Abstract

Background

Bio-based synthesis of metallic nanoparticles has garnered much attention in recent times owing to their non-toxic, environmentally friendly, and cost-effective nature.

Methods

In this study, gold nanoparticles (S4-GoNPs) were synthesized by a simple and environmentally friendly technique using an aqueous extract of jamun leaves (JLE) as an effective capping, stabilizer, and reducing agent. JLE was screened for the presence of phytochemicals followed by synthesis, characterization, and evaluation of their antibacterial, antidiabetic, antioxidant, and photocatalytic degradation potentials using standard established procedures.

Results

The phytochemical profile of JLE was found to be rich in flavonoids, tannins, terpenoid phenols, anthraquinones, and cardiac glycosides. Its GC-MS analysis revealed the presence of compounds majorly of them as the (1R)-2,6,6-Trimethylbicyclo[3.1.1]hept-2-ene (5.141%), 2(10)-pinene (4.119%), α-cyclopene (5.274%) α,α-muurolene (7.525%), naphthalene, 1,2,3,4,4a,5,6,8a-octahydro-7-methyl-4-methylene-1-(1-methylethyl)-(1.alpha.,4a.beta.,8a.alpha) (8.470%), delta-cadinene (23.246), α-guajene (3.451%), and gamma-muurolene (4.379%). The visual morphology and UV–Vis spectral surface plasmon resonance at 538 nm confirmed the successful synthesis of S4-GoNPs. The average particle size was determined as 120.5 nm with Pdi = 0.152, and −27.6 mV zeta potential. Using the Scherrer equation, the average crystallite size was calculated as 35.69 nm. S4-GoNPs displayed significant antidiabetic properties, with 40.67% of α-amylase and 91.33% of α-glucosidase inhibition activity. It also exhibited promising antioxidant potential in terms of the DPPH (91.56%) ABTS (76.59%) scavenging. It displayed 31.04% tyrosinase inhibition at 0.1 mg/mL. Moreover, it also demonstrated encouraging antibacterial effects with zones of inhibition ranging from 11.02 – 14.12 mm as compared to 10.55–16.24 mm by the reference streptomycin (at 0.01 mg/disc). In addition, S4-GoNPs also showed potential for the photocatalytic degradation of the industrial dye, methylene blue.

Conclusion

In conclusion, these results suggest the promising applicability of green-synthesized S4-GoNPs in various sectors, including the biomedical, cosmetic, food, and environmental waste management industries.

Keywords: gold nanoparticles, antidiabetic, antioxidant, antibacterial, tyrosinase inhibition

Introduction

Nanotechnology is an emerging field with incredible development in nanoparticle applications for countless scientific and high-tech applications in various fields such as electronics, biomedical, biosensing, food sector industry, clothing, cosmetics, and therapeutics.1–3 Nanomaterials with nanoscale size ranges and large volume ratios have acquired more effective physical and chemical properties than their macroforms.3,4 A series of inventions related to nanotechnology resulted in the production of numerous nano-dimensional materials at the industrial scale.5,6 Further, it is believed that the use of nanomaterials will increase in the everyday life and thus it is essential that these nano materials could be able to establish suitable interactions with various biomolecules and bioactive compounds, both within and on the cell surfaces.6 A report by, Vance et al,7 stated that approximately 1814 nano-based products are available in the market globally for the consumers to use. Moreover, the market share of the nano-based materials is increasing day by day was estimated at USD 79.14 billion in the year 2023 (https://www.fortunebusinessinsights.com/nanotechnology-market-108466).

Nanomaterials can be synthesized using various physical, chemical, and biological forms.2 It has been proven that although the chemical method of nanoparticle synthesis is highly productive, however, it is not effective as it gives rise to a high quantity of hazardous byproducts, low biocompatibility, and involves high cost.2,3,8,9 In contrast, the biological synthesis method is more operative and safe, and attains a superior yield along with environmental friendliness, reduced reagent requirements, and low cost.2,3,9,10 The defensible biosynthesis of noble metal nanoparticles has attracted substantial attention because it uses standard temperature and pressure for the manufacture of nanomaterials, which saves a noteworthy amount of energy and money.11,12 The biological method of nanoparticle synthesis, most commonly called the green synthesis method, involves the use of various biological sources, such as bacteria, fungi, algae, and plants, as reducing and stabilizing agents in the synthesis process.9,11,13 All of these reducing agents are economically sustainable and environment-friendly.14 Of all the biological sources, plant part (such as the leaf, stem, root, and seeds) extracts are considered more suitable because of their easy availability, easy handling, rich bioactive compounds, safe, and large-scale production.9,15 Plant extracts are rich in numerous bioactive compounds with medicinal values that can be incorporated into synthesized nanoparticles, and their potential can be enhanced.16 Plant extracts contain numerous bioactive compounds that have beneficial effects on the reduction and stabilization of nanoparticles.17 The bioactive compounds present in plants and their extracts act as reducing, precipitating, and capping agents, thus substantially influencing the shape, size, and other key features of nanoparticles.3,18 Plant-based biosynthesis of nanomaterials is considered the most acceptable method because of its relatively mild, environmentally friendly, and lucrative properties.19 It has been already proven that plant extracts are rich in a number of bioactive compounds including proteins, carbohydrates, phenols, flavanols, terpenoids, vitamins, etc.19 These constituents play a major role in bioreduction, capping, and stabilization of the synthesized nanomaterials. Plant extract-mediated gold nanoparticles (GoNPs) deliver enhanced properties as compared to the chemically produced GoNPs.20

Metallic nanomaterials have attracted attention because of their applications in diverse fields, including electronics, biomedical, chemical and biological sensors, drug delivery, food packaging, cosmetics, and many more.21 These nanoparticles, because of their small size and high loading capacities, can augment the solubility of herbal medications, thereby administering at the exact affected target area in the body, resulting in greater accuracy and better performance.22 Modification of nanoparticles into various forms has allowed the desired therapeutic agents to defeat the biological obstructions, single out the molecular changes, and take part as a moderator in the process of molecular interactions.23 These nanoparticles may be engaged in directing a natural bioactive component into the exact location of the affected organ, thus enlightening the drug delivery mechanism, choosiness, effectiveness, and protection of the organ, along with the application of lower doses of medications.24 Considering the vast potential of nanomaterials in biomedical fields such as drug delivery, cancer therapies, and antimicrobial targets, there is increasing interest in nanomaterial research and applications. Recently, a number of nanoparticles, such as palladium, gold, silver, and platinum, have been widely tested on the human body.3,9,11,19,22,24 However, because of their unique properties such as versatility, inertness, biocompatibility, and optical, thermal, catalytic, optical-electronic controllable properties and surface modifiability, gold nanoparticles (GoNPs) have been considered the most accepted metal nanoparticles for biomedical applications.19,20,22,25–27

Furthermore, because of their well-defined surface chemistry, GoNPs can be easily conjugated with diverse compounds and molecules, and are not harmful to humans at low doses.26 In addition, GoNPs exhibit antibacterial, antioxidant, antidiabetic, and catalytic properties.3,22,28,29 It has been reported that the synthesis and stability of GoNPs require both capping and reducing agents, and in most cases, synthetic chemicals such as sodium borohydride, hydrazine, and surfactants are typically used in the synthesis process.19,20 However, these synthetic chemical reactions require input energy and must be removed properly after the completion of the reaction process to avoid any toxicity issues in its biomedical use.19 To overcome this issue, the one-pot green synthesis method for gold nanoparticle synthesis using plant material is a reliable and best alternative process.

Syzygium cumini Lam. (commonly called Jamun) is an evergreen tropical tree that belongs to the Myrtaceae family. It has many local names such as black plum, java plum, jambolao (Brazil), Indian berry, damson, etc.30,31 All parts of this plant, such as the seeds, berries, leaves, and bark, are used for medicinal purposes.32,33 Its leaves are acknowledged as an important source of phytochemicals such as tannins, phenolic acids, flavonoids, and terpenoids.34 Polyphenols are considered the major constituents of Jamun leaves.34 Shidiki and Vyas35 have identified 20 compounds such as caffeic acid, 3-(3-hydroxy phenyl) propionic acid, xanthoxylin, ferulic acid, quinic acid, diferulic acid, methyl gallate, gallic acid, astragalin, cianidanol, butin, kaempferide, 4′-hydroxyflavan, taxifolin, isoquercetin, 3,5,7,4′-tetrahydroxy-6-(3-hydroxy-3-methylbutyl) flavone; cedrol, 6-O-feruloyl-D-glucose, palmitic acid. and punicic acid from the aqueous leaf extracts of S. cumini by Liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC-MS) as shown in Supplementary Table 1. Furthermore, a few other authors have also identified a number of bioactive compounds from the aqueous extract of S. cumini leaves using a number of analytical techniques, including high-performance liquid chromatography, liquid chromatography, and nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy, the details of which are presented in Supplementary Table 2.

In addition, these parts are used for the treatment of various ailments. The ash of Jamun leaves has been used for strengthening teeth and gums.36 A decoction of the stem bark and leaves of jamun was used to subside the smell of the armpit.37 Jamun leaves are considered to support liver health and aid the detoxification process.34 Jamun leaves have been reported to be consumed daily by cooking them in water to cure diabetes.30 Leaf juice has been used as an antidote for opium poisoning, and oral intake of the leaves for a few days has been reported to be beneficial in reducing jaundice in human beings.38 Many uses such as antidiabetic, antioxidant, anticancer, antimicrobial, astringent, diuretic, blood strengthener, anti-inflammatory, anti-HIV, anthelmintic, gastroprotective, etc, have been reported for this plant and its parts.31,32,38 It is rich in alkaloids, flavonoids, glycosides, polyphenols, tannins, terpenes, anthraquinones, essential oils, etc.39,40 Further, there are a few reports on the use of JLE in the biosynthesis of different types of nanoparticles and their application in various fields.2,31,41,42 Taken together, it is assumed that the vast resource of bioactive compounds in the jamun tree and its parts is followed by numerous medicinal values and properties as evident from previously published literature, and it is assumed that if this plant part is extracted and its extract is used in the gold nanoparticles (GoNPs) synthesis, then the bioactive compounds present could enhance the activity of the GoNPs by synergistic effects, thereby resulting in improved biological potential of the GoNPs. Considering this, in the current research, the synthesis of gold nanoparticles has been undertaken using the jamun leaf aqueous extract and the investigation of its biological potential in terms of its antioxidant, antidiabetic, antibacterial activity, and photocatalytic degradation of industrial dyes have been attempted.

Materials and Methods

Reagents and Chemicals

All solvents and chemicals were of analytical grade and purchased from Sigma Aldrich, USA, and Daejung Chemicals, Korea. All the reagent solutions were prepared using deionized water.

Jamun Leaf Extract Preparation and Phytochemical Analysis

Fresh leaves of the S. cumini Lam. (commonly called Jamun), collected from the botanical garden of Dongguk University (Figure 1A), were authenticated by the botanical specialist, and a herbarium specimen was prepared and recorded (RIILSEH No. 202211–05) at Dongguk University. Fresh leaves were washed to remove dirt and dust particles, dried, and cut into small pieces, followed by drying at room temperature for 10 days. After 10 d, the leaves were ground into a powder using an electric grinder. Then, 50 g of powdered Jamun leaves (JE) was put in 500 mL of the flask with 250 mL of sterile distilled water, followed by boiling for 15 min to prepare the Jamun leaf extract (JLE). The JLE was cooled to ambient temperature, filtered, and stored in a refrigerator. The presence of various phytochemicals (tannins, saponins, flavonoids, phenols, carbohydrates, terpenoids, proteins, amino acids, anthraquinones, and cardiac steroidal glycosides) in JLE has been investigated using standard referred protocols.43,44 The Gas chromatography–Mass Spectrometry (GC–MS; Agilent Technologies, Inc., USA, 7820A/5975C MSD, GC System and DANI Headspace auto-sampler, DANI Analitica SRL, MI, Italy) was used for the analysis of JLE as per standard established protocol. An HP-5ms Ultra Inert column containing (5%-phenyl)-methylpolysiloxane (30m × 0.25 mm i.d., 0.25 µm film thickness; J & W Scientific, Agilent) was used as the stationary phase and helium as the carrier gas (at a flow rate of 0.8 mL/min), and a mass-selective detector was operated in electron impact ionization mode at 70 eV in the scanning range of m/z 50–550. Integration parameters as autoint1.e and ChemStation as integrators and MassHunter software were used for this purpose. The National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) library was used for precise identification of the bioactive phytocompounds present in JLE.

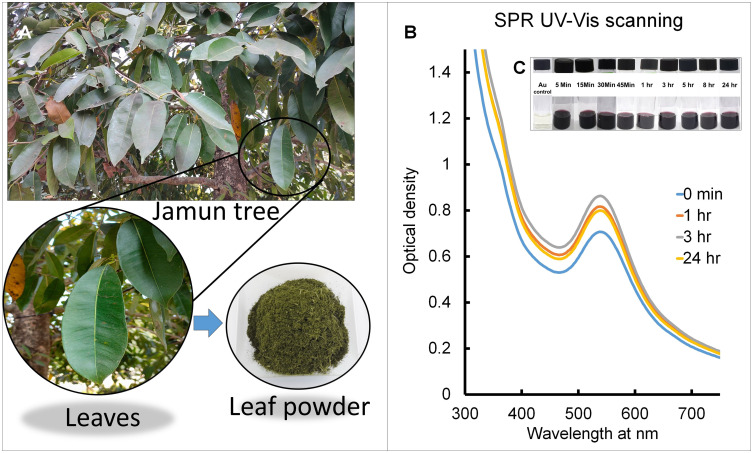

Figure 1.

