Abstract

Systems metabolic engineering, which recently emerged as metabolic engineering integrated with systems biology, synthetic biology, and evolutionary engineering, allows engineering of microorganisms on a systemic level for the production of valuable chemicals far beyond its native capabilities. Here, we review the strategies for systems metabolic engineering and particularly its applications in Escherichia coli. First, we cover the various tools developed for genetic manipulation in E. coli to increase the production titers of desired chemicals. Next, we detail the strategies for systems metabolic engineering in E. coli, covering the engineering of the native metabolism, the expansion of metabolism with synthetic pathways, and the process engineering aspects undertaken to achieve higher production titers of desired chemicals. Finally, we examine a couple of notable products as case studies produced in E. coli strains developed by systems metabolic engineering. The large portfolio of chemical products successfully produced by engineered E. coli listed here demonstrates the sheer capacity of what can be envisioned and achieved with respect to microbial production of chemicals. Systems metabolic engineering is no longer in its infancy; it is now widely employed and is also positioned to further embrace next-generation interdisciplinary principles and innovation for its upgrade. Systems metabolic engineering will play increasingly important roles in developing industrial strains including E. coli that are capable of efficiently producing natural and nonnatural chemicals and materials from renewable nonfood biomass.

INTRODUCTION

Escherichia coli has become not only one of the most characterized and understood organisms, but also the most sought organism for genetic manipulation since the success of the first ever genetically modified E. coli in 1973 that pioneered the field of genetic engineering (1, 2). As a Gram-negative facultative anaerobe, E. coli is one of the first colonizers in neonatal intestines and normally dwells in gastrointestinal microflora of many animals, including humans (3). Although these enteric bacteria might develop virulence through horizontal gene transfer (4), genetic manipulation in laboratory settings is simple and quick, rendering the strain attractive for research. Following the initial sequencing of the genome with 4.6 Mb size and about 4,300 genes annotated (5), the pangenome with a reservoir of almost 13,000 genes has been recently characterized (6). With the genome sequence readily available, the massive influx of omics information and the development of various engineering tools enabled our attempts to understand E. coli at the systems level.

Systems metabolic engineering emerged as the fields of metabolic engineering and biotechnology transitioned toward understanding the biology of organisms at the systems level. In 1991, metabolic engineering was first described and aimed to be a field concerning the application of recombinant DNA methods to develop high-performance strains for the production of useful chemicals and recombinant proteins (7). In the same year, the historical issuance of U.S. patent 5,000,000 appeared, granting rights to converting hexose or pentose to ethanol with a genetically modified E. coli expressing Zymomonas mobilis pyruvate decarboxylase and alcohol dehydrogenase (8). Together with the ever-growing omics data, rapidly advancing tools, and novel strategies, it is now possible to rationally design high-performance E. coli strains for producing not only ethanol but also higher alcohols (9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14), hydrocarbons (15, 16, 17, 18), amino acids (19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26), various polymer precursors (27, 28), recombinant proteins (29, 30), and plastics (31, 32, 33). Some of these production processes have achieved industrial-level production standards (greater than 100 g/liter production titer and 3 to 4 g/L/h productivity) and have been commercialized to meet the global market demands.

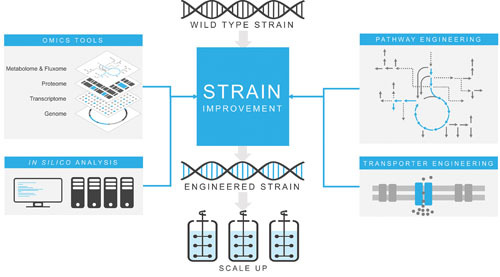

Systems metabolic engineering continues to expand at an unparalleled pace with the rapid development of state-of-the-art genetic manipulation strategies, high-throughput screening tools, computational analysis methods, cultivation strategies, and downstream processes (Fig. 1). In this contribution, we aim to outline both the traditional and the most recently developed genetic manipulation tools including zinc finger nucleases (ZFN), transcription activator-like effector nucleases (TALEN), multiplex automated genome engineering (MAGE), conjugative assembly genome engineering (CAGE), clustered regularly interspaced palindromic repeat (CRISPR)/CRISPR-associated protein 9 (Cas9) systems, and global transcription machinery engineering (gTME), in light of systems metabolic engineering. We also cover strategies for systems metabolic engineering and approaches to arising issues including enhancement of biosynthetic pathway, improving carbon flux, creating novel pathways, transporter engineering, reducing acetic acid formation during high-cell-density cultivation (HCDC), and the use of plasmids without antibiotics. Additionally, the concerted application of these strategies for industrial-level production of chemical production is detailed. While we confine our discussion to focus on the systems metabolic engineering of E. coli, readers are encouraged to explore various publications on the successful applications of the strategies developed for other species as well (34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41).

Figure 1.

Overview of systems metabolic engineering. Systems metabolic engineering is the recursive process of improving a candidate strain via pathway engineering, transporter engineering, omics tools, and in silico analysis in an effort to increase the production of desired chemicals to industrial scales.

TOOLS FOR SYSTEMS METABOLIC ENGINEERING OF E. COLI

Here, we cover the various tools developed for genetic and genomic manipulations in E. coli. Some of these tools were not initially developed specifically for the purposes of systems metabolic engineering, but we listed them nonetheless, because these tools have become an integral part of strain development and, thus, a part of systems metabolic engineering. It must also be noted that some of these tools are very specific to E. coli, and applications of such tools on other organisms might not have been studied.

Recombineering: Recombination-Mediated Genetic Engineering

While the traditional cloning methodology, comprising digesting vectors with restriction enzymes and subsequent joining of the ends by ligation in vitro, is the starting point for almost all molecular biology experiments, it is not suitable for complex procedures (e.g., large-sized DNA manipulation). In recombination-mediated genetic engineering or “recombineering,” components derived from phages, λ and P1, have not only been the center of focus but also the most commonly used tools. Recombineering method has been used for engineering plasmids (42), genomic DNAs, and bacterial artificial chromosomes (BACs) (43, 44, 45), effectively using either single-stranded DNA (ssDNA)- (46, 47, 48, 49) or double-stranded DNA (dsDNA)-based techniques (50, 51, 52). In a metabolic engineering context, this process is used to alter expression levels of native proteins for flux optimization (53). In general, such methods rely on E. coli native recombination machinery originally used in DNA repair mechanisms.

The homologous recombination mechanism of E. coli that has most commonly been utilized in recombineering is the recABCD pathway. RecA is involved not only in homologous recombination but also in DNA repair and exhibits multiple functions, including DNA binding, ATP binding, DNA hydrolysis, protein degradation, and filament formation (54). RecBCD, also known as ExoV, exhibits helicase and exonuclease activities (55) and facilitates initial steps in DNA repair mechanism (for RecBCD reviews, see references 56, 57, 58). In E. coli, RecBCD degrades along linear DNA until it encounters a cis-element, chi (crossover hotspot instigator or χ) sequence, which facilitates the subsequent steps in recombination events (57, 59, 60). Linear dsDNA-based recombineering had been discouraged in the past, in particular because of E. coli RecBCD mechanisms, although linear dsDNA transformation in yeast had been common (61). While successful transformation with linear dsDNA in the recBC disrupted strain marks one of the first recombineering cases in historical perspective (62, 63), it required additional disruption of sbcB and sbcC because they often impede the use of linear dsDNA for homologous recombination template in the absence of functional RecBCD (62). While the strict requirement for recBC deficiency for linearized dsDNA transformation can be evaded by flanking linear dsDNA with the chi sequence, the chi-mediated recombineering suffers from low efficiency and positive-negative selection requirement (64). Use of λ recombination system for exonuclease deficiency requirement is one way to avoid this issue.

The λ recombination system designated “Red” consists of two proteins, the exonuclease (simply exo or sometimes α) and the bet protein (simply β) (65). Red is assisted by a third λ protein, gam (or γ), which increases exo and β activity on linear dsDNA by inhibiting E. coli RecBCD exonucleases (50, 55, 66). Since the presence of RecBCD no longer hinders stability of dsDNA, Red is universally applicable and greatly improves the linear dsDNA transformation efficiency as well as recombination (50). This system is often used in conjunction with site-specific recombination systems such as Cre/lox and Flp/FRT system.

Initially discovered in early 1980s, the Cre/lox system exploits the phage P1 infection mechanism in E. coli (67, 68). As a member of the λ recombinase family with a relatively small size (38 kDa), Cre (short for cause of recombination) protein from P1 recognizes and integrates the loxP (short for locus of crossover (x) in P1) sequence into a specific location of bacterial chromosome (loxB) in a Holliday junction-mediated event. Initially discovered from yeast plasmid “2μ circle” (69), the Flp/FRT (Flp recognition target) system is analogous to Cre/lox and uses two inverted repeats (70). While recognition sites in both systems are 34 base pairs (bp), Cre is more thermostable than Flp (71) and exhibits higher DNA binding affinity cooperativity (72). For engineering multiple genes, mutant lox sequences such as lox71, lox66, and lox2272 are also available for preventing further recombination events (73, 74). In conjunction with such site-specific recombination mechanisms in the above-mentioned homologous recombination, more efficient genetic engineering methods are being continuously developed.

The λ Red system combined with site-specific recombination was successful by the establishment of a one-step inactivation method for chromosomal deletion of E. coli genes (52). Widely accepted and used in systems metabolic engineering, this method employs the PCR-generated linear DNA including a drug selectable marker and homology extensions at both ends for recombination that are additionally flanked by lox (or FRT). Plasmid-based introduction of λ Red genes allows linear dsDNA integration into genome (52) followed by site-specific recombination for “pop out” of the selectable marker, successfully deleting the target gene (75, 76). Time taken for engineering of multiple genes has been improved recently using an integrated system for both recombination mechanisms (77). Because the two recombination systems were both integrated into one helper plasmid, there is no need for plasmid curing or repeated transformation for sequential genome-editing steps, thus greatly reducing the time taken for sequential recombinations (77). While this method boasts seamless efficiency and speed, the system leaves a scar in the edited genome. One way to overcome this challenge is to use a dual-selection system for the removal of the selection marker: a widely used dual-selection system involves the use of a gene named sacB.

