Abstract

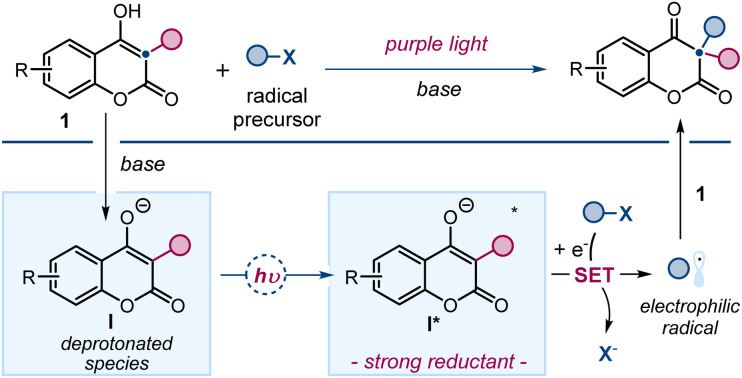

4-Hydroxycoumarins are well-known for their ground-state nucleophilic behavior, which has been widely exploited for their functionalization. Herein, we reveal a previously unexplored photochemical reactivity: upon deprotonation and excitation with purple light, 3-substituted 4-hydroxycoumarins reach an excited state and act as single-electron transfer (SET) reductants, generating radicals from stable substrates. This newfound reactivity enables the direct synthesis of 3,3-disubstituted 2,4-chromandiones via a radical dearomatization process. By enabling the incorporation of alkyl and perfluoroalkyl fragments, this protocol offers a straightforward and mild route to access synthetically valuable chromanone scaffolds featuring a quaternary stereocenter. Comprehensive photophysical studies confirmed that deprotonated 4-hydroxycoumarins are potent SET reductants in their excited state, making them suitable for initiating radical-based transformations.

A photochemical method for synthesizing 3,3-disubstituted 2,4-chromandiones is disclosed. Deprotonated 4-hydroxycoumarins, upon purple-light excitation, act as SET reductants, generating radicals to incorporate alkyl or perfluoroalkyl groups into chromanone scaffolds.