(A) Photos of Jamun tree and jamun leaf powder; (B) SPR UV-VIS scanning of S4-GoNPs at regular time intervals; (C) visual color changes with time.

Production of GoNPs by JLE and Its Characterizations

For the green synthesis of GoNPs, JLE extract was used as a reducing, capping, and stabilizing agent. Briefly, approximately 100 mL of HAuCl4.3H2O was taken in a 0.5 L flat bottom flask, and approximately 10 mL of JLE was added dropwise with continuous stirring at ambient temperature. The synthesis of GoNPs (S4-GoNPs) was monitored visually, followed by UV–VIS spectral scanning from 300 to 750 nm at every 2 nm interval for 24 h at regular time intervals. Following the confirmation of biological synthesis, the S4-GoNPs solution was centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 20 min together with 3–4 distilled water washes to remove the unattached compounds from the JLE. The dried S4-GoNPs were collected in powder form after drying at room temperature in an oven for further characterization. Following biosynthesis, S4-GoNPs were subjected to various morphological, chemical, and physical characterizations according to the prescribed standardized methodology.45 The nature and elemental composition of the S4-GoNPs were examined by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) machine connected to it. In addition, the surface characteristics were studied using atomic force microscopy (AFM). The crystalline structure was characterized using X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis. The zeta potential and the particle size of green-synthesized S4-GoNPs were assessed using a zeta potential machine. The Thermogravimetric (TGA) instrument estimated the composition and thermal stability of the green synthesized S4-GoNPs from 20°C to 900°C at every 10°C/minute ramping time. Finally, the functional group composition of both JLE and S4-GoNPs was estimated using a Fourier transform infrared spectrophotometer (FTIR) between 4000 and 400 cm−1.

Assessment of the Biomedical Activities of S4-GoNPs

The biomedical properties of green-synthesized S4-GoNPs were explored using the well-recognized antibacterial, antidiabetic, antioxidant, and tyrosinase inhibition potentials. The antibacterial action of S4-GoNPs was investigated using a standard disc diffusion assay against seven foodborne pathogenic bacteria, out of which four are Gram negative: Aeromonas hydrophila ATCC 7966, Escherichia coli O157:H7 ATCC 23514, Salmonella Typhimurium KCTC 1925, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 27583; and three Gram positive: Enterococcus faecium DB01, Pediococcus sp., and Bacillus cereus KCTC 3624.46 Briefly, S4-GoNPs (100 µg/disc) and streptomycin (10 µg/disc) were seeded on culture plates spread with the pathogenic bacteria and incubated at 37 °C for 1 d, followed by a measurement of the diameter of the zone of inhibition around the disc. The minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) and minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC) of both S4-GoNPs and streptomycin (positive reference control) were determined using well-established two-fold dilution methods. The MIC was determined by visual surveillance after a 1-day gestation period and compared with that of control tubes containing only liquid broth media. The minimal S4-GoNPs/streptomycin concentrations with no visual growth of pathogens were considered the MIC values, whereas minimal concentrations that showed no growth in the culture plates were considered the MBC values.

The antidiabetic effects of S4-GoNPs were determined using α-amylase and α-glucosidase enzyme inhibition assays. The α-amylase inhibition potential of S4-GoNPs was investigated following previously used processes with limited adjustments.47,48 Acarbose was taken as a reference-positive control for the experiment. In brief, the tested materials (40 µL, at different concentrations of 0.01 g/1000 µL of dimethyl sulfoxide) were again prepared in 160 µL of 20 mM phosphate buffer saline (pH 6.9), including 0.0067 M sodium chloride in 2 mL bottles, and incubated for 300 s with 200 µL of 4 U/mL α-amylase prepared in ice-cold distilled water. The start of the reaction process was instigated by adding 0.4 mL of soluble potato starch mixture in phosphate buffer saline. After 3 min incubation, trailed by mixing of 0.4 mL of DNS color reagent and heating for 10 min at 90°C in the water bath and subsequent cooling. Approximately 50 µL of the test material was diluted with another 175 µL of water, and the absorbance was measured at 540 nm using a spectrophotometer. Enzyme activity was calculated using Equation 1.

|

(1) |

Where  is the OD of the control, and

is the OD of the control, and  is the OD of the treatment.

is the OD of the treatment.

Similarly, the α-glucosidase inhibition potential of S4-GoNPs was investigated following earlier regular processes with limited adjustments.48 One milliliter of the reaction test material contained S4-GoNPs and acarbose (reference-positive control) at three concentrations (25–100 µg/mL), 4 units/mL of α-glucosidase enzyme, and potassium phosphate buffer at pH 6.8, and was incubated for 10 min. About 100 μL of 3 mM p-nitrophenyl-α-d-glucopyranoside was used as the substrate and the test material was further incubated for another 20 min at 37°C. After completion of the incubation period, 2 mL of Na2CO3 was added to the test material, the optical density (OD) was measured at 405 nm, and enzyme activity was determined using the following equation 1.

Next, the antioxidant effects of the S4-GoNPs were estimated using three different assays, namely DPPH (1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl) radical scavenging, ABTS [2,2-azinobis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid)] radical scavenging, and reducing power assays. The DPPH assay was performed as described by Patra et al.49 Three different concentrations (25–100 μg/mL) of S4-GoNPs and gallic acid (reference-positive control) were used in the experiment. The optical density was determined at 517 nm using a multiplate reader, and the scavenging percentage was calculated using Equation 1. Similarly, for the ABTS assay, the standard protocol of Das et al45 was followed using three different concentrations (25–100 μg/mL) of S4-GoNPs and gallic acid (reference-positive control). The OD values were determined at 734 nm using a multiplate reader, and the scavenging percentage was calculated using Equation 1. The reducing power assay was performed according to the protocol of Das et al45 with three different concentrations (25–100 μg/mL) of S4-GoNPs and gallic acid (reference-positive control). The resulting OD values were recorded at 700 nm. The effective concentration that showed 50% of activity (IC50/IC0.5 value) was calculated from the graph. The tyrosinase inhibition potential of S4-GoNPs was investigated using the protocol described by Das et al.45 For this experiment, three different concentrations (25–100 μg/mL) of S4-GoNPs and Kojic acid (reference-positive control) were used, and the OD values were obtained at 475 nm, followed by the calculation of the inhibition potential using Equation 1.

Assessment of Photocatalytic Degradation of Methylene Blue Industrial Dye

The photocatalytic degradation effects of S4-GoNPs against methylene blue industrial dye were investigated following a standard protocol with minimal modifications.50,51 The degradation of the industrial dye was monitored at regular time intervals by measuring the OD values in the 300–900 nm range, and the percentage degradation was calculated using the following equation:

|

(2) |

where  , is the OD of the dye solution before light contact and

, is the OD of the dye solution before light contact and  is the OD of the dye solution after light contact.

is the OD of the dye solution after light contact.

Statistical Investigation of the S4-GoNPs

Experiments were conducted thrice, and the data were interpreted as mean values with standard deviations. One was the analysis of variance; Duncan’s multiple range test at P < 0.05; Pearson’s correlation, regression analysis, and other calculations were performed using SPSS (version 27.0; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) and OriginPro 2024 version 10.1.

Results and Discussion

In the current study, the leaves of the Jamun tree (Figure 1A) were selected, and their aqueous extracts were prepared for biomediated green synthesis of GoNPs. Prior to the synthesis, a preliminary phytochemical profile of the aqueous JLE was undertaken, and the leaf extract was found to be rich in a number of phytochemicals, such as flavonoids, tannins, terpenoid phenols, anthraquinones, and cardiac glycosides (Table 1). The presence of these phytochemicals has also been reported in previous publications.52–57 A study by Prabhakaran et al58 has also shown the presence of carbohydrates, saponins, tannins, and phenols in jamun leaf extracts. In another study, Bari et al57 have highlighted the presence of flavonoids, saponins, tannins, and phenols in aqueous jamun leaf extracts. Phenolic compounds play a key role in human health by reducing the risk and preventing the growth of some deteriorating diseases, such as cancer, cardiovascular diseases, and diabetes, as well as by combating antioxidant and anti-inflammatory processes.59,60 Further, there is evidence that the leaves of the Jamun tree are rich in a number of compounds including betulinic acid, quercetin, α-pinene, β-sitosterol, α-cadinol, a-terpeneol, L-limonene, eucarvone, α-bornyl acetate, caryophyllene, α-terpineol, and many more.55,56,61–64 A study by Dan et al65 has reported on the quantitative phytochemical prospective of jamun leaf extracts, accounting for 2.05–6.15 mg/g and 1.5–7.5 mg/g of alkaloids and proteins, respectively. In another review, the author reported the presence of 9.1% protein, 4.3% fat, and 17% of fiber in the Jamun leaf.56

Table 1.

Phytochemical Analysis of Aqueous JLE

| Phytochemicals | Aqueous JLE |

|---|---|

| Tannin | + |

| Flavonoids | + |

| Terpenoids | + |

| Saponins | + |

| Phenol | + |

| Carbohydrates | + |

| Proteins & Amino acids | – |

| Anthraquinones | + |

| Cardiac steroidal glycoside | + |

Notes: +, present; -, absent.