Isolated from Bacillus subtilis, the sacB gene encoding levansucrase is used as a negative selection marker for an insertion sequence (78, 79). The sacB gene is usually used in conjunction with an antibiotic resistance gene for a two-step selection process to validate a homologous recombination of the host genomic DNA with the sequence of interest (80, 81). A plasmid harboring antibiotic resistance, sacB, and engineered sequence is introduced into a host cell, where the first level of screening is done on a medium plate containing the respective antibiotic to ensure proper genome integration of the plasmid. Once transformation of the plasmid is confirmed, the consequent host cells are then introduced into a sucrose-rich medium for a second level of screening; levansucrase converts sucrose into lethal levan. Only the host cells with successful second recombination will survive, thus validating the change in the genomic DNA of the host; some population with the second cross-over occurring at the same side as the first cross-over will revert to their original state and fail to survive. Survival of cells with spontaneous mutation in sacB coding region is the weakness of this system.

Meganucleases

Meganucleases, also known as homing endonucleases, are deoxyribonucleases that cleave recognition sites that are 12 to 40 bp long. Based on sequences and structural motifs, they are categorized into five classes: LAGLIDADG, GIY-YIG, HNH, His-Cys box, and PD-(D/E)XK; LAGLIDADG especially is the largest family that is found in all kingdoms of life (82). Meganucleases are easily distinguished from other restriction enzymes by special prefixes in their names: I- for those found in introns (83, 84, 85), PI- for those found in inteins (protein inserts) (86), F- for viral genes and those freestanding outside introns and inteins (87), and E- or H- for engineered or hybrid meganucleases (88). The first meganuclease identified is I-SceI, found in the mitochondria of baker’s yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae (89). Subsequently, several other meganucleases, including I-CreI from the chloroplasts of a green alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii (84) and I-DmoI from an archaeon Desulfurococcus mobilis (85), were identified and characterized.

The relatively long nature of meganuclease recognition sites explains their extremely low appearance frequency, which has inspired scientists to use them as a site-specific genome engineering or gene therapy tool. Mathematically, one recognition site 40 bp in length would only appear once in 1.2 × 1024 bp. In reality, one or more recognition sites occur in each genome of certain organisms. However, the scarcity of recognition sites in genomes also makes the use of meganucleases for direct engineering difficult because of the lack of variety and options for suitable use in a given genomic locus of interest. Two approaches have been taken to overcome this obstacle. In one approach, target DNA specificities were altered by either creating mutant meganucleases (90, 91) or chimeras using different parental nucleases (88, 92). In another approach, a meganuclease recognition sequence is inserted into the genomic locus of interest (89, 93). In either case, DNA cleavage followed by homologous recombinations at the target loci can be induced for desired chromosomal engineering (89, 92, 93). Alternatively, the scarcity of recognition sites in the genome that may pose a problem can be circumvented with the following novel strategy. When the organism of interest lacks the recognition sequence in the genome, the sequence can be introduced on a plasmid for in vivo cleavage, leading either to the loss of plasmids (94) or integrations of the linearized plasmids into the genome (94, 95).

Zinc Finger Nucleases (ZFNs)

As described in “Meganucleases” above, finding or synthesizing endonucleases that target and cleave desired sequences in a very specific manner has been a big concern in the field of genome engineering. Often described as “programmable nucleases,” such endonucleases have been designed and manufactured since the first report on the creation of a fusion endonuclease, named “zinc finger nucleases” (ZFNs) (Fig. 2). In a 1996 study, zinc finger domains were combined with fragments of a restriction endonuclease, producing the first ZFN (96). In this first article on ZFN, the authors employed zinc finger proteins CP-QDR and Sp1-QNR, which consist of three domains of Cys2His2 zinc fingers and thus bind to 9-bp target sequences (96). Moreover, removing the N terminus of FokI restriction endonuclease, which is responsible for the DNA binding activity (97), C-terminal 196 amino acids of FokI, which has the nonspecific DNA cleavage activity (98), was fused to the C terminus of each zinc finger protein (96). Maximally utilizing the requirement of FokI dimerization to work as a DNA cleaving unit (99), a genomic locus of interest can be more specifically targeted by using two ZFNs, which bind to both of the flanking regions of the target site separated 5 to 7 bp apart from each other. The homodimerization of the wild-type FokI domains, however, results in off-target cleavage issues, and this was solved by generating obligate heterodimeric FokI C-terminal domains by the modification of their dimerization interfaces (100, 101). Moreover, enhancement of the FokI domains by mutagenesis was reported (102, 103). In theory, each of the zinc fingers bind to 3-bp-long DNA in a modular fashion (104), and various zinc fingers generated by mutagenesis can be fused in tandem to generate zinc finger proteins targeting any of the desired sequences (105, 106). In reality, however, the zinc finger proteins modularly assembled from each of the zinc fingers often show off-target effects (107) or fail to target DNA (108). There are several methods to select out nonfunctional ZFNs among the new assemblies (109, 110, 111, 112); however, constructing a new functional ZFN is still a major challenge.

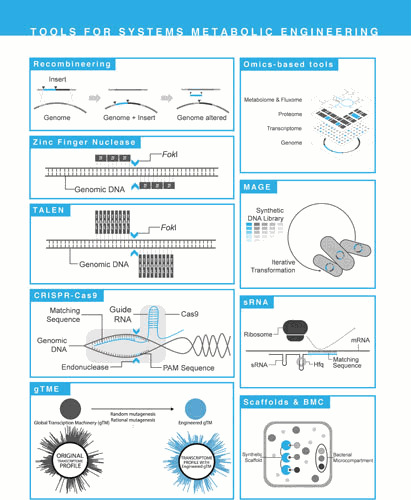

Figure 2.

Tools for systems metabolic engineering. List of tools for genetic modification of candidate strains: recombineering, zinc finger nuclease (ZFN), transcription activator-like effector nuclease (TALEN), clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)/Cas9 system, global transcription machinery engineering (gTME), omics-based tools, multiplex automated genome engineering (MAGE), synthetic small regulatory RNA (sRNA), and scaffold proteins.

Transcription Activator-Like Effector Nucleases (TALENs)

Despite the great modularity of ZFNs, the biggest weakness of this group of nucleases is twofold. First, a single zinc finger domain recognizes 3 bp at once (104), requiring a library of at least 64 (=43) modules for a complete coverage on all possible triplets of base pairs. The massive size of the library renders difficulties for several research groups from easily accessing the library, especially for those consisting of zinc finger domains with high sequence specificity. More importantly, the assembly of zinc finger proteins from each of the zinc finger modules often results in nonfunctional or erroneous products (107, 108). An alternative engineered nuclease was developed to solve these problems with discovery of a group of proteins known as transcription activator-like effectors (TALEs). Initially discovered in plant pathogen Xanthomonas spp., TALEs are secreted from plant pathogens into the host cells and activate the transcription of plant genes, changing the physiology of the host plant (113). A TALE consists of an array of 33 to 35 amino acids repeats, and each repeat specifically binds to a single nucleotide in the major groove (114, 115). The 12th and 13th residues of each repeat, known as repeat variable diresidues (RVDs), determine the base pair specificities of each repeat (116, 117). These properties indicate the superiority of TALEs over zinc finger proteins: TALEs require only four types of repeats that bind to each of the four types of base pairs, while zinc finger proteins need a set of 64 zinc fingers binding to 64 types of 3-bp-long DNA. After unraveling of RVDs in 2009, the application to use TALEs as programmable nucleases was quickly achieved in the very next year (118). Transcription activator-like effector nucleases (TALENs)—programmable nucleases based on TALEs—follow exactly the same scheme as that of ZFNs; the C-terminal nuclease domain of FokI is fused to the C terminus of the TALE arrays (Fig. 2). The use of up to 20 repeats in each TALEN, however, makes the construction of TALENs challenging—the repetitive occurrence of the homologous sequences in TALEN DNA constructs leads to instability of the constructs and their intermediates (119). Nonetheless, attempts to improve the facile assembly of TALENs are continuing (120, 121, 122, 123, 124, 125, 126).

CRISPR/Cas System

In 2002, loci characterized by alternative occurrence of 21- to 37-bp-long repetitive sequences (repeats) and nonrepetitive sequences (spacers) were identified in prokaryotes by a bioinformatics analysis (127). Reflecting the noticeable structural features of theses loci, they are named as clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPRs), although the initial observation was made in 1987 (128). Moreover, protein-coding genes near CRISPRs were found together and named as CRISPR-associated (cas) genes (127). After the first discovery of CRISPR loci, many research groups suggested the role of CRISPR/Cas system as prokaryotic immunity (129, 130, 131). In 2007, the suggested CRISPR’s role as a prokaryotic acquired immune system was confirmed (132). The authors observed that Streptococcus thermophilus exposed to bacteriophages acquired new spacers derived from the phage DNA segments (later termed as protospacers) inside its CRISPR loci (132). Moreover, modification of particular spacers in CRISPR modulated the resistance profile of the host cells against various bacteriophages, indicating close correlation between bacterial resistance against virus and the CRISPR/Cas system (132). Subsequently, involvement of the CRISPR/Cas system in the resistance against plasmids and conjugation were also reported (133, 134). After years of brilliant research, now it is understood that CRISPR loci are transcribed and the resulting CRISPR RNAs (crRNAs) are processed by several components including Cas proteins and RNase III (135, 136, 137, 138). The processed crRNAs then work as effectors together with various other Cas proteins to cleave either DNA targets (135, 139) or RNA targets (140). When CRISPR/Cas systems are targeting their invader DNAs, they interrogate two points: the presence of protospacer adjacent motif (PAM)—the motif adjacent to protospacers that is required by effector Cas proteins to work as a nuclease—and complementarity of crRNA to the protospacer on target DNA (141, 142, 143).

After years of efforts to classify various CRISPR/Cas systems, the systems are now categorized into five types, classified into two classes: type I, type III, and type IV in class 1 CRISPR/Cas system and type II and type V in class 2 CRISPR/Cas system (144, 145, 146, 147). Among three of them, Cas9 protein from Streptococcus pyogenes belonging to type II CRISPR/Cas system (148), is especially the most widely used for genome engineering applications (Fig. 2). In type II CRISPR/Cas system, crRNA are associated with trans-activating crRNA (tracrRNA), and they together bind to the effector nuclease Cas9 (148). Elucidating the dual RNA systems in the CRISPR/Cas9 system, Doudna and her colleagues also created a chimeric guide RNA called single guide RNA (sgRNA) by joining essential motifs of crRNA and tracrRNA, making the system simpler (148). Nowadays, both crRNA/tracrRNA and sgRNA systems are widely used for various applications. While meganucleases, ZFNs, and TALENs require the manipulation of effector proteins to program them to target genomic loci of interest, simple exchange of crRNA or sgRNA for the programming of CRISPR/Cas9 system led to a boom in the field of genome engineering. Although originated from prokaryotes, CRISPR/Cas9 systems are the most actively used in engineering of eukaryotic genomes (149, 150, 151, 152, 153, 154, 155, 156, 157, 158, 159). There are relatively few examples of using CRISPR/Cas9 in prokaryotes (160, 161, 162, 163, 164, 165, 166). The first example of using the CRISPR/Cas9 system in genome engineering of E. coli was reported by Marraffini and colleagues (160). Their first trial utilized two plasmids: pCas9 containing tracrRNA, Cas9, and chloramphenicol resistance gene, and pCRISPR containing CRISPR spacer. Along with the application of recombineering strategy, these two plasmids and an oligo for point mutation were transformed, thus promoting successful recombination with a significant efficiency of 65 ± 14% (160).

