Abstract

Electrical impedance tomography (EIT) is an emerging technology for the non-invasive monitoring of regional distribution of ventilation and perfusion, offering real-time and continuous data that can greatly enhance our understanding and management of various respiratory conditions and lung perfusion. Its application may be especially beneficial for critically ill mechanically ventilated patients. Despite its potential, clear evidence of clinical benefits is still lacking, in part due to a lack of standardization and transparent reporting, which is essential for ensuring reproducible research and enhancing the use of EIT for personalized mechanical ventilation. This report is the result of a four-day expert meeting where we aimed to promote the consistent and reliable use of EIT, facilitating its integration into both clinical practice and research, focusing on the adult intensive care patient. We discuss the state-of-the-art regarding EIT acquisition and processing, applications during controlled ventilation and spontaneous breathing, ventilation-perfusion assessment, and novel future directions.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13054-024-05173-x.

Keywords: Electrical impedance tomography, Mechanical ventilation, Respiratory monitoring, Signal processing, Ventilation distribution, Lung perfusion

Introduction

Imaging plays a crucial role in the diagnosis and monitoring of critically ill patients. Among others, electrical impedance tomography (EIT) has gained popularity as a safe, non-invasive and validated bedside technique for real-time continuous evaluation of the ventilation and perfusion distribution [1, 2]. Given its high temporal resolution, ability to show regional ventilation/perfusion and track changes over time, EIT may be particularly valuable in mechanically ventilated patients [1–5]. EIT improves our physiological understanding of respiratory failure at bedside (e.g., with hypoxemia, pulmonary derecruitment, or potentially patient self-inflicted lung injury—P-SILI). It can also monitor and assess the dynamic response to maneuvers (e.g. titration of positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) [3], prone positioning [4]) and enables investigating specific pulmonary conditions over time.

Hence, EIT application may be crucial in point-of-care evaluation of lung physiology and delivering of individualized mechanical ventilation. Despite its potential, clear evidence of clinical benefits is still lacking [1, 5]. This may be related to technical barriers and a lack of standardization in data processing and in the interpretation of analyses, which is key to allow successful clinical integration [6].

To evaluate the state-of-the-art of EIT monitoring and to stimulate standardized experimental use and thereby to promote a successful implementation of EIT in clinical practice, a four-day expert meeting was held in the spring of 2024 in Leiden (The Netherlands) to discuss how to best acquire, process, analyze and interpret EIT data, both in a clinical and scientific context. The expert group comprised professionals with different clinical and/or scientific expertise in EIT, including medical doctors, technical physicians, respiratory therapists and biomedical engineers. This paper summarizes the insights gained from this meeting and provides recommendations on five areas of interest: (1) EIT acquisition, (2) EIT signal and image processing, (3) applications during controlled ventilation, (4) applications during spontaneous breathing, and (5) ventilation-perfusion assessment, focusing on adult patients in the intensive care unit (ICU). Novel future directions of EIT are also discussed.

EIT acquisition

Best practices are summarized in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

EIT acquisition and best practices. Abbreviations: A.U., arbitrary units; EELI, end-expiratory lung impedance; EIT, electrical impedance tomography; US, ultrasound

Electrode belt placement and EIT initiation

For in-depth technical principles of EIT, we refer to Frerichs et al. [2]. To date, indications and contraindications for EIT use are not necessarily evidence-based, but rather resulting from expert consensus. The first step to obtain a reliable measurement is the correct positioning of the electrode belt. The belt is typically positioned transversely between the 4th and 5th intercostal space [2], measured in the parasternal line. Positioning of the belt too low could result in artifacts from diaphragm movement and inaccurate values of tidal impedance variation (TIV) [7]. Conversely, placement of the belt too high may induce an erroneous estimation of ventilated areas, especially regarding dorsal regions [8–10]. Belt rotation should also be avoided, as it will affect the reconstructed image [11]. Belt plane orientation is also important: an obliquely placed belt (i.e., dorsal part of the belt placed more cranially than its ventral part), will result in an underrepresentation of the dorsal lung and, hence, erroneous interpretation of dorsal hypoventilation/collapse. A transverse plane is suggested for standard EIT monitoring.

The presence of chest tubes, bandages, wounds or skin burns may hinder correct belt placement. EIT devices generally work properly in the absence of 1 or 2 electrode pairs (for 16 and 32 electrode belts, respectively). If the conventional belt position is not possible, a higher belt placement is recommended. In the presence of rib fractures, careful selection of belt size and position is important to avoid any excessive pressure on the chest.

Belt size can be selected according to predefined tables based on the half-chest perimeter (measured from sternum to spine) [2]. Appropriate size selection prior to the measurement allows optimal inter-electrode spacing (overlapping electrodes should be avoided) and skin contact, minimizes the belt’s potential impact on chest wall compliance, and reduces waste with disposables. Electrode-to-skin contact can be improved by applying water, crystalloid fluid, ultrasound gel, or device-specific contact agents, according to the manufacturer. If required for the specific device, the reference electrode should be placed 15–20 cm from the belt’s plane, ideally on the abdomen or shoulder.

After belt positioning, EIT recordings should be started after device calibration (when possible), signal quality check, and a period of signal stability (at least 1 min recommended). Checking for stability after recordings also helps to ensure reliability of EIT measurements.

Synchronized recordings

Simultaneous measurement of EIT with other physiological signals (i.e., respiratory waveforms, esophageal pressure, ECG) facilitates analyses and interpretation. Recording data on a single device is recommended, e.g., using a device-specific connection or flow/pressure sensor attached to the EIT machine. Absolute synchrony between sources can never be guaranteed due to acquisition and processing delays. However, if corresponding breaths are identified in different signals/sources, breath-by-breath comparison is possible. In this case, performing breath-hold maneuvers with different durations during the acquisition serves as a useful reference for (offline) synchronization.

Acquisition challenges and considerations

Several factors need careful attention for reliable EIT acquisition:

Negative inspiratory impedance changes: Diaphragm movement, pleural effusion, pneumothorax, external chest compressions or coughing may induce negative TIV [8]. While some of them are generally considered artifacts (e.g., diaphragmatic movement), others (e.g., pleural effusion, pneumothorax) may have clinical value [12, 13]. Of note, the presence of pneumothorax, pleural effusion and subcutaneous emphysema may impact TIV signal quality, making meaningful interpretations difficult.

End-expiratory lung impedance (EELI) stability: Changes in end-expiratory lung impedance (∆EELI), i.e., due to PEEP adjustments, are frequently used to track changes in end-expiratory lung volume (∆EELV) as both closely correlate [14–17]. However, EELI may also change because of artifacts, such as pulsation of inflatable mattresses, degradation of contact agent, patient movements (active or passive, including bed angle), rapid changes in fluid balance, and belt repositioning [18–23]. ∆EELI calculations over long or multiple recordings should therefore be avoided. Furthermore, since device-specific calibrations and measurements are in arbitrary units (A.U.), absolute EELI and ∆EELI values cannot be compared among different patients. Short-term within-patient EELI changes can be compared, when mitigating artifacts. For between-patient comparisons, absolute EELI cannot be used, even after calibration. As for between-patient comparisons in ∆EELI, a patient-specific calibration (i.e., conversion from A.U. to mL via e.g., spirometry [24] or by recording tidal volumes on the ventilator [25]) has been used, but point-calibrations depend on the lung condition in that setting and therefore should be repeated if lung tissue properties change. Alternatively, the relative percentage change in EELI as compared to TIV can be used.

Electrical-based interference: Active pacemakers/ICD are generally considered a safety contraindication for EIT use, but there is no evidence that modern EIT devices could negatively influence their functioning. However, vice-versa, active pacemakers/ICD can interfere with the EIT recording (creating artifacts in the EIT signal) unless a special artifact filter is enabled on the EIT device. Respiratory electromyography (e.g., for neurally-adjusted ventilator assist (NAVA)) is a passive measurement and therefore does not interfere with the EIT signal if both are properly positioned. In contrast, the EIT signal could potentially influence electromyography recordings. There is no data regarding interactions between EIT signals and respiratory muscle stimulation (e.g., phrenic nerve stimulation).