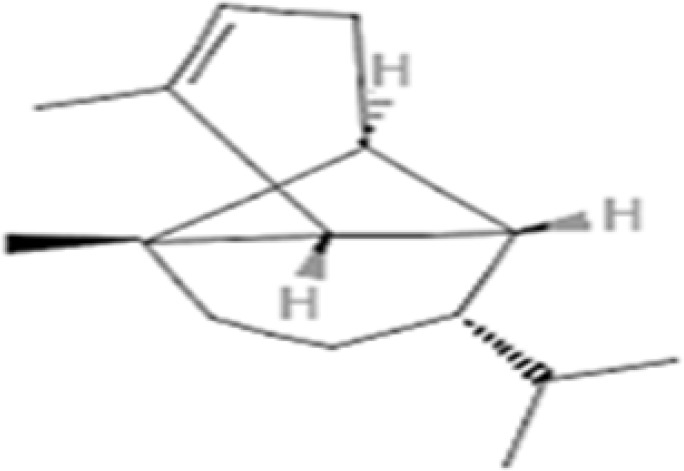

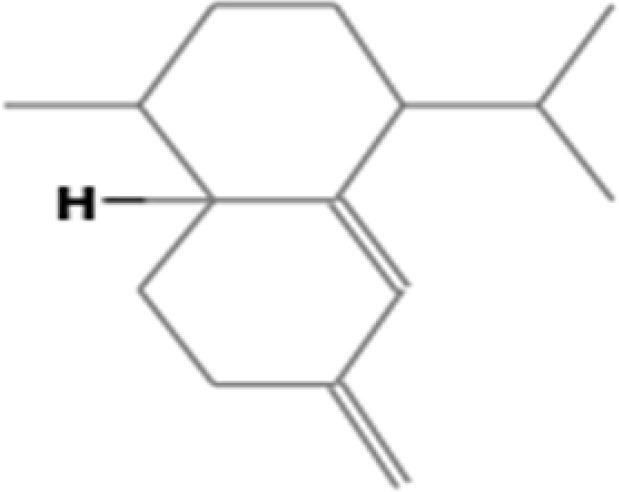

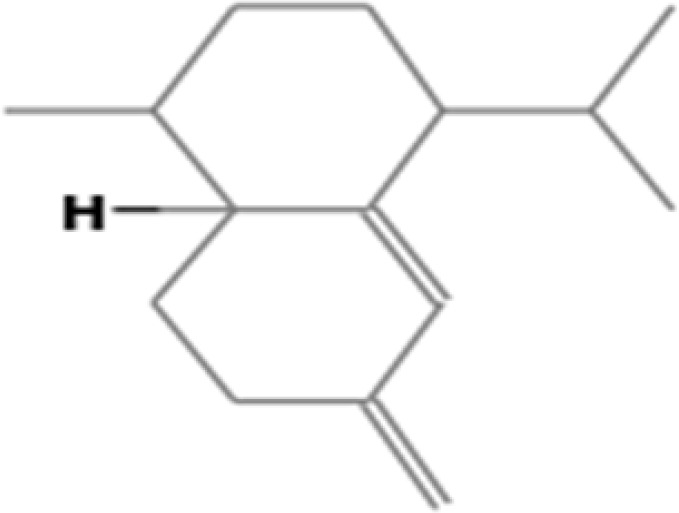

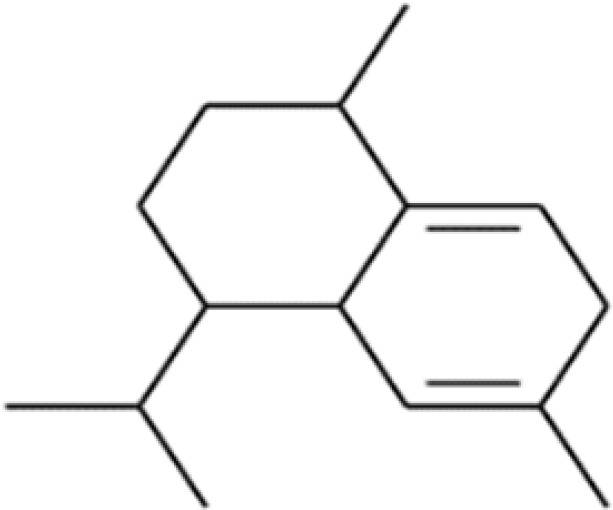

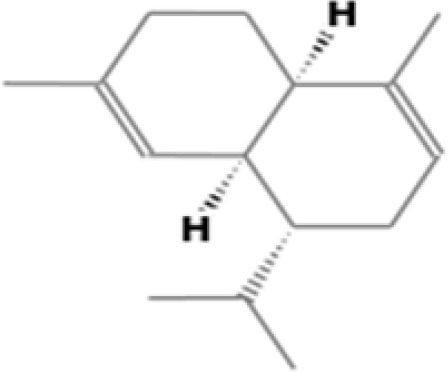

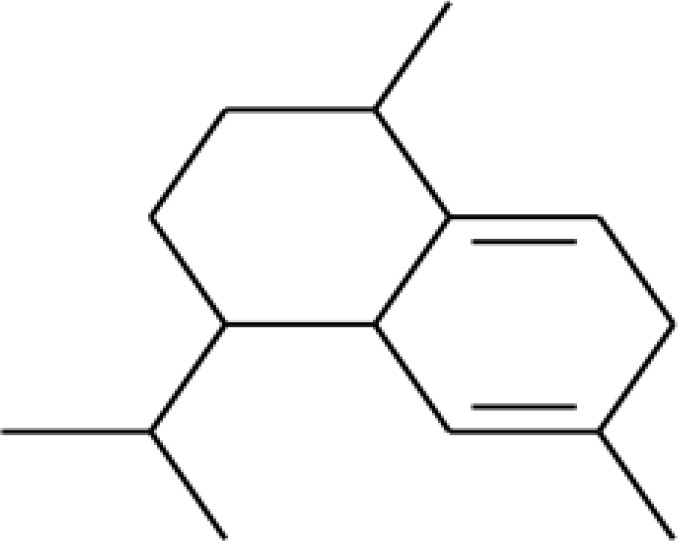

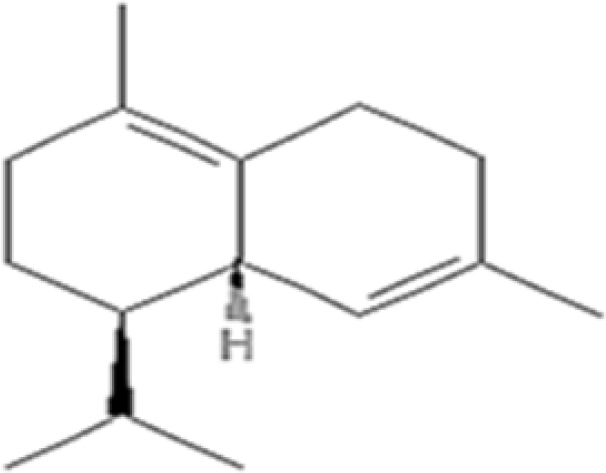

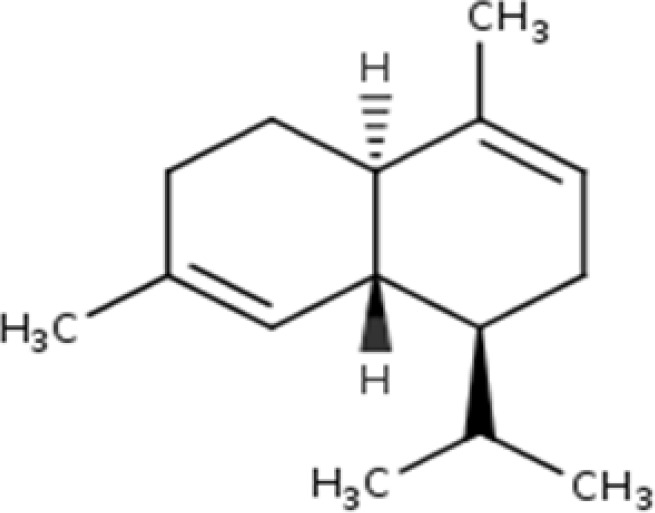

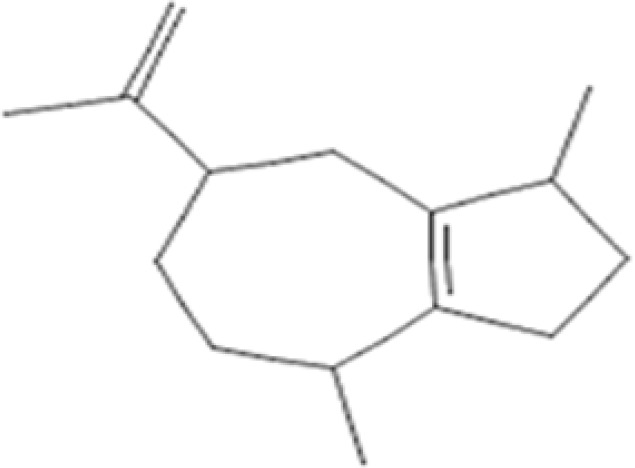

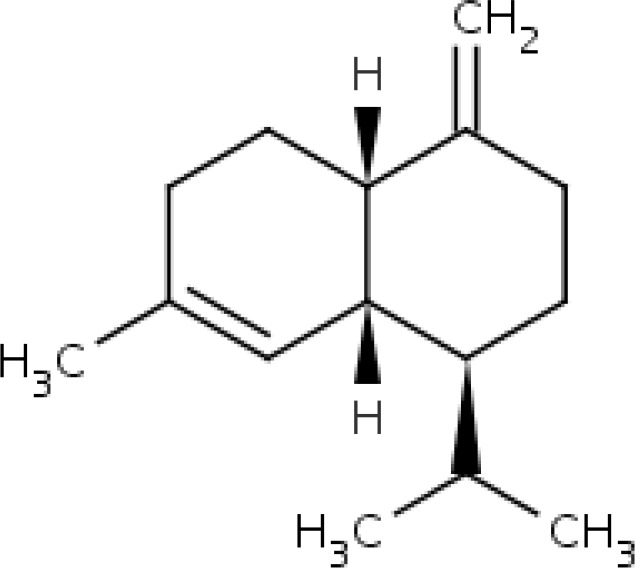

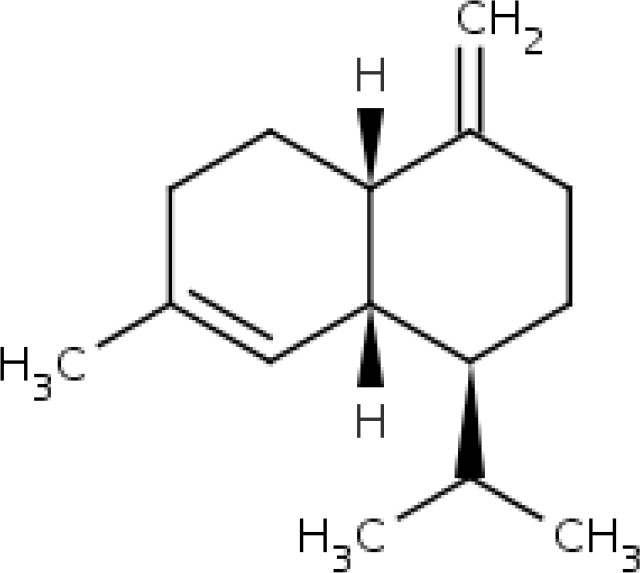

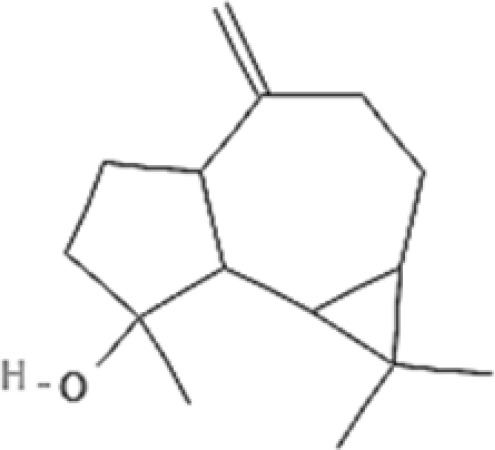

Further characterization of JLE was carried out by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) analysis, and the number of compounds and their percentages are presented in Table 2. The GC-MS analysis of the JLE revealed the presence of a number of compounds, majorly of them as the (1R)-2,6,6-Trimethylbicyclo[3.1.1]hept-2-ene (5.141%), 2(10)-pinene (4.119%), α-cyclopene (5.274%) α, α-muurolene (7.525%), naphthalene, 1,2,3,4,4a,5,6,8a-octahydro-7-methyl-4-methylene-1-(1-methylethyl)-(1.alpha.,4a.beta.,8a.alpha) (8.470%), delta-cadinene (23.246), α-guajene (3.451%), and gamma-muurolene (4.379%) (Table 2). Many of the detected active compounds possessed substantial pharmacological activities, the details of which are discussed below. The medicinal potential and biological activities of the identified compounds are shown in Supplementary Table 3. α- and β-pinenes are monoterpenes with numerous pharmacological properties, such as antimicrobial, antioxidant, antimalarial, anti-inflammatory, anti-nociceptive, anticancer properties, etc.64,66–70 Copaene (α-copaene) is commonly found in essential oils of many plants71,72 and has numerous medicinal properties such as antioxidants and antigenotoxicity.73 (+)-Alpha-muurolene is a natural compound found in some plants with medicinal properties.74,75 Plants rich in compounds such as naphthalene, 1,2,3,4,4a,5,6,8a-octahydro-7-methyl-4-methylene-1-(1-methylethyl)-(1. alpha.,4a.beta.,8a.alpha) have been reported to have anticancer, antimicrobial, and antioxidant potential.76,77 δ-Cadinene is one of the most extensively occurring plant sesquiterpenes, with numerous medicinal properties, including treatment against rheumatic disorders and antimicrobial and antioxidant properties.78–81 Azulene (1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8-octahydro-1,4-dimethyl-7-(1-methylethenyl)-, (1S,4S,7R)-) is a natural product found in many plants. It has a number of biological properties, including anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, antineoplastic, antidiabetic, and antiretroviral properties.82–84 Gamma-muurolene is a sesquiterpene and a carbocyclic compound. 1,2,3,4,4a,5,6,8a-Octahydronaphthalene was substituted at positions 1, 4, and 7 with isopropyl, methylene, and methyl groups, respectively. It has been reported to possess anti-inflammatory, antinociceptive, and antioxidant properties.85,86 Similar compounds in the GC-MS profile of jamun leaf extracts have been reported previously.64,87 The medicinal potential of Jamun tree leaves has also been reported previously.30,56,88 Aqueous leaf extracts have been used in the treatment of diabetes.30,59 Leaf juice has been used as an antidote for opium poisoning and is effective in reducing jaundice38 and dysentery.88 Ahmed et al89 have reported the anti-inflammatory, anti-coagulant, antioxidant, anti-proliferative, and analgesic potential of jamun leaf methanol extract. Because of the presence of these active compounds in the JLE, as evident from the GC-MS results (Table 2) and subsequent literature review, this extract could serve as a potential candidate for reducing, capping, and stabilizing agents in GoNP synthesis, and it could also enhance the biological potential of the synthesized S4-GoNPs. LC-MS analysis of the leaf extract of S. cumini as reported previously identified 20 different compounds, mainly phenolic and flavonoids (Supplementary Table 1),35 which could have acted as reducing, capping, and stabilizing agents in the green synthesis of S4-GoNPs. Phytochemicals play a major role in the stabilization, size control, and minimization of agglomeration as well as the morphology of metal nanoparticles.90 It has been reported that the rich bioactive compounds present in the plant extracts (in this case the JLE) (Tables 1, 2 and Supplementary Table 3), aid in the bioreduction of metal ions to nanoparticles by donating electrons to the metal ions, reducing them followed by stabilizing them in order to minimize the gathering of the nanoparticles.91,92 Besides, these phytochemicals also act as capping agents by forming a layer on the surface of the nanoparticles, as evident from various previous publications.92–94 Furthermore, there are reports discussing that the presence of flavonoids, polyphenols, and proteins in the plant extracts are responsible for their role as a reducing agent in the biosynthesis of nanomaterials.92,93,95,96 A study by Zarzuela et al,97 on the gold nanoparticles, have reported that the flavone sulfate molecules present in the plant extract mainly act as a reducing and stabilizing agent in the nanoparticle synthesis. Another report suggested that the interaction of bioactive compounds on the nanoparticle surface could be responsible for the stabilization of nanomaterials thereby enhancing their applications in various fields such as biomedical, sensors, etc.98

