 0.3485 |

| Weight loss | 524 (4.6) | 114,127 (2.7) | < 0.0001 |

| Procedure | 0.219 | ||

| CABG | 7,675 (67.2) | 2,827,861 (67.5) | |

| Valve | 1,919 (16.8) | 745,814 (17.8) | |

| Aortic | 156 (1.4) | 62,341 (1.5) | |

| Multi-component | 1,664 (14.6) | 554,267 (13.2) | |

| Elixhauser comorbidity score | 11+/- 0.13 | 5 +/- 0.04 | < 0.0001 |

*Denotes variables used for propensity matching

Trends in cardiovascular surgeries on patients with preoperative dementia

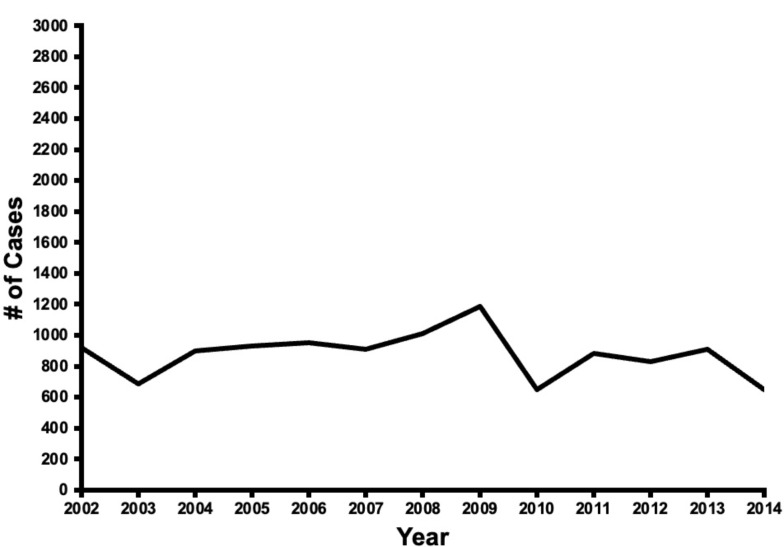

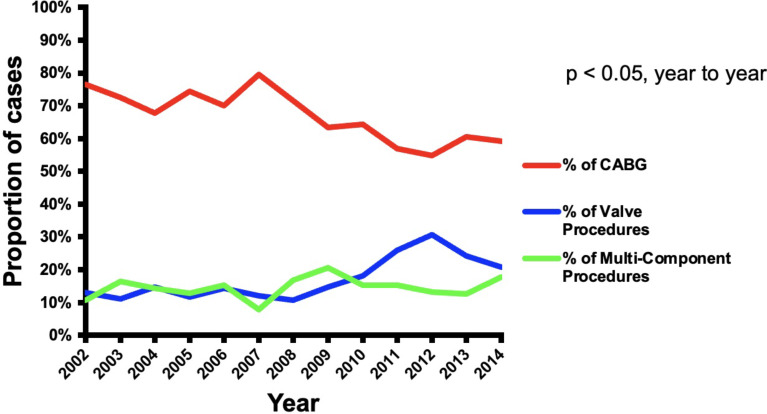

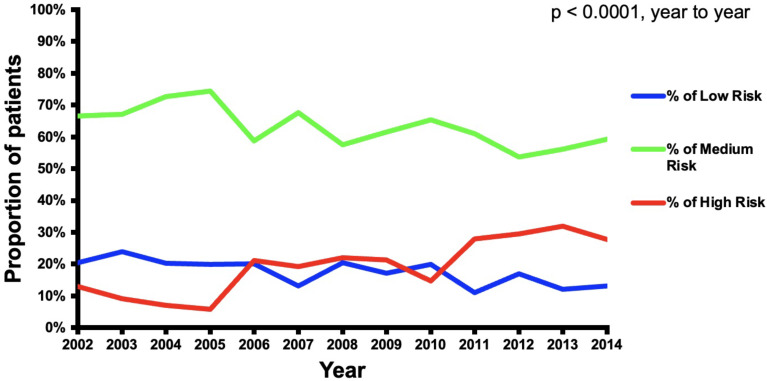

The number of CVS cases with preoperative dementia in the United States remained fairly constant over the duration of the study (Fig. 1). CABG procedures represented 77% of the CVS procedures in 2002 and then declined to 59% of the cases in 2014 (p < 0.01). Valve procedures represented 13% of the cases in 2002 and increased to 21% in 2014 (p < 0.01). Multi-component procedures increased throughout the duration of the study from 11% of cases in 2002 to 18% in 2014 (p < 0.05) (Fig. 2). Over the duration of the study, the proportion of low-risk and medium-risk patients decreased from 21 to 13% and 67–59%, respectively, while the proportion of high-risk patients increased from 13 to 28% (p < 0.01) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 1.

Trends in cardiovascular surgery operations on patients with preoperative dementia over the study period (2002–2014)

Fig. 2.

Trends of CABG, valve procedures, and multicomponent procedures over the study period (2002–2014)

Fig. 3.

Trends of cardiovascular operations stratified by dementia risk over the study period (2002–2014)

