Abstract

Objectives

Diabetic neuropathy is a traditional and one of the most prevalent complications of diabetes mellitus. The exact pathophysiology of diabetic neuropathy is not fully understood. However, oxidative stress and inflammation are proven to be one of the major underlying mechanisms of neuropathy which is described in detail. Gut dysbiosis is being studied for various neurological disorders and its impact on diabetic neuropathy is also explained. Diabetic neuropathy also causes loss in an individual’s quality of life and one such adverse event is cognitive dysfunction. The interrelation between the neuropathy, cognitive dysfunction and gut is reviewed.

Methods

The exact mechanism is not understood but several hypotheses, cross-sectional studies and systematic reviews suggest a relationship between cognition and neuropathy. The review has collected data from various review and research publications that justifies this inter-relationship.

Results

The multifactorial etiology and pathophysiology of diabetic neuropathy is described with special emphasis on the role of gut dysbiosis. There might exist a correlation between the neuropathy and cognitive impairment caused simultaneously in diabetic patients.

Conclusions

This review summarizes the relationship that might exist between diabetic neuropathy, cognitive dysfunction and the impact of disturbed gut microbiome on its development and progression.

Keywords: Diabetic neuropathy, Cognitive impairment, Oxidative stress, Inflammation, Gut microbiome, Gut dysbiosis

Introduction

Diabetes mellitus is a heterogeneous metabolic disorder characterised by elevated levels of blood glucose for a prolonged period. The broad classification of diabetes mellitus is Type 1 diabetes mellitus (TIDM) and Type 2 diabetes mellitus(T2DM). TIDM, also known as Juvenile diabetes is caused due to destruction of β cells in the pancreas, thereby rendering them incapable of producing insulin. The major type of diabetes is T2DM caused due to impaired insulin signalling or insulin resistance [1].

In accordance with the International Diabetes Federation (IDF), 537 million adults have been diagnosed with DM and 240 million people are estimated to be living with undiagnosed diabetes mellitus. The incidence of DM is expected to cross 643 million by 2030 [2].

The global scenario of diabetes has increased the development of diabetic complications. Among the various traditional and emerging complications of diabetes, an assortment of clinical syndromes characterised by neuronal damage is one of the most prevalent, known as the diabetic neuropathy [3].

Diabetic neuropathy, once commenced affects the neurons in both the peripheral and central nervous system (commonly called diabetic encephalopathy) but distal symmetric peripheral neuropathy remains the most prevalent of the diagnosed neuropathies [4]. The intensity and anatomical location of nerve damage is extremely diversified. Hence, most cases of diabetic neuropathy remain largely undiagnosed. Among the 50% of patients who are estimated to have diabetic neuropathy, around 15–25% present with painful diabetic neuropathy [5].

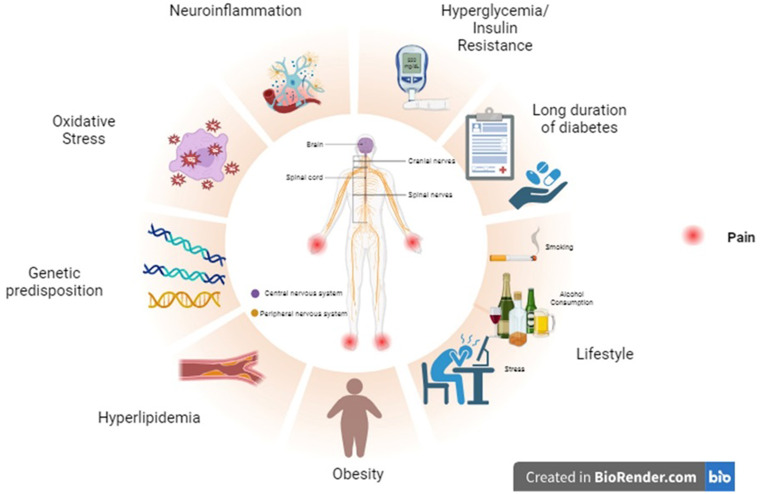

Etiology and risk factors of diabetic neuropathy (Fig. 1)

Fig. 1.

Risk factors of Diabetic neuropathy. Diabetic neuropathy results from a series and simultaneous occurrences of certain factors. Most of the risk factors are modifiable and hence it becomes important for the patients and the healthcare professionals to pay attention to these factors in diabetic patients

Hyperglycemia: Consistent high levels of glucose in the bloodstream can be toxic to the cells in general. So, when neurons are continuously exposed to abnormal levels of glucose, it can result in irreversible nerve damage. This results in impaired functioning of the physiological signaling of neurons [6].

Dyslipidemia/ Hyperlipidemia: Abnormal levels of cholesterol, triglycerides, LDL (Low-density lipoproteins) and HDL (High-density lipoproteins), can result in accumulation lipids in cells. These accumulations can further exacerbate the nerve damage primarily caused due to hyperglycemia. The accumulated lipids, especially the cholesterol can impair the myelin sheath present in the nerve tissue [7, 8].

Insulin resistance: Hyperglycemia and hyperlipidemia are known to cause insulin resistance by inhibiting the normal metabolic insulin signaling, which results in decreased sensitivity to insulin receptors. The increased insulin resistance further causes hyperglycemia, thus making it a continuous cycle and resulting in neuronal damage [9, 10].

Oxidative stress: Impairment of normal metabolic pathways due to hyperglycemia, hyperlipidemia etc., can result in activation of various oxidative pathways and downregulation of anti-oxidant enzymes. Some of the important pathways that lead to oxidative stress are the polyol pathway, advanced end glycation products (AGEs- HbA1c is one important biomarker), hexosamine pathway, auto-oxidation of glucose and protein kinase C (PKC) pathway [11, 12].

Genetic predisposition: A systematic review and meta-analysis by Zhao et al., provided substantial evidence that states polymorphisms in ACE I/D (ACE is an important component of the Renin Angiotensin Aldosterone System, where the presence of D allele is known to increase the occurrence of diabetic neuropathy), MTHFR 1298 A/C (Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase is an important enzyme in the homocysteine metabolism), GPx-1 rs1050450 (GPx is a gene coding for glutathione peroxidase anti-oxidant enzyme), and CAT‐262 C/T (Catalase decomposes hydrogen peroxide in the body, polymorphism in T allele is linked with increased diabetic neuropathy susceptibility) is linked with increased vulnerability to diabetic neuropathy [13].

