Abstract

Purpose

Dietary fiber intake may influence the risk and severity of atopic dermatitis (AD), a common chronic allergic skin condition. This cross-sequential study investigated the association between dietary fiber intake and various characteristics of AD, including house dust mites (HDM) allergy and dry skin, in 13,561 young Chinese adults (mean years = 22.51, SD ± 5.90) from Singapore and Malaysia.

Methods

Dietary habits were assessed using a validated semi-quantitative, investigator-administered food frequency questionnaire from the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood. We derived an amount-based dietary index to estimate fiber intake while studying its correlation with probiotic drinks intake. AD status was determined by skin prick tests for HDM and symptomatic histories of eczema. Multivariable logistic regression analysis, adjusting for demographic, genetic predisposition, body mass index and lifestyle factors, and synergy factor analysis were used to explore the association and interaction of dietary factors on disease outcomes.

Results

High fiber intake (approximately 98.25 g/serving/week) significantly lowered the associated risks for HDM allergy (Adjusted Odds Ratio [AOR]: 0.895; 95% Confidence Intervals [CI]: 0.810–0.989; adjusted p-value < 0.05) and AD (AOR: 0.831; 95% CI: 0.717–0.963; adjusted p-value < 0.05), but not dry skin. While probiotic intake was not associated with AD, it was significantly correlated with fiber intake (R2 = 0.324, p-value < 0.0001). Among those frequently consuming probiotics, moderate fiber intake sufficiently lowered the AD risk (AOR: 0.717; 95% CI: 0.584–0.881; adjusted p-value < 0.01). Moreover, a fibre-rich diet independently mitigated risks associated with high intake of fats, saturated fats, and protein.

Conclusion

A high-fiber diet is associated with AD and HDM allergy. Moderate-to-high fiber intake, particularly in conjunction with probiotics, may further mitigate AD risks.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00394-024-03524-6.

Keywords: Atopic dermatitis, Allergy sensitization, Dietary fibers, Ethnic Chinese, Epidemiology

Introduction

The rising prevalence of atopic dermatitis (AD) in recent decades has become a pressing global health concern, imposing significant societal and economic burdens across diverse populations [1]. There is a growing recognition of the potential influence of dietary habits on inflammatory conditions. This shift reflects a broader acknowledgement of the complex interplay between diet, immune function, and inflammation, prompting individuals to explore dietary interventions as a means to manage and potentially prevent allergic conditions like AD [2, 3]. While various macronutrients and micronutrients contribute to overall health, dietary fiber emerges as a particularly compelling focus due to its unique ability to modulate the composition and functionality of the gut microbiota. This modulation may mitigate the inflammatory cascade implicated in AD pathogenesis, making dietary fiber a promising dietary intervention for managing and potentially preventing AD.

Dietary fibers are a diverse group of carbohydrates found in plant-based foods like fruits, vegetables, whole grains, legumes, and nuts [4]. Unlike other carbohydrates, dietary fibers resist digestion and undergo fermentation by gut bacteria. This unique process is associated with numerous health benefits, including improved digestive and immune health, inflammation regulation, and promote a diverse and balanced gut microbiota [5]. While several cross-sectional investigations and animal research have suggested the potential benefits of increasing dietary fiber intake in managing AD and allergic diseases [6–8], significant gaps persist in understanding its precise effects on AD symptoms. Despite numerous reported associations in children, exploration of the association between dietary fiber intake and AD in adults is limited. Moreover, studies examining how dietary fiber intake influences various characteristics of AD, particularly allergic sensitization and dry skin, are lacking. By focusing on dietary fiber intake and its association with AD, we aim to elucidate a specific aspect of the complex relationship between diet and AD, thereby addressing the gaps in current research and advancing our understanding of potential dietary interventions to improve patient outcomes.

Therefore, the main objective of this cross-sectional study involving a large clinically and epidemiologically well-defined allergic cohort of young Chinese adults from Singapore and Malaysia is to comprehensively investigate the association between intake of dietary fiber, probiotics and various aspects of AD, aiming to fill the existing gaps in knowledge and provide insights into potential dietary interventions for managing AD.

Methods

Study population and design

In this cross-sequential study, volunteers were primarily composed of university students from the National University of Singapore, Universiti Tunku Abdul Rahman, and Sunway University, between 2005 and 2022. Recruitment of participants was performed in a rigorous process of random, unbiased, and consecutive sampling via ongoing volunteer recruitment drives. The study adhered to the Helsinki Declaration and Good Clinical Practices. Participants had to be over 18 years old, with parental consent mandatory for those under 21 years old. All participants provided informed consent. Otherwise, there were no specific inclusion or exclusion criteria. We recruited participants from a university setting, aiming to capture a diverse sample within the young adult population. While we recognize that this may not represent the entire general population, university settings provide a broad recruitment base, including individuals from various geographical, socio-economic, and cultural backgrounds. This approach ensures a sufficiently large sample size for reliable statistical analysis and focuses on the young adult demographic relevant to our study objectives.

Initially, 18,528 subjects were recruited to form the Singapore/Malaysia Cross-sectional Genetics Epidemiology Study (SMCGES) cohort. After excluding 2427 subjects due to missing or invalid data for dietary habits, age, and sex, the final analysis focused on 13,561 young Chinese adults (mean years = 22.51, SD ± 5.90). The exclusion of invalid data ensures the reliability, statistical power, and data integrity of the analysis, minimizing biases and inaccuracies in the research findings. The study focused on the Chinese ethnic group, reflecting Singapore’s largest ethnic group at 75.2% [9], to ensure broad representation and minimize unnecessary ascertainment bias in the findings. A validated questionnaire based on the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) was investigator-administered to collect lifestyle, dietary, personal and family symptomatic histories of AD, demographic, and anthropometric information [10].

