Abstract

We have constructed a series of simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) mutants containing deletions within a 97-nucleotide (nt) region of the leader sequence. Deletions in this region markedly decreased the replication capacity in tissue culture, i.e., in both the C8166 and CEMx174 cell lines, as well as in rhesus macaque peripheral blood mononuclear cells. In addition, these deletions adversely affected the packaging of viral genomic RNA into virions, the processing of Gag precursor proteins, and patterns of viral proteins in virions, as assessed by biochemical labeling and polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Different levels of attenuation were achieved by varying the size and position of deletions within this 97-nt region, and among a series of constructs that were generated, it was possible to rank in vitro virulence relative to that of wild-type virus. In all of these cases, the most severe impact on viral replication was observed when the deletions that were made were located at the 3′ rather than 5′ end of the leader region. The potential of viral reversion over protracted periods was investigated by repeated viral passage in CEMx174 cells. The results showed that several of these constructs showed no signs of reversion after more than 6 months in tissue culture. Thus, a series of novel, attenuated SIV constructs have been developed that are significantly impaired in replication capacity yet retain all viral genes. One of these viruses, termed SD4, may be appropriate for study with rhesus macaques, in order to determine whether reversions will occur in vivo and to further study this virus as a candidate for attenuated vaccination.

Simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) is a primate lentivirus closely related to human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) (14, 21, 35, 38, 41). Highly attenuated strains of SIV containing deletions in nonessential genes have been shown to elicit strong protection against pathogenic challenge in primate models (1, 7, 9, 13, 43). Although live attenuated nef-deleted viruses have protected monkeys against challenge with wild-type viruses, this type of vaccine is considered unacceptable because of reversions and safety concerns (18, 38). For example, multiply deleted SIV strains have been shown to be pathogenic in neonatal macaques (2, 3). Notably, as well, these mutants are able to replicate in permissive cell lines (15, 34). Although the relationship between viral replication capacity and pathogenesis is not always clear, high plasma viral load is strongly correlated with disease progression in the case of HIV-1 (33).

Extensive studies have shown that leader sequences within the HIV-1 genome, between the primer binding site and the major splice donor site, play a critical role in various aspects of viral replication, including packaging of viral genomic RNA, Gag protein processing, reverse transcription, and gene expression (20, 22, 24, 26, 28, 29). HIV mutants containing deletions in this region are highly attenuated in ability to grow in permissive cell lines, yet retain the ability to synthesize all viral proteins. Recent work has also revealed a similar role for the leader sequences in SIV (17).

Deletion of select areas of the leader sequences in HIV and SIV may conceivably represent a good vaccine strategy. To further study this topic, we have constructed a series of mutated SIV variants containing deletions in this region. These mutated SIV strains displayed similar patterns of impairment in both permissive cell lines and in monkey peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs), and certain of these viruses are stable in tissue culture for periods of 6 months to 1 year, with no sign that reversions or compensatory mutations have occurred. Animal trials of these novel, live attenuated viruses will be needed to delineate relationships between replication capacity and pathogenesis and to establish potential protective capacity and correlates of immunity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Construction of deletion mutants.

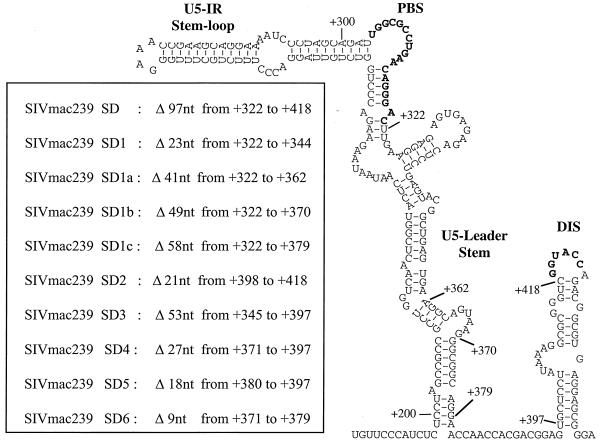

The full-length infectious clone of SIV, SIVmac239/WT (17, 23), was used to construct deletion mutants. We used a PCR-based mutagenesis method to generate deletions downstream of the primer binding site; Pfu polymerase was used to increase the fidelity of the PCR. Briefly, the region between the NarI and BamHI sites in SIVmac239/WT was replaced with PCR fragments to generate mutant constructs. Figure 1 graphically illustrates the mutants generated. Primers pSD1a/pSgag1 were used for the SD1a deletion, and primers pSD1b/pSgag1 and pSD1c/pSgag1 were used for SD1b and SD1c, respectively. For construction of the SD4, SD5, and SD6 deletions, PCR fragments (pSD4/pSgag1, pSD5/pSgag1, and pSD6/pSgag1 for SD4, SD5, and SD5, respectively) were purified and were then used as mega-primers paired with primer pSU5. The resulting PCR fragments were then used to replace the region between NarI and BamHI sites in SIVmac239/WT. The construction of the SD, SD1, SD2, and SD3 mutants has been described previously (17), and the sequences of novel primers used in the present work are as follows: pSD1a, 5′-GATTGGCGCCTGAACAGGGAC/GCAGTAAGGGCGGCAGG-3′ (+301 to +321/+363 to +379); pSD1b, 5′-GATTGGCGCCTGAACAGGGAC/GG CGGCAGGAACCAACC-3′ (+301 to +321/+371 to +387); pSD1c, 5′-GATTGGCGCCTGAACAGGGAC/AACCAACCACGACGGAG-3′ (+301 to +321/+380 to +396); pSD4, 5′-CTGAGTGAAGGCAGTAAG/GCTCCTATAAAGGCGCGGGC-3′ (+353 to +370/+398 to +418); pSD5, 5′-GCAGTAAGGGCGGCAGG/GCTCCTATAAAGGCGCGGGTC-3′ (+363 to +379/+398 to +418); and pSD6, 5′-CGGCTGAGTGAAGGCAGTAAG/AACCAACCACGACGGAG-3′ (+350 to +370/+380 to +396). Other primers used in this work have been described previously (17). The validity of all constructs was confirmed by sequencing. Nucleotide designations are based on published sequences; the transcription initiation site corresponds to position +1 (23).

FIG. 1.