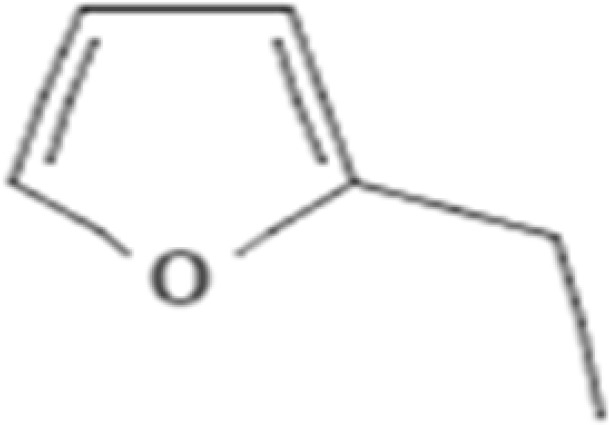

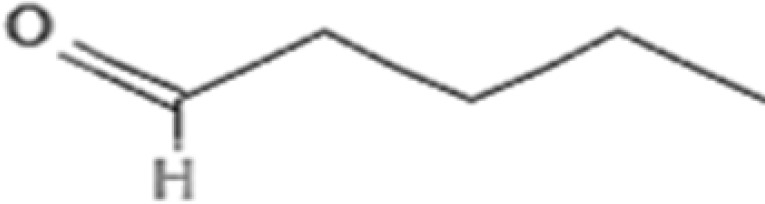

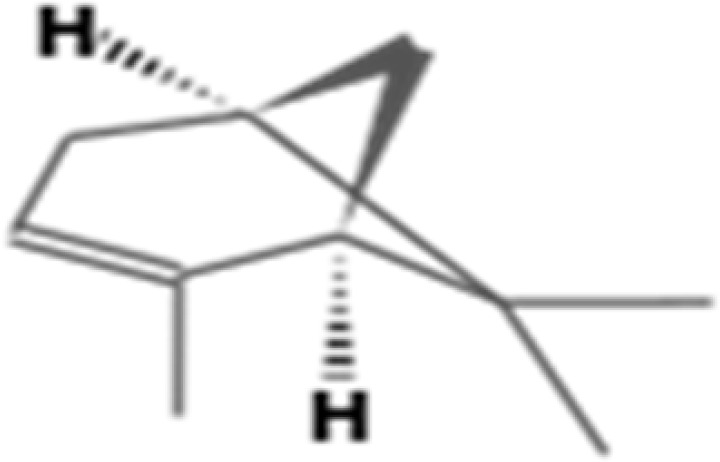

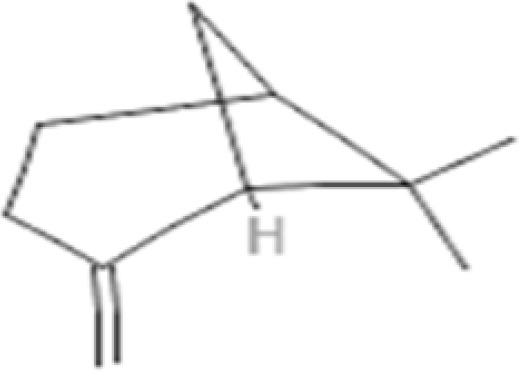

Table 2.

GC-MS Analysis of Jamun Leaf Extract, Chemical Structure, and Percent Composition of the Major Compounds

| No. | Retention Time | Compound Name | Chemical Formula | Mol Wtt. (g/mol) | Chemical Structure | Compound % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | 2.161 | 2-Penten-1-ol, (Z)- | C5H10O | 86.13 |  |

1.083 |

| 2. | 2.295 | Furan, 2-ethyl- | C6H8O | 96.13 |  |

1.400 |

| 3. | 3.337 | Hexanal | C6H12O | 100.16 |  |

2.897 |

| 4. | 6.255 | (1R)-2,6,6-Trimethylbicyclo[3.1.1]hept-2-ene; Cyclohexene, 1-methyl-4-(1-methylethenyl)-, (R)-;. α.-Pinene; Tricyclo[2.2.1.02,6]heptane, 1,7,7-trimethyl-; 2-Pinene; BICYCLO[3.1.1]HEPT-2-ENE, 2,6,6-TRIMETHYL-; | C10H16 | 136.23 |  |

5.141 |

| 5. | 7.569 | 2(10)-Pinene; Bicyclo[3.1.1]heptane, 6.6-dimethyl-2-methylene-, (1S)- | C10H16 | 136.23 |  |

4.119 |

| 6. | 23.961 | Alfa-Copaene; Copaene | C15H24 | 204.35 |  |

5.274 |

| 7. | 27.506 | (+)-epi-Bicyclosesquiphellandrene; cis-Muurola-4(15),5-diene | C15H24 | 204.35 |  |

1.5 |

| 8. | 28.664 | (+)-epi-Bicyclosesquiphellandrene | C15H24 | 204.35 |  |

1.009 |

| 9. | 28.828 | Naphthalene, 1,2,3,4,4a,7-hexahydro-1,6-dimethyl-4-(1-methylethyl)-; CADINA-1,4-DIENE | C15H24 | 204.35 |  |

1.389 |

| 10. | 29.056 | alpha.-Muurolene | C15H24 | 204.35 |  |

7.525 |

| 11. | 29.575 | Naphthalene, 1,2,3,4,4a,5,6,8a-octahydro-7-methyl-4-methylene-1-(1-methylethyl)-, (1.alpha.,4a.beta.,8a.alpha.)-; Naphthalene, 1,2,4a,5,6,8a-hexahydro-4,7-dimethyl-1-(1-methylethyl)- | C15H24 | 204.35 |  |

8.470 |

| 12. | 29.975 | delta.-Cadinene | C15H24 | 204.35 |  |

23.246 |

| 13. | 30.285 | Cubenene | C8H4 | 100.12 |  |

1.483 |

| 14. | 30.491 | Naphthalene, 1,2,4a,5,6,8a-hexahydro-4,7-dimethyl-1-(1-methylethyl)-, [1S-(1.alpha.,4a.beta.,8a.alpha.)]-;.alpha.-cadinene | C15H24 | 204.35 |  |

1.694 |

| 15. | 31.995 | 1,H-Dimethyl-7(1-hydroxy-1-methylethyl)[3,3a,4,5,6,7]hexahydro azulene; alpha-Guajene | C15H24 | 204.35 |  |

3.451 |

| 16. | 34.455 | 1-ISOPROPYL-7-METHYL-4-METHYLENE-1,2,3,4,4A,5,6,8A-OCTAHYDRONAPHTHALENE;.gamma.-Muurolene; | C15H24 | 204.3511 |  |

4.379 |

| 17. | 35.045 | 6.alpha.-Cadina-4,9-diene, (-)-;.gamma.-Muurolene | C15H24 | 204.3511 |  |

1.624 |

| 18. | 36.630 | 1,1,7-TRIMETHYL-4-METHYLENEDECAHYDRO-1H-CYCLOPROPA[E]AZULENE | C15H24O | 220.35 |  |

6.156 |

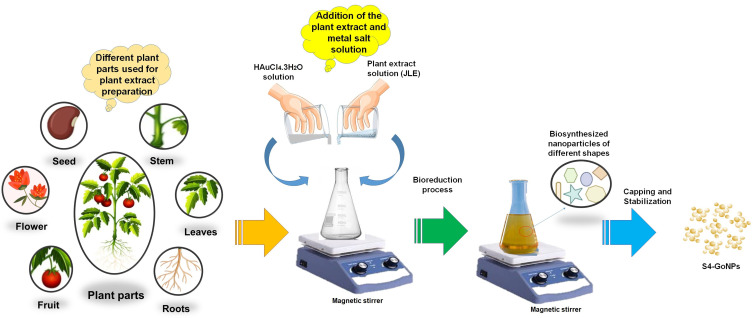

After preliminary phytochemical screening, JLE was used as a reducing agent in the green synthesis of S4-GoNPs via a one-pot process. In the current case, an easy, one-pot synthesis method has been adopted for the synthesis of S4-GoNPs at normal temperature and neutral pH condition. It is known that the physical and chemical methods of synthesis of nanoparticles utilize various toxic chemicals and extremely harsh conditions,6 whereas in the bioinspired synthesis of S4-GoNPs, non-toxic chemicals and ambient temperature and pressure have been used that indicated an ecofriendly and cost-effective method of nanomaterial synthesis. A detailed schematic diagram describing the bioinspired synthesis of S4-GoNPs is presented in Figure 2, for a better understanding of the synthesis process. The possible mechanism of the biosynthesis involves the bioactive compounds from the plant extract acts as the reducing agents by donating electrons to the metal ions, reducing them followed by stabilizing them in order to minimize the gathering of the nanoparticles.91,92 Furthermore, these phytochemicals also act as the capping agents by forming a layer on the surface of the nanoparticles, as evident from discussions made in a number of earlier literature.6,92–94,96

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram showing the biosynthesis of gold nanoparticles using plant extracts.

The progression of nanoparticle synthesis was monitored visually from time to time (Figure 1B and C), and it was observed that the synthesis process of S4-GoNPs was very rapid, and there was an immediate change in the color of the solution from yellowish to dark purple after 5 min of addition of JLE to the reaction medium (Figure 1C). The entire process was prominent after 3 h of incubation, which was evident from the UV–VIS spectral analysis, which showed a steady peak at 538 nm (Figure 1B).

It is reported that, in aqueous solution, the spherical GoNPs displayed a spectrum of colors ranging from brown, orange, red, and purple as the core size increases from 1 to 100 nm, and usually display a size-relative absorption maximum between 500 and 550 nm.99 Same phenomenon is observed in the current study (Figure 1C). For noble metal nanoparticles, light in the visible region of the electromagnetic spectrum couples to localized surface plasmon resonances, leading to intense destruction that causes colloidal interruptions of noble metal nanoparticles to display rich colors.100,101 Thus, in the case of the GoNPs, they show the complementary color of green or yellow, which is red or purple.101 The UV-VIS absorption spectroscopy measures the level at which the absorbing substance vitiates the electronmagnetic radiations; further, it can also be used in the examination of variations in the absorption levels of individual compounds.23 The phytochemical constituents of the Jamun leaf extract, such as polyphenols, flavonoids, tannins, carotenoids, and terpenoids, are involved in the bioreduction of Au3+ ions to Au0 19. Surface plasmon resonance is the oscillation of free electrons on the surface of a solid material, and it was found at 538 nm for S4-GoNPs (Figure 1B). Similar SPR in the range of 500–550 nm on gold nanoparticle synthesis using plant extracts has been reported earlier.102 Mie’s theory for metal nanoparticles suggests the formation of SPR due to the free electrons and the single SPR band related to the creation of round nanoparticles, whereas the formation of two absorption peaks in UV–VIS scanning is related to the creation of irregular and anisotropic morphology.102–105 To confirm the stability, S4-GoNPs were maintained for 24 h, and the stable position of the SPR peak after 24 h confirmed the stable biosynthesis of the GoNPs (Figure 1B).