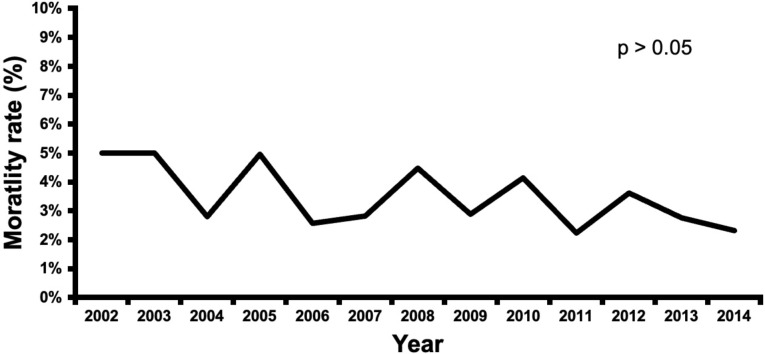

Postoperative outcomes after propensity matching

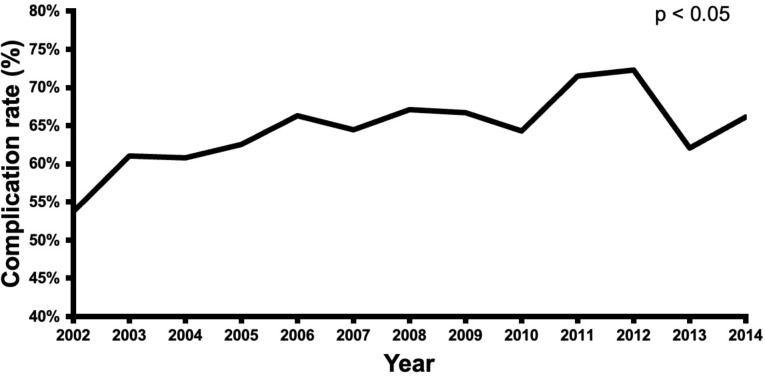

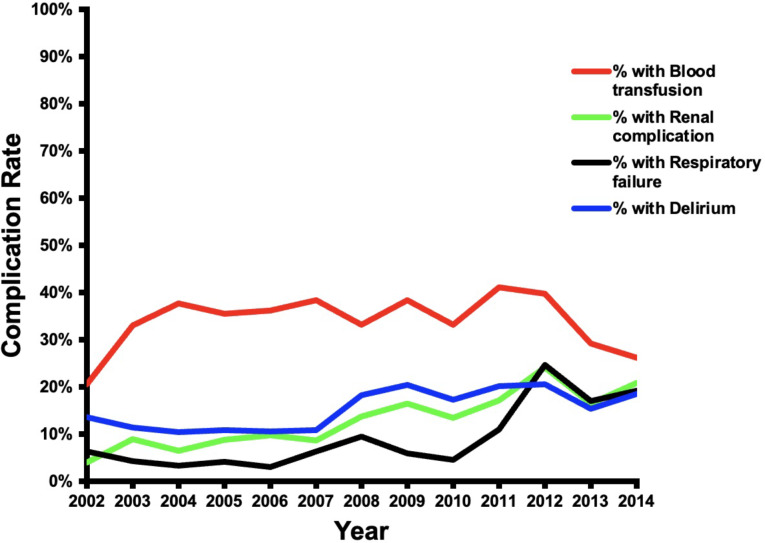

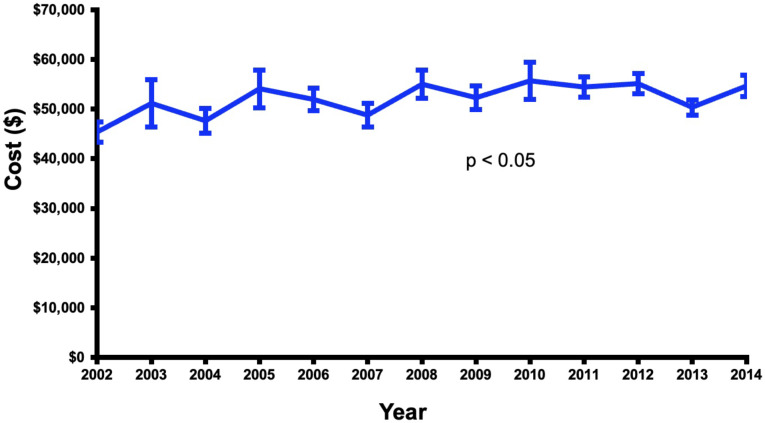

CVS patients with dementia had a lower mortality rate than the non-dementia group (3.4% vs. 4.6%, p < 0.05), (Table 2). Over the duration of the study, the dementia group had a trend toward lower in-hospital mortality (Fig. 4). However, the dementia group had more postoperative complications as compared to the non-dementia group (65% vs. 59%, p < 0.01) (Table 2), with an increasing rate of complications (p < 0.05) over the course of the study (Fig. 5). Dementia patients had more blood transfusions (34% vs. 29%, p < 0.01) and delirium (15% vs. 5%, p < 0.01). In the dementia cohort, blood transfusions and delirium also increased by 13% and 1% (Fig. 6). However, the dementia group had a lower rate of cardiovascular complications (15% vs. 19%, p < 0.01). Hospital length of stay was 12 ± 0.2 days for the dementia group and 11 ± 0.2 for the non-dementia group (p < 0.01) (Table 2). The difference in average hospitalization cost for the dementia group and non-dementia group was not statistically significant (p > 0.05) (Table 2). Over the duration of the study, the cost for the dementia group remained constant (Fig. 7). High-risk dementia patients as determined by ECS, were more likely to have complications and hospital mortality as compared to low and medium risk dementia patients (Supplemental Table 2).

Table 2.

Postoperative outcomes after propensity matching

| Variable | Dementia N = 11,294 (50%) |

No dementia N = 11,257 (50%) |

Chi-square P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hospital Mortality | 385 (3.4) | 519 (4.6) | 0.0362 |