Illustration of the deletion constructs used in this study. Secondary structures of the U5-leader stem and the putative DIS stem-loop of SIVmac239 leader RNA are shown. The positions of deletion constructs are relative to the transcription initiation site and are shown next to the RNA structure. These positions are also indicated in the diagram of secondary structure. Both the primer binding site (PBS) and the DIS palindrome sequences are highlighted.

Cells and preparation of virus stocks.

COS-7 cells and 293T cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum. C8166 cells and CEMx174 cells (39) were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum. Monkey PBMCs were isolated from the blood of healthy rhesus macaques and were stimulated with phytohemagglutinin for 3 days and then maintained in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum and 20 U of interleukin 2 per ml. All media and sera were purchased from GIBCO (Burlington, Ontario, Canada). Molecular constructs were purified with a Maxi Plasmid kit (Qiagen, Inc., Mississauga, Ontario, Canada). Both COS-7 and 293T cells were transfected with the constructs described above by using Lipofectamine-Plus reagent (GIBCO). Virus-containing culture fluids were harvested at 60 h after transfection and were clarified by centrifugation for 30 min at 4°C at 3,000 rpm in a Beckman GS-6R centrifuge. Viral stocks were passed through a 0.2-μm-pore-diameter filter and stored in 0.5- or 1-ml aliquots at −70°C. The concentration of p27 antigen in these stocks was quantified with a Coulter SIV core antigen assay kit (Immunotech, Inc., Westbrook, Maine).

Virus replication.

Viral stocks were thawed and treated with 100 U of DNase I in the presence of 10 mM MgCl2 at 37°C for 1 h to eliminate any residual contaminating plasmids from the transfection. Infection of C8166 cells or CEMx174 cells was generally performed by incubating 106 cells at 37°C for 2 h with an amount of virus equivalent to 10 ng of p27 antigen (for exceptions, see figure legends). Infected cells were then washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline and resuspended in fresh medium. Cells were split at a 1:3 ratio twice per week if they had grown to a sufficient level; otherwise, the culture fluid was replaced with fresh medium. Supernatants were monitored for virus production by reverse transcriptase (RT) assay. Virus infectivity (50% tissue culture infective dose [TCID50]) was determined by infection of CEMx174 cells as described previously (11). The sMAGI assay was also performed to determine the infectivity of mutated and wild-type viruses as described previously (5).

Virus replication was also performed in primary rhesus monkey PBMCs. Activated PBMCs (5 × 106) were infected with SIV stocks containing 10 ng of p27 at 37°C for 2 h; the cells were then washed extensively to remove any remaining virus. Cells were maintained in 10 ml of culture medium as described above. Virus production in culture fluids was monitored by SIV p27 antigen capture assay by using the Coulter SIV core antigen capture kit.

Analysis of viral proteins by radiolabeling and immunoprecipitation.

In order to radiolabel viral proteins, 293T cells were transfected with wild-type or mutant constructs. After 20 h, cells were starved at 37°C for 30 min in DMEM without methionine or cysteine. Radiolabeling was performed with [35S]Met and [35S]Cys at a concentration of 100 μCi/ml for 30 min at 37°C. Then, the cells were thoroughly washed with complete DMEM and cultured for 1 h. Culture fluids were collected and clarified with a Beckman GS-6R bench centrifuge at 3,000 rpm for 30 min at 4°C. Viral particles were further purified through a 20% sucrose cushion at 40,000 rpm for 1 h at 4°C with an SW41 rotor in a Beckman L8-M ultracentrifuge. Virus pellets were suspended in 1× sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) loading buffer (31), boiled for 5 min, and then fractionated by SDS-PAGE (12% polyacrylamide) and exposed to X-ray film. The labeled cells were washed twice with cold phosphate-buffered saline and lysed in buffer containing 0.1% NP-40. Cell lysates were incubated with a monoclonal antibody (MAb) directed against SIV p27 at 4°C for 30 min, and the resultant antigen-antibody complexes were precipitated by a 30-min incubation with protein A-Sepharose CL-4B (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Montreal, Quebec, Canada). Recovered viral proteins were analyzed by SDS-PAGE (12% polyacrylamide) and exposed to X-ray film (31).

Packaging of viral genomic RNA.

Viral RNA was isolated with the QIAamp viral RNA mini kit (Qiagen) from equivalent amounts of COS-7 cell-derived viral preparations based on levels of SIV p27 antigen. RNA samples were treated with RNase-free DNase I at 37°C for 30 min to eliminate possible DNA contamination. DNase I was then inactivated by incubation at 75°C for 10 min. The viral RNA samples were quantified by RT-PCR with the Titan One Tube RT-PCR system (Boehringer Mannheim, Inc., Montreal, Quebec, Canada) as described previously (17). Relative amounts of products were quantified by molecular imaging (Bio-Rad, Toronto, Ontario, Canada). Levels of genomic RNA packaging were calculated on the basis of four independent experiments, with wild-type viral values arbitrarily set at 1.0.

RESULTS

A short nucleotide sequence downstream of the primer binding site plays a key role in SIV replication.

We previously constructed four SIV mutants (SD, SD1, SD2, and SD3) containing large deletions within a 97-nucleotide (nt) region downstream of the primer binding site. Each of these deletions resulted in impaired viral replication in C8166 cells, and yet, in one case, compensatory mutations and restored viral replication capacity were observed over time (17). To further investigate the possibility of establishing attenuated strains that would be more permanently attenuated and to further assess which sequences were responsible for impaired virus replication, we generated six additional deletion constructs (Fig. 1). The original SD1 deletion of 22 nt at positions +322 to + 344 had little long-term impact on virus replication, so we extended the deletion to lengths of 41, 49, and 58 nt, i.e., constructs SD1a (+322 to +362), SD1b (+322 to +370), and SD1c (+322 to +379), respectively (Fig. 1). RNA secondary structure analysis indicated that a nucleotide stretch downstream of the primer binding site can form a stem with an upstream sequence (i.e., the U5-leader stem) (37). A sequence homology search for a binding site for a regulatory factor revealed sequences with high homology to the SP1 binding site at positions +370 to +397 in SIV (data not shown). Accordingly, we generated the deletion mutants, termed SD4 (+371 to +397), SD5 (+380 to +397), and SD6 (+371 to +379) (Fig. 1) and studied the effect of these deletions on virus replication. The results in Fig. 2A show that both the SD1a and SD1b viruses were partially impaired, while each of the SD1c, SD4, SD5, and SD6 viruses was severely impaired in ability to replicate in C8166 cells. The SD6 construct retains the 5′ portion of the exact sequence that was deleted in SD1c, but not in SD1a or SD1b. These findings suggest that the deletion of as few as 9 nt at positions +371 to +379 contributed to severely impaired virus replication. The fact that the extent of impairment of SD5 was similar to that of SD3, SD1c, and SD suggests that the sequences at positions +380 to +397 (i.e., between the U5-leader stem and the DIS stem-loop) are also important in this regard.