Neuroinflammation: Hyperglycaemia can trigger chronic inflammation in the body by activating various inflammatory and pro-inflammatory mediators. These inflammatory processes within the nervous system cause nerve damage. Inflammation also causes activation of microglial cells in the nervous system which releases cytokines in the body. These cytokines are suspected to cause pain sensation in neuropathy [14, 15].

Prolonged duration of diabetes: Diabetic patients having the disorder for greater than 10 years have an increased possibility of developing diabetic neuropathy [16, 17].

Lifestyle and environmental factors: Sedentary lifestyle, obesity, smoking, alcohol consumption, diet rich in fat and sugar, stress, environmental factors (certain chemicals and heavy metals) and Vitamin B deficiency can also act as a promoter of diabetic neuropathy [18, 19].

Pathophysiology of diabetic neuropathy

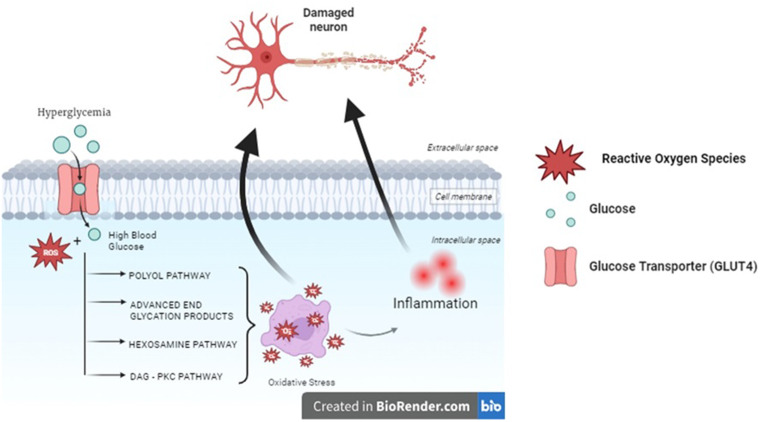

Preclinical and clinical studies indicate that poor glycemic control and a decrease in the insulin sensitivity by the receptors is one of the major factors contributing to diabetic neuropathy which ultimately leads to changes in the biochemical and structural features of the nerve. The exact pathophysiological mechanism through which diabetes causes neuropathic pain is not fully elucidated. The possible mechanisms are postulated to be the oxidative pathways and microvascular changes (Fig. 2) [20].

Fig. 2.

Pathophysiology of Diabetic Neuropathy. The exact pathophysiology is not completely understood. The oxidative stress induced by constant hyperglycemic conditions pave way for inflammation which together causes nerve damage

Disruption of the blood-nerve-barrier

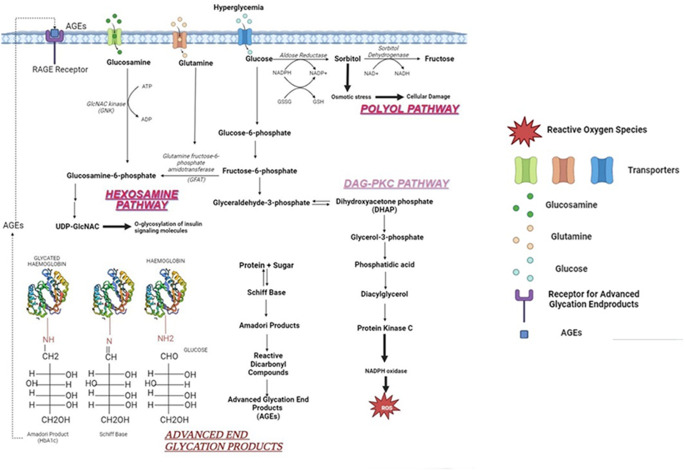

The blood vessels supplying the essential nutrients to the nerve tissue are made up of endothelial cells. The damage to these cells is expected to be caused due to oxidative stress by various metabolic pathways (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Oxidative pathways. The four major pathways influencing the nerve damage are briefly explained in the above figure. All these pathways initiate because of an imbalance caused by abnormally high levels of glucose and result in the activation of various inflammatory and pro-inflammatory mediators

Under hyperglycemic conditions, there is an imbalance between glycogenolysis and glycolysis, thus resulting in an accumulated sorbitol within the cells. It enhances the production of Aldose Reductase (AR) which is involved in the synthesis of sorbitol. AR enzyme functions in the presence of co-factor NADPH (Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide Phosphate Hydrogen) which converts toxic aldehydes to alcohols under normoglycemic conditions. However, under a hyperglycemic state they reduce glucose to sorbitol. Upregulation of aldose reductase also causes depletion of NADPH which is important in oxidation of glutathione (GSH), an anti-oxidant enzyme.

Sorbitol has two major consequences:

-

i.

Activation of Protein Kinase C (PKC) pathway.

-

ii.

Increases AGEs by ROS production.

Monosaccharides or reducing sugar are added to the protein or lipid molecules via a process called glycation. This process results in the formation of AGEs. Initially, the carbon group of sugars and the nitrogen group of amino acids form a double bond and results in a Schiff base. This Schiff base undergoes molecular rearrangement to form an Amadori product. The consistent accumulation of Amadori products results in the formation of AGEs.

E.g., HbA1c is an important biomarker of diabetes mellitus. Prolonged high levels of HbA1c indicate poor glycemic control which can increase the susceptibility of neuropathy.

-

c.

AGE-RAGE axis.

RAGE (Receptor for Advanced Glycation Endproducts) is present on the surface of the peri and endoneuria blood vessels. The AGE on interaction with RAGE activates NADPH oxidase which ultimately enhances the release of ROS, further exacerbating the oxidative stress.

The hexosamine pathway is a subsection of the glycolytic pathway. In this process, fructose 6 phosphate is converted to N-acetyl glucosamine-6-phosphate in the presence of an enzyme glutamine-fructose-6-phosphate aminotransferase (GFAT). Under normal conditions, the amount of fructose-6-phosphate involved in the hexosamine pathway is very minimal but in hyperglycaemic conditions, they are increased and hence the hyperglycaemia-induced hexosamine pathway is also increased, ultimately leading to H2O2 production.

