Abstract

The Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) BamHI-A rightward transcripts (BARTs) are expressed in all EBV-associated tumors as well as in latently infected B cells in vivo and cultured B-cell lines. One of the BART family transcripts contains an open reading frame, RPMS1, that encodes a nuclear protein termed RPMS. Reverse transcription-PCR analysis revealed that BART transcripts with the splicing pattern that generates the RPMS1 open reading frame are commonly expressed in EBV-positive lymphoblastoid cell lines and are also detected in Hodgkin's disease tissues. Experiments undertaken to determine the function of RPMS revealed that RPMS interacts with both CBF1 and components of the CBF1-associated corepressor complex. RPMS interaction with CBF1 was demonstrated in a glutathione S-transferase (GST) affinity assay and by the ability of RPMS to alter the intracellular localization of a mutant CBF1. A Gal4-RPMS fusion protein mediated transcriptional repression, suggesting an additional interaction between RPMS and corepressor proteins. GST affinity assays revealed interaction between RPMS and the corepressor Sin3A and CIR. The RPMS-CIR interaction was further substantiated in mammalian two-hybrid, coimmunoprecipitation, and colocalization experiments. RPMS has been shown to interfere with NotchIC and EBNA2 activation of CBF1-containing promoters in reporter assays. Consistent with this function, immunofluorescence assays performed on cotransfected cells showed that there was colocalization of RPMS with NotchIC and with EBNA2 in intranuclear punctate speckles. The effect of RPMS on NotchIC function was further examined in a muscle cell differentiation assay where RPMS was found to partially reverse NotchIC-mediated inhibition of differentiation. The mechanism of RPMS action was examined in cotransfection and mammalian two-hybrid assays. The results revealed that RPMS blocked relief of CBF1-mediated repression and interfered with SKIP-CIR interactions. We conclude that RPMS acts as a negative regulator of EBNA2 and Notch activity through its interactions with the CBF1-associated corepressor complex.

In latently Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-infected cell lines and tumors, there is consistent expression of a family of alternatively spliced, polyadenylated transcripts that arise from the BamHI-A region of the EBV genome. These RNAs are transcribed in the rightward direction, antisense to a block of lytic genes also within BamHI-A, and are referred to as BamHI-A rightward transcripts (BARTs), or complementary strand transcripts. BARTs were first identified in association with nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) xenografts and tumor biopsy tissues (5, 11, 12, 17, 27) and subsequently found to be expressed in all EBV-associated tumors that have been examined (6, 7, 51, 56), as well as at lower levels in lymphoblastoid cell lines in culture (2, 5, 44). The antisense nature of the transcripts relative to the lytic genes in this region of the genome led to the postulate that the BARTs might serve as regulatory RNAs to limit lytic gene expression and help ensure maintainance of the viral latency program (27). While it is reasonable that the BARTs may serve in this capacity, the presence of a functional polyadenylation signal at 160,989 strongly suggested that these transcripts would also be protein encoding.

Analysis of the structure of individual BARTs has identified a number of potential open reading frames (ORFs) in these transcripts. Those that initiate with ATG codons and have elicited the most attention are BARF0, RK-BARF0, A73, and RPMS1 (5, 10, 12, 27, 44, 46, 47). Evidence for expression of these ORFs as protein products during latent EBV infection is currently limited. In vitro-translated BARF0 polypeptides have been immunoprecipitated by using serum from patients with NPC (12), and CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes isolated from healthy seropositive donors were able to kill cells transfected with a BARF0 expression vector (30). RK-BARF0 was reported to be detected in the membrane-associated fractions of EBV-positive cell lines and NPC and Burkitt's lymphoma biopsies (10), but the possibility of antiserum cross-reactivity with cell proteins was raised in another study that found RK-BARF0 to be localized in the nucleus of transfected cells (29). Protein expression from the A73 and RPMS1 ORFs has only been demonstrated in cells transfected with expression vectors for these ORFs. A73 localized to the cytoplasm of transfected cells and in a yeast two-hybrid assay interacted with the cell protein RACK1, a protein involved in regulating signaling from protein kinase C and Src tyrosine kinases (46). The RPMS protein is nuclear in transfected cells (4, 46) and was shown to bind to CBF1 in glutathione S-transferase (GST) affinity assays and to interfere with EBNA2 and NotchIC activation of reporters containing CBF1 binding sites in transient-expression assays (46).

In binding to CBF1, RPMS joins the EBNA2 and EBNA3A, -3B, and -3C proteins as an EBV-encoded protein that interacts with CBF1 and consequently has the potential to modify cellular Notch signaling. CBF1 (RBP-Jκ, RBP-2N, Jκ) is a member of the CSL (CBF1, Supressor of Hairless, Lag-1) family of DNA binding proteins that are downstream nuclear effectors of the evolutionarily conserved Notch signal transduction pathway. CBF1 mediates transcriptional repression through the tethering of a histone deacetylase (HDAC)-associated corepressor complex whose identified components include SMRT, HDAC1/2, Sin3A, SAP30, and CIR (21, 26, 60). Binding of activated Notch to CBF1 displaces the repression complex and through the presence of an intrinsic activation domain brings about transcriptional activation (19, 23, 61). The transmembrane receptor Notch mediates intercellular signaling events that affect cell fate decisions through modification of differentiation, proliferation, and apoptotic responses (1, 13, 38). Notch ligands are also transmembrane proteins, and on ligand binding Notch undergoes a series of proteolytic cleavage events that result in the release of the intracellular domain of Notch, NotchIC, which contains nuclear localization signals and translocates to the nucleus (8, 45, 48, 50, 58). Constitutive expression of NotchIC recapitulates the phenotypes generated by ligand-induced signaling (9, 31, 34, 49).

The targeting of CBF1 by EBNA2 (14, 16, 35, 53, 62) and the extraordinary similarity of the EBNA2 and NotchIC interactions with CBF1 led to the recognition that EBNA2 functions in large part by mimicking Notch signaling (15, 18, 19, 60, 61). The EBNA3A and -3C proteins are essential for in vitro immortalization of B cells (52), and these proteins also bind to CBF1 and have been found to compete with EBNA2 for CBF1 interaction and to abolish DNA binding by CBF1 (25, 43, 54, 59). The EBNA2 and EBNA3 proteins are expressed on primary infection of B cells and in B lymphoblastoid cell lines, implying that manipulation of the Notch pathway is a key factor in B-cell proliferation and immortalization. However, EBNA2 and the EBNA3s are not expressed in the resting memory B cells that are the site of in vivo EBV latency (39, 40) or in the majority of EBV-associated tumors. In contrast, BARTs are expressed in both of these settings. The finding that the BART-encoded RPMS protein interacted with CBF1 (46) raised the possibility that manipulation of Notch signaling is an all-encompassing feature of EBV biology. We therefore further investigated the interactions of RPMS with CBF1 and its associated corepressor complex. The experimental results provide insights into the mechanism of RPMS interference with NotchIC and EBNA2 activation of CBF1-regulated promoters.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmids.

The RPMS1 ORF from a BART cDNA was amplified as a PCR fragment using the primers LGH1763 5′-GCTAAGATCTATGGCCGGCGCTCGTGC and LGH2636 5′-GACAGATCTTCACCTTTGGCTGGTACAGC. The PCR fragment was ligated into the BglII site of a modified SG5 vector expressing a Flag epitope (pJH253) to generate Flag-RPMS (pHC6) (4). The same fragment was also inserted into another modified SG5 vector which contains a six-Myc tag to generate RPMS-6xMyc (pAZ12), into the Gal4DBD vector pGH250 to generate Gal4DBD-RPMS (pAZ1), and into the pGEX vector to generate GST-RPMS (pHC29). The following plasmids used in this study have been described previously: SG5-EBNA2 (pPDL151) and EBNA2-ΔTA(pPDL102) (36); 5xGal4TK-CAT, 4xCp-CAT, Gal4-CBF1 (pJH93), mNotch1IC (pJH208), Flag-CBF1 (pJH282), and Flag-CBF1 (EEF233AAA) (pJH278) (19); CIR-Myc (pJH402), CIR-Rta (pJH513), and CIR-Flag (pJH518) (21); and Gal4-SKIP (pJH274), Myc-CBF1 (pMF1), Myc-mSin-3A (33, 61), and pBosrNotch1 (41).

Antibodies.