Defining allergic sensitization, AD, and dry skin

Subjects underwent a skin prick test (SPT), a standard method for assessing immediate allergic reactions, to detect allergic sensitization to common house dust mite (HDM) allergens (Blomia tropicalis and Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus) in the tropical environment. Previous allergic studies established strong associations between HDM allergy and allergic diseases, making HDM allergy a reliable indicator for allergen-specific immunoglobulin-E responses [11, 12]. To ensure test reliability, SPT was not performed on subjects who had taken antihistamines or related drugs for at least three days before the test. The SPT involved the use of positive (histamine) and negative (saline) controls to validate the responses. A positive SPT response indicated a wheal diameter ≥ 3mm in response to either HDM allergens compared to negative saline control. A negative SPT response showed no wheal diameter ≥ 3mm for both HDM allergens. The majority (65.1%) showed a positive SPT response to HDM allergens, compared to those with a negative SPT response (34.1%).

For this study, we utilized validated guidelines from the UK Working Party’s diagnostic criteria [13] and Hanifin and Rajka criteria [14] to define a personal symptomatic history of AD. Subjects were specifically assessed for the presence of an itchy rash intermittently for at least six months, affecting flexural areas such as the folds of the elbows, behind the knees, and including areas like the ankles, buttocks, neck, cheeks, ears or eyes. Itchy rashes distributed in flexural areas are major diagnostic indicators with high sensitivity and specificity for AD [13–15]. Trained personnel concurrently assessed the presence of an itchy flexural rash during data collection. These assessments were periodically cross-validated by a dermatologist and found to be consistent. We defined individuals with AD by combining two key criteria: personal symptomatic history and SPT reactivity to HDMs. AD cases were specifically identified based on the presence of an itchy flexural rash and a positive SPT response to HDMs. Individuals who neither displayed an itchy flexural rash nor had a positive SPT response to HDMs were classified as non-allergic non-eczema. There were 2316 individuals with AD (17.1%) and 3650 non-allergic non-eczema individuals (26.9%). Comparing AD cases with non-allergic non-eczema individuals helps identify potential risk factors and associations within the population.

Individuals with dry skin were identified through a rigorous process. Subjects were directly assessed by trained research personnel for dry skin according to predetermined criteria. Additionally, a subset of subjects underwent skin physiological measurement using a Corneometer, a device commonly employed to assess skin hydration and water retention capacity [16]. The subjective assessment demonstrated a high level of concordance with the objective measurements, thus ensuring accurate identification of individuals with dry skin (n = 2110; 15.5%) and those without dry skin (n = 2492; 18.4%).

Dietary intake frequency and amount-based dietary index

In our study, we analysed the overall dietary fiber intake, which includes both soluble and insoluble fibers. To estimate total dietary fiber intake, we referred to the 16 food types listed in our validated semi-quantitative food frequency questionnaire (FFQ) adapted from the ISAAC Phase III study [17, 18]. The subjects were asked, “In the past 12 months, how often, on average, did you eat or drink the following: Meat (e.g. Beef, lamb, chicken, pork); Seafood (including fish); Fruits; Vegetables (green and root); Pulses (peas, beans, lentils); Cereals (including bread); Rice; Butter; Margarine; Nuts; Potatoes; Milk; Eggs; Burgers/fast food; Yakult®/Vitagen®/similar yoghurt drinks (collectively known as probiotic drinks)?” Response options included “never or only occasionally”, “once or twice per week”, and “most or all days” for each food type. These 16 food types represent a diverse range of food items commonly consumed by various populations and are known to contribute to overall nutrient intake and health outcomes.

To assess the association between dietary fiber intake and various outcomes, we developed an amount-based dietary index, Dietary Fiber Amount Index (DFAI). The DFAI was constructed by assigning intake frequency scores to 16 different food types (Fig S1). Following the criteria established by Manousos et al. [19], frequency scores were allocated as follows: + 7 for most or all days, + 2 for once or twice per week, or 0 for never or occasionally consumption. These scores were then multiplied by the average total fiber amount of each food type, sourced from the comprehensive United States Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) nutritional database (Table S1).

Subjects were stratified based on their estimated total fiber intake, with cut-offs chosen at the 33rd and 66th percentiles of the preliminary distribution of the SMCGES population. These cut-offs were determined after examining the preliminary distribution of fiber intake in the SMCGES population to ensure that each group represented meaningful levels of intake for analysis. Subjects below the 33rd percentile were categorized as having a low estimated total fiber intake while those above the 66th percentile were categorized as having a high estimated total fiber intake. Details on the cut-offs and statistics of the DFAI are provided in Fig S2.

Statistical analysis

Data entries were documented using Microsoft Excel (http://office.microsoft.com/en-us/excel/), while statistical analyses were evaluated using R program version 2021.09.0.351 (RStudio Team, 2021). Logistic regression was employed to model the association between dietary fiber intake and various outcomes. Control for potential confounding factors, including age, sex, body mass index (BMI) using Asian-specific categories, parental eczema, parental education (proxy for socioeconomic status), and engagement in physical activity, was implemented in the multivariable logistic regression analyses. These factors were controlled as they were previously significantly associated with AD and allergy risks [20–24]. Controlling for these factors allowed us to isolate the specific effects of dietary fiber on allergic outcomes and ensured a more accurate assessment of the true association between dietary fiber intake and various outcomes. Results were presented as adjusted odds ratios (AORs) with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Statistical significance was determined by p-value < 0.05, with AORs having 95% CI not including 1.000. P-values were adjusted using the False Discovery Rate (FDR) to minimize the risk of type I errors when making multiple statistical tests in the association analyses. Synergy factor (SF) assesses the potential interactions between risk factors in case–control studies, particularly useful for complex diseases like AD [25]. SF examines whether combined effects of dietary fiber intake and other nutrient factors exhibit synergy (greater than additive) or antagonism (lesser than additive) in influencing AD susceptibility.