Repeated measures over long time periods: Longitudinal acquisition is exposed to potential errors, since both belt position and patient factors may differ between acquisition time-points. Marking the belt location with a skin marker can be a reasonable option when repeated measures are planned, to ensure comparability among recordings. While EELI comparisons over multiple recordings should be avoided (see above), the evaluation of tidal ventilation distribution (e.g., % of TV in ROI4) is less affected by longitudinal acquisition artifacts if belt position is preserved.

EIT signal processing

EIT signal processing generally involves: (1) filtering to extract a clean respiratory and/or cardiovascular signal, (2) selection of functional lung regions (i.e., lung segmentation), and/or (3) selection of regions of interest (ROI), if used. Each step alters the EIT signal differently and thus affects the computation and interpretation of parameters, warranting clear reporting.

Signal filtering

EIT acquires voltage data subsequently reconstructed to impedance data and visualized as two-dimensional images (generally 32 × 32 pixels) containing information about lung ventilation and perfusion, heart action, but also disturbances/noise from (un)known sources. Most EIT applications require signal filtering prior to analysis, which can be performed at different stages: pre-reconstruction (filtering voltage data), directly post-reconstruction (filtering pixel impedance data), or after summing pixel impedances to a global or regional tidal impedance signal. Filtering voltage data requires intimate knowledge of the EIT hardware and raw data access, making this option frequently impractical.

Current devices mostly use frequency filters for processing and visualizing data on-device. The cardiovascular signal often is removed with low-pass filters, with a cutoff frequency between the respiratory rate and heart rate. However, this also removes harmonics (i.e., higher frequency details) of the respiratory signal of interest, thus introducing alterations in amplitude, EELI and timing [26].

More sophisticated filters can be considered during offline processing (depending on the use-case), requiring export of unfiltered pixel impedance data and/or disabling filters on-device (Table 1). As phase differences between pixel-level signals might influence the resulting summed impedance signal, we recommend filtering pixel impedance data before summation.

Table 1.

Methods for processing EIT signals

| Method | Specifics | Common pitfalls | Best practices/comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Raw signal (unfiltered) | No filter is applied. Data is as obtained from the device | Manufacturers (can) apply filters during acquisition, reconstruction and before exporting data | Ensure raw data is actually unfiltered before stating so |

| Ensemble averaging |

All features (e.g., breaths or cardiovascular wave) in (part of) a signal are detected and then averaged at a synchronized time. It reduces out-of-sync signals by averaging. The resulting feature can be analysed or used as a template for further detection of features [125] Note that ensemble averaging is not a filtering method per se but should result in a reconstructed signal free of disturbances |

Ensemble averaging requires enough detected instances of a feature to obtain a reliable average. It improves the signal-to-noise ratio of the signal by the square root of the number of repetitions. This technique is therefore not applicable for short sections of a signal When the cardiovascular and respiratory signals share a harmonic, i.e., the heart rate is a multiple of the respiratory rate or vice versa), ensemble averaging might not remove unwanted features Since e.g., cardiovascular noise can shift the position of the minimum and maximum values of breaths, these should not be used to detect the temporal position of breaths |

Preferable method when highly detailed information, e.g., the shape of the expiratory phase of a breath, is required Detection of the temporal position of breaths in EIT data should involve the entire breath shape, not just the start, end or peak of the breath. Alternatively, external signals, like simultaneously recorded and synchronised flow data can be used to identify the temporal position of breaths [126] |

| Frequency filters | Various frequency filters exist: low-pass filter, high-pass filter, band-pass filter, or band-stop filter. Frequency filters are mostly designed as Butterworth or Chebyshev type-II filters, which are infinite impulse response (IIR) filters. In general, finite impulse response (FIR) filters are preferred for better stability and phase response [127] | Most signals, like the respiratory signal, have a base frequency (band) and harmonics. Removal of the base frequency band does not remove the harmonics. Removal of the harmonics changes the shape of the signal, including the exact amplitude (relevant for TIV, small changes in EELI, etc.) and timing (relevant for I:E-ratio, asynchrony, etc.) | As these filters introduce a phase delay (FIR often delays frequency components by the same amount; the delay introduced by IIR is often variable among frequencies), they should be applied twice (forward + backward) to correct for distortions [128] |

| Low-pass filter | To remove high-frequency information like noise, cardiovascular signal, and some movement artifacts | If the cut-off frequency is too low, values might be altered significantly, affecting the results of the analyses | Use a low-pass filter to remove any very high frequency noise (above several multiples of the respiratory rate) Low-pass filters can be used to remove the cardiac signal [129] if one accepts losing high frequency components of the respiratory signal |

| High-pass filter | To remove low-frequency information like drift (e.g., due to changes in electrode conductivity), changes in whole-subject conductivity (e.g., due to changes in fluid status) and slow changes in EELI | High-pass filters remove any signal due to changes in EELI, and therefore is not recommended for use when studying changes in EELI | High-pass filters can be applied when the signal average is assumed constant over time, e.g., for calculation of tidal variations or breath averages |

| Band-pass filter | A band pass filter is a combination of a low-pass and high-pass filter, leaving only the signal with the selected frequency band [130–133] | See general comments for frequency filters | Band-pass filters can be used to extract features with a known small frequency band, like the effects of high frequency oscillatory ventilation [134] |

| Band-stop filter | Band-stop (or notch) filters can remove a specific band of frequencies, like the respiratory signal (for analysis of the cardiovascular signal) | See general comments for frequency filters |

Band-stop filters should be used to filter out disturbances with a known frequency. Consider removing the harmonics as well Can be a very effective filter to remove cardiovascular and other high frequency noise from a stable signal when applied to the cardiovascular frequency and its harmonics in combination with a low-pass and high-pass filter [26] |

| Principal component analysis (PCA) | PCA is aimed at extracting components, a combination of different pixels, that contain the most variance. They have mainly been used to separate the respiratory and cardiovascular signal [127, 135] | ||

| Empirical Mode Decomposition | EMD extracts distinct modes from a signal. Each mode represents a part of the signal within a specific frequency band. A signal, e.g., respiratory or cardiovascular, can be reconstructed from a subset of the modes [26, 135, 136] | The number of modes resulting from EMD is unknown before and depends on the complexity of the signal. Signals from different sources or at different times might require a different mode subset for reconstruction of a signal | The performance of EMD improves with masking, a technique that improves extraction of desirable modes by overlaying a known signal with a similar frequency. The performance can be significantly improved by using complete ensemble empirical mode decomposition with adaptive noise [136] |

| Discrete Wavelet Transform (DWT) | DWT deconstructs a signal into several bands with increasing frequency content based on wavelets. Signals can be reconstructed by selecting one or multiple frequency bands [26, 137] | DWT can remove drift, step-like and spike-like disturbances [137]. Although these methods seem to work in simulated data, it is unknown whether the offset in the resulting signal can be used for EELI-based analyses | The performance of DWT depends on wavelet selection and decomposition levels. Daubechies and Symlet type wavelets with high order perform well in maximal overlap discrete wavelet transform (MODWT), a modified version of DWT [26] |

Lung segmentation and region of interest (ROI) selection

Lung segmentation Since the EIT image comprises the chest portion within the belt plane (e.g., lung, chest wall, air outside the lungs, pleural effusion), lung segmentation aims to identify only lung tissue, thereby excluding non-parenchymal tissue (Additional file 1) [27]. To date, except from reconstruction of lung contouring based on patient’s anthropometric characteristics (i.e., as in the LuMon™ system, Sentec), extracting the total lung contour (including ventilated and non-ventilated lung tissue) directly from the EIT signal is impossible. Functional lung contouring is usually based on a TIV cut-off (typically a percentage of the maximum pixel’s TIV within the analyzed tidal image, e.g., 10–15%) [27, 28] which represents a reasonable choice but excludes non-functional lung regions (e.g., atelectasis). Elimination of the heart region when defining the lung contour should be carefully considered [29].