The biggest concern in CRISPR/Cas9 systems is their off-target effects, as in other programmable nucleases. There have been many efforts to detect the off-target activity levels of the CRISPR/Cas9 systems (167, 168, 169, 170). Moreover, many trials to reduce off-target activities have been reported, including the use of Cas9 nickases and catalytically dead Cas9 (dCas9)-FokI nucleases (171, 172, 173, 174, 175). In addition, the relatively big size of the Cas9 gene (approximately 4.2 kb) makes gene work on Cas9 more difficult. There is a recent report on an identification of smaller (around 3 kb in gene length) Cas9 from a multidrug-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) isolated at an Irish hospital (176).

Repurposed CRISPR/Cas Systems

The CRISPR system not only has been a crucial genome-editing tool, but it also has been modified to be used as a trans-acting gene knockdown system (177). The Cas9 protein with endonucleolytic activity was inactivated (dCas9) to repurpose this system into a gene expression regulating tool. This repurposed system knocks down gene expression by the following mechanism: when the target-oriented sgRNA and dCas9 are coexpressed, the scaffold of sgRNA binds with dCas9, leading the complex to the DNA sequence near the promoter site as in normal Cas9. After the complex binds the target DNA sequence, the CRISPRi R loop is formed, preventing the propagation of the incoming RNA polymerase and subsequently blocking the target gene transcription effectively. Fusing an activation domain or a repressor domain to dCas9 can be an alternative strategy for regulating gene expression using the CRISPR/Cas9 system. While this idea was successfully implemented in eukaryotic systems multiple times (178, 179, 180), only a single study reported to date has succeeded to activate a target gene with the dCas9-fusion protein system in E. coli (181). The authors fused the omega subunit of RNA polymerase with dCas9 and targeted this complex upstream of the target gene promoter by engineering the corresponding crRNA. The authors tested this system for overexpressing lacZ, which encodes beta-galactosidase, and obtained a 2.8-fold increase in expression when the omega subunit was fused to dCas9 at its C terminus.

Small Regulatory RNAs

While there have been significant advances in the regulation of gene expression by means of developing promoter, ribosome binding site, or intergenic regions between genes in a single operon for fine-tuning of gene expression, modification in chromosomal DNA is not only time consuming and laborious, but also unfit for engineering multiple targets simultaneously (182, 183, 184). As such, a new method for simultaneously studying multiple genes using trans-acting small regulatory RNAs (sRNA) for regulation and fine-tuning of inherent genes in E. coli was developed (185, 186). This strategy derives from native sRNAs in bacteria regulating gene expression by translational control (187). The structure of synthetic sRNA construct consists of three major constituents: a target-binding sequence, scaffold, and terminator (Fig. 2). sRNAs regulate gene expression by base-pairing its sequences to the target translation initiation region, consequently blocking the ribosome from taking action and thus significantly reducing translation efficiency (Fig. 2). The target-binding sequence is engineered into the antisense sequence (24 bp) of the translation initiation region of the target gene to be regulated. The scaffold within sRNA binds to an RNA chaperone Hfq protein, so as to enhance the binding of sRNA to the target mRNA sequence and to catalyze the degradation of mRNA by recruiting RNase E (187, 188). Among the 101 E. coli sRNAs discovered recently, the scaffold of MicC was selected for its strong repression capability. The advantages of using synthetic sRNAs as a tool is in its ability to test knockdown of essential genes and to fine-tune gene expressions, its ease in vector construction thus expediting the experiment process, and its ability to target multiple sites simultaneously. It has also been reported that not only repression, but also activation of certain genes by means of sRNAs exist in nature (189, 190).

Global Transcription Machinery Engineering (gTME)

After decades of extensive study on genotypes and phenotypes of various biological systems, it is now widely accepted that a majority of phenotypes are polygenic, rather than monogenic. Hence, an ability to simultaneously select and adjust multiple genes is very critical to engineer organisms for a desired trait, especially in the field of metabolic engineering. Intuition- and logic-based target gene selection to engineer a single phenotype is limited in many situations. Simultaneous manipulation of multiple target genes chosen is not affordable with traditional gene/genome engineering tools, either. In such situations, mimicking nature’s strategy to develop novel systems or components can be a wise choice—evolution, a series of random mutagenesis and selection. Stephanopoulos and colleagues introduced a concept named global transcription machinery engineering (gTME) that targets components in global transcription regulation for random mutagenesis to randomly manipulate gene expression profile in a transcriptome-wide manner followed by an application of proper selection powers (191, 192). They proved the system both in a eukaryotic microorganism yeast (191) and in a prokaryote E. coli (192). In gTME application in E. coli, one or multiple components involved in global transcription regulation, such as rpoD, are initially selected for construction of mutant libraries. The mutant libraries generated are then introduced into a host microorganism in the presence of a corresponding, nonmutagenized component. Subsequently, an individual organism exhibiting desired traits such as tolerance is selected by applying the proper screening method to the host containing the mutant libraries of the target global transcriptional constituents. The strength of gTME is that it enables engineering of multiple target genes, which are not often intuitive or logical, for desired phenotypes in a short period (191, 192).

Multiplex Automated Genome Engineering (MAGE)

Instead of creating mutant global transcription factors for genome engineering, direct multiplex editing of genomic loci can also be achieved. Church and his colleagues provided the way to simultaneously manipulate multiple genomic loci either randomly or rationally mutagenized (53). Unlike gTME, where transcriptome profiles are altered by mutant global transcription machineries, MAGE can generate a library of hosts with multiple genomic loci edited directly in the genomic sequence where the editing includes residue substitution, deletion, and insertion. With bacteriophage λ Red ssDNA binding protein β expressed, mutation-containing ssDNA oligonucleotides for targeting the lagging strand of replication fork during DNA replication at designated genomic loci are introduced into a host by electrophoresis, generating a daughter population of hosts containing targeted sequences edited. A pool of various oligonucleotides can be delivered into the host at once, and repeated delivery of the oligo library results in a set of hosts with genomic sequences differentially modified in each generation. It is noticeable that the whole procedure of repetitive oligo delivery is automatically operated with the help of machinery and an operating program developed in the research (53). Once experimental conditions are optimized, more than 30% of the host population incorporates mutation for a single locus, which only takes 2 to 2.5 h (53). Modified versions of MAGE for improved modification efficiency have also been reported (193, 194).

Conjugative Assembly Genome Engineering (CAGE)

While recombinant plasmids can be transferred among strains after they are constructed in one host strain, modifications made directly on genomic DNA, however, are hard coded and difficult to be transferred in parallel. In order to reintroduce the same chromosomal modifications in a different strain, the same modification procedures must be performed repeatedly. This makes parallel genomic modification-based engineering inefficient and time consuming compared with plasmid-based engineering. In 2011, Church group reported genome-wide substitution of every TGA stop codon to TAA by accumulating pieces of partial genomic modifications made on each host cell line into a single, final host strain (195). They named the system employed for this achievement as conjugative assembly genome engineering (CAGE), which literally describes the core mechanism involved in this system.

CAGE maximally utilizes the virtue of DNA transfer from one cell to another during a process called conjugation. Isaacs et al. split the F+ plasmid, which enables the host cell working as a donor cell during conjugation, into two parts: oriT and the other constituents. oriT, the starting point of DNA replication and subsequent transfer of F+ plasmid to a recipient cell during conjugation, is integrated into the host genome to make the host competent for a donor role (195). This causes the whole genomic DNA to be replicated and transferred to the recipient cell during conjugation. The remaining components in F+ plasmid, in contrast, are retained as a closed-circular plasmid and introduced to the donor cell during CAGE process. While they help the process of conjugation, they are not transferred to the recipient since they are physically separated from oriT. The prepared donor cells are then cocultured with recipient cells, promoting conjugation between two different cell populations to transfer the modified genomic DNA from donors to the recipients. Subsequently, the transferred donor genomic DNA substitutes the corresponding region in recipient genome with the help of recipient cell’s endogenous recombination machinery (195).

The recombination, however, is a stochastic process and the points where recombination occurs are randomly chosen. Consequently, the probability for a locus on donor genomic DNA to replace the corresponding recipient DNA segment is higher as the locus is located further from both ends of the linearized donor DNA fragment, following simple probability theories. To make sure the engineered regions on donor genomic DNA successfully substitutes the recipient DNA, the engineered region on donor cells is bounded by oriT and a positive selection marker, including antibiotic resistance genes (195). Moreover, the starting point of a region to be replaced on recipient genome is defined by a positive-negative selection marker, such as tolC (196) and galK (45). Together with these markers, resulting recombinant cells with the first recombination point occurring too far away from oriT are selected out by negative selection effect of the positive-negative marker. On the other hand, ones with the second recombination occurring too close to the first recombination site are selected out since they cannot survive without a positive marker. In this manner, the only final recombinant strains containing the whole engineered segment of the donor genome are obtainable. These processes can be repeated until all of the pieces of partially engineered regions of each cell line are accumulated in a single cell line.

Trackable Multiplex Recombineering (TRMR)

The random engineering of multiple genomic loci allows isolation of new strains with unexpected target genes modified in an unexpected way. Obtaining such a brand new strain itself is a great work, but it will be more amazing to know how the new strain is changed. A method called trackable multiplex recombineering (TRMR), suggested by Warner et al., provides a way to manipulate multiple genomic loci, detect the loci affected, and elucidate the manner in which they are modified (197). In TRMR, 20-bp-long “barcode sequences” are inserted upstream or downstream of the target genomic loci while the target loci are simultaneously modified with the help of the recombineering techniques. The barcodes are used for detecting the changes that occurred at the target loci. Combined with microarray techniques, they can give information on allelic frequencies of the modified genes in a bacterial population subjected to TRMR (197, 198).