Results

Baseline characteristics of study population

The study population comprised more females (59.4%) than males (40.6%). The majority (54.9%) was within the healthy BMI range of 18.0–23.0 kg/m2. A higher proportion of AD individuals were overweight and having parental eczema compared to non-allergic non-eczema individuals. Overweight individuals were also significantly more common among those with SPT-positive compared to those SPT-negative individuals. Additionally, individuals with dry skin have a higher prevalence of parental eczema than those without dry skin. The distribution of parental education levels varied significantly between different allergic outcomes. Most subjects participated in physical activities once or twice per week (52.7%), and there was a significant difference in the engagement of physical activities across individuals with allergic outcomes. Table 1 provides an overview of the subject demographics across different outcomes.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of 13,561 young Chinese adults in the Singapore/Malaysia Cross-sectional Genetics Epidemiology Study (SMCGES) cohort across various outcomes

| Characteristics | Total (n = 13,561) |

Atopic Dermatitis (AD) | House Dust Mite (HDM) Allergy1 | Dry Skin | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-atopic non-eczema individuals (n = 3650) |

AD cases (n = 2316) |

p-value | Individuals with a negative SPT response (n = 4622) |

Individuals with a positive SPT response (n = 8840) |

p-value | Individuals without dry skin (n = 2492) |

Individuals with dry skin (n = 2110) |

p-value | ||||

| Sex (n, %) | ||||||||||||

| • Male | 5501 (40.6%) | 1068 (29.3%) | 963 (41.6%) | < 0.0001* | 1308 (28.3%) | 4161 (47.1%) | < 0.0001* | 961 (38.6%) | 670 (31.8%) | < 0.0001* | ||

| • Female | 8060 (59.4%) | 2582 (70.7%) | 1353 (58.4%) | 3314 (71.7%) | 4679 (52.9%) | 1531 (61.4%) | 1440 (68.2%) | |||||

| Body Mass Index, Asian Class (n, %) | ||||||||||||

| • Healthy (18.0–23.0 kg/m2) | 7445 (54.9%) | 2060 (56.4%) | 1207 (52.1%) | < 0.01* | 2590 (56.0%) | 4806 (54.4%) | < 0.01* | 1343 (53.9%) | 1078 (51.1%) | 0.156 (ns) | ||

| • Underweight (< 18.0 kg/m2) | 2327 (17.2%) | 697 (19.1%) | 391 (16.9%) | 863 (18.7%) | 1396 (15.8%) | 343 (13.8%) | 321 (15.2%) | |||||

| • Overweight (> 23.0 kg/m2) | 2092 (15.4%) | 519 (14.2%) | 411 (17.7%) | 687 (14.9%) | 1442 (16.3%) | 535 (21.5%) | 418 (19.8%) | |||||

| NA |

1697 (12.5%) |

374 (10.2%) | 307 (13.3%) | - |

482 (10.4%) |

1196 (13.5%) |

- | 271 (10.9%) | 293 (13.9%) | - | ||

| Parental eczemab (n, %) | ||||||||||||

| • None | 11831 (87.2%) | 3320 (91.0%) | 1774 (76.6%) | < 0.0001* | 4071 (88.1%) | 7680 (86.9%) | 0.065 (ns) | 2138 (85.8%) | 1636 (77.5%) | < 0.0001* | ||

| • Either | 1423 (10.5%) | 264 (7.2%) | 466 (20.1%) |

455 (9.8%) |

955 (10.8%) | 289 (11.6%) | 393 (18.6%) | |||||

| • Both | 121 (0.9%) | 18 (0.5%) |

50 (2.2%) |

33 (0.7%) |

86 (1.0%) |

22 (0.9%) |

42 (2.0%) |

|||||

| NA |

186 (1.4%) |

48 (1.3%) |

26 (1.1%) |

- |

63 (1.4%) |

119 (1.3%) |

- |

43 (1.7%) |

39 (1.8%) |

- | ||

| Parental educationc (n, %) | ||||||||||||

| • Lower | 6237 (46.0%) | 1592 (43.6%) | 1027 (44.3%) | < 0.0001* | 1978 (42.8%) | 4212 (47.6%) | < 0.0001* | 971 (39.0%) | 832 (39.4%) | 0.586 (ns) | ||

| • Middle | 3088 (22.8%) | 772 (21.2%) | 580 (25.0%) | 980 (21.2%) | 2087 (23.6%) | 564 (22.6%) | 509 (24.1%) | |||||

| • High | 3622 (26.7%) | 1110 (30.4%) | 628 (27.1%) | 1436 (31.1%) | 2161 (24.4%) | 828 (33.2%) | 688 (32.6%) | |||||

| NA |

614 (4.5%) |

176 (4.8%) |

81 (3.5%) |

- |

228 (4.9%) |

380 (4.3%) |

- |

129 (5.2%) |

81 (3.8%) |

- | ||

| Engagement in physical activities (n, %) | ||||||||||||

| • Never or only occasionally | 4655 (34.3%) | 1418 (38.8%) | 765 (33.0%) | < 0.0001* | 1819 (39.4%) | 2796 (31.6%) | < 0.0001* | 900 (36.1%) | 782 (37.1%) | 0.810 (ns) | ||

| • Once or twice per week | 7144 (52.7%) | 1841 (50.4%) | 1223 (52.8%) | 2310 (50.0%) | 4792 (54.2%) | 1240 (49.8%) | 1034 (49.0%) | |||||

| • Most or all days | 1657 (12.2%) | 365 (10.0%) | 311 (13.4%) | 458 (9.90%) | 1190 (13.5%) | 324 (13.0%) | 278 (13.2%) | |||||

| NA |

105 (0.7%) |

26 (0.7%) |

17 (0.7%) |

- |

35 (0.8%) |

62 (0.7%) |

- |

28 (1.1%) |

16 (0.8%) |

- | ||

AD Atopic dermatitis, HDM House dust mite, SPT Skin prick test

aHDM allergy is determined by a positive skin prick test when a wheal diameter ≥ 3mm appeared with a negative saline reaction to either Blomia tropicalis and Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus

bParental history of AD is defined by the presence of either paternal and/or maternal symptomatic history of eczema from the immediate family

cMiddle refers to having at least one parent who has an educational background equivalent to a tertiary education. A tertiary equivalence education refers to obtaining a diploma, degree, or higher academic qualification

*P-value was adjusted by False Discovery Rate (FDR) for multiple comparisons. Adjusted p-value < 0.05 is statistically significant, bolded, and marked with an asterisk

Dietary fiber intake, probiotic drinks intake and AD

The mean dietary fiber intake was approximately 89.11 g/serving/week (SD ± 39.58), ranging from 69.76 g/serving/week for low intake to 98.25 g/serving/week for high intake (Fig S2). The estimated average dietary fiber intake (12.73 g/serving/day) falls below the recommended daily dietary fiber intake (23.0 g/serving/day) for a typical healthy individual in Singapore.