ROIs A region of interest (ROI) represents a subset of pixels. ROI definition is fundamental to exploit regional analysis of lung behavior as it allows inter-regional comparison within the lung area (e.g., ventral vs. dorsal), for instance to assess the effects of PEEP or positional strategies in term of ventilation re-distribution [30, 31]. ROIs can characterize the spatial ventilation heterogeneity using horizontal layers, vertical layers or quadrants. ROI analysis can be implemented to different images, therefore leading to different results:

Whole EIT image ROIs: The whole EIT image is considered (ventilated + non-ventilated area); this allows the inclusion of hypo-ventilated areas, increasing the discriminatory power of ventilation inhomogeneity [27]. ROIs are defined based on the division of the pixel matrix, often in equidimensional regions (e.g., quadrants, or 4 regions of each 8 pixel rows). However, it is not uncommon for the most dependent ROI to exhibit little or no TIV, since the exact position of the lungs is affected by the patient’s anatomy, device-specific image reconstruction models and belt positioning. This could make the interpretation of the dependent regions difficult.

Functional EIT image ROIs: Only the segmented lung area is considered (functional lung contour), which can ease the comparison between dependent and non-dependent lung regions. Geometrical ROIs (layers/quadrants) can be applied to this functional lung region. However, the definition is purely functional, and the so-defined dorsal region may be different from the dorsal region defined with e.g., CT scan. Recently, a new method for ROI selection was described, where on average, each ROI represents an equal contribution to the TIV of the full EIT recording of interest [19, 32]. This physiological approach is consistent with using the center of ventilation to separate the ventral and dorsal lung but includes multiple layers [32].

Clinical applications: controlled ventilation

Several indices were developed to describe the global, spatial and temporal ventilation distribution, based on the pixel and/or regional variations of impedance (Table 2). When used in conjunction with specific ventilator procedures, EIT provides regional information that may be missed by global respiratory mechanics monitoring alone.

Table 2.

EIT parameters and their applications in different ventilation conditions, for clinical and/or scientific purposes (as per current evidence) as well as bedside availability has been noted

| Ventilatory mode | Purpose | Availability | Comments | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Controlled | Assisted | Non-intubated | Clinical | Research | Bedside | Offline | ||

| VT distribution | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |

| EELI distribution | + | + | + | + / − | + | + | + | EELI dependent |

| Dorsal fraction of ventilation | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |

| CoV | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |

| Global Inhomogeneity | + / − | + / − | + / − | + / − | + / − | − | + | |

| OD-CL | + | + / − | + / − | + | + | + | + | Needs standardization |

| Regional PV-curve | + | − | − | + / − | + | + / − | + | Low-flow insufflation |

| RVD, RVDi | + | − | − | + / − | + | + | + | Low-flow insufflation |

| Silent spaces | + | + | + / − | + | + | + | + | |

| Time constant | + | + / − | + / − | − | + | − | + | |

| EIT-based R/I ratio | + | + / − | + / − | + / − | + | + | + | EELI dependent |

| matching | + | + / − | + / − | + / − | + | + / − | + | Needs saline bolus |

| Volume estimation in SB | NA | NA | + | − | + | + / − | + | |

| Pendelluft detection | + | + | + | + / − | + | + / − | + | |

+ , the expert panel recommend the use of this parameter in this condition; + / − , the expert panel cannot state any recommendation in this condition; − , the expert panel does not recommend the use of this parameter in this condition

Abbreviations: NA, not applicable; CoV, center of ventilation; EELI, end-expiratory lung impedance; CL, lung collapse; OD, overdistension; PV-curve, pressure–volume curve; R/I ratio, recruitment-to-inflation ratio; RVD(i), regional ventilation delay (index); SB, spontaneous breathing; VT, tidal volume; , ventilation-perfusion

EIT to titrate positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP)

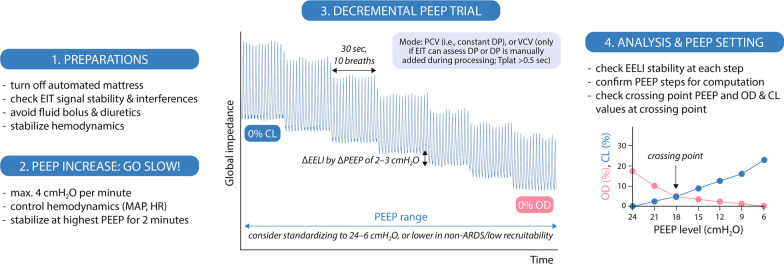

The overdistension and lung collapse (OD-CL) method [3] has been most used in clinical studies [33–39] to assess the impact of PEEP on regional ventilation distribution and titrate PEEP. It involves assessing regional compliance changes, commonly during a decremental PEEP trial: compliance loss towards higher PEEP is interpreted as overdistension (OD), whereas compliance loss towards lower PEEP represents collapsed lung (CL). The optimal PEEP is then usually considered the one found at the intersection of the collapse and overdistension curves [3]: the PEEP that jointly minimizes both phenomena. This also assumes that collapse and overdistension contribute equally to ventilator-induced lung injury (VILI), but in some conditions this may not be true [40]. Nevertheless, a recent meta-analysis demonstrated that this strategy for individualizing PEEP improves respiratory mechanics and potentially outcomes in ARDS [36].

The OD-CL method requires driving pressure measurement to estimate regional compliance and should therefore be performed in volume-controlled ventilation (with inspiratory pause > 0.5 s and no intrinsic PEEP), when driving pressure can be automatically collected by the EIT machine or is added by the operator in post-processing. Otherwise, pressure-controlled mode, with constant support level and with sufficient time for equilibration between alveolar and airway pressures at end-inspiration and end-expiration (no-flow state), should be used.

Importantly, since relative regional compliance changes are computed and thus relative collapse and overdistension (i.e., highest PEEP = 0% collapse, lowest PEEP = 0% overdistension), the chosen PEEP range affects results [41]. Any remaining collapse at the highest PEEP level (as per CT scan) is not visible on EIT. Hence, the optimal PEEP reflects the PEEP able to jointly minimize relative collapse and overdistension only in the explored PEEP range. To improve reliability and inter-patient comparisons, a standardized PEEP window (e.g., from 24 to 6 cm H2O, as previously done [35]) is preferable, especially for clinical trials. If a narrower range is applied, especially in non-ARDS or poorly recruitable lungs, a crossing point close to the boundaries (e.g., < 3 cm H2O away from the highest or lowest PEEP step) may be an incentive to consider a wider PEEP range. We also recommend that for intra-patient comparisons, the PEEP range and steps are kept constant if the PEEP trial is repeated over time. Nevertheless, in each clinical setting, physicians should choose the acceptable PEEP range according to the condition of the patients, being aware of the possible issues associated with smaller PEEP windows. We summarize the OD-CL method with step-by-step recommendations in Fig. 2. Other EIT-based methods for individualized PEEP setting different from the decremental PEEP trial have also been explored [42], such as evaluating changes in EELI with PEEP.

Fig. 2.

EIT-based PEEP titration: step-by-step recommendations. The PEEP selection is generally made at the crossing point of the OD and CL curves; if the crossing point is between two PEEP levels, values are usually rounded up to the nearest integer. Abbreviations: ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome; DP, driving pressure; EELI, end-expiratory lung impedance; EIT, electrical impedance tomography; HR, heart rate; CL, lung collapse; MAP, mean arterial pressure; OD, overdistension, PEEP, positive end-expiratory pressure; PCV, pressure-controlled ventilation; Tplat, time (duration) of plateau pressure; VCV, volume-controlled ventilation

Evaluating the impact of specific procedures/interventions and position

Real-time EIT monitoring can help in the detection of selective bronchial intubation [43, 44], can show derecruitment induced by endotracheal suctioning [45] or broncho-alveolar lavage [46] and may help targeting broncho-alveolar lavage areas [47, 48]. In addition, EIT can be useful to predict the effect of patient positioning. For example, the effect of prone position estimated by EIT could predict the forthcoming gas exchange response [49], while TIV and EELI variations could inform about the effects of both prone and lateral positioning [49–52]. EIT could also guide PEEP settings during prone positioning [53, 54], but the impact on patients’ outcomes remains to be evaluated. Clinicians must be aware that patient mobilization could also lead to changes in TIV and EELI, which should not be interpreted as changes in aeration/ventilation solely.