Diacyl glycerol is a secondary messenger that is involved in the activation of various forms of protein kinases. Protein kinase C is a part of serine-threonine kinases involved in various functions. Hyperglycaemia increases the metabolites involved in the process of glycolysis and one such is dihydroxyacetone phosphate (DHAP) which is reduced into glycerol-3-phosphate. This compound is responsible for the de novo synthesis of DAG, which ultimately rises the PKC levels.

An increase in PKC levels has the following consequences:

-

i.

Activation of polyol pathway and AGEs synthesis.

-

ii.

Causes endothelial dysfunction resulting in increased vascular permeability.

ROS destroys the normal barrier by increasing the permeability thus disrupting the normal regulation of biomolecules. This causes edema and subsequently results in ischemic nerve damage [29].

Inflammation

Oxidative stress causes increased formation of AGEs which stimulate the generation of multiple inflammatory and pro-inflammatory mediators such as tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα), IL-1β, IL-6 and vascular adhesion molecule (VCAM)-1 and activation of NF-κβ, which is a powerful inducer of inflammatory cascades. In-vitro studies proved that incubation of AGEs with neuronal cells and Schwann cells caused cell death. Accumulation of AGEs interferes in the physiological axonal transport and subsequently results in nerve tissue atrophy and degeneration.

The AGEs cause release of different kinds of cytokines by acting on the microglial cells. A few are IL-1, IL-6, IL-17, TNF-α, chemo attractant protein-1, C-reactive protein and chemokines like CCL-2, CXC. Certain interleukins sensitize the peripheral nerves thereby increasing the perception of neuropathic pain. The chemokines activate the chemokine receptors to cause a hyperalgesic condition.

NF-κB (nuclear factor-kappa B) is a ubiquitous transcriptional factor that influences the release of cytokines, chemokines and cell adhesion molecules (CAMs). Since it is an important regulator of inflammation, preclinical studies suggest inhibition of this pathway leads to decreased inflammatory response [30, 31]. NF-κB induces neuronal apoptosis and further downregulates the Nrf2 pathway which is responsible for the anti-oxidant defence system. Nrf2 is usually dormant in normal conditions but when the cell is under stress it is activated to maintain homeostasis. The Nrf2 moves within the cell to the nucleus and binds to the DNA to activate the anti-oxidant system, thereby decreasing the oxidative stress inflicted on the cell [32].

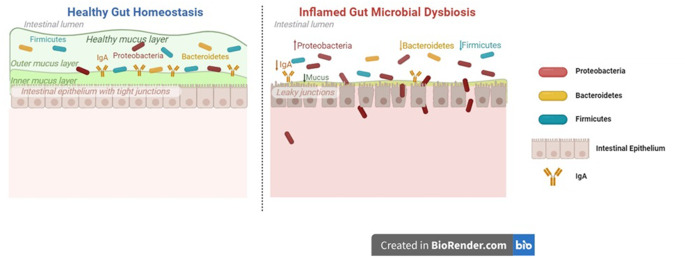

Gut dysbiosis and diabetes mellitus

The cluster of bacteria, fungi, virus, eukaryote and archaea present in the gut of the human body is known as gut microbiome. Gut microbiome is an essential protective barrier that maintains the integrity and structure of the gut layer, fights against harmful pathogens and modulation of host immunity [33]. Numerous factors have the potential to damage this gut microbiome and create a dysfunctional layer that fails to perform normal physiological functions. This might increase the pathogenic bacterial population leading to discrete disorders (Fig. 4) [34].

Fig. 4.

Healthy and damaged gut dysbiosis. The key difference between the two is the ability of the healthy gut to maintain integrity of the intestinal barrier. This integrity protects the system from getting affected by pathogenic substances and secondary metabolites produced by them

Dysbiosis of gut in diabetes is well-understood and it is closely related with certain metabolic disorders such as hyperlipidaemia/dyslipidaemia, obesity, insulin resistance and inflammation (Fig. 5). A study conducted in a Chinese population showed a significant difference in 43 bacterial taxa in case of T2DM [35]. T2DM showed increase in the myriad of pathogenic bacteria like Clostridium hathewayi, Clostridium symbiosum and Escherichia coli. The levels of Clostridium coccoides and Clostridium leptum were predominantly decreased in patients who were newly diagnosed with T2DM i.e., < 6 months of diagnosis [36].

Fig. 5.

A brief overview on the interrelated conditions in diabetic patients. The exact mechanism is still being studied but various hypotheses suggest that these conditions might co-exist in patients

In a preclinical study conducted by Yang and Jia et al., genistein, an isoflavone was found to decrease the insulin resistance and inflammation by modulating the abundance of certain genera of bacteria i.e., Bacteroides, Prevotella, Helicobacter and Ruminococcus. This could possibly indicate that gut microbiome plays an important role in the disorder and may act as a potential target [37].

The population of butyrate-producing bacteria of the genera Dialister, Anaerotruncus, and Ruminococcaceae was notably reduced in diabetic cats compared to the normal cats. Butyrates are produced in the intestines for the supply of energy to the epithelial cells present in the colon. It might also play a role increasing the sensitivity of the insulin [38].

It is speculated that gut microbiome is interrelated with the inflammatory response produced in the diabetic patients. The damage of intestinal barrier due to gut dysbiosis causes inflammation because of the leakage of the contents of intestine into the systemic circulation. These contents include the metabolites produced by the pathogenic bacteria [39, 40].

Multiple research suggests that A. muciniphila was significantly reduced in the T2DM animal models. The abundance of the bacterium when increased by A. muciniphila treatment and A. muciniphila derived extracellular vesicles reduced the intestinal permeability and helped to prevent further damage of integrity of the intestine, thereby providing substantial evidence that this bacterial species plays an important part in maintaining the intestinal structure [41, 42].

The link between the gut dysbiosis and T1DM is well proven. Interaction between the immunity of the host and bacteria is expected to significantly impact the progression of T1DM. Toll-like receptors (TLR) are key players in the maintenance of innate immunity and the homeostasis of the intestines. Gut dysbiosis affect the host innate immunity by interfering in the TLR signalling [43].

The activation of TLR can trigger an inflammatory cascade that acts as a defence system against the pathogenic molecules. The metabolites of the bacteria are known to bring about this response. The TLR signalling worsens the inflammation by releasing cytokines and other mediators of inflammation [44].