Chicken anti-RPMS polyclonal antibody was generated using the peptide GPRGRPPHSRTRARRTS as immunogen. Purified chicken anti-RPMS immunoglobulin Y (IgY) was used for indirect immunofluorescence assays (IFA) (1:200) and Western blotting (1:1,000). Rabbit anti-CIR (1:200) (21), rabbit anti-CBF1 (1:200) (61), mouse anti-EBNA2 (DAKO; 1:200), and mouse anti-BZLF protein antibody (DAKO; 1:50) were used for IFA staining. Secondary antibodies for IFA double labeling were rhodamine-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit IgG or donkey anti-mouse IgG and fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated donkey anti-mouse IgG or anti-rabbit IgG. Secondary antibodies were used at a 1:100 dilution. Mouse anti-Myc (Upstate; 1:2,000) and mouse anti-Flag (Sigma; 1:1,000) antibodies were used in Western blotting.

RNA extraction and RT-PCR.

EBV-positive cell lines B95-8, Rael, Akata, P3HR-1, and Daudi and the EBV-negative cell line BJAB were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum. The NPC cell line 666 (22) was also maintained in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum. The cells were harvested and lysed directly in extraction buffer, and cellular RNA was extracted according to the manufacturer's instructions. The two Hodgkin's disease biopsy samples (Hodgkin1 and Hodgkin2) were obtained from The Johns Hopkins Hospital. Reverse transcriptase (RT)-PCR was performed as described previously (4). Briefly, cDNA was synthesized from oligo(dT)-enriched RNA by incubation for 1 h at 42°C in a reaction mixture containing 1× RT buffer (Promega, Madison, Wis.), 0.4 mmol of deoxynucleotide triphosphates/liter, Rnasin (40 U), and avian myeloblastosis virus RT (5 U). PCR was performed with primers 5′-CACGATGTCCTGGTCAGAGTG and 5′-CCTTCGTATTGCAGTGTCTG for 35 cycles with each cycle being 94°C for 1.5 min, 57°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 2 min. After PCR amplification, PCR products were separated on a 1.5% agarose gel and the DNA was transferred onto a nylon membrane and preincubated for 2 to 4 h at 50°C in hybridization buffer (1× Denhardt's solution, 10% dextran sulfate, 20 mmol NaH2PO4/liter, 7% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 0.5× SSC [1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate], and 100 μg of denatured calf thymus DNA). Radiolabeled DNA oligonuleotide probe (5′-GCAGATATCCTGCGTCCTC) was then added to the hybridization buffer and the membrane was further incubated for 16 to 20 h. After hybridization, the membranes were washed twice for 30 min at 50°C in 1× SSC and exposed to X-ray film.

CAT assays.

HeLa cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum and plated at 1.25 × 105 cells per well in six-well plates (Nunc) 24 h prior to transfection. HeLa cells were transfected by the calcium phosphate procedure and received 0.8 μg of 5xGal4TK-CAT or 4xCp-CAT reporter and 1 μg of Gal4-RPMS, CIR-Rta, Gal4-SKIP, or 0.1 μg of NotchIC. Between 1 and 4 μg of RPMS-expressing plasmid was also transfected, as indicated in the figure legends. The total DNA was kept constant for each transfection reaction by using vector plasmid. Chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (CAT) assays were performed as previously described. Each experiment was repeated at least two times.

Immunofluorescence assays.

RPMS-Myc, CIR-Myc, CBF1, Notch, NotchIC, EBNA2, or Zta plasmids (1 μg of each) were transfected or cotransfected by the calcium phosphate procedure into Vero cells which were seeded in two-well LabTek slides (Nunc) at 0.8 × 105 cells per well and grown in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum. Forty-eight hours after transfection, cells were washed and fixed in 1% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 10 min at room temperature. Fixed cells were washed and permeabilized in 0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS for 20 min on ice. After washing, the cells were incubated with primary antibodies for 1 h at 37°C. Fluorochrome-conjugated secondary antibodies were incubated for 30 min at 37°C. The slides were washed and mounted with 80% glycerol, and images were captured using a Leitz fluorescence microscope and Image-Pro software (Media Cybernetics, Silver Spring, Md.).

Immunoprecipitation and Western blotting.

HeLa cells were seeded at 106 cells per 10-cm-diameter tissue culture dish and cotransfected with 5 μg of RPMS-Myc and 5 μg of CIR-Flag expression plasmids by the calcium phosphate method. Forty-eight hours after transfection, the cells were harvested and homogenized in 2.5 ml of ice-cold lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-Cl [pH 7.4], 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.5% NP-40, and 5% glycerol, plus the proteinase inhibitors phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, pepstatin, and aprotinin). The cell extract was passed six times through a 20-gauge syringe needle and then clarified by centrifugation for 10 min at 13,000 rpm (MICROSPIN245; Sorvall Instruments) at 4°C. Anti-Flag or anti-Myc mouse monoclonal antibody (Sigma) was mixed with 1 ml of cell extract and incubated at 4°C for 2 h followed by further incubation with protein A-Sepharose 4B (20 μl; Pharmacia) at 4°C for 2 h. The beads were then washed six times with lysis buffer and mixed with 35 μl of sample buffer. Samples (5 to 25 μl) were subjected to electrophoresis using a 10% denaturing polyacrylamide gel. The amount of sample loaded in the control lanes (direct immunoprecipitate) was one-fourth of the amount used for coimmunoprecipitated samples. Western blot analysis was performed using mouse anti-Myc antibody, peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse IgG secondary antibodies, and the Amersham enhanced chemiluminescence system.

GST-protein affinity assays.

HeLa cells in 10-cm-diameter dishes were transfected with 10 μg of Myc-CBF1, CIR-Flag, or Myc-Sin3A. Cell extracts were prepared 48 h after transfection by washing the cells with PBS followed by lysis in ice-cold lysis buffer and homogenization. Extracts from the bacterial cells induced to express GST-RPMS proteins were prepared by standard procedures. These extracts were incubated for 2 h at 4°C with glutathione-Sepharose 4B beads (Pharmacia), 20 μl per ml of extract. After three washes in lysis buffer, the bound GST fusion proteins were incubated for 2 h at 4°C with transfected HeLa cell extract. The beads were then washed 10 times in lysis buffer and added to 30 μl of sample buffer. Samples were separated on sodium dodecyl sulfate–10% polyacrylamide gels and then transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane, and bound protein was detected by Western blotting as described above.

Muscle cell differentiation assays.

The C2C12 cell line is a clonal mouse cell population that proliferates as mononuclear myoblasts in growth medium (DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum and 5% cosmic calf serum). These cells undergo morphological and molecular changes that correlate with muscle cell differentiation when they are switched to differentiation medium (DMEM plus 10% horse serum). CDN2 cells are C2C12 cells selected for expression of the Notch2 intracellular domain (20). An RPMS-expressing plasmid was transfected into CDN2 cells, and a stably transfected cell population was obtained using hygromycin selection (250 μg/ml). The muscle fusion assays were performed essentially as previously described (20). Briefly, C2C12, CDN2, and CDN2-RPMS cells were plated in 10-cm-diameter dishes in growth medium. When the cells were 80% confluent, they were switched to differentiation medium and monitored daily. The differentiation medium was changed every two days. After 6 days of differentiation induction, the cells were photographed.

RESULTS

RPMS-encoding transcripts are commonly expressed in EBV-infected cell lines.

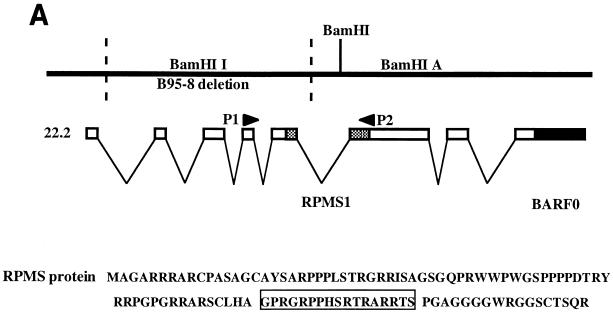

The EBV BARTs are a family of multispliced mRNAs that contain a number of potential ORFs, including BARF0, RK-BARF0, A73, and RPMS1 (44, 46, 47). The relative locations of the RPMS1 and BARF0 ORFs are shown in Fig. 1A. We detected the expression of transcripts with a splicing pattern that generates the RPMS1 ORF in a variety of different EBV-infected B-cell lines, the NPC-derived 666 epithelial cell line, and in two Hodgkin's disease tissues by RT-PCR. The RT-PCR products generated using the specific primers P1 and P2 (Fig. 1A) were visualized by Southern blotting with an internal oligonucleotide probe (Fig. 1B). The specificity of the primers and probe used in this assay have been documented previously (4). The primer pair is separated by 2 introns and 5.4 kb of genomic DNA sequence. The expected RT-generated cDNA product is 380 bp. A specific band of 380 bp appeared in all EBV-positive cell lines tested except B95-8. B95-8 cells carry an EBV genome in which the RPMS1 ORF region is deleted. The EBV-negative cell line BJAB also gave negative results.

FIG. 1.