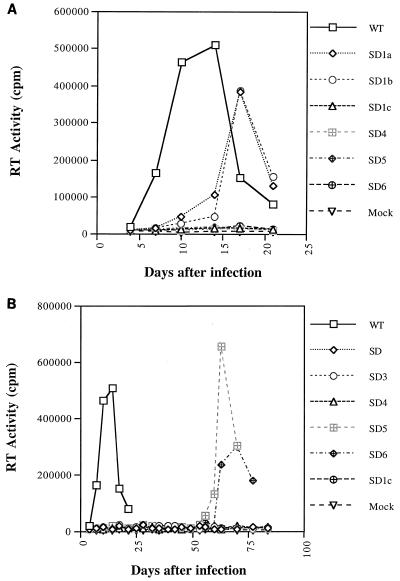

FIG. 2.

Replication capacity of mutated viruses in C8166 cells. (A) Equivalent amounts of virus from COS-7-transfected cells were used to infect C8166 cells based on levels of p27 antigen (10 ng per 106 cells). Viral replication was monitored by RT assay of culture fluids. Mock transfection denotes exposure of cells to heat-inactivated wild-type (WT) virus as a negative control. (B) Replication capacity of mutated viruses during long-term tissue culture in C8166 cells.

We have previously shown that long-term culture of cells infected by the SD2 virus resulted in reversions (17). However, maintenance of cells infected by the SD4, SD5, SD6, and SD1c viruses revealed that the SD4 and SD1c viruses appeared to be stably impaired (Fig. 2B). In contrast, the SD5 and SD6 viruses achieved higher levels of viral replication after 9 to 10 weeks.

Replication of deleted viruses in CEMx174 cells.

The B/T hybrid cell line known as CEMx174 lends itself well to the replication of SIV (39). The results of Fig. 3A show that the SD1 mutants replicated in these cells with kinetics similar to those of wild-type viruses. Although both SD1a and SD1b were partially impaired, this occurred to a lesser degree than in the C8166 cells. SD2, SD5, and SD6 displayed moderately delayed growth, but still replicated faster in CEMx174 cells than in the C8166 line. And, as with C8166 cells, the SD, SD3, SD1c, and SD4 mutants were severely impaired in ability to grow in the CEMx174 cell line.

FIG. 3.

Replication capacity of mutated viruses in CEMx174 cells. (A) Equivalent amounts of virus from COS-7-transfected cells were used to infect CEMx174 cells based on levels of p27 antigen (10 ng per 106 cells). Viral replication was monitored by RT assay of culture fluids. Mock infection denotes exposure of cells to heat-inactivated wild-type (WT) virus as a negative control. (B) Replication capacity of mutated viruses during long-term tissue culture.

The long-term culture of infected CEMx174 cells showed that SD4 viruses attained peak levels of RT activity at 6 weeks postinfection (Fig. 3B), while the SD, SD1c, and SD3 viruses did not show any signs of reversion after 6 months. The combined results of infections in C8166 and CEMx174 cells show that the SD2, SD5, and SD6 viruses are attenuated to an extent that is tolerated by both cell lines, while SD4 is a highly attenuated virus that can grow marginally in CEMx174 cells, but not in C8166 cells.

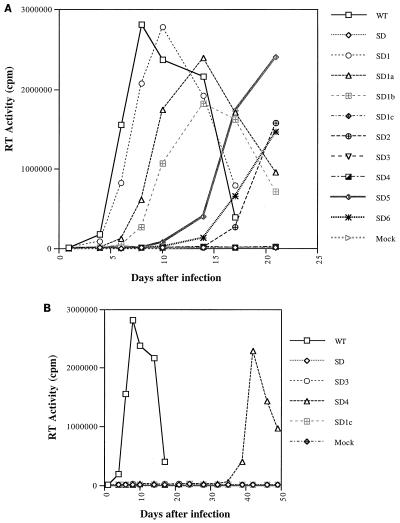

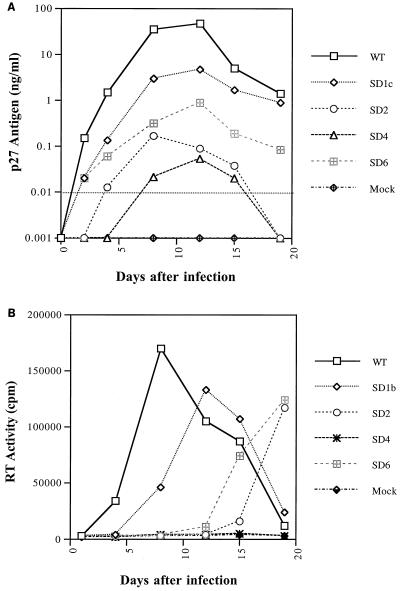

The potential for viral reversion over protracted periods was also investigated with CEMx174 cells. Viruses from the peaks of RT activity in the initial infection were used to infect fresh cells. The replication kinetics of these second-passage viruses are shown in Fig. 4. All of the passaged viruses still showed impaired replication kinetics compared to wild-type virus. The results of PCR and sequencing confirmed that all of these viruses retained their original deletions (data not shown).

FIG. 4.

Replication capacity of mutated virus during the second passage in CEMx174 cells. CEMx174 cells were infected with equivalent amounts of virus from the peak time of RT production after initial infection based on levels of p27 antigen (10 ng per 106 cells). Viral replication was monitored by RT assay of culture fluids. Mock infection denotes exposure of cells to heat-inactivated wild-type (WT) virus as a negative control.