Gut dysbiosis and diabetic neuropathy

Diabetic neuropathy has been pertinent to the alteration of gut dysbiosis and the leaky gut associated with it. The leaky gut further paves way for pathogens to enter the systemic circulation (Fig. 5) [40].

The nervous system recognises the changes in the microbiota composition via the enteric nervous system (ENS) present in the gastrointestinal tract (GIT). The ENS is made up of nerve tissues present in the myenteric plexus of the GIT. The afferent and the efferent neurons emerging from these are linked with the central nervous system. In addition, the entero-endocrine cells which produce major secretory hormones is also suspected to have a role in the influence of gut microbiota on the functions of neuronal cells [45, 46].

There are varied evidences linking change in the microbiome composition and the development of diabetes and its complications. But one consistent evidence is the depletion of a group of micro-organisms producing butyrate. Firmicutes species breaks down the substrates, majorly the non-digestible polysaccharides and resistant starch to short chain fatty acids (SCFA) via the hydrolysis reaction. The three important SCFAs are butyrate, acetate and propionate [47].

The function of SCFAs is assumed to be navigating towards hypoglycaemic and anti-obesity effects but certain studies have also demonstrated that excessive production of these could result in obesity, primarily due to energy accumulation. There is an important need to understand the triangle of SCFA production, gut microbiota and its relationship with metabolic disorders [48].

It is understood that dysbiosis of the gut produces metabolic endotoxemia that is responsible for low-grade inflammation effect through the release of bacterial metabolites such as the lipopolysaccharides (LPS). LPS gets cumulated in the systemic circulation via the leaky gut and acts on CD14/TLR4 pathway. This pathway is an important pathogen sensing pathways and is responsible for the inflammation [49].

Toll-like receptors (TLR) are a part of pattern recognition receptor family specifically aimed at recognising the patterns of microbes. They detect the antigens of bacteria, like LPS or peptidoglycans. TLRs are important mediators that balance the homeostatic conditions in the intestine, via the interaction between the microbiome and the mucosa. The hyperactivation of TLR signalling can result in a chronic inflammatory response [50]. The intestinal barrier integrity depends upon two factors. TLR4 and NF-κβ activation through LPS and other components of microbes. This activation plays a role in the regulation of the neuromuscular function and development in the intestines. TLR9 is considered a key element of the neuronal activity that occurs in the ENS [51, 52].

GLP-1 (Glucagon-like peptide-1) which is used as a target in treating T2DM is related to the gastric emptying and secretion of insulin in the body. The normal functioning of GLP-1 occurs only in case of normal microbiotic conditions, which is disturbed in neuropathy and hence the impaired insulin secretion and synthesis of nitric oxide (NO) in the ENS is interconnected with the insulin secretion [53].

Wang et al., provides evidence that on comparison with diabetic patients with and without neuropathy, there is a significant difference in the abundance of certain bacterial taxa. Patients with diabetic neuropathy showed increase in the population of phylum Firmicutes and Actinobacteria and it showed decrease in the population of Bacteroidetes on comparison with patients without diabetic neuropathy and healthy individuals. Genus Bacteroides and Faecalibacterium and Escherichia-Shigella, Lachnoclostridium, Blautia, Megasphaera, and Rumincoccus were shown to be more widespread. It is hypothesised that this change in microbiome is related with diabetic neuropathy. Homeostatic Model Assessment for Insulin Resistance (HOMA-IR) score determines the insulin resistance of an individual, and it was observed to be correlated positively with the abundance of Megasphaera. This implies that the dysbiosis probably has a role to play in the insulin resistance [54].

Yuhui et al., demonstrated that diabetic mellitus is exacerbated by the development of autonomic neuropathy in gastrointestinal tract. It is well-elucidated that T2DM has altered population of microbiome. Certain species such as the Gammaproteobacterial, Enterobacteriales, Enterobacteriaceae, Escherichia-Shigella, Megasphaera, Escherichia coli and Megasphaera elsdenii were characteristic of neuropathy [55].

Emerging techniques to tackle gut dysbiosis include faecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) that could possibly reverse the dysfunctional intestinal barrier. Futhermore, administration of Bifidobacteria and Lactobacillus has the potential to increase the sensitivity of insulin [56].

Gut dysbiosis and cognitive impairment linked with diabetes mellitus

Cognition is the body’s normal physiological function that involves taking in and understanding the sensory inputs received from the environment and comprehending it accordingly. Impairments in the cognitive functioning can reduce the quality of life (QoL) of an individual. Diabetes mellitus pose itself as one of the risk factors for developing mild cognitive impairment (MCI) which can ultimately lead to dementia and AD [57, 58].

Multiple pre-clinical and clinical studies prove alteration in the gut and development of cognitive decline is associated. Bacteria of the five major phyla i.e., Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, Proteobacteria, Actinobacteria and Verrucomicrobia is observed in patients diagnosed with cognitive impairment. In addition, it is correlated with Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio which is increased in cognitive impaired patients. Persistent higher levels of Firmicutes are observed in patients with MCI (Fig. 5) [59, 60].

Increasing evidence suggest that the gut microbiome and central nervous system interact via various pathways with the release of certain neurotransmitters and neurotoxins from the gut microbiota [61, 62]. These released molecules regulate the neuronal activities by crossing the BBB. Central nervous system and the enteric nervous system is connected through the vagus nerve and autonomic nervous system. When the ENS is activated by the signals received from gut, it affects the gut cells and modulates inflammatory pathways of the peripheral nervous system [63, 64].

Zhang et al., conducted a study on diabetic patients with and without cognitive impairment to determine the microbial diversity in these two types of patients. Patients who were identified with cognitive dysfunction had a lowered abundance of Tenericutes, Actinobacteria and Mollicutes. At the genus level, decreased Bifidobacterium, Veillonella, Pediococcus and increased abundance of Peptococcus and Leuconostocaceae were reported [65].