Evaluate VILI determinants

The reconstruction of global and regional pressure-impedance curves and of the corresponding regional inflection points may inform about regional overdistension or collapse [55–57]. For instance, regional intra-tidal recruitment, reflecting regional overdistension [58], has been quantified by the regional ventilation delay (RVD) index [59] or concavity indices [60]. EIT-based regional lung opening and closing pressures [61] may be particularly useful in patients with asymmetric lung injury [62]. Currently, bedside availability of these parameters and evidence for their routine use is limited, but may help to dynamically titrate tidal volume based on its regional effects [63]. Clinicians can combine PEEP titration results with tidal volume guidance from EIT for improving lung protection [64], also in addition to other techniques, such as extracorporeal life support (ECCO2R or ECMO).

Clinical applications: spontaneous breathing

EIT may offer valuable insights to safely manage spontaneous breathing in patients with acute hypoxemic respiratory failure who are at risk of P-SILI [65] and guide both weaning/extubation and post-extubation phases. In addition, EIT revealed expiratory muscle recruitment in ARDS patients, evidenced by an increase in EELI after paralysis [66]. EIT has been used for monitoring the effect of different non-invasive respiratory support modalities (i.e., interfaces, modes, settings) and interventions (e.g., changes in body position) on the ventilation distribution and regional mechanics [4, 67, 68]. However, measurements of both respiratory mechanics and EIT are challenging in awake patients [2], due to the large variability in breathing patterns and various movement artifacts. Therefore, only a subset of EIT parameters can be used in this setting (Table 2). To enhance reliability, we suggest careful selection of stable breathing phases and (manual) removal of artifacts if present.

Monitoring tidal volume and respiratory rate

EIT offers a valuable non-invasive estimate of tidal volume as impedance changes strongly correlate with lung volume changes [16, 69–71]. However, computation of absolute tidal volumes with EIT is more complex, requiring a factor to convert tidal volume to TIV (i.e., k = VT/TIV). This factor can be obtained reliably during invasive ventilation, but needs a point calibration with known tidal volumes in non-intubated patients (e.g., via spirometry [24], or simpler calibration bag method [71]), which is often not practical/feasible and guarantees only short-term stability (i.e., only within one recording). Nevertheless, regional TIV distribution assessment is feasible without point calibration and provides potentially useful insights on regional strain.

EIT also allows accurate monitoring of respiratory rate during spontaneous breathing [72]. This facilitates EIT-based estimations of changes in minute volume, when combined with TIV [22].

PEEP titration

Compared to controlled ventilation, PEEP titration in assisted ventilation presents additional challenges due to the variability of respiratory effort, inaccurate measurements of respiratory compliance [73] and hemodynamic fluctuations [74]. Recently, the regional peak inspiratory flow at different PEEP steps was suggested as parameter to quantify regional mechanics during spontaneous breathing [75], and EIT and dynamic transpulmonary pressure were integrated to identify the PEEP that jointly minimizes lung collapse and overdistension during pressure support ventilation [76]. However, limitations and technical challenges remain, related to EIT signal stability, time-consuming offline analysis, need for esophageal manometry and uncertain accuracy in patients with increased airway resistance.

Weaning

When applied during the spontaneous breathing trial, monitoring regional TIV, de-recruitment and regional inhomogeneities may inform about weaning success [77, 78]. For instance, a reduction in EELI [79–81], higher global inhomogeneity index [22] and pendelluft [82, 83] have been associated with spontaneous breathing trial and/or extubation failure. The predictive role of these parameters to guide weaning remains to be assessed.

Patient-ventilator interaction

Utilizing the temporal and spatial ventilation distribution information, EIT enables patient-ventilator interaction monitoring and dyssynchronies diagnosis [84]. When combined with flow and/or airway pressure signals, the regional impact of dyssynchronies can be quantified [85, 86], e.g., in terms of ventilation distribution and regional overdistension.

Pendelluft

Pendelluft, is ‘the volume of gas passing back and forth between two pathways’ [87] and the consequence of inhomogeneities in regional resistances and/or compliances. EIT revealed the occurrence of pendelluft [88] which was correlated with regional inflammation; both could be modulated by PEEP [88]. Negative associations with outcome have been reported [83, 89] but the causal clinical impact remains to be investigated.

EIT is the only technique capable of identifying pendelluft in real-time. Pendelluft measurements during spontaneous breathing have been used to: (1) describe how different ventilatory settings may affect regional time constants, regional resistances and compliances [90], (2) describe the air movement between dependent and non-dependent lung regions during inspiration [85, 91–93], and (3) compute the difference between global and regional redistribution of gas during the respiratory cycles [4, 68, 94]. Various EIT-based definitions/computations have been proposed in different scenarios (Additional file 2).

Ventilation-perfusion matching

EIT is a promising monitor for regional ventilation-to-perfusion () distribution: the ratio of regional alveolar ventilation (ml air/min) to regional blood flow (ml blood/min). EIT-based can be performed easily at the bedside and repeated over time, providing important advantages as compared to other imaging techniques (i.e., CT, SPECT) or to Multiple Inert Gas Elimination Technique (MIGET), which provide only aggregate results of mismatch. In patients with respiratory failure, EIT assessment can improve our understanding of gas exchange abnormalities, and allows to evaluate the effects of procedures or ventilator settings on regional (e.g., PEEP adjustment [95], prone positioning [96] and adjunctive therapies, like nitric oxide [97, 98]). Whereas ventilation-related EIT signals are large and reasonably well understood, the technique is still relatively new in the clinical context and only a preliminary consensus on its use is possible at this time.

Perfusion has been measured via (1) conductivity-contrasting bolus injection (Bolus technique, Fig. 3), and (2) through filtering of the pulsatile heart-beat component of EIT signals (Pulsatility technique). The bolus technique showed better agreement with both SPECT [99] and PET [100] and is currently the reference for EIT-based assessment.

Fig. 3.

Illustration of ventilation-perfusion assessment by EIT. Waveforms and images from ref. [124] in a patient after pulmonary endarterectomy. A EIT waveforms before and during a NaCl bolus and apnea (38–50 s) in four lung quadrants. B Tidal ventilation image prior to the NaCl bolus and apnea. C Bolus-based perfusion image. The red/yellow indicate the conductivity change during the lung perfusion phase (at approximately 47 s) of the bolus. This is only in the left lung due to the patient’s perfusion defect. D Heart rate-filtered EIT image. E Relative EIT- image in the lung region of interest. The color scales used are shown using a log-scale such that 1 indicates mean equal perfusion and ventilation distribution. No consensus for EIT perfusion or color scales is available. Abbreviations: RV = right ventral, LV = left ventral, RD = right dorsal, LD = left dorsal

Bolus technique: procedure

Using a central line catheter, a contrast agent, usually 10 mL of hypertonic saline (usually 5–10% NaCl) [100] is injected rapidly (in 1–2 s) during a breath-hold of 8–15 s [101]. EIT images of Q are then calculated by subtraction of the heart pixels [99], whereas the V̇ component is calculated by filtering the pre-apnea ventilation signal to remove heart rate-related components [26] and pixel-by-pixel matching can be determined [102]. Software to automatically process these EIT data to calculate images at the bedside is required. If independent measures of minute ventilation and cardiac output are available, a calibrated image can be calculated [103]; else, the EIT- image is unitless (the relative image).

