Abstract

Wound healing is a highly coordinated spatiotemporal sequence of events involving several cell types and tissues. The process of wound healing requires strict regulation, and its disruption can lead to the formation of chronic wounds, which can have a significant impact on an individual’s health as well as on worldwide healthcare expenditure. One essential aspect within the cellular and molecular regulation of wound healing pathogenesis is that of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and oxidative stress. Wounding significantly elevates levels of ROS, and an array of various reactive species are involved in modulating the wound healing process, such as through antimicrobial activities and signal transduction. However, as in many pathologies, ROS play an antagonistic pleiotropic role in wound healing, and can be a pathogenic factor in the formation of chronic wounds. Whilst advances in targeting ROS and oxidative stress have led to the development of novel pre-clinical therapeutic methods, due to the complex nature of ROS in wound healing, gaps in knowledge remain concerning the specific cellular and molecular functions of ROS in wound healing. In this review, we highlight current knowledge of these functions, and discuss the potential future direction of new studies, and how these pathways may be targeted in future pre-clinical studies.

Subject terms: Molecular medicine, Medical research

This review highlights the cellular and molecular mechanisms in which ROS are involved in normal wound healing and chronic wound pathogenesis, as well as recent advances in therapeutic methods.

Introduction

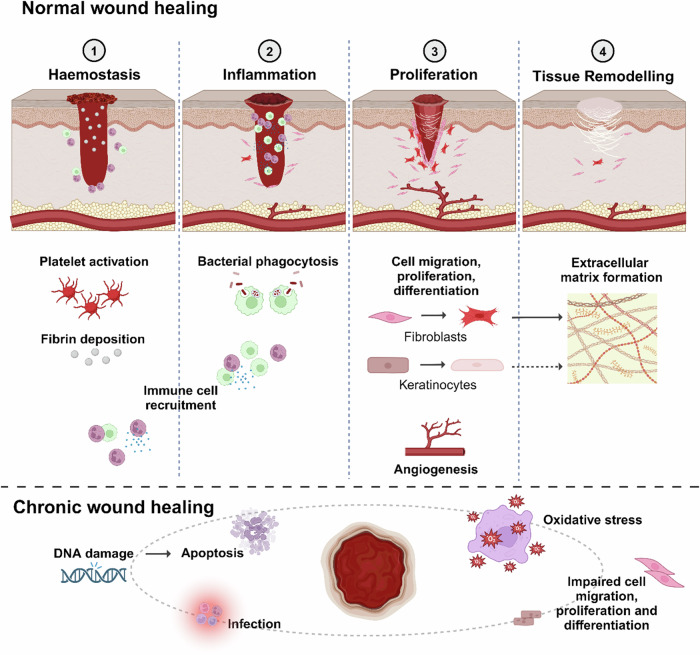

Dermatological would healing is the tightly coordinated response of restoring skin tissue integrity and homeostasis following damage. Involving numerous immune and non-immune cell types as well as associated cytokines, growth factors, and extracellular components – in a healthy, acute response – orderly wound healing consists of the four consecutive stages of haemostasis, inflammation, proliferation, and tissue remodelling1,2. Briefly, during the haemostasis phase, platelets are recruited or leak out of damaged vasculature and with the simultaneous activation of the coagulation cascade and formation of fibrin fibres, form a clot at the wound site3. Next, during inflammation, various immune cells migrate to the wound site and utilise phagocytotic effects to protect against infection. Additionally, these immune cells also release pro-inflammatory cytokines and growth factors to induce the activation of fibroblasts, keratinocytes, and endothelial cells, as well as prepare the wound bed for the formation of granulation tissue4,5. During the proliferation phase, granulation tissue is formed and damaged tissue is replaced. At the remodelling phase, connective tissue, replacement epithelium, and scar tissue are all formed6.

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) play an essential pleiotropic role in wound healing, and several ROS are involved in the wound healing milieu (Fig. 1). These include superoxide (O2.−), hydroxyl radicals (.OH) and ions (OH−), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), and peroxide (.O2−2)7. ROS are implicated in numerous pathophysiological functions within the wound healing process such as anti-bacterial activities8,9, as well as acting as secondary messengers in signalling cascades to modulate chemotaxis, angiogenesis, cell growth and migration, stem cell fate, and extracellular matrix (ECM) deposition7,10–13.

Fig. 1. Summary of ROS activities during the wound healing process.

Stages of wound healing with illustrations of the various beneficial roles that physiological levels ROS play in the respective stages, in addition to the roles excessive ROS and oxidative stress play in chronic wound pathogenesis. During the haemostasis stage, NO prevents platelet adhesion to vessel walls, whilst ROS such as O2.− increases fibrin deposition, and H2O2 induces the recruitment of monocytes and neutrophils. During inflammation, ROS play important roles in activating immune cells, as well as eliminating pathogens and preventing infection. During the proliferation stage, ROS play vital roles in modulating numerous cellular signalling pathways to promote the proliferation, migration, and differentiation of fibroblasts and keratinocytes, as well as angiogenesis, ultimately promoting collagen remodelling and extracellular matrix formation. Oxidative stress caused by excessive levels of ROS contribute to the pathogenesis of chronic wounds in various ways, including by increasing apoptosis, promoting pathogen expansion and thus infection, as well as impairing the correct modulation of cell signalling pathways involved in cell dynamics.

Importantly, both the levels and timing of ROS production need to be tightly regulated for efficient wound healing7. Too high levels caused by either excess ROS production or impaired detoxification lead to oxidative stress, elevated tissue damage, and pathophysiological stalling14,15, whilst too low levels impede cellular and molecular processes of wound healing which are dependent on ROS-mediated signal transduction7 – ultimately leading to the formation of chronic wounds. Highlighting the delicate and complex balance required, inhibition of ROS has been shown to impair wound healing in numerous animal models16–23, whilst improvements in antioxidant capabilities have been shown to be beneficial in treatments of chronic and diabetic wounds14,24,25. As such, due to the multifaceted nature of chronic wound pathogenesis and susceptibility to abnormalities in ROS balance, interest in the role of ROS in wound healing, as well as the potential applicability of targeting ROS therapeutically, has grown significantly in recent years14. However, it will be essential to further elucidate the precise signalling pathways and mechanisms in which ROS is involved in wound healing. Thus, in this review, we discuss the current knowledge of the cellular and molecular roles of ROS in wound healing and chronic wound pathogenesis, as well as evaluate recent advances in pre-clinical therapeutic approaches targeting ROS and oxidative stress.

Physiological functions of ROS

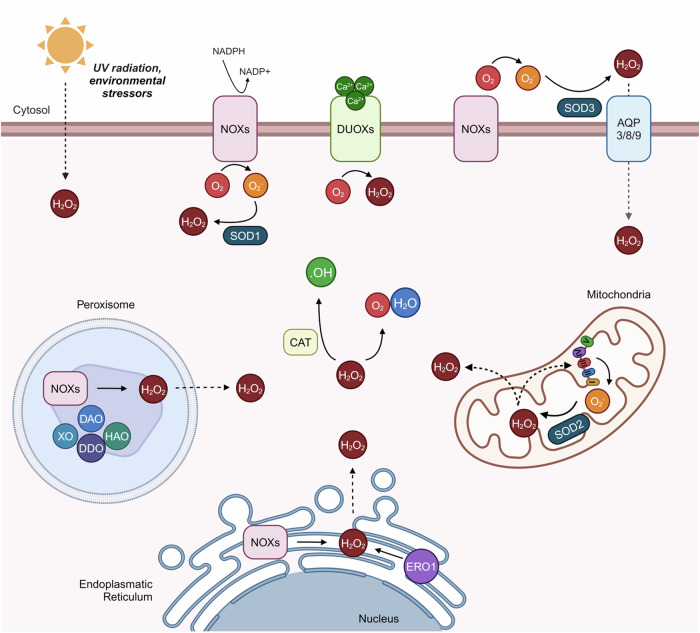

ROS encompass both free-radical or non-radical derivative (peroxides) oxygen intermediates generated by plasma membrane proteins26 (Fig. 2). Physiologically, as well as in pathologies such as wound healing, H2O2 is recognised as the predominant paracrine ROS secondary messenger involved in signalling cascades27,28. This is due to the fact that H2O2 can quickly and readily diffuse through cell membranes, primarily through aquaporins (AQPs)29,30, as well as between neighbouring cells through gap junctions – hemichannels composed of connexins which facilitate the transfer of molecules 1–3 kDa large such as ROS between cells to propagate oxidative signals31. Additionally, ROS can directly modulate post-transcriptional gene regulation by interacting and reversibly oxidising thiolate groups and methionine32, as well as activating mitosis-related signal transduction pathways8,33,34 and electron-rich cysteine residues35.

Fig. 2. Cellular ROS homeostasis.

Schematic diagram depicting the various ROS-generating pathways occurring within cells. At the cell membrane, O2.− is converted from O2 in an NADPH-mediated reaction by NOXs, which is then converted to H2O2 by SOD1. H2O2 can also be produced from O2 in a Ca2+-mediated reaction by DUOXs or by UV radiation or other environmental stressors. Extracellular H2O2 can also be imported into cells through AQPs 3, 8, or 9. Within cells, O2.− leaks from the ETC during oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) and is converted into H2O2 by SOD2/MnSOD2 and effluxed out of mitochondria into the cell cytosol. Additionally, H2O2 can be produced in the ER by either ERO1 or NOXs and effluxed into the cytosol, as can H2O2 produced by NOXs within peroxisomes. XO, DAO, DDO, and HAO are also produced in peroxisomes. Within the cell cytoplasm, H2O2 can be detoxified into H2O and O2 as well as .OH by CAT. ER endoplasmic reticulum, SOD superoxide dismutase, AQP aquaporin, CAT catalase, XO xanthine oxidase, DAO D-amino acid oxidase, HAO 2-hydroxy acid oxidase, ERO ER oxidoreductin.

