Abstract

Purpose

The aim of this study was to identify novel vaginal probiotics with the potential to prevent vulvovaginal candidiasis (VVC) and bacterial vaginosis (BV).

Materials and Methods

Eighteen strains of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum were isolated from healthy Korean women, and their antimicrobial effects against Candida albicans and Gardnerella vaginalis were assessed. Three strains (L. plantarum LM1203, LM1209, and LM1215) were selected for further investigation, focusing on their growth inhibition, biofilm regulation, and cellular mechanisms against these vaginal pathogens. Additionally, electron microscopy revealed damage to G. vaginalis induced by L. plantarum LM1215, and genomic analysis was conducted on this strain.

Results

L. plantarum LM1203, LM1209, and LM1215 showed approximately 1 and 2 Log CFU/mL growth reduction in C. albicans and G. vaginalis, respectively. These L. plantarum strains effectively inhibited biofilm formation and eliminated the mature biofilms formed by C. albicans. Furthermore, L. plantarum LM1215 decreased tricarboxylic acid cycle activity by 51.75 (p<0.001) and respiratory metabolic activity by 52.88% (p<0.001) in G. vaginalis. L. plantarum induced cellular membrane damage, inhibition of protein synthesis, and cell wall collapse in G. vaginalis. Genomic analysis confirmed L. plantarum LM1215 as a safe strain for vaginal probiotics.

Conclusion

The L. plantarum LM1215 is considered a safe probiotic agent suitable for the prevention of VVC and BV.

Keywords: Lactiplantibacillus plantarum, probiotics, microbial sensitivity test, vulvovaginal candidiasis, bacterial vaginosis

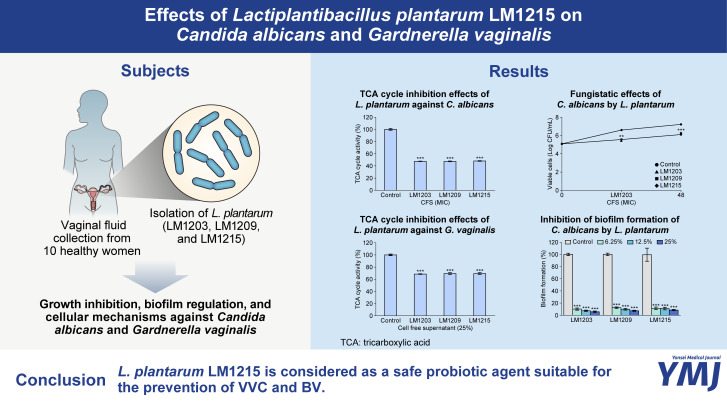

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

The vaginal tract harbors various microbiomes, constituting approximately 9% of the total human microbiota.1 In a healthy vaginal environment, the predominant lactic acid bacteria (LAB) play a pivotal role in maintaining the equilibrium of the vaginal microbiome niche.1,2 The microflora in a healthy vaginal tract mainly consists of Lactobacillus spp., such as Lactobacillus crispatus, Lactobacillus gasseri, and Lactobacillus jensenii.1,3 Conversely, vulvovaginal candidiasis (VVC) or bacterial vaginosis (BV) is associated with an abundance of Candida albicans,4 Gardnerella vaginalis, Prevotella bivia, and Fannyhessea vaginae.1,2

Antibiotics are the conventional treatment for VVC and BV.2,4,5 Typically, antibiotic treatments exhibit efficacy within a week;5 however, more than 50% of women treated with antibiotics experience recurrences within 12 months.5,6 Antibiotics, while effective against the causative agent, cannot directly restore the vaginal microflora, which contributes to the high recurrence rates. It has been reported that many women who have experienced BV are using probiotics as an alternative therapy to prevent the recurrence of vaginosis, although their safety and efficacy have not yet been proven.5

Lactiplantibacillus plantarum has more extensive genomic profile than other LAB species.7 Its large genome (approximately 3.3 Mbp) allows L. plantarum to inhabit various niches, including the gastrointestinal tract,7,8 vaginal mucosa,1,8 vegetables,7,8 fruits, meat, and dairy products.7 Genomic diversity also affects the antimicrobial activity of L. plantarum. Plantaricin, a member of the bacteriocin family, is the most common antimicrobial compound produced by L. plantarum. Additionally, L. plantarum secretes other compounds, such as organic acids, biosurfactants, and phenolic compounds. These antimicrobial agents can disrupt the cell membrane, induce leakage of intracellular molecules, and inhibit biofilm formation.8

In this study, we aimed to isolate novel probiotic strains from the vaginal tracts of healthy Korean women and investigate their antimicrobial efficacy against C. albicans and G. vaginalis. The isolated strains were evaluated for their ability to inhibit mature biofilm formation by C. albicans and the growth of G. vaginalis via cellular membrane damage. Furthermore, genome informatics was employed to predict potential antimicrobial agents. The results of this study may contribute to the prevention of vaginosis recurrence and regulation of vaginal microflora.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents and microorganisms

Crystal violet solution, iodonitrotetrazolium chloride (INT), and N-phenyl-1-naphthylamine (NPN) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Resazurin was purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA).

C. albicans ATCC 11006 and G. vaginalis ATCC 14018 were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). C. albicans ATCC 11006 was cultured in yeast mold (YM) broth (MBCell, Seoul, Korea) at 24℃ for 48 h. G. vaginalis ATCC 14018 was cultured in modified Brain Heart Infusion broth (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) containing 10% of horse serum (MBCell), 1% of yeast extract (BD Biosciences), 0.1% of maltose (Sigma-Aldrich), and 0.1% of glucose (Sigma-Aldrich) (BHYMG) at 37℃ for 24 h under anaerobic condition.2 Anaerobic conditions were maintained using a 20% CO2 gas pack within an anaerobic jar (Mitsubishi Gas Chemical Company, Tokyo, Japan). These strains were preserved in media containing 10% glycerol at -80℃ until use.

Collection of vaginal fluid

This study included healthy reproductive Korean women aged 18–35 years, who visited Kyung Hee University Hospital at Gangdong for general checkups between September 2022 and October 2022. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Kyung Hee University Hospital at Gangdong (IRB No. KHNMC 2022-06-044). Vaginal samples from all volunteers were tested for Nugent scoring, and only women with a score of <4 were interpreted as normal and included in this study. The exclusion criteria were current vaginitis or cervicitis, current use of oral contraceptives, antibiotic use within 14 days, probiotic use within 2 months, history of pelvic organ surgery, premenstrual syndrome, severe dysmenorrhea, history of alcohol or drug addiction, heavy smoking, and use of any medication for medical or psychological diseases. Ten healthy women were enrolled in this study, and vaginal fluid was collected from the lateral vaginal walls and posterior fornix using standard swabs (eSwab®; Copan Diagnostics, Murietta, CA, USA). The swabs were immediately transferred to the laboratory at 4℃.

Isolation of LAB from vaginal fluid

Human vaginal fluid was spread onto de Man–Rogosa–Sharpe (MRS) agar (BD Biosciences) and incubated at 37℃ for 72 h. After incubation, each colony was isolated and further cultured on MRS agar supplemented with 0.0035% (w/v) bromocresol purple to investigate acid production. The acid-producing colonies were subsequently purified from the newly prepared MRS. Single and pure colonies were identified as gram-positive, catalase-negative, rod-type strains. The isolated strains were designated LM1202–LM1219 and identified as L. plantarum through 16S Rrna sequencing. A total of 18 strains were stored in MRS containing 10% glycerol at -80℃ until use.4

Screening of antimicrobial effects of isolated strains

The antimicrobial effects of the isolates were assessed by evaluating the inhibition zone,9 minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC),4,9,10 and biofilm inhibition rate.9 Isolated strains were cultured in MRS broth and sub-cultured three times at 12-h intervals. C. albicans and G. vaginalis were cultured in YM and BHYMG broths, respectively.

To measure the inhibition zones of L. plantarum strains, 5 µL of each L. plantarum culture spotted on MRS agar and incubated at 37℃ for 24 h. After incubation, 7 mL of YM or BHYMG agar were overlaid on the isolated L. plantarum colonies and solidified for 30 min. Approximately 7 Log CFU/mL of C. albicans were spread on YM-overlaid MRS agar, and 8 Log CFU/mL of G. vaginalis were spread on BHYMG-overlaid MRS agar. Inhibition zones were measured around L. plantarum colonies after 24 h of incubation.

The MIC values were determined using the cell-free supernatant (CFS) of L. plantarum. The CFSs were prepared by centrifugation at 10000×g at 4℃ for 10 min. After centrifugation, each supernatant was filtered using a 0.45-µm cellulose acetate membrane filter. The filtrates were diluted two-fold in YM or BHYMG broth in a 96-well microplate. After dilution, approxi-mately 6 Log CFU/mL of C. albicans or G. vaginalis were added to each well and incubated for 24 h. MIC was determined as the lowest concentration that visually inhibited fungal or bacterial growth.