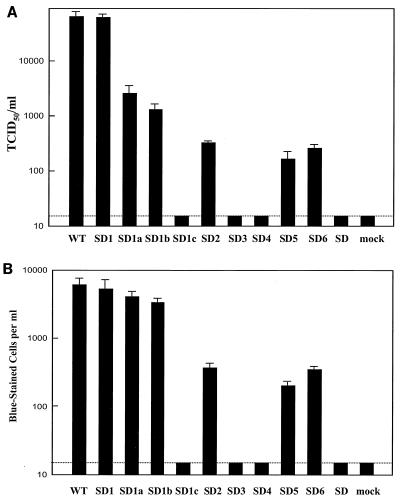

The infectiousness of these mutated viruses was also determined by the TCID50 assay in CEMx174 cells and by sMAGI assay (Fig. 5). The results are consistent with those obtained by growth curve assay as described above. Therefore, the deletion of leader sequences downstream of the primer binding site adversely affected viral infectiousness.

FIG. 5.

Infectiousness of the wild type (WT) and various mutated viruses. The results shown are the averages of three independent experiments. Each of the SD, SD1c, SD3, and SD4 viruses was shown to be poorly infectious, with RT values being below the threshold sensitivity of the assay (dashed line). Mock infection represents a negative control in which cells were exposed to heat-inactivated wild-type virus. (A) TCID50s of the wild type and various mutated viruses were determined by infection of CEMx174 cells as described in Materials and Methods. (B) Infectivity was tested by sMAGI assays as described previously (5). Numbers of blue-stained cells were scored and plotted.

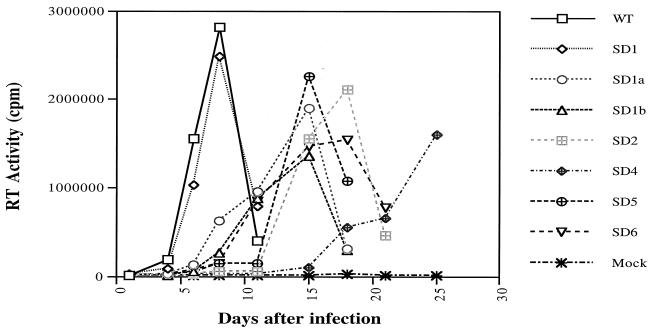

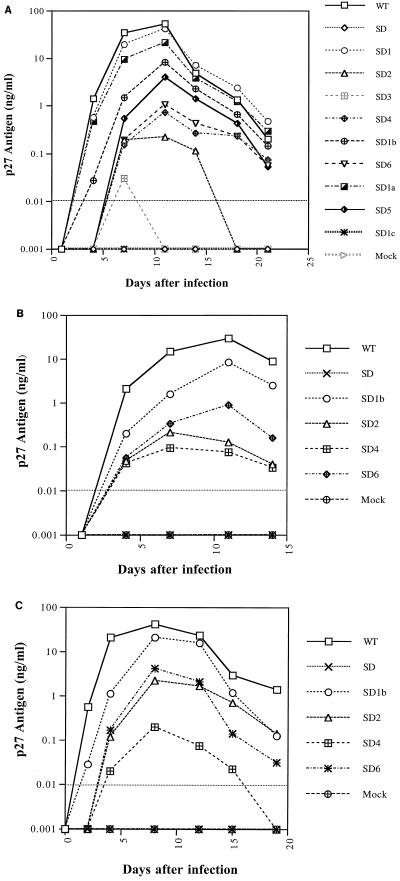

Replication of deleted viruses in macaque PBMCs.

As shown in Fig. 6A, SD1 viruses (deletion of the sequence of position +322 to +344) grew in PBMCs with kinetics close to those of wild-type virus. In contrast, both SD1a and SD1b showed impairment in replication capacity, growing to only 20 to 40% of wild-type levels. The replication of the SD1c mutant was completely impaired in these studies. This again reaffirms that the 9-nt sequences at positions +371 to +379 are extremely important. This is also shown in the case of the SD6 virus, which was highly impaired in replication capacity and grew to only 5% of wild-type levels. Deletion of the sequences from +380 to +397 (SD5) only moderately impaired viral replication (i.e., 10% of the wild-type virus level), while SD2 and SD4 were even further diminished in this regard, i.e., <1% of wild-type levels. As with SD1c, the replication levels of the SD and SD3 viruses were below the limit of detection. This is in contrast to infection in C8166 cells, in which SD and SD3 produced detectable levels of viral p27 antigen (17). Therefore, these mutants were also attenuated in monkey PBMCs, in which the relative in vitro virulence of those viruses can be ranked as follows: SD, SD3, SD1c<SD4<SD2<SD6<SD5<SD1b<SD1a<SD1<wild type.

FIG. 6.

Replication capacity of the wild type (WT) and mutated viruses in monkey PBMCs. Equivalent amounts of virus were used to infect rhesus macaque PBMCs based on levels of p27 antigen as described in Materials and Methods. Viral replication was monitored by SIV p27 antigen ELISA of culture fluids. Mock infection denotes exposure of cells to heat-inactivated wild-type virus as a negative control. The dashed line representing 0.01 ng of p27 per ml illustrates the threshold sensitivity of the assay. (A) Growth curves in PBMCs obtained from monkey 1. (B) Growth curves in PBMCs harvested 6 months later from the same animal. (C) Growth curves in PBMCs from monkey 2.

We further examined the relative replication capacity of these mutants in monkey PBMCs by using blood samples from the same animal harvested 6 months apart as well as blood from another monkey. The results in Fig. 6B and C show that our mutant viruses were similarly impaired in replication capacity, as were the viruses studied in Fig. 6A, except that the SD2 virus displayed marginally greater replication in the PBMCs of monkey 2 than in those of monkey 1.

To investigate the potential for phenotypic reversion of these mutants after replication in monkey PBMCs, several cell-free viruses harvested at 7 days after infection of PBMCs (Fig. 6A) were used to infect new PBMCs from the same animal as well as CEMx174 cells. As shown in Fig. 7A and B, these passaged viruses still showed impaired replication kinetics similar to those seen during the initial infection of the PBMCs (Fig. 6A) and CEMx174 cells (Fig. 3A).

FIG. 7.

Replication capacity of mutated virus derived from monkey PBMCs. Viruses equivalent to 200 pg of p27 antigen derived from infected PBMCs of monkey 1 were used to infect 105 PBMCs of the same monkey or 105 CEMx174 cells. Viral replication was monitored by SIV p27 antigen enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay of culture fluids. Mock infection denotes exposure of cells to heat-inactivated wild-type (WT) virus as a negative control. The dashed line representing 0.01 ng of p27 per ml illustrates the threshold sensitivity of the assay. (A) Growth curves of second-passage virus in monkey PBMCs. (B) Growth curves of second-passage virus in CEMx174 cells.