The main sources of intracellular H2O2 are NADPH oxidases (NOXs) and dual-oxidases (DUOXs)36–38, in conjunction with superoxide dismutases (SOD), as well as at the mitochondrial electron transport chain (ETC)39,40 – highlighting an important aspect of mitochondria within wound healing41. Collectively, NOXs and the ETC generate roughly 85% of H2O2, with the remaining production deriving from oxidases in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and peroxisomes, as well as from cumulative environmental stressors such as UV or ionising radiation8,40,42,43. Additionally, membrane-bound NOXs are also responsible for producing .O2.− utilised in antimicrobial activities44. Other ROS are produced by cytosolic enzymes such as cyclooxygenase45, or during lipid metabolism within peroxisomes46.

As previously mentioned, whilst low to moderate physiological levels of ROS are beneficial for several processes of wound healing pathophysiology, excess ROS can be deleterious. To counteract these harmful effects, a variety of antioxidant enzymes play vital roles in maintaining ROS levels, termed redox balance. These include peroxiredoxins47 such as catalase (CAT)48, glutathione peroxidases49,50, and mitochondrial nicotinamide nucleotide transhydrogenase (NNT)51, which act as ‘sinks’ to remove H2O2 and maintain non-deleterious physiological levels. In addition, SOD, of which there are four isoforms in humans, are antioxidant metalloproteinases which regulate levels of O2.−. In particular, the mitochondrial SOD (MnSOD/SOD2) converts .O2.− into H2O2, which is less reactive than .O2.− and so can readily be used for cellular signalling. As SOD2 is induced by hypoxia and subsequent HIF-1α activation, it is highly upregulated after wounding52,53.

Oxidative stress is the state induced by an overbalance in the form of excess ROS, and can be a causative factor in chronic wound formation15, as well as in the pathogenesis of other diseases including cancers, cardiovascular diseases, Parkinson’s, obesity, and other clinically-relevant age-related diseases54–57. In the context of wound healing, oxidative stress can lead to the existence of a prolonged pro-inflammatory environment as well as dysregulated re-epithelialisation, as discussed in the following sections58.

Finally, another important free radical is nitric oxide (NO), which is a reactive nitrogen species (RNS) involved in vascularisation, inflammation, and antimicrobial activities in wound healing59–61. Most importantly with regards to wound healing, NO plays an important role in pathogen clearance during the inflammatory stage, and this NO is produced by the inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) isozyme62,63. Here, NO targets both gram-negative and -positive bacteria through aberrant peroxidation and the production of ONOO-, although this can be hindered by its short half-life64,65. Alternatively, lower levels of NO, produced by endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS), play important roles in preventing platelet adhesion to vessel walls during haemostasis66, and for both keratinocyte and fibroblast proliferation, motility, and differentiation at the later proliferation and tissue remodelling stages of wound healing67–69. Insufficient production of NO has been shown to be a significant factor in the development of chronic wounds such as diabetic foot ulcer (DFU), primarily due to resultant impaired antimicrobial activities63,70.

ROS and immune cell function during wound healing

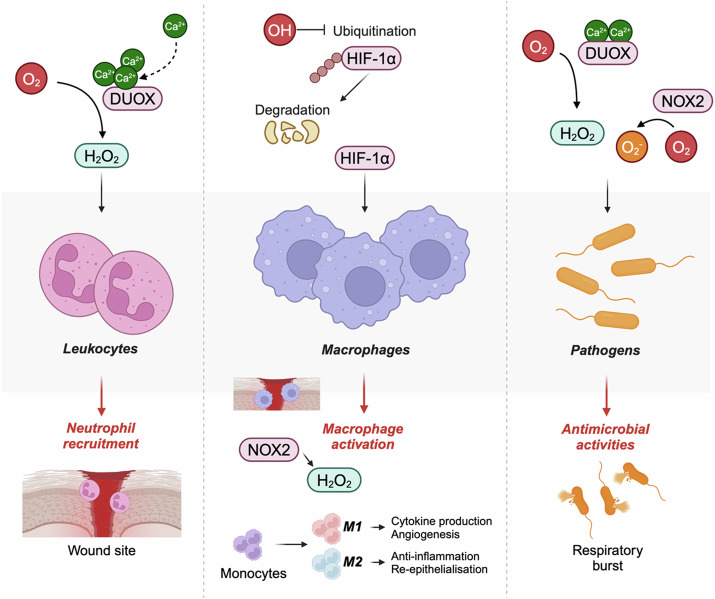

ROS and leucocyte recruitment

Immediately following skin wounding there is a peak in ROS production to ~0.5–50 μM. Here, ROS are utilised to simultaneously recruit leucocytes to the wound site, as well as to induce vasoconstriction16,17,71. Through studies of ROS dynamics in embryonic zebrafish wounding, Niethammer et al. demonstrated for the first time that epithelial cell production of H2O2 preceded the recruitment of leucocytes, and in particular that DUOX was the main source of H2O2 at the wound site and inducer of rapid leucocyte recruitment from long distances17. In embryonic Drosophila, the activation of DUOX and subsequent H2O2 production was shown to be triggered by wound-induced calcium (Ca2+) flashes, where Ca2+ binds to an EF hand Ca2+-binding motif of DUOX72.

Expanding on this work, Yoo et al. demonstrated the cystine residue C466 on the Src family kinase Lyn as being the direct target of H2O2 to induce neutrophil recruitment to the wound site, mediated through ERK signalling16. Alternatively, the activation of DUOXs, with subsequent H2O2 production and neutrophil recruitment, can also be activated by ATP through the P2Y receptor (P2YR)/phospholipase C (PLC) Ca2+ signalling pathway following wounding in embryonic zebrafish tailfins73.

ROS and macrophage function

Macrophages play important roles within the wound healing process, including in antimicrobial activities, as well as inflammation, angiogenesis, anti-inflammation, re-epithelialisation, and tissue resolution74. ROS-induced HIF-1α stabilisation leads to the activation of macrophages in the early stages of wound healing, and promotes metabolic reprogramming towards glycolysis75,76, as well as increased angiogenesis76. Importantly, both NOX1- and NOX2-produced ROS are required for the activation and differentiation of monocytes into proinflammatory M1 and anti-inflammatory M2 macrophages77. Additionally, in atherosclerotic lesions, NOX4-produced ROS drives monocyte and macrophage cell death77 – a vital step required to prevent prolonged inflammation in wound healing78.

Although NOXs are essential for macrophage activation, they have been shown to be dispensable for M1 macrophage-mediated proinflammatory cytokine production79. Instead, pro-inflammatory cytokine production and inflammasome activation in macrophages predominantly relies on the regulation of the Nrf2 response80, which can be primarily activated by glutathione or thioredoxin systems, as well as to a lesser extent NOXs81. Other important pro-inflammatory signalling pathways regulated by ROS – and in particular H2O2 – include p38-MAPK-mediated NF-κB/HIF-1α82,83, and JAK-STAT pathways84.

Monoamine oxidases (MAOs) – a mitochondrially-located enzyme responsible for catalysing the oxidative deamination of H2O285 – is upregulated by the M2 macrophage-activating IL-13 and IL-4, or LPS signals. This process is mediated through JAK signalling pathways and is thus important in anti-inflammation and re-epithelialisation during wound healing86. Indeed, MAO inhibitors significantly reduced H2O2 levels and NF-κB/TNFα activation to impair apical migration and proliferation of junction epithelium in a rat chronic wound model87. Alternatively, DUOX-induced ROS stimulated the activation of macrophages and promoted epithelial proliferation in a JNK-dependent manner during Drosophila epithelial disc healing88.

Of note, whilst many studies have demonstrated the importance of ROS and macrophage function in other pathologies and physiological contexts, few have specifically investigated this link within wound healing pathophysiology89. Importantly, the majority of studies in this area used the oversimplistic M1 and M2 macrophage classifications, whereas in recent years advancements have been made to study the more elaborate classifications of macrophages in the general immunology setting90, and this should thus be applied to the macrophages in wound healing setting91. Single-cell RNA-sequencing (scRNAseq) and other advanced omics-based techniques have in recent years significantly powered the investigation of the roles of specific cell lineages, including macrophage lineages, in different stages of wound healing76,92. As such, future investigations seeking to elaborate on the roles of ROS dynamics in wound healing would greatly benefit from the utilisation of these techniques.

ROS and antimicrobial activities

One of the major factors that leads to the formation of chronic wounds is that of prolonged inflammation and pathogenic infection, which can hamper angiogenesis, stem cell function, and extracellular matrix remodelling93. During acute wound healing, immune cells are required to eliminate pathogens and prevent infection at the wound site, and ROS play an essential role in this function94 (Fig. 3). Here, extracellular H2O2 – generated by DUOXs in response to the increased Ca2+ binding following wounding – promotes the production of bacteria-destroying ROS after reacting with halide or thiocyanate95,96. In the absence of this function, polymicrobial biofilms form, which can lead to the expansion of a pathogenic environment and ultimately the stalling of the wound healing response and thus chronic wound formation97.