Synthetic Scaffolds and Bacterial Microcompartments

The idea of spatial organization of enzymes was first conceived from mammalian signal transduction pathways where grouping of enzymes by spatial organization is needed to handle signal transductions from one billion proteins (199); similarly, metabolism within a cell is a highly complex network of chemical reactions. With this complexity, problems may occur in regard to unwanted side reactions (200), limiting metabolic flux due to low substrate specificity (201), low productivity and yield (9), and hindrance of cell growth by toxic materials (202). Handling these problems would require channeling of substrates or directing target chemicals or enzymes to a confined area. To cope with these problems, examples from nature were readily adopted (203), which include tryptophan synthase inherent in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium (204), carbamoyl phosphate synthetase, and glutamine phosphoribosylpyrophosphate aminotransferase in E. coli, and dihydrofolate reductase-thymidylate synthase inherent in Leishmania major (205). Additionally, carboxysomes were discovered and characterized in cyanobacteria and chemolithotrophic bacterial species, in which rate-limiting steps involved in the Calvin cycle take place (206). Inspired by these examples, synthetic scaffolds and bacterial microcompartments (BMCs) were developed. Synthetic scaffolds aim at localizing enzymes in order to increase the local intermediate concentration of a desired biochemical reaction or to prevent toxic materials from damaging the cell. Starting from the development of synthetic protein scaffold (201), synthetic scaffolds using RNA (207) and DNA (208) as building blocks were sequentially developed, all of which were demonstrated in E. coli.

BMCs, which resemble organelles within eukaryotic cells, tend to encapsulate large numbers of certain enzymes to form distinct reaction environments. This tendency increases the concentration of intermediates such as in carboxysome, in which CO2 is concentrated around the otherwise inefficient RuBisCO (209, 210). Additionally, toxic intermediates are effectively blocked from incorporating into the host metabolism as in examples of Eut and Pdu microcompartments (211, 212, 213). It is interesting to note that BMCs are thought to regulate the amount and types of chemicals that can go through the compartment, while intermediates and toxic materials seemed to be kept inside of the bacterial microcompartments (BMCs), nontoxic native substrates, and products diffuse across the compartment relatively easily (210). The precise mechanism of how this happens is yet to be determined, although several hypotheses exist (212, 214, 215). Encapsulins and lumazine synthase complexes are two other simpler microcompartment systems reported (216, 217).

Omics Tools

In systems metabolic engineering, omics-based tools are system-wide strategies that utilize data from x-omes to analyze hosts on the systems level and unravel unknown mechanisms to enhance the production of target chemicals. Since a tremendous amount of data is associated with multiomics-based approaches, computational simulations often aid in the omics analysis. Readers are encouraged to refer to several excellent reviews on multiomics studies and incorporation of in silico simulations (218, 219, 220, 221).

The first bacterial genome sequencing of Haemophilus influenzae opened the field of genomics, starting a new era in omics-based approaches (222). Numerous sequencing technologies have emerged since this first onset, facilitating the development of genomics (223). With the increasing amount of genome data, comparative genomics comparing the genome sequences of two organisms has become feasible. From the genomic data open and available for all, genome-scale modeling has been developed actively, which will be explained in later sections (224, 225, 226).

However, the expression levels of each gene cannot be identified through genomics. Transcriptomics analyzes the mRNA levels of various genes at a time, particularly the change of gene expression levels when given perturbation (218, 227). The development of transcriptomics has had a deep relationship with the development of high-throughput microarray development (228). By measuring the fluorescence in the microarray, the expression levels of each gene can be examined. For transcriptome modeling, a reverse-engineering strategy named network identification by regression (NIR) was used (229). Transcriptomics has several applications, such as the elucidation of useful metabolic genes (230) or the identification of target genes or pathways to be engineered (231).

Unlike transcriptome, proteome reflects the posttranscriptional regulations by small RNAs, mRNA degradation, and represents the real phenotype of the cell much more clearly than the transcriptome does. Readers are invited to read an excellent review on the proteome of E. coli covering aspects not explained in this section (232). Two-dimensional (2D) electrophoresis is a widely used method for analyzing an organism’s proteome (233). For highly expressed proteins, however, biased results were often shown (234), leading to the development of non-gel-based approaches such as mass spectrometry (MS) (235), matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization–time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) (236), and liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) (237). The main interest in proteomics analysis is to examine the change in cellular and metabolic states during the production of metabolites of interest.

Since the proteome of an organism still does not precisely represent the physiology of the cell and enzyme activities, additional omics was needed, leading to the emergence of metabolomics (238). Several analytical methods were adopted for metabolomic analyses including nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) (239), high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) (240), and MS (241). Metabolomics, however, contains a serious problem arising from the dynamic turnover events of cellular metabolites. Therefore, an instant quenching method is required (242). Other problems such as cultivation techniques and metabolite extraction methods are some of the ongoing challenges.

Fluxomics is widely modeled and applied in metabolic engineering, because it analyzes the reaction rates of different metabolic pathways (243, 244). Because it is almost impossible to obtain the dynamic intracellular fluxes of a cellular system, indirect approaches are used for metabolic flux analysis (MFA): 13C-based flux analysis and constraints-based flux analysis. The basic assumption in these analyses is that the cellular fluxes are at steady state. In 13C-based analysis, an isotope-labeled carbon source is fed to the medium, letting 13C-incorporated metabolites to be detected and patterns to be analyzed by NMR and gas chromatography mass spectrometry (GC/MS) (245). However, expensive isotope samples, difficulty in conducting experiments, and large-scale calculations are the bottlenecks in this approach. Constraints-based flux analysis is a set of algorithms for optimization-based simulation (246). Metabolic flux analysis can also be used for elucidating the metabolic characteristics of a newly identified organism such as in the case of Mannheimia succiniciproducens (247).

Other kinds of omics including glycomics, lipidomics, and interactomics have also been actively researched to date. Because each omics study has its own drawbacks, the integrated analysis and use of omics are required for a comprehensive analysis of an organism. The first attempt to integrate multiple omics was by Hood and colleagues to characterize the phenotype of S. cerevisiae (248). Several other significant multiomics studies regarding E. coli are as listed (249, 250). A prominent tool that deals with the multiomics data of E. coli is EcoCyc (251, 252, 253). Through the latest version of EcoCyc, a tremendous amount of data including genes, metabolites, reactions, operons, metabolic pathways, and metabolic flux models of E. coli can be accessed (253).

In Silico Genome-Scale Metabolic Network Models and Tools

A massive amount of genome data has been accumulating since the beginning of the genomic era. The availability of such information allowed researchers to understand and predict the physiology of organisms. One of the initial studies used such information to predict the growth of bacteria (254, 255). Currently, these data are routinely applied to predict and analyze detailed physiological and metabolic status of bacteria (22, 25, 225, 256, 257, 258). There are several comprehensive reviews covering the diverse applications of genome data for various purposes (259, 260, 261, 262, 263).

A single genome-scale metabolic network model consists of an immense amount of data from various literature, experimental sets, and databases. The data integrated into a single genome-scale model includes information on genome-wide metabolic genes, hundreds to thousands of metabolites, and thousands of stoichiometric metabolic reactions. Constructing such models is beyond the scope of this review, and descriptions of the methods to construct such models can be found from other reviews and book chapters (259, 260, 264, 265). During past three decades of E. coli genome-scale reconstruction history, several versions of thorough E. coli genome-scale metabolic network models have been published (225, 256, 257, 266), such as EcoMBEL979 (266), iAF1260 (225), iJO1366 (256), and EcoCyc-18.0-GEM (267) containing thousands of metabolites, metabolic enzymes, and stoichiometric reaction rulesets.

An E. coli genome-scale model alone cannot exhibit the metabolic state of this bacterium in a given condition. To determine the metabolic state, flux information of each metabolic reaction should be determined. However, there are many more metabolic reactions than metabolites in the models, as in real E. coli, rendering the complete determination of the exact flux solutions impossible; for example, the most thorough E. coli K-12 MG1655 genome-scale model, iJO1366, contains 1,136 metabolites and 1,473 metabolic reactions (256). In bacteria, the complex sets of regulatory components fine-tune the metabolic fluxes. In current E. coli genome-scale models, unfortunately, such complicated regulations have not been implemented yet. Therefore, during in silico simulations, an algorithm mimicking or representing such regulations should be employed to select the best prediction on the real metabolic state among the vast solution space.

Flux balance analysis (FBA) is the most widely used algorithm. Based on genome-scale models, FBA applies stoichiometric information as major constraints and builds a solution space for metabolic flux distribution (255, 268, 269). To specify a solution that best represents the actual state among the possible solutions, FBA generally employs an objective function of maximum biomass formation. This is based on the assumption that E. coli and other bacteria have evolved to maximize their growth and replication, reflecting the generally acknowledged expression “The goal of every bacterium is to become bacteria” as said by microbiologist Stanley Falkow. Simulation of how a genetic perturbation modulates the flux distribution is also an important aspect in metabolic engineering, especially for the selection of engineering targets. In addition to FBA, another useful algorithm for this purpose is the minimization of metabolic adjustment (MOMA) algorithm (270). This algorithm is based on the idea that when perturbation is introduced in a bacterial strain by knocking out one or more genes, the bacteria redistribute their metabolic fluxes to minimize flux changes (270). Based on the reference flux distribution data obtained from FBA, MOMA can be employed to predict modifications in the flux distribution. The third noticeable algorithm is the regulatory on/off minimization (ROOM) algorithm (271). This algorithm is similar to MOMA, but differs in that ROOM focuses on minimizing the number of fluxes significantly changed, i.e., turned on or off, while MOMA focuses on minimizing the total magnitude of changes throughout the whole metabolic fluxes (271). All these algorithms predict the physiology of bacteria fairly well, and each has its strengths and weaknesses in different conditions, such as initial stages or steady-state phases (271).

These genome-scale metabolic models and metabolic state prediction algorithms can be used together to select engineering targets for improving strain performances. For these purposes, several algorithms have been developed and reported. These include OptForce (272), OptKnock (273), OptGene (274), OptSwap (275), FSEOF (flux scanning based on enforced objective flux) (258), FVSEOF (flux variability scanning based on enforced objective flux) (276), and CosMos (277). Most algorithms contain one of the three metabolic flux prediction algorithms FBA, MOMA, and ROOM within. Moreover, there are numerous environments for in silico simulation, such as MatLab-based COBRA Toolbox (278, 279) and a stand-alone program suite MetaFluxNet (280, 281). With the help of these models, algorithms, and programs, targets of gene knockout, amplification, and flux level adjustment to improve strains can be predicted.

Design and construction of novel biosynthetic pathways can also be assisted by in silico pathway prediction tools. Such algorithms consist of two components: reaction rule sets and heuristics for narrowing down most probable pathway candidates. Currently, numerous pathway prediction tools are available for designing novel biosynthetic pathways for chemicals of interest, including PathoLogic (282), PathMiner (283), BNICE (284), Pathway Hunter Tool (285), DESHARKY (286), UM-PPS (287), MetaRoute (288), Rahnuma (289), ReTrace (290), Atom Metanet (291), Cho et al. 2010 (292), PathPred (293), RetroPath (294), SymPheny Biopathway Predictor (27), XTMS (295), GEM-Path (296), and RouteSearch (297). There are a number of indepth reviews describing and analyzing such useful tools (259, 260, 261, 262, 263, 298, 300).