The alterations in the gut microbiome were also demonstrated in the preclinical studies. Gao et al., conducted a study on advanced stage type 1 diabetes (AST1D) rats with cognitive impairment and age-matched controls (AMC) to study the diversity of the microbial population. He reported that the microbiome alterations were significant in ASTID rats. Relatively higher abundance of Bacteroidetes and lower Proteobacteria was observed in AST1D rats. Energy metabolism which is vital for every organism is notably reduced in AST1D rats, especially in the serum and hippocampus [66]. This is identified by the decreased intermediates of TCA cycle (Krebs cycle) such as the citrates, fumarates, succinates etc. Apart from the TCA cycle, creatinine or creatinine phosphate is also an indicator of energy metabolism, specifically from organs with higher demands. This energy metabolism is a key factor in the cognitive function. In the study by Gao et al., it is reported that the levels of creatinine, fumarate and citrates is positively correlated with alterations in Clostridium, Romboutsia and Turicibacter, which suggest that there might be a link between microbiota and regulation of energy metabolism [66, 67].

Choline is an essential compound in the acetylcholine synthesis and cholinergic transmission, hence known to be associated with cognitive dysfunction. Tabassum et al., demonstrated that administration of choline improved cognitive dysfunction in adults by decreasing the ROS production and improvement of cholinergic transmission [68]. Gao et al., reported that the levels of choline in the serum and hippocampus was significantly lower in AST1D rats in comparison with AMC rats. This deficiency is associated with decreased population of Clostridium, Romboutsia and Turicibacter which might indicate connection between microbiota and reduced hippocampal choline levels. Therefore, a deficiency in the choline can trigger cognitive dysfunction which is further aggravated by diabetes [66]. Swann et al., also reported reduced choline in the hippocampus in the germ-free rats compared to the normal rats [69]. These indicate that there might be a causal relationship with choline deficiency and cognitive dysfunction linked with diabetes.

Analysis of patients’ brain with AD reported overlapping of lipopolysaccharides and E. coli with the amyloid plaques. The mechanism is suspected to be the ability of the pathogens to produce certain functional amyloid plaques which might have a role in the MCI [70]. The accumulation of amyloid triggers a neuronal inflammation. As mentioned earlier, the gut dysbiosis causes systemic inflammation, which further worsens the condition. The increase in the permeability is linked with increased concentrations of LPS and certain inflammatory mediators such as the IL-1, TNF-α.

Diabetic neuropathy and diabetic cognitive impairment

Chronic persistent pain especially in the elderly is associated with dementia. Several studies reported that pain and certain geriatric syndromes like falling, functional inability and poor cognition are related [71]. The exact mechanism behind the correlation is yet to be elucidated. One of the hypotheses suggests cognitive impairment is present during conditions of pain because chronic pain competes for the limited attentional resources. Therefore, it is expected that the presence of pain may exacerbate cognitive decline [72]. Hence it is reasonable to comprehend that pain and diabetes are likely to be associated with the mild cognitive impairment. However, the relationship between neuropathy and cognitive impairment has received less attention [73].

Yasemin et al., studied the correlation between diabetic neuropathy and sarcopenia. Sarcopenia is a clinical condition that causes loss in the muscle mass due to ageing or any chronic diseases. He reported that the prevalence of sarcopenia in obese diabetic neuropathy patients is higher compared to the non-obese diabetic neuropathy patients [74]. A systematic review and meta– analysis report conducted on the relationship between sarcopenia and cognitive impairment in the elderly showed that both these factors are associated and early detection can help improve the cognitive dysfunction in patients [75, 76].

Jenifer et al., reported that cognitive impairment is higher in the case of patients with diabetic peripheral neuropathy than without it. The dysfunction in T1DM patients presented itself as reduced concentration, impaired flexibility in the mental state (i.e., switching between tasks when the situation demands it) and reduced psychomotor ability (relationship between the cognition and the physical response to it) [77]. The dysfunction in T2DM manifested itself as a loss in the flexibility of executive functioning/ mental state and an increased time gap between memory and response time [78].

An alternate theory was also demonstrated where patients with painless diabetic neuropathy showed increased cognitive decline. Another study showed an increased latency in cognitive test in patients with painless diabetic neuropathy in comparison with painful diabetic neuropathy [79]. Mc Crimmon and Ryan et al., reported a significant decrease in the thalamic volume in painless diabetic neuropathy compared to painful diabetic neuropathy. Magnetic resonance spectroscopy confirmed this, as it reported higher thalamic neuronal dysfunction in subjects with painless neuropathy. This might be because thalamus has a role to lay in the normal physiological memory functioning which is disturbed in neuropathic conditions, and hence the cognitive decline [79]. The latency period was also correlated with the neuron-specific enolase (NSE) levels in the diabetic patient. NSE is an important biomarker in diabetic neuropathic patients where higher levels imply significant neuronal damage. The serum NSE was significantly correlated with poor cognitive functioning [79, 80].

Conclusion

This review focuses on the less explored relationship between diabetic neuropathy and cognitive function. Gut dysbiosis which is commonly associated with gastrointestinal disorders, are now reported to have link with neurological disorders as well. This review seeks to find an interrelationship between diabetic neuropathy, cognitive impairment and gut dysbiosis. A few systematic reviews, meta-analysis data and randomized controlled trials have certainly suggested an implication that these three factors might play a key role in worsening the condition of the patient.

The interplay between diabetic neuropathy, gut dysbiosis and cognitive impairment is an emerging area of research with potential impact on the treatment strategies for diabetic patients. Investigating the precise mechanism is necessary to understand their impact on each other. Manipulating the gut microbiome through probiotics, prebiotics and FMT can potentially reverse the neuropathy and cognitive dysfunction. Identification of biomarkers in blood, stool and urine, physical examinations, imaging techniques can predict and diagnose diabetic neuropathy at an early stage allowing timely interventions. Personalized treatment strategies targeting an individual’s gut microbiome profile and thereby treating the associated neuropathy and cognitive impairment is necessary. Conducting well-designed, large scale clinical studies is vital to validate the efficacy and safety of microbiome-based therapeutic interventions in managing diabetic neuropathy and cognitive dysfunction.

The major challenge in this study would be establishing the causality. This study shows correlation between the three factors but it is difficult to determine if gut dysbiosis causes neuropathy and cognitive decline or if it is a result of these conditions. Diabetes in itself has an impact on gut microbiota and cognitive dysfunction. Hence, studies are needed to isolate the specific effects of gut dysbiosis. Assessment and quantification of these disorders are constantly evolving. Choosing the right method and interpretation of the results are complex and challenging. The current research is directed towards observational studies and hence there is lack of substantial evidence confirming the interplay. These impairments can manifest in different individuals, hence, limited sample size and lack of long-term data makes the study a tedious one. Acknowledging these limitations is essential to design a more robust study to understand this complex interplay.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Department of Pharmacology and The Principal, JSS College of Pharmacy, JSS Academy of Higher Education & Research, Mysuru for his support in drafting this review.