Individuals with high dietary fiber intake showed a lower associated risk for HDM allergy (Adjusted Odds Ratio [AOR]: 0.895; 95% Confidence Intervals [CI]: 0.810–0.989; adjusted p-value < 0.05) and AD (AOR: 0.831; 95% CI: 0.717–0.963; adjusted p-value < 0.05). Dietary fiber intake was not associated with dry skin (AOR: 1.054; 95% CI: 0.898–1.237; adjusted p-value: 0.520), indicating that dietary fiber may not influence the xerosis associated with AD in our study (Table 2).

Table 2.

Association between dietary fiber intake and various outcomes among 13,561 young Chinese adults from the Singapore/Malaysia Cross-sectional Genetics Epidemiology Study (SMCGES)

| Dietary fiber intakeb | Atopic dermatitis (AD) (3650 non-atopic non-eczema individuals vs. 2316 AD cases) | House dust mite allergy (4622 individuals with a negative skin prick test response vs. 8840 individuals with a positive skin prick test response) | Dry skin (2492 individuals without dry skin vs. 2110 individuals with dry skin) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AORa | 95% CI | p-value | AORa | 95% CI | p-value | AORa | 95% CI | p-value | |

| Overall cohort (n = 13,561) | |||||||||

| Low (≤ 69.8) | 1.000 | REF | – | 1.000 | REF | – | 1.000 | REF | – |

| Moderate (between 69.8 and 98.3) | 0.872 | 0.753–1.009 | 0.066 (ns) | 0.986 | 0.892–1.089 | 0.777 (ns) | 0.919 | 0.784–1.078 | 0.301 (ns) |

| High (≥ 98.3) | 0.831 | 0.717–0.963 | < 0.05* | 0.895 | 0.810–0.989 | < 0.05* | 1.054 | 0.898–1.237 | 0.520 (ns) |

| Less frequent (never or only occasionally) intake of probiotic drinks (n = 5685) | |||||||||

| Low (≤ 69.8) | 1.000 | REF | – | 1.000 | REF | – | 1.000 | REF | – |

| Moderate (between 69.8 and 98.3) | 1.071 | 0.864–1.328 | 0.531 (ns) | 1.129 | 0.975–1.308 | 0.106 (ns) | 0.902 | 0.708–1.150 | 0.407 (ns) |

| High (≥ 98.3) | 0.955 | 0.750–1.214 | 0.706 (ns) | 0.962 | 0.818–1.133 | 0.643 (ns) | 0.882 | 0.669–1.161 | 0.372 (ns) |

| Frequent (once or twice per week/most or all days) intake of probiotic drinks (n = 7776) | |||||||||

| Low (≤ 69.8) | 1.000 | REF | – | 1.000 | REF | – | 1.000 | REF | – |

| Moderate (between 69.8 and 98.3) | 0.717 | 0.584–0.881 | < 0.01* | 0.894 | 0.776–1.029 | 0.119 (ns) | 0.932 | 0.749–1.159 | 0.524 (ns) |

| High (≥ 98.3) | 0.720 | 0.590–0.879 | < 0.01* | 0.865 | 0.754–0.991 | < 0.05* | 1.128 | 0.914–1.394 | 0.263 (ns) |

aResults from multivariable logistic regression are presented as adjusted odds ratio (AOR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI). Confounding variables (age, sex, parental eczema, parental education, and engagement in physical activities) were controlled. b Dietary fiber intake was expressed in terms of g/serving/week

*P-value was adjusted by False Discovery Rate (FDR) for multiple comparisons. Adjusted p-value < 0.05 is statistically significant, bolded, and marked with an asterisk

While a higher dietary fiber intake was associated with lower inflammation, it alone may not sufficiently modulate immune responses and inflammation [26]. Probiotic supplementation may offer complementary benefits in modulating immune responses by promoting a balanced gut microbiota [27]. Therefore, concurrent analysis of probiotic intake within our cohort is also imperative for a comprehensive assessment of the association between dietary fiber intake and various outcomes. The intake frequency of probiotic drinks showed a statistically significant positive correlation with dietary fiber intake (R2 = 0.324, p-value < 0.0001), indicating a potential relationship between these two diet components (Fig S3). There was a significant variation in the frequency of probiotic drinks intake among individuals with HDM allergy and dry skin (Table S2). Interestingly, individuals with once or twice-per-week intake were significantly associated with a lowered risk of allergic sensitization (AOR: 0.860; 95% CI: 0.788–0.939; adjusted p-value < 0.001) but not those with frequent intake of most or all days (AOR: 0.887; 95% CI: 0.786–1.001; adjusted p-value = 0.052).

Subsequently, the population was stratified by probiotic drinks intake to examine how different levels of probiotic consumption affect the relationship between dietary fiber intake and allergic outcomes. Among subjects with frequent intake of probiotic drinks (n = 7776. 57.3%), high dietary fiber intake remained significantly associated with a lowered risk of both HDM allergy (AOR: 0.865; 95% CI: 0.754–0.991; adjusted p-value < 0.05) and AD (AOR: 0.720; 95% CI: 0.590–0.879; adjusted p-value < 0.01). However, no association was observed in subjects with never or only occasional probiotic drinks intake (n = 5685, 41.9%) (Table 2). Moreover, SF analysis showed that the interaction between dietary fiber intake and probiotic drink intake was independent and not antagonistic in modulating the associated risks for HDM allergy and AD (Table S3).