Fig. 3. Roles of ROS utilisation in immune cells during wound healing.

Schematic diagram depicting the roles of ROS in neutrophil and macrophage recruitment, as well as in antimicrobial activities during the inflammatory stage of wound healing. Here, wounding-induced Ca2+ flashes lead to the upregulation of DUOX-mediated H2O2 production, stimulating the recruitment of leukocytes to the wound site. Additionally, OH prevents the ubiquitination and subsequent degradation of HIF-1α, leading to increased HIF-1α signalling and macrophage activation, primarily mediated through H2O2 signalling. Finally, immune cells utilise various reactive oxygen species, including O2−, to destroy pathogens through respiratory bursts.

In a dual action, peroxidases such as myeloperoxidase and eosinophil peroxidase convert H2O2 into other oxidants such as hypochlorous acid, which is then used by neutrophils in antibacterial activities98,99. This process additionally prevents the toxic build-up of H2O2 which can occur in the early stage of wound healing following leucocyte recruitment, where H2O2 levels are highest100,101.

Macrophages also play an important role in clearing pathogens during wound healing through phagocytosis. Here, NOX2-derived O2.- is released into phagocytotic vesicles to kill internalised pathogens through respiratory bursts89.

Role of ROS in re-epithelialisation

ROS in platelet aggregation and angiogenesis

Moderate amounts of ROS (up to a 40% increase) are required for the reduction in platelet adhesion to collagen surfaces and thus platelet activation102,103. In light of this, and conversely, whilst ROS is known to accelerate platelet function in wound healing, transfer of platelet-derived mitochondria into diabetic mice improved wound healing in part by preventing the overexpression of ROS104. Importantly, H2O2 induces the recruitment of vascular smooth muscle cells to the wound site11,105.

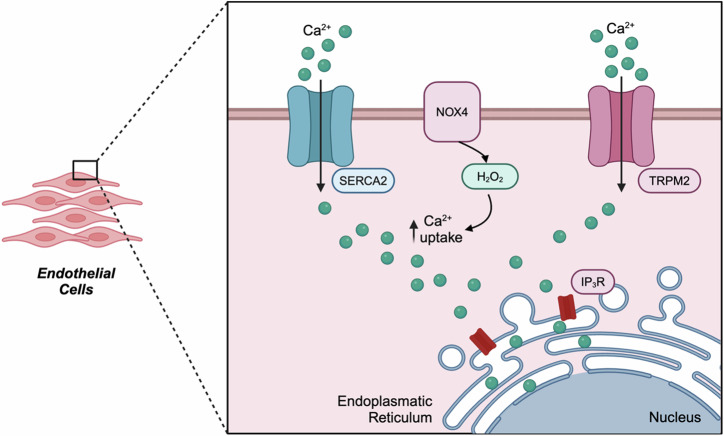

As previously mentioned, NO plays an important role in angiogenesis during wound healing. Here, elevated NO production – as a result of increased activation of NOXs, in particular NOX4 – leads to the stabilisation of HIF-1α and thus promotion of endothelial cell (EC) survival, migration, differentiation, and therefore neovascularisation64,106–108. Highlighting this, near-infrared (NIR)-triggered NO production supressed the proteasomal degradation of HIF-1α. Here, by preventing the interaction of HIF1-α with E3 ubiquitin ligases, both VEGF and CD31 expression was enhanced in ECs, coinciding with increased cell proliferation and migration – collectively accelerating wound healing in diabetic mice64. H2O2 produced by NOX4 also activated both the TRPM2109, and SERCA2 channels110 to promote Ca2+ uptake and thus improve EC activity (Fig. 4). In wound healing and other hypoxic-state pathologies such as brain ischemia, these ROS-derived effects on ECs are associated with phosphorylation-dependent activation of various signalling molecules including those of ERK, c-JUN, MAPK, AKT, SMAD, and JNK111.

Fig. 4. ROS and endothelial cell function.

Schematic depicting how H2O2 produced by NOX4 increases Ca2+ uptake into endothelial cells through elevated SERCA2 and TRPM2 channel activity, subsequently leading to increased endothelial cell division and migration – thereby promoting angiogenesis.

Finally, production of O2·− by both NOX2 and NOX4 also leads to the upregulation of VEGF110,112. In particular, NOX2 was demonstrated to stimulate VEGFR2 and angiogenesis in wounds through the activation of NF-κB by 2-deoxy-D-ribofuranose 1-phosphate (dRP) – an intermediate of pyrimidine metabolism. This NOX2-derived ROS was primarily generated by both platelets and macrophages13,113.

H2O2 mediated cell signalling and re-epithelialisation

Many cytoskeletal proteins possess cysteines which are highly sensitive to oxidation114, and in a complementary fashion, production of H2O2 occurs primarily in leading edge cells involved in re-epithelialisation115. In particular, H2O2 promotes actin cytoskeleton reorganisation and cell migration by directly oxidising actin and actin-binding proteins116, as well as activating numerous cell signalling pathways associated with re-epithelialisation.

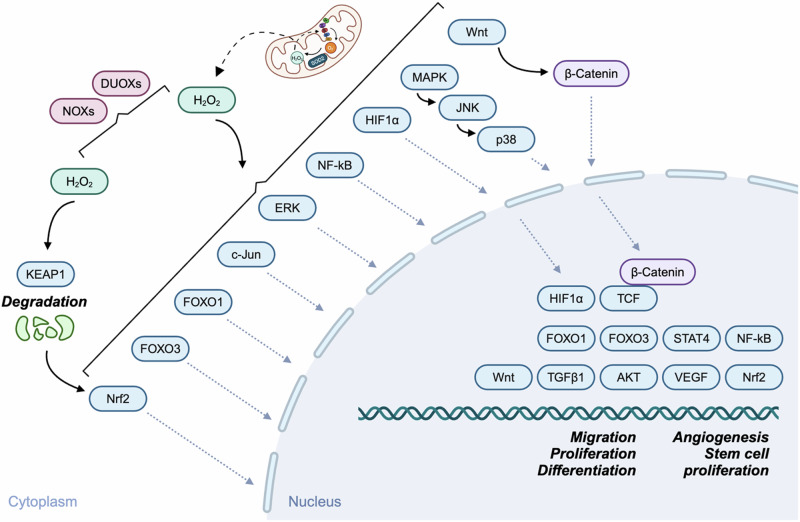

As discussed previously, there are several mechanisms in which ROS-mediated signalling cascades are initiated in wound healing (Fig. 5). Indeed, ROS production required for both immune cell function and re-epithelialisation share similar stimuli. In one key example, Hunter et al. demonstrated in Drosophila embryo healing that mitochondrially-derived H2O2 – produced downstream of intracellular Ca2+ bursts – led to the polarisation of the actomyosin cytoskeleton and E-cadherin distribution around the wound to promote wound healing117. Specifically, this action occurred via oxidation of the Src kinase Src42, and supported results from a previous study in which mitochondrial ROS (mtROS) was produced downstream of Ca2+ bursts following wounding118. In addition to Ca2+-mediated activation, DUOX can also be activated downstream of extracellular ATP-activated purinergic receptors119–121.

Fig. 5. ROS and re-epithelialisation.

Schematic showing the various signalling molecules and pathways which are modulated by ROS to regulate re-epithelialisation during wound healing. H2O2 produced by either NOXs or DUOXs, or derived from mitochondria, stimulate numerous cell signalling pathways which ultimately lead to the upregulation of processes to accelerate wound healing – such as cell migration, proliferation, differentiation, angiogenesis, or stem cell propagation.

One cell signalling pathway regulated by wounding-induced ROS is that of c-JUN. Here, the inhibition of wounding-induced ROS accumulation significantly inhibited healing in planarian worms by preventing F-actin reorganisation and epithelial cell rearrangements – mediated through c-JUN activation at the wound site122. Separately, ROS-mediated activation of c-JUN also accelerated wound healing in diabetic rats through increases in angiogenesis and re-epithelialisation123, whilst NOX-produced H2O2-activation of the JNK pathway increased epithelial cell proliferation in adult zebrafish tailfin healing19.

Alternatively, H2O2 also regulates MAPK signalling during wound healing – namely, through thioredoxin (Trx) oxidation and PI3K/AKT1-Ask1-MAP3K-mediated activation of JNK and p3822,26,124. Interestingly, in a study investigating the interplay between ROS and AKT signalling in Drosophila regeneration, the importance of nutrient sensing and metabolism in this pathway was highlighted125. Here, ROS-mediated phosphorylation of Ask1 at Ser38 induced p38-mediated regeneration in a nutrient-sensitive insulin signalling manner, supporting similar findings in studies of stress-induced regeneration in the gut126. As metabolic regulation of fibroblasts and keratinocytes during re-epithelialisation is known to be important127, future studies should aim to further investigate the role of the MAPK and other relevant signalling pathways.