Author contributions

Divya Durai Babu: Conceptualization; Visualization; Writing- original draft; Seema Mehdi: Review and formatting; Kamsagara Linganna Krishna: Conceptualization; Visualization; Review the original draft and supervision; Mankala Sree Lalitha: Conceptualization; Visualization; Chethan Konasuru Someshwara: Review and formatting; Suman Pathak: Review and formatting; Ujwal Reddy Pesaladinne: Writing the draft, review & editing; Rahul Kinnarahalli Rajashekarappa: Writing the draft, review & editing; Prakruthi Shivakumari Mylaralinga: Writing the draft, review & editing.

Funding

No funding was received to assist with the preparation of this manuscript.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Yaribeygi H, Sathyapalan T, Atkin SL, Sahebkar A. Molecular Mechanisms Linking Oxidative Stress and Diabetes Mellitus. Tocchetti CG, editor. Oxid Med Cell Longev [Internet]. 2020;2020:8609213. 10.1155/2020/8609213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.IDF DIABETES, ATLAS. 2021.

- 3.Feldman EL, Callaghan BC, Pop-Busui R, Zochodne DW, Wright DE, Bennett DL, et al. Diabetic neuropathy. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2019;5:42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grover M, Makkar R, Sehgal A, Seth SK, Gupta J, Behl T. Etiological aspects for the occurrence of Diabetic Neuropathy and the suggested measures. Neurophysiology. 2020;52:159–68. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shillo P, Sloan G, Greig M, Hunt L, Selvarajah D, Elliott J et al. Painful and Painless Diabetic Neuropathies: What Is the Difference? Curr Diab Rep [Internet]. 2019;19:32. 10.1007/s11892-019-1150-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Tanenberg RJ, Donofrio PD. Neuropathic problems of the Lower limbs in Diabetic patients. Levin and O’Neal’s the Diabetic Foot with CD-ROM. Elsevier; 2007. pp. 33–74.

- 7.Ponomareva MN, Sakharova SV, Turlybekova DA, Protopopov LA, Pimenov AA, Timofeeva EE, THE INFORMATIVE VALUE OF PERIPHERAL BLOOD INDICES IN THE DIAGNOSIS OF THE ETIOLOGY OF OPTIC NERVE DAMAGE. Современные проблемы науки и образования (Mod Probl Sci Education). 2022;7–7.

- 8.Rumora AE, Guo K, Hinder LM, O’Brien PD, Hayes JM, Hur J et al. A high-Fat Diet disrupts nerve lipids and mitochondrial function in Murine models of Neuropathy. Front Physiol. 2022;13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Ding P-F, Zhang H-S, Wang J, Gao Y-Y, Mao J-N, Hang C-H, et al. Insulin resistance in ischemic stroke: mechanisms and therapeutic approaches. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2022;13:1092431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sánchez-Alegría K, Arias C. Functional consequences of brain exposure to saturated fatty acids: from energy metabolism and insulin resistance to neuronal damage. Endocrinol Diabetes Metab. 2023;6:e386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stentz B. Hyperglycemia- and Hyperlipidemia-Induced inflammation and oxidative stress through human T lymphocytes and human aortic endothelial cells (HAEC). Sugar Intake - Risks and benefits and the global diabetes epidemic. IntechOpen; 2021.

- 12.Hyperglycemia and Hyperlipidemia Induced Inflammation. and Oxidative Stress in Human T Lymphocytes and Salutary effects of ω- 3 fatty acid. SunKrist J Diabetol Clin Care. 2020;1–9.

- 13.Zhao Y, Zhu R, Wang D, Liu X. Genetics of diabetic neuropathy: systematic review, meta-analysis and trial sequential analysis. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2019;6:1996–2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhou X, Zhu Y, Gao L, Li Y, Li H, Huang C et al. Binding of RAGE and RIPK1 induces cognitive deficits in chronic hyperglycemia-derived neuroinflammation. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Rom S, Zuluaga-Ramirez V, Gajghate S, Seliga A, Winfield M, Heldt NA, et al. Hyperglycemia-driven neuroinflammation compromises BBB leading to memory loss in both diabetes Mellitus (DM) type 1 and type 2 mouse models. Mol Neurobiol. 2019;56:1883–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alshammari NA, Alodhayani AA, Joy SS, Isnani A, Mujammami M, Alfadda AA, et al. Evaluation of risk factors for Diabetic Peripheral Neuropathy among Saudi Type 2 Diabetic patients with longer duration of diabetes. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2022;15:3007–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Braffett BH, Gubitosi-Klug RA, Albers JW, Feldman EL, Martin CL, White NH, et al. Risk factors for Diabetic Peripheral Neuropathy and Cardiovascular Autonomic Neuropathy in the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial/Epidemiology of Diabetes Interventions and complications (DCCT/EDIC) study. Diabetes. 2020;69:1000–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sidawi B, Al-Hariri MTA. The impact of built environment on diabetic patients: the case of Eastern Province, KIngdom of Saudi Arabia. Glob J Health Sci. 2012;4:126–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaur K. Current strategies used for better management of Type-2 diabetes mellitus. 2020. https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:219602164.

- 20.Galiero R, Caturano A, Vetrano E, Beccia D, Brin C, Alfano M et al. Peripheral neuropathy in diabetes Mellitus: pathogenetic mechanisms and Diagnostic options. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Jun L, Jang SD, Hee N, Mi Y et al. The formation of advanced glycation end-products (AGEs), increased polyol pathway flux, activation of protein kinase C isoforms, and increased hexosamine pathway flux. 2011. https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:210139933.

