Abstract

The tobacco epidemic has claimed countless lives, caused significant morbidity, and cost billions of dollars in direct costs and lost productivity. Despite its acute vascular effects, nicotine alone has not been definitively linked to cardiovascular events. Rather, additives found in cigarettes and other tobacco products likely play a bigger role in tobacco’s link to cardiovascular events. The emergence of electronic nicotine delivery systems introduces a new challenge, particularly among certain groups. Understanding the groups vulnerable to tobacco product use, identifying factors that influence this vulnerability, and examining different approaches to mitigating these factors is imperative to curbing the detrimental effects of the tobacco epidemic. Ameliorating screening and treatment efforts will require collaborative efforts that involve clinicians, health care systems, local and regional communities, government agencies, policymakers, and medical societies.

Key words: prevention, smoking, screening, tobacco, vulnerable populations

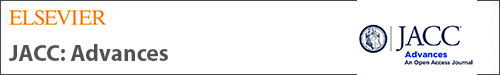

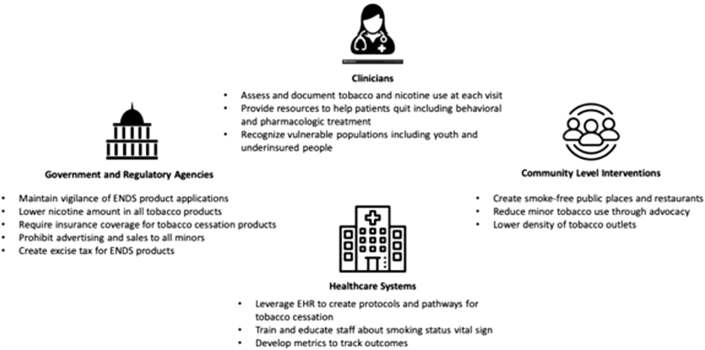

Central Illustration

Highlights

-

•

Tobacco use disproportionately impacts certain vulnerable populations.

-

•

Use of ENDS is increasing.

-

•

Tobacco and nicotine use assessment screening should routinely include screening for ENDS.

-

•

Successful interventions to reduce tobacco use should include clinicians, health care systems, national and global policymakers, and governmental agencies.

Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death globally.1 Smoking cessation, avoidance of tobacco, and lowering exposure to secondhand smoke are vital interventions to promote cardiovascular health and disease prevention.2 The 2018 American College of Cardiology Expert Consensus Decision Pathway of Tobacco Cessation Treatment focused on treatment pathways for smoking cessation for traditional combustible tobacco products.3 In recent years, use of noncombustible tobacco and nicotine products increased significantly in groups that previously experienced declines in use of combustible tobacco products, including adolescents and young adults. These products target individuals with pre-existing social and health disparities across all age groups.4

This document provides an overview of combustible and noncombustible tobacco and nicotine-containing products, highlights the impact on vulnerable populations, and reviews opportunities to impact smoking cessation and prevention (Central Illustration). This review will inform clinicians with a better understanding of how these factors influence use of tobacco products and provide context for patient education and treatment.

Central Illustration.

Tobacco Use Affects Vulnerable Populations

Overview of currently available tobacco and nicotine-containing products

Tobacco products encompass a wide range of nicotine-containing products, and they have been the driving force behind arguably the most devastating health epidemic of the past century. In recent years, the introduction and widespread availability of noncombustible tobacco products, predominantly electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS), have brought forth a new challenge.1

Cigarettes are the most widely consumed tobacco product worldwide. While dependence on nicotine sustains cigarette smoking, most of the harm comes from the combustion products,5 with similar associated health risks for the various types of combustible tobacco products.6 Cigarettes release large quantities of smoke into the air (side stream smoke) that produce environmental pollutants including secondhand smoke (smoke in the air for several hours after smoking) and thirdhand smoke (smoke chemicals that impregnate fabric, wall boards, and dust of indoor environments), further contributing to risk of disease attributable to smoking.7,8

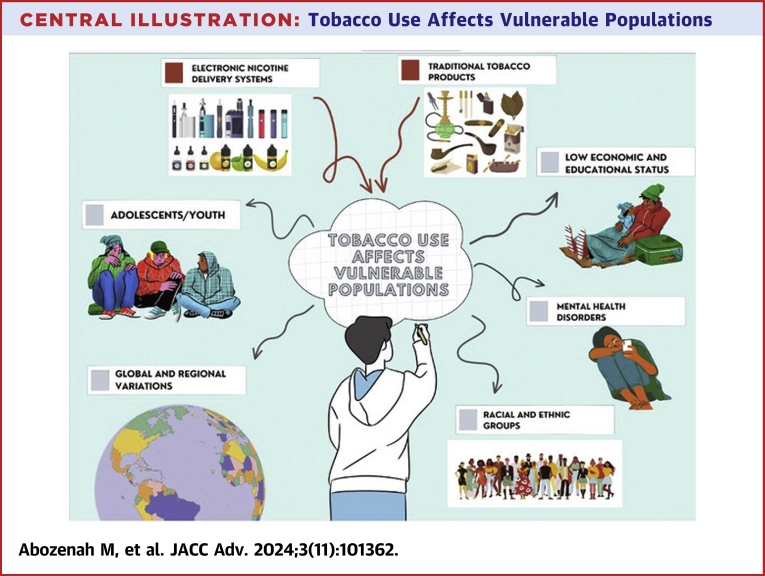

Cigarette smoking is responsible for most diseases caused by tobacco use; however, there is a diversity of products currently marketed. These can be separated into broad categories of tobacco leaf-containing products and nicotine-containing products.9 The tobacco leaf-containing category includes combusted tobacco products (cigarettes, cigars, waterpipe/hookah, bidis, and blunts), heated tobacco products, and noncombusted tobacco products (smokeless tobacco). The nicotine-containing products comprise ENDS and oral or nasal nicotine products (nicotine patches, lozenges, nasal spray, and oral pouches; Table 1). The various tobacco products available on the market are highlighted in Figure 1.

Table 1.

Electronic Nicotine Delivery Systems

| Type | Description | Size | Cost | Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disposable one-piece electronic cigarettes | Single-use device | Same size as a tobacco cigarette | Lowest cost | Varying levels of flavor, overall small vapor volume |

| Rechargeable cigalikes E-cigarettes | Rechargeable battery device; has a USB cable and a cartomizer | Larger than a tobacco cigarette | Lower cost | Offers increased vapor and flavor quality |

| Vape pods | Uses a small battery, ie, rechargeable | Slightly bigger than cigalikes | More expensive than disposable e-cigarettes | Power is typically much lower than pens or mods |

| Standard vape pen | 3-piece device; has a long battery life | Size varies between a pen and cigar | More expensive than disposable e-cigarettes but may be cost effective as e-liquid lasts longer | More flavor choices and increased vapor production |

| Box or vape mods | More potent vape. Rechargeable battery. | Different designs and sizes from a small box to a large cylinder | More expensive than e-cigarettes | High vape volume |

| Squonk mods | Burnt by a coil | Various sizes | Cost-effective | Large variety of flavors |

Figure 1.