To investigate biofilm inhibition, approximately 6 Log CFU/mL of C. albicans were in-cubated with 12.5% CFS in a 96-well microplate at 24℃ for 24 h. After incubation, biofilms were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and dried at 37℃ for 30 min. The rate of biofilm formation was determined through crystal violet staining for 30 min. The crystal violet in mature biofilms was extracted using 100% ethanol and quantified using a microplate reader (SpectraMax iD3; Molecular Devices, San Jose, CA, USA).

Microbial growth curve

The growth rates of C. albicans and G. vaginalis with CFS or L. plantarum strains were estimated as previously described,10 with minor modifications. Briefly, approximately 5 Log CFU/mL of C. albicans or 6 Log CFU/mL of G. vaginalis were incubated with CFS or planktonic cells of L. plantarum. Viable C. albicans cells were enumerated on YM agar (for CFS-treated) and YM agar containing 10% of citric acid (for planktonic cell-treated). The viability of G. vaginalis treated with CFS was assessed on BHYMG agar plates. The number of viable L. plantarum strains was determined on MRS agar plates.

Tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle activity

Inhibition of the TCA cycle in C. albicans and G. vaginalis was measured as formazan, which is related to a reduction in INT.4,9,10 Each microorganism was incubated with 25% CFS to inhibit the TCA cycle. After incubation, the cells were harvested by centrifugation at 10000×g at 4℃ for 10 min, washed twice with PBS, and diluted to an OD600 of 0.2. Subsequently, 1 mM of INT solution was added, and INT reduction was performed at 37℃ for 30 min. After the reaction, the absorbance of formazan was measured at 630 nm using a microplate reader.

Biofilm regulation

Inhibition of biofilm formation and eradication of mature biofilm9 were assessed to elucidate the biofilm regulation of L. plantarum.

Inhibition of biofilm formation was performed as described in the previous section (screening of antimicrobial effects of isolated strains). The CFS treatment ranges were determined as 6.25, 12.5, and 25%.

Approximately 6 Log CFU/Ml of C. albicans were added to a 96-well microplate and incubated for 24 h. After incubation, the mature biofilm was washed with PBS, and planktonic cells were removed. The washed biofilm was treated with each CFS and further incubated for 24 h. Eradication of the mature biofilm was evaluated using crystal violet, as described above.

Cellular damage measurement

Cellular damage to G. vaginalis was assessed by bacterial metabolic activity using the resazurin indicator,11 cellular membrane damage using the NPN fluorescence indicator,10 and bacterial protein analysis using sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE).12 G. vaginalis was incubated with the MIC of CFS at 37℃ for 24 h under anaerobic conditions. After incubation, G. vaginalis was harvested by centrifugation at 10000×g at 4℃ for 10 min, washed twice with PBS, and subjected to cellular damage analysis.

The CFS-treated G. vaginalis was diluted to an OD600 of 0.2 and reacted with 30 µg/mL of resazurin at 37℃ for 30 min. The reduction of resazurin to resorufin was measured using a microplate reader with excitation and emission wavelengths of 540 and 590 nm, respectively.

To measure cellular membrane damage, CFS-treated G. vaginalis was incubated with 10 µM of NPN and incubated at 24℃ for 30 min. The absorption of NPN was measured using a microplate reader at an excitation wavelength of 340 nm and an emission wavelength of 420 nm.

The bacterial proteins were extracted using B-PER™ Bacterial Protein Extraction Reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The lysed bacterial cells were centrifuged at 13000×g at 4℃ for 30 min, and the supernatants were collected for protein analysis. Protein concentration was measured using the Pierce™ BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). SDS-PAGE was performed on a 15% resolving gel with a 5% stacking gel. Briefly, 20 µg of proteins were separated in acrylamide gel and stained Coomassie Brilliant Blue R-250 solution (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) four times at 30-min intervals. After staining, Coomassie Brilliant Blue R-250 Destaining Solution (Bio-Rad Laboratories) was used to visualize the proteins. SDS-PAGE was visualized using the FastGene® GelPic LED Box (Nippon Genetics Europe, Düren, Germany).

Microscopic observation

CFS-induced cellular damage to G. vaginalis was observed through field-emission scanning electron microscopy (FE-SEM) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM). For FE-SEM observations, CFS-treated G. vaginalis were harvested by centrifugation (10000×g at 4℃ for 10 min) and fixed with Karnovsky’s fixative solution at 4℃. The fixed cells were washed with 50-mM sodium cacodylate buffer and further fixed with 1% osmium tetroxide (OsO4) dissolved in 100-mM sodium cacodylate buffer at 4℃ for 1 h. After fixation, excess OsO4 was removed, and dehydration was performed using 30%, 50%, 70%, 80%, 90%, and 100% ethanol for 20 min. The cells were visualized using an FE-SEM (JSM-6700F, JEOL, Tokyo, Japan).9

For TEM observation, the fixed cells were washed with distilled water and stained using 0.5% uranyl acetate (in water) at 4℃ for overnight. After staining, the samples were washed with distilled water and dehydrated in 30%, 50%, 70%, 80%, 90%, and 100% ethanol for 20 min. The dehydrated samples were immersed in propylene oxide twice for 15 min, followed by a mixture of propylene oxide and Spurr’s resin (1:1) for 2 h, propylene oxide and Spurr’s resin (1:2) for 2 h, Spurr’s resin at 4℃ for 24 h, and Spurr’s resin at 25℃ for 3 h, consecutively. Each sample was polymerized at 70℃ for 24 h and sectioned using an ultra-microtome (EM UC7; Leica, Wetzlar, Germany). The thinly sliced sections were subjected to TEM (JEM1010, JEOL).13

Probiotics properties

The essential probiotic properties, including resistance to gastric conditions and bile salts, adhesion to intestinal4 and vaginal14 epithelial cells, and auto-aggregation and hydrophobicity to hexadecane,5 were measured as previously described.

Cultured L. plantarum LM1203, LM1209, and LM1215 were incubated in MRS containing 0.3% pepsin or 0.1% oxgall at 37℃ for 2 h (for measuring pepsin resistance) and 24 h (for measuring bile salt resistance), respectively. After incubation, the viable cells were spread onto MRS agar. L. plantarum ATCC 14917 (type strain) was used as a control.

For investigating adhesion to epithelial cells, HT-29 intestinal epithelial cells and VK2/E6E7 were used (ATCC). HT-29 cells were maintained in Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI) 1640 medium (Gibco, Waltham, MA, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin solution at 37℃ in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. VK2/E6E7 cells were maintained in keratinocyte serum-free medium supplemented with keratinocyte supplements composed of bovine pituitary extract and human recombinant epidermal growth factor (EGF) (Gibco). During incubation, the medium was refreshed every 2–3 days, and each cell line was grown to 80% confluence. Once the cell lines reached 80% confluence, adherent cells were trypsinized with trypsin-ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid solution (0.25%) and harvested by centrifugation. The harvested cells were seeded in 24-well plates (1×105 cells/well) and incubated in different media to form a monolayer. Cultured L. plantarum LM1203, LM1209, and LM1215 were diluted to approximately 8 Log CFU/mL, and the HT-29 or VK2/E6E7 monolayers were treated with these diluted L. plantarum strains for 2 h without antibiotics. After 2 h, non-adherent bacterial cells were removed by washing with PBS, and adherent bacterial cells were collected using a 1% (v/v) Triton-X solution. Adherent bacterial cells were spread on MRS agar, and viable cells were estimated. L. plantarum ATCC 14917 was used as a control.

Cultured L. plantarum was harvested by centrifugation (10000×g at 4℃ for 10 min) and washed twice with PBS. The washed cells were resuspended in PBS and adjusted to an OD600 of 0.5. To evaluate auto-aggregation, the adjusted suspension was allowed to stand and incubated at 37℃. The upper suspension was collected, and the absorbance was measured at 600 nm. Auto-aggregation was calculated and compared to that at 0 h. To evaluate hydrophobicity, 2 Ml of adjusted suspension was mixed with 1 Ml of hexadecane. The mixture was incubated at 25℃ for 30 min. After incubation, the aqueous phase was separated, and its absorbance was measured at 600 nm. Hydrophobicity was calculated and compared to that at 0 min. L. plantarum ATCC 14917 was used as a control.

Antibiotics resistance and hemolysis

Antibiotic resistance was evaluated according to the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) guidelines. Susceptibilities to ampicillin, chloramphenicol, clindamycin, erythromycin, gentamicin, kanamycin, and tetracycline were measured using ETEST® strips (bioMérieux, Marcy-l’Étoile, France) and interpreted based on cut-off values.