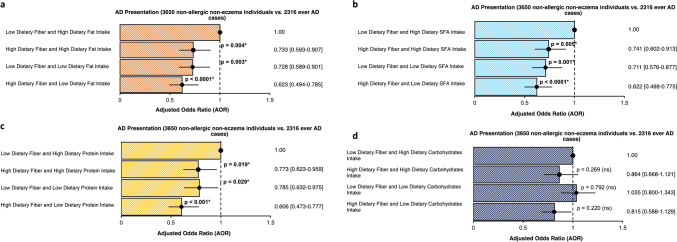

Interactions between dietary fiber intake and nutrients intake

Furthermore, we conducted a separate interaction analysis to assess whether the association between dietary fiber and allergic outcomes remained independent of other dietary factors. We examined the dietary intake of fiber alongside various nutrients previously investigated in our cohort, including dietary intake of total fat, proteins, carbohydrates, and saturated fatty acids (SFA) [28–30]. This provides a comprehensive understanding of how overall dietary composition influences outcomes and better reflects real-world dietary patterns for clinically relevant insights into complex diseases like AD. Even among individuals with high dietary fat, SFA, or protein intake, high dietary fiber intake was sufficient to lower the associated risks for AD. The association between AD and dietary fiber intake was lost upon adjusting for carbohydrate intake (Fig. 1). Interactions between dietary fiber intake and various nutrients intake were independent and additive in influencing AD susceptibility (Table S3).

Fig. 1.

Odds ratio plot showing the interaction between dietary fiber intake and a dietary fat intake, b dietary saturated fatty acids (SFA) intake, c dietary protein intake, and d) dietary carbohydrates intake among 13,561 young Chinese adults from the Singapore/Malaysia Cross-sectional Genetics Epidemiology Study (SMCGES) cohort. Results are presented in adjusted odds ratio (AOR), 95% confidence intervals (CI), and p-value. * P-value was adjusted by False Discovery Rate (FDR) for multiple comparisons. Adjusted p-value < 0.05 is statistically significant, bolded, and marked with an asterisk. Multivariable analysis was adjusted for age, sex, body mass index, parental eczema, parental education, and engagement of physical activities. A reference dotted line is drawn at the interception point where AOR equals 1.000 and the 95% CI is represented by a single line that cuts the AOR

Discussion

In our study, young adult individuals with high dietary fiber intake showed significantly lower odds of allergic outcomes, including HDM allergy and AD. Low dietary fiber intake may promote mucus-degrading bacteria, increasing allergen access [31], while high-fiber diets support skin barrier function, effectively limiting allergen ingress and reducing sensitization risk [32]. High dietary fiber intake is associated with the stabilization of gut microbial community diversity [33] and decreases leptin levels, thus mitigating low-grade chronic inflammation [34]. Clinical trials demonstrated that increased consumption of whole grain foods, rich sources of dietary fiber, can effectively reduce inflammatory markers such as C-reactive protein, interleukin-6, and tumour-necrosis factor [35, 36]. While our study provides valuable insights into the relationship between dietary fiber intake and allergic outcomes among young adults, it is important to acknowledge a limitation regarding childhood atopy data. We focused on current AD symptoms within the past 12 months, but the lack of detailed data on childhood atopic conditions limits our ability to differentiate between childhood atopy continuation and new-onset AD in adulthood accurately. Future research efforts, including collaborations with established birth cohort studies like Growing Up in Singapore Towards Healthy Outcomes (GUSTO) [37] and Singapore PREconception Study of long-Term maternal and child Outcomes (S-PRESTO) [38], will enable us to explore the longitudinal trajectory of allergic conditions from childhood into adulthood. This will provide deeper insights into how early-life atopic conditions influence the prevalence and manifestation of AD, particularly in relation to dietary fiber intake.

While current evidence on symbiotic supplementation for preventing and treating AD remains inconclusive [3, 39], the World Allergy Organization recommends the use of probiotics during pregnancy and breastfeeding [40]. A meta-analysis highlighted the potential efficacy of symbiotics in treating AD in children, but strong evidence supporting their preventive use is limited. Despite the heterogeneity between studies, the meta-analysis underscored potential benefits of dietary interventions involving symbiotic [41]. In our study, frequent consumption of probiotic drinks correlated with dietary fiber intake, yet the relationship between probiotics and AD was less clear. Our findings primarily highlights the impact of overall dietary fiber intake on allergic outcomes, with probiotic intake being an additional, but not definitive, factor. This nuanced understanding underscores the importance of dietary fiber in managing allergic conditions, while suggesting that further research is needed to clarify the role of probiotics.

The USDA database was selected for its extensive coverage and detailed nutritional information, which is essential for accurate dietary fiber estimation. Although we acknowledge that it may not perfectly match the exact varieties of food in the Asian region, we took several steps to address this concern. Given that the Singapore Health Promotion Board database lacks detailed fiber information for several food groups, we used the USDA database to fill these gaps. To enhance cultural relevance and applicability, we cross-referenced the USDA database entries with common food items consumed by our study population. This process involved selecting food items from the USDA database that closely resembled those typically consumed in Singapore and Malaysia, ensuring the accuracy and relevance of our dietary assessments. However, the USDA database used in our study provided information mainly on total dietary fiber but may not consistently have data to distinguish between soluble and insoluble fibers. Recognizing the importance of this distinction, we plan to enhance future research by incorporating advanced dietary assessment tools and relevant biomarkers. Specifically, we will focus on short-chain fatty acids including acetate, propionate, and butyrate, which are key indicators of fiber fermentation and its effects on gut microbiota and immune responses for future longitudinal studies [27, 42].