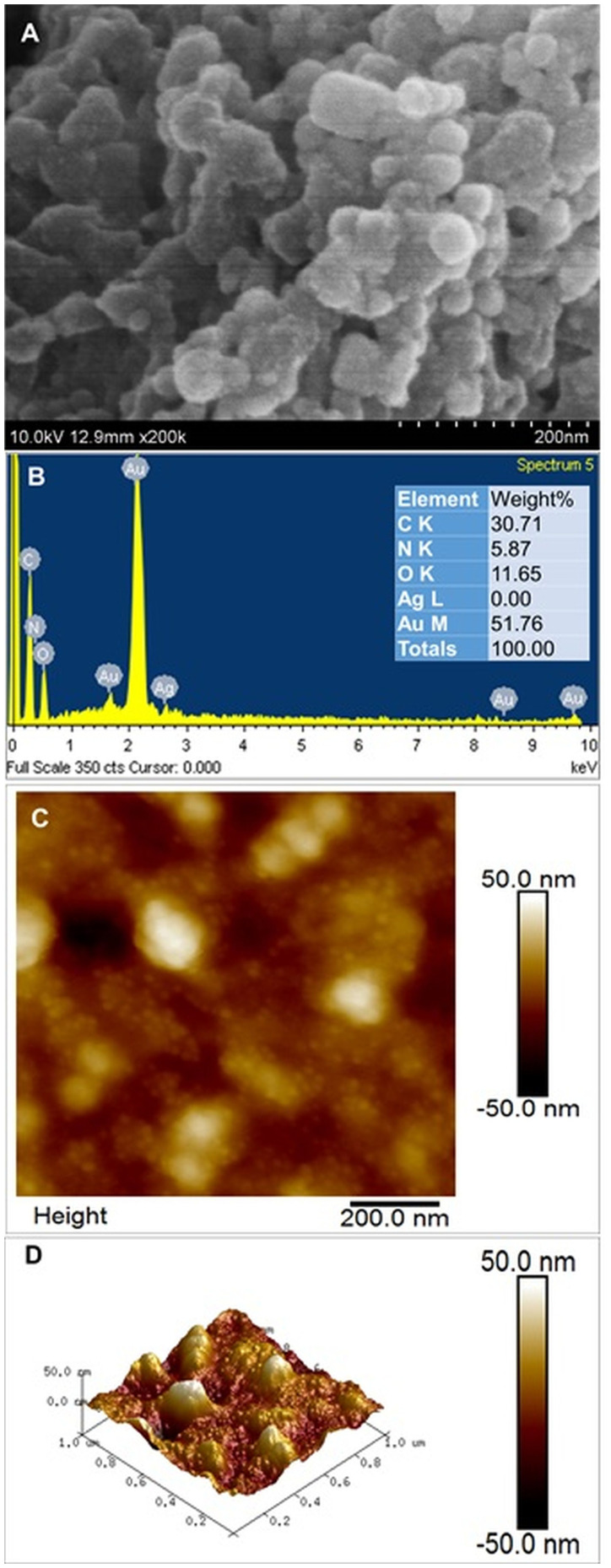

After confirming the synthesis of S4-GoNPs, they were subjected to several morphological, chemical, and physical characterizations. The morphology and elemental composition of the nanoparticles were determined using SEM-EDX analysis (Figure 3A and B). The SEM image demonstrates the uniform distribution of the spherical nanoparticles. However, the image shows agglomeration of the nanomaterials, which might be due to the use of a less advanced SEM machine for taking the images; however, when the said nanoparticles are visualized under the 2D AFM machine, clear and distinct spherical-shaped nanoparticles are observed that confirmed that the said nanoparticles are not aggregated. Moreover, due to the limited resolution of SEM, no clear differences in the size or shape of the obtained S4-GoNPs were observed. This result is similar to that obtained in previous publications.106,107 There are reports that green-synthesized nanoparticles are often agglomerated owing to the strong polarity and electrostatic attraction between nanoparticles.108 It has been reported that sphere-shaped nanoparticles tend to agglomerate more easily because of the easy contact between adjacent particles, which might be the case in S4-GoNPs, which are spherical in nature.109 Figure 3B shows the EDX spectra of S4-GoNPs. Typically, metallic nanoparticles show SPR absorption peaks in the range of 2–2.5 keV and which is also evident in our current study, the result of which showed an absorption peak at 2.2 keV (Figure 3B). This confirmed the successful manufacture of pure GoNPs. The presence of other peaks, such as carbon, nitrogen, and oxygen, could be due to the bioactive compounds present in JLE, which were used in the bioreduction synthesis of S4-GoNPs.110 Besides, another peak of silver (Ag) was seen in the EDX image, which is due to technical error from the machine, as its nonexistence was confirmed since its percent is 0% as evident from the associated table. Similar results have been previously published.102,106,111 The surface morphology of the S4-GoNPs, as shown by 2D and 3D AFM analyses with subnanometer resolution, showed morphology with clear and distinct spherical nanoparticles (Figure 3C and D). The 3D images revealed that the S4-GoNPs distribution was small. A direct scrutiny of the AFM images revealed that the size of the S4-GoNPs was in the range of 1–50 nm. Similar results have been previously reported for other gold nanomaterials.112–116

Figure 3.

(A) SEM image of S4-GoNPs (inset: magnified view); (B) EDS spectra of S4-GoNPs; (C) 2D AFM image; (D) 3D AFM image.

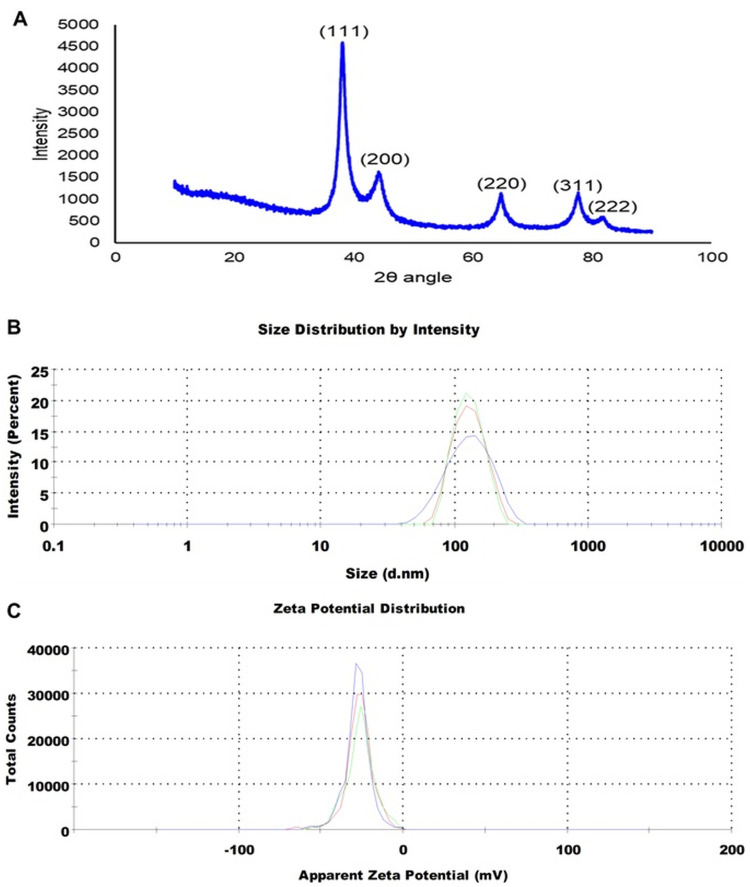

XRD analysis depicts the crystalline structure of nanomaterials, owing to their ability to interact with the electrons of the inner shell of an atom.113 In the present study, the XRD spectra of S4-GoNPs were scanned from 10° to 90° (Figure 4A). The S4-GoNPs were in nanostructures, as demonstrated by Bragg’s diffraction peaks at 2θ values of 38.20°, 44.37°, 64.77°, 77.56°, and 82.01°, matching the (111), (200), (220), (311), and (222) planes, which are identical to those of the normal gold metal Au0 (JCPDS card no. 04–0784).106,117 The diffraction peaks were related to the facets of the face-centered cubic (FCC) crystal lattice, and the widths of the corresponding planes were used to calculate the crystallite size.113 The average crystallite size of S4-GoNPs was calculated as 35.69 nm from the Scherrer equation,118 and a degree of crystallinity of 72.23% was calculated using the OriginPro 2024, version 10.1 software. Similarly, XRD diffraction peaks were also reported in another study on gold nanoparticle synthesis using S. cumini leaf extract.42 The intense diffraction peak at 38.20° confirmed that the preferred growth orientation of zero valent gold was fixed in (111) direction in a flat position on the planar surface (Figure 4A), and the current result attributes to the molecular-sized solids formed with an imitating 3D pattern of atoms or molecules with an equal distance between each part.119–121 Additionally, the reflections corresponding to (200), (220), (311), and (222) were feeble and extended, which demonstrates that the nanoparticles are of smaller size.121,122 This XRD pattern is typical of pure gold nanocrystals.119

Figure 4.

(A) XRD image of S4-GoNPs; (B) Particle size distribution and (C) Zeta potential of S4-GoNPs.

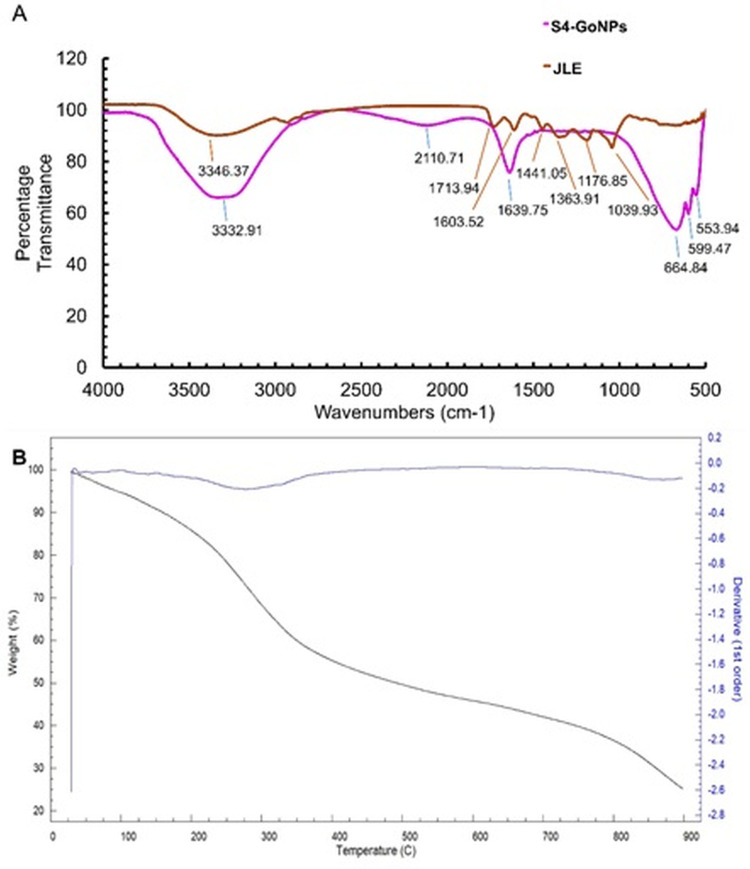

The particle size distribution determined by DLS and the zeta potential analysis confirmed that the hydrodynamic diameter of S4-GoNPs was 120.5 nm with a Pdi of 0.152 and a zeta potential of −27.6 mV (Figure 4B and C). It is observed that the zeta potential data are a good indicator of degree of electrostatic interaction among the scattered particles and hence it is used for quantitative measurement of the charge-induced colloidal stability.123,124 It should be noted that the zeta potential was highly negative, which indicated that the S4-GoNPs repel each other and are less likely to join together, resulting in the stability of the synthesized nanomaterial. Similar reports on the high zeta potential and their colloidal stability have also been reported in earlier published literatures.102,125–127 FTIR spectroscopy aids in molecular fingerprinting for the elucidation of organic materials present in biological samples.113 FTIR analysis was performed to check for the presence of various types of functional groups present in the JLE, which may be responsible for the reduction, capping, and stabilization of S4-GoNPs. Around seven distinct peaks such as 3346.37 cm−1 representing O–H stretching, H-bond of alcohols; 1713.94 cm−1 representing C=O stretch of carbonyl group; 1603.52 cm−1 representing N–H bend of primary amines; 1441.05 cm−1 and 1363.91 cm−1 representing C–H bend of alkanes, methyl group; 1176.85 cm−1 represents C-O stretch of tertiary alcohol; and 1039.93 cm−1 representing C–N stretch of aliphatic amines was seen in case of the JLE (Figure 5A, Table 3). While in the S4-GoNPs, only six peaks such as 3332.91 cm−1 representing O–H stretching, H-bond of alcohols and phenols; 2110.71 cm−1 representing –C≡C– stretch of alkynes; 1639.75 cm−1 representing C=O stretch of carbonyls (general); 664.84 cm−1, 599.47 cm−1, and 553.94 cm−1 representing C–Br stretch of alkyl halides with a halogen attached to it was seen (Figure 5A, Table 3).106,128,129 A similar report on the FT-IR spectra of jamun leaf extract was reported earlier, with three distinctive peaks at 3296.13 cm−1, 2125.40 cm−1, and 1635.85 cm−1 representing carboxylic acid, misc compounds, and amides stretch, respectively.130 A deviation in the peak positions was observed in the S4-GoNPs from that of the JLE, which could be attributed to the utilization of the bioactive compounds from the JLE in the bioreduction, capping, and stabilization of the nanomaterials.131 In addition, it was proven that there was a weak intermolecular interaction and decrease in the mechanical properties between the S4-GoNPs and the JLE, which resulted in a slight decrease in the stretching vibrations to lower numbers in the case of the S4-GoNPs.132 The most significant change detected in the FTIR spectrum of S4-GoNPs was the shift of the 3346.37 cm−1 wavenumber of JLE to a slightly lower wavenumber of 3332.91 cm−1 in S4-GoNPs, representing the O–H stretching and H-bonding of alcohols and phenols. These shifting changes indicate that a new molecular interaction is probably exposed to hydrogen bonding, signifying that these groups were placed in a new chemical environment, as discussed in the earlier literature.132 All of these bands clearly indicate the presence of polyphenols, proteins, and flavonoids in JLE, which act as reductants for the GoNPs to be synthesized.106,110,113 The IR spectra denote the exact fingerprint of the components of a sample with the adsorption peaks corresponding to the vibration frequencies among different bonds of atoms comprising the specific compound. Because the different compounds are the exclusive groupings of various atoms, no two compounds can produce the same IR spectra; thus, the qualitative analysis of the components of the extracts can be properly identified by FT-IR analysis.133

Figure 5.

(A) FT-IR image of S4-GoNPs and JLE extract; (B) TGA image of S4-GoNPs.

Table 3.

