This secondary analysis of a cluster randomized trial assesses 3-year outcomes of the Massachusetts office-based addiction treatment (OBAT) model of nurse care management for opioid use disorder.

Key Points

Question

How does nurse care management of office-based addiction treatment (OBAT) for opioid use disorder (OUD) affect OUD medication treatment 3 years after implementation?

Findings

This secondary analysis of a cluster randomized implementation trial of 290 071 primary care patients from 6 health systems found that after 3 years, intervention clinics provided 19.7 more patient-years of OUD treatment per 10 000 patients than usual care clinics.

Meaning

In 3 years since the start of OBAT implementation, the increase in OUD treatment in intervention compared with usual care clinics was greater than during the first 2 years of implementation, suggesting that integration of a new model of OUD treatment into primary care takes time to overcome barriers.

Abstract

Importance

The Primary Care Opioid Use Disorders (PROUD) treatment trial was a 2-year implementation trial that demonstrated the Massachusetts office-based addiction treatment (OBAT) model of nurse care management for opioid use disorder (OUD) increased OUD treatment in the 2 years after implementation began (8.2 more patient-years of OUD treatment per 10 000 primary care patients). The intervention was continued for a third year, permitting evaluation of 3-year outcomes.

Objective

To compare OUD medication treatment in intervention and usual care clinics over 3 years of implementation.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This is a preplanned secondary analysis of a cluster randomized implementation trial, conducted in 6 health systems in 5 states (2 primary care clinics per health system) with clinic randomization stratified by system (assignment notification February 28, 2018 [August 31, 2018, in 1 system]). Data were obtained from electronic health records and insurance claims. Eligible patients were those aged 16 to 90 years visiting intervention or usual care clinics from 3 years before to 2 years after randomization. Patients new to clinics during the third year after randomization could not be included because COVID-19–era transitions to virtual care precluded assignment of patients to clinics. Data analysis occurred from November 2023 to September 2024.

Intervention

Clinics were randomized to intervention or care as usual. Intervention included 3 implementation components: salary for 1 full-time OBAT nurse per intervention clinic; training and ongoing technical assistance for nurses; and 3 or more primary care buprenorphine prescribers.

Main Outcome and Measures

Patient-years of OUD treatment (buprenorphine or extended-release naltrexone) per 10 000 primary care patients in the 3 years postrandomization. Mixed-effect models adjusted for baseline values of the outcome and included a health system–specific random intercept to account for correlation of clinic pairs within a system.

Results

Prerandomization, a total of 290 071 primary care patients were seen, including 130 618 in intervention clinics (mean [SD] age, 48.6 [17.7] years; mean [SD] female, 59.3% [4.0%]) and 159 453 in usual care clinics (mean [SD] age, 47.2 [17.5] years; mean [SD] female, 64.0% [5.3%]). Over 3 years postrandomization, intervention clinics provided 19.7 (95% CI, 11.1-28.4) more patient-years of OUD treatment per 10 000 primary care patients compared with usual care clinics.

Conclusions

In this secondary analysis of the PROUD cluster randomized trial, after an added year of the intervention, OUD treatment continued to increase in intervention clinics compared with usual care. The treatment increase over 3 years exceeded that of the first 2 years, suggesting that implementation of the Massachusetts OBAT model leads to ongoing increases in OUD treatment among primary care patients in the third year of implementation.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03407638

Introduction

Deaths from opioid use continue to increase.1,2 Untreated opioid use disorder (OUD) causes substantial mortality and morbidity worldwide, and medication treatment of OUD is an essential care component that saves lives.3,4 However, most people with OUD do not receive medication treatment.3,4,5,6,7 Multiple models to increase OUD treatment in primary care have been proposed, with no demonstrated increase in OUD medication treatment until recently.8,9,10

The Primary Care OUD (PROUD) treatment trial was a cluster randomized implementation trial of the Massachusetts model of office-based addiction treatment (OBAT) across 6 diverse health systems, conducted by the National Institute on Drug Abuse Clinical Trials Network (CTN).8,11,12,13,14 OBAT integrates full-time nurse care managers into primary care for a team-based approach to providing OUD medication treatment (with buprenorphine or extended-release injectable naltrexone [XR-NTX]).11,15 The PROUD trial tested whether implementation of this model would increase OUD treatment among primary care patients, compared with usual care, in the 2 years after implementation start. The primary implementation strategy of this nurse-led model is to fund a full-time nurse to support OUD care. Additional PROUD trial implementation strategies included training and ongoing technical assistance for the nurses from external nurse experts and requiring 3 primary care clinicians to prescribe medications for OUD.

The PROUD trial demonstrated that the Massachusetts OBAT model meaningfully increased OUD treatment in primary care, with clinics randomized to the PROUD intervention increasing OUD treatment by 8.2 patient-years per 10 000 primary care patients, compared with usual care in the 2 years after randomization.16 The trial also demonstrated important variation across health systems, with significant increases in OUD treatment in 2 of 6 health systems.16 However, hiring and onboarding nurses takes time, and in PROUD, nurses did not start seeing patients until 4 to 15 months after randomization, contributing to low numbers of patients treated in the first year postrandomization.11,16 Implementation barriers included clinician and staff ambivalence toward treating patients with OUD, uneven support for the nurse role, and limited knowledge about or comfort in diagnosing OUD. A potential benefit of the Massachusetts OBAT model, once implemented, is a shift in clinic culture toward a more accepting approach to OUD care that encourages patient trust, destigmatizes treatment, and supports treatment retention.17 Thus, benefits of the model could increase over time.

To evaluate benefits of the model over 3 years of implementation, a decision was made early in year 2 of the trial to fund an additional year of the intervention to evaluate implementation outcomes over 3 years. In this preplanned secondary analysis, we describe the results of the PROUD primary outcome—patient-years of OUD treatment per 10 000 primary care patients—as well as secondary outcomes over 3 years postrandomization.