Types of Noncombustible Tobacco Products

Image credit: http://cdc.gov/, reference to specific commercial products, manufacturers, companies, or trademarks does not constitute its endorsement or recommendation by the U.S. Government, Department of Health and Human Services, or Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Tobacco use demographics and impact on vulnerable populations

In 2020, approximately 1.2 billion people worldwide regularly smoked some form of tobacco, contributing to one in seven of all deaths that year.5 Nearly eight million deaths and 200 million disability-adjusted life-years are attributable to smoking annually worldwide.6 Despite declining smoking rates in the United States and worldwide, smoking remains the leading cause of preventable illness and death and is predicted to be responsible for over 450 million deaths globally between 2000 and 2050.7,8

Smoking is one of the most significant and preventable risk factors for cardiovascular disease and contributes to millions of years of life lost and billions of dollars in lost productivity.9,10 Quality of life is also adversely impacted by smoking, with poorer quality of life demonstrated in regular smokers.11 The economic impact of smoking12 also argues strongly for intensified efforts to educate people about its harmful effects and the importance of smoking cessation.13 Tobacco education and cessation programs are particularly crucial in an era when tobacco is impacting a younger and more vulnerable population than ever before.14 Clinicians interact with more than 70% of smokers annually, and the majority are willing to quit.15 Tobacco use prevalence, dependence, and abuse are higher among specific population such as adolescents and young adults, residents of low-income countries, mental health patients, and the LGBTQ+ community.16

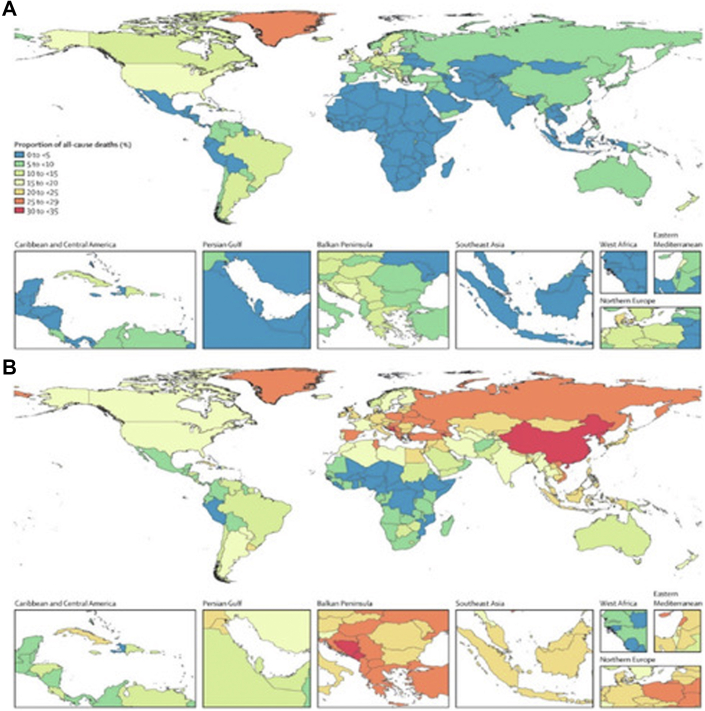

Fortunately, tobacco use has substantially declined over the past half century, in both men and women (Figure 2). Women overall have lower death rates attributable to tobacco use compared to men, with a less than 20% decline in absolute death rates attributable to tobacco in women by 2019.6 While this may be true in absolute terms, mortality related to tobacco use had a much sharper decline in the past few decades among men (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Proportion of All-Cause Deaths That Were Attributable to Smoking Tobacco Use Among Females and Males of All Ages in 2019

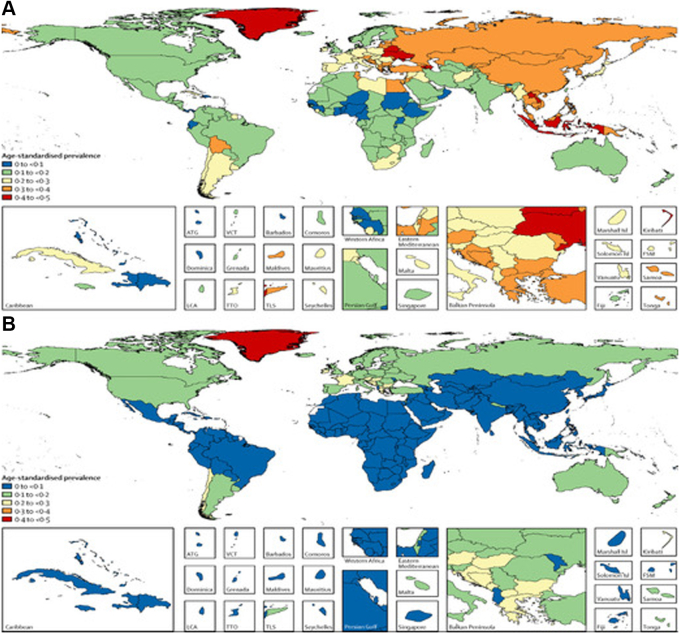

A 2015 Age-Standardized Prevalence of Current Smoking for Males and Females Aged 10 Years and Above From the “Global Burden of 87 Risk Factors in 204 Countries and Territories, 1990 to 2019: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet. 2020;396:1223-1249”.

Figure 3.

2015 Age-Standardized Prevalence of Current Smoking for Males and Females Aged 10 Years and Above

Proportion of All-Cause Deaths That Were Attributable to Smoking Tobacco Use Among (A) Females and (B) Males of All Ages in 2019 From “Global Burden of 87 Risk Factors in 204 Countries and Territories, 1990 to 2019: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet. 2020;396:1223-1249”.