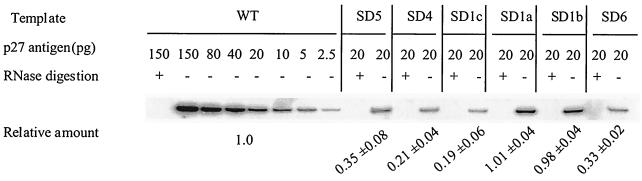

Deletions of sequences at positions +322 to +418 affect both packaging of viral genomic RNA and processing of Gag precursor protein.

We previously showed that a large deletion in each of the SD, SD2, and SD3 constructs could adversely impact packaging of viral genomic RNA (17). To study this subject mechanistically in these and our more stably attenuated viruses, we next analyzed the efficiency of viral RNA packaging in the mutated viruses containing small deletions in the leader region. RT-PCR was employed to amplify a region of the gag gene as previously described (17). The results in Fig. 8 show that both the SD1a and SD1b mutants packaged viral RNA with efficiency similar to that of wild-type virus, while the deletions in the SD1c, SD4, SD5, and SD6 constructs reduced packaging to 19, 21, 35, and 33% of wild-type levels, respectively. Thus, the sequences at both positions +371 to +379 and +380 to +397 apparently play a key role in viral RNA packaging, while those at positions +322 to +370 do not.

FIG. 8.

Viral RNA packaging in the wild type (WT) and mutated viruses. Equivalent amounts of virus derived from transfected COS-7 cells, based on levels of p27 antigen, were used to prepare viral RNA, which was then used as a template for quantitative RT-PCR to detect the full-length viral RNA genome in an 18-cycle PCR. Relative amounts of a 114-bp DNA product were quantified by molecular imaging, with wild-type values arbitrarily set at 1.0. Reactions run with RNA template, digested by DNase-free RNase, served as a negative control for each sample to exclude any potential DNA contamination. Relative amounts of viral RNA that were packaged were determined on the basis of four different experiments.

To shed further light on these deficits, we also examined the processing of Gag precursor proteins through short-term radiolabeling and immunoprecipitation experiments, since previous work with HIV-1 had shown that leader sequences are important for protein processing (28, 29). Immunoprecipitation of viral proteins in cell lysates was achieved through use of MAbs against SIV p27 (CA); this permitted identification of the Gag precursor Pr55, the intermediate proteins p40 and p28, and the mature p27 product. The amount of each protein was quantified by densitometry, and for each virus, the percentage of each band relative to total protein was plotted (Fig. 9). We found that the SD1 mutant possessed proportions of these four proteins similar to those of wild-type virus, while all of the other mutants displayed an accumulation of each of the Pr55, p40, and p28 proteins and diminished levels of p27. Both the SD1a and SD1b mutants appeared to suffer only minor impairment in the processing of Gag precursor proteins, while SD1c and SD6 were moderately affected in this regard. In contrast, the deletions in SD2, SD3, SD4, SD5, and SD resulted in severely impaired processing of Gag precursor proteins.

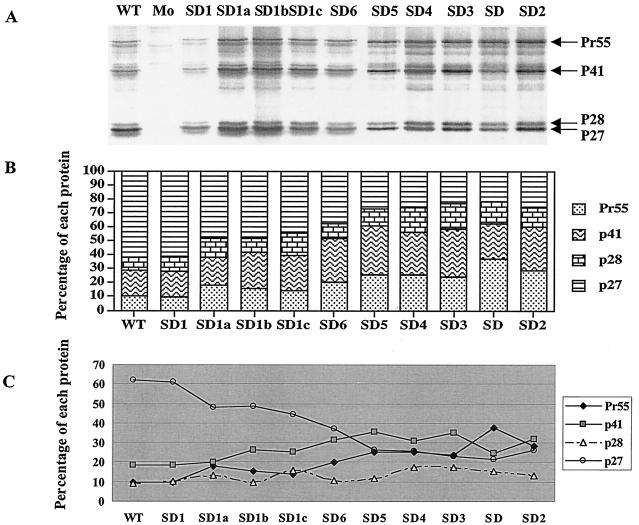

FIG. 9.

Processing of SIV Gag precursor proteins. 293T cells transfected with wild-type (WT) or mutated SIV constructs were radiolabeled and viral proteins in the cell lysates were then immunoprecipitated with MAbs against SIV p27 as described in Materials and Methods. The positions of viral Gag proteins are shown on the right side of the gel (A). Mo, mock transfection control. The percentage of each viral protein relative to all viral proteins detected was calculated with the NIH Image program. The results are illustrated as well by a bar graph (B) showing the different percentages of each band associated with each of the constructs studied, as well as by a line chart (C), showing a steady change in band representation from wild-type virus to the mutated constructs.