Methods

This preplanned secondary analysis of the PROUD trial was approved by the Advarra institutional review board. The trial protocol and statistical analysis plan are in Supplement 1. A data and safety monitoring board oversaw the trial, and we followed the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials Extension (CONSORT Extension) reporting guideline.18

Setting

PROUD was conducted in 6 health systems in New York, Florida, Michigan, Texas, and Washington.19 Each system included 2 primary care clinics or groups of smaller, geographically proximal clinics; the 12 clinics were randomized (1:1) to either intervention or usual care, stratified by health system (eFigure 1 in Supplement 2).16 Randomization occurred on February 28, 2018, for 5 health systems (and on August 29, 2018, for 1 system), with intervention clinics able to begin implementation at that time. Although the intervention was planned for 2 years, due to slow start-up, the CTN funded a third year. This secondary analysis evaluates the PROUD intervention over 3 intervention years.

Data Collection and Participants

As a pragmatic trial, health systems implemented the PROUD intervention for all their patients, with the study relying on existing data to identify the sample and measure outcomes. Patients were included in the trial if they were aged 16 to 90 years and visited a participating clinic anytime in the 3 years before the health system’s randomization date until 2 years after randomization (1.5 years in 1 site) (eFigure 2 in Supplement 2). Thus, PROUD was an open cohort trial, with new patients added to the cohort postrandomization and assigned to clinics based on the clinic or clinics they visited. The trial did not recruit patients; therefore, consent was not required. PROUD received waivers of informed consent and Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act authorization from the Advarra institutional review board.

Of note, year 3 of PROUD coincided with the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic (March 2020 to February 2021), and the shift to virtual care precluded assignment of new patients to specific clinics. As a result, no new patients were added to the study cohort year 3. Thus, the sample for this 3-year evaluation was the same as the main trial. Patients who had outcomes measured in the third year postrandomization had a visit to a trial clinic in year 3 and at least 1 visit in the prior 5 years (ie, during 3 baseline years or 2 postrandomization years).

Data were extracted from electronic health records (EHRs), including claims, from each health system and securely transferred to Kaiser Permanente Washington. Data included patient demographics, diagnoses, procedure codes, outpatient prescription medication orders and health care utilization. The baseline period for outcome measurement was 2 years prerandomization, while the follow-up period for outcome measurement was 3 years postrandomization (2.5 years in 1 system) (eFigure 3 in Supplement 2).

Implementation Intervention

Design of the PROUD implementation trial was guided by the Practical, Robust Implementation and Sustainability Model (PRISM) framework,19,20 with selection of outcomes guided by the Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation Fidelity, and Maintenance framework embedded within PRISM.21,22 The PROUD intervention19 included 3 implementation strategies to support implementation of OBAT in intervention clinics: funding for a full-time nurse in each clinic, training and technical assistance for nurses from OBAT nurse educators at Boston Medical Center,23 and an agreement that 3 or more primary care clinicians would prescribe buprenorphine, obtaining training and waivers if necessary, for clinics randomized to the intervention. All 3 components were continued for the third year. Clinics randomized to usual care did not receive support from the study but were allowed to improve OUD care if desired, although they were asked not to use Boston Medical Center OBAT Manual during the main trial.23

Measures

Baseline descriptive measures include numbers of primary care patients, clinicians, and buprenorphine prescribers, patient sociodemographics, and clinical characteristics. The primary outcome of patient-years of OUD treatment per 10 000 patients was also described at baseline.

Primary Outcome

The primary implementation outcome was a clinic-level measure of the number of patient-years of OUD medication treatment with buprenorphine or XR-NTX per 10 000 patients seen during follow-up.16 Medication treatment was defined as having a medication order or procedure code for buprenorphine formulations indicated for OUD (buccal, sublingual, implant, or subcutaneous injection) or for XR-NTX with OUD diagnosis. Days of medication treatment were measured based on orders and procedures documented in the EHR and divided by 365 days for patient-years of treatment. To account for varying clinic sizes, we divided the outcome by the number of patients seen in the clinic during follow-up and multiplied by 10 000 to calculate the number of patient-years of OUD treatment per 10 000 patients seen.

Secondary Outcomes

Secondary outcomes were reported at the clinic level per 10 000 patients seen. We calculated the primary outcome for 2 mutually exclusive patient groups based on timing of initiation of OUD treatment: patients who newly initiated treatment (defined as OUD treatment for those with no treatment in the prior 365 days) and patients who had ongoing treatment (defined as OUD treatment for patients with less than a 365-day gap in treatment).

Additionally, we calculated the primary outcome restricted to the time period in which the nurse was seeing patients for each health care system (eFigure 3 in Supplement 2) and included a measure for newly initiated treatment during the time when the nurse was seeing patients in each health system (ie, restricted to the time period when the nurse began treating their first patient and ended treating their last patient at the intervention clinic for each health system, which applied to both the intervention and usual care clinics [802 days for health system 1, 690 days for health system 2, 826 days for health system 3, 616 days for health system 4, 717 days for health system 5, and 941 days for health systems 6]). We evaluated a common OUD treatment quality metric (the proportion of patients with an OUD diagnosis that received OUD medication treatment)24,25,26 to allow comparison with other research.27 Lastly, we measured number of patients per 10 000 patients seen in a clinic per month who received OUD medication treatment each month from baseline through follow-up, as well as the cumulative number treated per 10 000 patients each month after randomization.

Statistical Analyses

Baseline characteristics of patients in the 2 years prior to randomization, as well as staffing and size of clinics, were summarized for intervention and usual care clinics. Unadjusted numbers of patients treated for OUD each month (per 10 000 patients seen per month) in intervention and usual care clinics were summarized over the study period, with cumulative numbers summarized postrandomization.16

Primary analyses—intent-to-treat analyses with the 12 clinics as the unit of analysis—compared mean patient-years of treatment in intervention and usual care clinics using a mixed-effect model to account for correlation of outcomes between pairs of clinics in the same system, adjusted for baseline values of the outcome, as for the primary trial results (Supplement 1).16 The main outcome was also evaluated by health system due to site-level variation 2 years postrandomization.16 All tests were 2-sided and conducted at the significance level of less than .05.