When considering dietary interventions for managing AD, it is essential to recognize the potential complications related to individual tolerance, dietary restrictions, and nutritional needs. Individuals with AD, especially those with underlying gastrointestinal issues or sensitivities, may experience discomfort like bloating or diarrhoea with high dietary fiber consumption, making consistent adherence challenging [43, 44]. Moreover, common food allergens like fruits, vegetables, and legumes, which are rich in dietary fiber may limit dietary choices for those with comorbid AD [45]. While increasing dietary fiber may benefit AD management, focusing solely on its intake may overshadow the importance of a diverse and balanced diet. Instead, it should be effectively integrated into a broader dietary strategy prioritizing overall nutritional adequacy and diversity. Based on our findings, encouraging individuals to adopt a diet rich in fiber alongside moderation in fat and protein intake may potentially offer a practical and effective approach to reducing the risk of AD development.

While we controlled for significant confounders such as genetic predisposition and BMI, other factors like water consumption [46] and allergen exposure [47] could influence the association between AD and dietary fiber intake. Environmental factors such as air pollution and occupational exposures may also exacerbate inflammation to worsen AD symptoms [47]. The findings should be interpreted in consideration of these potential confounding factors and future research may benefit from a more comprehensive assessment of such variables. Although there were concerns on the influence of other residual confounders like residential and stress factors on the association [48, 49], we did not include it our main analysis to prevent overfitting of model. This will obscure the true association between dietary fiber intake and AD. However, in separate analyses where we controlled for stress and residential factors, and the association remained consistent. Though non-Chinese ethnic groups (Malays and Indians) were recruited, their smaller population size limits extensive analysis in this study. Future studies could include larger samples from these populations to investigate the broader impact of dietary fiber on AD in other ethnicities. We also aim to enhance the reliability and applicability of our newly developed dietary index by replicating our findings in an independent cohort for broader dietary research, using a more detailed FFQ designed to capture various dietary information, including caloric data. This approach will allow us to contextualize our fiber index against other established metrics for chronic diseases, such as the Alternative Healthy Eating Index, the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension and Dietary Guideline Index, all of which hold significant public health relevance [50, 51].

Despite the limitations, there are several strengths of our study. We conducted sensitivity analyses to ensure the reliability and robustness of our findings. These analyses rigorously assessed the stability, in terms of direction and strength, of associations between the derived dietary index and allergic outcomes, confirming the consistency of our results. Additionally, we include a large and diverse sample size, enhancing the generalizability of our findings. The FFQ was validated for adult population [52] and the protocol has been adjusted to include dietary questions applicable to adults, with guidelines for customizing the food list to regional dietary patterns [53]. The investigator-administered FFQ allowed for detailed and accurate measurement of dietary habits related to dietary fiber intake. Our findings contribute to the growing body of evidence on the importance of dietary fiber in managing allergic conditions and offer insights for future research.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We appreciate all our participants and their family members for willingness to participate in this study.

Abbreviations

- AD

Atopic dermatitis

- AOR

Adjusted odds ratio

- BMI

Body Mass Index

- CI

Confidence intervals

- DFAI

Dietary Fiber Amount Index

- HDM

House dust mites

- ISAAC

International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood

- RCT

Randomised controlled trial

- SMCGES

Singapore/Malaysia Cross-sectional Genetics Epidemiology Study

- SPT

Skin prick test

- USDA

United States Department of Agricultural

Author contributions

F.T.C. conceived and supervised the current research study. J.J.L. contributed to the study design, data analysis, literature review, and interpretation of data. J.J.L. wrote the manuscript draft. M.H.L. provided expertise in the study methodology and critically revised the manuscript. J.J.L., K.R., Y.H.S., and M.H.L., assisted in recruiting participants and collated the data. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript for submission.

Funding

F.T.C. has received research support from the National University of Singapore, Singapore Ministry of Education Academic Research Fund, Singapore Immunology Network (SIgN), National Medical Research Council (NMRC) (Singapore), Biomedical Research Council (BMRC) (Singapore), National Research Foundation (NRF) (Singapore), Singapore Food Agency (SFA), Singapore’s Economic Development Board (EDB), and the Agency for Science Technology and Research (A*STAR) (Singapore); Grant Numbers are N-154-000-038-001, R-154-000-191-112, R-154-000-404-112, R-154-000-553-112, R-154-000-565-112, R-154-000-630-112, R-154-000-A08-592, R-154-000-A27-597, R-154-000-A91-592, R-154-000-A95-592, R-154-000-B99-114, SIgN-06-006, SIgN-08-020, NMRC/1150/2008, OFIRG20nov-0033, BMRC/01/1/21/18/077, BMRC/04/1/21/19/315, BMRC/APG2013/108, NRF-MP-2020-0004, SFS_RND_SUFP_001_04, W22W3D0006, A-8002576-00-00, H17/01/a0/008 and APG2013/108. F.T.C. has received consulting fees from Sime Darby Technology Centre, First Resources Ltd, Genting Plantation, Olam International, Musim Mas, and Syngenta Crop Protection, outside the submitted work. This research is supported by the National Research Foundation Singapore under its Open Fund-Large Collaborative Grant (MOH-001636) (A-8002641-00-00) and administered by the Singapore Ministry of Health’s National Medical Research Council. All funding agencies had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author (F.T.C.).

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The other authors declare no other competing interests.

Ethical approval and consent

This study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practices, and in compliance with local regulatory requirements. Cross-sectional studies in Singapore were conducted on the National University of Singapore (NUS) campus annually between 2005 and 2022, under the approval of the Institutional Review Board (NUS-IRB Reference Code: NUS-07-023, NUS-09-256, NUS-10-445, NUS-13-075, NUS-14-150, and NUS-18-036) and by the Helsinki declaration. Cross-sectional studies in Malaysia were held in the Universiti Tunku Abdul Rahman (UTAR), and Sunway University. Ethical approval was granted respectively from the Scientific and Ethical Review Committee (SERC) of UTAR (Ref. code: U/SERC/03/2016) and Sunway University Research Ethics Committee (Ref. code: SUREC 2019/029). Before the data collection, all participants involved signed an informed consent form.

Consent for publication

All authors have read and consented to the publication of this manuscript.