Introduction

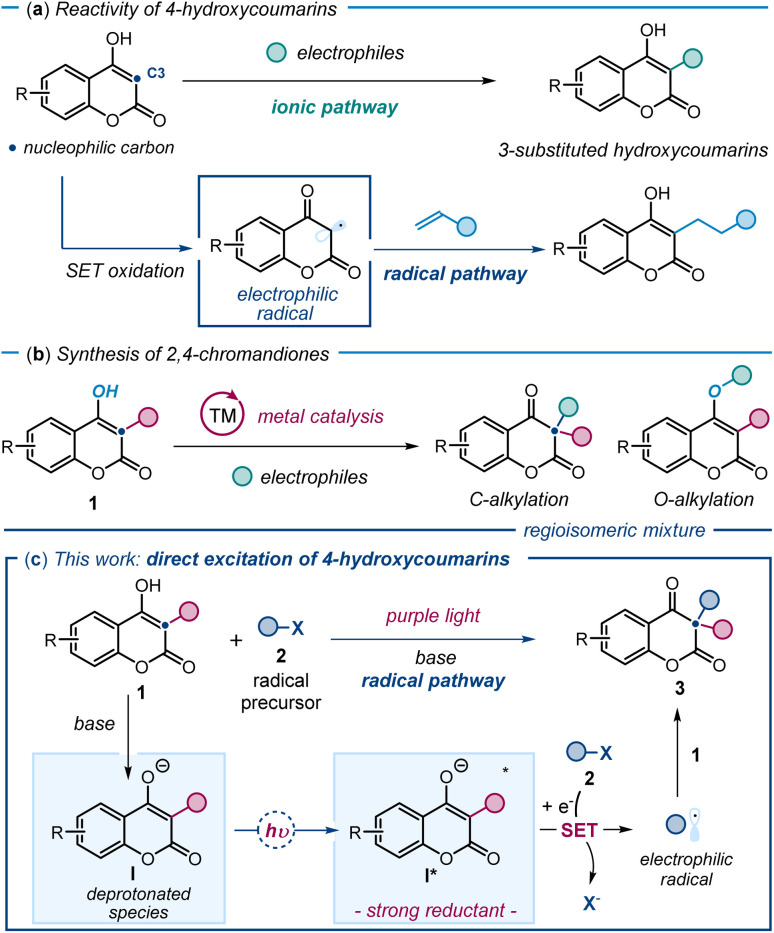

4-Hydroxycoumarins and their derivatives play an important role in medicinal chemistry due to their diverse biological activities.1 Traditionally, the functionalization of 4-hydroxycoumarins has relied on their well-established ground-state nucleophilic ionic reactivity.2a Several catalytic methods have been developed to trap electrophilic intermediates, leading to the formation of 3-substituted hydroxycoumarins (Fig. 1a).2 More recently, a few studies demonstrated that radical pathways could also be useful,3 as a single-electron transfer (SET) oxidation generates electrophilic radicals from 4-hydroxycoumarins, which are subsequently trapped by olefins (Fig. 1a, lower part). In contrast, the direct synthesis of biologically relevant 3,3-disubstituted chromandiones4 through the functionalization of 3-substituted 4-hydroxycoumarins 1 at their carbon 3 has been less investigated (Fig. 1b). Existing methods are predominantly rooted in ionic chemistry, leveraging the nucleophilic nature of 1, and are reliant on transition-metal catalysis.5 These metal-based protocols come with significant drawbacks, including regioselectivity issues, as alkylation often occurs at both the carbon (C3) and oxygen (O) centers of hydroxycoumarins,6 leading to a mixture of products.

Fig. 1. (a) Functionalization of 4-hydroxycoumarins at C3 using traditional ground-state nucleophilic reactivity (upper panel) and an example3a of a radical path via SET oxidation (lower panel). (b) Metal-based methods for the synthesis of 2,4-chromandiones via alkylation of 3-substituted 4-hydroxycoumarins 1 suffer from regioselectivity issues. (c) Our new radical-based strategy, based on the excitation of 3-substituted 4-hydroxycoumarins 1, enables the regioselective synthesis of 3,3-disubstituted 2,4-chromanediones 3. Upon deprotonation and excitation with purple light, I* generates electrophilic radicals that are regioselectively trapped by 1, forging quaternary stereocenters; SET: single-electron transfer.

Herein, we introduce a new playground for hydroxycoumarin chemistry by unveiling the previously untapped photochemical reactivity for 3-substituted 4-hydroxycoumarins 1 (Fig. 1c). We found that, upon deprotonation to afford I and excitation with purple light, 3-substituted 4-hydroxycoumarins 1 reach an excited state (I*) and act as SET reductants, generating radicals from stable substrates 2. The resulting electrophilic radicals are regioselectively intercepted at C3 by the nucleophilic ground-state substrate 1. This novel light-driven reactivity enables the direct synthesis of 3,3-disubstituted chromandiones 3via an overall radical dearomatization process. By incorporating alkyl and perfluoroalkyl groups at the 3-position of hydroxycoumarins, this radical-based approach offers a mild, efficient route to access valuable 2,4-chromandione scaffolds, which have applications in drug discovery.7 The process also forges quaternary stereocenters, which are featured in many biologically relevant compounds.8

Results and discussion

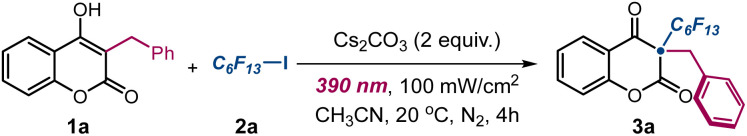

We started out our investigations using 3-benzyl-4-hydroxycoumarin 1a and perfluorohexyl iodide 2a as the radical precursor (Table 1). This choice was informed by our previous studies on the direct excitation of electron-rich compounds,9 including in situ generated enamines,9a-c enolates,9d phenolates,9e and sulfur9f anions, demonstrating that simple light excitation can turn such nucleophilic substrates into strong SET reductants. Given that 4-hydroxycoumarins are inherently nucleophilic, they fit within this photochemical reactivity platform. Moreover, 4-hydroxycoumarin derivatives are known for their absorption in the visible region and unique photophysical properties, including high non-radiative fluorescence.10 However, their excited-state reactivity has not yet been explored in SET-based radical processes.11 As for perfluoalkyl iodides of type 2a, our previous studies9c–e indicated their utility as radical precursors due to their susceptibility to SET activation, leading to the formation of electrophilic perfluoroalkyl radicals upon iodide fragmentation. In addition, the direct incorporation of fluorinated fragments into biologically valuable scaffolds is synthetically relevant, as this modification can enhance pharmacological properties.12

Table 1. Optimization studies and control experimentsa.

| ||

|---|---|---|

| Entry | Deviation | [%] Yield of 3ab |

| 1 | None | 82 |

| 2 | No base, no light | 0 |

| 3 | Under air instead of N2 | 0 |

| 4 | 427 nm or 456 nm light | 0 |

| 5 | Na2CO3 instead of Cs2CO3 | 56 |

| 6 | TMG instead of Cs2CO3 | 78 |

| 7 | 1 equiv. Cs2CO3 | 37 |

Reactions performed over 4 hours in 1 mL of CH3CN using 0.15 mmol of 1a, 0.45 mmol of 2a, and base (2 equiv.) under irradiation by a Kessil lamp (λmax = 390 nm, irradiance = 100 mW cm−2).