| Complications | |||

| Any complication | 7,326 (64.9) | 6,706 (59.6) | 0.0002 |

| Infections | 107 (0.9) | 98 (0.9) | 0.7893 |

| Cardiovascular complications | 1,718 (15.2) | 2,101 (18.7) | 0.0022 |

| Stroke | 400 (3.5) | 343 (3) | 0.3462 |

| Blood transfusion | 3,871 (34.3) | 3,224 (28.6) | < 0.0001 |

| Renal complication | 1,462 (12.9) | 1,665 (14.8) | 0.0718 |

| Respiratory failure | 1,002 (8.9) | 1,084 (9.6) | 0.3716 |

| Pneumonia | 895 (7.9) | 763 (6.8) | 0.1262 |

| Pulmonary embolism | 63 (0.6) | 34 (0.3) | 0.1959 |

| Deep vein thrombosis | 117 (1) | 129 (1.1) | 0.7419 |

| Ileus/GI complications | 182 (1.6) | 261 (2.3) | 0.0921 |

| Mechanical ventilation | 1,315 (11.6) | 1,280 (11.4) | 0.7769 |

| Prolonged postoperative pain | 25 (0.2) | 55 (0.5) | 0.1286 |

| Sepsis | 286 (2.5) | 434 (3.9) | 0.0113 |

| Delirium | 1,738 (15.4) | 536 (4.8) | < 0.0001 |

| Discharge Status | |||

| Home healthcare | 3,010 (26.7) | 3,378 (30) | 0.0128 |

| Home, Routine | 2,098 (18.6) | 3,647 (32.4) | < 0.0001 |

| Transfer to short-term hospital | 132 (1.2) | 100 (0.9) | 0.37 |

| Transfer to other, SNF | 5,623 (50) | 3,593 (31.9) | < 0.0001 |

| Other | 418 (3.7) | 525 (4.7) | 0.1068 |

| Length of stay | 12 days +/- 0.2 | 11 days +/- 0.21 |

T test p = 0.0066 |

| Total cost set to 2019 inflation | $52,045 +/- 784 | $52,710 +/- 1,002 |

T test p = 0.5873 |

Fig. 4.

Trends in mortality after cardiovascular surgery in patients with preoperative dementia over the study period (2002–2014)

Fig. 5.

Trends in morbidity after cardiovascular surgery in patients with preoperative dementia over the study period (2002–2014)

Fig. 6.

Trends of specific complications after cardiovascular surgery in patients with preoperative dementia over the study period (2002–2014)

Fig. 7.

Trends of total cost of hospitalization (adjusted to 2019 inflation) after cardiovascular surgery in patients with preoperative dementia over the study period (2002–2014)

Discharge disposition in the dementia group

The dementia group had more patients discharged to skilled nursing facility (50% vs. 32%, p < 0.01) and a lower odds of discharge to home with (OR 0.85, 95% CI(0.74, 0.97), p < 0.05) and without healthcare (OR 0.48, 95%CI(0.41, 0.55), p < 0.01) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Effect of Preoperative Dementia on propensity-matched outcomes

| Variable | Odds ratio (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| Mortality | 0.730 (0.543,0.981) | < 0.05 |