Secondary outcomes were analyzed overall and by health system. We estimated the difference in postrandomization and prerandomization patient-years of OUD treatment per 10 000 patients between intervention and usual care clinics for each health system, and obtained 2-sided, 95% CIs by using the bootstrap t method28 to resample patient-level data (Supplement 1). In addition, we summarized the primary outcome (mean and SD for patient-years of OUD treatment) by trial group for each of 2 years prerandomization and 3 years postrandomization, without adjustment, and estimated the proportion of patients who newly initiated OUD treatment prerandomization and postrandomization. We summarized the prevalence of OUD treatment for patients who received an OUD diagnosis in patient-level analyses by trial group. A post hoc analysis evaluated sensitivity of the results to statistical modeling assumptions with a permutation test (Supplement 1).29 Analyses were conducted in R version 4.3.1 (R Project for Statistical Computing) from November 2023 to September 2024.30

Results

A total of 290 071 primary care patients were included at baseline, of whom 130 618 were seen in PROUD intervention clinics and 159 453 were seen in usual care clinics(Table 1). During the baseline period, intervention and usual care clinics saw a mean (SD) 18 530 (4074) and 22 664 (8265) patients, respectively. Patient characteristics varied between intervention (mean [SD] age, 48.6 [17.7] years; mean [SD] female, 59.3% [4.0%]) and usual care clinics (mean [SD] age, 47.2 [17.5]; mean [SD] female, 64.0% [5.3%]), with usual care clinics providing more OUD treatment at baseline compared with intervention clinics (mean [SD], 10.6 [7.4] vs 6.8 [5.5] patient-years of OUD treatment per 10 000 patients). Cumulative unadjusted numbers of patients treated for OUD in intervention clinics exceeded those in usual care clinics by 13 months and continued to increase through 3 years postrandomization (eFigure 4 in Supplement 2). Results of cumulative unadjusted numbers of patients treated varied by health system (eFigure 5 in Supplement 2).

Table 1. Characteristics of Clinics’ Patient Populations in the Baseline Period (2 Years Prior to Randomization).

| Characteristic | Clinic mean (SD), prerandomization | |

|---|---|---|

| PROUD intervention | Usual care | |

| Primary care patients in each trial group, No.a | 130 618 | 159 453 |

| Staffing and size of clinics in baseline period | ||

| No. of clinicians who prescribe in clinicb | 31.7 (20.0) | 36.8 (18.8) |

| No. of primary care buprenorphine prescribers in clinicc | 1.5 (1.0) | 1.5 (2.0) |

| No. of patients seen in clinicd | 18 530 (4074) | 22 664 (8265) |

| Proportion of clinics’ patient population, % | ||

| Age, ye | ||

| 16-17 | 2.2 (1.7) | 1.9 (1.4) |

| 18-24 | 8.5 (2.2) | 10.2 (3.0) |

| 25–44 | 30.1 (4.9) | 34.3 (7.2) |

| 45–64 | 39.0 (4.3) | 36.7 (6.9) |

| 65-74 | 12.6 (3.1) | 10.4 (3.0) |

| ≥75 | 7.6 (2.9) | 6.4 (3.2) |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 59.3 (4.0) | 64.0 (5.3) |

| Male | 40.7 (4.0) | 36.0 (5.3) |

| Race and ethnicity | ||

| Hispanic ethnicity | 26.4 (25.6) | 33.4 (29.9) |

| Non-Hispanic ethnicity | ||

| Asian | 5.2 (3.8) | 5.0 (5.0) |

| Black or African American | 18.4 (14.4) | 18.9 (13.4) |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 0.5 (0.6) | 0.5 (0.6) |

| Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander | 0.4 (0.5) | 0.8 (1.1) |

| White | 40.9 (33.3) | 31.1 (24.7) |

| Multiple race | 0.4 (0.5) | 0.8 (1.3) |

| Other racef | 2.4 (2.4) | 2.9 (2.7) |

| Missing race and ethnicity data | 5.4 (2.8) | 6.7 (2.6) |

| Insurance status closest to randomization | ||

| Medicare | 21.1 (7.0) | 18.3 (8.6) |

| Medicaid | 27.7 (31.7) | 35.7 (33.3) |

| Otherwise insured (eg, commercial or private) | 57.7 (25.2) | 53.1 (27.7) |

| Uninsured | 5.3 (5.9) | 4.5 (5.4) |

| Unknown | 1.0 (1.4) | 1.0 (1.2) |

| Patients’ neighborhoodg | ||

| Median household income, $ | 61 270.0 (24 151.8) | 54 467.7 (16 779.0) |

| Unemployed | 6.1 (2.9) | 7.2 (2.3) |

| Below federal poverty level | 16.0 (11.2) | 18.2 (9.7) |

| Any mental health diagnoses | 23.3 (5.0) | 22.8 (6.7) |

| Depression | 13.8 (3.8) | 13.4 (5.6) |

| Anxiety | 15.4 (3.4) | 15.2 (3.6) |

| Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder | 1.2 (0.9) | 1.1 (0.7) |

| Posttraumatic stress disorder | 1.0 (0.6) | 1.1 (0.7) |

| Schizophrenia or psychoses | 0.8 (0.5) | 0.8 (0.4) |

| Other mental health conditions | 1.8 (0.5) | 1.8 (0.9) |

| Any substance use disorder diagnoses | ||

| Opioid | 0.7 (0.5) | 0.8 (0.5) |

| Tobacco | 7.4 (4.1) | 8.2 (4.4) |

| Alcohol | 2.0 (1.0) | 1.8 (0.8) |

| Cannabis | 0.8 (0.7) | 0.7 (0.4) |

| Stimulant | 0.4 (0.3) | 0.4 (0.3) |

| Other | 0.6 (0.3) | 0.5 (0.3) |

| Baseline value of PROUD trial outcome: patient-years of OUD treatment per 10 000 primary care patients | 6.8 (5.5) | 10.6 (7.4) |

Abbreviations: OUD, opioid use disorder; PROUD, Primary Care OUD Treatment trial.