Structure and expression of RPMS-encoding mRNA. (A) Relative positions of the RPMS1 and BARF0 ORFs in EBV BARTs. The locations of the PCR primers (P1 and P2) used to detect RPMS-encoding mRNA in panel B are indicated. The predicted amino acid sequence of the RPMS protein is shown, with the segment used to generate anti-RPMS polyclonal antibody boxed. (B) Expression of RPMS-encoding transcripts in EBV-infected cell lines and Hodgkin's disease tissue. RT-PCR analysis was performed using the P1 and P2 primers specific for the RPMS1 transcript, and the PCR products were identified on Southern blots using a radiolabeled internal oligonucleotide probe. BJAB, an EBV-negative B-cell line, and B95-8, a B-cell line carrying an EBV genome with a deletion of the RPMS1 ORF, were used as negative controls.

RPMS protein expression in transfected cells.

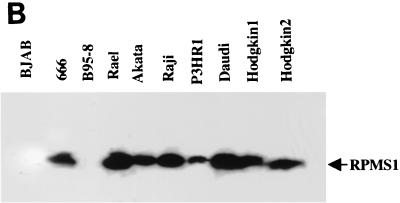

Previously, the RPMS1 ORF was shown to encode a nuclear protein that could be detected in transient-expression assays performed using antibody recognizing an epitope-tagged protein (4, 46). To generate RPMS-specific immunological reagents, we used a synthetic peptide (Fig. 1A) to produce a chicken anti-RPMS polyclonal antibody. Using this antibody, we detected a protein of 25 kDa in RPMS-6xMyc-transfected HeLa cells by Western blotting (Fig. 2A, lane 3). A band of the same size was also detected in RPMS-6xMyc-transfected HeLa extract probed with a mouse anti-Myc antibody (lane 1) and was absent in the nontransfected controls (lanes 2 and 4). An indirect IFA was also performed on RPMS-6xMyc-transfected HeLa cells using the RPMS antibody. As shown in Fig. 2B, the RPMS-6xMyc protein was found to be localized in the nucleus as punctate speckles. Comparison of Fig. 2A and B reveals that the chicken anti-RPMS antibody was more effective in IFAs where there was minimal background staining on surrounding nontransfected cells. In Western blotting assays, a number of background cellular proteins were visible in addition to RPMS.

FIG. 2.

RPMS protein expression in transfected cells. (A) Western blot analysis of extracts from HeLa cells transfected with a six-Myc-tagged RPMS expression vector. The RPMS-6xMyc fusion protein band was recognized by both mouse anti-Myc and chicken anti-RPMS polyclonal antibodies (lanes 1 and 3). Nontransfected HeLa cell lysate was included as a control (lanes 2 and 4). The positions of the molecular mass markers are shown on the right. (B) Indirect IFA showing RPMS-6xMyc expression and nuclear localization in transfected HeLa cells. RPMS-6xMyc was detected using chicken anti-RPMS polyclonal antibody and FITC-conjugated donkey anti-chicken IgY.

Interaction of RPMS with CBF1.

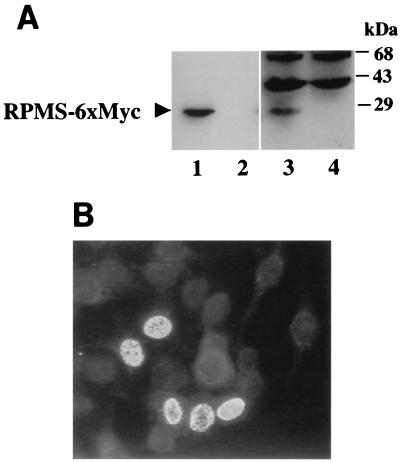

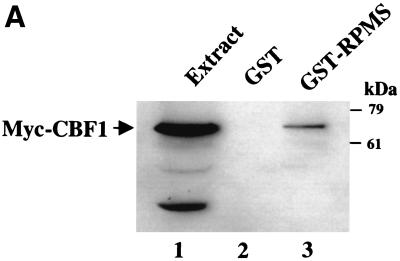

RPMS has previously been shown to bind CBF1 (46). To confirm the interaction between RPMS and CBF1, GST affinity assays and indirect IFAs were performed. In the GST affinity assays (Fig. 3A), Myc-CBF1-transfected HeLa cell extracts were incubated with either control GST protein or GST-RPMS. Bound proteins were detected by Western blotting using mouse anti-Myc antibody. Myc-CBF1 was shown to bind to GST-RPMS (Fig. 3A, lane 3) but not to the control GST (lane 2). The presence of Myc-CBF1 in the extract is shown in lane 1. Additional evidence for an interaction between RPMS and CBF1 was provided by the indirect IFA shown in Fig. 3B. Wild-type CBF1 localizes to the nucleus. However, a mutant of CBF1, CBF1(EEF233AAA), is found in the cytoplasm of transfected cells (S. Zhou and S. D. Hayward, submitted for publication). The difference in intracellular localization of the cytoplasmic CBF1(EEF233AAA) and the nuclear RPMS was used to test for interactions between CBF1 and RPMS. In this assay, a change in localization of one of these two proteins in cotransfected cells would provide evidence for interaction. The intracellular localization of the mutant CBF1(EEF233AAA) and RPMS in individually transfected Vero cells is shown in Fig. 3B (subpanels a and b). The transfected cells were stained with rabbit anti-CBF1 antibody followed by rhodamine-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG or with chicken anti-RPMS primary antibody and FITC-conjugated anti-chicken IgY, respectively. In cotransfected cells in the presence of RPMS, a proportion of CBF1(EEF233AAA) translocated into the nucleus (Fig. 3B, subpanel c), where it showed a similar staining pattern to that of RPMS (Fig. 3B, subpanel d). The ability of the nuclear RPMS protein to relocate mutant CBF1 into the nucleus indicates that interaction between these two proteins can occur not only in vitro but also in the cellular environment.

FIG. 3.

RPMS interacts with CBF1. (A) GST affinity assay using extract from HeLa cells expressing Myc-CBF1. Cell extracts were incubated with control GST beads (lane 2) or GST-RPMS (lane 3). The bound protein was detected by Western blotting using mouse anti-Myc antibody. Lane 1 was loaded with 15 μl of transfected cell extract. (B) Indirect IFA illustrating interaction between CBF1 and RPMS in transfected Vero cells. (a, b) Intracellular localization in singly transfected cells of the CBF1 mutant (EEF233) (a) and RPMS-6xMyc (b). (c, d) Cotransfected cells showing relocalization of CBF1(EEF233) in the presence of RPMS-6xMyc. CBF1(EEF233) (c) becomes predominantly nuclear and assumes a punctate staining pattern resembling that of the cotransfected RPMS-6xMyc (d). CBF1 was detected using anti-CBF1 rabbit antiserum, and RPMS was detected using anti-RPMS chicken antibody.

RPMS interacts with the CBF1 corepressors mSin3A and CIR.

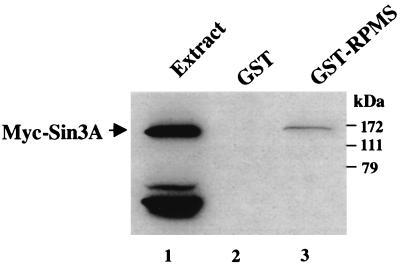

To determine whether RPMS also contacted components of the CBF1 corepressor complex, a GST affinity assay was performed using Myc-Sin3A-transfected HeLa cell extract. Myc-Sin3A bound to GST-RPMS, although the interaction appeared to be relatively weak (Fig. 4, lane 3). There was no binding to control GST (lane 2). The weak binding of Sin3A suggested that this might be an indirect interaction and prompted testing of other corepressor proteins.

FIG. 4.

RPMS interacts with the CBF1 corepressor Sin3A. RPMS interacts with mSin3A, a component of the CBF1 corepressor complex, as demonstrated by a GST affinity assay using cellular extract from HeLa cells transfected with Myc-mSin3A. The Western blot was probed with mouse anti-Myc antibody. Myc-mSin3A bound to GST-RPMS (lane 3) but not to control GST protein (lane 2). Fifteen microliters of Myc-mSin3A-transfected HeLa cell extract was loaded in lane 1.