| Complications | ||

| Any complication | 1.253 (1.114,1.409) | < 0.01 |

| Stroke | 1.169 (0.844,1.619) | 0.35 |

| Blood transfusion | 1.299 (1.143,1.476) | < 0.01 |

| Wound infection | 1.088 (0.584,2.028) | 0.79 |

| Renal complication | 0.856 (0.723,1.014) | 0.07 |

| Pneumonia | 1.185 (0.953,1.474) | 0.13 |

| Cardiac complications | 0.782 (0.668,0.915) | < 0.01 |

| Respiratory failure | 0.914 (0.750,1.114) | 0.37 |

| Pulmonary embolism | 1.816 (0.724,4.553) | 0.2 |

| Deep vein thrombosis | 0.907 (0.507,1.623) | 0.74 |

| Ileus/GI complications | 0.691 (0.448,1.065) | 0.09 |

| Mechanical ventilation | 1.027 (0.854,1.235) | 0.78 |

| Prolonged postoperative pain | 0.448 (0.155,1.298) | 0.14 |

| Sepsis | 0.647 (0.461,0.909) | < 0.05 |

| Delirium | 3.635 (2.907,4.545) | < 0.01 |

| Discharge Status | ||

| Home health care | 0.848 (0.744,0.965) | < 0.05 |

| Routine, home | 0.476 (0.413,0.548) | < 0.01 |

| Transfer to short-term hospital | 1.311 (0.723,2.377) | 0.37 |

| Transfer to other, SNF | 2.115 (1.870,2.392) | < 0.01 |

| Other | 0.787 (0.588,1.054) | 0.11 |

In the dementia group, those discharged to SNF or short-term hospital had more delirium (18% vs. 12%, p < 0.01), renal complications (17% vs. 8%, p < 0.01), mechanical ventilation (15% vs. 8%, p < 0.01), respiratory failure (12% vs. 5%, p < 0.01), pneumonia (10% vs. 5%, p < 0.01), stroke (5.1% vs. 1.6%, p < 0.01), sepsis (4% vs. 1%, p < 0.01), and deep vein thrombosis (1.4% vs. 0.6%, p < 0.05) as compared to the dementia patients discharged home (Table 4). Additionally, high-risk dementia patients were more likely have longer length of stay, more expensive hospitalization and discharge to skilled care facility compared to the low and medium-risk dementia patients (Supplemental Table 2).

Table 4.

Postoperative outcomes of dementia patients, by discharge status

| Variable | Home or home healthcare N = 5108 |

SNF, short-term hospital N = 6173 |

p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hospital Mortality | 0 | 0.0% | 385 | 6.2% | N.A. |

| Complications | |||||

| Any complication | 3,021 | 59.1% | 4,300 | 69.7% | < 0.01 |

| Stroke | 84 | 1.6% | 315 | 5.1% | < 0.01 |

| Blood transfusion | 1,706 | 33.4% | 2,161 | 35.0% | 0.41 |

| Wound infection | 29 | 0.6% | 78 | 1.3% | 0.09 |

| Renal complication | 413 | 8.1% | 1,045 | 16.9% | < 0.01 |

| Pneumonia | 254 | 5.0% | 641 | 10.4% | < 0.01 |

| Cardiac complications | 717 | 14.0% | 1,001 | 16.2% | 0.13 |

| Respiratory failure | 253 | 5.0% | 750 | 12.1% | < 0.01 |

| Pulmonary embolism | 18 | 0.4% | 44 | 0.7% | 0.25 |

| Deep vein thrombosis | 29 | 0.6% | 88 | 1.4% | < 0.05 |

| Ileus/GI complications | 84 | 1.6% | 98 | 1.6% | 0.92 |

| Mechanical ventilation | 422 | 8.3% | 893 | 14.5% | < 0.01 |

| Prolonged postoperative pain | * | * | 14 | 0.2% | 0.88 |

| Sepsis | 51 | 1.0% | 235 | 3.8% | < 0.01 |

| Delirium | 611 | 12.0% | 1,126 | 18.2% | < 0.01 |

Discussion

Patients with dementia undergoing cardiovascular surgery have lower rates of postoperative mortality compared to their non-dementia counterparts. Hospital length of stay was only longer by one day on average without increased hospitalization cost. However, due to higher rates of delirium complications, patients with dementia were more likely to be discharged to skilled nursing facility. In the dementia group, those discharged to skilled nursing facility were more likely to have neurologic, renal and respiratory complications.

In non-cardiovascular surgery, it has been shown that postoperative complications in patients with dementia lead to poor long term outcomes [4–7, 10]. A large part of these complications likely stem from the patient’s innate inability to fully participate in postoperative physical therapy. This is often exacerbated by postoperative delirium, which preoperative dementia happens to be a major risk factor [11, 12]. After cardiovascular surgery, delirium will often manifest as respiratory related complications, which can lead to pneumonia, prolonged intubation, and sepsis [13, 14, 15]. However, interestingly our study found that despite these complications, the patients in the dementia group had a lower in-hospital mortality. Additionally, this lower in-hospital mortality occurred despite surgeons operating on sicker patients with more comorbidities throughout the study period. This suggests that surgeons and cardiovascular care teams are carefully selecting which dementia patients are fit for operation. However, patients with dementia only represented less than 0.3% of over four million CVS patients, it is likely that only dementia patients with higher cognitive reserve and less frailty received operations.