Considerations and open questions

A concern may arise regarding the electrolytes load of the saline bolus. Nevertheless, the salt load of the injected bolus is relatively small (10 mL 5% saline bolus corresponds to 0.5 g (8.5 mEq) of NaCl), and no adverse effects of electrolyte disturbances after rapid or repeated bolus administration have been reported to date. However, it is unclear how the 10 mL requirement scales with patient mass, blood volume and cardiac output. Several promising new contrast agents were proposed [104] and are currently under investigation [105]. Recent data demonstrated the feasibility of calculating EIT-derived without apnea, providing new perspectives on its application when breath-holds are difficult, e.g., during spontaneous breathing [106].

Standardized EIT reporting in clinical and experimental studies

Considering the impact of the different variables during EIT acquisition, processing and interpretation, we believe that a minimum requirement for EIT reporting would allow traceability, reproducibility and comparability of EIT studies. We therefore propose minimum standards for scientific reporting of EIT in clinical and experimental studies (see Additional file 3). This could provide guidance to researchers and facilitate sustainable implementation of EIT for individualization of ventilation management and stimulate development of standardized open-source analyses pipelines (e.g., ALIVE [107]).

Future directions

In the last two decades, EIT application has considerably increased, both for technological advances and for a better understanding of respiratory physiology in different settings and under different conditions. Here, we highlight novel future directions that have not yet been discussed above.

Diagnosing non-ventilated areas

EIT can evaluate regional ventilation, but no specific information can be obtained from the absence of ventilation, either determined by physiological (e.g., the ribcage, mediastinum) or pathological (e.g., pleural effusion, overdistension, pneumothorax) entities. Hypo-ventilated lung areas can be identified (i.e., silent spaces [108]) but lung contouring is not available on all devices and may require individual adjustments [109]. One open question is therefore how to further characterize non-ventilated areas and how to differentiate tissue properties with EIT. Absolute EIT (aEIT), often used in the 1980s and 1990s, evaluates the regional absolute impedance values and not, as the dynamic EIT (dEIT), its changes over time [110]. By allowing measuring different tissues conductivities, aEIT could potentially distinguish between structures, therefore improving the understanding of hypo-ventilated areas.

Devices for simultaneous multi-frequency measurements have already been reported [111–115] but most of the current clinical/commercial EIT devices are based on a single frequency and imaging algorithms for multi-frequency EIT are still under-developed [116, 117]. The reliable detection of atelectasis and its differentiation from pleural effusion, pneumothorax and overdistension according to its spectroscopic properties could be a promising future application of multi-frequency EIT.

3D-EIT

EIT monitoring of a single horizontal thoracic slice with a spatial resolution of about 2–3 cm is reasonable for many clinical applications. However, best spatial resolution is limited to the regions located closer to the belt. Movement of the lung and cardiac structures within the electrode plane, e.g., during a PEEP trial, can cause artifacts that can be misinterpreted as recruitment or overdistension. A potential solution is to create EIT images in 3D [118, 119], by placing two belts for simultaneous recording and analyzing them with 3D reconstruction algorithms [120, 121]. 3D-EIT could also improve image quality by correcting for out-of-plane changes in impedance and has the potential of enhancing the reliability of EIT-based assessment, since lung perfusion is anatomically clearer than in 2D [121]. We encourage further research on 3D-EIT and the development of devices for clinical applications.

Machine learning applications

In the year 2024 it would be an omission not to mention machine learning in a section on future perspectives of any technology, and EIT makes no exception. Yet only few applications have been published, including deep learning models for image reconstruction [122] and feature extraction for predicting spirometry data and circulatory parameters [123]. We see potential for machine learning to be valuable at multiple stages. For instance: image reconstruction (also for 3D-EIT), lung contour detection, signal filtering, artifact detection and eventually correction, and facilitating in complex analyses. Ideally, such applications should use raw voltage data instead of reconstructed impedance signals since these are already highly processed on-device to serve the human eye at the bedside.

Conclusion

EIT is a powerful technology for the non-invasive monitoring of regional distribution of ventilation and perfusion, offering real-time and continuous data that can greatly enhance our understanding and management of various respiratory and circulatory conditions. Its application may be especially beneficial for critically ill mechanically ventilated patients, providing insights that can guide the optimization of ventilatory support, assess the effectiveness of therapeutic interventions, and potentially improve outcomes. Through continued innovation, rigorous validation, and collaborative efforts to standardize practices, EIT can become an indispensable tool in the clinician's arsenal, ultimately improving patient care and outcomes in critical care.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

Illustrations (Figure 1 and 2) were made by Annemijn H. Jonkman.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the drafting of the manuscript according to their area of expertise. GS, BP, TB and AHJ formed the core writing team for defining sections and preparing the synthesis manuscript. AHJ illustrated Figs. 1–2, AA prepared Fig. 3. All authors have provided feedback on the full manuscript and read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The 4-day meeting and associated expenses were supported by the Netherlands eScience Center (grant number NLESC.OEC.2022.002) and the Lorentz Center, Sentec and Sciospec. These sponsors had no influence in the writing of this report.

Availability of data and materials

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethical approval and consent for participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