FTIR Analysis of JLE and S4-GoNPs

| Extract Name | Peaks | Functional Groups Range | Vibrational Clusters |

|---|---|---|---|

| JLE | 3346.37 cm−1 | Hydrogen bonded 3500–3200 cm-1 | O–H stretching, H-bond |

| 1713.94 cm−1 | The carbonyl stretch C=O of a carboxylic acid appears as an intense band from 1760–1690 cm-1. | C=O stretch | |

| 1603.52 cm−1 | From 1650–1580 cm-1, amines | N–H bend of primary amines | |

| 1441.05 cm−1 | From 1450–1375 cm-1, alkenes, methyl group | C–H bend of alkanes | |

| 1363.91 cm−1 | C–H rock, methyl from 1370–1350 cm-1 | C–H bend of alkanes | |

| 1176.85 cm−1 | From 1205–1124 cm-1, tertiary alcohol | C-O stretch of tertiary alcohol | |

| 1039.93 cm−1 | CO-O-CO stretching anhydride | C–N stretch of aliphatic amines | |

| S4-GoNPs | 3332.91 cm−1 | Hydrogen bonded 3500–3200 cm-1 | O–H stretching, H-bond of alcohols and phenols |

| 2110.71 cm−1 | From 2260–2100 cm-1, alkynes | –C≡C– stretch of alkynes | |

| 1639.75 cm−1 | Carbonyl(C=O) stretching vibrations typically seen between 1800 and 1600cm-1 | C=O stretch of carbonyls (general) | |

| 664.84 cm−1 | C–X stretch 690–515 cm-1 of Alkyl halides (Alkyl halides are compounds that have a C–X bond, where X is a halogen: bromine, chlorine, fluorene, or iodine.) | C–X stretch of alkyl halides | |

| 599.47 cm−1 | |||

| 553.94 cm−1 |

Finally, the decomposition effect of the S4-GoNPs was analyzed by the TGA analysis at high temperatures from 25° to 900°C (Figure 5B). The TGA graph depicts three-phase weight loss, starting from 29.83°C to 275.04°C (1st phase), accounting for 26.44% of weight loss, which might be due to the evaporation of thin-layer decomposition of water and other smaller molecules present on the outer surface of the nanoparticle (Figure 5B). The second phase of weight loss from 275.04°C to 825.00°C accounting for a weight loss of 39.21% is due to the presence of organic matter and bioactive compounds from the JLE attached to the S4-GoNPs that could have aided in the bioreduction, capping, and the stabilization of the nanomaterials.134,135 This maximum weight loss during the second phase might be due to the increased number of intermolecular interactions for each S4-GoNP molecule with an increase in JLE concentration.132 The third phase of weight loss, from 825.00 to 900.00°C, corresponded to a 9.15% loss (Figure 5B). This might also be due to the decomposition of the residues and degradation of resistant aromatic compounds present in JLE.19,132,136,137 Based on the TGA results, the enhanced thermal strength of the S4-GoNPs can be attributed to the formation of hydrogen bonds between the GoNPs and JLE, as is evident from the FTIR analysis. Possibly, due to the changes witnessed in the crystallinity, from the second degradation temperature, the weight loss increased and achieved a maximum weight loss of 39.21% at 825.00°C which could be due to the interactions between the GoNPs and the JLE during the formation of S4-GoNPs.132

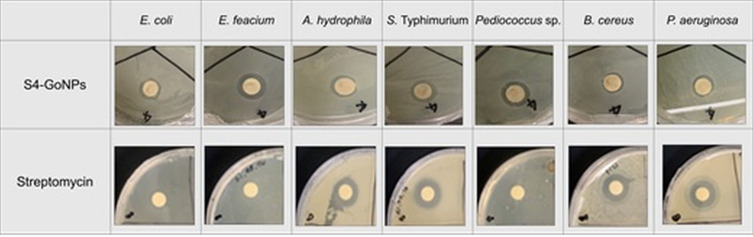

After confirmation of the synthesis of S4-GoNPs, various types of biomedical applications, including antibacterial, antidiabetic, tyrosinase inhibition, antioxidant potential, and photocatalytic degradation of industrial dyes, were investigated. The antibacterial potential of the S4-GoNPs was evaluated by disc diffusion assay against seven foodborne pathogenic bacteria: E. coli, E. faecium, A. hydrophila, S. Typhimurium, Pediococcus sp., B. cereus, and P. aeruginosa (Tables 4 and 5, Figure 6).

Table 4.

Antibacterial Effects of S4-GoNPs and Streptomycin Against the Pathogenic Bacteria

| E. coli | E. faecium | A. hydrophila | S. Typhimurium | Pediococcus sp. | B. cereus | P. aeruginosa | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S4-GoNPs | 11.93e±0.23 | 14.12c±0.36 | 11.34fg±0.84 | 12.89d±0.26 | 12.64d±0.09 | 11.02gh±0.26 | 11.77ef±0.11 |

| Streptomycin | 11.64ef±0.62 | 10.55h±0.19 | 15.99b±0.35 | 16.24b±0.08 | – | 15.84b±0.31 | 16.83a±0.28 |

Notes: *Data are presented as the mean diameter of inhibition zones (mm ± standard deviation). Numbers with different superscript letters are statistically significant at P<0.05.

Table 5.

MIC and MBC of S4-GoNPs and Streptomycin Against Pathogenic Bacteria

| Bacteria | S4-GoNPs | Streptomycin | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MIC* | MBC* | MIC* | MBC* | |

| E. coli | 50* | 100 | 5 | 10 |

| E. faecium | 50 | 100 | 10 | >10 |

| A. hydrophila | 50 | 100 | 5 | 10 |

| S. Typhimurium | 50 | 100 | 5 | 10 |

| Pediococcus sp. | 50 | 100 | – | – |

| B. cereus | >50 | 100 | 5 | 10 |

| P. aeruginosa | 50 | 100 | 5 | 10 |

Notes: *Values in µg/mL.

Figure 6.

Antibacterial activity of S4-GoNPs and streptomycin against pathogenic bacteria.

The results depicted the potential effects of the S4-GoNPs against all tested pathogens, with the diameters of the zones of inhibition ranging between 11.02 – 14.12 mm at a concentration of 100 µg/disc (Table 4, Figure 6). Among the tested pathogens, S4-GoNPs were more active against E. faecium (14.12 mm inhibition zone) and least active against B. cereus (11.02 mm inhibition zone). The results were compared with those of the positive reference standard antibiotic streptomycin, which showed inhibition zone diameters ranged from 10.55 – 16.24 mm at a concentration of 10 µg/disc (Table 4, Figure 6). Besides, streptomycin, other standard antibiotics were also tested; however, only the streptomycin that showed promising results against most of the pathogens are presented in the current study. However, streptomycin was ineffective against B. cereus. To determine the concentration of S4-GoNPs and streptomycin, bacterial growth was inhibited, or complete death of the bacteria was triggered, and the MIC and MBC values were checked against all pathogens, ranging between 50 and 100 µg/mL and 5 – >10 µg/mL, respectively (Table 5). The variation in the diameter of the zone of inhibition might be due to the morphological changes associated with each pathogenic bacterium, and it may be associated with the presence of hydroxyl groups in phenolic compounds and different chemical compounds present in JLE that acted as reducing and capping agents in the formulation of S4-GoNPs. These results confirmed that S4-GoNPs, because of their small size and configuration, are effective against a range of pathogens and could serve as an alternative solution against multidrug-resistant pathogens, where most of the standard antibiotics are ineffective. The probable mode of antibacterial action of the S4-GoNPs could be attributed to their smaller size, which might facilitate their easy penetration into the bacterial cell and consequential perforation of the cell membrane, leading to the release of cellular components outside, thereby causing immediate cellular lysis.46,138,139 In addition, other studies have reported that the presence of phenolic compounds could affect the phospholipid layers of the cell wall, resulting in membrane rupture,132,140 and this could also be the case in the current study, where the phenolic compounds present in JLE acting as capping agents in S4-GoNPs could be a reason for its antibacterial activity. In a study by Singh et al141 on the antioxidant and antimicrobial activity of the jambolan fruit polyphenols, the author has shown that the extract was active against a number of pathogens (Staphylococcus aureus, methicillin-resistant S. aureus [MRSA], E. coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Candida albicans) with a zone of inhibition and minimum inhibitory concentration in the range from 14.3 – 23.0 mm and 0.5–2.5 mg/mL, respectively.141 However, in the current study, it was found that the diameter of the zone of inhibition exhibited by the S4-GoNPs ranged from 11.02 – 14.12 mm at a concentration of 100 µg/disc and MIC ranged between 50 and 100 µg/mL (Tables 4 and 5; Figure 6), which is much lower than previously reported. Similarly, in another study, the authors reported the antibacterial activity of Jamun leaf extracts (in various nonpolar solvents such as petroleum ether, ethyl acetate, acetone, methanol, and ethanol), with maximum activity in petroleum ether and ethanolic solvents against S. aureus and E. coli (inhibition zone of 8–24 mm and MIC and MBC values varied from 1.56 25 mg/mL and 1.56 50 mg/mL).142 These results prove the effective potential of JLE, but they are much higher than those of S4-GoNPs in the current study (Tables 4 and 5; Figure 6). In an old report from 2007, the author has studied the antimicrobial activity of the Jamun leaf hydroalcoholic extracts against the pathogenic bacteria, namely, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and S. aureus 9.00–10.00 mm of inhibition diameter,143 and the results are comparable to S4-GoNPs results. Diksha et al42 studied the antibacterial effects of AuNPs synthesized using the leaf extract of S. cumini against a number of pathogens, including S. aureus, A. baumannii, E. coli, P. aeruginosa, E. faecalis, K. pneumoniae, and P. vulgaris with MIC values ranging between 250 – 450 μg/mL.42 However, the current S4-GoNPs displayed a comparatively better MIC range of 50–100 µg/mL (Tables 4 and 5; Figure 6), which proves the superior synthetic process and effective potential of S4-GoNPs. Other researchers have observed similar findings for plant extract-mediated GoNPs against a number of clinical and cultural bacterial strains and established considerable antibacterial activity.9,42,137,144,145 A further advantage of using nanoparticles in antibacterial treatment is that the bacteria are not able to mutate their genes in the nanoparticle-enabled treatment process.9,146