References

- 1.Drucker AM, Wang AR, Li WQ, Sevetson E, Block JK, Qureshi AA (2017) The burden of atopic dermatitis: summary of a report for the National Eczema Association. J Invest Dermatol 137(1):26–30. 10.1016/j.jid.2016.07.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Khan A, Adalsteinsson J, Whitaker-Worth DL (2022) Atopic dermatitis and nutrition. Clin Dermatol 40(2):135–144. 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2021.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lim JJ, Liu MH, Chew FT (2024) Dietary interventions in atopic dermatitis: a comprehensive scoping review and analysis. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 10.1159/000535903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Trowell H (1976) Definition of dietary fiber and hypotheses that it is a protective factor in certain diseases. Am J Clin Nutr 29(4):417–427. 10.1093/ajcn/29.4.417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Venter C, Meyer RW, Greenhawt M et al (2022) Role of dietary fiber in promoting immune health-an EAACI position paper. Allergy 77(11):3185–3198. 10.1111/all.15430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sdona E, Ekström S, Andersson N et al (2022) Dietary fibre in relation to asthma, allergic rhinitis and sensitization from childhood up to adulthood. Clin Transl Allergy. 12(8):e12188. 10.1002/clt2.12188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee H, Lee K, Son S et al (2021) Association of allergic diseases and related conditions with dietary fiber intake in Korean adults. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 18(6):2889. 10.3390/ijerph18062889 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang Z, Shi L, Pang W et al (2016) Is a high-fiber diet able to influence ovalbumin-induced allergic airway inflammation in a mouse model? Allergy Rhinol (Providence) 7(4):213–222. 10.2500/ar.2016.7.0186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Singstat (2020) Census of population 2020 statistical release. https://www.singstat.gov.sg/-/media/files/publications/cop2020/sr1/findings.pdf. Retrieved 2023 Aug 05

