Abstract

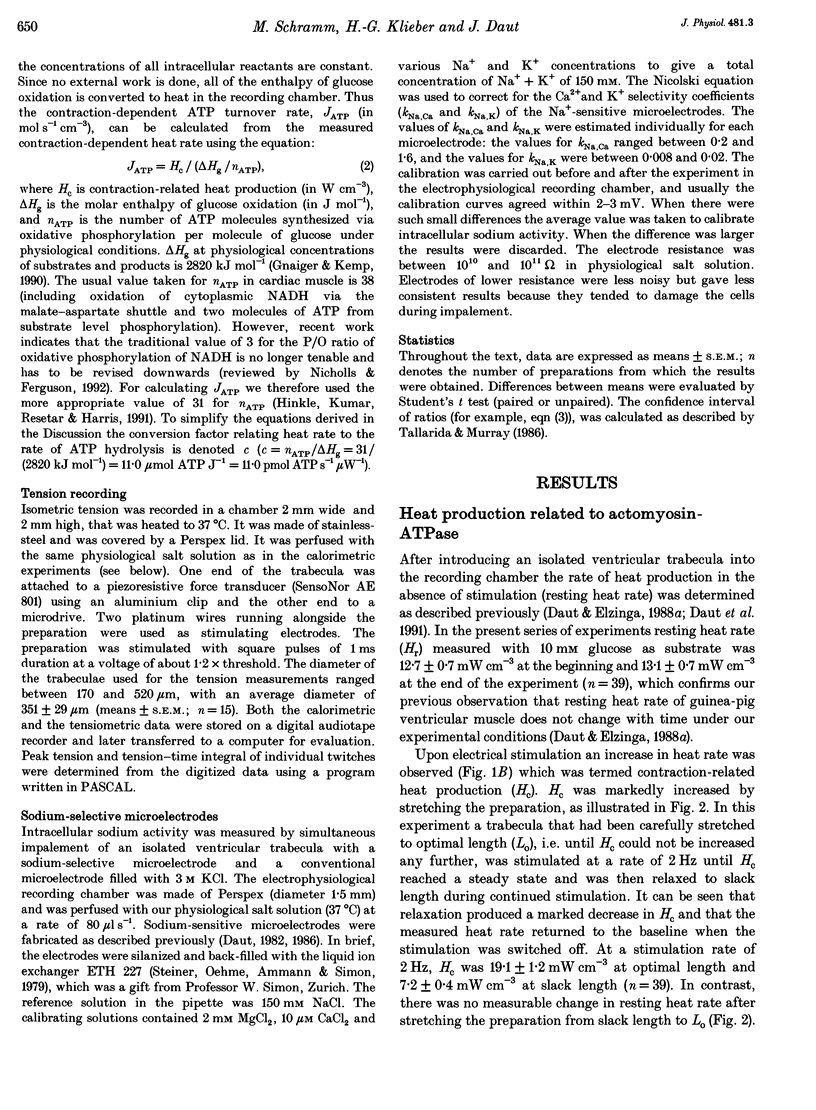

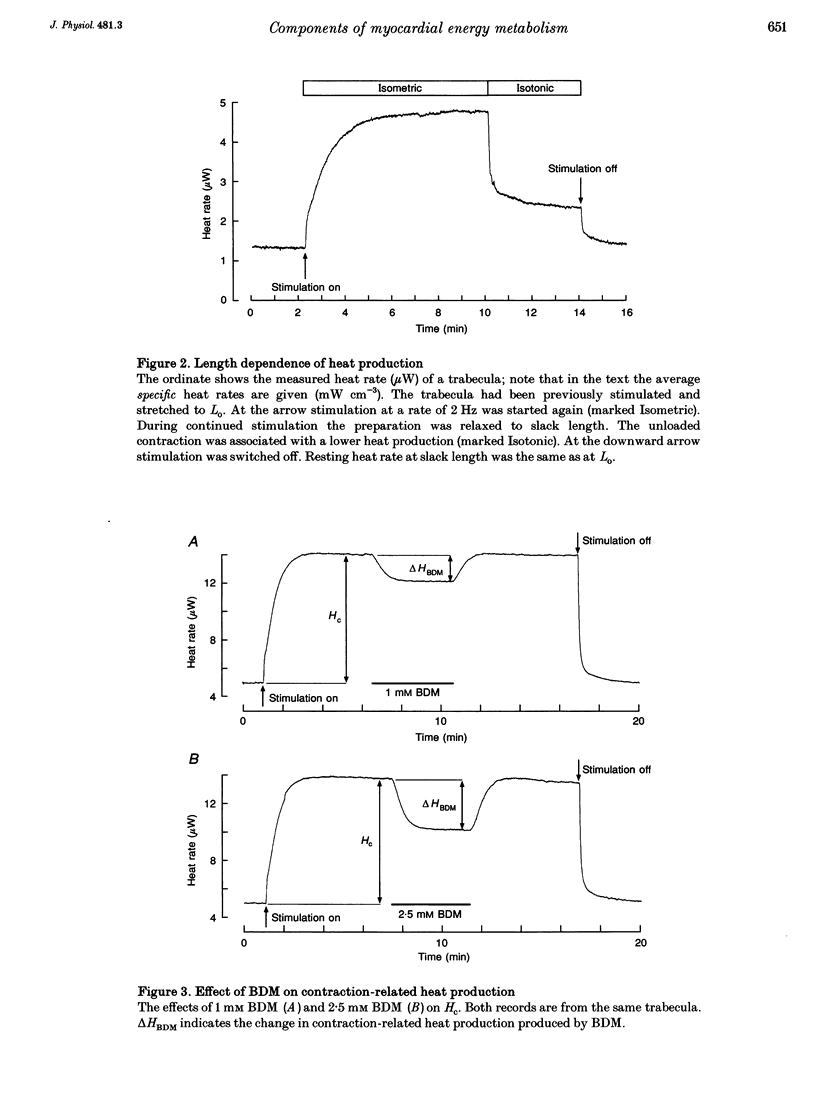

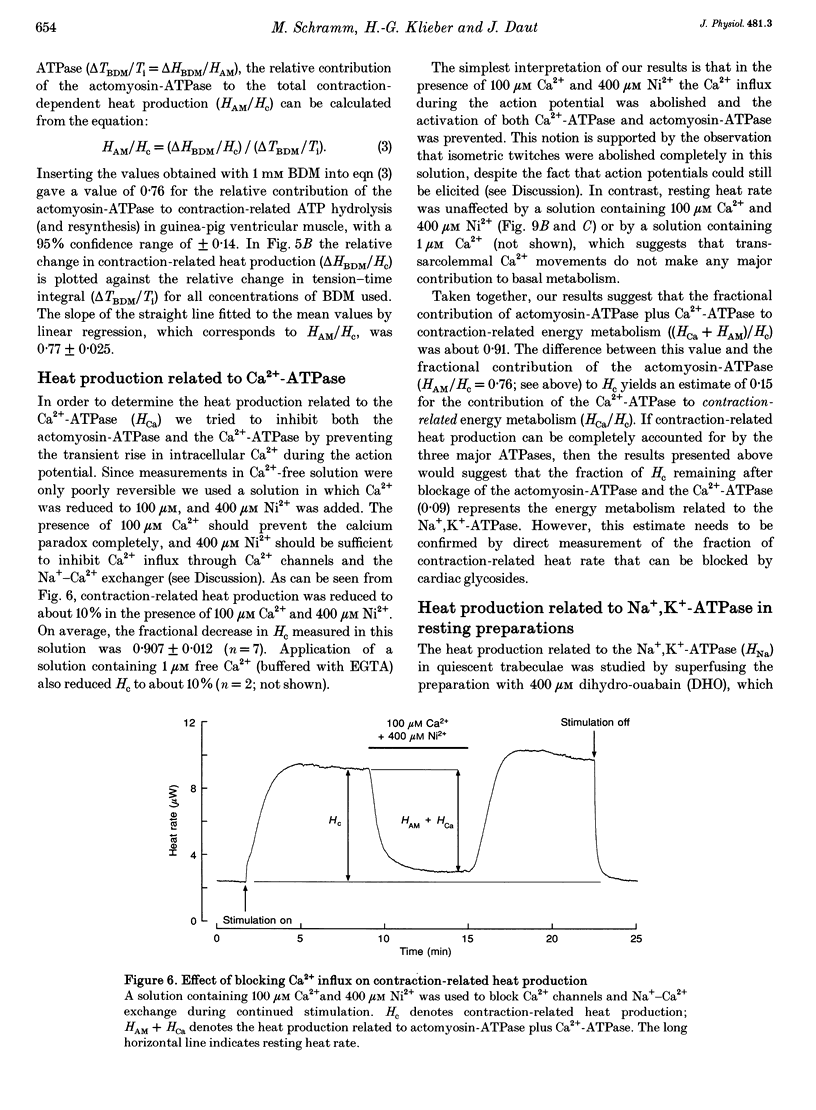

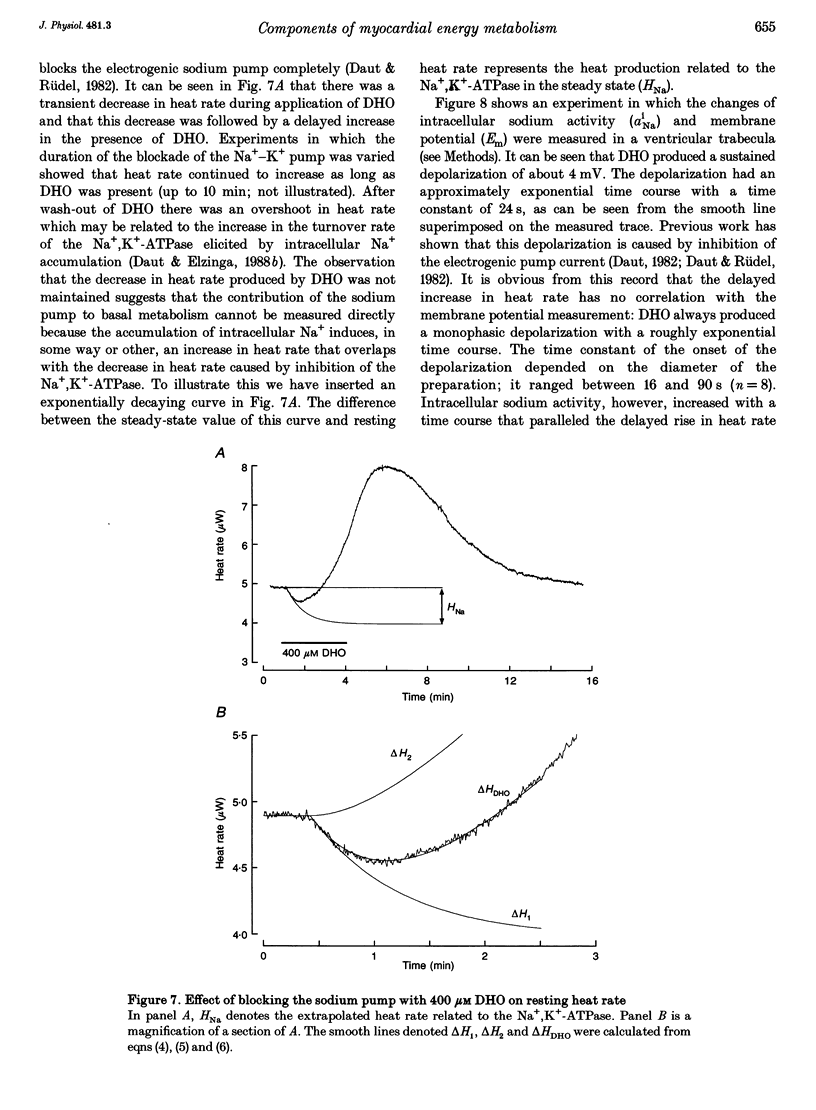

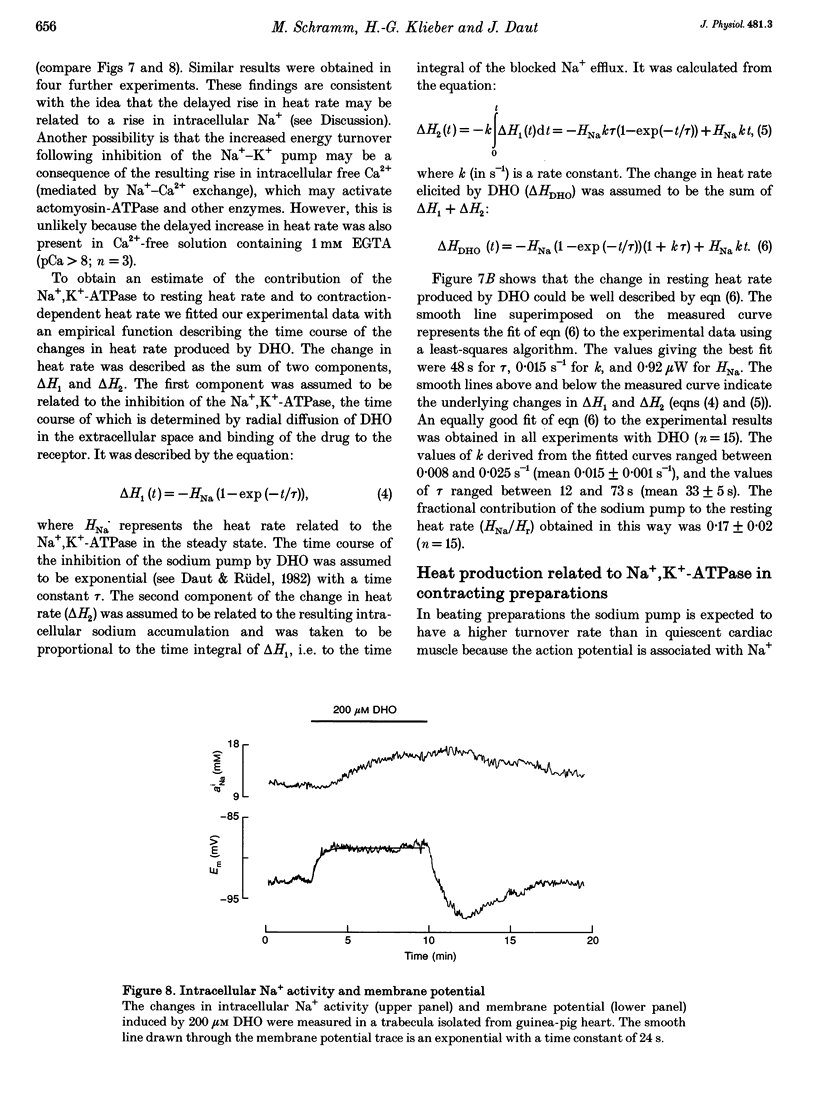

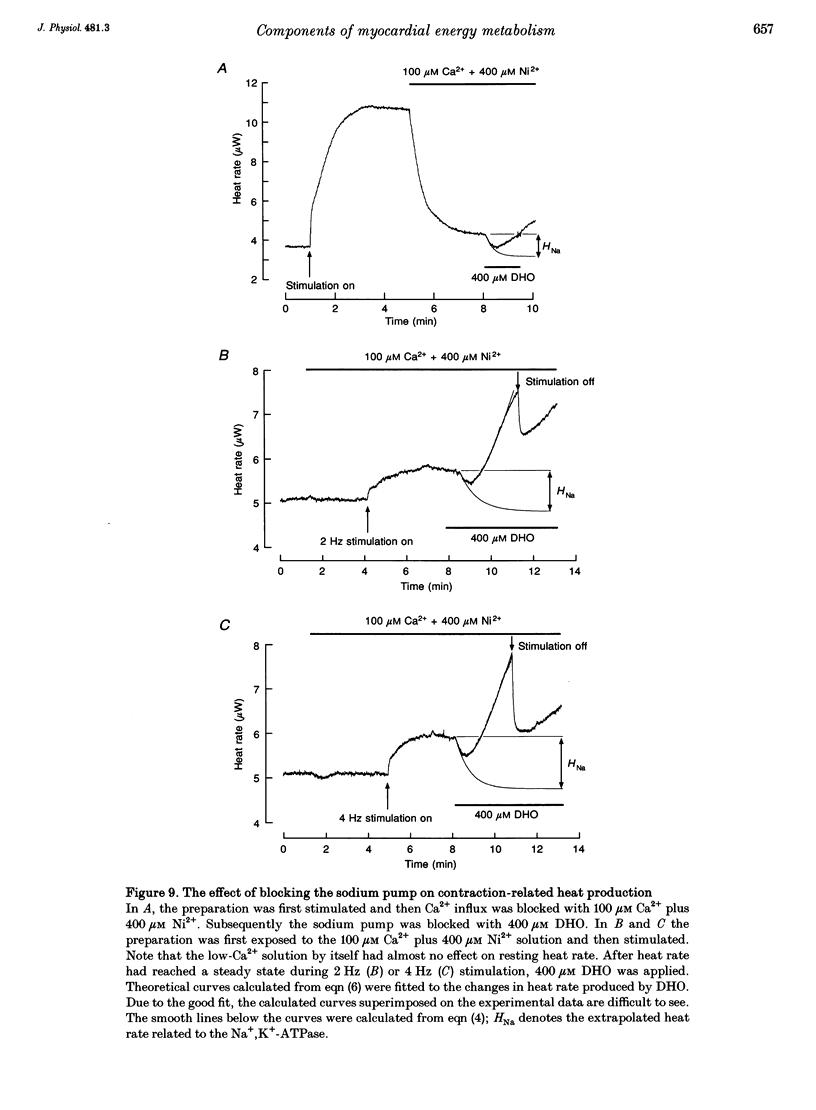

1. The rate of heat production (heat rate) and isometric twitch tension of ventricular trabeculae isolated from guinea-pig heart were measured at 37 degrees C in order to determine the relative contributions of actomyosin-ATPase, Ca(2+)-ATPase and Na+,K(+)-ATPase to myocardial energy metabolism. 2. The increase in heat rate recorded during isometric contractions at optimal length (contraction-related heat production) was 19.1 +/- 1.2 mW cm-3 at a stimulation rate of 2 Hz. The tension-time integral of individual contractions measured under the same conditions was 147 +/- 15 mM s cm-2. 3. The heat production of the actomyosin-ATPase was determined by inhibiting the contractile proteins with 2,3-butanedione monoxime (BDM). Contraction-related heat production was reduced by 0.219 +/- 0.010 and the isometric tension-time integral was reduced by 0.288 +/- 0.016 in the presence of 1 mM BDM. From these data an estimate of 0.76 for the relative contribution of the actomyosin-ATPase to contraction-related heat production was derived. 