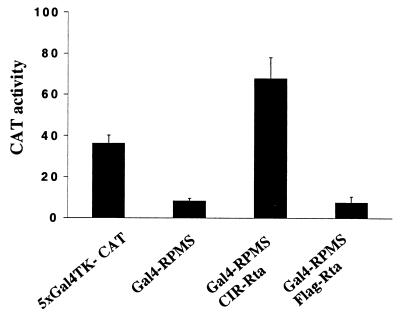

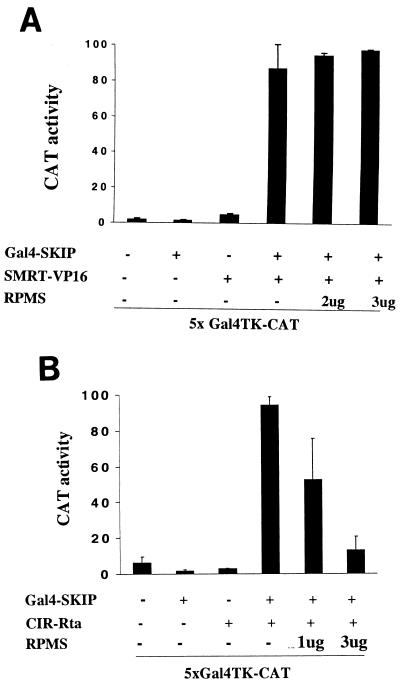

A Gal4DBD-RPMS fusion protein was generated and used in a mammalian two-hybrid assay to examine its interaction with other corepressors (Fig. 5). Cotransfection of the Gal4DBD-RPMS expression plasmid into HeLa cells with a CAT reporter containing five upstream Gal4 binding sites, 5xGal4TK-CAT, led to repression of reporter CAT expression, consistent with an interaction between RPMS and a corepressor complex. When a CIR-Rta fusion protein expression plasmid was cotransfected, CAT activity increased approximately fivefold. This increase was not observed when CIR-Rta was replaced by a Flag-Rta vector control. The activation by CIR-Rta indicates that there is an interaction between RPMS and CIR which brings the transactivation domain of Rta to the reporter promoter, thereby activating reporter expression.

FIG. 5.

RPMS mediates transcriptional repression. Transient-expression assay showing repression of a 5xGal4TK-CAT reporter by cotransfected Gal4DBD-RPMS. Addition of CIR-Rta led to activated CAT expression, indicating an interaction between RPMS and the corepressor CIR that brings the Rta activation domain to the promoter. Gal4-RPMS (1 μg), CIR-Rta (1 μg), or control plasmid SG5-Rta (1 μg) were cotransfected into HeLa cells with the 5xGal4TK-CAT reporter (0.8 μg). Results given are an average of three experiments with the standard deviation indicated.

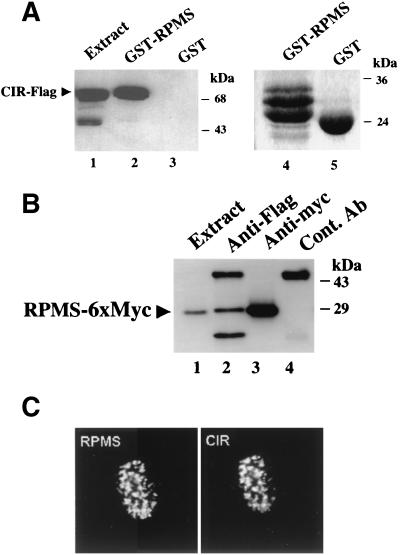

Interaction between RPMS and CIR was further tested by GST affinity and immunoprecipitation assays using extracts from HeLa cells transfected with expression vectors for RPMS-6xMyc and CIR-Flag. In a GST affinity assay (Fig. 6A), extracts of HeLa cells transfected with CIR-Flag were incubated with control GST protein or with GST-RPMS. Bound proteins were analyzed on a Western blot probed with anti-Flag antibody to detected CIR-Flag. CIR-Flag did not bind to control GST (Fig. 6A, lane 3) but bound to GST-RPMS (lane 2). A coimmunoprecipitation assay was also performed using extracts from HeLa cells cotransfected with CIR-Flag and RPMS-6xMyc. Immunoprecipitated proteins were analyzed by Western blotting with anti-Myc antibody (Fig. 6B). RPMS-6xMyc was detected as a coprecipitated protein with CIR-Flag in immunoprecipitates generated with mouse anti-Flag antibody (lane 2) but not in immunoprecipitates generated by using preimmune mouse serum (lane 4). The identity of RPMS-6xMyc was confirmed by direct precipitation using mouse anti-Myc antibody (lane 3).

FIG. 6.

Interaction of RPMS with CIR. (A) GST affinity assay showing binding of CIR-Flag from transfected HeLa cell extracts to GST-RPMS (lane 2) but not to the control GST beads (lane 3). Lane 1 was loaded with 20 μl of CIR-Flag-transfected HeLa cell extract. Bound protein was detected by Western blotting using mouse anti-Flag antibody. Coomassie blue staining of the gel shows that equal amounts of the GST protein were used in this assay (lanes 4 and 5). The GST-RPMS fusion protein migrates as a triplet that includes two specific degradation products. (B) Lysates from HeLa cells cotransfected with CIR-Flag and RPMS-6xMyc were subjected to immunoprecipitation, and the immunoprecipitated proteins were probed with mouse anti-Myc antibody in Western blots to detect RPMS-6xMyc. RPMS-6xMyc coprecipitated with CIR-Flag in anti-Flag immunoprecipitates (lane 2) but not in control immunoprecipitates using preimmune mouse serum (lane 4). RPMS-6xMyc directly immunoprecipitated by anti-Myc antibody was a positive control (lane 3). Lane 1 was loaded with 10 μl of RPMS-6xMyc-transfected HeLa cell extract. (C) Intranuclear colocalization of RPMS and CIR. An IFA in Vero cells cotransfected with RPMS-6xMyc and CIR shows that CIR and RPMS each gave identical punctate nuclear staining patterns. Chicken anti-RPMS or rabbit anti-CIR antibodies were used as primary antibodies and the secondary antibodies were FITC-conjugated donkey anti-chicken IgY and rhodamine-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit IgG.

We next used an indirect IFA to examine the intracellular localization of these two proteins in transfected cells. CIR and RPMS-6xMyc expression vectors were cotransfected into Vero cells and subjected to indirect immunofluorescence staining. CIR was detected with rabbit anti-CIR antibody and rhodamine-conjugated secondary antibody, while RPMS was detected with chicken anti-RPMS antibody and FITC-conjugated secondary antibody. Each of the proteins gave an identical pattern of characteristic punctate spots in the nucleus (Fig. 6C).

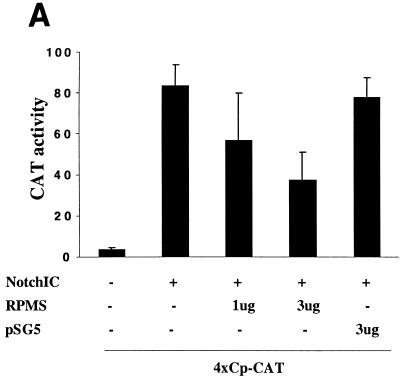

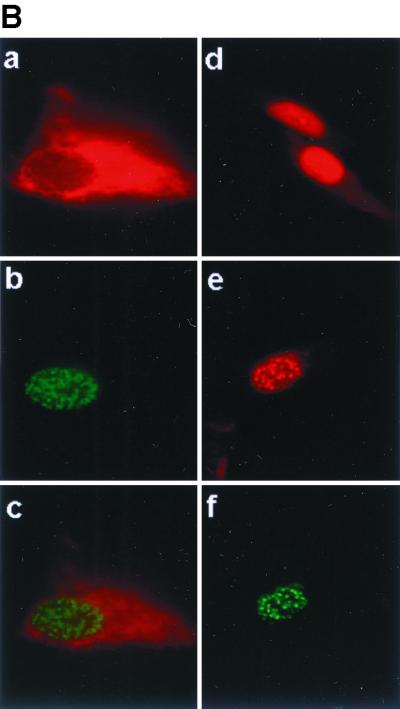

RPMS colocalizes with NotchIC and interferes with NotchIC activity.

RPMS interferes with NotchIC activation in transient-expression assays (46). This observation was confirmed in HeLa cells cotransfected with a 4xCp-CAT reporter, NotchIC, and RPMS (Fig. 7A). NotchIC activated reporter expression, and this function was partially blocked in a dose-responsive manner by addition of RPMS. Addition of control SG5 vector had no effect. Negative transcriptional regulation by RPMS does not occur nonspecifically. For example, cotransfection of RPMS had no effect in reporter assays measuring the SKIP-SMRT interaction (see Fig. 10A) or in assays in which a reporter driven by a viral promoter was activated by other factors such as vSrc (data not shown).

FIG. 7.