Another pathway that H2O2 has been shown to be important during the proliferation stage of zebrafish regeneration is that of hedgehog signalling19,128,129. A recent paper using the zebrafish tailfin regeneration model demonstrated that Sonic hedgehog (Shh) – a key signalling protein in the hedgehog signalling cascade – acted downstream of NOX to increase SOD activity and H2O2 production in the early stage of tailfin regeneration, most likely due to SOD oxidation130. Interestingly, although not fully elaborated on, the authors also demonstrated binding sites for HIF1α, STAT3, and NF-κB in Shha, suggesting that this kinase may additionally act on these factors to regulate redox balance during wound healing130. Importantly, Hedgehog signalling acts in close synergy to canonical Wnt signalling in regeneration as well as other pathological contexts129,131. In a separate study, NOX-induced H2O2 activated Wnt/β-catenin signalling and induced FGF20 transcriptional activation to promote epidermal regeneration18. Canonical Wnt signalling and mitochondrial H2O2 production was also downregulated in a mouse model with TFAM KO, with subsequent defects in epidermal differentiation due to the inhibition of Notch signalling132.

As well as its previously mentioned functions during the inflammation stage of wound healing, NF-κB has been shown to play significant roles during re-epithelialisation. Of note, early ROS signalling following embryonic zebrafish tailfin amputation led to the activation of NF-κB as well as promoter activation of vimentin. Here, vimentin promoted collagen formation and organisation133. Through serine/tyrosine phosphorylation and ubiquitination, H2O2 acts as a regulator of IκB kinases by inducing their proteolytic degradation134,135, which subsequently activates NF-κB and therefore promotes angiogenesis and re-epithelialisation. NF-κB is also directly regulated by H2O2-oxidation of cysteine residues in its DNA-binding region136. ROS has also been shown to increase the expression of TGF-β1 signalling, with downstream effects including elevated expression of collagen, fibronectin, bFGF, and matrix production104,137. As mitochondria are important in both TGF-β1 signalling and collagen organisation138, as well as that of general ROS regulation during wound healing, future studies should aim to explore the potential link between these factors. Indeed, the link between ROS and TGF-β1-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) has been demonstrated in endometrial cell pathology139.

H2O2 was shown to accelerate re-epithelialisation in embryonic zebrafish tailfins following wounding via the Src family kinase (SFK) FYN140. Although not confirmed in the particular study, FYN is known to be involved in keratinocyte differentiation141,142. Of note, this study confirmed findings from other studies whereby wounding led to the activation of Ca2+, ERK, and H2O2-mediated signalling cascades independently of each other140.

FOXO are transcription factors important in wound healing, and can either be activated by direct cysteine oxidisation, or in response to upstream redox signalling143. In particular, FOXO1 regulates cell cycle progression, apoptosis, and angiogenesis144,145, and promoted both in vivo and in vitro wound healing by preventing oxidative stress in keratinocytes via the upregulation of GPX-2 and GADD45α – thus maintaining TGF-β1 mediated migration and apoptosis inhibition146. Additionally, low level (10 µM) H2O2 treatment induced JNK-mediated FOXO3a translocation and activation to promote AKT-mediated stem cell proliferation, which when transplanted, increased re-epithelialisation and angiogenesis in wounded mice147. Here, H2O2 promoted the production of CAT, SOD2, GPX1, and GPX2, collectively increasing stem cell proliferation and preventing oxidative stress.

Nrf2 is a cytoprotective transcription factor which is upregulated in wound healing and acts to restore redox balance by increasing levels of various antioxidants148,149. In physiological conditions, Nrf2 is ubiquitinated and therefore inactivated by KEAP1. However, oxidation of cysteine residues on KEAP1 – including Cys151, Cys273, and Cys288 – by H2O2 induces a conformational change in KEAP1 and stimulates the activation of Nrf2150. Although not studied specifically at the molecular level, the antioxidant activities of Nrf2 play important roles in wound healing – regulating apoptosis, metabolism, autophagy, angiogenesis, as well as cell proliferation and migration151. Various studies have attempted to utilise Nrf2-modulating compounds for chronic wound treatment152–157. However, more research into the specific molecular mechanisms is required in order to further elucidate the specific cellular and molecular role of Nrf2 in wound healing pathophysiology.

Finally, DUOX1-mediated H2O2 production was also shown to be important for peripheral sensory axon reinnervation in zebrafish tailfin wound healing – highlighting another import role that ROS play, even in more uncommonly studied aspects of wound healing158.

Interestingly, by comparing ROS expression in both wound healing (early stage, lower levels) and regeneration (later stage, elevated levels) in planarians, Van Huizen et al. demonstrated that different levels of ROS act upstream of signalling pathways in a threshold-dependent manner to dictate the type of response required122. Similar results were found when investigating zebrafish, whereby simple wound healing required only early accumulation of ROS for JNK pathway activation, whilst injuries which necessitated new tissue formation required sustained H2O2 production, activating apoptosis pathways as well as JNK19,130.

Chronic wounds – redox balance abnormalities and current advancements in treatment strategies

A balanced state of oxidative stress is essential for normal wound healing. While physiological levels of ROS are required in the normal transition between wound healing phases, as previously described, an overproduction of ROS has deleterious effects and can hinder wound healing159. Multiple molecular mechanisms can explain this effect. For example, healing can be hindered by increased tissue damage, via opposing effects of cytokines such as VEGF and TNFα160,161. Excessive ROS can also alter and degrade extracellular matrix proteins and impair the function of keratinocytes and fibroblasts162.

Diabetic wounds, another category of hard-to-heal wounds, are complex and multifactorial. Their aetiology consists classically of a triad of neuropathy, impaired vascularisation and higher susceptibility to infection. These wounds are also notoriously affected by tissue injury after prolonged hypoxia and excessive oxidative stress93. It is thus not surprising that targeting ROS has emerged as a potential therapy for hard-to-heal wounds, similar to other diseases, such as cancer163,164, neurodegenerative diseases165, T cell-mediated autoimmune diseases166, inflammatory skin diseases167, and others. Specifically regarding cancer, ROS play similar pleiotropic roles as they do in wound healing and chronic wound pathogenesis. Depending on the type of cancer and stage, this can include hypoxia-related ROS functions and signalling pathways such as PI3K/AKT or MAPK/ERK pathways, among others, to promote proliferation, migration, or angiogenesis. Similarly, tight regulation of ROS levels is required for cancer progression and can thus also be potentially targeted therapeutically164.

Another factor to take into account is that of senescence, which is the phenomenon of cell cycle arrest and the inhibition of cell proliferation, and is a hallmark of several age-related pathologies, including in the pathogenesis of some chronic wounds168. ROS accumulation and oxidative stress can accelerate senescence in both fibroblasts169 and endothelial cells170, whilst UV-induced ROS upregulation additionally increases senescence and photoageing in skin171.

Diverse strategies have emerged to modulate ROS in wound healing, namely the use of antioxidant materials such as N-acetyl-l-cysteine (NAC)172 or enzymes which either increase local perfusion such as glucose oxidase, or clear free radicals through SODs173,174. Biocompounds that target ROS have also been implicated in improved wound healing, mediated by their effects on perfusion, cell migration, and ROS suppression. Examples of these molecules are Resolvin E1, PDGF, Galectin-1, Alpha-arbutin and Nicotinamide175–179. Nanoparticles have also been developed to improve wound healing, mainly via ROS scavenging, anti-inflammatory and antibacterial effects, and applied to several in vitro and in vivo models180–184, as well as other molecules185–188.

On the other hand, increased angiogenesis has been demonstrated when wounds were treated topically with H2O2189 and both hyperbaric and topical oxygen led to accelerated wound healing190–192. The array of both pro- and anti-ROS treatment stratagies that have been applied to the study of wound healing are described in detail in Table 1.

Table 1.

Molecules targeting ROS in wound healing

| Category | Material | Effect | Model | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antioxidants | NAC | Reduces ROS levels and improves cell migration and proliferation | Cultured human gingival fibroblasts in a high-glucose environment | 172 |

| Enzymes | Glucose oxidase | Increases perfusion (via NO); collagen formation | Diabetic mice with full-thickness wounds, applied in wound dressings | 173 |

| Superoxide dismutase | Clearance of free radicals | Hydrogels used in diabetic rat models with full-thickness wounds | 174 | |

| Bio compounds | Resolvin E1 | Promotes intestinal wound repair (via CREB, mTOR, Src-FAK) | Murine biopsy-induced colonic mucosal wounds | 179 |

| PDGF | Increases NO (higher perfusion); increased angiogenesis and cell migration | Rat model with excisional wounds, mice lacking PDGF receptors/ligands | 175,176 | |

| Galectin-1 | Effect on myofibroblast function and signalling with the release of ROS (via NOX) | Mice injected with recombinant Galectin-1 protein | 177 | |

| Alpha-arbutin | Promotes healing via upregulation of IFG1R | Cultured human dermal fibroblast | 178 | |

| Nicotinamide | Suppresses ROS; increases cell motility | Cultured human HaCaT keratinocytes | 198 | |

| ROS intermediates | Topical H2O2 | Converts into available O2, increase angiogenesis | Guinea pigs with ischemic wounds | 189 |

| Oxygen | Hyperbaric O2 | Reduces wound hypoxia; increases fibroblast proliferation, angiogenesis and accelerated wound healing | Diabetic mouse model, in vitro model, patients (with diabetic and miscellaneous wounds) | 190–192 |

| Topical O2 | Reduces wound hypoxia; accelerates wound healing | Patients, meta-analyses | 199 | |

| Nanomaterials | Copper-based nanoenzymes | ROS scavenging at low concentrations; promotes re-epithelialization and granulation | Murine diabetic model with full-thickness wounds | 183 |

| Cerium oxide nanoparticles | ROS scavenging; stimulation of proliferation and migration of endothelial cells, keratinocytes, and fibroblasts | Human keratinocytes and microvascular endothelial cells. Mouse fibroblasts. Full-thickness wounds in mouse model | 181 | |

| PDA | Capacity of scavenging free radicals; energy transfer | PDA hydrogels in dental pulp stem cells, rat model | 182 | |

| Gold nanoparticles | Anti-inflammatory; antioxidation; enhanced wound healing | In combination with antioxidative small molecules, diabetic mouse model | 180 | |

| Selenium nanoparticles | Antibacterial; anti-inflammatory; antioxidation | In combination with hydrogels, mouse model with full-thickness wounds | 184 | |

| Others | Carbon quantum dots | Eliminates ROS; reduces oxidative stress | Carbon dot hydrogel applied in infected wound from a mouse model | 188 |

| Galvanic particles | Enhance production of ROS by keratinocytes; reduced inflammation; increased fibroblast migration | Human keratinocytes, dermal fibroblasts | 185,186 | |

| Prussian blue | Reduces ROS; increased collagen deposition; induces keratinocyte differentiation, neovascularization, and wound closure | Topically applied, mouse model | 187 |

Summary of ROS modulating materials, their effect or known mechanism of action, and the models where they were tested.