We found that dementia patients were more likely to be discharged to skilled nursing facility, which is consistent with other studies of non-cardiovascular surgery [4, 10, 16–21]. While in-hospital mortality is an important metric, discharge disposition is also important when discussing postoperative expectations with the patient and their family. Setting realistic expectations can aid in better preoperative planning for discharge disposition, leading to shorter length of stay and hopefully better outcomes. Even in this highly select group of patients, the higher rate of postoperative complications and discharge to skilled nursing facilities supports the need for cautious preoperative evaluation.

Future clinical implications

Frailty is an umbrella term that describes a syndrome of decreased physical and cognitive reserves, leading to vulnerability and poor homeostasis after a stress [22–24]. Dementia represents an insult to cognitive reserve, therefore making patients more frail [10, 22, 24]. Unfortunately, dementia is not often diagnosed prior to admission [25, 26], especially prior to cardiovascular surgery [26]. Current efforts to identify biomarkers, such as serum proteins t-tau and YKL-40, may help better detect dementia and mild cognitive impairment as an adjunct to clinical assessments [27]. Ultimately it is up to the surgeons and cardiovascular care teams to carefully evaluate patients for preoperative dementia, which we have shown to be a major risk factor in postoperative complications and discharge to nursing facilities after cardiovascular surgery. Once identified, patients with dementia who are deemed fit for surgery should be flagged as high risk and require more attention postoperatively. The role for prehabilitation is also a potential avenue that remains yet to be fully explored in this population [28].

Limitations and strengths

This study has several limitations. It is unclear how many non-dementia patients actually have undiagnosed dementia or how often dementia was not accurately coded. The prevalence of preoperative dementia therefore may be slightly higher than what is reported. However, the large volume of this study likely overcomes this bias. This data also does not reflect recent trends of transcatheter aortic valve replacement or complex percutaneous interventions over open surgical aortic valve replacement, which are also valid options of treatment in select groups of patients. However, the study period does offer real world insight into the effects of dementia on patients undergoing open cardiovascular surgery. Unfortunately, due to the lack of granularity offered by the NIS, it is also difficult to determine why some dementia patients underwent cardiovascular surgery whereas others did not. Additionally, because the NIS is deidentified, it is not possible to determine long term overall survival in these patient populations.

Conclusion

Despite an aging population with increasing prevalence of dementia, this study shows that patients with dementia can undergo cardiovascular surgery with a lower in-hospital mortality, slightly longer length of stay but similar hospitalization costs compared to their non-dementia counterparts. Dementia patients are more likely to experience complications and require discharge to skilled nursing facility. Those who were discharged to skilled nursing facility were more likely to experience neurologic, renal and respiratory complications. Careful patient selection and targeted physical therapy in the postoperative settings may help mitigate some of the dementia associated complications that occur after cardiovascular surgery. Further studies should be performed to identify which dementia patients should be offered cardiovascular surgery.

Electronic Supplementary Material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary Material 1: Preoperative patient demographics of patients undergoing CVS that had dementia, stratified by risk group.Supplemental Table 2: Postoperative outcomes as stratified by risk group.

Abbreviations

- CVS

Cardiovascular surgery

- NIS

National Inpatient Sample

- ECS

Elixhauser comorbidity score

- HCUP

Healthcare Cost Utilization Project

- ICD-9-CM

International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification

- STS

The Society of Thoracic Surgeons

Author contributions

A.T. wrote the main manuscript text and interpreted the findings. T.E. wrote the first draft of the manuscript and helped analyze the data. K.C.D. helped analyze the data and interpret the findings. B.F.R. helped interpret the findings. G.Z. performed the data analysis S.M.K. performed the data analysis. L.G.S. provided mentorship and infrastructure for research. A.M.G. provided mentorship and infrastructure for research. E.G.S. provided mentorship and developed the initial research question.

Funding

None.

Data availability

The National (Nationwide) Inpatient Sample (NIS) is part of a family of databases and software tools developed for the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). The NIS is the largest publicly available all-payer inpatient healthcare database designed to produce U.S. regional and national estimates of inpatient utilization, access, cost, quality, and outcomes. Unweighted, it contains data from around 7 million hospital stays each year. Weighted, it estimates around 35 million hospitalizations nationally. Developed through a Federal-State-Industry partnership sponsored by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), HCUP data inform decision making at the national, State, and community levels. Data analysis is available upon request.