All patients assigned to the PROUD intervention or usual care clinics, based on an eligible primary care visit in the 3 years prerandomization.

Number and type (eg, physician, physician assistant, advanced registered nurse practitioner, or Doctor of Osteopathic Medicine) determined from encounter data in the electronic health record during the 2 years prerandomization; clinicians assigned to clinics based on number of visits in clinic prerandomization.

Primary care clinicians who can prescribe buprenorphine determined from electronic health record medication orders and procedures.

Number of patients seen in each clinic during the 2 years prerandomization.

At eligible visit closest to and prior to randomization date.

Other race was recorded in the electronic health record when a person did not identify as belonging to any of the previously listed racial groups and was not Hispanic.

Using zip code of residence at time closest to randomization date.

OUD Treatment Postrandomization

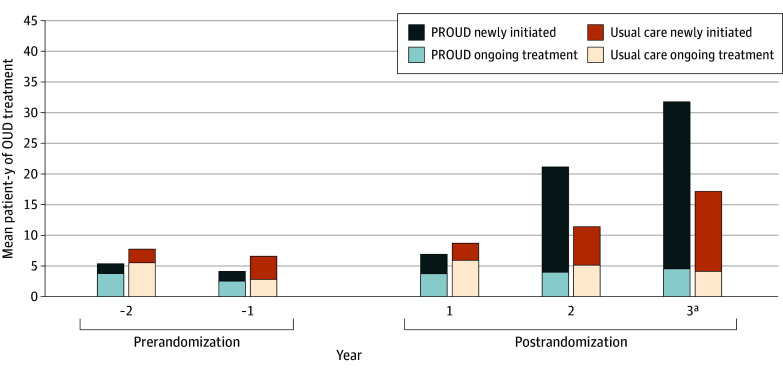

Compared with usual care clinics, intervention clinics provided 19.7 (95% CI, 11.1 to 28.4) more patient-years of OUD treatment per 10 000 primary care patients in the 3 years postrandomization after adjustment for baseline (Table 2). These results were confirmed post hoc using a permutation test (P = .03). For patients who newly initiated treatment postrandomization, the mean difference in the outcome between intervention and usual care clinics was 19.2 (95% CI, 8.4 to 30.0) patient-years of OUD treatment per 10 000 primary care patients, whereas for patients with ongoing treatment, the mean difference was 0.1 (95% CI, −4.6 to 4.8) patient-years of OUD treatment per 10 000 primary care patients. For secondary outcomes, the mean difference was 21.9 (95% CI, 9.9 to 33.9) patient-years of OUD treatment per 10 000 primary care patients when restricted to when the nurse was seeing patients and 21.4 (95% CI, 4.7 to 38.0) patient-years of OUD treatment per 10 000 primary care patients for those who newly initiated treatment when the nurse was seeing patients. When patient-years of OUD treatment was described for each study year, intervention clinics demonstrated increases in OUD treatment years 2 and 3, with the greatest increase in year 3, largely among patients who newly initiated treatment postrandomization (Figure).

Table 2. Clinic-Level Implementation Outcomes of the PROUD Trial Assessed in the 3 Years Postrandomizationa.

| Outcome | Clinic mean (SD) postrandomization | Mean difference (95% CI)c | |

|---|---|---|---|

| PROUD intervention (n = 171 510)b | Usual care (n = 205 833)b | ||

| Primary outcome: patient-years of OUD treatmentd,e | 30.6 (23.1) | 22.8 (18.8) | 19.7 (11.1 to 28.4) |

| Secondary outcomes of patient-years of OUD treatment | |||

| Timing of treatment initiation | |||

| Ongoing treatment | 7.2 (7.1) | 10.7 (6.5) | 0.1 (−4.6 to 4.8) |

| Newly initiated treatment | 23.4 (16.2) | 12.1 (14.2) | 19.2 (8.4 to 30.0) |

| Restricted to when nurse was seeing patients | 30.3 (26.0) | 20.2 (18.1) | 21.9 (9.9 to 33.9) |

| Newly initiated treatment postrandomization and when nurse was seeing patientsd | 24.0 (19.2) | 12.1 (14.9) | 21.4 (4.7 to 38.0) |

Abbreviations: OUD, opioid use disorder; PROUD, Primary Care OUD Treatment trial.

Results presented per 10 000 primary care patients by dividing by the number of patients seen in the clinic postrandomization and multiplied by 10 000.

Patients in each trial group were eligible 3 years prior to randomization and up to 2 years postrandomization.

Random-effects model adjusted for the outcome measure at baseline (2 years prior to randomization).

Treatment defined as having a medication order or procedure code for buprenorphine formulations that are indicated for OUD or having a medication order or procedure code for extended-release injectable naltrexone.

The intraclass correlation within cluster is 0.72.

Figure. Mean Patient-Years of Opioid Use Disorder (OUD) Treatment per 10 000 Patients per Clinic by Year, Prerandomization and Postrandomization.

Newly initiated was defined as OUD treatment for those with no OUD treatment in the prior 365 days, and ongoing treatment was defined as OUD treatment for patients with less than a 365-day gap in OUD treatment, separately for patients in the prerandomization and postrandomization periods, unadjusted for baseline. PROUD indicates Primary Care OUD Treatment trial.

aNo new primary care patients could be added in year 3; increases in treatment in year 3 are based on patients assigned to a primary care clinic from baseline through year 2.