NAC N-acetyl-l-cysteine, PDGF platelet-derived growth factor, IFG1R insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor, PDA polydopamine.

There is, however, a lack of understanding of the exact underlying mechanisms behind the effect of these molecules in many studies and a lack of validation in human samples, which may explain the scarcity of clinical translation. It is also not always evident in the course of a chronic wound history when there is a need to reduce or stimulate ROS production, hence the importance of allying possible treatment strategies that target ROS with the use of sensors that could translate the actual needs of the wound at that given moment193. The utilisation of omics approaches such as scRNAseq to delineate the specific effects of ROS modulation in individual cell types during different stages of wound healing and chronic wound pathogenesis would additionally be of benefit for this purpose.

Conclusions and perspective

ROS and their essential roles in cellular signalling regulation is one of the most important components of the complex pathophysiology of the wound healing cascade. However, owing to the multifaceted nature of wound healing and chronic wound formation, improper regulation of either ROS production or removal can lead to oxidative stress and impairment of wound healing, contributing to the formation and propagation of chronic wounds. In light of this, there has been a greater emphasis in recent years towards investigating whether ROS can be targeted to either accelerate wound healing, or conversely, be used as a treatment for chronic wounds – with no concrete advancements with regards to clinically approved therapies as of yet.

This discrepancy can partially be explained by gaps in knowledge surrounding the cellular and molecular landscape of ROS in wound healing, including for example, the role of ROS and metabolism76,127, as well as that of redox signalling and stem cell homeostasis. In addition, future work is required in order to elucidate the specific dynamics of ROS and in particular H2O2, including the movement of H2O2 and its interplay with specific AQPs and gap junctions, or the role of ROS and other ROS-producing organelles such as the ER, which play important roles in wound healing and may potentially be targeted through pre-clinical agents194.

Finally, it is important to note that whilst most of the investigations into the role of ROS in wound healing have been performed in animal models such as zebrafish or Drosophila, these studies have predominantly investigated the similar but pathophysiologically different process of regeneration, as opposed to wound healing itself195. However, the fact that various studies have shown that many of these pathways are activated in separate animal models140,196,197 – such as ERK signalling – suggests that the effects of ROS are phylogenetically conserved. However, advances in methods which allow for more targeted analyses of specific cell types and their roles in different stage of wound healing pathophysiology, such as scRNAseq, are an important step in advancing knowledge in the field of ROS and wound healing.

Supplementary information

Author contributions

M.H., M.T., E.B.W. and J.W. wrote the manuscript. M.H., E.B.W., J.W. planned the manuscript. M.T. and M.H. prepared the figures.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Biology thanks Nik Georgopoulos and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: Manuel Breuer. A peer review file is available.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Karolinska Institute.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s42003-024-07219-w.

References

- 1.Peña, O. & Martin, P. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of skin wound healing. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 25, 599–616 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Torres, M. et al. The temporal dynamics of proteins in aged skin wound healing and comparison to gene expression. J. Invest. Dermatol. (2024).

- 3.Schultz, G. et al. In Principles of Wound Healing. (University of Adelaide Press, 2011). [PubMed]