RPMS-NotchIC interactions. (A) Transient-expression assay in which HeLa cells were cotransfected with a 4xCp-CAT reporter (1 μg), NotchIC (0.1 μg), and the indicated amount of RPMS. NotchIC activated the CAT reporter. The activation was partially blocked by the addition of RPMS. (In this assay, total transfected DNA was increased with the addition of RPMS, and the separate addition of SG5 vector formed the control). (B) Colocalization of RPMS and NotchIC in transfected Vero cells by an indirect IFA in which transfected cells were stained with rabbit anti-Notch antibody or chicken anti-RPMS antibody. Full-length rat Notch1 is membrane associated and cytoplasmic (a), while RPMS-6xMyc is nuclear (b). This intracellular distribution is maintained in cotransfected cells (c). NotchIC shows a diffuse nuclear staining pattern (d). Cotransfection with RPMS changes the intranuclear distribution of NotchIC (e) to the punctate pattern of RPMS-6xMyc (f).

FIG. 10.

Mechanism of RPMS interference with relief of repression. (A) RPMS does not block the SMRT-SKIP interaction. Mammalian two-hybrid assay in which HeLa cells were cotransfected with a 5xGal4TK-CAT reporter, Gal4DBD-SKIP alone or in the presence of SMRT-VP16, or RPMS as indicated. Total DNA (6 μg) was kept constant for each transfection by using SG5 vector DNA. Addition of SMRT-VP16 activated CAT expression through tethering to the reporter-bound Gal4DBD-SKIP. Addition of RPMS did not prevent this activation. (B) RPMS competes with SKIP for interaction with CIR. Shown are the results of a mammalian two-hybrid assay performed as described for panel A. Cells were transfected with 5xGal4TK-CAT, Gal4DBD-SKIP alone or in the presence of CIR-Rta, or RPMS as indicated. CIR-Rta activated the 5xGal4TK-CAT reporter through its interaction with Gal4DBD-SKIP. This activation was ablated by the addition of RPMS, suggesting that RPMS binding to CIR interferes with the SKIP-CIR interaction.

We next performed IFAs to examine the intracellular localization of Notch and RPMS. Full-length Notch was detected using rabbit anti-Notch antibody and showed cytoplasmic localization in both transfected cells and in cells cotransfected with RPMS (Fig. 7B). NotchIC gave a diffuse nuclear staining pattern (Fig. 7B) in transfected cells. When cotransfected with RPMS, NotchIC formed punctate speckles that colocalized with RPMS (Fig. 7B).

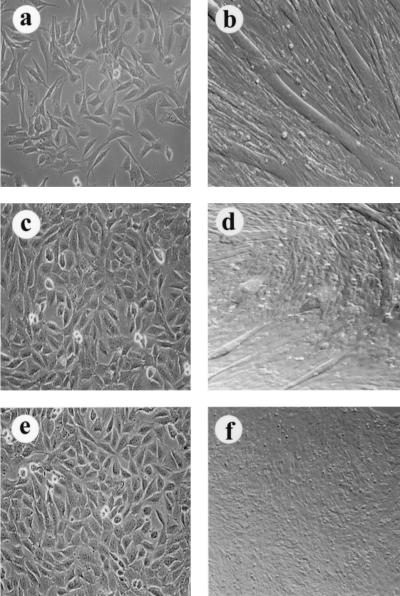

RPMS blocks NotchIC function in a muscle cell differentiation assay.

RPMS interferes with the ability of NotchIC to activate a Cp-CAT reporter (Fig. 7 and reference 46). We wished to extend this observation to determine whether RPMS could also interfere with NotchIC function in a more biologically based assay. In some cell types, activation of Notch signaling delays or prevents differentiation responses (1). This aspect of Notch activity can be assessed in a muscle cell differentiation assay using C2C12 myoblasts. Myogenesis of cultured C2C12 cells is abolished by expression of constitutively activated NotchIC (31, 57). We examined the effect of RPMS on NotchIC function in this assay. As previously described, C2C12 cells grew as a flat monolayer when cultured in medium containing bovine serum, but after 6 days of growth in differentiation medium the cells fused to form myotubes (Fig. 8a and b). A C2C12-derived cell line, CDN2, that constitutively expresses Notch2IC was unable to form multinucleated myotubes in response to the differentiation stimulus and continued to grow as mononuclear cells even after 6 days in differentiation medium (Fig. 8e and f). This behavior is in accordance with previously published results (20, 41). However, CDN2 cells that were stably transfected with an RPMS expression vector had an altered response. The phenotype of these cells in growth medium was identical to that of CDN2 cells (Fig. 8c), but after 6 days in differentiation medium a partial differentiation response was apparent (Fig. 8d). Morphologically distinctive myotubes formed in the RPMS-transfected CDN2 cell cultures, although these structures were smaller and less well aligned than the myotubes formed by C2C12 cells. The ability of RPMS to partially overcome Notch2IC activity in this assay complements the data obtained in the reporter assays and strongly reinforces the conclusion that RPMS can act as a negative regulator of Notch activity.

FIG. 8.

RPMS blocks NotchIC function in a muscle cell differentiation assay. Shown are photomicrographs of C2C12 myoblasts (a, b), the C2C12-derived cell line CDN2, which constituitively expresses Notch2IC (e, f), and CDN2 cells stably transfected with RPMS (c, d), in growth medium (a, c, and e) and 6 days after transfer into differentiation medium (b, d, and f). (a, b) C2C12 cells form myotubes in response to the differentiation stimulus. (e, f) Differentiation of CDN2 cells is blocked by Notch2IC. (c, d) RPMS interferes with Notch2IC activity allowing myotube formation.

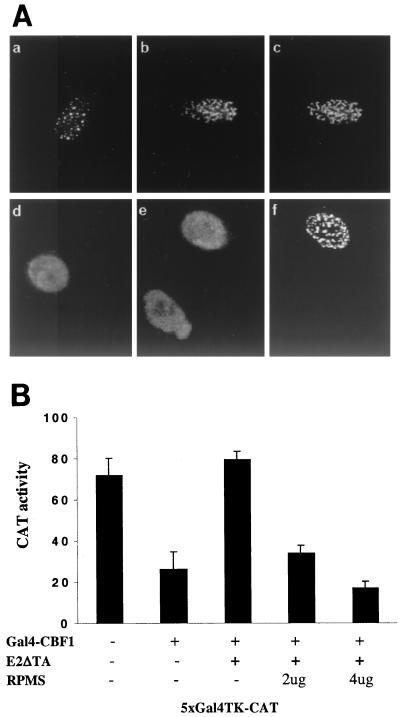

RPMS colocalizes with EBNA2 and interferes with EBNA2 activity.

RPMS has also been reported to interfere with EBNA2 transactivation of a Cp-CAT reporter in transient-expression assays (46). To confirm that the intracellular localization of RPMS and EBNA2 was consistent with such activity, an IFA was performed on Vero cells cotransfected with EBNA2 and RPMS. In this assay, EBNA2 was detected using mouse anti-EBNA2 antibody and a rhodamine-conjugated secondary antibody. EBNA2 gave characteristic punctate spots in the nucleus of singly transfected Vero cells, and the EBNA2 spots colocalized with the RPMS punctate spots in cotransfected cells (Fig. 9A). Cotransfection of RPMS with an EBV Zta expression plasmid was included as a control. The diffuse nuclear staining exhibited by Zta in singly transfected Vero cells was not altered by cotransfection with RPMS, which also maintained its characteristic punctate staining pattern in the dually transfected cells (Fig. 9A).

FIG. 9.

RPMS-EBNA2 interactions. (A) Indirect IFA showing colocalization of RPMS with EBNA2 in cotransfected Vero cells with EBNA2 single transfection (a), or cotransfected cells stained for EBNA2 (b) or RPMS-6xMyc (c). (d to f) Cells transfected with a control unrelated nuclear protein, Zta. Zta gave a diffuse intranuclear localization in both singly (d) and cotransfected (e) cells. RPMS retained its punctate distribution in cotransfected cells (f). (B) RPMS prevents relief of CBF1-mediated repression by EBNA2. Transient-expression assay in which HeLa cells were cotransfected with a 5xGal4TK-CAT reporter plus Gal4DBD-CBF1, E2ΔTA, or RPMS as indicated. The addition of E2ΔTA relieved CBF1-mediated repression of reporter expression. This effect of E2ΔTA was blocked by RPMS. TK-LUC was included in each reaction as a control for transfection efficiency. Results shown are a mean of three experiments with the standard deviation indicated.

To further examine the mechanism of RPMS interference with EBNA2 transactivation, a transient-expression assay was performed. HeLa cells were cotransfected with Gal4DBD-CBF1, a 5xGal4TK-CAT reporter, and E2ΔTA, which expresses an EBNA2 protein that has the transcriptional activation domain deleted but retains the CBF1 interaction domain. Gal4-CBF1 repressed CAT expression, and this repression was relieved by the addition of E2ΔTA as has been previously described (18). However, RPMS interfered with the ability of E2ΔTA to relieve CBF1-mediated repression (Fig. 9B).

RPMS competes with SKIP for binding to CIR.