Among patients with a documented OUD diagnosis, the proportion that received treatment increased more in intervention than usual care clinics (65 of 644 patients at baseline [10.1%] and 281 of 962 at follow-up [29.2%; a 19.1–percentage point increase] for intervention clinics, compared with 118 of 734 at baseline [16.1%] and 188 of 935 at follow-up [20.1%; a 4.0–percentage point increase] for usual care clinics). Thus, there was a 15.1% absolute increase in proportion of patients with documented OUD who received treatment in intervention compared with usual care clinics.

Health System–Specific Outcomes

Outcomes varied across health systems (Table 3). For the primary outcome, the intervention yielded significant benefit in 3 health systems over the 3 years postrandomization. For the secondary outcome of treatment among patients who newly initiated treatment postrandomization, the intervention yielded significant benefit in 4 health systems, ranging between 9.4 (95% CI, 1.1-14.0) and 43.0 (95% CI, 28.0-55.8) patient-years of OUD treatment per 10 000 patients. Out of concern that health system 1, with a primary outcome mean difference of 45.6 patient-years of OUD treatment per 10 000 patients, may have influenced main results, a post hoc analysis excluded this health system. Although the adjusted mean difference of 15.9 (95% CI, 4.3-27.5) more patient-years of OUD treatment per 10 000 patients was lower than the main effect (19.7 patient-years of OUD treatment per 10 000 patients), results remained significant.

Table 3. Clinic-Level Implementation Outcomes of the PROUD Trial Assessed in the 3 Years Postrandomization by Health System and Clinica.

| Outcome | Outcome value by health system and clinic | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health system 1 | Health system 2 | Health system 3 | Health system 4 | Health system 5 | Health system 6 | |||||||

| PROUD | Usual care | PROUD | Usual care | PROUD | Usual care | PROUD | Usual care | PROUD | Usual care | PROUD | Usual care | |

| Patients, No.b | 30 708 | 52 486 | 20 336 | 41 296 | 21 265 | 21 339 | 30 138 | 20 881 | 29 572 | 27 789 | 39 491 | 42 042 |

| Primary outcome: patient-years of OUD treatment, No.c | ||||||||||||

| Prerandomization | 13.3 | 3.9 | 5.3 | 11.2 | 8.3 | 20.3 | 1.1 | 13.6 | 0.4 | 0 | 12.4 | 14.3 |

| Postrandomization | 68.1 | 13.1 | 22.1 | 17.7 | 33.7 | 56.3 | 6.5 | 23.5 | 9.8 | 0 | 43.4 | 26 |

| Difference (post vs pre)d | 54.8 | 9.2 | 16.7 | 6.5 | 25.5 | 36.0 | 5.5 | 9.8 | 9.5 | 0 | 31.0 | 11.7 |

| PROUD vs usual care difference (95% CI)e,f | 45.6 (31.8 to 58.5) | 10.2 (−1.4 to 20.3) | −10.5 (−28.4 to 9.0) | −4.4 (−12.4 to 4.4) | 9.5 (1.2 to 14.0) | 19.3 (8.5 to 30.7) | ||||||

| Secondary outcomes of patient-years of OUD treatment | ||||||||||||

| Ongoing treatmentg | ||||||||||||

| Prerandomization | 9.2 | 1.1 | 4.7 | 9.3 | 4.9 | 8.3 | 0.3 | 10.1 | 0 | 0 | 8.3 | 8.2 |

| Postrandomization | 18.0 | 7.5 | 4.1 | 11.9 | 11.3 | 17.1 | 0 | 17.4 | 0 | 0 | 9.7 | 10.4 |

| Difference (post vs pre)d | 8.9 | 6.3 | −0.6 | 2.6 | 6.4 | 8.9 | −0.3 | 7.3 | 0 | 0 | 1.5 | 2.2 |

| PROUD vs usual care difference (95% CI)e,h | 2.5 (−5.5 to 10.6) | −3.2 (−8.9 to 2.5) | −2.4 (−13.6 to 8.8) | −7.6 (−15.8 to 0.7) | NA | −0.7 (−8.5 to 7.1) | ||||||

| Newly initiatede,i | ||||||||||||

| Prerandomization | 4.2 | 2.8 | 0.6 | 2.0 | 3.4 | 12.0 | 0.7 | 3.5 | 0.4 | 0 | 4.1 | 6.0 |

| Postrandomization | 50.1 | 5.7 | 18.0 | 5.8 | 22.4 | 39.2 | 6.5 | 6.1 | 9.8 | 0 | 33.7 | 15.6 |

| Difference (post vs pre)d | 45.9 | 2.9 | 17.3 | 3.9 | 19.0 | 27.1 | 5.8 | 2.6 | 9.4 | 0 | 29.6 | 9.6 |

| PROUD vs usual care difference (95% CI)e,f | 43.0 (28 to 55.8) | 13.4 (1.5 to 21.8) | −8.1 (−25 to 8.8) | 3.2 (−2.4 to 9.3) | 9.4 (1.1 to 14.0) | 20.0 (9.8 to 29.6) | ||||||

| Restricted to when nurse was seeing patients | ||||||||||||

| Prerandomization | 13.3 | 3.9 | 5.3 | 11.2 | 8.3 | 20.3 | 1.1 | 13.6 | 0.4 | 0 | 12.4 | 14.3 |

| Postrandomization | 73.9 | 13.5 | 16.9 | 12.6 | 32.0 | 53.1 | 6.2 | 16.5 | 8.0 | 0.0 | 44.6 | 25.3 |

| Difference (post vs pre)d | 60.6 | 9.6 | 11.6 | 1.3 | 23.7 | 32.8 | 5.2 | 2.9 | 7.6 | 0.0 | 32.2 | 11.1 |

| PROUD vs usual care difference (95% CI)e,f | 51.0 (35.9 to 65.2) | 10.2 (0.7 to 18.8) | −9.1 (−26.6 to 11.3) | 2.3 (−5.3 to 9.1) | 7.6 (1.0 to 11.3) | 21.1 (9.5 to 32.8) | ||||||