- 4.Eming, S., Krieg, T. & Davidson, J. Inflammation in wound repair: molecular and cellular mechanisms. J. Invest. Dermatol.127, 514–525 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nirenjen, S. et al. Exploring the contribution of pro-inflammatory cytokines to impaired wound healing in diabetes. Front. Immunol.14, 1216321 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Evans, J., Kaitu’u-Lino, T. & Salamonsen, L. Extracellular matrix dynamics in scar-free endometrial repair: perspectives from mouse in vivo and human in vitro studies. Biol. Reprod.85, 511–523 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dunnill, C. et al. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) and wound healing: The functional role of ROS and emerging ROS-modulating technologies for augmentation of the healing process. Int. Wound J.14, 89–96 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sies, H. & Jones, D. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) as pleiotropic physiological signalling agents. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol.21, 363–383 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Polaka, S., Katare, P. & Pawar, B. & et, a. Emerging ROS-modulating technologies for augmentation of the wound healing process. ACS Omega7, 30657–30672 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schieber, M. & Chandel, N. ROS function in redox signaling and oxidative stress. Curr. Biol.24, R453–R462 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Klyubin, I. et al. Hydrogen peroxide-induced chemotaxis of mouse peritoneal neutrophils. Eur. J. Cell Biol.70, 347–351 (1996). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li, X. et al. Exosomes from adipose-derived stem cells overexpressing Nrf2 accelerate cutaneous wound healing by promoting vascularization in a diabetic foot ulcer rat model. Exp. Mol. Med.50, 1–14 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vara, D. et al. Direct Activation of NADPH Oxidase 2 by 2-Deoxyribose-1-Phosphate Triggers Nuclear Factor Kappa B-Dependent Angiogenesis. Antioxid. Redox Signal28, 110–130 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang, G. et al. The initiation of oxidative stress and therapeutic strategies in wound healing. Biomed. Pharmacother.157, 114004 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Cano Sanchez, M., Lancel, S., Boulanger, E. & Neviere, R. Targeting Oxidative Stress and Mitochondrial Dysfunction in the Treatment of Impaired Wound Healing: A Systematic Review. Antioxidants7, 98 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Yoo, S., Starnes, T., Deng, Q. & Huttenlocher, A. Lyn is a redox sensor that mediates leukocyte wound attraction in vivo. Nature480, 109–112 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Niethammer, P., Grabher, C., Look, A. & Mitchison, T. A tissue-scale gradient of hydrogen peroxide mediates rapid wound detection in zebrafish. Nature459, 996–999 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Love, N. et al. Amputation-induced reactive oxygen species are required for successful Xenopus tadpole tail regeneration. Nat. Cell Biol.15, 222–228 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Gauron, C. et al. Sustained production of ROS triggers compensatory proliferation and is required for regeneration to proceed. Sci. Rep.3, 2084 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Al Haj Baddar, N., Chithrala, A. & Voss, S. Amputation-induced reactive oxygen species signaling is required for axolotl tail regeneration. Dev. Dyn.248, 189–196 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Labit, E. et al. Opioids prevent regeneration in adult mammals through inhibition of ROS production. Sci. Rep.8, 12170 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Santabárbara-Ruiz, P. et al. Ask1 and Akt act synergistically to promote ROS-dependent regeneration in Drosophila. PLoS Genet15, e1007926 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gouzos, M. et al. Antibiotics Affect ROS Production and Fibroblast Migration in an In-vitro Model of Sinonasal Wound Healing. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol10, 110 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xu, Z., Han, S., Gu, Z. & Wu, J. Advances and Impact of Antioxidant Hydrogel in Chronic Wound Healing. Adv. Healthc. Mater.9, e1901502 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Dong, Y. & Wang, Z. ROS-scavenging materials for skin wound healing: advancements and applications. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 11, 1304835 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Checa, J. & Aran, J. Reactive Oxygen Species: Drivers of Physiological and Pathological Processes. J. Inflamm. Res.13, 1057–1073 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Di Marzo, N., Chisci, E. & Giovannoni, R. The Role of Hydrogen Peroxide in Redox-Dependent Signaling: Homeostatic and Pathological Responses in Mammalian Cells. Cells7, 156 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Santos, C., Hafstad, A. & Beretta, M. & al., e. Targeted redox inhibition of protein phosphatase 1 by Nox4 regulates eIF2α-mediated stress signaling. EMBO J.35, 319–334 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bienert, G., Schjoerring, J. & Jahn, T. Membrane transport of hydrogen peroxide. Biochim. Biophys. Acta1758, 994–1003 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Henzler, T. & Steudle, E. Transport and metabolic degradation of hydrogen peroxide in Chara corallina: model calculations and measurements with the pressure probe suggest transport of H(2)O(2) across water channels. J. Exp. Bot.51, 2053–2066 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.García-Dorado, D., Rodríguez-Sinovas, A. & Ruiz-Meana, M. Gap junction-mediated spread of cell injury and death during myocardial ischemia-reperfusion. Cardiovasc Res.61, 386–401 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kaya, A., Lee, B. & Gladyshev, V. Regulation of protein function by reversible methionine oxidation and the role of selenoprotein MsrB1. Antioxid. Redox Signal23, 814–822 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sun, X. et al. The Natural Diterpenoid Isoforretin A Inhibits Thioredoxin-1 and Triggers Potent ROS-Mediated Antitumor Effects. Cancer Res.77, 926–936 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Holmström, K. & Finkel, T. Cellular mechanisms and physiological consequences of redox-dependent signalling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol.15, 411–421 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dickinson, B. & Chang, C. Chemistry and biology of reactive oxygen species in signaling or stress responses. Nat. Chem. Biol.7, 504–511 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bedard, K. & Krause, K. The NOX family of ROS-generating NADPH oxidases: physiology and pathophysiology. Physiol. Rev.87, 245–313 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Parascandolo, A. & Laukkanen, M. Carcinogenesis and Reactive Oxygen Species Signaling: Interaction of the NADPH Oxidase NOX1-5 and Superoxide Dismutase 1-3 Signal Transduction Pathways. Antioxid. Redox Signal30, 443–486 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yoshihara, A. et al. Regulation of dual oxidase expression and H2O2 production by thyroglobulin. Thyroid22, 1054–1062 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Murphy, M. How mitochondria produce reactive oxygen species. Biochem. J.417, 1–13 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Boveris, A., Oshino, N. & Chance, B. The cellular production of hydrogen peroxide. Biochem. J.128, 617–630 (1972). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hunt, M., Torres, M., Bachar-Wikström, E. & Wikström, J. Multifaceted roles of mitochondria in wound healing and chronic wound pathogenesis. Front. Cell Dev. Biol.11, 1252318 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.Wong, H., Benoit, B. & Brand, M. Mitochondrial and cytosolic sources of hydrogen peroxide in resting C2C12 myoblasts. Free Radic. Biol. Med130, 140–150 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Niedzwiecki, M. et al. The Exposome: Molecules to Populations. Annu Rev. Pharm. Toxicol.59, 107–127 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rada, B. & Leto, T. Oxidative innate immune defenses by Nox/Duox Family NADPH oxidases. Contrib. Microbiol15, 164–187 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Martínez-Revelles, S. et al. Reciprocal relationship between reactive oxygen species and cyclooxygenase-2 and vascular dysfunction in hypertension. Antioxid. Redox Signal18, 51–65 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ding, L. et al. Peroxisomal β-oxidation acts as a sensor for intracellular fatty acids and regulates lipolysis. Nat. Metab.3, 1648–1661 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rhee, S. & Kil, I. Multiple Functions and Regulation of Mammalian Peroxiredoxins. Annu. Rev. Biochem.86, 749–775 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chance, B., Sies, H. & Boveris, A. Hydroperoxide metabolism in mammalian organs. Physiol. Rev.59, 527–605 (1979). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Brigelius-Flohé, R. & Flohé, L. Regulatory Phenomena in the Glutathione Peroxidase Superfamily. Antioxid. Redox Signal33, 498–516 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rampon, C., Volovitch, M., Joliot, A. & Vriz, S. Hydrogen Peroxide and Redox Regulation of Developments. Antioxidants7, 159 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 51.Ronchi, J., Francisco, A., Passos, L., Figueira, T. & Castilho, R. The Contribution of Nicotinamide Nucleotide Transhydrogenase to Peroxide Detoxification Is Dependent on the Respiratory State and Counterbalanced by Other Sources of NADPH in Liver Mitochondria. J. Biol. Chem.291, 20173–20187 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hong, W. et al. The Role of Hypoxia-Inducible Factor in Wound Healing. Adv. Wound Care3, 390–399 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fujiwara, T. et al. Extracellular superoxide dismutase deficiency impairs wound healing in advanced age by reducing neovascularization and fibroblast function. Exp. Dermatol.25, 206–211 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Akhigbe, R. & Ajayi, A. The impact of reactive oxygen species in the development of cardiometabolic disorders: a review. Lipids Health Dis.20, 23 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 55.Madreiter-Sokolowski, C., Thomas, C. & Ristow, M. Interrelation between ROS and Ca 2+ in aging and age-related diseases. Redox Biol. 36, 101678 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 56.Schapira, A. et al. Mitochondrial complex I deficiency in Parkinson’s disease. J. Neurochem54, 823–827 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hasani, M. et al. Oxidative balance score and risk of cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. BMC Cancer23, 1143 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 58.Wlaschek, M., Singh, K., Sindrilaru, A., Crisan, D. & Scharffetter-Kochanek, K. Iron and iron-dependent reactive oxygen species in the regulation of macrophages and fibroblasts in non-healing chronic wounds. Free Radic. Biol. Med.133, 262–275 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sivaraj, D. et al. Nitric oxide-releasing gel accelerates healing in a diabetic murine splinted excisional wound model. Front. Med.10, 1060758 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 60.Papapetropoulos, A., García-Cardeña, G., Madri, J. & Sessa, W. Nitric oxide production contributes to the angiogenic properties of vascular endothelial growth factor in human endothelial cells. J. Clin. Invest.100, 3131–3139 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Paul-Clark, M., Gilroy, D., Willis, D., Willoughby, D. & Tomlinson, A. Nitric oxide synthase inhibitors have opposite effects on acute inflammation depending on their route of administration. J. Immunol.166, 1169–1177 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Donnini, S. & Ziche, M. Constitutive and inducible nitric oxide synthase: role in angiogenesis. Antioxid. Redox Signal4, 817–823 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kitano, T. et al. Impaired Healing of a Cutaneous Wound in an Inducible Nitric Oxide Synthase-Knockout Mouse. Dermatol. Res. Pr.2017, 2184040 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yang, Y. et al. Ubiquitination Flow Repressors: Enhancing Wound Healing of Infectious Diabetic Ulcers through Stabilization of Polyubiquitinated Hypoxia-Inducible Factor-1α by Theranostic Nitric Oxide Nanogenerators. Adv. Mater.33, 2103593 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 65.Lin, Y. et al. In Situ Self-Assembling Micellar Depots that Can Actively Trap and Passively Release NO with Long-Lasting Activity to Reverse Osteoporosis. Adv. Mater. 30, e1705605 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 66.Radziwon-Balicka, A. et al. Differential eNOS-signalling by platelet subpopulations regulates adhesion and aggregation. Cardiovasc Res.113, 1719–1731 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Arany, I., Brysk, M., Brysk, H. & Tyring, S. Regulation of inducible nitric oxide synthase mRNA levels by differentiation and cytokines in human keratinocytes. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun.220, 618–622 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Krischel, V. et al. Biphasic effect of exogenous nitric oxide on proliferation and differentiation in skin derived keratinocytes but not fibroblasts. J. Invest. Dermatol.111, 286–291 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Stallmeyer, B., Kämpfer, H., Kolb, N., Pfeilschifter, J. & Frank, S. The function of nitric oxide in wound repair: inhibition of inducible nitric oxide-synthase severely impairs wound reepithelialization. J. Invest. Dermatol.113, 1090–1098 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Malone-Povolny, M., Maloney, S. & Schoenfisch, M. Nitric Oxide Therapy for Diabetic Wound Healing. Adv. Health. Mater.8, e1801210 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Peters, S., Mathy, M., Pfaffendorf, M. & van Zwieten, P. Reactive oxygen species-induced aortic vasoconstriction and deterioration of functional integrity. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharm.361, 127–133 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Razzell, W., Evans, I., Martin, P. & Wood, W. Calcium flashes orchestrate the wound inflammatory response through DUOX activation and hydrogen peroxide release. Curr. Biol.23, 424–429 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.de Oliveira, S. et al. ATP modulates acute inflammation in vivo through dual oxidase 1-derived H2O2 production and NF-κB activation. J. Immunol.192, 5710–5719 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Eming, S., Wynn, T. & Martin, P. Inflammation and metabolism in tissue repair and regeneration. Science56, 1026–1030 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Weinberg, S., Sena, L. & Chandel, N. Mitochondria in the regulation of innate and adaptive immunity. Immunity42, 406–417 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Willenborg, S. et al. Mitochondrial metabolism coordinates stage-specific repair processes in macrophages during wound healing. Cell Metab.33, 2398–2414.e9 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 77.Lee, C., Qiao, M., Schröder, K., Zhao, Q. & Asmis, R. Nox4 is a novel inducible source of reactive oxygen species in monocytes and macrophages and mediates oxidized low density lipoprotein-induced macrophage death. Circ. Res.106, 1489–1497 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kim, S. & Nair, M. Macrophages in wound healing: activation and plasticity. Immunol. Cell Biol.97, 258–267 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Bulua, A. et al. Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species promote production of proinflammatory cytokines and are elevated in TNFR1-associated periodic syndrome (TRAPS). J. Exp. Med.208, 519–533 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Zhao, C., Gillette, D., Li, X., Zhang, Z. & Wen, H. Nuclear factor E2-related factor-2 (Nrf2) is required for NLRP3 and AIM2 inflammasome activation. J. Biol. Chem.289, 17020–17029 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Cuadrado, A. et al. Transcription Factor NRF2 as a Therapeutic Target for Chronic Diseases: A Systems Medicine Approach. Pharm. Rev.70, 348–383 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Bonello, S. et al. Reactive oxygen species activate the HIF-1alpha promoter via a functional NFkappaB site. Arterioscler Thromb. Vasc. Biol.27, 755–761 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ranneh, Y. et al. Crosstalk between reactive oxygen species and pro-inflammatory markers in developing various chronic diseases: a review. Appl Biol. Chem.60, 327–338 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 84.Villarino, A., Kanno, Y. & O’Shea, J. Mechanisms and consequences of Jak-STAT signaling in the immune system. Nat. Immunol., 18, 374-384 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 85.Ostadkarampour, M. & Putnins, E. Monoamine Oxidase Inhibitors: A Review of Their Anti-Inflammatory Therapeutic Potential and Mechanisms of Action. Front. Pharm.12, 676239 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Bhattacharjee, A. et al. IL-4 and IL-13 employ discrete signaling pathways for target gene expression in alternatively activated monocytes/macrophages. Free Radic. Biol. Med.54, 1–16 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Ekuni, D. et al. Lipopolysaccharide-induced epithelial monoamine oxidase mediates alveolar bone loss in a rat chronic wound model. Am. J. Pathol.175, 1398–1409 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Fogarty, C. et al. Extracellular Reactive Oxygen Species Drive Apoptosis-Induced Proliferation via Drosophila Macrophages. Curr. Biol.26, 575–584 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Canton, M. et al. Reactive Oxygen Species in Macrophages: Sources and Targets. Front. Immunol.12, 734229 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Bian, Z. et al. Deciphering human macrophage development at single-cell resolution. Nature582, 571–576 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Zheng, H. et al. Recent advances in strategies to target the behavior of macrophages in wound healing. Biomed. Pharmacother.165, 115199 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Xiao, Y. et al. Single-cell profiling and functional screening reveal crucial roles for lncRNAs in the epidermal re-epithelialization of human acute wounds. Front. Surg.11, 1349135 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Falanga, V. et al. Chronic wounds. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim.8, 50 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Clark, R. Basics of cutaneous wound repair. J. Dermatol Surg. Oncol.19, 693–706 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Geiszt, M., Witta, J., Baffi, J., Lekstrom, K. & Leto, T. Dual oxidases represent novel hydrogen peroxide sources supporting mucosal surface host defense. FASEB J.17, 1502–1504 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Ha, E., Oh, C., Bae, Y. & Lee, W. A direct role for dual oxidase in Drosophila gut immunity. Science310, 847–850 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Cavallo, I. et al. Homocysteine and Inflammatory Cytokines in the Clinical Assessment of Infection in Venous Leg Ulcers. Antibiotics11, 1268 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 98.Winterbourn, C., Kettle, A. & Hampton, M. Reactive Oxygen Species and Neutrophil Function. Annu. Rev. Biochem.85, 765–792 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Kenny, E. et al. Diverse stimuli engage different neutrophil extracellular trap pathways. Elife6, e24437 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Pase, L., Nowell, C. & Lieschke, G. In vivo real-time visualization of leukocytes and intracellular hydrogen peroxide levels during a zebrafish acute inflammation assay. Methods Enzymol.506, 135–156 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Ojha, N. et al. Assessment of wound-site redox environment and the significance of Rac2 in cutaneous healing. Free Radic. Biol. Med.44, 682–691 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Méndez, D. et al. Mitoquinone (MitoQ) Inhibits Platelet Activation Steps by Reducing ROS Levels. Int. J. Mol. Sci.21, 6192 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Fidler, T. et al. Superoxide Dismutase 2 is dispensable for platelet function. Thromb. Haemost.117, 1859–1867 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Kim, S. et al. Platelet-derived mitochondria transfer facilitates wound-closure by modulating ROS levels in dermal fibroblasts. Platelets34, 2151996 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 105.Li, W., Liu, G., Chou, I. & Kagan, H. Hydrogen peroxide-mediated, lysyl oxidase-dependent chemotaxis of vascular smooth muscle cells. J. Cell Biochem78, 550–557 (2000). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Brüne, B. Nitric oxide: NO apoptosis or turning it ON? Cell Death Differ.10, 864–869 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Cai, Z. et al. Endothelial Nitric Oxide Synthase-Derived Nitric Oxide Prevents Dihydrofolate Reductase Degradation via Promoting S-Nitrosylation. Arterioscler Thromb. Vasc. Biol.35, 2366–2373 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Wang, J., Hong, Z., Zeng, C., Yu, Q. & Wang, H. NADPH oxidase 4 promotes cardiac microvascular angiogenesis after hypoxia/reoxygenation in vitro Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 69, 278–288 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Martinotti, S., Patrone, M., Balbo, V., Mazzucco, L. & Ranzato, E. Endothelial response boosted by platelet lysate: the involvement of calcium toolkit. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21, 808 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 110.Evangelista, A., Thompson, M., Bolotina, V., Tong, X. & Cohen, R. Nox4- and Nox2-dependent oxidant production is required for VEGF-induced SERCA cysteine-674 S-glutathiolation and endothelial cell migration. Free Radic. Biol. Med.53, 2327–2334 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Yang, J. The role of reactive oxygen species in angiogenesis and preventing tissue injury after brain ischemia. Microvasc. Res.123, 62–67 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Menden, H., Welak, S., Cossette, S., Ramchandran, R. & Sampath, V. Lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-mediated angiopoietin-2-dependent autocrine angiogenesis is regulated by NADPH oxidase 2 (Nox2) in human pulmonary microvascular endothelial cells. J. Biol. Chem.290, 5449–5461 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Brown, N. & Bicknell, R. Thymidine phosphorylase, 2-deoxy-D-ribose and angiogenesis. Biochem J.334, 1–8 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Go, Y. & Jones, D. The redox proteome. J. Biol. Chem.288, 26512–26520 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Pak, V. et al. Ultrasensitive Genetically Encoded Indicator for Hydrogen Peroxide Identifies Roles for the Oxidant in Cell Migration and Mitochondrial Function. Cell Metab.31, 642–653.e646 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Balta, E., Kramer, J. & Samstag, Y. Redox Regulation of the Actin Cytoskeleton in Cell Migration and Adhesion: On the Way to a Spatiotemporal View. Front. Cell Dev. Biol.8, 618261 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Hunter, M., Willoughby, P., AEE, B. & Fernandez-Gonzalez, R. Oxidative Stress Orchestrates Cell Polarity to Promote Embryonic Wound Healing. Dev. Cell47, 377–387 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Xu, S. & Chisholm, A. C. elegans epidermal wounding induces a mitochondrial ROS burst that promotes wound repair. Dev. Cell31, 48–60 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Sherwood, C., Lantz, R., Burgess, J. & Boitano, S. Arsenic alters ATP-dependent Ca²+ signaling in human airway epithelial cell wound response. Toxicol. Sci.121, 191–206 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Bucheimer, R. & Linden, J. Purinergic regulation of epithelial transport. J. Physiol.555, 311–321 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Pillai, S. & Bikle, D. Adenosine triphosphate stimulates phosphoinositide metabolism, mobilizes intracellular calcium, and inhibits terminal differentiation of human epidermal keratinocytes. J. Clin. Invest.90, 42–51 (1992). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Van Huizen, A., Hack, S., Greene, J., Kinsey, L. & Beane, W. Reactive Oxygen Species Signaling Differentially Controls Wound Healing and Regeneration. bioRxiv, https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2022.04.05.487111v1.full (2022).