Hemolysis was assessed on Columbia blood agar (Oxoid, Basingstoke, United Kingdom) containing 5% sheep blood.4

Genome analysis

Extraction of genomic DNA (gDNA) and genome analysis

Cultured L. plantarum LM1215 was harvested by centrifugation (10000×g at 4℃ for 10 min) and washed with PBS. The gDNA was extracted using the TaKaRa MiniBEST Bacteria Genomic DNA Extraction Kit (Takara Bio, Kusatsu, Japan) according to the manufacturer’s guidelines.

A DNA library was constructed and sequenced using single-molecule real-time (SMRT) sequencing technology (Pacific Biosciences, Menlo Park, CA, USA). Briefly, 5 µg of gDNA were used for SMRTbell library construction using the SMRTbell Template Prep Kit 1.0 and DNA/Polymerase Binding kit P6. The SMRT library was sequenced with one SMRT cell using C4 chemistry (DNA sequencing reagent 4.0), and 240 min movies were captured for each SMRT cell using the PacBio RS II system by Insilicogen (Yongin, Korea). The genome coverage (depth of coverage) was 195×, and HiFi long-read sequencing was performed for analysis.

Genome assembly was performed using a hierarchical genome assembly process (HGAP) and visualized using Artemis15 and DNAPlotter.16 Coding sequences were predicted using GLIMMER 3.0. Gene ontology (GO) analysis was performed using Blast2GO, and clusters of orthologous groups of protein (COG) were predicted using the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool.

Phylogenetic relationship and average nucleotide identity (ANI) analysis

The phylogenetic relationships of L. plantarum LM1215 were analyzed based on the ortholog gene sequences. Whole genome sequences of L. plantarum, Lactiplantibacillus pentosus, Levilactobacillus brevis, Limosilactobacillus reuteri, Limosilactobacillus fermentum, Lentilactobacillus buchneri, and Leuconostoc citreum were obtained from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) database. Ortholog analysis was performed using OrthoFinder v2.5.517 and species trees were inferred using the STAG algorithm and rooted using the STRIDE algorithm in OrthoFinder. The tree species was illustrated using Dendroscope 3.18

ANI values were calculated using the OrthoANI algorithm19 through EzBioCloud (https://www.ezbiocloud.net/tools/ani). The results of the ANI distance, combined with the Newick tree, were illustrated using the heatmap plot function of TBtools.20

Multiple genome comparison

Eight L. plantarum genomes were compared using MAUVE21 by constructing multiple genome alignments.

Prediction of gene cluster

Antimicrobial secondary metabolite gene clusters were predicted using antiSMASH bacterial version 7.0.22

Detection of antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) and virulence factors

ARGs and virulence factors were analyzed using ResFinder version 4.3.3 (http://genepi.food.dtu.dk/resfinder) and virulence factor database (VFDB).23

Determination of pathogenicity

The pathogenicity of L. plantarum LM1215 was determined using the PathogenFinder.24

Genomic island (GI), insertion sequence (IS), prophage, plasmid related sequence, and CRISPR-Cas

Mobile genetic elements (MGEs) were analyzed using VRprofile2.25 Plasmid-related sequences were analyzed using PlasmidFinder.26 The CRISPR-Cas system was analyzed using CRISPRCasFinder.27

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics version 18 software (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). Mean values were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Tukey’s range test or the Games-Howell post-hoc test. Statistical significance was set at p<0.05.

RESULTS

Antimicrobial effects of L. plantarum isolated from the human vaginal tract

Eighteen strains of L. plantarum were isolated from vaginal fluid. The antimicrobial effects of these strains are listed in Table 1. L. plantarum strains did not inhibit the growth of C. albicans ATCC 11006; however, nine strains inhibited the growth of G. vaginalis ATCC 14018. The three strains with the largest inhibition zones were L. plantarum LM1203 (21 mm), L. plantarum LM1209 (20 mm), and L. plantarum LM1215 (21 mm). The MIC of the CFS against G. vaginalis was 25% for most isolates except for L. plantarum LM1202, which was not effective. All isolates inhibited biofilm formation by C. albicans, irrespective of their growth inhibition capabilities. L. plantarum LM1202 was the most effective at inhibiting biofilm formation (91.44%), while L. plantarum LM1219 was the least effective (64.65%). Based on these results, three strains (L. plantarum LM1203, L. plantarum LM1209, and L. plantarum LM1215) were selected for further investigation.

Table 1. Antimicrobial Properties of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum Against Candida albicans and Gardnerella vaginalis.

| Microorganism | Inhibition zone (mm) | Minimum inhibitory concentration (%) | Biofilm inhibition rate (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C. albicans | G. vaginalis | C. albicans | G. vaginalis | C. albicans | |

| L. plantarum LM1202 | Not effective | Not effective | Not effective | Not effective | 91.44±1.60 |

| L. plantarum LM1203 | Not effective | 21.00±1.63 | Not effective | 25 | 89.26±0.76 |

| L. plantarum LM1204 | Not effective | 18.00±0.82 | Not effective | 25 | 86.11±2.46 |

| L. plantarum LM1205 | Not effective | 16.00±0.82 | Not effective | 25 | 84.67±2.30 |

| L. plantarum LM1206 | Not effective | 16.00±1.41 | Not effective | 25 | 70.18±2.68 |

| L. plantarum LM1207 | Not effective | Not effective | Not effective | 25 | 74.85±7.29 |

| L. plantarum LM1208 | Not effective | Not effective | Not effective | 25 | 66.03±2.55 |

| L. plantarum LM1209 | Not effective | 20.00±0.82 | Not effective | 25 | 72.82±4.58 |

| L. plantarum LM1210 | Not effective | 14.00±2.16 | Not effective | 25 | 88.01±1.36 |

| L. plantarum LM1211 | Not effective | 16.33±2.05 | Not effective | 25 | 86.16±2.77 |

| L. plantarum LM1212 | Not effective | Not effective | Not effective | 25 | 81.03±1.15 |

| L. plantarum LM1213 | Not effective | 18.67±0.47 | Not effective | 25 | 83.83±3.39 |

| L. plantarum LM1214 | Not effective | Not effective | Not effective | 25 | 87.68±0.98 |

| L. plantarum LM1215 | Not effective | 21.00±0.82 | Not effective | 25 | 85.82±0.53 |

| L. plantarum LM1216 | Not effective | Not effective | Not effective | 25 | 77.36±4.57 |

| L. plantarum LM1217 | Not effective | Not effective | Not effective | 25 | 86.48±1.39 |

| L. plantarum LM1218 | Not effective | Not effective | Not effective | 25 | 73.99±1.63 |

| L. plantarum LM1219 | Not effective | Not effective | Not effective | 25 | 64.65±2.81 |

Data are shown as means±standard deviations of three independent experiments.

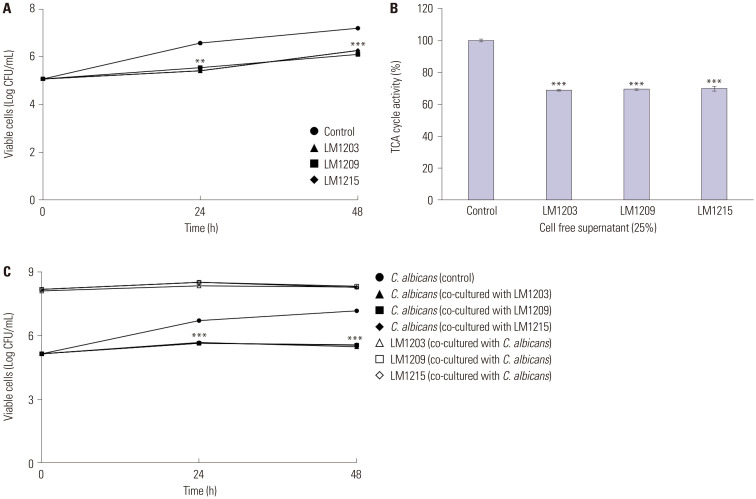

Fungistatic effects of L. plantarum

Fig. 1 shows the impact of L. plantarum and its CFS on the growth rate of C. albicans. The CFS significantly inhibited the growth rate of C. albicans. Specifically, the CFS of L. plantarum LM1203 inhibited C. albicans growth to 5.41 (p<0.01) and 6.26 (p<0.001) Log CFU/mL at 24 h and 48 h, respectively. Similarly, L. plantarum LM1209 and LM1215 inhibited the growth of C. albicans to 6.11 (p<0.001) and 6.26 Log CFU/mL (p<0.001) at 48 h, respectively (Fig. 1A). Conversely, the control (non-treated) cells reached 6.57 and 7.19 Log CFU/mL at 24 h and 48 h, respectively.