LSM is supported by a fellowship from the European Respiratory Society and a scholarship from Canadian Lung Society. SL has received EIT-related research funding under grant LE 817/40–1 (Project No. 422367304, paid to the institution) from German Research Foundation (DFG). AJ is supported by a personal grant from NWO (ZonMw Veni 2022, 09150162210061, paid to the institution) and has received research funding (paid to the institution) from Pulmotech B.V., Liberate Medical, Netherlands eScience Center and Health ~ Holland. All other authors declared that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Franchineau G, Jonkman AH, Piquilloud L, et al. Electrical impedance tomography to monitor hypoxemic respiratory failure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2023. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Frerichs I, Amato MB, van Kaam AH, et al. Chest electrical impedance tomography examination, data analysis, terminology, clinical use and recommendations: consensus statement of the TRanslational EIT developmeNt stuDy group. Thorax. 2017;72(1):83–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Costa EL, Borges JB, Melo A, et al. Bedside estimation of recruitable alveolar collapse and hyperdistension by electrical impedance tomography. Intensive Care Med. 2009;35(6):1132–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grieco DL, Delle Cese L, Menga LS, et al. Physiological effects of awake prone position in acute hypoxemic respiratory failure. Crit Care. 2023;27(1):315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jimenez JV, Weirauch AJ, Culter CA, et al. Electrical impedance tomography in acute respiratory distress syndrome management. Crit Care Med. 2022;50(8):1210–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wisse JJ, Scaramuzzo G, Pellegrini M, et al. Clinical implementation of advanced respiratory monitoring with esophageal pressure and electrical impedance tomography: results from an international survey and focus group discussion. Intensive Care Med Exp. 2024;12(1):93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yue C, He H, Su L, et al. A novel method for diaphragm-based electrode belt position of electrical impedance tomography by ultrasound. J Intensive Care. 2023;11(1):41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Karsten J, Stueber T, Voigt N, et al. Influence of different electrode belt positions on electrical impedance tomography imaging of regional ventilation: a prospective observational study. Crit Care. 2016;20:3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bikker IG, Preis C, Egal M, et al. Electrical impedance tomography measured at two thoracic levels can visualize the ventilation distribution changes at the bedside during a decremental positive end-expiratory lung pressure trial. Crit Care. 2011;15(4):R193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krueger-Ziolek S, Schullcke B, Kretschmer J, et al. Positioning of electrode plane systematically influences EIT imaging. Physiol Meas. 2015;36(6):1109–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sophocleous L, Waldmann AD, Becher T, et al. Effect of sternal electrode gap and belt rotation on the robustness of pulmonary electrical impedance tomography parameters. Physiol Meas. 2020;41(3): 035003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Costa EL, Chaves CN, Gomes S, et al. Real-time detection of pneumothorax using electrical impedance tomography. Crit Care Med. 2008;36(4):1230–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alves SH, Amato MB, Terra RM, et al. Lung reaeration and reventilation after aspiration of pleural effusions. A study using electrical impedance tomography. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2014;11(2):186–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mauri T, Eronia N, Turrini C, et al. Bedside assessment of the effects of positive end-expiratory pressure on lung inflation and recruitment by the helium dilution technique and electrical impedance tomography. Intensive Care Med. 2016;42(10):1576–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bikker IG, Leonhardt S, Bakker J, Gommers D. Lung volume calculated from electrical impedance tomography in ICU patients at different PEEP levels. Intensive Care Med. 2009;35(8):1362–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hinz J, Hahn G, Neumann P, et al. End-expiratory lung impedance change enables bedside monitoring of end-expiratory lung volume change. Intensive Care Med. 2003;29(1):37–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meier T, Luepschen H, Karsten J, et al. Assessment of regional lung recruitment and derecruitment during a PEEP trial based on electrical impedance tomography. Intensive Care Med. 2008;34(3):543–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Frerichs I, Pulletz S, Elke G, et al. Patient examinations using electrical impedance tomography–sources of interference in the intensive care unit. Physiol Meas. 2011;32(12):L1-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Van Oosten JP, Francovich JE, Somhorst P, et al. Flow-controlled ventilation decreases mechanical power in postoperative ICU patients. Intensive Care Med Exp. 2024;12(1):30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Becher T, Wendler A, Eimer C, et al. Changes in electrical impedance tomography findings of ICU Patients during rapid infusion of a fluid bolus: a prospective observational study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;199(12):1572–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vogt B, Mendes L, Chouvarda I, et al. Influence of torso and arm positions on chest examinations by electrical impedance tomography. Physiol Meas. 2016;37(6):904–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wisse JJ, Goos TG, Jonkman AH, et al. Electrical Impedance Tomography as a monitoring tool during weaning from mechanical ventilation: an observational study during the spontaneous breathing trial. Respir Res. 2024;25(1):179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Spooner AJ, Corley A, Sharpe NA, et al. Head-of-bed elevation improves end-expiratory lung volumes in mechanically ventilated subjects: a prospective observational study. Respir Care. 2014;59(10):1583–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mauri T, Alban L, Turrini C, et al. Optimum support by high-flow nasal cannula in acute hypoxemic respiratory failure: effects of increasing flow rates. Intensive Care Med. 2017;43(10):1453–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jang GY, Ayoub G, Kim YE, et al. Integrated EIT system for functional lung ventilation imaging. Biomed Eng Online. 2019;18(1):83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wisse JJ, Somhorst P, Behr J, et al. Improved filtering methods to suppress cardiovascular contamination in electrical impedance tomography recordings. Physiol Meas. 2024;45(5):055010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Becher T, Vogt B, Kott M, et al. Functional regions of interest in electrical impedance tomography: a secondary analysis of two clinical studies. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(3): e0152267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pulletz S, van Genderingen HR, Schmitz G, et al. Comparison of different methods to define regions of interest for evaluation of regional lung ventilation by EIT. Physiol Meas. 2006;27(5):S115–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Borgmann S, Linz K, Braun C, et al. Lung area estimation using functional tidal electrical impedance variation images and active contouring. Physiol Meas. 2022;43(7):075010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Katira BH, Osada K, Engelberts D, et al. Positive end-expiratory pressure, pleural pressure, and regional compliance during pronation: an experimental study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2021;203(10):1266–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Taenaka H, Yoshida T, Hashimoto H, et al. Personalized ventilatory strategy based on lung recruitablity in COVID-19-associated acute respiratory distress syndrome: a prospective clinical study. Crit Care. 2023;27(1):152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Francovich J, Somhorst P, Gommers D, et al. Physiological definition for region of interest selection in electrical impedance tomography data: description and validation of a novel method. Physiol Meas. 2024. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Zhao Z, Chang MY, Chang MY, et al. Positive end-expiratory pressure titration with electrical impedance tomography and pressure-volume curve in severe acute respiratory distress syndrome. Ann Intensive Care. 2019;9(1):7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Costa ELV, Alcala GC, Tucci MR, et al. Impact of extended lung protection during mechanical ventilation on lung recovery in patients with COVID-19 ARDS: a phase II randomized controlled trial. Ann Intensive Care. 2024;14(1):85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jonkman AH, Alcala GC, Pavlovsky B, et al. Lung recruitment assessed by electrical impedance tomography (RECRUIT): a multicenter study of COVID-19 acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2023;208(1):25–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Songsangvorn N, Xu Y, Lu C, et al. Electrical impedance tomography-guided positive end-expiratory pressure titration in ARDS: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Intensive Care Med. 2024;50(5):617–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Puel F, Crognier L, Soule C, et al. Assessment of electrical impedance tomography to set optimal positive end-expiratory pressure for veno-venous ECMO-treated severe ARDS patients. J Crit Care. 2020;60:38–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wong H, Chi Y, Zhang R, et al. Multicentre, parallel, open-label, two-arm, randomised controlled trial on the prognosis of electrical impedance tomography-guided versus low PEEP/FiO2 table-guided PEEP setting: a trial protocol. BMJ Open. 2024;14(2): e080828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.He H, Chi Y, Yang Y, et al. Early individualized positive end-expiratory pressure guided by electrical impedance tomography in acute respiratory distress syndrome: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Crit Care. 2021;25(1):230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sousa MLA, Katira BH, Bouch S, et al. Limiting overdistention or collapse when mechanically ventilating injured lungs: a randomized study in a porcine model. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2024;209(12):1441–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pavlovsky B, Desprez C, Richard JC, et al. Bedside personalized methods based on electrical impedance tomography or respiratory mechanics to set PEEP in ARDS and recruitment-to-inflation ratio: a physiologic study. Ann Intensive Care. 2024;14(1):1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Frerichs I, Schadler D, Becher T. Setting positive end-expiratory pressure by using electrical impedance tomography. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2024;30(1):43–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Steinmann D, Engehausen M, Stiller B, Guttmann J. Electrical impedance tomography for verification of correct endotracheal tube placement in paediatric patients: a feasibility study. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2013;57(7):881–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Steinmann D, Stahl CA, Minner J, et al. Electrical impedance tomography to confirm correct placement of double-lumen tube: a feasibility study. Br J Anaesth. 2008;101(3):411–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tingay DG, Copnell B, Grant CA, et al. The effect of endotracheal suction on regional tidal ventilation and end-expiratory lung volume. Intensive Care Med. 2010;36(5):888–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Frerichs I, Dargaville PA, Rimensberger PC. Regional pulmonary effects of bronchoalveolar lavage procedure determined by electrical impedance tomography. Intensive Care Med Exp. 2019;7(1):11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fu Y, Zou R, Wang S, et al. Monitoring bronchoalveolar lavage with electrical impedance tomography: first experience in a patient with COVID-19. Physiol Meas. 2020;41(8): 085008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Grieco DL, Mura B, Bisanti A, et al. Electrical impedance tomography to monitor lung sampling during broncho-alveolar lavage. Intensive Care Med. 2016;42(6):1088–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang YX, Zhong M, Dong MH, et al. Prone positioning improves ventilation-perfusion matching assessed by electrical impedance tomography in patients with ARDS: a prospective physiological study. Crit Care. 2022;26(1):154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mlcek M, Otahal M, Borges JB, et al. Targeted lateral positioning decreases lung collapse and overdistension in COVID-19-associated ARDS. BMC Pulm Med. 2021;21(1):133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Roldan R, Rodriguez S, Barriga F, et al. Sequential lateral positioning as a new lung recruitment maneuver: an exploratory study in early mechanically ventilated Covid-19 ARDS patients. Ann Intensive Care. 2022;12(1):13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Araujo Morais CC, Alcala G, Diaz Delgado E, et al. PEEP titration in supine and prone position reveals different respiratory mechanics in severe COVID-19. Respir Care. 2021;66(Suppl 10):3612140. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mi L, Chi Y, Yuan S, et al. Effect of prone positioning with individualized positive end-expiratory pressure in acute respiratory distress syndrome using electrical impedance tomography. Front Physiol. 2022;13: 906302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Franchineau G, Brechot N, Hekimian G, et al. Prone positioning monitored by electrical impedance tomography in patients with severe acute respiratory distress syndrome on veno-venous ECMO. Ann Intensive Care. 2020;10(1):12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Scaramuzzo G, Spadaro S, Waldmann AD, et al. Heterogeneity of regional inflection points from pressure-volume curves assessed by electrical impedance tomography. Crit Care. 2019;23(1):119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.van Genderingen HR, van Vught AJ, Jansen JR. Estimation of regional lung volume changes by electrical impedance pressures tomography during a pressure-volume maneuver. Intensive Care Med. 2003;29(2):233–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kunst PW, de Anda GV, Bohm SH, et al. Monitoring of recruitment and derecruitment by electrical impedance tomography in a model of acute lung injury. Crit Care Med. 2000;28(12):3891–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Scaramuzzo G, Spinelli E, Spadaro S, et al. Gravitational distribution of regional opening and closing pressures, hysteresis and atelectrauma in ARDS evaluated by electrical impedance tomography. Crit Care. 2020;24(1):622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Muders T, Luepschen H, Zinserling J, et al. Tidal recruitment assessed by electrical impedance tomography and computed tomography in a porcine model of lung injury*. Crit Care Med. 2012;40(3):903–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hinz J, Gehoff A, Moerer O, et al. Regional filling characteristics of the lungs in mechanically ventilated patients with acute lung injury. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2007;24(5):414–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pulletz S, Adler A, Kott M, et al. Regional lung opening and closing pressures in patients with acute lung injury. J Crit Care. 2012;27(3):323–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Roze H, Boisselier C, Bonnardel E, et al. Electrical impedance tomography to detect airway closure heterogeneity in asymmetrical acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2021;203(4):511–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Becher T, Buchholz V, Hassel D, et al. Individualization of PEEP and tidal volume in ARDS patients with electrical impedance tomography: a pilot feasibility study. Ann Intensive Care. 2021;11(1):89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Franchineau G, Brechot N, Lebreton G, et al. Bedside contribution of electrical impedance tomography to setting positive end-expiratory pressure for extracorporeal membrane oxygenation-treated patients with severe acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;196(4):447–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Brochard L, Slutsky A, Pesenti A. Mechanical ventilation to minimize progression of lung injury in acute respiratory failure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;195(4):438–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Plens GM, Droghi MT, Alcala GC, et al. Expiratory muscle activity counteracts positive end-expiratory pressure and is associated with fentanyl dose in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2024;209(5):563–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mauri T, Turrini C, Eronia N, et al. Physiologic effects of high-flow nasal cannula in acute hypoxemic respiratory failure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;195(9):1207–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Menga LS, Delle Cese L, Rosa T, et al. Respective effects of helmet pressure support, continuous positive airway pressure, and nasal high-flow in hypoxemic respiratory failure: a randomized crossover clinical trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2023;207(10):1310–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Frerichs I, Hahn G, Hellige G. Thoracic electrical impedance tomographic measurements during volume controlled ventilation-effects of tidal volume and positive end-expiratory pressure. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 1999;18(9):764–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Grivans C, Lundin S, Stenqvist O, Lindgren S. Positive end-expiratory pressure-induced changes in end-expiratory lung volume measured by spirometry and electric impedance tomography. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2011;55(9):1068–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sosio S, Bellani G, Villa S, et al. A calibration technique for the estimation of lung volumes in nonintubated subjects by electrical impedance tomography. Respiration. 2019;98(3):189–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wisse JJ, Flinsenberg MJW, Jonkman AH, et al. Respiratory rate monitoring in ICU patients and healthy volunteers using electrical impedance tomography: a validation study. Physiol Meas. 2024;45(5):055026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Stamatopoulou V, Akoumianaki E, Vaporidi K, et al. Driving pressure of respiratory system and lung stress in mechanically ventilated patients with active breathing. Crit Care. 2024;28(1):19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Carvalho AR, Spieth PM, Pelosi P, et al. Pressure support ventilation and biphasic positive airway pressure improve oxygenation by redistribution of pulmonary blood flow. Anesth Analg. 2009;109(3):856–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Heines SJH, de Jongh SAM, de Jongh FHC, et al. A novel positive end-expiratory pressure titration using electrical impedance tomography in spontaneously breathing acute respiratory distress syndrome patients on mechanical ventilation: an observational study from the MaastrICCht cohort. J Clin Monit Comput. 2024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 76.Slobod D, Leali M, Spinelli E, et al. Integrating electrical impedance tomography and transpulmonary pressure monitoring to personalize PEEP in hypoxemic patients undergoing pressure support ventilation. Crit Care. 2022;26(1):314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bickenbach J, Czaplik M, Polier M, et al. Electrical impedance tomography for predicting failure of spontaneous breathing trials in patients with prolonged weaning. Crit Care. 2017;21(1):177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Zhao Z, Peng SY, Chang MY, et al. Spontaneous breathing trials after prolonged mechanical ventilation monitored by electrical impedance tomography: an observational study. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2017;61(9):1166–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Longhini F, Maugeri J, Andreoni C, et al. Electrical impedance tomography during spontaneous breathing trials and after extubation in critically ill patients at high risk for extubation failure: a multicenter observational study. Ann Intensive Care. 2019;9(1):88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lima JNG, Fontes MS, Szmuszkowicz T, et al. Electrical impedance tomography monitoring during spontaneous breathing trial: Physiological description and potential clinical utility. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2019;63(8):1019–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Joussellin V, Bonny V, Spadaro S, et al. Lung aeration estimated by chest electrical impedance tomography and lung ultrasound during extubation. Ann Intensive Care. 2023;13(1):91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Wang D, Ning Y, He L, et al. Pendelluft as a predictor of weaning in critically ill patients: an observational cohort study. Front Physiol. 2023;14:1113379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Liu W, Chi Y, Zhao Y, et al. Occurrence of pendelluft during ventilator weaning with T piece correlated with increased mortality in difficult-to-wean patients. J Intensive Care. 2024;12(1):23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Damiani LF, Bruhn A, Retamal J, Bugedo G. Patient-ventilator dyssynchronies: are they all the same? a clinical classification to guide actions. J Crit Care. 2020;60:50–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Lin WC, Su PF, Chen CW. Pendelluft in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome during trigger and reverse triggering breaths. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):22143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Bachmann MC, Morais C, Bugedo G, et al. Electrical impedance tomography in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care. 2018;22(1):263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Otis AB, McKerrow CB, Bartlett RA, et al. Mechanical factors in distribution of pulmonary ventilation. J Appl Physiol. 1956;8(4):427–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Yoshida T, Torsani V, Gomes S, et al. Spontaneous effort causes occult pendelluft during mechanical ventilation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;188(12):1420–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Chi Y, Zhao Z, Frerichs I, et al. Prevalence and prognosis of respiratory pendelluft phenomenon in mechanically ventilated ICU patients with acute respiratory failure: a retrospective cohort study. Ann Intensive Care. 2022;12(1):22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Santini A, Mauri T, Dalla Corte F, et al. Effects of inspiratory flow on lung stress, pendelluft, and ventilation heterogeneity in ARDS: a physiological study. Crit Care. 2019;23(1):369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Coppadoro A, Grassi A, Giovannoni C, et al. Occurrence of pendelluft under pressure support ventilation in patients who failed a spontaneous breathing trial: an observational study. Ann Intensive Care. 2020;10(1):39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Arellano DH, Brito R, Morais CCA, et al. Pendelluft in hypoxemic patients resuming spontaneous breathing: proportional modes versus pressure support ventilation. Ann Intensive Care. 2023;13(1):131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Gattinoni L, Caironi P, Cressoni M, et al. Lung recruitment in patients with the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(17):1775–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Sang L, Zhao Z, Yun PJ, et al. Qualitative and quantitative assessment of pendelluft: a simple method based on electrical impedance tomography. Ann Transl Med. 2020;8(19):1216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Pavlovsky B, Pesenti A, Spinelli E, et al. Effects of PEEP on regional ventilation-perfusion mismatch in the acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care. 2022;26(1):211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Scaramuzzo G, Ball L, Pino F, et al. Influence of positive end-expiratory pressure titration on the effects of pronation in acute respiratory distress syndrome: a comprehensive experimental study. Front Physiol. 2020;11:179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.He H, Chi Y, Long Y, et al. Bedside evaluation of pulmonary embolism by saline contrast electrical impedance tomography method: a prospective observational study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;202(10):1464–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Pellegrini M, Sousa MLA, Dubo S, et al. Impact of airway closure and lung collapse on inhaled nitric oxide effect in acute lung injury: an experimental study. Ann Intensive Care. 2024;14(1):149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Borges JB, Suarez-Sipmann F, Bohm SH, et al. Regional lung perfusion estimated by electrical impedance tomography in a piglet model of lung collapse. J Appl Physiol. 2012;112(1):225–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Bluth T, Kiss T, Kircher M, et al. Measurement of relative lung perfusion with electrical impedance and positron emission tomography: an experimental comparative study in pigs. Br J Anaesth. 2019;123(2):246–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Xu M, He H, Long Y. Lung perfusion assessment by bedside electrical impedance tomography in critically ill patients. Front Physiol. 2021;12: 748724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Spinelli E, Kircher M, Stender B, et al. Unmatched ventilation and perfusion measured by electrical impedance tomography predicts the outcome of ARDS. Crit Care. 2021;25(1):192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Leali M, Marongiu I, Spinelli E, et al. Absolute values of regional ventilation-perfusion mismatch in patients with ARDS monitored by electrical impedance tomography and the role of dead space and shunt compensation. Crit Care. 2024;28(1):241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Gaulton TG, Martin K, Xin Y, et al. Regional lung perfusion using different indicators in electrical impedance tomography. J Appl Physiol. 2023;135(3):500–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Muders T, Hentze B, Leonhardt S, Putensen C. Evaluation of different contrast agents for regional lung perfusion measurement using electrical impedance tomography: an experimental pilot study. J Clin Med. 2023;12(8):2751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Victor M, Xin Y, Alcala G, et al. First-pass kinetics model to estimate pulmonary perfusion by electrical impedance tomography during uninterrupted breathing. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2024;209(10):1263–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Somhorst P, Bodor, D., Wisse-Smit, J., Francovich, J., Baccinelli, W., Jonkman, A. Eitprocessing (Version 1.1.0) [Computer software]. 2023. 10.5281/zenodo.7869553.