4. The heat production related to actomyosin-ATPase plus Ca(2+)-ATPase was studied by blocking Ca2+ influx into the myocardial cells with a solution containing 100 microM Ca2+ and 400 microM Ni2+. In this solution contraction-related heat production was reduced by 0.907 +/- 0.012. Comparison of this value with the component attributable to the actomyosin-ATPase yields an estimate of 0.15 for the relative contribution of the Ca(2+)-ATPase to contraction related heat production. 5. The heat production related to the Na+,K(+)-ATPase in resting preparations was studied by blocking the sodium pump with 400 microM dihydro-ouabain (DHO). DHO produced a transient decrease in heat rate lasting 1-2 min, which was followed by a secondary increase. From the heat transient produced by DHO the heat rate related to the Na+,K(+)-ATPase in the steady state was extrapolated. The relative contribution of the sodium pump to resting heat production was estimated to be 0.17. 6. The heat production related to the Na+,K(+)-ATPase in contracting preparations was studied by first blocking Ca2+ influx with 100 microM Ca2+ and 400 microM Ni2+, and then inhibiting the sodium pump with 400 microM dihydro-ouabain (DHO). The relative contribution of the sodium pump to contraction-related heat production extrapolated from these data was 0.10, which agreed well with the fraction of contraction-related heat production persisting after blockage of actomyosin-ATPase and Ca(2+)-ATPase (0.09).(ABSTRACT TRUNCATED AT 400 WORDS)

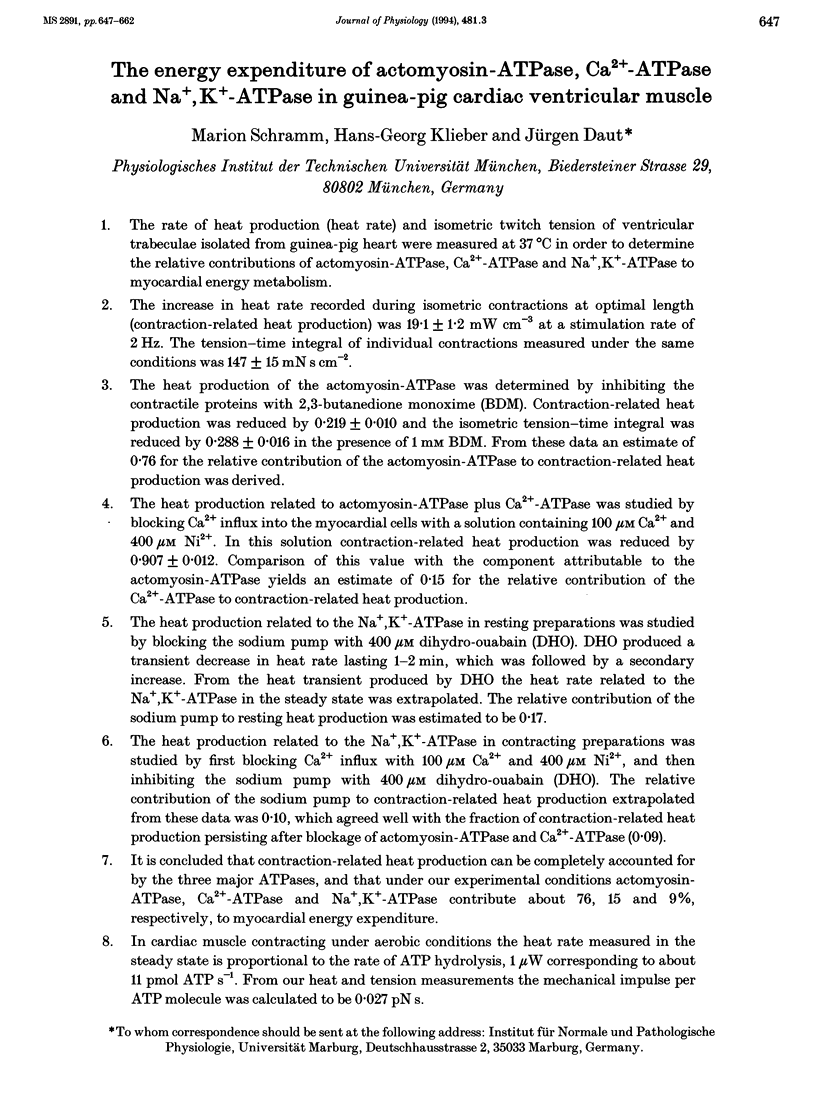

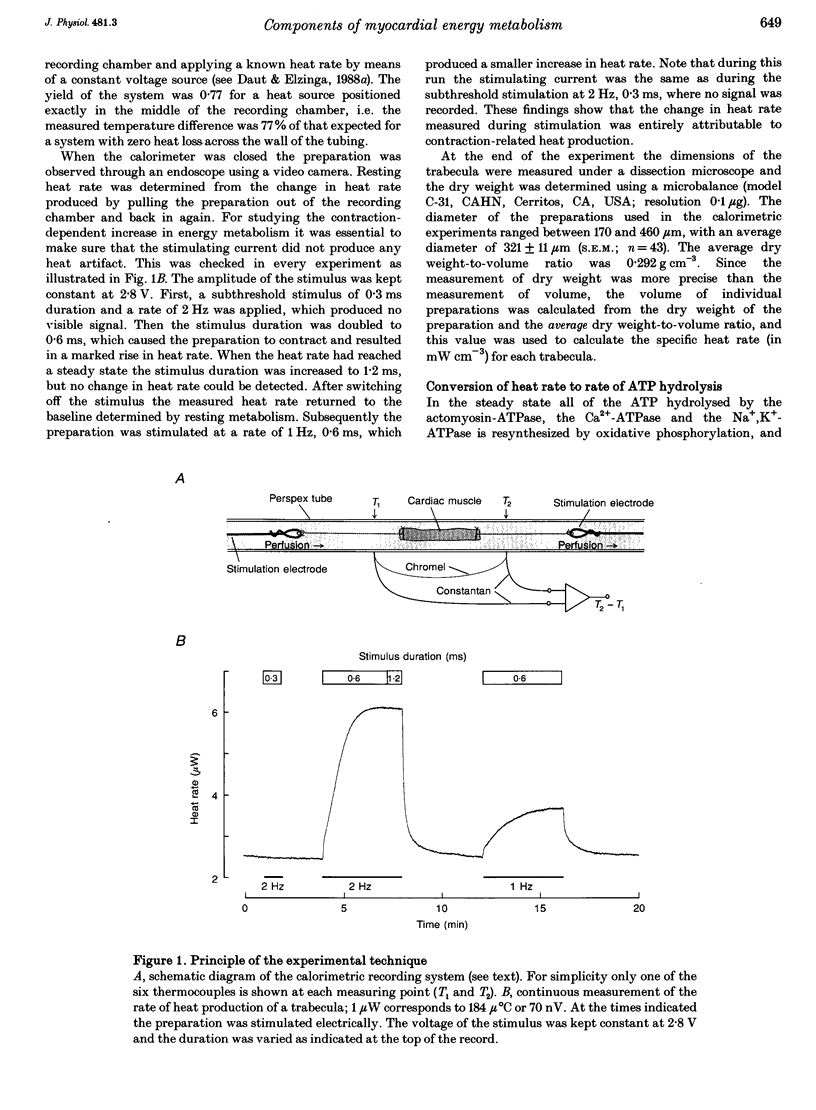

Full text

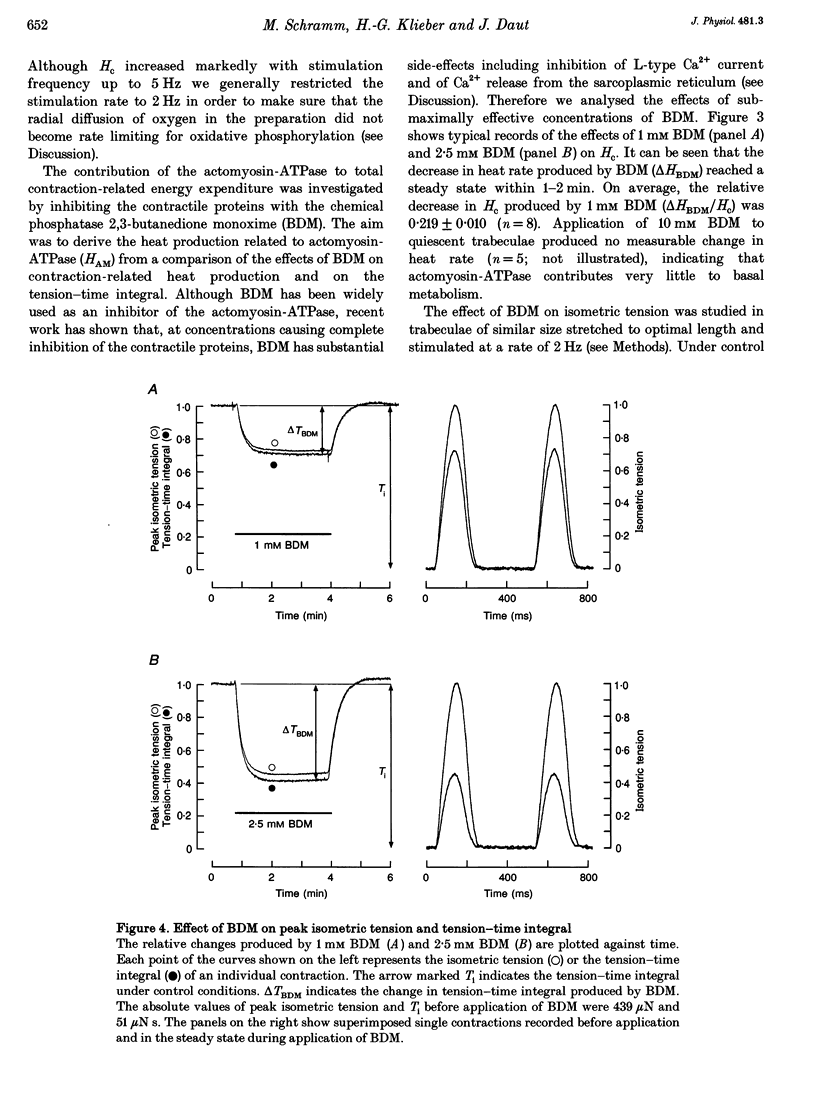

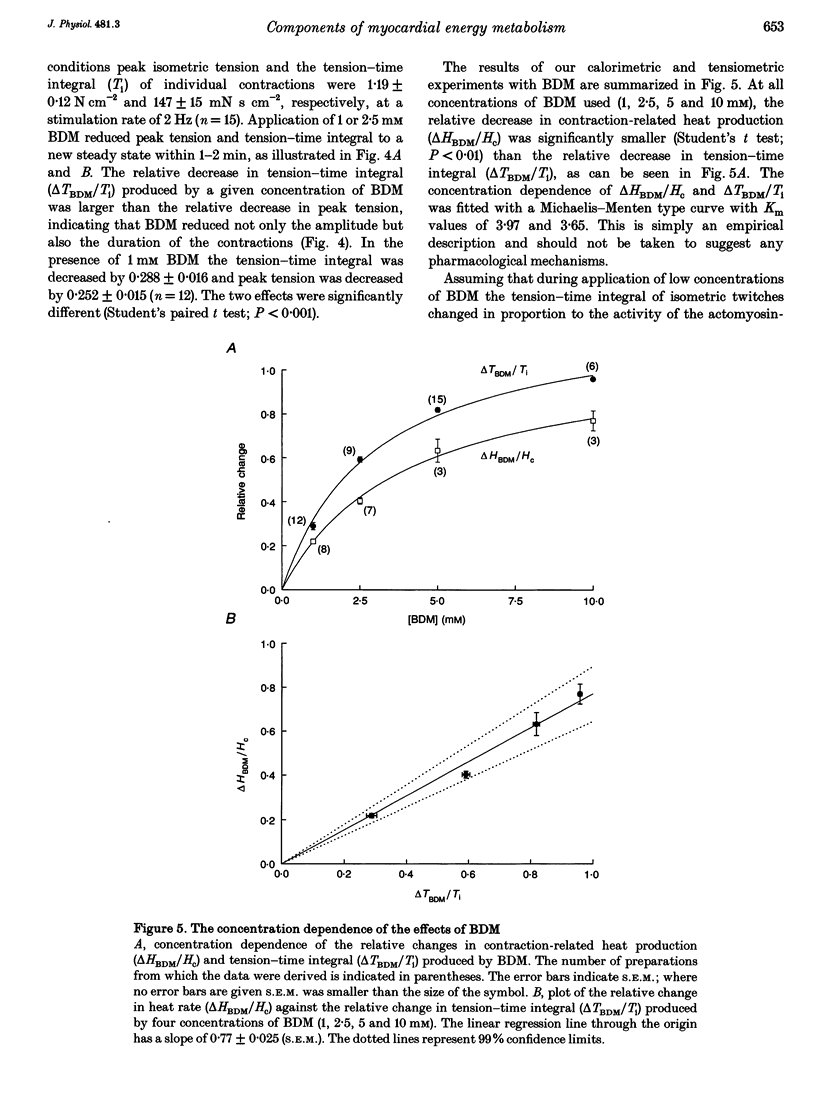