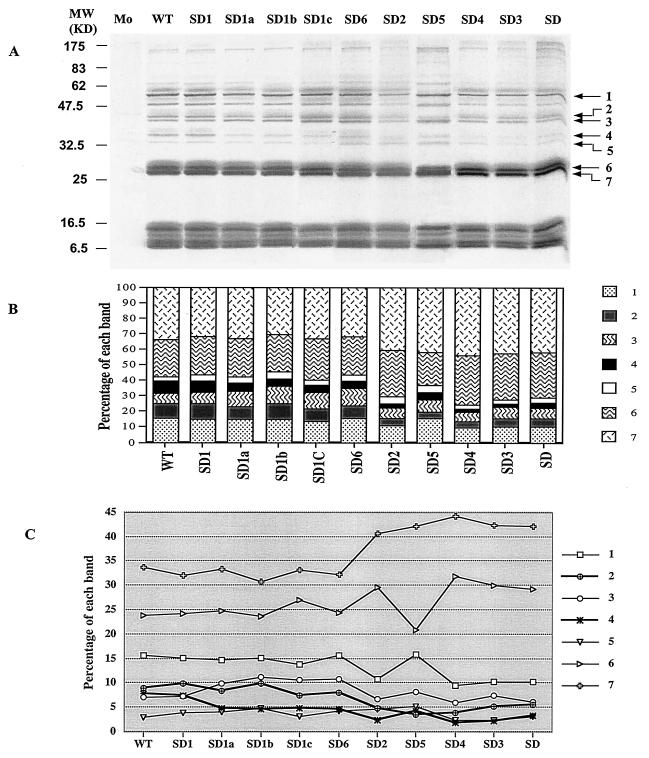

To further study this topic, 35S-labeled viral progeny that were released during 1 h from 293T cells were purified at 24 h after transfection; their protein band patterns are shown in Fig. 10. Seven of the protein bands were quantified by densitometry, and for each virus, the percentage of each band versus all seven proteins was plotted (Fig. 10). The seven bands include the Gag precursor Pr55 (band 1), the Gag intermediate proteins p40 (band 3) and p28 (band 6), and the mature p27 product (CA, band 7). The other three bands, with molecular masses of 43 (band 2), 36 (band 4), and 34 (band 5) kDa, cannot be easily identified, but most likely represent proteins that are found to a limited extent in virions (e.g., the integrase, the transmembrane envelope protein, or the Gag intermediate proteins present in immature virions). We found that the SD1 virus displayed a protein pattern similar to that of wild-type virus, while all of the other mutated viruses appeared to be modified, particularly with regard to bands 2 and 4, which were represented only to a limited extent.

FIG. 10.

Protein band patterns in the wild type (WT) and mutated SIV. 35S-labeled viral progeny that had been released over 1 h from 293T cells were purified at 24 h after transfection; protein patterns are shown (A). Mo, mock transfection control. Seven of the protein bands were quantified by densitometry with the NIH Image program. For each virus, the percentage of each band versus all seven bands was calculated. The results are illustrated as well by a bar graph (B) showing the different percentages of each band associated with each of the constructs studied, as well as by a line chart (C) showing a steady change in band representation from wild-type virus to the mutated constructs.

DISCUSSION

The RNA genomes of both HIV-1 and SIV contain a long 5′ untranslated leader sequence that is crucial for viral replication. Although the 5′ untranslated leader sequence of SIV has little sequence homology with that of HIV-1, similar secondary structures have been predicted for both (37). Studies with HIV-1 have shown that the leader sequences between the primer binding site and the major splice donor site are important for viral replication and are involved in packaging of viral RNA, gene expression, the processing of viral core protein, and reverse transcription (20, 22, 24–29). In the case of SIV, this region is also involved in the packaging of viral RNA (17). The present work extends these observations by showing that deletion of the upper part of the U5-leader stem did not impair viral RNA packaging (SD1a, SD1b), but did affect both the patterns of viral proteins and Gag precursor processing.

The lower part of the stem-loop is even more important, since all deletions in this region resulted in severely impaired replication capacity, as well as decreased packaging of viral RNA, delayed processing of Gag precursor proteins, and changed patterns of viral proteins. It may be that a stable U5-leader stem is essential for virus replication and that this stem is destroyed by deletions in its lower part, but not upper part. Our results also show that the sequence between the U5-leader stem-loop and the putative DIS stem-loop is important. Deletion of this region adversely affected packaging of viral RNA, processing of Gag proteins, and patterns of viral proteins. From a mechanistic standpoint, it is known that viral RNA packaging is a process involving specific recognition between viral proteins and viral RNA elements.

Studies with HIV-1 have shown that the viral nucleocapsid (NC) protein, which is required for packaging of viral RNA, can bind to viral leader RNA sequences with high affinity in cell-free assays (8). An encapsidation signal, located at the 5′ end of the viral genome, consists of four RNA stem-loop structures, termed SL1 to SL4, and of these, SL1 and SL3 are the major elements that bind NC proteins (6, 19, 32). Deletions of SL1 in HIV-1 were shown to impair viral replication, as well as cause delayed processing of Gag proteins and decreased levels of viral RNA packaging (26, 28). Compensatory point mutations in four distant Gag proteins, i.e., NC, MA, CA, and p2, were able to restore these deficits (27, 29). Similar studies with SIV have also shown that deletions of leader sequences that affect viral RNA packaging can be rescued by compensatory point mutations in Gag proteins (17). These observations and the present work suggest the likelihood of important functional interactions between Gag proteins and leader sequences in both HIV-1 and SIV. Both the processing of Gag proteins and encapsidation of viral RNA may require that leader RNA sequences exist within constraints of proper tertiary structure, which are highly conserved in both HIV-1 and SIV (37). The changes reported here with regard to patterns of viral proteins may be the consequence of impaired processing of Gag proteins. Such delayed processing, caused by our deletions, may result in abnormal incorporation of proteins into virions, although other mechanisms to explain the attenuation effects seen here are also possible and are under investigation.

The development of a safe, effective vaccine to protect against infection by HIV-1 must be regarded as a top priority in public health. In monkeys, live attenuated SIVs have been shown to induce a protective immune response against pathogenic strains (1, 7, 9, 13, 43). Most of this work has involved deletions of accessory genes, such as nef, vpr, or vpx. However, these mutated viruses have retained replication capacity similar to that of wild-type virus in permissive cell lines (15, 34). In addition, multiply deleted SIV variants have been shown to be pathogenic in neonatal macaques (2, 3).

In contrast, our group has studied viruses containing deletions in the noncoding leader regions of both HIV-1 and SIV (17, 25–29). Unlike the SIV strains that have been mutated in accessory genes, our deleted viruses are significantly impaired in replication capacity in cell lines, yet they retain all viral genes, including accessory genes. This may be important, since the Nef protein and other viral nonstructural proteins are important targets of antiviral immune responses (42, 45). In the present work, we have constructed a series of SIV mutants that are attenuated to different extents in replication capacity in both human T-cell lines and macaque PBMCs. Next, we wish to evaluate the safety and protective capacity of these constructs in a macaque monkey model.

The attenuation strategies employed in our work versus deletions in accessory genes also have different mechanistic consequences. Deletion of accessory genes can compromise the ability of the virus to replicate under certain circumstances (10), but such attenuation is relatively inefficient, since the viruses retain replication capacity in cell lines and because multiply deleted SIV mutants are still pathogenic (2, 3, 37). Of course, further deletions in genes such as tat and rev, which are important for disease progression (42, 44, 45), may have yielded better long-term results. In contrast, our deletions of leader sequences may impair multiple steps in the viral life cycle, since the deleted sequences are contained in all viral RNA species (both full-length viral RNA and spliced viral RNA) and are involved in multiple functions (17, 20, 22, 24–29).