Yield of 3a determined by 1H NMR analysis of the crude mixture using dibromomethane as the internal standard.

Our optimization studies were conducted in acetonitrile under irradiation by a purple LED (λmax = 390 nm) at 20 °C in an inert atmosphere (nitrogen). Using Cs2CO3 (2 equiv.) for deprotonation of 4-hydroxycoumarin 1a and 2 equiv. of radical precursor 2a, we obtained the desired perfluoroalkylated 2,4-chromandione product 3a in 82% yield (Table 1, entry 1). Control experiments without light or base completely halted the reaction (entry 2), while an inert atmosphere was essential, as oxygen completely inhibited the reaction (entry 3).

Using visible light illumination at a higher wavelength proved ineffective, as the process was completely halted (entry 4). Replacing Cs2CO3 with Na2CO3 led to product 3a with a moderate yield of 56% (entry 5), while tetramethyl guanidine (TMG) afforded 3a in 78% yield, though not surpassing the efficiency of Cs2CO3 (entry 6). Using only 1 equiv. of Cs2CO3 significantly reduced the yield of 3a to 37%, emphasizing the need for 2 equiv. of base for optimal results (entry 7).

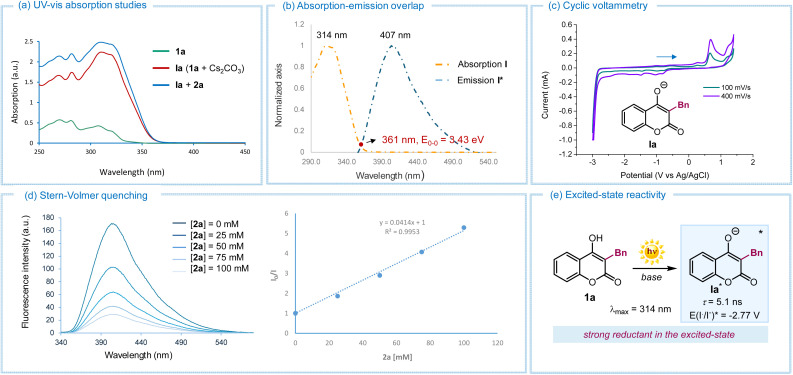

We then carried out investigations to uncover mechanistic insights. UV-visible spectroscopic analysis of 4-hydroxycoumarin 1a (Fig. 2a) showed no absorption in the visible region. However, upon addition of Cs2CO3, a bathochromic shift towards the visible region was observed, indicating that the deprotonated intermediate Ia was the chromophore in our process (red line). Further UV-vis analysis after adding perfluorohexyl iodide 2a excluded the possibility of ground-state aggregation (i.e., no electron donor–acceptor complexes were detected, blue line).13 We then focused on the photophysical behavior of deprotonated hydroxycoumarin Ia, the sole absorbing species at 390 nm, the irradiation wavelength used in this study. Upon laser irradiation at 314 nm of a CH3CN solution of Ia (in situ-generated by mixing 1a with Cs2CO3), emission with a maximum at 407 nm was detected, confirming that Ia could access an electronically excited state (Fig. 2b). The 0–0 transition energy (E0,0) was determined to be 3.43 eV from the cross-section, located at 361 nm of the normalized UV-visible absorption and emission spectra (Fig. 2b). Next, cyclic voltammetry analysis of Ia revealed an irreversible oxidation peak at +0.66 V vs. Ag/AgCl in CH3CN (Fig. 2c). Applying the Rehm–Weller formalism,14 the redox potential of excited Ia (E(Ia˙/Ia*)) was estimated to be −2.77 V vs. SCE, confirming its strong reducing power upon excitation. Stern–Volmer quenching studies (Fig. 2d) showed that the fluorescence of excited Ia, induced by a laser at 310 nm, was effectively quenched by perfluorohexyl iodide 2a. This supported the ability of excited Ia to activate 2avia an SET mechanism. Finally, the excited singlet-state lifetime of Ia* was measured as 5.1 ns by means of single photon counting technique, further confirming its potential for productive excited-state reactivity (Fig. 2e).

Fig. 2. (a) Absorption spectra recorded for 3-benzyl-4-hydroxycoumarin 1a, its deprotonated form Ia (in situ generated from 1a upon addition of Cs2CO3), and their mixture with perfluorohexyl iodide 2a in CH3CN (1 × 10−4 M). (b) Emission of the excited deprotonated intermediate Ia* in CH3CN (in situ generated mixing 1a with Cs2CO3) upon laser irradiation at 314 nm and its intercept at 361 nm with the absorption spectrum, with a 0–0 transition energy (E0,0) determined to be 3.43 eV. (c) Cyclic voltammetry measurement of the deprotonated intermediate Ia carried out in CH3CN vs. Ag/AgCl at a scan rate of 100 and 400 mV s−1. (d) Stern–Volmer luminescence quenching studies of intermediate Ia (1 × 10−4 M in CH3CN) with increasing amounts of perfluorohexyl iodide 2a (excitation at 350 nm; emission was acquired from 360 nm to 440 nm).