The emergence of ENDS threatens to reverse the declining trend in nicotine dependence, particularly given the increased rates of use among nonsmokers and young adults.17,18 Current and former smokers comprise the majority of ENDS users, though there has been a concerning rise in their popularity among youth populations.18 Popularity among current and former smokers may be in part due to the perceived harm reduction of ENDS over traditional tobacco smoking.19 Lower costs, more readily accessible products, and improved social perception may be bigger incentives for youth and nonsmokers.19,20 This appeal may be strengthened in adolescent and young adult populations due to the wide availability of flavored options, adding to their popularity in this group.21,22 The perceived lower harm of ENDS may also play a major role in youths’ use of such devices.23

While ENDS may be a treatment option for cessation of combustible tobacco use, there is uncertainty regarding the long-term consequences of their use, as little long-term data exists.24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29

Region, race, and ethnicity

In 2015, the Global Burden of Diseases Collaborators reported the highest prevalence of tobacco use among men and women in Central and Western Europe, with Southeast Asia also having one of the highest smoking rates in men (Figure 3).30 The same group also found that, with the exception of some North African and sub-Saharan African nations, there has been a general decline in tobacco use in men between 1970 and 2020.5 Despite this general trend, disproportionate utilization persists among both men and women, accounting for tobacco smoking rates as high as more than 50% among men in China and the Indo-Pacific region, and as high as more than 40% among women in Greenland.6 In the United States, individuals living in rural areas are more likely to smoke tobacco than their counterparts in urban settings.31

Regarding deaths attributable to tobacco use, by 2019 it had decreased to below 20% in the majority of Southern and Western Asia, North and South America, Australia, and several North African and European countries.6 Despite this global trend, countries like Russia and China continue to have high death rates attributable to tobacco in their male population, at 20% to 25% and 30% to 35%, respectively (Figure 2).

Beyond geographical variations in tobacco smoking rates, race and ethnicity have a strong influence on smoking rates in the United States. Non-Hispanic American Indian/Alaskan Native adults have the highest tobacco smoking rates at 34.9%, followed by non-Hispanic White adults (21.1%), non-Hispanic Black adults (19.4%), Hispanic adults (11.7%), and non-Hispanic Asian adults (11.5%).31 Asian American, Pacific Islander, and Hispanic/Latino populations encompass diverse populations; however, a majority of this data is aggregated into these broad categories. As a group, Asian Americans have the lowest rates of tobacco use, but increased use has been observed for individuals of Southeast Asian descent.32 Racial discrimination has been linked to increased tobacco use in young Black men, Black and Latino adults, and adolescent African American girls.33,34 Furthermore, beyond influencing increased tobacco use, racial discrimination has also been shown to negatively impact success of tobacco cessation in racial minorities.33

Similar patterns of variation are seen when it comes to ENDS use. The incidence of trying these products is highest in non-Hispanic White adults (16.9%), followed by Hispanic (11.5%), non-Hispanic Asian (10.2%), and non-Hispanic Black (10%) adults. This trend persists when current use of ENDS products is evaluated; 3.7% of non-Hispanic White adults use ENDS products regularly, followed by Hispanic (2.5%), non-Hispanic Asian (2.2%), and non-Hispanic Black (1.6%) adults.35,36 Another product-related observation in tobacco smoking trends highlights a high prevalence of menthol cigarette use among non-Hispanic Black adult smokers, accounting for around 70% to 80% of all cigarettes smoked by this population. Menthol cigarettes are proven to be highly addictive due to chemosensory-driven condition cues and are potentially more harmful than nonmentholated cigarettes owing to the higher nicotine bioavailability caused by altered metabolism and alteration in nicotinic receptors, demonstrating a racially-based targeted promotion of certain tobacco products.37,38

Sex and gender

The tobacco industry, in an attempt to appeal to females, conducted extensive research into characteristics appealing to females in regard to cigarette and packaging design, as well as female-specific marketing strategies.39 Similar design features and marketing strategies have proven effective when it comes to ENDS.40

Male smoking behavior seems to be influenced more by their social environment, whereas women are more likely to smoke or continue smoking in an effort to lose weight or impact emotions.41 There is an underestimation of female smoking prevalence in certain countries, such as certain Asian countries, as women are more likely to conceal their smoking habits to avoid negative social perceptions.42

While the majority of male and female smokers report utilizing ENDS to aid with smoking cessation, gender differences arise in relation to types of devices used and perceived benefits. Positive reinforcement tends to contribute to maintenance of ENDS use in men, whereas women seem to respond more to negative reinforcement cues, such as stress reduction and weight control. Positive expectancies regarding the benefits of ENDS were more common in men.43 Despite these types of differences, smoking behavior seems to be influenced by similar psychosocial determinants in both men and women.44

It has been previously demonstrated that women tend to be less likely than men to respond to traditional tobacco cessation therapies.45 Some epidemiological data, however, suggest that women under 50 years of age may have higher rates of cessation than men.33 These findings represent gender-based health disparities, a notion that may support initiatives of gender-specific cessation strategies. Incorporating psychotherapy and weight loss counseling to focus on targeting the perceived benefits of mood regulation and weight control that strongly influence women’s desire to smoke31 are seemingly appropriate targets for such strategies. Ultimately, however, ongoing differences in tobacco cessation are likely multifactorial, and there currently is not enough strong evidence to support the notion that gender-specific strategies are superior to nongender-specific programs.46

Age and youth

Adolescents and young adults comprise a vulnerable group, especially prone to marketing tactics by tobacco companies. While the rates of teenagers trying combustible tobacco products have declined significantly since the 1990s, from 70% in 1990 to around 29% in 2017, ENDS use has significantly increased. Trends in ENDS use among high school students increased from 1.5% in 2011 to a staggering 27.5% by 2019 for any use, and from 20% in 2017 to 34.2% in 2019 for frequent use. A similar trend was noted in middle school students with a more than double increase in ENDS use from 5% in 2018 to 10.5% in 2019.47 In 2018, the U.S. Surgeon General declared vaping among teenagers as an epidemic.48,49

A major influencer on the popularity of ENDS among adolescents and young adults has been advertising by tobacco companies. Marketing strategies have transitioned from targeting smokers with claims that ENDS are effective smoking cessation interventions to steering teenagers and adolescents to try these products.50,51 This is evident in the wide range of flavorings available, packaging, and the heavy marketing presence on social media and other platforms frequented by adolescents and young adults.52,53 Several studies demonstrate a positive correlation between an adolescent’s ability to recall a specific advertisement, logo, or brand and smoking intent, level, and initiation.54,55

Another contributing factor is the delayed impact of policy and legislative change. Although the Child Nicotine Poisoning Prevention Act was passed in 2016, ENDS packaging was not required to include information on nicotine content56 until the end of 2018, which may have led some to believe that ENDS products are nicotine-free or to underestimate the high nicotine content found in some devices.22