Fig. 1. Fungistatic effects and tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle inhibition of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum. (A) Fungistatic effects of cell-free supernatants (CFS). (B) TCA cycle inhibition in Candida albicans through CFS. (C) Cell viability of C. albicans and L. plantarum during co-incubation. Significant differences compared to the control are indicated by asterisks (**p<0.01 and ***p<0.001).

These fungistatic effects were also observed during TCA cycle inhibition (Fig. 1B). TCA cycle activity decreased to 68.81% (CFS of L. plantarum LM1203), 69.37% (CFS of L. plantarum LM1209), and 69.92% (CFS of L. plantarum LM1215) (p<0.001). During co-culture with planktonic cells, cell viabilities of C. albicans were measured at 5.46 (co-cultured with L. plantarum LM1203), 5.54 (co-cultured with L. plantarum LM1209), and 5.55 Log CFU/mL (co-cultured with L. plantarum LM1215) (p<0.001). The planktonic cells of L. plantarum were maintained at 8.28 (L. plantarum LM1203), 8.31 (L. plantarum LM1209), and 8.25 Log CFU/mL (L. plantarum LM1215) (Fig. 1C).

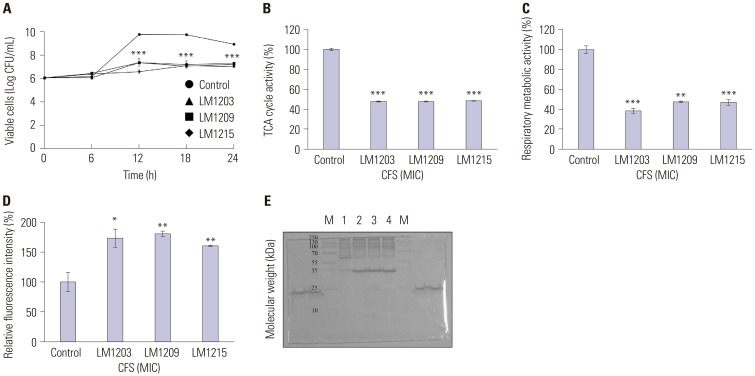

Biofilm regulation by L. plantarum

The regulation of biofilm formation by C. albicans using L. plantarum is shown in Fig. 2. L. plantarum LM1203 CFS at concentrations of 6.25%, 12.50%, and 25% inhibited biofilm formation by 89.77%, 92.44%, and 94.07%, respectively (p<0.001). L. plantarum LM1209 inhibited biofilm formation by 87.30%, 89.97%, and 92.71%, respectively (p<0.001), and L. plantarum LM1215 showed 88.59% (p<0.001), 89.12% (p<0.05), and 91.29% (p<0.001) biofilm inhibition, respectively, at the same concentrations of CFS (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 2. Candida albicans biofilm regulation by Lactiplantibacillus plantarum. (A) Inhibition of biofilm formation. (B) Eradication of mature biofilm. Significant differences compared to the control are indicated by asterisks (*p<0.05, **p<0.01, and ***p<0.001).

As shown in Fig. 2B, L. plantarum effectively removed mature biofilms. L. plantarum LM1203 and L. plantarum LM1215 removed 29.39% (p<0.01) and 33.89% (p<0.001) of mature biofilms, respectively, at CFS concentration of 25%. L. plantarum LM1209 removed 1.31%, 36.43% (p<0.05), and 40.39% (p<0.01) of mature biofilms at CFS concentrations of 6.25%, 12.5%, and 25%, respectively.

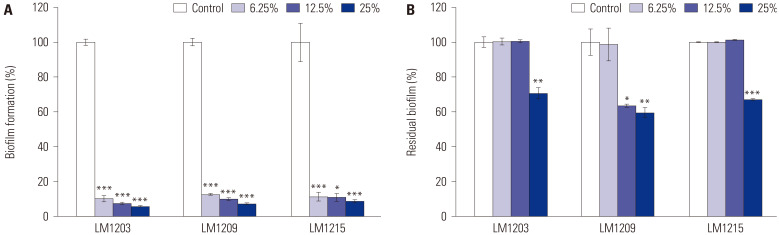

Growth inhibition and bacterial damage in G. vaginalis

The bacterial growth inhibition and membrane damage effects of L. plantarum on G. vaginalis are shown in Fig. 3. The cell viability of the untreated G. vaginalis increased from 6.06 to 8.95 Log CFsystem was analyzed usingU/mL after 24 h. Compared to the control, L. plantarum LM1203, LM1209, and LM1215 reduced G. vaginalis cell growth to 7.24, 7.31, and 7.03 Log CFU/mL, respectively, after 24 h (p<0.001). The TCA cycle activity of G. vaginalis was reduced by 47.83%, 47.69%, and 48.25% to L. plantarum LM1203, LM1209, and LM1215, respectively (p<0.001). Respiratory metabolic activity was reduced by 61.27% (p<0.001), 52.46% (p<0.01), and 52.88% (p<0.001) by L. plantarum LM1203, LM1209, and LM1215, respectively. Furthermore, L. plantarum promoted NPN absorption into the cell membrane of G. vaginalis, resulting in increased fluorescence intensities of 177.33% (L. plantarum LM1203) (p<0.05), 180.96% (L. plantarum LM1209) (p<0.01), and 160.48% (L. plantarum LM1215) (p<0.01). Notably, intracellular proteins (approximately 55 kDa) of damaged G. vaginalis were degraded into smaller proteins (<35 kDa).

Fig. 3. Antibacterial effects of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum against Gardnerella vaginalis. (A) Bacteriostatic effects of L. plantarum. (B) Tricarboxylic acid cycle inhibition by L. plantarum. (C) Inhibition of respiratory metabolism by L. plantarum. (D) N-phenyl-1-naphthylamine uptake in damaged G. vaginalis. (E) Change of cellular proteins in damaged G. vaginalis. (M, protein size marker; 1, Control (non-treated G. vaginalis); 2, CFS of L. plantarum LM1203-treated G. vaginalis; 3, CFS of L. plantarum LM1209-treated G. vaginalis; 4, CFS of L. plantarum LM1215-treated G. vaginalis). Significant differences compared to the control are indicated by asterisks (*p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001). CFS, cell-free supernatants; MIC, minimum inhibitory concentration.

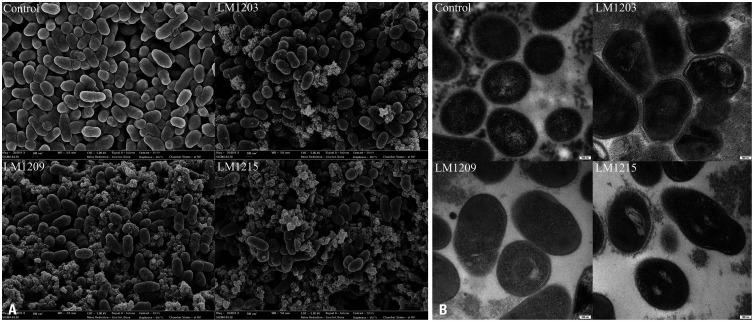

Electron microscope observation

Fig. 4 shows the FE-SEM and TEM images of the damage inflicted by L. plantarum CFS on G. vaginalis. CFS-treated G. vaginalis showed cell surface blebs and wrinkles compared to the control (Fig. 4A). Additionally, CFS-treated G. vaginalis had disrupted cell walls and adopted a hexagonal shape. These structural distortions resulted in the leakage of cellular components (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4. Field-emission scanning electron microscopy (FE-SEM) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM) observation of damaged Gardnerella vaginalis. (A) SEM image of damaged G. vaginalis compared to untreated control cells (30000× magnification). (B) TEM image of damaged G. vaginalis compared to the control cells (20000× magnification).

Probiotic properties

Table 2 summarizes the probiotic properties of L. plantarum strains isolated from the human vaginal tract. After incubation with 0.3% pepsin, L. plantarum LM1203, LM1209, and LM1215 exhibited acid tolerance of 79.63%, 108.33%, and 121.21%, respectively, while L. plantarum ATCC 14917 showed 61.75% acid tolerance. Regarding bile salt resistance, L. plantarum LM1203 exhibited the highest tolerance of 192.17%, followed by L. plantarum LM1209 with 125.74%. L. plantarum LM1215 showed 67.20% of bile salt tolerance and L. plantarum ATCC 14917 showed the lowest value of bile salt tolerance (26.91%). Regarding the adhesion to HT-29 cell, L. plantarum LM1215 showed the highest adherence ratio (6.09%), whereas other strains exhibited 3.40% (LM1203), 3.32% (LM1209), and 2.84% (ATCC 14917). For adherence to VK2/E6E7 cells, L. plantarum LM1203, LM1209, and LM1215 showed adherence rates of 5.00%, 5.04%, and 4.06%, respectively, while L. plantarum ATCC exhibited a rate of 2.98%. L. plantarum LM1209 showed higher auto-aggregation ability (52.34%) than that of L. plantarum ATCC 14917 (47.05%), while L. plantarum LM1203 and LM1215 showed 45.40% and 40.91%, respectively. L. plantarum LM1203 (6.00%), LM1209 (9.38%), and LM1215 (7.91%) showed higher hydrophobicity than that of L. plantarum ATCC 14917 (5.87%).