SKIP is a component of the CBF1-corepressor complex and is an important cofactor for both EBNA2 and NotchIC activation of CBF1-repressed promoters (60, 61). We tested for interaction between RPMS and SKIP in both GST affinity and mammalian two-hybrid assays but could find no evidence for any interaction (data not shown). The interaction between SKIP and SMRT is important in tethering the HDAC corepressor complex to CBF1. We used a mammalian two-hybrid assay to examine whether RPMS had any effect on the SKIP-SMRT interaction. HeLa cells were cotransfected with a 5xGal4TK-CAT reporter, Gal4DBD-SKIP, and SMRT-VP16 in the presence or absence of RPMS (Fig. 10A). Gal4DBD-SKIP repressed basal reporter gene expression as previously described (61). Cotransfection of SMRT-VP16 with the reporter led to a small activation of expression through the nonspecific effects of the VP16 activation domain. Cotransfection of SMRT-VP16 in the presence of Gal4DBD-SKIP allowed specific tethering of the VP16 activation domain to the promoter through the SKIP-SMRT interaction and resulted in strong activation of CAT expression. Addition of RPMS had no deleterious effect on this SMRT-VP16-mediated activation, implying that the SKIP-SMRT interaction was not targeted by RPMS.

We next performed a mammalian two-hybrid assay to examine whether the interaction between SKIP and CIR could be competed by RPMS. HeLa cells were cotransfected with a 5xGal4TK-CAT reporter, Gal4DBD-SKIP, and CIR-Rta in the presence or absence of RPMS (Fig. 10B). Gal4DBD-SKIP repressed reporter expression as previously shown (Fig. 10A) (61). Addition of CIR-Rta increased reporter expression through CIR interaction with the promoter-bound SKIP and the associated tethering of the fused Rta transcriptional activation domain onto the promoter. Cotransfection of RPMS with CIR-Rta severely impaired the ability of CIR-Rta to mediate reporter activation. This result is interpreted to indicate that RPMS can outcompete SKIP for binding to CIR.

DISCUSSION

The BART family of transcripts has been found to be expressed in latently infected lymphoblastoid cell lines in culture, on primary in vitro infection of peripheral blood mononuclear cells, in latently infected B cells isolated from peripheral blood, and in EBV-associated tumor cells of both lymphoid and epithelial origin (2, 4–7, 11, 27, 44, 51, 56). This widespread pattern of expression implies that BARTs contribute to EBV latency and possibly also to viral tumorigenesis. A first step in evaluating the role of the BARTs in EBV biology was taken with the identification of ORFs within individual BART transcripts, and this has paved the way for characterization of the encoded proteins. The transcript encoding the RPMS1 ORF is the only one to date that has been isolated as an intact cDNA. This particular BART appears to be the most abundant of the BARTs in the C15 NPC xenograft (46) and to be commonly expressed. Using RT-PCR analyses, we had previously found that transcripts with the splicing pattern that gives rise to the RPMS1 ORF were present in latently infected peripheral blood B cells, and we have now shown that RPMS-encoding transcripts are also expressed in most cultured B-cell lines, in the NPC-derived 666 cell line, and in Hodgkin's disease tissues.

The Notch signaling pathway is an essential developmental pathway which dictates cell fate decisions by influencing differentiation, proliferation, and apoptotic programs (1, 38). The central nature of this pathway to EBV latency and immortalization became clear with the realization that the nuclear downstream effector of activated Notch, CBF1, is targeted by the EBNA2 and EBNA3A, -3B, and -3C latency proteins and indirectly, through EBNA2, by EBNA-LP. This extraordinary focus on CBF1 highlights not only the importance of the Notch pathway to EBV biology but also the apparent need for finely modulated control of those genes whose expression is regulated through CBF1. The EBNA2, EBNA3 family, and EBNA-LP proteins are expressed on primary infection of B cells and in latently infected lymphoblastoid cell lines, but they are not expressed in EBV-associated tumors other than in a subset of B-cell lymphomas arising in immunocompromised patients. The BARTs are synthesized in all EBV-associated tumors and the particular transcript with the splicing pattern that generates the RPMS1 ORF has been detected in the C15 NPC xenograft (44, 46, 47) and in our study in the tumor-derived 666 epithelial cell line and in primary Hodgkin's disease specimens. Characterization of RPMS function now expands the settings in which EBV-encoded proteins interface with the Notch signaling pathway.

RPMS has previously been noted to interact with CBF1 in GST affinity and yeast two-hybrid assays (46), and we confirmed and expanded this observation to show interaction in transfected mammalian cells. Advantage was taken of a CBF1 mutant that, unlike the wild-type protein, localizes in the cytoplasm of transfected cells. RPMS was able to redirect mutant CBF1 into the nucleus, where CBF1 assumed the punctate distribution of the cotransfected RPMS. The demonstration that targeting of RPMS to a promoter as a Gal4-RPMS fusion resulted in transcriptional repression raised the possibility of additional interactions between RPMS and the CBF1-associated corepressor complex. An extensive series of protein-protein interaction assays confirmed that such contacts take place and identified the corepressor CIR as the partner with which RPMS appeared to bind most tightly. CIR was originally identified in a yeast two-hybrid screen as a CBF1 binding protein and was shown to link CBF1 to the Sin3-HDAC corepressor complex (21). A CBF1 mutant that is unable to mediate transcriptional repression exhibits a correlative loss of binding to CIR. The strength of the CIR-RPMS interaction relative to the interactions between RPMS and CBF1 and the other corepressors tested suggests that CIR is the dominant contact point for RPMS in the complex.

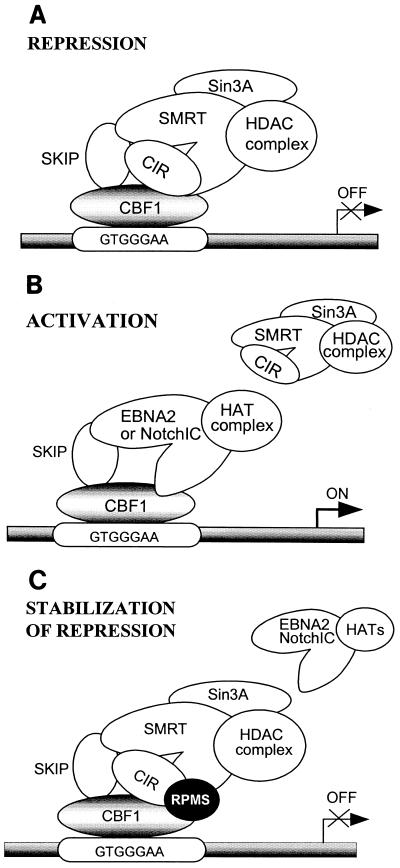

RPMS counters EBNA2 and NotchIC activation of CBF1-repressed promoters, as has been reported previously (46) and demonstrated here. We believe that this outcome stems from the RPMS-CIR interaction. Overcoming CBF1 transcriptional repression is a bipartite process that involves abolishing repression by displacement of the HDAC-associated corepressor complex from CBF1, followed by a transcriptional activation step mediated by the activation domains of the CBF1-bound EBNA2 or NotchIC proteins. The use of an EBNA2 variant with a deletion of the transcriptional activation domain allowed us to separate these two steps and demonstrate that RPMS prevents relief of CBF1-mediated repression. This may be achieved by preventing EBNA2 or NotchIC displacement of the corepressor complex, either by strengthening attachment of the corepressor complex to CBF1 or by interfering with contacts that must be made by EBNA2 and NotchIC to effect corepressor displacement. SKIP is a CBF1 interactor that appears to be a key swivel protein in the conversion of transcriptional repression to activation (60, 61). We could detect no interaction between SKIP and RPMS, but RPMS did appear to differentially affect SKIP interactions with other corepressors. SKIP interaction with the corepressor SMRT was not inhibited, and was possibly even facilitated, by RPMS. In contrast the SKIP-CIR interaction was ablated by RPMS. One interpretation of these experiments is that changing the SKIP-CIR interaction in some way disadvantages the EBNA2-SKIP–NotchIC-SKIP interaction and prevents a stable association of EBNA2 or NotchIC with CBF1 (Fig. 11).

FIG. 11.

CBF1-mediated promoter regulation pictorial model. (A) Default state of promoter repression that is mediated by CBF1 association with an SMRT-HDAC complex that deacetylates histones and contributes to transcriptional repression by transcription factor exclusion (21, 26). (B) Promoter activation occurs when EBV EBNA2 or cellular NotchIC displaces the SMRT-HDAC complex from its CBF1 and SKIP anchoring points (60). Activation results from a combination of relief of repression (18, 61) and histone acetylation mediated by the EBNA2- and NotchIC-associated coactivator complexes (24, 32, 55). (C) Stabilization of repression, a state generated through RPMS interaction with the corepressor CIR. This interaction apparently precludes effective displacement of the SMRT-HDAC repression complex by EBNA2 and NotchIC.