- 22.Imran A, Shehzad MT, Shah SJA, Laws M, Al-Adhami T, Rahman KM, et al. Development, Molecular Docking, and in Silico ADME evaluation of selective ALR2 inhibitors for the Treatment of Diabetic Complications via suppression of the Polyol Pathway. ACS Omega. 2022;7:26425–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Egaña-Gorroño L, López-Díez R, Yepuri G, Ramirez LS, Reverdatto S, Gugger PF et al. Receptor for Advanced Glycation End products (RAGE) and mechanisms and Therapeutic opportunities in Diabetes and Cardiovascular Disease: insights from human subjects and animal models. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2020;7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Sellegounder D, Zafari P, Rajabinejad M, Taghadosi M, Kapahi P. Advanced glycation end products (AGEs) and its receptor, RAGE, modulate age-dependent COVID-19 morbidity and mortality. A review and hypothesis. Int Immunopharmacol. 2021;98:107806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chaveroux C, Sarcinelli C, Barbet V, Belfeki S, Barthelaix A, Ferraro-Peyret C, et al. Nutrient shortage triggers the hexosamine biosynthetic pathway via the GCN2-ATF4 signalling pathway. Sci Rep. 2016;6:27278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Paneque A, Fortus H, Zheng J, Werlen G, Jacinto E. The Hexosamine Biosynthesis Pathway: regulation and function. Genes (Basel). 2023;14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Ighodaro OM. Molecular pathways associated with oxidative stress in diabetes mellitus. Biomed Pharmacother. 2018;108:656–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Giri B, Dey S, Das T, Sarkar M, Banerjee J, Dash SK. Chronic hyperglycemia mediated physiological alteration and metabolic distortion leads to organ dysfunction, infection, cancer progression and other pathophysiological consequences: an update on glucose toxicity. Biomed Pharmacother. 2018;107:306–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Carrasco C, Naziroǧlu M, Rodríguez AB, Pariente JA. Neuropathic Pain: delving into the oxidative origin and the possible implication of transient receptor potential channels. Front Physiol. 2018;9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Song N, Thaiss F, Guo L. NFκB and kidney Injury. Front Immunol. 2019;10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Rayego-Mateos S, Morgado-Pascual JL, Opazo-Ríos L, Guerrero-Hue M, García-Caballero C, Vázquez-Carballo C, et al. Pathogenic pathways and therapeutic approaches targeting inflammation in Diabetic Nephropathy. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21:3798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kumar A, Mittal R. Nrf2: a potential therapeutic target for diabetic neuropathy. Inflammopharmacology. 2017;25:393–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thursby E, Juge N. Introduction to the human gut microbiota. Biochem J. 2017;474:1823–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Weiss GA, Hennet T. Mechanisms and consequences of intestinal dysbiosis. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2017;74:2959–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang T-Y, Zhang X-Q, Chen A-L, Zhang J, Lv B-H, Ma M-H, et al. A comparative study of microbial community and functions of type 2 diabetes mellitus patients with obesity and healthy people. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2020;104:7143–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen P-C, Chien Y-W, Yang S-C. The alteration of gut microbiota in newly diagnosed type 2 diabetic patients. Nutrition. 2019;63–64:51–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yang R, Jia Q, Mehmood S, Ma S, Liu X. Genistein ameliorates inflammation and insulin resistance through mediation of gut microbiota composition in type 2 diabetic mice. Eur J Nutr. 2021;60:2155–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kieler IN, Osto M, Hugentobler L, Puetz L, Gilbert MTP, Hansen T, et al. Diabetic cats have decreased gut microbial diversity and a lack of butyrate producing bacteria. Sci Rep. 2019;9:4822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Scheithauer TPM, Rampanelli E, Nieuwdorp M, Vallance BA, Verchere CB, van Raalte DH et al. Gut microbiota as a trigger for metabolic inflammation in obesity and type 2 diabetes. Front Immunol. 2020;11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40.Iatcu CO, Steen A, Covasa M. Gut microbiota and complications of Type-2 diabetes. Nutrients. 2021;14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 41.Plovier H, Everard A, Druart C, Depommier C, Van Hul M, Geurts L, et al. A purified membrane protein from Akkermansia muciniphila or the pasteurized bacterium improves metabolism in obese and diabetic mice. Nat Med. 2017;23:107–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chelakkot C, Choi Y, Kim D-K, Park HT, Ghim J, Kwon Y, et al. Akkermansia muciniphila-derived extracellular vesicles influence gut permeability through the regulation of tight junctions. Exp Mol Med. 2018;50:e450–450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gradisteanu Pircalabioru G, Corcionivoschi N, Gundogdu O, Chifiriuc M-C, Marutescu LG, Ispas B, et al. Dysbiosis in the development of type I diabetes and Associated complications: from mechanisms to targeted gut microbes Manipulation therapies. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:2763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yehualashet AS. Toll-like receptors as a potential drug target for diabetes Mellitus and Diabetes-associated complications. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2020;13:4763–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yu Y, Yang W, Li Y, Cong Y. Enteroendocrine cells: sensing gut microbiota and regulating inflammatory Bowel diseases. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2020;26:11–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mázala-de-Oliveira T, Jannini de Sá YAP, de Carvalho V. F. Impact of gut-peripheral nervous system axis on the development of diabetic neuropathy. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2023;118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 47.Fusco W, Lorenzo MB, Cintoni M, Porcari S, Rinninella E, Kaitsas F, et al. Short-chain fatty-acid-producing Bacteria: Key Components of the human gut microbiota. Nutrients. 2023;15:2211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sanna S, van Zuydam NR, Mahajan A, Kurilshikov A, Vich Vila A, Võsa U, et al. Causal relationships among the gut microbiome, short-chain fatty acids and metabolic diseases. Nat Genet. 2019;51:600–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Denou E, Lolmède K, Garidou L, Pomie C, Chabo C, Lau TC, et al. Defective NOD2 peptidoglycan sensing promotes diet-induced inflammation, dysbiosis, and insulin resistance. EMBO Mol Med. 2015;7:259–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fang Y, Yan C, Zhao Q, Zhao B, Liao Y, Chen Y, et al. The Association between Gut Microbiota, Toll-Like receptors, and Colorectal Cancer. Clin Med Insights Oncol. 2022;16:117955492211305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Patel V, Patel AM, McArdle JJ. Synaptic abnormalities of mice lacking toll-like receptor (TLR)-9. Neuroscience. 2016;324:1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chen P, Wang C, Ren Y, Ye Z, Jiang C, Wu Z. Alterations in the gut microbiota and metabolite profiles in the context of neuropathic pain. Mol Brain. 