- 123.Yue, C. et al. c-Jun Overexpression Accelerates Wound Healing in Diabetic Rats by Human Umbilical Cord-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Stem Cells Int.2020, 7430968 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 124.Fujino, G. et al. Thioredoxin and TRAF family proteins regulate reactive oxygen species-dependent activation of ASK1 through reciprocal modulation of the N-terminal homophilic interaction of ASK1. Mol. Cell Biol.27, 8152–8163 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Esteban-Collado, J., Corominas, M. & Serras, F. Nutrition and PI3K/Akt signaling are required for p38-dependent regeneration. Development148, dev197087 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 126.Patel, P. et al. Damage sensing by a Nox-Ask1-MKK3-p38 signaling pathway mediates regeneration in the adult Drosophila midgut. Nat. Commun.10, 4365 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Manchanda, M. et al. Metabolic Reprogramming and Reliance in Human Skin Wound Healing. J. Invest Dermatol.S0022-202X, 01975–01979 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Romero, M., McCathie, G., Jankun, P. & Roehl, H. Damage-induced reactive oxygen species enable zebrafish tail regeneration by repositioning of Hedgehog expressing cells. Nat. Commun.9, 4010 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Meda, F. et al. Nerves Control Redox Levels in Mature Tissues Through Schwann Cells and Hedgehog Signaling. Antioxid. Redox Signal24, 299–311 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Thauvin, M. et al. An early Shh-H2O2 reciprocal regulatory interaction controls the regenerative program during zebrafish fin regeneration. J. Cell Sci.135, jcs259664 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Singh, B., Doyle, M., Weaver, C., Koyano-Nakagawa, N. & Garry, D. Hedgehog and Wnt coordinate signaling in myogenic progenitors and regulate limb regeneration. Dev. Biol.371, 23–34 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Hamanaka, R. et al. Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species promote epidermal differentiation and hair follicle development. Sci Signal6, ra8 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 133.LeBert, D. et al. Damage-induced reactive oxygen species regulate vimentin and dynamic collagen-based projections to mediate wound repair. Elife7, e30703 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 134.Morgan, M. & Liu, Z. Crosstalk of reactive oxygen species and NF-kappaB signaling. Cell Res.21, 103–115 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Kamata, H., Manabe, T., Oka, S., Kamata, K. & Hirata, H. Hydrogen peroxide activates IkappaB kinases through phosphorylation of serine residues in the activation loops. FEBS Lett.519, 231–237 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Halvey, P. et al. Selective oxidative stress in cell nuclei by nuclear-targeted D-amino acid oxidase. Antioxid. Redox Signal9, 807–816 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Schwörer, S. et al. Proline biosynthesis is a vent for TGFβ-induced mitochondrial redox stress. EMBO J.39, e103334 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Bansal, R. et al. Role of the mitochondrial protein cyclophilin D in skin wound healing and collagen secretion. JCI Insight9, e169213 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Zhao, F., Wei, W., Huang, D. & Guo, Y. Knockdown of miR-27a reduces TGFβ-induced EMT and H 2 O 2 -induced oxidative stress through regulating mitochondrial autophagy. Am. J. Transl. Res.15, 6071–6082 (2023). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Yoo, S., Freisinger, C., LeBert, D. & Huttenlocher, A. Early redox, Src family kinase, and calcium signaling integrate wound responses and tissue regeneration in zebrafish. J. Cell Biol.199, 225–234 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Cabodi, S. et al. A PKC-eta/Fyn-dependent pathway leading to keratinocyte growth arrest and differentiation. Mol. Cell6, 1121–1129 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Saito, Y., Jensen, A., Salgia, R. & Posadas, E. Fyn: a novel molecular target in cancer. Cancer116, 1629–1637 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Klotz, L. & Steinbrenner, H. Cellular adaptation to xenobiotics: Interplay between xenosensors, reactive oxygen species and FOXO transcription factors. Redox Biol.13, 646–654 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Miao, C., Li, Y. & Zhang, X. The functions of FoxO transcription factors in epithelial wound healing. Australas. J. Dermatol60, 105–109 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Jeon, H. et al. FOXO1 regulates VEGFA expression and promotes angiogenesis in healing wounds. J. Pathol.245, 258–264 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Ponugoti, B. et al. FOXO1 promotes wound healing through the up-regulation of TGF-β1 and prevention of oxidative stress. J. Cell Biol.203, 327–343 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Dhoke, N., Geesala, R. & Das, A. Low Oxidative Stress-Mediated Proliferation Via JNK-FOXO3a-Catalase Signaling in Transplanted Adult Stem Cells Promotes Wound Tissue Regeneration. Antioxid. Redox Signal28, 1047–1065 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Tonelli, C., Chio, I. & Tuveson, D. Transcriptional Regulation by Nrf2. Antioxid. Redox Signal29, 1727–1745 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Schmidt, A. & Bekeschus, S. Redox for Repair: Cold Physical Plasmas and Nrf2 Signaling Promoting Wound Healing. Antioxidants7, 146 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 150.Fourquet, S., Guerois, R., Biard, D. & Toledano, M. Activation of NRF2 by nitrosative agents and H2O2 involves KEAP1 disulfide formation. J. Biol. Chem.285, 8463–8471 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Süntar, I. et al. Regulatory Role of Nrf2 Signaling Pathway in Wound Healing Process. Molecules26, 2424 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Long, M. et al. An Essential Role of NRF2 in Diabetic Wound Healing. Diabetes65, 780–793 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Kuhn, J. et al. Nrf2-activating Therapy Accelerates Wound Healing in a Model of Cutaneous Chronic Venous Insufficiency. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. Glob. Open8, e3006 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Li, D. et al. LPS-stimulated Macrophage Exosomes Inhibit Inflammation by Activating the Nrf2 / HO-1 Defense Pathway and Promote Wound Healing in Diabetic Rats, 2020, PREPRINT. Res. Sq. Preprint at: 10.21203/rs.3.rs-78864/v1 (2020).