- 10.Asher MI, Keil U, Anderson HR et al (1995) International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC): rationale and methods. Eur Respir J 8(3):483–491. 10.1183/09031936.95.08030483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chew FT, Lim SH, Goh DY, Lee BW (1999) Sensitization to local dust-mite fauna in Singapore. Allergy 54(11):1150–1159. 10.1034/j.1398-9995.1999.00050.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Andiappan AK, Puan KJ, Lee B, Nardin A, Poidinger M, Connolly J et al (2014) Allergic airway diseases in a tropical urban environment are driven by dominant mono-specific sensitization against house dust mites. Allergy 69(4):501–509. 10.1111/all.12364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Williams HC, Burney PG, Hay RJ, Archer CB, Shipley MJ, Hunter JJ et al (1994) The U.K. working party’s diagnostic criteria for atopic dermatitis. I. Derivation of a minimum set of discriminators for atopic dermatitis. Br J Dermatol. 131(3):383–396. 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1994.tb08530.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hanifin J, Rajka G (1980) Diagnostic features of atopic eczema. Acta Derm Venereol 92:44–47 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Williams H, Robertson C, Stewart A et al (1999) Worldwide variations in the prevalence of symptoms of atopic eczema in the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood. J Allergy Clin Immunol 103(1 Pt 1):125–138. 10.1016/s0091-6749(99)70536-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Werner Y (1986) The water content of the stratum corneum in patients with atopic dermatitis. Measurement with the corneometer CM 420. Acta Derm Venereol. 66(4):281–284 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ellwood P, Asher MI, Björkstén B, Burr M, Pearce N, Robertson CF (2001) Diet and asthma, allergic rhinoconjunctivitis and atopic eczema symptom prevalence: an ecological analysis of the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) data ISAAC Phase One Study Group. Eur Respir J. 17(3):436–443. 10.1183/09031936.01.17304360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ellwood P, Asher MI, García-Marcos L, Williams H, Keil U, Robertson C et al (2013) Do fast foods cause asthma, rhinoconjunctivitis and eczema? Global findings from the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) phase three. Thorax 68(4):351–360. 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2012-202285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Manousos O, Day NE, Trichopoulos D, Gerovassilis F, Tzonou A, Polychronopoulou A (1983) Diet and colorectal cancer: a case-control study in Greece. Int J Cancer 32(1):1–5. 10.1002/ijc.2910320102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lim JJ, Lim YYE, Ng JY et al (2022) An update on the prevalence, chronicity, and severity of atopic dermatitis and the associated epidemiological risk factors in the Singapore/Malaysia Chinese young adult population: a detailed description of the Singapore/Malaysia Cross-Sectional Genetics Epidemiology Study (SMCGES) cohort. World Allergy Organ J. 15(12):100722. 10.1016/j.waojou.2022.100722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ali Z, Suppli Ulrik C, Agner T, Thomsen SF (2018) Is atopic dermatitis associated with obesity? A systematic review of observational studies. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 32(8):1246–1255. 10.1111/jdv.14879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Böhme M, Wickman M, Lennart Nordvall S, Svartengren M, Wahlgren CF (2003) Family history and risk of atopic dermatitis in children up to 4 years. Clin Exp Allergy 33(9):1226–1231. 10.1046/j.1365-2222.2003.01749.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Broberg A, Kalimo K, Lindblad B, Swanbeck G (1990) Parental education in the treatment of childhood atopic eczema. Acta Derm Venereol 70(6):495–499 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim A, Silverberg JI (2016) A systematic review of vigorous physical activity in eczema. Br J Dermatol 174(3):660–662. 10.1111/bjd.14179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cortina-Borja M, Smith AD, Combarros O, Lehmann DJ (2009) The synergy factor: a statistic to measure interactions in complex diseases. BMC Res Notes. 2:105. 10.1186/1756-0500-2-105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Spencer CN, McQuade JL, Gopalakrishnan V et al (2021) Dietary fiber and probiotics influence the gut microbiome and melanoma immunotherapy response. Science 374(6575):1632–1640. 10.1126/science.aaz7015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wastyk HC, Fragiadakis GK, Perelman D et al (2021) Gut-microbiota-targeted diets modulate human immune status. Cell 184(16):4137-4153.e14. 10.1016/j.cell.2021.06.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lim JJ, Reginald K, Say YH, Liu MH, Chew FT (2023) A Dietary pattern for high estimated total fat amount is associated with enhanced allergy sensitization and atopic diseases among Singapore/Malaysia young Chinese adults. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 10.1159/000530948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lim JJ, Reginald K, Say YH, Liu MH, Chew FT (2023) Dietary protein intake and associated risks for atopic dermatitis, intrinsic eczema, and allergic sensitization among young Chinese adults in singapore/malaysia: key findings from a cross-sectional study. JID Innov. 3(6):100224. 10.1016/j.xjidi.2023.100224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lim JJ, Lim SW, Reginald K, Say Y-H, Liu MH, Chew FT (2024) Association of frequent intake of trans fatty acids and saturated fatty acids in diets with increased susceptibility of atopic dermatitis exacerbation in young Chinese adults: a cross-sectional study in Singapore/Malaysia. Skin Health Dis. 10.1002/ski2.330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Desai MS et al (2016) A dietary fiber-deprived gut microbiota degrades the colonic mucus barrier and enhances pathogen susceptibility. Cell 167:1339-1353e1321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Parke MA, Perez-Sanchez A, Zamil DH, Katta R (2021) Diet and skin barrier the role of dietary interventions on skin barrier function. Dermatol Pract Concept 11(1):e2021132. 10.5826/dpc.1101a132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tap J, Furet JP, Bensaada M et al (2015) Gut microbiota richness promotes its stability upon increased dietary fibre intake in healthy adults. Environ Microbiol 17(12):4954–4964. 10.1111/1462-2920.13006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Swann OG, Breslin M, Kilpatrick M et al (2021) Dietary fibre intake and its association with inflammatory markers in adolescents. Br J Nutr 125(3):329–336. 10.1017/S0007114520001609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Milesi G, Rangan A, Grafenauer S (2022) Whole grain consumption and inflammatory markers: a systematic literature review of randomized control trials. Nutrients. 14(2):374. 10.3390/nu14020374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ma W, Nguyen LH, Song M et al (2021) Dietary fiber intake, the gut microbiome, and chronic systemic inflammation in a cohort of adult men. Genome Med. 13(1):102. 10.1186/s13073-021-00921-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Soh SE, Tint MT, Gluckman PD et al (2014) Cohort profile: Growing Up in Singapore Towards healthy Outcomes (GUSTO) birth cohort study. Int J Epidemiol 43(5):1401–1409. 10.1093/ije/dyt125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Loo EXL, Soh SE, Loy SL et al (2021) Cohort profile: Singapore Preconception Study of Long-Term Maternal and Child Outcomes (S-PRESTO). Eur J Epidemiol 36(1):129–142. 10.1007/s10654-020-00697-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fiocchi A, Cabana MD, Mennini M (2022) Current use of probiotics and prebiotics in allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 10(9):2219–2242. 10.1016/j.jaip.2022.06.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fiocchi A, Pawankar R, Cuello-Garcia C et al (2015) World allergy organization-McMaster University Guidelines for Allergic Disease Prevention (GLAD-P): probiotics. World Allergy Organ J. 8(1):4. 10.1186/s40413-015-0055-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chang YS, Trivedi MK, Jha A, Lin YF, Dimaano L, García-Romero MT (2016) Synbiotics for prevention and treatment of atopic dermatitis: a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. JAMA Pediatr. 170(3):236–242. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.3943 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.den Besten G, van Eunen K, Groen AK, Venema K, Reijngoud DJ, Bakker BM (2013) The role of short-chain fatty acids in the interplay between diet, gut microbiota, and host energy metabolism. J Lipid Res 54(9):2325–2340. 10.1194/jlr.R036012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rokaite R, Labanauskas L (2005) Gastrointestinal disorders in children with atopic dermatitis. Medicina (Kaunas) 41(10):837–845 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ioniță-Mîndrican CB, Ziani K, Mititelu M et al (2022) Therapeutic benefits and dietary restrictions of fiber intake: a state of the art review. Nutrients. 14(13):2641. 10.3390/nu14132641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li SK, Liu Z, Huang CK, Wu TC, Huang CF (2022) Prevalence, clinical presentation, and associated atopic diseases of pediatric fruit and vegetable allergy: a population-based study. Pediatr Neonatol 63(5):520–526. 10.1016/j.pedneo.2022.03.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chaplin MF (2003) Fibre and water binding. Proc Nutr Soc 62(1):223–227. 10.1079/pns2002203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kantor R, Silverberg JI (2017) Environmental risk factors and their role in the management of atopic dermatitis. Expert Rev Clin Immunol 13(1):15–26. 10.1080/1744666X.2016.1212660 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kage P, Simon JC, Treudler R (2020) Atopic dermatitis and psychosocial comorbidities. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges 18(2):93–102. 10.1111/ddg.14029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang J, Janson C, Malinovschi A et al (2022) Asthma, allergic rhinitis and atopic dermatitis in association with home environment—the RHINE study. Sci Total Environ 853:158609. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.158609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schwingshackl L, Bogensberger B, Hoffmann G (2018) Diet quality as assessed by the healthy eating index, alternate healthy eating index, dietary approaches to stop hypertension score, and health outcomes: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. J Acad Nutr Diet 118(1):74-100.e11. 10.1016/j.jand.2017.08.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.McNaughton SA, Ball K, Crawford D, Mishra GD (2008) An index of diet and eating patterns is a valid measure of diet quality in an Australian population. J Nutr 138(1):86–93. 10.1093/jn/138.1.86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ellwood P, Asher MI, Billo NE et al (2017) The Global Asthma Network rationale and methods for Phase I global surveillance: prevalence, severity, management and risk factors. Eur Respir J. 49(1):1601605. 10.1183/13993003.01605-2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Global Asthma Network (2016) The global asthma Network manual for global Surveillance: prevalence, severity, Management and risk factors: Global Asthma Network. [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author (F.T.C.).