There remains a paucity of data on cessation strategies targeted toward adolescents and young adults. Behavioral approaches and school-based curricula seem to have poor long-term efficacy when used in isolation but may be beneficial when combined with other cessation strategies.57 Similar efficacy patterns have been noted with pharmacologic cessation approaches.58 Data on cessation strategies in adolescents and young adults who use ENDS is lacking, though there is evidence to support that use of ENDS by adolescents and young adults increases the risk for subsequent cigarette smoking.59 With overall lower health care utilization rates by adolescents and young adults, it is crucial to screen for both traditional combustible tobacco products and ENDS use at every visit.60

Economic and educational status

Despite the overall decline in global tobacco use rates, certain groups are excluded from this positive trend. Today, more than 80% of the world’s tobacco smokers live in low- and middle-income countries.61 This may be in part due to earlier smoking cessation efforts in high-income countries, beginning in the late 1950s and early 1960s, leading to a decline in smoking prevalence, with middle-income countries only seeing a decline in smoking rates after 1990.62 While living in a high-income country may exert a protective effect, people living in poverty smoke more heavily and with higher frequency than their wealthier counterparts.63

In the United States, uninsured Americans are at least twice as likely to smoke tobacco products than those with private insurance, due in part to lack of access to health care, including preventive services.31,64 In addition, higher smoking-related medical comorbidities are seen in this population. While these associations are well established for traditional combustible tobacco products, more recent observational data reveals similar patterns for ENDS products, with the highest use rates witnessed in the lowest socioeconomic groups.36

Education level also associates with smoking tobacco product use. Adults with lower educational achievement are consistently found to have higher tobacco product use rates. This is especially true for adults who have not completed a high school education, while lower tobacco use rates have been observed for adults with higher education levels such as college.31 ENDS product use rate trends are similar in adults and also decline with higher levels of education.65 Use of ENDS products is associated with poor academic performance and behavioral choices, undermining the ability of individuals to achieve higher levels of education.60,66 Furthermore, cessation attempts and successful cessation also correlate with educational level, with more frequent attempts and higher success rates seen in adults with higher educational levels.67

Mental health

The strong association between mental health and tobacco smoking is well described.68 Individuals with mental health disorders are 2- to 3-fold more likely to be users of combustible tobacco products compared to the general population.69 It is difficult to understand if mental health disorders drive increased tobacco smoking rates or vice versa given the observational nature of the available scientific data.70 However, there is an abundance of evidence demonstrating higher rates of smoking for individuals with mental health disorders and increased rates of mental health disorders for individuals who smoke.71

This association has also been observed in ENDS product users who have higher rates of depression, other mental health disorders, and illicit substance use.72,73 There is evidence to suggest higher rates of ENDS use in individuals with underlying mental health issues,74 with the youth population being at an especially increased risk of mental health problems.75 While this association may be weaker than that seen with traditional cigarette smoking, it is still profound and supports the notion that ENDS are potentially harmful to mental health.76

Individuals with mental illness, even when severe, seem to respond to traditional smoking cessation techniques.77 Successful tobacco cessation has been demonstrated to improve mental health disorders and overall quality of life.78 It should be noted, however, that misconceptions regarding smoking cessation in this vulnerable population, such as lack of engagement in cessation or difficulty in cessation compliance are quite common, which may undermine the implementation and success of smoking cessation interventions.79

The LGBTQ+ community

Individuals identifying as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, or queer (LGBTQ+) are more likely than their heterosexual counterparts to use tobacco products,80 including both combustible and noncombustible/electronic tobacco products.81 This association is complex and varies greatly between sexes, by sexual and gender identity, and by tobacco product, further reinforcing the need for more research in this vulnerable population.82 Factors contributing to higher tobacco product use include reactions to disclosure of sexual orientation, sexual orientation discrimination, LGBT victimization, psychological distress, depression, and anxiety.83

LGBTQ+ individuals seem to have a predilection for menthol cigarettes, similar to that seen in African American smokers (as was previously highlighted).84 ENDS use is also highly prevalent, affecting 13% of LGBTQ+ adults, nearly double the prevalence of ENDS use in heterosexuals.85 This is similar to the age-adjusted prevalence of current combustible cigarette smokers and poses a serious challenge to curbing the progression of the ENDS epidemic.86 Influenced by the tobacco industry’s targeted marketing practices, more recently on social media platforms, tobacco-related health disparities affecting the LGBTQ+ community are on the rise.87

Despite this, individuals within the LGBTQ+ community have a similar desire to quit smoking when compared to non-LGBTQ+ people.84 Models tailored toward individuals belonging to this vulnerable population have shown promising results. “The Last Drag,” a LGBT-specific smoking cessation program incorporating group education and support interventions, showed comparable to better cessation rates as nontailored approaches, with 60% being smoke-free by the end of the intervention and 36% by 6 months.88 Additionally, a more supportive social environment has shown an association with reduced tobacco use and may also help with cessation in current smokers.89 Cessation interventions specifically targeting members of the LGBTQ+ community are currently lacking.90 This suggests an opportunity for interventions that can be highly effective and are worth further investment.

Opportunities to reduce tobacco use

The vulnerable populations outlined are disproportionally impacted by smoking, representing a serious gap in health care delivery but also an incredible opportunity for improving health equity. Tobacco cessation treatment and use prevention calls for a well-orchestrated effort by clinicians, health care systems, government agencies, and policymakers. Studies have revealed multiple missed opportunities by clinicians for tobacco abuse screening and tobacco use status assessment during clinic visits. In one study of adolescent Medicaid patients, almost half of all subjects (45%) did not have a documented smoking status; only half of all smokers were advised to quit, and even fewer were assisted (42%) or followed up (16%).91 Lower rates were noted in hospitalized patients, with only a third of survey responders in one study recalling smoking cessation counseling.92

While clinicians have a primary responsibility to evaluate and screen patients, health care systems can implement protocols to ensure that tobacco use assessment and interventions are standardized at each visit. Leveraging the electronic health record to create specific templates that include smoking status as a vital sign and measuring individual clinical performance on these metrics are potential ways to improve screening rates. Education and training of staff and clinicians is paramount, as low awareness of tobacco use screening remains a significant problem. Studies have shown that cessation treatments are higher at visits where EHRs delivered automated reminders supporting guideline-concordant interventions to clinicians.93 Additionally, insurance coverage of tobacco dependence treatment may increase the likelihood of tobacco cessation.15

Community-based interventions can also impact tobacco use. Adoption of tobacco control ordinances such as smoke-free restaurants and bans on self-service tobacco displays in some states has contributed to lower cardiovascular event rates. One meta-analysis found a 17% lower rate of acute myocardial infarction when smoking was banned in public and work places.35 Other opportunities include community smoking cessation events such as quit and win contests and media advocacy to raise public awareness, specifically targeting illegal sales to minors and reducing the number of tobacco outlets in local environments of vulnerable populations, such as in low-income neighborhoods.94

Public health measures may also mitigate the risk of tobacco use in vulnerable populations. Programs to reduce the nicotine content of tobacco products to lower risk of addiction have been proposed, along with reducing the availability of flavored tobacco products (such as menthol cigarettes, flavored cigars, and e-cigarettes), which are associated with higher dependence and disproportionate use by teenagers and young adults.95 Increased taxes on tobacco products is a proven tobacco control strategy with similar effects on ENDS consumption; however, ENDS taxation may have an unintended effect of combustible tobacco product substitution.96,97 The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) continues to maintain oversight of ENDS products and has issued warning letters to manufacturers and retailers who continue to illegally sell these products in the market, alongside a public education campaign to focus on prevention of youth e-cigarette use.