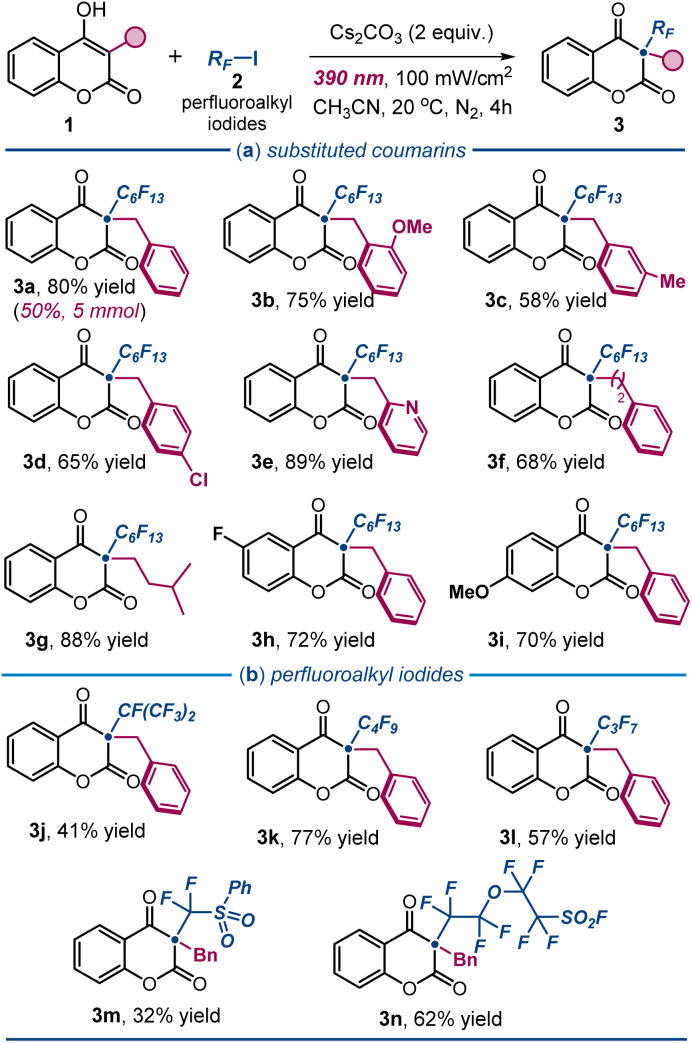

Under the optimal conditions outlined in entry 1 of Table 1, we explored the scope of the photochemical protocol for preparing various 3,3-disubstituted 2,4-chromandiones 3 (Fig. 3). Initially, we demonstrated the process's efficiency on a preparative scale (4 mmol scale), yielding 1.1 g of product 3a (50% yield). We then examined the reactivity of substituted 3-benzyl-4-hydroxycoumarins 1. The protocol tolerated a range of substituents on the aromatic ring of the benzyl moiety. Electron-donating groups at the ortho- and meta-positions were tolerated well (products 3b and 3c). Halogen functionalities, such as a 4-chloro substituent, afforded the desired product 3d in 65% yield. Interestingly, a pyridyl group was also well tolerated, delivering product 3e in high yield. Notably, aliphatic substituents at the 3-position of 1 maintained a productive photochemistry, yielding the corresponding products 3f and 3g in high yields. In contrast, the presence of an aromatic substituent led to a complex mixture, with only traces of the target 2,4-chromandione product. A complete list of unreactive or poorly reactive substrates is reported in Fig. S1 of the ESI.† Variation in the electronic properties of the coumarin ring within 1 was also tolerated: both electron-withdrawing (product 3h) and electron-donating substituents (adduct 3i) afforded the corresponding perfluoroalkylated 2,4-chromandiones in high yields. To evaluate the generality of the method, we reacted 1a with iodides of different perfluoroalkyl chain lengths (Fig. 3b), successfully obtaining products 3j–l in good to high yields. Sensitive iodo sulfonyl fluorides could also be used as radical precursors, enabling the synthesis of the heteroatom-dense products 3m and 3n in moderate to good yields. However, our attempts to use trifluoromethyl iodide as a radical precursor were unsuccessful (see Fig. S1†).