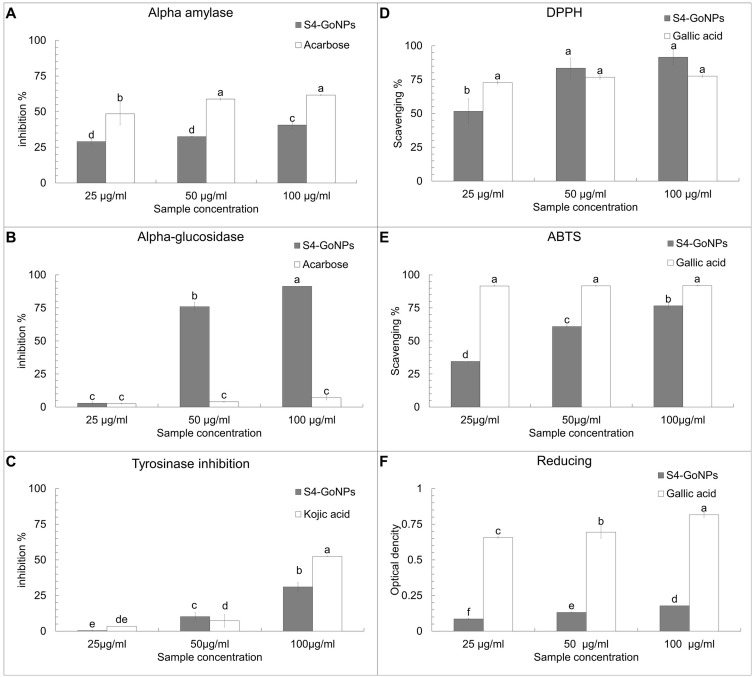

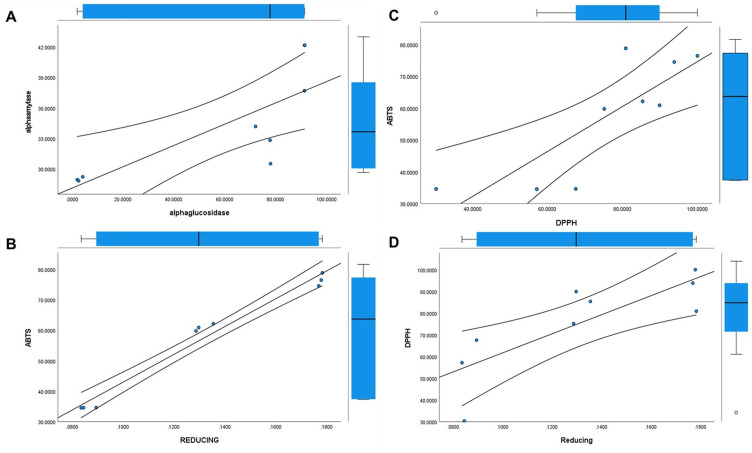

α-Amylase and α-glucosidase enzyme assays were performed to study the antidiabetic potential of S4-GoNPs and the results showed promising outcomes as compared with the acarbose, taken as the reference-positive control (Figure 7A and B). The results demonstrated the potential antidiabetic effect of S4-GoNPs with approximately 28.97–40.67% of the α-amylase enzyme inhibition activity at three different concentrations (25–100 µg/mL) (Figure 7A). Meanwhile, acarbose as the positive control exhibited 48.46–61.62% inhibition activity at the same concentrations (Figure 7A). The effective concentration (IC50) that inhibited 50% of α-amylase enzyme was found to be 120.94 µg/mL for S4-GoNPs and 49.80 µg/mL for acarbose (Table 6). Similarly, in the case of the α-glucosidase enzyme activity, the effect of S4-GoNPs ranged from 2.94% – 91.33%, with the maximum effect observed at the high concentrations of 50 µg/mL (75.93%) and 100 µg/mL (91.33%) (Figure 7B). Besides, acarbose, taken as a reference-positive control, displayed much lower α-glucosidase enzyme activity with 2.56–7.01% at the same concentrations. The effective concentration (IC50) that inhibited 50% of α- glucosidase enzyme was found to be 43.83 µg/mL for S4-GoNPs, whereas it was found as 771.08 µg/mL for acarbose (Table 6). Linear regression analyses were performed using the SPSS statistical analysis software to determine the association between α-amylase and α-glucosidase, which showed a positive trend between the parameters (Figure 8A). The α-amylase enzyme is found in human saliva and is responsible for transforming complex starch molecules into their simpler form of glucose.147 Therefore, inhibiting the effect of α-amylase in the body could be helpful in regulating carbohydrate metabolism in the body, subsequently reducing the amount of glucose absorbed.147 Additionally, a key approach for the hindrance of a strident increase in blood sugar levels is to prevent the effect of the starch-blocking enzyme α-glucosidase.147 Reports say that GoNPs have been shown to enhance the antioxidant system of the human body, thereby protecting the kidney cells from oxidative damages and reducing the risk of progression of diabetic nephropathy.148,149 Ramachandran et al150 concluded that wedelolactone mediated GoNPs were used successfully to regulate the Bcl-2 family proteins expression, and curtail the lipid peroxidation, in order to enhance the antioxidants and insulin secretions through the GLUT2 pathway in RIN-5F cell lines.150 Plants contain a number of phytochemicals such as berberine, strychinine, asaronic acid, and apigenin, which have been used as plant-based diabetic drugs.151 Considering these, the GoNPs synthesis using plant extracts could be assumed to possess enhanced antidiabetic effects. In a study, Bakshi et al152 studied the antidiabetic potential of S. cumini leaf methanol extracts by both α-amylase and α-glucosidase enzyme inhibition activity and have found the inhibition activity with IC50 values of 48.34 and 30.15 µg/mL, respectively, for both the assays. In the current study, S4-GoNPs synthesized using aqueous JLE had IC50 values of 120.94 and 43.83 µg/mL (Table 6) for both assays, which is comparable to the findings of Bakshi et al. Bakshi et al152 also studied the correlation between both assays and found a positive correlation between the parameters, which was corroborated by the results of our current study (Figure 8A). Furthermore, Poongunran et al153 studied different leaf extracts of S. cumini (hexane, ethyl acetate, methanol, and water) to inhibit α-amylase activity, and found that the methanol and aqueous extracts performed better than the ethyl acetate extract at inhibiting α-amylase (IC50 of 61 and 48.3 µg/mL respectively) at a concentration of 200 μg/mL. These findings support our current results. In another study, Bhavi et al154 have synthesized silver nanoparticles using the aqueous leaf extract of S. cumini and studied its α-amylase inhibition with an IC50 value of 121.21 µg/mL for the nanoparticle and 193.29 µg/mL for the plant extract, which is comparatively higher than IC50 value obtained for the S4-GoNPs (Table 6). Considering the above facts, it can be concluded that S4-GoNPs could serve as useful agents for antidiabetic treatment.

Figure 7.

(A) α – amylase inhibition; (B) α – glucosidase; (C) tyrosinase inhibition; (D) DPPH scavenging; (E) ABTS scavenging and (F) Reducing power potential of S4-GoNPs. Each bar graph with different superscript letters defines statistical significance at P<0.05.

Table 6.

IC50/ IC0.5 Values of Antidiabetic, Tyrosinase Inhibition, and Antioxidant Assays of S4-GoNPs

| Assays | IC50 value (µg/mL) | |

|---|---|---|

| S4-GoNPs | Reference Compounds | |

| α-amylase | 120.94 | 49.80 (acarbose) |

| α-glucosidase | 43.83 | 771.08 (acarbose) |

| Tyrosinase inhibitory activity | 203.57 | 95.38 (Kojic acid) |

| DPPH | 36.25 | 38.07 (Gallic acid) |

| ABTS | 47.51 | 31.79 (Gallic acid) |

| Reducing (IC0.5) | 206.07 | 38.78 (Gallic acid) |

Figure 8.

Regression analysis between (A) α – amylase and α – glucosidase enzyme assay; (B) ABTS and reducing assay; (C) ABTS and DPPH assay and (D) DPPH and Reducing power assay.

The tyrosinase enzyme inhibition potential of S4-GoNPs was investigated by using mushroom melanin-producing tyrosine enzyme and the result is shown in Figure 7C. The S4-GoNPs demonstrated a reasonable tyrosinase inhibition property at three different concentrations (25–100 µg/mL), with a maximum activity of 31.04% at 100 µg/mL, as compared to kojic acid taken as the positive reference control with 52.3% inhibition activity at the same concentration of 100 µg/mL (Figure 7C). The IC50 values of S4-GoNPs and the Kojic acid were found to be 203.57 and 95.38 µg/mL (Table 6). In a study by Lima et al,155 the tyrosinase inhibition activity of ethanolic extracts of S. cumini showed an IC50 of 219.52 µg/mL, which was higher than IC50 shown by S4-GoNPs (Table 6). Melanosomes are the location of melanin formation due to enzymatic reactions involving tyrosine as the substrate and tyrosinase.156 Moreover, irregular melanin coloration in the body can be considered a severe aesthetic issue in humans, especially in middle-aged and elderly folks.156,157 It has been reported that there are many natural bioactive compounds that can inhibit tyrosinase enzymes or hinder or minimize melanin biosynthesis, which are considered useful in biological medicine for cosmetics.156–159 Alam et al160 showed that the hydroxyl groups from phenolic compounds might hinder the enzymatic activity through the formation of hydrogen bonds with the tyrosinase enzyme active site, and some of the tyrosinase inhibitors act by binding their hydroxyl groups to the active site of the enzyme, subsequently leading to steric hindrance. The antioxidant activity could also play a vital role in tyrosinase inhibition activity.160 The tyrosinase inhibitory mechanisms of the phenolic compounds showed that these phenolic compounds are able to act as copper chelators or compounds structurally mimicking the substrate of tyrosinase and can bind to a free enzyme of tyrosinase thereby preventing the substrate binding the enzyme active site.161 Hence, the S4-GoNPs synthesized using JLE rich in natural bioactive compounds such as phenols, acting as a tyrosinase inhibitor, hampering the formation of melanin, and thus could play a major role in skin hyperpigmentation by inhibiting the tyrosinase enzyme.

The antioxidant potential of the S4-GoNPs was investigated using DPPH, ABTS, and reducing power assays (Figure 7D–). The results of the DPPH scavenging assay showed a promising scavenging effect of the S4-GoNPs at 51.65%, 83.47%, and 91.56% at 25 µg/mL, 50 µg/mL, and 100 µg/mL, respectively (Figure 7D), compared to 72.79%, 76.70%, and 77.59% scavenging by the gallic acid used as the referred positive control at the same concentrations (Figure 7D). The IC50 values of S4-GoNPs and the Gallic acid for the DPPH assay were found to be 36.25 and 38.07 µg/mL, respectively (Table 6). Furthermore, the results of the ABTS scavenging assay showed 34.54, 60.91, and 76.59% effects, at 25 µg/mL, 50 µg/mL, and 100 µg/mL by the S4-GoNPs (Figure 7E), respectively, compared to 91.63%, 91.67%, and 91.83% scavenging by the gallic acid taken as the reference-positive control at the same concentrations (Figure 7E). The IC50 values of S4-GoNPs and the Gallic acid for the ABTS assay were found to be 47.51 and 31.79 µg/mL, respectively (Table 6). In the reducing power assay, a positive increase in the OD value of the S4-GoNPs was observed (0.085, 0.131, and 0.177 OD) at 25 µg/mL, 50 µg/mL, and 100 µg/mL, respectively, to 0.656, 0.694, and 0.816 OD values compared to the reference-positive control, gallic acid (Figure 7F). These findings revealed that the antioxidant potential of S4-GoNPs increases at higher concentrations. The IC0.5 values of S4-GoNPs and the Gallic acid for the reducing power assay were found to be 206.07 and 38.78 µg/mL, respectively (Table 6). The low IC50 values of S4-GoNPs demonstrated their strong antioxidant potential compared with the positive control compound. An optimistic trend was observed from the correlation study among the DPPH, ABTS, and reducing power assays with R2 values of 0.826, 0.811, and 0.986, respectively, at 0.05 and 0.01 levels (Table 7), which signifies a strong positive correlation between the parameters (Table 7). To check the association between the antioxidant parameters, linear regression analyses were also performed, which showed a positive trend similar to that of the correlation analysis (Figure 8B–D).

Table 7.

Correlation Analysis of Antioxidant Parameters

| DPPH | ABTS | REDUCING | |

|---|---|---|---|

| DPPH | 1.000 | 0.826** | 0.811** |

| ABTS | 1.000 | 0.986** | |

| REDUCING | 1.000 |

Notes: ** Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed).

Bakshi et al152 studied the antioxidant potential of S. cumini leaf methanol extracts by DPPH, ABTS, and superoxide scavenging assay and have found IC50 values of 42.34, 13.64, and 30.19 µg/mL, respectively, for the three assays. In the current investigation, S4-GoNPs synthesized using the aqueous JLE have the IC50 values of 36.25 and 47.51 µg/mL for DPPH and ABTS activity, respectively (Table 6), which is comparable with the findings of Bakshi et al, since aqueous JLE extract was used in the current case for biosynthesis of S4-GoNPs. In addition, Bakshi et al152 reported a negative correlation (−0.20) between DPPH and ABTS assays, whereas we found a strong positive correlation (0.826) between the parameters (Table 7). In another study, the author evaluated the antioxidant (DPPH) activity of the methanolic extract of S. cumini leaves and reported an IC50 value of 125.39 µg/mL,162 which was much higher than the S4-GoNPs that showed an IC50 value of 36.25 µg/mL (Table 6). The results showed that the S4-GoNPs synthesized using JLE had higher antioxidant potential than the aqueous leaf extracts of S. cumini (JLE in the current case). A study by Eshwarappa et al163 concluded that the high content of total phenolics and flavonoids in the leaf gall extracts of S. cumini is responsible for its high antioxidant activity, which is also corroborated by the current study (Table 6, Figure 7). Phenolic antioxidants are products of secondary metabolism in plants, and the antioxidant activity of these plants is primarily due to their redox potentials, which play a vital role in metal chelation, inhibition of lipoxygenase, and scavenging of free radicals.164 Phenolic compounds are also known to be potential hydrogen donors, making them good antioxidant.165 Oxidative stress can discharge free radicals, such as reactive oxygen species (ROS), networking with cytoplasmic enzymes or DNA that exaggerate or spread the difficulties of some precarious diseases, such as diabetic retinopathy, metastatic cancer, and neuropathy.166 In addition, during biological nanoparticle functions, the ROS released could interfere with the Tumor Necrosis Factor receptors and decrease immune functions, resulting in the induction of cytotoxicity.166 Hence, it is necessary to estimate the generation of free radicals or the shipping capacity of the nanoparticles while assessing their biomedical functions.167 Antioxidant compounds play a major role in the safety machinery of the body against hazardous free radicals. There are reports that number of bioactive compounds such as 2(10)-Pinene; alfa-Copaene;.alpha.-Muurolene;.alpha.-cadinene, etc, present in the JLE have been reported to possess antioxidant potentials.66,67,73,168–174 Thus, the positive effects of S4-GoNPs could be attributed to the utilization of JLE rich in these bioactive compounds, in the bio-reduction and stabilization of nanoparticles, which are rich in a number of bioactive phytocompounds.115 Similar studies on the antioxidant potential of nanoparticles have been recorded.25,166,175