Studies of SIV infection of rhesus macaques have indicated that the intrinsic susceptibility of monkey PBMCs to infection with SIV in vitro was predictive of relative viremia after SIV challenge (16, 30, 40). However, significant animal-to-animal variation exists, and it is difficult to identify viruses that fit the “window” between levels of replication that elicit a protective immune response and those that result in disease (38). Our panel of novel mutants displayed a wide range of replication levels, i.e., from minor to severe impairment, in both T-cell lines and monkey PBMCs. This constitutes a major advantage of our novel, live attenuated viruses compared with multi-gene-deleted SIVs that retain high levels of replication competence in T-cell lines and often in PBMCs as well (15, 34). In vivo analysis of our panel of mutants may identify viruses that do fit the “window” required for identification of the requisite level of viral replication in outbred hosts.

A major safety concern with regard to live attenuated viruses as vaccine candidates is the problem of phenotypic reversion. Our experiments with PBMCs from two different monkeys as well as separate time points showed that our mutants were stably attenuated in these cells. In contrast, some of our constructs did show a potential for reversion in a T-cell line; however, such reversion appeared only gradually and involved several additional mutations (17). Replication studies with PBMCs showed no reversion of viruses that had been passaged in either PBMCs or CEMx174 cells. Hence, we hope that the potential for reversion in vivo, under the pressure of an immune response, would be minimal and that it might not result in disease.

Of all of the attenuated constructs that we have developed, we believe that SD4 holds the most potential for work in animals. Further studies will hopefully be directed toward assessing its stability and ability to induce immune responsiveness in both newborn and adult rhesus macaques.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by grant RO1 AI43878–01 to M.A.W. from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health. The following reagents were obtained through the AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program, Division of AIDS, NIAID, NIH: the CEMx174 cell line from Peter Cresswell and the sMAGI assay system from Julie Overbaugh.