- 108.Spadaro S, Mauri T, Bohm SH, et al. Variation of poorly ventilated lung units (silent spaces) measured by electrical impedance tomography to dynamically assess recruitment. Crit Care. 2018;22(1):26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Yang L, Fu F, Frerichs I, et al. The calculation of electrical impedance tomography based silent spaces requires individual thorax and lung contours. Physiol Meas. 2022;43(9):09NT02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Brown BH, Barber DC, Wang W, et al. Multi-frequency imaging and modelling of respiratory related electrical impedance changes. Physiol Meas. 1994;15(Suppl 2a):A1-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Wi H, Sohal H, McEwan AL, et al. Multi-frequency electrical impedance tomography system with automatic self-calibration for long-term monitoring. IEEE Trans Biomed Circuits Syst. 2014;8(1):119–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Aguiar Santos S, Robens A, Boehm A, et al. System description and first application of an FPGA-based simultaneous multi-frequency electrical impedance tomography. Sensors (Basel). 2016;16(8):1158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Yang Y, Jia J. A multi-frequency electrical impedance tomography system for real-time 2D and 3D imaging. Rev Sci Instrum. 2017;88(8): 085110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Han B, Xu Y, Dong F. Design of current source for multi-frequency simultaneous electrical impedance tomography. Rev Sci Instrum. 2017;88(9): 094709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Ngo C, Spagnesi S, Munoz C, et al. Assessing regional lung mechanics by combining electrical impedance tomography and forced oscillation technique. Biomed Tech (Berl). 2018;63(6):673–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Padilha Leitzke J, Zangl H. A review on electrical impedance tomography spectroscopy. Sensors (Basel). 2020;20(18):5160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Menden T, Orschulik J, Dambrun S, et al. Reconstruction algorithm for frequency-differential EIT using absolute values. Physiol Meas. 2019;40(3): 034008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Metherall P, Barber DC, Smallwood RH, Brown BH. Three-dimensional electrical impedance tomography. Nature. 1996;380(6574):509–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Blue RS, Isaacson D, Newell JC. Real-time three-dimensional electrical impedance imaging. Physiol Meas. 2000;21(1):15–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Grychtol B, Schramel JP, Braun F, et al. Thoracic EIT in 3D: experiences and recommendations. Physiol Meas. 2019;40(7): 074006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Gao Y, Zhang K, Li M, et al. Feasibility of 3D-EIT in identifying lung perfusion defect and V/Q mismatch in a patient with VA-ECMO. Crit Care. 2024;28(1):90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Wu Y, Chen B, Liu K, et al. Shape reconstruction with multiphase conductivity for electrical impedance tomography using improved convolutional neural network method. IEEE Sens J. 2021;21(7):9277–87. [Google Scholar]