Plasmid Addiction System

Selection for plasmid-transformed bacteria has been the foundation in development of biotechnology, and the use of plasmids for industrial application is ever crucial (301, 302). The plasmid-harboring bacteria are often selected in the presence of antibiotics. However, the use of antibiotics for industrial-scale systems is often undesired due in part to the cost of antibiotics, contamination of products with residual antibiotics, and possible degradation of antibiotics leading to instability of plasmids during cultivation (303). In light of problems with antibiotics in industrial systems, the plasmid addiction system delivers an alternative mode of selection while maintaining plasmids in an antibiotics-free environment.

The plasmid addiction system can be largely categorized into three types: toxin/antitoxin-based, metabolism-based, or operator repressor titration systems (301). An example for the toxin/antitoxin-based system adapted from phage P1 protein called Doc (death on curing) and Phd (prevent host death) where the former is toxin and latter is antitoxin (304, 305). The toxin is stable and causes cell death in the absence of plasmid, whereas the unstable antitoxin prevents cell death in the presence of plasmid. Cell propagation thus only depends on the presence of plasmid, which harbors both toxin and antitoxin, where the latter inhibits the activity of the former. In the operator repressor titration system, a gene essential for metabolism, such as dapD, is controlled under the lac operator/promoter (306). Repression of dapD expression prevents L-lysine biosynthesis and peptidoglycan chain cross-linking (307). The host lacI repressor thus inhibits growth unless it is sequestered or “titrated” away from the lac operator/promoter controlling dapD expression. This titration is achieved by introducing another lac operator/promoter on a multicopy plasmid (303). Similarly, an essential gene for cell growth and metabolism is deleted in the host chromosome in the metabolism-based system. (308). A notable study using this system involves the deletion of dapE in the host chromosome and complementing it with dapL from Synechocystis sp. PCC 6308 (301). Using this strategy, the transformed E. coli was able to maintain the plasmid during cultivation at a 400-liter fermentation in a 650-liter tank for cyanophycin production. The plasmid stability reported here is at 98%, and up to 18% (w/w) of dry cell weight (DCW) for the polymer was demonstrated. It must be noted that this study serves as an important example in the field of systems metabolic engineering for producing value-added chemicals at a semi-industrial scale without any antibiotics (301).

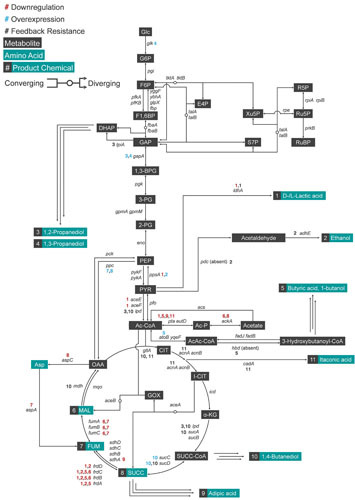

STRATEGIES FOR SYSTEMS METABOLIC ENGINEERING OF E. COLI

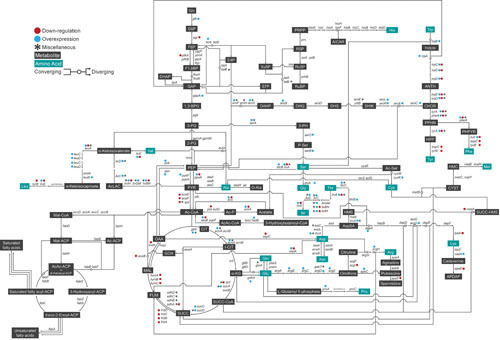

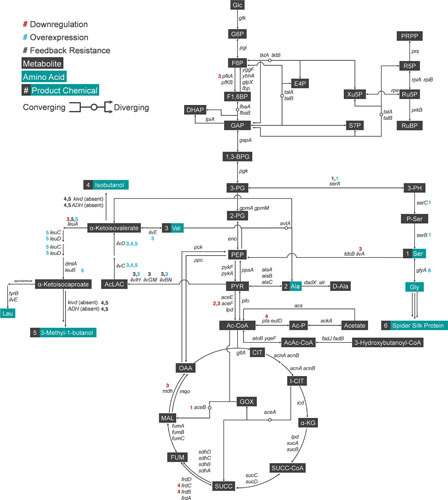

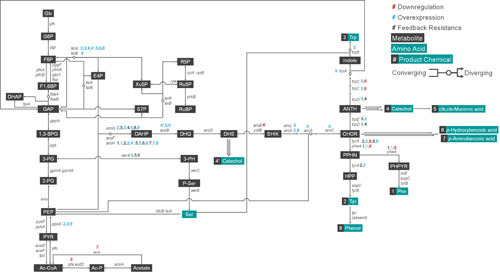

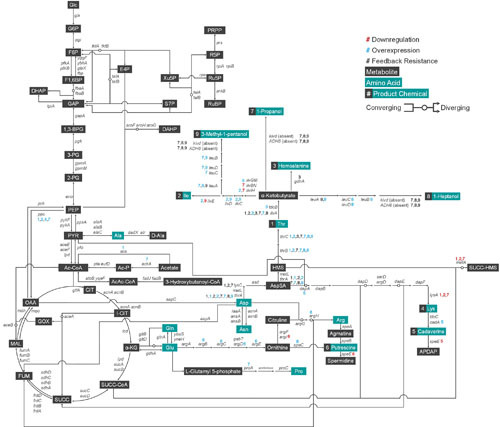

The hallmark of systems metabolic engineering is to produce desired chemicals with engineered microbes not only to industrial-scale standards, but also to bring changes imperative to the chemical industry. To achieve such goals, various strategies described here have been developed to engineer both native and synthetic pathways of E. coli for the production of valuable chemicals (Fig. 3). The strategies described here utilize various tools including those listed in the previous section. Table 1 summarizes notable achievements in the production of valuable chemicals in E. coli strains with metabolic engineering strategies described in genotypic notation.

Figure 3.

The endogenous metabolism of E. coli. The endogenous metabolic pathway of E. coli mapping products (metabolites in black boxes and amino acids in turquoise boxes) and the genes (italicized) of the enzymes responsible for the reactions based on EcoCyc E. coli database. Every overexpression (blue circle), downregulation (red circle), and all other miscellaneous modifications including feedback-release (asterisk) attempted in E. coli for systems metabolic engineering purposes are noted. Convergence and divergence of metabolites are denoted by circular nodes, where some reactions are reversible. As an example for reversible reaction, F6P and GAP converge to form E4P and Xu5P; conversely, E4P and Xu5P converge to form F6P and GAP. Glc, glucose; G6P, glucose 6-phosphate; F6P, fructose 6-phosphate; F1,6BP, fructose 1,6-bisphosphate; GAP, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate; DHAP, dihydroxyacetone phosphate; 1,3-BPG, 1,3-bisphosphoglycerate; 3-PG, 3-phosphoglycerate; 2-PG, 2-phosphoglycerate; PEP, phosphoenolpyruvate; PYR, pyruvate; Ac-CoA, acetyl-CoA; CIT, citrate; I-CIT, isocitrate; α-KG, α-ketoglutarate; SUCC-CoA, succinyl-CoA; SUCC, succinate; FUM, fumarate; MAL, malate; OAA, oxaloacetate; GOX, glyoxylate; E4P, erythrose 4-phosphate; Xu5P, xylulose 5-phosphate; S7P, sedoheptulose 7-phosphate; R5P, ribose 5-phosphate; Ru5P, ribulose 5-phosphate; RuBP, ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate; PRPP, 5-phosphoribose 1-pyrophosphate; AICAR, 5-amino-1-(5-phosphoribosyl)imidazole-4-carboxamide; His, L-histidine; DAHP, 3-deoxy-arabino-heptulosonate 7-phosphate; DHQ, 3-dehydroquinate; DHS, dehydroshikimate; SHIK, shikimate; CHOR, chorismate; PPHN, prephenate; HPP, 4-hydroxyphenylpyruvate; Tyr, L-tyrosine; PHPYR, phenylpyruvate; Phe, L-phenylalanine; ANTH, anthranilate; Trp, L-tryptophan; 3-PH, 3-phosphohydroxypyruvate; P-Ser, 3-phosphoserine; Ser, L-serine; Ac-Ser, acetyl-serine; AcLAC, acetolactate; Val, L-valine; Leu, L-leucine; Ala, L-alanine; D-Ala, D-alanine; Ac-P, acetyl phosphate; AcAc-CoA, acetoacetyl-CoA; Glu, L-glutamate; Gln, L-glutamine; Arg, L-arginine; Pro, L-proline; Asp, L-aspartate; Asn, L-asparagine; AspSA, aspartate-semialdehyde; Lys, L-lysine; HMS, homoserine; Thr, L-threonine; Ile, L-isoleucine; SUCC-HMS, succinylhomoserine; CYST, cystathionine; HMC, homocysteine; Met, L-methionine; Ac-ACP, acetyl-acyl carrier protein (ACP); Mal-CoA, malonyl-CoA; Mal-ACP, malonyl-ACP; AcAc-ACP, acetoacetyl-ACP.