Fig. 3. Photochemical radical synthesis of 2,4-chromandiones 3: survey of the (a) 4-hydroxycoumarin derivatives 1 and (b) perfluoroalkyl iodides 2 that can participate in the process. Reactions performed using 1 (0.2 mmol), 2 (0.6 mmol), Cs2CO3 (2 equiv.) in 1 mL of CH3CN under irradiation by a Kessil lamp (λmax = 390 nm, irradiance = 100 mW cm−2). Yields of the isolated products 3 are reported below each entry; results are averaged from two runs. RF: perfluoroalkyl chain.

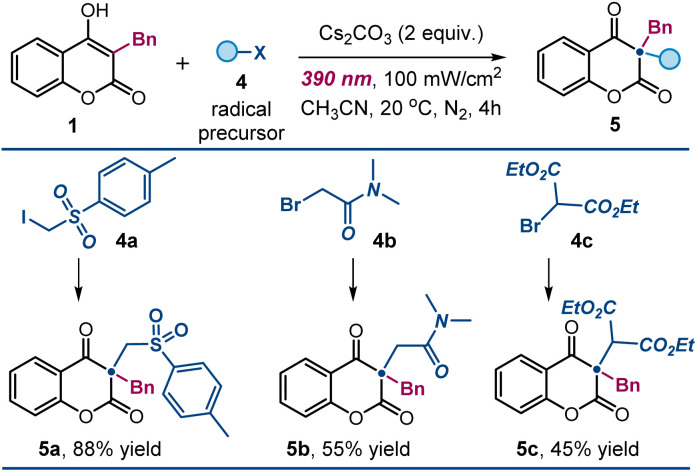

We then considered whether the strong reducing power acquired by the 4-hydroxycoumarins 1 upon excitation could be harnessed to activate radical precursors beyond perfluoroalkyl iodides, thereby expanding the scope of the protocol (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4. Expanding the pool of radical precursors. Reactions performed using 1 (0.2 mmol), 4 (0.6 mmol), Cs2CO3 (2 equiv.) in 1 mL of CH3CN under irradiation by a Kessil lamp (λmax = 390 nm, irradiance = 100 mW cm−2). Yields of the isolated products 5 are reported below each entry; results are averaged from two runs.

We successfully activated (phenylsulfonyl)alkyl iodide 4a, 2-bromo-N,N-dimethylacetamide 4b, and bromomalonate 4cvia SET reduction, generating the corresponding electrophilic carbon-centered radicals. These radicals efficiently reacted with 4-hydroxycoumarins, yielding the desired products 5a–5c in high yields (Fig. 4).

Importantly, in all the experiments reported in this study, we observed complete regioselectivity for C3 functionalization, with no O-alkylated products detected. This suggests that the radical reactivity can bypass regioselectivity issues typically encountered in alternative pathways.

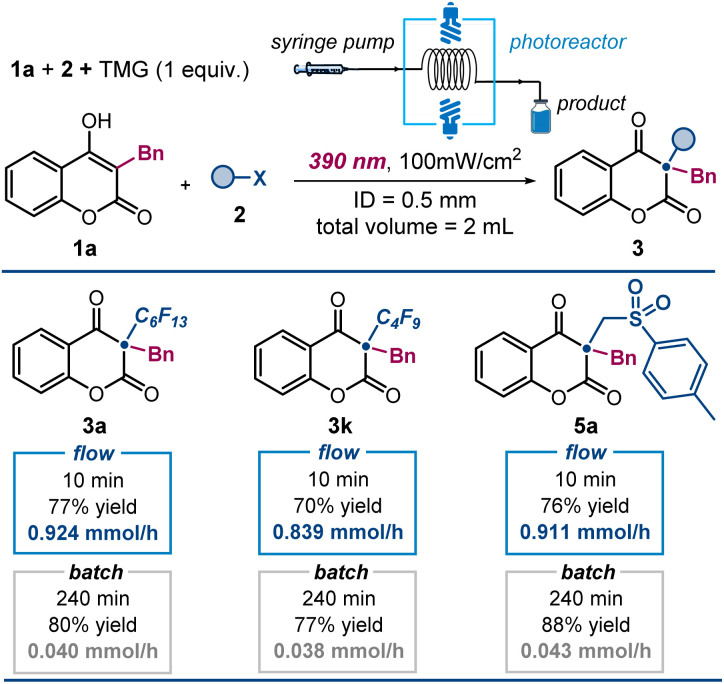

We then assessed the potential to enhance productivity in our photochemical protocol using flow photochemistry (Fig. 5).15 This method offers benefits like improved light exposure and controlled residence time, resulting in more efficient and consistent reactions. We used a 3D-printed flow reactor with a 0.5 mm inner diameter and a total volume of 2 mL, connected to a syringe pump for precise flow rate control (see Section F in the ESI† for details). Irradiation was performed with a Kessil LED light source (λmax = 390 nm), consistent with our batch experiments. Using 1 equivalent of TMG as a soluble organic base, we achieved complete alkylation of 4-hydroxycoumarins in just 10 minutes, significantly reducing reaction time compared to batch reactions. High yields of alkylated products 3a, 3k, and 5a were obtained with improved productivity. For comparison, a batch reaction afforded product 3a in 80% yield after 240 minutes, while the flow system yielded 3a in 10 minutes, using half the amount of base. The flow system achieved a productivity of 0.924 mmol h−1, a 23-fold enhancement over the batch process's productivity of 0.04 mmol h−1. These results underscore the advantages of flow photochemistry in terms of speed, efficiency, and scalability.