We thank Mervi Detorio and Maureen Oliveira for technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Almond N, Kent K, Crannage M, Rud E, Clark B, Stott E J. Protection by attenuated simian immunodeficiency virus in macaques against challenge with virus-infected cells. Lancet. 1995;345:1342–1344. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)92540-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baba T W, Jeong Y S, Pennick D, Bronson R, Greene M F, Ruprecht R M. Pathogenicity of live, attenuated SIV after mucosal infection of neonatal macaques. Science. 1995;267:1820–1825. doi: 10.1126/science.7892606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baba T W, Liska V, Khimani A H, Ray N B, Dailey P J, Penninck D, Bronson R, Greene R, Greene M F, McClure H M, Martin L N, Ruprecht R M. Live attenuated, multiply deleted simian immunodeficiency virus causes AIDS in infant and adult macaques. Nat Med. 1999;5:194–203. doi: 10.1038/5557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boykins R A, Mahieux R, Shankavaram U T, Gho Y S, Lee S F, Hewlett I K, Wahl L M, Kleinman H K, Brady J N, Yamada K M, Dhawan S. Cutting edge: a short polypeptide domain of HIV-1-Tat protein mediates pathogenesis. J Immunol. 1999;163:15–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chackerian B, Haigwood N L, Overbaugh J. Characterization of a CD4 expressing macaque cell line that can detect virus after a single replication cycle and can be infected by diverse simian immunodeficiency virus isolates. Virology. 1995;213:386–394. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.0011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clever J L, Parslow T G. Mutant human immunodeficiency virus type 1 genomes with defects in RNA dimerization or encapsidation. J Virol. 1997;71:3407–3414. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.5.3407-3414.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Daniel M D, Kirchhoff F, Czajak S C, Sehgal P K, Desrosiers R C. Protective effects of a live attenuated SIV vaccine with a deletion in the nef gene. Science. 1992;258:1938–1941. doi: 10.1126/science.1470917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dannull J, Surovoy A, Jung G, Moelling K. Specific binding of HIV-1 nucleocapsid protein to PSI RNA in vitro requires N-terminal zinc finger and flanking basic amino acid residues. EMBO J. 1994;13:1525–1533. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06414.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Desrosiers R C, Lifson J D, Gibbs J S, Czajak S C, Howe A Y M, Arthur L O, Johnson R P. Identification of highly attenuated mutants of simian immunodeficiency virus. J Virol. 1998;72:1431–1437. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.2.1431-1437.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Desrosiers R C. Strategies used by human immunodeficiency virus that allow persistent viral replication. Nat Med. 1999;5:723–725. doi: 10.1038/10439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dulbecco R. The nature of viruses. In: Dulbecco R, Ginsberg H S, editors. Virology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, Pa: J. B. Lippincott; 1988. pp. 22–25. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ensoli B, Cafaro A. Control of viral replication and disease onset in cynomolgus monkeys by HIV-1 TAT vaccine. J Biol Regul Homeost Agents. 2000;14:22–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gauduin M C, Glickman R L, Ahmad S, Yilma T, Johnson R P. Immunization with live attenuated simian immunodeficiency virus induces strong type 1 T helper responses and beta-chemokine production. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:14031–14036. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.24.14031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Geretti A M. Simian immunodeficiency virus as a model of human HIV disease. Rev Med Virol. 1999;9:57–67. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1654(199901/03)9:1<57::aid-rmv237>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gibbs J S, Regier D A, Desrosiers R C. Construction and in vitro properties of SIVmac mutants with deletions in nonessential genes. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir. 1994;10:607–616. doi: 10.1089/aid.1994.10.607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goldstein S, Brown C R, Dehghani H, Lifson J D, Hirsch V M. Intrinsic susceptibility of rhesus macaque peripheral CD4+ T cells to simian immunodeficiency virus in vitro is predictive of in vivo viral replication. J Virol. 2000;74:9388–9395. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.20.9388-9395.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guan Y, Whitney J B, Diallo K, Wainberg M A. Leader sequences downstream of the primer binding site are important for efficient replication of simian immunodeficiency virus. J Virol. 2000;74:8854–8860. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.19.8854-8860.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gundlach B R, Lewis M G, Sopper S, Schnell T, Sodroski J, Stahl-Hennig C, Überla K. Evidence for recombination of live, attenuated immunodeficiency virus vaccine with challenge virus to a more virulent strain. J Virol. 2000;74:3537–3542. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.8.3537-3542.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harrison G P, Lever A M L. The human immunodeficiency virus type 1 packaging signal and major splice donor region have a conserved stable secondary structure. J Virol. 1992;66:4144–4153. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.7.4144-4153.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harrison G P, Miele G, Hunter E, Lever A M L. Functional analysis of the core human immunodeficiency virus type 1 packaging signal in a permissive cell line. J Virol. 1998;72:5886–5896. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.7.5886-5896.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johnson R P, Desrosiers R C. Protective immunity induced by live attenuated simian immunodeficiency virus. Curr Opin Immunol. 1998;10:436–443. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(98)80118-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kaye J F, Lever A M L. Human immunodeficiency virus types 1 and 2 differ in the predominant mechanism used for selection of genomic RNA for encapsidation. J Virol. 1999;73:3023–3031. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.4.3023-3031.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kestler H, Kodama T, Ringler D, Sehgal P, Daniel M D, King N, Desrosiers R C. Induction of AIDS in rhesus monkeys by molecularly cloned simian immunodeficiency virus. Science. 1990;248:1109–1112. doi: 10.1126/science.2160735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lenz C, Scheid A, Schaal H. Exon 1 leader sequences downstream of U5 are important for efficient human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gene expression. J Virol. 1997;71:2757–2764. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.4.2757-2764.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li X, Liang C, Quan Y, Chandok R, Laughrea M, Parniak M A, Kleiman L, Wainberg M A. Identification of sequences downstream of the primer-binding site that are important for efficient replication of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol. 1997;71:6003–6010. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.8.6003-6010.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liang C, Li X, Quan Y, Laughrea M, Kleiman L, Hiscott J, Wainberg M A. Sequence elements downstream of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 long terminal repeat are required for efficient viral gene transcription. J Mol Biol. 1997;272:167–177. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liang C, Rong L, Quan Y, Laughrea M, Kleiman L, Wainberg M A. Mutations within four distinct Gag proteins are required to restore replication of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 after deletion mutagenesis within the dimerization initiation site. J Virol. 1999;73:7014–7020. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.8.7014-7020.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liang C, Rong L, Cherry E, Kleiman L, Laughrea M, Wainberg M A. Deletion mutagenesis within the dimerization initiation site of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 results in delayed processing of the p2 peptide from precursor proteins. J Virol. 1999;73:6147–6151. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.7.6147-6151.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liang C, Rong L, Russell R S, Wainberg M A. Deletion mutagenesis downstream of the 5′ long terminal repeat of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 is compensated for by point mutations in both the U5 region and gag gene. J Virol. 2000;74:6251–6261. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.14.6251-6261.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lifson J D, Nowak M, Goldstein S, Rossio J L, Kinter A, Vasquez G, Wiltrout T A, Brown C, Schneider D, Wahl L, Lloyd A L, Elkins W R, Fauci A S, Hirsch V M. The extent of early viral replication is a critical determinant of the natural history of simian immunodeficiency virus infection. J Virol. 1997;71:9508–9514. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.12.9508-9514.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maniatis T, Fritsch E F, Sambrook J. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 32.McBride M S, Panganiban A T. The human immunodeficiency virus type 1 encapsidation site is a multipartite RNA element composed of functional hairpin structures. J Virol. 1996;70:2963–2973. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.5.2963-2973.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mellors J W, Rinaldo C R J, Gupta P, White R M, Todd J A, Kingsley L A. Prognosis in HIV-1 infection predicted by the quantity of virus in plasma. Science. 1996;272:1167–1170. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5265.1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Messmer D, Ignatius R, Santisteban C, Steinman R M, Pope M. The decreased replicative capacity of simian immunodeficiency virus SIVmac239Δnef is manifest in cultures of immature dendritic cells and T cells. J Virol. 2000;74:2406–2413. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.5.2406-2413.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nathanson N, Hirsch V M, Mathieson B J. The role of nonhuman primates in the development of an AIDS vaccine. AIDS. 1999;13(Suppl. A):S113–S120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rappaport J, Joseph J, Croul S, Alexander G, Del Valle L, Amini S, Khalili K. Molecular pathway involved in HIV-1-induced CNS pathology: role of viral regulatory protein, Tat. J Leukoc Biol. 1999;65:458–465. doi: 10.1002/jlb.65.4.458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rizvi T A, Panganiban A T. Simian immunodeficiency virus RNA is efficiently encapsidated by human immunodeficiency virus type 1 particles. J Virol. 1993;67:2681–2688. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.5.2681-2688.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ruprecht R M. Live attenuated AIDS viruses as vaccines: promise or peril? Immunol Rev. 1999;170:135–149. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1999.tb01335.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Salter R D, Howell D N, Cresswell P. Genes regulating HLA class-I antigen expression in T-B lymphoblast hybrids. Immunogenetics. 1985;21:235–246. doi: 10.1007/BF00375376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Seman A L, Pewen W F, Fresh L F, Martin L N, Murphey-Corb M. The replicative capacity of rhesus macaque peripheral blood mononuclear cells for simian immunodeficiency virus in vitro is predictive of the rate of progression to AIDS in vivo. J Gen Virol. 2000;81:2441–2449. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-81-10-2441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stott J, Hu S L, Almond N. Candidate vaccines protect macaques against primate immunodeficiency viruses. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir Suppl. 1998;3:S265–S267. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.van Baalen C A, Pontesilli O, Huisman R C, Geretti A M, Klein M R, de Wolf F, Miedema F, Gruters R A, Osterhaus A D. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Rev- and Tat-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes inversely correlate with rapid progression to AIDS. J Gen Virol. 1997;78:1913–1918. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-78-8-1913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wyand M S, Manson K, Montefiori D C, Lifson J D, Johnson R P, Desrosiers R C. Protection by live, attenuated simian immunodeficiency virus against heterologous challenge. J Virol. 1999;73:8356–8363. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.10.8356-8363.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yamada T, Iwamoto A. Comparison of proviral accessory genes between long-term nonprogressors and progressors of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. Arch Virol. 2000;145:1021–1027. doi: 10.1007/s007050050692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zagury J F, Sill A, Blattner W, Lachgar A, Le Buanec H, Richardson M, Rappaport J, Hendel H, Bizzini B, Gringeri A, Carcagno M, Criscuolo M, Burny A, Gallo R C, Zagury D. Antibodies to the HIV-1 Tat protein correlated with nonprogression to AIDS: a rationale for the use of Tat toxoid as an HIV-1 vaccine. J Hum Virol. 1998;1:282–292. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]