Table 1.

| Product | Strain designation (vector if any) | Note | Titer (g liter−1) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metabolites from central carbon metabolism and derivatives | ||||

| Malic acid | XZ658 | KJ060 (ATCC 8739 ΔldhA ΔackA ΔadhE ΔpflB) ΔmgsA ΔpoxB ΔfrdBC ΔsfcA ΔmaeB ΔfumB ΔfumAC | 34 | 476 |

| Fumaric acid | CWF812 (pTac15kppc) | W3110 ΔiclR ΔfumC ΔfumA ΔfumB ΔarcA ΔptsG ΔaspA ΔlacI PgalP::Ptrc; vector-based overexpression of ppc | 28.2 | 309 |

| Succinic acid | JCL1208 (pPC201) | JCL1208 (E. coli K-12 F– λ– rpoS396(Am) rph-1 lacIq lacZ::Tn5 ΔrecA zfi::Tn10); vector-based overexpression of ppc | 10.7 | 310 |

| AFP111 (pTrc99A-pyc) | AFP111 (E. coli F– λ– rpoS396(Am) rph-1ΔpflAB::CmR ldhA::KmR ptsG); vector-based overexpression of pyc (Rhizobium etli) | 99.2 | 477 | |

| KJ122 | KJ073 (E. coli C ΔldhA::FRT ΔadhE::FRT Δ(focA-pflB)::FRT ΔackA ΔmsgA ΔpoxB) ΔackA ΔadhE ΔldhA ΔfocA-pflB ΔtdcDE ΔcitF ΔaspC ΔsfcA | 82.7 | 337 | |

| D-Lactic acid | ALS974 | YYC202 (DSM 14335, Hfr zbi::Tn10 poxB1 Δ(aceEF) rpsL pps-4 pfl-1) frdABCD | 138 | 478 |

| L-Lactic acid | LA20ΔlldD (pZSglpKglpD) | LA02 (MG1655 Δpta::FRT ΔadhE::FRT ΔfrdA::FRT-KmR-FRT) ΔmgsA::FRT ΔldhA::ldh (Streptococcus bovis) ΔlldD::FRT; vector-based overexpression of glpK and glpD | 50.1 | 479 |

| Butyric acid | BuT-8L-ato | BL21 ΔptsG ΔpoxB HK022::PRPL-glf (Zymomonas mobilis) ΔldhA ΔfrdA φ80attB::PL-ter (Terponema denticola DSM14222) λattB::PL-crt (Clostridium acetobutylicum DSM792) ΔadhE::φ80attB::PL-phaA (Cupriavidus necator)-hbd (C. acetobutylicum DSM792) PL-atoDABD Δpta | >10 | 480 |

| Itaconic acid | BW25113(DE3) Δpta ΔldhA (pKV-CGA) | BW25113 (E. coli K-12 F– λ– rph-1Δ(araD-araB)567 ΔlacZ4787(::rrnB-3) Δ(rhaD-rhaB)568 hsdR514)(DE3) Δpta ΔldhA; vector-based overexpression of cadA (opt, Aspergillus terreus), acnA (opt, Corynebacterium glutamicum), and gltA (opt, C. glutamicum) | 0.69 | 481 |

| SO11 (pLysS, pETHis-cad, pRSF-acnB) | SO02 (BW25113(DE3) icd); vector-based overexpression of cad (A. terreus) and acnB | 4.34 | 482 | |

| Adipic acid | AA7 (pTrc-ter-paaJ, pZS*27ptb-buk1-paaH1-ech) | QZ1111 (MG1655 ΔptsG ΔpoxB Δpta ΔsdhA ΔiclR); vector-based overexpression of paaJ (E. coli), paaH1 (Ralstonia eutropha H16), ech (R. eutropha H16), ter (Euglena gracilis), ptb (C. acetobutylicum), and buk1 (C. acetobutylicum) | 0.000639 | 324 |

| Ethanol | KO12 | E. coli W pfl+ pfl::(pdc (Z. mobilis)-adhB (Z. mobilis)-CmR) (Selected for high CmR (600 ng/liter) and hyperexpressive for pdc and adh) frd recA; | 54 | 483, 484 |

| Isopropanol | TA11 (pTA39, pTA36) | ATCC 11303 (E. coli B) lacIq TcR; vector-based overexpression of thl (C. acetobutylicum), adc (C. acetobutylicum), atoA (E. coli), atoD (E. coli), and adh (Clostridium beijerinckii) | 4.9 | 315 |

| Same as above. Highest titer achieved by gas stripping recovery method | 143 | 316 | ||

| 1,2-Propanediol | AG1 (pNEA30) | AG1 (F- λ. endA1 hsdR17 [rK−, mK+] supE44 thi-1 recA1 gyrA96 relA1); vector-based overexpression of mgs and gldA | 0.7 | 485 |

| ‘Evolved E. coli tpiArc’ Ptrc16-gapA (pJB137-PgapA-ppsA) | ‘Evolved E. coli tpiArc’ (MG1655 lpdfbr (low sensitivity to NADH) tpiArc (reconstructed tpiA) ΔpflAB ΔadhE ΔldhA::CmR ΔgloA Δald ΔaldB Δedd ΔarcA Δndh evolved under microaerobic conditions) Ptrc16-gapA; vector-based overexpression of ppsA | 3.7 | 486 | |

| 1,3-Propanediol | FMP′ 1.5gapA ΔmgsA (pSYCO106) | FM5 glpK gldA ndh pstHIcrr galP-Ptrc glk-Ptrc* arcA edd gapA-P1.5 mgsA; vector-based overexpression of DAR1 (Saccharomyces cerevisiae), GPP2 (S. cerevisiae), dhaB1 (Klebsiella pneumoniae), dhaB2 (K. pneumoniae), dhaB3 (K. pneumoniae), dhaX (K. pneumoniae) | 135.3 | 487 |

| 1-Butanol | JCL187 (pJCL17, pJCL60) | BW25113 F′ [traD36 proAB+ lacIq ZΔM15 TcR] ΔadhE, ΔldhA, ΔfrdBC, Δfnr, Δpta; vector-based overexpression of atoB (E. coli), adhE2 (C. acetobutylicum), crt (C. acetobutylicum), bcd (C. acetobutylicum), etfA (C. acetobutylicum), etfB (C. acetobutylicum), and hbd (C. acetobutylicum) | 0.552 | 334 |

| JCL299 (pEL11, pIM8, pCS138) | JCL299 (BW25113 F′ [traD36 proAB+ lacIq ZΔM15 TcR] ΔadhE ΔldhA ΔfrdBC Δpta); vector-based overexpression of atoB (E. coli), adhE2 (C. acetobutylicum), crt (C. acetobutylicum), hbd (C. acetobutylicum), ter (Treponema denticola), and fdh (Candida boidinii) | 30 | 488 | |

| 1,4-Butanediol | ECKh-422 (pZS*13-sucCD-sucD-4hbd/sucA, pZE23S-025B-34) | MG1655 lacIq ΔadhE ΔldhA ΔpflB ΔlpdA::lpdD354K (K. pneumonia) Δmdh ΔarcA gltAR163L SmR; vector-based overexpression of sucC (E. coli), sucD (E. coli), sucD (Porphyromonas gingivalis W83),4hbd (P. gingivalis W83), sucA (Mycobacterium bovis), cat2 (P. gingivalis W83), and 025B (aldehyde dehydrogenase, C. beijerinckii) | 18 | 27 |

| 1-Hexanol | JCL299 (pEL11, pEL102, pCS138) | JCL299; vector-based overexpression of atoB (E. coli), adhE2 (C. acetobutylicum), crt (C. acetobutylicum), hbd (C. acetobutylicum), bktB (R. eutropha), and fdh (C. boidinii) | 0.047 | 336 |

| Ethylene | DH5α (pEFE30) | DH5α; ethylene-forming enzyme (EFE) gene(Pseudomonas syringae pv. phaseolicola PK2) | Detected | 363 |

| Ectoine | DH5α (pAKECT1) | DH5α; vector-based overexpression of lysC (C. glutamicum MH20-22B), ectA (Marinococcus halophilus), ectB (M. halophilus), and ectC (M. halophilus) | 57 mg/g DCW | 489 |

| 2-Pentanone | JCL299 (pDK69 and pEL142) | JCL299; vector-based overexpression of ter (T. denticola), crt (C. acetobutylicum), hbd (C. acetobutylicum), bktB (R. eutropha), pcaI (Pseudomonas putida), pcaJ (P. putida), and adc (C. acetobutylicum) | 0.24 | 333 |

| Amino acids and derivatives | ||||

| l-Serine | YF-7 (pYF-1) | DH5α ΔsdaA ΔiclR ΔarcA ΔaceB; vector-based overexpression of serAfbr, serB, and serC | 8.3 | 490 |

| l-Alanine | ALS887 (pTrc99A-alaD) | CGSC 6162 (DC80 aceF10 fadR200 tyrT5(AS) adhE80 mel-1) aceF ldhA; vector-based overexpression of alaD (Bacillus sphaericus) | 32 | 491 |

| l-Valine | VAMF (pKBRilvBNCED, pTrc184ygaZHlrp) | W3110 ΔlacI ilvGatt ::Ptac ilvBatt::Ptac ilvHG41A,C50T ΔilvA ΔpanB ΔleuA ΔaceF Δmdh ΔpfkA::KmR; vector-based overexpression of ilvB, ilvN, ilvC, ilvE, ilvD, ygaZ, ygaH, and lrp | 7.55 | 22 |

| WLA (pKBRilvBNmutCED, pTrc184ygaZHlrp) | E. coli W ΔlacI ΔilvA; vector-based overexpression of ilvB, ilvNfbr, ilvC, ilvE, ilvD, ygaZ, ygaH, and lrp | 60.7 | 24 | |

| l-Threonine | TH28C (pBRThrABCR3) | WL3110 (W3110 ΔlacI) thrAC1034T lysCC1055T Pthr::Ptac ΔlysA ΔmetA ilvAC290T Δtdh ΔiclR Pppc::Ptrc ΔtdcC Pacs::CmR-Ptrc; vector-based overexpression of thrAC1034T, thrB, thrC, rhtA, rhtB, and thtC | 82.4 | 25 |

| l-Isoleucine | ILE03 (pBRthrABCygaZH, pTacilvAIH) | TH20 (W3110 ΔlacI, thrAC1034T, lysCC1-55T, Pthr::Ptac, ΔlysA, ΔmetA, ilvAC290T, Δtdh, ΔiclR, Pppc::Ptrc) ilvAC1339T, G1341T, C1351G, T1352C (fbr), PilvEDA::Ptrc, PilvC::Ptrc, Plrp::Ptrc; vector-based overexpression of thrAC1034T, thrB, thrC, ygaZ, ygaH, ilvAfbr , ilvI, and ilvH | 9.46 | 21 |

| l-Homoalanine | ATCC 98082 ΔrhtA (pZElac_ilvABS_GDH) | Threonine overproducer ATCC 98082 (VNIIgenetika 472T23; ilvA442 supE spot thrC1010 Sac+ thrR) ΔrhtA; vector-based overexpression of ilvA (Bacillus subtilis) and gdhA (K92V, T195S) | 5.4 | 19 |

| l-Lysine | NT1003 (pSC101-ppc-pntB-aspA) | NT1003 (l-Lysine strain, ΔMet ΔThr, CCTCC No. M 2013239); vector-based overexpression of ppc, pntB, and aspA | 134.9 | 492 |

| l-Phenylalanine | AR-G91 | BW25113(DE3) tyrR::PT7-aroFfbr-pheAfbr | 1.255 | 313 |

| YP1617 (pACYA177 harboring aroF and pheA) | YP1617 (l-tyrosine auxotroph, CCTCC No. M 2013320); vector-based overexpression of aroF and pheA | 56.2 | 493 | |