Table 2. Probiotic Properties of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum Isolated from Human Vaginal Tract.

| Probiotic properties (%) | Microorganisms | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L. plantarum ATCC 14917 | L. plantarum LM1203 | L. plantarum LM1209 | L. plantarum LM1215 | ||

| Resistance | |||||

| Pepsin (0.3) | 61.75±3.69 | 79.63±2.62 | 108.33±4.71 | 121.21±5.67 | |

| Bile salt (0.1) | 26.91±1.20 | 192.17±6.44 | 125.74±2.06 | 67.20±3.43 | |

| Adhesion | |||||

| HT-29 | 2.84±0.18 | 3.40±0.13 | 3.32±0.28 | 6.09±0.12 | |

| VK2/E6E7 | 2.98±0.20 | 5.00±0.21 | 5.04±0.48 | 4.06±0.25 | |

| Auto-aggregation | 47.05±0.91 | 45.10±0.82 | 52.34±0.59 | 40.91±2.10 | |

| Hydrophobicity | 5.87±0.32 | 6.00±1.11 | 9.38±1.13 | 7.91±1.04 | |

Data are shown as means±standard deviations of three independent experiments.

Antibiotics susceptibility and hemolysis

Table 3 presents the antibiotic resistance and hemolysis of L. plantarum. The L. plantarum LM1215 did not exhibit antibiotics resistance, with MICs of 0.094 µg/mL for ampicillin, 1.5 µg/mL for chloramphenicol, 0.016 µg/mL for clindamycin, 0.19 µg/mL for erythromycin, 6 µg/mL for gentamicin, 64 µg/mL for kanamycin, and 4 µg/mL for tetracycline. However, both L. plantarum LM1203 and LM1209 showed kanamycin resistance (MICs >256 µg/mL). Hemolysis was not detected in any of the L. plantarum strains.

Table 3. Antibiotics Susceptibility and Hemolysis of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum Isolated from the Human Vaginal Tract.

| Antibiotic susceptibility | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antibiotic | Cut-off values (μg/mL) | Minimum inhibitory concentration (μg/mL) | ||

| L. plantarum LM1203 | L. plantarum LM1209 | L. plantarum LM1215 | ||

| Ampicillin | 2 | 0.19 | 0.19 | 0.094 |

| Chloramphenicol | 8 | 2 | 2 | 1.5 |

| Clindamycin | 2 | 0.125 | 0.38 | 0.016 |

| Erythromycin | 1 | 0.25 | 0.38 | 0.19 |

| Gentamicin | 16 | 8 | 6 | 6 |

| Kanamycin | 64 | >256 | >256 | 64 |

| Tetracycline | 32 | 3 | 4 | 4 |

| Hemolysis | γ-hemolysis | γ-hemolysis | γ-hemolysis | |

Experiments were conducted in triplicate.

Overall, L. plantarum LM1215 showed antimicrobial effects and probiotic properties. Therefore, further investigations were conducted to analyze its genome.

Complete genome analysis

General genome information

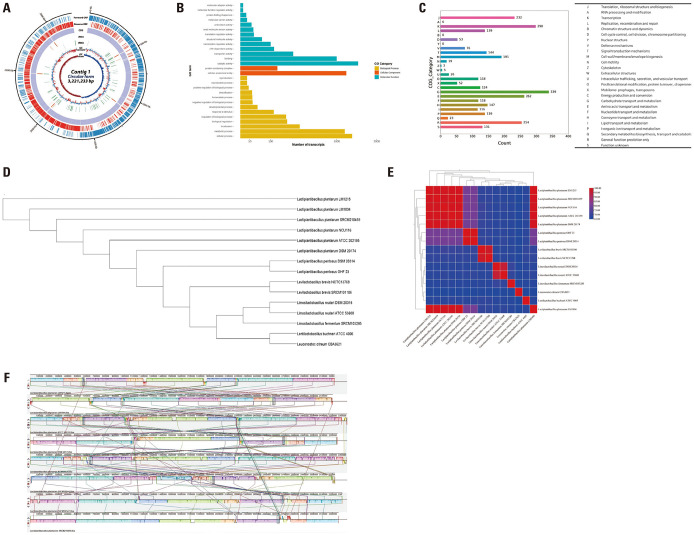

As shown in Fig. 5A, the size of the entire genome sequence of L. plantarum LM1215 was 3221233 bp, with a GC content of 44.62%. Moreover, it contained 3208 protein-coding sequences (CDSs), as well as 16 rRNA and 68 tRNA genes. This Whole Genome project has been deposited in DDBJ/ENA/GenBank under the accession number CP128990.

Fig. 5. General genomic information of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum LM1215. (A) Circular gene map of L. plantarum LM1215. Each circle, from outside to inside, indicates protein-coding sequences (CDS) on the forward strand, CDS on the reverse strand, tRNA, rRNA, GC content, and GC skew. (B) Gene Ontology analysis. (C) Clusters of Orthologous Groups of proteins analysis. (D) Phylogenetic tree based on ortholog gene. (E) Comparison of average nucleotide identity value within the Lactobacillaceae family. (F) Multiple genome alignment and genome comparison of L. plantarum. tRNA, transfer RNA; rRNA, ribosomal RNA; GC content, guanine-cytosine content.

GO and COG analyses

As shown in Fig. 5B, 8687 transcripts were annotated and categorized into 16 biological processes, two cellular components, and 13 molecular function categories. These genes were mainly enriched for catalytic activity (1491 transcripts), cellular processes (1346 transcripts), cellular anatomical entities (1209 transcripts), metabolic processes (1172 transcripts), and binding (1000 transcripts).

According to the COG analysis (Fig. 5C), 3009 CDSs (93.80%) were specifically assigned to clusters of COG families comprising 23 functional categories. Most functional proteins were involved in carbohydrate transport and metabolism (339 CDSs). Other abundant CDSs were classified as transcription (298 CDSs); amino acid transport and metabolism (262 CDSs), general function prediction only (254 CDSs); and translation, ribosomal structure, and biogenesis (232 CDSs).

Phylogenetic orthology and ANI

Fig. 5D and 5E show the phylogenetic relationships and ANI distances of L. plantarum LM1215 compared to those of other LAB. L. plantarum LM1215 was closely associated with other Lactiplantibacillus species (L. plantarum and L. pentosus) and distinct from Levilactobacillus, Limosilactobacillus, Lentilactobacillus, and Leuconostoc. In the ANI distance analysis, L. plantarum LM1215 showed a high genomic similarity to other L. plantarum strains (98.98%–99.96%). Compared with other Lactiplantibacillus, L. pentosus DSM 20314 and L. pentosus OHF 23 showed 80.18% and 80.14% genomic similarity, respectively. Other LAB showed 66.17%–69.08% genomic similarity wih L. plantarum LM1215.

Comparative genome alignments

A comparative genomic analysis of L. plantarum strains is shown in Fig. 5F. Genome rearrangements were observed within L. plantarum, and genome deletions occurred in several strains, including L. plantarum ATCC 202195, DSM 20174, NCIMB8826, SRCM100442, 103472, and SRCM210459. L. plantarum LM1215 was most similar to L. plantarum LM1004, which underwent genome rearrangement without deletions.

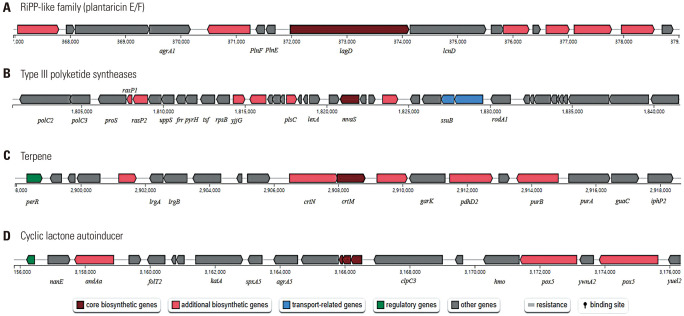

Prediction of gene clusters

Antimicrobial secondary metabolite gene clusters are shown in Fig. 6. L. plantarum LM1215 is predicted to have four types of antimicrobial secondary metabolites: plantaricin E/F, type III polyketide synthases, terpenes, and cyclic lactone autoinducers.