The ability of RPMS to overcome NotchIC function in a muscle cell differentiation assay encourages our belief that the effects of RPMS seen in the protein-protein interaction and transient-expression assays are biologically relevant. In vitro immortalization of peripheral blood mononuclear cells is routinely achieved with the B95-8 strain of EBV, which lacks an intact RPMS1 ORF, and deletion of the entire BamHI-A region does not prevent in vitro B cell immortalization (28, 43). These observations imply that, in the B cell, RPMS function is less vital in vitro than in vivo. Lymphopoiesis was dramatically perturbed in mice reconstituted with bone marrow that had been modified for constitutive Notch1IC expression, and these mice showed an early-stage block in B-cell maturation (42). Stimulation of Notch signaling in CD34 bone marrow stem cells accelerated progression through G1 and delayed differentiation (3). EBV establishes latency in vivo in resting memory B cells (39, 40). Maintainace of long-term latency may be best served by limiting the degree to which the pool of infected memory B cells responds to proliferative signals. Work in Drosophila has shown that Notch developmental and proliferative effects are extremely sensitive to dosage (1), and thus the ability of RPMS to modulate Notch signaling in memory B cells may be an important factor for persistent, life-long infection.

The consistent detection of BARTs in EBV-associated tumors also raises the possibility of a contribution of BARTs and of RPMS to tumorigenesis. Two separate roles can be considered. First is the modulation of Notch activity in the sense of a controlling brake on the Notch accelerator; in this scenario RPMS would serve analagously to EBNA3A and -3C in their capacity to modulate EBNA2 activity through competition for CBF1 binding (25, 54, 59). Secondly, in the case of EBV-associated epithelial tumors, a direct contribution through inhibition of Notch function can be considered. Unlike many cell types where Notch signaling has proliferative effects and delays differentiation, Notch has been found to promote differentiation responses in epithelial cells (37). Thus, in this setting antagonism of Notch activity by RPMS would favor proliferation.

The realization that the BARTs encode proteins that interact with Notch extends the situations in which EBV manipulates the Notch signaling pathway beyond those in which the EBNA2 and EBNA3 family proteins are expressed, and it further emphasizes the central role of the Notch pathway in EBV biology.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank M. Borowitz and R. Ambinder for the samples of Hodgkin's disease tissue which were obtained under the auspices of P01 CA69266, D. Huang for 666 cells, and C. Laherty and R. Evans for generous gifts of mSin3A and SMRT plasmids. We gratefully acknowledge M. Fujimuro for assistance with coimmunoprecipitation assays and F. Chang for manuscript preparation.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants RO1 CA42245 to S.D.H. and RO1 NS31885 to G.W.