Fig. 5. Flow photocatalysis for improved productivity. Reactions performed using 1 (0.2 mmol), 2 (0.6 mmol), TMG (1 equiv.) in 2 mL of CH3CN under illumination by two single wavelength Kessil LED (λmax = 390 nm, irradiance = 100 mW cm−2) inside a photoreactor. Yields of the isolated products 3 are reported below each entry. ID: inner diameter. Conditions for batch reactions are detailed in Fig. 3 (4 hours reaction time, using 2 equiv. of Cs2CO3).

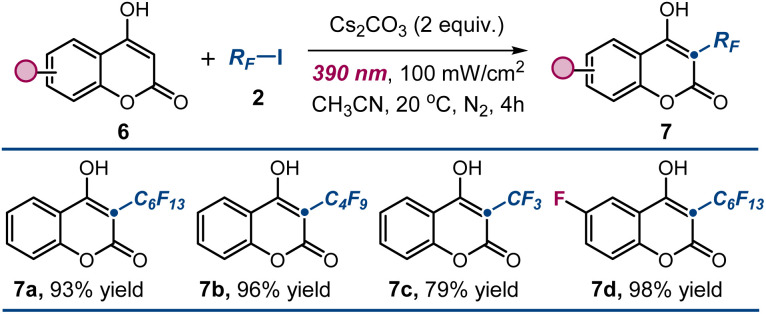

Finally, we surmised that our protocol could be extended to achieve alkylation at the C3 position of unsubstituted 4-hydroxycoumarins 6 by trapping electrophilic radicals generated through photoexcitation. This approach could complement existing ionic methods2 for synthesizing 3-substituted 4-hydroxycoumarins 7 by expanding the reaction scope to include radical pathways.3 As illustrated in Fig. 6, we successfully applied the optimized conditions to the radical perfluoroalkylation of unsubstituted 4-hydroxycoumarins 6, demonstrating that also these substrates exhibit productive photochemistry when irradiated with purple light. This enabled the generation of electrophilic radicals from a variety of stable halide precursors, including trifluoromethyl iodide, which was unreactive in our previous studies with 3-substituted 4-hydroxycoumarins (adduct 7c). The corresponding perfluoroalkylated products 7a–d were obtained with high efficiency, highlighting the versatility of our methodology.

Fig. 6. Extending the photochemistry to unsubstituted 4-hydroxycoumarins. Reactions performed using 6 (0.2 mmol), 7 (0.6 mmol), Cs2CO3 (2 equiv.) in 1 mL of CH3CN under illumination by a single Kessil lamp (λmax = 390 nm, irradiance = 100 mW cm−2). Yields of the isolated products 7 are reported below each entry. RF: perfluoroalkyl chain.

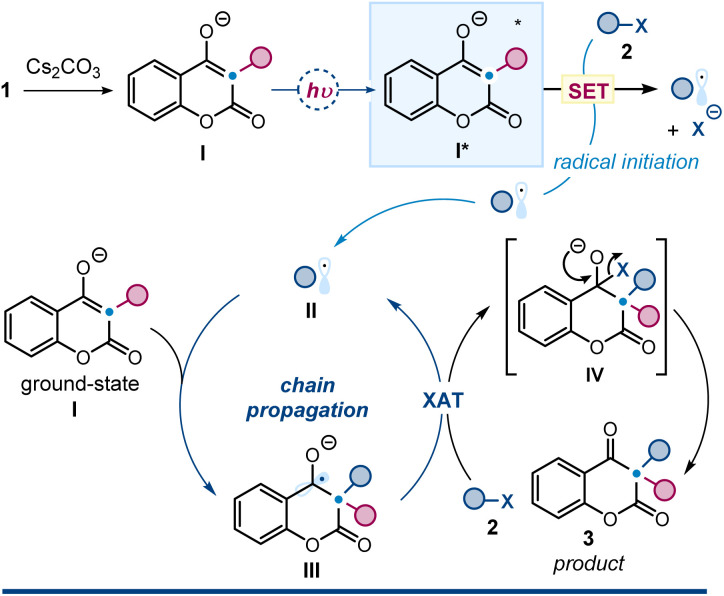

Lastly, we conducted further investigations to elucidate the mechanism. Specifically, we determined the quantum yield (Φ) of the photochemical reaction between 1a and 2a, which was 8.4, strongly supporting a radical chain mechanism.16 Based on this finding, alongside the photophysical studies and control experiments reported in Fig. 2 and Table 1, we propose the mechanism depicted in Fig. 7, where radical propagation is responsible for product formation.