Fig. 6. General gene cluster of antimicrobial secondary metabolites in Lactiplantibacillus plantarum. (A) Prediction of plantaricin E/F gene cluster. (B) Prediction of type III polyketide synthases gene cluster. (C) Prediction of terpene gene cluster. (D) Prediction of cyclic lactone autoinducer gene cluster.

Antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) and virulence factors

As shown in Table 4, intrinsic ARGs and acquired ARGs were not detected in L. plantarum LM1215. Compared to the VFDB, 10 alignments exhibited matching virulence factors with bit scores exceeding 50. However, several alignments, such as sdrE (E-value:4E-49), sdrC (E-value:2E-48), clpC (E-value:3E-10), tufA (E-value:3E-10), hasC (E-value:2E-08), lap (E-value:2E-08), and bsh (E-value:6E-05), exhibited E-values below E-50. Conversely, clfA, clfB, and sdrD genes had E-values of 2E-79, 2E-69, and 7E-51, respectively (Table 5).

Table 4. Intrinsic and Acquired Antibiotic Resistance Genes in Lactiplan tibacillus plantarum LM1215.

| Intrinsic antibiotic resistance genes | |

|---|---|

| Class of antibiotics | Related resistance genes |

| Aminocyclitol | Not detected |

| Aminoglycoside | Not detected |

| Amphenicol | Not detected |

| Diaminopyrimidines | Not detected |

| Glycopeptide | Not detected |

| Ionophores | Not detected |

| β-Lactam | Not detected |

| Lincosamide | Not detected |

| Macrolide | Not detected |

| Nitroimidazole | Not detected |

| Oxazolidinone | Not detected |

| Phosphonic acid derivatives | Not detected |

| Pleuromutilin derivatives | Not detected |

| Polymyxin | Not detected |

| Pseudomonic acid | Not detected |

| Quinolone | Not detected |

| Rifamycin | Not detected |

| Steroid antibacterial agent | Not detected |

| Streptogramin A | Not detected |

| Streptogramin B | Not detected |

| Sulfonamide | Not detected |

| Tetracycline | Not detected |

| Acquired antibiotic resistance genes | Not detected |

Table 5. Detection of Virulence Factor-Related Genes in Lactiplantibacillus plantarum LM1215.

| Genes | Products | Identities | Gaps | Score (bits) | E-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| clfA | Clumping factor A, fibrinogen-binding protein | 438/533 (82) | 6/533 (1) | 305 | 2.00E-79 |

| clfB | Clumping factor B, adhesin | 435/531 (81) | 6/531 (1) | 293 | 6.00E-76 |

| sdrD | Ser-Asp rich fibrinogen-binding bone sialoprotein-binding protein | 354/437 (81) | 6/437 (1) | 210 | 7.00E-51 |

| sdrE | Ser-Asp rich fibrinogen-binding bone sialoprotein-binding protein | 349/431 (80) | - | 204 | 4.00E-49 |

| sdrC | Ser-Asp rich fibrinogen-binding bone sialoprotein-binding protein | 333/410 (81) | - | 202 | 2.00E-48 |

| clpC | Endopeptidase Clp ATP-binding chain C | 119/146 (81) | - | 76 | 3.00E-10 |

| tufA | Elongation factor Tu | 97/114 (85) | 2/114 (1) | 76 | 3.00E-10 |

| hasC | UTP--glucose-1-phosphate uridylyltransferase HasC | 71/83 (85) | - | 70 | 2.00E-8 |

| lap | Listeria adhesion protein Lap | 62/71 (87) | - | 70 | 2.00E-8 |

| bsh | Bile salt hydrolase | 65/77 (84) | - | 58 | 6.00E-5 |

Pathogenicity

As shown in Table 6, L. plantarum LM1215 was not identified as a pathogen. Fourteen non-pathogenic proteins were matched to those of other LAB, including Pediococcus pentosaceus ATCC 25745, Leuconostoc mesenteroides spp. mesenteroides ATCC 8293, Leuconostoc kimchii IMSNU 11154, Oenococcus oeni PSU-1, and L. reuteri Lc 705.

Table 6. The Prediction Probability of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum LM1215 as a Human Pathogen.

| Human pathogen prediction | Non-pathogenic bacteria | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Probability of a human pathogen | 0.189 | |||

| Matched pathogenic families | 0 | |||

| Matched non-pathogenic families | 14 | |||

| Matched sequence detail | ||||

| Start | End | Matched microorganisms | Matched protein | Identity (%) |

| 174186 | 176345 | Pediococcus pentosaceus ATCC 25745 | α-Galactosidase | 98.19 |

| 333957 | 334403 | Leuconostoc mesenteroides spp. mesenteroides ATCC 8293 | Ribonuclease HI | 98.65 |

| 337217 | 338548 | Leuconostoc kimchii IMSNU 11154 | Glutathione reductase | 100 |

| 1849138 | 1849470 | Pediococcus pentosaceus ATCC 25745 | Head-tail connector protein | 91.82 |

| 1851679 | 1852704 | Pediococcus pentosaceus ATCC 25745 | Hypothetical protein | 97.07 |

| 1852891 | 1854789 | Pediococcus pentosaceus ATCC 25745 | Phage terminase-like protein, large subunit | 93.83 |

| 1854792 | 1855250 | Pediococcus pentosaceus ATCC 25745 | Phage terminase, small subunit | 90.79 |

| 3039746 | 3040066 | Oenococcus oeni PSU-1 | Thiol-disulfide isomerase and thioredoxin | 100 |

| 3036552 | 3038456 | Oenococcus oeni PSU-1 | Cation transport ATPase | 98.11 |

| 3040090 | 3040359 | Oenococcus oeni PSU-1 | Metal-sensitive transcriptional regulator | 97.75 |

| 3040760 | 3041314 | Oenococcus oeni PSU-1 | DNA-binding ferritin-like protein (oxidative damage protectant) | 95.65 |

| 3041749 | 3042414 | Oenococcus oeni PSU-1 | Crp-like transcriptional regulator | 98.64 |

| 3081284 | 3083164 | Limosilactobacillus reuteri Lc 705 (plasmid) | β-galactosidase (GH42) | 99.52 |

| 3083148 | 3083492 | Limosilactobacillus reuteri Lc 705 (plasmid) | β-galactosidase small subunit | 100 |

Horizontal gene transfer (HGT)

Table 7 summarizes the presence of GIs, ISs, prophages, plasmid-related sequences, and the CRISPR-Cas system in L. plantarum LM1215. L. plantarum LM1215 contained seven GIs, five ISs, and five prophages; however, these MGEs did not carry ARGs or virulence factors. No plasmid-related sequences were detected in L. plantarum LM1215, which possessed a CRISPR sequence with evidence level 1.

Table 7. Mobile Genetic Elements, Plasmid Related Sequence, and CRISPR-Cas in Lactiplantibacillus plantarum LM1215.

| Mobile genetic elements | Details | Start | End | GC contents (%) | ARGs | Virulence genes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genomic island | - | 351044 | 378900 | 40.07 | Not detected | Not detected | |

| Genomic island | - | 570297 | 590667 | 50.78 | Not detected | Not detected | |

| Genomic island | - | 1028102 | 1044143 | 36.83 | Not detected | Not detected | |

| Genomic island | - | 2792187 | 2805572 | 38.89 | Not detected | Not detected | |

| Insertion sequence/Transposon | ISP1 | 537345 | 538607 | 39.94 | Not detected | Not detected | |

| Insertion sequence/Transposon | ISLpl2 | 822165 | 822713 | 42.52 | Not detected | Not detected | |

| Insertion sequence cluster/Transposon | ISP1/ISP1 | 1024558 | 1025618 | 40.28 | Not detected | Not detected | |

| Insertion sequence/Transposon | ISP1 | 1756417 | 1757679 | 40.02 | Not detected | Not detected | |

| Insertion sequence/Transposon | ISP2 | 2779405 | 2780898 | 41.66 | Not detected | Not detected | |

| Prophage | - | 549799 | 560673 | 43.98 | Not detected | Not detected | |

| Prophage | - | 1192545 | 1230073 | 41.41 | Not detected | Not detected | |

| Prophage | - | 1826999 | 1882244 | 41.85 | Not detected | Not detected | |

| Prophage | - | 2145402 | 2218664 | 41.69 | Not detected | Not detected | |

| Prophage | - | 2406578 | 2413360 | 49.09 | Not detected | Not detected | |

| Plasmid related sequence | |||||||

| Inc18 | RepA_N | Rep3 | Pep_trans | Rep2 | NT_Rep | Rep1 | RepL |

| Not detected | Not detected | Not detected | Not detected | Not detected | Not detected | Not detected | Not detected |