| Newly initiated and restricted to when nurse was seeing patientsi | ||||||||||||

| Prerandomization | 4.2 | 2.8 | 0.6 | 2.0 | 3.4 | 12.0 | 0.7 | 3.5 | 0.4 | 0 | 4.1 | 6.0 |

| Postrandomization | 56.3 | 6.3 | 14.4 | 4.1 | 23.2 | 40.5 | 6.2 | 5.7 | 8.0 | 0 | 35.7 | 16.1 |

| Difference (post vs pre)d | 52.2 | 3.5 | 13.8 | 2.2 | 19.8 | 28.5 | 5.5 | 2.2 | 7.6 | 0.0 | 31.6 | 10.0 |

| PROUD vs usual care difference (95% CI)e,f | 48.7 (31.9 to 62.9) | 11.6 (1.4 to 18.7) | −8.7 (−25.4 to 8.3) | 3.3 (−2.8 to 9.8) | 7.6 (1.0 to 11.3) | 21.6 (10.9 to 31.8) | ||||||

Abbreviations: NA, not applicable; OUD, opioid use disorder; PROUD, Primary Care OUD Treatment trial.

Results presented per 10 000 primary care patients, which was calculated by dividing by the number of patients seen in the clinic postrandomization and multiplied by 10 000.

Number of eligible primary care patients assigned to the clinics in 3 years prior to randomization and up to 2 years postrandomization.

Treatment was defined as having a medication order or procedure code for buprenorphine formulations that are indicated for OUD or having a medication order or procedure code for extended-release injectable naltrexone.

Calculated by subtracting prerandomization from postrandomization patient-years of OUD treatment for each clinic.

Calculated by subtracting the usual care difference (in prerandomization and postrandomization patient-years of OUD treatment) from the intervention clinic difference for each health system.

95% CI is based on bootstrap t method, described in the statistical analysis plan in Supplement 1.

Ongoing treatment was defined as OUD treatment for patients with less than a 365-day gap in OUD treatment.

95% CI is based on a normal approximation rather than bootstrap t method due to rare outcome events.

Newly initiated was defined as OUD treatment for those with no OUD treatment in the past 365 days.

Discussion

This secondary analysis of the PROUD cluster randomized clinical trial evaluated the effect of implementation of the Massachusetts OBAT model over 3 years after implementation began in the PROUD trial. Whereas main trial results showed significant increases in OUD treatment (8.2 patient-years of OUD treatment per 10 000 patients more in intervention compared with usual care clinics at 2 years follow-up16), the current study demonstrated increased OUD treatment by 19.7 patient-years per 10 000 primary care patients over 3 years, an increase of 11.5 patient-years of treatment over the difference seen at 2 years. After 3 years of implementation, a statistically significant benefit of the intervention on the primary outcome was observed in 3 health systems, whereas only 2 health systems had significant benefit at 2 years. Moreover, analyses of secondary outcomes among newly initiated patients showed benefit of the intervention in 4 of the 6 health systems, suggesting that more than 2 years is needed to test the success of this model in some settings.

It is noteworthy that the impact of the PROUD intervention grew considerably in the third year of implementation despite the fact that more than 70% of the increase in OUD treatment in the first 2 years of implementation was among patients new to the primary care clinics.16 In year 3, new patients to primary care could not be included in the trial because virtual visits due to COVID-19 were not easily assigned to specific clinics; this suggests that had this study been able to capture patients new to clinics year 3, the benefit of the intervention might have been substantially larger. The importance of new patients to the effect of the PROUD intervention in contrast with usual care is demonstrated in eFigure 4 in Supplement 2; the cumulative number of patients treated in intervention clinics increased in parallel with usual care clinics, whereas the number of patients in active treatment decreased in intervention clinics in the third year postrandomization compared with usual care.

Implementation of OUD medication treatment has proven challenging.31,32,33 In year 3, the PROUD intervention continued to expand treatment to more primary care patients already in the clinics and appeared to increase treatment in health systems that had not increased OUD treatment after 2 years. Removal of barriers to OBAT could improve uptake; for example, recent elimination of waiver requirements to prescribe buprenorphine34 may serve to increase the number of clinicians willing to treat OUD. Moreover, interventions to help clinicians optimize buprenorphine initiation practices may improve initiation and retention.13,35,36

Limitations

This study has limitations. As noted, the third year postrandomization coincided with the COVID-19 pandemic, and although shifts to virtual care have not demonstrated an effect on OUD treatment,37 it is possible the shift increased effectiveness of the OBAT model, accounting for some observed findings. The shift made assigning patients’ virtual visits to a clinic infeasible. As a result, patients with visits for the first time in year 3 could not be reliably assigned to clinics and were excluded. Given that many patients who benefit from OBAT are new to the OBAT clinic,11,16 exclusion of new patients likely attenuated both intervention and usual care OUD treatment outcomes compared with results if we could have captured new patients in year 3. In addition, while COVID-19–era shifts in OUD treatment policies at local, state, and federal levels may have sustained or expanded treatment access,38,39,40 such policies varied by location, were not consistently adopted,41 and could not be accounted for here. However, such policy shifts would be expected to have a similar effect on both trial groups in each system. The study included a small number of clusters with heterogeneous effects, which can be sensitive to a modeling approach, although post hoc permutation analyses and analyses that removed 1 health system with the largest effect confirmed findings.16 While the main trial included qualitative implementation findings,16 and additional analyses are ongoing, it was beyond this study’s scope to assess changes in qualitative findings during year 3. Therefore, this study could not identify the implementation factors that contributed to observed increases in treatment in intervention clinics year 3. This study relied on EHR medication orders available from all health systems, rather than dispensed medications, and thus does not include OUD treatment with methadone and other OUD treatment not captured in orders. Health systems and clinics had to agree to participate, potentially limiting generalizability. The patient-level metric for percentage of patients with an OUD diagnosis who received medication treatment may be biased because the intervention could attract or provide diagnoses for patients with OUD who differed from those with OUD in usual care, differentially increasing patients who both received an OUD diagnosis and were treated for OUD in the intervention group.42

Conclusions

In this secondary analysis of the PROUD cluster randomized trial, intervention clinics demonstrated meaningful increases in OUD treatment over 3 years, more than double the increases through the first 2 years of implementation. Three years after implementation began, 4 of 6 health systems had significant increases in primary or secondary outcomes, compared with 2 health systems after the first 2 years of implementation. Results suggest integration of a new model of OUD treatment into primary care takes time to overcome barriers and that implementation of the Massachusetts OBAT model leads to ongoing increases in OUD treatment among primary care patients in the third year of implementation.