| l-Tyrosine | AR-G2 | BW25113(DE3) tyrR::PT7-aroFfbr-tyrAfbr | 0.852 | 313 |

| S17-1 (pTyr-a, pTyr-b) | S17-1; vector-based overexpression of tyrA, tyrC, aroG, aroK, aroF, ppsA, tktA, and anti-csrA and anti-tyrR sRNAs | 21.9 | 185 | |

| l-Tryptophan | NST100 | E. coli K-12 | ∼1.4 | 494 |

| Dpta/mtr-Y (pSV-709, pMEL03-Y) | TRTH0709 (E. coli K-12 ΔtrpR Δtna; vector-based overexpression of aroGfbr, trpEfbr, trpD, trpC, trpB, trpA, and serA) Δpta Δmtr; vector-based overexpression of tktA, ppsA, and yddG | 46.68 | 20 | |

| 3-Aminopropionic acid | CWF4NA2 (pTac15kPTA, pSynPPC7) | W3110 ΔiclR ΔfumC ΔfumA ΔfumB ΔptsG ΔlacI PaspA::Ptrc Pacs::Ptrc; vector-based overexpression of panD (C. glutamicum ATCC 13032), aspA, and ppc | 32.3 | 495 |

| Cadaverine | XQ56 (p15CadA) | WL3110 - ΔspeE ΔspeG ΔygjG ΔpuuPA PdapA::Ptrc; vector-based overexpression of cadA | 9.61 | 312 |

| Putrescine | XQ52 (p15SpeC) | W3110 ΔspeE ΔspeG ΔargI ΔpuuPA ΔrpoS PargECBH::Ptrc PspeF-potE::Ptrc PargD::Ptrc PspeC::Ptrc; vector-based overexpression of speC | 24.2 | 311 |

| 1-Propanol | CRS-BuOH 23 (pCS49, pSA62, pSA55I) | JCL16 (BW25113 F′ [traD36 proAB+ lacIq ZΔM15 TcR]) ΔmetA Δtdh ΔilvB ΔilvI ΔadhE: vector-based overexpression of thrAfbr (E. coli ATCC 21277) thrB (ATCC 21277), thrC (ATCC 21277), ilvA, leuA, leuB, leuC, leuD, kivd (Lactococcus lactis), and ADH2 (S. cerevisiae); The strain also produces equimolar ratio of 1-butanol | ∼1 | 496 |

| PRO2 (pBRthrABC-tac-cimA-tac-ackA, pTacDA-tac-adhEmut) | W3110 strain ΔlacI thrAC1034T lysCC1055T Pthr::Ptac ΔlysA ΔmetA ilvAC1139T, G1341T, C1351G, T1352C)T ΔtdhA ΔiclR Pppc::Ptrc ΔilvIH ΔilvBN ΔrpoS; vector-based overexpression of thrA, thrB, thrC, cimA (Methanocaldococcus jannaschii), ackA, atoD, atoA, and adhEmut | 10.8 | 314 | |

| Acetoin | XL1-Blue (pAL306) | XL1-Blue; vector-based overexpression of alsS (B. subtilis) and alsD (Aeromonas hydrophila) | 21 | 497 |

| 2,3-Butanediol | BL21(DE3) (p18COR) | BL21(DE3); vector-based overexpression of budA (co, K. pneumonia) and budC (co, K. pneumoniae) | 1.04 | 498 |

| 2-Butanone | AL1458 (pAL544, pAL597) | MG1655 lacIq ; vector-based overexpression of alsS (B. subtilis), alsD (Enterobacter aerogenes), adh (Leuconostoc pseudomesenteroides), dhaB1 (Klebsiella pneumonia MGH 78578), dhaB2 (K. pneumonia MGH 78578), dhaB3 (K. pneumonia MGH 78578), orfz (K. pneumonia MGH 78578), and orf2B (K. pneumonia MGH 78578) | 0.151 | 368 |

| Isobutyl acetate | JCL260 (pAL603, pAL676) | JCL260 (BW25113 F′ [traD36 proAB+ lacIq ZΔM15 TcR] ΔadhE ΔldhA ΔfrdBC Δfnr Δpta ΔpflB); vector-based overexpression of alsS (B. subtilis), ilvC, ilvD, kivd (L. lactis), adhA (L. lactis), and ATF1 (S. cerevisiae) | 17.2 | 332 |

| Isobutanol | JCL260 (pSA55, pSA69) | JCL16 ΔadhE ΔldhA ΔfrdBC Δfnr Δpta ΔpflB; vector-based overexpression of PDC6 (S. cerevisiae), ADH2 (S. cerevisiae), kivd (L. lactis), ilvC, ilvD, and alsS (B. subtilis) | 22 | 9 |

| JCL260 (pSA65, pSA69) | JCL260; vector-based overexpression of kivd (L. lactis), adhA (L. lactis), ilvC, ilvD, and alsS (B. subtilis) | 50.8 | 335 | |

| 1-Heptanol | ATCC 98082 ΔrhtA (pZS_thrO, pZE_LeuA*BCDKA6, a medium copy plasmid harboring ilvA and leuAfbr) | ATCC 98082 ΔrhtA; vector-based overexpression of thrAG433R (fbr), thrB, thrC, leuAG462D (fbr), H97A, S139G, N167G, P169A, leuB, leuC, leuD, kivd (L. lactis), ADH6 (S. cerevisiae), leuAfbr, and ilvA (B. subtilis) | 0.0802 | 14 |

| 1-Octanol | 0.002 | |||

| 3-Phenylpropanol | ATCC31884 (pZE_LeuA*BCDKA6) | ATCC 31884 (phenylalanine overproducer); vector-based overexpression of leuAG462D (fbr), H97A, S139G, N167G, P169A, leuB, leuC, leuD, kivd (L. lactis), ADH6 (S. cerevisiae) | 0.0041 | |

| 2-Methyl-1-butanol | CRS22 (pAFC3, pAFC46, pCS49) | BW25113 F′ [proAB+ lacIq ZΔM15 Tn10 (TcR)] ΔmetA Δtdh; vector-based overexpression of ilvG (Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium), ilvM (S. enterica serovar Typhimurium), ilvC (S. enterica serovar Typhimurium), ilvD (S. typhimurium), ilvA (C. glutamicum), thrABC | 1.25 | 11 |

| 3-Methyl-1-butanol | AL2 (pIAA11, pIAA13, pIAA16) | Second round NTG-created mutant of JCL16; vector-based overexpression of alsS (Bacillus subtilis), ilvC, ilvD, kivd (L. lactis), ADH2 (S. cerevisiae), leuAfbr, leuB, leuC, and leu D | 9.5 | 351 |

| 3-Methyl-1-pentanol | ATCC 98082 (pZS_thrO, pZE_LeuABCDKA6, pZAlac_tdcBilvGMCD) | ATCC 98082 ΔilvE ΔtyrB; vector-based overexpression of thrAG433R (fbr), thrB, thrC, leuAG462D (fbr),S139G, leuB, leuC, leuD, kivdV461A, F381L (L. lactis), ADH6 (S. cerevisiae), tdcB, ilvG, ilvM, ilvC, and ilvD | 0.7935 | 10 |

| 4-Methyl-1-pentanol | Same as 3-methyl-1-pentanol | Same as 3-methyl-1-pentanol except LeuAG462D, S139G, H97L and kivdV461A, F381L | 0.2024 | |

| 4-Methyl-1-hexanol | Same as 3-methyl-1-pentanol | Same as 3-methyl-1-pentanol except LeuAG462D, S139G, H97A, N167A and kivdV461A, F381L | 0.0573 | |

| 5-Methyl-1-heptanol | Same as 3-methyl-1-pentanol | 0.022 | ||

| 1-Pentanol | Same as 3-methyl-1-pentanol | Same as 3-methyl-1-pentanol except LeuAG462D and kivdV461A, M538A | 0.7505 | |

| Catechol | AB2834 (pKD136, pKD9.069A) | AB2834 ( F–tsx-352 glnV42(AS) λ– aroE353 malT352(λR); vector-based overexpression of tkt, aroF, aroB, aroZ (K. pneumoniae), and aroY (K. pneumoniae), | 2.0 | 317 |

| W3110 9923 (pJLBaroGfbr tktA, pTrc-ant3 | W3110 trpD9923; vector-based overexpression of tktA, aroGfbr, antA (Peudomonas aeruginosa), antB (P. aeruginosa), and antC (P. aeruginosa) | 4.47 | 326 | |

| cis,cis-Muconic acid | WN1 (pWN2.248) | KL7 (AB2834 serA::aroB-aroZ) lacZ::tktA-aroZ; vector-based overexpression of catA, aroY, serA, and aroFfbr | 36.8 | 369 |

| p-Hydroxybenzoic acid | JB161 (pJB2.274) | D2704 ((ΔtrpC-E)trpR tyrA Δ(pheA)) serA:: Ptac-aroA-aroL-aroC-aroB-KmR; vector-based overexpression of tktA, ubiC, serA, aroFfbr | 12 | 318 |

| p-Aminobenzoic acid (PABA) | PABA-25 | acs::PT7lac-pabAB (opt, Corynebacterium efficiens) ascF::PT7lac-pabAB (opt, C. efficiens) mtlA::PT7lac-pabAB (opt, C. efficiens) pflBA::PT7lac-pabC tyrR::PT7lac-aroFfbr | 4.8 | 328 |

| 4-Hydroxycoumarin | Strain D (pZE-EP-APTA and pCS-PS) | BW25113 F′ [proAB+ lacIq ZΔM15 Tn10 (TcR)]; vector-based overexpression of luc, entC, pfpchB, aroL, ppsA, tktA, aroGfbr, pqsD, and sdgA | 0.4831 | 327 |

| 2-Phenylethanol (PE) | JCL16 (pSA55) | JCL16; vector-based overexpression of kivd (L. lactis) | 0.149 | 9 |

| DCU4 (pCL1920-pheAfbr-aroFwt, pUC19-adh1-kdc) | DH5α; vector-based overexpression of pheAfbr , aroF, adh1 (S. cerevisiae S288c), and kdc (Pichia pastoris GS115) | 0.285 | 331 | |

| PAR-105 | BW25113(DE3) tyrR::PT7-aroFfbr-pheAfbr mtlA::PT7-ipdC (Azospirillum brasilense NBRC102289) acs::PT7-yahK ΔfeaB ΔtyrA | 0.842 | 26 | |

| 2-(4-Hydroxyphenyl)ethanol (4HPE) | PAR-104 | BW25113(DE3) tyrR::PT7-aroFfbr-tyrAfbr mtlA::PT7-ipdC (A. brasilense NBRC102289) acs::PT7-yahK ΔfeaB ΔpheA | 1.14 | |