| CRISPR | |||||||

| Start | End | Direction | Consensus repeat | Number of repeats | Number of spacers | Evidence level | |

| 2742366 | 2742451 | Unknown | TAAGAAACTTAAAGTGTCTTATT | 2 | 1 | 1 | |

DISCUSSION

To date, clinical studies have been conducted on BV and VVC to establish the beneficial effects of probiotics using different types and routes. L.crispatus containing vaginal probiotics has been found to be clinically effective and safe to prevent the recurrence of BV in a phase 2b trial in which vaginal probiotics were administered to women who had completed a course of vaginal antibiotics gel during 11 weeks.28 The recurrence rate of BV was significantly decreased by 34% at week 12% and 27% at week 24 in the group using L. crispatus compared to the placebo group.28 A randomized clinical trial of a short-duration of administration of L. acidophilus containing vaginal probiotics showed no additional beneficial effects on long-term BV recurrence after the completion of antibiotics.29 A recent meta-analysis, including 17 randomized controlled trials on the treatment of BV, revealed that probiotics adjunctive to antibiotics were more effective than antibiotics alone, and probiotics were significantly more effective than placebo.30 A few clinical trials were conducted on VVC compared to BV. L. gasseri containing vaginal probiotics31 or L. acidiophilus32 have not been found to have any beneficial effects on recurrent VVC, and meta-analyses did not show definitive findings due to a limited number of clinical studies of probiotics on recurrent VVC.33,34

C. albicans is a biofilm-forming yeast,3 commonly found in patients with VVC, whereas other non-albicans Candida infections are considered minor infections of the vaginal tract.3,35 These biofilms facilitate surface adhesion and enhance resistance to environmental stressors, host immune responses, and therapeutic agents.36 Moreover, biofilm formation can lead to histological damage in mucosal epithelial cells and local inflammation in the vaginal epithelium. Another significant concern is that biofilms hinder the efficacy of antifungal agents in VVC treatment.35 Sun, et al.37 reported that azole compounds, such as clotrimazole, up-regulate efflux pumps within biofilms and extracellular matrices, whereas the presence of β-glucan within biofilms inhibits the effectiveness of amphotericin B, a polyene antifungal agent. Thus, controlling C. albicans biofilm formation is crucial for VVC treatment and the development of natural antifungal agents. In this study, L. plantarum LM1203, LM1209, and LM1215 exhibited fungistatic (Fig. 1) and biofilm removal (Fig. 2) effects.

LAB produce a wide range of antimicrobial metabolites that depolarize membranes,38,39 inhibit cell wall enzyme synthesis,38 cause cell wall lysis,39 damage proteins and nucleic acids through protonated acids,38,40 generate oxidative stress through the accumulation of reactive oxygen species,38 and reduce intracellular ATP levels.39 Similarly, LAB produce antifungal metabolites that induce cell surface distortions, disrupt the hyphae of fungal cells, and induce the leakage of cytoplasmic content.40 As shown in Fig. 6, L. plantarum LM1215 was predicted to have four types of antimicrobial secondary metabolite production gene clusters. One of these clusters encodes for plantaricin E/F, a two-peptide bacteriocin consisting of plnE and plnF.41,42 Plantaricin E/F acts as an antagonist against gram-positive bacteria and fungi,41 and is more effective than plantaricin A.42 Gram-positive bacteria subjected to plantaricin E/F exhibit cell membrane damage and dissipation of cellular proton motive forces, ultimately resulting in cell death.43 Therefore, the fungistatic (Fig. 1) and bacteriostatic effects, as well as cellular membrane damage (Figs. 3 and 4) observed in this study may be attributed to the action of plantaricin E/F produced by L. plantarum LM1215. Additionally, aromatic polyketides, terpenes, and cyclic lactone autoinducers have been predicted in L. plantarum LM1215. These genetic properties contributed to the regulation of C. albicans and G. vaginalis by L. plantarum LM1215.

Probiotics are generally regarded as safe for dietary consumption; however, recent studies have raised concerns about the emergence of antibiotic-resistant non-pathogenic bacteria.44 Antibiotic resistance is classified as intrinsic or acquired, with the latter often resulting from HGT between different bacterial genera via conjugation, transformation, and transduction.45,46 LAB are intrinsically resistant to certain antibiotic classes, including aminoglycosides, quinolones, and diaminopyrimidines. Moreover, Lactiplantibacillus spp. are generally resistant to vancomycin. Furthermore, conjugation can occur between LAB and other pathogenic bacteria via conjugation pili.46 Considering these concerns, the EFSA recommends comprehensive screening for ARGs using whole-genome sequencing when probiotics are used in humans and animals.45,46 In the present study, L. plantarum LM1215 did not possess any intrinsic or acquired ARGs, including MGEs. Additionally, L. plantarum LM1215 possesses a CRISPR-Cas system, which acts as a defense mechanism against HGT in bacteria.47 Thus, L. plantarum LM1215 is considered a safe probiotic agent suitable for the prevention of VVC and BV.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by the Korea Institute of Planning and Evaluation for Technology in Food, Agriculture, Forestry (IPET) through (High Value-added Food Technology Development Pro-gram), funded by Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs (MAFRA) (Grant Number 121026-3).

The microscopic images were supported by Professor Younghoon Kim in Seoul National University.

Footnotes

The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

- Conceptualization: Won-Young Bae.

- Data curation: So Lim Shin and Tae-Rahk Kim.

- Formal Analysis: Won-Young Bae and Subin Jo.

- Funding acquisition: Tae-Rahk Kim.

- Investigation: Won-Young Bae and Young Jin Lee.

- Methodology: Won-Young Bae, Young Jin Lee and Hyun-Joo Seol.

- Project Administration: Tae-Rahk Kim and Hyun-Joo Seol.

- Resources: Subin Jo and Hyun-Joo Seol.

- Supervision: Minn Sohn.

- Validation: all authors.

- Visualization: Won-Young Bae.

- Writing—original draft: Won-Young Bae and Hyun-Joo Seol.

- Writing—review & editing: Young Jin Lee, Subin Jo, So Lim Shin, Tae-Rahk Kim, and Minn Sohn.

- Approval of final manuscript: all authors.