- 123.Pessoa D, Rocha BM, Cheimariotis GA, et al. Classification of electrical impedance tomography data using machine learning. Annu Int Conf IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc. 2021;2021:349–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Wang Q, He H, Yuan S, et al. Early bedside detection of pulmonary perfusion defect by electrical impedance tomography after pulmonary endarterectomy. Pulm Circ. 2024;14(2): e12372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Stowe S, Boyle A, Sage M, et al. Comparison of bolus- and filtering-based EIT measures of lung perfusion in an animal model. Physiol Meas. 2019;40(5): 054002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Coppadoro A, Eronia N, Foti G, Bellani G. Event-triggered averaging of electrical impedance tomography (EIT) respiratory waveforms as compared to low-pass filtering for removal of cardiac related impedance changes. J Clin Monit Comput. 2020;34(3):553–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Deibele JM, Luepschen H, Leonhardt S. Dynamic separation of pulmonary and cardiac changes in electrical impedance tomography. Physiol Meas. 2008;29(6):S1-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Oppenheim AV, Schafer RW, (Eds). Discrete-Time Signal Pro-cessing. 1989.

- 129.Heinrich S, Schiffmann H, Frerichs A, et al. Body and head position effects on regional lung ventilation in infants: an electrical impedance tomography study. Intensive Care Med. 2006;32(9):1392–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Chuong N, Sarah S, Carlos M, et al. Assessing regional lung mechanics by combining electrical impedance tomography and forced oscillation technique. Biomed Eng/Biomedizinische Technik. 2018;63(6):673–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Dunlop S, Hough J, Riedel T, et al. Electrical impedance tomography in extremely prematurely born infants and during high frequency oscillatory ventilation analyzed in the frequency domain. Physiol Meas. 2006;27(11):1151–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Grant CA, Pham T, Hough J, et al. Measurement of ventilation and cardiac related impedance changes with electrical impedance tomography. Crit Care. 2011;15(1):R37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Gaertner VD, Waldmann AD, Davis PG, et al. Transmission of oscillatory volumes into the preterm lung during noninvasive high-frequency ventilation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2021;203(8):998–1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Frerichs I, Achtzehn U, Pechmann A, et al. High-frequency oscillatory ventilation in patients with acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Crit Care. 2012;27(2):172–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Cheng KS, Su PL, Ko YF. Separation of heart and lung-related signals in electrical impedance tomography using empirical mode decomposition. Curr Med Imaging. 2022;18(13):1396–415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Hulkenberg AC, Ngo C, Lau R, Leonhardt S. Separation of ventilation and perfusion of electrical impedance tomography image streams using multi-dimensional ensemble empirical mode decomposition. Physiol Meas. 2024;45(7):075008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Yang L, Qu S, Zhang Y, et al. Removing clinical motion artifacts during ventilation monitoring with electrical impedance tomography: introduction of methodology and validation with simulation and patient data. Front Med (Lausanne). 2022;9: 817590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.