Declarations

Competing interests

Dr. Soltesz discloses a financial relationship with Abiomed, Atricure, and Abbott that are not relevant to this manuscript. The authors have no conflict of interest and will not receive financial support for this manuscript.Dr. GIllinov discloses a financial relationship with Edwards Lifesciences, Medtronic, Abbott, CryoLife, ClearFlow, Johnson and Johnson and Atricure that are not relevant to this manuscript.The authors have no conflict of interest and will not receive financial support for this manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Andrew Tang and Tal Eitan co-authors equally contributed to this manuscript.

References

- 1.Zingone B, Gatti G, Rauber E, et al. Early and late outcomes of cardiac surgery in octogenarians. Ann Thorac Surg. 2009;87(1):71–8. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2008.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim DJ, Park KH, Isamukhamedov SS, Lim C, Shin YC, Kim JS. Clinical results of cardiovascular surgery in the patients older than 75 years. Korean J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2014;47(5):451–7. 10.5090/kjtcs.2014.47.5.451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Prince M, Bryce R, Albanese E, Wimo A, Ribeiro W, Ferri CP. The global prevalence of dementia: A systematic review and metaanalysis. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2013;9(1):63–e752. 10.1016/j.jalz.2012.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Robinson TN, Wu DS, Pointer LF, Dunn CL, Moss M. Preoperative cognitive dysfunction is related to adverse postoperative outcomes in the elderly. J Am Coll Surg. 2012;215(1):12–7. 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2012.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hu C-J, Liao C-C, Chang C-C, Wu C-H, Chen T-L. Postoperative adverse outcomes in surgical patients with dementia: a retrospective cohort study. World J Surg. 2012;36(9):2051–8. 10.1007/s00268-012-1609-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mehaffey JH, Hawkins RB, Tracci MC, et al. Preoperative dementia is associated with increased cost and complications after vascular surgery. J Vasc Surg. 2018;68(4):1203–8. 10.1016/j.jvs.2018.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Partridge JSL, Dhesi JK, Cross JD, et al. The prevalence and impact of undiagnosed cognitive impairment in older vascular surgical patients. J Vasc Surg. 2014;60(4):1002–e10113. 10.1016/j.jvs.2014.04.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kassahun WT. The effects of pre-existing dementia on surgical outcomes in emergent and nonemergent general surgical procedures: Assessing differences in surgical risk with dementia. BMC Geriatr. 2018;18(1):1–9. 10.1186/s12877-018-0844-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris RD, Coffey RM. Cormorbidity Measures for Use with Administrative Data. 1998:8–27. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Lee DH, Buth KJ, Martin B-J, Yip AM, Hirsch GM. Frail patients are at increased risk for mortality and prolonged institutional care after cardiac surgery. Circulation. 2010;121(8):973–8. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.841437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Robinson TN, Raeburn CD, Tran ZV, Angles EM, Brenner LA, Moss M. Postoperative delirium in the elderly: Risk factors and outcomes. Ann Surg. 2009;249(1):173–8. 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31818e4776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.O’Neal JB, Shaw AD. Predicting, preventing, and identifying delirium after cardiac surgery. Perioper Med. 2016;5(1):7. 10.1186/s13741-016-0032-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lin Y, Chen J, Wang Z. Meta-Analysis of Factors Which Influence Delirium Following Cardiac Surgery. J Card Surg. 2012;27(4):481–92. 10.1111/j.1540-8191.2012.01472.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gottesman RF, Grega MA, Bailey MM, et al. Delirium after coronary artery bypass graft surgery and late mortality. Ann Neurol. 2010;67(3):338–44. 10.1002/ana.21899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lingehall HC, Smulter NS, Lindahl E, et al. Preoperative Cognitive Performance and Postoperative Delirium Are Independently Associated With Future Dementia in Older People Who Have Undergone Cardiac Surgery: A Longitudinal Cohort Study. Crit Care Med. 2017;45(8):1295–303. 