REFERENCES

- 1.Artavanis-Tsakonas S, Rand M D, Lake R J. Notch signaling: cell fate control and signal integration in development. Science. 1999;284:770–776. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5415.770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brooks L A, Lear A L, Young L S, Rickinson A B. Transcripts from the Epstein-Barr virus BamHI A fragment are detectable in all three forms of virus latency. J Virol. 1993;67:3182–3190. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.6.3182-3190.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carlesso N, Aster J C, Sklar J, Scadden D T. Notch1-induced delay of human hematopoietic progenitor cell differentiation is associated with altered cell cycle kinetics. Blood. 1999;93:838–848. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen H, Smith P, Ambinder R F, Hayward S D. Expression of Epstein-Barr virus BamHI-A rightward transcripts (BARTs) in latently infected B cells from peripheral blood. Blood. 1999;93:3026–3032. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen H-L, Lung M M L, Sham J S T, Choy D T K, Griffin B E, Ng M H. Transcription of BamHI-A region of the EBV genome in NPC tissues and B cells. Virology. 1992;191:193–201. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(92)90181-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chiang A K, Tao Q, Srivastava G, Ho F C. Nasal NK- and T-cell lymphomas share the same type of Epstein-Barr virus latency as nasopharyngeal carcinoma and Hodgkin's disease. Int J Cancer. 1996;68:285–290. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19961104)68:3<285::AID-IJC3>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deacon E M, Pallesen G, Niedobitek G, Crocker J, Brooks L, Rickinson A B, Young L S. Epstein-Barr virus and Hodgkin's disease: transcriptional analysis of virus latency in the malignant cells. J Exp Med. 1993;177:339–349. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.2.339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.De Strooper B, Annaert W, Cupers P, Saftig P, Craessaerts K, Mumm J S, Schroeter E H, Schrijvers V, Wolfe M S, Ray W J, Goate A, Kopan R. A presenilin-1-dependent γ-secretase-like protease mediates release of Notch intracellular domain. Nature. 1999;398:518–522. doi: 10.1038/19083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fortini M E, Rebay I, Caron L A, Artavanis-Tsakonas S. An activated Notch receptor blocks cell-fate commitment in the developing Drosophila eye. Nature. 1993;365:555–557. doi: 10.1038/365555a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fries K L, Sculley T B, Webster-Cyriaque J, Rajadurai P, Sadler R H, Raab-Traub N. Identification of a novel protein encoded by the BamHI A region of the Epstein-Barr virus. J Virol. 1997;71:2765–2771. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.4.2765-2771.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gilligan K, Sato H, Rajadural P, Busson P, Young L, Rickinson A, Tursz T, Raab-Traub N. Novel transcription from the Epstein-Barr virus terminal EcoRI fragment, DIJhet, in a nasopharyngeal carcinoma. J Virol. 1990;64:4948–4956. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.10.4948-4956.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gilligan K J, Rajadurai P, Lin J C, Busson P, Abdel-Hamid M, Prasad U, Tursz T, Raab-Traub N. Expression of the Epstein-Barr virus BamHI A fragment in nasopharyngeal carcinoma: evidence for viral protein expressed in vivo. J Virol. 1991;65:6252–6259. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.11.6252-6259.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Greenwald I. Lin-12/Notch signaling: lessons from worms and flies. Genes Dev. 1998;12:1751–1762. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.12.1751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grossman S R, Johannsen E, Tong X, Yalamanchili R, Kieff E. The Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen 2 transactivator is directed to response elements by the Jκ recombination signal binding protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:7568–7572. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.16.7568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hayward S D. Immortalization by Epstein-Barr virus: focusing on the Notch signaling pathway. EBV Rep. 1999;6:151–157. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Henkel T, Ling P D, Hayward S D, Peterson M G. Mediation of Epstein-Barr virus EBNA2 transactivation by recombination signal-binding protein Jκ. Science. 1994;265:92–95. doi: 10.1126/science.8016657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hitt M M, Allday M, Hara T, Karran L, Jones M D, Busson P, Tursz T, Ernberg I, Griffin B. EBV gene expression in an NPC-related tumor. EMBO J. 1989;8:2639–2651. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb08404.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hsieh J J-D, Hayward S D. Masking of the CBF1/RBPJκ transcriptional repression domain by Epstein-Barr virus EBNA2. Science. 1995;268:560–563. doi: 10.1126/science.7725102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hsieh J J-D, Henkel T, Salmon P, Robey E, Peterson M G, Hayward S D. Truncated mammalian Notch1 activates CBF1/RBPJκ-repressed genes by a mechanism resembling that of Epstein-Barr virus EBNA2. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:952–959. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.3.952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hsieh J J-D, Nofziger D E, Weinmaster G, Hayward S D. EBV immortalization: Notch2 interacts with CBF1 and blocks differentiation. J Virol. 1997;71:1938–1945. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.3.1938-1945.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hsieh J J-D, Zhou S, Chen L, Young D B, Hayward S D. CIR, a corepressor linking the DNA binding factor CBF1 to the histone deacetylase complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:23–28. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.1.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hui A B, Cheung S T, Fong Y, Lo K W, Huang D P. Characterization of a new EBV-associated nasopharyngeal carcinoma cell line. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 1998;101:83–88. doi: 10.1016/s0165-4608(97)00231-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jarriault S, Brou C, Logeat F, Schroeter E H, Kopan R, Israel A. Signalling downstream of activated mammalian Notch. Nature. 1995;377:355–358. doi: 10.1038/377355a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jayachandra S, Low K G, Thlick A E, Yu J, Ling P D, Chang Y, Moore P S. Three unrelated viral transforming proteins (vIRF, EBNA2, and E1A) induce the MYC oncogene through the interferon-responsive PRF element by using different transcription coadaptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:11566–11571. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.20.11566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 25.Johannsen E, Miller C L, Grossman S R, Kieff E. EBNA-2 and EBNA-3C extensively and mutually exclusively associate with RBPJκ in Epstein-Barr virus-transformed B lymphocytes. J Virol. 1996;70:4179–4183. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.6.4179-4183.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kao H-Y, Ordentlich P, Koyano-Nakagawa N, Tang Z, Downes M, Kintner C R, Evans R M, Kadesch T. A histone deacetylase corepressor complex regulates the Notch signal transduction pathway. Genes Dev. 1998;12:2269–2277. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.15.2269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Karran L, Gao Y, Smith P R, Griffin B E. Expression of a family of complementary-strand transcripts in Epstein-Barr virus-infected cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:8058–8062. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.17.8058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kempkes B, Pich D, Zeidler R, Sugden B, Hammerschmidt W. Immortalization of human B lymphocytes by a plasmid containing 71 kilobase pairs of Epstein-Barr virus DNA. J Virol. 1995;69:231–238. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.1.231-238.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kienzle N, Buck M, Greco S, Krauer K, Sculley T B. Epstein-Barr virus-encoded RK-BARF0 protein expression. J Virol. 1999;73:8902–8906. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.10.8902-8906.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kienzle N, Sculley T B, Poulsen L, Buck M, Cross S, Raab-Traub N, Khanna R. Identification of a cytotoxic T-lymphocyte response to the novel BARF0 protein of Epstein-Barr virus: a critical role for antigen expression. J Virol. 1998;72:6614–6620. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.8.6614-6620.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kopan R, Nye J S, Weintraub H. The intracellular domain of mouse Notch: a constitutively activated repressor of myogenesis directed at the basic helix-loop-helix region of MyoD. Development. 1994;120:2385–2396. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.9.2385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kurooka H, Honjo T. Functional interaction between the mouse notch1 intracellular region and histone acetyltransferases PCAF and GCN5. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:17211–17220. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M000909200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Laherty C D, Billin A N, Lavinsky R M, Yochum G S, Bush A C, Sun J-M, Mullen T-M, Davie J R, Rose D W, Glass C K, Rosenfeld M G, Ayer D E, Eisenman R N. SAP30, a component of the mSin3 corepressor complex involved in N-CoR-mediated repression by specific transcription factors. Mol Cell. 1998;2:33–42. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80111-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lieber T, Kidd S, Alcamo E, Corbin V, Young M W. Antineurogenic phenotypes induced by truncated Notch proteins indicate a role in signal transduction and may point to a novel function for Notch in nuclei. Genes Dev. 1993;7:1949–1965. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.10.1949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ling P D, Rawlins D R, Hayward S D. The Epstein-Barr virus immortalizing protein EBNA-2 is targeted to DNA by a cellular enhancer-binding protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:9237–9241. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.20.9237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ling P D, Ryon J J, Hayward S D. EBNA-2 of herpesvirus papio diverges significantly from the type A and type B EBNA-2 proteins of Epstein-Barr virus but retains an efficient transactivation domain with a conserved hydrophobic motif. J Virol. 1993;67:2990–3003. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.6.2990-3003.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lowell S, Jones P, Le Roux I, Dunne J, Watt F M. Stimulation of human epidermal differentiation by delta-notch signalling at the boundaries of stem-cell clusters. Curr Biol. 2000;10:491–500. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00451-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Miele L, Osborne B. Arbiter of differentiation and death: Notch signaling meets apoptosis. J Cell Physiol. 1999;181:393–409. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(199912)181:3<393::AID-JCP3>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Miyashita E M, Yang B, Babcock G J, Thorley-Lawson D A. Identification of the site of Epstein-Barr virus persistence in vivo as a resting B cell. J Virol. 1997;71:4882–4891. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.7.4882-4891.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Miyashita E M, Yang B, Lam K M, Crawford D H, Thorley-Lawson D A. A novel form of Epstein-Barr virus latency in normal B cells in vivo. Cell. 1995;80:593–601. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90513-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nofziger D, Miyamoto A, Lyons K M, Weinmaster G. Notch signaling imposes two distinct blocks in the differentiation of C2C12 myoblasts. Development. 1999;126:1689–1702. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.8.1689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pui J C, Allman D, Xu L, DeRocco S, Karnell F G, Bakkour S, Lee J Y, Kadesch T, Hardy R R, Aster J C, Pear W S. Notch1 expression in early lymphopoiesis influences B versus T lineage determination. Immunity. 1999;11:299–308. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80105-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Robertson E S, Tomkinson B, Kieff E. An Epstein-Barr virus with a 58-kilobase-pair deletion that includes BARF0 transforms B lymphocytes in vitro. J Virol. 1994;68:1449–1458. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.3.1449-1458.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sadler R H, Raab-Traub N. Structural analyses of the Epstein-Barr virus BamHI A transcripts. J Virol. 1995;69:1132–1141. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.2.1132-1141.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schroeter E H, Kisslinger J A, Kopan R. Notch-1 signalling requires ligand-induced proteolytic release of intracellular domain. Nature. 1998;393:382–386. doi: 10.1038/30756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Smith P R, de Jesus O, Turner D, Hollyoake M, Karstegl C E, Griffin B E, Karran L, Wang Y, Hayward S D, Farrell P J. Structure and coding content of CST (BART) family RNAs of Epstein-Barr virus. J Virol. 2000;74:3082–3092. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.7.3082-3092.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Smith P R, Gao Y, Karran L, Jones M D, Snudden D, Griffin B E. Complex nature of the major viral polyadenylated transcripts in Epstein-Barr virus-associated tumors. J Virol. 1993;67:3217–3225. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.6.3217-3225.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Struhl G, Adachi A. Nuclear access and action of Notch in vivo. Cell. 1998;93:649–660. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81193-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Struhl G, Fitzgerald K, Greenwald I. Intrinsic activity of the Lin-12 and Notch intracellular domains in vivo. Cell. 1993;74:331–345. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90424-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Struhl G, Greenwald I. Presenilin is required for activity and nuclear access of Notch in Drosophila. Nature. 1999;398:522–525. doi: 10.1038/19091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sugiura M, Imai S, Tokunaga M, Koizumi S, Uchizawa M, Okamoto K, Osato T. Transcriptional analysis of Epstein-Barr virus gene expression in EBV-positive gastric carcinoma: unique viral latency in the tumor cells. Br J Cancer. 1996;74:625–631. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1996.412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tomkinson B, Robertson E, Kieff E. Epstein-Barr virus nuclear proteins EBNA-3A and EBNA-3C are essential for B-lymphocyte growth transformation. J Virol. 1993;67:2014–2025. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.4.2014-2025.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Waltzer L, Logeat F, Brou C, Israel A, Sergeant A, Manet E. The human Jκ recombination signal sequence binding protein (RBP-Jκ) targets the Epstein-Barr virus EBNA2 protein to its DNA responsive elements. EMBO J. 1994;13:5633–5638. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06901.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Waltzer L, Perricaudet M, Sergeant A, Manet E. Epstein-Barr virus EBNA3A and EBNA3C proteins both repress RBP-Jκ-EBNA2-activated transcription by inhibiting the binding of RBP-Jκ to DNA. J Virol. 1996;70:5909–5915. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.9.5909-5915.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang L, Grossman S R, Kieff E. Epstein-Barr virus nuclear protein 2 interacts with p300, CBP, and PCAF histone acetyltransferases in activation of the LMP1 promoter. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:430–435. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.1.430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Webster-Cyriaque J, Raab-Traub N. Transcription of Epstein-Barr virus latent cycle genes in oral hairy leukoplakia. Virology. 1998;248:53–65. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Weinmaster G. The ins and outs of Notch signaling. Mol Cell Neurosci. 1997;9:91–102. doi: 10.1006/mcne.1997.0612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ye Y, Lukinova N, Fortini M E. Neurogenic phenotypes and altered Notch processing in Drosophila Presenilin mutants. Nature. 1999;398:525–529. doi: 10.1038/19096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhao B, Marshall D R, Sample C E. A conserved domain of the Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigens 3A and 3C binds to a discrete domain of Jκ. J Virol. 1996;70:4228–4236. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.7.4228-4236.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhou S, Fujimuro M, Hsieh J J, Chen L, Hayward S D. A role for SKIP in EBNA2 activation of CBF1-repressed promoters. J Virol. 2000;74:1939–1947. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.4.1939-1947.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhou S, Fujimuro M, Hsieh J J-D, Chen L, Miyamoto A, Weinmaster G, Hayward S D. SKIP, a CBF1-associated protein, interacts with the ankyrin repeat domain of NotchIC to facilitate NotchIC function. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:2400–2410. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.7.2400-2410.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zimber-Strobl U, Strobl L J, Meitinger C, Hinrichs R, Sakai T, Furukawa T, Honjo T, Bornkamm G W. Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen 2 exerts its transactivating function through interaction with recombination signal binding protein RBP-J kappa, the homologue of Drosophila Suppressor of Hairless. EMBO J. 1994;13:4973–4982. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06824.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]