- 155.Fan, J. et al. Procyanidin B2 improves endothelial progenitor cell function and promotes wound healing in diabetic mice via activating Nrf2. J. Cell Mol. Med. 25, 652–665 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Li, M. et al. Nrf2 Suppression Delays Diabetic Wound Healing Through Sustained Oxidative Stress and Inflammation. Front Pharm.10, 1099 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Hozzein, W. et al. Bee venom improves diabetic wound healing by protecting functional macrophages from apoptosis and enhancing Nrf2, Ang-1 and Tie-2 signaling. Mol. Immunol.103, 322–335 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Rieger, S. & Sagasti, A. Hydrogen peroxide promotes injury-induced peripheral sensory axon regeneration in the zebrafish skin. PLoS Biol.9 e1000621 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 159.Schäfer, M. & Werner, S. Oxidative stress in normal and impaired wound repair. Pharm. Res.58, 165–171 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160.Lord, M. et al. Perlecan and vascular endothelial growth factor-encoding DNA-loaded chitosan scaffolds promote angiogenesis and wound healing. J. Control Rel.250, 48–61 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161.Seiwerth, S. et al. BPC 157 and Standard Angiogenic Growth Factors. Gastrointestinal Tract Healing, Lessons from Tendon, Ligament, Muscle and Bone Healing. Curr. Pharm. Des.24, 1972–1989 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 162.Moseley, R., Stewart, J., Stephens, P., Waddington, R. & Thomas, D. Extracellular matrix metabolites as potential biomarkers of disease activity in wound fluid: lessons learned from other inflammatory diseases? Br. J. Dermatol.150, 401–413 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 163.Perillo, B. et al. ROS in cancer therapy: the bright side of the moon. Exp. Mol. Med.52, 192–203 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 164.Chasara, R., Ajayi, T., Leshilo, D., Poka, M. & Witika, B. Exploring novel strategies to improve anti-tumour efficiency: The potential for targeting reactive oxygen species. Heliyon9, e19896 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 165.Aborode, A. et al. Targeting Oxidative Stress Mechanisms to Treat Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s Disease: A Critical Review. Oxidative Med. Cell Longev.2022, 7934442 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 166.Chávez, M. & Tse, H. Targeting Mitochondrial-Derived Reactive Oxygen Species in T Cell-Mediated Autoimmune Diseases. Front. Immunol.12, 703972 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 167.Khan, A. et al. Targeting deregulated oxidative stress in skin inflammatory diseases: An update on clinical importance. Biomed. Pharmacother.154, 113601 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 168.Wilkinson, H. & Hardman, M. Senescence in Wound Repair: Emerging Strategies to Target Chronic Healing Wounds. Front. Cell Dev. Biol.11, 773 (2020). 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 169.Duan, J., Duan, J., Zhang, Z. & Tong, T. Irreversible cellular senescence induced by prolonged exposure to H2O2 involves DNA-damage-and-repair genes and telomere shortening. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol.37, 1407–1420 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 170.Ruan, Y., Wu, S., Zhang, L., Chen, G. & Lai, W. Retarding the senescence of human vascular endothelial cells induced by hydrogen peroxide: effects of 17beta-estradiol (E2) mediated mitochondria protection. Biogerontology15, 367–375 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 171.Herrling, T., Jung, K. & Fuchs, J. Measurements of UV-generated free radicals/reactive oxygen species (ROS) in skin. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc.63, 840–845 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 172.Buranasin, P. et al. High glucose-induced oxidative stress impairs proliferation and migration of human gingival fibroblasts. PLoS ONE13, e0201855 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 173.Arul, V. et al. Glucose Oxidase Incorporated Collagen Matrices for Dermal Wound Repair in Diabetic Rat Models: A Biochemical Study. J. Biomater. Appl26, 917–938 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 174.Zhang, L. et al. A composite hydrogel of chitosan/heparin/poly (γ-glutamic acid) loaded with superoxide dismutase for wound healing. Carbohydr. Polym.180, 168–174 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 175.Beer, H., Longaker, M. & Werner, S. Reduced Expression of PDGF and PDGF Receptors During Impaired Wound Healing. J. Investig. Dermatol109, 132–138 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 176.Kaltalioglu, K., Coskun-Cevher, S., Tugcu-Demiroz, F. & Celebi, N. PDGF supplementation alters oxidative events in wound healing process: a time course study. Arch. Dermatol Res.305, 415–422 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 177.Lin, Y. et al. Galectin-1 Accelerates Wound Healing by Regulating the Neuropilin-1/Smad3/NOX4 Pathway and ROS Production in Myofibroblasts. J. Investig. Dermatol.135, 258–268 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 178.Polouliakh, N. et al. Alpha-Arbutin Promotes Wound Healing by Lowering ROS and Upregulating Insulin/IGF-1 Pathway in Human Dermal Fibroblast. Front. Physiol.11, 586843 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 179.Quiros, M. et al. Resolvin E1 is a pro-repair molecule that promotes intestinal epithelial wound healing. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci.117, 9477–9482 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 180.Chen, S. et al. Topical treatment with anti-oxidants and Au nanoparticles promote healing of diabetic wound through receptor for advance glycation end-products. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci.47, 875–883 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 181.Chigurupati, S. et al. Effects of cerium oxide nanoparticles on the growth of keratinocytes, fibroblasts and vascular endothelial cells in cutaneous wound healing. Biomaterials34, 2194–2201 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 182.Zhang, S. et al. Polydopamine/puerarin nanoparticle-incorporated hybrid hydrogels for enhanced wound healing. Biomater. Sci.7, 4230–4236 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 183.Liu, T. et al. Ultrasmall copper-based nanoparticles for reactive oxygen species scavenging and alleviation of inflammation related diseases. Nat. Commun.11, 2788 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]