10.1097/CCM.0000000000002483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shah SK, Jin G, Reich AJ, Gupta A, Belkin M, Weissman JS. Dementia is associated with increased mortality and poor patient-centered outcomes after vascular surgery. J Vasc Surg. 2019;71(5):1685–e16902. 10.1016/j.jvs.2019.07.087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fox C, Smith T, Maidment I, et al. The importance of detecting and managing comorbidities in people with dementia? Age Ageing. 2014;43(6):741–3. 10.1093/ageing/afu101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhu CW, Cosentino S, Ornstein KA, Gu Y, Andrews H, Stern Y. Interactive Effects of Dementia Severity and Comorbidities on Medicare Expenditures. J Alzheimer’s Dis. 2017;57:305–15. 10.3233/JAD-161077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Doraiswamy PM, Leon J, Cummings JL, Marin D, Neumann PJ. Prevalence and impact of medical comorbidity in Alzheimer’s disease. J Gerontol Biol Sci Med Sci. 2002;57(3):M173–7. 10.1093/gerona/57.3.m173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Phelan EA, Borson S, Grothaus L, Balch S, Larson EB. Association of incident dementia with hospitalizations. JAMA. 2012;307(2):165–72. 10.1001/jama.2011.1964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhao Y, Kuo TC, Weir S, Kramer MS, Ash AS. Healthcare costs and utilization for Medicare beneficiaries with Alzheimer’s. BMC Health Serv Res. 2008;8:1–8. 10.1186/1472-6963-8-108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boyle PA, Buchman AS, Wilson RS, Leurgans SE, Bennett DA. Physical frailty is associated with incident mild cognitive impairment in community-based older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58(2):248–55. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02671.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rodrigues MK, Marques A, Lobo DML, Umeda IIK, Oliveira MF. Pré-fragilidade aumenta o risco de eventos adversos em idosos submetidos à cirurgia cardiovascular. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2017;109(4):299–306. 10.5935/abc.20170131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Clegg A, Young J, Iliffe S, Rikkert MO, Rockwood K. Frailty in elderly people. Lancet (London England). 2013;381(9868):752–62. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)62167-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Austin CA, O’Gorman T, Stern E, et al. Association between Postoperative Delirium and Long-term Cognitive Function after Major Nonemergent Surgery. JAMA Surg. 2019;154(4):328–34. 10.1001/jamasurg.2018.5093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mangusan RF, Hooper V, Denslow SA, Travis L. Outcomes Associated With Postoperative Delirium After Cardiac Surgery. Am J Crit Care. 2015;24(2):156–63. 10.4037/ajcc2015137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wilczyńska K, Waszkiewicz N. Diagnostic Utility of Selected Serum Dementia Biomarkers: Amyloid β-40, Amyloid β-42, Tau Protein, and YKL-40: A Review. J Clin Med. 2020;9(11). 10.3390/jcm9113452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Sepehri A, Beggs T, Hassan A, et al. The impact of frailty on outcomes after cardiac surgery: A systematic review. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2014;148(6):3110–7. 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2014.07.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Material 1: Preoperative patient demographics of patients undergoing CVS that had dementia, stratified by risk group.Supplemental Table 2: Postoperative outcomes as stratified by risk group.

Data Availability Statement

The National (Nationwide) Inpatient Sample (NIS) is part of a family of databases and software tools developed for the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). The NIS is the largest publicly available all-payer inpatient healthcare database designed to produce U.S. regional and national estimates of inpatient utilization, access, cost, quality, and outcomes. Unweighted, it contains data from around 7 million hospital stays each year. Weighted, it estimates around 35 million hospitalizations nationally. Developed through a Federal-State-Industry partnership sponsored by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), HCUP data inform decision making at the national, State, and community levels. Data analysis is available upon request.