Trial Protocol and Statistical Analysis Plan

eFigure 1. PROUD Study Flow Diagram

eFigure 2. PROUD Study Timeline and Sample, With an Additional Year for the Nurse Care Manager and Outcome Measurement

eFigure 3. Calendar Dates of When the Nurse Was Hired and When the Nurse Was Seeing Patients in Each Health System After Randomization

eFigure 4. Number of Patients Treated for OUD in Intervention and Usual Care Clinics per 10,000 Primary Care Patients per Month: Cumulative Numbers of Patients Treated for OUD Since Randomization, and Numbers in Active OUD Treatment Each Month From Baseline Through Follow-Up (Unadjusted)

eFigure 5. Cumulative Numbers of Patients Treated for OUD per 10,000 Patients Seen by Trial Arm for Each Health System During 3 Years of Follow-Up in Intervention and Usual Care Clinics, Unadjusted for Baseline

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Mattson CL, Tanz LJ, Quinn K, Kariisa M, Patel P, Davis NL. Trends and geographic patterns in drug and synthetic opioid overdose deaths - United States, 2013-2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(6):202-207. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7006a4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Center for Health Statistics. Drug overdose deaths in the US top 100,000 annually. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated November 17, 2021. Accessed October 17, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/pressroom/nchs_press_releases/2021/20211117.htm

- 3.Mancher M, Leshner AI, eds. Medications for Opioid Use Disorder Saves Lives. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Published March 30, 2019. Accessed October 17, 2024. https://nap.nationalacademies.org/catalog/25310/medications-for-opioid-use-disorder-save-lives [PubMed]

- 4.Leshner AI, Dzau VJ. Medication-based treatment to address opioid use disorder. JAMA. 2019;321(21):2071-2072. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.5523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wu LT, Zhu H, Swartz MS. Treatment utilization among persons with opioid use disorder in the United States. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016;169:117-127. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.10.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boudreau DM, Lapham G, Johnson EA, et al. Documented opioid use disorder and its treatment in primary care patients across six U.S. health systems. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2020;112S:41-48. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2020.02.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gordon AJ, Lo-Ciganic WH, Cochran G, et al. Patterns and quality of buprenorphine opioid agonist treatment in a large Medicaid program. J Addict Med. 2015;9(6):470-477. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Korthuis PT, McCarty D, Weimer M, et al. Primary care-based models for the treatment of opioid use disorder: a scoping review. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166(4):268-278. doi: 10.7326/M16-2149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lagisetty P, Klasa K, Bush C, Heisler M, Chopra V, Bohnert A. Primary care models for treating opioid use disorders: what actually works? A systematic review. PLoS One. 2017;12(10):e0186315. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0186315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Donroe JH, Bhatraju EP, Tsui JI, Edelman EJ. Identification and management of opioid use disorder in primary care: an update. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2020;22(5):23. doi: 10.1007/s11920-020-01149-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.LaBelle CT, Han SC, Bergeron A, Samet JH. Office-based opioid treatment with buprenorphine (OBOT-B): statewide implementation of the Massachusetts collaborative care model in community health centers. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2016;60:6-13. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2015.06.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.World Health Organization . Guidelines for the psychosocially assisted pharmacological treatment of opioid dependence. Published 2009. Accessed June 11, 2018. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK143185/ [PubMed]

- 13.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration . Medications for opioid use disorder for healthcare and addiction professionals, policymakers, patients, and families: treatment improvement protocol. 63. 2021. Accessed October 17, 2024. https://store.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/pep21-02-01-002.pdf

- 14.American Society of Addiction Medicine . Public policy statement on the regulation of office-based opioid treatment. January 17, 2018. Accessed October 17, 2024. https://www.asam.org/docs/default-source/public-policy-statements/statement-on-regulation-of-obot.pdf

- 15.Alford DP, LaBelle CT, Kretsch N, et al. Collaborative care of opioid-addicted patients in primary care using buprenorphine: five-year experience. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(5):425-431. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wartko PD, Bobb JF, Boudreau DM, et al. ; PROUD Trial Collaborators . Nurse care management for opioid use disorder treatment: the PROUD cluster randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2023;183(12):1343-1354. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2023.5701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beharie N, Kaplan-Dobbs M, Urmanche A, Paone D, Harocopos A. “I didn’t feel like a number”: the impact of nurse care managers on the provision of buprenorphine treatment in primary care settings. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2022;132:108633. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2021.108633 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Campbell MK, Piaggio G, Elbourne DR, Altman DG; CONSORT Group . Consort 2010 statement: extension to cluster randomised trials. BMJ. 2012;345:e5661. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e5661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Campbell CI, Saxon AJ, Boudreau DM, et al. Primary care opioid use disorders treatment (PROUD) trial protocol: a pragmatic, cluster-randomized implementation trial in primary care for opioid use disorder treatment. Addict Sci Clin Pract. 2021;16(1):9. doi: 10.1186/s13722-021-00218-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Feldstein AC, Glasgow RE. A practical, robust implementation and sustainability model (PRISM) for integrating research findings into practice. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2008;34(4):228-243. doi: 10.1016/S1553-7250(08)34030-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Glasgow RE, Vogt TM, Boles SM. Evaluating the public health impact of health promotion interventions: the RE-AIM framework. Am J Public Health. 1999;89(9):1322-1327. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.89.9.1322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gaglio B, Shoup JA, Glasgow RE. The RE-AIM framework: a systematic review of use over time. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(6):e38-e46. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boston Medical Center . Office based addiction treatment training and technical assistance—Massachusetts nurse care manager model of office-based addiction treatment: clinical guidelines. Updated April 2021. Accessed October 17, 2024. https://www.addictiontraining.org/documents/resources/22_2021_Clinical_Guidelines_1.12.2022_fp_th%2528003%2529.29.pdf