Fig. 7. Proposed mechanism.

The process begins with the deprotonation of 3-subtituted 4-hydroxycoumarin 1, facilitated by Cs2CO3, followed by excitation of intermediate I under purple light (390 nm). The resulting excited intermediate I* acts as a strong SET reductant (E(I˙/[I*]) = −2.77 V), capable of activating alkyl iodides. Mesolytic cleavage of the carbon–iodine bond then generates an electrophilic radical II. This step represents the light-driven initiation of the chain process. This electrophilic radical is intercepted by the ground-state nucleophilic 3-substituted 4-hydroxycoumarin 1, forming a nucleophilic ketyl radical intermediate III. This intermediate abstract a halogen atom from the radical precursor 2via a halogen atom transfer (XAT)17 mechanism, generating intermediate IV (ref. 18) while affording radical II, thus propagating the chain. Finally, intermediate IV collapses to yield product 3. The overall mechanism fits within the framework of an atom-transfer radical addition (ATRA) process.19

Conclusions

In summary, we have developed a photochemical radical-based method for the dearomatization of 4-hydroxycoumarin derivatives, enabling efficient introduction of fluoroalkyl and alkyl substituents at C3. This strategy leverages the unique excited-state reactivity of hydroxycoumarins, which act as strong SET reductants under purple light irradiation, driving radical formation. This new reactivity expands the functionalization possibilities of biologically relevant hydroxycoumarins and provides direct access to 2,4-chromandiones with quaternary stereogenic centers.

Data availability

All experimental data are provided in the ESI.†

Author contributions

S. M., E. S., and H. W. performed the experiments. S. M. conceptualized the project. P. M. directed the project. P. M. wrote the manuscript with assistance from all authors.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts to declare.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Financial support was provided by project PRINPNRR ‘LIGHT CAT’ P2022RHMCM, supported by the European Commission – NextGeneration EU program – M4C2. S. M. thanks the EU for a Horizon 2021 Marie Skłodowska–Curie Fellowship (HORIZON-MSCA-2021-PF-01, 101062360), while H. W. thanks the China Scholarship Council for a predoctoral fellowship (CSC202208350011). Prof. Isacco Gualandi and Dr Giada D'Altri are acknowledged for their support with cyclic voltammetry experiments.

Electronic supplementary information (ESI) available: Details of experimental procedures, full characterization data, and copies of NMR spectra. See DOI: https://doi.org/10.1039/d4sc07495e