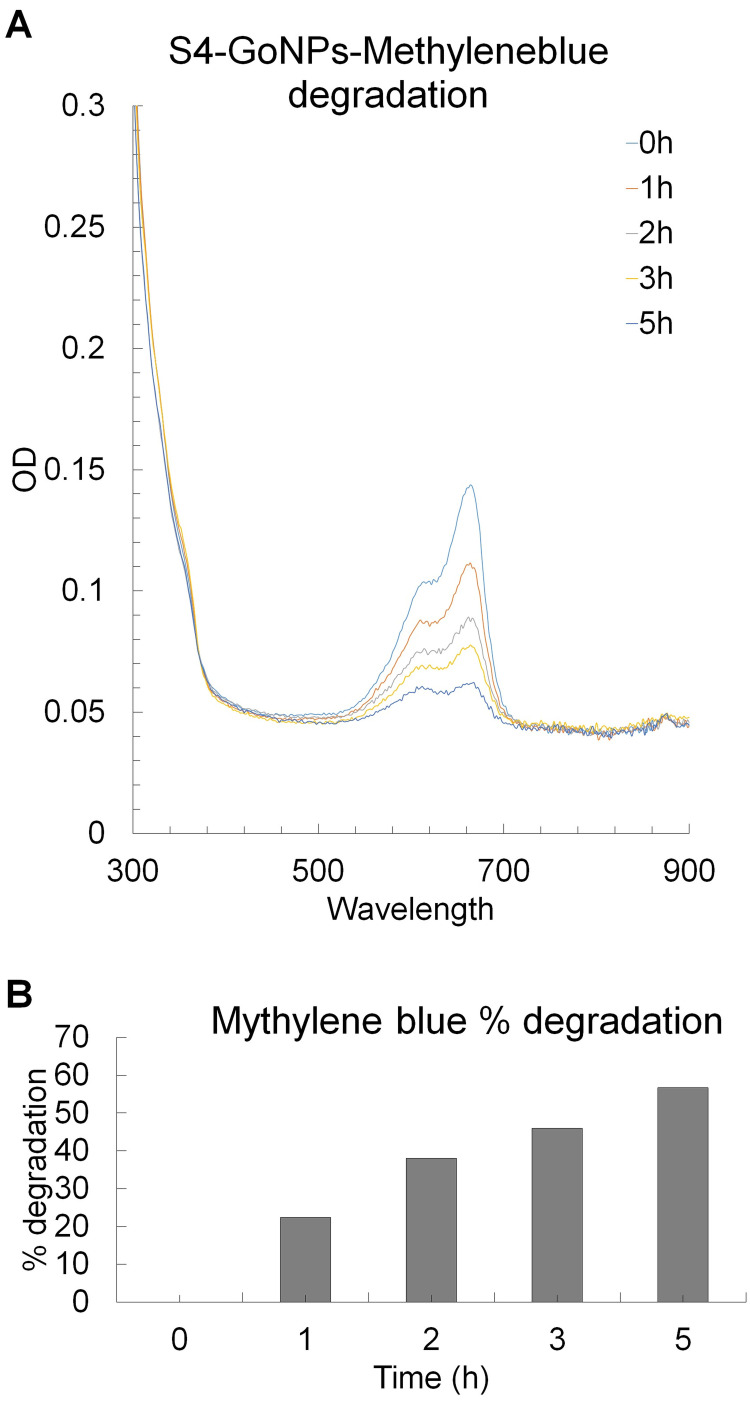

Following the biological potential study of S4-GoNPs, the photocatalytic degradation potential of the industrial cationic dye methylene blue was evaluated to highlight the potential of these nanoparticles to a broader extent (Figure 9A and B). The results revealed that with increased incubation time and exposure to light, the OD value intensity of the dye solution treated with S4-GoNPs was reduced at the absorption maximum peak point of 664 nm (specific to methylene blue dye) (Figure 9A). The OD values of the time-dependent degradation of the methylene blue dye solution were observed under UV light irradiation in the presence of S4-GoNPs. This suggests a discerning interface of cationic dyes with GoNPs and their removal from solution.176 Similarly, a degradation percentage of 56.75% was attained after 5 h of light exposure (Figure 9B), which showed a positive increasing trend with an increase in the incubation period from 0 to 5 h (Figure 9B).

Figure 9.

(A) Photocatalytic degradation of industrial toxic dye methylene blue by S4-GoNPs; (B) Degradation percentage.

A number of studies on the photocatalytic degradation of methylene blue dye by different types of nanoparticles have been reported previously. In a study, Antony M et al177 have reported the methylene blue dye degradation of nearly 80.57% by the gold nanoparticles coated with titanium dioxide nanotubes, after irradiation of sunlight for 240 min. In another study, Rodriguez Leon et al178 showed that around 50% degradation of methylene blue dye was achieved by zeolite-Au nanocomposite in only 11 min in presence of sunlight. Similarly, Mondal et al179 showed a degradation of 32.47% of methylene blue dye by the hydroxyapatite nanoparticles loaded with 0.055 wt% gold. Considering all the above discussions, it can be concluded that the effect of dye degradation depends on a number of factors such as the type of nanomaterials used, the process of light irradiation, and whether any types of combinations are added to the gold nanoparticles. Generally, nanoparticles are considered superlative photocatalysts because of their specific properties, such as stability, low cost, and high photoactive activity and during recent times, there have been more studies on nano adsorption and nano photocatalysis because of their extraordinary surface free energy and precise surface reactivity.180,181 The photocatalytic degradation of industrial dyes usually depends on the surface morphology, shape, and size of metallic nanoparticles.50,182 Moreover, some reports say that spherical nanoparticles demonstrate a superior photocatalytic degradation effect as compared to other forms of nanoparticles,50,183 which is also evident in the current study, where S4-GoNPs with a spherical shape exhibited promising photocatalytic degradation potential. A study by Li et al,184 while investigating the photocatalytic degradation of sphere-like zinc ferrite nanostructures, has demonstrated that when only ZnFe2O4 nanoparticles were used as the catalyst, the photocatalytic degradation was 62.9%; however, when the same amount of ZnFe2O4 nanospheres was added as catalyst, its activity was increased to 100%. Further, the author clarified that since the photocatalytic reaction follows a pseudo-first-order reaction, and the kinetic constant over ZnFe2O4 nanospheres (0.6484 h−1) was 2.93 times higher than that over the ZnFe2O4 nanoparticles (0.2211 h−1), so the ZnFe2O4 nanospheres display much higher photocatalytic degradation activity than the ZnFe2O4 nanoparticles. Thus, in the current study, the enhanced photocatalytic degradation of S4-GoNPs could be attributed to the same principle of spherical shape exhibiting improved activity.

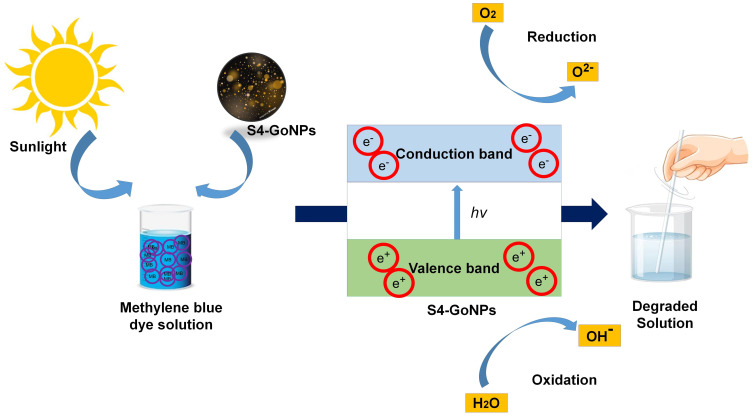

A possible mechanism of the photocatalytic reaction upon exposure to UV light comprises the manufacture of electron–hole pairs and splitting of conduction band electrons and valence band holes on the surface of S4-GoNPs.185,186 A schematic diagram showing the possible mode of action of the methylene blue dye is presented in Figure 10. It is postulated that increasing the charge separation and extending the absorption spectrum of light have resulted in the localized SPR effect that permitted the photocatalytic effect of the nanoparticles thereby degrading the dye.176,187,188 Methylene blue is a phenothiazine derivative used for dyeing textiles and is a highly toxic and carcinogenic dye.189 In a study by Riaz et al,190 the authors investigated the photocatalytic degradation of Congo red and methylene blue dyes using nickel oxide nanoparticles synthesized by the leaf extract of S. cumini and showed that the nanoparticles demonstrated high removal efficiency, which was also observed in our current investigation. Various conventional methods, such as ozonation and adsorption, are typically used for the removal of toxic dyes from wastewater; however, it is impossible to completely eliminate them from wastewater.191,192 Thus, metallic GoNPs can serve as an alternative tool for dye degradation. There are many reports on the photocatalytic degradation of industrial toxic dyes using plant extract-mediated biosynthesized nanoparticles,176,193,194 and the current study also supports these reports.

Figure 10.

A possible mode of action of methylene blue dye degradation by the S4-AuNPs.

Conclusion

Green synthesis of biomediated metal nanoparticles has achieved widespread responsiveness over other conventional methods like chemical and physical methods because of their environment friendly, non-toxic, and cost-effective nature, together with enhanced biocompatibility. Further, the chemical and physical methods utilize large amounts of energy, release toxic and harmful chemicals, and use complex equipment and synthesis conditions. Besides the physical method of nanoparticle synthesis includes aerosols, ultraviolet radiation and thermal decompositions that require very high temperature and pressure. However, this is not the case, in the green synthesis method and it uses a one-pot synthesis process at room temperature and pressure condition and releasing almost no toxic byproducts and thus making it a more adaptable and environmentally friendly method of nanoparticle synthesis. They have also proven to be effective in numerous biological and environmental applications. This study presents an eco-friendly approach for the biomediated green synthesis of S4-GoNPs using jamun leaf aqueous extract (JLE) containing sufficient amounts of phytochemicals such as phenols, tannins, flavonoids, and cardiac glycosides. The S4-GoNPs were characterized using diverse analytical techniques to reveal their morphology, surface behavior, functionalities, and crystallinities. The SPR of the S4-GoNPs was found to be 538 nm with the absorption peak at 2.2 keV, and the average particle size by the particle size analyzer was determined as 120.5 nm with Pdi 0.152 and the zeta potential of −27.6 mV. The S4-GoNPs displayed promising biomedical applications, such as antibacterial effects (with a diameter of zones of inhibition ranging between 11.02 – 14.12 mm), significant antidiabetic properties (40.67% of α-amylase and 91.33% of α-glucosidase enzyme inhibition), positive tyrosinase inhibition and antioxidant effects. In addition, S4-GoNPs also showed potential for photo-mediated toxic industrial dye degradation. The synthesized S4-GoNPs demonstrated improved biological activities, which could be attributed to the synergetic addition of biologically active adsorbed phytochemicals from the JLE, which operates as a reducing, coating, and alleviating agent in the green synthesis method. Its antibacterial, antioxidant, and tyrosinase inhibition potential could be beneficial for the food and cosmetics industries for formulating sunscreen lotions, anti-aging creams, and a number of similar uses. In addition, these nanoparticles could also be explored for antibacterial finishing of medical devices and instruments owing to their positive antibacterial potential. Metallic GoNPs for dye degradation can be utilized in the manufacture of industrial devices for toxic dye degradation. The S4-GoNPs, being synthesized by the green technology method, offer advantages over other types of nanoparticles synthesized using the chemical and physical methods and are very low cost and non-toxic, making them more suitable and have the potential for wider implementation in numerous biomedical research and environmental remediation. Further research on developing cosmetic formulations and drugs related to the displayed biological activities, exploring the scalability of the synthesis process, long-term stability of the nanoparticles, or potential regulatory considerations for their use in consumer products can be explored in future research.

Acknowledgments

All authors are grateful to Dongguk University, Republic of Korea, for their support. We are grateful to all whoever helped in the current research. We acknowledge the freepik.com website for using their images in preparing our schematic diagrams.

Data Sharing Statement

All data related to this manuscript are available in the manuscript as Tables and Figures, and in the supplementary data file.

Disclosure

The authors declare that no conflicts of interest exist with this paper.

References

- 1.Ahamed M, AlSalhi MS, Siddiqui M. Silver nanoparticle applications and human health. Clin Chim Acta. 2010;411(23–24):1841–1848. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2010.08.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Randhwan R, Patil D, Rajurkar S, et al. A novel green synthesis of Syzygium cumini leaves extract coated silver nanoparticles. Chem Sci Rev Lett. 2022;11(44):388–391. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaval U, Hoşgören H. Biosynthesis, characterization, and biomedical applications of gold nanoparticles with Cucurbita moschata Duchesne Ex Poiret peel aqueous extracts. Molecules. 2024;29(5):923. doi: 10.3390/molecules29050923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vijayaraghavan K, Ashokkumar T. Plant-mediated biosynthesis of metallic nanoparticles: a review of literature, factors affecting synthesis, characterization techniques and applications. J Environ Chem Engineer. 2017;5(5):4866–4883. doi: 10.1016/j.jece.2017.09.026 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kessler R. Engineered Nanoparticles in Consumer Products: Understanding a New Ingredient. National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences; 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Singh H, Desimone MF, Pandya S, et al. Revisiting the green synthesis of nanoparticles: uncovering influences of plant extracts as reducing agents for enhanced synthesis efficiency and its biomedical applications. Int J Nanomed. 2023;18:4727–4750. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S419369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vance ME, Kuiken T, Vejerano EP, et al. Nanotechnology in the real world: redeveloping the nanomaterial consumer products inventory. Beilstein J Nanotechnol. 2015;6(1):1769–1780. doi: 10.3762/bjnano.6.181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Prasad R, Swamy VS. Antibacterial activity of silver nanoparticles synthesized by bark extract of Syzygium cumini. J Nanopart Res. 2013;2013:1–6. doi: 10.1155/2013/431218 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ahmad S, Ahmad S, Xu Q, et al. Green synthesis of gold and silver nanoparticles using crude extract of Aconitum violaceum and evaluation of their antibacterial, antioxidant and photocatalytic activities. Frontier Bioengineer Biotechnol. 2023;11:1320739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Manojkumar U, Kaliannan D, Srinivasan V, et al. Green synthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles using Brassica oleracea var. botrytis leaf extract: photocatalytic, antimicrobial and larvicidal activity. Chemosphere. 2023;323:138263. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2023.138263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu M, Xue X, Karmakar B, et al. Sonochemical synthesis of gold nanoparticles mediated by potato starch: its performance in the treatment of esophageal cancer. Open Chem. 2024;22(1):20230193. doi: 10.1515/chem-2023-0193 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chokriwal A, Sharma MM, Singh A. Biological synthesis of nanoparticles using bacteria and their applications. Am J PharmTech Res. 2014;4(6):38–61. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gur T, Meydan I, Seckin H, Bekmezci M, Sen F. Green synthesis, characterization and bioactivity of biogenic zinc oxide nanoparticles. Environ Res. 2022;204:111897. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2021.111897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Muddapur UM, Alshehri S, Ghoneim MM, et al. Plant-based synthesis of gold nanoparticles and theranostic applications: a review. Molecules. 2022;27(4):1391. doi: 10.3390/molecules27041391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]