References

- 1.Saraf VS, Sheikh SA, Ahmad A, Gillevet PM, Bokhari H, Javed S. Vaginal microbiome: normalcy vs dysbiosis. Arch Microbiol. 2021;203:3793–3802. doi: 10.1007/s00203-021-02414-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim H, Kim Y, Kang CH. In vivo confirmation of the antimicrobial effect of probiotic candidates against Gardnerella vaginalis. Microorganisms. 2021;9:1690. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms9081690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McKloud E, Delaney C, Sherry L, Kean R, Williams S, Metcalfe R, et al. Recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis: a dynamic interkingdom biofilm disease of Candida and Lactobacillus. mSystems. 2021;6:e0062221. doi: 10.1128/mSystems.00622-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bae WY, Lee YJ, Jung WH, Shin SL, Kim TR, Sohn M. Draft genome sequence and probiotic functional property analysis of Lactobacillus gasseri LM1065 for food industry applications. Sci Rep. 2023;13:12212. doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-39454-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chow K, Wooten D, Annepally S, Burke L, Edi R, Morris SR. Impact of (recurrent) bacterial vaginosis on quality of life and the need for accessible alternative treatments. BMC Womens Health. 2023;23:112. doi: 10.1186/s12905-023-02236-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mendling W, Holzgreve W. Astodrimer sodium and bacterial vaginosis: a mini review. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2022;306:101–108. doi: 10.1007/s00404-022-06429-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yilmaz B, Bangar SP, Echegaray N, Suri S, Tomasevic I, Manuel Lorenzo J, et al. The impacts of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum on the functional properties of fermented foods: a review of current knowledge. Microorganisms. 2022;10:826. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms10040826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rocchetti MT, Russo P, Capozzi V, Drider D, Spano G, Fiocco D. Bioprospecting antimicrobials from Lactiplantibacillus plantarum: key factors underlying its probiotic action. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:12076. doi: 10.3390/ijms222112076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bae WY, Jung WH, Lee YJ, Shin SL, An YK, Kim TR, et al. Heat-treated Pediococcus acidilactici LM1013-mediated inhibition of biofilm formation by Cutibacterium acnes and its application in acne vulgaris: a single-arm clinical trial. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2023;22:3125–3134. doi: 10.1111/jocd.15809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bae WY, Kim HY, Yu HS, Chang KH, Hong YH, Lee NK, et al. Antimicrobial effects of three herbs (Brassica juncea, Forsythia suspensa, and Inula britannica) on membrane permeability and apoptosis in Salmonella. J Appl Microbiol. 2021;130:394–404. doi: 10.1111/jam.14800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ouyang X, Hoeksma J, van der Velden G, Beenker WAG, van Triest MH, Burgering BMT, et al. Berkchaetoazaphilone B has antimicrobial activity and affects energy metabolism. Sci Rep. 2021;11:18774. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-98252-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huang Z, Jia S, Zhang L, Liu X, Luo Y. Inhibitory effects and membrane damage caused to fish spoilage bacteria by cinnamon bark (Cinnamomum tamala) oil. LWT. 2019;112:108195 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yoo JH, Baek KH, Heo YS, Yong HI, Jo C. Synergistic bactericidal effect of clove oil and encapsulated atmospheric pressure plasma against Escherichia coli O157:H7 and Staphylococcus aureus and its mechanism of action. Food Microbiol. 2021;93:103611. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2020.103611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pino A, Rapisarda AMC, Vitale SG, Cianci S, Caggia C, Randazzo CL, et al. A clinical pilot study on the effect of the probiotic Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus TOM 22.8 strain in women with vaginal dysbiosis. Sci Rep. 2021;11:2592. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-81931-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carver T, Harris SR, Berriman M, Parkhill J, McQuillan JA. Artemis: an integrated platform for visualization and analysis of high-throughput sequence-based experimental data. Bioinformatics. 2012;28:464–469. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carver T, Thomson N, Bleasby A, Berriman M, Parkhill J. DNAPlotter: circular and linear interactive genome visualization. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:119–120. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Emms DM, Kelly S. OrthoFinder: phylogenetic orthology inference for comparative genomics. Genome Biol. 2019;20:238. doi: 10.1186/s13059-019-1832-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huson DH, Scornavacca C. Dendroscope 3: an interactive tool for rooted phylogenetic trees and networks. Syst Biol. 2012;61:1061–1067. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/sys062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yoon SH, Ha SM, Lim J, Kwon S, Chun J. A large-scale evaluation of algorithms to calculate average nucleotide identity. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 2017;110:1281–1286. doi: 10.1007/s10482-017-0844-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen C, Chen H, Zhang Y, Thomas HR, Frank MH, He Y, et al. TB-tools: an integrative toolkit developed for interactive analyses of big biological data. Mol Plant. 2020;13:1194–1202. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2020.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Darling AC, Mau B, Blattner FR, Perna NT. Mauve: multiple alignment of conserved genomic sequence with rearrangements. Genome Res. 2004;14:1394–1403. doi: 10.1101/gr.2289704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Blin K, Shaw S, Augustijn HE, Reitz ZL, Biermann F, Alanjary M, et al. AntiSMASH 7.0: new and improved predictions for detection, regulation, chemical structures and visualisation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023;51:W46–W50. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkad344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu B, Zheng D, Zhou S, Chen L, Yang J. VFDB 2022: a general classification scheme for bacterial virulence factors. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022;50:D912–D917. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkab1107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cosentino S, Voldby Larsen M, Møller Aarestrup F, Lund O. PathogenFinder--distinguishing friend from foe using bacterial whole genome sequence data. PLoS One. 2013;8:e77302. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0077302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang M, Goh YX, Tai C, Wang H, Deng Z, Ou HY. VRprofile2: detection of antibiotic resistance-associated mobilome in bacterial pathogens. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022;50:W768–W773. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkac321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carattoli A, Zankari E, García-Fernández A, Voldby Larsen M, Lund O, Villa L, et al. In silico detection and typing of plasmids using PlasmidFinder and plasmid multilocus sequence typing. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014;58:3895–3903. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02412-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Couvin D, Bernheim A, Toffano-Nioche C, Touchon M, Michalik J, Néron B, et al. CRISPRCasFinder, an update of CRISRFinder, includes a portable version, enhanced performance and integrates search for Cas proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:W246–W251. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cohen CR, Wierzbicki MR, French AL, Morris S, Newmann S, Reno H, et al. Randomized trial of lactin-V to prevent recurrence of bacterial vaginosis. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1906–1915. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1915254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bradshaw CS, Pirotta M, De Guingand D, Hocking JS, Morton AN, Garland SM, et al. Efficacy of oral metronidazole with vaginal clindamycin or vaginal probiotic for bacterial vaginosis: randomised placebo-controlled double-blind trial. PLoS One. 2012;7:e34540. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen R, Li R, Qing W, Zhang Y, Zhou Z, Hou Y, et al. Probiotics are a good choice for the treatment of bacterial vaginosis: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trial. Reprod Health. 2022;19:137. doi: 10.1186/s12978-022-01449-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Witt A, Kaufmann U, Bitschnau M, Tempfer C, Ozbal A, Haytouglu E, et al. Monthly itraconazole versus classic homeopathy for the treatment of recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis: a randomised trial. BJOG. 2009;116:1499–1505. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2009.02262.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mollazadeh-Narestan Z, Yavarikia P, Homayouni-Rad A, Samadi Kafil H, Mohammad-Alizadeh-Charandabi S, Gholizadeh P, et al. Comparing the effect of probiotic and fluconazole on treatment and recurrence of vulvovaginal candidiasis: a triple-blinded randomized controlled trial. Probiotics Antimicrob Proteins. 2023;15:1436–1446. doi: 10.1007/s12602-022-09997-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.van de Wijgert J, Verwijs MC. Lactobacilli-containing vaginal probiotics to cure or prevent bacterial or fungal vaginal dysbiosis: a systematic review and recommendations for future trial designs. BJOG. 2020;127:287–299. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.15870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cooke G, Watson C, Deckx L, Pirotta M, Smith J, van Driel ML. Treatment for recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis (thrush) Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2022;1:CD009151. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009151.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sabbatini S, Visconti S, Gentili M, Lusenti E, Nunzi E, Ronchetti S, et al. Lactobacillus iners cell-free supernatant enhances biofilm formation and hyphal/pseudohyphal growth by Candida albicans vaginal isolates. Microorganisms. 2021;9:2577. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms9122577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bapat P, Singh G, Nobile CJ. Visible lights combined with photosensitizing compounds are effective against Candida albicans biofilms. Microorganisms. 2021;9:500. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms9030500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sun C, Zhao X, Jiao Z, Peng J, Zhou L, Yang L, et al. The antimicrobial peptide AMP-17 derived from Musca domestica inhibits biofilm formation and eradicates mature biofilm in Candida albicans. Antibiotics (Basel) 2022;11:1474. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics11111474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zapaśnik A, Sokołowska B, Bryła M. Role of lactic acid bacteria in food preservation and safety. Foods. 2022;11:1283. doi: 10.3390/foods11091283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kaveh S, Hashemi SMB, Abedi E, Amiri MJ, Conte FL. Bio-preservation of meat and fermented meat products by lactic acid bacteria strains and their antibacterial metabolites. Sustainability. 2023;15:10154 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mani-López E, Arrioja-Bretón D, López-Malo A. The impacts of antimicrobial and antifungal activity of cell-free supernatants from lactic acid bacteria in vitro and foods. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf. 2022;21:604–641. doi: 10.1111/1541-4337.12872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li Z, Cheng Q, Guo H, Zhang R, Si D. Expression of hybrid peptide EF-1 in Pichia pastoris, its purification, and antimicrobial characterization. Molecules. 2020;25:5538. doi: 10.3390/molecules25235538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Abdulhussain Kareem R, Razavi SH. Plantaricin bacteriocins: as safe alternative antimicrobial peptides in food preservation—a review. J Food Saf. 2019;40:e12735 [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang Y, Wei Y, Shang N, Li P. Synergistic inhibition of plantaricin E/F and lactic acid against Aeromonas hydrophila LPL-1 reveals the novel potential of class IIb bacteriocin. Front Microbiol. 2022;13:774184. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.774184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang K, Zhang H, Feng J, Ma L, de la Fuente-Núñez C, Wang S, et al. Antibiotic resistance of lactic acid bacteria isolated from dairy products in Tianjin, China. J Agric Food Res. 2019;1:100006 [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nunziata L, Brasca M, Morandi S, Silvetti T. Antibiotic resistance in wild and commercial non-enterococcal lactic acid bacteria and bifidobacteria strains of dairy origin: an update. Food Microbiol. 2022;104:103999. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2022.103999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ojha AK, Shah NP, Mishra V. Conjugal transfer of antibiotic resistances in Lactobacillus spp. Curr Microbiol. 2021;78:2839–2849. doi: 10.1007/s00284-021-02554-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tao S, Chen H, Li N, Liang W. The application of the CRISPR-Cas system in antibiotic resistance. Infect Drug Resist. 2022;15:4155–4168. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S370869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]