2021;14:50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Grasset E, Puel A, Charpentier J, Collet X, Christensen JE, Tercé F, et al. A specific gut microbiota dysbiosis of type 2 Diabetic mice induces GLP-1 resistance through an enteric NO-Dependent and gut-brain Axis mechanism. Cell Metab. 2017;25:1075–e10905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang Y, Ye X, Ding D, Lu Y. Characteristics of the intestinal flora in patients with peripheral neuropathy associated with type 2 diabetes. J Int Med Res. 2020;48:030006052093680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Du Y, Neng Q, Li Y, Kang Y, Guo L, Huang X et al. Gastrointestinal autonomic neuropathy exacerbates gut microbiota dysbiosis in adult patients with type 2 diabetes Mellitus. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2022;11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 56.Sabico S, Al-Mashharawi A, Al-Daghri NM, Wani K, Amer OE, Hussain DS, et al. Effects of a 6-month multi-strain probiotics supplementation in endotoxemic, inflammatory and cardiometabolic status of T2DM patients: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Clin Nutr. 2019;38:1561–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sharma G, Parihar A, Talaiya T, Dubey K, Porwal B, Parihar MS. Cognitive impairments in type 2 diabetes, risk factors and preventive strategies. J Basic Clin Physiol Pharmacol. 2020;31. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 58.Pei Y, Lu Y, Li H, Jiang C, Wang L. Gut microbiota and intestinal barrier function in subjects with cognitive impairments: a cross-sectional study. Front Aging Neurosci. 2023;15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 59.Zhuang Z-Q, Shen L-L, Li W-W, Fu X, Zeng F, Gui L, et al. Gut microbiota is altered in patients with Alzheimer’s Disease. J Alzheimer’s Disease. 2018;63:1337–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Saji N, Niida S, Murotani K, Hisada T, Tsuduki T, Sugimoto T, et al. Analysis of the relationship between the gut microbiome and dementia: a cross-sectional study conducted in Japan. Sci Rep. 2019;9:1008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dinan TG, Cryan JF. The Microbiome-Gut-Brain Axis in Health and Disease. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2017;46:77–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cani PD, Knauf C. How gut microbes talk to organs: the role of endocrine and nervous routes. Mol Metab. 2016;5:743–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Leclercq S, Mian FM, Stanisz AM, Bindels LB, Cambier E, Ben-Amram H, et al. Low-dose penicillin in early life induces long-term changes in murine gut microbiota, brain cytokines and behavior. Nat Commun. 2017;8:15062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Fröhlich EE, Farzi A, Mayerhofer R, Reichmann F, Jačan A, Wagner B, et al. Cognitive impairment by antibiotic-induced gut dysbiosis: analysis of gut microbiota-brain communication. Brain Behav Immun. 2016;56:140–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhang Y, Lu S, Yang Y, Wang Z, Wang B, Zhang B, et al. The diversity of gut microbiota in type 2 diabetes with or without cognitive impairment. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2021;33:589–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gao H, Jiang Q, Ji H, Ning J, Li C, Zheng H. Type 1 diabetes induces cognitive dysfunction in rats associated with alterations of the gut microbiome and metabolomes in serum and hippocampus. Biochim et Biophys Acta (BBA) - Mol Basis Disease. 2019;1865:165541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cani PD, Van Hul M, Lefort C, Depommier C, Rastelli M, Everard A. Microbial regulation of organismal energy homeostasis. Nat Metab. 2019;1:34–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tabassum S, Haider S, Ahmad S, Madiha S, Parveen T. Chronic choline supplementation improves cognitive and motor performance via modulating oxidative and neurochemical status in rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2017;159:90–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Swann JR, Garcia-Perez I, Braniste V, Wilson ID, Sidaway JE, Nicholson JK, et al. Application of 1 H NMR spectroscopy to the metabolic phenotyping of rodent brain extracts: a metabonomic study of gut microbial influence on host brain metabolism. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2017;143:141–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zhan X, Stamova B, Jin L-W, DeCarli C, Phinney B, Sharp FR. Gram-negative bacterial molecules associate with Alzheimer disease pathology. Neurology. 2016;87:2324–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Whitlock EL, Diaz-Ramirez LG, Glymour MM, Boscardin WJ, Covinsky KE, Smith AK. Association between Persistent Pain and Memory decline and Dementia in a Longitudinal Cohort of elders. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177:1146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.van der Leeuw G, Eggermont LHP, Shi L, Milberg WP, Gross AL, Hausdorff JM, et al. Pain and cognitive function among older adults living in the community. J Gerontol Biol Sci Med Sci. 2016;71:398–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ming A, Lorek E, Wall J, Schubert T, Ebert N, Galatzky I et al. Unveiling peripheral neuropathy and cognitive dysfunction in diabetes: an observational and proof-of-concept study with video games and sensor-equipped insoles. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2024;15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 74.Yasemin Ö, Seydahmet A, Özcan K. Relationship between diabetic neuropathy and sarcopenia. Prim Care Diabetes. 2019;13:521–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Peng T-C, Chen W-L, Wu L-W, Chang Y-W, Kao T-W. Sarcopenia and cognitive impairment: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Nutr. 2020;39:2695–701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Szlejf C, Suemoto CK, Lotufo PA, Benseñor IM. Association of Sarcopenia with Performance on multiple cognitive domains: results from the ELSA-Brasil Study. Journals Gerontology: Ser A. 2019;74:1805–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Croosu SS, Gjela M, Røikjer J, Hansen TM, Mørch CD, Frøkjær JB et al. Cognitive function in individuals with and without painful and painless diabetic polyneuropathy—A cross-sectional study in type 1 diabetes. Endocrinol Diabetes Metab. 2023;6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 78.Palomo-Osuna J, De Sola H, Dueñas M, Moral-Munoz JA, Failde I. Cognitive function in diabetic persons with peripheral neuropathy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Expert Rev Neurother. 2022;22:269–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Elsharkawy RE, Abdel Azim GS, Osman MA, Maghraby HM, Mohamed RA, Abdelsalam EM, et al. Peripheral polyneuropathy and cognitive impairment in type II diabetes Mellitus. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2021;17:627–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Haque A, Polcyn R, Matzelle D, Banik NL. New insights into the role of neuron-specific enolase in Neuro-Inflammation, neurodegeneration, and Neuroprotection. Brain Sci. 2018;8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]