In response to the sharp increase in youth e-cigarette use, the FDA issued draft guidance in March 2019 to outline enforcement priorities they will consider with regard to ENDS products.98 In January 2020, the FDA finalized a ban on flavored e-cigarette products (other than tobacco and menthol).98 In April 2022, the FDA also proposed a ban on all menthol cigarettes and flavored cigars.99

Further consideration should also be given to gender-specific and culturally-specific cessation programs that may render such programs more accessible to certain vulnerable populations such as women, ethnic and racial minorities, and sexual minorities. Improved access to health care, widespread health insurance coverage, access to higher levels of education, and mental health screening and treatment are all likely to enhance efforts aimed at curbing the tobacco epidemic.

Conclusions and future directions

In 1957, Surgeon General Leroy E. Burney first highlighted the causal relationship between smoking and lung cancer. Seven years later, the 1964 Surgeon General report titled “Smoking and Health: Report of the Advisory Committee to the Surgeon General” was delivered, further highlighting the deleterious health implications of tobacco smoking. This forever changed public perception of tobacco products and paved the way for major policy changes targeting smoking cessation.62

Since then, smoking rates have declined in the United States and globally, through the efforts of clinicians, community agencies, and health care systems, as well as national and global health initiatives. ENDS use has dramatically risen in the past decade, and these products target vulnerable populations, specifically youth and adolescents, as well as individuals from low socioeconomic and educational backgrounds. The use of ENDS products to promote tobacco cessation and their associated cardiovascular risk remains uncertain due to lack of long-term studies.

Attempts to stem the use of all tobacco and nicotine-containing products will require consolidated efforts by clinicians, health care systems, local communities, and national and global policymakers (Figure 4). Tobacco and nicotine use assessment should be routinely performed at all health care visits, and resources should be available within health care systems and in the community to help combat the smoking epidemic. Efforts should be undertaken to identify people at highest risk for tobacco dependence—teenagers and young adults, low economic and educational status, mental health disorders, and the LGBTQ+ community.

Figure 4.

Opportunities to Reduce Tobacco Use

Community-based tactics can be highly effective when targeting areas with a high prevalence of these vulnerable populations.100,101 Wide implementation of community-based approaches are needed, focusing on access and availability of cessation resources, which can help facilitate smoking cessation efforts, though further research and innovation to optimize efforts remain. Health care systems and hospitals can play a vital role in successful implementation of tobacco and nicotine use reduction efforts. Access to health care becomes a pivotal component of all the health care system and physician-based interventions toward smoking cessation. With vulnerable populations having low health care access and/or utilization, this facet becomes more crucial. Universal health care coverage and higher resource allocation to underserved and lower income populations are likely to help bridge some of the gaps seen in health care access. Additionally, leveraging the electronic health record can be a highly valuable tool in cessation efforts to help acknowledge the issue and to promote action.

Advocacy at local and state levels in the United States to create more smoke-free public places and to legislate controls over density of tobacco outlets should be encouraged. Medical societies, including the American College of Cardiology, American Heart Association, and American Lung Society, played instrumental roles advocating for “Tobacco 21” legislation to increase the minimum smoking age to 21 years. These organizations must continue to work together to reduce minor exposure to ENDS products. At the national level, the Centers for Disease Control Tobacco Cessation Change Package is an example of a quality improvement tool for health care professionals to create workflows and provide resources to expand and increase effectiveness of tobacco cessation interventions.102 Additionally, new ENDS product applications and safety warnings by manufacturers must be vigilantly regulated and monitored by the FDA. Key challenges persist, specifically how to address health disparities of vulnerable populations. Poor access to care and limited resources for tobacco cessation treatment must be improved. Requiring commercial and government-sponsored insurers to cover the costs of tobacco cessation treatments and behavioral interventions should be promoted at the state, national, and global levels.

The World Heart Federation has published a policy brief outlining ways to reduce the potential risk associated with ENDS products.103 This document provides a framework that countries can adopt to stem the rising tide of ENDS use. Importantly, it recognizes that there is a critical need for more research on the harmful effects of ENDS and to determine if they are harm and smoking reduction tools or if they actually increase the risk of smoking initiation and relapse. While concerted efforts have dramatically lowered tobacco use rates globally, the new threat of ENDS products must be addressed with similar vigilance. Reversing the current trends of tobacco product use will require coordinated efforts of clinicians, hospitals and health care systems, local communities, medical societies, and government agencies.

Uncited Table

Funding support and author disclosures

Dr Pack was supported by a grant from the NHLBI #R01HL156851. Dr Yang has received grant support and significant from Amgen and Microsoft Research; has ownership interest and modest from Clocktree and Measure Labs; is a consultant and significant from Genentech; and has received honoraria and significant from the American College of Cardiology. Dr Brandt is a consultant in New Amsterdam. All other authors have reported that they have no relationships relevant to the contents of this paper to disclose.

Footnotes

The authors attest they are in compliance with human studies committees and animal welfare regulations of the authors’ institutions and Food and Drug Administration guidelines, including patient consent where appropriate. For more information, visit the Author Center.