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Alpert N. R., Blanchard E. M., Mulieri L. A. Tension-independent heat in rabbit papillary muscle. J Physiol. 1989 Jul;414:433–453. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1989.sp017697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardenheuer H., Schrader J. Relationship between myocardial oxygen consumption, coronary flow, and adenosine release in an improved isolated working heart preparation of guinea pigs. Circ Res. 1983 Mar;52(3):263–271. doi: 10.1161/01.res.52.3.263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beuckelmann D. J., Wier W. G. Sodium-calcium exchange in guinea-pig cardiac cells: exchange current and changes in intracellular Ca2+. J Physiol. 1989 Jul;414:499–520. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1989.sp017700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard E. M., Smith G. L., Allen D. G., Alpert N. R. The effects of 2,3-butanedione monoxime on initial heat, tension, and aequorin light output of ferret papillary muscles. Pflugers Arch. 1990 Apr;416(1-2):219–221. doi: 10.1007/BF00370248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carafoli E. The homeostasis of calcium in heart cells. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1985 Mar;17(3):203–212. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2828(85)80003-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmeliet E., Morad M., Van der Heyden G., Vereecke J. Electrophysiological effects of tetracaine in single guinea-pig ventricular myocytes. J Physiol. 1986 Jul;376:143–161. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1986.sp016146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman R. A. The effect of oximes on the dihydropyridine-sensitive Ca current of isolated guinea-pig ventricular myocytes. Pflugers Arch. 1993 Jan;422(4):325–331. doi: 10.1007/BF00374287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinet A., Clausen T., Girardier L. Microcalorimetric determination of energy expenditure due to active sodium-potassium transport in the soleus muscle and brown adipose tissue of the rat. J Physiol. 1977 Feb;265(1):43–61. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1977.sp011704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper G., 4th Myocardial energetics during isometric twitch contractions of cat papillary muscle. Am J Physiol. 1979 Feb;236(2):H244–H253. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1979.236.2.H244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coulombe A., Lefevre I. A., Deroubaix E., Thuringer D., Coraboeuf E. Effect of 2,3-butanedione 2-monoxime on slow inward and transient outward currents in rat ventricular myocytes. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1990 Aug;22(8):921–932. doi: 10.1016/0022-2828(90)90123-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daut J., Elzinga G. Heat production of quiescent ventricular trabeculae isolated from guinea-pig heart. J Physiol. 1988 Apr;398:259–275. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1988.sp017041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daut J., Elzinga G. Substrate dependence of energy metabolism in isolated guinea-pig cardiac muscle: a microcalorimetric study. J Physiol. 1989 Jun;413:379–397. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1989.sp017659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daut J., Rüdel R. The electrogenic sodium pump in guinea-pig ventricular muscle: inhibition of pump current by cardiac glycosides. J Physiol. 1982 Sep;330:243–264. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1982.sp014339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daut J. The role of intracellular sodium ions in the regulation of cardiac contractility. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1982 Mar;14(3):189–192. doi: 10.1016/0022-2828(82)90119-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabiato A. Calcium-induced release of calcium from the cardiac sarcoplasmic reticulum. Am J Physiol. 1983 Jul;245(1):C1–14. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1983.245.1.C1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs C. L., Kotsanas G. Factors regulating basal metabolism of the isolated perfused rabbit heart. Am J Physiol. 1986 Jun;250(6 Pt 2):H998–1007. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1986.250.6.H998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs C. L., Loiselle D. S., Wendt I. R. Activation heat in rabbit cardiac muscle. J Physiol. 1988 Jan;395:115–130. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1988.sp016911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gnaiger E., Kemp R. B. Anaerobic metabolism in aerobic mammalian cells: information from the ratio of calorimetric heat flux and respirometric oxygen flux. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1990 Apr 26;1016(3):328–332. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(90)90164-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goto Y., Slinker B. K., LeWinter M. M. Similar normalized Emax and O2 consumption-pressure-volume area relation in rabbit and dog. Am J Physiol. 1988 Aug;255(2 Pt 2):H366–H374. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1988.255.2.H366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasenfuss G., Mulieri L. A., Blanchard E. M., Holubarsch C., Leavitt B. J., Ittleman F., Alpert N. R. Energetics of isometric force development in control and volume-overload human myocardium. Comparison with animal species. Circ Res. 1991 Mar;68(3):836–846. doi: 10.1161/01.res.68.3.836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinkle P. C., Kumar M. A., Resetar A., Harris D. L. Mechanistic stoichiometry of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation. Biochemistry. 1991 Apr 9;30(14):3576–3582. doi: 10.1021/bi00228a031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishijima A., Doi T., Sakurada K., Yanagida T. Sub-piconewton force fluctuations of actomyosin in vitro. Nature. 1991 Jul 25;352(6333):301–306. doi: 10.1038/352301a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohlhardt M., Minich Z., Haap K. Analysis of the inhibitory effect of Ni ions on slow inward current in mammalian ventricular myocardium. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1979 Dec;11(12):1227–1243. doi: 10.1016/0022-2828(79)90003-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langer G. A. Sodium-calcium exchange in the heart. Annu Rev Physiol. 1982;44:435–449. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.44.030182.002251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loiselle D. S., Gibbs C. L. Species differences in cardiac energetics. Am J Physiol. 1979 Jul;237(1):H90–H98. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1979.237.1.H90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neely J. R., Rovetto M. J., Whitmer J. T., Morgan H. E. Effects of ischemia on function and metabolism of the isolated working rat heart. Am J Physiol. 1973 Sep;225(3):651–658. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1973.225.3.651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuss H. B., Houser S. R. Sodium-calcium exchange-mediated contractions in feline ventricular myocytes. Am J Physiol. 1992 Oct;263(4 Pt 2):H1161–H1169. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1992.263.4.H1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perreault C. L., Mulieri L. A., Alpert N. R., Ransil B. J., Allen P. D., Morgan J. P. Cellular basis of negative inotropic effect of 2,3-butanedione monoxime in human myocardium. Am J Physiol. 1992 Aug;263(2 Pt 2):H503–H510. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1992.263.2.H503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigo G. C., Chapman R. A. The calcium paradox in isolated guinea-pig ventricular myocytes: effects of membrane potential and intracellular sodium. J Physiol. 1991 Mar;434:627–645. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1991.sp018490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suga H. Total mechanical energy of a ventricle model and cardiac oxygen consumption. Am J Physiol. 1979 Mar;236(3):H498–H505. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1979.236.3.H498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swain J. L., Sabina R. L., McHale P. A., Greenfield J. C., Jr, Holmes E. W. Prolonged myocardial nucleotide depletion after brief ischemia in the open-chest dog. Am J Physiol. 1982 May;242(5):H818–H826. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1982.242.5.H818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uyeda T. Q., Kron S. J., Spudich J. A. Myosin step size. Estimation from slow sliding movement of actin over low densities of heavy meromyosin. J Mol Biol. 1990 Aug 5;214(3):699–710. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(90)90287-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ter Keurs H. E., Rijnsburger W. H., van Heuningen R., Nagelsmit M. J. Tension development and sarcomere length in rat cardiac trabeculae. Evidence of length-dependent activation. Circ Res. 1980 May;46(5):703–714. doi: 10.1161/01.res.46.5.703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]