- 24.National Quality Forum . Opioids and opioid use disorder: quality measurement priorities. Published February 2020. Accessed October 17, 2024. https://www.qualityforum.org/Publications/2020/02/Opioids_and_Opioid_Use_Disorder__Quality_Measurement_Priorities.aspx

- 25.Mark TL, McGaffey F, Koppelman J, Yastishock V. State Measures for improving opioid use disorder treatment implementation toolkit. RTI International. Published 2022. Accessed October 17, 2024. https://www.pewtrusts.org/-/media/assets/2022/11/14798_pew_metrics_toolkit_111722.pdf

- 26.National Quality Forum . Continuity of pharmacotherapy for opioid use disorder (OUD). Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. 2019. Accessed October 17, 2024. https://qpp.cms.gov/docs/QPP_quality_measure_specifications/CQM-Measures/2019_Measure_468_MIPSCQM.pdf

- 27.Mauro PM, Gutkind S, Annunziato EM, Samples H. Use of medication for opioid use disorder among Us adolescents and adults with need for opioid treatment, 2019. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(3):e223821-e223821. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.3821 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Efron B, Tibshirani RJ. An introduction to the bootstrap. CRC press; 1994. doi: 10.1201/9780429246593 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rabideau DJ, Wang R. Randomization-based confidence intervals for cluster randomized trials. Biostatistics. 2021;22(4):913-927. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/kxaa007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.R Core Team . The R project for statistical computing. Accessed October 17, 2024. https://www.R-project.org/

- 31.Gustavson AM, Kenny ME, Wisdom JP, et al. Fluctuations in barriers to medication treatment for opioid use disorder prescribing over the course of a one-year external facilitation intervention. Addict Sci Clin Pract. 2021;16(1):51. doi: 10.1186/s13722-021-00259-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gustavson AM, Wisdom JP, Kenny ME, et al. Early impacts of a multi-faceted implementation strategy to increase use of medication treatments for opioid use disorder in the Veterans Health Administration. Implement Sci Commun. 2021;2(1):20. doi: 10.1186/s43058-021-00119-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lott AM, Danner AN, Malte CA, et al. Clinician perspectives on delivering medication treatment for opioid use disorder during the COVID-19 pandemic: a qualitative evaluation. J Addict Med. 2023;17(4):e262-e268. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000001156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gupta R, Wright NF, Holtgrave DRA. A 2023 agenda for substance use prevention and treatment in the US. JAMA. 2023;329(9):707-708. doi: 10.1001/jama.2023.1090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tilhou AS, Murray E, Wang J, et al. Trends in buprenorphine dosage and days supplied for new treatment episodes for opioid use disorder, 2010-2019. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2023;252:110981. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2023.110981 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mattick RP, Kimber J, Breen C, Davoli M. Buprenorphine maintenance versus placebo or methadone maintenance for opioid dependence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;(3):CD002207. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002207.pub2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hailu R, Mehrotra A, Huskamp HA, Busch AB, Barnett ML. Telemedicine use and quality of opioid use disorder treatment in the US during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(1):e2252381. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.52381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hughes PM, Verrastro G, Fusco CW, Wilson CG, Ostrach B. An examination of telehealth policy impacts on initial rural opioid use disorder treatment patterns during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Rural Health. 2021;37(3):467-472. doi: 10.1111/jrh.12570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Livingston NA, Ameral V, Banducci AN, Weisberg RB. Unprecedented need and recommendations for harnessing data to guide future policy and practice for opioid use disorder treatment following COVID-19. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2021;122:108222. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2020.108222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Andraka-Christou B, Bouskill K, Haffajee RL, et al. Common themes in early state policy responses to substance use disorder treatment during COVID-19. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2021;47(4):486-496. doi: 10.1080/00952990.2021.1903023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pessar SC, Boustead A, Ge Y, Smart R, Pacula RL. Assessment of state and federal health policies for opioid use disorder treatment during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond. JAMA Health Forum. 2021;2(11):e213833. doi: 10.1001/jamahealthforum.2021.3833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bobb JF, Qiu H, Matthews AG, McCormack J, Bradley KA. Addressing identification bias in the design and analysis of cluster-randomized pragmatic trials: a case study. Trials. 2020;21(1):289. doi: 10.1186/s13063-020-4148-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol and Statistical Analysis Plan

eFigure 1. PROUD Study Flow Diagram

eFigure 2. PROUD Study Timeline and Sample, With an Additional Year for the Nurse Care Manager and Outcome Measurement

eFigure 3. Calendar Dates of When the Nurse Was Hired and When the Nurse Was Seeing Patients in Each Health System After Randomization

eFigure 4. Number of Patients Treated for OUD in Intervention and Usual Care Clinics per 10,000 Primary Care Patients per Month: Cumulative Numbers of Patients Treated for OUD Since Randomization, and Numbers in Active OUD Treatment Each Month From Baseline Through Follow-Up (Unadjusted)

eFigure 5. Cumulative Numbers of Patients Treated for OUD per 10,000 Patients Seen by Trial Arm for Each Health System During 3 Years of Follow-Up in Intervention and Usual Care Clinics, Unadjusted for Baseline

Data Sharing Statement