References

- 1.CVDWHO. https://www.who.int/health-topics/cardiovascular-diseases

- 2.Arnett D.K., Blumenthal R.S., Albert M.A., et al. 2019 ACC/AHA guideline on the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task force on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation. 2019;140(11):e596–e646. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barua R.S., Rigotti N.A., Benowitz N.L., et al. 2018 ACC Expert Consensus decision pathway on tobacco cessation treatment. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72(25):3332–3365. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arrazola R.A., Kuiper N.M., Dube S.R. Patterns of current use of tobacco products among U.S. high school students for 2000-2012 - findings from the national youth tobacco survey. J Adolesc Health. 2014;54:54–60.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dai X., Gakidou E., Lopez A.D. Evolution of the global smoking epidemic over the past half century: strengthening the evidence base for policy action. Tob Control. 2022;31(2):129–137. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2021-056535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reitsma M.B., Kendrick P.J., Ababneh E., et al. Spatial, temporal, and demographic patterns in prevalence of smoking tobacco use and attributable disease burden in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet. 2021;397(10292):2337–2360. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01169-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Samet J.M. Tobacco smoking: the leading cause of preventable disease worldwide. Thorac Surg Clin. 2013;23(2):103–112. doi: 10.1016/j.thorsurg.2013.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jha P. Avoidable global cancer deaths and total deaths from smoking. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9(9):655–664. doi: 10.1038/nrc2703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (US) Office on Smoking and Health The health consequences of smoking—50 Years of progress: a report of the Surgeon general. Centers for disease control and prevention (US) 2014. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK179276/ [PubMed]

- 10.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Smoking-attributable mortality, years of potential life lost, and productivity losses--United States, 2000-2004. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2008;57(45):1226–1228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goldenberg M., Danovitch I., IsHak W.W. Quality of life and smoking. Am J Addict. 2014;23(6):540–562. doi: 10.1111/j.1521-0391.2014.12148.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xu X., Bishop E.E., Kennedy S.M., Simpson S.A., Pechacek T.F. Annual healthcare spending attributable to cigarette smoking: an update. Am J Prev Med. 2015;48(3):326–333. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jha P., Ramasundarahettige C., Landsman V., et al. 21st-century hazards of smoking and benefits of cessation in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(4):341–350. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1211128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Agaku I.T., Odani S., Okuyemi K.S., Armour B. Disparities in current cigarette smoking among US adults, 2002-2016. Tob Control. 2020;29(3):269–276. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2019-054948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clinical practice guideline treating tobacco use and dependence 2008 update panel L and staff. A clinical practice guideline for treating tobacco use and dependence: 2008 update. A U.S. Public health service report. Am J Prev Med. 2008;35(2):158–176. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Piesse A., Opsomer J., Dohrmann S., et al. Longitudinal uses of the population assessment of tobacco and health study. Tob Regul Sci. 2021;7(1):3–16. doi: 10.18001/trs.7.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McMillen R.C., Gottlieb M.A., Shaefer R.M.W., Winickoff J.P., Klein J.D. Trends in electronic cigarette use among U.S. Adults: use is increasing in both smokers and nonsmokers. Nicotine Tob Res. 2015;17(10):1195–1202. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntu213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cullen K.A., Gentzke A.S., Sawdey M.D., et al. E-cigarette use among youth in the United States, 2019. JAMA. 2019;322(21):2095–2103. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.18387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sapru S., Vardhan M., Li Q., Guo Y., Li X., Saxena D. E-cigarettes use in the United States: reasons for use, perceptions, and effects on health. BMC Publ Health. 2020;20(1):1518. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-09572-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.George J., Hussain M., Vadiveloo T., et al. Cardiovascular effects of switching from tobacco cigarettes to electronic cigarettes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;74(25):3112–3120. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.09.067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harrell M.B., Weaver S.R., Loukas A., et al. Flavored e-cigarette use: characterizing youth, young adult, and adult users. Prev Med Rep. 2017;5:33–40. doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2016.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fadus M.C., Smith T.T., Squeglia L.M. The rise of e-cigarettes, pod mod devices, and JUUL among youth: factors influencing use, health implications, and downstream effects. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019;201:85–93. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ambrose B.K., Rostron B.L., Johnson S.E., et al. Perceptions of the relative harm of cigarettes and e-cigarettes among U.S. youth. Am J Prev Med. 2014;47(2 Suppl 1):S53–S60. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fernández E., Ballbè M., Sureda X., Fu M., Saltó E., Martínez-Sánchez J.M. Particulate matter from electronic cigarettes and conventional cigarettes: a systematic review and observational study. Curr Environ Health Rep. 2015;2(4):423–429. doi: 10.1007/s40572-015-0072-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Du Y., Xu X., Chu M., Guo Y., Wang J. Air particulate matter and cardiovascular disease: the epidemiological, biomedical and clinical evidence. J Thorac Dis. 2016;8(1):E8–E19. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2015.11.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Martinelli N., Olivieri O., Girelli D. Air particulate matter and cardiovascular disease: a narrative review. Eur J Intern Med. 2013;24(4):295–302. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2013.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zirak M.R., Mehri S., Karimani A., Zeinali M., Hayes A.W., Karimi G. Mechanisms behind the atherothrombotic effects of acrolein, a review. Food Chem Toxicol. 2019;129:38–53. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2019.04.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Henning R.J., Johnson G.T., Coyle J.P., Harbison R.D. Acrolein can cause cardiovascular disease: a review. Cardiovasc Toxicol. 2017;17(3):227–236. doi: 10.1007/s12012-016-9396-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.DeJarnett N., Conklin D.J., Riggs D.W., et al. Acrolein exposure is associated with increased cardiovascular disease risk. J Am Heart Assoc. 2014;3(4) doi: 10.1161/JAHA.114.000934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reitsma M.B., Fullman N., Ng M., et al. Smoking prevalence and attributable disease burden in 195 countries and territories, 1990–2015: a systematic analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet. 2017;389(10082):1885–1906. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30819-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cornelius M.E., Loretan C.G., Wang T.W., Jamal A., Homa D.M. Tobacco product use among adults - United States, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71(11):397–405. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7111a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Caraballo R.S., Asman K. Epidemiology of menthol cigarette use in the United States. Tob Induc Dis. 2011;9(Suppl 1) doi: 10.1186/1617-9625-9-S1-S1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hicks M.R., Kogan S.M. The influence of racial discrimination on smoking among young black men: a prospective analysis. J Ethn Subst Abuse. 2020;19(2):311–326. doi: 10.1080/15332640.2018.1511493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brondolo E., Monge A., Agosta J., et al. Perceived ethnic discrimination and cigarette smoking: examining the moderating effects of race/ethnicity and gender in a sample of Black and Latino urban adults. J Behav Med. 2015;38(4):689–700. doi: 10.1007/s10865-015-9645-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Meyers D.G., Neuberger J.S., He J. Cardiovascular effect of bans on smoking in public places: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54(14):1249–1255. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Villarroel M.A. Electronic cigarette use among U.S. Adults, 2018. NCHS Data Brief. 2020:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wickham R.J. The biological impact of menthol on tobacco dependence. Nicotine Tob Res. 2020;22(10):1676–1684. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntz239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Products C for T Looking back, looking ahead: FDA’s progress on tobacco product regulation in 2022. FDA. 2023. https://www.fda.gov/tobacco-products/ctp-newsroom/looking-back-looking-ahead-fdas-progress-tobacco-product-regulation-2022