| Phenyllactic acid (PLA) | PAR-58 | BW25113(DE3) tyrR::PT7-aroFfbr-pheAfbr acs::PT7-ldhA (C. necator JCM20644) mtlA:: PT7-ldhA (C. necator JCM20644) | 1.00 | |

| 4-Hydroxyphenyllactic acid (4HPLA) | PAR-3 | BW25113(DE3) tyrR::PT7-aroFfbr-tyrAfbr; acs::PT7-ldhA (C. necator JCM20644) | 1.48 | |

| Phenylacetic acid (PAA) | PAR-100 | BW25113(DE3) tyrR::PT7-aroFfbr-pheAfbr mtlA::PT7-ipdC (A. brasilense NBRC102289) acs::PT7-feaB ΔtyrA | 1.20 | |

| 4-Hydroxyphenylacetic acid (4HPAA) | PAR-102 | BW25113(DE3) tyrR::PT7-aroFfbr-tyrAfb mtlA::PT7-ipdC (A. brasilense NBRC102289) acs::PT7-feaB ΔyahK ΔpheA | 1.12 | |

| Styrene | NST74 (pSpal2At, pTfdc1Sc) | NST74 (aroH367 tyrR366 tna-2 lacY5 aroF394 (fbr) malT384 pheA101 (fbr) pheO352 aroG397 (fbr)); vector-based overexpression of PAL2 (Arabidopsis thaliana) and FDC1 (S. cerevisiae) | 0.26 | 329 |

| Styrene oxide | N74dASO (pTpal-fdc, pTKstyAB) | NST74 ΔtyrA; vector-based overexpression of FDC1 (S. cerevisiae), PAL2 (A. thaliana), styA (P. putida S12), and styB (P. putida S12) | 1.32 | 330 |

| Phenylethanethiol | N74dAPED (pTal-fdc, pTKnah) | NST74 ΔtyrA; vector-based overexpression of FDC1 (S. cerevisiae), PAL2 (A. thaliana), and nahAaAbAcAd (P. putida NCBI 9816) | 1.23 | |

| Phenol | PheBL21 (pTyr-a-TPL, pTyr-b) | BL21(DE3); vector-based overexpression of aroK, tyrC, aroGA146N, and tyrAA354V, M53I, tpl (Pasteurella multocida 36950), ppsA, tktA, and aroF; vector-based regulated expression of anti-csrA synthetic sRNA, anti-tyrR synthetic sRNA | 3.79 | 319 |

| Fatty acids and derivatives | ||||

| Free fatty acids (FFA) | RB03 (pTHfadBA.fadM-) | MG1655 fadR atoCc ΔarcA Δcrp::crp* ΔadhE Δpta ΔfrdA ΔfucO ΔyqhD ΔfadD; vector-based overexpression of fadB, fadA, and fadM | ∼7 | 12 |

| Fatty acid ethyl esters (FAEEs) | TOP10 (pMicrodiesel) | TOP10; vector-based overexpression of pdc (Z. mobilis), adhB (Z. mobilis), and atfA (Acinetobacter baylyi) | 1.28 | 322 |

| Heptadecene (and other C13–C17 alkanes and alkenes) | MG1665 (pCL1920 derivative harboring PCC7942_orf1594, pACYC derivative harboring PCC7942_orf1593) | MG1665; vector-based overexpression of PCC7942_orf1593 (Synechocystis elongates) and PCC7942_orf1594 (S. elongates) | 0.042 | 321 |

| Short-chain alkanes (C10-C12) | GAS3 (pTacCer1FadD, pTrcAcR′TesA(L109P)) | W3110 ΔfadE ΔfadR PfadD::Ptrc; vector-based overexpression of CER1 (A. thaliana), fadD, acr (C. acetobutylicum), and tesA (mutant leaderless version) | 0.580 | 15 |

| Propane | ProFΔA (pET-TPC4, pCDF-ADO, pACYC-petF-fpr) | BL21(DE3) ΔyqhD Δahr; vector-based overexpression of tes4 (Bacteroides fragilis), sfp (B. subtilis), car (Mycobacterium marinum), ADO (Prochlorococcus marinus), petF (Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803), and fpr (E. coli) | 0.032 | 18 |

| Secondary metabolites | ||||

| Isoprene | Rosetta (pJF-kIspS, pET28 derivative harboring hmgS, hmgR, atoB, fni, mk, pmk, and pmd) | Rosetta; Vector-based overexpression of kIspS (opt, Peuraria montana), hmgS (Enterococcus faecalis), hmgR (E. faecalis), atoB (E. coli), fni (Streptococcus pneumoniae), mk (S. pneumoniae), pmk (S. pneumoniae), and pmd (S. pneumoniae) | 0.32 | 373 |

| Geraniol | GEOL(0.5K) (pSNAK, pT-GPES(0.5K)) | MGΔyjgB (MG1655 ΔyjgB); vector-based fine-controlled overexpression of mvaK1 (Staphylococcus pneumoniae), mvaK2 (S. pneumoniae), mvaD (S. pneumoniae), idi (E. coli), mvaE (E. faecalis), mvaS (E. faecalis), ispA (mutated, E. coli), and tGES (truncated, Ocimum basilicum) | 1.119 | 499 |

| Limonene | 1pC (pJBEI-6409) | DH1; vector-based overexpression of atoB (E. coli), HMGS (opt, Staphylococcus aureus) and HMGR (opt, S. aureus), MK (Saccharomyces cerevisiae), PMK (S. cerevisiae), PMD (S. cerevisiae), idi (E. coli), trGPPS (opt, truncated, Abies grandis), and LS (opt, Mentha spicata) | 0.435 | 367 |

| Perillyl alcohol | 1pA+P (pJBEI-6410, pBbB8k-P450) | DH1; vector-based overexpression of atoB (E. coli), HMGS (opt, Staphylococcus aureus) and HMGR (opt, S. aureus), MK (Saccharomyces cerevisiae), PMK (S. cerevisiae), PMD (S. cerevisiae), idi (E. coli), trGPPS (opt, truncated, Abies grandis), LS (opt, Mentha spicata), ahpG (opt, Mycobacterium HXN 1500), ahpH (opt, M. HXN 1500), and ahpI (opt, M. HXN 1500) | 0.1 | |

| α-Farnesene | ispALaFS-NA (pTispALaFS and pSNA) | DH5α; vector-based overexpression of FS (opt, Malus x domestica)-(GGGGS)2-ispA (E. coli), mvaE (E. faecalis), mvaS (E. faecalis), mvaK1 (S. pneumoniae), mvaK2 (S. pneumoniae), mvaD (S. pneumoniae), and idi (E. coli) | 0.380 | 500 |

| Amorphadiene (Artemisinic acid precursor) | DH10B (pMevT, pMBIS, pADS) | DH10B; vector-based overexpression of atoB (E. coli), ERG13 (S. cerevisiae), tHMGR (truncated, S. cerevisiae) ERG12 (S. cerevisiae), ERG8 (S. cerevisiae), MVD1 (S. cerevisiae), idi (E. coli), ispA (E. coli), and ADS (Artemisia annua L) | 0.024 | 372 |

| B86 (pAM52, pMBIS, pADS) | DH1; vector-based overexpression of atoB (E. coli), mvaS (S. aureus), mvaA (S. aureus), ERG12 (S. cerevisiae), ERG8 (S. cerevisiae), MVD1 (S. cerevisiae), idi (E. coli), ispA (E. coli), and ADS (Artemisia annua L) | 27.4 | 473 | |

| Artemisinic acid | DH1 (pAM92, pCWori-A13AMO-aaCPRct) | DH1; vector-based overexpression of A13AMO (opt, N-terminal transmembrane domain engineering on CYP71AV1, A. annua), aaCPRct (opt, A. annua), atoB (E. coli), ERG13 (S. cerevisiae), tHMGR (truncated, S. cerevisiae) ERG12 (S. cerevisiae), ERG8 (S. cerevisiae), MVD1 (S. cerevisiae), idi (E. coli), ispA (E. coli), and ADS (Artemisia annua L) | 0.1 | 474 |

| Taxadiene | Strain #26 (EDE3Ch1TrcMEPp5T7TG) (pSC101 derivative harboring TS and GGPPS) | K-12 MG1655 ΔrecA ΔendA (DE3) Ptrc-dxs-idi-ispDF; vector-based overexpression of TS (Taxus brevifolia) and GGPPS (Taxus canadensis) | 1 | 346 |

| Taxadien-5α-ol | Strain #26 (EDE3Ch1TrcMEPp5T7TG)-At24T5αOH-tTCPR (pSC101 derivative harboring TS and GGPPS, p10T7At24T5 αOH-tTCPR) | K-12 MG1655 ΔrecA ΔendA (DE3) Ptrc-dxs-idi-ispDF; vector-based overexpression of TS (Taxus brevifolia), GGPPS (Taxus canadensis), At24T5αOH (truncation at 24th amino acid residue, T5αOH, Taxus cuspidate), and tTCPR (74 amino acids truncated TCPR, T. cuspidate) | 0.6 | |

| Levopimaradiene | MG1655 ΔendA ΔrecA (p10TrcMEP, pTrcGGPPS*-CRT) | MG1655 ΔendA ΔrecA; vector-based overexpression of dxs, idi, ispD, ispF, GGPPSS239C, G295D (Sequences for N-terminal 98 amino acids removed, T. canadensis) and LPSM593I, Y700F (Sequences for N-terminal 40 amino acids removed, Ginkgo biloba) | 0.7 | 423 |

| Phytoene | JM101 (pACCRT-EB, pHP11) | JM101; vector-based overexpression of crtE (Erwinia uredovora), crtB (E. uredovora), and ipp (Haematococcus pluvialis) | < 0.005 | 501 |

| Lycopene | JM101 (pACCRT-EIB, pHP11) | JM101; vector-based overexpression of crtE (Erwinia uredovora), crtB (E. uredovora), crtI (E. uredovora), and ipp (Haematococcus pluvialis) | < 0.01 | |

| BW18302 (p2IDI, pPSG184) | BW18302 (F– λ– lacX74 glnL2001); vector-based, controlled expression of glnAp2-idi, glnAp2-pps | 0.16 | 343 | |

| LYC010 | CAR001 (ATCC 8739 ldhA::M1-93::crtEXYIB (Pantoea agglomerans)::ldhA M1-37::dxs M1-37::idi) ΔcrtXY M1-46::sucAB M1-46::talB M1-46::sdhABCD RBSL9::crtE RBSL12::dxs RBSL7::idi | 3.53 | 323 | |