References

- (a) Bauer J. Koeberle A. Dehm F. Pollastro F. Appendino G. Northoff H. Rossi A. Sautebin L. Werz O. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2011;81:259. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2010.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Emami S. Dadashpour S. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2015;102:611. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2015.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Menichelli D. Poli D. Antonucci E. Cammisotto V. Testa S. Pignatelli P. Palareti G. Pastori D. Molecules. 2021;26:1425. doi: 10.3390/molecules26051425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Carneiro A. Matos M. J. Uriarte E. Santana L. Molecules. 2021;26:501. doi: 10.3390/molecules26020501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Zhou R. Yu Y. H. Kim H. Ha H.-H. Sci. Rep. 2022;12:21635. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-26212-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For selected reviews: ; (a) Abdou M. M. El-Saeed R. A. Bondock S. Arabian J. Chem. 2019;12:88. doi: 10.1016/j.arabjc.2015.06.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; (b) Abdou M. M. El-Saeed R. A. Bondock S. Arabian J. Chem. 2019;12:974. doi: 10.1016/j.arabjc.2015.06.029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; (c) Cortés I. Cala L. J. Bracca A. B. J. Kaufman T. S. RSC Adv. 2020;10:33344. doi: 10.1039/D0RA06930B. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For the few radical functionalization protocols of unsubstituted 4-hydroxycoumarins reported so far, see: ; (a) Chang R. Pang Y. Ye J. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2023;62:e202309897. doi: 10.1002/anie.202309897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Lapcinska S. Dimitrijevs P. Arsenyan P. J. Org. Chem. 2022;87:15261. doi: 10.1021/acs.joc.2c01803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appendino G. Nano G. M. Viterbo D. De Munno G. Cisero M. Palmisano G. Aragno M. Helv. Chim. Acta. 1991;74:495. doi: 10.1002/hlca.19910740305. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- For selected examples, see: ; (a) Asahi K. Nishino H. Heterocycl. Commun. 2008;14:21. [Google Scholar]; (b) Chaudhari M. B. Moorthy S. Patil S. Bisht G. S. Mohamed H. Basu S. Gnanaprakasam B. J. Org. Chem. 2018;83:1358. doi: 10.1021/acs.joc.7b02854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (a) Cravotto G. Mario Nano G. Palmisano G. Tagliapietra S. Heterocycles. 2003;60:1351. doi: 10.3987/COM-03-9737. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; (b) Majumdar K. C. Basu P. K. Mukhopadhyay P. P. Sarkar S. Ghosh S. K. Biswas P. Tetrahedron. 2003;59:2151. doi: 10.1016/S0040-4020(03)00182-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; (c) Garro Hugo A. Manzur Jimena M. Ciuffo Gladys M. Tonn Carlos E. Pungitore Carlos R. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2014;24:760. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2013.12.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appendino G. Nano G. M. Viterbo D. De Munno G. Cisero M. Palmisano G. Aragno M. Helv. Chim. Acta. 1991;74:495. doi: 10.1002/hlca.19910740305. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (a) Kelley A. M. Haywood R. D. White J. C. Petersen K. S. ChemistrySelect. 2020;5:3018. doi: 10.1002/slct.202000312. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; (b) Quasdorf K. W. Overman L. E. Nature. 2014;516:181. doi: 10.1038/nature14007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (a) Silvi M. Arceo E. Jurberg I. D. Cassani C. Melchiorre P. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015;137:6120. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b01662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Filippini G. Silvi M. Melchiorre P. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2017;56:4447. doi: 10.1002/anie.201612045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Balletti M. Wachsmuth T. Di Sabato A. Hartley W. C. Melchiorre P. Chem. Sci. 2023;14:4923. doi: 10.1039/D3SC01347B. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Woźniak Ł. Murphy J. J. Melchiorre P. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015;137:5678. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b03243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Filippini G. Nappi M. Melchiorre P. Tetrahedron. 2015;71:4535. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2015.02.034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; (f) Shuo W. Melchiorre P. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2024;63:e202407520. doi: 10.1002/anie.202407520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (a) Bečić E. Šober M. Imamović B. Završnik D. Špirtović-Halilović S. Pigm. Resin Technol. 2011;40:292. doi: 10.1108/03699421111176199. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; (b) Al-Majedy Y. K. Al-Amiery A. A. Amir A. Kadhum H. Mohamad A. B. Am. J. Chem. 2015;5:48. [Google Scholar]

- A few examples of [2+2] photocycloadditions of 4-hydroxycoumarins, proceeding from the triplet excited state, have been reported, see Scheme 5e in Ref. 3a and: ; Haywood D. J. Hunt R. G. Potter C. J. Reid S. T. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1977;1:2458. doi: 10.1039/P19770002458. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (a) Müller K. Faeh C. Diederich F. Science. 2007;317:1881. doi: 10.1126/science.1131943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Meanwell N. A. J. Med. Chem. 2018;61:5822–5880. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.7b01788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crisenza G. E. M. Mazzarella D. Melchiorre P. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020;142:5461. doi: 10.1021/jacs.0c01416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farid S. Dinnocenzo J. P. Merkel P. B. Young R. H. Shukla D. Guirado G. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:11580. doi: 10.1021/ja2024367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buglioni L. Raymenants F. Slattery A. Zondag S. D. A. Noël T. Chem. Rev. 2022;122:2752. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.1c00332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (a) Buzzetti L. Crisenza G. E. M. Melchiorre P. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2019;58:3730. doi: 10.1002/anie.201809984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Cismesia M. A. Yoon T. P. Chem. Sci. 2015;6:5426. doi: 10.1039/C5SC02185E. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juliá F. Constantin T. Leonori D. Chem. Rev. 2022;122:2292. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.1c00558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Similar atom-transfer mechanisms have been invoked for the alkylation of enol ethers and enamides with electrophilic radicals; see: ; (a) Curran D. P. Ko S.-B. Tetrahedron Lett. 1998;39:6629. doi: 10.1016/S0040-4039(98)01405-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; (b1) Friestad G. K. Wu Y. Org. Lett. 2009;11:819. doi: 10.1021/ol8028077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; See also:; (c) Studer A. Curran D. P. However, an SET process that reduces substrate 2 from the ketyl radical intermediate III and regenerates the chain-propagating radical II cannot be excluded. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016;55:58. doi: 10.1002/anie.201505090. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pintauer T. and Matyjaszewski K., in Encyclopedia of Radicals, Wiley, 2012, vol. 4, pp. 1851–1894 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All experimental data are provided in the ESI.†