- 39.Carpenter C.M., Wayne G.F., Connolly G.N. Designing cigarettes for women: new findings from the tobacco industry documents. Addiction. 2005;100(6):837–851. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01072.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dawkins L., Turner J., Roberts A., Soar K. “Vaping” profiles and preferences: an online survey of electronic cigarette users. Addiction. 2013;108(6):1115–1125. doi: 10.1111/add.12150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Benowitz N.L., Hatsukami D. Gender differences in the pharmacology of nicotine addiction. Addict Biol. 1998;3(4):383–404. doi: 10.1080/13556219871930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chan W.H., Lai C.H., Huang S.J., et al. Verifying the accuracy of self-reported smoking behavior in female volunteer soldiers. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):3438. doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-29699-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Piñeiro B., Correa J.B., Simmons V.N., et al. Gender differences in use and expectancies of e-cigarettes: online survey results. Addict Behav. 2016;52:91–97. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2015.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Etter J.F., Prokhorov A.V., Perneger T.V. Gender differences in the psychological determinants of cigarette smoking. Addiction. 2002;97(6):733–743. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00135.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Smith P.H., Bessette A.J., Weinberger A.H., Sheffer C.E., McKee S.A. Sex/gender differences in smoking cessation: a review. Prev Med. 2016;92:135–140. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Torchalla I., Okoli C.T.C., Bottorff J.L., Qu A., Poole N., Greaves L. Smoking cessation programs targeted to women: a systematic review. Women Health. 2012;52(1):32–54. doi: 10.1080/03630242.2011.637611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gentzke A.S., Creamer M., Cullen K.A., et al. Vital signs: tobacco product use among middle and high school students - United States, 2011-2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68(6):157–164. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6806e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Farzal Z., Perry M.F., Yarbrough W.G., Kimple A.J. The adolescent vaping epidemic in the United States-how it happened and where we go from here. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2019;145(10):885–886. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2019.2410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Surgeon general’s advisory on E-cigarette use among youth | smoking & tobacco use | CDC. 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/basic_information/e-cigarettes/surgeon-general-advisory/index.html

- 50.Hartmann-Boyce J., McRobbie H., Butler A.R., et al. Electronic cigarettes for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021;(9) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010216.pub6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang R.J., Bhadriraju S., Glantz S.A. E-Cigarette use and adult cigarette smoking cessation: a meta-analysis. Am J Public Health. 2021;111(2):230–246. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2020.305999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kong G., Morean M.E., Cavallo D.A., Camenga D.R., Krishnan-Sarin S. Reasons for electronic cigarette experimentation and discontinuation among adolescents and young adults. Nicotine Tob Res. 2015;17(7):847–854. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntu257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jones K., Salzman G.A. The vaping epidemic in adolescents. Mo Med. 2020;117(1):56–58. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Goldstein A.O., Fischer P.M., Richards J.W., Jr., Creten D. Relationship between high school student smoking and recognition of cigarette advertisements. J Pediatr. 1987;110(3):488–491. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(87)80523-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pierce J.P., Gilpin E., Burns D.M., et al. Does tobacco advertising target young people to start smoking? Evidence from California. JAMA. 1991;266(22):3154–3158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Czaplicki L., Marynak K., Kelley D., Moran M.B., Trigger S., Kennedy R.D. Presence of nicotine warning statement on US electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS) advertisements 6 Months before and after the august 10, 2018 effective date. Nicotine Tob Res. 2022;24(11):1720–1726. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntac104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Backinger C.L., Fagan P., Matthews E., Grana R. Adolescent and young adult tobacco prevention and cessation: current status and future directions. Tob Control. 2003;12(Suppl 4):IV46–IV53. doi: 10.1136/tc.12.suppl_4.iv46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fanshawe T.R., Halliwell W., Lindson N., Aveyard P., Livingstone-Banks J., Hartmann-Boyce J. Tobacco cessation interventions for young people. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;11(11) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003289.pub6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Soneji S., Barrington-Trimis J.L., Wills T.A., et al. Association between initial use of e-cigarettes and subsequent cigarette smoking among adolescents and young adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171(8):788–797. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.1488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ghosh T.S., Tolliver R., Reidmohr A., Lynch M. Youth vaping and associated risk behaviors — a snapshot of Colorado. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(7):689–690. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1900830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.WHO EMRO. https://www.emro.who.int/tfi/mpower/index.html

- 62.The 1964 Report on Smoking and Health Reports of the Surgeon general - profiles in science. 2019. https://profiles.nlm.nih.gov/spotlight/nn/feature/smoking

- 63.Siahpush M., Singh G.K., Jones P.R., Timsina L.R. Racial/ethnic and socioeconomic variations in duration of smoking: results from 2003, 2006 and 2007 tobacco use supplement of the current population survey. J Public Health. 2010;32(2):210–218. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdp104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bailey S.R., Hoopes M.J., Marino M., et al. Effect of gaining insurance coverage on smoking cessation in community health Centers: a cohort study. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(10):1198–1205. doi: 10.1007/s11606-016-3781-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Choi K., Chen-Sankey J.C. Will Electronic Nicotine Delivery System (ENDS) use reduce smoking disparities? Prevalence of daily ENDS use among cigarette smokers. Prev Med Rep. 2019;17 doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2019.101020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Dearfield C.T., Chen-Sankey J.C., McNeel T.S., Bernat D.H., Choi K. E-cigarette initiation predicts subsequent academic performance among youth: results from the PATH Study. Prev Med. 2021;153 doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2021.106781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Babb S., Malarcher A., Schauer G., Asman K., Jamal A. Quitting smoking among adults - United States, 2000-2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;65(52):1457–1464. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6552a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pedersen W., von Soest T. Smoking, nicotine dependence and mental health among young adults: a 13-year population-based longitudinal study. Addiction. 2009;104(1):129–137. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02395.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Prochaska J.J., Das S., Young-Wolff K.C. Smoking, mental illness, and public health. Annu Rev Public Health. 2017;38:165–185. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031816-044618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Fluharty M., Taylor A.E., Grabski M., Munafò M.R. The association of cigarette smoking with depression and anxiety: a systematic review. Nicotine Tob Res. 2017;19(1):3–13. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntw140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lawrence D., Mitrou F., Zubrick S.R. Smoking and mental illness: results from population surveys in Australia and the United States. BMC Publ Health. 2009;9:285. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Obisesan O.H., Mirbolouk M., Osei A.D., et al. Association between e-cigarette use and depression in the behavioral risk factor surveillance system, 2016-2017. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(12) doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.16800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Grant J.E., Lust K., Fridberg D.J., King A.C., Chamberlain S.R. E-cigarette use (vaping) is associated with illicit drug use, mental health problems, and impulsivity in university students. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2019;31(1):27–35. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Riehm K.E., Young A.S., Feder K.A., et al. Mental health problems and initiation of E-cigarette and combustible cigarette use. Pediatrics. 2019;144(1) doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-2935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Becker T.D., Arnold M.K., Ro V., Martin L., Rice T.R. Systematic review of electronic cigarette use (vaping) and mental health comorbidity among adolescents and young adults. Nicotine Tob Res. 2021;23(3):415–425. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntaa171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Livingston J.A., Chen C.H., Kwon M., Park E. Physical and mental health outcomes associated with adolescent E-cigarette use. J Pediatr Nurs. 2022;64:1–17. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2022.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Banham L., Gilbody S. Smoking cessation in severe mental illness: what works? Addiction. 2010;105(7):1176–1189. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.02946.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Taylor G., McNeill A., Girling A., Farley A., Lindson-Hawley N., Aveyard P. Change in mental health after smoking cessation: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2014;348 doi: 10.1136/bmj.g1151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sheals K., Tombor I., McNeill A., Shahab L. A mixed-method systematic review and meta-analysis of mental health professionals’ attitudes toward smoking and smoking cessation among people with mental illnesses. Addiction. 2016;111(9):1536–1553. doi: 10.1111/add.13387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Stall R.D., Greenwood G.L., Acree M., Paul J., Coates T.J. Cigarette smoking among gay and bisexual men. Am J Public Health. 1999;89(12):1875–1878. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.12.1875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Delahanty J., Ganz O., Hoffman L., Guillory J., Crankshaw E., Farrelly M. Tobacco use among lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender young adults varies by sexual and gender identity. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019;201:161–170. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Hoffman L., Delahanty J., Johnson S.E., Zhao X. Sexual and gender minority cigarette smoking disparities: an analysis of 2016 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System data. Prev Med. 2018;113:109–115. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2018.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Blosnich J., Lee J.G.L., Horn K. A systematic review of the aetiology of tobacco disparities for sexual minorities. Tob Control. 2013;22(2):66–73. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Fallin A., Goodin A., Lee Y.O., Bennett K. Smoking characteristics among lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults. Prev Med. 2015;74:123–130. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.11.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Al Rifai M., Mirbolouk M., Jia X., et al. E-Cigarette use and risk behaviors among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender adults: the behavioral risk factor surveillance system (BRFSS) survey. Kans J Med. 2020;13:318–321. doi: 10.17161/kjm.vol13.13861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Mirbolouk M., Charkhchi P., Kianoush S., et al. Prevalence and distribution of E-cigarette use among U.S. Adults: behavioral risk factor surveillance system, 2016. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):429–438. doi: 10.7326/M17-3440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Emory K., Buchting F.O., Trinidad D.R., Vera L., Emery S.L. Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) view it differently than non-LGBT: exposure to tobacco-related couponing, E-cigarette advertisements, and anti-tobacco messages on social and traditional media. Nicotine Tob Res. 2019;21(4):513–522. doi: 10.1093/ntr/nty049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Eliason M.J., Dibble S.L., Gordon R., Soliz G.B. The last drag: an evaluation of an LGBT-specific smoking intervention. J Homosex. 2012;59(6):864–878. doi: 10.1080/00918369.2012.694770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Hatzenbuehler M.L., Wieringa N.F., Keyes K.M. Community-level determinants of tobacco use disparities in lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth: results from a population-based study. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2011;165(6):527–532. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Baskerville N.B., Dash D., Shuh A., et al. Tobacco use cessation interventions for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer youth and young adults: a scoping review. Preventive Medicine Reports. 2017;6:53–62. doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2017.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Sims T.H., Meurer J.R., Sims M., Layde P.M. Factors associated with physician interventions to address adolescent smoking. Health Serv Res. 2004;39(3):571–586. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2004.00245.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Raupach T., Merker J., Hasenfuss G., Andreas S., Pipe A. Knowledge gaps about smoking cessation in hospitalized patients and their doctors. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2011;18(2):334–341. doi: 10.1177/1741826710389370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Talbot J.A., Ziller E.C., Milkowski C.M. Use of electronic health records to manage tobacco screening and treatment in rural primary care. J Rural Health. 2022;38(3):482–492. doi: 10.1111/jrh.12613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kowitt S.D., Lipperman-Kreda S. How is exposure to tobacco outlets within activity spaces associated with daily tobacco use among youth? A mediation analysis. Nicotine Tob Res. 2020;22(6):958–966. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntz088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Odani S., Armour B., Agaku I.T. Flavored tobacco product use and its association with indicators of tobacco dependence among US adults, 2014-2015. Nicotine Tob Res. 2020;22(6):1004–1015. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntz092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Chaloupka F.J., Yurekli A., Fong G.T. Tobacco taxes as a tobacco control strategy. Tob Control. 2012;21(2):172–180. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Pesko M.F., Courtemanche C.J., Catherine Maclean J. The effects of traditional cigarette and e-cigarette tax rates on adult tobacco product use. J Risk Uncertain. 2020;60(3):229–258. doi: 10.1007/s11166-020-09330-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Commissioner O of the. FDA announces plans for proposed rule to reduce addictiveness of cigarettes and other combusted tobacco products. FDA. 2022. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-announces-plans-proposed-rule-reduce-addictiveness-cigarettes-and-other-combusted-tobacco

- 99.Commissioner O of the. FDA proposes rules prohibiting menthol cigarettes and flavored cigars to prevent youth initiation, Significantly reduce tobacco-related disease and death. FDA. 2022. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-proposes-rules-prohibiting-menthol-cigarettes-and-flavored-cigars-prevent-youth-initiation

- 100.Golechha M. Health promotion methods for smoking prevention and cessation: a comprehensive review of effectiveness and the way forward. Int J Prev Med. 2016;7:7. doi: 10.4103/2008-7802.173797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Secker-Walker R.H., Gnich W., Platt S., Lancaster T. Community interventions for reducing smoking among adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002;2002(3) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.CDC Tobacco cessation change package. Centers for disease control and prevention. 2021. https://millionhearts.hhs.gov/tools-protocols/action-guides/tobacco-change-package/index.html

- 103.WHF Tobacco. World Heart federation. https://world-heart-federation.org/what-we-do/tobacco/